1. Introduction

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) is a commonly used tool to evaluate interventions and medications in health economics, providing valuable information through health technology assessments (HTA). Gradually, researchers have discovered its potential application in diagnostic and medical tests. In recent years, CEA has been deployed in numerous HTAs for diagnosis and medical tests, including studies such as Thomas et al. [

1], Jacobsen et al. [

2], and Choi et al. [

3]. However, some studies (Fang et al. [

4], Yang et al. [

5], and Snowsill [

6]) indicate that the application of CEA to the diagnosis and testing of HTAs is becoming more popular, but various crucial factors such as optional interventions, additional information, and test accuracy have not been adequately considered.

In this context, precision medical tests have emerged as advanced diagnostic tools that use techniques such as genomic sequencing, proteomics, and biomarker analysis to accurately identify individual biological characteristics, guiding personalized treatment decisions. These tests are crucial for implementing targeted therapies, improving the accuracy of clinical decision making, and optimizing the allocation of healthcare resources. However, Ling et al. [

7] and Kasztura et al. [

8] note that, considering the high cost and uncertainty, only a fraction of these new technologies are likely to be cost-effective and adopted by healthcare systems, raising concerns about the efficient use of research funding and healthcare resources.

Designs for CEA analysis of diagnosis and testing require specific considerations given their distinct characteristics. Mushlin et al. [

9] emphasizes the importance of focusing on factors such as the clinical pathway, the baseline probability of disease, and intermediate outcome measures. Koffijberg et al. [

10] further points out that when evaluating the cost-effectiveness of new diagnostic test technologies, it is also necessary to consider the characteristics, costs, and effects of the latest diagnostic tests. In addition to the above, Smith et al. [

11] emphasizes the importance of incorporating valuable new evidence and iterating the analysis methodology in the cost-effectiveness analysis process of diagnostic tests.

In precision medical tests, patient identification and targeted interventions are key, which requires careful consideration of the accuracy of the diagnostic tests used for patient classification (Gavan et al. [

12], Mattos-Arruda and Siravegna [

13], Chen et al. [

14]). This underscores the importance of the accuracy of the test in CEA, a consensus that has existed for a long time in the academic community. More than two decades ago, Hernandez [

15] emphasized the importance of test accuracy in CEA. Subsequent systematic reviews by Van den Bruel et al. [

16] further demonstrated the need to analyze test and diagnostic accuracy when reporting CEA results. Seo and Strong [

17] presents a practical model guide for CEA of diagnostic and testing techniques, emphasizing the importance of accuracy in the analysis process. Similarly, Snowsill [

6] emphasizes the need to fully consider the impact of test accuracy on results during model construction. The sensitivity of the results to the accuracy parameters is also reflected in some disease-specific CEA studies, including Novielli et al. [

18], Novielli et al. [

19], Garg et al. [

20], Biltaji et al. [

21], and other studies. However, most existing research focuses on specific applications or qualitative discussions, lacking a quantitative framework to systematically analyze the relationship between test accuracy and cost-effectiveness under general assumptions.

To bridge this gap, our study establishes a generalized model to quantify the accuracy requirements of precision medical tests to achieve cost-effectiveness.

Fundamentally, we derive a theoretical lower bound that combined by two bounds that the accuracy of precision medical tests must exceed: 1) Lower Bound for Matching Intervention, which is the minimum accuracy required to ensure that appropriate treatment matching is provided to each patient category based on the test results; 2) Lower Bound for Overall Effectiveness, which is the minimum accuracy required to make the test cost-effective for the entire patient population. The derivation of these two lower bounds offers theoretical guidance for developing, pricing, and procuring diagnostic tests. In addition, we develop the special case of sensitivity and specificity, that is, the case in which only binary test results are considered. This situation is common in clinical practice, such as genetic screening and the testing of infectious diseases. By analyzing this particular case, we obtain more specific accuracy thresholds, which are significant for evaluating the cost-effectiveness of standard medical screening tests.

Our results not only reveal unfair medical decision making that can be caused by insufficient test accuracy, but also provide a new economic perspective to explain the underdiagnosis of rare diseases and the challenges of implementing precision medicine in small groups of patients. Through numerical simulations, we further verify the theoretical results and explore the impact of test accuracy on expected net monetary benefits and the proportion of patients receiving appropriate interventions. In summary, our finding helps to provide a theoretical criteria tool for determining if a precision medical test is cost effective.

2. Model Settings

To illustrate the relationship between test accuracy and CEA results, we utilize a simplified model. We assume that patients can be divided into finite classes, each of which is suited to a particular medical intervention, and there are only two possible health outcomes: receiving the appropriate intervention or not. Furthermore, this paper uses net monetary benefit (NMB) as a measure to assess which health intervention is more cost-effective, from the point of view of classical CEA.

2.1. General Settings

Consider a patient population in which each patient has unique intrinsic and unobservable characteristics that can be categorized into

N classes. Each class of patients has a unique medical intervention that is the most appropriate. It is assumed that the most suitable medical intervention can lead to the gain of

quality adjusted life years (QALY) for a patient belonging to the respective class, while an unsuitable one can only allow the acquisition of

QALY. Specifically, the QALY returns obtained from intervention

j for patients in class

i,

, can be expressed as

That is, patients belonging to the class i gain QALY when they undergo their designated intervention i, while the use of interventions not designed for their class can only result in QALY, with . To clarify, in clinical practice, and could be positive or negative, according to the outcome of different interventions.

The cost of an intervention is denoted as

, where

j refers to the intervention. The NMB approach combines the QALY and the cost of an intervention with a monetary constant

. That is, the NMB of using intervention

j for patients in class

i,

, can be expressed as

The distribution structure of the intrinsic characteristics of patients in the entire population can be observed through retrospective statistics over time. Let be a discrete distribution that represents the probability of patients being assigned to a specific class i, where i is one of the classes. The primary objective of medical intervention decisions is to maximize the expected NMB of patients for the entire population.

2.2. The Medical Test and the Accuracy

Suppose a medical test is available to identify intrinsic characteristics of patients that incur a cost of

, as previously mentioned. However, the medical test is not always accurate, with a level of accuracy denoted as

. In other words, the probability that the medical test correctly identifies the patients in class

i is

. For simplicity, we assume that errors are equally likely to be assigned to each of the other classes. Denote the random outcome of the medical test as

. Then, there exists

In particular, a patient’s own intrinsic type i cannot be directly observed. The only observable result is the patient’s medical test, which produces a result of . Following the test, any intervention decision can only be made based on the outcome . However, the result is a random variable. This is the primary factor that contributes to the effect of medical test accuracy on the evaluation results of CEA.

Let be an intervention strategy based on the medical test, where denotes the intervention assigned to patients with a test result of i. To be clear, we notice that is actually a mapping rule, mapping the patient category i to intervention . It is important to note that the class of patients with a test result of i may not necessarily correspond to patients of intrinsic type i. If the test is performed and the intervention strategy is chosen, the expected NMB per unit for all patients is indicated as . If no medical test is performed, a unique intervention will be assigned to all patients. The expected NMB per unit, in this case, is denoted as .

2.3. Expected NMB with the Medical Test

This subsection focuses on the expressions of

and

. Based on the definition, one can easily show that the expected NMB per unit,

, could be expressed as

where

denotes the conditional expectation with respect to class

i. Although complex, we can decompose the expression using

in Lamma 1.

Lamma 1.

has a decomposition with the result of , which is

where is part of NMB that the class of patients with result contributes and could be expressed as

Proof. potL1Proof of Lamma 1

Initially, we can reform the expression for

by implementing the total probability formula, subsequently sorted according to the result of

. This approach enables us to derive:

where

Next, if

,

and else if

,

Lamma 1 presents the result that a patient’s expected NMB when using the medical test, depending on the decision strategy

. On contrary, in cases where the test is not used, we can express

as

In this instance, refers to the set of unique strategies where for all i.

3. Decision Making

In an economic perspective, medical decision makers must select the most cost-effective intervention from available treatments, regardless of whether or not medical tests are present. Hence, analyzing the system’s output level under the most cost-effective intervention for each situation is crucial before comparing changes in systematic output with and without medical testing. To align with the classical CEA decision framework, we utilize maximizing the expected NMB as the selection criterion in each case and investigate the most suitable intervention decisions.

3.1. Decision Making without the Test

When medical testing is absent, medical decision makers cannot differentiate between various types of patients. Although in clinical practice, patients still could receive various treatments because of availability, coverage of insurance, or clinician’s preference, but these situations are independent of the category of patients. This means that the various treatments could be regarded as random as refers to the category, which could be proved to be not more cost effective than the unique intervention strategy in expectation. This means that it is reasonable to assume that the physician must select a single intervention as the most cost-effective option for all patients. Thus, comparing the expected NMB results of the

N interventions for the entire population would suffice to determine the best intervention alternative in this case. Without considering patient characteristics to dictate treatment decisions, the optimal strategy is the specific intervention that offers the highest expected NMB for the general patient population among the

N options. The expression for this strategy is:

The forthcoming Theorem 1 presents the most cost-effective intervention selection for the situation without medical testing.

Theorem 1.

Without a medical test, the optimal intervention should be chosen as

Proof. potT1Proof of Theorem 1

Mark

, then

where

is free from

and the proof is done.

From Theorem 1, two simple corollaries can be deduced. First, when interventions have the same costs, the optimal strategy is the one suitable for the largest number of patients, that is, the intervention with the highest proportion of suitable patients. Moreover and the second, if we assume that the proportions of patient types are uniform, the most cost-effective intervention is the least expensive. Both align with traditional CEA decision making progress and are consistent with economic intuition.

With the analysis above, the expected optimal NMB in the absence of medical testing could be measured as

which serves as the decision benchmark to determine whether to use a medical test. This means that for a medical test to be cost-effective, the NMB of the entire population of patients must exceed this benchmark.

3.2. Decision Making with the Test

The necessary conditions of a precision medical test to be cost-effective contains two major parts. The first is to make sure that it could ensure that each category of patient gets its most suitable treatment. This leads to the "Lower Bound for Matching Intervention". The second is to make sure that given the first condition, the incremental cost and incremental outcome are more cost-effective referring to the situation of no medical test. This leads to the "Lower Bound for Overall Effectiveness". In this subsection, we will provide the expressions of these two lower bounds.

The Lower Bound for Matching Intervention aims to maintain local optimum standards. The core of this standard is to provide fair, consistent, and optimal treatment opportunities for all patients based on the results of precision medical tests. For example, if treatment j is determined as the most effective for patients in class i, then it is ethically necessary for all patients classified as i by the test to receive treatment j, even if some may actually belong to other categories due to errors in the test. It should be noted that if the accuracy of the test is too low, it can lead to decision-makers making unethical decisions. For example, when accuracy is low, the patient group detected as a category i could be mainly composed of patients other than the category i. This may lead to the selection of another treatment for this group being more economically cost-effective, but this is in contract with the test’s orientation.

The Lower Bound for Overall Effectiveness reflects the overall economic standard. It requires that the expected net monetary benefit (NMB) of adopting precision medical tests must exceed the NMB when no test is performed. The latter assumes that the most cost-effective unique treatment plan is adopted for the entire untested patient population. This ensures that the introduction of medical testing brings overall economic value to the healthcare system. –

We first discuss the "Lower Bound for Matching Intervention" in the following paragraphs.

We refer to assigning patients to respective interventions based on test results as the "Matching Interventions Strategy", denoted . In this scenario, , that is, . The following Theorem 2 provides the minimum accuracy level required for the "Matching Interventions Strategy" to be the most cost-effective subject to some regular conditions.

Theorem 2.

(Lower Bound for Matching Intervention). Under the condition that

for the "Matching Interventions Strategy", , to be the most efficient strategy, the accuracy for the precision medical test should satisfy

where .

Proof. potT2Proof of Theorem 2

Clearly, the necessary condition for the "Matching Interventions Strategy",

, to be the most efficient strategy is

which means that for the observation class

i, intervention

i is more efficiency than any other intervention

. Moreover, there is

So under the regular condition, we have

So

is equivalent to

and for all

i to hold this, we have

According to Theorem 2, achieving the target of maximizing expected NMB would require exceeding the minimum level of accuracy while assigning the theoretically optimal interventions to every observation category of patients. That is, only enough accurate testing can ensure cost-effective intervention decisions based on test results. In particular, the regularity conditions in Theorem 2 entail that ideal interventions cannot be too costly for patient subclasses with a relatively high proportion.

To enhance comprehension, we provide an illustration of Theorem 2 under equivalent probabilities, outlined in the subsequent Corollary 1.

Corollary 1.

(Lower Bound for Matching Intervention (Equally distributed)) If , the lower bound in Theorem 2 equals

where and .

Proof. potC1Proof of Corollary 1

Substitute the designated probabilities into Theorem 2.

Corollary 1 shows that for intervention decisions based on test results to be the most cost-effective under equal probabilities, the accuracy of the test must exceed the accuracy of random selection by a specific level. This specific level is determined by the ICER switching from the least expensive to the most expensive for patients suitable for the most expensive intervention. However, considering , if the most expensive intervention is too costly, choosing that intervention would still not be cost-effective, even if the test is perfectly accurate.

Finally, once the lower bound is satisfied, we can calculate the expected NMB for the case that faces this lower bound with the medical test.

4. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis For The Medical Test

Based on the theorems above, we have derived the optimal expected NMB with and without medical testing. Based on this, we can analyze the cost effectiveness of precision medical testing by comparing the difference in the expected optimal NMB in the two situations. Theorem 3 below gives the necessary and sufficient conditions for a medical test to be cost-effective.

Theorem 3.

(Lower Bound for Overall Effectiveness) The sufficient and necessary condition for the test, , to be cost-effective, that is, is

where is the optimal intervention without the test, see Theorem 1, and is the expectation operator under the probability measure , a measure induces by α, where

Proof. potT3Proof of Theorem 3

First, we show that

is a probability measure. As

, we have

and

, so

. Moreover, there is

So that

is a probability measure. And with Equation (

16) and Equation (

25), we could get

then the proof is complete.

Theorem 3 provides the conditions necessary and sufficient for a medical test to be cost-effective in the form of a lower bound requirement for accuracy, . This means that the optimal expected NMB with testing will exceed that without testing if and only if the medical test’s accuracy meets the criteria stated in Theorem 3.

In Theorem 3, the lower bound is in the form of two components: one is in the form of an "ICER", and the other is the proportion of patients suitable to

. It is very important to show that Theorem 3 keeps the form of ICER with some induced probability measure. For the expression

the numerator can be regarded as the incremental cost using suitable treatment than global optimal treatment, and the denominator is the incremental outcome measured by QALY, adjusted by

. This means that the lower bound in Theorem 3 is a standardized ICER with some modification. Moreover, no matter if there is a medical test, there must always be some patients using their suitable treatment, which forms the second term in the lower bound in Theorem 3.

Let us further investigate the probability measure induced by . It can be seen that when , , and when , . This measure is a weighted average between and the uniform distribution . Furthermore, from a practical point of view, represents the probability that a patient will receive a test result of i in the entire population, under the accuracy of the medical test, . represents the expected cost of the intervention if all patients receive the corresponding intervention based on the test results.

According to Theorem 3, we show that the Lower Bound for Overall Effectiveness will increase as the cost increases. In other words, the accuracy must be higher for a more expensive test to meet cost-effectiveness. However, if most patients could receive an intervention that is sufficiently inexpensive and highly appropriate without a medical test (that is, is large and is small), then the required lower bound may exceed 1, which means that there is no cost-effective test. This explains why rare diseases often lack adequate diagnosis and targeted treatments.

Theorem 3 provides precise guidelines for medical testing to meet cost-effectiveness. This means that if and only if the accuracy of the medical test meets the criteria stated in Theorem 3, the expected NMB with the test will exceed the case without the test. This provides essential guidance for medical decision makers in selecting and purchasing testing technologies.

5. The Case Of Sensitivity And Specificity

In this section, we discuss the special case that is more common in general medical test studies. In this case, the class number is set to , which means that only two kinds of patient are in the target population: one is called the "True Positive" class, marked as , and the other is called the "True Negative", marked as . This is the simplest case in clinical decision making, which often occurs when deciding whether a patient has a specific disease or is at high risk.

We consider a medical test with just two types of results: one gives a positive result, called the "

Reported Positive (j=1)" and the other gives a negative result, called the "

Reported Negative (j=0)". In this case, the accuracy

is measured by two variables, one is named sensitivity,

, which is defined as

The other is named as specificity,

, which is defined as

It is very clear that sensitivity is the proportion of true positive tests out of all patients with a condition, and specificity is the percentage of true negatives out of all subjects who do not have a disease or condition. An accuracy medical test requires both the sensitivity and specificity to be high, which is often conflicted. We do not focus on this conflict but just analyses this case as a special case for our theorems above. For this proposal, we simply consider the case that

to meet the setting of our model above.

Moreover, we assume that the treatment for class 1, the true positive class, is conditionally cost-effective, which means that

This assumption means that this treatment is cost-effective for patients, otherwise the treatment is too expensive even we can build a medical test with , which need not to be discussed.

The following corollary gives the lower bound for matching interventions for the case .

Corollary 2.

The lower bound for matching interventions for the case is

Proof. potC2Proof of Corollary 2

First, we verify that the condition in Theorem 2 is satisfied for the case

. This is to verify that

This is clear because and .

Second, from Theorem 2, we can show that the lower bound for matching interventions could be expressed as

Corollary 2 gives the lower bound that ensures that the true positive class should receive treatment and the true negative ones should not receive treatment. It is more clear if we assume

, then Corollary 2 becomes

a special case for Corollary 1. This means that the accuracy of the medical test should be higher than the randomly guessed one,

, by a level more than

. This level is higher if the treatment is more expensive, which means that

is larger. This gives the conclusion that an expensive treatment needs a more accurate medical test.

For the test to be cost-effective, we have the following corollary from Theorem 3.

Corollary 3.

The lower bound for the test to be cost effective for the case is

where

Proof. potC3Proof of Corollary 3

We use Theorem 3 to complete this proof. First, we use Theorem 1 to determine

. With some calculation, one can show that

Then, if

, based on Theorem 3, we have

As we have

, this is equal to

Similarly, if

, based on Theorem 3, we have

As we have

, this is equal to

and the proof is finished.

The corollary 3 gives the benchmark that accuracy must be met in two conditions: one is

, which is cost-effective to give treatment to all patients if there is no medical test. In this situation, the test should be accurate enough to ensure that the outcome will be more effective than the case where everyone takes the treatment. This benchmark is

The other condition is that

, which is cost-effective to NOT give all patients the treatment if there is no medical test. The benchmark, in turn, is

Combined with Corollary 2 and Corollary 3, we can obtain the general lower bound of the accuracy of precision medical tests when , as is shown in Theorem 4.

Theorem 4.

The lower bound of the accuracy of medical test to be both cost-effectiveness and intervention matching when is given as

Proof. potT4Proof of Theorem 4

Using the conditions in Corollary 3 to discriminate the expression in Corollary 2, the proof can be shown.

Theorem 4 shows that the overall lower bound is determined by three components, and , where represents the percentage of patients in the population in the real world, represents the "unitized price" of the treatment and represents for the relative price of the medical test. Theorem 4 means that one can solve the minimum accuracy of the test given the three components or pricing the test given , , and under the rule of cost-effectiveness. It is clear that the larger , the more expensive the test is and the more difficult it is to be cost-effective. But for and , it is hard to directly tell the relationship between the two components with the bound. We therefore provide the following schematic.

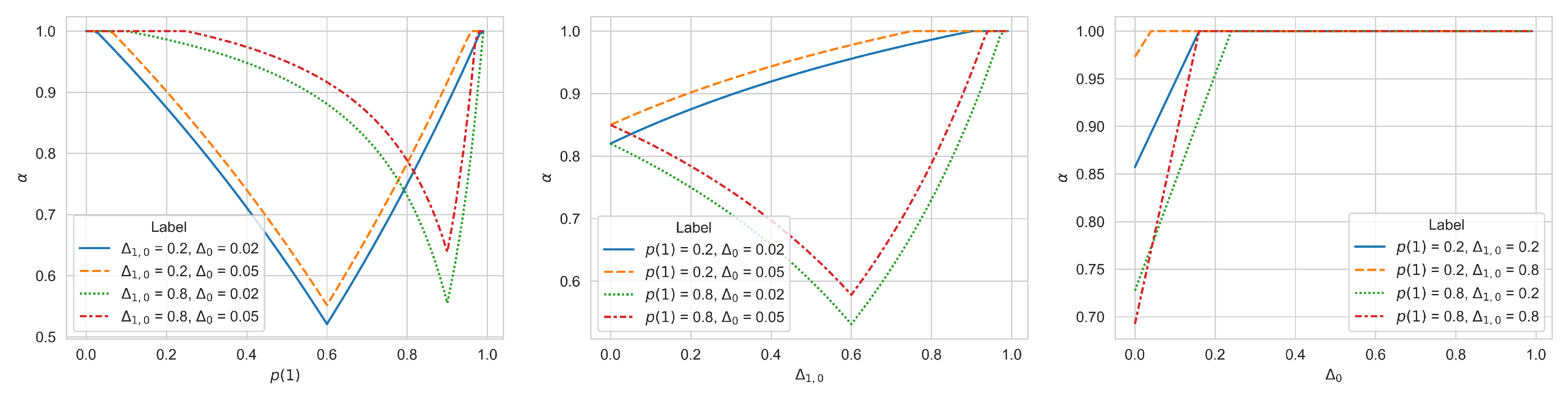

Figure 1 provides the schematic showing the relationship between the overall lower bound with

and

. In

Figure 1, the first panel shows the relationship between the overall lower bound with

, the second panel shows it with

, and the third shows it with

. In each panel, the horizontal axis represents the component and the vertical axis represents the lower bound, and the other components are controlled, shown in the legends.

From

Figure 1 we can find the following:

-

The influence of the percentage of patients in the population():

The influence of on the lower bound shows an obvious V-shaped curve. When approaches 0 or 1, the lower bound increases significantly, indicating that detection is difficult. Cost-effectiveness. This can be understood by comparing it with the "no detection" situation: when is close to 0, the simple "no treatment" strategy can achieve better results; when is close to 1, the "treat all" strategy can achieve better results. This also reminds us that the value of testing lies in its ability to significantly change medical decisions, and it should be considered together with the corresponding cost of treatment. This finding has important implications for testing strategies in different disease areas: For rare diseases, multiple factors may need to be considered to consider the value of testing; for common diseases, the cost-effectiveness of a universal prevention strategy versus targeted testing may need to be weighed. In addition, this relationship also explains why the development of diagnostic technologies for certain rare diseases is challenging: not only because the market is small, but also because the test itself is difficult to be cost effective at low .

-

The impact of the relative price of the treatment():

When is small, the lower bound is positively correlated with . This is because, in low prevalence settings, expensive treatments must be used more cautiously to avoid wasting resources on many healthy people who do not need treatment. As the cost of treatment increases, medical testing requires greater precision to identify patients who truly need treatment accurately. However, when is large, within certain intervals, expensive treatments require a lower detection accuracy. The following mechanism can explain this seemingly contradictory phenomenon: a) In the case of high , if there is no detection, the optimal decision is to treat everyone universally. b) As the cost of treatment increases, the greater the cost savings through testing to distinguish the few negative cases to avoid unnecessary treatment. c) Therefore, in cases where is not high enough but treatment costs are high, even a test that is not very accurate may be cost-effective because it can help reduce some unnecessary expensive treatments. This complex relationship reveals an essential trade-off in medical decision-making. In the context of high treatment costs and high morbidity, a less precise test that roughly distinguishes patients may be better than no test or a costly test with high accuracy. Testing is more cost-effective. However, it should be noted that when continues to increase beyond a certain threshold, the lower bound will rise again. This is because the incorrect use of extremely expensive treatments is too costly, requiring greater detection accuracy.

-

The impact of the relative price of the medical test ():

When is below a specific critical value, the lower bound increases as increases; however, once exceeds a specific critical value, the lower bound suddenly jumps to greater than 1, which means that no matter how the detection accuracy is improved, cost-effectiveness cannot be achieved. This threshold effect reveals a crucial economic reality: there is an upper limit on the cost of testing, beyond which testing becomes economically unfeasible. It is worth noting that this threshold is not fixed but will be affected by other factors, such as disease prevalence and treatment costs.

6. A Numerical Simulation Example

In this section, we employ numerical simulation to illustrate and confirm the previously mentioned findings. Concretely, we define a set of patient groups with corresponding medical interventions, assign costs and QALY outcomes, and calculate the expected NMBs for both scenarios - with and without the medical test - as previously mentioned. This enables us to derive a precise correlation between the accuracy of a medical test and its CEA outcomes. Furthermore, we shall validate and explain the Theorem 2 introduced in this paper and substantiate it by analyzing the percentage of patients receiving the most suitable treatment within each class.

To balance the variety of patient classes alongside comprehensible simulation results, we assume that patients can be classified into six innate classes,

, and each class relates to a distinct and most suitable medical intervention. Each patient with the most suitable intervention achieves a QALY output of

and

for the rest. Furthermore, we assume a monetization constant of

. Finally, we present

Table 1 to demonstrate the composition of the patients in the classes and the respective cost level of the most fitting intervention for each class.

During the simulation, we initially analyzed the correlation between precise medical testing and its cost effectiveness. Specifically, we examine various and calculate the expected NMB, at the optimal level corresponding to different in each and compare it with the expected NMB without medical tests, . This enables us to conclude whether the testing is cost-effective.

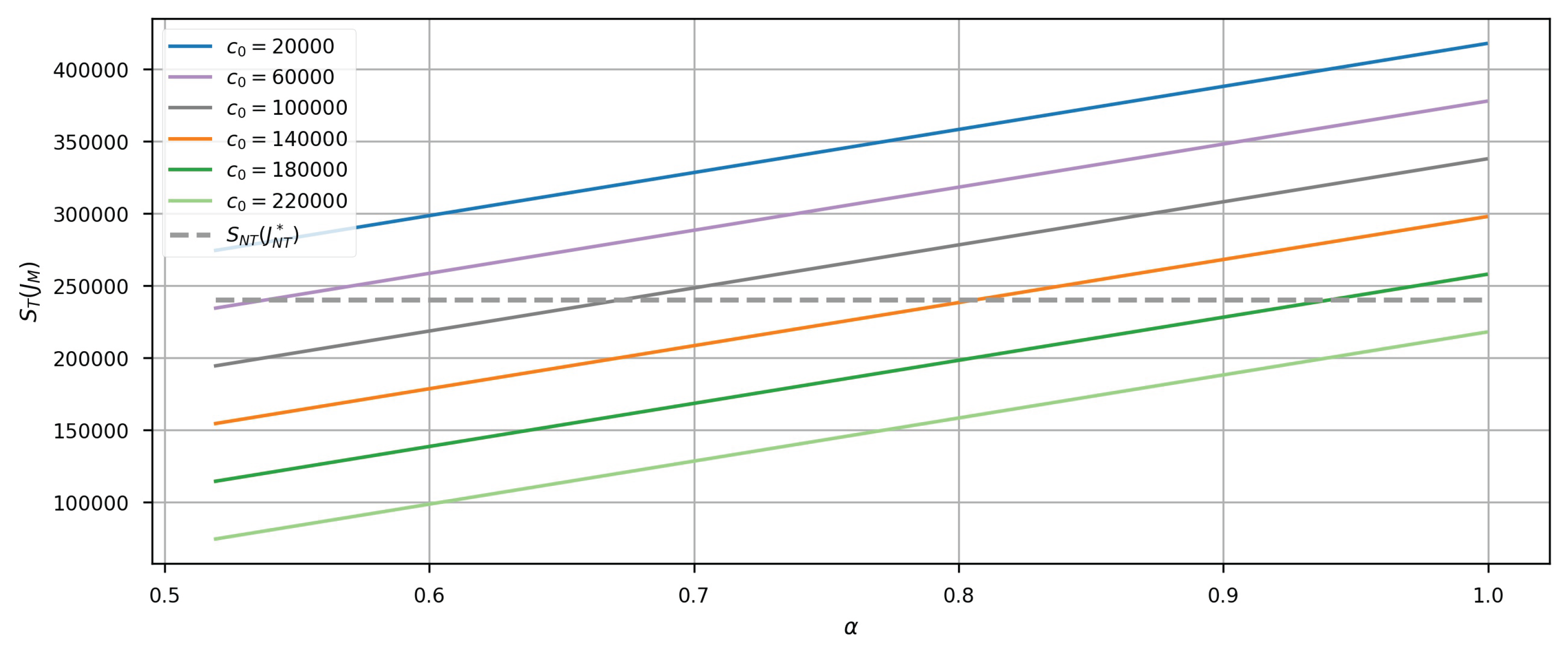

Figure 2 illustrates the results of this calculation. The graph shows that the expected NMB obtained from the use of precision medical tests increases linearly with the accuracy of the test. This indicates that a more accurate medical test yields a better overall result. In addition, the intersection of the curve and the dashed line determines the minimum accuracy level at which the test cost is efficient. As

increases, so does the position of the intersection, which means that a more expensive test requires greater accuracy to meet cost-effectiveness.

Figure 2 features two critical cases significant in practice. Firstly, for the curve of

, the medical test does not meet the cost effectiveness regardless of how accurate it is. This implies an upper limit on the pricing of precision medical tests to meet the cost-effectiveness of the patient population. Any test priced above this limit would probably not be accepted, regardless of its accuracy. Therefore, this can serve as a futuristic pricing reference for companies developing differential diagnostic tests for specific diseases. Secondly, for the curve of

, the test is always cost-effective as long as the Lower Bound of Matching Interventions is met. Thus, when the test is priced sufficiently low, its cost-effectiveness can be evaluated simply by determining whether Theorem 2 is satisfied. This serves as a reference for the purchase of health insurance.

We verify Theorem 2 in the second simulation phase. We calculate the expected NMB output, , for each feasible intervention decision (totaling ) at specific levels. Afterwards, we compare the maximum result with the expected NMB output of the matched intervention decision, , to determine the level at which the matched intervention decision satisfies the optimal requirement. Meanwhile, we determine the percentage of patients who receive the most appropriate medical intervention in each class under the strategy () corresponding to the highest expected NMB result. This shows the significant loss of welfare for some groups of patients when the lower bound in Theorem 2 is not met.

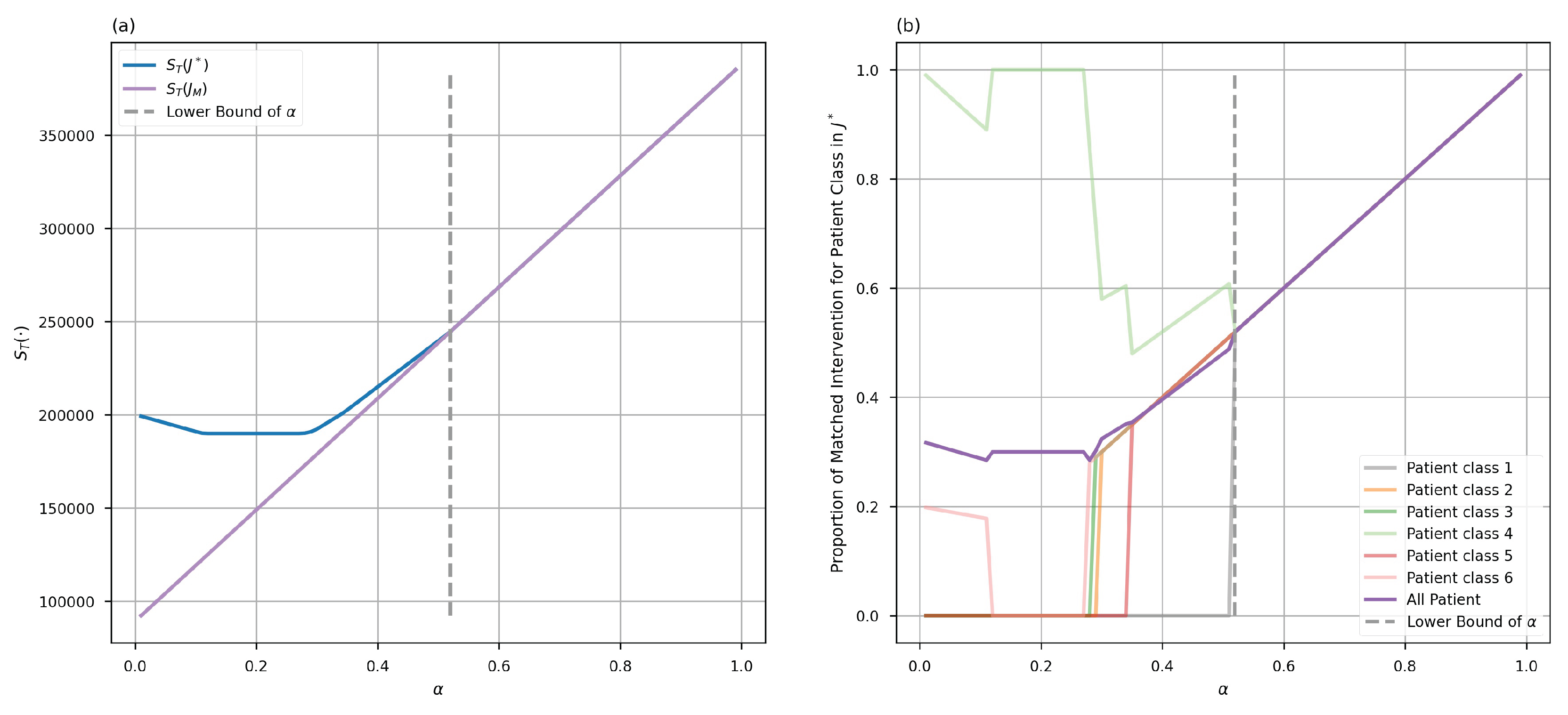

The results of the calculation are presented in

Figure 3.

Figure 3 (a) indicates that the use of the matched intervention decision

may not correspond to the decision with the expected maximum NMB when the accuracy falls below the lower bound, but it remains optimal among all intervention decisions when the accuracy goes beyond the lower bound. This finding confirms Theorem 2. Furthermore,

Figure 3 (b) shows that, for the left side of the dashed line, where the accuracy is below the lower bound, the proportion of patients in different classes receiving the corresponding interventions fluctuates drastically and is significantly lower on average than the level observed on the right side of the dashed line. On the right side of the dashed line, the intervention proportion for each class remains consistent and steadily increases as the accuracy increases, eventually reaching 1.

The results of numerical simulations show that when the accuracy of precision medical tests falls below the lower limit, many patients may receive interventions that do not match their actual medical needs. As a result, the overall proportion of patients who eventually received the appropriate interventions decreased significantly. At the same time, there are significant differences in the proportion of appropriate interventions among different groups of patients, resulting in further inequity.

It is important to note that in cases of extremely low accuracy, the optimal expected NMB may decrease as accuracy increases. This is caused by the case of inverse forecast, which means using an ’always wrong’ predictor to get the right prediction. In simple terms, one can use an "always wrong" prediction to make an "always right" one. For example, only two types of patients are involved. In that case, if the detection accuracy is 0, the detection results are opposite to the actual situation, and decisions that are opposite to the medical test results can be made. Therefore, when the accuracy increases slightly from 0, NMB may first decrease and then increase after the accuracy further improves.

In general, this numerical example provides empirical evidence of the importance of lower accuracy bounds and their impact on the assessment of the accuracy of precision medical tests. For the given problem, the accuracy of medical testing must satisfy the matching lower bound in Theorem 2 and the overall lower bound of cost-effectiveness in Theorem 3. In addition, the results reveal a common correlation between the accuracy of medical testing and the acceptable price range within a specified interval, which helps to price or purchase medical testing services. It also reveals that accuracy can make the overall medical system less cost effective and exacerbate health inequalities among different groups of patients.

7. Conclusions and Discussion

This study establishes a quantitative model to elucidate the relationship between the accuracy of precision medical tests and the results of the cost-effectiveness analysis. Specifically, our key findings indicate that, for a medical test to be deemed cost effective, its precision must exceed two critical lower bounds.

First, as formulated in Theorem 2, the test accuracy must exceed a lower bound threshold to ensure that patients receive the optimal matching interventions corresponding to their test results individually. This theorem quantitatively expresses the lower bound based on probabilities of class of patients, intervention costs, and QALY differentials. Breaching this bound can lead to substantial mismatches between patients and interventions, compromising treatment effectiveness and fairness between different patient subgroups. Second, as derived from Theorem 3, the test must surpass an overall lower accuracy bound to achieve cost effectiveness for the entire patient population. This bound relies on factors such as the cost of the optimal intervention without testing, the expected cost under test-based interventions, and the QALY differential.

The model and simulations presented here provide an economic perspective on the challenges of applying new medical testing technologies, the underdiagnosis of rare diseases, and the difficulties of implementing precision medicine in small patient populations. First, our analysis suggests that when a considerably large proportion of patients can be treated sufficiently well with inexpensive interventions, the intervention cost for a new test can become stringent, which hinders the adoption of some new medical testing technology. Second, in this paper’s context, the patient population with rare diseases is classified under the "low probability, high complexity" class. Corollary 1 suggests that under these circumstances, regardless of the accuracy or price of the test, applying the test to patients with rare diseases is not cost-effective. This insight explains the lack of market incentive to create differential diagnostic tests for rare diseases. Third, the study offers information on the mismatching of interventions that arise due to insufficient testing accuracy. Theorem 2 provides a novel perspective that explains the factors that prevent some observation classes from receiving interventions that match their respective test results when the accuracy of the test falls below the lower bound.

In general, the research results of this paper provide a unified explanatory framework for many practical problems, that is, multiple factors such as the precision of medical tests, the structure of the patient group, the intervention cost, and the value of the health utility of the disease jointly determine the optimal allocation of the corresponding medical resources. By quantifying the accuracy thresholds necessary for clinical and economic viability, this study provides theoretical guidance to healthcare system stakeholders, helping precision medical test developers assess pricing, healthcare payers and providers assess cost-effectiveness, and policymakers optimize resource allocation and promote equitable access to diagnostic services.

Several limitations remain to be addressed through future research. To better understand these associations, this paper excludes heterogeneity in QALY outcomes and medical costs within classes and does not explore complex stochastic CEA results such as the cost-effective analysis curve (CEAC). Further studies will investigate the impact of including randomness in CEA evaluations on the conclusions presented in this paper. Although this article mainly discusses the need for precision medical tests to reach a specific lower limit of accuracy to be cost-effective, it is worth noting that even if the test results are not entirely accurate, they may still provide valuable partial information rather than completely useless. In other words, precise partial test results may not directly lead to the optimal treatment plan. However, they can at least guide some suboptimal but still meaningful treatment suggestions rather than ultimately leading to meaningless decisions. Therefore, in future research, an in-depth analysis of the accuracy of nonbinary tests and its corresponding related mechanisms will help to more fully understand the impact of test accuracy on medical decision making, thus having significant research value.

8. Declarations

Funding - No funding has been received for the conduct of this study.

Conflicts of Interest - Authors Xinyue Zeng, Ermo Chen, and Huajie Jin declare that he has no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and material - Not applicable.

Ethics approval - Not applicable.

Consent to participate - Not applicable.

Consent for publication - Not applicable.

Code availability - The code in this study is available on request from the corresponding author.

Author contributions - Not applicable.

References

- R. Thomas, W. J. M. Probert, R. Sauter, L. Mwenge, S. Singh, S. Kanema, N. Vanqa, A. Harper, R. Burger, A. Cori, M. Pickles, N. Bell-Mandla, B. Yang, J. Bwalya, M. Phiri, K. Shanaube, S. Floyd, D. Donnell, P. Bock, H. Ayles, S. Fidler, R. J. Hayes, C. Fraser, K. Hauck. Cost and cost-effectiveness of a universal hiv testing and treatment intervention in zambia and south africa: evidence and projections from the hptn 071 (popart) trial. The Lancet Global Health 2021, 9, e668–e680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E. Jacobsen, S. Sawhney, M. Brazzelli, L. Aucott, G. Scotland, M. Aceves-Martins, C. Robertson, M. Imamura, A. Poobalan, P. Manson, C. Kaye, D. Boyers. Cost-effectiveness and value of information analysis of nephrocheck and ngal tests compared to standard care for the diagnosis of acute kidney injury. BMC nephrology 2021, 22, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N. Choi, S. Jang, K. H. Yoo, C. K. Rhee, Y. Kim. The effectiveness and harms of screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Korean medical science 2022, 37, e117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Fang, H. J. Otero, D. Greenberg, P. J. Neumann. Cost-utility analyses of diagnostic laboratory tests: A systematic review, Value in health. Value Health 2011, 14, 1010–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, L. Abel, J. Buchanan, T. Fanshawe, B. Shinkin. Shinkins, Use of decision modelling in economic evaluations of diagnostic tests: An appraisal and review of health technology assessments in the uk. PharmacoEconomics 2019, 3, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. Snowsill. Modelling the cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests. PharmacoEconomics 2023, 41, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. I. Ling, L. D. Lynd, M. Harrison, A. H. Anis, N. Bansback. Early cost–effectiveness modeling for better decisions in public research investment of personalized medicine technologies. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research 2019, 8, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Kasztura, A. Richard, N.-E. Bempong, D. Loncar, A. Flahault. Cost-effectiveness of precision medicine: a scoping review. International journal of public health 2019, 64, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. I. Mushlin, H. S. Ruchlin, M. A. Callahan. Costeffectiveness of diagnostic tests. The Lancet 2001, 358, 1353–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Koffijberg, B. van Zaane, K. G. Moons. From accuracy to patient outcome and cost-effectiveness evaluations of diagnostic tests and biomarkers: an exemplary modelling study. BMC medical research methodology 2013, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. F. Smith, A. Sutton, B. Shinkins. Early cost-effectiveness analysis of new medical tests: Response. International journal of technology assessment in health care 2016, 32, 324–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. P. Gavan, A. J. Thompson, K. Payne. The economic case for precision medicine. Expert review of precision medicine and drug development 2018, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. D. Mattos-Arruda, G. Siravegna. How to use liquid biopsies to treat patients with cancer. ESMO Open 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Chen, T. Anothaisintawee, D. Butani, Y. Wang, Y. Zemlyanska, C. Boon, N. Wong, S. Virabhak, M. A. Hrishikesh, Y. Teerawattananon. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of precision medicine: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. S. Hernandez. Cost-effectiveness of laboratory testing. Archives of pathology and laboratory medicine 2003, 127, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Van den Bruel, I. Cleemput, B. Aertgeerts, D. Ramaekers, F. Buntinx. The evaluation of diagnostic tests: evidence on technical and diagnostic accuracy, impact on patient outcome and cost-effectiveness is needed. Journal of clinical epidemiology 2007, 60, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. K. Seo, M. Strong. A practical guide to modeling and conducting a cost-effectiveness analysis of companion biomarker tests for targeted therapies using r: Tutorial paper. PharmacoEconomics 2021, 39, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Novielli, N. J. Cooper, K. R. Abrams, A. J. Sutton. How is evidence on test performance synthesized for economic decision models of diagnostic tests? a systematic appraisal of health technology assessments in the uk since 1997. Value in Health 2010, 13, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Novielli, N. J. Cooper, A. J. Sutton. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests in combination: Is it important to allow for performance dependency? Value in health 2013, 16, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Garg, N. Y. Gu, M. E. Borrego, D. W. Raisch. A literature review of cost-effectiveness analyses of prostate-specific antigen test in prostate cancer screening. Expert review of pharmacoeconomics and outcomes research 2013, 13, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Biltaji, B. Bellows, D. Stenehjem, D. Brixner. Validation of a cost-effectiveness model comparing accuracy of genetic tests for brca mutations. Value in health 2016, 19, A79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).