Submitted:

03 May 2023

Posted:

05 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Principles of pH-Responsive Drug Delivery

2.1. Design of Drug Carriers for pH-Responsive Delivery

2.2. Intratumoral Delivery Strategy

2.3. Intracellular Delivery Strategy

2.4. Peculiarities of DDS Administration

2.5. Outlook

3. Analysis of Drug Carriers’ Features

3.1. 1 Drug Loading Efficiency of Different pH-Responsive DDSs

Doxorubicin Loading Efficiency

| Active substance | DDS type | DDS configuration |

Surface area (m^2/g) | Pore volume (cm^3/g) | Pore size (nm) | DDS’s ζ potential (mV) | DLC (%) | DEE (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Doxorubicin (DOX) |

MOF (ZIF-8) |

HMS@ZIF | 788 | 0.65 | - | - | - | - |

[174] |

| DOX/HMS | 483 | 0.42 | - | - | 34 | - | |||

| DOX/HMS@ZIF | 1152 | - | +31.2 | 28 | - | ||||

| DOX/HMS@ZIF-50 | 120 | - | - | +30.1 | 44 | - | |||

| BSA/DOX@ZIF | - | - | - | +26.7 | 10 | - | [152] | ||

| DOX@ZIF-8 | - | - | - | +27 | 10 | - |

[133] |

||

| DOX@ZIF-8@AS1411 | - | - | - | −8 | - | - | [133] | ||

| ZIF-8 | 1465.9 | - | 0.6 | +28.9 | - | - |

[166] |

||

| ZIF-8@DOX | - | - | - | −33.7 | 43.3 | - | |||

| ZIF-8@DOX@Silica | - | - | - | −32.6 | 42.7 | - | |||

| ZIF-8@DOX@Organosilica | - | - | - | −34.3 | 41.2 | - | |||

| ZIF-8 | 1244 | - | 1.8 | - | - | - |

[162] |

||

| DOX@ZIF-8/Dex | 1078 | - | 1.8 | - | 63 | - | |||

| H-ZIF-8/PDA-CD JNPs | - | - | - | −19.5 | - | - |

[175] |

||

| HCPT@DOX@H-ZIF-8/PDA-CD JNPs | - | - | - | - | 42 | - | |||

|

MOF (ZIF-90) |

UC@mSiO2-RB@ZIF | 556.2 | 0.68 | - | - | - | - |

[142] |

|

| UC@mSiO2-RB@ZIFO2-DOX-PEGFA | - | - | - | - | 6 | - | |||

|

MOF |

UCMOFs | - | - | - | +19.1 | - | - |

[143] |

|

| UCMOFs@Dox@5-Fu | - | - | - | +16.3 | 16.4 | - | |||

|

MOF (UIO-66) |

UIO-66-NH2 | 569.595 | - | - | - | - | - | [163] | |

| UIO-66-NH2/PB/DOX | - | - | - | - | 67.4 | - | |||

| Fe3O4@UIO-66-NH2/Graphdiyne | - | - | - | −23.2 | - | - |

[159] |

||

| Fe3O4@UIO-66-NH2/Graphdiyne/DOX | - | +5.07 | 43.8 | - | |||||

|

MOF (Cu (II)-porphyrin) |

Cu(II)-porphyrin/Graphene oxide | 352 | 0.32 | 4.9 | −19.8 | - | - |

[176] |

|

| Cu(II)-porphyrin/Graphene oxide-DOX | - | - | - | −2.15 | 45.7 | - | |||

|

γ-cyclodextrin-based MOF (CD-MOF) |

DOX/γ-CD-MOF | - | - | - | - | - | 45 |

[177] |

|

| DOX/GQDs@γ-CD-MOF | - | - | - | - | - | 51.6 | |||

| DOX /AS1411@PEGMA@GQDs@ γ-CD-MOF | - | - | - | - | - | 89.1 | |||

|

MOF (NH2-MIL-88B) |

NH2-MIL-88B | - | - | - | +57 | - | - |

[178] |

|

| DOX@NH2-MIL-88B | - | - | - | - | 7.4 | - | |||

| DOX@NH2-MIL-88B-On-NH2-MIL-88B | - | - | - | +86 | 14.4 | - | |||

|

MOF (NH2-MIL-88B (Fe)) |

Fe-MOF | 592.2 | - | 5.4 | +26.9 | - | - |

[164] |

|

| DOX@FeMOF@PSS@MV-PAH@PSS | - | - | - | −13.5 | 88.4 | - | |||

|

MOF (MIL-101) |

MIL-101 | 4500 | - | 2.9 - 3.4 | - | - | - |

[137] |

|

| MIL-101@DOX | - | - | - | - | 36.2 ± 1.4 | - | |||

|

MOF (Prussian blue) |

NiCo-PBA@DOX | - | - | - | - | - | 19.6 |

[134] |

|

| NiCo-NiCo-PBA@Tb3+@ DOX | - | - | - | - | - | 16.9 | |||

| NiCo-NiCo-PBA@Tb3+@PEGMA@DOX | - | - | - | - | - | 72.2 | |||

| NiCo-PBA@Tb3+@PEGMA@AS1411@DOX | - | - | - | - | - | 60.3 | |||

|

MOF |

Bio-MOFs | 935 | 0.37 | 3.47 | - | - | - |

[148] |

|

| DOX /Bio-MOFs | - | - | - | - | 39 | 76 | |||

| CS/BioMOF | 438 | 0.25 | 3.12 | +2.4 | - | - | |||

| DOX / CS/BioMOF | - | - | - | - | 48.1 | 92.5 | |||

| MeO NPs | MnO2NPs@Keratin@DOX | - | - | - | - | 8.7 | - | [179] | |

|

Fluorouracil (5-Fu) |

MOF |

CS/Zn-MOF@GO | 2.22 | 0.51 | 35.17 | - | - | - |

[154] |

| 5-Fu@CS/Zn-MOF@GO | - | - | - | - | 45 | - | |||

|

MOF |

UCMOFs | - | - | - | +19.1 | - | - |

[143] |

|

| UCMOFs@Dox@5-Fu | - | - | - | +16.3 | 24.7 | - | |||

|

MOF (UIO-66) |

UiO-67-CDC | 818.3 | 0.91 | - | +0.229 | - | - |

[180] |

|

| 5-Fu@UiO-67-CDC | - | - | - | - | 22.5 | - | |||

| UiO-67-CDC-(CH3)2 | 354.3 | 0.73 | - | +22.017 | - | ||||

| 5-Fu@UiO-67-CDC-(CH3)2 | - | - | - | −0.106 | 56.5 | - | |||

|

MOF |

[Zn3(BTC)2(Me)(H2O)2](MeOH)13 | 1426 | - | 0.59 | - | - | - |

[181] |

|

| 5-Fu/[Zn3(BTC)2(Me)(H2O)2](MeOH)13 | - | - | - | - | 34.32 | - | |||

|

Curcumin (CUR) |

MOF (ZIF-L) |

ZIF-L | - | - | - | +3.8 | - | - |

[182] |

| CUR@ZIF-L | - | - | - | +4.1 | - | 98.21 | |||

|

MeO NPs |

N-succinyl-CS-ZnO | - | - | - | −26.1 ± 1.35 | - | - |

[144] |

|

| CUR-CS-ZnO | - | - | - | −16 ± 1.1 | 13 | 69.6 | |||

| ZnO-PBA | - | - | - | −4.7 ± 0.31 | - | - |

[149] |

||

| ZnO-PBA@CUR | - | - | - | −16.4 ± 0.30 | 35 | 27 | |||

| Fe3O4@Au-GSH | - | - | - | −5 | - | - |

[183] |

||

| Fe3O4@Au-LA-CUR/GSH* | - | - | - | −16 | - | 70 | |||

|

Camptothecin (CPT) |

MOF (MIL) |

MIL-101(Fe)-Suc-CPT | 1254 | 0.16 | 3.6 | +6.4 | 17.6 | - |

[184] |

| MIL-101(Fe)-Click-CPT | 143 | 0.03 | 3.4 | +3.4 | 18 | - | |||

| MIL-100(Fe)-Suc-CPT | 71 | 0.07 | 3.5 | –27 | 1.3 | - | |||

| MIL-100(Fe)-Click-CPT | 70 | 0.09 | 3.6 | –45.8 | 9.2 | - | |||

| MOF | HCPT@DOX@H-ZIF-8/PDA-CD JNPs ** | - | - | - | - | 9.8 | - | [175] | |

|

Dihydroartemisinin (DHA) |

MOF (ZIF-8) |

ZIF-8 | - | - | - | +14.9 | - | - |

[168] |

| DHA@ZIF-8 | - | - | - | +15.3 | 14.9 | 77.2 | |||

| Fe/ZIF-8/DHA | - | - | - | – 7.4 | 42.2 ± 3.3 | 96.2 ± 3.6 | [121] | ||

|

Quercetin (Q) |

MeO NPs |

PBA-ZnO | - | - | - | −1.8 ± 0.12 | - | - |

[38] |

| PBA-ZnO-Q | - | - | - | −10.2 ± 0.36 | 29.83 | 46.69 | |||

| ZnO-Q | - | - | - | - | 17.4 | - | [185] | ||

|

Sonosensitizers Chlorin e6 (Ce6) |

MOF | Cu-MOF/Ce6 | - | - | - | - | 8.7 | - | [186] |

|

MOF (ZIF-8) |

ZIF-8 | - | - | - | +17 | - | - |

[170] |

|

| Ce6-DNAzyme@ZIF-8 | - | - | - | –22 | 10 | - | |||

| Alpha tocopheryl succinate (α-TOS) |

MOF (ZIF-8) |

ZIF-8 | 1485 | 0.88 | - | +22.1 | - | - |

[132] ] |

| α-TOS@ZIF-8 | 703 | 0.25 | - | +20.2 | 43.03 | - | |||

|

As(III)-drugs |

MOF |

Zn-MOF-74 | 1187 | - | - | - | - | - |

[187] |

| As2O3@Zn-MOF-74 | 452 | - | - | - | 11.6 | - | |||

| Chloroquine diphosphate (CQ) |

MOF (ZIF-8) |

ZIF-8 | +12.1 | - | - |

[169] |

|||

| CQ@ZIF-8 | 756 | - | - | +9.5 | 18 | - | |||

|

Rose Bengal (RB) |

MOF (ZIF-90) |

UC@mSiO2-RB@ZIF | 556.2 | 0.68 | - | - | - | - |

[142] |

| UC@mSiO2-RB@ZIFO2-DOX-PEGFA | - | - | - | - | 5.6 | - | |||

|

Piperlongumine (PL) |

MOF |

Fe-TPA | - | - | - | +45 ± 2.8 | - | - |

[188] |

| Tf-Lipo-Fe-TPA@PL | - | - | - | −10.2 ± 0.6 | 12.3 ± 4.33 | 78.7 ± 2.98 | |||

| Methyl gallate (MG) | MOF (ZIF-L) | MG@ZIF-L | - | - | - | –21 | 18.05 | 90.26 | [189] |

| Imatinib | MeO NPs | Fe3O4@CS/Imatinib | - | - | - | - | 52 | 61 | [147] |

Fluorouracil Loading Efficiency

Curcumin Loading Efficiency

3.2. pH-Responsive Release of the Active Substance from DDSs

3.2.1. Acidic pH-Triggered Drug Release

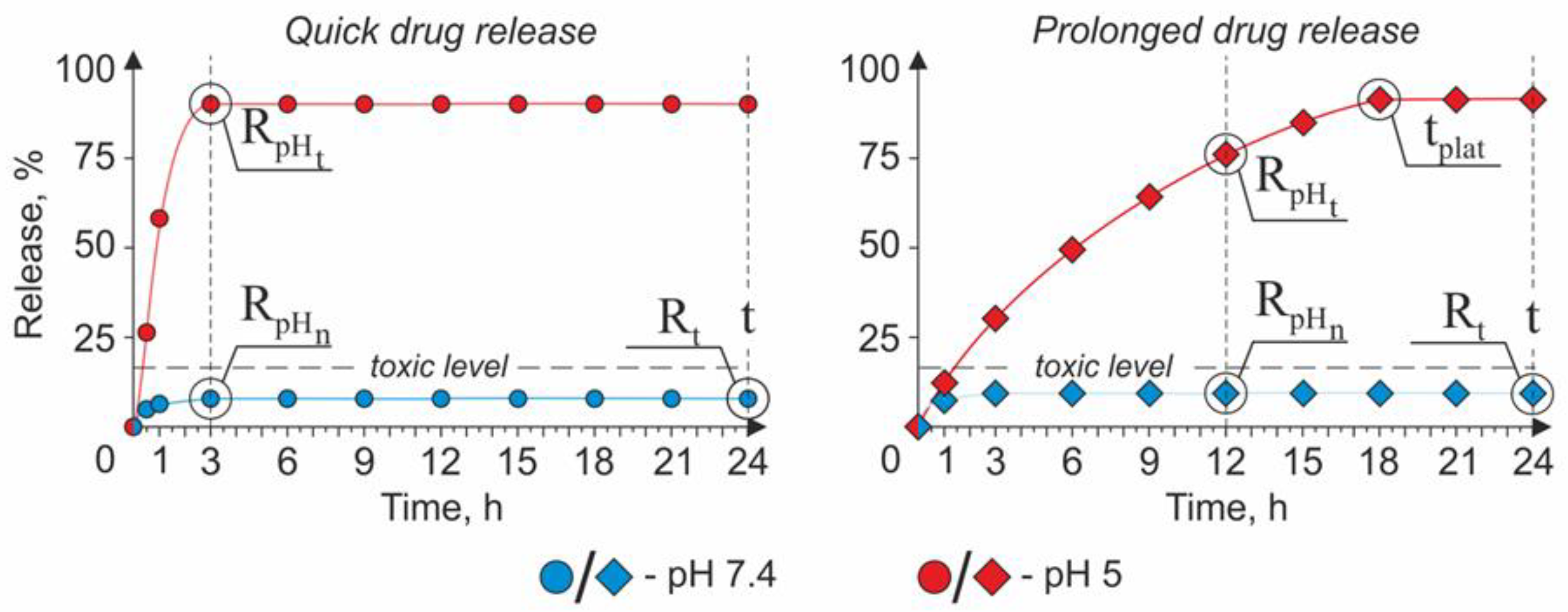

The Strategy of a Quick Drug Release

| Active substance |

DDS type |

DDS configuration |

|

(a.u.) |

DLC (%) |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Doxorubicin (DOX) |

MOF (MIL) | DOX@ NH2-MIL-88B | 2 | - | 7.4 | [178] |

| MOF (ZIF-90) | UC@mSiO2-RB@ZIF-O2-DOX-PEGFA | 14.6* | - | 6 | [142]] | |

| MOF (ZIF-8) | DOX@ZIF-8 | 6.2 | 0.58 | 43.3 | [166] | |

| MOF (ZIF) | UCMOFs@D@5 | 9 | 2.4 | 16.4 | [143] | |

| Fluorouracil (5-Fu) | MOF (ZIF) | UCMOFs@D@5 | 12 | 4 | 24.7 | [143] |

| Curcumin (CUR) | MeO NPs | CUR-CS-ZnO | 2.4** | - | 13 | [144] |

The Strategy of a Prolonged Drug Release

Doxorubicin Loaded DDSs

| Active substance | DDS type | DDS configuration | (a.u.) | (h) |

(a.u.) |

DLC (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Doxorubicin (DOX) |

MOFs (ZIF-8) |

DOX/HMS@ZIF | 52.6 | 10 | - | 28 | [174] |

| BSA/DOX@ZIF | 6.7 | 11 | - | 10 | [152] | ||

| DOX@ZIF-8@AS1411 | 34.2 | 20 | 12 | - | [133] | ||

| AuNCs@MOF-DOX | 2.8 | 20 | 1 | - | [208] | ||

| ZIF-8@DOX@Organosilica | 2.3 | 24 | 0.9 | 41.2 | [166] | ||

| ZIF-8@DOX | 3.6 | ∼72 | 1.3 | - | [209] | ||

| DOX@ZIF-8 | 3.3 | 50 | 1.3 | - | [162] | ||

| DOX@ZIF-8/Dex | 2.8 | 68 | 1.7 | 63 | |||

| H-ZIF-8/PDA-CD JNPs | 3.2 | 30 | 1.1 | - |

[175] |

||

| H-ZIF-8/PDA-CD JNPs + laser (808 nm, 1 W cm−2, 5 min) | 2.7 | - | - | - | |||

| MOFs (Cu-TCPP MOF) | Cu-TCPP-DOX | 1.57 | >60 | 0.75 | - |

[176] |

|

| MOFs (graphene oxide/Cu (II)-porphyrin) | CuG1-DOX | 2.8 | 60 | 1 | 45.7 | ||

| MOFs (Fe-MOF) | DOX@FeMOF@PSS@MV-PAH@PSS | 36.5 | ∼24 | 12 | 88.4 | [164] | |

|

MOFs (γ-cyclodextrin-based MOF) |

DOX/γ-CD-MOF | 2.1 | 1 | 2.4 | - |

[177] |

|

| DOX/GQDs@γ-CD-MOF | 9.5 | 72 | 8 | - | |||

| DOX/AS1411@PEGMA@GQDs@ γ-CD-MOF | 4.8 | 96 | 2.4 | - | |||

|

MOFs (UIO-66) |

UIO-66-NH2/PB/DOX | 15.6 | 36 | 6 | 67.4 | [163] | |

| Fe3O4@UIO-66-NH2/Graphdiyne/DOX | 1.3 | 24 | 0.7 | 43.8 | [159][ | ||

| MOFs (MIL-88B) | DOX@ NH2-MIL-88B-On-NH2-MIL-88B | 1.8 | 10 | - | 14.4 |

[178] |

|

| MeO NPs | MnO2 NPs@Keratin@DOX | 1.4 | 24 | 0.7 | 8.7 | [179] | |

|

Fluorouracil (5-Fu) |

MOF | 5-Fu@ [Zn3(BTC)2(Me)(H2O)2](MeOH)13 | 2.8 | ∼48 | 1.3 | 34.32 | [181] |

| MOF | 5-Fu@CS/Zn-MOF@GO | 1.8 | 24 | 1.2 | 45 | [154] | |

| MOF (ZIF-8) | 5-FU@ZIF-8@Lf-TC | 3.15 | 24 | 0.9 | 24.9 ± 1.4 | [146] | |

|

Curcumin (CUR) |

MeO NPs |

CUR-CS-ZnO | 2.25 | 10 | - | 13 | [144] |

| ZnO-PBA@CUR | 31 | 36 | 4.8 | 35 | [149] | ||

| Fe3O4@Au- LA-CUR | 4.6* | 6 | 1.3 | - | [183] |

Fluorouracil Loaded DDSs

Curcumin Loaded DDSs

3.2.2. Normal pH-Triggered Drug Release

4. In vitro Studies of pH-Responsive DDSs

4.1. Cytotoxicity of DDSs

DOX-MTT-MCF-7

DOX-MTT-HeLa

DOX-MTT-4T1

4.2. Internalization of pH-Responsive DDSs

5. In vivo Studies of pH-Responsive DDSs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gadducci, A.; Cosio, S. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer: Review of the Literature and Perspectives of Clinical Research. Anticancer Research 2020, 40, 4819–4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernousfaderani, E.K.; Akhtari, N.; Rezaei, S.; Rezaee, Y.; Shiranirad, S.; Mashhadi, M.; Hashemi, A.; Khankandi, H.P.; Behzad, S. Resveratrol and Colorectal Cancer: A Molecular Approach to Clinical Researches. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 21, 2634–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogl, U.M.; Beer, T.M.; Davis, I.D.; Shore, N.D.; Sweeney, C.J.; Ost, P.; Attard, G.; Bossi, A.; de Bono, J.; Drake, C.G.; et al. Lack of consensus identifies important areas for future clinical research: Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference (APCCC) 2019 findings. European Journal of Cancer 2022, 160, 24–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wan, C.; Dai, X.; Wu, S.; Lo, P.-C.; Huang, J.; Lovell, J.F.; Jin, H.; Yang, K. Microparticles: biogenesis, characteristics and intervention therapy for cancers in preclinical and clinical research. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmento-Ribeiro, A.B.; Scorilas, A.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Efferth, T.; Trougakos, I.P. The emergence of drug resistance to targeted cancer therapies: Clinical evidence. Drug Resistance Updates 2019, 47, 100646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.C.; Bansal, K.K.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, D.; Deep, A. Thiazole-containing compounds as therapeutic targets for cancer therapy. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 188, 112016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Xie, N.; Nice, E.C.; Zhang, T.; Cui, Y.; Huang, C. Overcoming cancer therapeutic bottleneck by drug repurposing. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2020, 5, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinwand, J.; Miller, G. Regulation and modulation of antitumor immunity in pancreatic cancer. Nature Immunology 2020, 21, 1152–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno Ayala, M.A.; Li, Z.; DuPage, M. Treg programming and therapeutic reprogramming in cancer. Immunology 2019, 157, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvandi, N.; Rajabnejad, M.; Taghvaei, Z.; Esfandiari, N. New generation of viral nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery in cancer therapy. Journal of Drug Targeting 2022, 30, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.; Biswas, S. Polymeric micelles in cancer therapy: State of the art. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 332, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wilson, R.; Hui, Y.; Yu, L.; Wibowo, D.; Zhang, C.; Whittaker, A.K.; Middelberg, A.P.J.; et al. Bioinspired Core–Shell Nanoparticles for Hydrophobic Drug Delivery. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2019, 58, 14357–14364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skotland, T.; Iversen, T.G.; Llorente, A.; Sandvig, K. Biodistribution, pharmacokinetics and excretion studies of intravenously injected nanoparticles and extracellular vesicles: Possibilities and challenges. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2022, 186, 114326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindeeva, O.A.; Verkhovskii, R.A.; Abdurashitov, A.S.; Voronin, D. V; Gusliakova, O.I.; Kozlova, A.A.; Mayorova, O.A.; Ermakov, A. V; Lengert, E. V; Navolokin, N.A.; et al. Effect of Systemic Polyelectrolyte Microcapsule Administration on the Blood Flow Dynamics of Vital Organs. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fam, S.Y.; Chee, C.F.; Yong, C.Y.; Ho, K.L.; Mariatulqabtiah, A.R.; Tan, W.S. Stealth Coating of Nanoparticles in Drug-Delivery Systems. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkhovskii, R.; Ermakov, A.; Sindeeva, O.; Prikhozhdenko, E.; Kozlova, A.; Grishin, O.; Makarkin, M.; Gorin, D.; Bratashov, D. Effect of Size on Magnetic Polyelectrolyte Microcapsules Behavior: Biodistribution, Circulation Time, Interactions with Blood Cells and Immune System. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

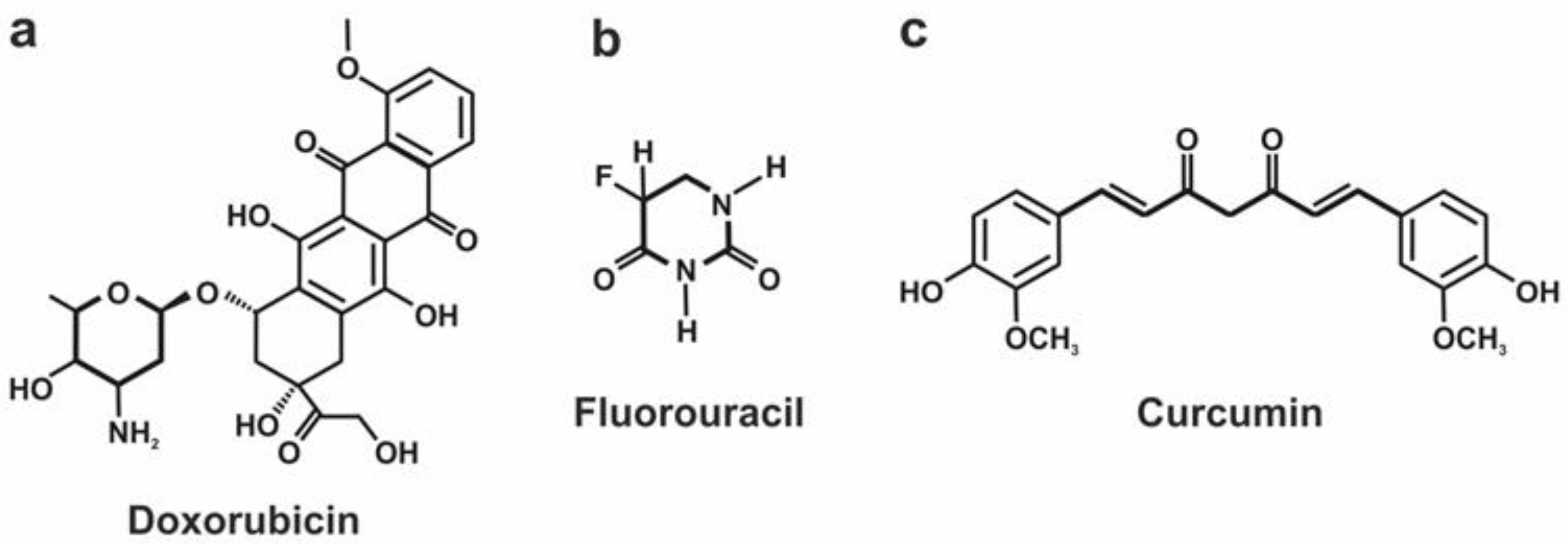

- D’Angelo, N.A.; Noronha, M.A.; Kurnik, I.S.; Câmara, M.C.C.; Vieira, J.M.; Abrunhosa, L.; Martins, J.T.; Alves, T.F.R.; Tundisi, L.L.; Ataide, J.A.; et al. Curcumin encapsulation in nanostructures for cancer therapy: A 10-year overview. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2021, 604, 120534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Lazcano, A.A.; Hassan, D.; Pourmadadi, M.; Shamsabadipour, A.; Behzadmehr, R.; Rahdar, A.; Medina, D.I.; Díez-Pascual, A.M. 5-Fluorouracil nano-delivery systems as a cutting-edge for cancer therapy. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2023, 246, 114995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Abuwatfa, W.H.; Awad, N.S.; Sabouni, R.; Husseini, G.A. Encapsulation, Release, and Cytotoxicity of Doxorubicin Loaded in Liposomes, Micelles, and Metal-Organic Frameworks: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghassemi, S.; Dadashzadeh, A.; Azevedo, R.B.; Feron, O.; Amorim, C.A. Photodynamic cancer therapy using liposomes as an advanced vesicular photosensitizer delivery system. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 339, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakov, A. V.; Verkhovskii, R.A.; Babushkina, I. V.; Trushina, D.B.; Inozemtseva, O.A.; Lukyanets, E.A.; Ulyanov, V.J.; Gorin, D.A.; Belyakov, S.; Antipina, M.N. In Vitro Bioeffects of Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Microcapsules Post-Loaded with Water-Soluble Cationic Photosensitizer. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Qin, Y.; Lee, J.; Liao, H.; Wang, N.; Davis, T.P.; Qiao, R.; Ling, D. Stimuli-responsive nano-assemblies for remotely controlled drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2020, 322, 566–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Yang, W.-W.; Xu, D.-G. Stimuli-responsive nanoscale drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. Journal of Drug Targeting 2019, 27, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, F.; Roca-Melendres, M.M.; Durán-Lara, E.F.; Rafael, D.; Schwartz, S. Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels for Cancer Treatment: The Role of pH, Light, Ionic Strength and Magnetic Field. Cancers 2021, 13, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.N.; Ermakov, A. V.; Saunders, T.; Giddens, H.; Gould, D.; Sukhorukov, G.; Hao, Y. Electrical Characterization of Micron-Sized Chambers Used as a Depot for Drug Delivery. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 18162–18169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Maeda, H.; Fang, J. Factors affecting the dynamics and heterogeneity of the EPR effect: pathophysiological and pathoanatomic features, drug formulations and physicochemical factors. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery 2022, 19, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Park, C.; Yi, G.; Lee, D.; Koo, H. Active Targeting Strategies Using Biological Ligands for Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Systems. Cancers 2019, 11, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Guan, J.; Qian, J.; Zhan, C. Peptide ligand-mediated targeted drug delivery of nanomedicines. Biomaterials Science 2019, 7, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Q.; Deng, Y.; Chen, X.; Ji, J. Rational Design of Cancer Nanomedicine for Simultaneous Stealth Surface and Enhanced Cellular Uptake. ACS Nano 2019, acsnano.8b07746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-L.; Chen, D.; Shang, P.; Yin, D.-C. A review of magnet systems for targeted drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2019, 302, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhovskii, R.; Ermakov, A.; Grishin, O.; Makarkin, M.A.; Kozhevnikov, I.; Makhortov, M.; Kozlova, A.; Salem, S.; Tuchin, V.; Bratashov, D. The Influence of Magnetic Composite Capsule Structure and Size on Their Trapping Efficiency in the Flow. Molecules 2022, 27, 6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoor, A.A.; Lindner, L.H.; Landon, C.D.; Park, J.-Y.; Simnick, A.J.; Dreher, M.R.; Das, S.; Hanna, G.; Park, W.; Chilkoti, A.; et al. Overcoming Limitations in Nanoparticle Drug Delivery: Triggered, Intravascular Release to Improve Drug Penetration into Tumors. Cancer Research 2012, 72, 5566–5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racca, L.; Cauda, V. Remotely Activated Nanoparticles for Anticancer Therapy. Nano-Micro Letters 2021, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirvakili, S.M.; Langer, R. Wireless on-demand drug delivery. Nature Electronics 2021, 4, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, K.; Hornowski, T.; Antal, I.; Timko, M.; Józefczak, A. Magneto-ultrasonic heating with nanoparticles. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2019, 474, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelmi, A.; Schutt, C.E. Stimuli-Responsive Biomaterials: Scaffolds for Stem Cell Control. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2021, 10, 2001125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Zhao, W.; Yu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhao, C. Recent Development of pH-Responsive Polymers for Cancer Nanomedicine. Molecules 2018, 24, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhukhan, P.; Kundu, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Ghosh, N.; Manna, P.; Das, J.; Sil, P.C. Targeted delivery of quercetin via pH-responsive zinc oxide nanoparticles for breast cancer therapy. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2019, 100, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

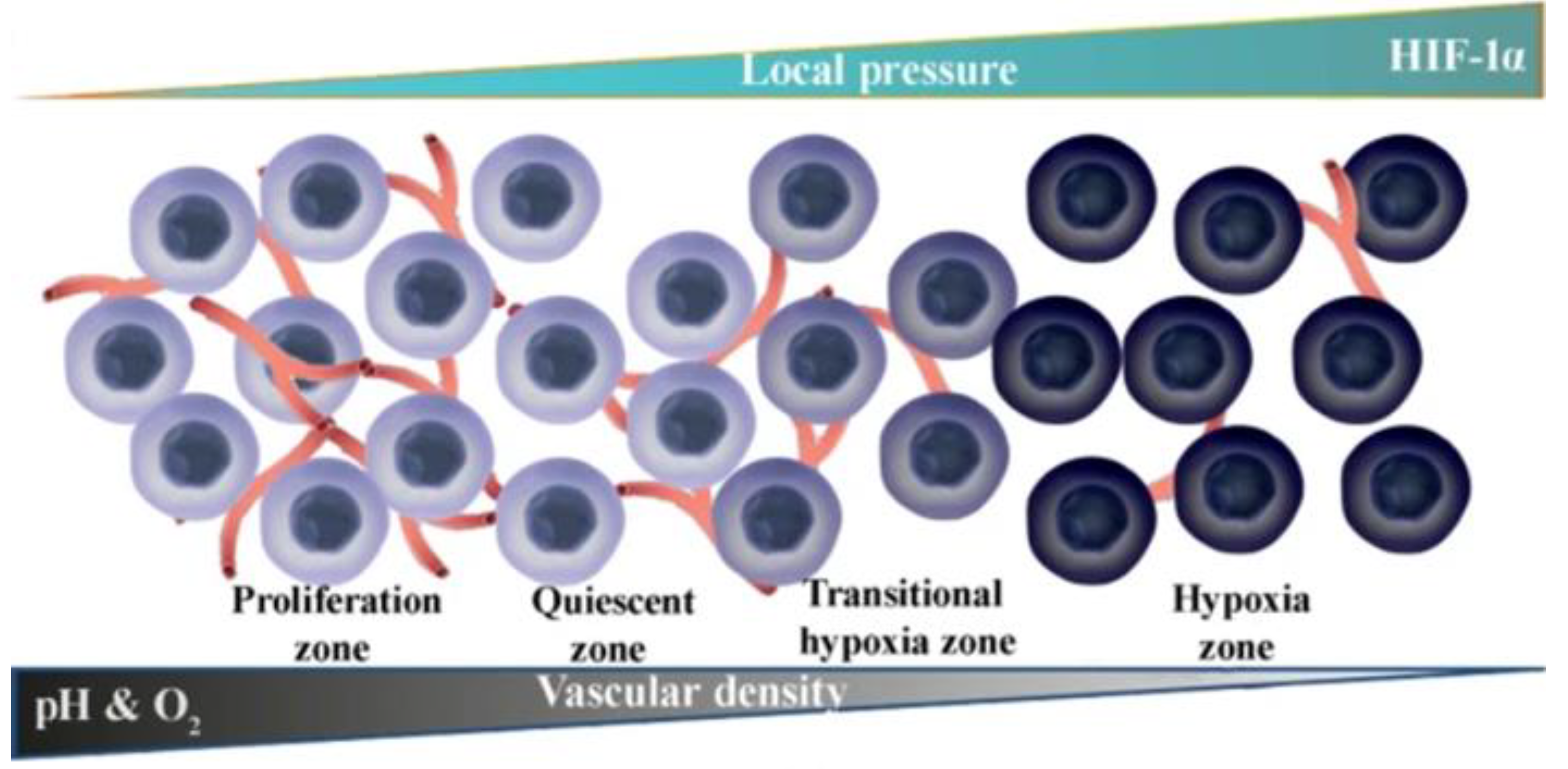

- Liberti, M. V.; Locasale, J.W. The Warburg Effect: How Does it Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2016, 41, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, S.; Zhang, F.; Yu, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, G.; Liu, X. pH-Sensitive Biomaterials for Drug Delivery. Molecules 2020, 25, 5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSawaftah, N.M.; Awad, N.S.; Pitt, W.G.; Husseini, G.A. pH-Responsive Nanocarriers in Cancer Therapy. Polymers 2022, 14, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamala, M.; Wilson, W.R.; Yang, M.; Palmer, B.D.; Wu, Z. Mechanisms and biomaterials in pH-responsive tumour targeted drug delivery: A review. Biomaterials 2016, 85, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.-J.; Chen, F. pH-Responsive Drug-Delivery Systems. Chemistry - An Asian Journal 2015, 10, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Y.; Gong, L.; Peng, T.; Yao, J.; Lin, Z. Advances in pH-responsive drug delivery systems. OpenNano 2021, 5, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, J.; Wu, J. pH-Sensitive nanogels for drug delivery in cancer therapy. Biomaterials Science 2021, 9, 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhelm, S.; Tavares, A.J.; Dai, Q.; Ohta, S.; Audet, J.; Dvorak, H.F.; Chan, W.C.W. Analysis of nanoparticle delivery to tumours. Nature Reviews Materials 2016, 1, 16014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Nieto, J.; del Cid, M.A.G.; Cárcer, I.A.; Baeza, A. Inorganic Porous Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery in Antitumoral Therapy. Biotechnology Journal 2021, 16, 2000150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danhier, F. To exploit the tumor microenvironment: Since the EPR effect fails in the clinic, what is the future of nanomedicine? Journal of Controlled Release 2016, 244, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danhier, F.; Feron, O.; Préat, V. To exploit the tumor microenvironment: Passive and active tumor targeting of nanocarriers for anti-cancer drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2010, 148, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maso, K.; Grigoletto, A.; Vicent, M.J.; Pasut, G. Molecular platforms for targeted drug delivery. In; 2019; pp. 1–50.

- Mitchell, M.J.; Billingsley, M.M.; Haley, R.M.; Wechsler, M.E.; Peppas, N.A.; Langer, R. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2021, 20, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschwind, A.; Fischer, O.M.; Ullrich, A. The discovery of receptor tyrosine kinases: targets for cancer therapy. Nature Reviews Cancer 2004, 4, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, D.S.; Van Etten, R.A. Tyrosine Kinases as Targets for Cancer Therapy. New England Journal of Medicine 2005, 353, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, N.; Bhattacharya, S.; Steele, R.; Ray, R.B. Anti-miR-203 suppresses ER-positive breast cancer growth and stemness by targeting SOCS3. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 58595–58605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupaimoole, R.; Slack, F.J. MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2017, 16, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. V; Ajay, A.K.; Mohammad, N.; Malvi, P.; Chaube, B.; Meena, A.S.; Bhat, M.K. Proteasomal inhibition sensitizes cervical cancer cells to mitomycin C-induced bystander effect: the role of tumor microenvironment. Cell Death & Disease 2015, 6, e1934–e1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soave, C.L.; Guerin, T.; Liu, J.; Dou, Q.P. Targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system for cancer treatment: discovering novel inhibitors from nature and drug repurposing. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews 2017, 36, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

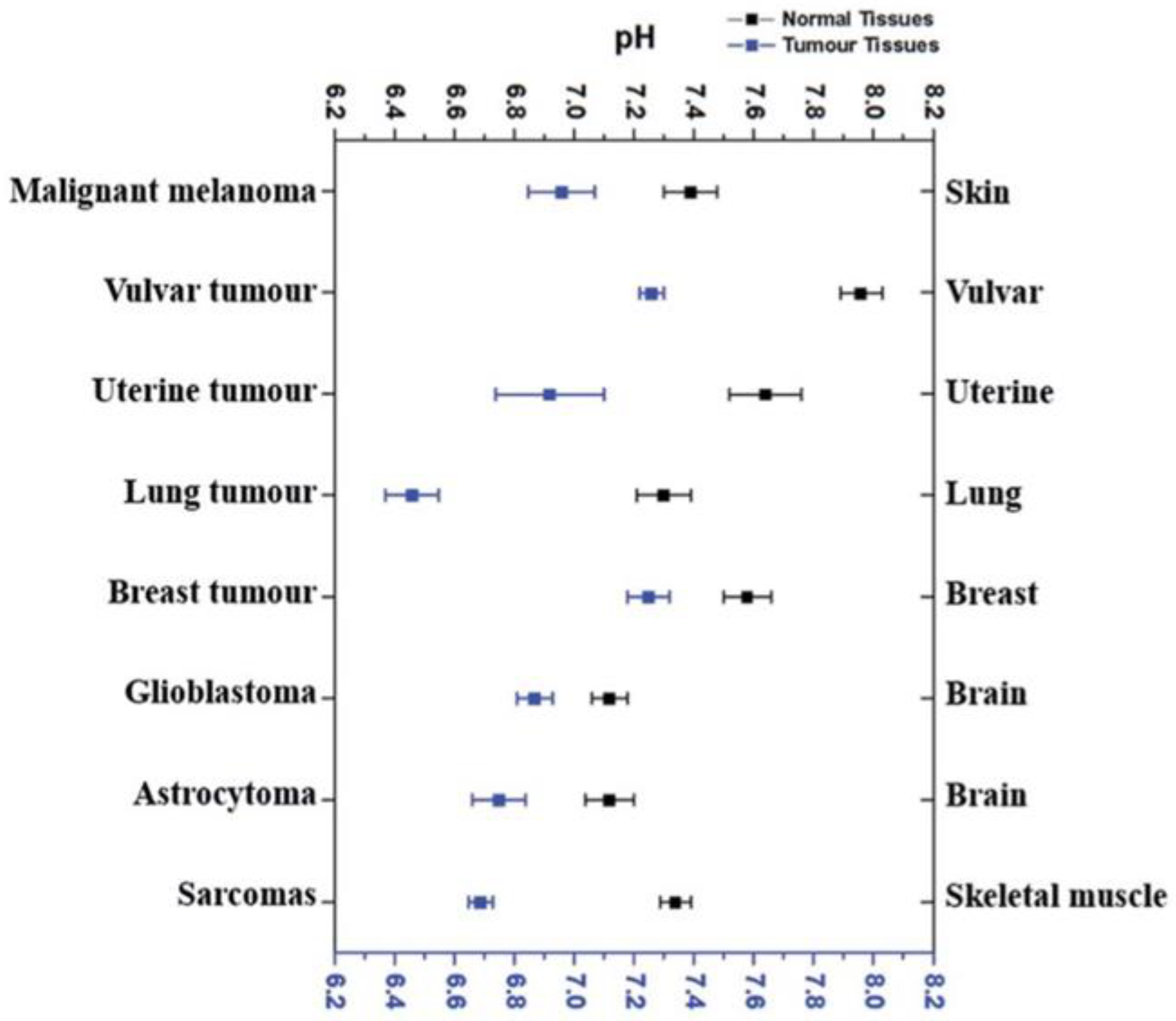

- Lee, S.-H.; Griffiths, J.R. How and Why Are Cancers Acidic? Carbonic Anhydrase IX and the Homeostatic Control of Tumour Extracellular pH. Cancers 2020, 12, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Li, H.; Hu, X.; Abdullah, R.; Xie, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, M.; Luo, Q.; Li, Y.; Sun, Z.; et al. Size-Tunable Assemblies Based on Ferrocene-Containing DNA Polymers for Spatially Uniform Penetration. Chem 2019, 5, 1775–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, H.; Matsumoto, Y.; Mizuno, K.; Chen, Q.; Murakami, M.; Kimura, M.; Terada, Y.; Kano, M.R.; Miyazono, K.; Uesaka, M.; et al. Accumulation of sub-100 nm polymeric micelles in poorly permeable tumours depends on size. Nature Nanotechnology 2011, 6, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RUSU, V.; NG, C.; WILKE, M.; TIERSCH, B.; FRATZL, P.; PETER, M. Size-controlled hydroxyapatite nanoparticles as self-organized organic?inorganic composite materials. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5414–5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abri Aghdam, M.; Bagheri, R.; Mosafer, J.; Baradaran, B.; Hashemzaei, M.; Baghbanzadeh, A.; de la Guardia, M.; Mokhtarzadeh, A. Recent advances on thermosensitive and pH-sensitive liposomes employed in controlled release. Journal of Controlled Release 2019, 315, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, P.; Mao, G.; Yin, T.; Zhong, D.; Yiming, B.; Hu, X.; Jia, Z.; Nian, G.; Qu, S.; et al. Dual pH-Responsive Hydrogel Actuator for Lipophilic Drug Delivery. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 12010–12017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; He, J.; Liu, R.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, J. Chitosan capped pH-responsive hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles for targeted chemo-photo combination therapy. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 231, 115706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Liu, G.; Tao, W.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X.; He, F.; Pan, J.; Mei, L.; Pan, G. A Drug-Self-Gated Mesoporous Antitumor Nanoplatform Based on pH-Sensitive Dynamic Covalent Bond. Advanced Functional Materials 2017, 27, 1605985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Yang, K.; Liu, F.; Li, H.; Xu, Y.; Sun, S. Diverse gatekeepers for mesoporous silica nanoparticle based drug delivery systems. Chemical Society Reviews 2017, 46, 6024–6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, J.; Zhou, C.; Sun, J. pH-sensitive polymeric micelles triggered drug release for extracellular and intracellular drug targeting delivery. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2013, 8, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.K.; Islam, M.R.; Choudhury, Z.S.; Mostafa, A.; Kadir, M.F. Nanotechnology based approaches in cancer therapeutics. Advances in Natural Sciences: Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 2014, 5, 043001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hu, C.; Shao, L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: present situation and prospects for the future. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2017, Volume 12, 1227–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodzinski, A.; Guduru, R.; Liang, P.; Hadjikhani, A.; Stewart, T.; Stimphil, E.; Runowicz, C.; Cote, R.; Altman, N.; Datar, R.; et al. Targeted and controlled anticancer drug delivery and release with magnetoelectric nanoparticles. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 20867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Shen, X. Charge-reversal nanocarriers: An emerging paradigm for smart cancer nanomedicine. Journal of Controlled Release 2020, 319, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.; Chan, W.C.W. Effect of Gold Nanoparticle Aggregation on Cell Uptake and Toxicity. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 5478–5489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K. Aggregation and toxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in aquatic environment—A Review. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 2009, 44, 1485–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morarasu, S.; Morarasu, B.C.; Ghiarasim, R.; Coroaba, A.; Tiron, C.; Iliescu, R.; Dimofte, G.-M. Targeted Cancer Therapy via pH-Functionalized Nanoparticles: A Scoping Review of Methods and Outcomes. Gels 2022, 8, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallinowski, F.; Vaupel, P. Factors governing hyperthermia-induced pH changes in Yoshida sarcomas. International Journal of Hyperthermia 1989, 5, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swietach, P.; Patiar, S.; Supuran, C.T.; Harris, A.L.; Vaughan-Jones, R.D. The Role of Carbonic Anhydrase 9 in Regulating Extracellular and Intracellular pH in Three-dimensional Tumor Cell Growths. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009, 284, 20299–20310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swietach, P.; Wigfield, S.; Cobden, P.; Supuran, C.T.; Harris, A.L.; Vaughan-Jones, R.D. Tumor-associated Carbonic Anhydrase 9 Spatially Coordinates Intracellular pH in Three-dimensional Multicellular Growths. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008, 283, 20473–20483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, G.; Xu, Z.P.; Li, L. Manipulating extracellular tumour pH: an effective target for cancer therapy. RSC Advances 2018, 8, 22182–22192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeslund, J.; Swenson, K.-E. Investigations on the pH of Malignant Tumours in Mice and Humans after the Administration of Glucose. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1953, 32, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, B.S. pH STUDIES IN HUMAN MALIGNANT TUMOURS. The Lancet 1966, 288, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampus, F. Die Wasserstoffionenkonzentration des Hirngewebes bei raumfordernden intracraniellen Prozessen. Acta Neurochirurgica 1963, 11, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mürdter, T.E.; Friedel, G.; Backman, J.T.; McClellan, M.; Schick, M.; Gerken, M.; Bosslet, K.; Fritz, P.; Toomes, H.; Kroemer, H.K.; et al. Dose Optimization of a Doxorubicin Prodrug (HMR 1826) in Isolated Perfused Human Lungs: Low Tumor pH Promotes Prodrug Activation by β-Glucuronidase. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2002, 301, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Berg, A.P.; Wike-Hooley, J.L.; Van Den Berg-Block, A.F.; Van Der Zee, J.; Reinhold, H.S. Tumour pH in human mammary carcinoma. European Journal of Cancer and Clinical Oncology 1982, 18, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thistlethwaite, A.J.; Leeper, D.B.; Moylan, D.J.; Nerlinger, R.E. pH distribution in human tumors. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 1985, 11, 1647–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wike-Hooley, J.L.; van den Berg, A.P.; van der Zee, J.; Reinhold, H.S. Human tumour pH and its variation. European Journal of Cancer and Clinical Oncology 1985, 21, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, B.A.; Chimenti, M.; Jacobson, M.P.; Barber, D.L. Dysregulated pH: a perfect storm for cancer progression. Nature Reviews Cancer 2011, 11, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, A.; Akaboshi, H.; Ogura, T.; Aikawa, T.; Kondo, T.; Tobori, N.; Yuasa, M. Preparation of pH-sensitive Anionic Liposomes Designed for Drug Delivery System (DDS) Application. Journal of Oleo Science 2015, 64, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, N.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, L.; Yin, F.; Jia, Q.; Wang, M.; Chu, Y.; et al. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous metal-organic frameworks based codelivery system of doxorubicin/acetazolamide for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. Clinical and Translational Medicine 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuba, E.; Sugahara, Y.; Yoshizaki, Y.; Shimizu, T.; Kasai, M.; Udaka, K.; Kono, K. Carboxylated polyamidoamine dendron-bearing lipid-based assemblies for precise control of intracellular fate of cargo and induction of antigen-specific immune responses. Biomaterials Science 2021, 9, 3076–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamala, M.; Palmer, B.D.; Ghandehari, H.; Wilson, W.R.; Wu, Z. PEG-Benzaldehyde-Hydrazone-Lipid Based PEG-Sheddable pH-Sensitive Liposomes: Abilities for Endosomal Escape and Long Circulation. Pharmaceutical Research 2018, 35, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayamajhi, S.; Marchitto, J.; Nguyen, T.D.T.; Marasini, R.; Celia, C.; Aryal, S. pH-responsive cationic liposome for endosomal escape mediated drug delivery. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2020, 188, 110804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

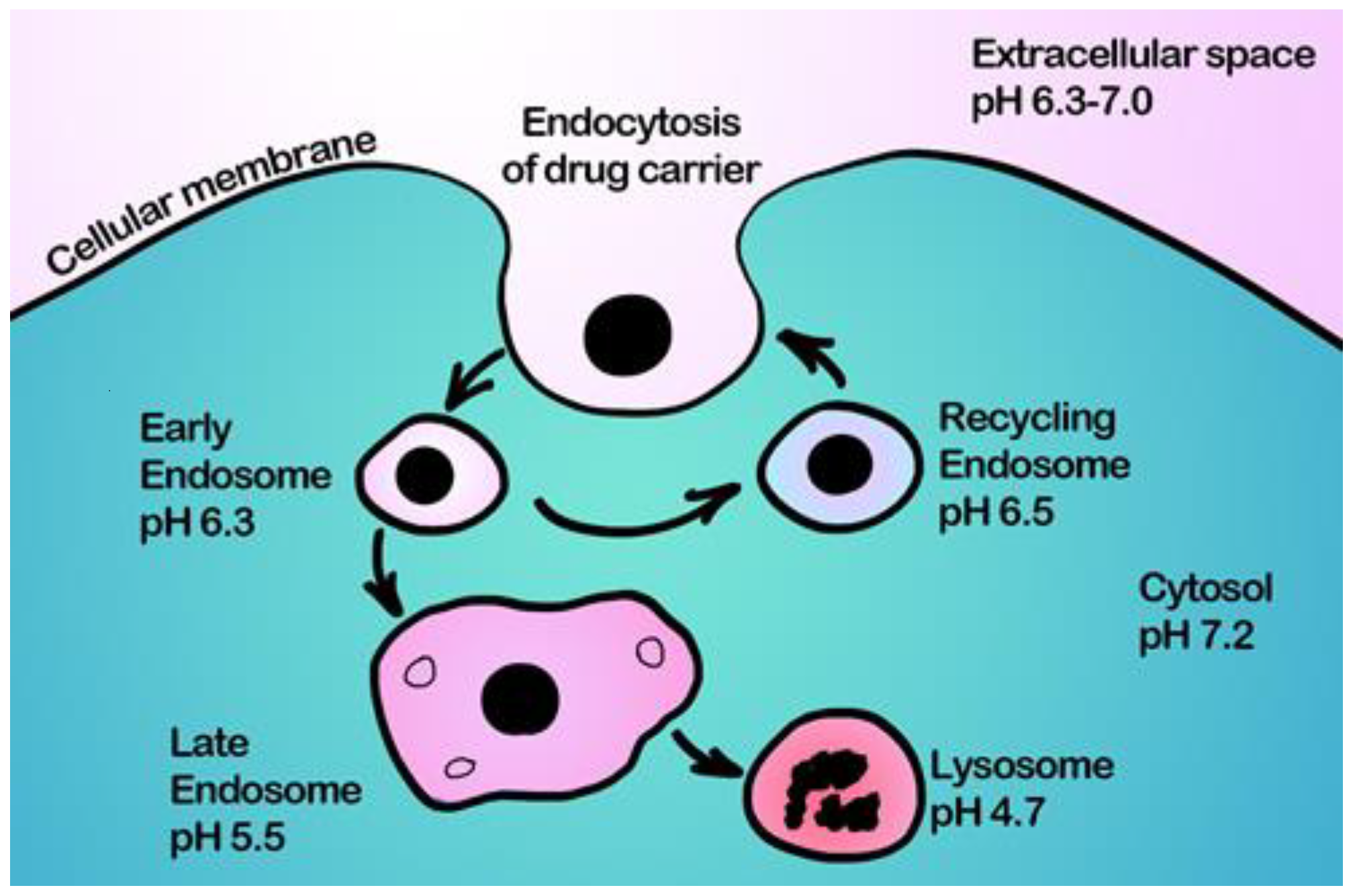

- Kermaniyan, S.S.; Chen, M.; Zhang, C.; Smith, S.A.; Johnston, A.P.R.; Such, C.; Such, G.K. Understanding the Biological Interactions of pH-Swellable Nanoparticles. Macromolecular Bioscience 2022, 22, 2100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-García, P.D.; Retamal, J.S.; Shenoy, P.; Imlach, W.; Sykes, M.; Truong, N.; Constandil, L.; Pelissier, T.; Nowell, C.J.; Khor, S.Y.; et al. A pH-responsive nanoparticle targets the neurokinin 1 receptor in endosomes to prevent chronic pain. Nature Nanotechnology 2019, 14, 1150–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Rietz, H.; Hedlund, H.; Wilhelmson, S.; Nordenfelt, P.; Wittrup, A. Imaging small molecule-induced endosomal escape of siRNA. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, I.B.; Fletcher, R.B.; McBride, J.R.; Weiss, S.M.; Duvall, C.L. Tuning Composition of Polymer and Porous Silicon Composite Nanoparticles for Early Endosome Escape of Anti-microRNA Peptide Nucleic Acids. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 39602–39611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Tan, P.; Fu, S.; Tian, X.; Zhang, H.; Ma, X.; Gu, Z.; Luo, K. Preparation and application of pH-responsive drug delivery systems. Journal of Controlled Release 2022, 348, 206–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, M.A.; Glorioso, J.C.; Naldini, L. Viral vectors for gene therapy: the art of turning infectious agents into vehicles of therapeutics. Nature Medicine 2001, 7, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagache, T.; Danos, O.; Holcman, D. Modeling the Step of Endosomal Escape during Cell Infection by a Nonenveloped Virus. Biophysical Journal 2012, 102, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.P.; Lorenz, A.; Dahlman, J.; Sahay, G. Challenges in carrier-mediated intracellular delivery: moving beyond endosomal barriers. WIREs Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2016, 8, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lächelt, U.; Wagner, E. Nucleic Acid Therapeutics Using Polyplexes: A Journey of 50 Years (and Beyond). Chemical Reviews 2015, 115, 11043–11078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkouhi, A.K.; Scholte, M.; Storm, G.; Haisma, H.J. Endosomal escape pathways for delivery of biologicals. Journal of Controlled Release 2011, 151, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Khan, J.M.; Haque, S. Strategies in the design of endosomolytic agents for facilitating endosomal escape in nanoparticles. Biochimie 2019, 160, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Wang, H.; Yi, K.; Lv, S.; Hu, H.; Li, M.; Tao, Y. Applications of Nanobiomaterials in the Therapy and Imaging of Acute Liver Failure. Nano-Micro Letters 2021, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Q.; Wilhelm, S.; Ding, D.; Syed, A.M.; Sindhwani, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.Y.; MacMillan, P.; Chan, W.C.W. Quantifying the Ligand-Coated Nanoparticle Delivery to Cancer Cells in Solid Tumors. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 8423–8435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.; Liu, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, S.; Deng, L.; Dong, A.; Zhang, J. PEG- b -PCL Copolymer Micelles with the Ability of pH-Controlled Negative-to-Positive Charge Reversal for Intracellular Delivery of Doxorubicin. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 4281–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, H.; Nakamura, H.; Fang, J. The EPR effect for macromolecular drug delivery to solid tumors: Improvement of tumor uptake, lowering of systemic toxicity, and distinct tumor imaging in vivo. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2013, 65, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, N.; Wu, J.; Xu, X.; Kamaly, N.; Farokhzad, O.C. Cancer nanotechnology: The impact of passive and active targeting in the era of modern cancer biology. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2014, 66, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, H.; Ito, E.; Akita, H.; Oishi, M.; Nagasaki, Y.; Futaki, S.; Harashima, H. A pH-sensitive fusogenic peptide facilitates endosomal escape and greatly enhances the gene silencing of siRNA-containing nanoparticles in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Controlled Release 2009, 139, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remaut, K.; Lucas, B.; Braeckmans, K.; Demeester, J.; De Smedt, S.C. Pegylation of liposomes favours the endosomal degradation of the delivered phosphodiester oligonucleotides. Journal of Controlled Release 2007, 117, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, R.; Yang, J.; Shi, Y.; Ma, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X. Enhanced retention and anti-tumor efficacy of liposomes by changing their cellular uptake and pharmacokinetics behavior. Biomaterials 2015, 41, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, H.; Akita, H.; Harashima, H. The Polyethyleneglycol Dilemma: Advantage and Disadvantage of PEGylation of Liposomes for Systemic Genes and Nucleic Acids Delivery to Tumors. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2013, 36, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Y. Nanotechnology applied to overcome tumor drug resistance. Journal of Controlled Release 2012, 162, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleige, E.; Quadir, M.A.; Haag, R. Stimuli-responsive polymeric nanocarriers for the controlled transport of active compounds: Concepts and applications. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2012, 64, 866–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganta, S.; Devalapally, H.; Shahiwala, A.; Amiji, M. A review of stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug and gene delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2008, 126, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, X.; Hu, H.; Sun, Y.; Yu, B.; Cong, H.; Shen, Y. The Intracellular and Extracellular Microenvironment of Tumor Site: The Trigger of Stimuli-Responsive Drug Delivery Systems. Small Methods 2022, 6, 2101437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindhwani, S.; Syed, A.M.; Ngai, J.; Kingston, B.R.; Maiorino, L.; Rothschild, J.; MacMillan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Rajesh, N.U.; Hoang, T.; et al. The entry of nanoparticles into solid tumours. Nature Materials 2020, 19, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.K.; Stylianopoulos, T. Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2010, 7, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, J.W.; Bae, Y.H. EPR: Evidence and fallacy. Journal of Controlled Release 2014, 190, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, D.; Joshi, N.; Tao, W.; Karp, J.M.; Peer, D. Progress and challenges towards targeted delivery of cancer therapeutics. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Rao, L.; Yao, H.; Wang, Z.; Ning, P.; Chen, X. Engineering Macrophages for Cancer Immunotherapy and Drug Delivery. Advanced Materials 2020, 32, 2002054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhu, D.; Wang, Q.; Chen, B.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q. Cancer cell membrane-camouflaged MOF nanoparticles for a potent dihydroartemisinin-based hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. RSC Advances 2020, 10, 7194–7205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Huang, J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, S.; Guan, X.; Yi, M.; Li, S.; Zhang, L. Bioinspired metal–organic frameworks mediated efficient delivery of siRNA for cancer therapy. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 426, 131926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Herrero, E.; Fernández-Medarde, A. Advanced targeted therapies in cancer: Drug nanocarriers, the future of chemotherapy. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2015, 93, 52–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, R.; Takizawa, T.; Kuwata, Y.; Mutoh, M.; Ishiguro, N.; Utoguchi, N.; Shinohara, A.; Eriguchi, M.; Yanagie, H.; Maruyama, K. Effective anti-tumor activity of oxaliplatin encapsulated in transferrin–PEG-liposome. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2008, 346, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamot, C.; Drummond, D.C.; Noble, C.O.; Kallab, V.; Guo, Z.; Hong, K.; Kirpotin, D.B.; Park, J.W. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor–Targeted Immunoliposomes Significantly Enhance the Efficacy of Multiple Anticancer Drugs In vivo. Cancer Research 2005, 65, 11631–11638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, H.S.; Park, T.G. Folate receptor targeted biodegradable polymeric doxorubicin micelles. Journal of Controlled Release 2004, 96, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Luo, F.; Pan, Y.; Hou, C.; Ren, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide conjugated poly(lactic acid)-poly(ethylene oxide) micelle for targeted drug delivery. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2008, 85A, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Wei, H.; Zhu, J.-L.; Chang, C.; Cheng, H.; Li, C.; Cheng, S.-X.; Zhang, X.-Z.; Zhuo, R.-X. Functionalized Thermoresponsive Micelles Self-Assembled from Biotin-PEG- b -P(NIPAAm- co -HMAAm)- b -PMMA for Tumor Cell Target. Bioconjugate Chemistry 2008, 19, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.F.; Alves, C.G.; Lima-Sousa, R.; Moreira, A.F.; de Melo-Diogo, D.; Correia, I.J. Inorganic-based drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. In Advances and Avenues in the Development of Novel Carriers for Bioactives and Biological Agents; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Danhier, F.; Vroman, B.; Lecouturier, N.; Crokart, N.; Pourcelle, V.; Freichels, H.; Jérôme, C.; Marchand-Brynaert, J.; Feron, O.; Préat, V. Targeting of tumor endothelium by RGD-grafted PLGA-nanoparticles loaded with Paclitaxel. Journal of Controlled Release 2009, 140, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.; Lee, J.H.; Sahu, A.; Tae, G. The synergistic effect of folate and RGD dual ligand of nanographene oxide on tumor targeting and photothermal therapy in vivo. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 18584–18594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Bi, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, R.; He, F.; Gai, S.; et al. Hyaluronic acid-targeted and pH-responsive drug delivery system based on metal-organic frameworks for efficient antitumor therapy. Biomaterials 2019, 223, 119473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Metal–Organic Framework-Based Nanoplatform for Intracellular Environment-Responsive Endo/Lysosomal Escape and Enhanced Cancer Therapy. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2018, 10, 31998–32005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Li, Z.; Guo, C.; Huang, X.; Kang, M.; Song, Y.; He, L.; Zhou, N.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; et al. PEGMA-modified bimetallic NiCo Prussian blue analogue doped with Tb(III) ions: Efficiently pH-responsive and controlled release system for anticancer drug. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 389, 124468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Stylianopoulos, T.; Cui, J.; Martin, J.; Chauhan, V.P.; Jiang, W.; Popović, Z.; Jain, R.K.; Bawendi, M.G.; Fukumura, D. Multistage nanoparticle delivery system for deep penetration into tumor tissue. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 2426–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izci, M.; Maksoudian, C.; Manshian, B.B.; Soenen, S.J. The Use of Alternative Strategies for Enhanced Nanoparticle Delivery to Solid Tumors. Chemical Reviews 2021, 121, 1746–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelepukin, I. V.; Griaznova, O.Y.; Shevchenko, K.G.; Ivanov, A. V.; Baidyuk, E. V.; Serejnikova, N.B.; Volovetskiy, A.B.; Deyev, S.M.; Zvyagin, A. V. Flash drug release from nanoparticles accumulated in the targeted blood vessels facilitates the tumour treatment. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parakhonskiy, B. V.; Shilyagina, N.Y.; Gusliakova, О.I.; Volovetskiy, A.B.; Kostyuk, A.B.; Balalaeva, I. V.; Klapshina, L.G.; Lermontova, S.A.; Tolmachev, V.; Orlova, A.; et al. A method of drug delivery to tumors based on rapidly biodegradable drug-loaded containers. Applied Materials Today 2021, 25, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.L.; Wang, B.; Wilson, K.E.; Bayer, C.L.; Chen, Y.-S.; Kim, S.; Homan, K.A.; Emelianov, S.Y. Advances in clinical and biomedical applications of photoacoustic imaging. Expert Opinion on Medical Diagnostics 2010, 4, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, L. Driving forces for drug loading in drug carriers. Journal of Microencapsulation 2015, 32, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczuk, A.; Trzcinska, R.; Trzebicka, B.; Müller, A.H.E.; Dworak, A.; Tsvetanov, C.B. Loading of polymer nanocarriers: Factors, mechanisms and applications. Progress in Polymer Science 2014, 39, 43–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Cai, X.; Sun, C.; Liang, S.; Shao, S.; Huang, S.; Cheng, Z.; Pang, M.; Xing, B.; Kheraif, A.A. Al; et al. O 2 -Loaded pH-Responsive Multifunctional Nanodrug Carrier for Overcoming Hypoxia and Highly Efficient Chemo-Photodynamic Cancer Therapy. Chemistry of Materials 2019, 31, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, D.; Li, H.; Xi, W.; Wang, Z.; Bednarkiewicz, A.; Dibaba, S.T.; Shi, L.; Sun, L. Heterodimers made of metal–organic frameworks and upconversion nanoparticles for bioimaging and pH-responsive dual-drug delivery. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2020, 8, 1316–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, S.-B.; Sarrafzadeh, M.-H.; Salami, M.; Khorramizadeh, M.R. A pH-sensitive delivery system based on N-succinyl chitosan-ZnO nanoparticles for improving antibacterial and anticancer activities of curcumin. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 151, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavnhøj, C.G.; Knopp, M.M.; Madsen, C.M.; Löbmann, K. The role interplay between mesoporous silica pore volume and surface area and their effect on drug loading capacity. International Journal of Pharmaceutics: X 2019, 1, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Kulkarni, S.; Vincent, A.P.; Nannuri, S.H.; George, S.D.; Mutalik, S. Hyaluronic acid-drug conjugate modified core-shell MOFs as pH responsive nanoplatform for multimodal therapy of glioblastoma. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2020, 588, 119735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi Ghezeli, Z.; Hekmati, M.; Veisi, H. Synthesis of Imatinib-loaded chitosan-modified magnetic nanoparticles as an anti-cancer agent for pH responsive targeted drug delivery. Applied Organometallic Chemistry 2019, 33, e4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abazari, R.; Mahjoub, A.R.; Ataei, F.; Morsali, A.; Carpenter-Warren, C.L.; Mehdizadeh, K.; Slawin, A.M.Z. Chitosan Immobilization on Bio-MOF Nanostructures: A Biocompatible pH-Responsive Nanocarrier for Doxorubicin Release on MCF-7 Cell Lines of Human Breast Cancer. Inorganic Chemistry 2018, 57, 13364–13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, M.; Sadhukhan, P.; Ghosh, N.; Chatterjee, S.; Manna, P.; Das, J.; Sil, P.C. pH-responsive and targeted delivery of curcumin via phenylboronic acid-functionalized ZnO nanoparticles for breast cancer therapy. Journal of Advanced Research 2019, 18, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés-Funes, H.; Coronado, C. Role of anthracyclines in the era of targeted therapy. Cardiovascular Toxicology 2007, 7, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunene, S.C.; Lin, K.-S.; Weng, M.-T.; Carrera Espinoza, M.J.; Wu, C.-M. In vitro study of doxorubicin-loaded thermo- and pH-tunable carriers for targeted drug delivery to liver cancer cells. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2021, 104, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, H.; Wang, C.; Qi, J.; Liu, K.; Cao, R.; Zheng, H. A protein@metal–organic framework nanocomposite for pH-triggered anticancer drug delivery. Dalton Transactions 2018, 47, 10223–10228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, C.; Collinson, A.; Matthews, C.; Pointon, A.; Jenkinson, L.; Minter, R.R.; Vaughan, T.J.; Tigue, N.J. Exosomal delivery of doxorubicin enables rapid cell entry and enhanced in vitro potency. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0214545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pooresmaeil, M.; Asl, E.A.; Namazi, H. A new pH-sensitive CS/Zn-MOF@GO ternary hybrid compound as a biofriendly and implantable platform for prolonged 5-Fluorouracil delivery to human breast cancer cells. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2021, 885, 160992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, P.; Marchal, J.A.; Boulaiz, H.; Carrillo, E.; Vélez, C.; Rodríguez-Serrano, F.; Melguizo, C.; Prados, J.; Madeddu, R.; Aranega, A. 5-Fluorouracil derivatives: a patent review. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 2012, 22, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raduly, F.; Raditoiu, V.; Raditoiu, A.; Purcar, V. Curcumin: Modern Applications for a Versatile Additive. Coatings 2021, 11, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan-On, S.; Dilokthornsakul, P.; Tiyaboonchai, W. Trends in advanced oral drug delivery system for curcumin: A systematic review. Journal of Controlled Release 2022, 348, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethiya, A.; Agarwal, D.K.; Agarwal, S. Current Trends in Drug Delivery System of Curcumin and its Therapeutic Applications. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 20, 1190–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Zhu, M.; Dong, Y.; Feng, T.; Chen, Z.; Feng, Y.; Shan, Z.; Xu, J.; Meng, S. An integrated targeting drug delivery system based on the hybridization of graphdiyne and MOFs for visualized cancer therapy. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 11709–11718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimohammadi, E.; Maleki, R.; Akbarialiabad, H.; Dahri, M. Novel pH-responsive nanohybrid for simultaneous delivery of doxorubicin and paclitaxel: an in-silico insight. BMC Chemistry 2021, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilalis, P.; Tziveleka, L.-A.; Varlas, S.; Iatrou, H. pH-Sensitive nanogates based on poly( <scp>l</scp> -histidine) for controlled drug release from mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Polymer Chemistry 2016, 7, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Liu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y. Drug Loaded Nanoparticles of Metal-Organic Frameworks with High Colloidal Stability for Anticancer Application. Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology 2019, 15, 1754–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Chi, B.; Tian, F.; Xu, M.; Xu, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, J. Prussian Blue modified Metal Organic Frameworks for imaging guided synergetic tumor therapy with hypoxia modulation. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2021, 853, 157329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, H.; Sun, K.; Hu, J.; Chen, F.; Liu, W.; Chen, J.; Sun, B.; Hossain, A.M.S. A novel pH-responsive Fe-MOF system for enhanced cancer treatment mediated by the Fenton reaction. New Journal of Chemistry 2021, 45, 3271–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wan, W.; Guo, P.; Nyström, A.M.; Zou, X. One-pot Synthesis of Metal–Organic Frameworks with Encapsulated Target Molecules and Their Applications for Controlled Drug Delivery. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2016, 138, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.-Z.; Zhu, D.; Zhu, X.-H.; Wang, B.; Yang, Y.-S.; Sun, W.-X.; Wang, X.-M.; Lv, P.-C.; Wang, Z.-C.; Zhu, H.-L. Nanoscale Metal–Organic-Frameworks Coated by Biodegradable Organosilica for pH and Redox Dual Responsive Drug Release and High-Performance Anticancer Therapy. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2019, 11, 20678–20688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.-Y.; Qin, C.; Wang, X.-L.; Yang, G.-S.; Shao, K.-Z.; Lan, Y.-Q.; Su, Z.-M.; Huang, P.; Wang, C.-G.; Wang, E.-B. Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 as efficient pH-sensitive drug delivery vehicle. Dalton Transactions 2012, 41, 6906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, J.; Hou, J.; Feng, X.; Zhu, W. MOF nanoparticles with encapsulated dihydroartemisinin as a controlled drug delivery system for enhanced cancer therapy and mechanism analysis. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2020, 8, 7382–7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Ding, S.; Wang, X.; Lei, Q.; Fang, W. FA-PEG decorated MOF nanoparticles as a targeted drug delivery system for controlled release of an autophagy inhibitor. Biomaterials Science 2018, 6, 2582–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X.; Wang, F. DNAzyme-Loaded Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) for Self-Sufficient Gene Therapy. Angewandte Chemie 2019, 131, 7458–7462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, C.L.; Nguyen, T.T. Van; Nguyen, T.; Hoang, T.C. Synthesis, characterization and adsorption ability of UiO-66-NH 2. Advances in Natural Sciences: Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 2015, 6, 025004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; He, Q.; Lv, M.; Xu, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, X.; Wei, F. Selective adsorption of cationic dyes by UiO-66-NH2. Applied Surface Science 2015, 327, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranji-Burachaloo, H.; Karimi, F.; Xie, K.; Fu, Q.; Gurr, P.A.; Dunstan, D.E.; Qiao, G.G. MOF-Mediated Destruction of Cancer Using the Cell’s Own Hydrogen Peroxide. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2017, 9, 33599–33608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, H.; Chen, H.; Xu, X.; Gao, X.; Liang, Z.; Sun, Y.; et al. Hollow Mesoporous Silica@Metal-Organic Framework and Applications for pH-Responsive Drug Delivery. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Liang, X.; Wang, T.; Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Wang, C. Tailored synthesis of hollow MOF/polydopamine Janus nanoparticles for synergistic multi-drug chemo-photothermal therapy. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 378, 122175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharehdaghi, Z.; Rahimi, R.; Naghib, S.M.; Molaabasi, F. Cu (II)-porphyrin metal–organic framework/graphene oxide: synthesis, characterization, and application as a pH-responsive drug carrier for breast cancer treatment. JBIC Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry 2021, 26, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Q.; Li, Z.; Guo, C.; Huang, X.; Song, Y.; Zhou, N.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; He, L.; Du, M. A γ-cyclodextrin-based metal–organic framework embedded with graphene quantum dots and modified with PEGMA via SI-ATRP for anticancer drug delivery and therapy. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 20956–20967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, K.; Cao, X. Hierarchical MOF-on-MOF Architecture for pH/GSH-Controlled Drug Delivery and Fe-Based Chemodynamic Therapy. Inorganic Chemistry 2022, 61, 3281–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Song, K.; Cao, Y.; Peng, C.; Yang, G. Keratin-Templated Synthesis of Metallic Oxide Nanoparticles as MRI Contrast Agents and Drug Carriers. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2018, 10, 26039–26045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.-Y.; Zhang, H.-J.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Gao, E.-Q. Dual functions of pH-sensitive cation Zr-MOF for 5-Fu: large drug-loading capacity and high-sensitivity fluorescence detection. Dalton Transactions 2021, 50, 10524–10532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Sheng, Z.; Wang, J. A Biocompatible Zinc(II)-based Metal-organic Framework for pH Responsive Drug Delivery and Anti-Lung Cancer Activity. Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie 2018, 644, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, Q.; He, J.; Vriesekoop, F.; Liang, H. Crystal-Seeded Growth of pH-Responsive Metal–Organic Frameworks for Enhancing Encapsulation, Stability, and Bioactivity of Hydrophobicity Compounds. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2019, 5, 6581–6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Bigdeli, B.; Jalili-baleh, L.; Baharifar, H.; Akrami, M.; Dehghani, S.; Goliaei, B.; Amani, A.; Lotfabadi, A.; Rashedi, H.; et al. Curcumin-lipoic acid conjugate as a promising anticancer agent on the surface of gold-iron oxide nanocomposites: A pH-sensitive targeted drug delivery system for brain cancer theranostics. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2018, 114, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera-García, A.; Checa-Chavarria, E.; Rivero-Buceta, E.; Moreno, V.; Fernández, E.; Botella, P. Amino modified metal-organic frameworks as pH-responsive nanoplatforms for safe delivery of camptothecin. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2019, 541, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathishkumar, P.; Li, Z.; Govindan, R.; Jayakumar, R.; Wang, C.; Long Gu, F. Zinc oxide-quercetin nanocomposite as a smart nano-drug delivery system: Molecular-level interaction studies. Applied Surface Science 2021, 536, 147741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Meng, X.; Yang, Z.; Dong, H.; Zhang, X. Enhanced cancer therapy by hypoxia-responsive copper metal-organic frameworks nanosystem. Biomaterials 2020, 258, 120278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnabel, J.; Ettlinger, R.; Bunzen, H. Zn-MOF-74 as pH-Responsive Drug-Delivery System of Arsenic Trioxide. ChemNanoMat 2020, 6, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Yang, J.; Qian, Y.; Deng, H.; Wang, Z.; Ma, S.; Wei, Y.; Yang, N.; Shen, Q. Ferroptosis/pyroptosis dual-inductive combinational anti-cancer therapy achieved by transferrin decorated nanoMOF. Nanoscale Horizons 2021, 6, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. , P.; R., M.A.; R., A.; G., A.; N.M., P.; A., P.; N., S. Ecofriendly one pot fabrication of methyl gallate@ZIF-L nanoscale hybrid as pH responsive drug delivery system for lung cancer therapy. Process Biochemistry 2019, 84, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Kong, L. Chitosan-Modified PLGA Nanoparticles with Versatile Surface for Improved Drug Delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech 2013, 14, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsila, F.; Bikádi, Z.; Simonyi, M. Molecular basis of the Cotton effects induced by the binding of curcumin to human serum albumin. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2003, 14, 2433–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bami, M.S.; Raeisi Estabragh, M.A.; Khazaeli, P.; Ohadi, M.; Dehghannoudeh, G. pH-responsive drug delivery systems as intelligent carriers for targeted drug therapy: Brief history, properties, synthesis, mechanism and application. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2022, 70, 102987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, M.; McSheehy, P.M. .; Griffiths, J.R.; Bashford, C.L. Causes and consequences of tumour acidity and implications for treatment. Molecular Medicine Today 2000, 6, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, S.; Nicolas, J.; Couvreur, P. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery. Nature Materials 2013, 12, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayun, B.; Lin, X.; Choi, H.-J. Challenges and Recent Progress in Oral Drug Delivery Systems for Biopharmaceuticals. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.P.; Gandhi, V. V.; Singh, B.G.; Kunwar, A. Passive and Active Drug Targeting: Role of Nanocarriers in Rational Design of Anticancer Formulations. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2019, 25, 3034–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, M.F.; Anton, N.; Wallyn, J.; Omran, Z.; Vandamme, T.F. An overview of active and passive targeting strategies to improve the nanocarriers efficiency to tumour sites. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2019, 71, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.; Khurana, S.; Choudhari, R.; Kesari, K.K.; Kamal, M.A.; Garg, N.; Ruokolainen, J.; Das, B.C.; Kumar, D. Specific targeting cancer cells with nanoparticles and drug delivery in cancer therapy. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2021, 69, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torchilin, V.P. Passive and Active Drug Targeting: Drug Delivery to Tumors as an Example. In; 2010; pp. 3–53.

- Ali, E.S.; Sharker, S.M.; Islam, M.T.; Khan, I.N.; Shaw, S.; Rahman, M.A.; Uddin, S.J.; Shill, M.C.; Rehman, S.; Das, N.; et al. Targeting cancer cells with nanotherapeutics and nanodiagnostics: Current status and future perspectives. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2021, 69, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, J.; An, S.; Jiang, C. pH-sensitive drug-delivery systems for tumor targeting. Therapeutic Delivery 2013, 4, 1499–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wike-Hooley, J.L.; Haveman, J.; Reinhold, H.S. The relevance of tumour pH to the treatment of malignant disease. Radiotherapy and Oncology 1984, 2, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, M.; Souri, M.; Moradi Kashkooli, F. Effects of hypoxia and nanocarrier size on pH-responsive nano-delivery system to solid tumors. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 19350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-R.; Kuppler, R.J.; Zhou, H.-C. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal–organic frameworks. Chemical Society Reviews 2009, 38, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, J.; Wen, N.; Xiong, H.; Cai, S.; He, Q.; Hu, Y.; Peng, D.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y. Metal-organic frameworks for stimuli-responsive drug delivery. Biomaterials 2020, 230, 119619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.-M.; Dong, H.; Zhang, X.; Sun, X.-J.; Liu, M.; Yang, D.-D.; Liu, X.; Wei, J.-Z. Postsynthetic Modification of ZIF-90 for Potential Targeted Codelivery of Two Anticancer Drugs. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2017, 9, 27332–27337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Dou, W.; Caro, J. Steam-Stable Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework ZIF-90 Membrane with Hydrogen Selectivity through Covalent Functionalization. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2010, 132, 15562–15564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, Y.; Sun, S.; Li, Z.; Wu, A.; Zeng, L. pH-Responsive metal–organic framework encapsulated gold nanoclusters with modulated release to enhance photodynamic therapy/chemotherapy in breast cancer. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2020, 8, 1739–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Wang, H.; Zhu, D.; Wan, Y.; Yin, L. Combined effects of avasimibe immunotherapy, doxorubicin chemotherapy, and metal–organic frameworks nanoparticles on breast cancer. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2020, 235, 4814–4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovitt, C.; Shelper, T.; Avery, V. Advanced Cell Culture Techniques for Cancer Drug Discovery. Biology 2014, 3, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Präbst, K.; Engelhardt, H.; Ringgeler, S.; Hübner, H. Basic Colorimetric Proliferation Assays: MTT, WST, and Resazurin. In; 2017; pp. 1–17.

- Ramirez, C.N.; Antczak, C.; Djaballah, H. Cell viability assessment: toward content-rich platforms. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 2010, 5, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykul, S.; Martinez-Hackert, E. Determination of half-maximal inhibitory concentration using biosensor-based protein interaction analysis. Analytical Biochemistry 2016, 508, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biological evaluation of medical devices —Part 5: Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity. In ANSI/AAMI/ISO 10993-5:2009/(R)2014; Biological evaluation of medical devices —Part 5: Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity; AAMI, 2009.

- Dong, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z. Facile preparation of metal−organic frameworks-based hydrophobic anticancer drug delivery nanoplatform for targeted and enhanced cancer treatment. Talanta 2019, 194, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockert, J.C.; Horobin, R.W.; Colombo, L.L.; Blázquez-Castro, A. Tetrazolium salts and formazan products in Cell Biology: Viability assessment, fluorescence imaging, and labeling perspectives. Acta Histochemica 2018, 120, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiyama, M. A highly water-soluble disulfonated tetrazolium salt as a chromogenic indicator for NADH as well as cell viability. Talanta 1997, 44, 1299–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tominaga, H.; Ishiyama, M.; Ohseto, F.; Sasamoto, K.; Hamamoto, T.; Suzuki, K.; Watanabe, M. A water-soluble tetrazolium salt useful for colorimetric cell viability assay. Analytical Communications 1999, 36, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginouves, M.; Carme, B.; Couppie, P.; Prevot, G. Comparison of Tetrazolium Salt Assays for Evaluation of Drug Activity against Leishmania spp. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2014, 52, 2131–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riss, T.L.; Moravec, R.A.; Niles, A.L.; Duellman, S.; Benink, H.A.; Worzella, T.J.; Minor, L. Cell Viability Assays, 2004.

- Huo, D.; Liu, S.; Zhang, C.; He, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Y. Hypoxia-Targeting, Tumor Microenvironment Responsive Nanocluster Bomb for Radical-Enhanced Radiotherapy. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 10159–10174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Teng, X.; Chen, D.; Tang, F.; He, J. The effect of the shape of mesoporous silica nanoparticles on cellular uptake and cell function. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chithrani, B.D.; Ghazani, A.A.; Chan, W.C.W. Determining the Size and Shape Dependence of Gold Nanoparticle Uptake into Mammalian Cells. Nano Letters 2006, 6, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Akita, H.; Yamada, Y.; Hatakeyama, H.; Harashima, H. A Multifunctional Envelope-type Nanodevice for Use in Nanomedicine: Concept and Applications. Accounts of Chemical Research 2012, 45, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-Z.; Du, J.-Z.; Dou, S.; Mao, C.-Q.; Long, H.-Y.; Wang, J. Sheddable Ternary Nanoparticles for Tumor Acidity-Targeted siRNA Delivery. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, Z.; Chang, D.; Zhao, X.; Hammond, P.T. Layer-by-Layer Nanoparticles with a pH-Sheddable Layer for in Vivo Targeting of Tumor Hypoxia. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 4284–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, T.B.; Nicol, F.; Zelphati, O.; Scaria, P. V.; Plank, C.; Szoka, F.C. Design, Synthesis, and Characterization of a Cationic Peptide That Binds to Nucleic Acids and Permeabilizes Bilayers. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 3008–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.D.; Wiradharma, N.; Liu, S.Q.; Zhang, L.J.; Khan, M.; Qian, Y.; Yang, Y.-Y. Oligomerized alpha-helical KALA peptides with pendant arms bearing cell-adhesion, DNA-binding and endosome-buffering domains as efficient gene transfection vectors. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6284–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbarao, N.K.; Parente, R.A.; Szoka, F.C.; Nadasdi, L.; Pongracz, K. The pH-dependent bilayer destabilization by an amphipathic peptide. Biochemistry 1987, 26, 2964–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouahab, A.; Cheraga, N.; Onoja, V.; Shen, Y.; Tu, J. Novel pH-sensitive charge-reversal cell penetrating peptide conjugated PEG-PLA micelles for docetaxel delivery: In vitro study. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2014, 466, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Song, L.; Su, Y.; Zhu, L.; Pang, Y.; Qiu, F.; Tong, G.; Yan, D.; Zhu, B.; Zhu, X. Oxime Linkage: A Robust Tool for the Design of pH-Sensitive Polymeric Drug Carriers. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 3460–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sykes, E.A.; Dai, Q.; Sarsons, C.D.; Chen, J.; Rocheleau, J. V.; Hwang, D.M.; Zheng, G.; Cramb, D.T.; Rinker, K.D.; Chan, W.C.W. Tailoring nanoparticle designs to target cancer based on tumor pathophysiology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Wei, G.; Su, Z. Biomedical and bioactive engineered nanomaterials for targeted tumor photothermal therapy: A review. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2019, 104, 109891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, C.; Shi, J. Nanoplatform-based cascade engineering for cancer therapy. Chemical Society Reviews 2020, 49, 9057–9094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Tang, C.; Yin, C. Estrone-modified pH-sensitive glycol chitosan nanoparticles for drug delivery in breast cancer. Acta Biomaterialia 2018, 73, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanikumar, L.; Al-Hosani, S.; Kalmouni, M.; Nguyen, V.P.; Ali, L.; Pasricha, R.; Barrera, F.N.; Magzoub, M. pH-responsive high stability polymeric nanoparticles for targeted delivery of anticancer therapeutics. Communications Biology 2020, 3, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, S.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liang, F.; Song, S. Hyaluronic-Acid-Based pH-Sensitive Nanogels for Tumor-Targeted Drug Delivery. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2017, 3, 2410–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-J.; Du, J.-Z.; Du, X.-J.; Xu, C.-F.; Sun, C.-Y.; Wang, H.-X.; Cao, Z.-T.; Yang, X.-Z.; Zhu, Y.-H.; Nie, S.; et al. Stimuli-responsive clustered nanoparticles for improved tumor penetration and therapeutic efficacy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 4164–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Thayumanavan, S. Importance of Evaluating Dynamic Encapsulation Stability of Amphiphilic Assemblies in Serum. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 4163–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palanikumar, L.; Choi, E.S.; Oh, J.Y.; Park, S.A.; Choi, H.; Kim, K.; Kim, C.; Ryu, J.-H. Importance of Encapsulation Stability of Nanocarriers with High Drug Loading Capacity for Increasing in Vivo Therapeutic Efficacy. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 3030–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. Nanoparticles in the clinic: An update. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, C.; Pan, S.; Shi, M.; Li, J.; Hu, H.; Qiao, M.; Chen, D.; Zhao, X. Eph A10-modified pH-sensitive liposomes loaded with novel triphenylphosphine–docetaxel conjugate possess hierarchical targetability and sufficient antitumor effect both in vitro and in vivo. Drug Delivery 2018, 25, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momekova, D.; Rangelov, S.; Lambov, N. Long-Circulating, pH-Sensitive Liposomes. In; 2017; pp. 209–226.

- Nunes, S.S.; de Oliveira Silva, J.; Fernandes, R.S.; Miranda, S.E.M.; Leite, E.A.; de Farias, M.A.; Portugal, R.V.; Cassali, G.D.; Townsend, D.M.; Oliveira, M.C.; et al. PEGylated versus Non-PEGylated pH-Sensitive Liposomes: New Insights from a Comparative Antitumor Activity Study. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Deore, S.V.; Ghadi, R.; Chaudhari, D.; Kuche, K.; Katiyar, S.S. Tumor microenvironment responsive VEGF-antibody functionalized pH sensitive liposomes of docetaxel for augmented breast cancer therapy. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2021, 121, 111832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheybi, F.; Alavizadeh, S.H.; Rezayat, S.M.; Hatamipour, M.; Akhtari, J.; Faridi Majidi, R.; Badiee, A.; Jaafari, M.R. pH-Sensitive PEGylated Liposomal Silybin: Synthesis, In Vitro and In Vivo Anti-Tumor Evaluation. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2021, 110, 3919–3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Cui, W.; Zong, Z.; Tan, Y.; Xu, C.; Cao, J.; Lai, T.; Tang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Sui, X.; et al. A facile method for anti-cancer drug encapsulation into polymersomes with a core-satellite structure. Drug Delivery 2022, 29, 2414–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Silva, J.; Fernandes, R.S.; Ramos Oda, C.M.; Ferreira, T.H.; Machado Botelho, A.F.; Martins Melo, M.; de Miranda, M.C.; Assis Gomes, D.; Dantas Cassali, G.; Townsend, D.M.; et al. Folate-coated, long-circulating and pH-sensitive liposomes enhance doxorubicin antitumor effect in a breast cancer animal model. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2019, 118, 109323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, W.; Jiang, L.; Gu, Y.; Soe, Z.C.; Kim, B.K.; Gautam, M.; Poudel, K.; Pham, L.M.; Phung, C.D.; Chang, J.-H.; et al. Regulatory T Cells Tailored with pH-Responsive Liposomes Shape an Immuno-Antitumor Milieu against Tumors. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2019, 11, 36333–36346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; He, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Yan, R.; Ye, P.; et al. Co-delivery of doxorubicin and imatinib by pH sensitive cleavable PEGylated nanoliposomes with folate-mediated targeting to overcome multidrug resistance. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2018, 542, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Du, Z.; Pan, S.; Shi, M.; Li, J.; Yang, C.; Hu, H.; Qiao, M.; Chen, D.; Zhao, X. Overcoming Multidrug Resistance by Codelivery of MDR1-Targeting siRNA and Doxorubicin Using EphA10-Mediated pH-Sensitive Lipoplexes: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2018, 10, 21590–21600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, P.; Adolphi, N.L.; Wang, Z.; Lin, Y.-S.; Butler, K.S.; Durfee, P.N.; Croissant, J.G.; Noureddine, A.; Coker, E.N.; Bearer, E.L.; et al. Establishing the effects of mesoporous silica nanoparticle properties on in vivo disposition using imaging-based pharmacokinetics. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Guo, J.; Qi, G.; Zhang, M.; Hao, L. pH-Responsive Drug Delivery and Imaging Study of Hybrid Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. Molecules 2022, 27, 6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Fan, X.; Zhu, J.; Wei, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, H.; Wang, B.; Piao, J.; Li, F. Lipid/PAA-coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles for dual-pH-responsive codelivery of arsenic trioxide/paclitaxel against breast cancer cells. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2021, 42, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.; Moitra, P.; Bashir, M.; Kondaiah, P.; Bhattacharya, S. Natural tripeptide capped pH-sensitive gold nanoparticles for efficacious doxorubicin delivery both in vitro and in vivo. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Jiang, L.; Gao, H.; Liu, Z.; Mäkilä, E.; Wang, S.; Saiding, Q.; Xiang, L.; Tang, X.; Shi, M.; et al. A pH-Responsive Cluster Metal–Organic Framework Nanoparticle for Enhanced Tumor Accumulation and Antitumor Effect. Advanced Materials 2022, 34, 2203915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, J.; Ren, F. A multifunctional MOF-based nanohybrid as injectable implant platform for drug synergistic oral cancer therapy. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 390, 124446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Z. Calcium-mineralized polypeptide nanoparticle for intracellular drug delivery in osteosarcoma chemotherapy. Bioactive Materials 2020, 5, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Cao, W.; Xia, F.; Liu, B.; Niu, J.; Alfranca, G.; Sun, X.; Ma, L.; Fuente, J.M. de la; et al. A tumor microenvironment responsive biodegradable CaCO 3 /MnO 2 - based nanoplatform for the enhanced photodynamic therapy and improved PD-L1 immunotherapy. Theranostics 2019, 9, 6867–6884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Active substance |

Test type |

Cell line |

DDS type |

DDS configuration |

24h | 48h | 72h |

Ref. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 | ECCS | IC50 | ECCS | IC50 | ECCS | ||||||

|

Doxorubicin (DOX) |

MTT |

MCF-7 |

MOFs (ZIF-8) |

DOX/HMS@ZIF | ∼0.12 | 1.64 | - | - | - | - | [174] |

| BSA/DOX@ZIF | ∼0.04 | 1.48 | - | - | ∼0.037 | 1.42 | [152] | ||||

|

MOF (NH2-MIL-88B (Fe)) |

DOX@FeMOF | <2.5 | - | - | - | - | - |

[164] |

|||

| DOX@FeMOF@PSS@MV-PAH@PSS | <2.5 | - | - | - | - | - | |||||

|

MOFs (γ-cyclodextrin-based MOF) |

γ-CD-MOF | >90 | - | - | - | - | - |

[177] |

|||

| GQDs@γ-CD-MOF | ∼34.7 | - | - | - | - | - | |||||

| DOX/AS1411@PEGMA@GQDs@ γ-CD-MOF | ∼15.76 | - | - | - | - | - | |||||

| MOF | DOX/CS/BioMOF | ∼2.45 | 1.3 | - | - | - | - | [148] | |||

| MOF (Cu (II)-porphyrin) | Cu(II)-porphyrin/Graphene oxide-DOX | ∼4 | 1.38 | - | - | - | - | [176] | |||

|

HeLa |

MOFs (ZIF-8) |

DOX@ZIF-8 | ∼3 | 1.74 | - | - | - | - | [133] | ||

| DOX@ZIF-8@AS1411 | ∼1.64 | 1.82 | - | - | - | - | |||||

| ZIF-8@DOX@Organosilica | ∼0.34 | 1.18 | - | - | - | - | [166] | ||||

|

MOF (ZIF-90) |

UC@mSiO2@ZIF-DOX-PEGFA | >100 | - | - | - | - | - |

[142] |

|||

| UC@mSiO2-RB@ZIF-DOX-PEGFA + 808 nm laser irradiation |

∼36.7 | 1.6 | - | - | - | - | |||||

| UC@mSiO2-RB@ZIFO2-DOX-PEGFA + 808 nm laser irradiation |

∼15.5 | 2 | - | - | - | - | |||||

| MOFs (UIO-66) | Fe3O4@UIO-66-NH2/Graphdiyne/DOX | ∼20 | 0.62 | ∼9.2 | 0.77 | - | - | [159] | |||

| MOF (Cu (II)-porphyrin) | Cu(II)-porphyrin/Graphene oxide-DOX | ∼14 | 1.16 | - | - | - | - | [176] | |||

|

4T1 |

MOFs (ZIF-8) |

AuNCs@MOF-DOX | ∼9.25 | 0.9 | - | - | - | - |

[208] |

||

| AuNCs@MOF-DOX + 670 nm laser irradiation |

∼6 | 1.29 | - | - | - | - | |||||

|

MOF (ZIF-90) |

UC@mSiO2@ZIF-DOX-PEGFA | >100 | - | - | - | - | - |

[142] |

|||

| UC@mSiO2-RB@ZIF-DOX-PEGFA + 808 nm laser irradiation |

∼56.6 | 1.54 | - | - | - | - | |||||

| UC@mSiO2-RB@ZIFO2-DOX-PEGFA + 808 nm laser irradiation |

∼29.6 | 1.58 | - | - | - | - | |||||

|

MOF (Prussian blue) |

NiCo-PBA@DOX | >140 | - | - | - | - | - |

[134] |

|||

| NiCo-PBA@Tb3+@DOX | >140 | - | - | - | - | - | |||||

| NiCo-PBA@Tb3+@PEGMA@DOX | ∼6.4 | 1.52 | - | - | - | - | |||||

| NiCo-PBA@Tb3+@PEGMA@AS1411@DOX | ∼5.8 | 1.56 | - | - | - | - | |||||

|

A549 |

MOF (NH2-MIL-88B (Fe)) |

DOX@FeMOF | <2.5 | - | - | - | - | - |

[164] |

||

| DOX@FeMOF@PSS@MV-PAH@PSS | <2.5 | - | - | - | - | - | |||||

| HUVEC |

MOF (Cu (II)-porphyrin) |

Cu(II)-porphyrin/Graphene oxide-DOX |

>139.2 | - | - | - | - | - |

[176] |

||

| NIH-3T3 | >139.2 | - | - | - | - | - | |||||

|

WST-8 / CCK-8 |

MCF-7 |

MOF (ZIF-8) |

DOX@ZIF-8/Dex |

>10 | - | - | - | - | - |

[162] |

|

| MCF-7/ADR | 27.7 | 1.4 | - | - | - | - | |||||

|

HeLa |

>10 | - | - | - | - | - | |||||

| MOF | UCMOFs@Dox | ∼1.57 | 1 | - | - | - | - | [143] | |||

|

4T1 |

MOF (NH2-MIL-88B) |

DOX@NH2-MIL-88B | ∼3.5 | - | - | - | - | - |

[178] |

||

| DOX@NH2-MIL-88B-On-NH2-MIL-88B | ∼2.8 | - | - | - | - | - | |||||

|

Fluorouracil (5-Fu) |

MTT |

A549 |

MOF |

5-Fu/[Zn3(BTC)2(Me)(H2O)2](MeOH)13 |

∼45.76 | - | - | - | - | - |

[181] |

| HEK 293 | >171.6 | - | - | - | - | - | |||||