Submitted:

28 April 2023

Posted:

04 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

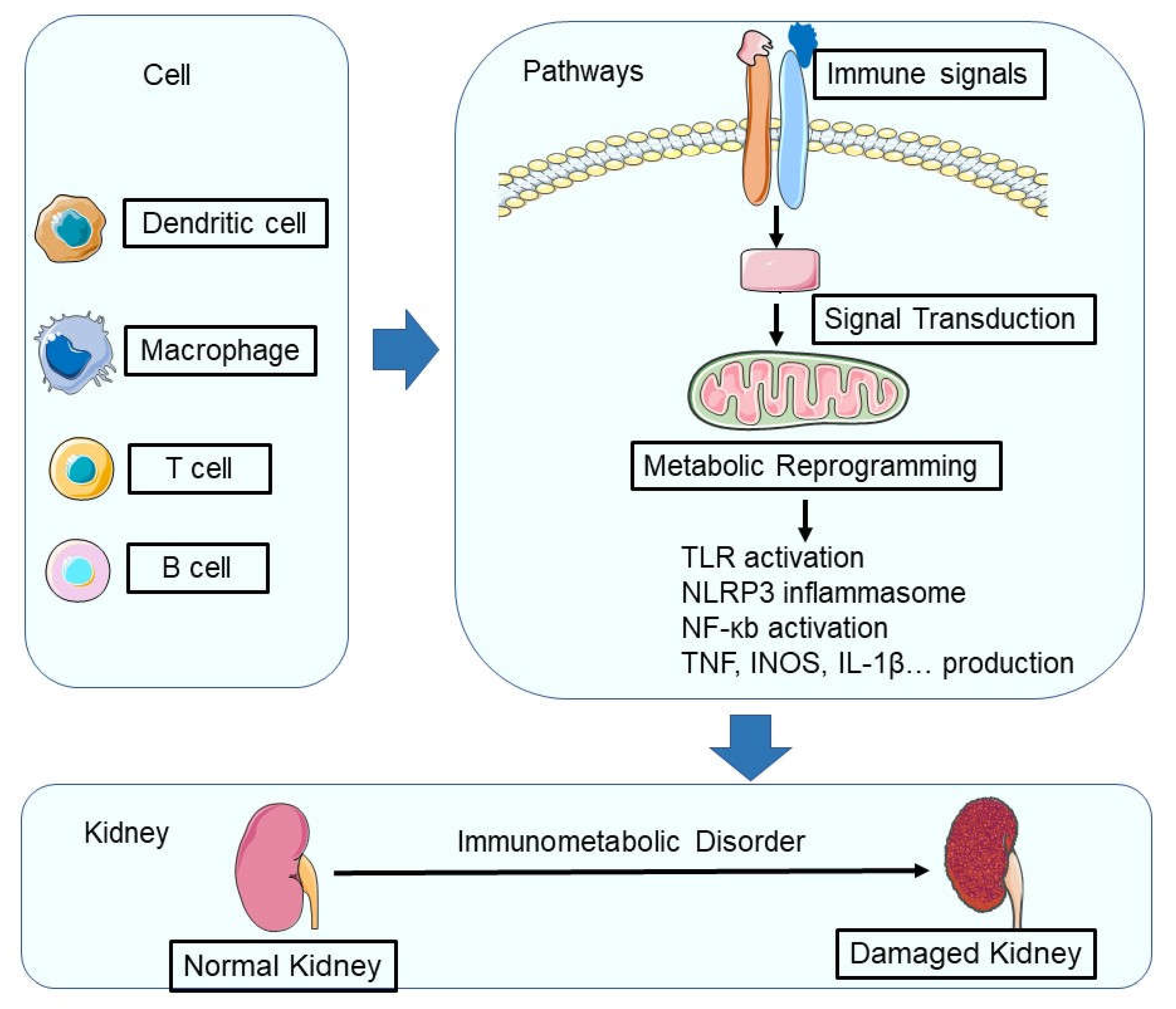

Introduction

I. Immunometabolic alterations in kidney disease

II. The impact of immunometabolic dysregulation in kidney disease

Acute kidney injury (AKI):

Chronic kidney disease (CKD):

Lupus nephritis:

Diabetic nephropathy:

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD):

Impact of immunometabolic dysregulation on kidney transplant outcomes

III. Potential therapeutic interventions targeting immunometabolism in kidney disease

IV. Future directions for research in immunometabolism and kidney disease

- Elucidating the mechanisms of immunometabolic dysregulation in kidney disease: While the role of immunometabolism in kidney disease is becoming increasingly clear, the specific molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying this dysregulation are still not fully understood. Future research should focus on elucidating these mechanisms to better understand how immunometabolic dysregulation contributes to kidney disease pathogenesis.

- Identifying novel immunometabolic targets for therapeutic interventions: While current and emerging immunometabolic therapies for kidney disease show promise, there is a need for the identification of additional immunometabolic targets for therapeutic interventions. Innovative approaches and technologies, such as multi-omics and single-cell analysis, may help identify new targets and pathways involved in immunometabolic dysregulation.

- Personalizing immunometabolic therapies for kidney disease: The heterogeneity of kidney disease suggests that personalized therapeutic approaches may be necessary. Future research should aim to identify specific patient subgroups that may benefit from certain immunometabolic therapies, as well as develop biomarkers to predict treatment response.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaboration, G.B.D.C.K.D. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020; 395: 709-733.

- Speer, T.; Dimmeler, S.; Schunk, S.J.; Fliser, D.; Ridker, P.M. Targeting innate immunity-driven inflammation in CKD and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 762–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An C, Jiao B, Du H, et al. JMJD3 Promotes Myeloid Fibroblast Activation and Macrophage Polarization in Kidney Fibrosis. British journal of pharmacology 2023.

- Pålsson-McDermott, E.M.; O’neill, L.A.J. Targeting immunometabolism as an anti-inflammatory strategy. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Rijt, S.; Leemans, J.C.; Florquin, S.; Houtkooper, R.H.; Tammaro, A. Immunometabolic rewiring of tubular epithelial cells in kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 588–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H. Immunometabolism at the intersection of metabolic signaling, cell fate, and systems immunology. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, P.J.; Andrade-Oliveira, V.; Câmara, N.O.S. Targeting immune cell metabolism in kidney diseases. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2021, 17, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, A.J.; Qu, L.; Karlinsey, K.; Vella, A.T.; Zhou, B. Capturing the multifaceted function of adipose tissue macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1148188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Matz, A.J.; Karlinsey, K.; Cao, Z.; Vella, A.T.; Zhou, B. Macrophages at the Crossroad of Meta-Inflammation and Inflammaging. Genes 2022, 13, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz AJ, Qu L, Karlinsey K, et al. MicroRNA-regulated B cells in obesity. Immunometabolism 2022; 4: e00005.

- Tan, S.M.; Snelson, M.; Østergaard, J.A.; Coughlan, M.T. The Complement Pathway: New Insights into Immunometabolic Signaling in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2022, 37, 781–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, P.C.; Eddy, S.; Taroni, J.N.; Lightfoot, Y.L.; Mariani, L.; Parikh, H.; Lindenmeyer, M.T.; Ju, W.; Greene, C.S.; Godfrey, B.; et al. Metabolic pathways and immunometabolism in rare kidney diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 77, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, B.; An, C.; Du, H.; Tran, M.; Wang, P.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Y. STAT6 Deficiency Attenuates Myeloid Fibroblast Activation and Macrophage Polarization in Experimental Folic Acid Nephropathy. Cells 2021, 10, 3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, B.; An, C.; Tran, M.; Du, H.; Wang, P.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Y. Pharmacological Inhibition of STAT6 Ameliorates Myeloid Fibroblast Activation and Alternative Macrophage Polarization in Renal Fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 735014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Q.; Tang, B.; Zhang, C. Signaling pathways of chronic kidney diseases, implications for therapeutics. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2022; 7: 182.

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Ferroptosis, a Rising Force against Renal Fibrosis. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2022; 2022: 7686956.

- Zhu, Z.; Hu, J.; Chen, Z.; Feng, J.; Yang, X.; Liang, W.; Ding, G. Transition of acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease: role of metabolic reprogramming. Metabolism 2022, 131, 155194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttle, K.R.; Agarwal, R.; Alpers, C.E.; Bakris, G.L.; Brosius, F.C.; Kolkhof, P.; Uribarri, J. Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets for diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2022, 102, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohandes, S.; Doke, T.; Hu, H.; Mukhi, D.; Dhillon, P.; Susztak, K. Molecular pathways that drive diabetic kidney disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlinsey, K.; Qu, L.; Matz, A.J.; Zhou, B. A novel strategy to dissect multifaceted macrophage function in human diseases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2022, 112, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Ma, K.; Tao, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Sai, X.; Li, Y.; Chi, M.; Nian, Q.; Song, L.; et al. A Deep Insight Into Regulatory T Cell Metabolism in Renal Disease: Facts and Perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 826732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Meng, X.-F.; Zhang, C. NLRP3 Inflammasome in Metabolic-Associated Kidney Diseases: An Update. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 714340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlinsey, K.; Matz, A.; Qu, L.; Zhou, B. Extracellular RNAs from immune cells under obesity—a narrative review. ExRNA 2022, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, H.; Couzi, L.; Eberl, M. Unconventional T cells and kidney disease. Nature reviews Nephrology 2021; 17: 795-813.

- Hartzell, S.; Bin, S.; Cantarelli, C.; Haverly, M.; Manrique, J.; Angeletti, A.; La Manna, G.; Murphy, B.; Zhang, W.; Levitsky, J.; et al. Kidney Failure Associates With T Cell Exhaustion and Imbalanced Follicular Helper T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 583702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winterberg, P.D.; Ford, M.L. The effect of chronic kidney disease on T cell alloimmunity. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2017, 22, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Kinsey, G.R. Regulatory T cells in acute and chronic kidney diseases. American journal of physiology Renal physiology 2018; 314: F679-F698.

- Lisowska, K.A.; Storoniak, H.; Dębska-Ślizień, A. T cell subpopulations and cytokine levels in hemodialysis patients. Hum. Immunol. 2022, 83, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Wang, J.; Zang, J.; An, Y.; Dong, Y. The Mechanism of CD8+ T Cells for Reducing Myofibroblasts Accumulation during Renal Fibrosis. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassett, J.M. Re: Renal Trauma: Evaluation by Computerized Tomography, by E. Erturk, J. Sheinfeld, P. L. DiMarco and A. T. K. Cockett, J. Urol., 133: 946–949, 1985. J. Urol. 1987, 137, 1006–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Guo, J.; Moledina, D.G.; Cantley, L.G. Immune-mediated tubule atrophy promotes acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease transition. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, T.; Huang, T.; Lang, Y.; Sheng, Q.; Liu, Y.; Kong, Z.; Gao, Y.; Lu, S.; et al. T cells and their products in diabetic kidney disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1084448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-L.; Tsai, W.-C.; Hung, R.-W.; Chen, I.-Y.; Shu, K.-H.; Pan, S.-Y.; Yang, F.-J.; Ting, T.-T.; Jiang, J.-Y.; Peng, Y.-S.; et al. Emergence of T cell immunosenescence in diabetic chronic kidney disease. Immun. Ageing 2020, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.-Y.; Jia, X.-Y.; Li, J.-N.; Zheng, X.; Ao, J.; Liu, G.; Cui, Z.; Zhao, M.-H. T cell infiltration is associated with kidney injury in patients with anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. Sci. China Life Sci. 2016, 59, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.S.; Susztak, K. Podocytes: the Weakest Link in Diabetic Kidney Disease? Current diabetes reports 2016; 16: 45.

- Kuo HL, Huang CC, Lin TY, et al. IL-17 and CD40 ligand synergistically stimulate the chronicity of diabetic nephropathy. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association 2018; 33: 248-256.

- McGeachy MJ, Bak-Jensen KS, Chen Y, et al. TGF-beta and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain T(H)-17 cell-mediated pathology. Nature immunology 2007; 8: 1390-1397.

- Oleinika, K.; Mauri, C.; Salama, A.D. Effector and regulatory B cells in immune-mediated kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Hernández, V.A.; Romero-Ramírez, S.; Cervantes-Díaz, R.; Carrillo-Vázquez, D.A.; Navarro-Hernandez, I.C.; Whittall-García, L.P.; Absalón-Aguilar, A.; Vargas-Castro, A.S.; Reyes-Huerta, R.F.; Juárez-Vega, G.; et al. CD11c+ T-bet+ CD21hi B Cells Are Negatively Associated With Renal Impairment in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Act as a Marker for Nephritis Remission. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 892241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, W.; Lakkis, F.G.; Chalasani, G. B Cells, Antibodies, and More. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN 2016; 11: 137-154.

- Mannik M, Merrill CE, Stamps LD, et al. Multiple autoantibodies form the glomerular immune deposits in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. The Journal of rheumatology 2003; 30: 1495-1504.

- Hoxha, E.; Reinhard, L.; Stahl, R.A.K. Membranous nephropathy: new pathogenic mechanisms and their clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.J.; Simmons, K.M.; Cambier, J.C. B cells in type 1 diabetes mellitus and diabetic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, W.; Lan, G.; Lin, Z.; Peng, L.; Dai, H. The Role of Regulatory B cells in Kidney Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 683926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Andrikopoulos, S.; MacIsaac, R.J.; Mackay, L.K.; Nikolic-Paterson, D.J.; Torkamani, N.; Zafari, N.; Marin, E.C.S.; I Ekinci, E. Role of the adaptive immune system in diabetic kidney disease. J. Diabetes Investig. 2021, 13, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matz, A.; Qu, L.; Karlinsey, K.; Zhou, B. Impact of microRNA Regulated Macrophage Actions on Adipose Tissue Function in Obesity. Cells 2022, 11, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Qu, L.; Matz, A.J.; Murphy, P.A.; Liu, Y.; Manichaikul, A.W.; Aguiar, D.; Rich, S.S.; Herrington, D.M.; Vu, D.; et al. AtheroSpectrum Reveals Novel Macrophage Foam Cell Gene Signatures Associated With Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Circ. 2021, 145, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Phoon, Y.P.; Karlinsey, K.; Tian, Y.F.; Thapaliya, S.; Thongkum, A.; Qu, L.; Matz, A.J.; Cameron, M.; Cameron, C.; et al. A high OXPHOS CD8 T cell subset is predictive of immunotherapy resistance in melanoma patients. J. Exp. Med. 2022, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li C, Qu L, Farragher C, et al. MicroRNA Regulated Macrophage Activation in Obesity. Journal of translational internal medicine 2019; 7: 46-52.

- Qu, L.; Yu, B.; Li, Z.; Jiang, W.; Jiang, J.; Kong, W. Gastrodin Ameliorates Oxidative Stress and Proinflammatory Response in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease through the AMPK/Nrf2 Pathway. Phytotherapy Res. 2016, 30, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao S, Jiao B, Hong W, et al. [Distribution of KIR/HLA alleles among ethnic Han Chinese patients with hepatocellular carcinoma from southern China]. Zhonghua yi xue yi chuan xue za zhi = Zhonghua yixue yichuanxue zazhi = Chinese journal of medical genetics 2019; 36: 439-442.

- An C, Jia L, Wen J, et al. Targeting Bone Marrow-Derived Fibroblasts for Renal Fibrosis. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2019; 1165: 305-322.

- An, C.; Jiao, B.; Du, H.; Tran, M.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Y. Myeloid PTEN deficiency aggravates renal inflammation and fibrosis in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 237, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, S.; Codrici, E.; Popescu, I.D.; Enciu, A.-M.; Albulescu, L.; Necula, L.G.; Mambet, C.; Anton, G.; Tanase, C. Inflammation-Related Mechanisms in Chronic Kidney Disease Prediction, Progression, and Outcome. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 2180373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynn, T.; Barron, L. Macrophages: Master Regulators of Inflammation and Fibrosis. Semin. Liver Dis. 2010, 30, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu Z, Kuang W, Zhou Q, et al. TGF-beta1 secreted by M2 phenotype macrophages enhances the stemness and migration of glioma cells via the SMAD2/3 signalling pathway. International journal of molecular medicine 2018; 42: 3395-3403.

- Wen, J.; Jiao, B.; Tran, M.; Wang, Y. Pharmacological Inhibition of S100A4 Attenuates Fibroblast Activation and Renal Fibrosis. Cells 2022, 11, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calle, P.; Hotter, G. Macrophage Phenotype and Fibrosis in Diabetic Nephropathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Sato, E.; Mishima, E.; Miyazaki, M.; Tanaka, T. What’s New in the Molecular Mechanisms of Diabetic Kidney Disease: Recent Advances. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, H.-J.; Shirakawa, H. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease. Cells 2022, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamboa, J.L.; Billings, F.T., 4th; Bojanowski, M.T.; Gilliam, L.A.; Yu, C.; Roshanravan, B.; Roberts, L.J., 2nd; Himmelfarb, J.; Ikizler, T.A.; Brown, N.J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in patients with chronic kidney disease. Physiol. Rep. 2016, 4, e12780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irazabal, M.V.; Torres, V.E. Reactive Oxygen Species and Redox Signaling in Chronic Kidney Disease. Cells 2020, 9, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, D.; Capili, A.; Choi, M.E. Mitochondrial dysfunction in kidney injury, inflammation, and disease: Potential therapeutic approaches. Kidney research and clinical practice 2020; 39: 244-258.

- Gyurászová, M.; Gurecká, R.; Bábíčková, J.; Tóthová. Oxidative Stress in the Pathophysiology of Kidney Disease: Implications for Noninvasive Monitoring and Identification of Biomarkers. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5478708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulbul, M.C.; Dagel, T.; Afsar, B.; Ulusu, N.N.; Kuwabara, M.; Covic, A.; Kanbay, M. Disorders of Lipid Metabolism in Chronic Kidney Disease. Blood Purif. 2018, 46, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; He, C.; Afshinnia, F.; Michailidis, G.; Pennathur, S. Lipidomic approaches to dissect dysregulated lipid metabolism in kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Ding, L.; Andoh, V.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. The Mechanism of Hyperglycemia-Induced Renal Cell Injury in Diabetic Nephropathy Disease: An Update. Life 2023, 13, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, C.M.O.; Villar-Delfino, P.H.; Dos Anjos, P.M.F.; Nogueira-Machado, J.A. Cellular death, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and diabetic complications. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, M.; Petroianu, G.; Adem, A. Advanced Glycation End Products and Diabetes Mellitus: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chang, G.-D.; Chen, T.-H.; Chen, W.-L.; Wen, H.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Chang, C.-H. Hyperglycemia and advanced glycation end products (AGEs) suppress the differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 55039–55050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao L, Liang X, Qiao Y, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic tubulopathy. Metabolism: clinical and experimental 2022; 131: 155195.

- Xie, Y.; E, J.; Cai, H.; Zhong, F.; Xiao, W.; Gordon, R.E.; Wang, L.; Zheng, Y.-L.; Zhang, A.; Lee, K.; et al. Reticulon-1A mediates diabetic kidney disease progression through endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial contacts in tubular epithelial cells. Kidney Int. 2022, 102, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, K.; Spanou, L. Acute Kidney Injury: Definition, Pathophysiology and Clinical Phenotypes. The Clinical biochemist Reviews 2016; 37: 85-98.

- Jin, X.; An, C.; Jiao, B.; Safirstein, R.L.; Wang, Y. AMP-activated protein kinase contributes to cisplatin-induced renal epithelial cell apoptosis and acute kidney injury. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2020, 319, F1073–F1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFavers, K. Disruption of Kidney–Immune System Crosstalk in Sepsis with Acute Kidney Injury: Lessons Learned from Animal Models and Their Application to Human Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Xiong, J. The Role of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 Alpha in Renal Disease. Molecules 2022, 27, 7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.-J.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, X.-H.; Li, X.-X.; Liao, W.-T.; Ma, H.-K.; Jiang, M.-D.; Xu, T.-T.; Xu, J.; et al. HIF-1α-BNIP3-mediated mitophagy in tubular cells protects against renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Redox Biol. 2020, 36, 101671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGettrick, A.F.; O’neill, L.A. The Role of HIF in Immunity and Inflammation. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Z.; Cai, J.; Tang, C.; Dong, Z. Hypoxia and Hypoxia-Inducible Factors in Kidney Injury and Repair. Cells 2019, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, W. The crosstalk between hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and microRNAs in acute kidney injury. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 245, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.T.; Scholz, C.C. The effect of HIF on metabolism and immunity. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li ZL, Ji JL, Wen Y, et al. HIF-1alpha is transcriptionally regulated by NF-kappaB in acute kidney injury. American journal of physiology Renal physiology 2021; 321: F225-F235.

- Li, Z.; Li, N. Epigenetic Modification Drives Acute Kidney Injury-to-Chronic Kidney Disease Progression. Nephron 2021, 145, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanemoto, F.; Mimura, I. Therapies Targeting Epigenetic Alterations in Acute Kidney Injury-to-Chronic Kidney Disease Transition. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mimura, I.; Hirakawa, Y.; Kanki, Y.; Kushida, N.; Nakaki, R.; Suzuki, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Aburatani, H.; Nangaku, M. Novel lnc RNA regulated by HIF-1 inhibits apoptotic cell death in the renal tubular epithelial cells under hypoxia. 2017, 5, e13203. [CrossRef]

- Förstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric oxide synthases: regulation and function. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.R.M.B.; Assreuy, J.; Sordi, R. The role of nitric oxide in sepsis-associated kidney injury. Biosci. Rep. 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cong, X.; Miao, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. Inhaled nitric oxide and acute kidney injury risk: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ren. Fail. 2021, 43, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlström, M. Nitric oxide signalling in kidney regulation and cardiometabolic health. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2021, 17, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludes, P.-O.; de Roquetaillade, C.; Chousterman, B.G.; Pottecher, J.; Mebazaa, A. Role of Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Septic Acute Kidney Injury, From Injury to Recovery. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 606622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meissner, M.; Viehmann, S.F.; Kurts, C. DAMPening sterile inflammation of the kidney. Kidney Int. 2019, 95, 489–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez-Carballo C, Guerrero-Hue M, Garcia-Caballero C, et al. Toll-Like Receptors in Acute Kidney Injury. International journal of molecular sciences 2021; 22.

- Liu C, Shen Y, Huang L, et al. TLR2/caspase-5/Panx1 pathway mediates necrosis-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages during acute kidney injury. Cell death discovery 2022; 8: 232.

- Lin, Q.; Li, S.; Jiang, N.; Jin, H.; Shao, X.; Zhu, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, J.; et al. Inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome attenuates apoptosis in contrast-induced acute kidney injury through the upregulation of HIF1A and BNIP3-mediated mitophagy. Autophagy 2020, 17, 2975–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhter, J.; Khan, J.; Baghel, M.; Beg, M.M.A.; Goswami, P.; Afjal, M.A.; Ahmad, S.; Habib, H.; Najmi, A.K.; Raisuddin, S. NLRP3 inflammasome in rosmarinic acid-afforded attenuation of acute kidney injury in mice. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-J.; Lee, D.W.; Ravichandran, K.; Keys, D.O.; Akcay, A.; Nguyen, Q.; He, Z.; Jani, A.; Ljubanovic, D.; Edelstein, C.L. NLRP3 Inflammasome Knockout Mice Are Protected against Ischemic but Not Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2013, 346, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Cui, L.; Li, C.; Zhao, X.; Lai, X.; Li, J.; Lv, T. Serum free fatty acid elevation is related to acute kidney injury in primary nephrotic syndrome. Ren. Fail. 2022, 44, 1237–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Hu, X.; Wei, Q.; Dong, Z. Glucose Metabolism in Acute Kidney Injury and Kidney Repair. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 744122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar D, Singla SK, Puri V, et al. The restrained expression of NF-kB in renal tissue ameliorates folic acid induced acute kidney injury in mice. PloS one 2015; 10: e115947.

- Song N, Thaiss F, Guo L. NFkappaB and Kidney Injury. Frontiers in immunology 2019; 10: 815.

- Halling, J.F.; Pilegaard, H. PGC-1α-mediated regulation of mitochondrial function and physiological implications. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontecha-Barriuso, M.; Martin-Sanchez, D.; Martinez-Moreno, J.M.; Monsalve, M.; Ramos, A.M.; Sanchez-Niño, M.D.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Ortiz, A.; Sanz, A.B. The Role of PGC-1α and Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Kidney Diseases. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, J.; Lu, Y. PGC-1α alleviates mitochondrial dysfunction via TFEB-mediated autophagy in cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Aging 2021, 13, 8421–8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Andres, O.; Suarez-Alvarez, B.; Sánchez-Ramos, C.; Monsalve, M.; Sanchez-Niño, M.D.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Egido, J.; Ortiz, A.; Sanz, A.B. The inflammatory cytokine TWEAK decreases PGC-1α expression and mitochondrial function in acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2016, 89, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, B.Y.; Jhee, J.H.; Park, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, G.; Park, J.T.; Yoo, T.-H.; Kang, S.-W.; Yu, J.-W.; Han, S.H. PGC-1α inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome via preserving mitochondrial viability to protect kidney fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; He, F. Metabolic signatures of immune cells in chronic kidney disease. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2022, 24, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, IH. Vitamin D and glucose metabolism in chronic kidney disease. Current opinion in nephrology and hypertension 2008; 17: 566-572.

- Gupta, N.; Wish, J.B. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitors: A Potential New Treatment for Anemia in Patients With CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2017, 69, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Hou, Y.; Long, M.; Jiang, L.; Du, Y. Molecular mechanisms underlying the role of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α in metabolic reprogramming in renal fibrosis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokas, S.; Larivière, R.; Lamalice, L.; Gobeil, S.; Cornfield, D.N.; Agharazii, M.; Richard, D.E. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 plays a role in phosphate-induced vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Kidney Int. 2016, 90, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilaysane, A.; Chun, J.; Seamone, M.E.; Wang, W.; Chin, R.; Hirota, S.; Li, Y.; Clark, S.A.; Tschopp, J.; Trpkov, K.; et al. The NLRP3 Inflammasome Promotes Renal Inflammation and Contributes to CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 1732–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gai, Z.; Wang, T.; Visentin, M.; Kullak-Ublick, G.A.; Fu, X.; Wang, Z. Lipid Accumulation and Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, K.; Gui, T.; Li, C.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Gai, Z. Recent Progress on Lipid Intake and Chronic Kidney Disease. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 3680397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepe, V.; Libetta, C.; Gregorini, M.; Rampino, T. The innate immune system in human kidney inflammaging. J. Nephrol. 2021, 35, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewinger S, Schumann T, Fliser D, et al. Innate immunity in CKD-associated vascular diseases. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association 2016; 31: 1813-1821.

- Lee, H.; Fessler, M.B.; Qu, P.; Heymann, J.; Kopp, J.B. Macrophage polarization in innate immune responses contributing to pathogenesis of chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang H, Sun SC. NF-kappaB in inflammation and renal diseases. Cell & bioscience 2015; 5: 63.

- Rangan G, Wang Y, Harris D. NF-kappaB signalling in chronic kidney disease. Frontiers in bioscience 2009; 14: 3496-3522.

- Huang G, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, et al. Chronic kidney disease and NLRP3 inflammasome: Pathogenesis, development and targeted therapeutic strategies. Biochemistry and biophysics reports 2023; 33: 101417.

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Z. Effect and Regulation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome During Renal Fibrosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siragy, H.M.; Carey, R.M. Role of the Intrarenal Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System in Chronic Kidney Disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 2010, 31, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudreault-Tremblay, M.M.; Foster, B.J. Benefits of Continuing RAAS Inhibitors in Advanced CKD. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN 2020; 15: 592-593.

- Remuzzi, G.; Perico, N.; Macia, M.; Ruggenenti, P. The role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the progression of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005, 68, S57–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingrosso, D.; Perna, A.F. DNA Methylation Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease. Genes 2020, 11, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Kumagai, N.; Suzuki, N. Alteration of the DNA Methylation Signature of Renal Erythropoietin-Producing Cells Governs the Sensitivity to Drugs Targeting the Hypoxia-Response Pathway in Kidney Disease Progression. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgado-Pascual, J.L.; Marchant, V.; Rodrigues-Diez, R.; Dolade, N.; Suarez-Alvarez, B.; Kerr, B.; Valdivielso, J.M.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Rayego-Mateos, S. Epigenetic Modification Mechanisms Involved in Inflammation and Fibrosis in Renal Pathology. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 2931049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.X.; Fan, L.X.; Zhou, J.X.; Grantham, J.J.; Calvet, J.P.; Sage, J.; Li, X. Lysine methyltransferase SMYD2 promotes cyst growth in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 2751–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, S.; Kahlenberg, J.M. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: New Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Annu. Rev. Med. 2023, 74, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Roach, T.; Morel, L. Immunometabolic alterations in lupus: where do they come from and where do we go from there? Current opinion in immunology 2022; 78: 102245.

- Liu, X.; Du, H.; Sun, Y.; Shao, L. Role of abnormal energy metabolism in the progression of chronic kidney disease and drug intervention. Ren. Fail. 2022, 44, 790–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornoni, A.; Merscher, S. Lipid Metabolism Gets in a JAML during Kidney Disease. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 903–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberti, M.V.; Locasale, J.W. The Warburg Effect: How Does it Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends in biochemical sciences 2016; 41: 211-218.

- Sun, Q.; Chen, X.; Ma, J.; Peng, H.; Wang, F.; Zha, X.; Wang, Y.; Jing, Y.; Yang, H.; Chen, R.; et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin up-regulation of pyruvate kinase isoenzyme type M2 is critical for aerobic glycolysis and tumor growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 4129–4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, N.; Zhuang, S. Macrophages in Renal Injury, Repair, Fibrosis Following Acute Kidney Injury and Targeted Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 934299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scuron MD, Fay BL, Connell AJ, et al. The PI3Kdelta inhibitor parsaclisib ameliorates pathology and reduces autoantibody formation in preclinical models of systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjӧgren's syndrome. International immunopharmacology 2021; 98: 107904.

- Ripoll E, de Ramon L, Draibe Bordignon J, et al. JAK3-STAT pathway blocking benefits in experimental lupus nephritis. Arthritis research & therapy 2016; 18: 134.

- Zhao, W.; Wu, C.; Li, L.-J.; Fan, Y.-G.; Pan, H.-F.; Tao, J.-H.; Leng, R.-X.; Ye, D.-Q. RNAi Silencing of HIF-1α Ameliorates Lupus Development in MRL/lpr Mice. Inflammation 2018, 41, 1717–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira CB, Lima CAD, Vajgel G, et al. The Role of NLRP3 Inflammasome in Lupus Nephritis. International journal of molecular sciences 2021; 22.

- Wu, D.; Ai, L.; Sun, Y.; Yang, B.; Chen, S.; Wang, Q.; Kuang, H. Role of NLRP3 Inflammasome in Lupus Nephritis and Therapeutic Targeting by Phytochemicals. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 621300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pestka, J.J.; Akbari, P.; Wierenga, K.A.; Bates, M.A.; Gilley, K.N.; Wagner, J.G.; Lewandowski, R.P.; Rajasinghe, L.D.; Chauhan, P.S.; Lock, A.L.; et al. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Intervention Against Established Autoimmunity in a Murine Model of Toxicant-Triggered Lupus. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 653464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pestka, J.J.; Vines, L.L.; Bates, M.A.; He, K.; Langohr, I. Comparative Effects of n-3, n-6 and n-9 Unsaturated Fatty Acid-Rich Diet Consumption on Lupus Nephritis, Autoantibody Production and CD4+ T Cell-Related Gene Responses in the Autoimmune NZBWF1 Mouse. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.J.; Theros, J.; Reed, T.J.; Liu, J.; Grigorova, I.L.; Martínez-Colón, G.; Jacob, C.O.; Hodgin, J.B.; Kahlenberg, J.M. TLR7-Mediated Lupus Nephritis Is Independent of Type I IFN Signaling. J. Immunol. 2018, 201, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Ren, Y.; He, X. IFN-I Mediates Lupus Nephritis From the Beginning to Renal Fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 676082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarapu, S.K.; Anders, H.J. Toll-like receptors in lupus nephritis. Journal of biomedical science 2018; 25: 35.

- He LY, Niu SQ, Yang CX, et al. Cordyceps proteins alleviate lupus nephritis through modulation of the STAT3/mTOR/NF-small ka, CyrillicB signaling pathway. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2023; 309: 116284.

- Zou L, Sun L, Hua R, et al. Degradation of Ubiquitin-Editing Enzyme A20 following Autophagy Activation Promotes RNF168 Nuclear Translocation and NF-kappaB Activation in Lupus Nephritis. Journal of innate immunity 2023; 15: 428-441.

- Karasawa T, Sato R, Imaizumi T, et al. Glomerular endothelial expression of type I IFN-stimulated gene, DExD/H-Box helicase 60 via toll-like receptor 3 signaling: possible involvement in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis. Renal failure 2022; 44: 137-145.

- Dunlap, G.S.; Billi, A.C.; Xing, X.; Ma, F.; Maz, M.P.; Tsoi, L.C.; Wasikowski, R.; Hodgin, J.B.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Kahlenberg, J.M.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals distinct effector profiles of infiltrating T cells in lupus skin and kidney. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao YP, Tseng FY, Chao CW, et al. NLRP12 is an innate immune checkpoint for repressing IFN signatures and attenuating lupus nephritis progression. The Journal of clinical investigation 2023; 133.

- Zumaquero E, Stone SL, Scharer CD, et al. IFNgamma induces epigenetic programming of human T-bet(hi) B cells and promotes TLR7/8 and IL-21 induced differentiation. eLife 2019; 8.

- Sagoo, M.K.; Gnudi, L. Diabetic Nephropathy: An Overview. Methods in molecular biology 2020; 2067: 3-7.

- Wang, X.; Zhao, L.; Ajay, A.K.; Jiao, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Gao, X.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, W.J. QiDiTangShen Granules Activate Renal Nutrient-Sensing Associated Autophagy in db/db Mice. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanajou, D.; Haghjo, A.G.; Argani, H.; Aslani, S. AGE-RAGE axis blockade in diabetic nephropathy: Current status and future directions. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 833, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, H.; Gilbert, V.; Liu, Q.; Kapitsinou, P.P.; Unger, T.L.; Rha, J.; Rivella, S.; Schlöndorff, D.; Haase, V.H. Myeloid Cell-Derived Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Attenuates Inflammation in Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction-Induced Kidney Injury. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 5106–5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai IT, Wu CC, Hung WC, et al. FABP1 and FABP2 as markers of diabetic nephropathy. International journal of medical sciences 2020; 17: 2338-2345.

- Sieber, J.; Jehle, A.W. Free Fatty Acids and Their Metabolism Affect Function and Survival of Podocytes. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomita Y, Lee D, Tsubota K, et al. PPARalpha Agonist Oral Therapy in Diabetic Retinopathy. Biomedicines 2020; 8.

- Hu Y, Chen Y, Ding L, et al. Pathogenic role of diabetes-induced PPAR-alpha down-regulation in microvascular dysfunction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013; 110: 15401-15406.

- Ding, S.; Xu, S.; Ma, Y.; Liu, G.; Jang, H.; Fang, J. Modulatory Mechanisms of the NLRP3 Inflammasomes in Diabetes. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan L, Bai X, Zhou Q, et al. The advanced glycation end-products (AGEs)/ROS/NLRP3 inflammasome axis contributes to delayed diabetic corneal wound healing and nerve regeneration. International journal of biological sciences 2022; 18: 809-825.

- Shi, X.; Jiao, B.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, L. MxA is a positive regulator of type I IFN signaling in HCV infection. J. Med Virol. 2017, 89, 2173–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiao, B.; Yao, M.; Shi, X.; Zheng, Z.; Li, S.; Chen, L. ISG12a inhibits HCV replication and potentiates the anti-HCV activity of IFN-α through activation of the Jak/STAT signaling pathway independent of autophagy and apoptosis. Virus Res. 2017, 227, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Li, S.; Holmes, J.A.; Tu, Z.; Li, Y.; Cai, D.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Yang, C.; Jiao, B.; et al. MicroRNA 130a Regulates both Hepatitis C Virus and Hepatitis B Virus Replication through a Central Metabolic Pathway. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e02009–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Ye H, Li S, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus inhibits exogenous Type I IFN signaling pathway through its NSs invitro. PloS one 2017; 12: e0172744.

- Li, Y.; Li, S.; Duan, X.; Chen, Y.; Jiao, B.; Ye, H.; Yao, M.; Chen, L. Interferon-Stimulated Gene 15 Conjugation Stimulates Hepatitis B Virus Production Independent of Type I Interferon Signaling PathwayIn Vitro. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 7417648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, B.; Shi, X.; Chen, Y.; Ye, H.; Yao, M.; Hong, W.; Li, S.; Duan, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Insulin receptor substrate-4 interacts with ubiquitin-specific protease 18 to activate the Jak/STAT signaling pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 105923–105935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan Y, Jiao B, Qu L, et al. The development of COVID-19 treatment. Frontiers in immunology 2023; 14: 1125246.

- Chen, D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Lin, H.; Guo, H.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, W.; Lu, R.; et al. JAK/STAT pathway promotes the progression of diabetic kidney disease via autophagy in podocytes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 902, 174121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, L.-L.; Feng, Y.; Wu, M.; Wang, B.; Li, Z.-L.; Zhong, X.; Wu, W.-J.; Chen, J.; Ni, H.-F.; Tang, T.-T.; et al. Exosomal miRNA-19b-3p of tubular epithelial cells promotes M1 macrophage activation in kidney injury. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu M, Wang H, Chen J, et al. Sinomenine improve diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting fibrosis and regulating the JAK2/STAT3/SOCS1 pathway in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Life sciences 2021; 265: 118855.

- Riwanto, M.; Kapoor, S.; Rodriguez, D.; Edenhofer, I.; Segerer, S.; Wüthrich, R.P. Inhibition of Aerobic Glycolysis Attenuates Disease Progression in Polycystic Kidney Disease. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0146654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podrini, C.; Cassina, L.; Boletta, A. Metabolic reprogramming and the role of mitochondria in polycystic kidney disease. Cell. Signal. 2020, 67, 109495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Kleczko, E.K.; Dwivedi, N.; Monaghan, M.-L.T.; Gitomer, B.Y.; Chonchol, M.B.; Clambey, E.T.; Nemenoff, R.A.; Klawitter, J.; Hopp, K. The tryptophan-metabolizing enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 regulates polycystic kidney disease progression. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swenson-Fields, K.I.; Ward, C.J.; Lopez, M.E.; Fross, S.; Dillon, A.L.H.; Meisenheimer, J.D.; Rabbani, A.J.; Wedlock, E.; Basu, M.K.; Jansson, K.P.; et al. Caspase-1 and the inflammasome promote polycystic kidney disease progression. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 971219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raptis, V.; Loutradis, C.; Boutou, A.K.; Faitatzidou, D.; Sioulis, A.; Ferro, C.J.; Papagianni, A.; Sarafidis, P.A. Serum Copeptin, NLPR3, and suPAR Levels among Patients with Autosomal-Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease with and without Impaired Renal Function. Cardiorenal Med. 2020, 10, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, S.; Masola, V.; Zoratti, E.; Scupoli, M.T.; Baruzzi, A.; Messa, M.; Sallustio, F.; Gesualdo, L.; Lupo, A.; Zaza, G. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Dialyzed Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0122272–e0122272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleczko, E.K.; Marsh, K.H.; Tyler, L.C.; Furgeson, S.B.; Bullock, B.L.; Altmann, C.J.; Miyazaki, M.; Gitomer, B.Y.; Harris, P.C.; Weiser-Evans, M.C.; et al. CD8+ T cells modulate autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease progression. Kidney Int. 2018, 94, 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.-L.; He, Y.-R.; Liu, Y.-J.; He, H.-Y.; Gu, Z.-Y.; Liu, Y.-M.; Liu, W.-J.; Luo, Z.; Ju, M.-J. The immunomodulation role of Th17 and Treg in renal transplantation. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1113560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimine, N.; Turka, L.A.; Priyadharshini, B. Navigating T-Cell Immunometabolism in Transplantation. Transplantation 2018, 102, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, D.T.B.; Sundararaj, K.; Atkinson, C.; Nadig, S.N. T-cell Immunometabolism: Therapeutic Implications in Organ Transplantation. Transplantation 2021, 105, e191–e201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazmi, S.; Khan, M.A.; Shamma, T.; Altuhami, A.; Assiri, A.M.; Broering, D.C. Therapeutic nexus of T cell immunometabolism in improving transplantation immunotherapy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 106, 108621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, I. Methadone--curse or cure? Medical times 1972; 100: 95-96 passim.

- Lucas-Ruiz, F.; Peñín-Franch, A.; Pons, J.A.; Ramírez, P.; Pelegrín, P.; Cuevas, S.; Baroja-Mazo, A. Emerging Role of NLRP3 Inflammasome and Pyroptosis in Liver Transplantation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Pan, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wan, J.; Jiang, H. Microglia-Mediated Neuroinflammation: A Potential Target for the Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, ume 15, 3083–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Liu, B.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Li, F. NLRP3 inflammasome: A potential therapeutic target to minimize renal ischemia/reperfusion injury during transplantation. Transpl. Immunol. 2022, 75, 101718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Lei Z, Chai H, et al. Salidroside alleviates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury during liver transplant in rat through regulating TLR-4/NF-kappaB/NLRP3 inflammatory pathway. Scientific reports 2022; 12: 13973.

- Hecking, M.; Kainz, A.; Werzowa, J.; Haidinger, M.; Döller, D.; Tura, A.; Karaboyas, A.; Hörl, W.H.; Wolzt, M.; Sharif, A.; et al. Glucose Metabolism After Renal Transplantation. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 2763–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.J.; Marks, S.D. Management of chronic renal allograft dysfunction and when to re-transplant. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2018, 34, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafar M, Sahraei Z, Salamzadeh J, et al. Oxidative stress in kidney transplantation: causes, consequences, and potential treatment. Iranian journal of kidney diseases 2011; 5: 357-372.

- la Cruz, E.N.D.-D.; Cerrillos-Gutiérrez, J.I.; García-Sánchez, A.; Andrade-Sierra, J.; Cardona-Muñoz, E.G.; Rojas-Campos, E.; González-Espinoza, E.; Miranda-Díaz, A.G. The Alteration of Pro-inflammatory Cytokines and Oxidative Stress Markers at Six-Month Post-living Kidney Donation. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagdade, J.; Casaretto, A.; Albers, J. Effects of chronic uremia, hemodialysis, and renal transplantation on plasma lipids and lipoproteins in man. . 1976, 87, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pandya, V.; Rao, A.; Chaudhary, K. Lipid abnormalities in kidney disease and management strategies. World journal of nephrology 2015; 4: 83-91.

- Barn, K.; Laftavi, M.; Pierce, D.; Ying, C.; Boden, W.E.; Pankewycz, O. Low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: an independent risk factor for late adverse cardiovascular events in renal transplant recipients. Transpl. Int. 2010, 23, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowe, B.; Xie, Y.; Xian, H.; Balasubramanian, S.; Al-Aly, Z. Low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol increase the risk of incident kidney disease and its progression. Kidney Int. 2016, 89, 886–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, A.K.; Zhu, X. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: Metabolic Regulation and Contribution to Inflammaging. Cells 2020, 9, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.J.; Fraser, I.D.; Bryant, C.E. Lipid regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activity through organelle stress. Trends Immunol. 2021, 42, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Østergaard, J.A.; Jha, J.C.; Sharma, A.; Dai, A.; Choi, J.S.; de Haan, J.B.; Cooper, M.E.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K. Adverse renal effects of NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition by MCC950 in an interventional model of diabetic kidney disease. Clin. Sci. 2022, 136, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, X.; Li, L.; Ma, T.; Shi, M.; Yang, Y.; Fan, Q. A small molecule inhibitor MCC950 ameliorates kidney injury in diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obesity: Targets Ther. 2019; 12, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Niu, B.; Yin, D.; Feng, F.; Gu, S.; An, Q.; Xu, J.; An, N.; Zhang, J.; et al. NLRP3 inflammasome of renal tubular epithelial cells induces kidney injury in acute hemolytic transfusion reactions. Clin. Transl. Med. 2021, 11, e373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiaravalli M, Rowe I, Mannella V, et al. 2-Deoxy-d-Glucose Ameliorates PKD Progression. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 2016; 27: 1958-1969.

- Magistroni, R.; Boletta, A. Defective glycolysis and the use of 2-deoxy-d-glucose in polycystic kidney disease: from animal models to humans. J. Nephrol. 2017, 30, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanevičiūtė, J.; Juknevičienė, M.; Palubinskienė, J.; Balnytė, I.; Valančiūtė, A.; Vosyliūtė, R.; Sužiedėlis, K.; Lesauskaitė, V.; Stakišaitis, D. Sodium Dichloroacetate Pharmacological Effect as Related to Na–K–2Cl Cotransporter Inhibition in Rats. Dose-Response 2018, 16, 1559325818811522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattone VH, 2nd, Bacallao RL. Dichloroacetate treatment accelerates the development of pathology in rodent autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. American journal of physiology Renal physiology 2014; 307: F1144-1148.

- Pernicova, I.; Korbonits, M. Metformin—mode of action and clinical implications for diabetes and cancer. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, T.B.; Walz, G.; Kuehn, E.W. mTOR and rapamycin in the kidney: signaling and therapeutic implications beyond immunosuppression. Kidney Int. 2011, 79, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).