Submitted:

04 May 2023

Posted:

04 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

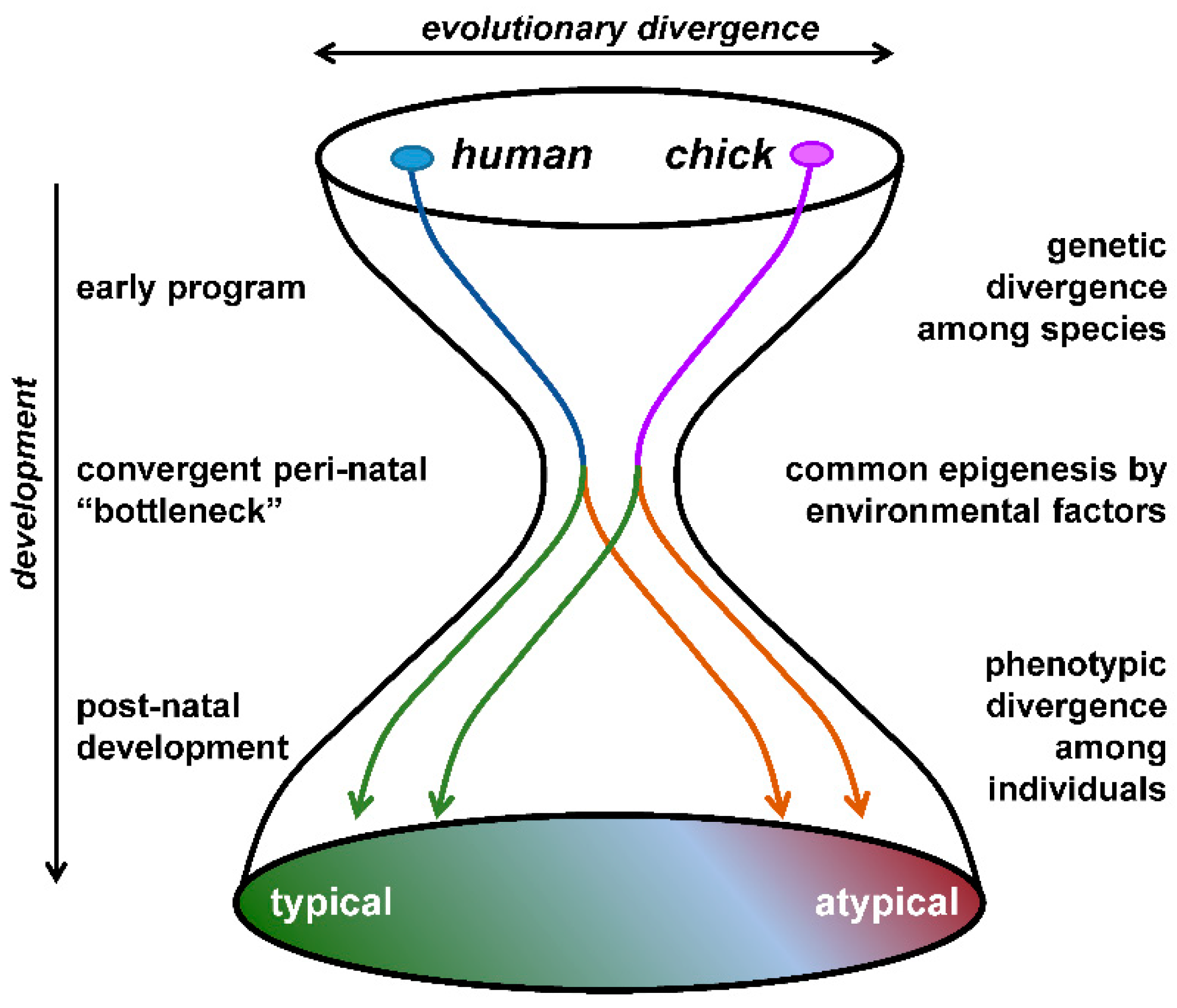

1. In search of valid animal models of developmental psychiatric disorders

2. Diverse environmental risk factors of ASD remain to be specified

3. Visual predispositions canalize the development of social behaviors: common developmental features for the surface validity.

4. Imprinting and the early process of attachment formation

5. VPA, an anticonvulsant drug, mediates ASD-like impairment of social behavior development and acute suppression of spontaneous fetal movements

6. Selective impairment of BM predisposition via fetal interference with nAChR receptors, including neonicotinoid insecticides

7. Thyroid hormone, E-I imbalance in humans and chicks

8. GABA switch, nicotinic transmission, and treatment using bumetanide and oxytocin

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grillner, S.; Robertson, B. The basal ganglia over 500 million years. Curr Biol, 2016, 26, R1088–R1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryanarayana, S.M.; Pérez-Fernández, J.; Brita Robertson, B.; Grillner, S. The lamprey forebrain – evolutionary implications. Brain Behav Evol. 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryanarayana, S.M.; Brita Robertson, B.; Grillner, S. The neural bases of vertebrate motor behaviour through the lens of evolution. Philos Trans B, 2021, 377, 20200521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, G.M.; Grillner, S. Handbook of brain microcircuit. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2018.

- Güntürkün, O.; Bugnyar, T. Cognition without cortex. Trend Cog Sci, 2016, 20, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateson, P.; Gluckman, P. Plasticity, robustness, development and evolution. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Csillag, A.; Ádám A, Zacher G. Avian models for mechanisms underlying altered social behavior in autism. Avian models for mechanisms underlying altered social behavior in autism. Frontiers Physiol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Cheng, H.-W. Perspective: chicken models for studying the ontogenetic origin of neuropsychiatric disorders. Biomedicines, 2022, 10, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, P. The validity of animal models of depression. Psychopharmacol, 1984, 83, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, L.; Gould, J. Severe impairments of social interaction and associated abnormalities in children: epidemiology and classification. J Autism Develop Disord, 1979, 9, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

- Tchaconas, A.; Adesman, A. Autism spectrum disorders: a pediatric overview. Curr Opin Pediatr, 2013, 25, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandin, S.; Lichtenstein, P.; Kuja-Halkola, R.; Larsson, H.; Hultman, C.M.; Reichenberg, A. The familial risk of autism. JAMA, 2014, 311, 1770–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iossifov, I.; O'Roak, B.J.; Sanders, S.J.; et al. The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature, 2014, 515, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaugler, T.; Klei, L.; Sanders, S.J. Most genetic risk for autism resides with common variation. Nature Genetics, 2014, 46, 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossignol, D.A.; Frye, R.E. Environmental toxicants and autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Transl Psychiatry. 2014, 4, e360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallmayer, J.; Cleveland, S.; Torres, A.; et al. Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Ach Gen Psychiatry, 2011, 68, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meador, K.J.; Loring, D.W. Risks of in utero exposure to valproate. JAMA, 2013, 309, 1730–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergaz Z, Weinstein-Fudim L. ; Ornoy A. Genetic and non-genetic animal models for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Reprod Toxicol, 2016, 64, 116–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabunga, D.F.N.; Gonzales, E.L.T.; Kim, J.-W.; Kim, K.C.; Shin, C.Y. Exploring the validity of valproic acid animal model of autism. Exp Neurobiol, 2015, 24, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaliha, D.; Albrecht, M.; Vaccarezza, M.; Takechi, R.; Lam, V.; Al-Salami, H.; Mamo, J. A systematic review of the valproic acid-induced rodent model of autism. Develop Neurosci, 2020, 42, 12–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallortigara, G. Core knowledge of object, number, and geometry: a comparative and neural approach. Cog Neuropsychol, 2012, 29, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Salva, O.; Farroni, T.; Regolin, L.; Vallortigara, G.; Johnson, M.H. The evolution of social orienting: evidence from chicks (Gallus gallus) and human newborns. Plos One, 2011, 6, e18802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Salva, O.; Mayer, U.; Vallortigara, G. Roots of a social brain: developmental models of emerging animacy-detecting mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2015, 50, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versace, E.; Martinho-Truswell, A.; Kacelnik, A.; Vallortigara, G. Priors in animal and artificial intelligence: where does learning begin? Trends Cog Sci. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Uesaka, M.; Kuratani, S.; Irie, N. The developmental hourglass model and recapitulation: an attempt to integrate the two models. J Exp Zool B (Mol Dev Evol), 2020, 338, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, J.; Johnson, M.H. CONSPEC and CONLERN: a two-process theory of infant face recognition. Psychol Rev, 1991, 98, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spelke, E.S.; Kinzler, K.D. Core knowledge. Develop Sci, 2007, 10, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzi, E.; Vallortigara, G. Evolutionary and Neural Bases of the Sense of Animacy. In: The Cambridge Handbook of Animal Cognition (Eds. Allison Kaufman, Josep Call, James Kaufman), 2021. pp. 295-321, Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Vallortigara, G. Born Knowing. Imprinting and the Origins of Knowledge. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England, 2021.

- Versace, E.; Vallortigara, G. Origins of knowledge: Insights from precocial species. Frontiers Behav Neurosci, 2015, 9, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giorgio, E.; Loveland, J.L.; Mayer, U.; Rosa-Salva, O.; Versace, E.; Vallortigara, G. Filial responses as predisposed and learned preferences: Early attachment in chicks and babies. Behav Brain Res. 2017, 325, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa-Salva, O.; Mayer, U.; Versace, E.; Hebert, M.; Lemaire, B.S.; Vallortigara, G. Sensitive periods for social development: Interactions between predisposed and learned mechanisms. Cognition. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, B.; Vallortigara, G. Life is in motion (through a chick's eye). Animal Cog. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.H. Imprinting and development of face recognition: from chick to man. Curr Direct Psychol Sci, 1992, 1, 52–55 https://wwwjstororg/stable/20182129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.H. Subcortical face processing. Nature Rev Neurosci, 2005, 6, 766–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlova, M.A.; Guerreschi, M.; Tagliavento, L.; Gitti, F.; Sokolov, A.N.; Fallgatter, A.J.; Fazzi, E. Social cognition in autism: face tuning. Sci Rep, 2017, 7, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauer, D.; Barrera, M. Infant's perception of natural and distorted arrangemetns of a schematic face. Child Development, 1981, 52, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondloch, C.J.; Lewis, T.L.; Budreau, D.R. Face perception during early infancy. Psychol Sci, 1999, 10, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsabbagh, M.; Johnson, M.H. Trends Cog Sci, 2009, 14, 81-87. [CrossRef]

- Buiatti, M.; Di Giorgio, E.; Piazza, M.; Polloni, C.; Menna, G.; Taddei, F.; Baldo, E.; Vallortigara, G. Cortical route for face like pattern processing in human newborns. PNAS. 2019, 116, 4625–4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inagaki M, Inoue KI, Tanabe S, Kimura K, Takada M, Fujita I. Rapid processing of threatening faces in the amygdala of non-human primates: subcortical inputs and dual roles. Cerebral Cortex, 2022, 33, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugita, Y. Face perception in monkeys reared with no exposure to faces. PNAS, 2008, 105, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reido, V.M.; Dunn, K.; Young, R.J.; Amu, J.; Donovan, J.; Reissland, N. The human fetus preferentially engages with face-like visual stimuli. Curr Biol, 2017, 27, 1825–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, V.E.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Calder, A.; Keane, J.; Young, A. Acquired theory of mind impairments in individuals with bilateral amygdala lesions. Neuropsychologia, 2003, 41, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gernsbacher, M.A.; Yergeau, M. Empirical failures of the claim that autistic people lack a Theory of Mind. Archiv Scientific Psychol, 2019, 7, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Ring, H.A.; Bullmore, E.T.; Ashwin, C.; Williams, S.C.R. The amygdala theory of autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2000, 24, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsabbagh, M.; Gliga, T.; Pickles, A.; Hudry, K.; Charman, T.; Johnson, M.H.; BASIS Team. The development of face orienting mechanisms in infants at-risk of autism. Behav Brain Res, 2013, 251, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, W.; Klin, A. Attention to eye is present but in decline in 2-6-month-old infants later diagnosed with autism. Nature, 2013, 504, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simion, F.; Di Giorgio, E. Face perception and processing in early infancy: inborn predispositions and developmental changes. Frontiers Psychol, 2015, 6, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giorgio, E.; Frasnelli, E.; Rosa-Salva, O.; Scattoni, M.L.; Puopolo, M.; Tosoni, D.; Simion, F.; Vallortigara, G. Difference in Visual Social Predispositions Between Newborns at Low- and High-risk for Autism. Sci Rep, 2016, 6, 26395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giorgio, E.; Rosa-Salva, O.; Frasnelli, E.; Calcagni, A.; Lunghi, M.; Scattoni, M.L.; Simion, F.; Vallortigara, G. Abnormal visual attention to simple social stimuli in 4-month-old infants at high risk for Autism. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 15785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Salva, O.; Regolin, L.; Vallortigara, G. Faces are special for newly hatched chicks: evidence for inborn domain-specific mechanisms underlying spontaneous preferences for face-like stimuli. Develop Sci, 2010, 13, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Salva, O.; Farroni, T.; Regolin, L.; Vallortigara, G.; Johnson, M.H. The evolution of social orienting: evidence from chicks (Gallus gallus) and human newborns. Plos One, 2011, 6, e18802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Salva, O.; Mayer, U.; Vallortigara, G. Unlearned visual preferences for the head region in domestic chicks. PLoS One, 2019, 14, e0222079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiletta A, Pedrana S, Rosa-Salva O, Sgadò P. Spontaneous visual preference for face-like stimuli is impaired in newly-hatched domestic chicks exposed to valproic acid during embryogenesis. Frontiers Behav Neurosci, 2021, 15, 733140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, U.; Rosa-Salva, O.; Lorenzi, E.; Vallortigara, G. Social predisposition dependent neuronal activity in the intermediate medial mesopallium of domestic chicks (Gallus gallus domesticus). Behav Brain Res, 2016, 310, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, U.; Rosa-Salva, O.; Morbioli, F.; Vallortigara, G. The motion of a living conspecific activates septal and preoptic areas in naive domestic chicks (Gallus gallus). Eur J Neurosci, 2017, 45, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, U.; Rosa-Salva, O.; Loveland, J.L.; Vallortigara, G. Selective response of the nucleus taeniae of the amygdala to a naturalistic social stimulus in visually naive domestic chicks. Sci Rep, 2019, 9, 9849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simion, F.; Regolin, L.; Bulf, H. A predisposition for biological motion in the newborn baby. PNAS, 2008, 105, 809–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlova, M.A. Biological motion processing as a hallmark of social cognition. Cerebral Cortex, 2012, 22, 981–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallortigara, G.; Regolin, L.; Marconato, F. Visually inexperienced chicks exhibit spontaneous preference for biological motion patterns. Plos Biology, 2005, 3, e208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugani, R.; Rosa-Salva, O.; Regolin, L.; Vallortigara, G. Brain asymmetry modulates perception of biological motion in newborn chicks (Gallus gallus). Behav Brain Res, 2015, 290, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troje, N.F.; Westhoff, C. The inversion effect in biological motion perception: evidence for a “life detector”? Curr Biol, 2006, 16, 821–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallortigara, G.; Regolin, L. Gravity bias in the interpretation of biological motion by inexperienced chicks. Curr Biol, 2006, 16, R279–R280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.H.F.; Troje, N.F. Characterizing global and local mechanisms in biological motion perception. J Vision, 2009, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, M.; Saunders, D.R.; Troje, N.F. Allocation of attention to biological motion: local motion dominates global shape. J Vision, 2011, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardi, L.; Regolin, L.; Simion, F. Biological motion preference in humans at birth: role of dynamic and configural properties. Develop Sci, 2011, 14, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidet-Ildei, C.; Kitromilides, E.; Orliaguet, J.-P.; Pavlova, M.; Gentaz, E. Preference for point-light biological motion in newborns: contribution of translational displacement. Develop Psychol, 2014, 50, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, M.; Senju, A. The two-process theory of biological motion processing. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2020, 111, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, R.; Turner, L.M.; Smoski, M.J.; Pozdol, S.L.; Stone, W.L. Visual recognition of biological motion is impaired in children with autism. Psychiol Sci, 2003, 14, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutherford, M.D.; Pennington, B.F.; Rogers, S.J. The perception of animacy in young children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord, 2006, 36, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, Q.; Liu, D.; Chen, L. Troje N.F.; He S.; Jiang Y. PNAS, 2018, 115, 1937–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliukhovich, D.A.; Manyakov, N.V.; Bangerter, A.; Ness, S.; Skalkin, A.; Boice, M.; Goodwin, M.S.; Dawson, G.; Hendren, R.; Leventhal, B.; Shic, F.; Pandina, G. J Autism Devlop Disord, 2021, 51, 2369-2380. [CrossRef]

- Federici, A.; Parma, V.; Vicovaro, M.; Radassao, L.; Casartelli, L.; Ronconi, L. Anomalous perception of biological motion in autism: a conceptual review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep, 2020, 10, 4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallortigara, G.; Rosa-Salva, O. Toolkits for cognition: From core-knowledge to genes. In Tucci, V. (Ed.) Neurophenome: Cutting-edge Approaches and Technologies in Neurobehavioral Genetics, 2017, 229-245, New York, Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-54071-8.

- Vallortigara, G. 2021. Animacy detection and its role on our attitudes towards other species. In "Human/Animal Relationships in Transformation – Scientific, Moral and Legal Perspectives" (S. Pollo, A. Vitale, eds.), Palgrave.

- Di Giorgio, E.; Lunghi, M.; Simion, F.; Vallortigara, G. Visual cues of motion that trigger animacy perception at birth: the case of self-propulsion. Develop Sci, 2016, 20, e12394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa-Salva, O.; Grassi, M.; Lorenzi, E.; Regolin, L.; Vallortigara, G. Spontaneous preference for visual cues of animacy in naïve domestic chicks: the case of speed changes. Cognition, 2016, 157, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Salva, O.; Hernik, M.; Broseghini, A.; Vallortigara, G. Visually-naïve chicks prefer agents that move as if constrained by a bilateral body-plan. Cognition, 2018, 173, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giorgio, E.; Lunghi, M.; Vallortigara, G.; Simion, F. Newborns’ sensitivity to speed changes as a building block for animacy perception. Sci Rep, 2021, 11, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versace, E.; Fracasso, I.; Baldan, G.; Dalle Zotte, A.; Vallortigara, G. Newborn chicks show inherited variability in early social predispositions for hen-like stimuli. Sci Rep, 2017, 7, 40296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versace, E.; Ragusa, M.; Vallortigara, G. A transient time window for early predispositions in newborn chicks. Sci Rep, 2019, 9, 18767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzi, E.; Mayer, U.; Rosa-Salva, O.; Vallortigara, G. Dynamic features of animate motion activate septal and preoptic areas in visually naïve chicks (Gallus gallus). Neuroscience, 2017, 354, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaire, B.; Rosa-Salva, O.; Fraja, M.; Lorenzi, E.; Vallortigara, G. Spontaneous preference for unpredictability in the temporal contingencies between agents’ motion in naïve domestic chicks. Proc Royal Soc B, 2022, 289, 20221622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Salva, O.; Hernik, M.; Fabbroni, M.; Lorenzi, E.; Vallortigara, G. Naïve chicks do not prefer objects with stable body orientation, though they may prefer behavioural variability. Animal Cog. 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, M.; Versace, E.; Vallortigara, G. Inexperienced preys know when to flee or to freeze in front of a threat. PNAS, 2019, 116, 22918–22920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, D. Instinct with original observations on young animals. Macmillan’s Mag 1873, 27, 282–293 (Reprinted in British Journal of Animal Behaviour 2:2. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, K. The companion in the bird’s world. Auk, 1937, 54, 245–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, G. Pathway of the past: the imprint of memory. Nature Rev Neurosci, 2004, 5, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolhuis, J.J.; Johnson, M.H.; Horn, G. Effects of early experience on the development of filial preferences in the domestic chick. Dev Psychobiol, 1985, 18, 299–308 https ://doiorg/101002/dev420180403". [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.H.; Bolhuis, J.J.; Horn, G. Interaction between acquired preferences and developing predispositions during imprinting. Animal Behav, 1985, 33, 1000–1006 https ://doiorg/101016/S0003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.H.; Horn, G. Development of filial preferences in dark-reared chicks. Animal Behav, 1988, 36, 675–683 https ://doiorg/101016/S0003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, M.; Matsushima, T. Preference for biological motion in domestic chicks: sex-dependent effect of early visual experience. Animal Cog, 2012, 15, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, M.; Matsushima, T. Biological motion facilitates imprinting. Animal Behav, 2016, 116, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Aoki, N.; Kitajima, T.; Iikubo, E.; Katagiri, S.; Matsushima, T.; Homma, K.J. Thyroid hormone determines the start of the sensitive period of imprinting and primes later learning. Nature Comm, 2012, 3, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, M.; Aoki, N.; Yamaguchi, S.; Homma, K.-J.; Matsushima, T. Thyroid hormone sensitizes the imprinting-associated induction of biological motion preference in domestic chicks. Frontiers Physiol, 2018, 9, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemura, Y.; Yamaguchi, S.; Aoki, N.; Miura, M.; Homma, K.-J.; Matsushima, T. Gene expression of Dio2 (thyroid hormone converting enzyme) in telencephalon is linked with predisposed biological motion preference in domestic chicks. Behav Brain Res, 2018, 349, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, E.; MLemaire, B.S.; Versace, E.; Matsushima, T.; Vallortigara, G. Resurgence of an inborn attraction for animate objects via thyroid hormone T3. Frontiers Behav Neurosci. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Miura, M.; Nishi, D.; Matsushima, T. Combined predisposed preferences for colour and biological motion make robust development of social attachment through imprinting. Animal Cog, 2020, 23, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.J.; Turnpenny, P.; Quinn, A.; Glover, S.; Lloyd, D.J. Montogomery T.; Dean J.C.S. A clinical study of 57 children with fetal anticonvulsant syndrome. J Med Genet, 2000, 37, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasalam, A.D.; Hailey, H.; Moore, S.J.; Turnpenny, P.D.; Lloyd, D.J.; Dean, J.C.S. Characteristics of fetal anticonvulsant syndrome associated autistic disorder. Develop Med Child Neurol, 2005, 47, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.; Grønborg, T.K.; Sørensen, M.J.; Schendel, D.; Parner, E.T.; Pedersen, L.H. Vestergaard M. Prenatal valproate exposure and risk of autism spectrum disorders and childhood autism. JAMA, 2013, 309, 1696–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, C.; Fahnestock, M. The valproic acid-induced rodent model of autism. Exp Neurol, 2018, 299, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishigori, H.; Kagami, K.; Takahashi, A.; Tezuka, Y.; Sanbe, A.; Nishigori, H. Impaired social behavior in chicks exposed to sodium valproate during the last week of embryogenesis. Psychopharmacol, 2013, 227, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgadò, P.; Rosa-Salva, O.; Versace, E.; Vallortigara, G. Embryonic exposure to valproic acid impairs social predispositions of newly-hatched chicks. Sci Rep, 2018, 8, 5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, E.; Pross, A.; Rosa-Salva, O.; Versace, E.; Sgadò, P.; Vallortigara, G. Embryonic exposure to valproic acid affects social predispositions for dynamic cues of animate motion in newly-hatched chicks. Frontiers Physiol, 2019, 10, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiletta, A.; Pedrana, S.; Rosa-Salva, O.; Sgadò, P. Spontaneous visual preference for face-like stimuli is impaired in newly-hatched domestic chicks exposed to valproic acid during embryogenesis. Frontiers Behav Neurosci, 2021, 15, 733140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushima, T.; Miura, M.; Patzke, N.; Toji, N.; Wada, K.; Ogura, Y.; Homma, K.J. Sgadò P., Vallortigara G. Fetal blockade of nicotinic acetylcholine transmission causes autism-like impairment of biological motion preference in the neonatal chick. Cereb Cortex Comm. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gean, P.-W.; Huang, C.-C.; Hung, C.-R.; Tsai, J.-J. Valproic acid suppresses the synaptic response mediated by the NMDA receptors in rat amygdalar slices. Brain Res Bull, 1994, 33, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterer, G. Valproate and GABAergic system effects. Neuropsychopharmacol, 2003, 28, 2050–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phiel, C.J.; Zhang, F.; Huang, E.Y.; Guenther, M.G.; Lazar, M.A.; Klein, P.S. Histone deacetylase is a direct target of valproic acid, a potent anticonvulsant, mood stabilizer, and teratogen. J Biol Chem, 2001, 28, 36734–36741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekoff, A.; Stein, P.S.G.; Hamburger, V. Coordinated motor output in the hindlimb of the 7-day chick embryo. PNAS, 1975, 72, 1245–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekoff, A. Spontaneous embryonic motility: an enduring legacy. Internat J Develop Neurosci, 2001, 19, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenship, A.G.; Feller, M.B. Mechanisms underlying spontaneous patterned activity in developing neural circuits. Nature Rev Neurosci, 2010, 11, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, T.; Kulangara, K.; Antoniello, K.; Markram, H. Elevated NMDA receptor levels and enhanced post-synaptic long-term potentiation induced by prenatal exposure to valproic acid. PNAS, 2007, 104, 13501–13506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunova, G.; Pallanti, S.; Hollander, E. Excitatory/inhibitory imbalance in autism spectrum disorders: implications for interventions and therapeutics. World J Biol Psychiatry, 2016, 17, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Lee, J.; Kim, E. Excitation/inhibition imbalance in animal models of autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry, 2017, 81, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Kim, E. Suppression of NMDA receptor function in mice prenatally exposed to valproic acid improves social deficits and repetitive behaviors. Frontiers Mol Neurosci. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Costas-Ferreira, C.; Faro, L.R.F. Neurotoxic effects of neonicotinoids on mammals: what is there beyond the activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors? - a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci, 2021, 22, 8413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, C.A.; Foppen, R.P.B.; van Turnhaut, C.A.M.; de Kroon, H.; Jongejans, E. Declines in insectivorous birds are associated with high neonicotinoid concentration. Nature, 2014, 511, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, M.L.; Stutchbury, B.J.M.; Morrissey, C.A. Imidacloprid and chlorypyrifos insecticides impair migratory ability in a seed-eating songbird. Sci Rep, 2017, 7, 15176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, M.L.; Stutchbury, B.J.M.; Morrissey, C.A. A neonicotinoid insecticide reduces fueling and delays migration in songbirds. Science, 2019, 365, 1177–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, A.P.; Daniels, J.L.; Hertz-Picciotto, I. Autism spectrum disorder, flea and tick medication, and adjustments for exposure misclassification: the CHARGE (Childhood Autism Risks from Genetics and Envinronment) case-control study. Environ Health, 2014, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunier, R.B.; Bradman, A.; Harley, K.G.; Kogut, K.; Eskenazi, B. Prenatal residential proximity to agricultural pesticide use and IQ in 7-year-old children. Environ Health Perspect. 2017. [CrossRef]

- von Ehrenstein, O.S.; Ling, C.; Cui, X.; Cockburn, M.; Park, A.S.; Yu, F.; Wu, J.; Ritz, B. Prenatal and infant exposure to ambient pesticides and autism spectrum disorder in children: population based case-control study. the BMJ, 2019, 364, l962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongono, J.S.; Béranger, R.; Baghdadli, A.; Mortamais, M. Pesticides used in Europe and autism spectrum disorder risk: can novel exposure hypotheses be formulated beyond organophosphates, organochlorines, organochlorines, pyrethroids and carbamates? – A systematic review. Environ Res, 2020, 187, 209646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, K.; Isobe, T.; Yang, J.; Win-Shwe, T.; Yoshikane, M.; Nakayama, S.F.; Kawashima, T.; Suzuki, G.; Hashimoto, S.; Nohara, K.; Tohyama, C.; Maekawa, F. In utero and lactational exposure to acetamiprid induces abnormalities in socio-sexual and anxiety-related behaviors of male mice. Frontiers Neurosci, 2016, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román, G.C.; Ghassabian, A.; Bongers-Schokking, J.J.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Hofman, A.; de Rijke, Y.B.; Verhulst, F.C.; Tiemeier, H. Association of gestational maternal hypothyroxinemia and increased autism risk. Annals Neurol, 2013, 74, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berbel, P.; Navarro, D.; Román, G.C. An evo-devo approach to thyroid hormones in cerebral and cerebellar cortical development: etiological implications for autism. Frontiers Endocrinol. 2014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getahun, D.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Fassett, M.J.; Wing, D.A.; Xiang, A.H.; Chiu, V.Y.; Peltier, M.R. 2018. Association between maternal hypothyroidism and autism spectrum disorders in children. Pediatrics Res. [CrossRef]

- Hoshiko, S.; Grether, J.K.; Windham, G.C.; Smith, D.; Fessel, K. Are thyroid hormone concentrations at birth associated with subsequent autism diagnosis? Autism Res, 2011, 4, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, J.L.; Windham, G.C.; Lyall, K.; Pearl, M.; Kharrazi, M.; Yoshida, C.K.; de Water, J.V.; Croen, L.A. Neonatal thyroid stimulating hormone and subsequent diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability. Autism Res, 2020, 13, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, G.; Hensch, T.K. Critical period regulation by thyroid hormones: potential mechanisms and sex-specific aspects. Frontiers Mol Neurosci. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Westerholz, S.; de Lima, A.D.; Voigt, T. 2013. Thyroid hormone-dependent development of early cortical networks: temporal specificity and the contribution of trkB and mTOR pathways. Frontiers Cell Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Batista, G.; Johnson, J.L.; Dominguez, E.; Costa-Mattioli, M.; Pena, J.L. Regulation of filial imprinting and structural plasticity by mTORC1 in newborn chickens. Sci Rep, 2018, 8, 8044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, E.; Lemaire, B.S.; Versace, E.; Matsushima, T.; Vallortigara, G. Resurgence of an inborn attraction for animate objects via thyroid hormone T3. Frontiers Behav Neurosci. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Saheki, Y.; Aoki, N.; Homma, K.J.; Matsushima, T. Suppressive modulation of the chick forebrain network for imprinting by thyroid hormone: an in vitro study. Frontiers Physiol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Kasai, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Takamatsu, Y.; Hino, O.; Ikeda, K.; Mizuguchi, M. Rapamycin reverses impaired social interaction in mouse models of tuberous sclerosis complex. Nature Comm, 2012, 3, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagani, M.; Barsotti, N.; Bertero, A.; Trakoshis, S.; Ulysse, L. Locarno A. et al. Nature Comm, 2021, 12, 6084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Ari, Y. Excitatory actions of GABA during development: the nature of the nurture. Nature Rev Neurosci, 2002, 3, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Represa, A.; Ben-Ari, Y. Tropic actions of GABA on neuronal development. Trends Neurosci, 2005, 28, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Ari, Y.; Gaiarsa, J.L.; Tyzio, R.; Khazipov, R. GABA: A pioneer transmitter that excites immature neurons and generates primitive oscillations. Physiol Rev, 2007, 87, 1215–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, C.K.; Stein, V.; Keating, D.J.; Maier, H.; Rinke I, Rudhard Y. et al. NKCC1-dependent GABAergic excitation drives synaptic network maturation during early hippocampal development. J Neurosci, 2009, 29, 3419–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, T.M.; Lipska, B.K.; Ali, T.; Mathew, S.V.; Law, A.J.; Metitiri, O.E. Expression of GABA signaling molecules KCC2, NKCC1, and GAD1 in cortical development and schizophrenia. J Neurosci, 2011, 31, 11088–11095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Neff, R.A.; Berg, D.K. Sequential interplay of nicotinic and GABAergic signaling guides neuronal development. Science, 2006, 314, 1610–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahle, K.T.; Deeb, T.Z.; Puskarjov, M.; Silayeva, L.; Liang, B.; Kaila, K.; Moss, S.J. Modulation of neuronal activity by phosphorylation of the K-Cl cotransporter KCC2. Trends Neurosci, 2013, 36, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaila, K.; Price, T.J.; Payne, J.A.; Puskarjov, M.; Voipio, J. Cation-chloride cotransporters in neuronal development, plasticity and disease. Nature Rev Neurosci, 2014, 15, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Friedel, P.; Zhu, W. The structural basis of function and regulation of neuronal cotransporters NKCC1 and KCC2. Comm Biol, 2021, 4, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrosu, F.; Marrosu, G.; Rachel, M.G.; Biggio, G. Paradoxical reactions elicited by diazepam in children with classical autism. Funct Neurol, 1987, 2, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nelson, S.B.; Valakh, V. Excitatory/inhibitory balance and circuit homeostasis in autism spectrum disorders. Neuron, 2015, 87, 684–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpire, E.; Ben-Ari, Y. A wholistic view of how bumetanide attenuates autism spectrum disorders. Cells, 2022, 11, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjikhani, N.; Johnels, J.Å.; Lassalle, A.; Zürcher, N.R.; Hippolyte, L.; Gillberg, C.; Lemonnier, E.; Ben-Ari, Y. Bumetanide for autism: more eye contact, less amygdala activation. Sci Rep, 2018, 8, 3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernell, E.; Gustafsson, P.; Gillberg, C. Bumetanide for autism: open-label trial in six children. Acta Paediatrica, 2021, 110, 1548–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Shan, L.; Miao, C.; Zhida, X.; Jia, F. Treatment effect of bumetanide in children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers Psychiat. 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprengers, J.J.; van Andel, D.M.; Zuithoff, N.P.A.; Keijzer-Veen, M.G.; Schulp, A.J.A.; Scheepers, F.E.; Lilien, M.R.; Oranje, B.; Bruining, H. Bumetanide for core symptoms of autism spectrum disorder (BAMBI): a single center, double-blinded, participant-randomized, placebo-controlled, phase-2 superiority trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2021, 60, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Andel, D.M.; Sprengers, J.J.; Königs, M.; de Jonge, M.V.; Bruining, H. Effects of bumetanide on neurocognitive functioning in children with autism spectrum disorder: secondary analysis of a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Autism Develop Disord. 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kéri, S.; Benedek, G. Oxytocin enhances the perception of biological motion in humans. Cog Affect Behav Neurosci, 2009, 9, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K.J.; Oztan, O.; Libove, R.A.; Harden, A.Y. Intranasal oxytocin treatment for social deficits and biomarkers of response in children with autism. PNAS. 114, 8119-8124. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.M.; Palumbo, M.C.; Lawrence, R.H.; Smith, A.L.; Goodman, M.M.; Bales, K.L. Effect of age and autsm spectrum disorder on oxytocin receptor density in the human basal forebrain and midbrain. Transl Psychiat, 2018, 8, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, M.; Mitsui, S.; En, S.; Ohtani, N.; Ohta, M.; Sakuma, Y.; Onaka, T.; Mogi, K.; Kikusui, T. Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human-dog bonds. Science, 2015, 348, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, K.; Kis, A.; Kanizsár, O.; Hernádi, A.; Gácsi, M.; Topál, J. The effect of oxytocin on biological motion perception in dogs (Canis familiaris). Anim Cog, 2016, 19, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, J.F.; Leichner, W.; Ahmann, H.; Stevens, J.R. Mesotocin influences pinyon jay prosociality. Biol Lett, 2018, 14, 20180105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguchi, A.; Mogi, K.; Izawa, E.-I. Measurement of urinary mesotocin in large-billed crows by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Vet Med Sci, 2022, 84, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loveland, J.; Stewart, M.; Vallortigara, G. Effects of oxytocin-family peptides and substance P on locomotor activity and filial preferences in visually naïve chicks. Eur J Neurosci, 2019, 50, 3674–3687 https ://doiorg/101111/ejn14520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, A.R.; Carreira, L. Anbalagan S.; Blechman J.; Levkowitz G.; Oliveira R.F. Perceptual mechanisms of social affiliation in zebrafish. Sci Rep, 2020, 10, 3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.; Peterson, R.T. The zebrafish subcortical social brain as a model for studying social behavior disorders. Disease Models Mechanisms, 2019, 12, dmm039446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonzino, M.; Busnelli, M.; Antonucci, F.; Verderio, C.; Mazzanti, M.; Chini, B. The timing of the excitatory-to-inhibitory GABA switch is regulated by the oxytocin receptor via KCC2. Cell Reports, 2016, 15, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörnberg, H.; Pérez-Garci, E.; Schreiner, D.; Hatstatt-Burklé, L.; Magara, F.; Baudouin, S.; Matter, A.; Nacro, K.; Pecho-Vrieseling, E.; Scheiffele, P. Rescue of oxytocin response and social behaviour in a mouse model of autism. Nature, 2020, 584, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).