1. Introduction

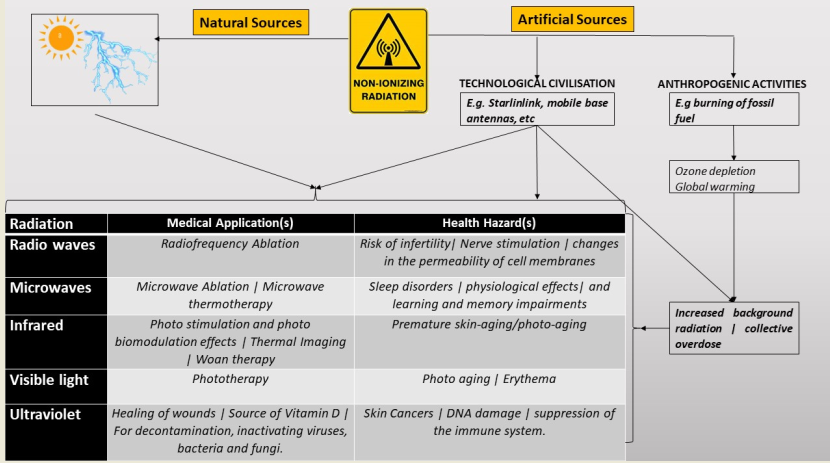

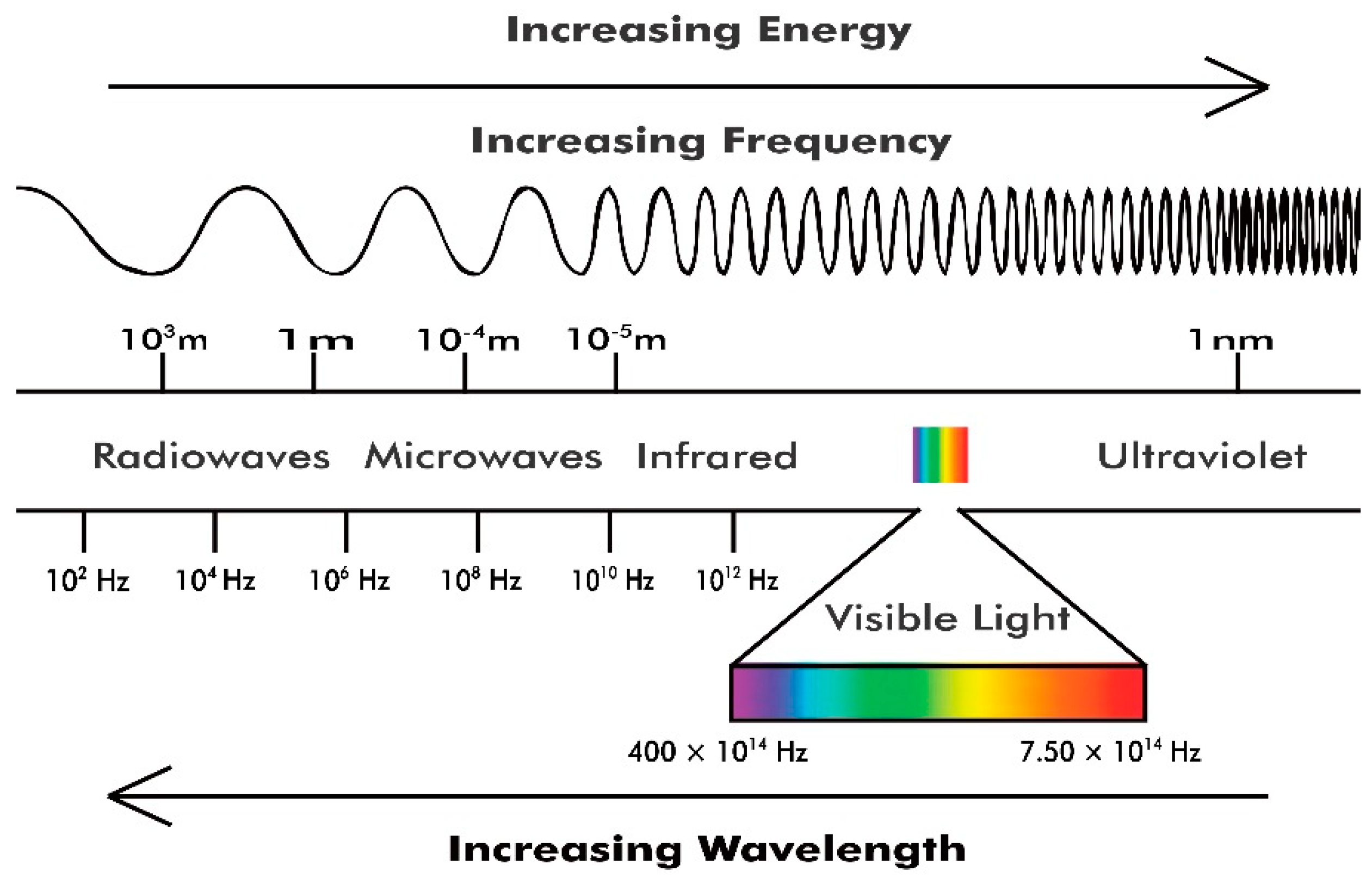

All wireless technology relies on NIR. We interact and now depend on Non-ionizing electromagnetic radiation (NI EMR) for a quantum of applications. NI EMR (

Figure 1) is a part of the electromagnetic spectrum that does not include X-ray and Gamma radiations with frequency and wavelength ranging from 0 – 30 PHz and 1 nm - 10

3 m respectively. It has not enough energy to knock off electrons from an atom (Hanson

et al., 2019). As technological civilization keeps widening through the expansion of digital tools, telecommunication devices and other anthropogenic activities, the sources of Non-Ionizing Radiation (NIR) which keep increasing sporadically would have a tremendous impact on human health whether positively or negatively. The latter would include the thermal and non-thermal effects while the former would include, the recent applications of NIR in solving health-related cases for instance in the diagnosis and treatment of cancers aside from the other aged-long applications in electronics and wireless devices. Lemarchand (2009) describes technological civilization as the technical capability to communicate, generate or produce any kind of technological activities.

Aside from these sources of NIR; mobile devices, radio sets, Bluetooth devices, laptops, televisions, satellite antennas, radiofrequency antennae, power-lines transmission, microwave appliances, and all wireless devices resulting from technological civilization, ozone depletion and global warming – the increase in the earth’s temperature due to anthropogenic activities have also played a significant influence in the increase of background radiation, through the amount of NIR particularly solar UV and infrared radiation reaching the earth’s surface. Solar UV is one of the leading causes of skin cancers and other related health effects (WHO, 2022).

The very fact that the International Commission on Non-Ionising Radiation Protection (ICNIRP) recommends exposure limits and guidelines to protect humans exposed to radiofrequency radiation and other NIR is proof of the global acceptability and acknowledgement of the significant threat to human health NIR poses. This review article aims to highlight the current application of NIR in medicine; the health hazards associated with overexposure to NIR, and the impact of NIR in Nigeria as a developing nation.

We started by looking at the brief history of NIR, their descriptions, and the technological civilization impact of NIR in Nigeria. This study also covers the collective dose of NIR in Nigeria; casualties from NIR with mathematical equations associated with NIR. Finally, we examined the Regulators governing the use of NIR with recommendations.

2. Historical Context of Non-Ionizing Radiation

In the year 1800, physicists beginning with William Herschel expounded light, from the knowledge of the brightness of the day or the rising of the sun but rather as the spectrum of energies called electromagnetic radiation (EMR), (David, 2007). EMR is the transfer of energy in the form of oscillating electric and magnetic fields. The graphical representation indicating the wavelengths, frequency and or energies of ionizing radiation (X-rays and Gamma radiation) and Non-ionizing radiation (Radio waves, Microwaves, Infrared, Visible light, Ultraviolet radiation) is called the electromagnetic spectrum. The discoveries of these Non-ionizing radiations (NIR) started with Herschel’s analysis of the measure of various effects that each colour of the visible light would have on the thermometer – there he discovered that beyond the visible light, at the red colour of the spectrum of light, the thermometer recorded an increased in temperature and he called that light infrared light. He used the glass prism to separate the constituent colours from the sun. Following Herschel’s discoveries, Johann Wilhelm Ritter discovered that there was light beyond the violet end of the spectrum, which has stronger chemical action on silver chloride and he called it Ultraviolet light (Mahmoud et al., 2008; NASA, 2013).

Heinrich Hertz in 1887 demonstrated the existence of wavelength longer than infrared light as predicted in 1867 by James Clerk Maxwell and that led to the discovery of radio waves and a similar experiment led to the discovery of microwaves (David, 2007). The discoveries of NIR brought about the needed acceleration for technological civilization and had a measurable influence on globalization, digitalization and democracy. NIR is composed of oscillating electric and magnetic fields and has less energy than ionizing radiation. It cannot knock off an electron from atoms or molecules but it can excite these atoms or molecules causing them to vibrate faster. Myriad of research has shown that despite its widespread use, they are growing concerns regarding the potential health impacts of NIR exposure, particularly in developing countries such as Nigeria and Africa including cataracts of the eye, thermal injury, altered behavioural patterns, decreased endurance, and radiofrequency burns from touching ungrounded metal objects in a strong electric field (Bernhardt, 1992) etc. However, they are very beneficial when appropriately directed.

Figure 1 represent NI EMR spectrum in different wavelength bands and colour.

3. Descriptions and Applications of Non-Ionizing Radiation

Apart from the wavelengths and frequency differentiating each NIR, another way to categorize NIR is their penetration power which is observed in their applications and health hazards. As seen in

Figure 1.0, the higher the frequency, the shorter the wavelength and the greater the health hazards. Ultraviolet radiation is more hazardous to man compared to the other NIR, however, the attenuation of radiation on material or tissues depends on the duration of the exposure, proximity of the source and the energy imparted. This section examines each NIR, its health applications, and the associated hazard.

RFR is the transfer of energy in the form of electric and magnetic fields by radio waves (ARPANSA, n.d). When a field impacts a material, it interacts with the atoms and molecules in that material, for a biological tissue that is exposed to RFR, the tissue can reflect away the power while some of it is absorbed. The absorbed electric field produces an induced current that could affect the body in different ways (ICNIRP 2020). RFR interactions with biological tissues can be of great benefit as well as threats to healthy living.

For instance, in the area of biological hazards, Otitoloju et al., (2010); Zha et al., (2019) found that long-term exposure to RFR (from cellphones, radar transmitters, Wi-Fi, and proximity to GSM base station) affects the potency of the spermatozoa and the male reproductive organs, that indirectly increase the risk of infertility. An Animal bioassay experiment conducted in Nigeria by Oyewopo et al. (2016) showed that chronic exposure to RFR on cell phones can produce defective testicular function associated with increased oxidative stress and decreased gonadotropic hormonal profile.

In this experiment, it was observed that Rats of 0.2kg and 0.18kg exposed to RFR from cell phones of dual-band EGSM900/1,800 MHz for a duration of 2 hr/day and 3 hrs/days for 28 days showed a significant decrease in sperm count. The increased risks of glioma associated with cell phones led to the classification of RFR as possibly carcinogenic to humans by the WHO/International Agency for Research on Cancer (2011) pending further evidence. However, ICNIRP (2020) holds that nerve stimulation, changes in the permeability of cell membranes and effects due to temperature are the only substantiated adverse health effect caused by RF EMR.

On the other hand, the use of RFR which cuts across every sector is now finding expression in medicine through the treatment of cancers and other chronic health problems using Radiofrequency ablation (RFA). RFA is a technique that uses radio waves to destroy abnormal or dysfunctional tissue (Michaud et al., 2021). The process involves targeting the tumour, with converted thermal energy from radio waves using a thin needle-like probe, through the skin which heats the tumour and then destroys the cancer cells. RFA is used to treat thyroid tumours (Haris et al., 2021), liver tumours (Vanagas et al., 2010; Fang et. al., 2022) chronic headaches, back and leg pain (Abd-Elsayed et. al., 2019), Fibroid (Baxter B., et. al., 2022), esthetic dermatology, skin ageing face and Neck rejuvenation (Gentile et al., 2017; Bonjorno et al., 2020) etc.

Microwave radiation (MR) is absorbed at the molecular level and manifests as changes in the vibrational energy of the molecules or heat (Banik et al., 2003). Just like RFR, there are used in households, industries, food processing, sterilisation, communications, treatments of cancer and microbial infections via ablation therapy, biosensor diagnostics, skin diseases, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory sickness (Banik et al., 2003; Zhi et al., 2017; Gartshore et al., 2021). Microwave ablation is another method of killing growth, tumours or tissue in the body with thermos energy. Instead of incision, ablation uses heat to kill growth. Several health implications like sleep disorders, physiological effects, and learning/memory impairments, have been associated with MR (Banik et al., 2003; Zhi et al., 2017).

All surfaces including living and non-living things that have a temperature above 0 k (- 273.150 Celsius) emit Infrared radiation (IR), and can absorb IR radiation when exposed to it from both natural sources including solar radiation and fire; and artificial sources including heating devices, infrared lamps and infrared saunas (Schieke et al., 2003; ICNIRP, 2013; Craig, 2014). ISO 20473 standard for sub-division classifies IR into three bands: Near-Infrared (NIR, 0.78–3.0 μm), Mid-Infrared (MIR, 3.0–50.0 μm) and Far-Infrared (FIR, 50.0–1000.0 μm). The human body absorbs FIR as radiant energy and emits the same energy at high temperatures. There are several applications to IR in medicine such as fatigue of rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, potentiate photodynamic therapy, and treat ophthalmic, neurological, and psychiatric disorders (Tsai et al., 2017). IR can be detected using night vision goggles or infrared cameras. Infrared radiation is used to reveal objects in the universe that cannot be seen in visible light (NASA, 2010).

Visible light (VL) is the section of EMR visible to the human eye. Humans are exposed to these radiations through sunlight, light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and electronic devices. Studies have shown that VL radiation and IR can penetrate the skin and directly or indirectly lead to various biologic effects such as Photoaging (Mahmoud et al., 2008; Pourang et. al., 2022; Huang & Chien 2020; Sklar et. al., 2012) – a process whereby the skin changes epidermal thickness, simply put premature skin changes due to chronic sun exposure (Huang & Chien 2020); and erythema (Mahmoud et al., 2008; Sklar et. al., 2012; Guan et al., 2021; Pourang et al., 2022).

The primary natural source of UV radiation is the sun – what is referred to as solar UV (Gallagher et al., 2010), while artificial sources of UVR include: applications in medicine, industry, cosmetic and disinfection purposes, optically filtered xenon arc lamps or fluorescent lamps and ozone depletion due to manmade activities (WHO, 2022). The effect of UV radiation varies in their wavelengths, and therefore, it is subdivided into three bands; UVA (315 – 400nm), UVB (280 – 315nm), and UVC (100 – 280nm) (WHO 1994; Diffey, 2002; Gallagher et al., 2010). Among the subdivisions, UVB and UVA are much associated with sunburn and skin cancer, whereas UVB has very negligible adverse effects since it gets filtered by the atmosphere before reaching the earth’s surface. It is worthy of note that UV solar radiation is also associated with vitamin D, which some recent studies according to Gallagher et al. (2010) suggest may potentially reduce the risk of colon, prostate and breast cancers but excessive exposure to it causes sunburn, skin ageing, skin cancer and skin depression (Tertsea et al., 2013). Solar UVR accounts for approximately 93% of skin cancers and about half of lip cancers (Gallagher et al., 2010). Several factors influence the amount of UVR reaching the earth’s surface, including climate change, ozone depletion, Sun elevation, latitude, altitude, and cloud cover (Diffey, 2002; Narayanan et al., 2010; WHO, 2022).

In summary, All NIR have their merits and demerits and all can be applied to solving health challenges. Their advantages come when they are intentionally applied to solving problems (table 1) while overexposure to these radiations can be very detrimental to human health (table 2.0). Anthropogenic activities and technological civilisation are key factors leading to overexposure and increasing background radiation.

Table 1.0 summarise the applications of NIR in medicine.

4. Technological Civilization and the Impact of NIR in Nigeria

Manmade activities directly or indirectly affect ozone depletion leading to the abundance of UV radiations; similarly, technological civilization has increased the number of NIR sources capable of influencing background radiations. The larger the population size, the more sources of NIR are used, most commonly mobile phones. Nigeria, as a developing nation, is popularly called the giant of Africa, it is bounded to the north by Niger, to the south by the Gulf of Guinea of the Atlantic Ocean, to the east by Chad and Cameroon and to the west by Benin as shown in

Figure 2 (Nations Online Project, n.d.). Nigeria is known to be the most populous black nation in the world, with about 219 million people. By the year 2050, it is estimated to become the third most populous country in the world after China and India with a population size of about 377,000 million people (Sasu, 2022). The growing population size of Nigeria has attracted developers, manufacturers and developed nations including China, and America to African markets, particularly Nigeria. The oil boom in the 1970s would have been their usual attraction (Onuoha and Elegbede, 2018).

A study conducted in Nigeria by Aweda

et al., (2009) shows that some mobile phones emit power above ICNIRP recommended value and radiofrequency masts are situated near residential buildings, offices, schools and hospitals thereby increasing exposure levels. As of 2021, Nigeria recorded 195.4 million and 40 million active mobile phone subscribers and smartphone owners respectively according to Nigerian Communication Commission (NCC) with a projection of 140 million smartphone owners by 2025 (Taylor, 2023). In January 2023, Space X announced the launch of Starlink in Nigeria which is the first in Africa. Starlink uses high-frequency NI EMR in the transmission of data from Starlink satellites to dishy MCFlatface (

Figure 3) and vice versa making it possible to stream HD videos, online gaming, or other high-data-rate activities simultaneously. Starlink uses millions of interconnected satellites, much closer to the earth, (orbiting at 550km) to provide high-speed, low-latency broadband internet across the globe (starlink.com). There is currently no research carried out to ascertain Starlink’s effect on biological tissues.

No doubt, the influx of all these high-tech and other sources emitting NIR has developed Nigeria tremendously. One could imagine a country or continent without access to information, communication, or seamless transmission of data. For example, in 2022, as a step to deepen democracy and curb rigging of elections and snatching of election materials including ballot boxes, the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) introduced the use of Bimodal Voter Accreditation System (BVAS) machines, which paved the way for electronic transmission of results in electioneering. Starlink communication and the development of 5G will increase the speed of transmission and curb network challenges attributed to BVAS machines and electronic transmission of results if deployed.

Despite the continuous use of NIR in other sectors, one major setback in Nigeria and most African nations are in the application of NIR in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases or illnesses. It is observed that Radiofrequency ablation and microwave ablation are not well-known applications in most Nigerian and African health facilities possible reasons could be that the operations are recently developed; inadequacy of funds and infrastructure; and limited personnel with knowledge of ablations physics and clinical applications. Current research in radiation physics is being tailored to this area to uncover its other applications, benefits and effects. Some people opt for NIR treatment for most adverse health effects, including cancer, turmoil and other growths in the body instead of an incision.

Those applications of NIR found in Nigeria and sub-Saharan African health facilities such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MIR), a non-invasive imaging technique that uses radio waves and magnetic fields to diagnose and produce highly detailed pictures of the internal structure of the body and Phototherapy, use to treat a plethora of dermatology related illnesses are reported to be relatively low to the population size (Ademola, 2003; Ogbole et al. 2013).

5. Health Impact Assessments of Non-Ionizing Radiations

Although the benefits of NIR are quite fascinating, it can also be cataclysmic and detrimental to the body (table 2.0) if not regulated and carefully administered to their limits. In this section, we provided an overview of the various types of health hazards associated with NIR exposure, including thermal and non-thermal effects. We also discussed the collective dose of NIR in Nigeria and Africa and its impacts on human populations. Through the examination of practical examples, we assessed the magnitude of casualties and the need for mitigation measures to reduce the health impacts of NIR exposure to biological systems. By highlighting the health risks of NIR, this section aims to provide a comprehensive overview of this important public health issue and to inform policymakers, public health practitioners and the general public.Top of FormBottom of Form

5.1. Types of health hazards from NIR

The health hazards associated with non-ionizing radiation can be broadly categorized into two groups: thermal effects and non-thermal effects.

The thermal effects of NIR occur when exposure to it increases body temperature, leading to a thermal injury (Ng, 2003). Examples of thermal effects include burns and cataracts, which can occur as a result of exposure to high levels of microwave radiation, such as from industrial microwave equipment (Zamanian and Hardiman, 2005).

The non-thermal effects of NIR are not directly caused by an increase in temperature, but rather by the biological interactions of non-ionizing radiation with the human body (Omer, 2021). Examples of non-thermal effects include DNA damage, genetic mutations, and neurological effects, which can occur as a result of exposure to low-frequency electromagnetic field(s) generated by electrical appliances and devices, such as power lines and cell phones (Hardell and Sage, 2008).

It is worthwhile to note that the evidence for the health effects of non-thermal exposure is still not clear, therefore we recommend further research is needed to fully understand the potential risks associated with these effects.

6. Collective dose of NIR in Nigeria/Africa

In Nigeria and many African countries, exposure to NIR has increased rapidly in recent years due to the widespread adoption of communication technologies and other NIR-emitting devices. The collective dose of NIR refers to the total amount of NIR absorbed by a population over a specific period, which can be influenced by various factors such as the number of people exposed, the duration of exposure, and the strength of the NIR source (Ding et al., 2019).

For example, in Nigeria, the widespread use of mobile phones and other wireless devices has led to a significant increase in the collective dose of RF radiation. Studies have found that the average Nigerian was exposed to a daily dose of RF radiation equivalent to 678 μW/m2, which is significantly higher than the recommended safety limit set by the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP). (Oyeyemi et al., 2017; Ogundele et al., 2019)

Another example is the use of microwave ovens, which emit NIR in the form of microwave radiation. In many African households, these appliances are widely used for cooking, resulting in a significant increase in the collective dose of microwave radiation (Rodriguez-Amaya, 1997). While microwave radiation is generally considered safe, prolonged exposure at high levels can cause health concerns such as thermal injury and oxidative stress (Hardell and Sage, 2008).

In summary, the collective dose of NIR in Nigeria and Africa is increasing due to the widespread adoption of NIR-emitting technologies. It is important to consider the potential health impacts of this exposure and take appropriate measures to minimize exposure and reduce the collective dose.

7. Casualties of NIR Nigeria

While the impact of NIR on human health is still a topic of ongoing research, several studies have found associations between NIR exposure and various health outcomes. In Nigeria, some of the reported casualties of NIR include increased risk of cancer, fertility problems, and neurological effects such as headaches and sleep disturbances (Samarth et al., 2002; Imam-Tamim et al., 2016).

For instance, a study conducted in Nigeria by Popoola et al. (2021) found that occupational exposure to NIR from high-voltage power lines was associated with an increased risk of childhood leukaemia. This highlights the importance of considering the potential health impacts of NIR exposure, particularly for vulnerable populations such as children.

Another example is the use of mobile phones, which emit RF radiation. In Nigeria, there have been reports of individuals experiencing headaches, fatigue, and sleep disturbances after prolonged use of mobile phones (Maduka et al., 2021). While further research is needed to confirm a causal relationship, these symptoms raise concerns about the potential health impact of RF radiation exposure.

In summary, the casualties of NIR in Nigeria include an increased risk of cancer, fertility problems, and neurological effects. It is important to continue researching to fully understand the impact of NIR on human health and to take appropriate measures to minimize exposure and reduce the associated health risks.Top of FormBottom of Form

8. Mathematical equations

Apart from the famous Maxwell’s equations, other equations from recent literature relate to NIR. One example is the SAR equation, which is commonly used to calculate the specific absorption rate (SAR) in Jkg

-1s

-1 or wkg

-1 of RF radiation in the human body. The SAR equation is given as follows:

where

p is the power absorbed by the body,

ρ is the tissue density, and

v is the volume of tissue in which the power is absorbed. The SAR equation is used to calculate the amount of RF radiation absorbed by a given tissue and is an important consideration for determining the safety of RF-emitting devices such as mobile phones and Wi-Fi routers.

Another example is the inverse-square law, which is commonly used to describe the behaviour of NIR in candela or m

-2 in a given environment. The inverse-square law states that the intensity

I of NIR decreases inversely proportional to the square of the distance

X from the source (Nguyen, 2023). The inverse-square law is given as follows:

This equation is important for understanding how the strength of NIR decreases with increasing distance from the source, which is important for evaluating the potential health impacts of NIR exposure.

In summary, several equations from recent literature relate to NIR and are important for understanding the behaviour of NIR in a given environment. These equations provide a mathematical framework for evaluating the potential health impacts of NIR exposure and making informed decisions about the responsible use of NIR-emitting technologies.

9. NIR REGULATORY BODIES

Nations all over the world on recognising the subtle yet existing influence of NIR have instituted regulatory and monitory bodies tasked with observing and investigating likely public, occupation and medical vulnerabilities in the occurrence and use of NIR. These national organisations are responsible for creating a NIR framework which controls NIR in all three dominant scenarios of exposure namely; public, medical and occupational exposure (ICNIRP, 2020). In structuring a robust NIR framework, the regulatory bodies ensure the proper implementation of the framework for the protection, certify that organisations capable of creating NIR risks maintain responsibility for care and safety, ensure the integration of efficient risk management systems (RMS) into the overall management system for companies likely to have NIR risks. The organizations also certify the correct and appropriate information concerning NIR levels, exposure, instruction and training for risk-exposed individuals and make other useful guidelines accessible and available (Tinker et al., 2022).

Regardless of each nation having an authoritative body ensuring compliance with the national laws on safety and exposure concerning NIR, ICNIRP enjoys worldwide acclaim (Buchner & Rivasi, 2020). This is because ICNIRP advises the European Commission and has strong ties with organisations and are also involved in NIR exposure reduction and protection in many nations (Buchner & Rivasi, 2020). The ICNIRP’s influence is seen in the European Commission’s and WHO’s dependence on exposure guidance and safety advice.

10. Exposure Limit to Radiation

The exposure limits of NIR differ according to national regulatory bodies. However, the classification of the NIR based on their frequency is a deciding factor in the protective measures required by the safety statutes for operating under such conditions or environments emitting NIR (Tinker et al., 2022). The inability for such specified exposure limits is because a plethora of NIR sources exists all around us; both natural and artificial. The natural sources include solar radiation, lightning storms and the earth’s EMF (McColl et al., 2015). Whereas the artificial sources are largely wireless communications and power lines. The artificial sources extend to daily used devices and equipment such as microwaves, mobile phones and WIFI networks (Tinker et al., 2022). Additionally, NIR is used in the healthcare sector for MRI scans and ultrasound testing.

Fundamentally, results have shown the most influencing factors on human exposure limit to NIR are dependent on; the interaction of the varying types of NIR interacting with the human body and the absorption properties of the human tissue. For instance, strong static magnetic fields over 2-4 T can induce vertigo and nausea and affect heart rate and blood circulation (Tinker et al., 2022). Therefore, exposure to NIR must be by the protection principles of the NIR Framework. These principles are Limitation, Justification and Optimisation. The most important of these principles is the limitation, which demands that exposure to any individual to NIR sources other than medical exposure must not exceed the appropriate limits (Modenese & Gobba, 2020).

Studies on NIR exposure in the occupational category of healthcare have revealed that nurses working in the Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) unit have signs of dizziness/vertigo, headaches and sleep disorders (Wilen & deVocht, 2011). Exposure control is poor because necessary information on exposure levels used in places like hospitals and how they can be adjusted are not made available. Such data absence requires a more in-depth study on exposure levels and limitations. The exposure limit may be covered on paper by the national legislation, but data analysing some hospital NRI exposure reveals that it often exceeded the stipulated limit. This substantiates the inadequacy of practical guidance and conscientiousness by monitoring bodies in observing and mitigating possible NIR risks (Mild, Lundstrom & Wilen, 2019).

11. Conclusion and recommendations

- i.

We see a population “suffering and smiling” due to the subtle effects that accompany the benefits of NIR if safety precautions are not strictly adhered to. Hence, the government should develop policies and set up local enforcement agencies to monitor and drive strict adherence to NIR as provided by ICNIRP.

- ii.

Going by the technological civilization, more sources of NIR are expected. Because of this, the public should expect rising background radiation and an increase in collective dose. Therefore, background radiation in living areas should be measured frequently and periodically.

- iii.

Some of the applications of NIR in treatment and diagnosis are alien in Nigeria medical practices and even the ones that are in use are not sufficient for the growing population. Applications of NIR in treatments are growing techniques in healthcare delivery especially in oncology and radiography. People now prefer the use of radiofrequency, microwave ablation, MRI, Phototherapy etc. to an incision in treatments and also because they function on low energy than ionizing radiation.

- iv.

Non-thermal effects associated with NIR are still a trending topic for debate, hence further research is to fully understand the potential risks associated with these effects. Concerning the influx of high-tech sources of NIR like Starlink, research should be carried out to ascertain their level of health risks and or health hazards.

- v.

A basic understanding of radiation protection in terms of distancing from the source; proximity to exposure and shielding in the use of sunglasses, face caps and clothing be taught in high schools and at all levels.

- vi.

Furthermore, the gospel of going green and reducing the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation to build our ozone layers and minimize the amount of EMR reaching us should be intensified at all levels of education.

Author Contributions

All the authors made substantial contributions to the concept of the article. George N., Orosun M., and Nathaniel E., critically revised the manuscript for important and valuable intellectual content. Agbo E., and Offorson G., contributed to the writing of the manuscript. However, Ndoma E. was the major contributor to the manuscript’s design, concept and writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscripts.

Funding

The work was self-funded by the authors.

Ethical approval

The authors have no conflicts of interest, and the research involves no human participants or animals.

Data Availability

All data used in this study are available in the article.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

The authors declare no competing/conflicting interests.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- Abd-Elsayed, A.; Nguyen, S.; Fiala, K. Radiofrequency Ablation for Treating Headache. Current pain and headache reports 2019, 23, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ademola, A.A. An appraisal of the cost benefit of magnetic resonance imaging in Nigeria. The Nigerian Postgraduate Medical Journal 2003, 10, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ARPANSA, n.d. radiofrequency radiation. 23 March. Available online: https://www.arpansa.gov.au/understanding-radiation/what-is-radiation/non-ionising-radiation/radiofrequency (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Aweda, M.A.; Ajekigbe, A.T.; Ibitoye, A.Z.; Evwhierhurhoma, B.O.; Eletu, O.B. Potential health risks due to telecommunications radiofrequency radiation exposures in Lagos State Nigeria. Nigerian quarterly journal of hospital medicine 2009, 19, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banik SB AS, G.S.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Ganguly, S. Bioeffects of microwave––a brief review. Bioresource technology 2003, 87, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, B.L.; Seaman, S.J.; Arora, C.; Kim, J.H. Radiofrequency ablation methods for uterine sparing fibroid treatment. Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology 2022, 34, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, J.H. Non-ionizing radiation safety: radiofrequency radiation, electric and magnetic fields. Physics in Medicine & Biology 1992, 37, 807. [Google Scholar]

- Bonjorno, A.R.; Gomes, T.B.; Pereira, M.C.; de Carvalho, C.M.; Gabardo MC, L.; Kaizer, M.R.; Zielak, J.C. Radiofrequency therapy in esthetic dermatology: A review of clinical evidences. Journal of cosmetic dermatology 2020, 19, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchner, K.; Rivasi, M. The International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection: Conflicts of interest, corporate capture and the push for 5G. 2020.

- Carrafiello, G. ; Laganà; D; Mangini, M. ; Fontana, F.; Dionigi, G.; Boni, L.; Fugazzola, C. Microwave tumors ablation: principles, clinical applications and review of preliminary experiences. International journal of surgery 2008, 6, S65–S69. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.; Shin, M.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Seo, J.E.; Lee, Y.M.; Park, C.H.; Chung, J.H. Effects of infrared radiation and heat on human skin aging in vivo. In Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings (Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 15-19). Elsevier. 2009.

- Diffey, B.L. Sources and measurement of ultraviolet radiation. Methods 2002, 28, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y. , Du, C., Qian, J., & Dong, C. M. NIR-responsive polypeptide nanocomposite generates NO gas, mild photothermia, and chemotherapy to reverse multidrug-resistant cancer. Nano letters 2019, 19, 4362–4370. [Google Scholar]

- Ekpenyong, A.S. Urbanization: its implication for sustainable food security, health and nutritional nexus in developing economies-a case study of Nigeria. Journal of Studies in Social Sciences 2015, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z.; Wei, H.; Zhang, H.; Moser MA, J.; Zhang, W.; Qian, Z.; Zhang, B. Radiofrequency ablation for liver tumors abutting complex blood vessel structures: treatment protocol optimization using response surface method and computer modeling. International journal of hyperthermia: the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group 2022, 39, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, R.P.; Lee, T.K.; Bajdik, C.D.; Borugian, M. Ultraviolet radiation. Chronic diseases and injuries in Canada 2010, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartshore, A.; Kidd, M.; Joshi, L.T. Applications of Microwave Energy in Medicine. Biosensors 2021, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, R.D.; Kinney, B.M.; Sadick, N.S. Radiofrequency Technology in Face and Neck Rejuvenation. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America 2018, 26, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, L.L.; Lim, H.W.; Mohammad, T.F. Sunscreens and photoaging: A review of current literature. American journal of clinical dermatology 2021, 22, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Avci, P.; Dai, T.; Huang, Y.Y.; Hamblin, M.R. Ultraviolet radiation in wound care: sterilization and stimulation. Advances in wound care 2013, 2, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson Mild, K.; Lundström, R.; Wilén, J. Non-ionizing radiation in Swedish health care—exposure and safety aspects. International journal of environmental research and public health 2019, 16, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson Mild, K.; Lundström, R.; Wilén, J. Non-ionizing radiation in Swedish health care—exposure and safety aspects. International journal of environmental research and public health 2019, 16, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardell, L.; Sage, C. Biological effects from electromagnetic field exposure and public exposure standards. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy 2008, 62, 104–109Top of Form. [Google Scholar]

- Hardell, L.; Sage, C. Biological effects from electromagnetic field exposure and public exposure standards. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy 2008, 62, 104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Havas, M. When theory and observation collide: Can non-ionizing radiation cause cancer? Environmental Pollution 2017, 221, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HOW STARLINK WORKS, n.d. Starlink. 23 March. Available online: https://www.starlink.com/technology (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Huang, A.H.; Chien, A.L. Photoaging: a review of current literature. Current Dermatology Reports 2020, 9, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC, 2011. IARC Classifies Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields as Possibly Carcinogenic to Humans [Press release]. Available online: https://www.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/pr208_E.pdf.

- ICNIRP. ICNIRP guidelines on limits of exposure to laser radiation of wavelengths between 180 nm and 1,000 μm. Health physics 2013, 105, 271–295.

- ICNIRP Principles for non-ionizing radiation protection. Health physics 2020, 118, 477–482. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imam-Tamim, M.K.; Oyeyipo, O.; Alajo, Y.A. The precautionary approach to the installation of telecommunication masts in residential areas in Nigeria: A legal response. IIUMLJ 2016, 24, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemarchand, G.A. The lifetime of technological civilizations and their impact on the search strategies. In Bioastronomy 2007: Molecules, Microbes and Extraterrestrial Life (Vol. 420, p. 393). 2009.

- Maduka, B.U.; Anakwue, A.M.; Abonyi, E.O.; Onwuzu, S.; Umekwe, C.N.; Uzo, E.C. Assessment of awareness of possible health effects of radiation emitted by mobile phones among University of Nigeria Enugu campus students. South African Radiographer 2021, 59, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, B.H.; Hexsel, C.L.; Hamzavi, I.H.; Lim, H.W. Effects of visible light on the skin. Photochemistry and photobiology 2008, 84, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, B.H.; Hexsel, C.L.; Hamzavi, I.H.; Lim, H.W. Effects of visible light on the skin. Photochemistry and photobiology 2008, 84, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl, N.; Auvinen, A.; Kesminiene, A.; Espina, C.; Erdmann, F.; de Vries, E.; Schüz, J. European Code against Cancer 4th Edition: Ionising and non-ionising radiation and cancer. Cancer epidemiology 2015, 39, S93–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, M.; Tei, C. Waon therapy for cardiovascular disease: innovative therapy for the 21st century. Circulation journal: official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society 2010, 74, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modenese, A. , & Gobba, F., 2020. Occupational Exposure to Non-Ionizing radiation. Main effects and criteria for health surveillance of workers according to the European Directives. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2020 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC/I&CPS Europe) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Muhammad, H.; Tehreem, A.; Russell, J.O. Radiofrequency ablation and thyroid cancer: review of the current literature. American journal of otolaryngology 2022, 43, 103204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, D.L.; Saladi, R.N.; Fox, J.L. Ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer. International journal of dermatology 2010, 49, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NASA. (2010). Infrared Waves. 23 March. Available online: http://science.nasa.gov/ems/07_infraredwaves (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- NASA, 2013. Discovering the Electromagnetic Spectrum. 23 March. Available online: https://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/science/toolbox/history_multiwavelength1.html (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Ng, K. H. , 2003. Non-ionizing radiations–sources, biological effects, emissions and exposures. In Proceedings of the international conference on non-ionizing radiation at UNITEN (pp. 1-16).

- Nguyen, C. 2023. Overcoming Inverse-square Law of Gravitation and Luminosity for Interstellar Hyperspace Navigation by Celestial Objects. arXiv e-prints, arXiv-2301.

- Ogbole, G.I.; Adeyomoye, A.O.; Badu-Peprah, A.; Mensah, Y.; Nzeh, D.A. Survey of magnetic resonance imaging availability in West Africa. The Pan African Medical Journal 2018, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogundele, L.T.; Adejoro, I.A.; Ayeku, P.O. Health risk assessment of heavy metals in soil samples from an abandoned industrial waste dumpsite in Ibadan, Nigeria. Environmental monitoring and Assessment 2019, 191, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, H. Radiobiological effects and medical applications of non-ionizing radiation. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2021, 28, 5585–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuoha, M. E. , & Elegbede, I. O., 2018. The oil boom era: Socio-political and economic consequences. In The political ecology of oil and gas activities in the Nigerian aquatic ecosystem (pp. 83-99). Academic Press.

- Owolabi, J.; Ilesanmi, O.S.; Luximon-Ramma, A. Perceptions and Experiences About Device-Emitted Radiofrequency Radiation and Its Effects on Selected Brain Health Parameters in Southwest Nigeria. Cureus 2021, 13, e18211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewopo, A.O.; Olaniyi, S.K.; Oyewopo, C.I.; Jimoh, A.T. Radiofrequency electromagnetic radiation from cell phone causes defective testicular function in male Wistar rats. Andrologia 2017, 49, 101111/and12772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyeyemi, K. D. , Usikalu, M. R., Aizebeokhai, A. P., Achuka, J. A., & Jonathan, O., 2017. Measurements of radioactivity levels in part of Ota Southwestern Nigeria: Implications for radiological hazards indices and excess lifetime cancer-risks. In journal of physics: Conference series (Vol. 852, No. 1, p. 012042). IOP Publishing.

- Panov, V.; Borisova-Papancheva, T. Application of ultraviolet light (UV) in dental medicine. Journal of Medical and Dental Practice 2015, 2, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, R.; Ardoino, L.; Villani, P.; Marino, C. In Vivo Studies on Radiofrequency (100 kHz–300 GHz) Electromagnetic Field Exposure and Cancer: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nations Online, n.d. Political Map of Nigeria. 23 March. Available online: https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/map/nigeria-political-map.htm (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Popoola, J.J.; Adu, M.R.; Itodo, E.S. Assessment of Possible Health Risks Potential of Electromagnetic Fields from High Voltage Power Transmission Lines in Akure, Nigeria. Journal of Applied Science & Process Engineering 2021, 8, 684–699. [Google Scholar]

- Pourang, A.; Tisack, A.; Ezekwe, N.; Torres, A.E.; Kohli, I.; Hamzavi, I.H.; Lim, H.W. Effects of visible light on mechanisms of skin photoaging. Photodermatology, photoimmunology & photomedicine 2022, 38, 191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Priyadharsini, R.; Kunthavai, A. Intelligent MRI Room Design Using Visible Light Communication with Range Augmentation. Intelligent Automation & Soft Computing, 2023; 35. [Google Scholar]

- Ring EF, J.; Ammer, K. Infrared thermal imaging in medicine. Physiological measurement 2012, 33, R33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Amaya, D. B. , 1997. Carotenoids and food preparation: the retention of provitamin A carotenoids in prepared, processed and stored foods (pp. 1-93). Arlington, VA: John Snow Incorporated/OMNI Project.

- Samarth, R.; Kumar, M.; Matsumoto, Y.; Manda, K. The Effects of Ionizing and Non-Ionizing Radiation on Health. Recent Trends and Advances in Environmental Health 2020, 179. [Google Scholar]

- Sasu, D. , 2022. Forecast population in Nigeria 2025-2050. 1122. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1122955/forecast-population-innigeria/.

- Schieke, S.M.; Schroeder, P.; Krutmann, J. Cutaneous effects of infrared radiation: from clinical observations to molecular response mechanisms. Photodermatology, photoimmunology & photomedicine 2003, 19, 228–234. [Google Scholar]

- Schieke, S.M.; Schroeder, P.; Krutmann, J. Cutaneous effects of infrared radiation: from clinical observations to molecular response mechanisms. Photodermatology, photoimmunology & photomedicine 2003, 19, 228–234. [Google Scholar]

- Sklar, L.R.; Almutawa, F.; Lim, H.W.; Hamzavi, I. Effects of ultraviolet radiation, visible light, and infrared radiation on erythema and pigmentation: a review. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences 2012, 12, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P. (2023). Smartphones users in Nigeria 2014 - 2025. 4671. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/467187/forecast-of-smartphone-users-in-nigeria/.

- Tertsea, I.; Barnabas, I.; Emmanuel, A. Average solar UV radiation dosimetry in Central Nigeria. International Journal of Environmental Monitoring and Analysis 2013, 1, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinker, R.; Abramowicz, J.; Karabetsos, E.; Magnusson, S.; Matthes, R.; Moser, M.; Van Deventer, E. A coherent framework for non-ionising radiation protection. Journal of Radiological Protection 2022, 42, 010501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.R.; Hamblin, M.R. Biological effects and medical applications of infrared radiation. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2017, 170, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanagas, T.; Gulbinas, A.; Pundzius, J.; Barauskas, G. Radiofrequency ablation of liver tumors (I): biological background. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) 2010, 46, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrba, J. Medical applications of microwaves. Electromagnetic Biology and Medicine 2005, 24, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrba, J. , & Lapes, M., 2004. Medical applications of microwaves. In Microwave and Optical Technology 2003 (Vol. 5445, pp. 392-397). SPIE.

- Vreman, H. J. , Wong, R. J., & Stevenson, D. K., 2004. Phototherapy: current methods and future directions. In Seminars in perinatology (Vol. 28, No. 5, pp. 326-333). WB Saunders.

- Wilén, J.; De Vocht, F. Health complaints among nurses working near MRI scanners—a descriptive pilot study. European journal of radiology 2011, 80, 510–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.H.; Lin, P.; Xu, T.T.; Wu, Y.J.; Tu, Y.C.; Wu, Y.P.; Huang, Z.D. Application of infrared thermal imaging technology in the design of free anterolateral thigh perforator flap transplantation. Zhongguo gu Shang= China Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology 2019, 32, 1053–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Zamanian, A.; Hardiman CJ HF, E. Electromagnetic radiation and human health: A review of sources and effects. High Frequency Electronics 2005, 4, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zha, X.D.; Wang, W.W.; Xu, S.; Shang, X.J. Zhonghua nan ke xue = National journal of andrology 2019, 25, 451–455.

- Zhi, W.J.; Wang, L.F.; Hu, X.J. Recent advances in the effects of microwave radiation on brains. Military Medical Research 2017, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).