Submitted:

28 April 2023

Posted:

04 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Risk factors

4. Clinical aspects

5. Pulmonary function tests

6. Radiologic aspects

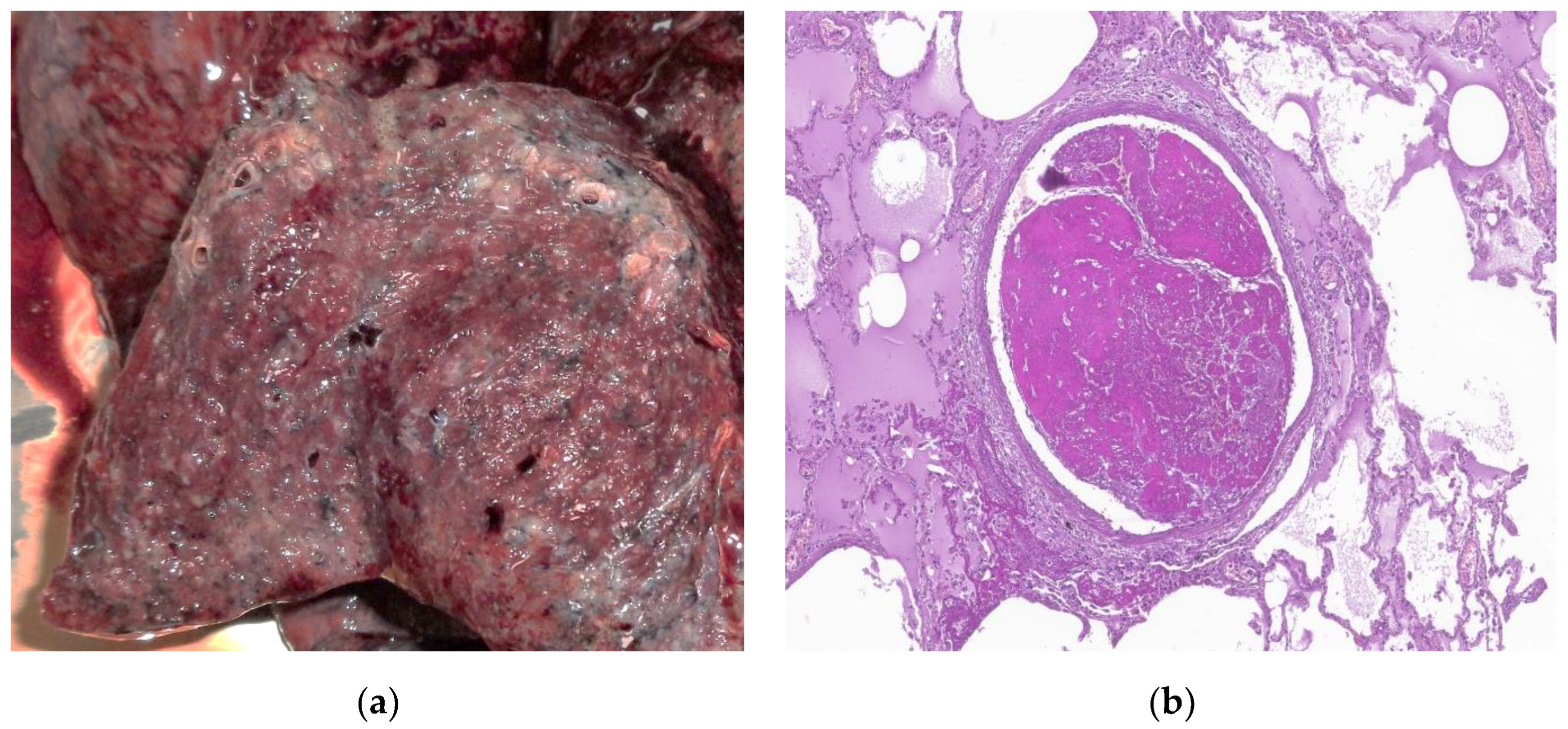

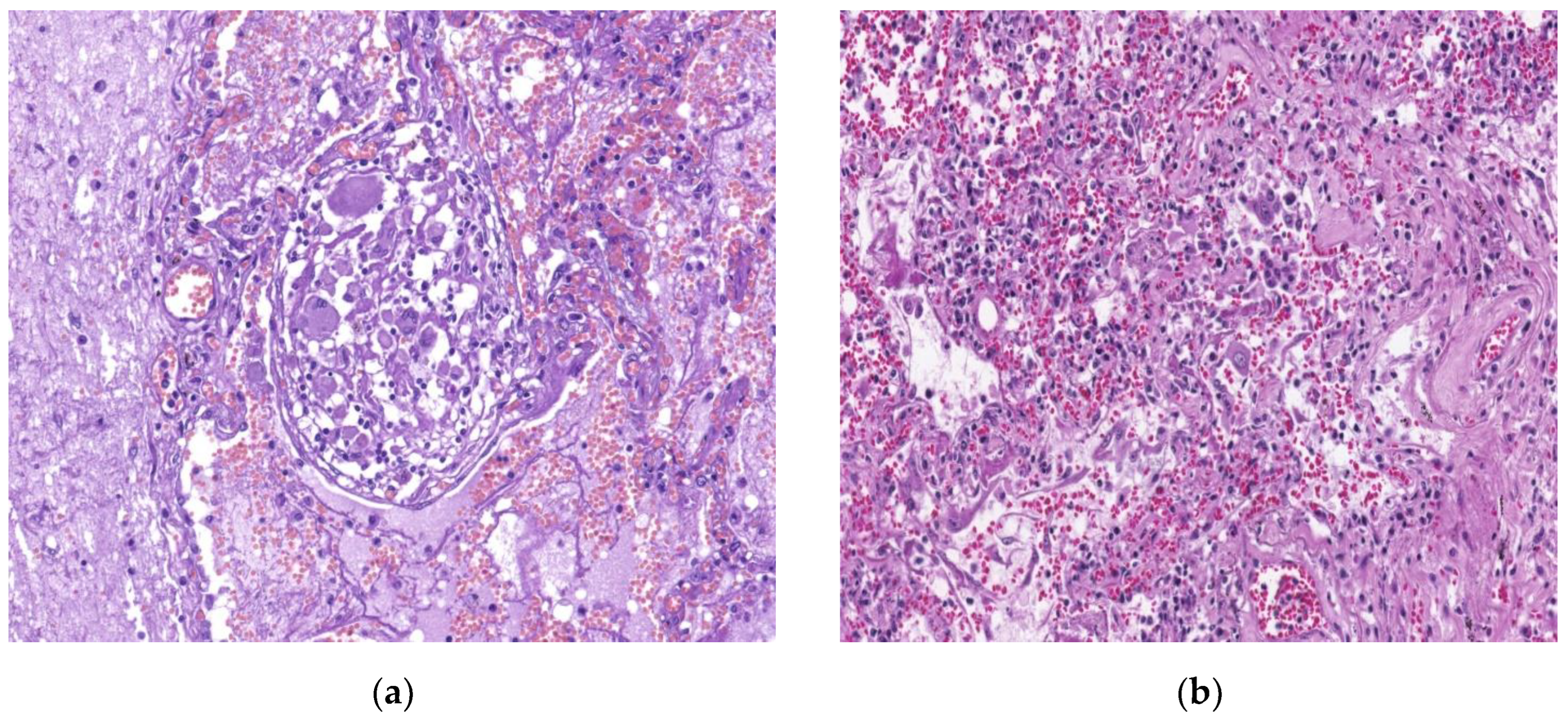

7. Histopathologic characterization

7. Therapeutic perspectives

8. Conclusions

9. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bourgonje, A.R.; Abdulle, A.E; Timens, W.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), SARS-CoV-2 and the pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Pathol, 2020, 251, 228–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi L, Z.; et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med 2020, 8, 420–422. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. Infection fatality rate of COVID-19 inferred from seroprevalence data. Bull World Health Organ 2021, 99, 19–33F. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, D.K.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, R. Post covid 19 pulmonary fibrosis. Is it real threat? Indian J. Tuberc. 2020, 68, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, N.; et al. Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pneumonia Progression Course in 17 Discharged Patients: Comparison of Clinical and Thin-Section Computed Tomography Features During Recovery. Clin Infect Dis 2020, 71, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, C.; Hu, Y.; Li, C.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, X.; Shi, H.; Zhou, M. Temporal Changes of CT Findings in 90 Patients with COVID-19 Pneumonia: A Longitudinal Study. Radiology 2020, 296, E55–E64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D. , Zhang W. ; Pan F.; et al. The pulmonary sequelae in discharged patients with COVID-19: a short-term observational study. Respir Res 2020, 21, 125. [Google Scholar]

- Carsana, L.; Sonzogni, A.; Nasr, A.; Rossi, R.S.; Pellegrinelli, A.; Zerbi, P.; Rech, R.; Colombo, R.; Antinori, S.; Corbellino, M.; et al. Pulmonary post-mortem findings in a series of COVID-19 cases from northern Italy: a two-centre descriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechowicz, K.; Drozdzal, S.; Machaj, F.; Rosik, J.; Szosta, B.; Zegan-Baranska, M.; Biernawska, J.; Dabrowski, W.; Rotter, I.; Kotfis, K. COVID-19: The potential treatment of pulmonary fibrosis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Clin. Med 2020, 9, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Fan, Y. ; Alwalid O:; Li N. ; Jia X.; Yuan M.; et al. Six-month Follow-up Chest CT Findings after Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia. Radiology 2021, 299, E177–E186. [Google Scholar]

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute website, 2019.

- Kawabata, Y. Pathology of IPF. In Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis; Nakamura, H., Aoshiba, K., Eds.; Publisher: Springer, Tokyo, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, S.L.; Creamer, A.; Hayton, C.; Chaudhuri, N. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF): An Overview. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadista, J.; Kraven, L.M.; Karjalainen, J.; Andrews, S.J.; Geller, F.; Baillie, J.K.; Wain, L.V.; Jenkins, R.; Feenstra, B. Shared genetic etiology between idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and COVID-19 severity. EBioMedicine 2021, 65, 103277–103277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvisi, M.; Ferrozzi, F.; Balzarini, L.; Mancini, C.; Ramponi, S.; Uccelli, M. First report on clinical and radiological features of COVID-19 pneumonitis in a Caucasian population: Factors predicting fibrotic evolution. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 99, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, A.S.; Balogun, S.A.; Williams, O.T.; Ojo, O.S. Pulmonary Fibrosis in COVID-19 Survivors: Predictive Factors and Risk Reduction Strategies. Pulm. Med. 2020, 2020, 6175964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, K.; Tian, J.; Zhang, S. The potential indicators for pulmonary fibrosis in survivors of severe COVID-19. J. Infect 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Liu, Y.; Xu, D.; Zhang, R.; Lan, L.; Xu, H. Prediction of the development of pulmonary fibrosis using serial thin-section CT and clinical features in patients discharged after treatment for COVID-19 pneumonia. Korean J. Radiol 2020, 21, 746–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasarmidi, E.; Tsitoura, E.; Spandidos, D.A.; Tzanakis, N.; Antoniou, K.M. Pulmonary fibrosis in the aftermath of the Covid-19 era (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 2557–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guler, S.A.; Ebner, L.; Beigelman, C.; et al. Pulmonary function and radiological features four months after COVID-19: first results from the national prospective observational Swiss COVID-19 lung study. Eur Respir J 2021, 2003690. in press. [CrossRef]

- Grasselli, G.; Pesenti, A.; Cecconi, M. Critical Care Utilization for the COVID-19 Outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: Early experience and forecast during an emergency response. JAMA 2020, 323, 1545–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogliani, P.; Calzetta, L.; Coppola, A.; et al. Are there pulmonary sequelae in patients recovering from COVID-19? Respir Res 2020, 21, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Q.; et al. Correlation analysis of the severity and clinical prognosis of 32 cases of patients with COVID-19. Respir Med 2020, 167, 105981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.J.; Xu, J.; Yin, J.M.; et al. Lower circulating interferon-gamma is a risk factor for lung fibrosis in COVID-19 patients. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 585647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velavan, T.P.; Pallerla, S.R.; Rüter, J.; Augustin, Y.; Kremsner, P.G.; Krishna, S.; Meyer, C.G. Host genetic factors determining COVID-19 susceptibility and severity. EBioMedicine 2021, 72, 103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severe Covid-19 GWAS Group. Genomewide Association Study of Severe Covid-19 with Respiratory Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1522–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covid-19 Host Genetics Initiative Mapping the human genetic architecture of COVID-19. Nature, 2021.

- Wein, A.N.; McMaster, S.R.; Takamura, S.; Dunbar, P.R.; Cartwright, E.K.; Hayward, S.L.; McManus, D.T.; Shimaoka, T.; Ueha, S.; Tsukui, T.; et al. CXCR6 regulates localization of tissue-resident memory CD8 T cells to the airways. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 2748–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropski, J.A.; Blackwell, T.S.; Loyd, J.E. The genetic basis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Mathai, S.K.; Schwartz, D.A. Genetics in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Pathogenesis, Prognosis, and Treatment. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Moorsel, C.H.M.; van der Vis, J.J.; Duckworth, A.; Scotton, C.J.; Benschop, C.; Ellinghaus, D.; Ruven, H.J.T.; Quanjel, M.J.R.; Grutters, J.C. The MUC5B Promoter Polymorphism Associates With Severe COVID-19 in the European Population. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 668024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, T.; Lee, J.S. Risk Factors for the Development of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: a Review. Curr. Pulmonol. Rep. 2018, 7, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyfman, P.A.; Gottardi, C.J. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Lung Cancer: Finding Similarities within Differences. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019, 61, 667–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, D.; Cárdenes, N.; Sellarés, J.; Bueno, M.; Corey, C.; Hanumanthu, V.S.; Peng, Y.; D’cunha, H.; Sembrat, J.; Nouraie, M.; et al. IPF lung fibroblasts have a senescent phenotype. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2017, 313, L1164–L1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.; Cho, Y.; Lockey, R.F.; Kolliputi, N. The Role of Aging in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Lung 2015, 193, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.E.; Glaspole, I.; Grainge, C.; Goh, N.; Hopkins, P.M.; Moodley, Y.; Reynolds, P.N.; Chapman, S.; Walters, E.H.; Zappala, C.; et al. Baseline characteristics of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: analysis from the Australian Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Registry. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1601592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.M.M.; Ghonimy, M.B.I. Post-COVID-19 pneumonia lung fibrosis: a worrisome sequelae in surviving patients. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2021, 52, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltz, J.W.; Card, J.W.; Carey, M.A.; DeGraff, L.M.; Ferguson, C.D.; Flake, G.P.; Bonner, J.C.; Korach, K.S.; Zeldin, D.C. Male Sex Hormones Exacerbate Lung Function Impairment after Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2008, 39, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekgabe, E.D.; Royce, S.G.; Hewitson, T.D.; Tang, M.L.K.; Zhao, C.; Moore, X.L.; Tregear, G.W.; Bathgate, R.A.D.; Du, X.-J.; Samuel, C.S. The Effects of Relaxin and Estrogen Deficiency on Collagen Deposition and Hypertrophy of Nonreproductive Organs. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 5575–5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, K.B.; Samet, J.M.; A Stidley, C.; Colby, T.V.; A Waldron, J. Cigarette smoking: a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1997, 155, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tao, Z.W.; Wang, L.; et al. Analysis of factors associated with disease outcomes in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease. Chinese Med J 2020, 133, 1032e1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardavas, C.I.; Nikitara, K. COVID-19 and smoking: A systematic review of the evidence. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2020, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.; Nizamutdinov, D.; Guerrier, M.; Afroze, S.; Dostal, D.; Glaser, S. General mechanisms of nicotine-induced fibrogenesis. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 4778–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camelo, A.; Dunmore, R.; Sleeman, M.A.; Clarke, D.L. The epithelium in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: breaking the barrier. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskar, V.S.; Coultas, D.B. Is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis an environmental disease? Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006, 3, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molyneaux, P.L.; Cox, M.J.; Willis-Owen, S.A.G.; Mallia, P.; Russell, K.E.; Russell, A.-M.; Murphy, E.; Johnston, S.L.; Schwartz, D.A.; Wells, A.U.; et al. The role of bacteria in the pathogenesis and progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 190, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.K.; Zhou, Y.; Murray, S.; Tayob, N.; Noth, I.; Lama, V.N.; Moore, B.B.; White, E.S.; Flaherty, K.R.; Huffnagle, G.B.; et al. Lung microbiome and disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: An analysis of the COMET study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, N.; Rehman, F.; Omair, S.F. Risk factors for bacterial infections in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19: A case-control study. J. Med Virol. 2021, 93, 4564–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, B.J.; So, M.; Raybardhan, S.; Leung, V.; Westwood, D.; MacFadden, D.R.; Soucy, J.-P.R.; Daneman, N. Bacterial co-infection and secondary infection in patients with COVID-19: a living rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1622–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifipour, E.; Shams, S.; Esmkhani, M.; Khodadadi, J.; Fotouhi-Ardakani, R.; Koohpaei, A.; Doosti, Z.; Golzari, S.E. Evaluation of bacterial co-infections of the respiratory tract in COVID-19 patients admitted to ICU. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhiyari, M.A.; Ata, F.; Alghizzawi, M.I.; I Bilal, A.B.; Abdulhadi, A.S.; Yousaf, Z. Post COVID-19 fibrosis, an emerging complicationof SARS-CoV-2 infection. IDCases 2020, 23, e01041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, D.A.; Sverzellati, N.; Travis, W.D.; Brown, K.K.; Colby, T.V.; Galvin, J.R.; Goldin, J.G.; Hansell, D.M.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A Fleischner Society White Paper. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfi, A.; Bernabei, R.; Landi, F. For the Gemelli against COVID-19 post-acute care study group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. J Am Med Assoc 2020, 324, 603–605. [Google Scholar]

- McGroder, C.F.; Zhang, D.; A Choudhury, M.; Salvatore, M.M.; D’Souza, B.M.; A Hoffman, E.; Wei, Y.; Baldwin, M.R.; Garcia, C.K. Pulmonary fibrosis 4 months after COVID-19 is associated with severity of illness and blood leucocyte telomere length. Thorax 2021, 76, 1242–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.; Omirah, M.A.; Hussein, A.; Saeed, H. Assessment and characterisation of post-COVID-19 manifestations. Int. J. Clin. Pr. 2020, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, C.M.; Patel, S.; E Barker, R.; George, P.; Maddocks, M.M.; Cullinan, P.; Maher, T.M.; Man, W.D.-C. Anxiety and depression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF): prevalence and clinical correlates. ERS International Congress 2017 abstracts. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. PA848.

- Lechtzin, N.; Hilliard, M.E.; Horton, M.R. Validation of the Cough Quality-of-Life Questionnaire in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest 2013, 143, 1745–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, T.; Katsura, H.; Sawabe, M.; Kida, K. A Clinical Study of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Based on Autopsy Studies in Elderly Patients. Intern. Med. 2003, 42, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvajalino, S.; Reigada, C.; Johnson, M.J.; Dzingina, M.; Bajwah, S. Symptom prevalence of patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease: a systematic literature review. BMC Pulm. Med. 2018, 18, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faverio, P.; Luppi, F.; Rebora, P.; Busnelli, S.; Stainer, A.; Catalano, M.; Parachini, L.; Monzani, A.; Galimberti, S.; Bini, F.; et al. Six-Month Pulmonary Impairment after Severe COVID-19: A Prospective, Multicentre Follow-Up Study. Respiration 2021, 100, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanematsu, T.; Kitaichi, M.; Nishimura, K.; Nagai, S.; Izumi, T. Clubbing of the Fingers and Smooth-Muscle Proliferation in Fibrotic Changes in the Lung in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest 1994, 105, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonella, F. , di Marco F., Spagnolo P. Pulmonary Function Tests in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. In: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Respiratory Medicine, Meyer K., Nathan S. Eds.; Humana Press, Cham, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Castro, R.; Vasconcello-Castillo, L.; Alsina-Restoy, X.; Solis-Navarro, L.; Burgos, F.; Puppo, H.; Vilaró, J. Respiratory function in patients post-infection by COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pulmonology 2020, 27, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Thoracic Society. British Thoracic Society Guidance on Respiratory Follow-Up of Patients with a Clinico-Radiological Diagnosis of COVID-19 Pneumonia [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/quality-improvement/covid-19/resp-follow-up-guidance-post-covid-pneumonia/.

- Cherrez-Ojeda, I.; Robles-Velasco, K.; Osorio, M.F.; Cottin, V.; Centeno, J.V.; Felix, M. Follow-up of two cases of suspected interstitial lung disease following severe COVID-19 infection shows persistent changes in imaging and lung function. Clin. Case Rep. 2021, 9, e04918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabo-Gambin, R.; Benítez, I.D.; Carmona, P.; Santiesteve, S.; Mínguez, O.; Vaca, R.; Moncusí-Moix, A.; Gort-Paniello, C.; García-Hidalgo, M.C.; de Gonzalo-Calvo, D.; et al. Three to Six Months Evolution of Pulmonary Function and Radiological Features in Critical COVID-19 Patients: A Prospective Cohort. 58, 62. [CrossRef]

- Fidler, L.; Shapera, S.; Mittoo, S.; Marras, T.K. Diagnostic Disparity of Previous and Revised American Thoracic Society Guidelines for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Can. Respir. J. 2015, 22, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, H.R.; King, T.E., Jr.; Bartelson, B.B.; Vourlekis, J.S.; Schwarz, M.I.; Brown, K.K. Changes in Clinical and Physiologic Variables Predict Survival in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 168, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, S.D.; Shlobin, O.A.; Weir, N.; Ahmad, S.; Kaldjob, J.M.; Battle, E.; Sheridan, M.J.; du Bois, R.M. Long-term Course and Prognosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis in the New Millennium. Chest 2011, 140, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanni, S.E.; Fabro, A.T.; de Albuquerque, A.; Ferreira, E.V.M.; Verrastro, C.G.Y.; Sawamura, M.V.Y.; Ribeiro, S.M.; Baldi, B.G. Pulmonary fibrosis secondary to COVID-19: a narrative review. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2021, 15, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabati, E.; Dehghani-Samani, A.; Mortazavimoghaddam, S.G. Association of COVID-19 and other viral infections with interstitial lung diseases, pulmonary fibrosis, and pulmonary hypertension: A narrative review. Can. J. Respir. Ther. 2020, 56, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Yang, H.; Lei, P.; Fan, B.; Qiu, Y.; Zeng, B.; Yu, P.; Lv, J.; Jian, Y.; Wan, C. Analysis of thin-section CT in patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) after hospital discharge. J. X-Ray Sci. Technol. 2020, 28, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francone, M.; Iafrate, F.; Masci, G.M.; Coco, S.; Cilia, F.; Manganaro, L.; Panebianco, V.; Andreoli, C.; Colaiacomo, M.C.; Zingaropoli, M.A.; et al. Chest CT score in COVID-19 patients: correlation with disease severity and short-term prognosis. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 6808–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Xi, X.; Min, X.; et al. Long-term chest CT follow-up in COVID-19 Survivors: 102-361 days after onset. Ann Transl Med 2021, 9, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, B.; Tonkin, J.; Devaraj, A.; Philip, K.E.J.; Orton, C.M.; Desai, S.R.; Shah, P.L. CT Lung Abnormalities after COVID-19 at 3 Months and 1 Year after Hospital Discharge. Radiology 2022, 303, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camiciottoli, G.; Orlandi, I.; Bartolucci, M.; Meoni, E.; Nacci, F.; Diciotti, S.; Barcaroli, C.; Conforti, M.L.; Pistolesi, M.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; et al. Lung CT Densitometry in Systemic Sclerosis. 131. [CrossRef]

- Combet, M.; Pavot, A.; Savale, L.; Humbert, M.; Monnet, X. Rapid onset honeycombing fibrosis in spontaneously breathing patient with COVID-19. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2001808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestro, E.; Cocconcelli, E.; Giraudo, C.; Polverosi, R.; Biondini, D.; Lacedonia, D.; Bazzan, E.; Mazzai, L.; Rizzon, G.; Lococo, S.; et al. High-Resolution CT Change over Time in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis on Antifibrotic Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley, B.; Elicker, B.M.; Hartman, T.E.; Ryerson, C.J.; Vittinghoff, E.; Ryu, J.H.; Lee, J.S.; Jones, K.D.; Richeldi, L.; King, T.E.; et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: CT and risk of death. . 2014, 273, 570–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Collard, H.R.; Egan, J.J.; Martinez, F.J.; Behr, J.; Brown, K.K.; Colby, T.V.; Cordier, J.-F.; Flaherty, K.R.; Lasky, J.A.; et al. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Statement: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Evidence-based Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 788–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, T.; Chong, J.-M.; Nakajima, N.; Sano, M.; Yamazaki, J.; Miyamoto, I.; Nishioka, H.; Akita, H.; Sato, Y.; Kataoka, M.; et al. Clinicopathologic and Immunohistochemical Findings from Autopsy of Patient with COVID-19, Japan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 2157–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, V.; Motwani, R.; Kumar, A.; Kumari, C.; Raza, K. Histopathological observations in COVID-19: a systematic review. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 74, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martines, R.B.; Ritter, J.M.; Matkovic, E.; et al. COVID-19 pathology working group. Pathology and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 associated with fatal coronavirus disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2020, 26, 2005–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sauter, J.L.; Baine, M.K.; Butnor, K.J.; Buonocore, D.J.; Chang, J.C.; A Jungbluth, A.; Szabolcs, M.J.; Morjaria, S.; Mount, S.L.; Rekhtman, N.; et al. Insights into pathogenesis of fatal COVID-19 pneumonia from histopathology with immunohistochemical and viral RNA studies. Histopathology 2020, 77, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Qiao, K.; Liu, F.; et al. Lung transplantation as therapeutic option in acute respiratory distress syndrome for coronavirus disease 2019-related pulmonary fibrosis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020, 133, 1390–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Xiong, Y.; Liu, H.; et al. Pathological study of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) through postmortem core biopsies. Mod Pathol 2020, 33, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Myers, J.L.; Richeldi, L.; Ryerson, C.J.; Lederer, D.J.; Behr, J.; Cottin, V.; Danoff, S.K.; Morell, F.; et al. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, e44–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, B.; Naresh, K.N.; Roufosse, C.; Nicholson, A.G.; Weir, J.; Cooke, G.S.; Thursz, M.; Manousou, P.; Corbett, R.; Goldin, R.; et al. Histopathological findings and viral tropism in UK patients with severe fatal COVID-19: a post-mortem study. Lancet Microbe 2020, 1, e245–e253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parambil, J.G.; Myers, J.L.; Aubry, M.-C.; Ryu, J.H. Causes and Prognosis of Diffuse Alveolar Damage Diagnosed on Surgical Lung Biopsy. Chest 2007, 132, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, G.R.; Artigas, A.; Brigham, K.L.; Carlet, J.; Falke, K.; Hudson, L.; Lamy, M.; Legall, J.R.; Morris, A.; Spragg, R. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1994, 149, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, M.B.; Franks, T.J.; Galvin, J.R.; Gochuico, B.; Travis, W.D. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia: a histological pattern of lung injury and possible variant of diffuse alveolar damage. . 2002, 126, 1064–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomashefski, J.F., Jr. PULMONARY PATHOLOGY OF ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS SYNDROME. Clin. Chest Med. 2000, 21, 435–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapru, A.; Wiemels, J.L.; Witte, J.S.; Ware, L.B.; Matthay, M.A. Acute lung injury and the coagulation pathway: potential role of gene polymorphisms in the protein C and fibrinolytic pathways. Intensiv. Care Med. 2006, 32, 1293–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Huang, B.; Luo, D.; Cao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; et al. Progression to fibrosing diffuse alveolar damage in a series of 30 minimally invasive autopsies with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Histopathology 2020, 78, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, P.; Wei, Y.; et al. Histopathologic Changes and SARS-CoV-2 immunostaining in the lung of a patient with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med 2020, 172, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kory, P.; Jp, K. SARS-CoV-2 organizing pneumonia: has there been a widespread failure to identify and treat this prevalent condition in COVID-19? BMJ Open Respir Res 2020, 7, e000724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommoss, F.K.; Schwab, C.; Tavernar, L.; Schreck, J.; Wagner, W.L.; Merle, U.; Jonigk, D.; Schirmacher, P.; Longerich, T. The Pathology of Severe COVID-19-Related Lung Damage. Dtsch. Aerzteblatt Online 2020, 117, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copin, M.-C.; Parmentier, E.; Duburcq, T.; Poissy, J.; Mathieu, D. ; The Lille COVID-19 ICU and Anatomopathology Group Time to consider histologic pattern of lung injury to treat critically ill patients with COVID-19 infection. Intensiv. Care Med. 2020, 46, 1124–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharat, A.; Querrey, M.; Markov, N.S.; Kim, S.; Kurihara, C.; Garza-Castillon, R.; Manerikar, A.; Shilatifard, A.; Tomic, R.; Politanska, Y.; et al. Lung transplantation for patients with severe COVID-19. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.E.; Joseph, C.; Jenkins, G.; Tatler, A.L. COVID-19 and pulmonary fibrosis: A potential role for lung epithelial cells and fibroblasts. Immunol. Rev. 2021, 302, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buja, L.M.; Wolf, D.; Zhao, B. The emerging spectrum of cardiopulmonary pathology of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): report of 3 autopsies from Houston, Texas, and review of autopsy findings from other United States cities. Cardiovasc Pathol 2020, 48, 107233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackermann, M.; Verleden, S.E.; Kuehnel, M. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burel-Vandenbos, F.; Cardot-Leccia, N.; Passeron, T. Pulmonary vascular pathology in Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 886–887. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Varga, Z.; Flammer, A.J.; Steiger, P.; Haberecker, M.; Andermatt, R.; Zinkernagel, A.S.; Mehra, M.R.; Schuepbach, R.A.; Ruschitzka, F.; Moch, H. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1417–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nienhold, R.; Ciani, Y.; Koelzer, V.H.; Tzankov, A.; Haslbauer, J.D.; Menter, T.; Schwab, N.; Henkel, M.; Frank, A.; Zsikla, V.; et al. Two distinct immunopathological profiles in autopsy lungs of COVID-19. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collard, H.R.; Ryerson, C.J.; Corte, T.J. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An international working group report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016, 194, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, M.; Nathan, S.D.; Hill, C.; Marshall, J.; Dejonckheere, F.; Thuresson, P.-O.; Maher, T.M. Predicting Life Expectancy for Pirfenidone in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. J. Manag. Care Spéc. Pharm. 2017, 23, S17–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.J.; Ni, Z.Y.; Hu, Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Bai, H.; Chen, X.; Gong, J.; Li, D.; Sun, Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost 2020, 18, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, L.; Stavrou, A.; Vanderstoken, G. Influenza promotes collagen deposition via αvβ6 integrin-mediated transforming growth factor β activation. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 35246–35263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, A.C.; Gibbons, M.A.; Farnworth, S.L.; Leffler, H.; Nilsson, U.J.; Delaine, T.; Simpson, A.J.; Forbes, S.J.; Hirani, N.; Gauldie, J.; et al. Regulation of Transforming Growth Factor-β1–driven Lung Fibrosis by Galectin-3. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 185, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.E.; Jang, G.M.; Bouhaddou, M.; Xu, J.; Obernier, K.; White, K.M.; O’Meara, M.J.; Rezelj, V.V.; Guo, J.Z.; Swaney, D.L.; et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature 2020, 583, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; van den Blink, B.; Hamblin, M.J. Effect of recombinant human pentraxin 2 vs placebo on change in forced vital capacity in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018, 319, 2299–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, F.; Xu, J.; Yang, P.; Qin, Y.; Cao, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Ye, L.; et al. Anti-hypertensive Angiotensin II receptor blockers associated to mitigation of disease severity in elderly COVID-19 patients. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skurikhin, E.; Nebolsin, V.; Widera, D.; Ermakova, N.; Pershina, O.; Pakhomova, A.; Krupin, V.; Pan, E.; Zhukova, M.; Novikov, F.; et al. Antifibrotic and Regenerative Effects of Treamid in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Phase 2 Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial and Open Label Extension to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Deupirfenidone (LYT-100) in Post-Acute COVID-19 Respiratory Disease. PureTech; Boston, MA, USA: 2020. Identifier NCT04652518.

- Bazdyrev, E.; Rusina, P.; Panova, M.; Novikov, F.; Grishagin, I.; Nebolsin, V. Lung Fibrosis after COVID-19: Treatment Prospects. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).