Submitted:

29 April 2023

Posted:

30 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

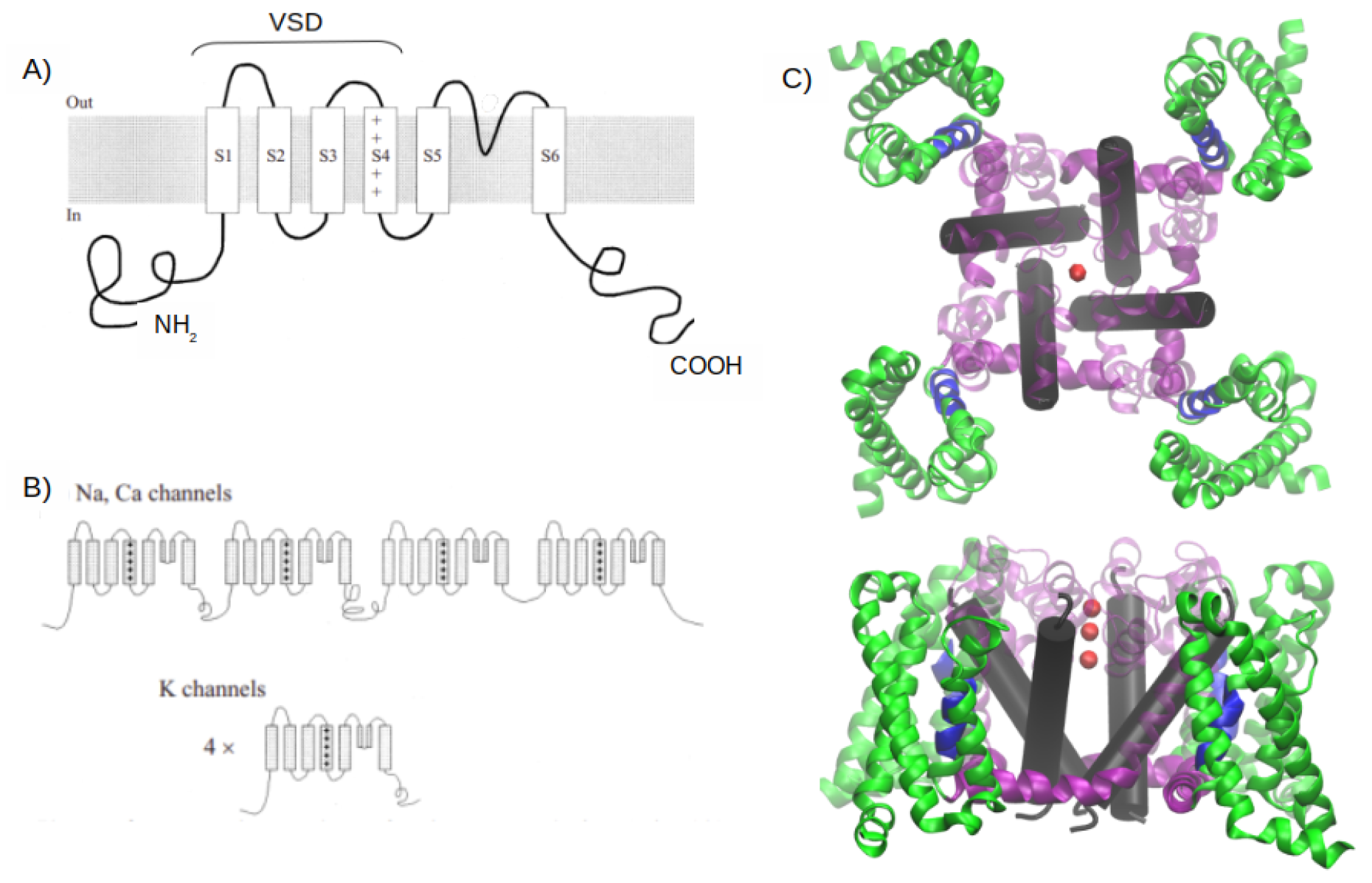

1. Introduction

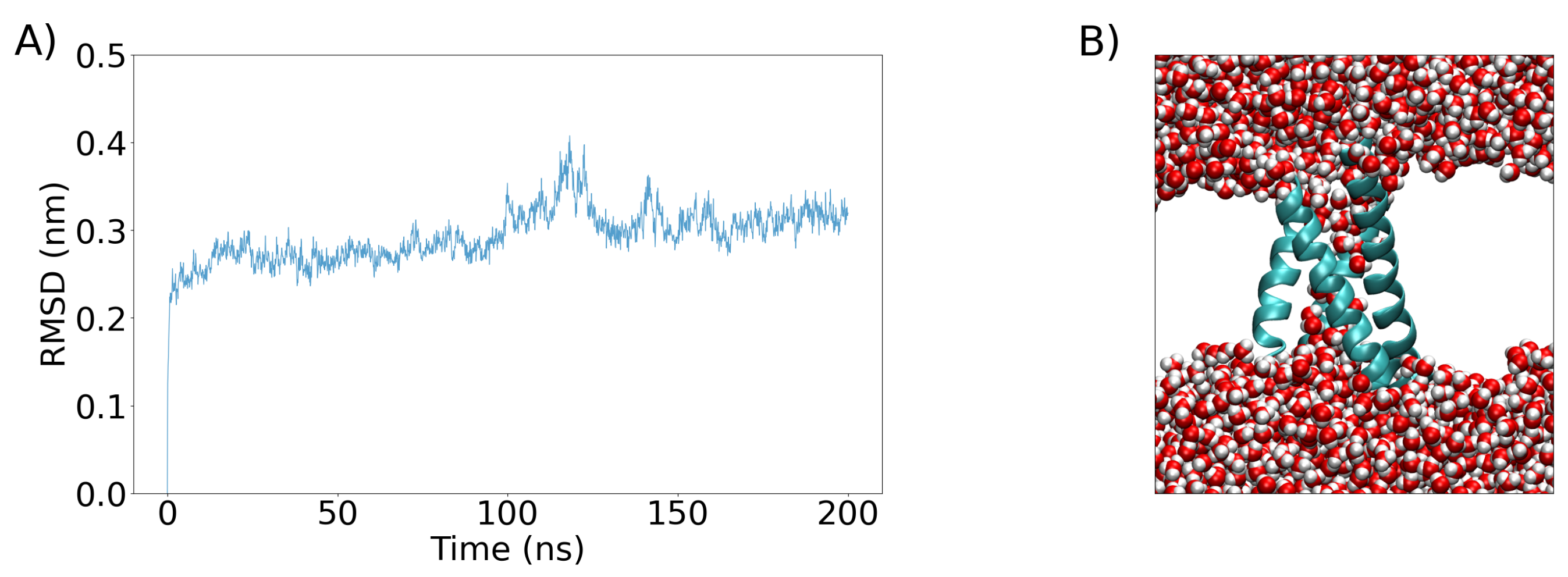

2. MD simulations methods

3. Simulation Results

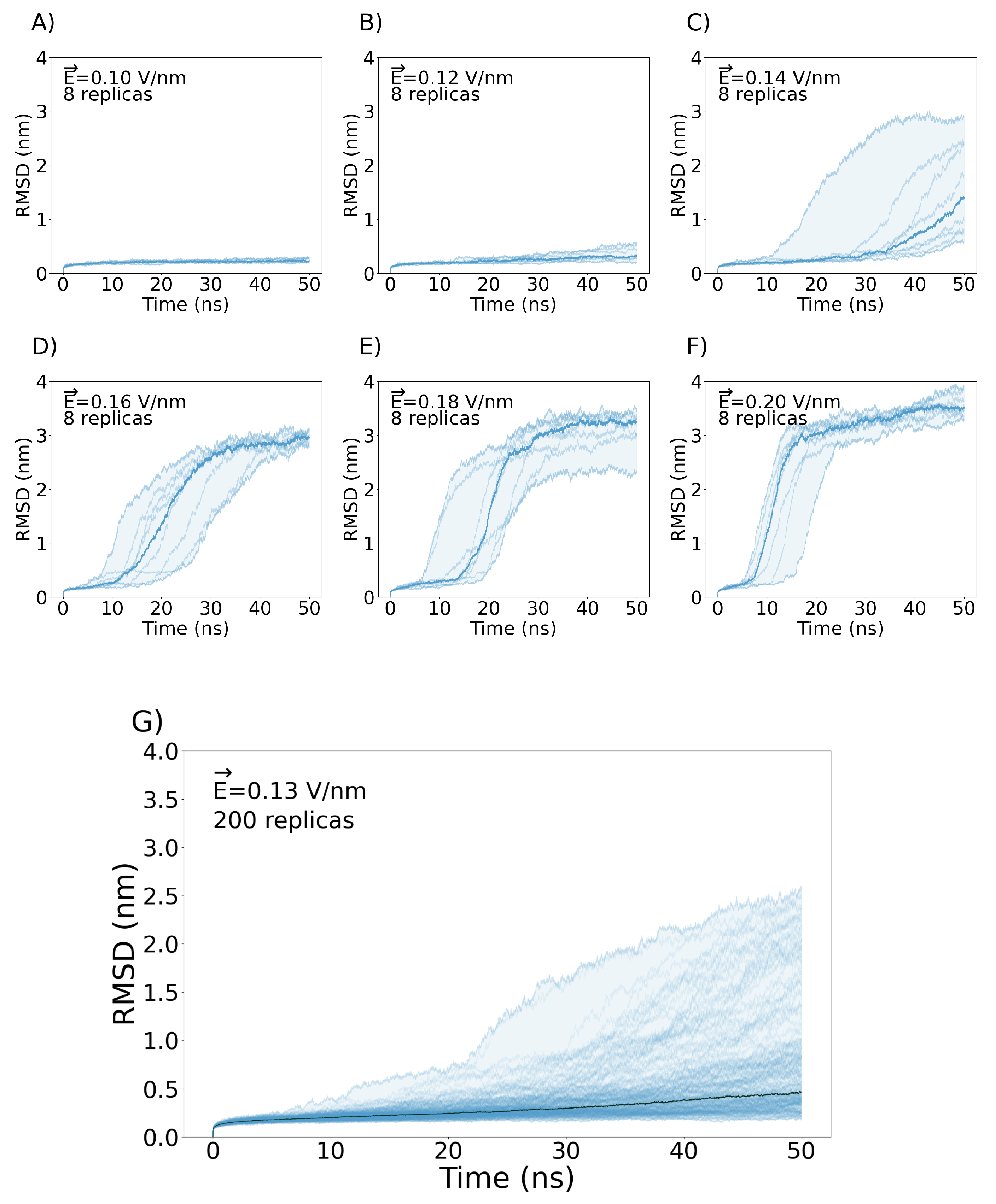

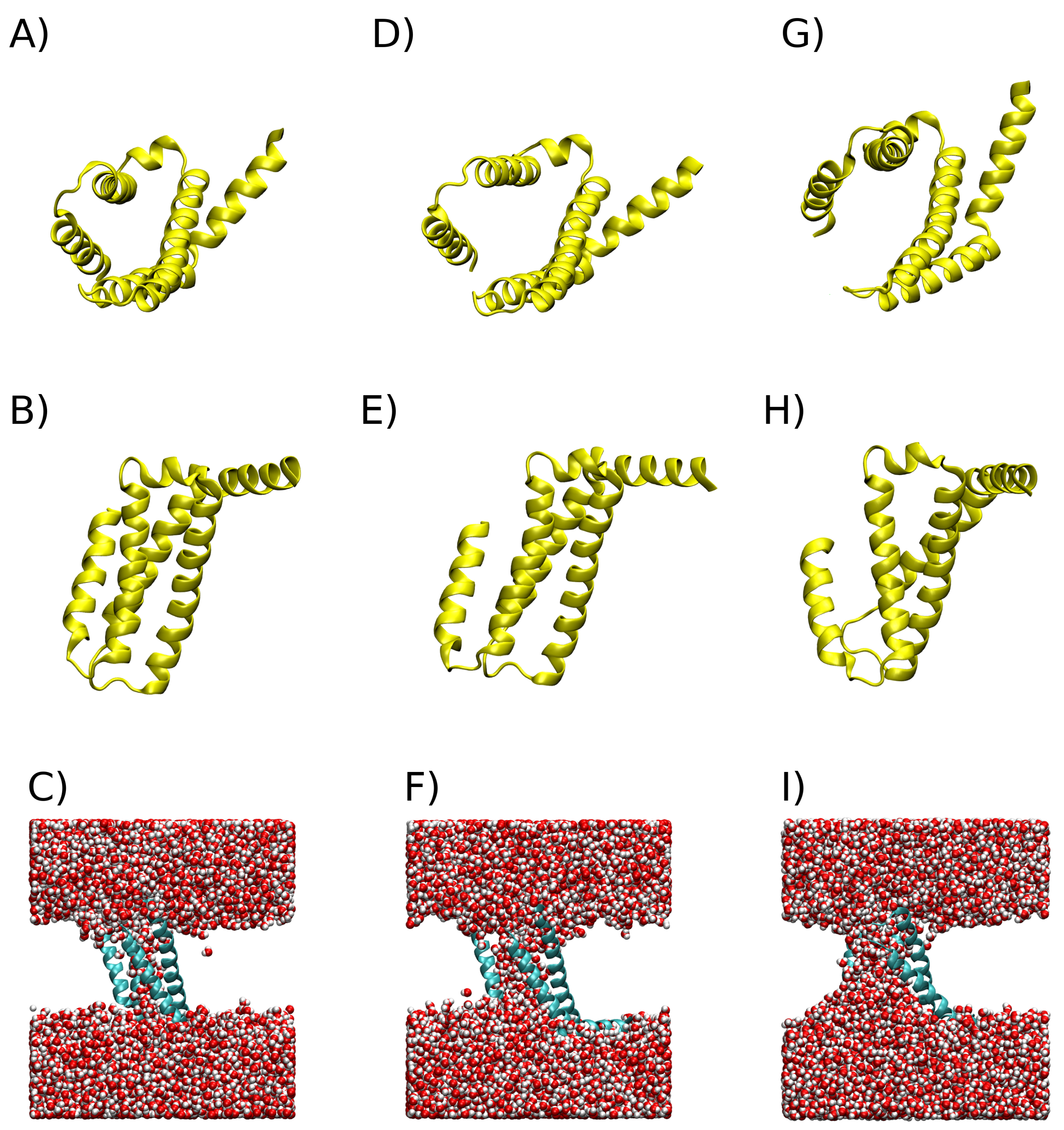

3.1. Exploring different external Electric Fields

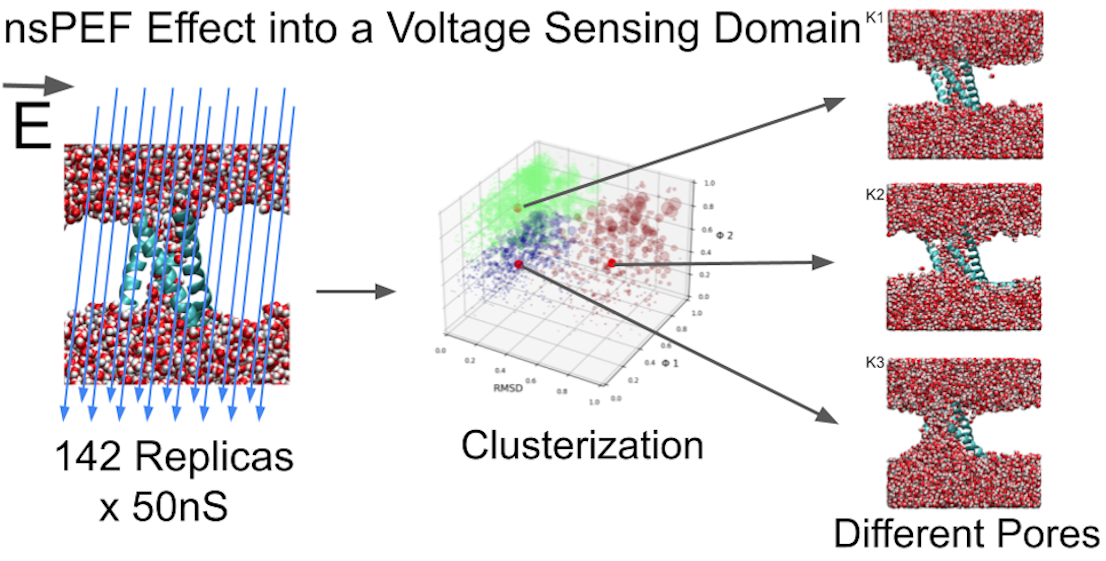

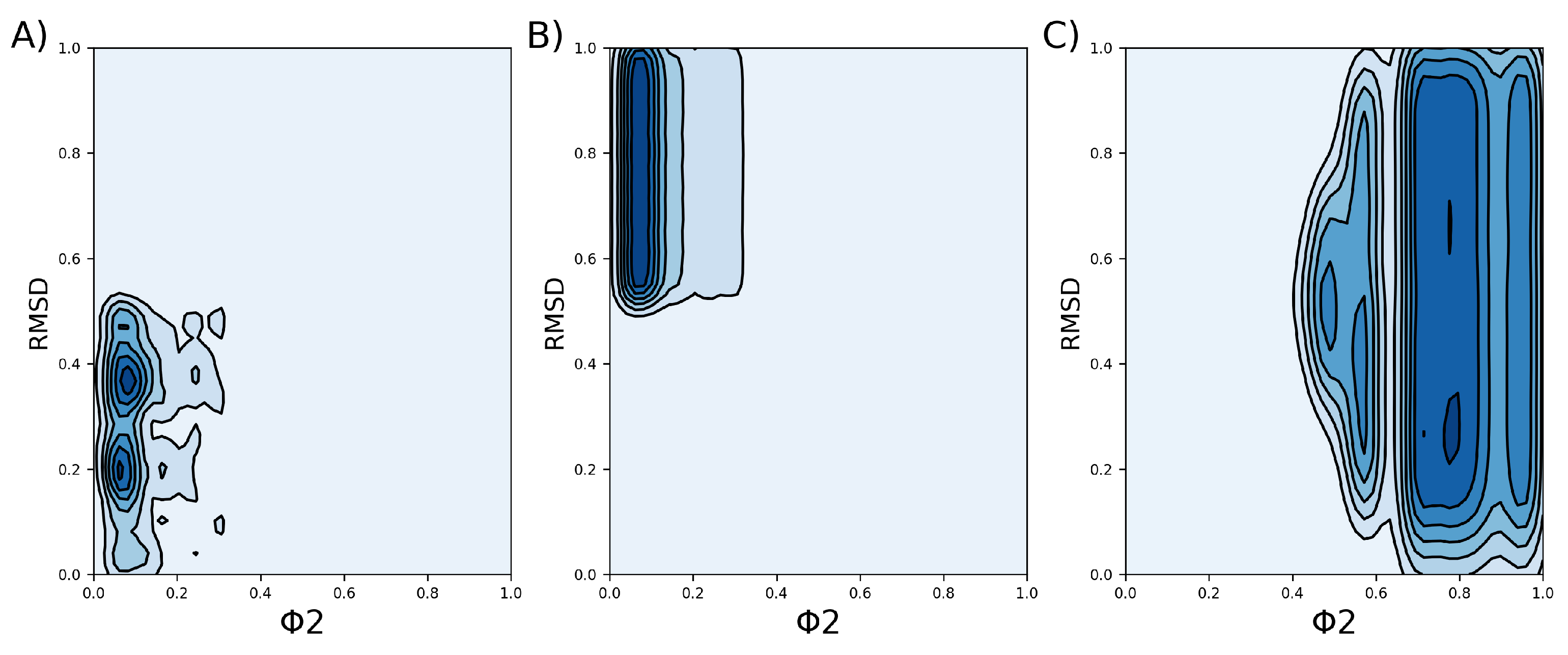

3.2. Clusterization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| nsPEF | Nanosecond Pulsed Electric Field |

| NPS | Nano Pulse Stimulation |

| VSD | Voltage Sensing Domain |

| VGC | Voltage-gated ion channels |

| Electric Field | |

| Electric Field in the z axis | |

| POPC | 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine |

| FNC | Fraction of Native Contacts |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation |

| Free Energy |

References

- Schoenbach, K.H.; Alden, R.W.; Fox, T.J. Biofouling prevention with pulsed electric fields. Proceedings of 1996 International Power Modulator Symposium. IEEE, 1996, pp. 75–78.

- Napotnik, T.B.; Reberšek, M.; Vernier, P.T.; Mali, B.; Miklavčič, D. Effects of high voltage nanosecond electric pulses on eukaryotic cells (in vitro): A systematic review. Bioelectrochemistry 2016, 110, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Fernández, A.R.; Campos, L.; Gutierrez-Maldonado, S.E.; Núñez, G.; Villanelo, F.; Perez-Acle, T. Nanosecond Pulsed Electric Field (nsPEF): Opening the Biotechnological Pandora’s Box. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 6158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craviso, G.L.; Choe, S.; Chatterjee, P.; Chatterjee, I.; Vernier, P.T. Nanosecond electric pulses: a novel stimulus for triggering Ca 2+ influx into chromaffin cells via voltage-gated Ca 2+ channels. Cellular and molecular neurobiology 2010, 30, 1259–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, C.C.; Tolstykh, G.P.; Payne, J.A.; Kuipers, M.A.; Thompson, G.L.; DeSilva, M.N.; Ibey, B.L. Nanosecond pulsed electric field thresholds for nanopore formation in neural cells. Journal of biomedical optics 2013, 18, 035005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanenko, S.; Arnaud-Cormos, D.; Leveque, P.; O’Connor, R.P. Ultrashort pulsed electric fields induce action potentials in neurons when applied at axon bundles. 2016 9th International Kharkiv Symposium on Physics and Engineering of Microwaves, Millimeter and Submillimeter Waves (MSMW). IEEE, 2016, pp. 1–5.

- Casciola, M.; Xiao, S.; Pakhomov, A.G. Damage-free peripheral nerve stimulation by 12-ns pulsed electric field. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhomov, A.G.; Semenov, I.; Casciola, M.; Xiao, S. Neuronal excitation and permeabilization by 200-ns pulsed electric field: An optical membrane potential study with FluoVolt dye. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 2017, 1859, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamberti, P.; Tucci, V.; Zeni, O.; Romeo, S. Analysis of ionic channel currents under nsPEFs-stimulation by a circuital model of an excitable cell. 2020 IEEE 20th Mediterranean Electrotechnical Conference (MELECON). IEEE, 2020, pp. 411–414.

- Wang, S.; Chen, J.; Chen, M.T.; Vernier, P.T.; Gundersen, M.A.; Valderrábano, M. Cardiac myocyte excitation by ultrashort high-field pulses. Biophysical journal 2009, 96, 1640–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, I.; Grigoryev, S.; Neuber, J.U.; Zemlin, C.W.; Pakhomova, O.N.; Casciola, M.; Pakhomov, A.G. Excitation and injury of adult ventricular cardiomyocytes by nano-to millisecond electric shocks. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarov, J.E.; Semenov, I.; Casciola, M.; Pakhomov, A.G. Excitation of murine cardiac myocytes by nanosecond pulsed electric field. Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology 2019, 30, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhomov, A.G.; Xiao, S.; Novickij, V.; Casciola, M.; Semenov, I.; Mangalanathan, U.; Kim, V.; Zemlin, C.; Sozer, E.; Muratori, C.; others. Excitation and electroporation by MHz bursts of nanosecond stimuli. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2019, 518, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Blackmore, P.F.; Hargrave, B.Y.; Xiao, S.; Beebe, S.J.; Schoenbach, K.H. Nanosecond pulse electric field (nanopulse): a novel non-ligand agonist for platelet activation. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 2008, 471, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Kiyan, T.; Blackmore, P.; Schoenbach, K. Pulsed Power for Wound Healing. 2008 IEEE International Power Modulators and High-Voltage Conference. IEEE, 2008, pp. 69–72.

- Hargrave, B.; Li, F. Nanosecond pulse electric field activation of platelet-rich plasma reduces myocardial infarct size and improves left ventricular mechanical function in the rabbit heart. The journal of extra-corporeal technology 2012, 44, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargrave, B.; Li, F. Nanosecond Pulse Electric Field Activated-Platelet Rich Plasma Enhances the Return of Blood Flow to Large and Ischemic Wounds in a Rabbit Model. Physiological Reports 2015, 3, e12461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadlamani, R.A.; Nie, Y.; Detwiler, D.A.; Dhanabal, A.; Kraft, A.M.; Kuang, S.; Gavin, T.P.; Garner, A.L. Nanosecond pulsed electric field induced proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts and myoblasts. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2019, 16, 20190079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beebe, S.J.; Blackmore, P.F.; White, J.; Joshi, R.P.; Schoenbach, K.H. Nanosecond pulsed electric fields modulate cell function through intracellular signal transduction mechanisms. Physiological measurement 2004, 25, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morotomi-Yano, K.; Uemura, Y.; Katsuki, S.; Akiyama, H.; Yano, K.i. Activation of the JNK pathway by nanosecond pulsed electric fields. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2011, 408, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Guo, J.; Ge, Z.; Zhang, J. Nanosecond pulsed electric fields (nsPEFs) regulate phenotypes of chondrocytes through Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Scientific reports 2014, 4, 5836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Jackson, D.L.; Burcus, N.I.; Chen, Y.J.; Xiao, S.; Heller, R. Gene electrotransfer enhanced by nanosecond pulsed electric fields. Molecular Therapy-Methods & Clinical Development 2014, 1, 14043. [Google Scholar]

- Estlack, L.E.; Roth, C.C.; Thompson, G.L.; Lambert, W.A.; Ibey, B.L. Nanosecond pulsed electric fields modulate the expression of Fas/CD95 death receptor pathway regulators in U937 and Jurkat Cells. Apoptosis 2014, 19, 1755–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratori, C.; Pakhomov, A.G.; Gianulis, E.; Meads, J.; Casciola, M.; Mollica, P.A.; Pakhomova, O.N. Activation of the phospholipid scramblase TMEM16F by nanosecond pulsed electric fields (nsPEF) facilitates its diverse cytophysiological effects. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2017, 292, 19381–19391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Aji, T.; Shao, Y.; Jiang, T.; Yang, L.; Lv, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Wen, H. Nanosecond pulsed electric field (nsPEF) disrupts the structure and metabolism of human Echinococcus granulosus protoscolex in vitro with a dose effect. Parasitology research 2017, 116, 1345–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, R.; Aji, T.; Shao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wen, H. Novel interventional management of hepatic hydatid cyst with nanosecond pulses on experimental mouse model. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, R.; Wen, H. Experimental nanopulse ablation of multiple membrane parasite on ex vivo hydatid cyst. BioMed Research International 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuccitelli, R.; Tran, K.; Lui, K.; Huynh, J.; Athos, B.; Kreis, M.; Nuccitelli, P.; De Fabo, E.C. Non-thermal nanoelectroablation of UV-induced murine melanomas stimulates an immune response. Pigment cell & melanoma research 2012, 25, 618–629. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Sain, N.M.; Harlow, K.T.; Chen, Y.J.; Shires, P.K.; Heller, R.; Beebe, S.J. A protective effect after clearance of orthotopic rat hepatocellular carcinoma by nanosecond pulsed electric fields. European Journal of Cancer 2014, 50, 2705–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuccitelli, R.; Berridge, J.C.; Mallon, Z.; Kreis, M.; Athos, B.; Nuccitelli, P. Nanoelectroablation of murine tumors triggers a CD8-dependent inhibition of secondary tumor growth. PLoS one 2015, 10, e0134364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuccitelli, R.; McDaniel, A.; Anand, S.; Cha, J.; Mallon, Z.; Berridge, J.C.; Uecker, D. Nano-Pulse Stimulation is a physical modality that can trigger immunogenic tumor cell death. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2017, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Jing, Y.; Burcus, N.I.; Lassiter, B.P.; Tanaz, R.; Heller, R.; Beebe, S.J. Nano-pulse stimulation induces potent immune responses, eradicating local breast cancer while reducing distant metastases. International journal of cancer 2018, 142, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skeate, J.G.; Da Silva, D.M.; Chavez-Juan, E.; Anand, S.; Nuccitelli, R.; Kast, W.M. Nano-Pulse Stimulation induces immunogenic cell death in human papillomavirus-transformed tumors and initiates an adaptive immune response. PloS one 2018, 13, e0191311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Fang, J.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Y. Nspefs Promoting the Proliferation of Piec Cells: an in Vitro Study. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Plasma Science (ICOPS). IEEE, 2017, pp. 1–1.

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, F.; Liu, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Fang, J. Nanosecond pulsed electric fields promoting the proliferation of porcine iliac endothelial cells: An in vitro study. PloS one 2018, 13, e0196688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchmann, L.; Frey, W.; Gusbeth, C.; Ravaynia, P.S.; Mathys, A. Effect of nanosecond pulsed electric field treatment on cell proliferation of microalgae. Bioresource technology 2019, 271, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Ma, R.; Su, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Fang, J. Raising the avermectins production in Streptomyces avermitilis by utilizing nanosecond pulsed electric fields (nsPEFs). Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 25949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, F.; Gusbeth, C.; Frey, W.; Maisch, J.; Nick, P. Nanosecond pulsed electrical fields enhance product recovery in plant cell fermentation. Protoplasma, 2020, pp. 1–10.

- Prorot, A.; Arnaud-Cormos, D.; Lévêque, P.; Leprat, P. Bacterial stress induced by nanosecond pulsed electric fields (nsPEF): potential applications for food industry and environment. 2011.

- Buchmann, L.; Böcker, L.; Frey, W.; Haberkorn, I.; Nyffeler, M.; Mathys, A. Energy input assessment for nanosecond pulsed electric field processing and its application in a case study with Chlorella vulgaris. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2018, 47, 445–453. [Google Scholar]

- Haberkorn, I.; Buchmann, L.; Häusermann, I.; Mathys, A. Nanosecond pulsed electric field processing of microalgae based biorefineries governs growth promotion or selective inactivation based on underlying microbial ecosystems. Bioresource Technology, 2020, p. 124173.

- Eing, C.J.; Bonnet, S.; Pacher, M.; Puchta, H.; Frey, W. Effects of nanosecond pulsed electric field exposure on Arabidopsis thaliana. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2009, 16, 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songnuan, W.; Kirawanich, P. Early growth effects on Arabidopsis thaliana by seed exposure of nanosecond pulsed electric field. Journal of Electrostatics 2012, 70, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Guo, J.; Nian, W.; Feng, H.; Wang, K.; Zhang, J.; Fang, J. Early growth effects of nanosecond pulsed electric field (nsPEFs) exposure on Haloxylon ammodendron. Plasma Processes and Polymers 2015, 12, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Fernández, A.; Rosemblatt, M.; Perez-Acle, T. Nanosecond pulsed electric field (nsPEF) and vaccines: a novel technique for the inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses? Annals of Medicine 2022, 54, 1749–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Joshi, R.; Schoenbach, K. Simulations of nanopore formation and phosphatidylserine externalization in lipid membranes subjected to a high-intensity, ultrashort electric pulse. Physical Review E 2005, 72, 031902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernier, P.T.; Ziegler, M.J.; Sun, Y.; Chang, W.V.; Gundersen, M.A.; Tieleman, D.P. Nanopore formation and phosphatidylserine externalization in a phospholipid bilayer at high transmembrane potential. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2006, 128, 6288–6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhomov, A.G.; Bowman, A.M.; Ibey, B.L.; Andre, F.M.; Pakhomova, O.N.; Schoenbach, K.H. Lipid nanopores can form a stable, ion channel-like conduction pathway in cell membrane. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2009, 385, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhomov, A.G.; Pakhomova, O.N. Nanopores: A distinct transmembrane passageway in electroporated cells. Advanced Electroporation Techniques in Biology in Medicine, 2010; 178–194. [Google Scholar]

- Semenov, I.; Xiao, S.; Kang, D.; Schoenbach, K.H.; Pakhomov, A.G. Cell stimulation and calcium mobilization by picosecond electric pulses. Bioelectrochemistry 2015, 105, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagalkot, T.R.; Terhune, R.C.; Leblanc, N.; Craviso, G.L. Different membrane pathways mediate Ca2+ influx in adrenal chromaffin cells exposed to 150–400 ns electric pulses. BioMed research international 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hristov, K.; Mangalanathan, U.; Casciola, M.; Pakhomova, O.N.; Pakhomov, A.G. Expression of voltage-gated calcium channels augments cell susceptibility to membrane disruption by nanosecond pulsed electric field. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bagalkot, T.R.; Leblanc, N.; Craviso, G.L. Stimulation or Cancellation of Ca 2+ Influx by Bipolar Nanosecond Pulsed Electric Fields in Adrenal Chromaffin Cells Can Be Achieved by Tuning Pulse Waveform. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marracino, P.; Bernardi, M.; Liberti, M.; Del Signore, F.; Trapani, E.; Garate, J.A.; Burnham, C.J.; Apollonio, F.; English, N.J. Transprotein-electropore characterization: a molecular dynamics investigation on human AQP4. ACS omega 2018, 3, 15361–15369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rems, L.; Kasimova, M.A.; Testa, I.; Delemotte, L. Pulsed electric fields can create pores in the voltage sensors of voltage-gated ion channels. Biophysical journal 2020, 119, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, J.C. Electroporation: a general phenomenon for manipulating cells and tissues. Journal of cellular biochemistry 1993, 51, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, J.C.; Vernier, P.T. Pore lifetimes in cell electroporation: Complex dark pores? arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.07478. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, J.C.; Barnett, A. Progress toward a theoretical model for electroporation mechanism: membrane electrical behavior and molecular transport. Guide to electroporation and electrofusion. 1992, pp. 91–117.

- Ruiz-Fernández, A.R.; Campos, L.; Villanelo, F.; Gutiérrez-Maldonado, S.E.; Perez-Acle, T. Exploring the Conformational Changes Induced by Nanosecond Pulsed Electric Fields on the Voltage Sensing Domain of a Ca2+ Channel. Membranes 2021, 11, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellen, G. The moving parts of voltage-gated ion channels. Quarterly reviews of biophysics 1998, 31, 239–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.; Contreras, G.F.; Peyser, A.; Larsson, P.; Neely, A.; Latorre, R. Voltage sensor of ion channels and enzymes. Biophysical reviews 2012, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delemotte, L.; Tarek, M.; Klein, M.L.; Amaral, C.; Treptow, W. Intermediate states of the Kv1. 2 voltage sensor from atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 6109–6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jin, X.; Wu, T.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W.; Lei, J.; Pan, X.; Yan, N. Structure of human Nav1. 5 reveals the fast inactivation-related segments as a mutational hotspot for the long QT syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2100069118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catterall, W.A. Voltage-dependent gating of sodium channels: correlating structure and function. Trends in Neurosciences 1986, 9, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GuY, H.R.; Seetharamulu, P. Molecular model of the action potential sodium channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1986, 83, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezanilla, F. The voltage sensor in voltage-dependent ion channels. Physiological reviews 2000, 80, 555–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Ruta, V.; Chen, J.; Lee, A.; MacKinnon, R. The principle of gating charge movement in a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature 2003, 423, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Lee, A.; Chen, J.; Ruta, V.; Cadene, M.; Chait, B.T.; MacKinnon, R. X-ray structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. nature 2003, 423, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanda, B.; Asamoah, O.K.; Blunck, R.; Roux, B.; Bezanilla, F. Gating charge displacement in voltage-gated ion channels involves limited transmembrane movement. Nature 2005, 436, 852–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, F.; Neuber, J.U.; Xie, F.; Philpott, J.M.; Pakhomov, A.G.; Zemlin, C.W. Low-energy defibrillation with nanosecond electric shocks. Cardiovascular Research 2017, 113, 1789–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesin, V.; Pakhomov, A.G. Inhibition of voltage-gated Na+ current by nanosecond pulsed electric field (nsPEF) is not mediated by Na+ influx or Ca2+ signaling. Bioelectromagnetics 2012, 33, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesin, V.; Bowman, A.M.; Xiao, S.; Pakhomov, A.G. Cell permeabilization and inhibition of voltage-gated Ca2+ and Na+ channel currents by nanosecond pulsed electric field. Bioelectromagnetics 2012, 33, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spoel, V.D.; others. GROMACS 2020.6 Source code. Zenodo.

- Huang, J.; MacKerell Jr, A.D. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: Validation based on comparison to NMR data. Journal of computational chemistry 2013, 34, 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darden, T.; York, D.; Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: An Nlog (N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. The Journal of chemical physics 1993, 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, B.; Bekker, H.; Berendsen, H.J.; Fraaije, J.G. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. Journal of computational chemistry 1997, 18, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.J.; Holian, B.L. The nose–hoover thermostat. The Journal of chemical physics 1985, 83, 4069–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrinello, M.; Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. Journal of Applied physics 1981, 52, 7182–7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. The Journal of chemical physics 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. Journal of computational chemistry 2008, 29, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibino, M.; Shigemori, M.; Itoh, H.; Nagayama, K.; Kinosita Jr, K. Membrane conductance of an electroporated cell analyzed by submicrosecond imaging of transmembrane potential. Biophysical journal 1991, 59, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, W.; White, J.; Price, R.; Blackmore, P.; Joshi, R.; Nuccitelli, R.; Beebe, S.; Schoenbach, K.; Kolb, J. Plasma membrane voltage changes during nanosecond pulsed electric field exposure. Biophysical journal 2006, 90, 3608–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benz, R.; Conti, F. Reversible electrical breakdown of squid giant axon membrane. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 1981, 645, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teissie, J.; Tsong, T.Y. Electric field induced transient pores in phospholipid bilayer vesicles. Biochemistry 1981, 20, 1548–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marszalek, P.; Liu, D.; Tsong, T.Y. Schwan equation and transmembrane potential induced by alternating electric field. Biophysical journal 1990, 58, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugar, I.P.; Neumann, E. Stochastic model for electric field-induced membrane pores electroporation. Biophysical chemistry 1984, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, D.; Rucǎreanu, C.; Victor, G. A model for the appearance of statistical pores in membranes due to selfoscillations. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry and Interfacial Electrochemistry 1991, 320, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowrishankar, T.R.; Esser, A.T.; Vasilkoski, Z.; Smith, K.C.; Weaver, J.C. Microdosimetry for conventional and supra-electroporation in cells with organelles. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2006, 341, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbart, J.; Khalili-Araghi, F.; Sotomayor, M.; Roux, B. Constant electric field simulations of the membrane potential illustrated with simple systems. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 2012, 1818, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likas, A.; Vlassis, N.; Verbeek, J.J. The global k-means clustering algorithm. Pattern recognition 2003, 36, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.J.; Richards, R.R.; Zuckerman, J.D.; Blasier, R.; Dillman, C.; Friedman, R.J.; Gartsman, G.M.; Iannotti, J.P.; Murnahan, J.P.; Mow, V.C.; others. A standardized method for assessment of elbow function. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery 1999, 8, 351–354. [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein, R.O.; Miller, C. Ion channels: shake, rattle or roll? Nature 2004, 427, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, R. Conversation between voltage sensors and gates of ion channels. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 15653–15658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonnesen, A.; Christensen, S.M.; Tkach, V.; Stamou, D. Geometrical membrane curvature as an allosteric regulator of membrane protein structure and function. Biophysical journal 2014, 106, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, O.S.; Koeppe, R.E. Bilayer thickness and membrane protein function: an energetic perspective. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2007, 36, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clusters | (J/mol) |

|---|---|

| 1-2 | -80.5 |

| 1-3 | -1,760.2 |

| 2-3 | -1,679.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).