Introduction

Many studies in Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education have examined how first-year college students suffer

in their initial courses. Due to various cognitive, intellectual, and social-psychological issues, students may suffer for various reasons (Frey et al., 2020). Students have long-standing problems applying chemical knowledge to microscopic, macroscopic, and symbolic forms; numerous studies have noted these problems and sought to offer alternatives (Talanquer, 2022). Perhaps every academic program or discipline shares the same educational goal of helping pupils develop their critical thinking and problem-solving abilities. Employing teaching and learning methodologies that engage

students and support the development of application, analysis, and evaluation process skills is essential to reaching this goal (Idul and Caro, 2022). Most instructional tactics used in Science and math are passive, which disengages students and contributes to Science's "leaky pipeline"(De Loof et al., 2022). The significant time required to prepare materials, the reluctance to cut back on the amount of material covered, and the belief that students are unwilling to participate in or prepare for these types of classroom activities are among the reasons science faculty members give for their resistance to adopt active-learning strategies. In response, the field of STEM education research has investigated numerous strategies supported by the data(Frey et al., 2020). Studies have evaluated interventions and looked at how they affected a class's overall performance, and more recently, the focus has expanded to include student subgroups inside a class(Young et al., 2022). Several researchers have examined how affective traits and social identity affect exam performance and class retention(Easterbrook and Hadden, 2021). Even other studies have looked at how students approach problems and whether they comprehend the ideas behind them or only use algorithms to solve them (Knight et al., 2015)

Science education, in general, and physics, in particular,

have tremendous contributions to the technological and digital advancement that

serves humanity (Haleem et al., 2022). Yet, in many countries, judging from

the results of international exams like the Program for International Student Assessment

(PISA), learners performed low in Science, including physics. For this research,

in the UAE, for example, the results in physics are not where they should be (Hassan

Al Marzouqi et al., 2019). Other researchers suggest that, for students,

physics is considered the most challenging area of learning within the field of

Science, and it usually magnetizes fewer students compared to other science-related

subjects from secondary school to university (Kaleva et al., 2019). Generally,

according to these authors, students tend to have a negative attitude towards physics,

presumably because they lack interest in the subject and the syllabus itself. To

make up for these negative attitudes, Asem and colleagues, in their review, argued

that “These motivate educators to use a variety of strategies to put student’s performance

in physics on a pedestal (Assem et al., 2023). Also, to address the demand

to produce learners who knew not only how to write, read and do arithmetic but learners

who can perform process skills”,

In this paper, we examined students’ differences in

concept building as potentially one key factor in explaining student struggles and

differing outcomes of otherwise similar students. We did so with two approaches.

First, we investigated the impact of POGIL-based instruction on student performance

as measured by three types of cognitive outcomes, namely: knowing, applying and

reasoning (KAR). We then extended our understanding of this concept- determine the

impacts of POGIL-based instruction on students' self-efficacy as measured by the

variable of physics learning, understanding of physics, and the willingness to learn

it in their future careers. Although the team experience of students has not received

much attention in physics, previous research has looked at characteristics that

affect student results in physics. Self-efficacy, which has repeatedly been demonstrated

to be a critical construct that predicts student success in physics, particularly

problem-solving, is one of the factors. Bandura first defined self-efficacy as the

conviction that one can "successfully execute the behaviour required to produce

the outcomes" (Bandura, 1977). Bandura also made the case that one's self-efficacy

beliefs influence how much effort one will put into a task and how long one will

persevere in the face of setbacks.

According to research, self-efficacy is a significant

predictor of student performance in STEM education, even when other factors (such

as prior academic experience, success indicators, behavioral traits, self-esteem,

learning styles, and learning strategies) are considered. While self-efficacy is

the most significant predictor of performance, Lishinski and colleagues discovered

that it also has a reciprocal effect, where self-efficacy influences performance,

which then influences self-efficacy, which again influences performance (Sakellariou

and Fang, 2021). We also intended to investigate how students' views of collaborative

learning in teams and their actual learning were related to their sense of self-efficacy.

Contribution to the Literature

The present study fills a gap in the literature regarding

the main learning difficulties and alternative conceptions of pre-service teachers

concerning the digestive system.

First, of its kind in the UAE, the present study is vital in understanding the benefits of inquiry-based approaches to learning.

This research study represents a deep investigation of the theoretical frameworks of the POGIL in teaching Science in particular. Such strategies are vital in ensuring learners exploit their abilities in areas like knowing, applying and reasoning in an implicit manner that guides their acquisition of the recommended skills and competencies.

As shown, such competencies are attained due to the determination of the impact of POGIL-based instruction on improving self-efficacy in physics. The data collected for this study is hoped to guide the field practices in science teaching and learning.

Literature Review

POGIL is a strategy and a philosophy for learning and

teaching. It is a strategy since it provides a specific methodology and procedural

structure that are constant with the method students learn and that lead to the

desired learning outcomes. It is also a philosophy as it involves specific ideas

about the nature of the learning process and the expected learning outcomes (Brown,

2010). Based on social constructivist learning theory, POGIL is a student-centred

teaching method science educators developed in the 1990s. Here, learners develop

their conceptual understanding collaboratively and work in groups on carefully designed

learning cycle activities (Le et al., 2018).

Soltis and his group argue that it helps students construct

their scientific understanding based on their prior knowledge, experiences, skills,

attitudes, beliefs and self-efficacy(Soltis et al., 2015). The students,

Soltis and colleagues explain, also experience a learning cycle of exploration,

concept formation, and application. Besides, students using the POGIL module connect

and visualize concepts and multiple representations and discuss and interact with

one another.

To shed some light on the roles of the POGIL group,

the manager ensures that the members are doing their roles, achieving the

tasks on time, and all members are participating in the activities and understanding

the concepts. The recorder reports the discussions and essential aspects

of the group’s observations, insights and the significant concepts learnt. The “presenter”

provides oral reports to the class. The “reflector” observes group dynamics,

behaviour and performance and may report to the group (or the class) about how well

the group operates (Hu and Shepherd, 2013). The POGIL activities emphasize core

concepts and encourage a deep understanding of the course materials through an exploration

to construct understanding while developing higher thinking skills. Here, Trevathan

and Myers explain that learning is achieved through fun exercises that prove effective

to students with the benefits of shared information and collaborative learning(Trevathan,

Jarrod, and Myers, 2013).

A study by Walker and Warfa established that students

that taught using a POGIL-based instructional strategy registered higher levels

of achievement and developed positive attitudes towards using the approach(Walker

and Warfa, 2017). On the other hand, Lin and Tsai established that using the POGIL-based

instructional approach enhanced the ability of the students to perfect their learning

capabilities compared to other approaches(Lin and Tsai, 2013). Further, Wozniak

found that using POGIL was instrumental in identifying the different conceptions

by students and facilitated their ability to change or alter such conceptions(Wozniak,

2012). However, a study by Barthlow contrasts these findings as the study found

that the learners that taught using POGIL did not have any different or alternative

conceptions compared to the learners that have been taught using the traditional

forms of instruction. In sum, one has to keep an open mind when analyzing later

in the research study and be cautious with the conclusions one reaches(Barthlow

and Watson, 2014).

Deora and colleagues conducted research in the U.S.

to examine the impact of the flipped classroom and POGIL methods on the chemistry

of college students (Nipa Deora, Nathalie Rivera, Sheila Sarkar, Marcos Betancourt,

2020). The results revealed positive trends favouring POGIL students. Unlike Barthlow’s

study, however, no significant differences were found between students’ overall

grades learnt by POGIL and their counterpart students learnt by traditional instruction.

However, there was an increase in passing grades(Barthlow and Watson, 2014).

Self-efficacy is the learners’ belief in their ability

to accomplish tasks in specific situations, that is, their competencies to organize

and complete courses of action required to achieve selected types of performances(Artino

Jr., 2012). Since self-efficacy is confidence in one’s ability to perform, which

will be reflected in students' actions. Students with high self-efficacy for performing

a specific task will have high expectations towards performing it and are likely

to succeed, for example, in Science at school and choose majors that align with

their self-belief about personal competencies and abilities (Kaleva et al.,

2019).

Situated within the social cognitive theory, self-efficacy

indicates behaviour can be best understood in terms of a reciprocal system, including

reasoning, behaviour and context. This reciprocal system, Lin explains, refers to

the perceived ability to carry out the task, behaviour, performance, and environment

setting(Lin, 2009). Within this reciprocal system, moreover, self-efficacy becomes

a vital construct for learners to monitor their performance as it attracts their

attention to beliefs about the effectiveness of their learning methods (Anam and

Stracke, 2016).

Examining students' attitudes toward using POGIL in

teaching physics is essential, and this can help us better understand the impact

of POGIL on students’ attitudes and science learning achievement. For this study

and the subsequent discussion, by attitude towards Science, I am referring to “the

feelings, beliefs, and values held about an object that may be the enterprise of

science, school science, the impact of science on society or scientists themselves.”

(Osborne et al., 2003).

Though the previous studies have not tackled POGIL directly,

they shed light on the relationships between students’ attitudes and their science

learning that might be done through POGIL or any other methods or models of inquiry.

These conclusions are highly relevant and essential to this study. The same relevance

can be seen in the studies discussed in the following paragraphs(Vishnumolakala

et al., 2017).

In the Philippines, a quantitative study was conducted

by Guido to analyze and evaluate the relationship between engineering and technology

students’ attitudes and motivations towards learning physics. The study's results

found no significant difference in the attitude and motivation of students towards

learning physics. Furthermore, most students participating in the study felt good

when they were successful in physics (Guido, 2013). The students thought that their

success was due to the simple and practical method of teaching used by teachers,

which enhanced their attitude towards physics learning. The participants also enjoyed

studying physics since they could see its utility in everyday life.

Despite the prevalence of studies that are based on

the efficacy of the use of constructivist methodologies in teaching students, a

gap exists in the literature due to the lack of studies that involve high school

students in the use of inquiry-based instruction, especially the use of approaches

such as POGIL in the UAE context (Daubenmire et al., 2015). An instrument-based

survey conducted in the UAE by Tairab and Al-Naqbi that evaluated the effectiveness

of constructivist pedagogical strategies established unanimity between students

and teachers that most curriculum materials require inquiry-based instructional

strategies to enhance effectiveness (Tairab and Al-Naqbi, 2017). A study by Al-Naqbi

showed significant differences in high school students' perceptions of chemistry

as a subject, chemistry research and jobs related to chemistry. In the self-efficacy

scale, the main differences amongst the students were found in their performance,

scores, and the percentiles of the secondary schools. However, regarding gender,

nationality and matriculation, there were no significant or notable differences

among the students on the self-efficacy scale(Al-Naqbi and Alshannag, 2018). Another

quasi-experimental study was carried out by Qureshi and Visnumolakala to explore

Qatari Foundation first-year students’ understanding of chemistry concepts in a

POGIL context (Qureshi et al., 2017). The study's results found positive

effects of POGIL on students’ understanding of chemistry concepts. The authors thus

concluded that student-centred pedagogical practices like POGIL enhanced students’

understanding of the field of Science.

Results

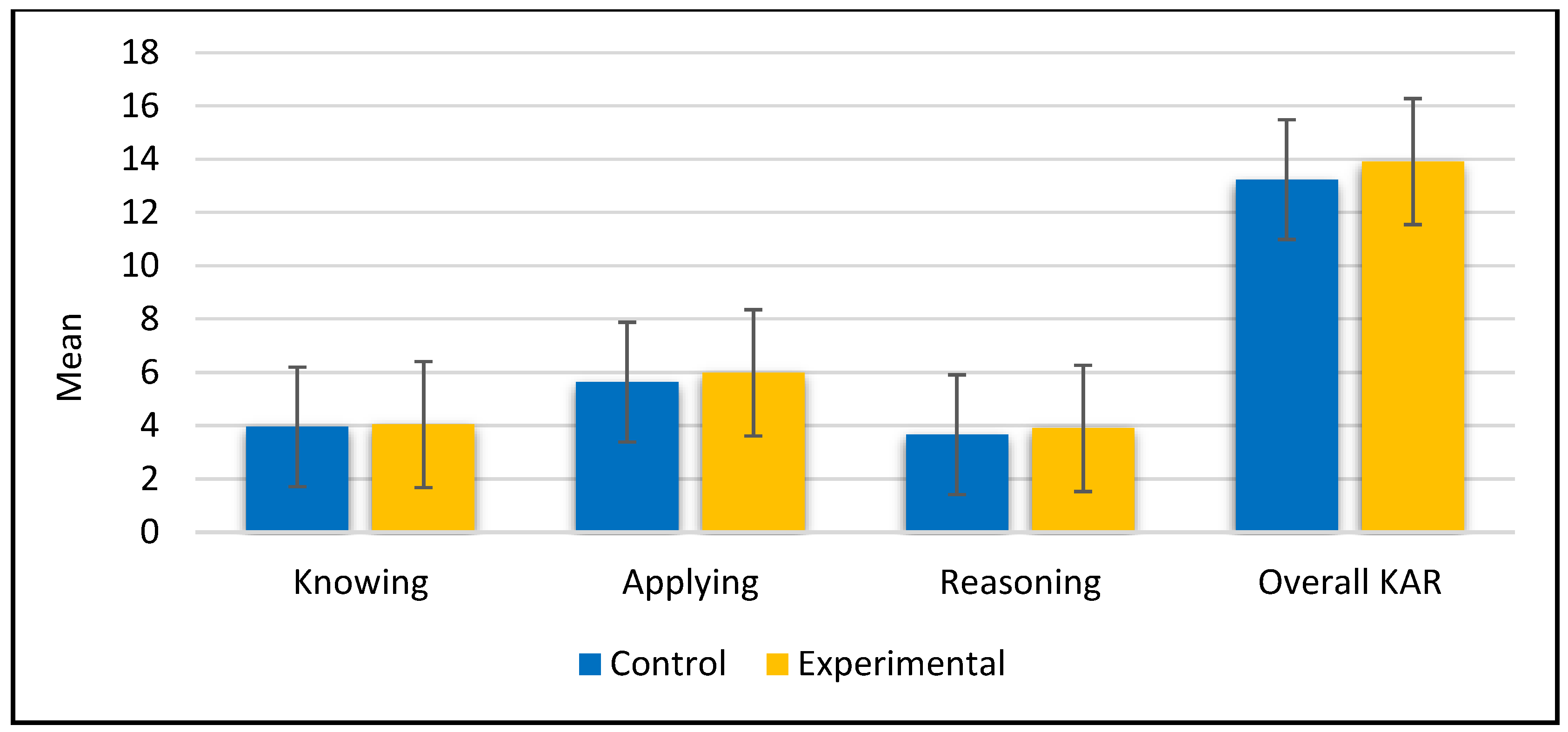

The results presented in

Table 1 display the test scores of (KAR) in the

pretest in the control group taught by the lecturing-based instruction method and

the experimental group taught by POGIL-based instruction.

Table 1 (above)

and

Figure 1 showed that participants’ Applying

abilities were the highest in both groups (Control Group M = 5.63, SD = 1.46) and

(Experimental Group M=5.98, SD =1.84), followed by their Knowing abilities (Control

Group M = 3.93 and SD =1.10) and (Experimental Group M= 4.02, SD =1.21). However,

participants’ Reasoning abilities were reported to be the lowest in both groups

(Control Group M= 3.66, SD = 1.07) and (Experimental Group M= 3.89, SD =1.18). In

the total score of the cognitive outcomes Test (KAR), participants scored higher

in the experimental group (M= 13.91, SD =2.33) than in the control group (M= 13.23,

SD = 2.00).

A T-test for Equality of Means for independent samples

was conducted to find if there were statistically significant differences between

the mean scores of the pretest measured in this study in the circular motion unit

in the physics curriculum of grade 12 in both control and experimental groups before

the intervention. The results of the T-test showed that there were no statistically

significant differences between the control group (M =3.93, SD = 1.10) and experimental

group (M = 4.02, SD =1.21) about students’ knowing abilities (), which indicated that the performance of the students

in the pretest of knowing was the same.

In addition, no statistically significant difference

was found between the control group (M =5.63, SD = 1.46) and experimental group

(M =5.98, SD =1.84) about students’ applying abilities (), which indicated that the performance of the students

in the pretest of applying abilities was the same. Moreover, no statistically significant

difference was shown between the control group (M = 3.66, SD = 1.07) and experimental

group (M= 3.89, SD =1.18) regarding students’ reasoning abilities (), which indicated that the performance of the students

in the pretest of reasoning abilities was the same.

Overall, no statistically significant difference was

found between the control group (M = 13.23, SD = 2.00) and experimental group (M

= 13.91, SD =2.33) regarding student performance in the total score of the cognitive

outcomes Test of (KAR) since (), which indicated that the

performance of the students in the pretest of KAR was the same. The same results

were obtained after using the Bonferroni adjusted significance criterion of the

p-value 0.05. The adjusted p-value was = 0.0125 (.05/4) since four tests

were conducted. As Huck (2011) showed, Bonferroni adjusted the significance criterion

of the p-value can be obtained by “dividing the desired Type I error risk for the

full study by the number of times the hypothesis testing procedure will be used”.

As presented in

Table 2, the participants’ applying ability for the control group was the highest

(M = 5.84, SD = 1.35), followed by their reasoning ability (M = 3.96, SD =1.39).

However, participants’ knowing ability was reported as the lowest (M= 3.64, SD =

1.10). In the total score of the cognitive outcomes of (the KAR) test, participants

scored a mean of 13.45 (SD = 2.00). To deduct whether there were statistically significant

differences between the means of the scores of the Knowing, Applying and Reasoning,

and overall (KAR) in the pretest and post-test for the control group, the researcher

ran Paired sample T- test for related samples. Results of Paired sample T-test indicated

no significant difference in means of the students’knowing scores in the pretest and post-test

for the control group (

). No significant

difference was shown in means of the students’ applying scores (

, and no significant

difference was shown in means of the students’ Reasoning scores (

.

Overall, no significant difference in means of total scores

of the Cognitive Outcomes of the (KAR) in the pretest and post-test for the control

group (

. We can conclude that the student's performance in the cognitive

outcomes of the (KAR) in the pretest and post-test for the control group was the

same. The same results were obtained after using the Bonferroni adjusted significance

criterion of the

p-value 0.05. The adjusted p-value was = 0.0125 (.05/4)

since four tests were conducted.

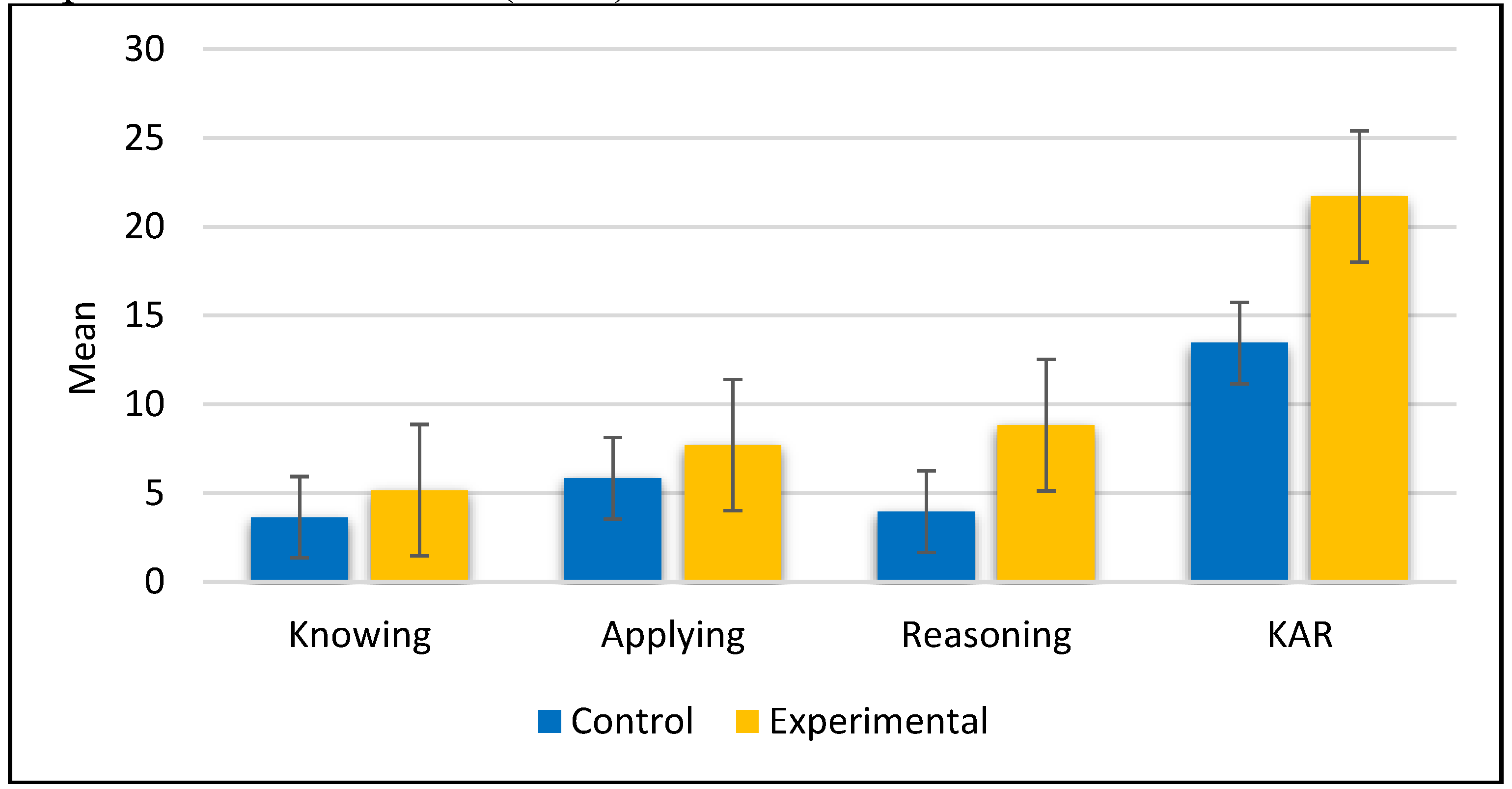

Table 3 above

and

Figure 2 showed that participants’ reasoning

ability was the highest in the experimental group (M = 8.83, SD = 1.41). Applying

ability came with a mean of 7.70 (SD=2.13), while participants’ knowing ability

was the lowest (M = 5.17, SD = 0.88). Concerning the control group, participants’

applying ability was the highest (M = 5.84, SD = 1.35). Reasoning ability came with

a mean of 3.96 (SD=1.39), while participants’ knowing ability was the lowest in

the control group (M = 3.64, SD = 1.10). In the total score of the cognitive outcomes

Test (KAR), participants scored higher in the experimental group (M= 21.70, SD =2.96)

than in the control group (M= 13.45, SD = 2.00). Independent Samples T-test was

conducted to find if there were tatistically significant differences between the mean scores

of the post-test measured in this study in the circular motion unit in the physics

curriculum of grade 12 in both control and experimental groups after the intervention.

The results of T- the test for independent samples showed

that statistically, there was a highly significant difference between the control

group and experimental group regarding students’ knowing abilities in favour of

the experimental group (, which indicated that the students in the experimental

group were more likely had a high knowing performance after the intervention, comparing

to control group. In addition, statistically, there was a highly significant difference

found between the control group and experimental group regarding students’ applying

abilities in favour of the experimental group (, which indicated that the students in the experimental

group were more likely to had a high applying performance in applying after the

intervention, comparing to control group.

The results of the t-test test for independent samples

showed that statistically, there was a highly significant difference between the

control group and experimental group regarding students’ reasoning abilities in

favour of the experimental group (, which indicated that the students in the experimental

group were more likely to had a high reasoning performance reasoning after the intervention,

comparing to control group.

Statistically, there was a highly significant difference

found between the control group and experimental group regarding student performance

in the total score of the cognitive outcomes of (the KAR) Test ( in favour of the experimental group. We can conclude

that the students in the experimental group were more likely to have a high performance

in the overall KAR after the intervention compared to the control group. The same

results were obtained after using the Bonferroni adjusted significance criterion

of the p-value 0.05. The adjusted p-value was = 0.0125 (.05/4) since four

tests were conducted.

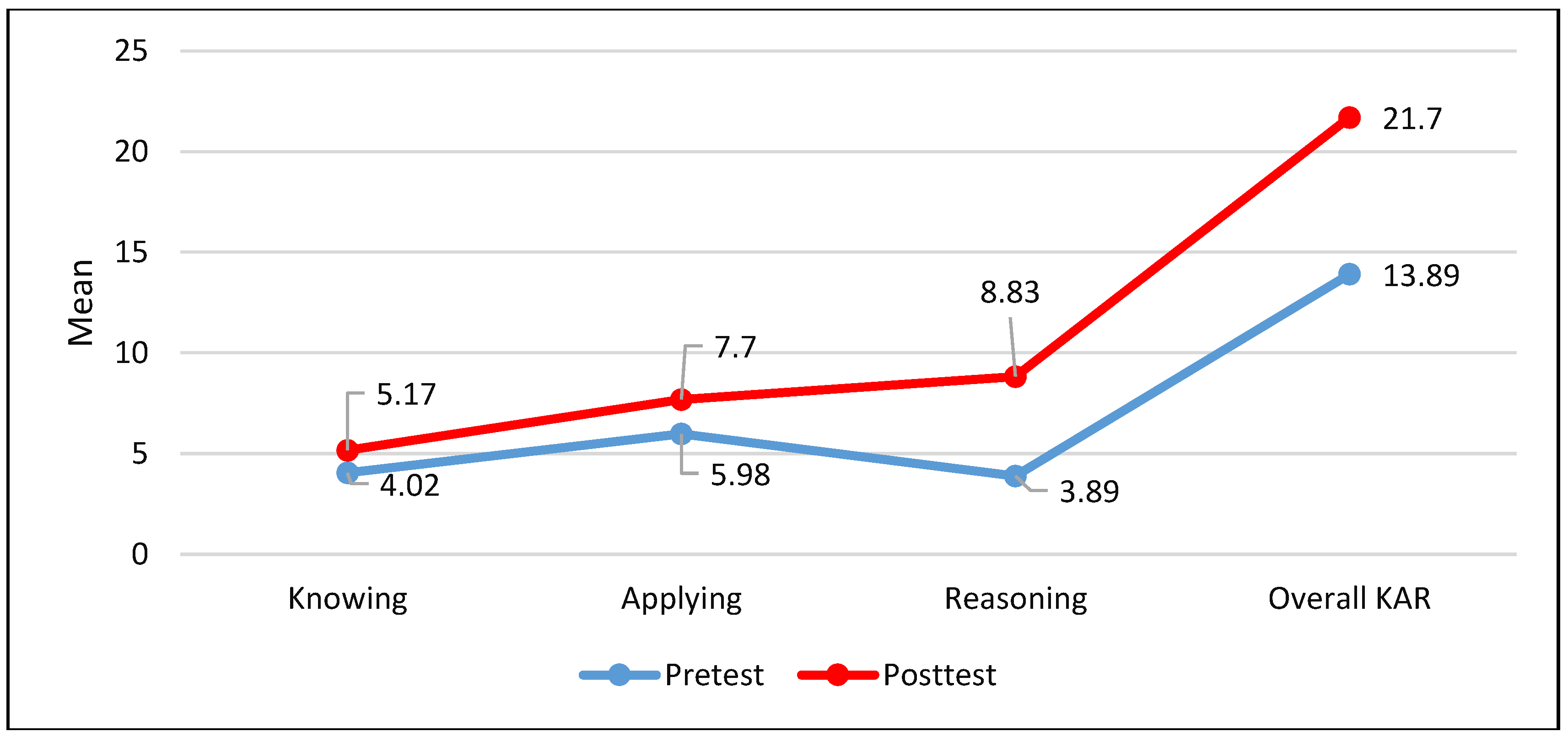

The results in

Table 4 display the Paired Sample T-test for related samples of the scores of three subscales of (the KAR) test in the pretest and post-test for the experimental group

taught by POGIL-based instruction. The results indicated that there was a highly

significant difference in means of the scores of knowing in favour of post-test

(

. The mean knowledge scores

for students in the post-test were higher than that observed in the pretest. Students

in the experimental group were more likely to have high performance in knowing after

the intervention, compared with their scores in the pretest. In addition, there was a highly significant difference in means

of the scores of applying in favour of post-test (

. The mean scores of applying

students in the post-test were higher than that observed in the pretest. Students

in the experimental group were more likely to have high performance in applying

after the intervention, compared with their scores in the pretest.

Moreover, there was a highly significant difference

in means of the scores of reasoning in favour of the post-test (. The mean reasoning scores for students in the post-test

were higher than that observed in the pretest. Students in the experimental group

were more likely to have high performance in reasoning after the intervention, compared

with their scores in the pretest. Overall, there was a highly significant difference

in means of the total scores of (KAR) in favour of the post-test (. The mean scores of KAR for students after the intervention

were higher than that observed in the pretest. Students in the experimental group

were more likely to have high performance in the KAR test after the intervention,

compared with their scores in the pretest.

The same results were obtained after using the Bonferroni

adjusted significance criterion of the p-value 0.05. The adjusted p-value

was = 0.0125 (.05/4) since four tests were conducted.

In addition, the researcher

calculated the Effect Size of the POGIL-based instruction for the post-scores

of the experimental group in each subscale of the KAR test.

The Effect size (d) through T-test for related samples

given by

Where Mean difference= Difference between means of pre

and post-tests

SD.diff. = Pooled Standard Deviation

Using the data presented in Table 11, the effect size of the POGIL approach

for knowing scores for the experimental group will be:

The effect size calculated above shows that the percentage

of the POGIL approach for knowing scores for the experimental group is 75%. This

percentage indicates that this tool is effective in elevating knowing ability among

the students in the experimental group by approximately 0.75 level of standard deviation.

Further, Cohen’s effect size value (

d = 0.75) suggested a high practical

significance. Likewise, the effect size of the POGIL approach for applying scores

for the experimental group will be:

The effect size calculated above shows that the percentage

of the POGIL approach for applying scores for the experimental group is 50%. This

percentage indicates that this tool is effective in elevating applying ability among

the students in the experimental group by approximately 0.50 level of standard deviation.

Further, Cohen’s effect size value (d = 0.50) suggested a medium practical

significance.

The effect size of the POGIL approach for reasoning scores for the experimental group will be:

The effect size calculated above shows that the percentage

of the POGIL approach for reasoning scores for the experimental group is

298%. This percentage indicates that this tool effectively elevates reasoning ability among the students in the experimental group by approximately 2.98 level

of standard deviation. Further, Cohen’s effect size value (d = 2.98) suggested

a very high practical significance.

In addition, the effect size of the POGIL approach for

overall KAR scores for the experimental group will be:

The effect size calculated above shows that the percentage

of the POGIL approach for overall KAR scores for the experimental group is 190%.

This percentage indicates that this tool is effective in elevating overall KAR ability

among the students in the experimental group by approximately 1.90 level of standard

deviation. Further, Cohen’s effect size value (

d = 1.90) suggested a high

practical significance (

Figure 3).

The self-efficacy of grade 12 pupils is impacted by POGIL-based instruction instead of lecturing-based instruction.

The students' scores in the self-efficacy survey pretest

were obtained. Then, descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation

were used to compare the student’s performance in the two groups (control and experimental)

regarding physics learning, understanding of physics, Willingness to learn physics,

and the total scores

of Self-Efficacies. The data analysis employed a T-test for an independent sample

to determine if there were statistically significant differences between the mean

scores of the two groups. In contrast, T- a test for related samples, was used to

determine if there were statistically significant differences between the mean scores

of the pre-and post-measured in this study in each domain. The results in

Table 5 display the test scores of Self-efficacy

subscales in the pretest in the control group taught by the lecturing-based instruction

method and the experimental group taught by POGIL-based instruction.

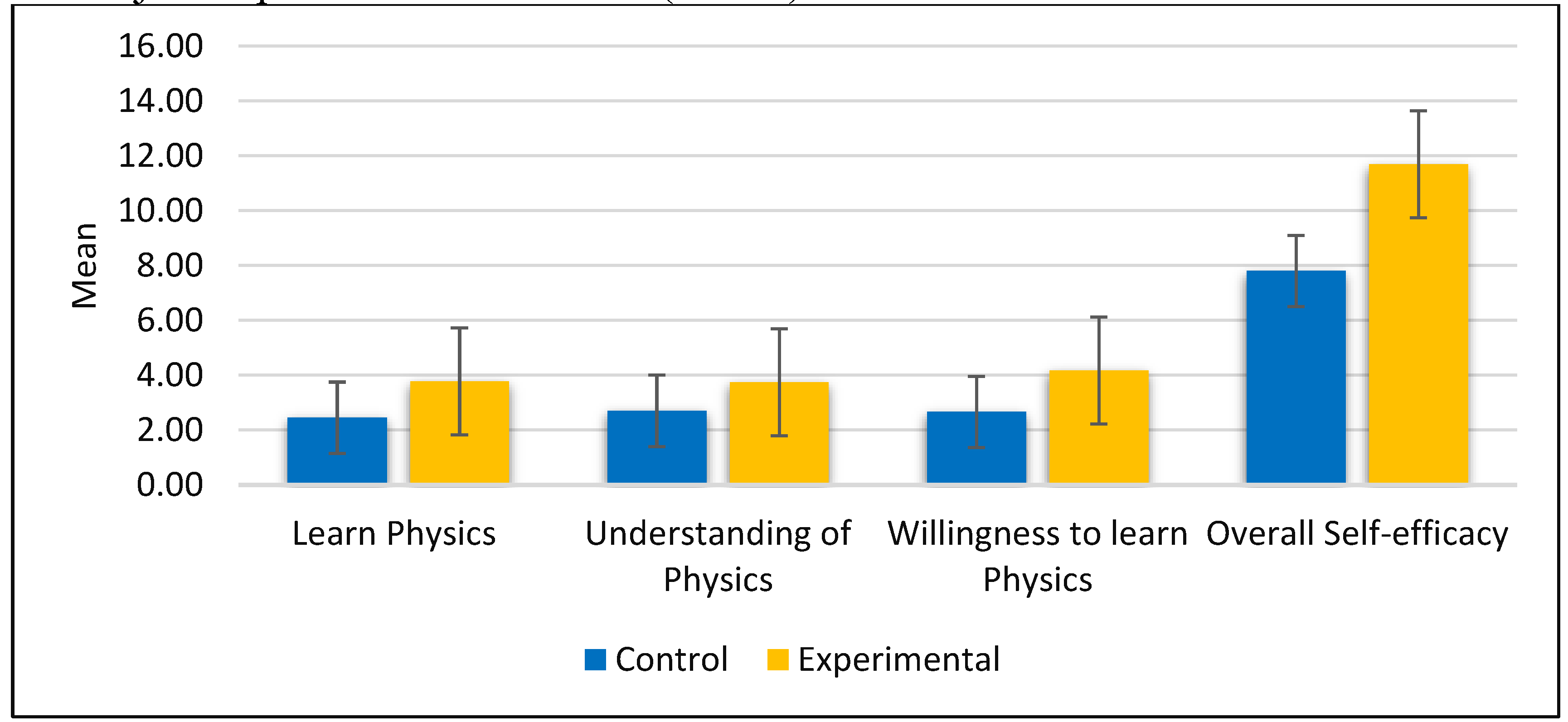

Table 5 and

Figure 4 showed that participants’ performance in

willingness to learn Physics was the highest in both groups (Control group: M =

2.68, SD = 0.61) and (Experimental group: M=2.74, SD =0.59) followed by their Learn

physics abilities (Control group: M = 2.64, SD =0.62) and (Experimental group: M=

2.69, SD =0.54). However, participants’ understanding of Physics abilities reported

the lowest in both groups (Control group: M= 2.57, SD = 0.68) and (Experimental

group: M= 2.70, SD =0.60). In the total scores of the Self-efficacy test, participants

scored higher in the experimental group (M= 8.13, SD =0.99) than in the control

group (M= 7.89, SD = 1.02).

In addition, T-test for independent samples was conducted

to find if there were statistically significant differences between the mean scores

of the pretest measured in this study for the subscales of the Self-Efficacy Survey

for grade 12 students in both control and experimental groups before the intervention.

The results showed that statistically, there were no significant differences between

the control group (M =2.64, SD = 0.62) and experimental group (M = 2.70, SD = 0.54)

regarding students’ performance in learning physics (), which indicated that students’

performance in learning physics in the pretest was the same. Statistically, there

is no significant difference found between the control group (M =2.57, SD = 0.68)

and experimental group (M =2.70, SD =0.60) regarding students’ performance in understanding of Physics (), which indicated that students’

performance in understanding of Physics before the intervention was the same.

Moreover, no statistically significant difference was

shown between the control group (M = 2.68, SD = 0.61) and experimental group (M=

2.74, SD =0.59) regarding students’ performance in willingness to learn Physics

(), which indicated that students’ performance in willingness

to learn Physics before the intervention was the same. Statistically, there is no

significant difference found between the control group (M = 7.89, SD = 1.02) and

experimental group (M = 8.13, SD =0.99) regarding students’ performance in the Self-efficacy test (), which indicated that the students’ Self-efficacy

before the intervention was the same. The same results were obtained after using

the Bonferroni adjusted significance criterion of the p-value 0.05. The adjusted

p-value was = 0.0125 (.05/4) since four tests were conducted.

As presented in

Table 6, for the control group, the participants’ understanding of Physics was

the highest (M = 2.70, SD = 0.63), followed by a willingness to learn Physics (M

= 2.66, SD =0.61). In contrast, participants’ Physics learning reported the lowest

(M= 2.45, SD = 0.63). In the total scores of the Self-efficacy test, participants

scored a mean of 7.80 (SD = 1.07). Results of the T-test for related samples indicated

no significant differences in means of the student’s performance in the control

group in learning physics in the pretest and post-test (

), which indicated that the

performance of the students in the pretest and post-test of learning physics was

the same. Concerning students’ understanding of physic, there was no significant difference

in means of in the control group in the pretest and post-test (

), which indicated that the

performance of the students in the pretest and post-test of understanding of physic

was the same.

Likewise, statistically, no significant difference was

shown in means of the student’s willingness to learn physics in the control group

in the pre and post-test (), which indicated

that the performance of the students in the pretest and post-test of willingness

to learn physics was the same. Overall, no significant difference in means of total

scores of Self-efficacy in the pretest and post-test for the control group (. We can conclude that the student’s performance in

the Self-efficacy survey for the control group was the same before and after the

intervention. The same results were obtained after using the Bonferroni adjusted

significance criterion of the p-value 0.05. The adjusted p-value was = 0.0125

(.05/4) since four tests were conducted.

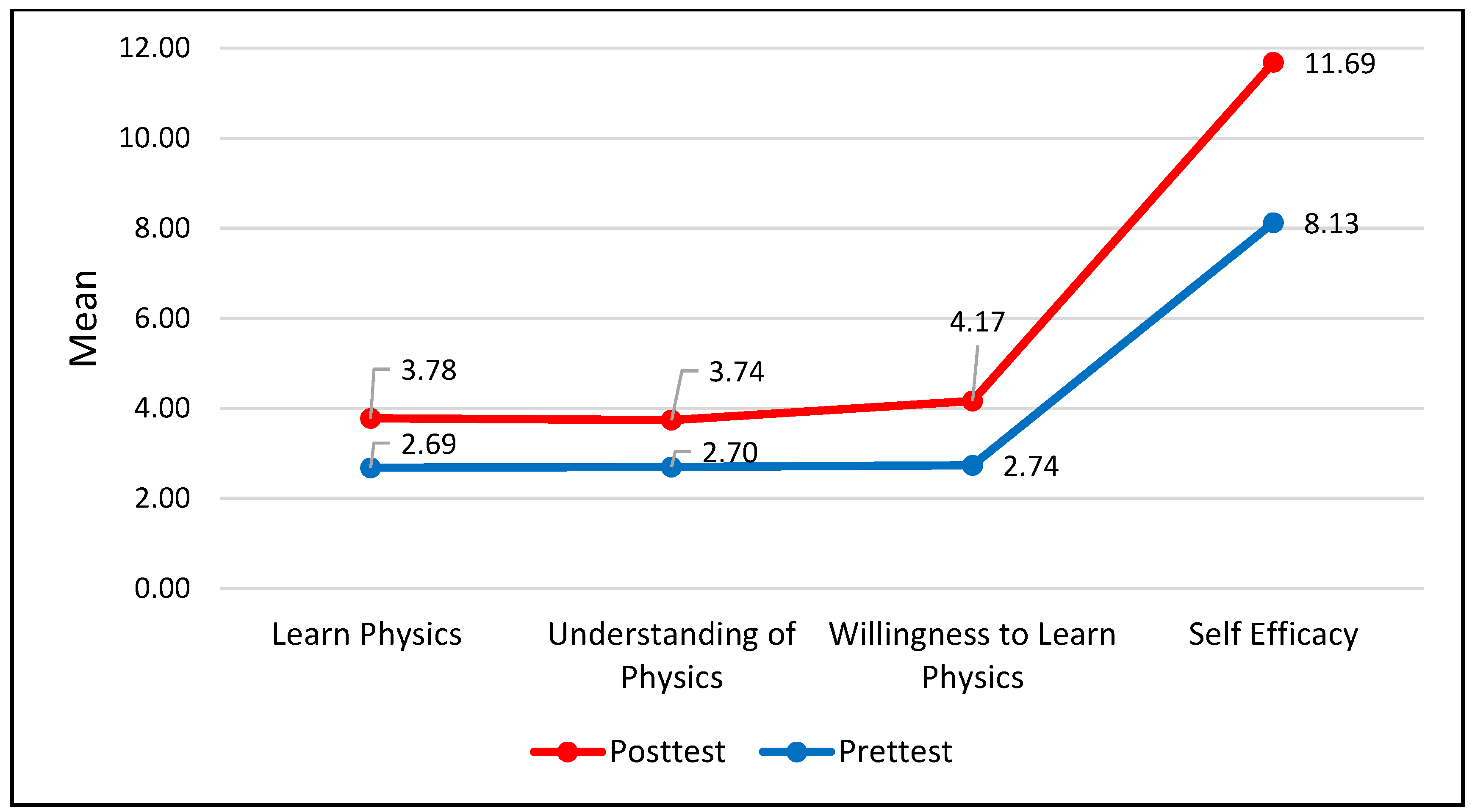

Table 7 shows

that participants’ willingness to learn Physics was the highest in the experimental

group (M = 4.17 and SD = 0.75), then Physics learning came with a mean of 3.78 (SD

= 0.60). At the same time, participants’ understanding of Physics came last with

mean scores of 3.74 (SD = 0.76). Concerning the control group, participants’ understanding

of Physics was the highest (M = 2.70, SD = 0.63). Willingness to learn Physics came

with a mean of 2.66 (SD = 0.61), while participants’ Physics learning came last

with mean scores of 2.45 (SD = 0.63). In the total scores of the Self-efficacy test,

participants scored higher in the experimental group (M= 11.69, SD = 1.24) than

in the control group (M = 7.80, SD = 1.07).

A T-test for independent samples was conducted to find

if there were statistically significant differences between the mean scores of the

post-test measured in this study for students’ Self-efficacy outcomes for students in grade

12 in both control and experimental groups after the intervention. Statistically,

there was a highly significant difference between the control group and experimental

group regarding students’ Physics learning in favour of the experimental group (). Students in the experimental

group were more likely to perform better in Physics learning in the post-test than

in the control group. In addition, statistically,

there was a highly significant difference found between the control group and experimental

group regarding students’ understanding of Physics in favour of the experimental

group (). Students in the experimental

group were more likely to perform better in understanding Physics in the post-test

than in the control group. The results of the T-test

for independent samples showed that statistically, there was a highly significant

difference between the control group and experimental group regarding students’

willingness to learn Physics in favour of the experimental group (). Students in the experimental

group were more likely to have good performance in willingness to learn Physics

in the post-test compared to the control group. Statistically,

there was a highly significant difference found between the control group and experimental

group regarding students’ Self- efficacy as a whole in favour of the experimental

group (). Students in the experimental

group were more likely to have good Self-efficacy in the post-test compared to the

control group. The same results were obtained after using

the Bonferroni adjusted significance criterion of the p-value 0.05. The adjusted

p-value was = 0.0125 (0.05/4) since four tests were conducted.

The results presented in

Table 8 and

Figure 5 display the T-test for related samples of the scores of the domains of

Self- efficacy in the pretest and post-test for the experimental group taught by

POGIL-based instruction. The results indicated that there was a highly significant

difference in means of the scores of learning Physics in favour of post-test

. The mean scores of students’ Physics learning were higher than

that observed in the pretest. Students in the experimental group were likelier to

perform well in Physics learning after the intervention. In addition, there was a highly significant difference in means

of the scores of understanding of Physics in favour of post-test

. The mean scores of students’

understanding of Physics were higher than that observed in the pretest. Students

in the experimental group were more likely to have had good performance in understanding

Physics after the intervention.

Moreover, there was a highly significant difference

in means of the scores of willingness to learn Physics in favour of post-test. The mean scores of students’ willingness to learn

Physics were higher than that observed in the pretest. Students in the experimental

group were more likely to have had good performance in willingness to learn Physics

after the intervention.

Overall, there was a highly significant difference in

means of the scores of the total scores of Self-efficacy in favour of the post-test. The mean scores of students’ self-efficacy were higher

than that observed in the pretest. The same results were obtained after using the

Bonferroni adjusted significance criterion of the p-value 0.05. The adjusted

p-value was = 0.0125 (.05/4) since four tests were conducted.

Thus, students in the experimental group were more likely

to have good Self- efficacy after the intervention (

Figure 5 below). Using

the data presented in

Table 8, the effect

size of the POGIL approach for Physics learning scores for the experimental group

will be:

The effect size calculated above shows that the percentage

of the POGIL approach for Physics learning scores for the experimental group is

140%. This percentage indicates that this tool is effective in elevating Physics

learning ability among the students in the experimental group by approximately 1.40

level of standard deviation. Further, Cohen’s effect size value (

d = 1.40)

suggested a high practical significance. In addition, the effect size of the POGIL

approach for the understanding Physics scores for the experimental group will be:

The effect size calculated above shows that the percentage

of the POGIL approach for understanding Physics scores for the experimental group

is 142%. This percentage indicates that this tool effectively elevates the understanding

of Physics ability among the students in the experimental group by approximately

1.42 level of standard deviation. Further, Cohen’s effect size value (

d =

1.42) suggested a high practical significance. Likewise, the effect size of the

POGIL approach for willingness to learn Physics scores for the experimental group

will be:

The effect size calculated above shows that the percentage

of the POGIL approach for willingness to learn Physics scores for the experimental

group is 146%. This percentage indicates that this tool effectively elevates willingness

to learn Physics ability among the students in the experimental group by approximately

1.43 level of standard deviation. Further, Cohen’s effect size value (

d =1.43)

suggested a high practical significance. Concerning overall students’ self-efficacy, the

effect size of the POGIL approach for Self- efficacy scores for the experimental

group will be:

The effect size calculated above shows that the percentage

of the POGIL approach for Self- efficacy scores for the experimental group are 254%.

This percentage indicates that this tool is effective in elevating Self- efficacy

ability among the students in the experimental group by approximately 2.54 level

of standard deviation. Further, Cohen’s effect size value (

d = 2.54) suggested

a very high practical significance (

Figure 6).

Correlation between student performance and self-efficacy in grade 12 when learning through POGIL versus lecturing

Correlation Analysis

A Pearson’s correlation coefficient was conducted to

determine the correlation between students’ performance in KAR, Self-Efficacy, and

views towards science inquiry amongst 56 participants in the control group. Statistically,

there was no significant correlation between students’ performance in KAR and their

Self-Efficacy (), no significant correlation

between students’ performance in KAR and their views towards science inquiry (), and no significant correlation

between students’ Self-Efficacy and their views towards science inquiry ().

Table 9.

Correlation between Grade 12 Students’ Performance in KAR, Self-Efficacy and Attitudes in Control Group: Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient.

Table 9.

Correlation between Grade 12 Students’ Performance in KAR, Self-Efficacy and Attitudes in Control Group: Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient.

| Scales |

KAR |

Self-Efficacy |

Attitudes |

| KAR |

Correlation Coefficient |

1.000 |

|

|

| P-value |

|

|

|

| n |

56 |

|

|

| Self-Efficacy |

Correlation Coefficient |

0.076 |

1.000 |

|

| P-value |

0.579 |

|

|

| n |

56 |

56 |

|

| Attitudes |

Correlation Coefficient |

0.037 |

0.194 |

1.000 |

| P-value |

0.786 |

0.153 |

|

| n |

56 |

56 |

56 |

Table 10.

Correlation between Grade 12 Students’ Performance in KAR, Self-Efficacy and Attitudes in Experimental Group: Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient.

Table 10.

Correlation between Grade 12 Students’ Performance in KAR, Self-Efficacy and Attitudes in Experimental Group: Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient.

| Scales |

KAR |

Self-Efficacy |

Attitudes |

| KAR |

Correlation Coefficient |

1.000 |

|

|

| P-value |

. |

|

|

| N |

54 |

|

|

| Self-Efficacy |

Correlation Coefficient |

0.704**

|

1.000 |

|

| P-value |

0.000 |

. |

|

| N |

54 |

54 |

|

| Attitudes |

Correlation Coefficient |

0.565**

|

0.569**

|

1.000 |

| P-value |

0.000 |

0.000 |

. |

| N |

54 |

54 |

54 |

A Pearson’s correlation coefficient was conducted to determine the correlation between students’ performance in KAR, Self-Efficacy, and views towards science inquiry amongst 54 participants in the experimental group. Statistically, there was a robust, positive and significant correlation between students’ performance in KAR and their Self-Efficacy () which indicated that as students’ performance in KAR increase, their Self-Efficacy increase.

In addition, there was a strong, positive and significant correlation between students’ performance in KAR and their views towards science inquiry (), which indicated that as students’ performance in KAR increase, their views towards science inquiry more positive.

Moreover, there was a strong, positive and significant correlation between students’ Self-Efficacy and attitudes towards science inquiry (), which indicated that as students’ Self-Efficacy increase, their views towards science inquiry more positive.

Regression Analysis

Multiple Liner Regression was conducted to find the relationship between Grade 12 students’ performance as the dependent variable and self-efficacy and scientific attitudes as independent variables when they learn by POGIL-based instruction and lecturing-based instruction. To this end, the research used SPSS to examine all the relations paths through the resultant path coefficients.

Table 11.

Model Summary: Relationship between Students’ Performance, Self-Efficacy and Attitudes when They Learn by POGIL-Based Instruction.

Table 11.

Model Summary: Relationship between Students’ Performance, Self-Efficacy and Attitudes when They Learn by POGIL-Based Instruction.

| R |

R Square |

Adjusted R Square |

Std. An error in the Estimate |

| 0.732 |

0.536 |

0.513 |

2.053 |

The prediction model contained two predictors: Self-Efficacy and students’ attitudes towards science inquiry, used to predict Students’ performance in KAR. As

Table 12 and

Table 13 showed, the multiple correlations R indicated a positive correlation between the independent and dependent variables (r = 0.732). The model was statistically significant, F (2, 51) = 29.45, p-value < 0.05, and accounted for approximately 51.3% of the variance of students’ attitudes towards science inquiry

.

The raw and standardized regression coefficients of the predictors are shown in

Table 13. The Coefficients table provides the necessary information to predict the dependent variable from the predictors and determine whether the predictors contribute statistically significantly to the model. Self-Efficacy received the most substantial weight in the model. Therefore, Self-Efficacy statistically has a positive effect on student performance since the results indicated that (

. In addition, students’ attitudes towards science inquiry statistically have a positive effect on student's performance since (

. Overall results of the fourth question showed no correlations between the variables: students’ performance and, Self-efficacy and Attitudes when learning by POGIL-based instruction and lecturing instruction before the intervention. On the other hand, there were strong and positive correlations between all variables of the participants’ performance in the KAR Test, participants’ Self-efficacy and their Attitudes towards Scientific Inquiry after the intervention. In addition, the results showed that students’ Self-Efficacy and attitudes towards science inquiry positively affect students’ performance.