A. Introduction

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of zinc dependent endopeptidases that are able to degrade and remodel the extracellular matrix (ECM) by the cleavage of distinct matrix components and also to lead to the proteolytic activation/inactivation of receptors, growth factors, adhesion molecules, cytokines and other pericellular proteins [

1,

2]. Included within the MMPs family are the Membrane-Type Matrix Metalloproteinases (MT-MMPs) which are anchored to the cell membrane either by a type I transmembrane domain (MT1-MMP/MMP-14, MT2-MMP/MMP-15, MT3-MMP/MMP-16, and MT5-MMP/MMP-24) or via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor (MT4-MMP/MMP-17 and MT6-MMP/MMP-25) [

1,

3,

4].

Membrane-type 4 MMP (MT4-MMP, also known as MMP-17) is anchored by a GPI motif to the plasma membrane which confers exclusive mechanisms of biosynthesis and regulation. Apart from this, MT4-MMP conserves the three structural domains characterized in all MMPs: the prodomain, the catalytic, and the hemopexin domains. The prodomain, with a length of 80 amino acids and a consensus sequence with unpaired cysteines, keeps the enzyme in a latent state, named zymogen. The catalytic domain is located at the C-terminal of the prodomain. It has a conserved sequence (“HEXXHXXGXXH”) that includes a Zn2+ ion binding motif which is essential for the proteolytic activity of the proteinase. This is linked by the hinge region to the hemopexin domain involved in substrate recognition and degradation. The stem region downstream of this hemopexin domain is crucial for the establishment of homophilic interactions. Thus, MT4-MMP dimerization through a disulphide bond via the cysteine residues of the stem region, can regulate the amount of MT4-MMP at the cellular surface, as well as increase its stability and enzymatic activity [

3,

5]. Once MT4-MMP is exposed at the cell surface, its enzymatic activity is regulated by endogenous inhibitors, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). There are four mammalian TIMPs (TIMP-1, 2, 3, and 4) that inhibit MT-MMPs by binding their N-terminal domain with the catalytic zinc ion of the enzyme. MT4-MMP is inhibited by all TIMPs, among which TIMP-1 is the most effective inhibitor [

2,

3,

6].

Interestingly, MT4-MMP has unique characteristics compared to other members of the family in terms of sequence homology, substrate specificity, and internalization mode. For instance, its hemopexin domain only displays a 40% similarity with the same domain of the other family members [

7]. This feature may explain the specificity and exclusivity of the substrates to be cleaved by MT4-MMP [

1,

8]. In fact, only a limited number of substrates have been identified for this endopeptidase, including matrix and matricellular proteins such as fibrin/fibrinogen, gelatin [

8], osteopontin [

9], periostin [

10], proteases like ADAMTS-4 [

11,

12], and membrane proteins as αM-integrin [

13], Pro-TNFα [

8] and LRP [

14].

Due to their role in the ECM degradation and the reshape of the pericellular microenvironment, MMP family of proteases contributes to several physiological processes, including embryogenesis, organogenesis, tissue regeneration, angiogenesis, wound healing and also plays a crucial role in distinct pathological processes such as arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and cancer progression [

3]. Expression of MT4-MMP has been reported during angiogenesis, limb development and in distinct brain regions from early embryonic to postnatal stages [

15] as well as in adult tissues such us the brain, ovaries, testis and colon [

7,

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, its physiological role remains unclear.

Regarding its involvement in tumor development, MT4-MMP was first detected in human breast carcinoma [

18] exerting pro-angiogenic and pro-metastatic functions [

20,

21]. In addition, MT4-MMP-mediated cancer dissemination has been described in other types of tumors, including colon, head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSCC) [

22,

23]. Interestingly, its role in cancer progression may be linked to MT4-MMP contribution to stability and permeability of the tumor vasculature [

2,

3]. All this evidence opens the possibility for the use of MT4-MMP as an interesting potential therapeutic target against tumor progression.

B. MT4-MMP Expression and Regulation in Tumors

B.1. Pattern of Expression of MT4-MMP in Normal and Tumor Tissues

Most of MT-MMPs play an important role in physiological conditions. Regarding MT4-MMP, although its role has been reported mainly referring to tumor cell growth [

18,

20,

24], its expression is spatiotemporally controlled during embryonic development. In mice, MT4-MMP is expressed in a dynamic pattern of expression from early to postnatal stages of development with a high expression of this enzyme during vascular and limb development and brain formation [

15]. These data suggest that this metalloproteinase may be associated to novel functions in angiogenesis, endocardial formation, and vascularization during organogenesis as well as in Central Nervous System (CNS) development, which associates with its expression pattern [

15]. In this context, MT4-MMP is essential for the proper organization of the aortic vessel wall. Thus, MT4-MMP expression was confirmed in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) during aortic development where, subsequently, the proteinase contributes to cell differentiation and proliferation through its catalytic activity [

9,

15] (

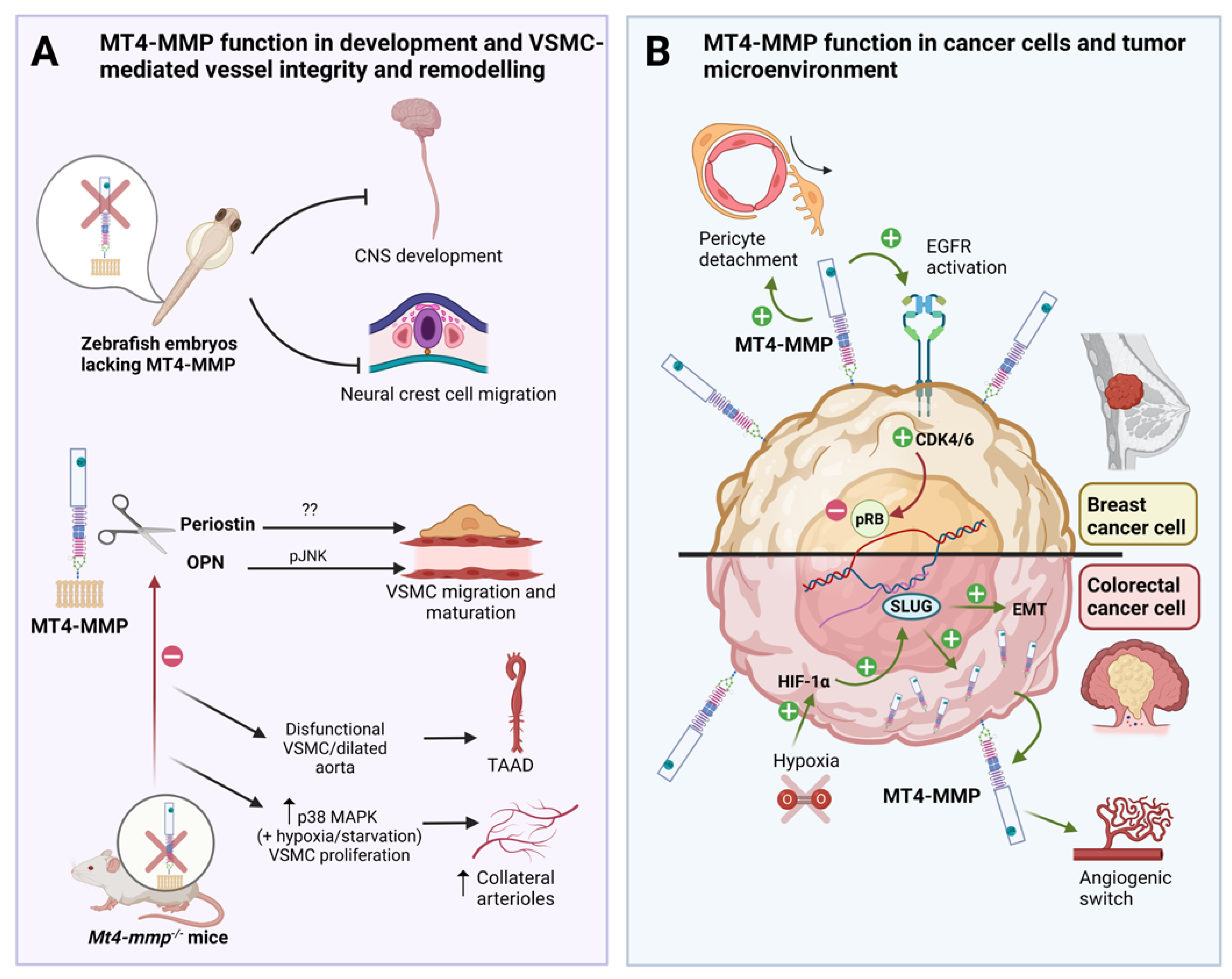

Figure 1A).

During CNS development, the enzyme localizes to certain regions such as the olfactory bulb, cerebral cortex and hippocampus, suggesting a key role in brain development [

15,

17] (

Figure 1A). Interestingly, MT4-MMP knockout mice seem to show no apparent defects in gestation, growth, fertility and behavior, and showed no evident abnormal developmental phenotypes [

16]. Despite of this, MT4-MMP is highly expressed in the kidney papilla and the anterior hypothalamus, and null mice display a decreased intake of water and daily urine output, suggesting a role for this enzyme in water homeostasis and the regulation of the thirst center [

25].

It is also worth noticing that regarding embryonic development, MT4-MMP is essential in neural crest cell (NCC) migration during zebrafish development [

26]. In the mouse embryo, MT4-MMP also appears to be expressed in premigratory and migratory NCCs at early stages of mouse development [

15]. This seems relevant for the regulation of cell migration, as shown in zebrafish, where it is known that its ortholog mmp17b interacts with the MMP inhibitor RECK during NCC development, and it is required for proper NCC migration [

26], in line with the expression previously reported in mouse embryo [

15].

In adult human tissues, MT4-MMP protein was expressed preferentially in different regions of the brain such as the cerebral cortex, the hippocampal formation and the basal ganglia. Also, this metalloproteinase is detected in female tissues (including uterus, cervix and ovary) where it participates in the endometrial angiogenesis during menstrual cycle [

27] and in the gastrointestinal tract, precisely in the colon, under physiological conditions. In fact, cells that express this protein include excitatory neurons, oligodendrocyte precursor cells, inhibitory neurons, smooth muscle cells, melanocytes, and monocytes [

28,

29].

Most of our current information regarding MT4-MMP comes from cancer studies. In fact, the first time MT4-MMP was cloned was from human breast carcinoma cells [

18]. Thereafter, various researchers have confirmed the expression of this proteinase in different tumours such as prostate and oral carcinomas, lung cancer, cervical carcinomas [

30,

31], osteosarcomas, embryonal carcinomas, leukemias [

32], adrenal adenocarcinomas and thyroid tumors [

31]. Also, melanoma and gliomas accumulate a high expression of MT4-MMP likely related to its presence in skin and connective tissues in physiological conditions [

28,

29,

32].

In this context, MT4-MMP has been linked to cancer dissemination. For instance, in vitro studies and subcutaneuous xenografts have confirmed the association between overexpression of MT4-MMP with cell proliferation [

20,

24]. In the same line, high levels expression of MT4-MMP in gastric tissues is associated with lymph node metastasis and serosal involvement, and therefore, with tumor invasion [

33]. In lung metastasis, MT4-MMP alters blood vasculature and induces pericyte detachment, promoting tumoral dissemination [

21]. In contrast, MT4-MMP is downregulated in glioma development. In this sense, as the tumor grade advances, the expression of the proteinase continues decreasing [

34]. Moreover, it is described that MT4-MMP is predominantly expressed by glioma cells, instead of microglia which is the key driver for the tumor cells invasion in the CNS [

35].

Interestingly, MT4-MMP is not only restricted to cancer cells, since positive staining was also observed in nearby cancer stromal cells, supporting their importance in the process of tumor invasion and metastasis. All this evidence opens the possibility for the use of MT4-MMP as an interesting potential therapeutic target against tumor progression.

B.2. Regulation of MT4-MMP expression and activity in normal and tumor tissues

Although it is known that the above mentioned MT4-MMP functions are regulated at various levels, such as gene expression, compartmentalization, pro-enzyme cleavage and substrate processing [

36,

37], little is known about the detailed molecular mechanisms relevant to tissue growth and expansion. However, its proteolytic activity has been shown to be significantly linked to its pro-metastatic activity, and the latter may explain certain aspects of its role in cancer progression (

Figure 1B). For example, unlike most MT-MMPs, MT4-MMP hydrolyses very few ECM components [

1], and it also exhibits characteristic sensitivity to TIMPS as well as inefficient activation of pro-MMP2, which may explain its singular role in promoting tumor progression.

B.2.1. Transcription

It has been reported that MT4-MMP is induced by hypoxia through the hypoxia-inducible factor-1-α (HIF1-α) and the activation of SLUG, a well-known transcription factor involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which promotes the malignant capacity of cancer cells (

Figure 1B) [

22]. Invadopodia formation and amoeboid movements are both crucial mechanisms to promote metastatic dissemination mediated by HIF1-α-induced MT4-MMP expression of tumor cells in HNSCC [

38]. An increase in MT4-MMP has been also observed under hypoxic conditions or under constitutive expression of HIF1-α in other type of tumors such as hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (FADU) and tongue squamous cell carcinoma (SAS) [

22]. Interestingly, SLUG has been identified as the key factor responsible for hypoxia-induced MT4-MMP expression as it can activate the MT4-MMP promoter by interacting with its E-box [

22]. Notably, Slug expression was mostly restricted to migrating neural crest cells and several mesodermal derivatives in the embryo [

39], suggesting that this transcription factor may regulate MT4-MMP expression both during development and tumorigenesis. Therefore, co-expression of MT4-MMP and HIF-1α may be an indicator of breast cancer prognosis. It is also worth noting that in human breast cancer, MT4-MMP transcription is also regulated by the methyltransferase hSED1A, which appears to be over-expressed in these circumstances. It is known that silencing hSED1A decreases MT4-MMP transcription, which impairs cell migration and invasion of tumor cells on lung tissue and colon cancer cells [

40].

B.2.2. Post-Translational Regulation

As a GPI-anchored protein, MT4-MMP is located on lipid domains that seem to be relevant for its activity [

2]. In line with this, the HM-7 cancer cell line expresses MT4-MMP in lipid rafts, while caveolin-1 is not detected. Interestingly, restoration of caveolin-1 expression in metastatic HM-7 cells inhibits MT4-MMP localization to lipid rafts, thereby suppressing the metastatic phenotype of HM-7 colon cancer cells. These findings raise the possibility that MT4-MMP compartmentation may be directly or indirectly involved in certain intracellular signaling events that control its pericellular proteolytic capacity [

23].

The functional cooperation between MT4-MMP and other GPI-proteins such as the urokinase receptor uPAR it may be possible since both can colocalize in the same microdomains [

7]. Although during embryonic development remains elusive, this possible co-expression is relevant to tumor invasion in several cancers [

33]. Indeed, MT4-MMP requires a permissive microenvironment to exert its tumor-promoting effect. Tumor-derived MT4-MMP could not circumvent the absence of a host angio-promoting factor such as the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), a factor that cooperates with the uPA/uPAR axis in different contexts [

41].

Endocytosis is the mechanism that controls the amount of MT4-MMP anchored to the cell surface. On the other hand, the endocytic pathway recycles it back to the cell surface, internalized through the CLIC/GEEC pathway [

42,

43]. The signaling cascade that triggers this pathway involves the Rho family GTPase and Cdc42 and the transcription factors Arf1 or GBF1 that are responsible for the regulation of Cdc42 activity. For instance, MT4-MMP internalization was shown to be primarily dependent on CDC42 and RhoA, and to a lesser extent on Rac1, in MDA-MB-231 cells, a human breast cancer cell line overexpressing the proteinase. These data suggest that MT4-MMP proficiently uses the CLIC/GEEC pathway (rather than the caveolin-dependent or clathrin-dependent pathways) for its internalization [

43]. It should be mentioned that the actin-binding protein Swiprosin-1 (Swip1) functions as a cargo-specific adaptor for CLIC/GEEC endocytic pathway mediating the endocytosis of active integrins, supporting integrin-dependent cancer cell migration and invasion [

44]. As MT4-MMP can also regulate the levels and activity of integrins, particularly β2-integrins, in other cellular contexts [

13], this endocytosis pathway may be particularly relevant for regulating MT4-MMP activity in different cell types and physio-pathological contexts.

A relationship between MT-MMP dimerization and a greater proteolytic activity in tumor cells is feasible [

45,

46]. MT4-MMP is found in homodimers and oligomers at the cell surface maintained via disulfide bond between the cysteine residues of the stem region [

3,

47]. In the context of tumorigenesis, MT4-MMP can form homodimers depending on Cys574 and the formation of disulfide bond between the monomeres both in transfected non-tumor MDCK and COS1 cells and in MD-MB-231 breast carcinoma cells [

43,

47]. Although impairment of dimerization did not decrease cell invasion in vitro, it could still be relevant for other activities in the tumor context.

Shedding is another alternative followed by MT-MMPs to control their pericellular proteolytic activity once they are anchored to the cell membrane [

4,

48]. This mechanism may either involve the release of the extracellular portion of the active MT-MMPs to the cellular milieu or to remove the enzyme from the cell surface. However, the precise mechanism of MT4-MMP shedding remains to be elucidated and it is not fully understood the process by which MT4-MMP regulates the balance between the amount of protein anchored to the membrane by its GPI moiety and the soluble enzyme since it is not affected in the presence of TIMPs [

3,

7]. However, it cannot be ruled out the possibility that this metalloproteinase could be released from the cell surface through the action of a phosphatidylinositol (PI) specific phospholipase C, similarly to membrane dipeptidases [

7].

EGFR has been reported to associate with MT4-MMP by co-immunoprecipitation. Both, EGFR and MT4-MMP have been shown to cooperate in signaling and tumor cell invasion, driving cancer cell growth through the regulation of cell cycle proteins such as CDK4 activation and retinoblastoma protein inactivation (

Figure 1B) [

24]. MT4-MMP is thought to stimulate cell proliferation by interacting with EGFR and enhancing its activation by its ligands, the epidermal growth factor (EGF) and tumor growth factor (TGF) in cancer cells (

Figure 1B). Whether this functional cooperation is also relevant during embryonic development, for example in the heart formation [

49], remains to be investigated.

C. Cellular processes and molecular mechanisms induced by MT4-MMP in cancer progression.

C.1. MT4-MMP tumor cell autonomous actions.

C.1.1. Tumor cell migration and invasiveness.

Studies on mice embryonic development have shed light on the role of Mt4-mmp gene in the physiological EMT process, in which epithelial cells lose polarity and acquire motility during neuronal, brain development and heart morphogenesis [

15,

26,

50]. EMT is a developmental process which induces important changes in the cellular polarity leading to the transition of epithelial cells into mesenchymal cells [

51]. MT-MMPs exert a relevant role during EMT along different species. For instance, catalytic activity of MT1-MMP regulates cadherin levels and promotes the transition and migration of NCCs in Xenopus [

52]. Similarly, the orthologous of MT4-MMP in Zebrafish (mmp17b) is also required for the proper migration of NCC since embryos lacking mmp17b exhibit a defective developmental trunk patterning [

26].

MT4-MMP activity is regulated within spatiotemporal frames in normal tissue, likely to maintain normal physiological function. However, its overexpression in breast cancer cells has led to enhanced lung metastasis and tumor vessel destabilization in xenografts [

20,

21]. In line with these data, immunohistochemical studies revealed an overexpression of MT4-MMP in breast adenocarcinomas [

20], in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) [

24,

53] and in gastric cancer [

33]. Its expression was associated with the depth of tumor invasion, lymph node metastasis, serosal involvement and transperitoneal spread of gastric cancer cells [

33]. MT4-MMP dependent cancer cell migration and invasion in vitro has been attributed to its dimerization through cysteine residues [

47]. Its specific cell surface localization in lipid rafts has been associated with a dynamic towards a migratory phenotype of colon cancer cells [

31]. While MT4-MMP was inefficient in promoting breast cancer cell migration and invasion in vitro and in 2D Matrix [

20], it promotes metastasis in vivo. More recently, Yan et al., reported that MT4-MMP expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC) increases invadopodia formation and gelatin degradation [

38]. Mechanistically, the authors show that MT4-MMP binding with Tks5 and PDGFRα results in Src activation and promotes amoeboid-like movement by stimulating the small GTPases Rho and Cdc42. Together, these data support the hypothesis that MT4-MMP induces, in a cell-dependent manner, crucial mechanisms of cancer migration and invasion, the key element of cancer metastasis. Further investigations are still needed to determine mechanisms driven by MT4-MMP in cell migration and in which context it can modify cell-ECM interaction and control cell adhesion and invasion.

C.1.2. Tumor cell proliferation and growth.

Several proteinases can control the bioavailability and activity of growth factors and regulate cell proliferation. Mechanistically, MMPs release active molecules from the ECM, shed cell surface receptors and process growth factor binding proteins through their proteolytic activity, which lead to angiogenesis and tumor growth [

37,

54,

55]. For instance, MT1-MMP modulates tyrosine kinase receptors (TKR) such as, receptor of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGFR) and Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGFR2), while MMP9 and MMP2 activate Transforming Growth Factor-beta and release Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) sequestered into the ECM [

55,

56]. Opposing to the well-known MT1-MMP-mediated outside-in cell signaling, the signaling role of GPI anchored MT4-MMPs in promoting cancer cell proliferation was unknown. A direct contribution of MT4-MMP to tumor growth has been demonstrated by analyzing of the proliferation index (Ki67 positivity) of MT4-MMP xenografts compared to control tumors [

24]. In this study, MT4-MMP was demonstrated to promote cancer cell proliferation only in 3D culture and through the activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) after its binding to ligands. MT4-MMP was validated as a key signaling precursor and partner of EGFR, which enhances its activation leading to cancer cell proliferation in a non-proteolytic manner. In contrast to its intrinsic non-proteolytic effect on EGFR activation and cell proliferation in 3D Matrigel, the enzymatic activity of MT4-MMP was still required for the early angiogenic switch during breast cancer progression [

41]. Breast cancer xenografts with inert form of MT4-MMP (E249A) were not able to induce early angiogenesis and have reduced growth potential when compared to xenografts producing the active form of the enzyme. Interestingly, MT4-MMP has been recently identified as a biomarker for TNBC patient responses to chemotherapy [

57] and to the combination of EGFR inhibitor, Erlotinib and Palbociclib, an inhibitor of Cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6, which are involved in the cell cycle [

53]. These data highlight the proliferative effect of MT4-MMP that is dependent on EGFR signaling and the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor pathway (RB pathway) in TNBC (

Figure 1B). Furthermore, they shed a new light on the putative interest of MT4-MMP to predict the response of patient to some chemotherapies and targeted treatments.

C.2. MT4-MMP tumor cell autonomous actions.

One of the most important issues in tumor cell resistance and recurrence is the microenvironmental changes that occur during tumorigenesis [

58]. This involves pericellular ECM transformation by distinct types of cells including fibroblasts, neuroendocrine and immune cells as well as changes in the blood vessels and the lymphatic network to orchestrate the precise conditions for tumor development [

59].

C.2.1. Alteration of the vasculature architecture.

Given that MT-MMPs can release growth factor sequestered in ECM or cell surface associated growth factors, they can shape tumor blood vessels in the tumor microenvironment [

37,

60]. One of the most important roles of MMPs in vessel maturation and stability has been attributed to MT1-MMP in several studies reported on knockout mice and in models of tissue injury [

60]. MT1-MMP regulates vessel stability through the increase of TGFb availability and signaling through ALK5 in blood vessels [

60]. In tumor angiogenesis, pericytes take an important role in stabilizing the newly form microvessels being recruited around the endothelial cell sprouts to form larger perfused microvessels [

60,

61]. In fact, in well-established xenografts of breast carcinoma, MT4-MMP in tumor cells promotes paracrine pericyte detachment from tumor vessels, allowing thereby cancer cell escape and intravasation into blood vessels and leading to metastatic spread [

20,

21,

60]. Notably, MT4-MMP expressed by tumor cells was also found essential in promoting an early angiogenic switch and tumor blood vessel formation that has been shown to be dependent on its catalytic function. In Matrigel plug assays using cancer cells expressing the inert form of the enzyme, tumor fails in recruiting new endothelial cells and in inducing tumor vascularization when compared to tumor expressing the active form of the enzyme [

41]. The MT4-MMP substrates for this pericyte/angiogenic effect in tumors are not yet known. Nevertheless, osteopontin proteolysis and JNK signaling that has been reported to be driven by MT4-MMP during vascular smooth muscle cell (VSCM) migration in the aorta vessel wall [

9], might be relevant in the tumor vascular context. Thus, MT4-MMP function in vascular wall is evident as it is expressed in periaortic progenitors during embryogenesis, suggesting a role in early formation of the aortic wall and VSMC maturation [

9,

15]. MT4-MMP knockout mice have dysfunctional VSMCs and dilated aortas [

9] and displayed adventitial fibrosis and hypotension, like mouse models of thoracic aortic aneurisms and dissections (TAAD) (

Figure 1A) [

62]. Recently, periostin has been identified as a novel substrate for SMCs in the stem cell niche of the intestine [

10] with actions in intestinal homeostasis and repair. Whether MT4-MMP-periostin axis plays a role in tumor cell development and progression deserves further investigation. More recently, the absence of MT4-MMP has been shown to promote proliferation in vascular smooth muscle cells and the formation of collateral arterioles by induction of p38 MAPK signaling and mitochondria dynamics particularly in contexts of hypoxia or starvation (

Figure 1A) [

63]. The relevance of this pathway in tumors presenting heterogeneous hypoxia might be an interesting aspect to investigate.

C.2.2. MT4-MMP and the tumor immune response.

MT4-MMP has been involved not only in angiogenesis but is also associated with inflammatory pathologies such as osteoarthritis and atherosclerosis. Both, angiogenesis and inflammation, are two crucial processes for tumor development. For instance, MT4-MMP levels are elevated inside immune system tissues such as metastatic lymph nodes [

20] and in leukocytes [

64].

During the inflammatory process, cytokine production by immune cells is linked to cancer in multiples ways although information about the contribution of MT4-MMP to the tumor immune response is very limited [

65]. MT4-MMP can be produced by immune cells promoting angiogenesis and retaining chemotactic molecules to attract them to the tumor neighborhood. Thus, MT4-MMP can activate proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α which is expressed in T-cells and macrophages. MT4-MMP-mediated cleavage of pro-TNF-α in isolated macrophages in vitro can trigger their activation [

66]. On the contrary, Rikimaru et al., described that in Mt4-mmp-/- mice the release of TNF-α from macrophages after LPS injection was like that in wild type animals and that the expression of MT4-MMP mRNA was repressed [

16]. Interestingly, many tumors produce abundant TNF-α that promote cancer cell survival through the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway [

67]. Therefore, it would be interesting to evaluate the involvement of MT4-MMP in this pathway through the cleavage and availability of active TNF-α in tumoral cells.

A permissive host microenvironment during cancer progression is necessary not only for endothelial cells but also for the distinct immune cell types. In this sense, Host et al. demonstrated that MT4-MMP functions as a key intrinsic tumor cell determinant that contributes to the elaboration of a permissive microenvironment for metastatic dissemination [

41].

MT4-MMP is also expressed in tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [

58]. In peritumoral and tumoral samples of hepatocellular carcinoma, MT4-MMP-positive cells colocalized with macrophages expressing M2 phenotypic markers, while is absent in tumor cells, fibroblasts or M1 macrophages [

58]. In addition, MT4-MMP-positive TAMs reduced, in a paracrine manner, E-cadherin expression in favor of mesenchymal N-cadherin and vimentin in hepatocellular carcinoma cells which is characteristic of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) necessary for tumor metastasis [

58].

MT4-MMP has also been shown to regulate the crawling and recruitment of a subset of circulating monocytes, patrolling monocytes, to inflamed endothelial sites by cleaving the αMβ2 integrin adhesion receptor [

13]. While these patrolling monocytes contribute to combat circulating tumor cells in the lung [

68], they can also differentiate into pro-angiogenic tumor associated macrophages once they transmigrate to the tissue [

69]. Therefore, the possible contribution that MT4-MMP regulation of patrolling monocyte behavior may have on lung metastasis remains to be explored.

D. MT4-MMP as a Biomarker and Therapeutic Target in Cancer Growth

The implication of MT4-MMP in cancer progression is related to its capacity to regulate intrinsic tumor cell proliferation and tumor blood vessel destabilization phenomenon. These two roles can potentiate its tumor and metastatic effects, making it an excellent target. Future studies aiming at targeting these two functions will further define its relevance in cancer and diseases. Nevertheless, the pro-proliferative effect of MT4-MMP on breast cancer cells in vitro has been inhibited by erlotininb and the presence of MT4-MMP in tumors was shown to be associated with more sensitivity to chemotherapy [

57]. Furthermore, MT4-MMP/EGFR/RB axis has been used to define a subtype of TNBC that can effectively respond to erlotinib and palbociclib combination therapy [

53]. The clinical relevance of MT4-MMP, its new partner EGFR and RB has been validated in human TNBC samples and in patient-derived xenografts of TNBC (PDX-TNBC) [

2]. TNBC response to erlotinib and palbociclib was evaluated in vitro, in vivo, in xenografts and PDX models of TNBC and demonstrated that MT4-MMP/EGFR/RB axis is highly relevant in 50% of TNBC. PDX of this TNBC subtype showed a complete inhibition of tumor growth upon combined erlotinib and Palbociclib treatment. Together, this useful data on MT4-MMP/EGFR/RB association and therapy combination yields clinically relevant insights and provides potentially useful biomarkers to identify TNBC subtypes that respond to specific therapeutic combinations. Given the high prevalence of TNBC producing MT4-MMP and EGFR, combination of EGFR inhibitor with MT4-MMP inhibitor might improve TNBC treatments. However, targeting MMPs in cancer has been proven difficult since the disappointing clinical trials reported 20 years ago [

73]. The adequate task of targeting this enzyme should consider its partners such as EGFR, JNK signaling and molecular heterogeneity of breast cancers. In the era of personalized medicine, homogeneous procedures for MT4-MMP expression assessment could help in defining the right patient who could respond to anti-EGFR targeted therapy. While genomic profiling did not reveal a particular interest for MT4-MMP, immunohistochemistry studies have demonstrated its overexpression in breast cancers, suggesting a possible alternative splicing in MT4-MMP transcripts in human cancers. Another consideration is to check for MT4-MMP partners that enhance cancer cell and stroma cells migration and malignancy. In this field, a particular attention should be given on the generation of function blocking molecules of MT4-MMP and exploring their combination with EGFR in breast cancer.

E. Conclusions

Taken together, these data emphasize the relevance of MT4-MMP in the context of cancer. Although there are many ways by which MT4-MMP participates in tumor progression, the mechanisms used by this proteinase for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and vessel stability in tumors seem to recapitulate those described during embryonic development. However, further investigations are essential to improve our knowledge about the function of MT4-MMP in the embryo as well as in physiological and pathological conditions including cancer progression. This will help us to develop new therapeutic approaches and to improve the design of new selective MT4-MMP inhibitors to achieve faster diagnosis and more personalized treatment for cancer patients and for vascular diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, CSC, NES, AGA, AN, EMS; software, NMP, EMS; writing—original draft preparation, CSC, NES, AGA, AN, EMS, NMP, AIR, AC; writing—review and editing, CSC, NES, AGA, AN, EMS; supervision, NES, CSC; project administration, CSC, NES, AGA, AN, EMS; funding acquisition, CSC, NES, AGA, AN, EMS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad Europea de Madrid 2022/UEM07 (EMS, CSC), the National Fund for Scientific Research (FRS-FNRS), Belgium: PDR # T.023020 (NES) and the project PID2020-112981RB-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (AGA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the financial support of Télevie-FNRS; The Fondation contre le Cancer (Foundation of Public Interest, Belgium), the Fonds spéciaux de la Recherche (University of Liège), the Centre Anticancéreux près l'Université de Liège, the Fonds Léon Fredericq (University of Liège).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Moracho N, Learte AIR, Muñoz-Sáez E, Marchena MA, Cid MA, Arroyo AG, et al. Emerging roles of MT-MMPs in embryonic development. Dev Dyn. 2022, 251, 240–275.

- Yip C, Foidart P, Noel A, Sounni NE, Noël A, Sounni NE. MT4-MMP: The GPI-anchored membrane-type matrix metalloprotease with multiple functions in diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sohail A, Sun Q, Zhao H, Bernardo MM, Cho J-A, Fridman R. MT4-(MMP17) and MT6-MMP (MMP25), a unique set of membrane-anchored matrix metalloproteinases: properties and expression in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008, 27, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh Y. Membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases: Their functions and regulations. Matrix Biol. 2015;44–46:207–23.

- Gifford V, Itoh Y. MT1-MMP-dependent cell migration: Proteolytic and non-proteolytic mechanisms. Biochem Soc Trans. 2019, 47, 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Johnson AR, Ye QZ, Dyer RD. Catalytic activities and substrate specificity of the human membrane type 4 matrix metalloproteinase catalytic domain. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274, 33043–33049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh Y, Kajita M, Kinoh H, Mori H, Okada A, Seiki M. Membrane type 4 matrix metalloproteinase (MT4-MMP, MMP-17) is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteinase. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274, 34260–34266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English WR, Puente XS, Freije JM, Knauper V, Amour A, Merryweather A, et al. Membrane type 4 matrix metalloproteinase (MMP17) has tumor necrosis factor-alpha convertase activity but does not activate pro-MMP2. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275, 14046–14055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Alonso M, Garcia-Redondo AB, Guo D, Camafeita E, Martinez F, Alfranca AA, et al. Deficiency of MMP17/MT4-MMP proteolytic activity predisposes to aortic aneurysm in mice. Circ Res. 2015, 117, e13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Alonso M, Iqbal S, Vornewald PM, Lindholm HT, Damen MJ, Martínez F, et al. Smooth muscle-specific MMP17 (MT4-MMP) regulates the intestinal stem cell niche and regeneration after damage. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao G, Westling J, Thompson VP, Howell TD, Gottschall PE, Sandy JD. Activation of the proteolytic activity of ADAMTS4 (aggrecanase-1) by C-terminal truncation. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277, 11034–11041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao G, Plaas A, Thompson VP, Jin S, Zuo F, Sandy JD. ADAMTS4 (aggrecanase-1) activation on the cell surface involves C-terminal cleavage by glycosylphosphatidyl inositol-anchored membrane type 4-matrix metalloproteinase and binding of the activated proteinase to chondroitin sulfate and heparan sulfate on s. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279, 10042–10051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente C, Rius C, Alonso-Herranz L, Martin-Alonso M, Pollan A, Camafeita E, et al. MT4-MMP deficiency increases patrolling monocyte recruitment to early lesions and accelerates atherosclerosis. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanov D V, Hahn-Dantona E, Strickland DK, Strongin AY. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein LRP is regulated by membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) proteolysis in malignant cells. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279, 4260–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco MJ, Rodriguez-Martin I, Learte AIR, Clemente C, Montalvo MG, Seiki M, et al. Developmental expression of membrane type 4-matrix metalloproteinase (Mt4-mmp/Mmp17) in the mouse embryo. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0184767. [Google Scholar]

- Rikimaru A, Komori K, Sakamoto T, Ichise H, Yoshida N, Yana I, et al. Establishment of an MT4-MMP-deficient mouse strain representing an efficient tracking system for MT4-MMP/MMP-17 expression in vivo using beta-galactosidase. Genes Cells. 2007, 12, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funatsu N, Inoue T, Nakamura S. Gene expression analysis of the late embryonic mouse cerebral cortex using DNA microarray: identification of several region- and layer-specific genes. Cereb Cortex. 2004, 14, 1031–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente XS, Pendás AM, Llano E, Velasco G, López-Otín C. Molecular cloning of a novel membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase from a human breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 944–949. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal R, Patel AP, Debs LH, Nguyen D, Patel K, Grati M, et al. Intricate Functions of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. J Cell Physiol. 2016, 231, 2599–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabottaux V, Sounni NE, Pennington CJ, English WR, van den Brûle F, Blacher S, et al. Membrane-type 4 matrix metalloproteinase promotes breast cancer growth and metastases. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 5165–5172.

- Chabottaux V, Ricaud S, Host L, Blacher S, Paye A, Thiry M, et al. Membrane-type 4 matrix metalloproteinase (MT4-MMP) induces lung metastasis by alteration of primary breast tumour vascular architecture. J Cell Mol Med. 2009, 13, 4002–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang C-H, Yang W-H, Chang S-Y, Tai S-K, Tzeng C-H, Kao J-Y, et al. Regulation of membrane-type 4 matrix metalloproteinase by SLUG contributes to hypoxia-mediated metastasis. Neoplasia. 2009, 11, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimri L, Barak H, Graeve L, Schwartz B. Restoration of caveolin-1 expression suppresses growth, membrane-type-4 metalloproteinase expression and metastasis-associated activities in colon cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2013, 52, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paye A, Truong A, Yip C, Cimino J, Blacher S, Munaut C, et al. EGFR activation and signaling in cancer cells are enhanced by the membrane-bound metalloprotease MT4-MMP. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 6758–6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srichai MB, Colleta H, Gewin L, Matrisian L, Abel TW, Koshikawa N, et al. Membrane-type 4 matrix metalloproteinase (MT4-MMP) modulates water homeostasis in mice. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e17099. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh NR, Schupp M-O, Li K, Padmanabhan V, Gastonguay A, Wang L, et al. Mmp17b is essential for proper neural crest cell migration in vivo. Klymkowsky M, editor. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e76484. [Google Scholar]

- Plaisier M, Koolwijk P, Hanemaaijer R, Verwey RA, van der Weiden RMF, Risse EKJ, et al. Membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases and vascularization in human endometrium during the menstrual cycle. Mol Hum Reprod. 2006, 12, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human Protein Atlas [Internet]. Available from: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000198598-MMP17.

- Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015, 347, 1260419.

- Riddick ACP, Shukla CJ, Pennington CJ, Bass R, Nuttall RK, Hogan A, et al. Identification of degradome components associated with prostate cancer progression by expression analysis of human prostatic tissues. Br J Cancer. 2005, 92, 2171–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant GM, Giambernardi TA, Grant AM, Klebe RJ. Overview of expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-17, MMP-18, and MMP-20) in cultured human cells. Matrix Biol. 1999, 18, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieronimus B, Pfohl J, Busch C, Graeve L. Expression and characterization of membrane-type 4 matrix metalloproteinase (MT4-MMP) and its different forms in melanoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017, 42, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Yu S-J, Li Y-X, Luo H-S. Expression and clinical significance of matrix metalloproteinase-17 and -25 in gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2015, 9, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttall RK, Pennington CJ, Taplin J, Wheal A, Yong VW, Forsyth PA, et al. Elevated membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases in gliomas revealed by profiling proteases and inhibitors in human cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2003, 1, 333–345. [Google Scholar]

- Thome I, Lacle R, Voß A, Bortolussi G, Pantazis G, Schmidt A, et al. Neoplastic cells are the major source of MT-MMPs in IDH1-mutant glioma, thus enhancing tumor-cell intrinsic brain infiltration. Cancers. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Parks WC, Wilson CL, López-Boado YS. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004, 4, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2010, 141, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan X, Cao N, Chen Y, Lan HY, Cha JH, Yang WH, et al. MT4-MMP promotes invadopodia formation and cell motility in FaDu head and neck cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020, 522, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savagner P, Karavanova I, Perantoni A, Thiery JP, Yamada KM. Slug mRNA is expressed by specific mesodermal derivatives during rodent organogenesis. Dev Dyn. 1998, 213, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salz T, Li G, Kaye F, Zhou L, Qiu Y, Huang S. hSETD1A regulates Wnt target genes and controls tumor growth of colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Host L, Paye A, Detry B, Blacher S, Munaut C, Foidart JM, et al. The proteolytic activity of MT4-MMP is required for its pro-angiogenic and pro-metastatic promoting effects. Int J cancer. 2012, 131, 1537–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayor S, Pagano RE. Pathways of clathrin-independent endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong A, Yip C, Paye A, Blacher S, Munaut C, Deroanne C, et al. Dynamics of internalization and recycling of the prometastatic membrane type 4 matrix metalloproteinase (MT4-MMP) in breast cancer cells. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 704–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Layseca P, Jäntti NZ, Godbole R, Sommer C, Jacquemet G, Al-Akhrass H, et al. Cargo-specific recruitment in clathrin- and dynamin-independent endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genís L, Gálvez BG, Gonzalo P, Arroyo AG. MT1-MMP: Universal or particular player in angiogenesis? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006, 25, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez H, López-Martín S, Toribio V, Zamai M, Hernández-Riquer MV, Genís L, et al. Regulation of MT1-MMP activity through its association with ERMs. Cells. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Sohail A, Marco M, Zhao H, Shi Q, Merriman S, Mobashery S, et al. Characterization of the dimerization interface of membrane type 4 (MT4)-matrix metalloproteinase. J Biol Chem. 2011, 286, 33178–33189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osenkowski P, Toth M, Fridman R. Processing, shedding, and endocytosis of membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP). J Cell Physiol. 2004, 200, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamoto R, Mekada E. ErbB and HB-EGF signaling in heart development and function. Cell Struct Funct. 2006, 31, 1–14.

- Nakaya Y, Sheng G. EMT in developmental morphogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2013, 341, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RYJ, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009, 139, 871–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garmon T, Wittling M, Nie S. MMP14 regulates cranial neural crest epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and migration. Dev Dyn. 2018, 247, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foidart P, Yip C, Radermacher J, Blacher S, Lienard M, Montero-Ruiz L, et al. Expression of MT4-MMP, EGFR, and RB in triple-negative breast cancer strongly sensitizes tumors to Erlotinib and Palbociclib combination therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 1838–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sounni NE, Dehne K, van Kempen L, Egeblad M, Affara NI, Cuevas I, et al. Stromal regulation of vessel stability by MMP14 and TGFbeta. Dis Model Mech. 2010, 3, 317–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sounni NE, Noel A. Targeting the tumor microenvironment for cancer therapy. Clin Chem. 2013, 59, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sounni NE, Noel A. Membrane type-matrix metalloproteinases and tumor progression. Biochimie. 2005, 87, 329–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip C, Foidart P, Somja J, Truong A, Lienard M, Feyereisen E, et al. MT4-MMP and EGFR expression levels are key biomarkers for breast cancer patient response to chemotherapy and erlotinib. Br J Cancer. 2017, 116, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi F, Li J, Guo M, Yang B, Xia J. MT4-MMP in tumor-associated macrophages is linked to hepatocellular carcinoma aggressiveness and recurrence. Clinical and translational medicine. 2020, 10, e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintero-Fabián S, Arreola R, Becerril-Villanueva E, Torres-Romero JC, Arana-Argáez V, Lara-Riegos J, et al. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in angiogenesis and cancer. Front Oncol. 2019, 9, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sounni NE, Paye A, Host L, Noel A. MT-MMPS as regulators of vessel stability associated with angiogenesis. Front Pharmacol. 2011, 2, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Raza A, Franklin MJ, Dudek AZ. Pericytes and vessel maturation during tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Am J Hematol. 2010, 85, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li W, Li Q, Jiao Y, Qin L, Ali R, Zhou J, et al. Tgfbr2 disruption in postnatal smooth muscle impairs aortic wall homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2014, 124, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahún-Español Á, Clemente C, Jiménez-Loygorri JI, Sierra-Filardi E, Herrera-Melle L, Gómez-Durán A, et al. p38 MAPK priming boosts VSMC proliferation and arteriogenesis by promoting PGC1α-dependent mitochondrial dynamics. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier M-C, Racine C, Ferland C, Flamand N, Chakir J, Tremblay GM, et al. Expression of membrane type-4 matrix metalloproteinase (metalloproteinase-17) by human eosinophils. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003, 35, 1667–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin W-W, Karin M. A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007, 117, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manicone AM, McGuire JK. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008, 19, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo J-L, Maeda S, Hsu L-C, Yagita H, Karin M. Inhibition of NF-kappaB in cancer cells converts inflammation- induced tumor growth mediated by TNFalpha to TRAIL-mediated tumor regression. Cancer Cell. 2004, 6, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna RN, Cekic C, Sag D, Tacke R, Thomas GD, Nowyhed H, et al. Patrolling monocytes control tumor metastasis to the lung. Science. 2015, 350, 985–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidibe A, Ropraz P, Jemelin S, Emre Y, Poittevin M, Pocard M, et al. Angiogenic factor-driven inflammation promotes extravasation of human proangiogenic monocytes to tumours. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizki A, Weaver VM, Lee S-Y, Rozenberg GI, Chin K, Myers CA, et al. A human breast cell model of preinvasive to invasive transition. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 1378–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salz T, Deng C, Pampo C, Siemann D, Qiu Y, Brown K, et al. Histone methyltransferase hSETD1A is a novel regulator of metastasis in breast cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2015, 13, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajita M, Kinoh H, Ito N, Takamura A, Itoh Y, Okada A, et al. Human membrane type-4 matrix metalloproteinase (MT4-MMP) is encoded by a novel major transcript: isolation of complementary DNA clones for human and mouse mt4-mmp transcripts. FEBS Lett. 1999, 457, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingleton, B. MMPs as therapeutic targets--still a viable option? Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008, 19, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).