Submitted:

20 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Digital Literacy

Digital Culture

- “Person-centered, led by individuals’ needs rather than technologies or other external drivers;

- Purposeful and values-led, clearly related to organizational missions; and

- Nuanced and contextualized – helping people understand and relate skills to their own practice and setting.” [19]

Global Digital Citizen

A Perspectives Approach

2. Open Foundations

4. Knowledge Co-Creation

“Museums help us negotiate the complex world around us; they are safe and trusted spaces for exploring challenging and difficult ideas” ([53], p. 4).

5. Digital Inclusiveness

6. Amplifying Global Digital Citizenship through Participatory Innovation

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borda, A.; Bowen, J. P. Turing’s Sunflowers: Public research and the role of museums. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2020: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 16–20 November 2020; Weinel, J., Bowen, J. P., Diprose, G., Lambert, N., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2020; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 32–39. [CrossRef]

- Digital Citizen Initiative. UNESCO. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/creativity/policy-monitoring-platform/digital-citizen-initiative (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Hamayel, H. J.; Hawamdeh, M. M. Methods Used in Digital Citizenship: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Digital Educational Technology. 2022, 2(3), ep2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital citizen. Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_citizen (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Mossberger, K.; Tolbert, C. J.; McNeal, R. S. Digital Citizenship: The Internet, Society, and Participation; The MIT Press, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Jones, L. M.; Mitchell, K. J. Defining and measuring youth digital citizenship. New Media & Society 2016, 18(9), 1817–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negroponte, N. Being Digital; Hodder & Stoughton, 1995.

- Gilster, P. Digital Literacy; John Wiley: New York, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Berners-Lee, T. Weaving the Web; Orion Business Books, 1999.

- Ribble, M.; Bailey, G. Digital Citizenship in Schools; ISTE: Washington, DC, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Borda, A.; Bowen, J. The Rise of Digital Citizenship and the Participatory Museum. In Proceedings of EVA London 2021: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts, London, UK, 5–9 July 2021; Weinel, J., Bowen, J. P., Borda, A., Diprose, G., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2022; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 20–27. [CrossRef]

- Ribble, M. Digital Citizenship: Using technology appropriately, 2017. Available online: https://www.digitalcitizenship.net (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Ribble, M. Digital Citizenship in Schools: Nine Elements All Students Should Know, 3rd edition; International Society for Technology in Education, 2017.

- Rogers-Whitehead, C. Digital Citizenship in Schools: Teaching Strategies and Practice from the Field. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2019.

- Choi, M.; Cristol, D. Digital citizenship with intersectionality lens: Towards participatory democracy driven digital citizenship education. Theory Into Practice 2021, 60(4), 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, E.; Simsek, A. New Literacies for Digital Citizenship. Contemporary Educational Technology. 2013, 4(2), 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurbanoğlu, S.; Špiranec, S.; Grassian, E.; Mizrachi, D.; Catts, R., Eds. Information Literacy: Lifelong Learning and Digital Citizenship in the 21st Century. Communications in Computer and Information Science, volume 492. Springer, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Milic, N. Digitalising the Museum. In Handbook of Research on Museum Management in the Digital Era; Bifulco, F., Tregua, M., Eds.; Hershey, PA, Information Science Reference, 2022. pp. 138–154.

- Malde, S.; Kennedy, A.; Parry, R. Understanding the digital skills & literacies of UK museum people: Phase Two Report. University of Leicester, UK, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Gilbertson, M.; Craft, M.; Potter, T. Planetary grand challenges: a call for interdisciplinary partnerships. Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies 2019, 6(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, L. C.; Yemini, M. Internationalization in public education, equity and hope for future citizenship. In Humanist futures: Perspectives from UNESCO Chairs and UNITWIN Networks on the futures of education; Paris, UNESCO, 2020.

- Global citizenship education: Topics and learning objectives. UNESCO, 2015. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000233240 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Watanabe-Crockett, L. What is a Global Digital Citizen and Why Does the World Need Them? Medium, 12 January 2017. Available online: https://medium.com/future-focused-learning/what-is-a-global-digital-citizen-and-why-does-the-world-need-them-8b94ace7803 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Allan, S.; Thorsen, E., Eds. Citizen Journalism: Global Perspectives. Peter Lang Publishing, 2009.

- Irwin, A. Citizen Science: A study of people, expertise and sustainable development. London, Routledge, 1995.

- Hecker, S.; Haklay, M.; Bowser, A.; Makuch, Z.; Vogel, J.; Bonn, A., Eds. Citizen Science: Innovation in Open Science, Society and Policy. London, UCL Press, 2018.

- Harrison, R.; Sterling, C. Reimagining Museums for Climate Action. London, Museums for Climate Action, 2021. Available online: https://www.museumsforclimateaction.org/mobilise/book (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Neuman, W. L. Social Research Methods Qualitative and Quantitative Approach, 8th edition. Pearson, 2021.

- Neilson, T.; Levenberg, L.; Rheams, D. Introduction: Research Methods for the Digital Humanities. In Research Methods for the Digital Humanities; Levenberg, L., Neilson, T.; Rheams, D., Eds.; Cham, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Sonkoly, G.; Vahtikari, T. Innovation in Cultural Heritage: For an Integrated European research policy. Working Paper. European Commission, Publications Office, Luxembourg, 2018. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/1dd62bd1-2216-11e8-ac73-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Virtual Library museums pages. Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtual_Library_museums_pages (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Gaia, G.; Boiano, S.; Bowen, J. P.; Borda, A. Museum websites of the first wave: The rise of the virtual museum. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2020: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 16–20 November 2020; Weinel, J., Bowen, J. P., Diprose, G., Lambert, N., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2020; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 24–31. [CrossRef]

- Liu, A. H.-Y.; Bowen, J. P. Creating online collaborative environments for museums: A case study of a museum wiki. International Journal of Web Based Communities 2011, 7(4), 407–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagle, J.; Koerner, J., Eds. Wikipedia @ 20. The MIT Press, 2020.

- Bowen, J. P.; Angus, J. Museums and Wikipedia. In MW2006: Museums and the Web; Albuquerque, Archives & Museum Informatics, 2006. Available online: https://www.archimuse.com/mw2006/papers/bowen/bowen.html (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- LaPorte, S.; Ayers, P. Common Interests: Libraries, the Knowledge Commons, and Public Policy. I/S: A Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Society 2016, 13(1), 295–316. Available online: https://kb.osu.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/67b4f68d-b945-56b3-92fd-9eb821672f19/content (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Bowen, J. P.; Fan, H. The Chengdu Biennale and Wikipedia Art Information. In Proceedings of EVA London 2022: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts, London, UK, 4–8 July 2022; Bowen, J. P., Weinel, J., Borda, A., Diprose, G., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2022; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 111–118. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J. Digital Commons as a Model for Digital Sovereignty: The Case of Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the Weizenbaum Conference 2022: Practicing Sovereignty, Interventions for Open Digital Futures; Herlo, B., Irrgang, D., Eds.; 2023. Weizenbaum Institute. pp. 162–170. [CrossRef]

- Dorman, D. Open Source Software and the Intellectual Commons. American Libraries 2002, 33(11), 51–54, December. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25648551 (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Powell, A. Democratizing production through open source knowledge: from open software to open hardware. Media, Culture & Society 2012, 34(6), 691–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, R.; Walsh, J. Open Knowledge: Promises and Challenges. In The Digital Public Domain: Foundations for an Open Culture, 1st edition; de Rosnay, M. D., De Martin, J. C., Eds.; Volume 2, pp. 125–132. Open Book Publishers, 2012. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vjsx3.13 (accessed on 28 December 2024).

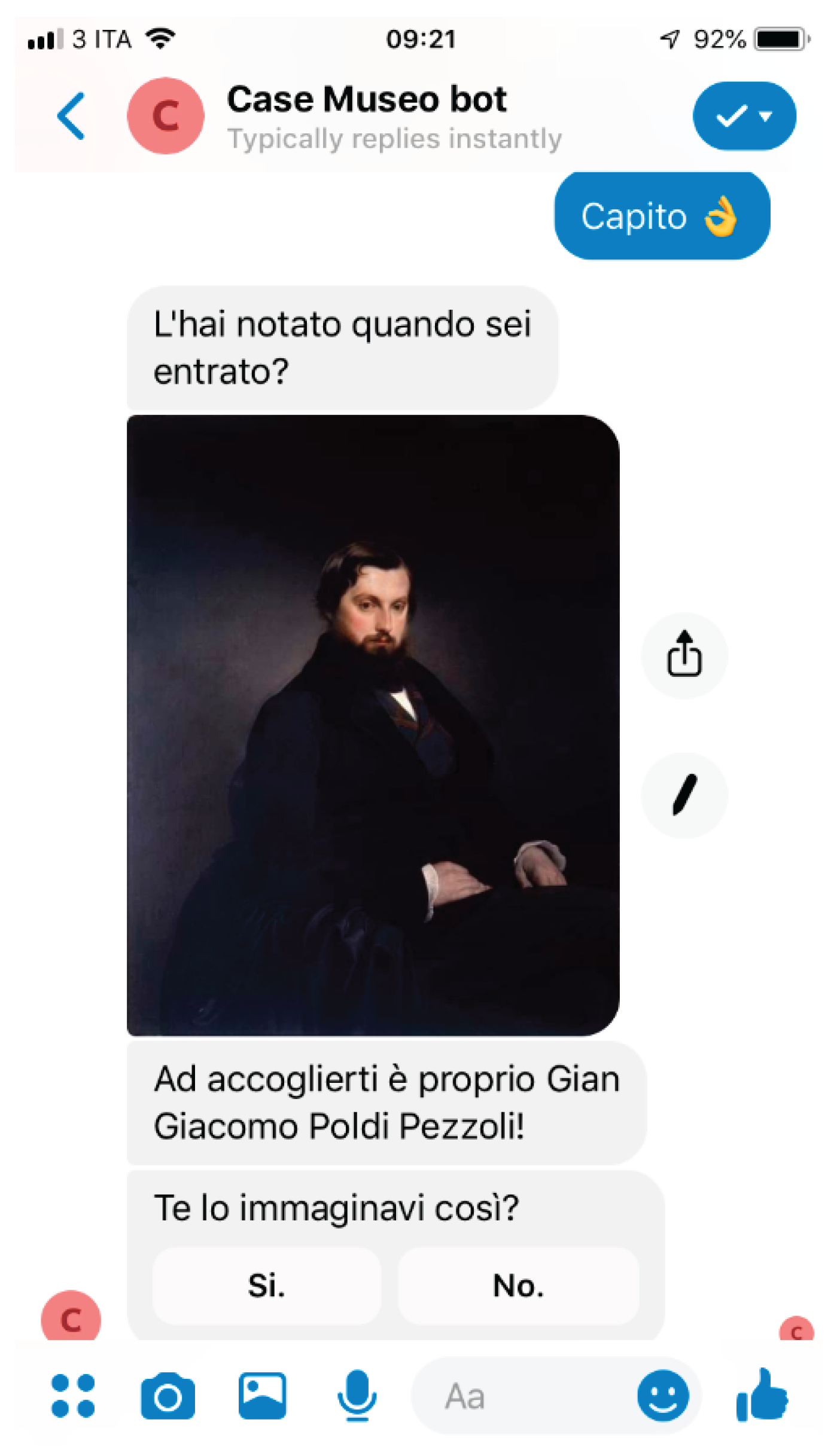

- Gaia, G.; Boiano, S.; Borda, A. Engaging Museum Visitors with AI: The Case of Chatbots. In Museums and Digital Culture: New Perspectives and Research; Giannini, T., Bowen, J. P. Eds.; chapter 15, pp. 301–329; Cham, Springer, Series on Cultural Computing, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Jones-Garmil, K. Ed. The Wired Museum: Emerging Technology and Changing Paradigms. American Association of Museums, 1997.

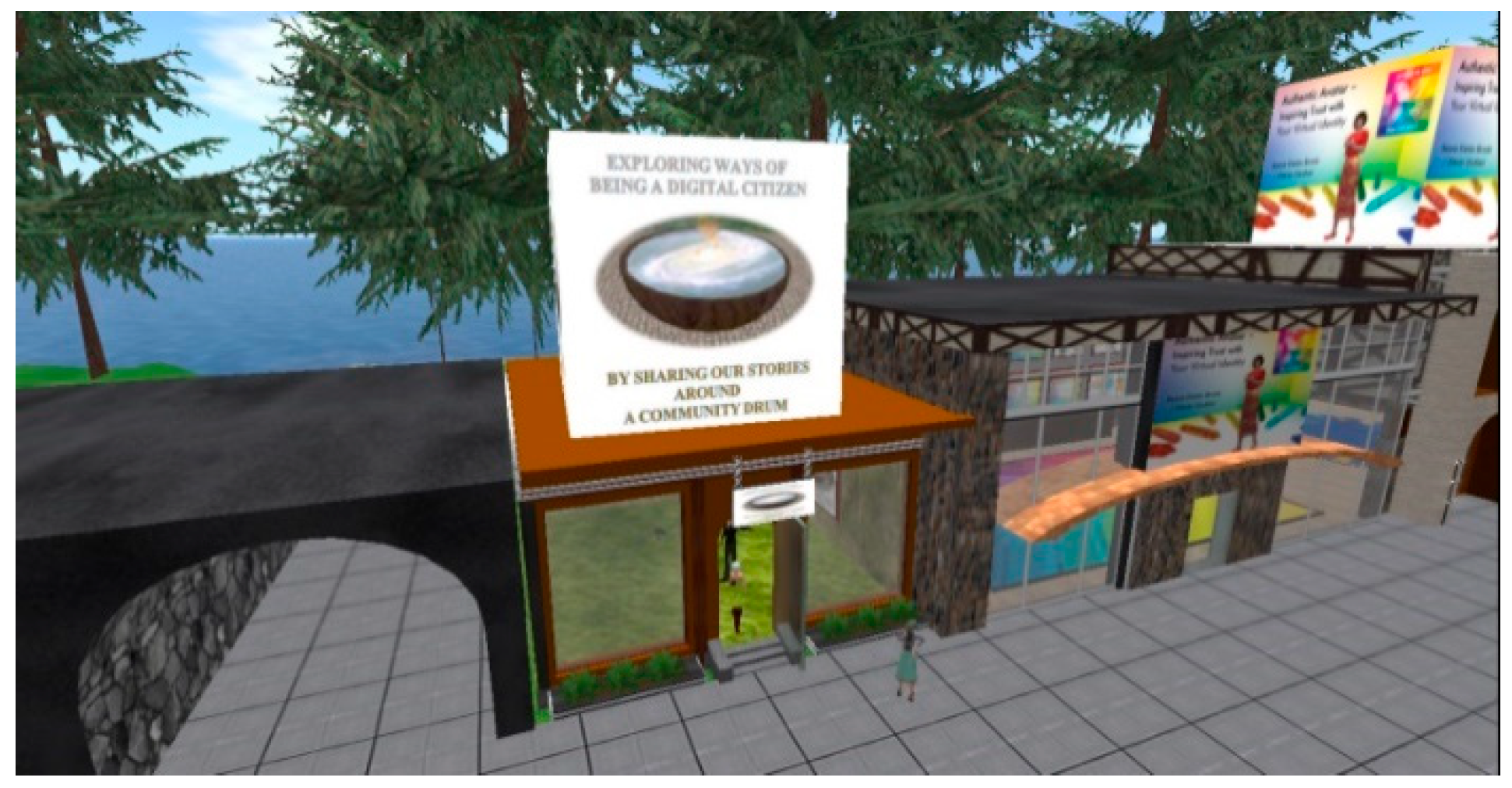

- Digital Citizenship Museum. Community Virtual Library. Available online: https://communityvirtuallibrary.org/digital-citizenship-museum (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Beler, A.; Borda, A.; Bowen, J. P.; Filippini-Fantoni, S. The building of online communities: An approach for learning organizations, with a particular focus on the museum sector. In EVA 2004 London Conference Proceedings, University College London, UK; Hemsley, J., Cappellini, V., Stanke, G., Eds.; pp. 2.1–2.15, 2004. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/cs/0409055 (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Wenger, E.; McDermott, R. A.; Snyder, W. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge. Harvard Business School Press, 2002.

- Schellenbacher, J. Museums, activism and social media (or, how Twitter challenges and changes museum practice). In Museum Activism, Janes, R. R., Sandell, R., Eds. Routledge, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Smithsonian Open Access. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., USA. Available online: https://www.si.edu/openaccess (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Simon, N. The Participatory Museum, 2010. Available online: http://www.participatorymuseum.org (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Mutibwa, D. H.; Hess, A.; Jackson, T. Strokes of serendipity: Community co-curation and engagement with digital heritage. Convergence 2020, 26(1), 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, J. From Social Media to the Social Museum. Nordic Center of Heritage Learning. The Nordic Centre of Heritage Learning and Creativity, Östersund, Sweden, 2013. Available online: http://nckultur.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/From_Social_Media_to_a_Social_Museum_Jasper_Visser.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Museums Taskforce Report and Recommendations. Museums Association, London, UK, 2018. Available online: https://ma-production.ams3.digitaloceanspaces.com/app/uploads/2020/08/17073208/Museums-Taskforce-Report-and-Recommendations.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Mortati, M.; Magistretti, S.; Cautela, C.; Dell’Era, C. Data in design: How big data and thick data inform design thinking projects. Technovation 2023, 122, 102688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L. Museums as Sources of Information and Learning. Open Museum Journal 2006, 8. Australian Museum. Available online: https://publications.australian.museum/museums-as-sources-of-information-and-learning/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- McKenzie, B. The Possible Museum: Anticipating Future Scenarios. In Addressing the Challenges in Communicating Climate Change Across Various Audiences; Leal Filho, W., Lackner, B., McGhie, H., Eds.; pp 443–456. Springer, Cham, Climate Change Management, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Duester, E. Digital Museums in the Global South: A Framework for Sustainable and Culturally Appropriate Digital Transformation. Routledge, 2025.

- Zooniverse. People-Powered Research, Zooniverse. Available online: http://www.zooniverse.org (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Zooniverse. World Architecture Unlocked, Zooniverse. Available online: https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/courtaulddigital/world-architecture-unlocked (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Hedges, M.; Dunn, S. Academic Crowdsourcing in the Humanities: Crowds, communities, and co-production. Cambridge, MA, Elsevier Science, 2017.

- Ridge, M., Ed. Crowdsourcing our Cultural Heritage. London, Ashgate, 2024.

- Afanador-Llach, M. J.; Lombana-Bermudez, A. Developing New Literacy Skills and Digital Scholarship Infrastructures in the Global South: A Case Study. In Global Debates in the Digital Humanities, Ricaurte, P.; Chaudhuri, S.; Fiormonte, D., Eds., chapter 17, pp. 225–238. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2022. Available online: https://muse.jhu.edu/book/100081 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Constantinidis, D. Crowdsourcing Culture: Challenges to Change. In Cultural Heritage in a Changing World, Borowiecki, K., Forbes, N., Fresa, A., Eds., chapter 13, pp. 215–234. Cham, Springer, 2016. [CrossRef]

- OECD. Digital Transformation and the Futures of Civic Space to 2030, OECD Development Policy Paper 29. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 10 June 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/digital-transformation-and-the-futures-of-civic-space-to-2030_79b34d37-en.html (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Tseng, Y.-S. Rethinking gamified democracy as frictional: a comparative examination of the Decide Madrid and vTaiwan platforms. Social & Cultural Geography, 2022; 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangerfield, M. B. Power to the People: The rise and rise of Citizen Journalism. Tate, UK, 2015. Available online: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/photojournalism/power-people (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Citizen Journalism: Sign of the Times. The Autry Museum, Los Angeles, USA, 2018. Available online: https://theautry.org/citizen-journalism (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Hodges, A. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York, Simon and Schuster, 1983.

- Black, S.; Bowen, J. P.; Griffin, K. Can Twitter Save Bletchley Park? In MW 2010: Museums and the Web Conference, Denver, Colorado, USA; Archives & Museum Informatics, 2010. Available online: https://www.museumsandtheweb.com/biblio/can_twitter_save_bletchley_park.html (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Black, S.; Colgan, S. Saving Bletchley Park. London, Unbound, 2015.

- Carter, J. Museums and justice. Museum Management and Curatorship 2019, 34(6), 541–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilenschneider, C. People Trust Museums More Than Newspapers. ColleenDilenschneider, 26 April 2017. Available online: https://www.colleendilen.com/2017/04/26/people-trust-museums-more-than-newspapers-here-is-why-that-matters-right-now-data/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Dilenschneider, C. More People Trust Museums Now Than Before the Pandemic (DATA). ColleenDilenschneider, 1 March 2023. Available online: https://www.colleendilen.com/2023/03/01/more-people-trust-museums-now-than-before-the-pandemic-data/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Mundt, M.; Ross, K.; Burnett, C. M. (2018). Scaling Social Movements Through Social Media: The Case of Black Lives Matter. Social Media + Society 2018, 4(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Díaz, A.; Fernández-Prados, J. S. Young digital citizenship in #FridaysForFuture. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies 2022, 44(5), 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, T. Contested Space: Activism and Protest. In Museums and Digital Culture: New Perspectives and Research; Giannini, T., Bowen, J. P. Eds.; chapter 5, pp. 91–111; Cham, Springer, Series on Cultural Computing, 2019. [CrossRef]

- #DayOfFacts – Museums and cultural/scientific institutions reminding the public that facts matter. DayOfFacts, WordPress, 17 February 2017. Available online: https://dayoffacts.wordpress.com (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Miller, P. A new mission for museums: Report calls for institutions to help battle ‘fake news’. The Herald, 5 March 2018. Available online: https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/16064183.new-mission-museums-report-calls-institutions-help-battle-fake-news/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Johnson, H. Adorno and climate science denial: Lies that sound like truth. Philosophy & Social Criticism 2020, 47(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, F. R.; Neilson, B., Eds. Climate Change and Museum Futures. London, Routledge, 2015.

- Adorno, F. Stronger Than the Storm: Museums in the Age of Climate Change. Western Museums Association (WMA), USA. Available online: https://westmuse.org/articles/stronger-storm-museums-age-climate-change (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Barnes, P.; McPherson, G. Co-Creating, Co-producing and Connecting: Museum Practice Today. Curator: The Museum Journal 2019, 62(2), 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, A.; Bridson, K.; Parris, M. A. The muse with a wandering eye: the influence of public value on coproduction in museums. International Journal of Cultural Policy 2018, 26(3), 344–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L. Engaging Museum Visitors in Difficult Topics Through Socio-cultural Learning and Narrative. In Hot Topics, Public Culture, Museums; Cameron, F., Kelly, L., Eds.; pp. 194–210. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010. http://www.c-s-p.org/flyers/Hot-Topics--Public-Culture--Museums1-4438-1974-3.htm (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Kelly, L. The Connected Museum in the World of Social Media. In Museum Communication and Social Media: The connected museum; Drotner, K., Schroder, K., Eds.; pp. 54–71. London, Routledge, 2013.

- Beazley, I.; Bowen, J. P.; Liu, A. H.-Y.; McDaid, S. Dulwich OnView: An art museum-based virtual community generated by the local community. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2010: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 5–7 July 2010; Seal, A., Bowen, J. P., Ng, K., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2010; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 79–86. [CrossRef]

- Warschauer, M. Technology and Social Inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide. Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Bonacchi, C.; Bevan, A.; Keinan-Schoonbaert, A.; Pett, D.; Wexler, J. Participation in heritage crowdsourcing. Museum Management and Curatorship 2019, 34(2), 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janes, R. R. The Mindful Museum. Curator: The Museum Journal 2010, 53(3), 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, S. Audience Development and Cultural Policy, p. 234. London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2021.

- Black, G. Meeting the audience challenge in the ‘Age of Participation’. Museum Management and Curatorship 2018, 33(4), 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filip, F. G.; Ciurea, C.; Dragomirescu, H.; Ivan, I. Cultural heritage and modern information and communication technologies. Technological and Economic Development of Economy 2015, 21(3), 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahne, J.; Hodgin, E.; Eidman-Aadahl, E. (2016). Redesigning civic education for the digital age: Participatory politics and the pursuit of democratic engagement. Theory & Research in Social Education 2016, 44(1), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disinfodemic: Deciphering COVID-19 disinformation. UNESCO, 2020. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374416 (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- UNESCO Report: Museums around the world in the face of COVID-19. UNESCO, 2020. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373530 (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Holcombe-James, I. COVID-19, digital inclusion, and the Australian cultural sector: A research snapshot. Digital Ethnography Research Centre, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A. aking Part focus on: Diversity Trends, 2005/06 to 2015/16. Department for Culture, Media & Sport, UK Government, 26 April 2017. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a82301ee5274a2e8ab57f50/Diversity_focus_report.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- UK Government. Guidance: Participation Survey. Department for Culture, Media and Sport & Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, UK Government, 26 August 2021. (Last updated 29 February 2024.). Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/participation-survey (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Mandel, B. R. Can Audience Development Promote Social Diversity in German Public Art Institutions? The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 2019, 49(2), 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, R.; Bunting, H.; Scott, R.; Sobolewska, M. Degrees of Separation: The education divide in British politics. The Social Mart Foundation (SMF), United Kingdom, November 2023. Available online: https://www.smf.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Degrees-of-separation-November-2023.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- OECD. Bridging the Digital Gender Divide: Include, Upskill, Innovate. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2018. Available online: https://eulacfoundation.org/system/files/digital_library/2023-07/bridging-the-digital-gender-divide.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Bridging digital divides in G20 countries. G20 Infrastructure Working Group, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 20 December 2021. [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Meier, J.; Sylvester, A.; Goulding, A. Indigenous Digital Inclusion: Interconnections and Comparisons. In ALISE 2020 Proceedings. The Association for Library and Information Science Education (ALISE), pp. 301–316, October 2020. Available online: https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/items/116456 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- First Nations Technology Council Co-Creating Strategy to Achieve Digital Equity for Indigenous Peoples. First Nations Technology Council, Canada, 3 November 2021. Available online: https://www.technologycouncil.ca/news/first-nations-technology-council-co-creating-strategy-to-achieve-digital-equity-for-indigenous-peoples/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- First Nations Digital Inclusion Advisory Group. First Nations Digital Inclusion Roadmap: 2026 and beyond. Commonwealth of Australia, December 2024. Available online: https://www.digitalinclusion.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/first-nations-digital-inclusion-roadmap-2026-and-beyond.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Dirksen, A. Decolonizing Digital Spaces. In Citizenship in a Connected Canada: A Research and Policy Agenda; Dubois, E.; Martin-Bariteau, F., Eds.; Ottawa, ON, University of Ottawa Press, 2020. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3620493 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Shoenberger, E. What does it mean to decolonize a museum? Museum Next, 23 February 2022. Available online: https://www.museumnext.com/article/what-does-it-mean-to-decolonize-a-museum/ (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Cooper, C. B.; Rasmussen, L. M.; Jones, E. D. Data Ethics in the Participatory Sciences Toolkit. Citizen Science Association, 2022. Available online: https://www.citizenscience.org/data-ethics (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Hintz, A.; Dencik, L.; Wahl-Jorgensen, K. Digital Citizenship in a Datafied Society. Polity, 2018.

- Chesbrough, H. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Harvard Business Review Press, 2003.

- Eid, H. Museum Innovation and Social Entrepreneurship: A New Model for a Challenging Era. Routledge, 2019.

- Povroznik, N. (2024). Museums’ digital identity: Key components. Internet Histories 2024, 8(1–2), 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiano, S.; Borda, A.; Gaia, G. Participatory Innovation and Prototyping in the Cultural Sector: A case study. In Proceedings of EVA London 2019: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts, London, UK, 8–12 July 2019; Weinel, J., Bowen, J. P., Diprose, G., Lambert, N., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2019; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 18–26. [CrossRef]

- Ceccaroni, L., et al. Advancing the productivity of science with citizen science and artificial intelligence. In Artificial Intelligence in Science: Challenges, Opportunities and the Future of Research. OECD Publishing, Paris, 26 June 2023. [CrossRef]

- Boiano, S.; Borda, A.; Gaia, G.; Di Fraia, G. Ethical AI and Museums: Challenges and new directions. In Proceedings of EVA London 2024: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts, London, UK, 8–12 July 2024; Bowen, J. P., Weinel, J., Borda, A., Diprose, G., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2024; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 18–25. [CrossRef]

- Merritt, E. Chatting About Museums with ChatGPT. American Alliance of Museums, 25 January 2023. Available online: https://www.aam-us.org/2023/01/25/chatting-about-museums-with-chatgpt/ (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Droitcour, B. The Year in Review: Museums Are Leaving AI Hype Behind. Frieze, 10 December 2024. Available online: https://www.frieze.com/article/year-review-ai-art-2024 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Holly Herndon & Mat Dryhurst: The Call. Serpentine Gallery, 2024. Available online: https://www.serpentinegalleries.org/whats-on/holly-herndon-mat-dryhurst-the-call/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Richardson, J. (2024) Can ChatGPT replace a curator. MuseumNext, 11 September 2024. Available online: https://www.museumnext.com/article/when-algorithms-curate-art-the-nasher-museums-ai-experiment/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- AI4LAM: Artificial Intelligence for Libraries, Archives & Museums. Available online: https://sites.google.com/view/ai4lam (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Charr, M. Museums in the Metaverse: Exploring the Future of Cultural Experiences. MuseumNext, 25 June 2024. Available online: https://www.museumnext.com/article/museums-in-the-metaverse-exploring-the-future-of-cultural-experiences/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Bowen, J. P. The Metaverse and Expo 2020: VR. AR, MR, and XR. In The Arts and Computational Culture: Real and Virtual Worlds; Giannini, T., Bowen, J. P., Eds.; Springer Series on Cultural Computing, 2024. Chapter 12, pp. 299–317. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. This chart shows how big the metaverse market could become. World Economic Forum, 7 February 2023. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/02/chart-metaverse-market-growth-digital-economy (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Barba, B.; Mat, V. L.-A.; Gomez, A.; Pirovich, J. Discussion Paper: First Nations' Culture in the Metaverse. SSRN, Elsevier, 18 April 2022. [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Yuxweluptun, L. P. Unceded Territories. Paisley Smith. Available online: https://www.paisleysmith.com/unceded-territories-vr (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Borda, A. Bearing Witness: A commentary on climate action and immersive climate change exhibitions. In Proceedings of EVA London 2023: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts, London, UK, 10–14 July 2023; Bowen, J. P., Weinel, J., Diprose, G., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2023; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 15–22. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, O.; Villaespesa, E. AI: A Museum Planning Toolkit. Goldsmiths, University of London, January 2020. Available online: https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/28201/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Goodyear, M. P. Who Is Responsible for AI Copyright Infringement? Issues in Science and Technology 2024, 41(1), 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikow, R. B.; DiPietro, C.; Trizna, M. G.; et al. Developing responsible AI practices at the Smithsonian Institution. Research Ideas and Outcomes 2023, 9, e113334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, N. ChatGPT: A Case Study on Copyright Challenges for Generative AI Systems. European Journal of Risk Regulation 2023, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeepSeek-AI. DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv:2501.12948v1 [cs.CL], 22 January 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2501.12948 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Nuffield Foundation. Participatory data stewardship: A framework for involving people in the use of data. Ada Lovelace Institute, 7 September 2021. Available online: https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/participatory-data-stewardship/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Domínguez Hernández, A.; Krishna, S.; Perini, A. M.; et al. Mapping the individual, social and biospheric impacts of Foundation Models. In FAccT’24: Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, pp. 776–796. ACM, June 2024. [CrossRef]

- Benjamins, R.; Rubio Viñuela, Y.; Alonso, C. Social and ethical challenges of the metaverse. AI Ethics 2023, 3, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarini, L. The Digital Citizen(ship): Politics and Democracy in the Networked Society. ElgarOnline, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Santana, L. E.; Trauthig, I.; Woolley, S. We Can Harness Digital Citizenship to Confront AI Risks. Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), 26 September 2024. Available online: https://www.cigionline.org/articles/we-can-harness-digital-citizenship-to-confront-ai-risks/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- UNESCO Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), United Nations, 23 November 2021. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/UNESCO.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Godinho, M. A.; Borda, A.; Kostkova, P.; et al. Knowledge co-creation in participatory policy and practice: Building community through data-driven direct democracy. Big Data & Society 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).