1. Introduction

Glycerol, a trihydric alcohol, is employed as a heat transfer fluid [

1], representing a non-toxic alternative to widely used ethylene glycol [

2]. Furthermore, glycerol finds its application in flow-based biosensors as a component of specialized buffer solutions [

3]. The above-mentioned applications suppose the organization of a fluid flow.

Regarding biosensor systems, biological macromolecules under study are either introduced directly into the flow, or immobilized on the sensor surface, which is in direct physical contact with the fluid flow [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. In this situation, the fluid flow is directly interacting with the biological macromolecules. In this regard, with the example of bovine serum albumin (BSA), Dobson et al. demonstrated that direct action of a fluid flow can induce protein aggregation [

8].

In this regard, one should bear in mind that the flow of both aqueous and non-aqueous fluids can well cause triboelectric generation of electric charge [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Electromagnetic fields induced in this way were also shown to affect biological macromolecules [

15,

16,

17], exhibiting an indirect action of a fluid flow on these macromolecules.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) allows for studying aggregation of biological macromolecules with single-molecule resolution [

22]. Previously, we reported the successful use of AFM for revelation of enzyme aggregation under the influence of flow-induced electromagnetic fields [

15,

16,

17].

Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) represents a ~44 kDa [

23] enzyme glycoprotein, whose structure is stabilized by carbohydrate chains [

24,

25]. Since this enzyme is comprehensively characterized in literature [

26], many authors used it as a model object for studying the effect of electric [

27], magnetic [

28,

29,

30,

31] and electromagnetic [

15,

16,

17,

22,

32,

33,

34,

35] fields on enzymes.

Herein, we have employed the well-established approach based on AFM and spectrophotometry [

15,

17,

22] for studying the effect of glycerol flow in a shielded coil on HRP. While AFM has allowed us to reveal an increase in the aggregation of HRP on the surface of mica substrates, a slight increase in its enzymatic activity against its substrate 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate) (ABTS) in solution has also been observed.

The data reported can be of interest for scientists studying the interaction of biological macromolecules with electromagnetic fields. Our results can find application in biotechnology, food technology and life sciences application, considering the development of enzyme-based biosensors and bioreactors with surface-immobilized enzymes.

2. Materials and Methods

Experimental setup used in our present research was analogous to that described in detail in our previous paper [

16]. The difference consisted in that the coil has been covered with metallic foil in order to provide proper shielding of transverse electromagnetic radiation. In our experiments reported herein, the working enzyme solution was placed at a 2 cm distance from the coil’s side, while the control enzyme sample was placed three meters away from the coil. The enzyme concentration of both the working and the control solution was 0.1 µM, and the volume of each sample solution was 1 mL. The enzyme solutions were incubated in the designated locations for 40 min. After the incubation, the solutions were subjected to parallel AFM and spectrophotometric analysis.

Samples for AFM measurements were prepared by direct surface adsorption [

36] as described in our previous papers [

15,

16,

17,

22]. The mica AFM substrates with surface-adsorbed HRP particles were scanned with a Titanium atomic force microscope (NT-MDT, Zelenograd, Russia; the microscope pertains to the equipment of “Human Proteome” Core Facility of the Institute of Biomedical Chemistry, supported by Ministry of Education and Science of Russian Federation, agreement 14.621.21.0017, unique project ID: RFMEFI62117X0017). At least ten scans were obtained for each AFM substrate studied. Blank experiments were performed with the use of protein-free buffer. No objects with heights exceeding 0.5 nm were observed in the blank experiments. Atomic force microscope operation, treatment of the AFM images obtained (flattening correction etc.) and exporting the AFM data to ASCII format were performed using a NOVA Px software (NT-MDT, Moscow, Zelenograd, Russia) supplied with the microscope. The number of the visualized particles in the obtained AFM images was calculated with a specialized AFM data processing software developed in IBMC. The distribution of the AFM-visualized objects with heights (density functions), and the number of particles visualized by AFM (normalized per 400 µm

2) were calculated as described by Pleshakova et al. [

37].

Spectrophotometry measurements were performed according to well-established technique described previously [

15,

17,

22]; this technique, based on the interaction of the HRP enzyme with its substrate ABTS in slightly acidic (pH 5.0) phosphate-citrate buffer, was originally reported by Sanders et al. [

38]. The spectrophotometric measurements were carried out with an Agilent 8453 spectrophotometer at 405 nm.

3. Results

3.1. Atomic Force Microscopy

Figure 1 displays typical AFM images of HRP adsorbed onto mica from control enzyme solution (which was incubated three meters away from the coil;

Figure 1a) and from working enzyme solution (which was incubated at a 2 cm distance from the coil’s side).

The images in

Figure 1 indicate that HRP is adsorbed on mica in the form of compact objects. In order to find out whether there was an effect on HRP aggregation in our experiments, let us analyze the results of AFM data processing.

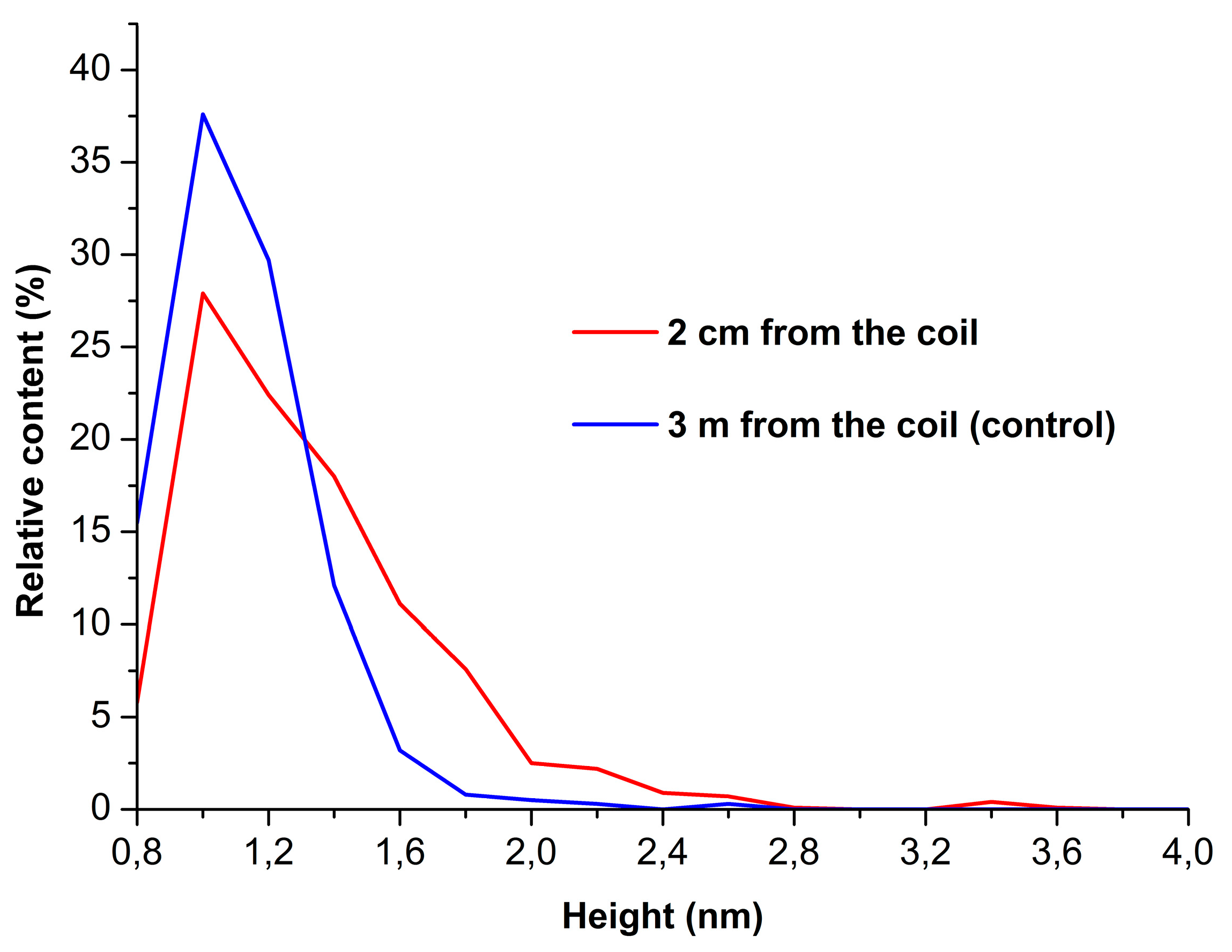

Figure 2 displays density functions’ plots obtained for working (red curve) and control (blue curve) enzyme samples.

By analyzing the shape of the density functions’ plots, one can observe an increase in the content of high (>1.4 nm) objects in the working enzyme sample in comparison with the control one. As was justified previously [

22], these high objects can be attributed to aggregated form of mica-adsorbed HRP. Accordingly, this allows us to make a conclusion that the incubation of 0.1 µM HRP solution near the side of a shielded coil with flowing glycerol induces aggregation of the enzyme upon its adsorption onto mica.

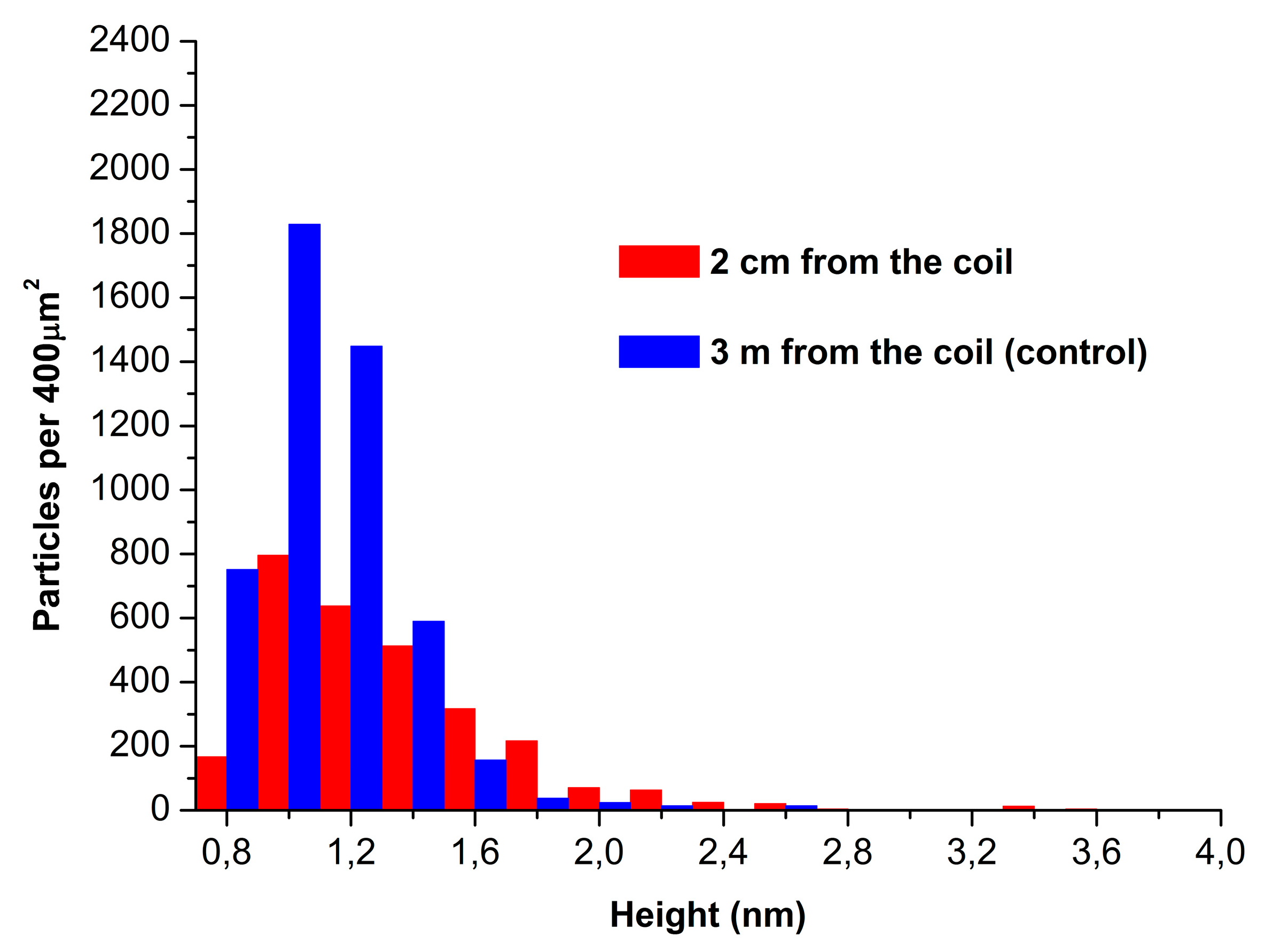

Figure 3 displays absolute distribution of the number of particles, visualized by AFM on mica substrates, with height.

The data presented in

Figure 3 indicate that the number of particles adsorbed from the working enzyme sample (red bars;

N400=2800 particles per 400 µm

2) and that of particles adsorbed from the control enzyme sample (blue bars;

N400=4800 particles per 400 µm

2) are of the same order of magnitude.

3.2. Spectrophotometric Estimation of HRP Enzymatic Activity

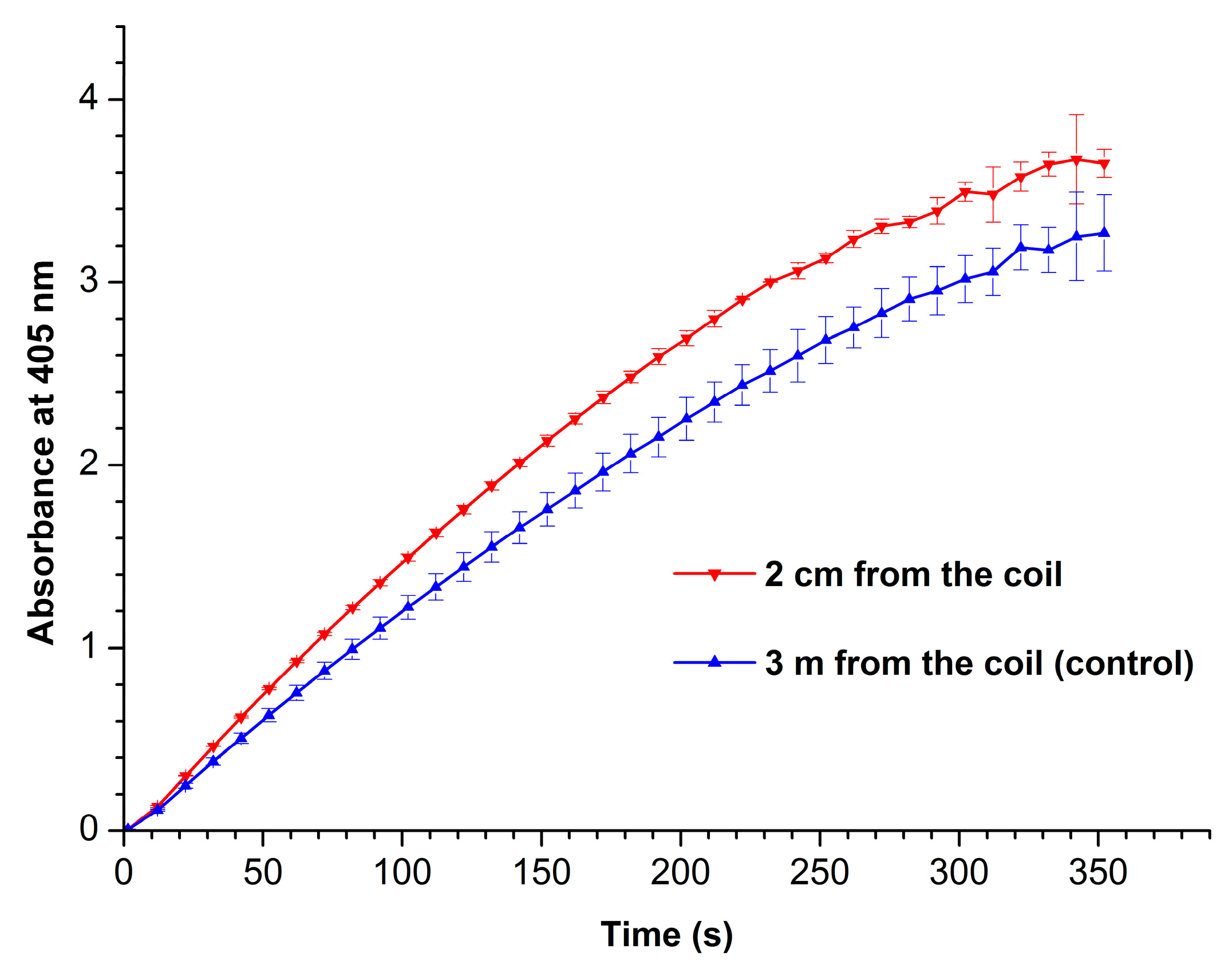

Figure 4 displays absorbance vs. time curves recorded at 405 nm for working (red curve) and control (blue curve) enzyme samples.

From

Figure 4, one can see that the enzymatic activity of HRP after its incubation near the coil with flowing glycerol is higher than that of the enzyme in the control sample. The phenomenon of HRP enzymatic activity enhancement by external electromagnetic field has been previously observed by Yao et al. [

32] after radio frequency treatment of this enzyme at 50°C.

4. Discussion

In our present research, we have studied the influence of glycerol flow, organized in a ground-shielded cylindrical coil, on the properties of horseradish peroxidase enzyme. Adsorption properties of the enzyme have been investigated by AFM, while its enzymatic activity against ABTS substrate has been assessed by spectrophotometry.

In our experiments reported, AFM has allowed us to reveal an increase in the HRP aggregation on mica. Moreover, a slight increase in the enzymatic activity of HRP has been observed after the incubation of the enzyme near the coil. It is to be emphasized that the coil with flowing glycerol has been ground-shielded. Accordingly, the effect observed in our experiments cannot be attributed to the action of a transverse electromagnetic radiation, which could take place if the coil was not ground-shielded. Accordingly, the phenomena revealed in our experiments can be explained by formation of a longitudinal field by the flow of glycerol. The effect of such a field, intentionally formed by means of a specialized generator, on the enzyme was observed for the first time by Ivanov et al. [

22]. Therein, it was noted that such electromagnetic fields, which have a specific topology [

39,

40,

41,

42], can influence biological objects (including enzymes) at even very low power densities comparable with the background radiation level [

22]. The effect of the field on both the enzyme aggregation and its enzymatic activity can be explained by the change in the structure of the enzyme’s hydration under the action of the field.

Indeed, the structure of hydration shell was shown to be one of the factors influencing the functioning of biological macromolecules [

43]. And in case of enzymes, their enzymatic activity can well be affected by alterations in their hydration shells [

43,

44,

45]. And this is what we have observed in our experiments with HRP enzyme. This is how we explain the effect of glycerol flow on HRP enzyme in our particular case.

5. Conclusions

The flow of a dielectric fluid (glycerol) through a ground-shielded cylindrical coil has been found to affect physicochemical properties of HRP enzyme, whose 0.1 µM solution has been incubated at a 2 cm distance from the coil for 40 minutes. Namely, such an incubation has led to an increased aggregation of the enzyme on mica, as has been revealed at the single-molecule level by AFM. Moreover, its enzymatic activity against ABTS has been found to increase after the incubation near the coil — as compared with the control enzyme sample incubated three meters away from the coil. The results obtained can be of use in the development of triboelectric generators, and should be taken into consideration in the development of novel flow-based based biosensors and bioreactors with surface-immobilized enzymes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yuri D. Ivanov and Vadim Yu. Tatur; Data curation, Anastasia A. Valueva, Maria O. Ershova, Ivan D. Shumov, and Andrey F. Kozlov; Formal analysis, Ivan D. Shumov, Nina D. Ivanova, and Vadim S. Ziborov; Investigation, Yuri D. Ivanov, Ivan D. Shumov, Anastasia A. Valueva, Irina A. Ivanova, Maria O. Ershova, and Vadim S. Ziborov; Methodology, Yuri D. Ivanov and Vadim Yu. Tatur; Project administration, Yuri D. Ivanov; Resources, Vadim Yu. Tatur, Andrei A. Lukyanitsa and Vadim S. Ziborov; Software, Andrei A. Lukyanitsa; Supervision, Yuri D. Ivanov; Validation, Vadim S. Ziborov; Visualization, Ivan D. Shumov, Andrey F. Kozlov and Anastasia A. Valueva; Writing – original draft, Ivan D. Shumov and Yuri D. Ivanov; Writing – review & editing, Yuri D. Ivanov.

Funding

The work was performed (done, carried out) within the framework of the Program for Basic Research in the Russian Federation for a long-term period (2021-2030) (No. 122030100168-2).

Data Availability Statement

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Y.D.I.

Acknowledgments

The AFM measurements were performed employing a Titanium multimode atomic force microscope, which pertains to “Avogadro” large-scale research facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pauling, L. General chemistry. 3rd Ed. W.H. Freeman and company: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1970.

- Jacobsen, D.; McMartin, K.E. Alcohols and glycols. In: Human Toxicology. Ed. by J. Descotes. Elsevier Science B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996; PP. 623-648. https://doi. org/10.1016/B978-0-444-81557-6.X5000-X.

- Vijayendran, R.A.; Ligler, F.S.; Leckband, D.E. A computational reaction-diffusion model for the analysis of transport-limited kinetics. Anal. Chem. 1998, 71, 5405–5412. [CrossRef]

- Teeparuksapun, K.; Hedström, M.; Mattiasson, B. A Sensitive Capacitive Biosensor for Protein a Detection Using Human IgG Immobilized on an Electrode Using Layer-by-Layer Applied Gold Nanoparticles. Sensors 2022, 22, 99. [CrossRef]

- Kamat, V.; Rafique, A. Exploring sensitivity & throughput of a parallel flow SPRi biosensor for characterization of antibody-antigen interaction. Anal. Biochem. 2017, 525, 8-22. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Singh, A.; Wu, H.; Kroe-Barrett, R. Comparison of biosensor platforms in the evaluation of high affinity antibody-antigen binding kinetics. Anal. Biochem. 2016, 508, 78-96. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gorshkova, I.I.; Fu, G.L.; Schuck, P. A comparison of binding surfaces for SPR biosensing using an antibody–antigen system and affinity distribution analysis. Methods 2013, 59, 328-335. [CrossRef]

- Dobson, J.; Kumar, A.; Willis, L.F.; Tuma, R.; Higazi, D.R.; Turner, R.; Lowe, D.C.; Ashcroft, A.E.; Radford, S.E.; Kapur, N.; Brockwell, D.J. Inducing protein aggregation by extensional flow. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114 (18), 4673-4678. [CrossRef]

- Ravelo, B.; Duval, F.; Kane, S.; Nsom, B. Demonstration of the triboelectricity effect by the flow of liquid water in the insulating pipe. J. Electrost. 2011, 69, 473–478. [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Lee, H.; Im, D.J.; Kang, I.S.; Lim, G.; Kim, D.S.; Kang, K.H. Spontaneous electrical charging of droplets by conventional pipetting. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Cheedarala, R.K.; Song, J.Il. Harvesting of flow current through implanted hydrophobic PTFE surface within silicone-pipe as liquid nanogenerator. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3700. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, C.; Song, Y.; ... & Wang, Z. L. A droplet-based electricity generator with high instantaneous power density. Nature 2020, 578(7795), 392-396. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41586-020-1985-6.

- Zhao, L.; Liu, L.; Yang, X.; Hong, H.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J.; Tang, Q. Cumulative charging behavior of water droplets driven freestanding triboelectric nanogenerator toward hydrodynamic energy harvesting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8(16), 7880-7888. https://doi. org/10.1039/D0TA01698E.

- Haque, R.I.; Arafat, A.; Briand, D. Triboelectric effect to harness fluid flow energy. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2019, 1407, 012084. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, Y.D.; Pleshakova, T.O.; Shumov, I.D.; Kozlov, A.F.; Romanova, T.S.; Valueva, A.A.; Tatur, V.Y.; Stepanov, I.N.; Ziborov, V.S. Investigation of the Influence of Liquid Motion in a Flow-based System on an Enzyme Aggregation State with an Atomic Force Microscopy Sensor: The Effect of Water Flow. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4560. [CrossRef]

- Ziborov, V.S.; Pleshakova, T.O.; Shumov, I.D.; Kozlov, A.F.; Ivanova, I.A.; Valueva, A.A.; Tatur, V.Y.; Negodailov, A.N.; Lukyanitsa, A.A.; Ivanov, Y.D. Investigation of the Influence of Liquid Motion in a Flow-Based System on an Enzyme Aggregation State with an Atomic Force Microscopy Sensor: The Effect of Glycerol Flow. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4825. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, Y.D.; Pleshakova, T.O.; Shumov, I.D.; Kozlov, A.F.; Ivanova, I.A.; Ershova, M.O.; Tatur, V.Y.; Ziborov, V.S. AFM Study of the Influence of Glycerol Flow on Horseradish Peroxidase near the in/out Linear Sections of a Coil. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1723. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Wu, H.; Li, N.; Tan, X.; Deng, H.; Zhang, X.; Tang, J.; Li, Y. Triboelectric Mechanism of Oil-Solid Interface Adopted for Self-Powered Insulating Oil Condition Monitoring. Adv. Sci. 2023, 2207230. [CrossRef]

- Tanasescu, F.; Cramariuc, R. Electroststica în technica. Bucuresti, Editura Technica, 1977.

- Balmer, R. Electrostatic Generation in Dielectric Fluids: The Viscoelectric Effect. Proceedings of WTC2005 World Tribology Congress III September 12-16, 2005, Washington, D.C., USA. Paper No. WTC2005-63806. https://doi. org/10.1115/WTC2005-63806.

- Shafer, M.R.; Baker, D.W.; Benson, K.R. Electric Currents and Potentials Resulting From the Flow of Charged Liquid Hydrocarbons Through Short Pipes. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. C — Eng. Instrumentation 1965, 69C (4), 307-317.

- Ivanov, Y.D.; Pleshakova, T.O.; Shumov, I.D.; Kozlov, A.F.; Ivanova, I.A.; Valueva, A.A.; Tatur, V.Y.; Smelov, M.V.; Ivanova, N.D.; Ziborov, V.S. AFM imaging of protein aggregation in studying the impact of knotted electromagnetic field on a peroxidase. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9022. [CrossRef]

- Davies, P. F., Rennke, H. G. & Cotran, R. S. Influence of molecular charge upon the endocytosis and intracellular fate of peroxidase activity in cultured arterial endothelium. J. Cell Sci. 1981, 49(1), 69–86. 86. [CrossRef]

- Welinder K.G. Amino acid sequence studies of horseradish peroxidase. amino and carboxyl termini, cyanogen bromide and tryptic fragments, the complete sequence, and some structural characteristics of horseradish peroxidase C. Eur. J. Biochem. 1979, 96, 483-502. [CrossRef]

- Tams J.W., Welinder K.G. Mild chemical deglycosylation of horseradish peroxidase yields a fully active, homogeneous enzyme. Anal. Biochem. 1995, 228, 48-55. [CrossRef]

- Veitch, N.C. Horseradish peroxidase: a modern view of a classic enzyme. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 249–259. [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, T.; Tamura, T.; Sato, M. Influence of pulsed electric field on various enzyme activities. J. Elstat. 2007, 65, 156-161. [CrossRef]

- Wasak, A.; Drozd, R.; Jankowiak, D.; Rakoczy, R. The influence of rotating magnetic field on bio-catalytic dye degradation using the horseradish peroxidase. Biochem. Eng. J. 2019, 147, 81–88. [CrossRef]

- Emamdadi, N.; Gholizadeh, M.; Housaindokht, M.R. Investigation of static magnetic field effect on horseradish peroxidase enzyme activity and stability in enzymatic oxidation process. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 170, 189–195. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Sun, F.; Xu, B.; Gu, N. The quasi-one-dimensional assembly of horseradish peroxidase molecules in presence of the alternating magnetic field. Coll. Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2010, 360 (1-3), 94-98. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J; Zhou, H.; Jin, Y.; Wang, M.; Gu, N. Magnetically enhanced dielectrophoretic assembly of horseradish peroxidase molecules: chaining and molecular monolayers. Chem. Phys. Chem. 2008, 9(13), 1847-1850. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Pang, H.; Wang, Y.; Fu, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y. The effect of radio frequency heating on the inactivation and structure of horseradish peroxidase. Food Chem. 2023, 398, 133875. [CrossRef]

- Fortune, J.A.; Wu, B.-I.; Klibanov, A.M. Radio Frequency Radiation Causes No Nonthermal Damage in Enzymes and Living Cells. Biotechnol. Prog. 2010, 26(6), 1772-1776. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.C.; Barreto, M.T.; Gonçalves, K.M.; Alvarez, H.M.; Heredia, M.F.; De Souza, R.O.M.; Cordeiro, Y.; Dariva, C.; Fricks, A.T. Stability and structural changes of horseradish peroxidase: Microwave versus conventional heating treatment. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2015, 69, 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Caliga, R.; Maniu, C.L.; Mihăşan, M. ELF-EMF exposure decreases the peroxidase catalytic efficiency in vitro. Open Life Sci. 2016, 11, 71–77. [CrossRef]

- Kiselyova, O.I.; Yaminsky, I.; Ivanov, Y.D.; Kanaeva, I.P.; Kuznetsov, V.Y.; Archakov, A.I. AFM study of membrane proteins, cytochrome P450 2B4, and NADPH–Cytochrome P450 reductase and their complex formation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999, 371, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Pleshakova, T.O.; Kaysheva, A.L.; Shumov, I.D.; Ziborov, V.S.; Bayzyanova, J.M.; Konev, V.A.; Uchaikin, V.F.; Archakov, A.I.; Ivanov, Y.D. Detection of hepatitis C virus core protein in serum using aptamer-functionalized AFM chips. Micromachines 2019, 10, 129. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, S.A.; Bray, R.C.; Smith, A.T. pH-dependent properties of a mutant horseradish peroxidase isoenzyme C in which Arg38 has been replaced with lysine. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994, 224, 1029–1037. [CrossRef]

- Ranada, A. F. Knotted solutions of the Maxwell equations in vacuum. J. Phys. A: Mathematical and General 1990, 23 (16), L815; [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Gheorghe, A.; Tiurev, K.; Ollikainen, T.; Möttönen, M.; Hall, D.S. Synthetic electromagnetic knot in a three-dimensional skyrmion. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4 (3), eaao3820; [CrossRef]

- Smelov, M. V. Experimental study of nodular antennas in the form of shamrock and pentacle. Radio Engineering 2013, 2, 023-029.

- Nefedov, E. I., Ermolaev, Y. M., Smelov, M. V. Experimental study of excitation and propagation of nodular electromagnetic waves in various media. Radio Engineering 2014, 2, 31-34.

- Fogarty, A.C.; Laage, D. Water Dynamics in Protein Hydration Shells: The Molecular Origins of the Dynamical Perturbation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 7715−7729. [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.K.; Rakshit, S.; Mitra, R.K.; Pal, S.K. Role of hydration on the functionality of a proteolytic enzyme α-chymotrypsin under crowded environment. Biochimie 2011, 93, 1424–1433. [CrossRef]

- Laage, D.; Elsaesser, T.; Hynes, J.T. Water Dynamics in the Hydration Shells of Biomolecules. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10694−10725. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).