1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted many aspects of our lives, including healthcare. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries implemented lockdowns and other public health measures to limit the spread of the virus. These measures often resulted in the cancellation or postponement of nonurgent medical appointments and procedures [

1].

On March 14, Royal Decree 463/2020 was published in Spain, declaring a state of alarm to manage the global health crisis, and instituted the lockdown and confinement of all Spaniards, with the exception of essential activities [

2,

3]. The fear of the unknown, the panic associated with contagion risk, the overloaded emergencies departments and hospitals, as well as the redistribution of health staff to manage the public health crisis, are factors that contributed to diminished care available to patients with chronic diseases. Since patients were formally instructed to stay at home due to the high transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2, most nonurgent consultations, procedures, and follow-up or routine appointments were cancelled or postponed [

3,

4].

The impact of COVID-19 on long-term health outcomes for patients with chronic conditions is characterized as a “second hit” [

5] and will likely disproportionately affect vulnerable populations. One such group is people living with HIV (PLWH). As HIV infection already has the character of a chronic disease whose follow-up requires frequent visits to the hospital (consultations, tests, pharmacy, visits to other services), it was foreseeable that the isolation and confinement measures adopted would have had an impact on the care of PLWH [

6,

7,

8,

9].

In addition to the logistical challenges of accessing care during a pandemic, PLWH may also face increased psychological stress and anxiety due to the heightened risk of COVID-19 complications for those with underlying health conditions [

10]. This stress can further impact adherence to treatment and overall health outcomes [

10].

Despite the considerable challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare providers and organizations have developed various strategies to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on HIV care. Our service has implemented several measures to ensure continuity of care for people living with HIV. We have utilized telemedicine and virtual appointments to enable patients to assess their clinical status and receive medical advice without the need for physical hospital visits. Additionally, we have provided telephone-based communication of laboratory test results, such as viral load and CD4 counts. We have also placed increased emphasis on home-based care and self-management. To ensure uninterrupted care for newly diagnosed patients, we have maintained an open in-person consultation service. Furthermore, we have made adjustments to the dispensing of medication. In Spain, antiretroviral medication is usually dispensed in hospitals, requiring patients to visit the pharmacy service in person. So that, we have modified our medication dispensing procedures by collaborating with the Pharmacy Service to devise a contingency plan that involves home delivery of antiretroviral medication to patients, thus reducing the risk of COVID-19 exposure.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on healthcare systems and the provision of care for people living with HIV. However, it has also highlighted the importance of addressing health disparities and social determinants of health, which may disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, including PLWH. While the pandemic has presented numerous challenges, healthcare providers and organizations have demonstrated resilience and innovation in adapting to these challenges and ensuring that PLWH continue to receive the care they need.

The aim of this study was to examine the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the care of PLWH while considering the measures taken to ensure minimal losses. We compared treatment adherence, control of immunovirological status, the number of hospital admissions, new enrolments, and deaths during the pandemic with those over two periods of similar duration (the “pre-pandemic” period and “post- pandemic” periods, respectively).

This study also provides valuable insights into the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the care of PLWH and the measures taken to mitigate those impacts. Moving forward, it is essential to continue prioritizing the care of PLWH and addressing the underlying social determinants of health to improve health outcomes for vulnerable populations. We hope that this study can contribute to improving the ongoing care of PLWH. We will need to redouble our efforts to achieve the new proposed global 95–95–95 targets set by UNAIDS, which aim to ensure that 95% of people diagnosed with HIV are on treatment and have a suppressed viral load.

Overall, our experience has shown that adapting to the pandemic and finding innovative ways to provide care for PLWH is feasible, and that it can be achieved with the collaboration of healthcare providers, organizations, and patients. By doing so, we can ensure that PLWH continue to receive the care they need and minimize the potential long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on their health outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study in the Infectious Diseases Department of the Ramon y Cajal University Hospital in Madrid, Spain. The study population consisted of 3265 individuals diagnosed with HIV infection and registered in the Patient Information and Management Systems Service of Ramón y Cajal University Hospital.The data were analyzed during the period from March 2019 to September 2021.

For the purposes of this study, we have divided this period of time into three distinct periods spanning up to 12 months: the pre-pandemic period from March 2019 to February 2020; the pandemic period from March 2020 to February 2021; and the post-pandemic period from March 2021 to September 2021, prior to the availability of vaccinations.

To analyze the impact of the pandemic on HIV care, we examined the following indicators: (1) the number of PLWH that first visited the clinic; (2) treatment adherence, as measured by the frequency with which the patients picked up the medication at the hospital pharmacy; (3) detectability of viral load; and (4) hospitalizations and death. To obtain these data, we collaborated with the Information Systems and Patient Management Service, the Microbiology Department, which provided information on viral loads, and the Pharmacy Department, which provided information on antiretroviral drugs dispensed during these periods.

We compared these five variables across different periods. Firstly, we compared the variables between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods, and then the months of the pandemic with those of the post-pandemic period. Thus, we reviewed whether the number of first visits increased or decreased, and consequently, the number of HIV diagnoses during these periods. We reviewed the supply of antiretroviral drugs by the Pharmacy Service of Ramón y Cajal University Hospital, since patients went from having to collect their medications from the hospital every three months to being able to receive them at home thanks to Resolution 197/2020 of the General Directorate of Economic and Financial Management and Pharmacy of the Community of Madrid, published on March 31, 2020, which authorized home medication delivery. We also analyzed whether undetectable viral loads increased or decreased during the pandemic due to this change in drug administration and medical consultations. Finally, we compared the number of hospitalizations and deaths during these periods, differentiating between those caused by SARS-CoV-2 and other causes unrelated to it.

The data were expressed as a mean ± the standard deviation (SD) or as proportions (%). Categorical variables were expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages. We compared continuous variables using a Student´s t-test or a Mann-Whitney U test, according to their distribution. The associations between categorical variables were assessed using a chi-squared test or a Fisher´s exact test, as appropriate. The monthly number of events and the total number of events with estimated 95% confidence intervals were compared across the three periods by means of the Odds Ratio (OR). The events were examined against logistic regression and linear regression distributions. A log transformation was applied to normalize the residuals and the predicted mean was converted to a geometric mean. Statistical significance was identified as p<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp. 2019. Stata: Release 16.1. Statistical Software; StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA).

The Ethics Committee of Ramón y Cajal University Hospital was consulted, and after their analysis, they declared that requesting approval was not necessary.

3. Results

Within the study period, 3265 patients with HIV were examined at our clinic, resulting in 8,860 outpatient visits, including 466 first visits (5.26%). We observed a decrease in the number of new PLWH visiting the clinic from the beginning of the pandemic period, with only 116 out of 2,805 visits (3.97%). This percentage was significantly lower compared to the pre-pandemic period (204 visits, 6.71%, p<0.001) and the post-pandemic period (146 visits, 5.25%, p=0.006) (

Table 1).

Similarly, we observed that the proportion of initial visits was 73.87% higher in the pre-pandemic period compared to the pandemic period (OR=1.738784 CI95% 1.76241 – 2.196831 p<0.001). In the post-pandemic period, the number of initial visits was 28.28% higher than in the pandemic period (OR=1.28286 CI95% 0.9996931 – 1.646235 p=0.05).

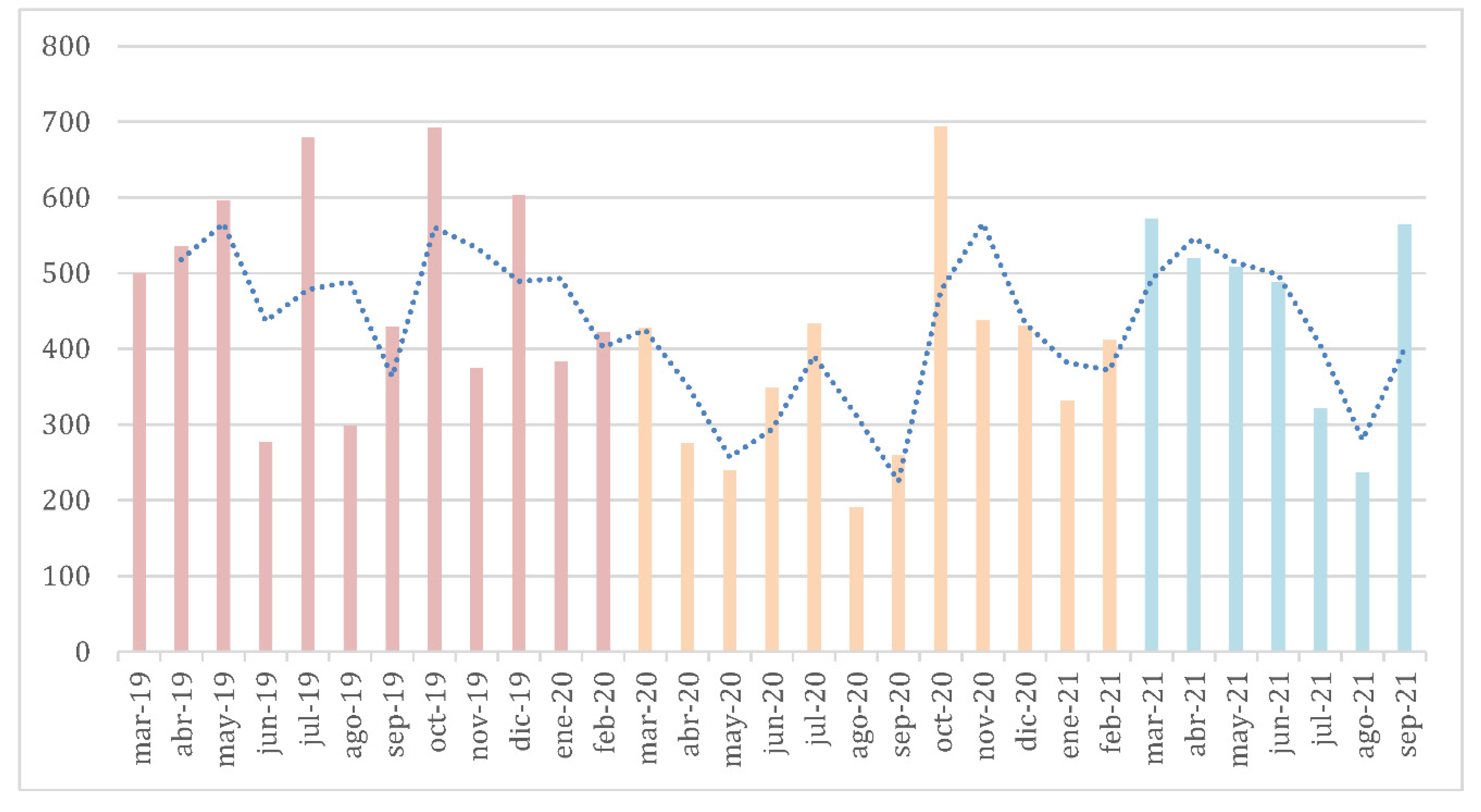

Throughout the longest stretch of time that comprised the pandemic period (March 2020 to February 2021), the total number of viral load tests performed decreased compared to the number of tests performed in the pre-pandemic and the post-pandemic periods (

Figure 1). During the pandemic period, 2,414 viral loads were analyzed, compared to 2,831 and 2,640 analyzed respectively in the pre- and post-pandemic periods (both p< 0.001). Logistic regression results showed that the average number of viral load tests performed during the pandemic was 1.47 per patient. In the pre-pandemic period, more viral load tests were performed, specifically 0.47 more tests on average than during the pandemic period (p<0.001). In the post-pandemic period, the number of viral load tests performed decreased slightly compared to the pandemic period; it decreased by 0.03 (p=0.048).

Although the number of plasma viral load tests decreased during the pandemic period, the proportion of undetectable viral loads (referring to patients who have viral suppression with a viral load less than 50 copies/mL) [

9] remained stable. Specifically, throughout the pandemic period, 2,182 out of 2,560 viral load tests analyzed resulted in viral suppression, corresponding to a percentage of 90.39%. This percentage was comparable to the pre-pandemic period, where 2,408 out of 2,831 tests (85.06%) resulted in viral suppression, as well as the post-pandemic period, where 2,496 out of 2,696 tests (92.65%) resulted in viral suppression (

Table 1).

In fact, the proportion of patients with at least one detectable viral load during the pre-pandemic period was 65.21% higher compared to the pandemic period (OR=1.652154 CI95% 1.393459 – 1.958876 p<0.001). In the post-pandemic period, the proportion of patients with at least one detectable viral load was reduced by 25.40% compared to that measured in the pandemic period (OR=0.745954 CI95% 0.6112016 – 0.9104154 p=0.004).

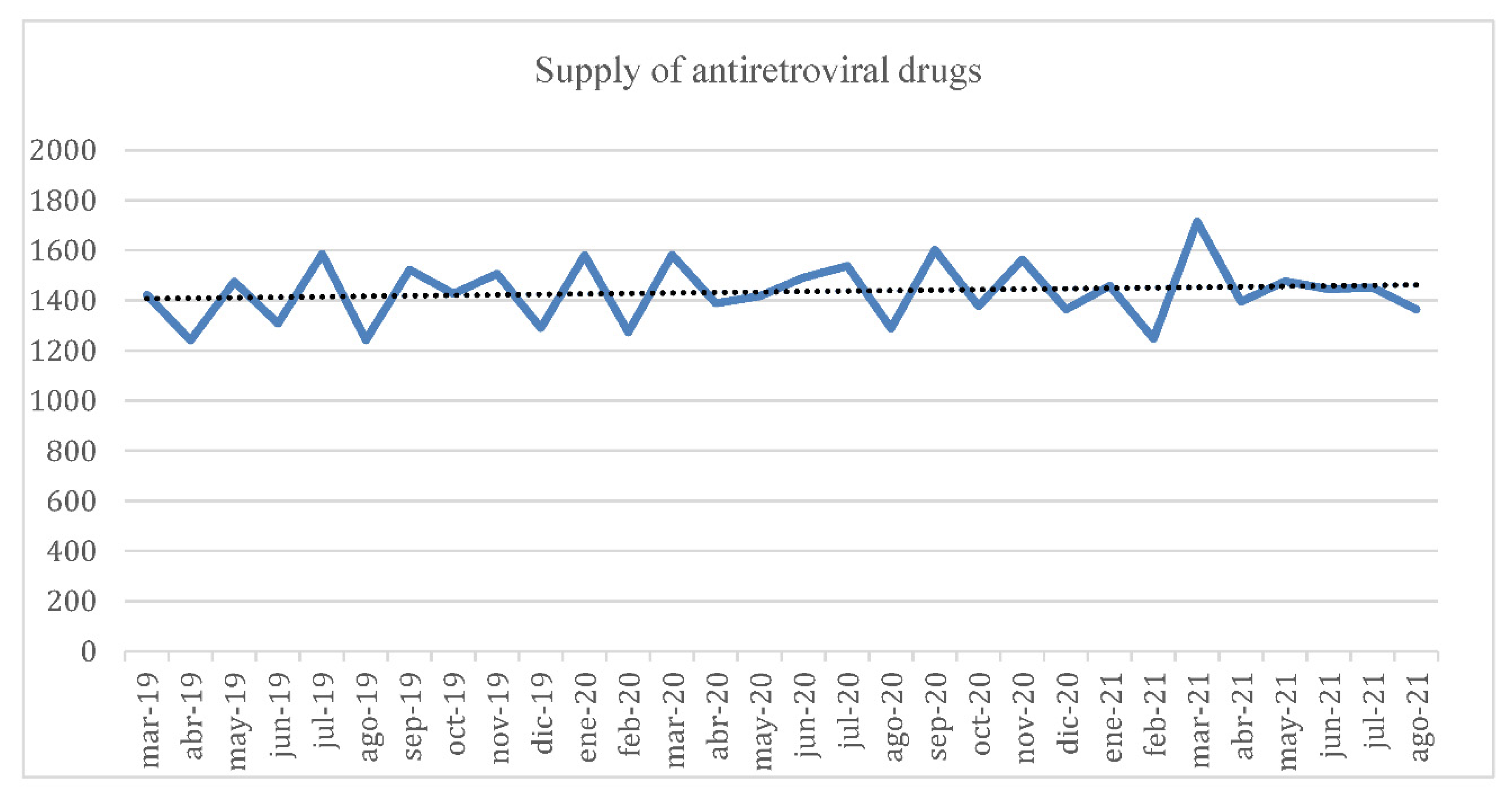

We did not observe any change in adherence to treatment, which was determined using Pharmacy records (

Figure 2). The median number of drug refills during the pandemic period was 1454, compared to 1425 (p=0.395) and 1449 (p=0.843) during the pre- and post- pandemic periods, respectively.

We observed no impact of the pandemic on the number of PLWH hospitalizations for reasons other than COVID-19 in our hospital. The total number of monthly admissions remained stable across the three periods. Notably, in-hospital mortality rates of PLWH during the pandemic period was reduced compared to the pre-pandemic period (OR 2.29, CI 1.49 - 3.53, p<0.001). The risk of death, in terms of Odds, was approximately twice as high in the pre-pandemic period compared to the pandemic period. The differences found between the pandemic and post-pandemic periods were not significant (OR 1.11, CI 0.67 - 1.82, p=0.684). None of the recorded deaths among PLWH were associated with a SARS-CoV-2 infection and most deaths were related to non-AIDS events, especially neoplasms (accounting for 38.4% of all deaths). Only 7.7% of deaths across the three periods were related to HIV infection (three lymphomas, one Kaposi's sarcoma).

Overall, our study highlights the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the healthcare of patients with HIV, as evidenced by the significant decrease in clinic visits during the pandemic period. Despite this decrease, we did not observe any adverse effects on the proportion of patients with undetectable viral loads or adherence to ART. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the pandemic may have had a protective effect on the in-hospital mortality rates of patients with HIV.

4. Discussion

Our study examined the effect of COVID-19 restrictions on the quality of HIV care at our hospital. We showed that, although the number of viral load tests decreased throughout the months when public health measures were most stringent, the proportion of patients with undetectable viral loads remained stable. Moreover, the number of patients that continued to use their medications, the number of hospitalizations, and the number of deaths were not negatively influenced by lockdown restrictions and other measures to mitigate the impact and spread of SARS-CoV-2. Similar findings were widely reported from various countries (Spain, USA, Perú, Uganda) [

12,

13,

14,

15]. This study further demonstrates the impact of COVID-19 on PLWH, and indicates that certain hospital practices may have allowed patients to continue to receive care when the overall healthcare system had been severely disrupted.

To mitigate the impacts of the pandemic on the care available to PLWH, it is imperative to rely on the HIV care continuum (HCC)[

16] as a guide. The HCC was designed to model progressive stages of HIV care. This continuum consists of five steps: i) diagnosis; ii) linkage to care; iii) retention in care; iv) adherence to antiretroviral therapy; and v) viral suppression. Due to quarantine measures and fewer in-person hospital visits, there are reports of reduced access to routine HIV testing, linkage to care, and retention in care [

16,

17].

Although our "first visit" clinic remained open to maintain the rate of new diagnoses, various community organizations and associations that connect patients with hospital centers reduced their field activities due to lockdown measures and social distancing orders. One option to maintain access to testing includes distributing self-diagnostic tests in pharmacies for people at a higher risk of contracting HIV, a practice carried out in Ottawa (Canada) [

18].

For patients who were already aware of their HIV status, COVID-19 lockdown measures may have limited their adherence to antiretroviral therapy and viral suppression. The integration of an ART dispensing program, coordinated by the hospital pharmacy, was implemented during the most stringent public health lockdown measures. This new initiative helped to ease concerns that ART may be interrupted due to difficulties traveling to the hospital and for safety reasons, allowed patients to avoid a crowded hospital pharmacy. The present study examined our experience managing patient needs and successfully maintained the administration of ART throughout the pandemic, where no differences were observed between the pre-pandemic and pandemic stages.

Overall, our findings suggest that patients with HIV are achieving better viral suppression, despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The availability of more effective ART regimens, increased awareness of the importance of adherence, and the implementation of the HCC model may all contribute to these positive outcomes. Continued efforts to maintain access to care and support consistent adherence to ART will be critical for sustaining these gains and improving patient outcomes over the long term.

These practices made it easier for our patients to continue with consistent therapeutic compliance. Home dispensing of ART can similarly support patient access to care and reduce the burden on the hospital system [

19].

Regarding the number of hospitalizations and deaths among PLWH, we did not observe a greater number of hospitalizations or deaths due to the SARS-CoV-2 infection across the general population, as reported in other research [

20,

21]. However, despite efforts to maintain care for HIV patients, the number of deaths throughout the pandemic and post-pandemic period is increasing. Most recorded deaths are associated with secondary or non-AIDS events. This observation may be due to the unchanged rate of undetectable persons across these time periods.

In summary, people with chronic illnesses such as HIV rely heavily on regular consultations with their healthcare providers to monitor their disease and/or risk factors associated with their disease [

22]. As described above, the pandemic has impacted the rate of disease diagnosis, and it has negatively impacted the quality of care for patients with chronic diseases [

23,

24]. In the hospital examined in this study, we adopted some measures that successfully mitigated the impact of the pandemic on patient care that may be adopted to further support consistent patient care. These measures include maintaining access to a "first visit" clinic to facilitate the continuity of care, home delivery of ART, and rapid initiation of ART. The ART dispensing practices contributed to HIV treatment adherence and decreased the risk of COVID-19 transmission. Although our findings show consistency in retention and viral suppression of PLWH, careful monitoring over the coming years is critical. Core healthcare priorities must be sustained and healthcare decision makers need to creatively adapt patient care practices to manage shifting public health challenges.

Author Contributions

MRCS: conceptualization, literature review, writing original draft, review and editing. MDC and MJC: writing original draft and editing. CA: writing original draft preparation. AM: methodology. SM: writing original draft, review, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Declaration of interest: We declare no competing interests.

References

- Hale, T. , Angrist, N., Cameron-Blake, E., Hallas, L., Kira, B., Majumdar, S. & Tatlow, H. (2021). The variation in effectiveness of interventions to reduce COVID-19 transmission in the early stages of the pandemic.

- Gavriatopoulou M, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Korompoki E, Fotiou D, Migkou M, Tzanninis I-G, et al. Emerging treatment strategies for COVID-19 infection. Clin Exp Med. 2021; 21:167–179. [CrossRef]

- Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Beckwith CG, Dowshen N, Gordon CM, Horn T, et al. Guidelines for Improving Entry Into and Retention in Care and Antiretroviral Adherence for Persons With HIV: Evidence-Based Recommendations From an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care Panel. Ann Intern Med. 2012; 156:817–33. [CrossRef]

- Royal Decree 463/2020, of March 14, declaring the state of alarm for the management of the health crisis situation caused by COVID-19. BOE núm. 67, de 14/03/2020. Available: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2020/03/14/463.

- Nundy S, Kaur M, Singh P. Preparing for and responding to Covid-19's ‘second hit'. Healthc (Amst). 2020; 8:100461. [CrossRef]

- Ballester-Arnal, R.; Gil-Llario, M.D. The Virus that Changed Spain: Impact of COVID-19 on People with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2020, 24, 2253–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridgway JP, Schmitt J, Friedman E, Taylor M, Devlin S, McNulty M, et al. HIV Care Continuum and COVID-19 Outcomes Among People Living with HIV During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Chicago, IL. AIDS Behav 2020; 24:2770–2772. [CrossRef]

- ONUSIDA. 90-90-90 Un ambicioso objetivo de tratamiento para contribuir al fin de la epidemia de sida [Internet]. ONUSIDA. 2014 [citado el 10 de mayo de 2022]. Disponible en: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90_90_90_es.pdf.

- Mcginnis KA, Skanderson M, Justice AC, Akgün KM, Tate JP, King JT, et al. HIV care using differentiated service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide cohort study in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. JIAS. 2021; 24:17 – 23. [CrossRef]

- Brouard, B.; Vignier, N.; Jouveshomme, S.; Soudry-Faure, A.; Couffignal, C. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: impact on depressive symptoms and quality of life in people living with HIV. Journal of the International AIDS Society 2021, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle T, Smith C, Vitiello P, Cambiano V, Johnson M, Owen A, et al. The importance of HIV RNA detection below 50 copies per mL in HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy: an observational study. Lancet 2014 [citado el 27 de marzo de 2023];383:S44. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(14)60307-X/fulltext.

- Wilkinson L, Grimsrud A. The time is now: expedited HIV differentiated service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020 May;23(5):e25503. [CrossRef]

- Pierre, G.; Uwineza, A.; Dzinamarira, T. Attendance to HIV Antiretroviral Collection Clinic Appointments During COVID-19 Lockdown. A Single Center Study in Kigali, Rwanda. AIDS Behav. 2020, 24, 3299–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Thai hospitals to provide three to six month supplies of antiretroviral therapy, [Internet]. USA: UNAIDS; 2020. Available at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2020/march/20200325_thailand.

- Paredes, J.L.; Navarro, R.; Cabrera, D.M.; Diaz, M.M.; Mejia, F.; Caceres, C.F. Challenges to the continuity of care of people living with HIV throughout the COVID-19 crisis in Peru. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2021, 38, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridgway JP, Schmitt J, Friedman E, Taylor M, Devlin S, McNulty M, et al. HIV care continuum and COVID-19 outcomes among people living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic, Chicago, IL. AIDS Behav 2020;24 (10):2770–2772. [CrossRef]

- Vourli, G. , Katsarolis, I., Pantazis, N. et al. HIV continuum of care: expanding scope beyond a cross-sectional view to include time analysis: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 21, 1699 (2021). [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne P, Musten A, Orser L, Inamdar G, Grayson M-O, Jones C, et al. At-home HIV self-testing during COVID: implementing the GetaKit project in Ottawa. Can. J. Public Health. 2021 ; 112:587–594. 17 May. [CrossRef]

- PAUTAS PARA LA IMPLEMENTACIÓN DE LA DISPENSACIÓN DE MEDICAMENTOS ANTIRRETROVIRALES PARA VARIOS MESES [Internet]. OPS. WHO. UNAIDS. [citado el 27 de marzo de 2023] Available:https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/52951/OPSCDEHSSCOVID-19200037_spa.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Díez C, Del Romero-raposo J, Mican R, López JC, Blanco JR, Calzado S, et al. COVID-19 in hospitalized HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients: A matched study. HIV Med. 2021; 22:867-876. [CrossRef]

- Karmen-Tuohy S, Carlucci PM, Zacharioudakis IM, Zervou FN, Rebick G, Klein E, et al. Outcomes among HIV-positive patients hospitalized with COVID-19. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2020;85:6–10. [CrossRef]

- Marzo-Castillejo M, Guiriguet Capdevila C, Coma Redon E. Retraso diagnóstico del cáncer por la pandemia COVID-19. Posibles consecuencias. Aten Primaria. 2021; 53. [CrossRef]

- Del Amo J, Polo R, Moreno S, Jarrín I, Hernán MA. SARS-CoV-2 infection and coronavirus disease 2019 severity in persons with HIV on antiretroviral treatment. AIDS. 2022; 36:161-168. [CrossRef]

- Park LS, Rentsch CT, Sigel K, Rodríguez-Barradas M, Brown ST, Goetz MB, et al. COVID-19 in the largest US HIV cohort. IAC2020; 2020 [May 14th 2022]. Available online: https://www.natap.org/2020/IAC/IAC_115.htm#:~:text=Over%20a%2078%2Dday%20period,CI%3A%200.85%2D1.26.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).