Submitted:

17 April 2023

Posted:

17 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Geology of Nyrdvomenshor deposit

3.2. Diopside and rodingite

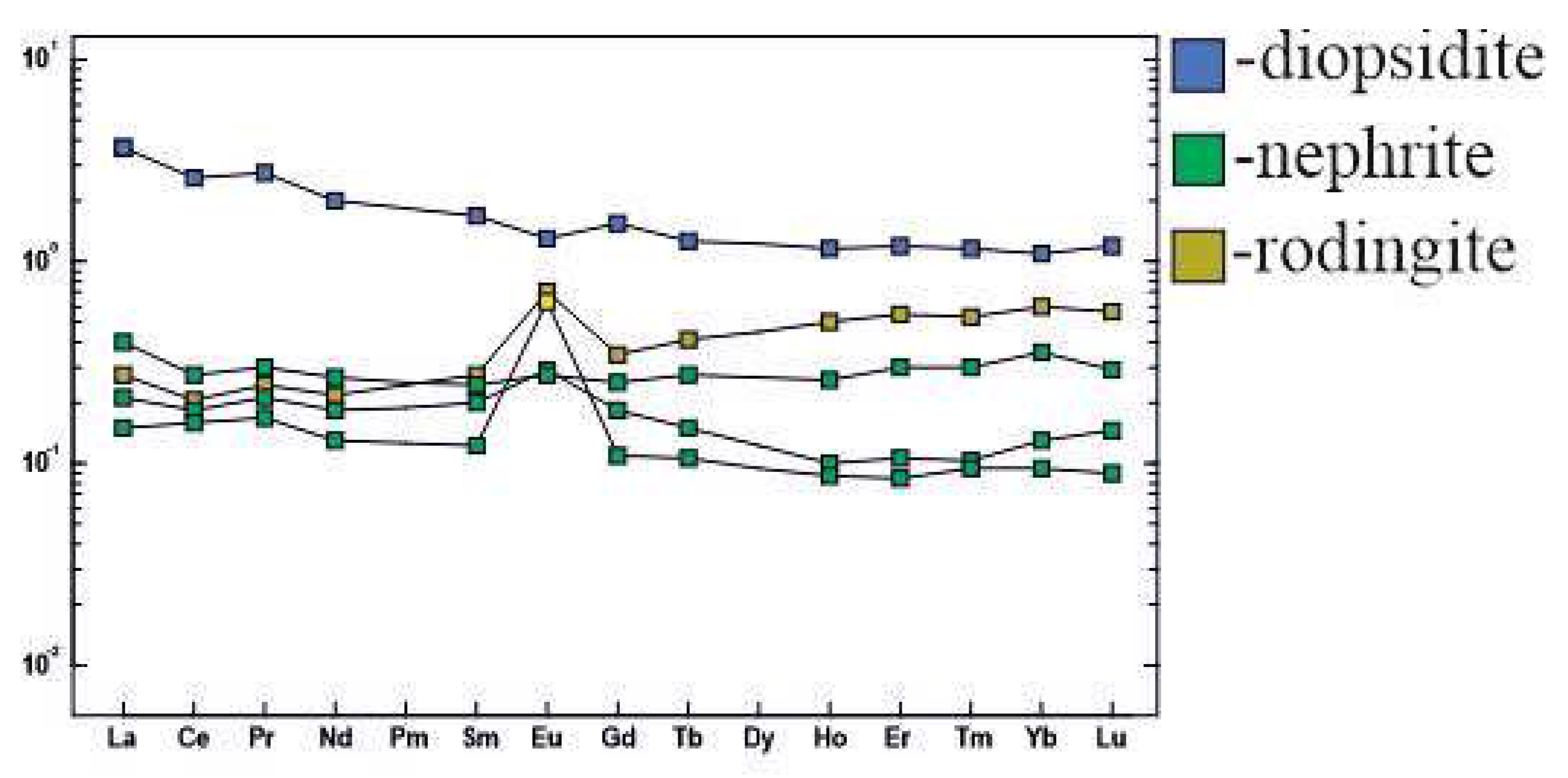

3.3. Characteristics of nephrite

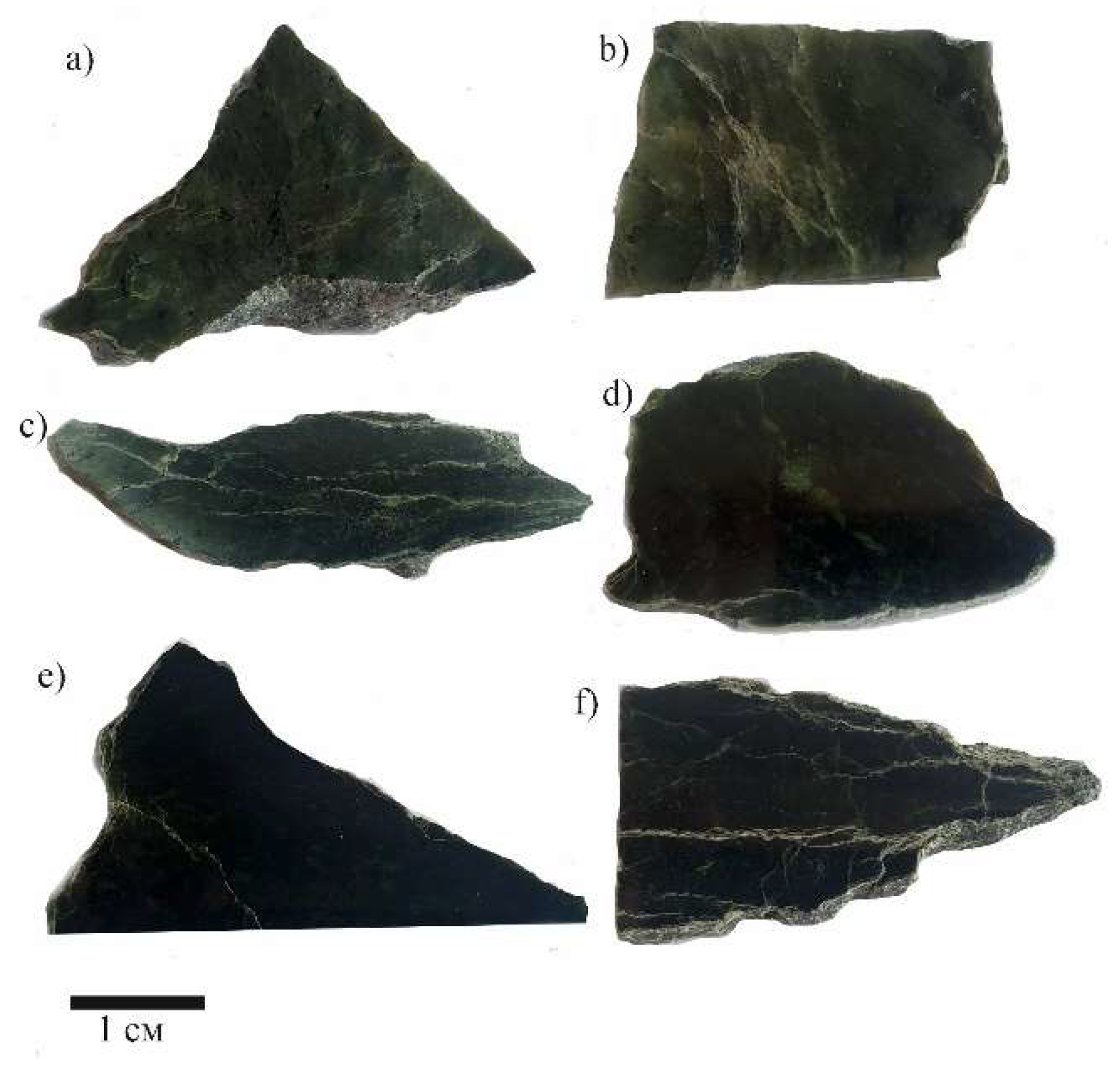

3.4. Mineral composition of nephrite

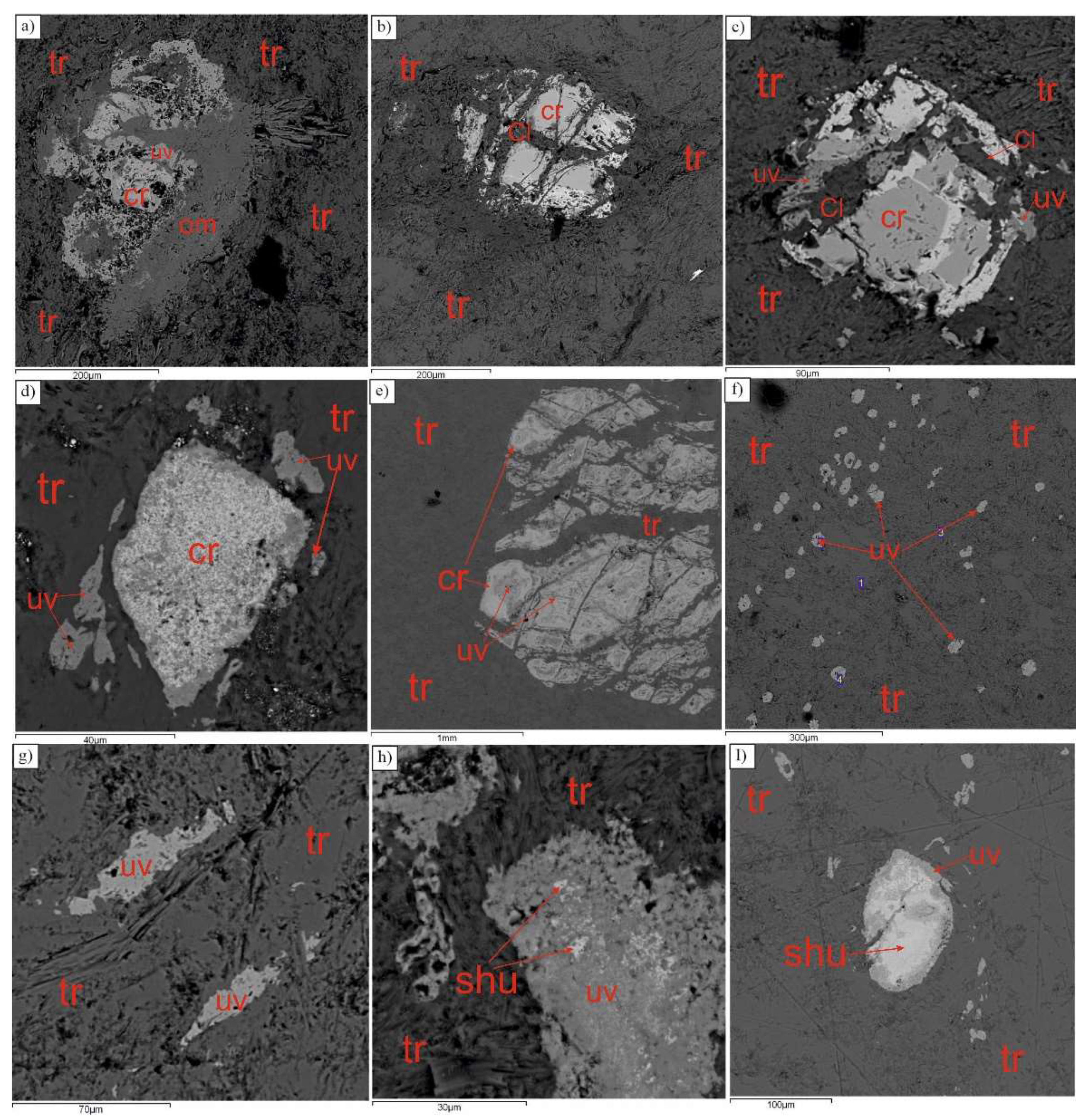

3.5. Isotope composition of the rocks

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kievlenko, E.Y. Geology gems. Ocean Pictures Ltd.: Littleton CO, USA. 2003, 468 p.

- Harlow, G.E.; Sorensen, S.S. Jade (Nephrite and Jadeitite) and Serpentinite: Metasomatic Connections. Int. Geol. Rev. 2005, 47, 113–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Liao, Z.; Qi, L.; Zhou, Zh. Black nephrite jade from Guangxi, Southern China. Gems Gemol. 2019, 55, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-D.; Yang, R.-D.; Gao, J.-B.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.-N.; Zhou, Z.-R. Geochemical characteristics of nephrite from Luodian County, Guizhou Province, China. Acta Mineral. Sinica 2015, 35, 56–64, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Flint, D.J.; Dubowski, E.A. Cowell jade province: detailed geological mapping and diamond drilling of jade and ornamental marble outcrops, 1982-1987. Department of mines and energy of South Australia. Rept. Bk. No. 89/51. Dme No. 85/88. 1991. V. 2. 98 p. V. 3. 26 p. V. 4. 29 p.

- Tan, T.L.; Ng, L.L.; Lim, L.C. Studies on Nephrite and Jadeite Jades by Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) and Raman Spectroscopic Techniques. Cosmos 2013, 9, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, G. Comparative Study on the Origin and Characteristics of Chinese (Manas) and Russian (East Sayan) Green Nephrites. Minerals 2021, 11, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, R.; Guo, J.; Li, J.; Yang, X. Study of the minerogenetic mechanism and origin of Qinghai nephrite from Golmud, Qinghai, Northwest China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2016, 59, 1597–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yu, X.; Yang, F.; Santosh, M.; Huo, D. Petrology and geochronology of the Yushigou nephrite jade from the North Qilian Orogen, NWChina: Implications for subduction-related processes. Lithos 2021, 380–381, 105894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.X.; Lu, B.Q.; Qi, L. J. A petromineralogical and SEM microstructural analysis of nephrite in Sichuan Province. Shanghai Land and Resour. 2015, 36, 87–89, (in Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, F.; Yu, X.; Liu, J.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Chi, J.; Zhang, P. Spatial-temporal distribution, metallogenic mechanisms and genetic types of nephrite jade deposits in China. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1047707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.M.; Yeh, C.L. Uvarovite and grossular from the Fengtien nephrite deposits, Eastern Taiwan. Mineral. Mag. 1984, 48, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yui, T.-F.; Yeh, H.-W.; Lee, C.W. Stable isotope studies of nephrite deposits from Fengtien, Taiwan. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1988, 52, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yui, T.F.; Usuki, T.; Chen, C.Y.; Ishida, A.; Sano, Y.; Suga, K. ; Iizuka, Y; Chen, C.T. Dating thin zircon rims by NanoSIMS: The Fengtien nephrite (Taiwan) is the youngest jade on earth. Int. Geol. Rev. 2014, 56, 1932–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, Z.A.; Liaqat, U.; Ahmed, R.; Baig, M.A. Classification of Nephrite Using Calibration-Free Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (CF–LIBS) with Comparison to Laser Ablation–Time-of-Flight–Mass Spectrometry (LA–TOF–MS). Anal. Letters 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obiadi, S.S.; Amini, M.A.; Fazli, F. Mineralogy and Geochemistry of Nephrite from Wolay Deposite, Kunar, East Afghanistan. J. Mechanical, Civil and Industrial Engineering 2022, 3, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.U. ; Bilal; Owais, O.; Rahman, O.U; Shen A.H. Namak Mandi: a pioneering gemstone market in Pakistan. Gems Gemol. 2021, 57, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.A.; Anwar-ul-Haq, M. , Qasim M., Afgan M.S., Haq S.U., Hussain S.Z. Spectroscopic and crystallographic analysis of nephrite jade gemstone using laser induced breakdown spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and X-ray diffraction. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suturin, A.N.; Zamaletdinov, R.S.; Sekerina, N.V. Nephrite deposits. ISU press: Irkutsk, Russia. 2015. 377 p. (In Russian).

- Boyd, W.F.; Wight, W. Gemstones of Canada. J. Gemm. 1983, 18, 544–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simandl, G.J.; Riveros, C.P.; Schiarizza, P. Nephrite (Jade) Deposits, Mount Ogden Area, Central British Columbia (NTS 093N 13W). British Columbia Geological Survey. Geological Fieldwork 1999, Paper 2000-1. 2000. 339-347 pp.

- Jiang, B.; Bai, F.; Zhao, J. Mineralogical and geochemical characteristics of green nephrite from Kutcho, northern British Columbia, Canada. Lithos 2021, 388–389, 106030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J. A Unique Occurrence of Nephrite Jade with Magnetite Inclusions in San Bernardino County, California. Rocks Miner. 2021, 96, 442–449 doiorg/101080/0035752920211901208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, G.; Barnes, J.D.; Boschi, C.; Gunia, P.; Szakmany, G.; Bendo, Z.; Raczynski, P.; Peterdi, B. Origin of serpentinite-related nephrite from Jordanów and adjacent areas (SW Poland) and its comparison with selected nephrite occurrences. Geol. Quarterly 2015, 59, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobos, K.; Sachanbinski, M.; Pawlik, T. Nephrite from Naslawice in Lower Silesia (SW Poland). Przeglad Geologiczny (In Polish with English abstract). 2008, 56, 991–999. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, G.; Baginski, B.; Gunia, P.; Madej, S.; Sachanbinski, M.; Jokubauskas, P.; Belka, Z. Comparative Fe and Sr isotope study of nephrite deposits hosted in dolomitic marbles and serpentinites from the Sudetes, SW Poland: Implications for Fe-As-Au-bearing skarn formation and post-obduction evolution of the oceanic lithosphere. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 118, 103335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.J.; Beck, R.J.; Campbell, H.J. Characterisation and origin of New Zealand nephrite jade using its strontium isotopic signature. Lithos 2007, 97, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.F. Origin and evolution of nephrites, diopsidites and giant diopside crystals from the contact zones of the Pounamu Ultramafics, Westland, New Zealand. New Zealand J. Geol. Geophys. 2023, 66, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarling, M.S.; Smith, S.A.F.; Negrini, M.; Kuo, L.-W.; Wu, W.-H.; Cooper, A.F. An evolutionary model and classification scheme for nephrite jade based on veining, fabric development, and the role of dissolution–precipitation. Sci. Reports 2022, 12, 7823. [CrossRef]

- Hockley, J.J. Nephrite (jade) Occurrence in the Great Serpentine Belt of New South Wales, Australia. Nature 1974, 247, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenraads, R.R. Gemstones of New South Wales. Austral. Gemmologist 1995, 19, 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Krotov, B.P. Petrographic description of the southern part of the Miass dacha // Society of Natural Scientists at Kazan University 1915, 47 (1), 402 p. (In Russian).

- Mamurovskiy, A.A. The nephrite deposit on Mount Bikilar. Litogea: Moscow, Russia, 1918. 52 p. (In Russian).

- Kazak, A.P.; Dobretsov, N.L.; Moldavantsev, Y.Е. Glaucophane shists, jadeites, vesuvianites and nephrites of the Rai-Iz hyperbasite massif. Geol. Geophys. 1976, 60–66. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Yushkin, N.P.; Ivanov, O.K.; Popov, V.A. Introduction to topomineralogy of the Urals. Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1986. 295 p. (In Russian).

- Kislov, E.V.; Erokhin, Y.V.; Popov, M.P.; Nikolayev, A.G. Nephrite of Bazhenovskoye Chrysotile–Asbestos Deposit, Middle Urals: Localization, Mineral Composition, and Color. Minerals. 2021, 11, 1227, 11. [CrossRef]

- Knyazev, Y.G.; Knyazeva, O.Y.; Snachev, V.I.; Zhdanov, A.V.; Karimov, T.R.; Aidarov, E.M.; Masagutov, R.Kh.; Arslanova, E.R. State Geological Map of the Russian Federation. Scale 1:1 000 000 (third generation). Ural Series. Sheet N-40 – Ufa. Explanatory note. VSEGEI Map Factory: Sankt-Petersbourg, Russia. 2013. 512 p. (In Russian).

- Aerov, G.D.; Zaryanov, K.B.; Samsonov, Ya.P.; Gil’mutdinov, G.Kh. Colored stones in the hyperbasites of Kazakhstan. In Geology, prospecting methods, exploration and evaluation of deposits of jewelry, ornamental and decorative facing stones. All-Union 6th productions association under the Ministry of Geology of the USSR: Moscow, Russia. 1975, pp.

- Arkhireev, I.E.; Maslennikov, V.V.; Makagonov, E.P.; Kabanova, L.Ya. South Ural nephrite province. Razvedka i okhrana nedr 2011, 18–22. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Makagonov, E.P.; Arkhireev, I.E. Nephrite of the Urals. Geoarchaeology and archaeological mineralogy 2014, 15–19. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Dobretsov, N.L.; Tatarinov, A.V. Jadeite and nephrite in ophiolites (the example of West Sayan). Nauka: Novosibirsk, Russia. 1983. 126 p. (In Russian).

- Gorbunova, N.P.; Tatarinova, L.A.; Kudyakova, V.S.; Popov, M.P. Wave X-ray fluorescence spectrometer XRF-1800 (SHIMADZU, Japan): method of determination of trace impurities in rubies. In: Yearbook-2014. Proceedings of IGG UrB RAS. 2015, 162, pp. 238-241. (In Russian).

- Sharp, Z.D. A laser-based microanalytical method for the in situ determination of oxygen isotope ratios of silicates and oxides. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1990, 54, 1353–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakhrusheva, N.V.; Shiryaev, P.B.; Stepanov, A.E.; Bogdanova, A.R. Petrology and chromite content of the Rai-Iz ultrabasic massif (Polar Urals). IGG UrB RAS: Ekaterinburg, Russia. 2017. 265 p. (In Russian).

- Sychev, S.N.; Kulikova, K.V. The sequence of deformations in the frame of the Rai-Iz massif (Polar Urals). Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Series 7. 2012, 53–59. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Siqin, B.; Qian, R.; Zhou, S.J.; Gan, F.X.; Dong, M.; Hua, Y.F. Glow discharge mass spectrometry studies on nephrite minerals formed by different metallogenic mechanisms and geological environments. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2012, 309, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grapes, R.H.; Yun, S.T. Geochemistry of a New Zealand nephrite weathering rind. N. Z. J. Geol. Geophys. 2010, 53, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Deng, J.; Shi, G.; Yui, T.-F.; Zhang, G.; Maituohuti, A.; Yang, L.; Sun, X. Geochemistry and petrology of nephrite from Alamas, Xinjiang, NW China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2011, 42, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostov, R.I.; Protochristov, C.; Stoyanov, C.; Csedreki, L.; Simon, A.; Szikszai, Z.; Uzonyi, I.; Gaydarska, B.; Chapman, J. Micro-PIXE geochemical fingerprinting of nephrite neolithic artifacts from Southwest Bulgaria. Geoarchaeology. 2012, 27, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtseva, M.V.; Ripp, G.S.; Posokhov, V.F.; Murzintseva, A.E. Nephrites of East Siberia: geochemical features and problems of genesis. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2015, 56, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-F.; Zhang, H.-Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. ; Li, Z-J.; Zhang, J.-H.; Zheng, F. Mineralogical characteristics and genesis of green nephrite from the world. Rocks Mineral Anal. 2018, 37, 479–489, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yui, T.-F.; Kwon, S.-T. Origin of a Dolomite-Related Jade Deposit at Chuncheon, Korea. Econ. Geol. 2002. 97, 593–601. [CrossRef]

- Sychev, S.N. Structure and evolution of the Main Ural Fault zone (southern part of the Polar Urals). Abstract of Kandidate (equal to PhD) Thesis. Geological Institute of Russian Science Academy, Moscow. 2015. 24 p. (In Russian).

| SiO2 | TiO2 | Al2O3 | Cr2O3 | FeO | Fe2O3 | MnO | MgO | CaO | Na2O | NiO | ZnO | V2O3 | ∑ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| diopside (14) | ||||||||||||||

| Min | 52.86 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.38 | 0 | 0 | 11.67 | 20.85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 98.29 |

| Max | 57.44 | 0.35 | 1.70 | 0.63 | 12.43 | 0.10 | 0.58 | 17.96 | 24.95 | 1.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 101.95 |

| garnet (11) | ||||||||||||||

| Min | 35.62 | 0.90 | 0 | 6.23 | 0.90 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29.58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 98.07 |

| Max | 37.91 | 3.12 | 10.68 | 19.83 | 4.35 | 20.27 | 0.58 | 3.42 | 34.08 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 101.45 |

| tremolite (4) | ||||||||||||||

| Min | 55.49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.05 | - | 0 | 11.92 | 12.41 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 95.43 |

| Max | 58.85 | 0.38 | 3.95 | 0 | 4.43 | - | 0.56 | 22.07 | 18.19 | 3.79 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 98.82 |

| chlorite (3) | ||||||||||||||

| Min | 32.86 | 0 | 6.97 | 0.64 | 6.64 | - | 0 | 28.31 | 0.27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 84.44 |

| Max | 34.38 | 0 | 15.17 | 4.90 | 9.16 | - | 0 | 31.77 | 0.99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 86.91 |

| titanite (2) | ||||||||||||||

| 32.08 | 38.60 | 0.74 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 27.49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 98.91 | |

| 32.41 | 39.45 | 0.59 | 0 | 0.58 | - | 0 | 27.76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.79 | |

| chromite (7) | ||||||||||||||

| Min | 0 | 0 | 12.17 | 39.07 | 12.49 | 1.40 | 0 | 2.28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 98.56 |

| Max | 0 | 0.42 | 28.40 | 58.75 | 29.56 | 7.09 | 1.08 | 15.55 | 0 | 0 | 3.21 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 101.39 |

| ilmenite (1) | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | 51.28 | 0 | 0 | 43.30 | - | 3.67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 98.24 | |

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | FeO | MgO | CaO | ∑ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| grossular (5) | |||||||

| Min | 34.00 | 19.78 | 0 | 36.17 | 0 | 90.69 | |

| Max | 37.40 | 22.20 | 0.74 | 38.13 | 0 | 97.68 | |

| chlorite (5) | |||||||

| Min | 24.62 | 18.31 | 2.97 | 21.23 | 0 | 83.17 | |

| Max | 31.13 | 25.32 | 16.52 | 31.54 | 0 | 84.46 | |

| vesuvianite (4) | |||||||

| Min | 34.06 | 16.16 | 2.80 | 2.16 | 34.24 | 91.14 | |

| Max | 36.24 | 16.67 | 3.04 | 2.65 | 36.28 | 94.13 | |

| nephrite | diopsidite | rodingite | |||

| SiO2 | 58.17 | 58.44 | 56.35 | 52.83 | 33.70 |

| TiО2 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| Al2O3 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.66 | 0.40 | 19.48 |

| Fe2O3∑ | 5.07 | 4.87 | 5.88 | 8.13 | 5.19 |

| MnO | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.04 |

| MgO | 21.70 | 21.68 | 21.49 | 16.42 | 10.91 |

| CaO | 12.57 | 12.06 | 13.04 | 21.40 | 28.80 |

| Na2O | 0.15 | 0.48 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| K2O | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| P2O5 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0 |

| S | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0 |

| Cr | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| LOI | 1.87 | 2.03 | 2.36 | 0.57 | 1.78 |

| ∑ | 100.09 | 100.26 | 100.42 | 100.20 | 100.08 |

| Li | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 14 |

| Be | 0.11 | 0.2 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.013 |

| Sc | 2.8 | 3.7 | 6 | 5 | 12 |

| Ti | 40 | 40 | 60 | 210 | 110 |

| V | 15 | 15 | 16 | 21 | 26 |

| Cr | 400 | 440 | 700 | 380 | 70 |

| Mn | 340 | 400 | 380 | 380 | 170 |

| Co | 21 | 24 | 24 | 18 | 14 |

| Ni | 400 | 400 | 400 | 200 | 60 |

| Cu | 4 | 4 | 9 | 11.5 | 4 |

| Zn | 14 | 15 | 20 | 9 | 6 |

| Ga | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 3 |

| Ge | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.6 | 0.34 |

| As | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 |

| Se | 0.17 | 0.2 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.45 |

| Rb | 0.5 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.33 |

| Sr | 33 | 29 | 50 | 40 | 27 |

| Y | 0.17 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.8 |

| Zr | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.8 |

| Nb | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.4 | 0.08 |

| Mo | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.6 | 0.29 |

| Ag | 0.0117 | 0.0111 | 0.0072 | 0.019 | 0.008 |

| Cd | 0.025 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Sn | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.2 | 0.32 | 0.21 |

| Sb | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.4 | 0.09 |

| Te | < 0.01 | 0.019 | < 0.01 | 0.017 | < 0.01 |

| Cs | 0.04 | 0.012 | 0.027 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Ba | 5.4 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 4.7 |

| La | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 1.2 | 0.09 |

| Ce | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 2.3 | 0.18 |

| Pr | 0.019 | 0.024 | 0.033 | 0.31 | 0.027 |

| Nd | 0.078 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 1.2 | 0.13 |

| Sm | 0.022 | 0.036 | 0.044 | 0.3 | 0.049 |

| Eu | 0.043 | 0.02 | 0.019 | 0.09 | 0.049 |

| Gd | 0.027 | 0.046 | 0.063 | 0.38 | 0.087 |

| Tb | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.013 | 0.06 | 0.019 |

| Dy | 0.028 | 0.038 | 0.08 | 0.38 | 0.15 |

| Ho | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.018 | 0.08 | 0.035 |

| Er | 0.017 | 0.021 | 0.059 | 0.24 | 0.11 |

| Tm | 0.0028 | 0.0031 | 0.009 | 0.035 | 0.016 |

| Yb | 0.019 | 0.026 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.12 |

| Lu | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.019 |

| Hf | 0.1 | 0.024 | 0.023 | 0.21 | 0.04 |

| Ta | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.037 | 0.11 | 0.045 |

| W | 0.3 | 0.26 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 3 |

| Tl | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.0025 | 0.0027 |

| Pb | 0.19 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Bi | 0.0142 | 0.0051 | 0.0033 | 0.019 | 0.0039 |

| Th | 0.08 | 0.018 | 0.011 | 0.3 | 0.018 |

| U | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.031 | 0.16 | 0.011 |

| SiO2 | TiO2 | Al2O3 | Cr2O3 | FeO | Fe2O3 | MnO | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | CoO | NiO | ZnO | V2O3 | Cl | F | ∑ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tremolite (35) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Min | 56.65 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.98 | - | 0 | 20.18 | 11.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 95.09 |

| Max | 59.99 | 0.35 | 0.66 | 0 | 4.80 | - | 0.37 | 23.45 | 13.75 | 0.85 | 0.51 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.40 | 1.48 | 99.90 |

| uvarovite (24) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Min | 33.93 | 0 | 0.43 | 12.32 | 0 | 0.47 | 0 | 0 | 30.80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 98.38 |

| Max | 37.87 | 2.53 | 9.31 | 22.01 | 3.33 | 14.48 | 1.28 | 2.72 | 34.73 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.26 | 0 | 0 | 101.90 |

| diopside (7) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Min | 53.98 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.98 | 0 | 0 | 14.33 | 21.97 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 98.26 |

| Max | 55.24 | 0.30 | 2.42 | 1.77 | 3.49 | 2.13 | 0.50 | 17.44 | 24.91 | 1.95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 102.00 |

| omphacite (10) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Min | 52.28 | 0 | 0.76 | 2.59 | 0.61 | 0 | 0 | 5.99 | 12.20 | 3.38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 98.08 |

| Max | 56.31 | 0 | 6.59 | 10.11 | 6.03 | 4.04 | 2.47 | 12.04 | 18.23 | 6.31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 101.92 |

| chlorite (5) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Min | 31.75 | 0 | 9.07 | 2.40 | 6.73 | - | 0 | 29.12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 84.14 |

| Max | 35.26 | 0 | 12.34 | 5.89 | 8.17 | - | 0 | 30.74 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 88.76 |

| “shuiskite” (6) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Min | 11.96 | 0 | 1.59 | 24.44 | 13.05 | - | 0.99 | 0 | 11.05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 97.79 |

| Max | 27.36 | 1.53 | 6.76 | 33.10 | 39.30 | - | 2.43 | 0.86 | 24.95 | 0.49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.57 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 103.46 |

| chromite (23) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Min | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40.38 | 11.24 | 1.38 | 0 | 0.66 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 99.28 |

| Max | 0 | 1.83 | 38.60 | 58.54 | 27.92 | 22.95 | 3.49 | 17.68 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 1.79 | 0.43 | 0 | 0 | 101.98 |

| № | Sample | Rock | δ18O, ‰ VSMOW |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 162 | diopsidite | 7.3 |

| 2 | 3/21 | diopsidite | 6.8 |

| 3 | hydrogarnet rodingite | 6.1 | |

| 4 | 558 | nephrite | 8.9 |

| 5 | 2/21 | nephrite | 8.6 |

| 6 | 510-1 | nephrite | 8.4 |

| 7 | 1/21 | nephrite | 8.2 |

| 8 | 61-2 | nephrite | 8.5 |

| 9 | 557-1 | nephrite | 9.7 |

| 10 | 66 | jadeite | 8.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).