Introduction

According to Alzheimer’s Disease International (

https://www.alzint.org/), dementia is an ever growing disease estimated to affect a total of 78 million people worldwide by 2030. This medical and social burden is likely to worsen, potentially reaching 139 million people affected by 2050. Because of the heterogeneity of dementia, the etiopathogenesis is not completely understood (Livingston et al. 2020) and there currently is no remedy available to treat the disease nor slow it down. Prevention remains the only possible strategy to tackle this global upward trend. It is estimated that 40% of known dementia causes are modifiable by simply addressing people’s lifestyle (Livingston et al. 2020). Of this 40%, dietary behaviour plays a crucial role lowering the risk of developing dementia (Livingston et al. 2020). For instance, adherence to a Mediterranean diet was observed to be protective against dementia supporting brain health and cognitive functions according to several studies (Black et al. 2020; Black et al. 2019 a; Black et al. 2019 b; Akbaralay et al. 2019; Radd-Vegenas et al. 2018; Loughrey et al. 2017; Barnard et al. 2014; Scarmeas et al. 2007). Healthy diet is crucial in providing the necessary nutrients for adequate physiological functioning. Indeed, it is documented how a poor dietary lifestyle can worsen cognitive functioning while negatively affecting brain health (reduced cognitive performances and exacerbated inflammation and neurodegeneration) (Zhao et al. 2018; Pacholko et al. 2019; Fan et al. 2021; Seidl et al. 2014; Boto et al. 2017; Curzio et al. 2020; Dickerson et al. 2020; Walton et al. 2022; Takado et al. 2020; Sato et al. 2021). Specifically, low protein and amino-acid dietary intake has been related to poor cognitive health and increased risk of dementia (Ikeuchi et al. 2022; Gao et al. 2022; Feng et al. 2022; Glenn et al. 2019; Kinoshita et al. 2021; Fan et al. 2021; Coelho-Júnior et al. 2021; Pacholko et al. 2019). This is possibly due to the lack of proper micro-nutrients and amino-acid supply needed for the appropriate biosynthesis of key neuromodulators which affect brain metabolism and cognitive functioning (Fernstrom 1977; Wurtman et al. 1980; Fernstrom 1981; Conley and Zeisel 1982; Wurtman 1983; Anderson and Johnston 1983; Wurtman 1987; Francis 2005; Kaur et al. 2019; May and Paxinos 2012).

The degradation of the neuromodulatory pathways, comprising the cholinergic (ACh), dopaminergic (DA), serotoninergic (5-HT) and noradrenergic (NA) systems, is widely observed in neurodegenerative diseases (Bondareff et al. 1982; Lyness et al. 2003; Ehrenberg et al. 2017; Braak et al. 2011; Jethwa et al. 2019; Bozzali et al. 2019; Braak et al. 2011; George t al. 2011; Aletrino et al. 1992). Since the well documented cholinergic decline in dementia, studies have investigated whether choline intake (precursor of Acethylcoline) would be related to better cognitive functioning and reduced neurodegeneration (Francis et al. 1999; Yuan et al. 2022; Ylilauri et al. 2019; Poly et al. 2011; Velazquez et al. 2019b; Spiers et al. 1996; Krashia et al. 2019). Consequently, choline intake was associated with reduced dementia risk observed through biomarkers of neurodegeneration, along with more preserved cognitive functioning in several studies both on healthy and demented populations (Velazquez et al. 2019a; Velazquez et al. 2019b; Yuan et al. 2022; Ylilauri et al. 2019; for review see: Hampel et al. 2019). Mechanistically these findings proposed the role of choline in diet as a potential modifiable factor to help prevent neurodegeneration and reduce the incidence of dementia.

However, a growing body of literature identifies the noradrenergic system, originating in the Locus Coeruleus (LC) as the main driver of neurodegenerative dynamics (Chen et al. 2022; Matchett et al. 2021; Brettschneider et al. 2015; Braak et al. 2011). Indeed, the LC is the earliest brain structure affected in Alzheimer’s disease (Chen et al. 2022; Brettschneider et al. 2015; Ehrenberg et al. 2017) showing early signs of neurodegeneration (Braak et al. 2011; Dahl et al. 2021) and characterising disease progression and staging (Braak et al. 2011; Andrés-Benito et al. 2017; Del Tredici & Braak 2020). The LC-NA system is critical for supporting broad integrative function across large scale brain networks to support attention and exploratory behaviour, and stands in contrast to cholinergic-mediated segregation of specific cognitive networks (Munn et al. 2021; Holland et al. 2021; Shine 2019; Aston-Jones and Waterhouse 2016; Aston-Jones et al. 1999). In the last decade, the integrity of the LC-NA system has been associated with greater brain and cognitive health (Wilson et al. 2013; Elman et al. 2021; Jacobs et al. 2021; Plini et al. 2021; Dahl et al. 2022), including better attentive and mnemonic functions both in healthy and clinical populations (Clewett et al. 2016; Dahl et al. 2019; Dahl et al. 2020; Dutt et al. 2021; Plini et al. 2021; Prokopiou et al. 2022). These findings are in line with consideration of the LC-NA system integrity serving as a potential in-vivo biomarker for neurodegenerative diseases (Betts et al. 2019; Giorgi et al. 2022), while being crucial for maintaining brain and cognitive health (Sarah 2009; Mather and Harley 2016; Holland et al. 2021), as was previously postulated by the “noradrenergic theory of cognitive reserve” proposed by Robertson (for details, see box1 and refer to Robertson 2013 & 2014).

Despite these relevant implications, and the central role of diet in dementia prevention, no studies to date have investigated a potential relationship between dietary behaviour and LC-NA system integrity and functioning in healthy adults. In light of the pre-existing literature on choline intake, we aimed to investigate in this study whether the intake of tyrosine (the precursors of NA synthesised in the LC) (May and Paxinos 2012; Matchett et al. 2021), could be related to greater LC integrity, and therefore better brain maintenance supporting higher-order cognitive functioning in healthy adults without cognitive impairment (Fernstron & Fernstrom 2007; Aliev et al. 2014; Andrés-Benito et al. 2017; Engelborghs et al. 2014; Kühn et al. 2019; Plini et al. 2021). Our main hypothesis was also based on the literature reporting how malnutrition can negatively impact on overall brain mass (including subcortical structure) and cognition (Roberts et al. 2012; Tynkkynen et al. 2018; Walton et al. 2022; Roberto et al. 2011; Titova et al. 2013), and how low amino-acids and protein intake was associated to increased neuro-inflammation and brain atrophy (Takado et al. 2020; Sato et al. 2021) suggesting that amino-acidic profile intake as an important factor to assess dementia risk (Ikeuchi et al. 2022; Feng et al. 2022; Glen et al. 2019).

Tyrosine (TYR) is an amino acid present in animal protein and serves as a principal precursor of catecholamine biosynthesis (Gardner et al. 2019; Ahmed et al. 2021; Chavez et al. 2017; -

http://www.ncc.umn.edu/ndsr-database-page/ - May and Paxinos 2012). In fact, throughout the ascending reticular arousal system (ARAS) (May and Paxinos 2012; Bucci et al. 2017), via the tyrosine hydroxylase enzyme (TH), tyrosine is converted to L-dopa, then, via the action of L-aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AAAD), to dopamine. Dopamine, via the action of the dopamine-β-hydroxylase enzyme (DBH) is subsequently converted to NA. NA is synthetised predominantly within the LC neurons. Finally, Adrenaline is obtained by the addition of a methyl group to noradrenaline by phenylethanolamine-N-methyltransferase (PNMT) within the adrenergic neurons of the Medulla oblongata (May and Paxinos 2012).

The concentrations of catecholamines varies depending on the availability of amino acid precursors and diet can affect concentrations in the central nervous system (Fernstron & Fernstrom 2007; Fernstrom 1977; Wurtman et al. 1980; Fernstrom 1981a; Fernstrom 1981b Conley and Zeisel 1982; Wurtman 1983; Anderson and Johnston 1983; Wurtman 1987; Francis 2005; Kaur et al. 2019). Protein intake stimulates biosynthesis because of the availability of precursors crossing the blood-brain barrier (Fernstron & Fernstrom 2007; Fernstrom 1977; Fernstrom 1981a; Conley and Zeisel 1982; Wurtman 1983; Wurtman et al. 1980; Pardridge 1998). Acute intake of amino acids like tyrosine is associated with increased concentrations of plasma catecholamines in humans and rodents (Agharayana et al. 1981; Rasmussen et al. 1983; Wurtman 1983; Lieberman et al. 1986; Sved et al. 1979; Choi et al. 2011).

Since administration of amino acid precursors have been associated with changes in behaviour and cognition (Lieberman et al. 1986; Lieberman et al. 1984; Leathwood & Pollet 1982), several studies investigating acute administration of tyrosine reported differences in cognitive performance. By administering between 2 and 12gr within 20–60 minutes before a variety of cognitive tests with or without cold exposure or military exercises, studies reported that tyrosine enhances or restores higher order cognitive functions relative to controls (Steenbergen et al. 2015; Colzato et al. 2014; Colzato et al. 2013; Mahoney et al. 2007; O’Brien et al. 2007; Magill et al. 2003; Thomas et al. 1999; Deijen et al. 1999; Neri et al. 1995; Deijen and Orlebeke 1994). Specifically, tyrosine induced greater working memory performance and greater cognitive control capabilities, domains typically associated with the LC-NA system (Holland et al. 2021; Mather and Harley 2016; Robertson 2013&2014; Sarah 2009; Munn et al. 2021; Aston-Jones and Waterhouse 2016; Aston-Jones et al. 1999). Remarkably, these effects were mostly appreciable under stressful conditions (i.e. cold exposure – while a comprehensive revision of this topic is beyond the scope of this work, for reviews please see Hase et al. 2015; Jongkeese et al. 2015; Attipoe et al. 2015).

This evidence inspired the concept that chronic dietary tyrosine intake might be associated with cognitive performances. The only study examining this hypothesis was carried out by Kühn and colleagues (Kühn et al. 2019). The authors assessed tyrosine intake with a self-report measure of habitual food intake (the “

food frequency questionnaire” -

https://dapa-toolkit.mrc.ac.uk/diet/subjective-methods/food-frequency-questionnaire - Boeing et al. 1997), and reported that greater dietary tyrosine intake was associated with better fluid intelligence, greater working memory scores and more accurate episodic memory, in a sample of 1724 healthy participants (old and young) from the Berlin Aging Study II – BASE-II (Bertam et al. 2014; Gestorf et al. 2016). This study also revealed that the association between habitual dietary tyrosine intake-daily average (HD-Tyr-IDA) and higher order cognitive performances was independent of age differences, and that cross-sectionally, both in young and old populations, the results were generalisable over the greater variation of cognitive performances between groups.

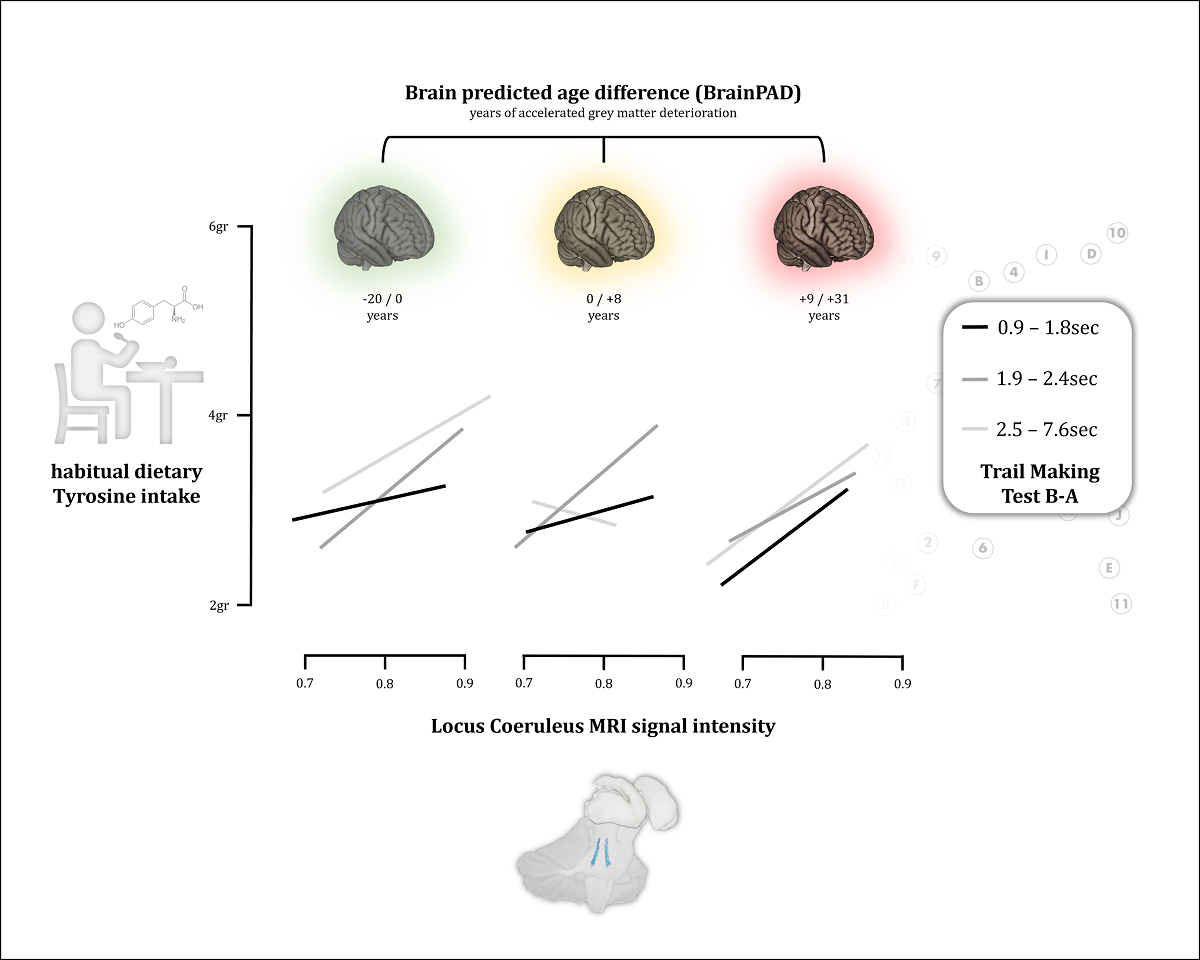

These findings informed the design of the current study, which utilises 398 high-resolution MRI scans available from a total of 1724 participants aiming at 1) investigating whether greater HD-Tyr-IDA is related to LC MRI integrity and 2) whether LC integrity mediates the reported association between tyrosine and better cognitive performance (Kühn et al. 2019; Hase et al. 2015; Jonkeese et al. 2015; Attipoe et al. 2015; Steenbergen et al. 2015; Colzato et al. 2016; Colzato et al. 2014; Colzato et al. 2013; Mahoney et al. 2007; O’Brien et al. 2007; Magill et al. 2003; Thomas et al. 1999; Deijen et al. 1999; Neri et al. 1995; Deijen and Orlebeke 1994). In addition, since higher order cognitive functions have been associated with better brain maintenance (Plini et al. 2021; Boyle et al. 2021; Boyle et al. 2020; Habeck et al. 2016; Löwe et al. 2016; Gaser et al. 2013) we hypothesised that greater HD-Tyr-IDA could be associated with better brain maintenance, measured using BrainPAD developed by Boyle et al. 2020 (Brain Predicted Age Difference – BrainPAD – for details, see box2 and refer to Boyle et al. 2020). Therefore, a third aim 3) is to test whether greater HD-Tyr-IDA relates to better BrainPAD scores and if this relationship is mediated by LC integrity. Lastly, a fourth aim 4) is to replicate the association between LC integrity and BrainPAD observed by Plini et al. 2021 (Plini et al. 2021).

Box 1 – The Noradrenergic Theory of Cognitive Reserve

The noradrenergic theory of cognitive reserve by Robertson (Robertson 2013 & 2014) postulates that the continuous activation (and the related integrity) of the Locus Coeruleus (LC)–noradrenergic system could be a key component affecting cognitive reserve and resilience to neurodegenerative diseases. Unifying the heterogeneous literature and considering the marked LC-NA degeneration in neurodegenerative diseases (Chen et al. 2022; Matchett et al. 2021; Brettschneider et al. 2015; Mather et al. 2016; Braak et al. 2011). Robertson identifies the neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties of NA as a crucial driver for maintaining brain and cognitive health (Robertson 2013&2014; Heneka et al. 2002; Heneka et al. 2015; Troadec et al. 2005; Feinstain et al. 2002; Counts et al. 2010; Hassani et al. 2020; Traver et al. 2005; Mannari et al. 2008; Omulabi et al. 2021; for review see: Giorgi et al. 2020, Matchett et al. 2021 and Mather 2021). This model suggests that the continuous life-time stimulation of the LC-NA system, via cognitive engagement, novelty exposure and other activities, may lead to greater LC-NA integrity and metabolism while supporting physiological and cognitive functions because of the beneficial effect of optimal NA activity across the nervous system. This continuous moderate noradrenergic activation would serve as a neurobiological substrate, building stronger resilience in the face of neurodegenerative dynamics. In this study, we conceived tyrosine intake as a parameter capable to stimulate/up-regulate (or support) the LC-NA system in accordance with previous evidence. Indeed, as described in the introduction, acute administration of tyrosine leads to an increase in catecholamines, in particular NA concentrations (Sved et al. 1979; Agharayana et al. 1981; Rasmussen et al. 1983; Wurtman 1983; Lieberman et al. 1986) while influencing higher order cognitive functioning (Lieberman et al. 1986; Lieberman et al. 1984; Leathwood & Pollet 1982; Kühn et al. 2019; Hase et al. 2015; Jonkeese et al. 2015; Attipoe et al. 2015; Steenbergen et al. 2015; Colzato et al. 2016; Colzato et al. 2014; Colzato et al. 2013; Mahoney et al. 2007; O’Brien et al. 2007; Magill et al. 2003; Thomas et al. 1999; Deijen et al. 1999; Neri et al. 1995; Deijen and Orlebeke 1994). Accordingly, in the context of this work, we hypothesized that tyrosine intake would be beneficial for keeping adequate physiological activity of LC-NA system through adequate NA supply provided by tyrosine.

Box 2 – Brain Predicted Age Difference

Brain Predicted Age Discrepancy (BrainPAD), calculated here using the method of Boyle and colleagues (Boyle et al. 2020), is an objective measure reflecting how the brain is ageing. BrainPAD compares an individual’s structural brain health, reflected by voxel-wise grey matter intensity, to the state typically expected at that individual’s age. Therefore, higher discrepancies between the biological brain age and chronological age are indices of abnormal ageing . Namely, greater BrainPAD scores reflect accelerated biological aging processes while negative scores mirror slower aging, a younger brain better maintained. BrainPAD is considered an index of brain maintenance contributing to Reserve (Boyle et al. 2020; Cabeza et al. 2018; Barulli et al. 2013).

Data

Cognitive and neuro-imaging data of younger and older participants were collected at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development (Berlin, Germany) at two time points (T1 and T2) between 2013 and 2016. The study is part of the Berlin Aging Study II (BASE-II) (Bertam et al. 2014; Gestorf et al. 2016 -

https://www.mpib-berlin.mpg.de/research/research-centers/lip/projects/aging/base-ii). On average, data acquisitions were 2.21 years apart (standard deviation (

SD) = 0.52, range = 0.9–3.2). Neuro-imaging data were collected on separate occasions at each time point (mean interval = 9.16 days,

SD = 6.32, range = −2–44; for T2). Data for this study is based on the previous work of Kühn and colleagues (Kühn et al. 2019) and included anonymised MRI images of 398 healthy participants at time point 1 (249 males – 149 females; age range 24 – 38 [n. 81] and 61 – 81 [n. 317]) and 291 subjects at time point 2 approximately three years later, between 1 and 4 years (in average 4.09 years for the old group and 3.79 for the young group. For T2 in total were considered 190 males – 101 females; age range 25 – 40 (n. 54) and 62 – 83 (n. 237).

MRI, Neuropsychological, cognitive and Nutritional Assessments

At T1 participants of BASE-II underwent a neuropsychological assessment (CERAD plus) examining a variety of domains, in the current study we focused on the following measures: Mini-Mental Sate Examination (MMSE) to account for broad cognitive functioning, Trail Making Test A; B and B minus A (TMT-A; TMT-B; TMT-B-A) to consider visuospatial attention and cognitive control. Moreover, we also included cognitive measures of spatial working memory (Spatial Update – SU - Schmiedek et al. 2010), fluid intelligence (practical problem solving - PP - Lindenberger et al. 1993) and finally episodic memory assessed by the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) at immediate and delayed (20min later) recall. All these measures were selected since they are typically associated with LC-NA function. For further details please refer to Kühn and colleagues (Kühn et al. 2019) and Duzel and colleagues (Duzel et al. 2016).

The nutritional assessment was carried out at T1 using the “

food frequency questionnaire” FFQ -

https://dapa-toolkit.mrc.ac.uk/diet/subjective-methods/food-frequency-questionnaire - Boeing et al. 1997). This questionnaire developed by the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC -

https://epic.iarc.fr/) assesses the habitual daily intake of 148 different kinds of food covering a period of 12 months before the questionnaire administration. From this measure Kühn and colleagues (Kühn et al. 2019), referring to the values provided by a federal coding system, extracted the habitual dietary intake-daily average (HD-Tyr-IDA) from regular diets and each food-item of the FFQ (for further details please refer to Kühn and colleagues - Kühn et al. 2019). Kühn and colleagues also calculated the habitual dietary total food intake-daily average (HD-TF-IDA), and more specifically the habitual dietary carbohydrates intake-daily average (HD-Car-IDA), the habitual dietary fat intake-daily average (HD-Fat-IDA), the habitual of protein intake-daily average (HD-Pro-IDA) and the habitual dietary water intake-daily average (HD-Wat-IDA). In addition, they also provided body mass index (BMI), body weight, height and waist circumference of 330 participants (24 females and 45 males were missing, 50 within the old group and 18 within the young group). In the current study we used the above mentioned nutritional scores without any additional interference.

MRI protocols of T1 included a variety of structural MRI sequences. In the current study we only used de-faced high-resolution 3T structural MPRAGE scans of 398 subjects and 291 subjects of T2. For further information, please refer to (Bertam et al. 2014; Gestorf et al. 2016 -

https://www.mpib-berlin.mpg.de/research/research-centers/lip/projects/aging/base-ii). Time point 2 assessment was carried out roughly 3 years after time point 1 and did not include FFQ and TMT. Images from T2 are used only for exploratory analyses described in the following sections and reported in supplementary materials.

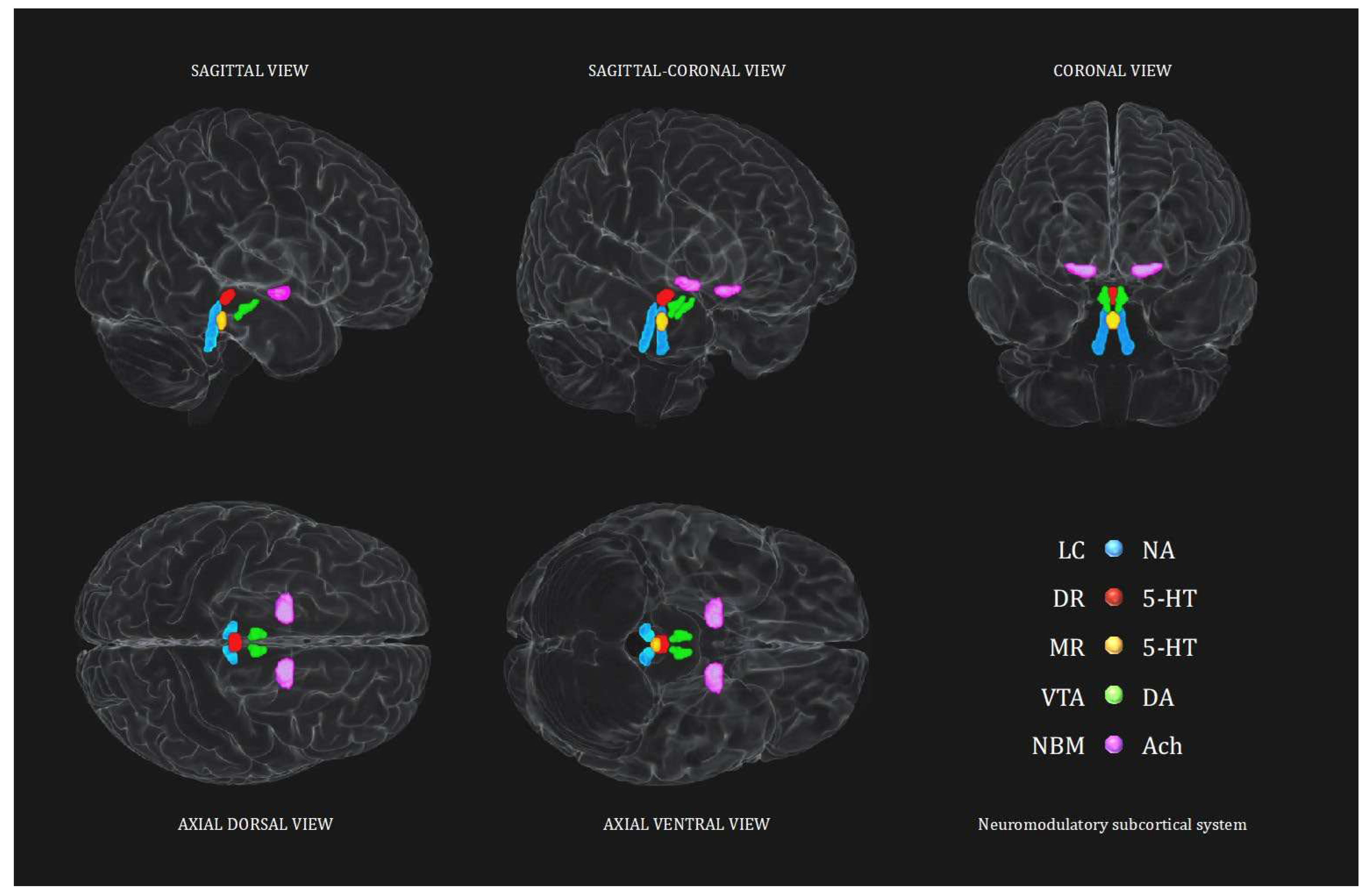

Neuromodulatory subcortical system – Control analyses

In order to better evaluate the sensitivity of this study, control analyses are implemented for each of the four aims described. Analyses investigating the noradrenergic hypothesis, are repeated testing the other main neuromodulatory subcortical nuclei projecting to the cortex. Namely the Dorsal Raphe (DR) and the Median Raphe (MR) for the serotoninergic system (5-HT), the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) for the dopaminergic system (DA) and the Nucleus Basalis of Meynert (NBM) for the cholinergic system (ACh). This procedure was further implemented by testing also the opposite relationship hypothesized, for each of the five seeds of the neuromodulatory subcortical system to further consider alternative hypothesis to LC-NA system involvement and directionality.

Neuromodulatory subcortical system ROI definition

As the brain scans, all the ROIs were oriented in the Montreal Neurological Institute – MNI coordinates space. In order to examine LC-NA system integrity in relation to HD-Tyr-IDA, the current study used the “omni-comprehensive” LC MRI mask developed in our previous work (Plini et al. 2021), which resolves inconsistent LC spatial localization reported in previous works (Keren et al. 2009 & 2015; Tona et al. 2017; Betts et al. 2017; Dahl et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2019; Rong Ye et al. 2020; Dahl et al. 2021; García-Gomar et al. 2022) without encroaching other pontine and cerebellar regions, and without crossing the walls of the 4

th ventricle (further details can be found in supplementary materials of Plini et al. 2021 and visualized in 3D at this link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=90bsA6Jqxs4). To contrast the noradrenergic hypothesis with other main neuromodulatory subcortical systems, the principal nuclei projecting to the cortex were isolated using previously published atlases. Specifically, the MR and DR ROIs were provided by Beliveau et al. (2015), and the VTA mask was obtained by downloading the MNI VTA probabilistic map from the atlas made by Pauli et al. (2018) from the NeuroVault website (

https://neurovault.org/collections/3145/ accessed on 15 December 2018). The NMB was developed on the basis of the probabilistic MNI maps of the acetylcholine cells of the forebrain, which are provided by Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) Anatomy Toolbox 2.2c (

https://www.fzjuelich.de/inm/inm1/EN/Forschung/_docs/SPMAnatomyToolbox/SPMAnatomyToolbox_node.html accessed on 15 December 2018) by Zaborszky et al. 2008 and George et al. 2011, Schulz et al. 2018, Liu et al. 2015, Kilimann et al. 2014, Koulousakis et al. 2019). Furthermore, an MNI 4

th ventricle mask was designed voxel by voxel in order to control for 4

th ventricle signal variations in the analyses (see the aforementioned link to visualize the mask). All the ROIs, including the 4

th ventricle mask, had 1mm3 voxel size and were oriented in the MNI space within a matrix size field of view (FOV) of 181x217x181 (the same of the processed images outcoming from the Computational Anatomy Tollbox 12 (CAT12). For further information and a more detailed rationale please refer to Plini et al. 2021 (Plini et al. 2021).

Figure 1 shows the 3D spatial reconstruction of the five ROIs.

BrainPAD calculation

Brain Predicted Age Discrepancy (BrainPAD), calculated here using the method of Boyle and colleagues (Boyle et al. 2020), is an objective measure reflecting how the brain is ageing.

It is similar to the previously developed indices such as Brain Gap Estimation—BrainAGE by Gaser et al. 2013, but it is computed only considering grey matter rather than white (WM) and grey matter (GM) together since GM was linearly associated with aging (Ge et al. 2002; Boyle et al. 2020). BrainPAD is obtained by calculating the discrepancy between the chronological age and the biological age of the brain defined on a healthy brain ageing trajectory of typical subjects. Boyle and colleagues defined the normal trajectory of GM ageing in healthy subjects. Then, they trained an algorithm to predict the degree of GM deterioration in relation to the chronological age in a three further populations of healthy individuals. The current study followed the process described in Boyle et al. 2020 with the aim of replicating and extending the findings reported in Plini et al. 2021, where LC integrity was related to better brain maintenance (lower BrainPAD scores) across 686 participants, both healthy controls, mild cognitive impairments and demented subjects.

MRI processing

De-faced 3T high-resolution T1-weighted MRIs in Nifti format were processed using CAT12 (

http://www.neuro.uni-jena.de/cat/) implemented in SPM12. The segmentation was run following the default CAT12 settings, except for the voxel size that was settled at 1mm isotropic voxel size. All the 398 images of time point 1 and the 291 images of time point 2 were classified above 80% by CAT12 quality rating (grade B on a scale of: A – Excellent; B- Good; C- Satisfactory; D- Sufficient; E- Critical; F- Unacceptable/Failed). Only four images were classified as satisfactory (C) and only one as Sufficient (D). These five images were kept since brainstem structures were not affected by excessive blurriness or motion and/or reconstruction artifacts. Lastly, to better account for individual volumetric variability in the Voxel Based Morphometry (VBM) analyses, the Total Intracranial Volume (TIV) was calculated for each participant using CAT12 interface (Statistical Analyses – Estimate TIV).

Voxel-Based Morphometry Analyses (VBM)

VBM analyses were performed using the CAT12 processed and unsmoothed whole brain images, Grey Matter (GM) + white matter (WM) considered together (not segmented). In CAT12, VBM multiple regression models were built in order to assess the main relationship between LC-NA system integrity and HD-Tyr-IDA and BrainPAD.

At time point one, the first model treating TIV, age, gender, education and total food intake as covariates, examined the relationship between LC signal intensity and HD-Tyr-IDA in keeping with the main hypothesis. As control procedure, the same model was repeated considering the DR, MR, VTA and NMB, testing the same relationship with HD-Tyr-IDA in order to contrast the noradrenergic hypothesis against the other main neuromodulatory systems. As an additional control procedure, the opposite (negative) relationships were tested to account for directionality other than hypothesized. In total the first model was contrasted against nine alternative hypotheses. The same procedure was repeated at time point two on 291 participants by using all the covariates of time point two with the only exception of HD-Tyr-IDA which was taken 3 years before. This was the only analysis performed at time point two. Later, the model was repeated by covarying also for the 4th ventricle to account for possible local age-related ventricle enlargement which may partially affect the magnitude of the results, fiven LC’s location adjacent to the fourth ventricle. Moreover, the same model was repeated without isolating the LC with the Plini et al. 2021 mask, but by including the whole Pons in order to gauge for larger regional variation. (This last model together with time point two and 4th ventricle analyses are reported in the supplementary materials).

To further increase control procedures, additional VBM multiple regression models were built to test the relationship between LC-NA system integrity and average macronutrients and water intake (control analyses on macro-nutrients). Namely, by covarying for TIV, age, gender, education and HD-TF-IDA, four different models examined LC signal intensity in relationship with HD-Fat-IDA, HD-Car-IDA, HD-Pro-IDA, HD-Wat-IDA. This additional practice aimed to strengthen the reliability of findings enabling a broader understanding of the data. By doing so, the first model was contrasted with four alternative hypotheses for a total of 21 antithetic VBM analyses.

The second model investigated the relationship between LC signal intensity and BrainPAD in order to replicate and extend the findings reported in Plini et al. 2021. The same multiple regression model was built, and controlling for TIV, age, gender and education, the negative relationship between LC and BrainPAD was tested. Namely, greater LC signal intensity related to lower BrainPAD scores reflecting better maintained brain – less brain deterioration. As already performed in Plini et al. 2021, the analyses were repeated for the other ROIs (DR, MR, VTA and NBM) and opposite relationships were investigated as well. In total, also this model was contrasted against nine alternative antithetic hypotheses.

All the VBM models statistical thresholds were set at P<0.01 uncorrected, and later increased progressively until the results disappeared (namely: P<0.001, P<0.01 Family Wise Error Correction – FWE).

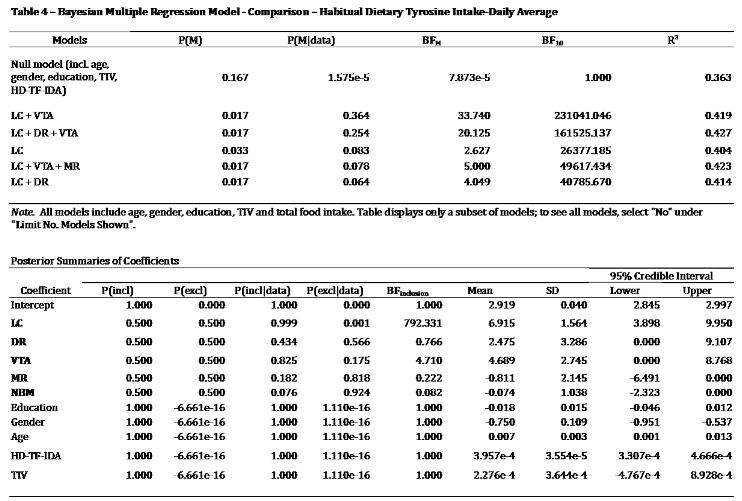

Statistical analyses in JASP and Bayesian modelling

Bayes Factors and Multiple Regression models

BF were generated in the JASP interface (Bayesian correlation model; (JASP -

https://jasp-stats.org/) on the basis of the average signal intensity of the significant clusters detected in the VBM analyses (when ROIs exceeded the statistical thresholds). The average signal intensity of the whole ROI was considered in the Bayesian correlation coefficients only for the ROIs which showed no significant cluster of voxels in the VBM analyses.

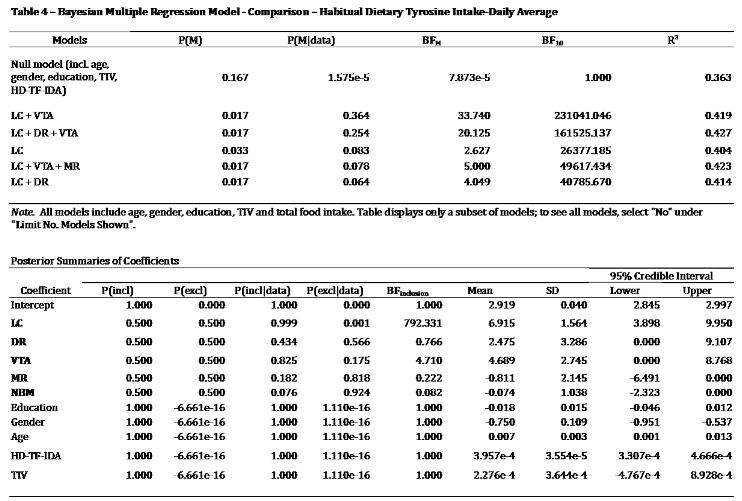

Bayesian multiple regression models were performed to examine the five neuromodulators’ seeds considered together within the same model as an additional control procedure. The relationship between the neuromodulatory subcortical system and HD-Tyr-IDA and BrainPAD were examined. One model considered HD-Tyr-IDA as dependent variable while entering the five ROIs as predictors while controlling for TIV, age, gender, education and HD-TF-IDA (in a second instance this model was further controlled for BMI, weight, height, and waist circumference to better assess the effect of body metrics on 330 individuals).

The other model considered BrainPAD as dependent variable while entering the five ROIs as predictors and controlling for TIV, age, gender and education. Similarly, in order to test which macro-nutrient better related to LC signal intensity, as part of the “control analyses on macronutrients”, in a Bayesian multiple regression model, LC signal intensity was entered as dependent variable and HD-TF-IDA, HD-Car-IDA, HD-Pro-IDA, HD-Wat-IDA as predictors. The model was controlled for age, gender, education, TIV and 4th ventricle, HD-TF-IDA, BMI, weight, height, and waist circumference. All the models were run with the default JASP settings with only exception of selection “compare to the null model” and “Bayesian inclusion criteria - BIC” in the advanced options.

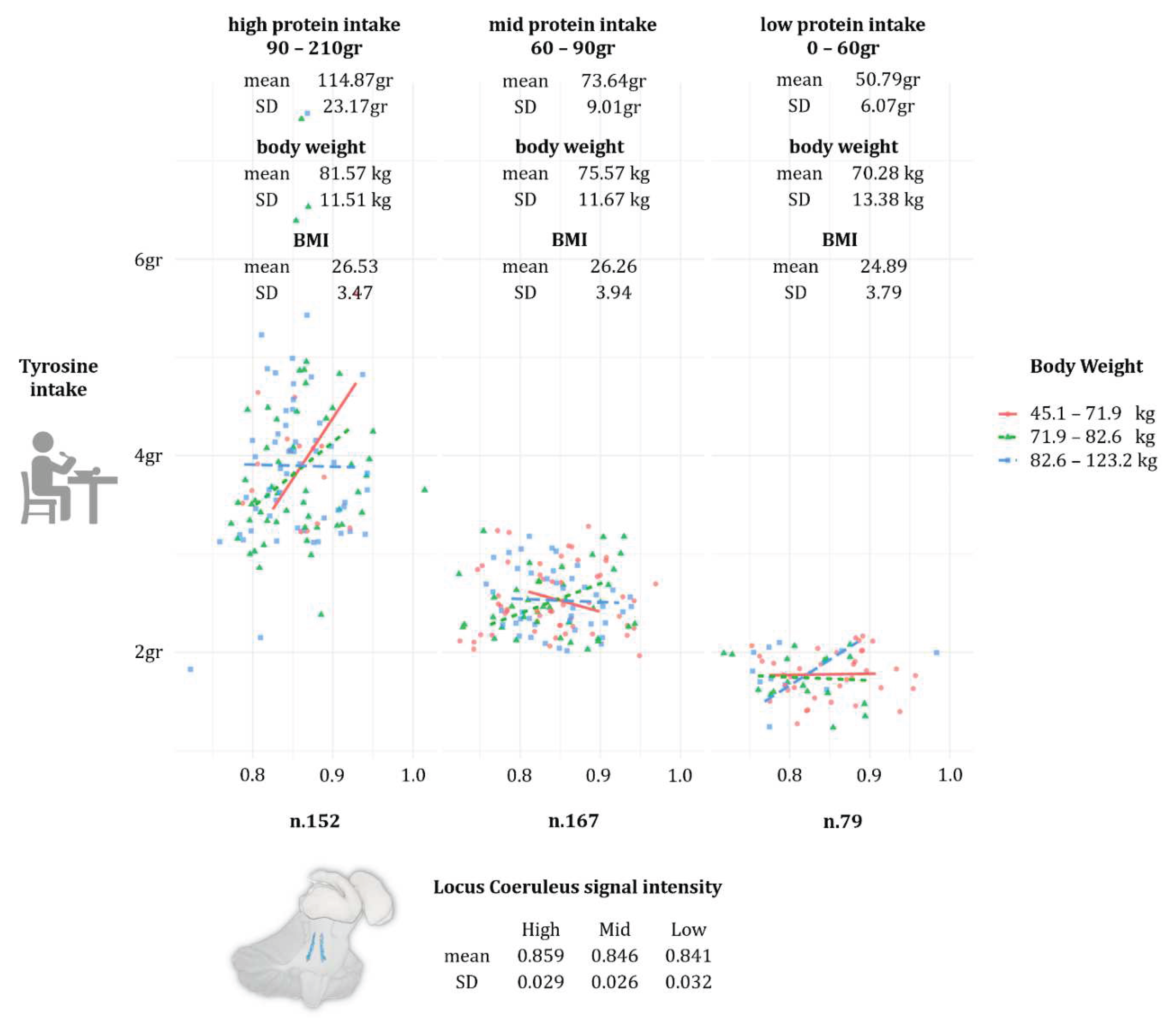

Protein intake visual modelling and ANCOVAs

Lastly, to better contextualise within the ESPEN guidelines the participants’ dietary behaviour in matter of protein intake, a visual model was built in JASP by treating HD-Pro-IDA (visual modelling -> flexpot) as a factor divided in three levels (low: 0 to 60gr daily; mid: 61 to 90gr daily; and high: 91 to 210gr daily). Protein intake was entered as planned variable, while HD-Tyr-IDA as dependent variable, and LC signal intensity and body weight entered as independent variables. This was made in order to explore the individual average protein intake in relationship to body weight and HD-Tyr-IDA and their effect on LC integrity. The model was further corroborated by ANCOVAs which investigated whether significant differences occurred between the three levels (low, mid and high protein intake) and the following variables: TIV, LC, HD-Tyr-IDA, BMI and body weight. The models investigating BMI and body weight were covaried for age, gender and education, while the models investigating LC, HD-Tyr-IDA and TIV were controlled also for HD-TF-IDA, BMI and body weight.

Descriptive data

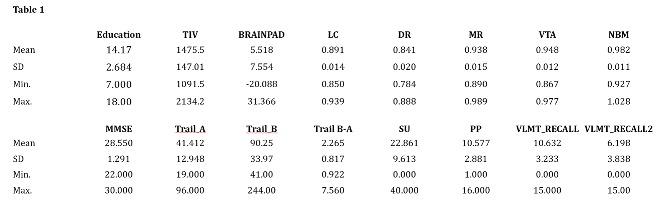

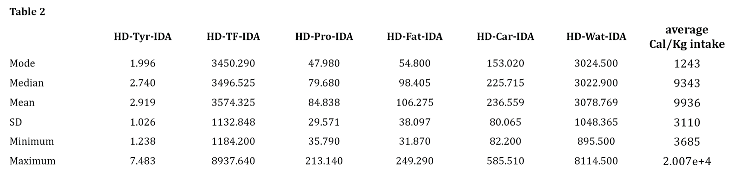

Key variables of the current sample are reported in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Table 1 reports education attainment and the average values of the key brain parameters examined in this study along with the selected neuropsychological tests.

Table 2 reports the daily average intake of tyrosine and macro-nutrients including also total food, water intake and average caloric intake.

Table 1.

Abbreviations: TIV–total intracranial volume; BrainPAD–brain predicted age difference; LC–Locus Coeruleus; DR–Dorsal Raphe; MR–Median Raphe; VTA–Ventral Tegmental Area; NBM- Nucleus Basalis of Meynert. Abbreviations for neuropsychological tests: MMSE–Mini Mental Examination State; Trail-A–Trail Making Test Part A; Trail-B–Trail Making Test part B; Trail B-ATrail Making Test part B minus part A; SU–Spatial Update (working memory); PP–Practical Problem solving (fluid intelligence); RAVLT recall 1 and 2 - Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

Table 1.

Abbreviations: TIV–total intracranial volume; BrainPAD–brain predicted age difference; LC–Locus Coeruleus; DR–Dorsal Raphe; MR–Median Raphe; VTA–Ventral Tegmental Area; NBM- Nucleus Basalis of Meynert. Abbreviations for neuropsychological tests: MMSE–Mini Mental Examination State; Trail-A–Trail Making Test Part A; Trail-B–Trail Making Test part B; Trail B-ATrail Making Test part B minus part A; SU–Spatial Update (working memory); PP–Practical Problem solving (fluid intelligence); RAVLT recall 1 and 2 - Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

Table 2.

Abbreviations: HD-Tyr-IDA–habitual dietary tyrosine intake on daily average; HD-TF-IDA - habitual total food intake on daily average; HD-Pro-IDA - habitual dietary protein intake on daily average HD-Fat-IDA - habitual dietary fat intake on daily average; HD-Car-IDA - habitual dietary carbohydrates intake on daily average; HD-Wat-IDA - habitual dietary water intake on daily average.

Table 2.

Abbreviations: HD-Tyr-IDA–habitual dietary tyrosine intake on daily average; HD-TF-IDA - habitual total food intake on daily average; HD-Pro-IDA - habitual dietary protein intake on daily average HD-Fat-IDA - habitual dietary fat intake on daily average; HD-Car-IDA - habitual dietary carbohydrates intake on daily average; HD-Wat-IDA - habitual dietary water intake on daily average.

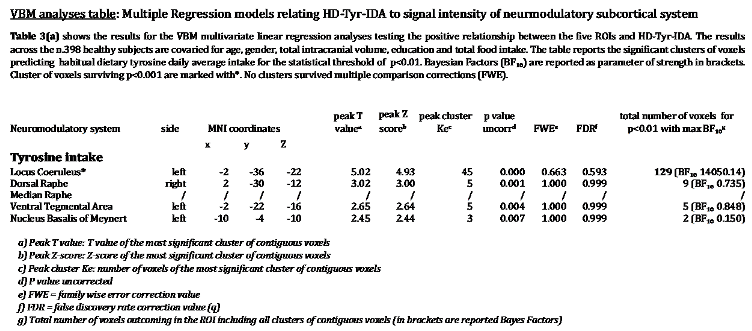

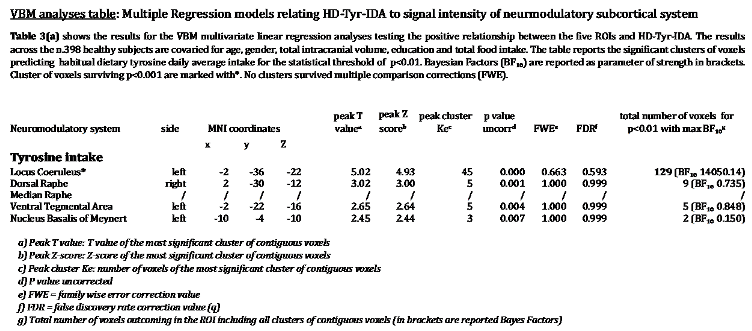

Voxel-Based Morphometry Analyses (VBM)

VBM – Tyrosine and Bayesian modelling

In accordance with our hypothesis, VBM analyses revealed a positive relationship between LC signal intensity and greater tyrosine intake in grams while controlling for age, gender, education, TIV and total food intake. As reported in Table 3, for P<0.01, 129 voxels within the bilateral LC regions were associated with greater dietary tyrosine intake (maximal BF

10 14050.14). As shown in

Figure 2, we note that a significant portion of these LC findings overlap with the core of previously published LC atlases and masks (Keren et al. 2009 & 2015; Tona et al. 2017; Betts et al. 2017; Dahl et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2019; Rong Ye et al. 2020; Dahl et al. 2021; García-Gomar et al. 2022).

By testing the other neuromodulator seeds, negligible or no results arose. In the same way, no results emerged when the opposite relationships for the five ROIs were tested.

When examining the five ROIs simultaneously in the same Bayesian multiple regression model, the combined effect of LC + VTA (BF10 231041.046) resulted in the strongest model related to tyrosine intake, and the relationship between tyrosine and VTA emerged (BFinclusion 4.710), but the disproportionate involvement of LC-NA system was predominant (BFinclusion 792.331 - for details refer to Table 4). Furthermore, when in the model was additionally controlled for participants’ BMI, body weight, height, waist circumference and the 4th ventricle, the same pattern of findings was obtained. Noticeably, the LC+VTA effect increased to BF10 to 349682.325 and the LC BFinclusion doubled to 1412.285 while the VTA raised to 40.732. For further details refer to Table 4b in the Supplementary Materials.

Lastly, the young and older group did not significantly differ in HD-Tyr-IDA, neither in LC signal intensity. At visual inspection and with formal analyses, the the LC-tyrosine relationship showed the same trajectory and the same pattern in both young and old populations (for further details please refer to Table 4c,d and Figure 2b in the Supplementary Materials). This result is consistent with the findings by Kühn and colleagues (2019), where no differences in the relationship between Tyrosine and cognitive functions were found in young and older participants.

VBM – control analyses on macro-nutrients and Bayesian modelling

No relevant associations emerged for HD-Car-IDA and HD-Wat-IDA (Table 7 Supplementary Materials). In contrast, significant associations between LC signal intensity and HD-Pro-IDA and HD-Fat-IDA emerged. Specifically for P<0.01 141 LC voxels distributed bilaterally related to protein intake and 51 LC voxels related to fat intake. The associations between LC and protein and fat were weaker than the associations between LC and tyrosine, suggesting that LC-tyrosine findings appear to be more specific in relationship to LC in comparison with the main macro-nutrients. LC-Tyrosine (BF10 14050.14), LC-HD-Pro-IDA (BF10 6926.05), LC-HD-Fat-IDA (BF10 483.20). When testing for opposite relationships, no or negligible associations emerged for all four macro-nutrients.

Furthermore, when the macro-nutrients were tested simultaneously in the same Bayesian multiple regression model (controlling for age, gender, education, TIV, 4th ventricle, HD-TF-IDA, BMI, weight, height, and waist circumference), HD-Tyr-IDA (BF10 4033.661; R² 0.402) was the strongest variable related to LC followed by HD-Pro-IDA (BF10 3864.57; R² 0.401). Weaker associations were found for the other variables (for further detail see Table 7b,c in the Supplementary Materials). This outlines the tight interdependence between protein intake and tyrosine which in this sample are highly related (Pearson’s r 0.979*** - BF10 2.809e+268).

Protein intake: visual modelling and ANCOVAs

ANCOVAs on the three groups of protein intake (low, mid and high) revealed that TIV, BMI and body weight did not significantly differ across different level of dietary protein intake (HD-Pro-IDA), tables are not reported for the sake of brevity. On the other hand, HD-Tyr-IDA and LC MRI signal intensity significantly differs across the three groups while controlling for age, gender, education, TIV, HD-TF-IDA, BMI and body weight. Namely, individuals reporting eating in average more protein on daily basis (1.4gr~ of protein per kg of body weight – kg/bw), shown significantly higher tyrosine intake (HD-Tyr-IDA) and greater LC integrity when compared to individuals eating mid (1gr~ kg/bw) and low (0.7gr~ kg/bw) levels. For greater details please refer to

Figure 3 (protein intake visual modelling) and to Tables 8–12 in the Supplementary Materials.

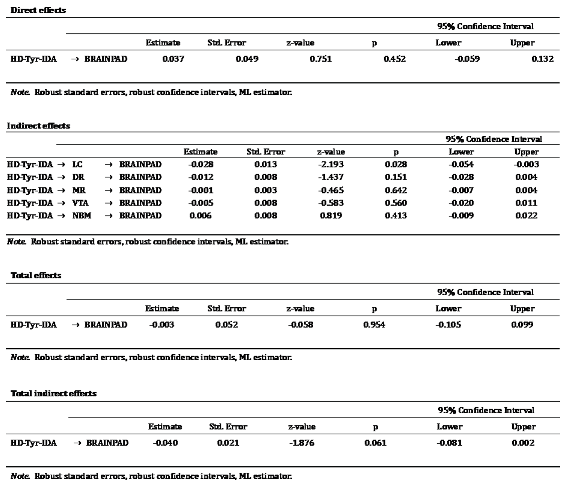

VBM – BrainPAD and Bayesian modelling

The relationship between brain maintenance and the five neuromodulators’ seeds revealed a disproportionate relationship between LC integrity and lower BrainPAD scores in comparison with the other nuclei. The significant portion of these LC findings overlap with the core of previously published LC atlases and masks (Keren et al. 2009 & 2015; Tona et al. 2017; Betts et al. 2017; Dahl et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2019; Rong Ye et al. 2020; Dahl et al. 2021; García-Gomar et al. 2022). Better brain maintenance was related to an LC cluster of 201 voxels distributed bilaterally (P<0.01 - BF10 5.44 - in Table 15 in the Supplementary Materials). Figure 9 (in the Supplementary Materials) shows the spatial extent of the LC results in comparison with the previously published LC atlases and masks. The second strongest relationship was observed within the DR region showing a cluster of 49 voxels (BF10 0.12). However, when the opposite relationships were tested, while for the other neuromodulatory seeds no significant clusters emerged, an NBM cluster of 30 voxels mostly right lateralised related in the opposite direction, namely accelerated GM aging, greater BrainPAD scores. However, this cluster did not survive more stringent statistical thresholds. When the five ROIs were considered together within the same Bayesian multiple regression model (Table 16), the primary involvement of the LC-NA system in brain maintenance was confirmed (BF10 28.56). As observed in Plini et al. 2021, this was followed by the DR (BF10 11.45). In addition, the combined effect of LC + DR was the third model related to BrainPAD (BF10 22.46). The other ROIs showed weaker associations, for further details refer to Table 11 in the Supplementary Materials.

Discussion

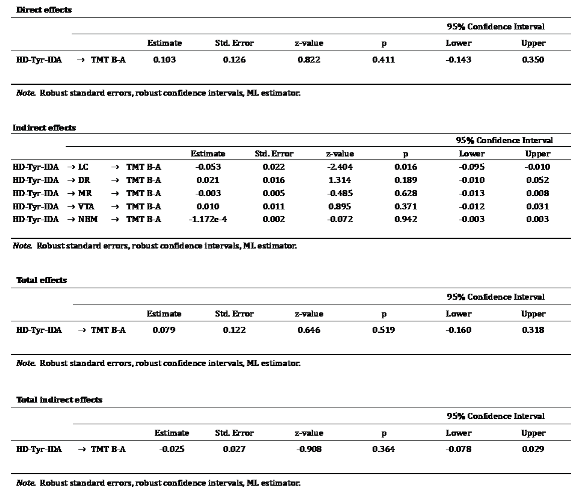

The present study provides evidence that dietary tyrosine intake relates to LC integrity in a sample of 398 healthy adults (age range 25-83). Negligible associations were found for the other ROIs indicating a predominant sensitivity of the LC to tyrosine intake in contrast to the other main neuromodulatory nuclei. In addition, LC integrity was disproportionately related to brain maintenance (BrainPAD) and, by comparison with the other subcortical nuclei, only the LC significantly mediated the relationship between tyrosine intake and BrainPAD, and tyrosine intake and one measure of high order cognitive functions (TMT B-A). This novel evidence indicates how associations between diet and brain health may be underpinned by the LC-NA system and provides further neurobiological insight into the relationship between diet, cognition and overall brain health across the life-span. Moreover, tyrosine intake measured at T1 relates with LC integrity three years later (T2 n. 291). Lastly, protein and fat intake related to LC-NA system integrity although the relationship between tyrosine and LC-NA was statistically stronger, which lead to the inference that LC integrity might be more specifically affected by tyrosine as opposed to protein and fat intake. Together these findings present the first evidence linking habitual dietary tyrosine intake to MRI integrity of the LC-NA system, and suggest that diet (protein and related tyrosine intake) might significantly affect brain maintenance and cognitive functioning through LC-NA system integrity in healthy individuals.

Tyrosine intake, Locus Coeruleus and Trail Making Test (attentive cognitive control)

Evidence indicating a beneficial role of tyrosine on cognitive functions might be explained by the relationship observed in this sample. Our results demonstrated that greater tyrosine intake, by supporting LC structural integrity, would ensure adequate/greater NA metabolism when needed, while laying the ground for better cognitive performance. This view is consistent with pharmacological studies reporting enhanced cognitive performances when noradrenergic drugs are administered (Minzenberg et al. 2008; Alnæs et al. 2014; Dockree et al. 2017; Gelbard-Sagiv et al. 2018; Pinggal et al. 2022; Hoang et al. 2022). Specifically, cognition is enhanced in attentional tasks, visuo-spatial functions and cognitive control, aspects which are underpinned by the LC-NA system, (Ghosh and Maunsell 2022; Munn et al. 2021; Aston-Jones and Waterhouse 2016; Aston-Jones et al. 1999; Sarah 2009; Mather and Harley 2016; Holland et al. 2021; Robertson 2013&2014) evaluated by TMT (Tombaugh 2004; Lezak et al. 2004; Bowie and Harvey 2006) and more precisely by TMTB-A (Arbuthnott and Frank 2000; Gaudino et al. 1995; Corrigan and Hinkeldey 1987). Indeed, associations between TMT and LC-NA system were already recorded in literature by Clewett and colleagues (2016), Dutt and colleagues (2021) and in our previous work (Plini et al. 2021). Accordingly, the mediation of the relationship between tyrosine and TMT-B-A by LC, is in line both with earlier empirical observations and our working hypothesis, offering plausible insight into the LC-NA system in relation to diet and higher order cognitive functioning.

Tyrosine intake, Locus Coeruleus and BrainPAD (brain maintenance)

These results provide some explanation for the widely documented role of diet in neurodegenerative disease prevention, and for the previously reported associations between tyrosine intake and greater cognitive/attentional control, which, might be mechanistically mediated by the LC-NA system over the other main neuromodulatory systems. Consistent with Robertson’s model, LC integrity was associated with brain maintenance (see also Plini et al. 2021). The relationship between tyrosine intake and BrainPAD was mediated exclusively by LC-NA system integrity. We interpret this interdependence as a way to account for how diet may affect brain health via the LC-NA system. Greater dietary tyrosine intake could preserve brain health by supporting the LC-NA system consistent with literature reporting greater protein and amino-acid intake relating to brain health and preserved cognition (Gao et al. 2022; Glenn et al. 2019; Kinoshita et al. 2021; Fan et al. 2021; Coelho-Júnior et al. 2021; Pacholko et al. 2019). Dietary tyrosine intake would ensure adequate NA biosynthesis which would affect brain and cognitive health arising from the neurotrophic and protective actions of NA in the brain (Heneka et al. 2002; Heneka et al. 2015; Troadec et al. 2005; Feinstain et al. 2002; Counts et al. 2010; Hassani et al. 2020; Traver et al. 2005; Mannari et al. 2008; Omulabi et al. 2021). As postulated by Robertson (Robertson 2013&2014), greater concentrations of NA in the brain would prevent neurodegenerative processes via anti-inflammatory and neurotrophic properties of NA in the brain. In light of these properties, dietary tyrosine intake might be also read as a potential factor supporting neuronal resilience and cognitive functioning by supporting the LC-NA system.

BrainPAD and the neuromodulatory subcortical system

We found that the LC-NA system disproportionally relates to lower BrainPAD (reduced brain aging) in comparison to the other neuromodulator ROIs. These results replicate the previous findings reported in Plini et al. 2021, where BrainPAD scores were primarily associated with LC integrity followed by DR integrity while showing no association with the MR. This may suggest a relevant serotoninergic role in brain maintenance, and this replicated our previous pattern of findings (Plini et al. 2021). However, this DR involvement might be interpreted also as a noradrenergic involvement in brain maintenance. Indeed, noradrenergic compensation has been observed within the DR (Szot et al. 2000; Szot et al. 2006; Szot et al. 2007; Matchett et al. 2021) and DR itself is also a key multipurpose nucleus comprising catecholaminergic neurons (30% of the whole DR – Farley et al. 1977; Baker et al. 1991; Ordway et al. 1997; Kirby et al. 2003). This opens to the interpretation of the DR results attributable to the DR noradrenergic component rather than only to its serotonergic aspect. This interpretation is further supported by the lack of association found between BrainPAD and the MR. As a matter of fact, when the five ROIs were considered together within the same Bayesian multiple regression model, this interpretation was corroborated. Indeed, this analysis confirmed the primary role of the LC-NA system (BF10 28.56) followed by the DR (BF10 11.45) while showing no relevant association for the serotonergic MR.

Control analyses on macro-nutrients

The results of the control analyses underline the difficulty in differentiating between micro and macro nutrient intake in this sample while suggesting they reflect actual meat intake. Indeed, as pointed out by Kühn and colleagues (Kühn et al. 2019), tyrosine intake was highly related to meat intake (r 0.85 P<0.001). Therefore, the associations observed between the LC-NA system and HD-Pro-IDA and HD-Fat-IDA might even be read within the reported beneficial role of meat intake both for the health aspects of fatty-acid and amino acid content (including amino-acid tyrosine) (Gupta 2016; Black et al. 2019 A; Black et al. 2019 B; Scarmeas et al. 2018; Salter 2018; Balehegn et al. 2019; Lennerz et al. 2021). However, we believe that these analyses do not diminish the relevance of tyrosine findings since the LC-tyrosine relationship remains the strongest accordingly to Bayes Factors, namely LC-tyrosine (BF10 14050.14), LC-HD-Pro-IDA (BF10 6926.05), LC-HD-Fat-IDA (BF10 483.20). According to Bayesian modelling, tyrosine findings appear to be more specific in relationship to LC in comparison with the main macro-nutrients.

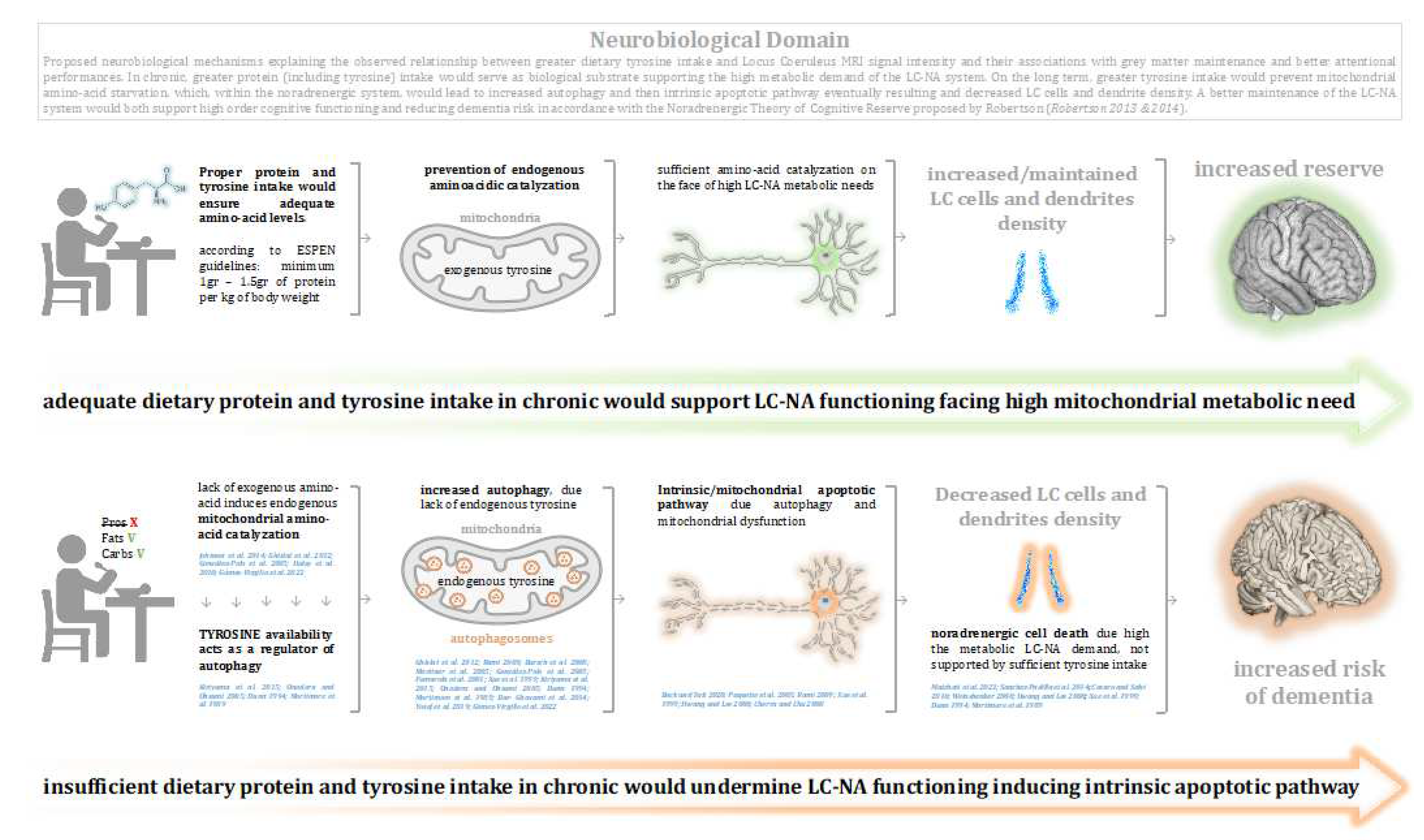

Neuro-chemical mechanistic frameowr of LC-Tyrosine relationship

The bio-chemical mechanism behind the LC-tyrosine relationship potentially resides in the neurochemistry of neuromodulator biosynthesis and apoptosis. Since it is documented that: 1) amino-acid depletion induces autophagy and then apoptosis (Gómez-Virgilio et al. 2022; Ghislat et al. 2012; Kiriyama et al. 2015; Hwang and Lee 2008; González-Polo et al. 2005; Martinet et al. 2005; Eisler et al. 2004; Bursch et al. 2008; Fumarola et al. 2001), that 2) the lack of exogenous amino-acids induces endogenous (mitochondrial) amino-acid catalysation (Johnson et al. 2014; Haley et al. 2010; Onodera and Ohsumi 2005; Ghislat et al. 2012; Gómez-Virgilio et al. 2022), and that 3) tyrosine availability acts as a regulator of autophagy (Mortimore et al. 1989; Dunn 1994; Kiriyama et al. 2015), within the same continuum, the lack of tyrosine supply, or insufficient tyrosine levels, might negatively affect LC functionality, increasing its cellular vulnerability to neurodegeneration (Wong et el. 2020; Matchett et al. 2021; Xue et al. 1999; Dunn 1994; Gómez-Virgilio et al. 2022). Even though autophagy can have a protective role (Heymann et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2019; Rami 2009; Ghavami et al. 2014; Menzies et al. 2017; Bar-Yosef et al. 2019), autophagy induced by amino-acid deficiency (the most influential factor - Kiriyama et al. 2015; Onodera and Ohsumi 2005; Dunn 1994; Mortimore et al. 1989) can lead to cell death, particularly in large projecting neurons such as sympathetic neurons (Xue et al. 1999; Nixon et al. 2005; Cherra and Chu 2008; Ghavami et al. 2014; Bar-Yosef et al. 2019; Ghislat et al. 2012; Kiriyama et al. 2015; Hwang and Lee 2008; González-Polo et al. 2005; Martinet et al. 2005; Eisler et al. 2004; Bursch et al. 2008; Fumarola et al. 2001). It is further documented that LC neurons are more susceptible than other nuclei to oxidative stress, heavy metal accumulation and chronic inflammation (Matchett et al. 2021; Pamphlett et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2020). This drives LC vulnerability towards accelerated neurodegeneration in comparison with other nuclei (Chen et al. 2022; Matchett et al. 2021; Ehrenberg et al. 2017; Brettschneider et al. 2015; Braak et al. 2011). Thus, insufficient tyrosine levels may negatively impact on the metabolic burden made on the LC ultimately affecting its integrity and functionality (Wong et el. 2020; Matchett et al. 2021; Xue et al. 1999; Dunn 1994; Gómez-Virgilio et al. 2022). The lack of amino-acids may also paradoxically contribute to a metabolic shift via the breakdown of endogenous peptides and amino-acids within mitochondria (Johnson et al. 2014; Haley et al. 2010; Onodera and Ohsumi 2005; Dunn 1994; Mortimore et al. 1989; Gozuacik and Kimchi 2007) burdening the metabolic capacity of LC cells inducing an apoptotic state – intrinsic/mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (Paquette et al. 2005; Hwang and Lee 2008; Li et al. 2022; Bock and Tait 2020; Bursch et al. 2008; Xue et al. 1999; González-Polo et al. 2005; Martinet et al. 2005; Eisler et al. 2004; Wong et al. 2020; Nixon et al. 2005 Wong et al. 2020; Nixon et al. 2005; Ghavami et al. 2014). On the other hand, sufficient tyrosine availability supports LC functions. Noticeably, as pointed out by Matchett and colleagues (Matchett et al. 2021), because the high and unique bioenergetic needs of the LC, tyrosine levels might play a relevant role in compensating for mitochondrial associated oxidative stress (and related LC vulnerability) (Matchett et al. 2021; Sanchez-Padilla et al. 2014; Weinshenker 2008; Hwang and Lee 2008; Xue et al. 1999; Dunn 1994; Mortimore et al. 1989). Given LC vulnerability, and the neuroprotective role of NA in the brain (Hassani et al. 2020; Robertson 2013&2014), what is described by Matchett and colleagues (2021) also provides an explanation for the negligible findings observed between HD-Tyr-IDA and VTA and other neuromodulatory nuclei compared to the LC. The greater LC vulnerability, and also the neuroprotective role of NA in the brain (Hassani et al. 2020; Robertson 2013&2014), might be responsible for the emergence of the Tyrosine-LC relationship in comparison with the other neuromodulatory nuclei, which are biologically more resilient and characterised by greater number of neurons (Matchett et al. 2021; Pamphlett et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2020; Sanchez-Padilla et al. 2014; May and Paxinos 2012; Weinshenker 2008). Concerning the VTA, another aspect might explain the weaker associations between tyrosine and the dopaminergic system. An interesting study from Smith and colleagues (Smith et al. 1978) posited the idea that the majority of dopaminergic turnover actually occurs in situ within the pre-synaptic terminals (i.e. away from the Substantia Nigra and VTA and within regions like the Striatum and the cortex), which was in comparison to NA and 5-HT, where the major turnover was shown in pons-medullar regions near of the LC and the DR. This interpretation might appear simplistic, but may it may serve to partly explain the nature of this weaker relationship. Therefore, the level of tyrosine might not appear to directly affect VTA integrity because DA synthesis would be more diffuse and scattered across the brain. Accordingly, this would undermine the way how this association stands out by using our methodology.

In conclusion, as discussed above and consistent with our findings, the role of tyrosine might be read as supporting the biosynthesis of NA in the LC. Accordingly, greater levels of tyrosine, by supporting the high bioenergetic demand of the LC-NA system, would prevent LC degeneration while providing for brain maintenance arising from the neurotrophic and neuroprotective actions of NA throughout the neuroaxis. Indeed, as postulated by Robertson, greater NA synthesis (arising from tyrosine availability) would preserve brain functioning via a plethora of brain mechanisms which includes enhanced expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factors (BDNF) and anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative mediators particularly towards the dopaminergic and cholinergic neurons (Heneka et al. 2002; Heneka et al. 2015; Troadec et al. 2005; Feinstain et al. 2002; Counts et al. 2010; Hassani et al. 2020; Traver et al. 2005; Mannari et al. 2008; Omulabi et al. 2021; for review see: Giorgi et al. 2020, Matchett et al. 2021 and Mather 2021).

Figure 4.

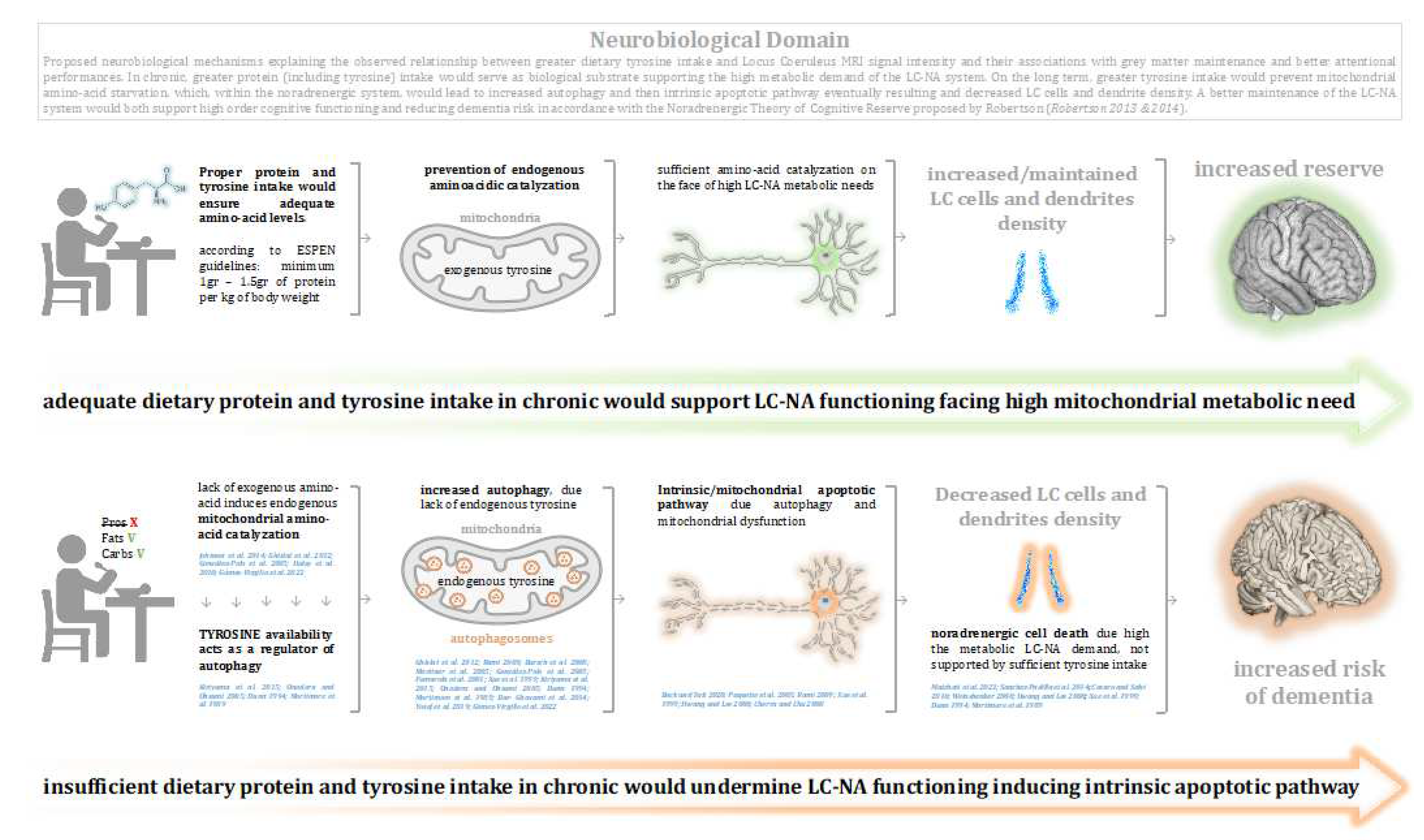

Graphical discussion: Proposed neurobiological mechanisms explaining the observed relationship between greater dietary tyrosine intake and Locus Coeruleus MRI signal intensity and their associations with grey matter maintenance and better attentional performances. In chronic, greater protein (including tyrosine) intake would serve as biological substrate supporting the high metabolic demand of the LC-NA system. On the long term, greater tyrosine intake would prevent mitochondrial amino-acid starvation, which, within the noradrenergic system, would lead to increased autophagy and then intrinsic apoptotic pathway eventually resulting and decreased LC cells and dendrite density. A better maintenance of the LC-NA system would both support high order cognitive functioning and reducing dementia risk in accordance with the Noradrenergic Theory of Cognitive Reserve proposed by Robertson (Robertson 2013 & 2014). While the nature of the observed relationship between LC and Tyrosine intake is correlational, it should be considered that the other experiments reported causational effects between amino-acid depletion and related mitochondrial (autophagic) dysfunction, which ultimately lead to intrinsic apoptosis, studied also within the noradrenergic neurons (Xue et al. 1999). However, it should be taken into account that the proposed underlining mechanisms may be explained by other variables and potentially reside also within other neurobiological dynamics.

Figure 4.

Graphical discussion: Proposed neurobiological mechanisms explaining the observed relationship between greater dietary tyrosine intake and Locus Coeruleus MRI signal intensity and their associations with grey matter maintenance and better attentional performances. In chronic, greater protein (including tyrosine) intake would serve as biological substrate supporting the high metabolic demand of the LC-NA system. On the long term, greater tyrosine intake would prevent mitochondrial amino-acid starvation, which, within the noradrenergic system, would lead to increased autophagy and then intrinsic apoptotic pathway eventually resulting and decreased LC cells and dendrite density. A better maintenance of the LC-NA system would both support high order cognitive functioning and reducing dementia risk in accordance with the Noradrenergic Theory of Cognitive Reserve proposed by Robertson (Robertson 2013 & 2014). While the nature of the observed relationship between LC and Tyrosine intake is correlational, it should be considered that the other experiments reported causational effects between amino-acid depletion and related mitochondrial (autophagic) dysfunction, which ultimately lead to intrinsic apoptosis, studied also within the noradrenergic neurons (Xue et al. 1999). However, it should be taken into account that the proposed underlining mechanisms may be explained by other variables and potentially reside also within other neurobiological dynamics.

Limitations

There are several limitations to note. To begin with, and, as pointed out by Kühn and colleagues (2019), the main limitation encountered analysing these data concerns tyrosine assessment. Given the self-report nature of the EPIC questionnaire, HD-Tyr-IDA cannot be precisely evaluated, and the observed effect might be attributable to other macro- and micro-nutrients and potentially even to other unknown variables. It should be considered that given the high correlation between meat intake and tyrosine, the observed effects might depend also on overall protein and fat intake, which in this sample predominantly mirrors meat consumption. In light of that, it should be taken into account that the positive effects observed in terms of brain and cognitive health could be due not only to tyrosine, but also to the other amino-acids present in meat and other beneficial nutrients, for example omega-three fatty acids, iron, zinc, vitamin D and group B (Mulvihill 2014; McNeill 2014; Gupta 2016; Black et al. 2019 A; Black et al. 2019 B; Scarmeas et al. 2018; Salter 2018; Derbyshire et al. 2017; Nohr and Biesalski 2007; Balehegn et al. 2019; Lennerz et al. 2021; Roussell et al. 2011; Ben-Dor et al. 2021). However, testing multiple hypothesis while thoroughly controlling for several confounders, we observed that the LC-Tyrosine relationship was statistically stronger than LC-Protein and LC-Fat relationships, leading to the inference that interdependence between tyrosine and the LC-NA system was more specific, and therefore, providing greater reliability.

Another constraint involves the methodological limitations of MRI analyses in retrospective and longitudinal studies. Ex-vivo histological investigations would offer more precise quantifications about dietary behaviour and related brain integrity, particularly if assessed precisely together with other physical and behavioural variables. Nevertheless, within these limitations, whilst being consistent with our a-priori pre-registered hypothesis, our findings are consistent with earlier studies on tyrosine and protein intake (Suzuki et al. 2020; Kita et al. 2018; Hase et al. 2015; Jongkeese et al. 2015; Attipoe et al. 2015; van der Zwaluw et al. 2014; van de Rest et al. 2014; Colzato et al. 2014; Colzato et al. 2013; Aquilani et al. 2008; McMorris et al. 2007; Gao et al. 2022; Li et al. 2020; Glenn et al. 2019; Kinoshita et al. 2021; Fan et al. 2021; Coelho-Júnior et al. 2021; Pacholko et al. 2019; Livingston et al. 2020; Fan et al. 2021), and also with previous in-vivo evidence using similar methodology (Plini et al. 2021; Dutt et al. 2021; Ylilauri et al. 2019; Poly et al. 2011). Furthermore, we have also enhanced the solidity of our design by performing thorough control analyses. Indeed, the LC-tyrosine hypothesis was contrasted against 37 different hypotheses, while systematically covarying for relevant confounding factors such as age, gender, education, total food intake, total intracranial volume, the 4th ventricle and body metrics (BMI, body weight, height and waist circumference). In addition to this, the reported associations were also confirmed when different methodologies were implemented and even replicated “anecdotally” in a 3-year follow-up. Further corroboration by Bayesian modelling, further strengthens the reliability of observations, especially in light of the high Bayesian Factors obtained.

Conclusions, clinical implications and future directions

These results provide the first evidence linking dietary tyrosine intake with

in-vivo LC-NA system integrity and its intercorrelation both with brain maintenance and neuropsychological performances in healthy adults. These results strengthen the role of dietary style in supporting brain health and reducing risk of neurodegeneration and imply that diet has an effect on LC-NA system integrity. The evidence provides support for the most recent European nutritional guidelines (ESPEN -

https://www.espen.org/guidelines-home/espen-guidelines) which considers adequate protein intake in general population to set the minimal protein intake to 1–1.5 gr per kg of body weight specifically in older adults (Kieswetter et al. 2020;

Volkert et al. 2019; Baum et al. 2016; Kozjek 2016; Volkert et al. 2015;

Deutz et al. 2014). The evidence may also open new approaches to prevention and treatment or ameliorating brain and cognitive function in healthy and clinical populations (Aliev et al. 2014; Andres-Benito et al. 2017; Plini et al. 2021; Livingston et al. 2020).

Chronic tyrosine supplementation might be clinically feasible and useful to maintain brain health, particularly when the minimal dietary requirements are not met. However, the right amount of tyrosine as supplement has to be evaluated within the whole dietary life-style at individual level. Additionally, excessive acute dosages without a preliminary progressive administration may not being beneficial for certain individuals (Van de Rest et al. 2017). Indeed, while some studies to date did not report a significant positive effect of tyrosine administration (Froböse et al. 2020; Van de Rest et al. 2017; Bloemendaal et al. 2018), other interventions based on protein supplementation and amino acid intake (including tyrosine alone) reported beneficial effects on cognitive health (Suzuki et al. 2020; Kita et el. 2018; Hase et al. 2015; Jongkeese et al. 2015; Attipoe et al. 2015; van der Zwaluw et al. 2014; van de Rest et al. 2014; Colzato et al. 2014; Colzato et al. 2013; Aquilani et al. 2008; McMorris et al. 2007). Accordingly, adjusting dietary behaviour might efficiently extend cognitive longevity while protecting against neurodegenerative diseases (Gao et al. 2022; Li et al. 2020; Glenn et al. 2019; Kinoshita et al. 2021; Fan et al. 2021; Coelho-Júnior et al. 2021; Pacholko et al. 2019; Livingston et al. 2020; Fan et al. 2021). Future studies should aim to replicate and extend these findings performing observational and experimental longitudinal analyses where a wider variety of dietary macro- and micro-nutrients are monitored along with blood markers, life-style indices, physical parameters, multimodal MRI and neuropsychological testing. Future studies should also aim to clarify the potential role of diet on LC-NA system and the neuromodulaory subcortical system in order to better understand the neurobiology of neurodegenerative diseases.

Authors Contributions

ERGP: Conceptualization, study design, statistical analyses, results interpretation and visualization, manuscript writing. MCM: manuscript editing and statistical analyses support, AH: interpretation support and manuscript editing; MM: interpretation support and manuscript editing; RA: statistical analyses support. RB: BrainPAD methodology. RW: BrainPAD supervision; IHR: conceptualization, supervision and manuscript editing. PMD: supervision; SK: provided the data and calculated nutritional factors SD: provided MRI and neuropsychological data, manuscript editing; MJD: assisted with statistical design, calculated data for time point 2, manuscript editing; KN: provided the data, manuscript edits, JD: provided the data, manuscript edits; GGW: provided the data; UL: provided the data. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Thanks are extended to Francesca Fabbricatore for the thoughtful comments and for proofreading the manuscript.

Fundings

Project founded by the Irish Research Council—Irish Research Council Laureate Consolidator Award (2018-23) IRCLA/2017/306 to Paul Dockree. This work reports data from the Berlin Aging Study II project, which was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung [BMBF]) under grant numbers #01UW0808, #16SV5536K, #16SV5537, #16SV5538, #16SV5837, #01GL1716A, and #01GL1716B. Another source of funding is the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin, Germany. Additional contributions (e.g., equipment, logistics, and personnel) are made from each of the other participating sites.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- (2022), 2022 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement., 18: 700-789. [CrossRef]

- Agharanya JC, Alonso R, Wurtman RJ. Changes in catecholamine excretion after short-term tyrosine ingestion in normally fed human subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981 Jan;34(1):82-7. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N., Ali, A., Riaz, S., Ahmad, A., & Aqib, M. (2021). Vegetable Proteins: Nutritional Value, Sustainability, and Future Perspectives. In E. Yildirim, & M. Ekinci (Eds.), Vegetable Crops - Health Benefits and Cultivation. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Akbaraly TN, Singh-Manoux A, Dugravot A, Brunner EJ, Kivimäki M, Sabia S. Association of Midlife Diet With Subsequent Risk for Dementia. JAMA. 2019 Mar 12;321(10):957-968. [CrossRef]

- Aletrino M., Vogels O., Van Domburg P., Donkelaar H.T. Cell loss in the nucleus raphes dorsalis in alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 1992;13:461–468. [CrossRef]

- Aliev G., Shahida K., Gan S.H., Firoz C., Khan A., Abuzenadah A., Kamal W., Kamal M., Tan Y., Qu X., et al. Alzheimer Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: The Link to Tyrosine Hydroxylase and Probable Nutritional Strategies. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2014;13:467–477. [CrossRef]

- Alnæs D, Sneve MH, Espeseth T, Endestad T, van de Pavert SH, Laeng B. Pupil size signals mental effort deployed during multiple object tracking and predicts brain activity in the dorsal attention network and the locus coeruleus. J Vis. 2014 Apr 1;14(4):1. [CrossRef]

- Anderson GH, Johnston JL. Nutrient control of brain neurotransmitter synthesis and function. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1983 Mar;61(3):271-81. [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Benito P., Fernández-Dueñas V., Carmona M., Escobar L.A., Torrejón-Escribano B., Aso E., Ciruela F., Ferrer I. Locus coeruleus at asymptomatic early and middle Braak stages of neurofibrillary tangle pathology. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2017;43:373–392. [CrossRef]

- Aquilani R, Scocchi M, Boschi F, Viglio S, Iadarola P, Pastoris O, Verri M. Effect of calorie-protein supplementation on the cognitive recovery of patients with subacute stroke. Nutr Neurosci. 2008 Oct;11(5):235-40. [CrossRef]

- Arbuthnott K, Frank J. Trail making test, part B as a measure of executive control: validation using a set-switching paradigm. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2000 Aug;22(4):518-28. [CrossRef]

- Aston-Jones G., Rajkowski J., Cohen J. Role of locus coeruleus in attention and behavioral flexibility. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;46:1309–1320. [CrossRef]

- Aston-Jones G., Waterhouse B. Locus coeruleus: From global projection system to adaptive regulation of behavior. Brain Res. 2016;1645:75–78. [CrossRef]

- attention.Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26(1), 38–52.

- Attipoe S, Zeno SA, Lee C, Crawford C, Khorsan R, Walter AR, Deuster PA. Tyrosine for Mitigating Stress and Enhancing Performance in Healthy Adult Humans, a Rapid Evidence Assessment of the Literature. Mil Med. 2015 Jul;180(7):754-65. [CrossRef]

- B. Mulvihill, HUMAN NUTRITION | Micronutrients in Meat, Editor(s): Michael Dikeman, Carrick Devine, Encyclopedia of Meat Sciences (Second Edition), Academic Press, 2014,Pages 124-129,ISBN 9780123847348. [CrossRef]

- Bachman S.L., Dahl M.J., Werkle-Bergner M., Düzel S., Forlim C.G., Lindenberger U., Kühn S., Mather M. Locus coeruleus MRI contrast is associated with cortical thickness in older adults. Neurobiol. Aging. 2021;100:72–82. [CrossRef]

- Baker K.G., Halliday G.M., Hornung J.P., Geffen L.B., Cotton R.G. Distribution, morphology and number of monoamine-synthesizing and substance P-containing neurons in the human dorsal raphe nucleus. Neuroscience. 1991;42:757–775. [CrossRef]

- Balehegn M, Mekuriaw Z, Miller L, Mckune S, Adesogan AT. Animal-sourced foods for improved cognitive development. Anim Front. 2019 Sep 28;9(4):50-57. [CrossRef]

- Bar-Yosef T, Damri O, Agam G. Dual Role of Autophagy in Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019 May 28;13:196. [CrossRef]

- Barnard N.D., Bush A., Ceccarelli A., Cooper J., de Jager C.A., Erickson K.I., Fraser G., Kesler S., Levin S.M., Lucey B., et al. Dietary and lifestyle guidelines for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2014;35:S74–S78. [CrossRef]

- Barulli D., Stern Y. Efficiency, capacity, compensation, maintenance, plasticity: Emerging concepts in cognitive reserve. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2013;17:502–509. [CrossRef]

- Baum JI, Kim IY, Wolfe RR. Protein Consumption and the Elderly: What Is the Optimal Level of Intake? Nutrients. 2016 Jun 8;8(6):359. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dor M, Sirtoli R, Barkai R. The evolution of the human trophic level during the Pleistocene. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2021 Aug;175 Suppl 72:27-56. [CrossRef]

- Bertram L, Bockenhoff A, Demuth I, Duzel S, Eckardt R, Li SC, et al. Cohort profile: The Berlin Aging Study II (BASE-II) International Journal of Epidemiology. 2014;43(3):703–712. [CrossRef]

- Betts M.J., Cardenas-Blanco A., Kanowski M., Jessen F., Düzel E. In vivo MRI assessment of the human locus coeruleus along its rostrocaudal extent in young and older adults. NeuroImage. 2017;163:150–159. [CrossRef]

- Betts MJ, Kirilina E, Otaduy MCG, Ivanov D, Acosta-Cabronero J, Callaghan MF, Lambert C, Cardenas-Blanco A, Pine K, Passamonti L, Loane C, Keuken MC, Trujillo P, Lüsebrink F, Mattern H, Liu KY, Priovoulos N, Fliessbach K, Dahl MJ, Maaß A, Madelung CF, Meder D, Ehrenberg AJ, Speck O, Weiskopf N, Dolan R, Inglis B, Tosun D, Morawski M, Zucca FA, Siebner HR, Mather M, Uludag K, Heinsen H, Poser BA, Howard R, Zecca L, Rowe JB, Grinberg LT, Jacobs HIL, Düzel E, Hämmerer D. Locus coeruleus imaging as a biomarker for noradrenergic dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain. 2019 Sep 1;142(9):2558-2571. [CrossRef]

- 20 August 1385; 8, 28. Black LJ (A), Kimberley Baker, Anne-Louise Ponsonby, Ingrid van der Mei, Robyn M Lucas, Gavin Pereira, Ausimmune Investigator Group, A Higher Mediterranean Diet Score, Including Unprocessed Red Meat, Is Associated with Reduced Risk of Central Nervous System Demyelination in a Case-Control Study of Australian Adults, The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 149, Issue 8, August 2019, Pages 1385–1392, . [CrossRef]

- Black LJ (A), Zhao Y, Peng YC, Sherriff JL, Lucas RM, van der Mei I, Pereira G; Ausimmune Investigator Group. Higher fish consumption and lower risk of central nervous system demyelination. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020 May;74(5):818-824. [CrossRef]

- Black LJ (B), Bowe GS, Pereira G, Lucas RM, Dear K, van der Mei I, Sherriff JL; Ausimmune Investigator Group. Higher Non-processed Red Meat Consumption Is Associated With a Reduced Risk of Central Nervous System Demyelination. Front Neurol. 2019 Feb 19;10:125. [CrossRef]

- Bloemendaal M, Froböse MI, Wegman J, Zandbelt BB, van de Rest O, Cools R, Aarts E. Neuro-Cognitive Effects of Acute Tyrosine Administration on Reactive and Proactive Response Inhibition in Healthy Older Adults. eNeuro. 2018 Apr 30;5(2):ENEURO.0035-17.2018. [CrossRef]

- Bock, F.J., Tait, S.W.G. Mitochondria as multifaceted regulators of cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 21, 85–100 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Boeing H, Bohlscheid-Thomas S, Voss S, Schneeweiss S, Wahrendorf J. The relative validity of vitamin intakes derived from a food frequency questionnaire compared to 24-hour recalls and biological measurements: Results from the EPIC pilot study in Germany. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;26(Suppl 1):S82–S90. [CrossRef]

- Bondareff W., Mountjoy C.Q., Roth M. Loss of neurons of origin of the adrenergic projection to cerebral cortex (nucleus locus ceruleus) in senile dementia. Neurology. 1982;32:164. [CrossRef]

- Boto J, Gkinis G, Roche A, Kober T, Maréchal B, Ortiz N, Lövblad KO, Lazeyras F, Vargas MI. Evaluating anorexia-related brain atrophy using MP2RAGE-based morphometry. Eur Radiol. 2017 Dec;27(12):5064-5072. [CrossRef]

- Bowie, C., Harvey, P. Administration and interpretation of the Trail Making Test. Nat Protoc 1, 2277–2281 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Boyle R., Jollans L., Rueda-Delgado L.M., Rizzo R., Yener G.G., McMorrow J.P., Knight S.P., Carey D., Robertson I.H., Emek-Savaş D.D., et al. Brain-predicted age difference score is related to specific cognitive functions: A multi-site replication analysis. Brain Imaging Behav. 2021;15:327–345. [CrossRef]

- Boyle R., Jollans L., Rueda-Delgado L.M., Rizzo R., Yener G.G., McMorrow J.P., Knight S.P., Carey D., Robertson I.H., Emek-Savaş D.D., et al. Brain-predicted age difference score is related to specific cognitive functions: A multi-site replication analysis. Brain Imaging Behav. 2021;15:327–345. [CrossRef]

- Bozzali M., D’Amelio M., Serra L. Ventral tegmental area disruption in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging. 2019;11:1325–1326. [CrossRef]

- Braak H., Thal D.R., Ghebremedhin E., Del Tredici K. Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: Age categories from 1 to 100 years. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2011;70:960–969. [CrossRef]

- Braak H., Thal D.R., Ghebremedhin E., Del Tredici K. Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: Age categories from 1 to 100 years. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2011;70:960–969. [CrossRef]

- Brettschneider J, Del Tredici K, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Spreading of pathology in neurodegenerative diseases: a focus on human studies. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015 Feb;16(2):109-20. [CrossRef]

- Bucci D, Busceti CL, Calierno MT, Di Pietro P, Madonna M, Biagioni F, Ryskalin L, Limanaqi F, Nicoletti F, Fornai F. Systematic Morphometry of Catecholamine Nuclei in the Brainstem. Front Neuroanat. 2017 Nov 2;11:98. [CrossRef]

- Bursch W, Karwan A, Mayer M, Dornetshuber J, Fröhwein U, Schulte-Hermann R, Fazi B, Di Sano F, Piredda L, Piacentini M, Petrovski G, Fésüs L, Gerner C. Cell death and autophagy: cytokines, drugs, and nutritional factors. Toxicology. 2008 Dec 30;254(3):147-57. [CrossRef]

- Cabeza R., Albert M., Belleville S., Craik F.I.M., Duarte A., Grady C.L., Lindenberger U., Nyberg L., Park D.C., Reuter-Lorenz P.A., et al. Maintenance, reserve and compensation: The cognitive neuroscience of healthy ageing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018;19:772. [CrossRef]

- Cesaro L, Salvi M. Mitochondrial tyrosine phosphoproteome: new insights from an up-to-date analysis. Biofactors. 2010 Nov-Dec;36(6):437-50. [CrossRef]

- Chávez, Mervin & Martinez Cruz, Maria & Nuñez, Victoria & Rojas, Milagros & Gallo, Valeria & Lameda, Victor & Prieto, Dexys & Velasco, Manuel & Bermudez, Valmore & Rojas Quintero, Joselyn. (2017). Nutrition in Depression: Eating the Way to Recovery. EC NUTRITION. 10. 102-108.

- Chen Y, Chen T, Hou R. Locus coeruleus in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2022 Mar 7;8(1):e12257. [CrossRef]

- Cherra SJ, Chu CT. Autophagy in neuroprotection and neurodegeneration: A question of balance. Future Neurol. 2008 May;3(3):309-323. [CrossRef]

- Choi S, DiSilvio B, Fernstrom MH, Fernstrom JD. Effect of chronic protein ingestion on tyrosine and tryptophan levels and catecholamine and serotonin synthesis in rat brain. Nutr Neurosci. 2011 Nov;14(6):260-7. [CrossRef]

- 20 April; 77, 51. Christopher D Gardner, Jennifer C Hartle, Rachael D Garrett, Lisa C Offringa, Arlin S Wasserman, Maximizing the intersection of human health and the health of the environment with regard to the amount and type of protein produced and consumed in the United States, Nutrition Reviews, Volume 77, Issue 4, April 2019, Pages 197–215, . [CrossRef]

- Clewett D.V., Lee T.-H., Greening S., Ponzio A., Margalit E., Mather M. Neuromelanin marks the spot: Identifying a locus coeruleus biomarker of cognitive reserve in healthy aging. Neurobiol. Aging. 2016;37:117–126. [CrossRef]

- Coelho-Júnior HJ, Calvani R, Landi F, Picca A, Marzetti E. Protein Intake and Cognitive Function in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr Metab Insights. 2021 Jun 4;14:11786388211022373. [CrossRef]

- Colzato LS, Jongkees BJ, Sellaro R, Hommel B. Working memory reloaded: tyrosine repletes updating in the N-back task. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013 Dec 16;7:200. [CrossRef]

- Colzato LS, Jongkees BJ, Sellaro R, van den Wildenberg WP, Hommel B. Eating to stop: tyrosine supplementation enhances inhibitory control but not response execution. Neuropsychologia. 2014 Sep;62:398-402. [CrossRef]

- Colzato LS, Steenbergen L, Sellaro R, Stock AK, Arning L, Beste C. Effects of l-Tyrosine on working memory and inhibitory control are determined by DRD2 genotypes: A randomized controlled trial. Cortex. 2016 Sep;82:217-224. [CrossRef]

- Conlay LA, Zeisel SH. Neurotransmitter precursors and brain function. Neurosurgery. 1982 Apr;10(4):524-9. [CrossRef]

- Counts S.E., Mufson E.J. Noradrenaline activation of neurotrophic pathways protects against neuronal amyloid toxicity. J. Neurochem. 2010;113:649–660. [CrossRef]

- Corrigan JD, Hinkeldey MS. Relationships between parts A and B of the Trail Making Test. J Clin Psychol. 1987;43(4):402–409.