Submitted:

14 April 2023

Posted:

17 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

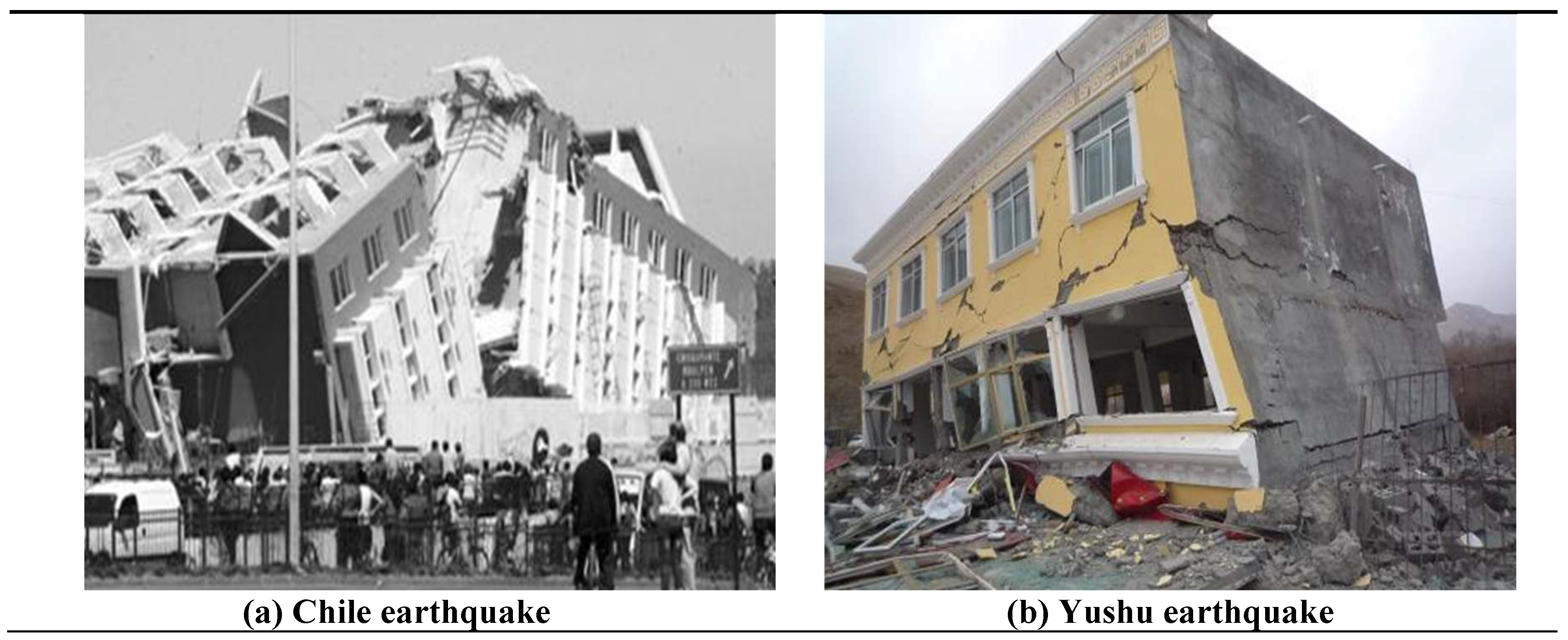

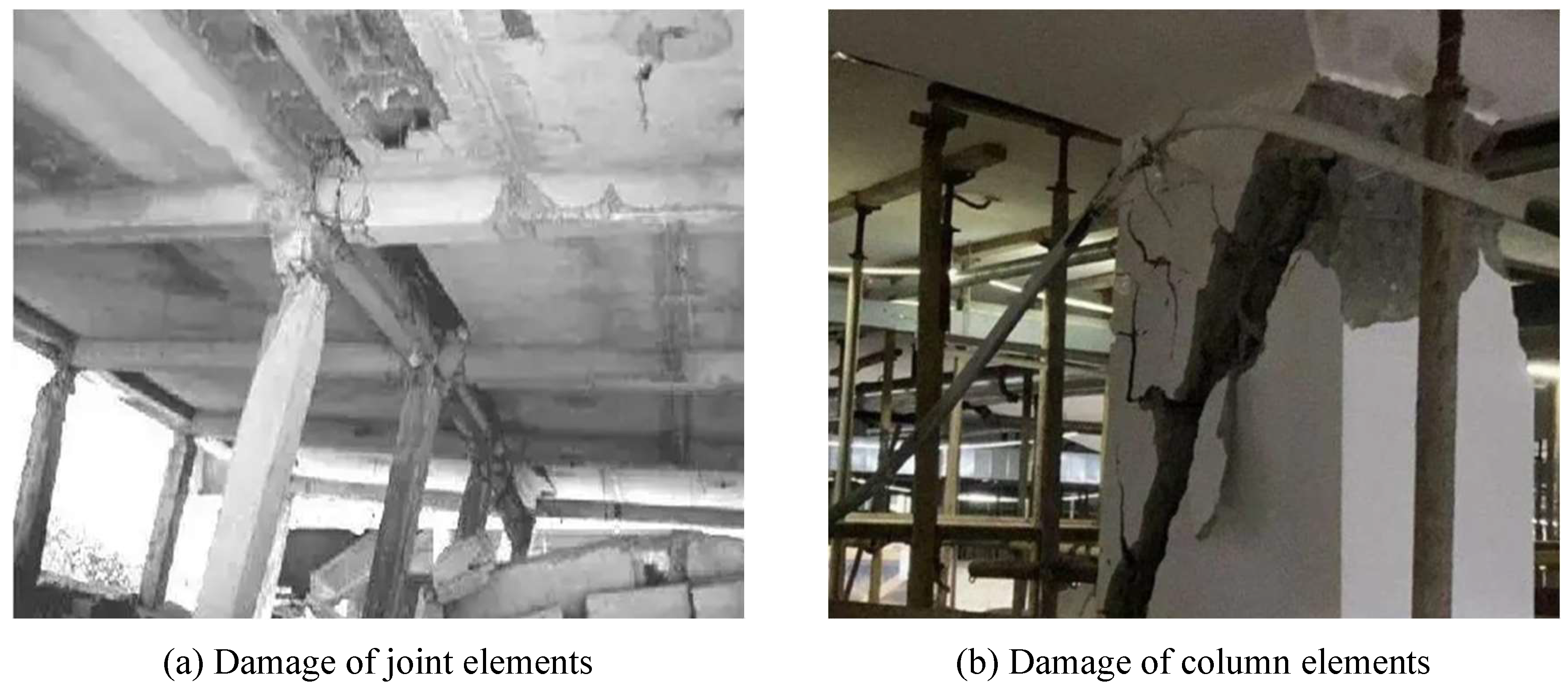

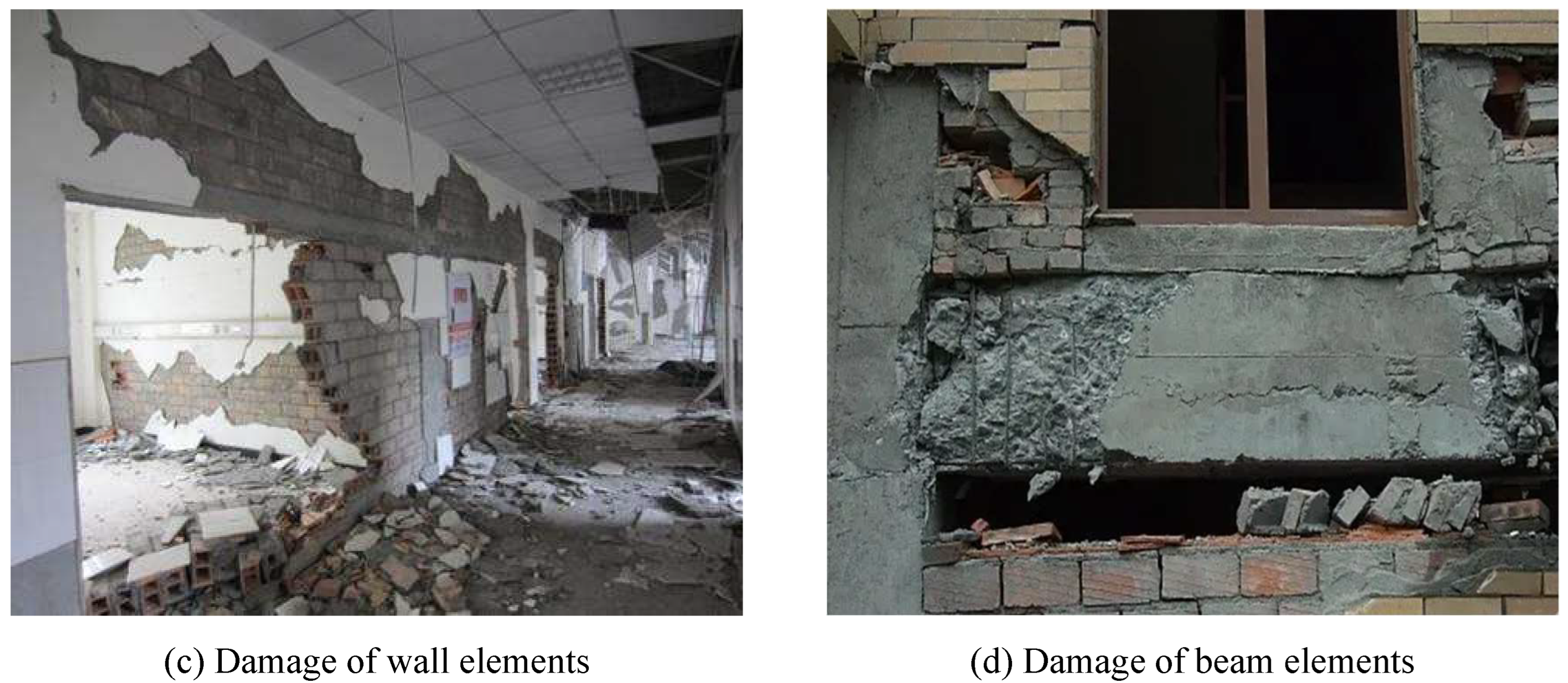

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Studies on Dynamic Behaviors of RC Structural Members

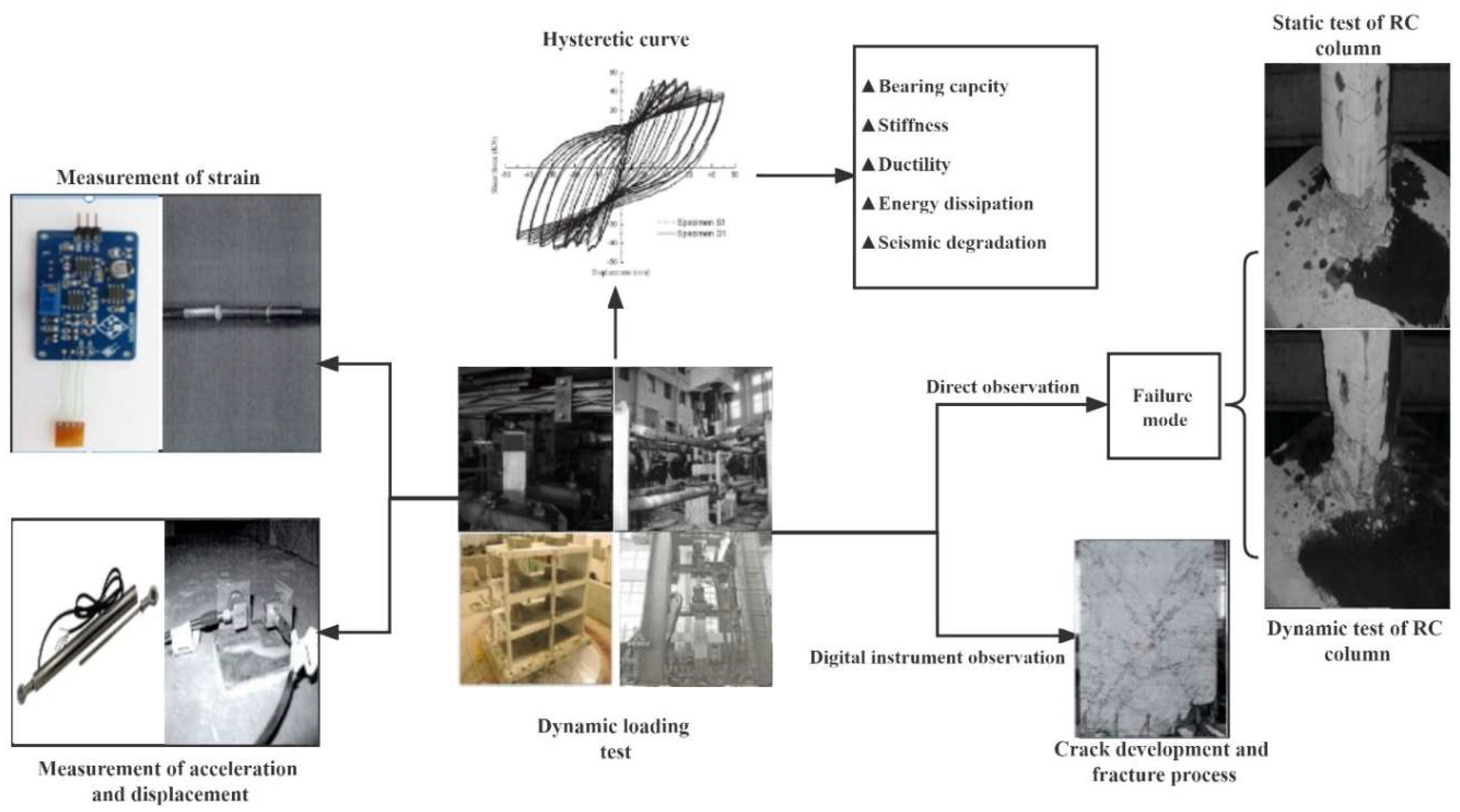

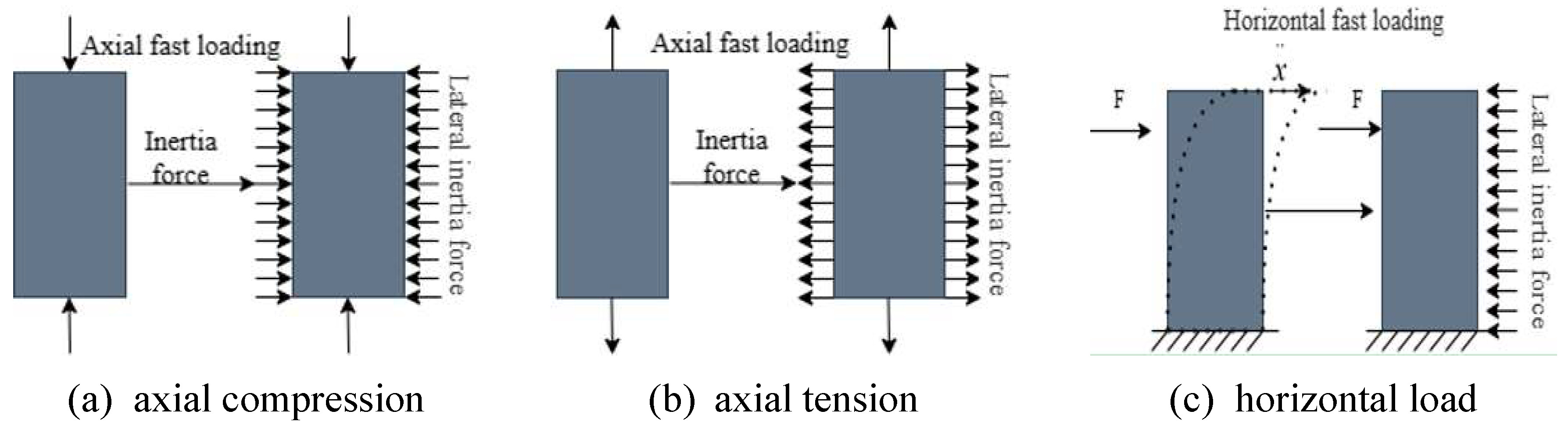

2.1. Overview of Dynamic Loading Tests on Structural Members

2.2. Measurement Methods for Dynamic Loading Test

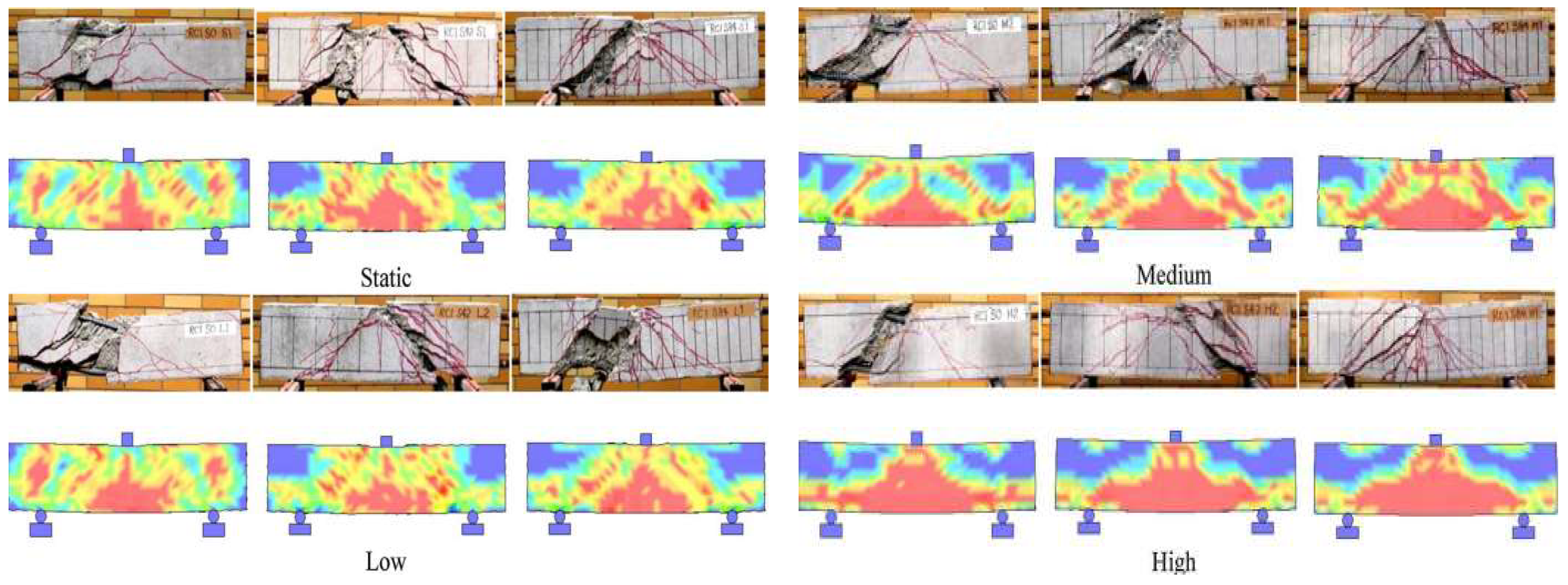

2.3. Summary of Experimental Findings

2.4. Discussion on Dynamic Loading Tests

3. Theoretical Studies on Dynamic Behaviors of RC Structural Members

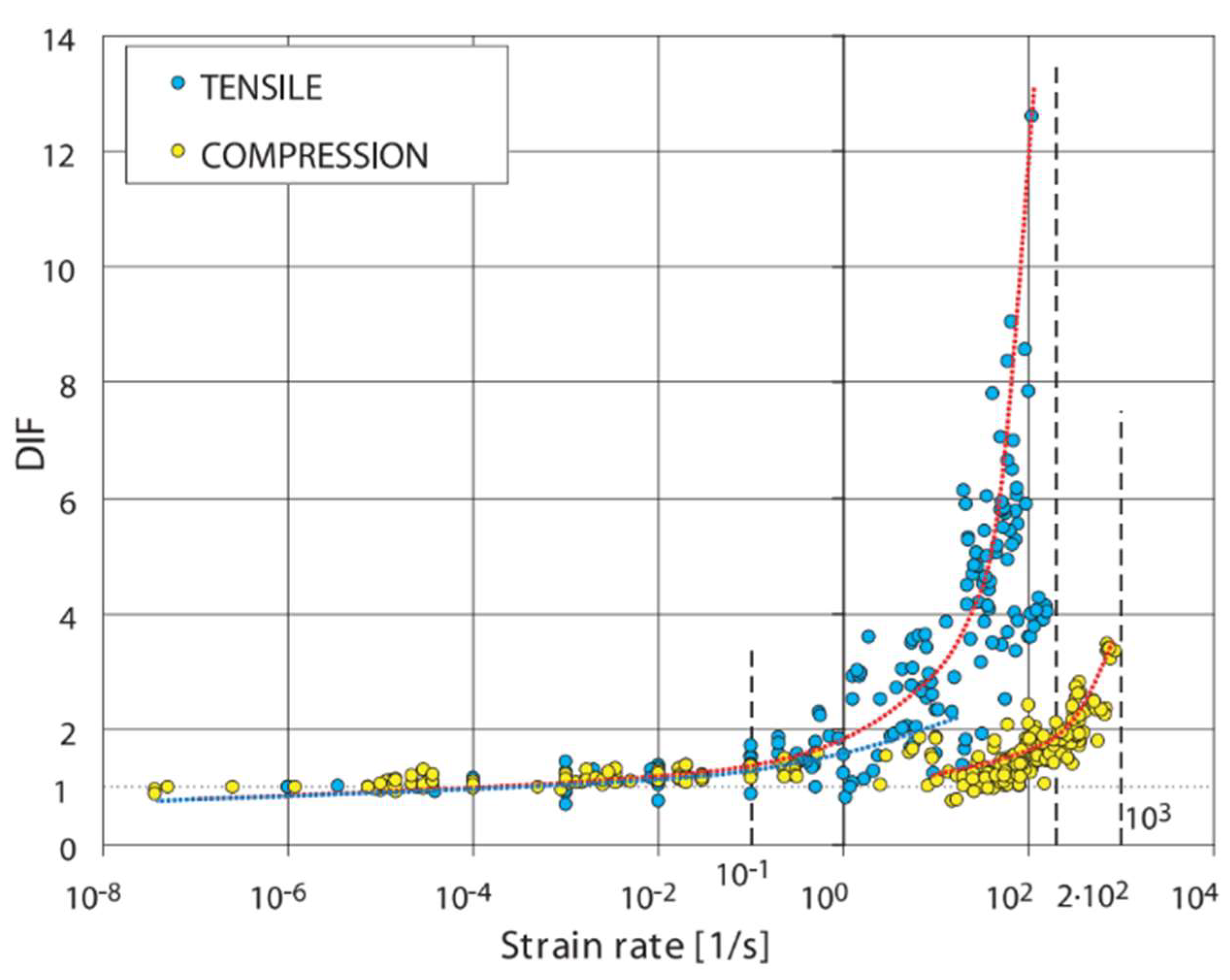

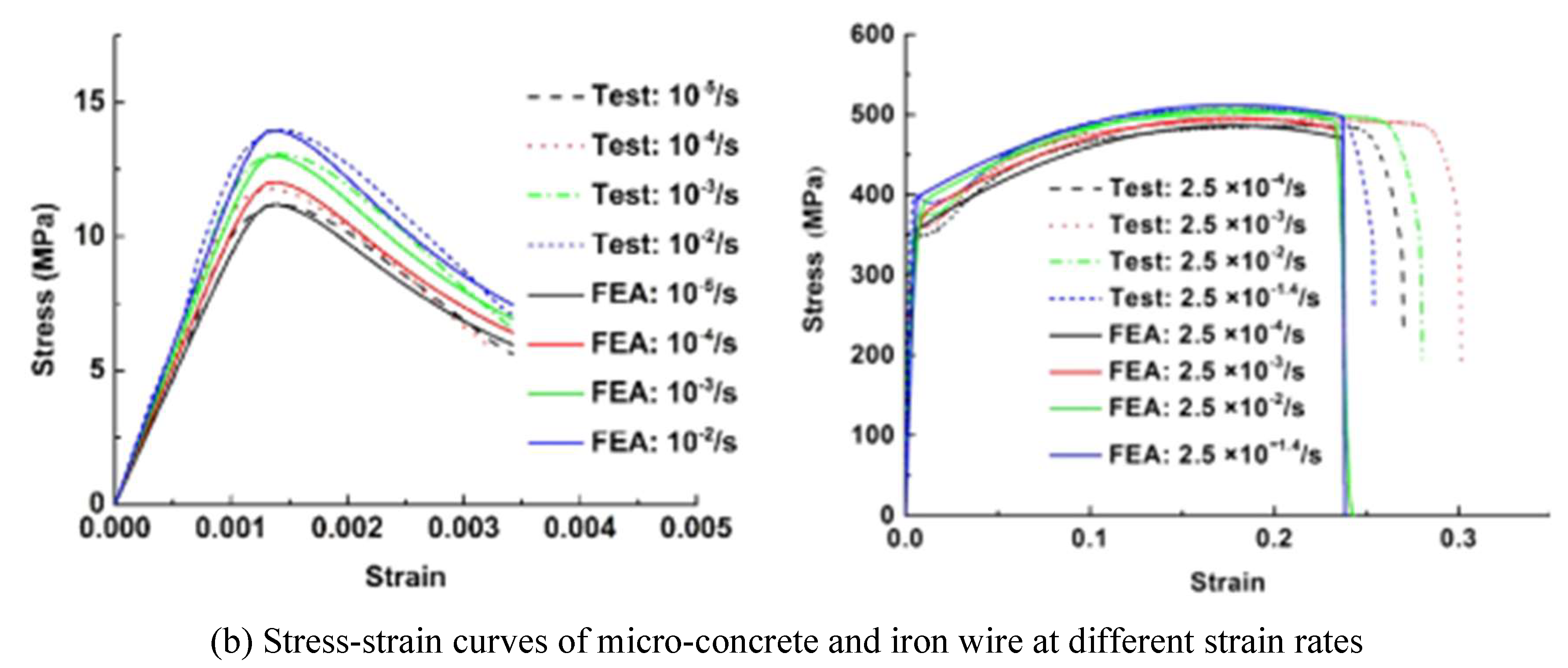

3.1. Dynamic Modified Model at Material Level

3.2. Dynamic Modified Model at Member Level

3.3. Discussion on Dynamic Modified Models

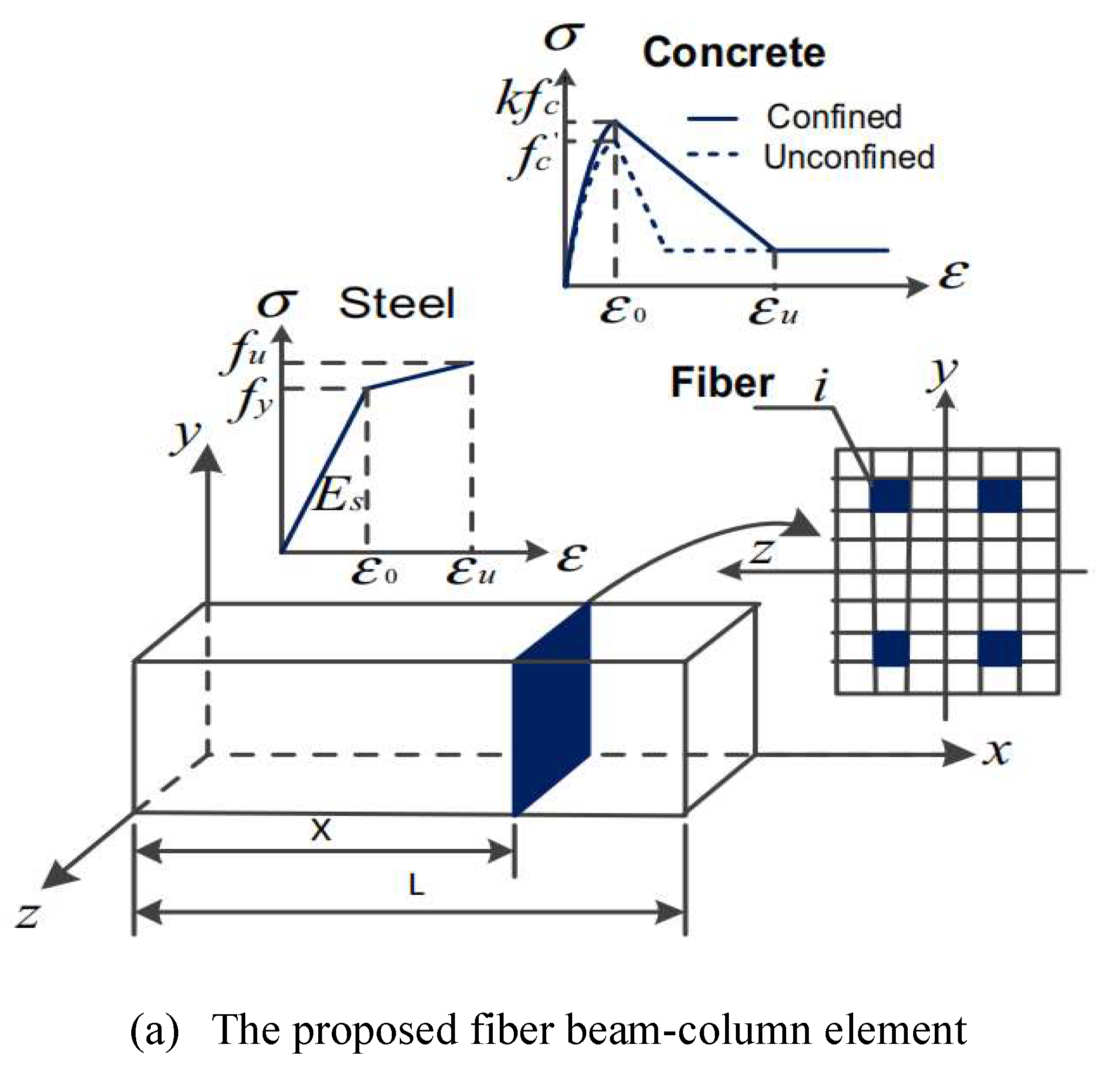

4. Numerical Studies on Dynamic Behaviors of RC Structural Members

4.1. Overview of Numerical Studies Considering Dynamic Effect

4.2. Numerical Model for Simulating Structural Dynamic Behaviors

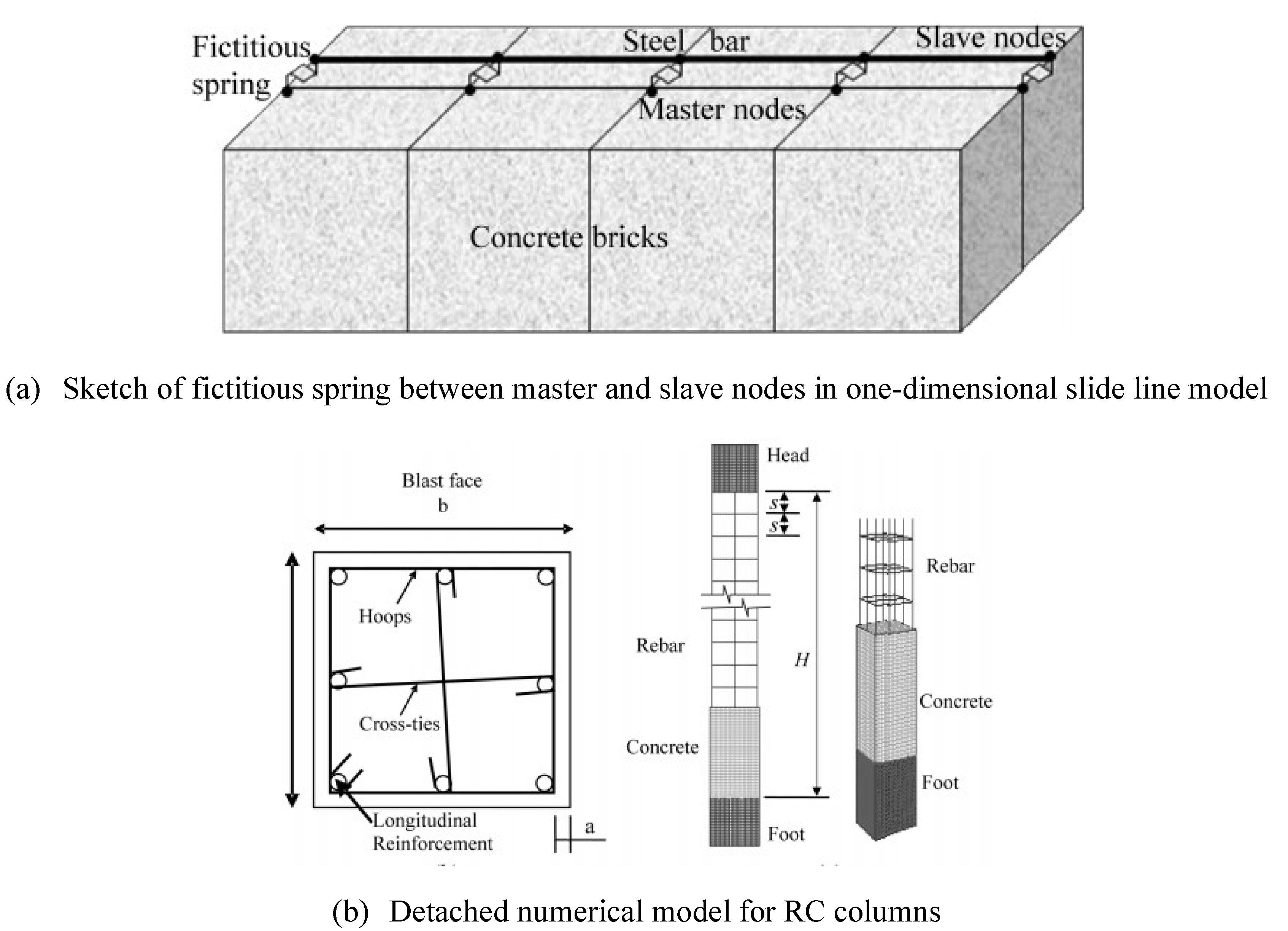

4.2.1. Finite Element Model Considering Dynamic Effect

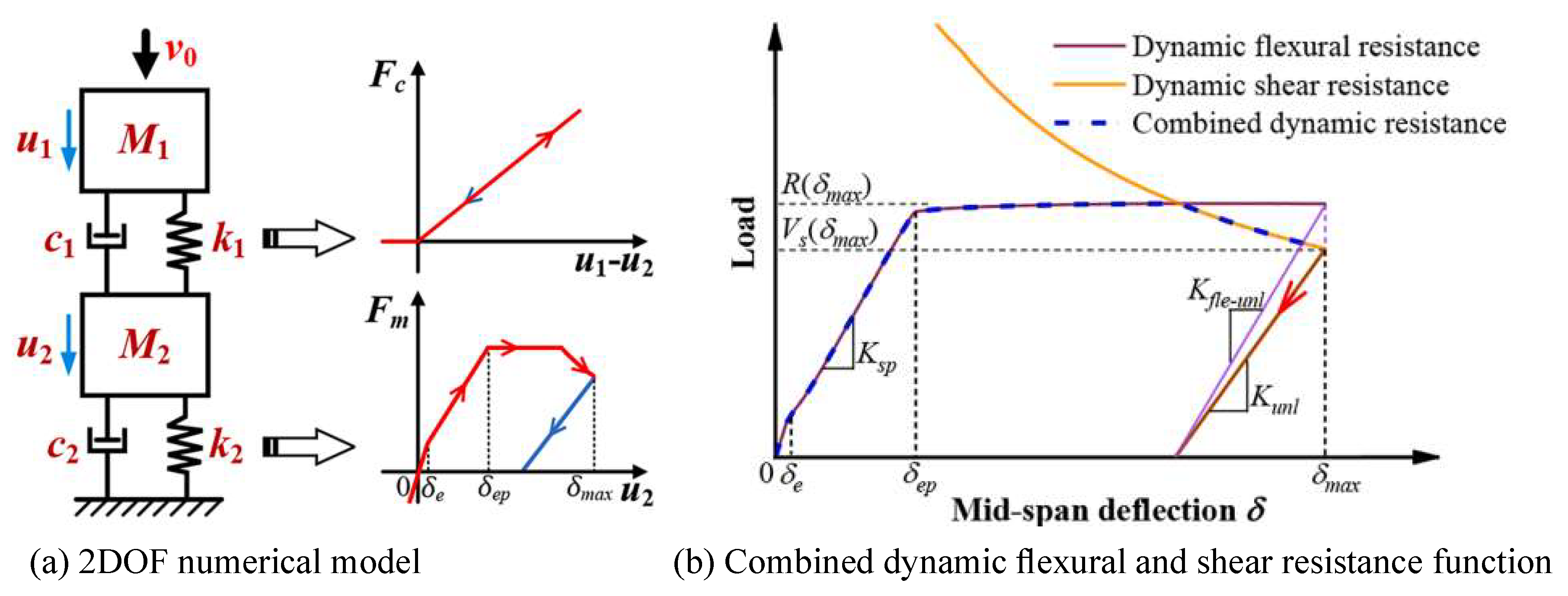

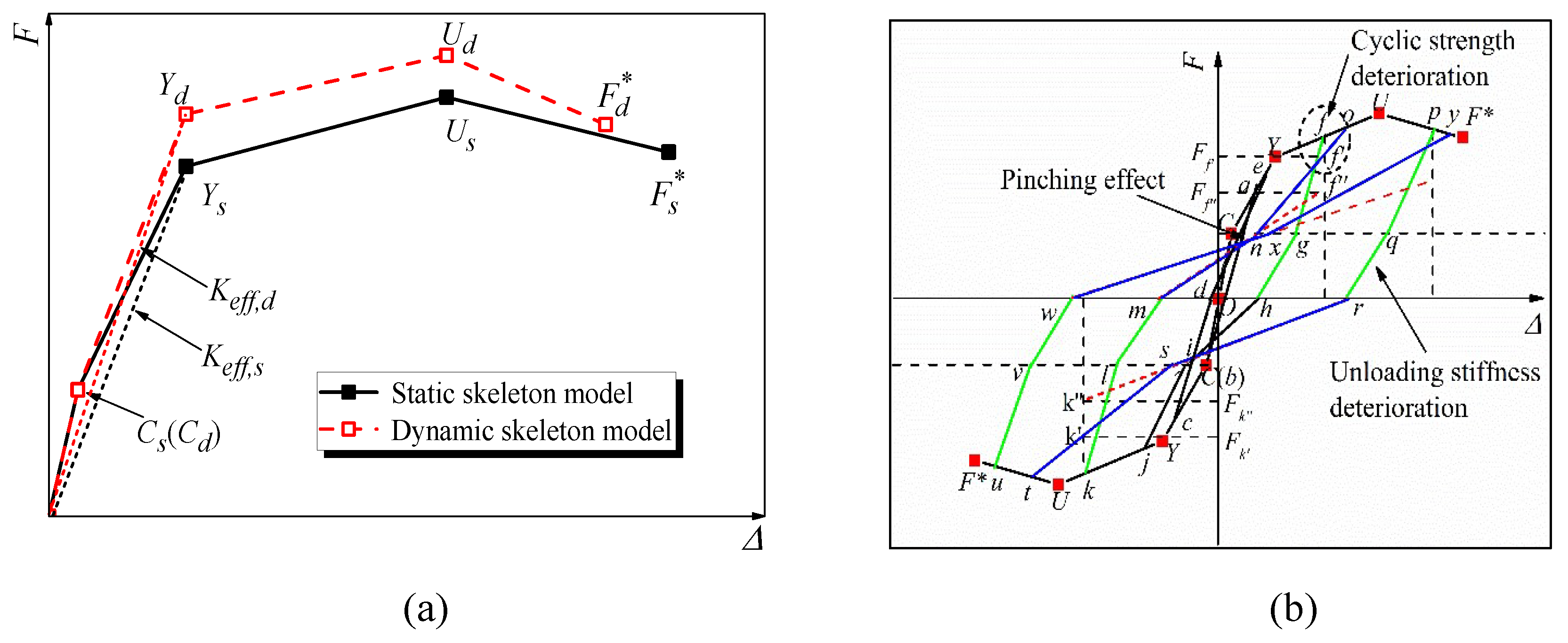

4.2.2. Hysteretic Model Considering Dynamic Effect

| Degradation effect factors | Relevant studies | |

|---|---|---|

| Single factor |

|

Clough [131], Takeda [132], Wen [135], Riddell[136], Takayanagi and Schnobrich [137], Zhu and Zhang [138], Saatcioglu et al. [139], Xu [140], Qu and Ye[141], |

|

Ambrisi and Filippou [142] | |

| Multiple factor |

|

Gu et al. [143], Zheng et al. [144], Zheng et al.[145], Erberik [146], Wang et al. [147] |

|

Roufeial and Meyer [148], Park and Ang [134], Ozcebe and Saatcioglu [133], Dowell et al. [149], Miramontes et al. [150], Pincheira et al. [151], Mostaghel and Byrd [152], Kunnath et al. [153], Yan et al. [154], Wang et al. [155], Yu et,al. [156], Sezen and Chowdhury [157], Leborgne and Ghannoum [158], Chao and Loh [159], Guo and Yang [160], Yu et al. [161], Cai et al. [162], Zhao and Dun [163], Huang et al. [164] | |

|

Song and Pincheira [165], Ibarra et al. [166], Guo and Long [167], Li [111] | |

4.3. Discussion on Numerical Simulation Works

5. Concluding Remarks

References

- Fu, H.C.; Erki, M.A.; Seckin, M. Review of Effects of Loading Rate on Concrete in Compression. Journal of Structural Engineering 1991, 117, 3645-3659. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Huo, L. Multiaxial seismic dynamic effect of RC structure; 2021.

- Wang, D.B.; Fan, G.X.; Zhang, H. Dynamic behaviors of reinforced concrete columns under multi-dimensional dynamic loadings. Journal of Vibration and Shock 2016.

- Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Han, Q. Dynamic performance of flexure-failure-type rectangular RC columns under low-velocity lateral impact. International Journal of Impact Engineering 2023, 175. [CrossRef]

- Witarto, W.; Lu, L.; Roberts, R.H.; Mo, Y.L.; Lu, X. Shear-critical reinforced concrete columns under various loading rates. Frontiers of Structural and Civil Engineering 2014, 8, 362-372. [CrossRef]

- Reinschmidt, K.F.; Hansen, R.J.; Yang, C.Y. Dynamic tests of reinforced concrete columns. In Proceedings of the Journal Proceedings, 1964; pp. 317-334.

- Adhikary, S.D.; Li, B.; Fujikake, K. Dynamic behavior of reinforced concrete beams under varying rates of concentrated loading. International Journal of Impact Engineering 2012, 47, 24-38. [CrossRef]

- hongnan, L.; Li, m. Dynamic test and numericalsimulation of reinforced concrete beams. 2015.

- Adhikary, S.D.; Li, B.; Fujikake, K. Effects of high loading rate on reinforced concrete beams. Aci Structural Journal 2014, 111, 651-660. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, H.N. Effects of loading rate on reinforced concrete beams. In Proceedings of the 15th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Lisboa, Portugal, 2011.

- Xiao, S.; Zhang, H. Effects of Loading Rate on the Shear Behaviors of RC Beams. Journal of Water Resources and Architectural Engineering 2018.

- Marder, K.J.; Motter, C.J.; Elwood, K.J.; Clifton, G.C. Effects of variation in loading protocol on the strength and deformation capacity of ductile reinforced concrete beams. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2018, 47, 2195-2213. [CrossRef]

- Fujikake, K.; Li, B.; Soeun, S. Impact response of reinforced concrete beam and its analytical evaluation. Journal of Structural Engineering 2009, 135, 938-950. [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, S.D.; Li, B.; Fujikake, K. Strength and behavior in shear of reinforced concrete deep beams under dynamic loading conditions. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2013, 259, 14–28. [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Chen, J.M.; Xu, N. Test on strain rate effects and its simulation with dynamic damaded plasticity model for RC shear walls. Engineering Mechanics 2012, 29, 39-287.

- Zhang,Xiaoli. Effects of Loading Rates on Seismic Behavior of Reinforced Concrete High Shear Walls. Dalian University of Technology, 2012.

- Yupu, S.; Xiaoli, Z. INFLUENCE OF STRAIN RATE ON EARTHQUAKE RESISTANCE EFFECT OF REINFORCED CONCRETE SHEAR WALL. Industrial Construction 2012, 42, 7-11.

- Xu, N. Study on the performance test and numerical simulation of reinforced concrete shear wall under rapid loading. Hunan University, 2012.

- XU Bin ; Jun-ming, C.; , X.N. TEST ON STRAIN RATE EFFECTS AND ITS SIMULATION WITH DYNAMIC DAMADED PLASTICITY MODEL FOR RC SHEAR WALLS. ENGINEERING MECHANICS 2012, 29, 39-45.

- Chung, L.; Shah, S.P. Effect of loading rate on anchorage bond and beam-column joints. Structural Journal 1989, 86, 132-142.

- Wang Licheng, F.G., Qin Quan,Song Yupu. Experimental study on seismic behavior of reinforced concrete frame joints with consideration of strain rate effect. 2014.

- Guoxi, F.; Yupu, S.; Licheng, W. - STUDY ON THE SEISMIC PERFORMANCE OF REINFORCED CONCRETE BEAM-COULUMN JOINTS UNDER DIFFERENT STRAIN RATES. - INDUSTRIAL CONSTRUCTION 2014, - 44, - 1, doi:-.

- Pan,Haohao. Effects of strain rate sensitivity on dynamic properties ofreinforced concrete materials and beam-column joints. Dalian University of Technology, 2012.

- Qin, q. Study on Seismic Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Frame Jointswith the Consideration of Strain Rate Effect. Dalian University of Technology, 2013.

- Licheng,, W.; Guoxi,, F.; Quan,, Q.; Yupu, S. Experimental study on seismic behavior of reinforced concrete frame joints with consideration of strain rate effect. Journal of Building Structures 2014, 35, 38-45.

- CEB. CEB-FIP Model Code 1990, First Draft. CEB Bulletin D'information 1990, 195.

- Lin, f.; Gu, x.; Kuang, x.; Yin, x. Constitutive Models for Reinforcing Steel Barsunder High Strain Rates. Journal of Building Materials 2008, 011, 14-20.

- Li, M. Effects of rate-dependent properties of material on dynamicproperties of reinforced concrete structural. Dalian University of Technology, 2011.

- Ross, C.A.; Tedesco, J.W.; Kuennen, S.T. EFFECTS OF STRAIN-RATE ON CONCRETE STRENGTH. Aci Material Journal 1995, 92, 37-47.

- Ghannoum, W.; Saouma, V.; Haussmann, G.; Polkinghorne, K.; Eck, M.; Kang, D.H. Experimental investigations of loading rate effects in reinforced concrete columns. Journal of Structural Engineering 2012, 138, 1032-1041. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.J.; Sorensen, A.D. Review of strain rate effects for UHPC in tension. Construction and Building Materials 2017, 153, 846-856. [CrossRef]

- Bertero, V.; Rea, D.; Mahin, S.; Atalay, M. Rate of loading effects on uncracked and repaired reinforced concrete members. In Proceedings of the Proceedings, Fifth World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Rome, 1973; pp. 1461-1470.

- Shah, S.P.; Wang, M.L.; Lan, C. Model concrete beam-column joints subjected to cyclic loading at two rates. Materials and Structures 1987, 20, 85-95. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.M.; Shah, S.P. Response of reinforced concrete beams at high strain rates. ACI Structural Journal 1998, 95, 705-715.

- Gutierrez, E.; Magonette, G.; Verzeletti, G. Experimental studies of loading rate effects on reinforced concrete columns. Journal of Engineering Mechanics 1993, 119, 887-904. [CrossRef]

- Orozco, G.; Ashford, S. Effects of large velocity pulses on reinforced concrete bridge columns PEER Report 2002/23; Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center University of California, Berkeley, California, 2002.

- Bousias, S.N.; Verzeletti, G.; Fardis, M.N.; Gutierrez, E. Load-Path Effects in Column Biaxial Bending with Axial Force. Journal of Engineering Mechanics 1995, 121, 596-605. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, N. Performance of beam to column bridge joints subjected to a large velocity pulse; Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center: University of California, Berkeley, California, 2002.

- White, T.W.; Soudki, K.A.; Erki, M.A. Response of RC Beams Strengthened with CFRP Laminates and Subjected to a High Rate of Loading. Journal of Composites for Construction 2001, 5, 153-162. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Park, R.; Tanaka, H. Constitutive behaviour of high strength concrete under dynamic loading. ACI Structural Journal 2000, 97, 619-629.

- Zhang, X.X.; Ruiz, G.; Yu, R.C. Experimental study of combined size and strain rate effects on the fracture of reinforced concrete. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2008, 20, 544-551. [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, T.; Sanuki, S.; Miyakawa, M.; Fujikake, K. Influence of loading rate on shear failure resistance of RC beams. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2011, 82, 229-234. [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, S.D.; Li, B.; Fujikake, K. Residual resistance of impact damaged reinforced concrete beams. Magazine of Concrete Research 2015, 67, 364 –378. [CrossRef]

- Perry, S.H.; Alshaikh, A.H.; Cheong, H.K. Influence of strain rate on laterally confined concrete columns subjected to cyclic loading. Journal of Materials Research 1986, 1, 382-389. [CrossRef]

- GuiLan, Y. THE RESEARCH ON STRAIN RATE EFFECT OF DYNAMIC BEHAVIORS OFREINFORCED CONCRETE REMEMBERS. 硕士, Harbin Institute of Technology, 2010.

- Shiyun,, X.; Wenbo,, C.; Haohao, P. Experimental study on mechanical behavior of reinforced concrete beams at different loading rates. Journal of Building Structures 2012, 33, 142-146.

- Zou, D.J.; Liu, T.J.; Teng, J.; Yan, G.L. Strain rate effect on uniaxial compressive behaviour of concrete columns. Zhendong yu Chongji/Journal of Vibration and Shock 2012, 31, 145-150.

- Yuan, J.; Weijian, Y.I. Tests for effects of loading rate on shear behaviors of RC beams. Journal of Vibration and Shock 2019.

- Wang, D.B.; Li, H.N.; Li, G. Experimental study on dynamic mechanical properties of reinforced concrete column. Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites 2013, 32, 1793-1806. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z. Dynamic loading experiment and numerical simulation study on reinforced concrete columns. Hunan University, Changsha, Hunan (in Chinese), 2012.

- Zeng, X. Experimental and numerical study of behaviors of RC beams and columns underimpact loadings and rrapid loadings. Hunan University, 2014.

- Ye, J.-B.; Cai, J.; Chen, Q.-J.; Liu, X.; Tang, X.-L.; Zuo, Z.-L. Experimental investigation of slender RC columns under horizontal static and impact loads. Structures 2020, 24, 499-513. [CrossRef]

- Zhou hongyu; Xing xiaoshuai; Xie yongping; Yuan hui. Experimental Study on Dynamic Loading Size Effect of RC Beam-Column. Journal of Basic Science and Engineering 2020, 28, 1187-1196. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Zeng, L.; Liu, Y.; Mo, J.; Ma, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J. Experimental study on the dynamic behavior of T-shaped steel reinforced concrete columns under impact loading. Engineering Structures 2020, 208. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Chu, Y. Experimental investigation on cantilever square CFST columns under lateral continuous impact loads. Journal of Constructional Steel Research 2022, 196. [CrossRef]

- Mutsuyoshi, H.; Machida, A. Dynamic properties of reinforced concrete piers. In Proceedings of the 8th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, San Francisco, U.S., 1984.

- Otani, S.; Kaneko, T.; Shiohara, H. Strain rate effect on performance of reinforced concrete members; Kajima Technical Research Institute, Kajima Corporation: Japan, 2003.

- Wang , D.B. Dynamic Effects on Seismic Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Column. Dalian University of Technology, 2013.

- Long, Y. Study on fast loading test and dynamic hysteresis law of reinforced concrete column. Hunan University, 2010.

- Zhang, h. Strain rate effect of materials on seismic response of reinforced concrete frame-wall structure. Dalian University of Technology, 2012.

- Liu, L. Study on seismic behavior of RC columns in flexural-shear failure. Hunan University, 2018.

- Wang, D.B.; Li, H.N.; Li, G. Experimental tests on reinforced concrete columns under multi-dimensional dynamic loadings. Construction and Building Materials 2013, 47, 1167-1181. [CrossRef]

- WANG, D.; LI, H. Effects of strain rate on dynamic behavior of reinforced concrete column. JOURNAL OF EARTHQUAKE ENGINEERING AND ENGINEERING VIBRATION 2011, 31, 67-72.

- Zielinski, A.J.; Reinhardt, H.W.; Körmeling, H.A. Experiments on concrete under uniaxial impact tensile loading. Matériaux et Construction 1981, 14, 103-112. [CrossRef]

- Yon, J.H.; Hawkins, N.M.; Kobayashi, A.S. Strain-rate sensitivity of concrete mechanical properties. ACI Materials Journal 1992, 89, 146-153.

- Cadoni, E.; Labibes, K.; Berra, M. High-strain-rate tensile behaviour of concrete. Magazine of Concrete Research 2000, 52, 365-370. [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Yan, D.; Yuan, Y. Response of concrete to dynamic elevated-amplitude cyclic tension. ACI Materials Journal 2007, 104, 561.

- Chen, X.; Bu, J.; Xu, L. Effect of strain rate on post-peak cyclic behavior of concrete in direct tension. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 124, 746-754. [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Lin, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y. A STUDY ON DIRECT TENSILE PROPERTIES OF CONCRETE AT DIFFERENT STRAIN RATES. CHINA CIVIL ENGINEERING JOURNAL 2005, 38, 97-103.

- Xiao, S.; Tian, Z. Experimental study on the uniaxial dynamic tensile damage of concr ete. CHINA CIVIL ENGINEERING JOURNAL 2008, 41, 14-20.

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X. Experimental research on effects of strain rate on tensile stress-strain curve of concrete in axial tension condition. Building Structure 2015, 71-74.

- Yan, D.M.; Lin, G. Experimental Study on the Uniaxial Dynamic CompressionProperties of Concrete. Water Sciences and Engineering Technology 2005, 8-10.

- Goldsmith, W. Dynamic behavior of concrete. Experimental Mechanics 1966, 6, 65-79.

- Watson, A.J.; Hughes, B.P. Compressive strength and ultimate strain of concrete under impact loading. Magazine of Concrete Research 1978, 30, 189-199. [CrossRef]

- Grote, D.L.; Park, S.W.; Zhou, M. Dynamic behavior of concrete at high strain rates and pressures: I. experimental characterization. International Journal of Impact Engineering 2001, 25, 869-886. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.S.; Ma, L.J.; Dou, Y.M.; Zhou, J. Effect of strain rate on the compressive mechanical properties of concrete. Advanced Materials Research 2012, 450-451, 244-247.

- Guo, Y.B.; Gao, G.F.; Jing, L.; Shim, V.P.W. Response of high-strength concrete to dynamic compressive loading. International Journal of Impact Engineering 2017, 108, 114-135. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhao, P. Experimental study and constitutive model of the whole process of concrete compression under different strain rates. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 1997, 7, 72-77.

- Chang, K.C.; Lee, G.C. Strain rate effect on structural steel under cyclic loading. Journal of Engineering Mechanics 1987, 113, 1292-1301. [CrossRef]

- Restrepo-Posada, J.I.; Dodd, L.L.; Park, R.; Cooke, N. Variables affecting cyclic behavior of reinforcing steel. Journal of Structural Engineering 1994, 120, 3178-3196. [CrossRef]

- Soroushian, P.; Choi, K.B. Steel mechanical properties at different strain rates. Journal of Structural Engineering 1987, 113, 663-672. [CrossRef]

- Cadoni, E.; Fenu, L.; Forni, D. Strain rate behaviour in tension of austenitic stainless steel used for reinforcing bars. Construction and Building Materials 2012, 35, 399-407. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, H. Dynamic test and constitutive model for reinforcing steel. China Civil Engineering Journal 2010, 43, 70-75.

- Reinhardt, H.W.; Rossi, P.; Mier, J.G.M.V. Joint investigation of concrete at high rates of loading. Materials and Structures 1990, 23, 213-216. [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.A.; Jerome, D.M.; Tedesco, J.W.; Hughes, M.L. Moisture and strain rate effects on concrete strength. ACI Materials Journal 1996, 93, 293-300.

- Cadoni, E.; Labibes, K.; Albertini, C.; Berra, M.; Giangrasso, M. Strain-rate effect on the tensile behaviour of concrete at different relative humidity levels. Materials and Structures 2001, 34, 21. [CrossRef]

- Ranjith, P.G.; Jasinge, D.; Song, J.Y.; Choi, S.K. A study of the effect of displacement rate and moisture content on the mechanical properties of concrete: Use of acoustic emission. Mechanics of Materials 2008, 40, 453-469. [CrossRef]

- Filiatrault, A.; Holleran, M. Stress-strain behavior of reinforcing steel and concrete under seismic strain rates and low temperatures. Materials and Structures 2001, 34, 235-239. [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.M.; Xu, W. Strain-rate sensitivity of concrete: influence of temperature. Advanced Materials Research 2011, 243-249, 453-456. [CrossRef]

- Pajak, M. The influence of the strain rate on the strength of concrete taking into account the experimental techniques. Laval Théologique Et Philosophique 2011, 39, 423-428.

- Chen, X.; Wu, S.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Qin, A. Effect of testing method and strain rate on stress-strain behavior of concrete. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2013, 25, 1752-1761. [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, P.H.; Perry, S.H. Compressive behaviour of concrete at high strain rates. Materials and Structures 1991, 24, 425-450. [CrossRef]

- Barpi, F. Impact behaviour of concrete: a computational approach. Engineering Fracture Mechanics 2004, 71, 2197-2213. [CrossRef]

- Georgin, J.F.; Reynouard, J.M. Modeling of structures subjected to impact: Concrete behavior under high strain rate. Cement and Concrete Composites 2003, 25, 131-143.

- Lorefice, R.; Etse, G.; Carol, I. Viscoplastic approach for rate-dependent failure analysis of concrete joints and interfaces. International Journal of Solids and Structures 2008, 45, 2686-2705. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, R.R.; Simone, A.; Sluys, L.J. An analysis of dynamic fracture in concrete with a continuum visco-elastic visco-plastic damage model. Engineering Fracture Mechanics 2008, 75, 3782-3805. [CrossRef]

- Eibl, J.; Schmidt-Hurtienne, B. Strain-rate-sensitive constitutive law for concrete. Journal of Engineering Mechanics 1999, 125, 1411-1420. [CrossRef]

- Ragueneau; Frédéric; Gatuingt; Fabrice. Inelastic behavior modelling of concrete in low and high strain rate dynamics. Computers and Structures 2003, 81, 1287-1299. [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.D.; Li, J. Stochastic damage constitutive model for concrete considering strain rate effect. Key Engineering Materials 2009, 400-402, 251-256. [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.C.; Erki, M.A.; Seckin, M. Review of effects of loading rate on reinforced concrete. Journal of Structural Engineering 1991, 117, 3660-3679. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Hao, H. Influence of the concrete DIF model on the numerical predictions of RC wall responses to blast loadings. Engineering Structures 2014, 73, 24-38. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, K.M.; Cho, J.Y. Investigation into pure rate effect on dynamic increase factor for concrete compressive strength. Procedia Engineering 2017, 210, 11-17. [CrossRef]

- Malvar, L.J. Review of Static and Dynamic Properties of Steel Reinforcing Bars. Aci Materials Journal 1998, 95, 609-616.

- Tedesco, J.W.; Ross, C.A. Strain-rate-dependent constitutive equations for concrete. Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology 1998, 120, 398-405. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Zhang, J. Experimental study on dynamic compression of concrete under load history. Journal of Dalian University of Technology 2011, 51, 6.

- Johnson, G.R.; Cook, W.H. A Constitutive Model and Data for Metals Subjected to Large Strains, High Strain Rates and High Temperatures. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Ballistics, The Hague, Netherlands, 1983; pp. 541-547.

- Morquio, A.; Riera, J.D. Size and strain rate effects in steel structures. Engineering Structures 2004, 26, 669-679. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, J.A.; Rusinek, A.; Klepaczko, J.R. Constitutive relation for steels approximating quasi-static and intermediate strain rates at large deformations. Mechanics Research Communications 36, 419-427. [CrossRef]

- Cotsovos, D.M.; Stathopoulos, N.D.; Zeris, C.A. Behavior of RC beams subjected to high rates of concentrated loading. Journal of Structural Engineering 2008, 134, 1839–1851. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, T.; Wang, Z.; Ning, J. Failure behaviors of reinforced concrete beams subjected to high impact loading. Engineering Failure Analysis 2015, 56, 233-243. [CrossRef]

- Li,Rouhan. Study on Seismic Performance of Reinforced Concrete Structure Considering Dynamic Effects. Dalian University of Technology, 2020.

- Fan, G.X. Study on the dynamic mechanical properties of reinforced concrete beam-column joints. Dalian University of Technology, 2015.

- Li, H.N.; Li, R.H.; Li, C.; Wang, D.B. Development of hysteretic model with dynamic effect and deterioration for seismic-performance analysis of reinforced concrete structures. Journal of Structural Engineering 2020, 146, 04020215. [CrossRef]

- Valipour, H.R.; Luan, H.; Foster, S.J. Analysis of RC beams subjected to shock loading using a modified fibre element formulation. Computers and Concrete 2009, 6, 377-390. [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Liang, T.; Long, Y. Strain rate effects on dynamic behavior of reinforcement concrete columns with various reinforcement ratio. Journal of Civil,Architectural & Environmental Engineering 2012.

- Sharma, A.; Ožbolt, J. Influence of high loading rates on behavior of reinforced concrete beams with different aspect ratios-A numerical study. Engineering Structures 2014, 79, 297-308. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.Y. Numerical study of dynamic behaviour of RC beams under cyclic loading with different loading rates. Magazine of Concrete Research 2015, 67, 325-334. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.H.; Li, H.N.; Li, C. Seismic performance assessment of RC frame structures subjected to far-field and near-field ground motions considering strain rate effect. International Journal of Structural Stability and Dynamics 2018, 18, 1850127. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, H.N.; Li, C.; Cao, G.W. Experimental and numerical investigations on seismic responses of reinforced concrete structures considering strain rate effect. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 173, 672-686. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.H.; Li, C.; Li, H.N.; Yang, G.; Zhang, P. Improved estimation on seismic behavior of RC column members: A probabilistic method considering dynamic effect and structural parameter uncertainties. Structural Safety 2023, 101. [CrossRef]

- Stochino, F.; Carta, G. SDOF models for reinforced concrete beams under impulsive loads accounting for strain rate effects. Nuclear Engineering & Design 2014, 276, 74-86. [CrossRef]

- Domenico; Asprone; and; Raffaele; Frascadore; and; Marco; Di; Ludovico; and. Influence of strain rate on the seismic response of RC structures. Engineering Structures 2012, 35, 29-36.

- Krauthammer, T.; Shanaa, H.M.; Assadi, A. Response of structural concrete elements to severe impulsive loads. Computers & Structures 1994, 53, 119-130. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Study on the Seismic Analysis Method of Structure ConsideringStrain Rate Effect. Dalian University of Technology, 2013.

- Liu, H.; LI;Hongnan. - SEISMIC-COLLAPSE ANALYSIS OF REINFORCED CONCRETE FRAME STRUCTURE CONSIDERING CUMULATIVE DAMAGE AND STRAIN RATE EFFECT. - Engineering Mechanics 2018, - 35, - 87, doi:- 10.6052/j.issn.1000-4750.2016.12.0991.

- Zhao, D.B.; Yi, W.J.; Kunnath, S.K. Numerical simulation and shear resistance of reinforced concrete beams under impact. Engineering Structures 2018, 166, 387-401. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, Z.X.; Hao, H. Bond slip modelling and its effect on numerical analysis of blast-induced responses of RC columns. Structural Engineering & Mechanics 2009, 32, 251-267. [CrossRef]

- Rouchette, A.; Zhang, W.P.; Chen, H. Simulation of Flexural Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Beams under Impact Loading. Applied Mechanics & Materials 2013, 351-352, 1018-1023. [CrossRef]

- Guner, S.; Vecchio, F.J. Analysis of shear-critical reinforced concrete plane frame elements under cyclic loading. Journal of Structural Engineering 2011, 137, 834-843. [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.C.; Wu, H.; Fang, Q. An improved 2DOF model for dynamic behaviors of RC members under lateral low-velocity impact. International Journal of Impact Engineering 2023, 173. [CrossRef]

- Clough, R.W. EFFECT OF STIFFNESS DEGRADATION ON EARTHQUAKE DUCTILITY REQUIREMENTS; Effect of stiffness degradation on earthquake ductility requirements: 1966.

- Takeda, T. Reinforced Concrete Response to Simulated Earthquakes. Journal of the Structural Division Proceedings of the American Society of Civil Engineers 1970.

- Ozcebe G; M, S. Hysteretic shear model for reinforced concrete members. Journal of Structural Engineering 1989, 115, 132-148.

- Park Y J; S, A.H. Mechanistic seismic damage model for reinforced concrete. Journal of Structural Engineering 1985, 111, 722-739.

- Wen, Y.K. Method for Random Vibration of Hysteretic Systems. Journal of the Engineering Mechanics Division 1976, 102, 249-263.

- Riddell, R. Statistical analysis of the response of nonlinear systems subjected to earthquakes; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: 1979.

- Takayanagi, T.; Schnobrich, W.C. Non-linear analysis of coupled wall systems. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2010, 7.

- Zhu, B.; Zhang, K. Study on Restoring force characteristics of rectangular and annular section flexural members. Journal of Tongji University 1981, 4-13.

- Saatcioglu, M.; Alsiwat, J.M.; Ozcebe, G. Hysteretic Behavior of Anchorage Slip in R/C Members. Journal of Structural Engineering 1992, 118, 2439-2458. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.Y. Modeling Axial-Shear-Flexure Interaction of RC Columns for Seismic Response Assessment of Bridges. University of California, Los Angeles., 2010.

- Qu, Z.; Ye, L. STRENGTH DETERIORATION MODEL BASED ON EFFECTIVEHYSTERETIC ENERGY DISSIPATION FOR RCMEMBERS UNDER CYCLIC LOADING. ENGINEERING MECHANICS 2011, 28, 45-051.

- D'Ambrisi, A.; Filippou, F.C. Modeling of cyclic shear behavior in RC members. Journal of Structural Engineering 1999, 125, 1143-1150. [CrossRef]

- Gu, x.; Huang, Q.; Wu, Z. Analysis of load-displacement relationship for RC columns under reversed load considering accumulative damage. Earthquake Engineering and Engineering Vibration 2006, 24, 7.

- Zheng, H.; Zheng, S.; He, J.; Zhang, Y., ;; Shang, Z., ;. Research on restoring force model of reinforced concreterectangular beams considering reinforcement corrosion. ournal of Central South University (Science and Technology) 2020, 51, 10.

- Zheng, S.; Rong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, L. Restoring force model of freeze-thaw injury reinforced concrete shear walls. Huazhong Univ.of Sci.& Tech.(Natural Science Edition) 2019, 47, 6.

- Erberik, M.A. Importance of Degrading Behavior for Seismic Performance Evaluation of Simple Structural Systems. Journal of Earthquake Engineering 2011, 15, 32-49. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zheng, S.; Guo, X.; Li, L. Study on restoring force model of SRHSHPC frame columns considering damage effects. Journal of Building Structures 2012, 33, 69-76.

- Roufaiel, M.; Meyer, C. Analytical Modeling of Hysteretic Behavior of R/C Frames. Journal of Structural Engineering 1987, 113, 429-444. [CrossRef]

- Dowell, R.K.; Seible, F.; Wilson, E.L. Pivot Hysteresis Model for Reinforced Concrete Members. Aci Structural Journal.

- Miramontes, D.; Merabet, O.; Reynouard, J.M. Kinematic single surface global model for the seismic analysis of RC frames. 1997.

- Pincheira, J.A.; Dotiwala, F.S.; D"Souza, J.T. Seismic Analysis of Older Reinforced Concrete Columns. Earthquake Spectra 1999, 15, 245-272. [CrossRef]

- Mostaghel, N.; Byrd, R.A. Analytical Description of Multidegree Bilinear Hysteretic System. Journal of Engineering Mechanics 2000, 126, 588-598. [CrossRef]

- Kunnath, S.K.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Park, Y.J. Analytical Modeling of Inelastic Seismic Response of R/C Structures. Journal of Struct Engry 1990, 116, 996-1017. [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Yang, D.; Ma, Z.J.; Jia, J. Hysteretic model of SRUHSC column and SRC beam joints considering damage effects. Materials and Structures 2017, 50, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.H.; Ou, Y.C.; Chang, K.C. A new smooth hysteretic model for ductile flexural-dominated reinforced concrete bridge columns. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2017. [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Ning, C.L.; Li, B. Hysteretic Model for Shear-Critical Reinforced Concrete Columns. Journal of Structural Engineering 2016, 142, 04016056.04016051-04016056.04016013. [CrossRef]

- Sezen, H.; Chowdhury, T. Hysteretic Model for Reinforced Concrete Columns Including the Effect of Shear and Axial Load Failure. Journal of Structural Engineering-Asce 2009, 135, 139-146. [CrossRef]

- Leborgne, M.R.; Ghannoum, W.M. Calibrated analytical element for lateral-strength degradation of reinforced concrete columns. Engineering Structures 2014, 81, 35-48. [CrossRef]

- Chao, S.H.; Loh, C.H. A biaxial hysteretic model for a structural system incorporating strength deterioration and pinching phenomena. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics 2009, 44, 745-756. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Yang, Y. State-of-the-art of restoring force models for RC structures. WORLD EARTHQUAKE ENGINEERING 2004, 20, 47-51.

- Yu, J.; Li, Y.; Xia, H. Hysteretic shear model for RC columns with construction joint. Jianzhu Jiegou Xuebao/Journal of Building Structures 2011, 32, 84-91.

- Cai, M.; Gu, X.; Hua, J.; Lin, F. Seismic response analysis of reinforced concrete columns considering shear effects. Jianzhu Jiegou Xuebao/Journal of Building Structures 2011, 32, 97-108.

- Zhao, J.; Dun, H. A restoring force model for steel fiber reinforced concrete shear walls. Engineering Structures 2014, 75, 469–476. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Li, Y.; Gu, Q.; Liu, J. Machine learning–based hysteretic lateral force-displacement models of reinforced concrete columns. Journal of Structural Engineering 2022, 148, 04021291. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Pincheira, J. Spectral Displacement Demands of Stiffness and Strength-Degrading Systems. Earthquake Spectra 2000, 16, 817-851. [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, L.F.; Medina, R.A.; Krawinkler, H. Hysteretic models that incorporate strength and stiffness deterioration. Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics 2010, 34, 1489-1511. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Long, M. Parameter Identification and Application of Reinforced Concrete Column Based on Modified Ibarra-Medina-Krawinkler Hysteretic Model. Journal of Hunan University(Natural Sciences) 2021.

- Galal, E.M.; Ghobarah, A. Flexural and shear hysteretic behaviour of reinforced concrete columns with variable axial load. Engineering Structures 2003, 25, 1353-1367.

- Zhang, Y.; Han, S. Hysteretic Model for Flexure-shear Critical Reinforced Concrete Columns. Journal of Earthquake Engineering 2018, 22, 1639-1661. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, H.N.; Wang, Z. Study on Strain Rate Effect in High-Rise Reinforced Concrete Shear Wall Structure. Advanced Materials Research 2011, 243-249, 5854-5857. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Xu, D. Influence of strain rate effect on reinforced concrete column. Journal of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Engineering 2009, 29, 668-675.

- Wang, C.Q.; Xiao, J.Z.; Sun, Z.P. Seismic analysis on recycled aggregate concrete frame considering strain rate effect. International Journal of Concrete Structures and Materials 2016, 10, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Pankaj, P.; Lin, E. Material modelling in the seismic response analysis for the design of RC framed structures. Engineering Structures 2005, 27, 1014-1023. [CrossRef]

- Iribarren, B.S.; Berke, P.; Bouillard, P.; Vantomme, J.; Massart, T.J. Investigation of the influence of design and material parameters in the progressive collapse analysis of RC structures. Engineering Structures 2011, 33, 2805-2820. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, H.N. Dynamic analysis of reinforced concrete structure with strain rate effect. Material Research Innovations 2011, 15, s213-s216. [CrossRef]

- Asprone, D.; Frascadore, R.; Ludovico, M.D.; Prota, A.; Manfredi, G. Influence of strain rate on the seismic response of RC structures. Engineering Structures 2012, 35, 29-36. [CrossRef]

| No. | Reference | Type | Number | Loading rate | Loading scheme |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bertero et al[32] | Beam | 6 | 0.1、10/s | Mono, cycl |

| 2 | Shah et al [33] | Joint | 3 | 2.5×10-3-1.0Hz | Cycl |

| 3 | ChungBREAKand Shah[20] | Joint | 12 | 0.0025-2.0Hz | Cycl |

| 4 | KulkarniBREAKand Shah[34] | Beam | 14 | 0.0071-380mm/s | Mono |

| 5 | Gutierrez et al[35] | Column | 3 | 0.02-1Hz | Cycl |

| 6 | Orozco[36] | Column | 3 | 0.22-1m/s | Cycl |

| 7 | Bousias et al[37] | Column | 12 | / | Cycl, Biax |

| 8 | Gibson et al[38] | Joint | 4 | 0-405mm/s | Cycl |

| 9 | White et al[39] | Beam | 4 | 0.0167-36mm/s | Mono, Cycl |

| 10 | Li et al[40] | Column | 30 | 0.000011-0.0167/s | Mono |

| 11 | Zhang et al[41] | Beam | 36 | 1.05×10-5、1.25×10-3/s | Mono |

| 12 | Fukuda et al[42] | Beam | 48 | 4×10-4-2m/s | Mono |

| 13 | Witarto et al[5] | Column | 4 | 0.05-5Hz | Cycl |

| 14 | Adhikary et alBREAK[7,9,14] | Beam | 24 | 4×10-4-2m/s | Mono |

| 15 | Adhikary et al[43] | Beam | 30 | 0-5.6m/s | Mono |

| 16 | Perry et al[44] | Column | 4 | 0.7×10-4-0.7×10-3/s | Mono, Cycl |

| 17 | Marder et al[12] | Beam | 17 | 100Hz | Mono, Cycl |

| 18 | Yan[45] | Beam | / | 1×10-5-1×10-3/s | Cycl |

| 19 | Yan[45] | Column | / | 10-5-10-2/s | Mono |

| 20 | Xiao et al[46] | Beam | 5 | 0.1-10mm/s | Mono |

| 21 | Pan[23] | Joint | 10 | 0.1-10mm/s | Cycl |

| 22 | Zou et al[47] | Column | / | 10-5-10-2/s | Mono |

| 23 | Fan et al[22] | Joint | 3 | 0.4-40mm/s | Cycl |

| 24 | Wang et al[21] | Joint | 8 | 0.4-40mm/s | Cycl |

| 25 | Zhang[16] | Shear wall | 7 | 10-5-10-3/s | Cycl |

| 26 | Yuan and Yi[48] | 18 | 3.5×10-4--1m/s | Mono | |

| 27 | Li and Li[10] | Beam | 16 | 0.05-30mm/s | Mono, Cycl |

| 28 | Wang et al[49] | Column | 30 | 0.1-50mm/s | Mono, Cycl, Biax |

| 29 | Jiang[50] | Column | 12 | 0.1-20mm/s | Mono, Cycl, Biax |

| 30 | Zeng[51] | Beam | 6 | 10-2/s-8.85m/s | Mono |

| 31 | Xu et al[15] | Shear wall | 2 | 1-10mm/s | Cycl |

| 32 | Song et al[4] | Beam | 5 | 3.5-6 m/s | Mono |

| 33 | Ye et al[52] | Beam | 14 | 0.8m/s | Mono |

| 34 | Zhou et al[53] | Beam | 7 | 0.06mm -66mm /s | Mono |

| 35 | Xiang et al[54] | Beam | 7 | / | Mono |

| 36 | Feng et al[55] | Beam | 10 | 3-7.7m/s | Mono |

| 37 | MutsuyoushiBREAKand Machida[56] | Beam | 14 | 0.1、10、100cm/s | Mono, Cycl |

| 38 | Otani et al[57] | Beam | 8 | 0.1、100mm/s | Cycl |

| 39 | Fujikake[13] | Beam | 6 | 5×10-4m/s、2m/s | Mono |

| 40 | Ghannoum et al[30] | Column | 10 | 0.25mm/s-1061mm/s | Cycl |

| Model | Range of dynamic strain rate | quasi-static strain rate | Type of formula | Modified parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEB Model [26] | Exponential | |||

| Malvar model [103] | Exponential | |||

| Tedesco and Ross Model [104] | Linear logarithmic | |||

| Yan Model [69] | Linear logarithmic | |||

| Xiao and Zhang Model [105] | Linear logarithmic | |||

| Li Model [28] | Linear logarithmic |

| Model | Range of dynamic BREAKstrain rate | quasi-static BREAKstrain rate | Type of formula | Modified parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEB Model [26] | Linear logarithmic | |||

| Malvar model [103] | Exponential | |||

| Lin Feng Model [27] | Linear logarithmic | |||

| Li and Li Model [83] | Linear logarithmic |

| Reference | Equations of dynamic modified model | Model type |

|---|---|---|

| Adhikary et al. [7] |

Maximum resistance of RC regular beams BREAKWith transverse reinforcementsBREAKBREAKWithout transverse reinforcementsBREAK | FE simulation results-basedBREAK(Deterministic) |

| Adhikary et al. [14] |

Maximum resistance of RC deep beams BREAKRC beams without transverse reinforcementsBREAK | FE simulation results-basedBREAK(Deterministic) |

| Wang [58] | Ultimate bearing capacity of RC columns BREAKDifferent axial load ratioBREAK | FE simulation results-basedBREAK(Deterministic) |

| Different concrete strength conditionsBREAK | ||

| Different longitudinal reinforcement ratiosBREAK | ||

| Li et al. [111] | Mechanical behavior parameters of RC columns (including yielding and ultimate bearing capacity, effective stiffness and ductility coefficient) |

Experimental date-basedBREAK(Probabilistic) |

| FanBREAK[112] | Shear bearing capacity of RC joints |

Experimental date-basedBREAK(Deterministic) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).