Submitted:

13 April 2023

Posted:

14 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

3. Results

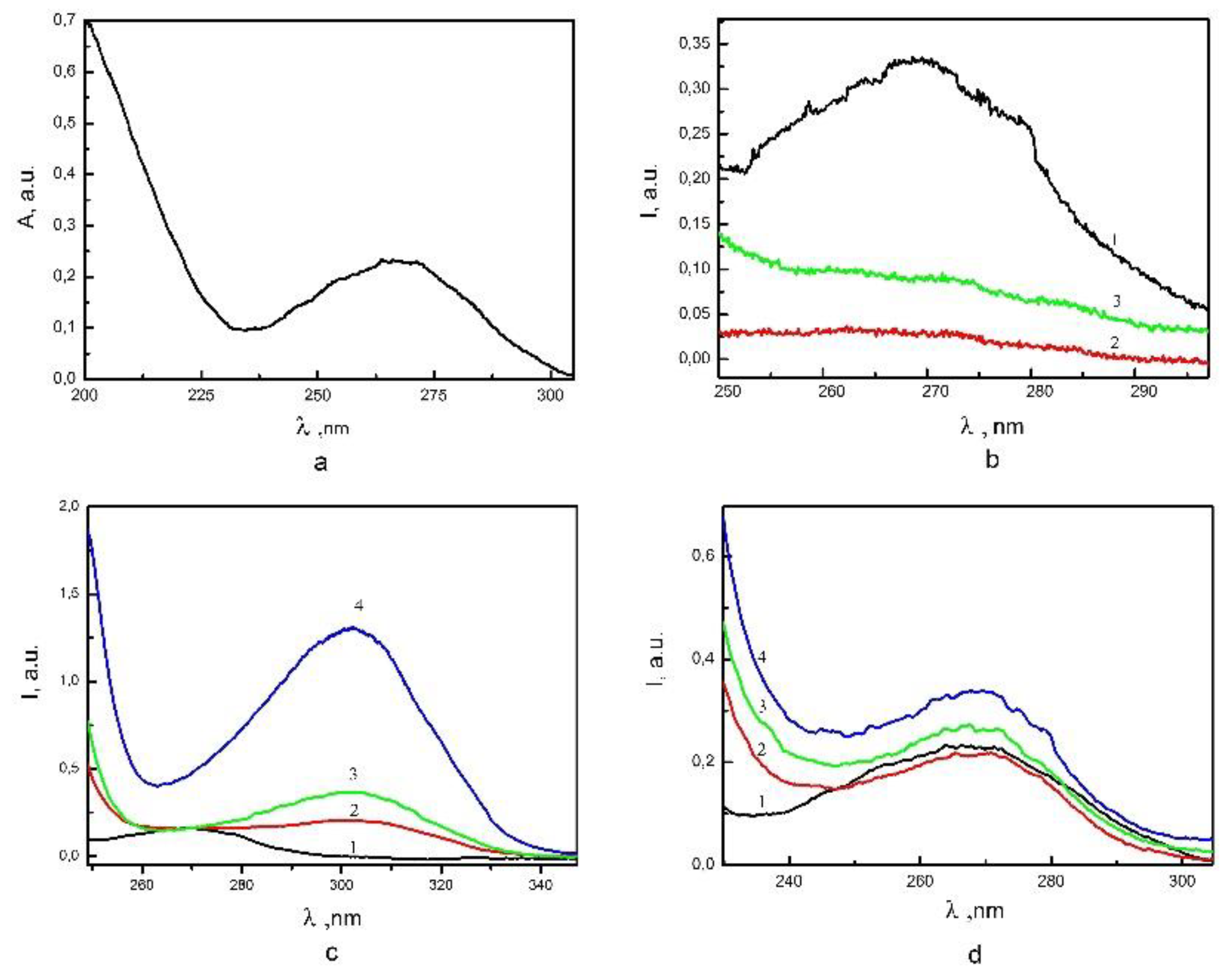

3.1. The effect of electrolytes and surfactants on the interaction of nanoparticles based on Zirconia with nucleotides.

3.2. The effect of electrolytes and surfactants to the nanopowder particles with DNA nucleotides interaction.

3.3. Interaction with HNO3

3.4. Interaction with KOH

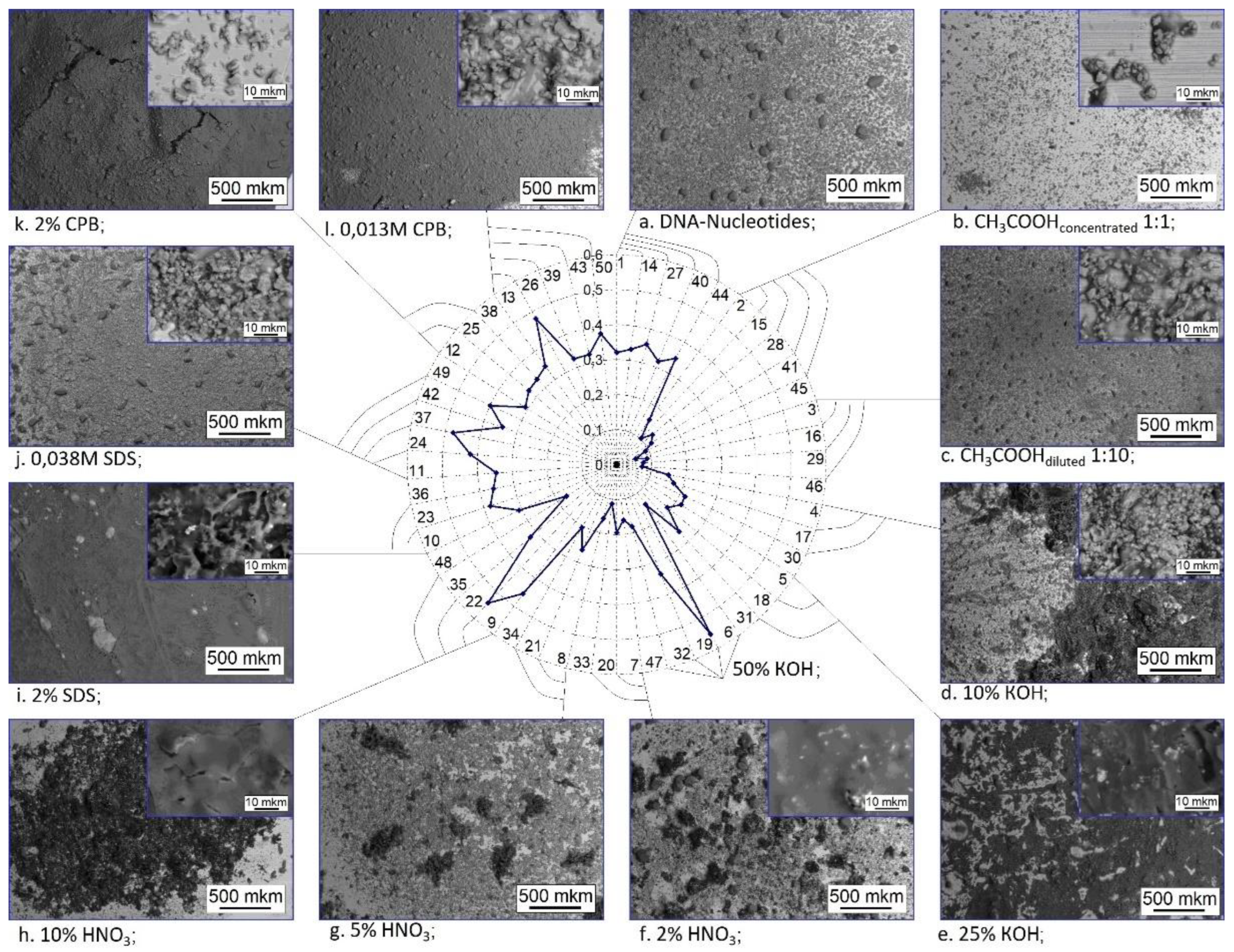

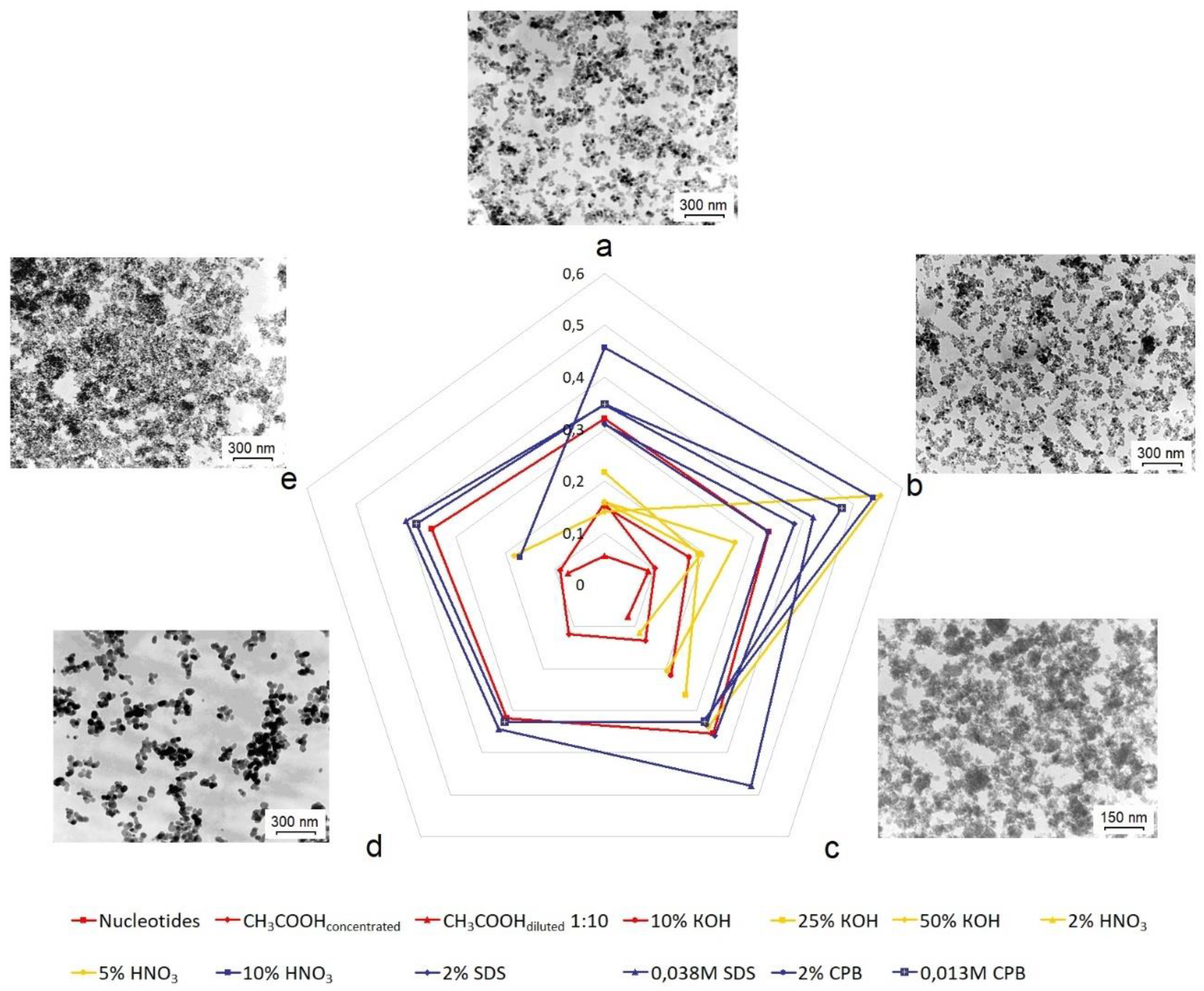

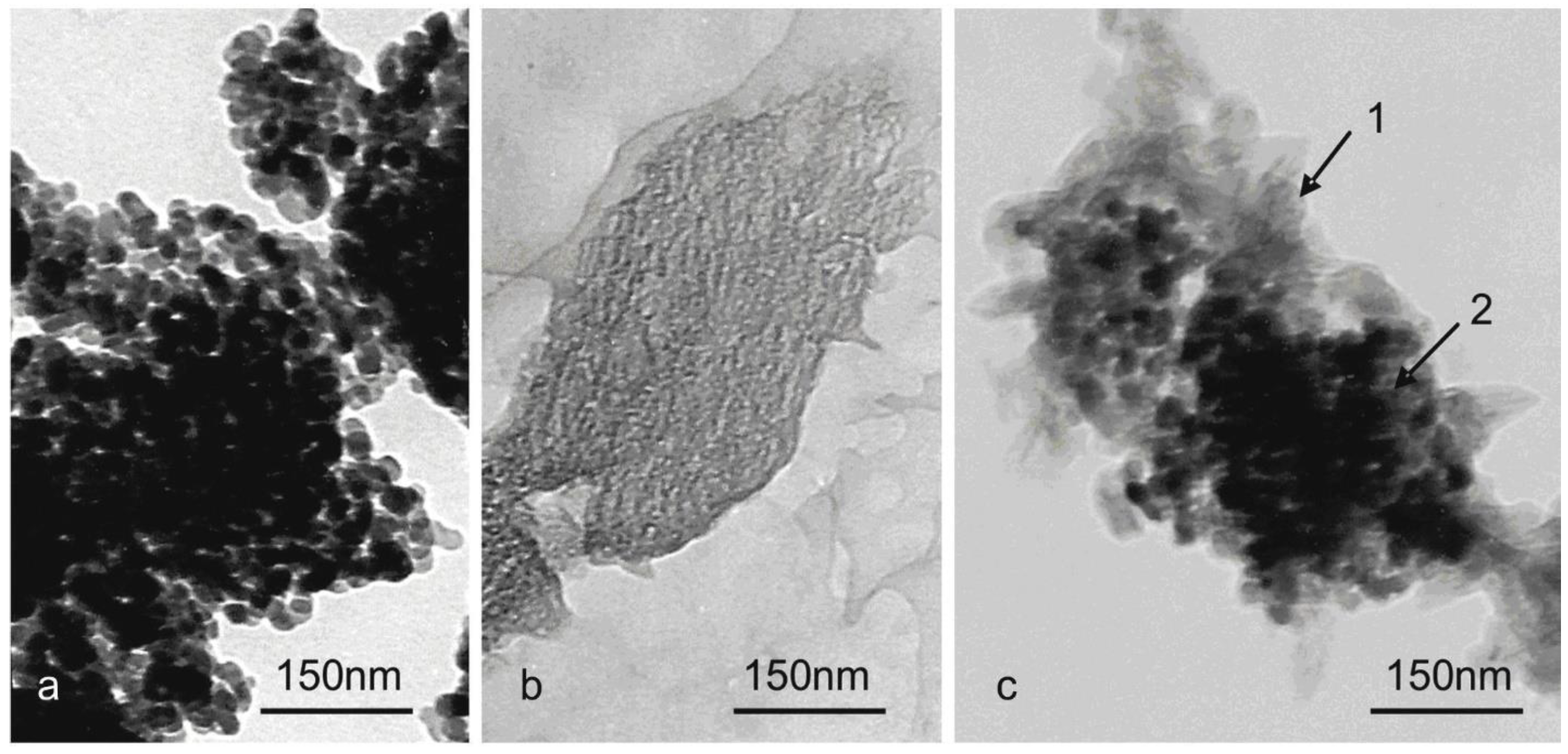

3.5. Objects morphology

3.6. The influence of the chemical composition of the material of nanoparticles on the adsorption of nucleotides

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix 1

| № | Sample content |

| 1 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 1ml DNA |

| 2 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 1ml 1/1 sol. C2H5OH:CH3COOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 3 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 1/10 sol. C2H5OH:CH3COOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 4 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 10% КOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 5 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 25% КOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 6 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 50% КOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 7 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 2% HNO3 + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 8 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 5% HNO3 + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 9 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 10% HNO3 + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 10 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 2% SDS + 1 ml DNA |

| 11 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 3,84∙10-2 M sol. lauryl sulfate + 1 ml DNA |

| 12 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 2% CPB + 1 ml DNA |

| 13 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 1,3∙10-2 М sol. CPB + 1 ml DNA |

| 14 | ZrO2 – 8%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 1 ml DNA |

| 15 | ZrO2 – 8%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 1 ml 1/1 sol. C2H5OH:CH3COOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 16 | ZrO2 – 8%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 1/10 sol. C2H5OH:CH3COOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 17 | ZrO2 – 8%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 10% КOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 18 | ZrO2 – 8%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 25% КOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 19 | ZrO2 – 8%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 50% КOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 20 | ZrO2 – 8%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 2% HNO3 + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 21 | ZrO2 – 8%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 5% HNO3 + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 22 | ZrO2 – 8%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 10% HNO3 + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 23 | ZrO2 – 8%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 2% lauryl sulfate + 1 ml DNA |

| 24 | ZrO2 – 8%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 3,84∙10-2 М sol. lauryl sulfate + 1 ml DNA |

| 25 | ZrO2 – 8%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 2% CPB + 1 ml DNA |

| 26 | ZrO2 – 8%mol Y2O3 (700°С, 2h) + 1,3∙10-2 М sol. CPB + 1 ml DNA |

| 27 | Zirconium hydroxide with the addition of 3% mol of Yttrium hydroxide (120°С, 2h) + 1 ml DNA |

| 28 | 3YSZ hydroxide (120°С, 2h) + ml 1/1 sol. C2H5OH:CH3COOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 29 | 3YSZ hydroxide (120°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 1/10 sol. C2H5OH:CH3COOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 30 | 3YSZ hydroxide (120°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 10% КOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 31 | 3YSZ hydroxide (120°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 25% КOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 32 | 3YSZ hydroxide (120°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 50% КOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 33 | 3YSZ hydroxide (120°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 2% HNO3 + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 34 | 3YSZ hydroxide (120°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 5% HNO3 + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 35 | 3YSZ hydroxide (120°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 10% HNO3 + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 36 | 3YSZ hydroxide (120°С, 2h) + 2% SDS + 1 ml DNA |

| 37 | 3YSZ hydroxide (120°С, 2h) + 3,84∙10-2 М р- SDS + 1 ml DNA |

| 38 | 3YSZ hydroxide (120°С, 2h) + 2% CPB + 1 ml DNA |

| 39 | 3YSZ hydroxide (120°С, 2h) + 1,3∙10-2 М sol. CPB + 1 ml DNA |

| 40 | ZrO2 (700°С, 2h) + 1 ml DNA |

| 41 | ZrO2 (700°С, 2h) + 1 ml 1/1 sol. C2H5OH:CH3COOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 42 | ZrO2 (700°С, 2h) + 3,84∙10-2 М s SDS + 1 ml DNA |

| 43 | ZrO2 (700°С, 2h) + 1,3∙10-2 М sol. CPB + 1 ml DNA |

| 44 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (400°С, 2h) + 1 ml DNA |

| 45 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (400°С, 2h) + 1 ml 1/1 sol. C2H5OH:CH3COOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 46 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (400°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 1/10 sol. C2H5OH:CH3COOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 47 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (400°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 10% КOH + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 48 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (400°С, 2h) + 0,5 ml 5% HNO3 + 0,5 ml DNA |

| 49 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (400°С, 2h) + 3,84∙10-2 М sol. SDS + 1 ml DNA |

| 50 | ZrO2 – 3%mol Y2O3 (400°С, 2h) + 1,3∙10-2 М sol. CPB + 1 ml DNA |

References

- Tarantina, O. A New Age Is Coming – the Age of Nanobioelectronics Available online:. Available online: http://www.dubnapress.ru/knowledge/286-2010-11-19-08-20-13 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Gray, H.B.; Winkler, J.R. Electron Transfer in Proteins. Annu Rev Biochem 1996, 65, 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xiang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Beratan, D.N.; Li, Y.; Tao, N. Engineering Nanometre-Scale Coherence in Soft Matter. Nat Chem 2016, 8, 941–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechlaner, M.; Sigel, R.K.O. Characterization of Metal Ion-Nucleic Acid Interactions in Solution. Met Ions Life Sci 2012, 10, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigel, R.K.O.; Sigel, H. A Stability Concept for Metal Ion Coordination to Single-Stranded Nucleic Acids and Affinities of Individual Sites. Acc Chem Res 2010, 43, 974–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, V.K.; Shiman, R.; Draper, D.E. A Thermodynamic Framework for the Magnesium-Dependent Folding of RNA. Biopolymers 2003, 69, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masillamani, A.M.; Osella, S.; Liscio, A.; Fenwick, O.; Reinders, F.; Mayor, M.; Palermo, V.; Cornil, J.; Samorì, P. Light-Induced Reversible Modification of the Work Function of a New Perfluorinated Biphenyl Azobenzene Chemisorbed on Au (111). Nanoscale 2014, 6, 8969–8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müri, M.; Gotsmann, B.; Leroux, Y.; Trouwborst, M.; Lörtscher, E.; Riel, H.; Mayor, M. Modular Functionalization of Electrodes by Cross-Coupling Reactions at Their Surfaces. Adv Funct Mater 2011, 21, 3706–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivillers, N.; Osella, S.; Van Dyck, C.; Lazzerini, G.M.; Cornil, D.; Liscio, A.; Di Stasio, F.; Mian, S.; Fenwick, O.; Reinders, F.; et al. Large Work Function Shift of Gold Induced by a Novel Perfluorinated Azobenzene-Based Self-Assembled Monolayer. Adv Mater 2013, 25, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knorre, D.G.; Myzina, S.D. Biological Chemistry; High School: Moscow, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sebechlebská, T.; Šebera, J.; Kolivoška, V.; Lindner, M.; Gasior, J.; Mészáros, G.; Valášek, M.; Mayor, M.; Hromadová, M. Investigation of the Geometrical Arrangement and Single Molecule Charge Transport in Self-Assembled Monolayers of Molecular Towers Based on Tetraphenylmethane Tripod. Electrochim Acta 2017, 258, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishchenko, A.; Zotti, L.A.; Vonlanthen, D.; Bürkle, M.; Pauly, F.; Cuevas, J.C.; Mayor, M.; Wandlowski, T. Single-Molecule Junctions Based on Nitrile-Terminated Biphenyls: A Promising New Anchoring Group. J Am Chem Soc 2011, 133, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strukov, D.B.; Snider, G.S.; Stewart, D.R.; Williams, R.S. The Missing Memristor Found. Nature 2008, 453, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, H.J. Low Voltage Electrolytic Capacitor 1954.

- Rightmire, R.A. Electrical Energy Storage Apparatus U. S. Patent 3288641 1962.

- Maxwell, J.C. 1873.

- Damaskin, B.B.; Petri, O.A. Introduction to Electrochemical Kinetics; Higher School: Moscow, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Majumder, S.; Mishra, I.; Subudhi, U.; Varma, S. Enhanced Biocompatibility for Plasmid DNA on Patterned TiO2 Surfaces. Appl Phys Lett 2013, 103, 063103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlenko, M.A.; Nagaytsev, M.V.; Dovbysh, V.M. Additive Technologies in Mechanical Engineering; GNTs RF Federal State Unitary Enterprise: Moscow, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, G.; Thannhauser, S.J. A Method for the Determination of Desoxyribonucleic Acid, Ribonucleic Acid, and Phosphoproteins in Animal Tissues. J Biol Chem 1945, 161, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doroshkevich, A.S.; Danilenko, I.A.; Konstantinova, T.E.; Glazunova, V.A.; Sinyakina, S.A. Diagnostics of Nanopowder Systems Based on Zirconium Dioxide by Methods of Transmission Electron Microscopy. Electron microscopy and strength of materials 2006, 13, 151. [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis, T.I.; Fritsch, E.; Sambrook, J. Molecular Cloning; Mir: Moscow, 1984. [Google Scholar]

| Group Number |

Chemical structure | Sintering temperature / Particle size |

Structural ordering |

pHair-dry | SBET, m2/g |

| 1 | ZrO2+3%molY2O3 | 700°C / 17 nm | Crystalline, P42 / nmc | 5,95 | 42,4 |

| 2 | ZrO2+8%molY2O3 | 700°C / 15 nm | Crystalline, Fm3m | 4,71 | 59,39 |

| 3 | (Zr+3%molY2O2)O(OH)2 | 120°C / 3-4 nm | Middle order | 5,26 | 310 |

| 4 | ZrO2 | 700°C / 18 nm | Crystalline, P21C | 5,79 | 34,7 |

| 5 | ZrO2+3%molY2O3 | 400°C / 7,5-9 nm | Crystalline, P42 / nmc | 4,89 | 113,8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).