Submitted:

21 April 2023

Posted:

23 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1.0. Introduction

1.1. Current Limitation in Diagnosis of Autoimmune Diseases

1.2. Metagenomics and Machine Learning for Microbial Analysis

2.0. Biomarker Discovery with Machine Learning Approaches

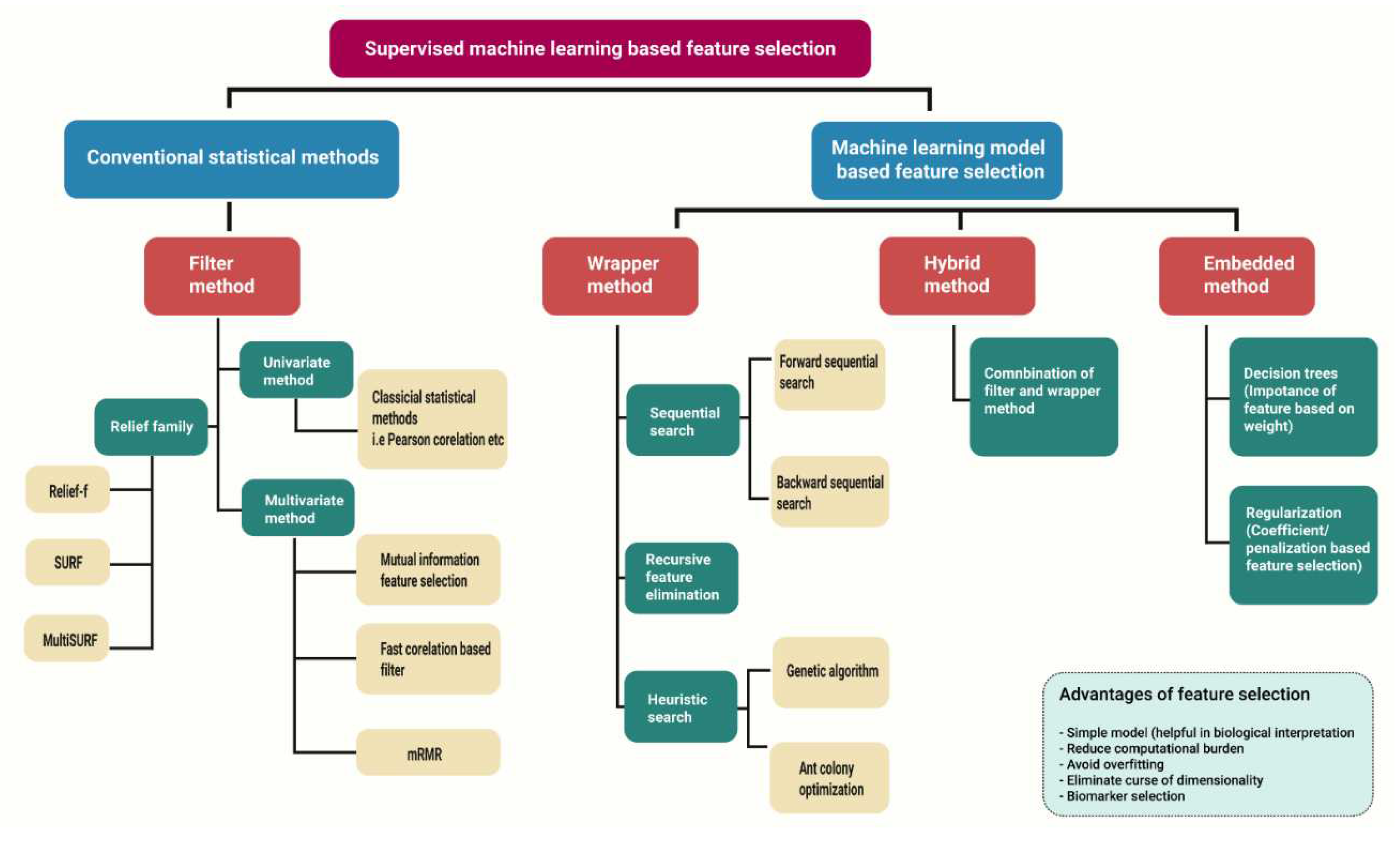

2.1. High-Dimensional Data Analysis Using Machine Learning and Conventional Statistical Methods

2.1.1. Filter Method

2.1.2. Wrapper Method

2.1.3. Embedded Method

2.1.4. Hybrid Search

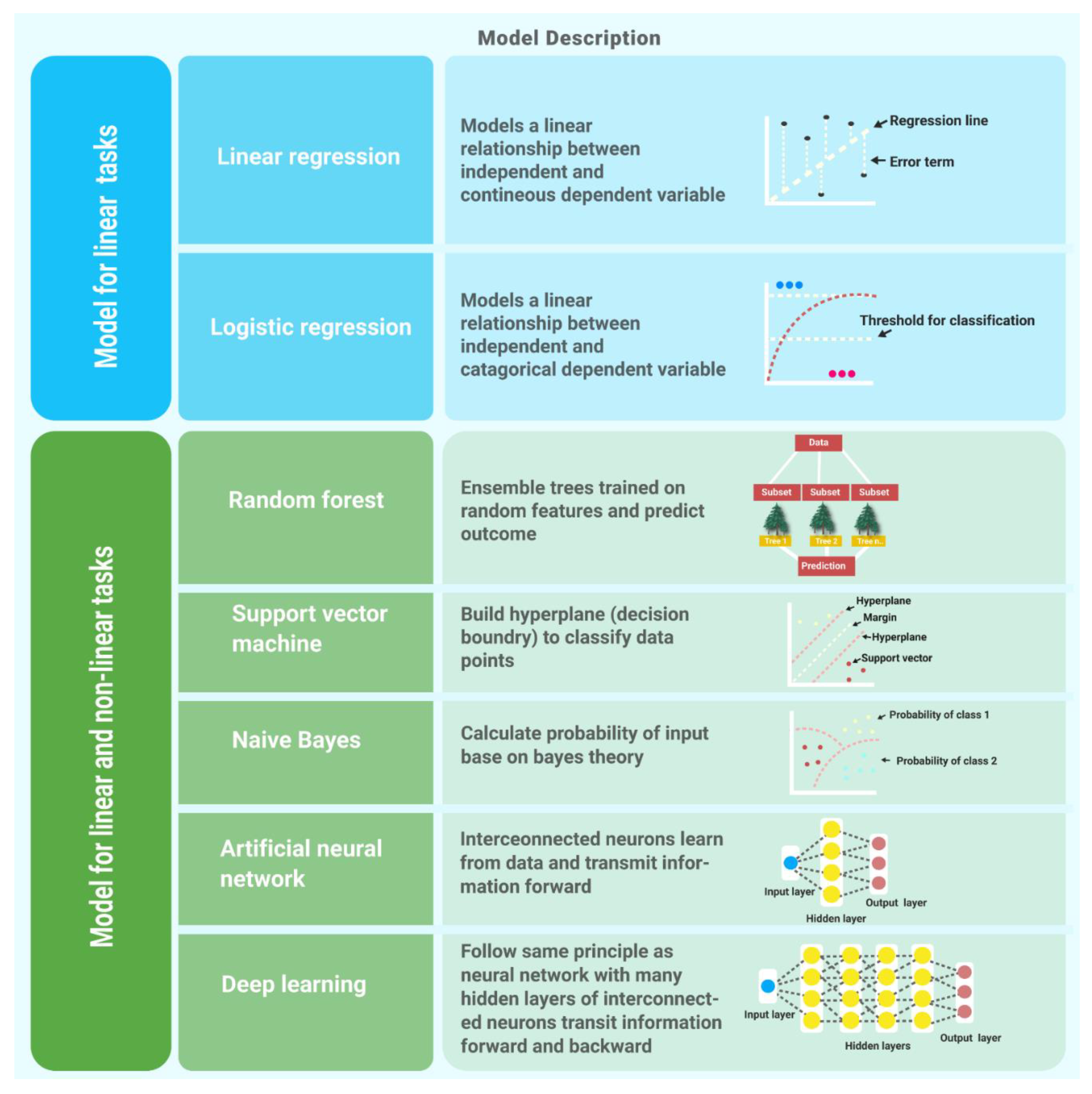

3.0. Supervised Learning Algorithms

3.1. Linear Regression

3.2. Logistic Regression

3.3. Naïve Bayes

3.4. Random Forest

3.5. Support Vector Machine

3.6. Artificial Neural Network

3.7. Deep Learning

4.0. Validation Strategies and Performance Metrics for Machine Learning Models

4.1. Data for Training and Validation of Models

4.2. Performance Estimation of Machine Learning Models

5.0. Application of Machine Learning and Metagenomics in Autoimmune Diseases

5.1. Machine Learning in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBD) Diagnosis

5.2. Machine Learning in Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) Diagnosis

5.3. Machine Learning in Other Autoimmune Diseases Diagnosis

6.0. Challenges and Risks Inherent in Developing ML-Based Diagnosis Models

6.1. Explanation Matters

6.2. Pitfalls to Avoid in Development of Diagnostic Models

6.2.1. Data Collection and Data Representation for Machine Learning Models

6.2.2. Imputations of Missing Values

6.2.3. Feature Selection and Performance Metrics Selection

7.0. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davidson, A.; Diamond, B. Autoimmune diseases. N Engl J Med 2001, 345, 340–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, F. S.; Gershwin, M. E. Human autoimmune diseases: a comprehensive update. J Intern Med 2015, 278, 369–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Sun, L.; Zhang, X. Integration of microbiome and epigenome to decipher the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun 2017, 83, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacilar, H.; Nalbantoglu, O. U.; Bakir-Güngör, B. Machine Learning Analysis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Associated Metagenomics Dataset. 2018 3rd International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK), 2018; pp. 434–438. [Google Scholar]

- Biewenga, M.; Farina Sarasqueta, A.; Tushuizen, M. E.; de Jonge-Muller, E. S. M.; van Hoek, B.; Trouw, L. A. The role of complement activation in autoimmune liver disease. Autoimmun Rev 2020, 19, 102534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Ran, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, B.; Zhou, L. The Microbiome in Autoimmune Liver Diseases: Metagenomic and Metabolomic Changes. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narváez, J. Lupus erythematosus 2020. Medicina Clínica (English Edition) 2020, 155, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuora, S. Rheumatoid arthritis: Methotrexate and bridging glucocorticoids in early RA. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014, 10, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psarras, A.; Emery, P.; Vital, E. M. Type I interferon-mediated autoimmune diseases: pathogenesis, diagnosis and targeted therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017, 56, 1662–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, F.; Abbaszadeh, H.; Mehdizadeh, A.; Ebrahimi-Warkiani, M.; Rashidi, M. R.; Yousefi, M. Biosensors and nanobiosensors for rapid detection of autoimmune diseases: a review. Mikrochim Acta 2019, 186, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, A. J. Diagnosis, Differential Diagnosis, and Misdiagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2019, 25, 611–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, S.; Kahlenberg, J. M. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: New Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Annual Review of Medicine 2023, 74, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuenca, M.; Sintes, J.; Lányi, Á.; Engel, P. CD84 cell surface signaling molecule: An emerging biomarker and target for cancer and autoimmune disorders. Clin Immunol 2019, 204, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rönnblom, L.; Leonard, D. Interferon pathway in SLE: one key to unlocking the mystery of the disease. Lupus Sci Med 2019, 6, e000270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capecchi, R.; Puxeddu, I.; Pratesi, F.; Migliorini, P. New biomarkers in SLE: from bench to bedside. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020, 59 (Suppl5), v12–v18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziemssen, T.; Akgün, K.; Brück, W. Molecular biomarkers in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casimiro-Soriguer, C. S.; Loucera, C.; Peña-Chilet, M.; Dopazo, J. Towards a metagenomics machine learning interpretable model for understanding the transition from adenoma to colorectal cancer. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, Q.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Xie, D.; Ye, T. Artificial intelligence in clinical applications for lung cancer: diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Clin Chem Lab Med 2022, 60, 1974–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sender, R.; Fuchs, S.; Milo, R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol 2016, 14, e1002533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.-T.; Lai, J.-B.; Du, Y.-L.; Xu, Y.; Ruan, L.-M.; Hu, S.-H. Current Understanding of Gut Microbiota in Mood Disorders: An Update of Human Studies. Frontiers in Genetics 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [21] Dey, P.; Ray Chaudhuri, S. The opportunistic nature of gut commensal microbiota. Crit Rev Microbiol 2022, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Streit, W. R.; Schmitz, R. A. Metagenomics--the key to the uncultured microbes. Curr Opin Microbiol 2004, 7, 492–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brumfield, K. D.; Huq, A.; Colwell, R. R.; Olds, J. L.; Leddy, M. B. Microbial resolution of whole genome shotgun and 16S amplicon metagenomic sequencing using publicly available NEON data. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0228899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbaugh, P. J.; Ley, R. E.; Hamady, M.; Fraser-Liggett, C. M.; Knight, R.; Gordon, J. I. The human microbiome project. Nature 2007, 449, 804–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, D.; Hyde, E.; Debelius, J. W.; Morton, J. T.; Gonzalez, A.; Ackermann, G.; Aksenov, A. A.; Behsaz, B.; Brennan, C.; Chen, Y.; DeRight Goldasich, L.; Dorrestein, P. C.; Dunn, R. R.; Fahimipour, A. K.; Gaffney, J.; Gilbert, J. A.; Gogul, G.; Green, J. L.; Hugenholtz, P.; Humphrey, G.; Huttenhower, C.; Jackson, M. A.; Janssen, S.; Jeste, D. V.; Jiang, L.; Kelley, S. T.; Knights, D.; Kosciolek, T.; Ladau, J.; Leach, J.; Marotz, C.; Meleshko, D.; Melnik, A. V.; Metcalf, J. L.; Mohimani, H.; Montassier, E.; Navas-Molina, J.; Nguyen, T. T.; Peddada, S.; Pevzner, P.; Pollard, K. S.; Rahnavard, G.; Robbins-Pianka, A.; Sangwan, N.; Shorenstein, J.; Smarr, L.; Song, S. J.; Spector, T.; Swafford, A. D.; Thackray, V. G.; Thompson, L. R.; Tripathi, A.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Vrbanac, A.; Wischmeyer, P.; Wolfe, E.; Zhu, Q.; Knight, R. American Gut: an Open Platform for Citizen Science Microbiome Research. mSystems 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J.; Arumugam, M.; Burgdorf, K. S.; Manichanh, C.; Nielsen, T.; Pons, N.; Levenez, F.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D. R.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; Li, S.; Li, D.; Cao, J.; Wang, B.; Liang, H.; Zheng, H.; Xie, Y.; Tap, J.; Lepage, P.; Bertalan, M.; Batto, J. M.; Hansen, T.; Le Paslier, D.; Linneberg, A.; Nielsen, H. B.; Pelletier, E.; Renault, P.; Sicheritz-Ponten, T.; Turner, K.; Zhu, H.; Yu, C.; Li, S.; Jian, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Qin, N.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Brunak, S.; Doré, J.; Guarner, F.; Kristiansen, K.; Pedersen, O.; Parkhill, J.; Weissenbach, J.; Bork, P.; Ehrlich, S. D.; Wang, J. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 2010, 464, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugli, GA.; Ventura, M. A breath of fresh air in microbiome science: shallow shotgun metagenomics for a reliable disentangling of microbial ecosystems. Microbiome. Res. Rep. 2022, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokulich, N. A.; Ziemski, M.; Robeson, M. S., 2nd; Kaehler, B. D. Measuring the microbiome: Best practices for developing and benchmarking microbiomics methods. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2020, 18, 4048–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, E.; Khoso, S.; Sica, A.; Falasca, M.; Gennari, A.; Dondero, F.; Afantitis, A.; Manfredi, M. Precision Medicine Approaches with Metabolomics and Artificial Intelligence. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y. W.; Jo, H.-S.; Bae, S.; Seo, Y.; Song, P.; Song, M.; Yoon, J. H. Application of Proteomics in Cancer: Recent Trends and Approaches for Biomarkers Discovery. Frontiers in Medicine 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, E.; Amede, E.; Khoso, S.; Castello, L.; Sainaghi, P. P.; Bellan, M.; Balbo, P. E.; Patti, G.; Brustia, D.; Giordano, M.; Rolla, R.; Chiocchetti, A.; Romani, G.; Manfredi, M.; Vaschetto, R. Metabolomics Diagnosis of COVID-19 from Exhaled Breath Condensate Metabolites [Online], 2021.

- Avanzo, M.; Stancanello, J.; Pirrone, G.; Sartor, G. Radiomics and deep learning in lung cancer. Strahlenther Onkol 2020, 196, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mreyoud, Y.; Song, M.; Lim, J.; Ahn, T.-H. MegaD: Deep Learning for Rapid and Accurate Disease Status Prediction of Metagenomic Samples Life [Online], 2022.

- Jia, W.; Sun, M.; Lian, J.; Hou, S. Feature dimensionality reduction: a review. Complex & Intelligent Systems 2022, 8, 2663–2693. [Google Scholar]

- Cantini, L.; Zakeri, P.; Hernandez, C.; Naldi, A.; Thieffry, D.; Remy, E.; Baudot, A. Benchmarking joint multi-omics dimensionality reduction approaches for the study of cancer. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solorio-Fernández, S.; Carrasco-Ochoa, J. A.; Martínez-Trinidad, J. F. A review of unsupervised feature selection methods. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 53, 907–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopf, K.; Reifenrath, S. Filter Methods for Feature Selection in Supervised Machine Learning Applications - Review and Benchmark. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.12140. [Google Scholar]

- Rajab, M.; Wang, D. Practical Challenges and Recommendations of Filter Methods for Feature Selection. Journal of Information & Knowledge Management 2020, 19, 2040019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, S.; Jiang, S. A feature selection method via analysis of relevance, redundancy, and interaction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 183 (C), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, M. A.; Sherly, K. K. In A Novel Forward Filter Feature Selection Algorithm Based on Maximum Dual Interaction and Maximum Feature Relevance(MDIMFR) for Machine Learning. 2021 International Conference on Advances in Computing and Communications (ICACC), 21-23 Oct. 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanowicz, R. J.; Meeker, M.; La Cava, W.; Olson, R. S.; Moore, J. H. Relief-based feature selection: Introduction and review. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2018, 85, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Honavar, V. G. Feature Subset Selection Using a Genetic Algorithm. IEEE Intelligent Systems 1998, 13, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsati, R.; Moayedikia, A.; Jensen, R.; Shamsfard, M.; Meybodi, M. R. Enriched ant colony optimization and its application in feature selection. Neurocomputing 2014, 142, 354–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Fang, X.; Zhao, J. Biomarker identification by feature wrappers. Genome Res 2001, 11, 1878–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, G.; Sahin, F. A survey on feature selection methods. Computers & Electrical Engineering 2014, 40, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, M.; Liu, Q. An Embedded Feature Selection Method for Imbalanced Data Classification. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2019, 6, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okser, S.; Pahikkala, T.; Airola, A.; Salakoski, T.; Ripatti, S.; Aittokallio, T. Regularized machine learning in the genetic prediction of complex traits. PLoS Genet 2014, 10, e1004754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, I.-S.; Lee, J.-S.; Moon, B.-R. Hybrid Genetic Algorithms for Feature Selection. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2004, 26, 1424–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cadenas, J.; Garrido, M.; Martínez-España, R. Feature subset selection Filter–Wrapper based on low quality data. Expert Systems with Applications 2013, 40, 6241–6252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Shahzad, W. A FEATURE SUBSET SELECTION METHOD BASED ON CONDITIONAL MUTUAL INFORMATION AND ANT COLONY OPTIMIZATION. International Journal of Computer Applications 2012.

- Stanton, J. M. Galton, Pearson, and the Peas: A Brief History of Linear Regression for Statistics Instructors. Journal of Statistics Education 2001, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.; Hommel, G.; Blettner, M. Linear regression analysis: part 14 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010, 107, 776–82. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, C.; Ramirez, L.; Liuzzi, J. Big Data Analysis Using Modern Statistical and Machine Learning Methods in Medicine. International neurourology journal 2014, 18, 50–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhat, A.; Khullar, V. Sentiment classification on big data using Naïve bayes and logistic regression. 2017 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI), 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayarani, D. S.; Dhayanand, M. S. In Liver Disease Prediction using SVM and Naïve Bayes Algorithms, 2015.

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M. Reducing correlation of random forest–based learning-to-rank algorithms using subsample size. Computational Intelligence 2019, 35, 774–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touw, W. G.; Bayjanov, J. R.; Overmars, L.; Backus, L.; Boekhorst, J.; Wels, M.; van Hijum, S. A. F. T. Data mining in the Life Sciences with Random Forest: a walk in the park or lost in the jungle? Briefings in Bioinformatics 2013, 14, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Machine Learning 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristianini, N.; Shawe-Taylor, J. An Introduction to Support Vector Machines and Other Kernel-based Learning Methods; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Cai, N.; Pacheco, P. P.; Narrandes, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, W. Applications of Support Vector Machine (SVM) Learning in Cancer Genomics. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 2018, 15, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Debik, J.; Sangermani, M.; Wang, F.; Madssen, T. S.; Giskeødegård, G. F. Multivariate analysis of NMR-based metabolomic data. NMR Biomed 2022, 35, e4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrej, K.; Janez, B. t.; Andrej, K. Introduction to the Artificial Neural Networks. In Artificial Neural Networks; Kenji, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2011; p. Ch. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Parhi, R.; Nowak, R. The Role of Neural Network Activation Functions. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2020, 27, 1779–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. In Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 27-30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, D.; Huang, A.; Maddison, C. J.; Guez, A.; Sifre, L.; van den Driessche, G.; Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Panneershelvam, V.; Lanctot, M.; Dieleman, S.; Grewe, D.; Nham, J.; Kalchbrenner, N.; Sutskever, I.; Lillicrap, T.; Leach, M.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Graepel, T.; Hassabis, D. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 2016, 529, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, E. A.; Rashed, E. A.; Gaber, T.; Karam, O. Deep learning model for fully automated breast cancer detection system from thermograms. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0262349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Ye, Q.; Xia, J. Unbox the black-box for the medical explainable AI via multi-modal and multi-centre data fusion: A mini-review, two showcases and beyond. Information Fusion 2022, 77, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eertink, J. J.; Heymans, M. W.; Zwezerijnen, G. J. C.; Zijlstra, J. M.; de Vet, H. C. W.; Boellaard, R. External validation: a simulation study to compare cross-validation versus holdout or external testing to assess the performance of clinical prediction models using PET data from DLBCL patients. EJNMMI Res 2022, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raschka, S. Model Evaluation, Model Selection, and Algorithm Selection in Machine Learning. 2018.

- Vabalas, A.; Gowen, E.; Poliakoff, E.; Casson, A. J. Machine learning algorithm validation with a limited sample size. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0224365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J. D.; Chen, C.-y.; Knox, N. C.; Marrie, R.-A.; El-Gabalawy, H.; de Kievit, T.; Alfa, M.; Bernstein, C. N.; Van Domselaar, G. A comparative study of the gut microbiota in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases—does a common dysbiosis exist? Microbiome 2018, 6, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iablokov, S. N.; Klimenko, N. S.; Efimova, D. A.; Shashkova, T.; Novichkov, P. S.; Rodionov, D. A.; Tyakht, A. V. Metabolic Phenotypes as Potential Biomarkers for Linking Gut Microbiome With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front Mol Biosci 2020, 7, 603740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manandhar, I.; Alimadadi, A.; Aryal, S.; Munroe, P. B.; Joe, B.; Cheng, X. Gut microbiome-based supervised machine learning for clinical diagnosis of inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2021, 320, G328–g337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clooney, A. G.; Eckenberger, J.; Laserna-Mendieta, E.; Sexton, K. A.; Bernstein, M. T.; Vagianos, K.; Sargent, M.; Ryan, F. J.; Moran, C.; Sheehan, D.; Sleator, R. D.; Targownik, L. E.; Bernstein, C. N.; Shanahan, F.; Claesson, M. J. Ranking microbiome variance in inflammatory bowel disease: a large longitudinal intercontinental study. Gut 2021, 70, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liñares-Blanco, J.; Fernandez-Lozano, C.; Seoane, J. A.; López-Campos, G. Machine Learning Based Microbiome Signature to Predict Inflammatory Bowel Disease Subtypes. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biassoni, R.; Di Marco, E.; Squillario, M.; Barla, A.; Piccolo, G.; Ugolotti, E.; Gatti, C.; Minuto, N.; Patti, G.; Maghnie, M.; d'Annunzio, G. Gut Microbiota in T1DM-Onset Pediatric Patients: Machine-Learning Algorithms to Classify Microorganisms as Disease Linked. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Edreira, D.; Liñares-Blanco, J.; Fernandez-Lozano, C. Identification of Prevotella, Anaerotruncus and Eubacterium Genera by Machine Learning Analysis of Metagenomic Profiles for Stratification of Patients Affected by Type I Diabetes. Proceedings 2020, 54, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Edreira, D.; Liñares-Blanco, J.; Fernandez-Lozano, C. Machine Learning analysis of the human infant gut microbiome identifies influential species in type 1 diabetes. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 185, 115648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Cai, L.; Li, D.; Wang, X.; Zhao, S.; Zou, F.; Zhou, K. Metagenomics Biomarkers Selected for Prediction of Three Different Diseases in Chinese Population. Biomed Res Int 2018, 2018, 2936257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, S.; Yoo, D.; Kim, S. J.; Jhang, S.; Cho, S.; Kim, H. Establishment and evaluation of prediction model for multiple disease classification based on gut microbial data. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 10189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkova, A.; Ruggles, K. V. Predictive Metagenomic Analysis of Autoimmune Disease Identifies Robust Autoimmunity and Disease Specific Microbial Signatures. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Hou, Q.; Huang, S.; Ou, Q.; Huo, D.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Cen, C.; Cantu, V.; Estaki, M.; Chang, H.; Belda-Ferre, P.; Kim, H.-C.; Chen, K.; Knight, R.; Zhang, J. Compositional and genetic alterations in Graves’ disease gut microbiome reveal specific diagnostic biomarkers. The ISME Journal 2021, 15, 3399–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, V. K.; Cunningham, K. Y.; Hur, B.; Bakshi, U.; Huang, H.; Warrington, K. J.; Taneja, V.; Myasoedova, E.; Davis, J. M.; Sung, J. Gut microbial determinants of clinically important improvement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Genome Medicine 2021, 13, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjoa, E.; Guan, C. A Survey on Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Toward Medical XAI. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 2021, 32, 4793–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilvary, C.; Madhukar, N.; Elkhader, J.; Elemento, O. The Missing Pieces of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2019, 40, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilone, G.; Longo, L. Explainable Artificial Intelligence: a Systematic Review. 2020.

- Lu, X.; Tolmachev, A.; Yamamoto, T.; Takeuchi, K.; Okajima, S.; Takebayashi, T.; Maruhashi, K.; Kashima, H. Crowdsourcing Evaluation of Saliency-based XAI Methods. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.00456. [Google Scholar]

- Estivill-Castro, V.; Gilmore, E.; Hexel, R. Constructing Explainable Classifiers from the Start—Enabling Human-in-the Loop Machine Learning Information [Online], 2022.

- Guleria, P.; Naga Srinivasu, P.; Ahmed, S.; Almusallam, N.; Alarfaj, F. K. XAI Framework for Cardiovascular Disease Prediction Using Classification Techniques Electronics [Online], 2022.

- Xu, F.; Uszkoreit, H.; Du, Y.; Fan, W.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, J. In Explainable AI: A Brief Survey on History, Research Areas, Approaches and Challenges, Natural Language Processing and Chinese Computing, Cham, 2019//; Tang, J., Kan, M.-Y., Zhao, D., Li, S., Zan, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 563–574. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. 2017.

- Ribeiro, M. T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. "Why Should I Trust You?": Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Association for Computing Machinery: San Francisco, California, USA, 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Ntoutsi, E.; Fafalios, P.; Gadiraju, U.; Iosifidis, V.; Nejdl, W.; Vidal, M. E.; Ruggieri, S.; Turini, F.; Papadopoulos, S.; Krasanakis, E.; Kompatsiaris, I.; Kinder-Kurlanda, K.; Wagner, C.; Karimi, F.; Fernandez, M.; Alani, H.; Berendt, B.; Kruegel, T.; Heinze, C.; Staab, S. Bias in data-driven artificial intelligence systems—An introductory survey. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, F. S.; Michiels, S.; Shyr, Y.; Adjei, A. A.; Oberg, A. L. Biomarker Discovery and Validation: Statistical Considerations. J Thorac Oncol 2021, 16, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, F. E., Jr.; Lee, K. L.; Mark, D. B. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 1996, 15, 361–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircioğlu, A. Measuring the bias of incorrect application of feature selection when using cross-validation in radiomics. Insights Imaging 2021, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Amplicon sequencings | Great depth | Uneven amplification |

| More precise | Focus on specific fragment of genes (rRNA/ITS sequencing) | |

| Sequence a specific region (16s-, or 18s- rRNA) | Low enough resolution for species/subspecies identification-OTUs instead | |

| ITS and entire operon introduce more info | Not assess microbe’s function directly | |

| Shotgun sequencing | Theoretically sequence 100% of specimen | Rarely sequence everything of specimen |

| Greater resolution to genetic content | Sequence host/contaminant DNA | |

| Assess functional profiling | Produce very complex dataset | |

| Identify novel organisms/genes/genomic features | Costly | |

| Sequence host/contaminant DNA |

| Feature Selection Methods |

Subtype | Advantage | Disadvantage | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter method | Univariate | Computational inexpensive High efficacy Scalable Independent of any classifier |

Multi-collinearity Lack of interaction of feature with classifier |

Fisher’s exact test |

| χ2 test, | ||||

| Information gain | ||||

| Euclidean distance | ||||

| Mann-Whitney U test | ||||

| Multivariate | Feature dependencies Independent of any classifier High efficacy |

Computational expensive in comparison with univariate Lack of interaction of features with classifier |

Minimal-redundancy-maximal-relevance (mRMR) | |

| Fast correlation-based filter (FCBF) | ||||

| Mutual information feature selection (MIFS) | ||||

| Conditional mutual information maximization (CMIM) | ||||

| Relief based family |

Can handle non-linear relationships. Computational efficient Interaction between variables |

Sensitivity to the choice of distance metric Sensitive to parameter tuning. Limited to nearest neighbors |

Relief-f | |

| MultiSURF | ||||

| SURF | ||||

| Wrapper method | Heuristically search approach. | Less prone to local optima | High risk of overfitting Computational expensive |

Genetic algorithm |

| Ant colony optimization | ||||

| Sequential search method | High performance in contrast to filter method Feature dependencies Feature interaction with classifiers |

High risk of overfitting Computational expensive More likely to stuck at local optima |

Sequential forward selection (SFS) | |

| Sequential backward selection (SBS) | ||||

| Recursive feature elimination | More robust against stuck in local optima than sequential methods. Can handle noisy data. Can remove multiple features with less accuracy |

Sensitive to hyperparameters Limited interpretability |

Recursive feature elimination with random forest | |

| Recursive feature elimination with SVM | ||||

| Recursive feature elimination with logistic regression | ||||

| Embedded method | Penalization/shrinkage-based feature selection. | More robust against stuck in local optima than sequential methods. Can handle noisy data. Can remove multiple features with less accuracy. More effective than wrapper method in handling noisy data and handling inter-correlation between variables. Automatic feature selection |

Sensitive to hyperparameters Limited interpretability Difficult to select optimal regularization strength or penalization type. Not robust again non-linear relationship between variable and class |

Lasso |

| Elastic net | ||||

| Weight-based feature selection | Robust against handling complex relationship between dependent and independent variable More interpretable than penalization-based models |

Sensitive to hyper-parameters Sensitive to non-linear relationship |

Decision tree | |

| Random forest | ||||

| Naïve Bayes | ||||

| Hybrid method | Filter and wrapper combination | Efficient in accuracy than filter method Less complexity in comparison to wrapper Robust for high dimensional data |

Classifier dependent Inherit wrapper techniques complexities (overfitting) |

Hybrid genetic algorithm |

| Hybrid ant colony | ||||

| Fuzz random forest |

| Disease | Input | Aim of the Study | Feature Selection Algorithm | Classifier | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Different autoimmune diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis. | 16s RNA sequencing | To compare the gut microbiome associated with different autoimmune diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis. | Feature importance determined by Gini score using random forest | Random Forest | [72] |

| IBD | 16s RNA sequencing | To identify IBD-related microbial biomarkers | Principal component analysis (PCA) and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) | Random Forest | [73] |

| IBD & Subtypes | 16s RNA sequencing | To discriminate IBD from non-IBD and distinguish IBD subtypes as well | Linear discriminant analysis | Random Forest, SVM radial kernel, NNET, EN | [74] |

| IBD | 16S rRNA sequencing | Assess the compositional differences of the gut microbiome associated with lifestyle, diet and environmental factors in the development of IBD | Feature importance determined by Gradient boosted trees t | Gradient boosted trees | [75] |

| Inflammatory bowel diseases subtypes | 16S rRNA sequencing | To distinguish IBD subtypes: ulcerative colitis (UC) from Crohn’s disease (CD). | Kruskal-Wallis Tests, Fast Correlation Based Filter for Feature Selection (FCBF), Linear decomposition model, Differential abundance | Random Forest, Generalized linear model (glmnet) | [76] |

| T1D | 16S rRNA sequencing | To determine the association of gut microbes in T1D onset in children | Embedded feature selection with random forest | Random forest | [77] |

| T1D | 16S rRNA sequencing | Identified a potential genus for T1D Classification | - | Glmnet, Random Forest | [78] |

| T1D | 16s RNA sequencing | Categorise risk factors associated with the development of type 1 diabetes in infants. | Wilcoxon test | SVM, Random Forest, Glmnet | [79] |

| rheumatoid arthritis, liver cirrhosis and type 2 diabetes | Shotgun metagenomics | To identify biomarkers for three different diseases by multiclass classification | mRMR. | Random forest, SVM, logistic regression, KNN, gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT), AdaBoost, and stochastic gradient descent (SGD) were employed in this study. | [80] |

| Colorectal cancer (CRC), Multiple sclerosis (MS), Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) | 16s RNA sequencing | To distinguish gut microbiome from six different diseases using multiclass classification | Forward feature selection, Backward feature elimination | KNN, SVM, Logistic model tree, Logiboost | [81] |

| Inflammatory bowel disease, Multiple sclerosis, Rheumatoid arthritis, and general autoimmune diseases. | Shotgun sequence and 16s rRNA sequence | Compare and classify each autoimmune diseases by using machine learning algorithms | RFE used for feature selection in the study | XGBoost, Random Forest, SVM Radial, Ridge regression were employed for classification | [82] |

| Grave's disease | Shotgun metagenomic sequence | To investigate the relation between gut microbiota and Grave diseases with four layers data derived from shotgun metagenomics. | Wilcoxon rank-sum test, two-tailed | Random Forest | [83] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Shotgun metagenomic sequencing | To examine the gut microbiomes that are linked with the minimum clinically important improvement (MCII) in RA patients. | Multiple regression model | Deep neural network, Random Forest, SVM & Logistic regression | [84] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).