1. Introduction

Face recognition is one of the most important social skills in human social cognition. Humans are face experts capable of recognizing and remembering different individuals over a lifetime, often through mere exposure. Our human brain also evolved a special neural mechanism, the fusiform face area (FFA), which is dedicated to face perception and recognition (Kanwisher & Yovel, 2006; Loffler et al., 2005).

The ability to perceive and recognize faces depends on the analysis of specific facial characteristics, including the nose, eyes, lips, and skin texture. The features of a face can be described by two types of relational properties: first-order, which refers to the canonical positions of facial features (e.g., eyes are above nose and nose above mouth), and second-order, which includes the symmetry and spatial variations in these first-order relations (Diamond & Carey, 1986). The combination of these properties results in a wide range of facial variability, with some appearing typical and others more unique and distinctive. Atypical faces, which are more easily recognizable in a crowd due to their distinctive features, have been studied in previous research using typicality ratings (Tanaka et al., 1998; Valentine, 1991; Valentine & Bruce, 1986).

In the field of face perception and recognition, it is well-known that face distinctiveness or atypicality can impact a variety of judgments and processes, including the perception of face symmetry (Ryali et al., 2020), trustworthiness (Ryali et al., 2020; Sofer et al., 2017), attractiveness (Rhodes & Tremewan, 1996; Ryali et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2021), similarity (Tanaka et al., 1998), and memory recognition (Bartlett et al., 1984; Light et al., 1979; Valentine, 1991; Valentine & Bruce, 1986; Vokey & Read, 1992). For instance, research has demonstrated that atypical faces tend to be less symmetrical, less attractive, and less trustworthy than typical faces (Ryali et al., 2020). Apparently, due to such properties, atypical faces are more distinctive and are therefore more easily learned and better recognized than typical faces (Bartlett et al., 1984; Light et al., 1979; Valentine, 1991; Valentine & Bruce, 1986; Vokey & Read, 1992). For instance, in a study by Valentine (1991), participants completed a delayed matching-to-sample task in which they had to match two sequentially presented faces. The results showed that atypical faces were matched more accurately (i.e., higher A’— a measure of detection sensitivity, which accounts for participants’ response bias) and faster than typical faces, providing evidence for the benefits of atypical faces in memory recognition.

Especially germane to the present study, Tanaka et al. (1998) demonstrated an advantage of atypical faces in likeness judgments. Participants were asked to determine whether a morph face, which was a 50/50 combination of an atypical and typical parent face, more closely resembled the atypical or typical parent face. The results showed that the morph face was more often judged to resemble the atypical parent face, a phenomenon they referred to as the atypicality bias in likeness judgments.

The atypicality effect on recognition memory and likeness judgments can be understood using the "representational geometry" of face space, as proposed by the previous studies (Busey, 1998; Valentine, 1991, 2001). According to the multidimensional space (MDS) framework, which is regarded as a classical approach to understanding the organization of the mental representation of faces, faces are represented in the brain as points in a multidimensional space, in which each dimension serves to distinguish one face from another. The prototypical or norm face is located at the origin of this space, and the typicality of a face can be quantified by its distance from the norm face. Faces that are closer to the norm face or centroid, are, in this interpretation, by definition more typical, while those that are farther away are less typical. This idea has been supported by research, such as a study by Johnston et al. (1997) in which participants made similarity judgments of pairs of faces. The results of the multidimensional scaling analysis showed that, indeed, distinctive faces were represented in the outer regions of face space, while typical faces were located nearer the center, consistent with Valentine's proposal.

The "density hypothesis" is a proposed explanation for the atypicality effect on recognition memory within the MDS framework. According to this hypothesis, the exemplar density (i.e., the number of points representing different faces) in face space decreases as the distance from the prototypical (or norm) face increases. This means that atypical faces, located in sparser regions of face space farther from the norm face, have fewer neighboring faces competing for recognition. As a result, atypical faces are less likely to be confused with other faces and are more easily learned and accurately identified (Bartlett et al., 1984; Light et al., 1979; Valentine, 1991; Valentine & Bruce, 1986). In contrast, typical faces, located in denser regions of face space closer to the norm face, may be more easily confused with other faces due to the higher exemplar density in their region of face space.

Townsend et al. (2001) substantially generalized face-space theory by placing interpreting the basic concepts in terms of modern point-set topology, functional analysis, and infinite dimensional Riemannian spaces. They contended that no finite dimensional metric space was really equipped to encompass what must be at least akin to surfaces in 3-dimensional Euclidean spaces. This stance immediately implies even the raw representation of the face stimulus must be of the complexity of a space of continuous functions. Note that even a line drawing of the boundary of a profiled-face is a continuous function. Now, a topological space need not possess a metric. Although topologies permit, through notions of set-containment, how points can be more or less similar to one another, they cannot compare how the similarity of, say, point x to y is as compared to that of u to v though they all lie in the same space. For that, more structure is needed and the obvious go-to concept there is the existence of a metric.

1

It can be also seen that the popular approach utilizing eigen-faces is totally compatible with our function-space approach. We cannot go into much detail in the present account but refer the interested reader to the original chapter (please refer to Townsend et al. (2001)). We will return to the geometric approach shortly.

Within the concerns of the present work, the density hypothesis can also be applied to explain the atypicality bias in face likeness judgments. Tanaka et al. (1998) also rely on a spatial context but render the primary concept as dynamic rather than purely geometric by incorporating the idea of an attractor field (Tanaka et al., 1998; Tanaka & Corneille, 2007). According to the attractor field model, a single face representation can be activated by multiple face inputs in a "many-to-one mapping" known as an attractor field. The size of a face representation's attractor field is determined by the density of nearby representations in the face space. Atypical faces, located in a sparse region with a low density of exemplars, have larger attractor fields compared to typical faces. This means that a morph face, which is equally distant from both atypical and typical face representations, would be closer to the attractor field of the atypical face representation and therefore be more likely to be judged as similar to the atypical face. This argument is supportive of the attractor field model and lies in opposition to the nearest neighbor hypothesis (Shepard, 1962), which predicts that the morph face would be equally likely to be judged as similar to either the atypical or typical face.

Although the attractor field model predicts an atypicality bias in likeness judgments, the model predicts an inverse, atypicality disadvantage in perceptual discrimination, which is inconsistent with previous findings (Bartlett et al., 1984; Light et al., 1979; Valentine, 1991; Valentine & Bruce, 1986; Vokey & Read, 1992). That is, the attractor field model proposes that atypical faces have larger attractor fields, which should make them less sensitive to differences in physical features among different faces and therefore lead to poorer discrimination of atypical faces. Tanaka and Corneille (2007) supported this prediction with poorer discrimination of atypical faces, but this inconsistency with previous findings may also be due to the use of different stimuli in their study. While Tanaka and Corneille (2007) used morphs of typical and atypical faces, previous research used faces with different identities. It is possible that the use of different types of stimuli could explain the discrepancy in results.

We argue here that there are several weaknesses of the attractor field model for understanding mental representations of faces. One concern is that the model currently lacks mathematical support, making it difficult to confirm its assumptions through analysis or to use mathematical or computational modeling to simulate mental representations. Additionally, the extent to which morph faces resemble atypical faces is unclear, and the model does not consider the trajectory of decision-making processes, which involve vector fields and integration of velocities. That is, vectors are the derivatives of trajectory curves, and integrating the vectors, starting at a given point, reproduces the dynamic trajectory (Townsend & Busemeyer, 2014). Given that the morph face bears a stronger resemblance to the atypical face, it is assumed that the magnitude of the attendant velocities for the atypical face should be greater than that of the typical face, as well as having a larger ‘basin’ for atypical face compared to typical face. Therefore, these limitations make it difficult to fully understand the mental representation of faces using the attractor field model.

An additional limitation of the attractor field model is that it assumes a linear underlying metric, but the physical properties of faces may be nonlinear. This means that if the mental representation of faces is assumed to be a linear Euclidean space, people may make identification error; that is, mistaking two faces with different identities but the same view as the same faces and two faces with the same identities but different views as the different faces. Seung and Lee (2000) therefore proposed an alternative model in which the mental representation of faces is stored as a manifold of stable states, or a continuous attractor, which may better account for nonlinearity in the physical properties of faces.

Closely related to the points of the preceding paragraph, is the issue of measurement scales. While powerful cases can be made as to, say, accuracy lying on an absolute scale and response times on a ratio scale, it is unclear as to the proper scale for judgements of similarity (Suppes et al., 1989; Townsend, 1992; Townsend & Ashby, 1984). Without further quantitative underpinning, there is currently no reason to take such a scale as anything stronger than ordinal. In fact, it is not obvious even that established morphing procedure should result in the type of linear relations proposed by Tanaka and colleagues (Tanaka et al., 1998; Tanaka & Corneille, 2007).

The position taken in the present study is several-fold: (1) In our view, unlike the milieu of approach-avoidance decision making (Hull, 1938; Lewin, 1936; Miller, 1944; Townsend & Busemeyer, 1989; Townsend & Wenger, 2014), the inherent dynamics of attractor fields are not especially appropriate or helpful. (2) In conjunction with (1) and following in the tradition of the classical linkage of geometry and pattern perception and recognition and in particular within the discipline of face processing, we believe that an expressly geometric-face-space approach is more natural and leads to greater insight and perhaps testable qualities. (3) Following the earlier remarks, the psychological dimensions or features of a face should be embedded in the Riemannian manifold milieu.

Taken together, the present study aims to explain the psychological distance and density of faces in the face space using a gradient vector and infinite dimensional Riemannian geometry. The use of a weight function in the Riemannian metric allows for the resolution of the atypicality bias in likeness judgments and provides a mathematical prediction. Additionally, this approach has the potential to address the inconsistency in the attractor field model.

2. Methods

Our basic postulate is that typical faces can exhibit physical differences as much or as little as atypical faces. This principle is compatible with Tanaka’s implicit assumption that, for example, ordinary morphing procedures can be associated with flat (i.e., no curvature allowed) spaces that are homogeneous in distinct parts of the space (e.g., across races or typicality). Typical spaces of this nature include all the power metrics (e.g., Euclidean, city-block, etc.) but even more general Riemannian metrics can, but need not obey this dictum.

However, we require a metric that varies as one moves about face space. For this reason, we utilized the Riemannian Face Manifold (RFM) to represent faces (Townsend et al., 2001), along with a Riemannian metric in an infinite-dimensional face space that changes as we move from more typical to less typical faces. Again, the concept of RFM expands on Valentine's (1991, 2001) face space by incorporating Riemannian geometric properties, which is different from Euclidean geometry as well as many other distance-type spaces (Valentine, 1991, 2001).

Riemannian geometry is capable of dealing with curved spaces, specifically smooth manifolds with a Riemannian metric that characterizes the local geometry of the manifold by providing a smoothly changing inner product to each tangent space on the manifold.

2 Einstein’s general relativity theory is of this nature. This metric is used to define distances and angles between points, and explore geometric features such as curvature, geodesics, and volume. As just observed, in contrast to Euclidean geometry, Riemannian geometry permits the possibility of curvature, allowing parallel lines in Riemannian geometry to converge or diverge depending on the curvature of the underlying space. The concept of RFM extends this framework to an infinite-dimensional space of faces, assigning a Riemannian metric that provides the inner products similar to dot products in Euclidean spaces, and allowing for the concept of closeness, geodesics (the shortest distance between two points on the manifold), angles, potentially (as in general relativity theory), and curvature. By doing so, RFM offers a more nuanced understanding of the geometric properties of faces beyond the Euclidean framework of traditional face space.

Under the framework of RFM, we proposed that the actual psychological metric perceives more "change" when moving from a face in sparsely populated regions to a neighbor than when moving from a face in densely populated regions to a neighbor that would be considered similar in a more uniform space. This implies that faces located in sparsely populated regions would be perceived as further apart than faces that are equally physically distant but located in densely populated regions.

To facilitate our comprehension, we provide a brief explanation of how the Riemannian metric operates in a finite number of dimensions, specifically in two dimensions as an example. The implementation of a 2-dimensional subspace is perfectly compatible since, for instance, two distinct face-points determine a line, three face-points determine a 2-space and so on. The original chapter by Townsend, Solomon, & Spencer-Smith provides more explication of this concept.

In any case,

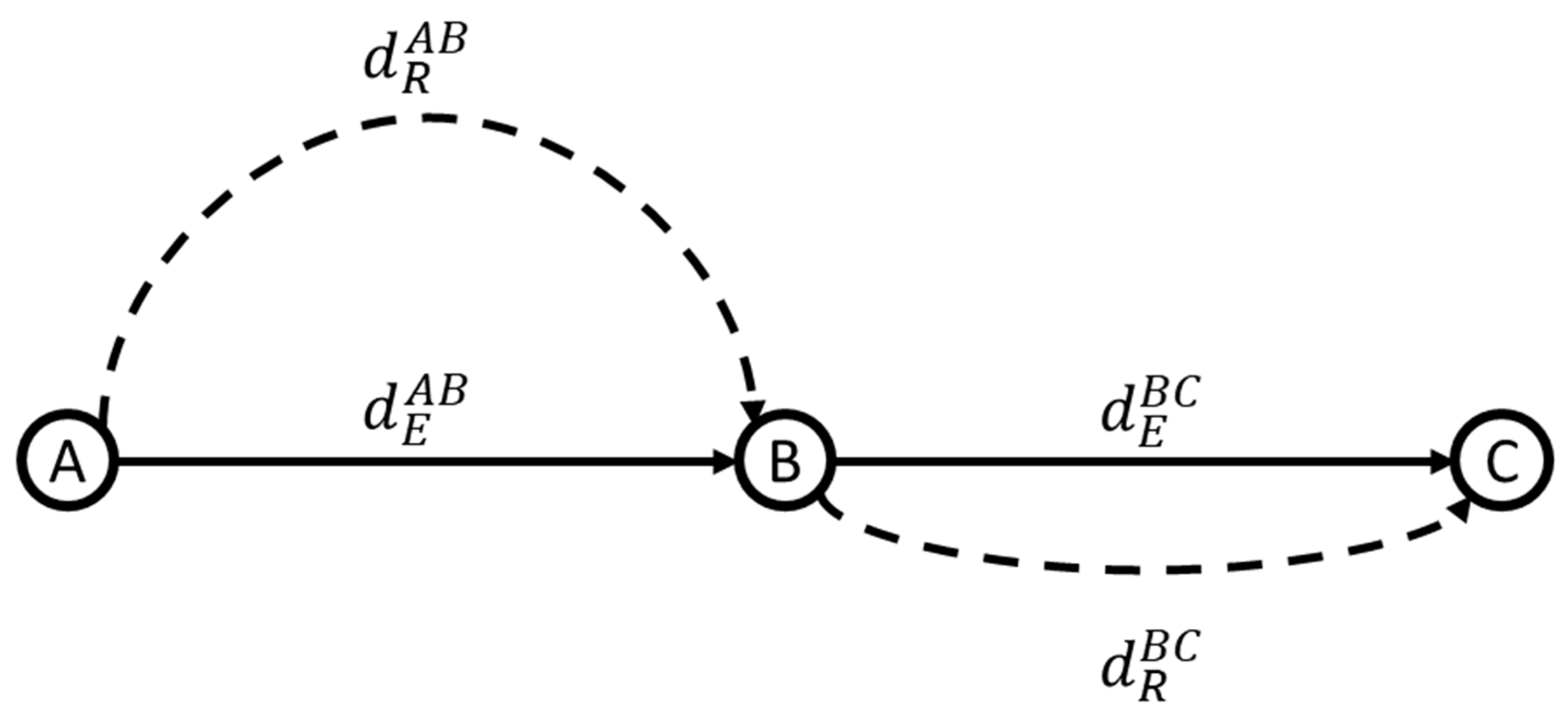

Figure 1 illustrates the qualitative difference between the Euclidean distance and the Riemannian distance. When moving from Point A to Point C through Point B, the solid lines labeled as

and

represent the Euclidean distances between each point where

. However, the dashed lines labeled as

and

represent the walking path distance or arc length where

. These points can be interpreted as face stimuli in Tanaka et al.'s (1998) study. Participants had to determine whether a morph face (

, Point B), a combination of a typical (

, Point A) and an atypical (

, Point C) parent face, resembled the atypical or typical parent face more closely. Although the distance between the morph face and the typical face and that between the morph face and the atypical face was presumed to be equal (

), their results revealed an atypicality bias, indicating that participants perceived the morph face as being more similar to the atypical face. We contend that this bias can be captured by the Riemannian metric, specifically

, which we will demonstrate in the subsequent section.

We now employ a simple example to illustrate how faces can be represented in a 2-dimensional features subspace designated by ). Then, any face in this plane can be described as a function of t, denoted as . We next define a metric, designated as , in this space, which can only be estimated through a geodesic path. In a similar manner to Townsend et al. (2001), we can also map a cylinder onto a face. However, for the sake of simplicity, we will use a simplified space of a profile generated as a function on an interval of the real line. To avoid the complexity of generating a geodesic, we assume that the path has already been laid out to be the shortest path length.

In a Riemannian space, we need a

metric operator (covariant tensor),

, that is sufficiently smooth (e.g., differentiable), where

is the dimension of face space (i.e.,

), and subscripts

and

refer to the matrix index. A Riemannian manifold is a vector space locally equipped with an inner product. By integrating the inner product, which inherently involves the metric, over the shortest path between two faces, we can obtain the Riemannian distance, denoted as

. The expression for the Riemannian distance of the path is:

It's worth noting that even in this simple example, the Riemannian metric allows for interactions between dimensions (i.e., when

i ≠

j). The pair

describes a path or curve in a 2-dimensional space, and the metric

determines how the dimensions interact to produce length as one moves along the path. The metric is a function of the contemporary point in the plane (

and

) for each pair of

i and

j, with symmetry (i.e.,

=

). To simplify the calculation, we define

, where the typical face is located, and

, where the atypical face is located. The intermediate faces, as t varies from 0 to 1, are the sequence of “morphs” or the curve that connects the two faces.

The reader may observe that if the metric operator

is an identity matrix, the Riemannian distance can be simplified to the Euclidean distance (

) and is expressed as:

In order to explore this effect within a finite dimensional face space, we employed both Euclidean and Riemannian metrics to measure the distances between the 50/50 morph face () and its typical () and atypical () parent faces. Our hypothesis was that a smaller distance between the morph face and a parent face would increase the likelihood of that parent face being selected. By using this method, we aimed to illustrate how the RFM can effectively account for the atypicality bias observed in the data.

Assume and , so that the face . Consequently, the atypical face is located at () when t=1, and the morph face is located at where . By applying a metric tensor (see Equation 1), we can identify the Riemannian distance () between two faces, which reflects the psychological distance, i.e., the degree to which the faces are judged to be similar. We can also consider the Euclidean distance () between the morph face and the two parent faces, which reflects the distance based on physical features (see Equation 2).

Here, we choose a simple metric tensor that is a slight deviation from that appearing in Townsend et al. (2001) as follows:

where

is the Euclidean distance to the origin (prototypical face). For example, for face

,

is expressed as:

where

is the adjustable parameter.

Specifically, the Riemannian distance between the morph face and the typical/atypical parent faces can be expressed as follows:

In addition, the Euclidean distance, viewed here as the physical description of the stimulus faces, between the morph face and the typical/atypical parent faces can be expressed as follows:

In order to test the predictions of the RFM, we examined the relationship between the morph face and the typical face in terms of both physical distance

, morph level) and psychological distance (

, response proportion of the typical face in likeness judgments), using a simple metric tensor

while varying the adjustable parameter

k. To simplify, we assumed

and

. The RFM predicted that the proportion of resemblance to the typical face would decrease as

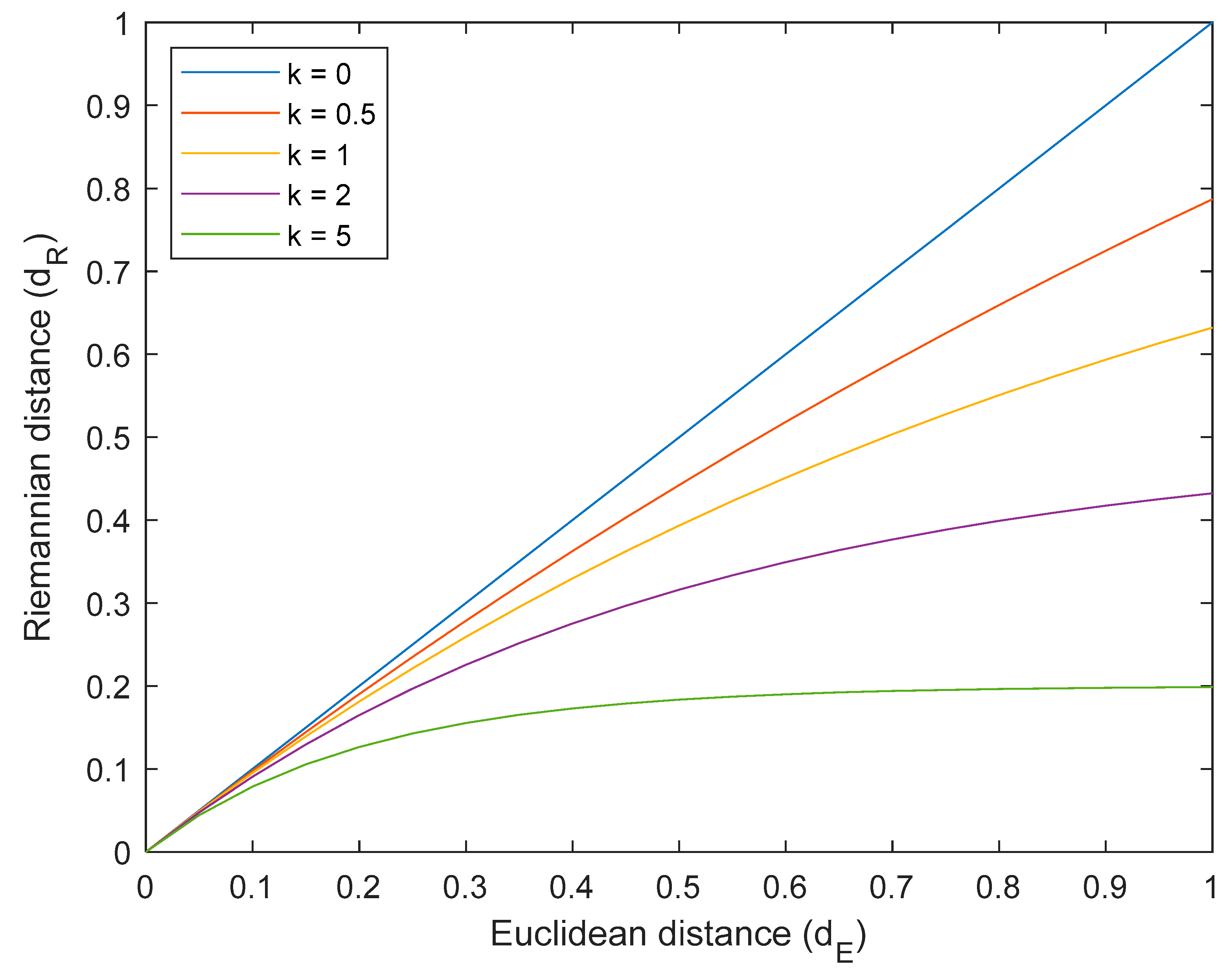

k increases, as shown in

Figure 2. It indicates that the distance (

) from the morph face

to the typical face is longer than that to the atypical face. This aligns with previous research on the atypicality bias in likeness judgements (Tanaka et al., 1998). Notably, if

is 0, there would be no difference between Euclidean distance and Riemannian distance; in this case, a 50/50 morph face would be equally similar to both typical and atypical faces.

3. General Discussion

Summary

We applaud the earlier efforts of Tanaka et al. (1998) in deepening our knowledge and the theoretical questions concerning what is basically the homogeneity of face space and in this way extending preceding finding and discussions such as those of Krumhansl (1978). However, we propose that a purely geometric approach is considerably more appropriate than their line of attack founded on what are in essence, dynamical systems. In contrast to, for instance, Einstein’s theory of gravitation, the dynamics in Tanaka’s model have not been endowed with a clear psychological raison d’etre.

So next, moving to the discussion of geometry per se, our prior theoretical study (Townsend et al., 2001) establishes our position that the appropriate geometric milieu is that of an infinite dimensional Riemannian manifold. The human perceptual face-metric is extremely unlikely to be Euclidean or indeed, any flat (i.e., 0-curvature) type of distance measure. Furthermore, the obvious use of curvature, even in description of many features, for example, the curvature of a chin, indicates the need for a 2-or-3 dimensional space at least at the level of continuous function spaces (Bachman & Narici, 2000).

Here, it should be observed that even the more general power metrics so popular in psychology (e.g., Shepard, 1964), multi-dimensional scaling routines (Kruskal, 1964) and possessing elegant rigorous, but psychologically motivated axiomatic treatment (Luce et al., 2007) are very limited in some ways: (1) As noted before, they are incapable of capturing ordinary notions of curvature. (2) Closely related to (1), the dimensions cannot interact. For example, it is widely accepted that round faces should be offset by wearing of longer hair styles—whether true or not in this case, it is a clear instance of dimensional interaction if in a rather mundane setting! The kind of interactions investigated by General Recognition Theory (Ashby & Townsend, 1986; Kadlec & Townsend, 1992; Townsend et al., 2012) and involved in gestalt and configural perception (Townsend & Wenger, 2014) can require spaces endowed with curvature. (3) These metrics are space-homogeneous in the sense that they do not measure distance differently as one moves to different regions of the space, exactly the opposite of what we propose here.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to use the Riemannian Face Manifold (RFM) to explain the psychological distance between face stimuli in a face space. The RFM is a mathematical framework that includes gradient vectors and infinite-dimensional Riemannian geometry. The RFM is a vector space with an inner product that can be used to calculate the distance between two faces by integrating this inner product over the shortest path (i.e., geodesic) between them. By using a weight function in the Riemannian metric, we can refine our understanding of the atypicality bias in likeness judgments reported in previous studies (Tanaka et al., 1998) and provide mathematical predictions.

By applying the RFM, we calculated the psychological distances between the morph face and its parent faces (typical or atypical) in the Riemannian metric. By employing a simple metric tensor , we demonstrated the relationship between the morph and typical faces in terms of physical distance (i.e., morph level) and psychological distance (i.e., resemblance to the typical face) while varying the adjustable parameter k. The RFM prediction indicated that the psychological distance from the morph face to the typical face was longer compared to that to the atypical face, which aligns with prior research that found a morph face with weaker resemblance to the typical face decreases the likelihood of the typical parent face being chosen in likeness judgments (Tanaka et al., 1998). In particular, as we adjustable the parameter k to higher values, the psychological distance between the morph face and the typical face increased, leading to a reduction in the likelihood of selecting the typical face in likeness judgments.

The RFM can also shed light on the observed poor discrimination between atypical and morph faces reported by Tanaka and Corneille (2007). In their study, participants demonstrated a weaker ability to differentiate atypical faces from the morph face compared to typical faces, despite the fact that both types of faces were equidistant from the morph face at the same morph levels.

We pointed out in the introduction that it is a strong assumption that standard morphing procedure should necessarily lie in any particular space, let alone Euclidean. How would one even test such an axiom? From that perspective, we can only say that postulating that assumption, we can then test non-flat metrics in opposition to it.

Taking that stance, our result can be explained by the RFM's calculation of the psychological distance between faces in the Riemannian metric. Specifically, the shorter psychological distance between the atypical face and morph face leads to a stronger perceived resemblance and a weaker ability to discriminate between the two faces. This finding underscores the importance of considering psychological distance, in addition to physical distance, when studying face perception and discrimination.

It is important to highlight that the adjustable parameter k plays a crucial role in the RFM's predictions. When k is set to zero, the metric of the face space becomes flat, and the predictions of the RFM are equivalent to those of Euclidean distance. In this situation, physical feature distance and psychological distance are not distinguished, and a morph face with a 50/50 combination of typical and atypical faces would show an equal resemblance to both parent faces. However, when k is set to a non-zero positive value, the metric of the face space becomes Riemannian, and the RFM can differentiate between physical distance and psychological distance, resulting in the model's ability to provide more accurate predictions.

The distinction between physical and psychological distances is an essential aspect of the RFM. Physical distance (under the above postulate!) measures the amount of change in the morph level of the face, whereas psychological distance measures the perceived resemblance between face stimuli. With the RFM, it is possible to manipulate the parameter k to model different degrees of psychological distance between the morph face and its parent faces, allowing for a more precise prediction of perceived resemblance between the morph and parent faces.

Therefore, the RFM provides a framework for understanding the mechanisms that contribute to face perception and recognition. The RFM allows us to quantify and manipulate psychological distance, which could explain why atypical faces were more difficult to discriminate from the morph face. By computing the Riemannian distance between faces, we can determine the psychological distance. Again, we stress that our proposed infinite dimensionality should not scare off behavioral and neuro-scientists. This milieu, along with some standard regularity conditions permits a decomposition into a countable number of dimensions. The latter can then, if required, be ordered as to their importance to specific perceptual and cognitive purposes and permit the ‘dropping off’ of dimensions of lesser importance (through the magnitude of the attendant eigen-functions) to circumstances or task. Our approach thus links up with methodologies in face perception based on principal component analysis and it’s eigen-function decomposition (e.g., O'Toole et al., 1997; O'Toole et al., 2001). As a side-note, it might also be noted that this type of approach resides in psychological and psychometric history to the early utilization of principal component analysis in test assessment of mental characteristics (e.g., Spearman, 1904; Thurstone, 1924).

Furthermore, the RFM's ability to account for the atypicality bias in likeness judgments and the poor discrimination of atypical faces suggests that it is a promising tool for investigating the cognitive processes underlying face perception. Future research could use the RFM to explore how individual differences, such as face recognition abilities and expertise, affect psychological distance and its impact on face processing. Additionally, the RFM could be applied to other domains, such as object recognition, where psychological distance and similarity play a critical role.

Implications: What is the parameter k?

The psychological mechanism of the parameter k in the RFM is a topic of ongoing investigation, and there are several possible explanations. One of these is based on the idea of familiarity or experience. According to this view, the parameter k reflects the degree of difference in exposure to faces between two given faces. In other words, if two faces are very different in terms of how frequently they are encountered or how much attention they receive, then the value of k for those faces would be higher, resulting in a larger difference in inter-face distances in the face space.

This is supported by studies that have found that people are better able to discriminate between faces that are more dissimilar in terms of their familiarity (Jenkins et al., 2011). This account can be extended to explain the own-race bias (ORB) phenomenon (Meissner & Brigham, 2001; Platz & Hosch, 1988; Yang et al., 2018), where people are generally better at recognizing faces from their own racial group than from other racial groups. This bias may be due to people having more experience with faces from their own racial group, leading to a higher value of k and a greater separation in face space between same-race faces compared to other-race faces (Hugenberg et al., 2010).

Supporting this idea, Byatt and Rhodes (2004) found that own-race faces were identified more accurately and used MDS analysis on similarity ratings to demonstrate that other-race faces had smaller inter-face distances. Similarly, Papesh and Goldinger (2010) used MDS analysis on reaction times during 'same-different' judgments to demonstrate that other-race faces had lower mean inter-face distances in the face space. These findings suggest that people's familiarity or experience with faces plays a crucial role in shaping their perception and recognition abilities.

Moreover, Tanaka et al. (2013) conducted a study in which participants were trained to differentiate other-race faces at the individual subordinate level. This training resulted in improved recognition of untrained other-race faces and an increase in inter-face distances of other-race face representations in the face space. These findings indicate that face perception and recognition are plastic and dynamic and can be modified through perceptual experiences. The idea that the parameter k in the RFM reflects the degree of familiarity or experience with faces is a promising area for further research and may help to better understand the complex interplay between physical and psychological factors in face perception

Limitations of the Current Study and Proposed Experiments for Validating the RFM-Based Framework

Although the RFM framework is significant, a major limitation of the present study is the absence of any further substantiating empirical evidence. One of our key assumptions, that the typical face is located at the origin and the atypical face is located at the outer region seems innocent enough in displaying our Riemannian metric logic. Nonetheless, the aforementioned inhomogeneity of a metric might imply that though the qualitative aspects of our derivations are correct, they cannot, at this time, be endowed with any absolute meaning. Of course, the same is true of all other accounts excepting that of a Euclidean metric where spatial translation (e.g., to a new origin) leaves distances invariant. However, we think this homogeneity is a price too much to pay in its lace of scientific verity.

Additionally, our predictions about the relationship between physical and psychological distances should also be tested. Therefore, we suggest several experimental designs that could potentially verify the hypotheses and predictions of the RFM.

One possible experimental design to investigate the psychological distance between typical/atypical and morph faces is to adapt Tanaka et al.'s (1998) Experiment 4 (Tanaka et al., 1998). In this experiment, a linear continuum of morph faces is generated by varying the contributions of typical and atypical parents. Participants make "match-to-sample" judgments about the morph faces, and MDS analysis on similarity ratings could be used to determine the location of each face in the face space. This design could be modified to investigate the psychological distance between typical/atypical and morph faces in the RFM.

Similarly, the psychological distance between own-race and other-race faces can be estimated. Participants could be presented with a set of own-race and other-race faces and asked to rate the similarity between the faces. MDS analysis could be used to determine the physical and psychological distances between the faces, and whether there is a difference in the distances between the own-race and other-race faces.

Overall, future studies are needed to investigate the face representations of both typical/atypical and own-race/other-race faces in the RFM. By conducting empirical experiments, we can verify the hypotheses and predictions of the RFM, and gain a better understanding of the complex interplay between physical and psychological factors in face perception.