1. Introduction

Zinc hydrometallurgy is the main pathway for extracting zinc metal from zinc sulfide concentrate. It is divided into conventional and direct routes. The direct route includes steps of oxygen pressure/atmospheric pressure leaching, purification, and electro-deposition, which adopts whole-wet technology and avoids the high-temperature process of oxidizing roasting. In the leaching process, the solid sulfur enters the residue phase, avoiding emission of polluted SO2 gas. The sulfur content in the leaching residue1 is generally as high as 40%-60%, which attracts extensive studies to recycle it.

Flotation-hot filtration method2, 3 is predominant for recycling element sulfur in the high-sulfur residue, due to its simple process, low-cost production and feasible scale-up. Therefore, it has been widely used in the oxygen pressure leaching of zinc refineries4-7. However, this approach causes a low recovery rate. To address the challenge, introducing flotation agents8, 9 into the targeted solution is an effective approach. The collector, as a flotation agent, serves to improve collection efficiency of target mineral phases and promote their separation. Generally, the collector is composed of mineral-friendly and hydrophobic groups, the former supporting its adsorption on the mineral phase and thereby changing the hydrophilicity and floatability.

Diethyldithiocarbamate(DDTC)10 is a robust collector used in the sulfide ore flotation, with a strong collection ability11. Niu et al.12 found that DDTC could significantly improve the separation efficiency of pyrite and galena in the high-alkaline lime system. Zhang et al.13 found that adding DDTC caused desirable flotation performance in the jamesonite despite of a wide range of pH 2~13. Characterized by fourier transform infrared spectra (FT-IR), DDTC adsorbed on the surface of jamesonite in the form of lead- diethyldithiocarbamate. Cui et al.14 used a mixed collector containing diisobutyl dithiophosphite and DDTC to improve the flotation performance of jamesonite, which resulted in an improved recovery of 98.85% of jamesonite. Another interesting finding was that combining DDTC with butyl xanthate significantly improved the stability of foam during the flotation process, which increased the volume of maximum foam layer by 102% and prolonged the half-life of foam by 129%15. However, despite of extensive studies on the technical feasibility and improvement of the flotation process with DDTC, there is a knowledge gap on its interfacial adsorption mechanism.

Recently, density function theory (DFT) calculation is becoming an important method to study the adsorption performance on the mineral phase from the molecular level. For instance, Liu et al.1 studied the adsorption properties of xanthate, dithiophosphate and isopropyl-ethylthiocarbamate on the mineral phase of high-sulfur residue. Zhang et al.16 studied the flotation separation performance of dithiophosphate galena and sphalerite using DFT calculations. Huang et al.17 used theoretical chemical knowledge to modify xanthate collectors and used DFT calculations to predict the performance of modified xanthate collectors.

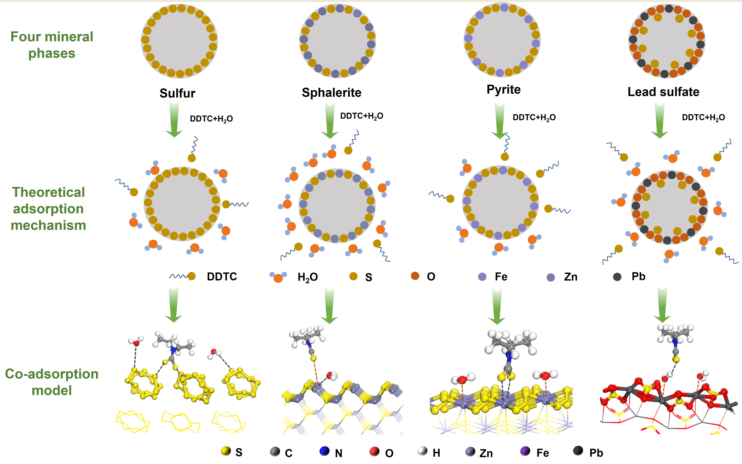

In this work, we investigated the interfacial adsorption of DDTC in the high-sulfur residue flotation. Four types of mineral phases—sulfur, pyrite, sphalerite and lead sulfate—were often existed in the high-sulfur residue. Firstly, the adsorption behavior—adsorption structure and energy and electron localization function (ELF) cross section—of DDTC and H2O on the four minerals phases were explored using DFT calculation. Then, a co-adsorption model of DDTC and H2O was constructed using DFT calculation, which was validated by the pure minerals flotation operation and the FT-IR results. Finally, practical bench-scale operation of high-sulfur residue flotation was performed, the result of which was elucidated synergistically by our developed model and the mineral fugacity pattern analysis. Overall, it was the first time to propose the validated co-adsorption model of DDTC and H2O, which gained insights into the interfacial adsorption mechanism in the high-sulfur residue flotation.

2. Methods

2.1. DFT Calculation

The structure searching on DDTC molecule was performed in an open-source software Xtb developed by the Grimme’s group

18, 19. And then its structure was further optimized in the Gaussian. Specifically, the DDTC molecule was optimized in the base group of m062x/6-311++g(2d,p), and then subject to frequency calculations to determine its structure plausibility. The surface electrostatic potentials of DDTC were calculated in the Multiwfn

20 (details in

Supplemental Material S1).

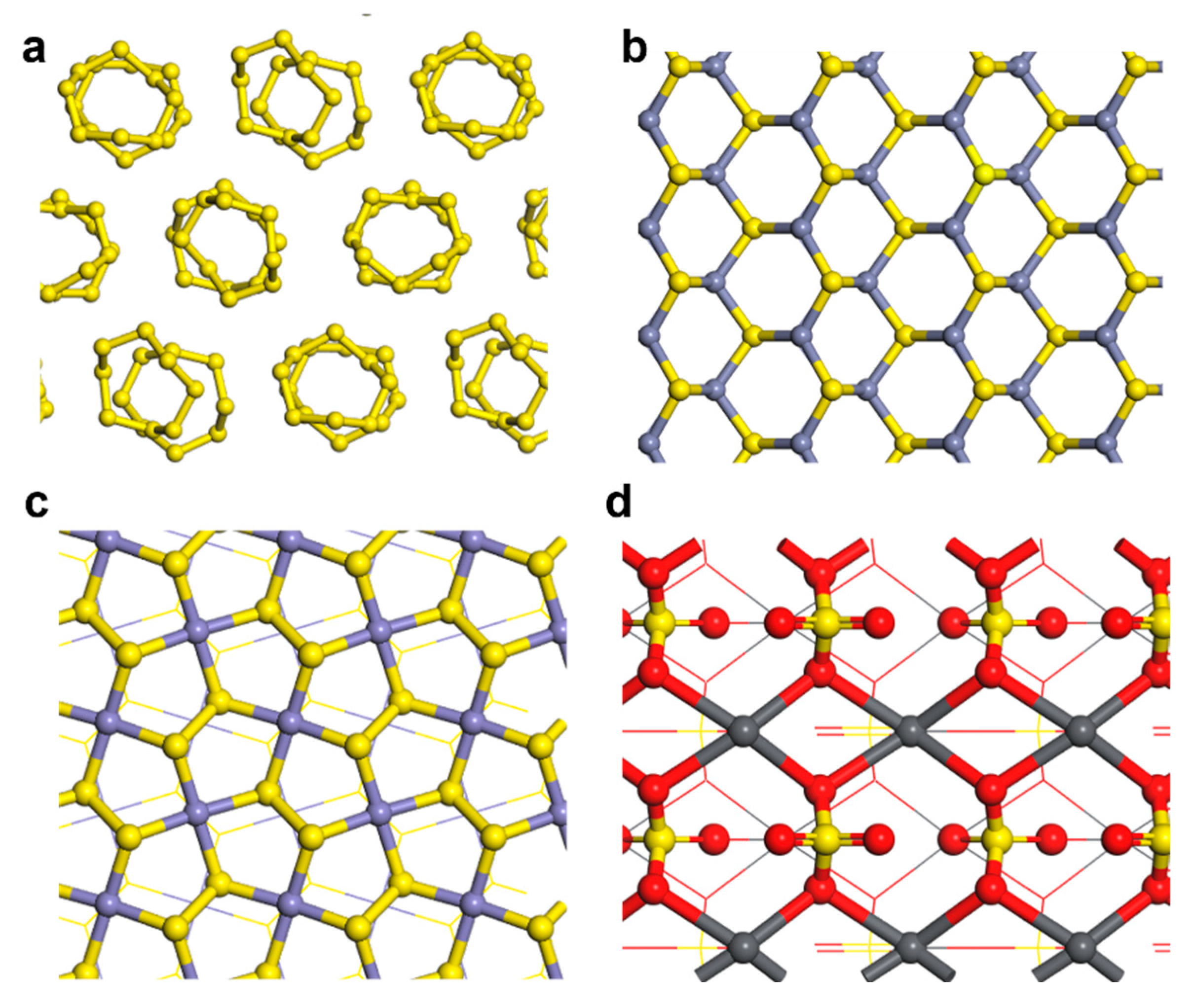

The high-sulfur residue contained four main mineral phases: sulfur, sphalerite, pyrite and lead sulfate. The most stable surface of sulfur S

(110), sphalerite ZnS

(110), pyrite FeS

2(100) and lead sulfate PbSO

4(001) were intercepted

1, 21, 22. The surface was optimized in a restricted way, relaxing one surface and three layers of atoms in each mineral phase. The thickness of the vacuum layer during relaxation process was 20 Å. The optimized structure was shown in

Figure 1.

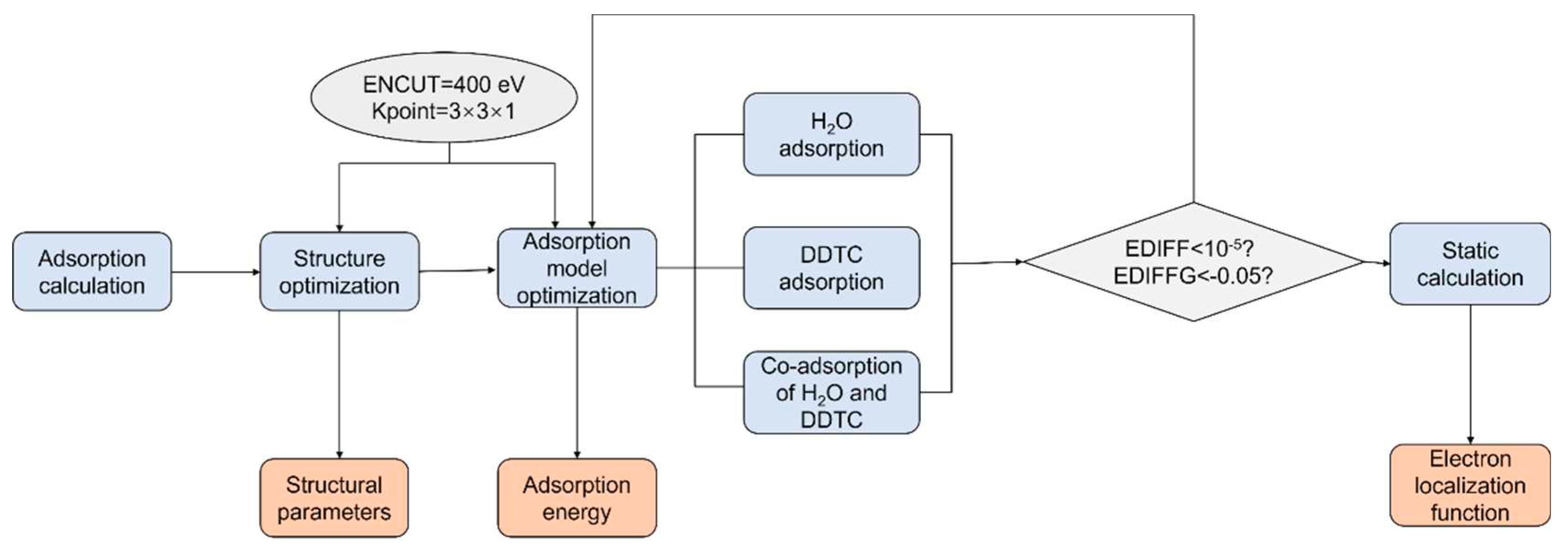

The adsorption process on the mineral phase surface was simulated and calculated in the DFT software VASP (

Figure 2). The generalized gradient approximation was used for the exchange correlation generalization. The pseudopotential was PBE. The surface was optimized by the conjugate gradient method with a plane wave truncation energy of 400 eV. The Monkhorst-Pack method was used to generate a 3×3×1 K-point grid. The energy convergence threshold for the self-consistent field iteration of the surface optimization was 10

-5 eV. The geometry optimization criterion was less than 0.05 eV/Å per atom around the force (details in

Table S1).

After optimization of the H2O adsorption model and DDTC adsorption model, self-consistent calculations were performed to obtain accurate electronic structure information. The electron localization function16, 23 (ELF) was subsequently obtained in Vesta24. The ELF was a common method to characterize bonds formed between atoms. The molecular orbitals generated by DFT calculation were denoted as Canonical Molecular Orbitals (Canonical MO). The MOs tended to be non-localized and therefore did not correspond to chemical bonds. To directly link the orbitals to the chemical bonds, we transformed MO into localized molecular orbital (localized MO, LMO). The ELF was a common method of localizing the orbitals. When the value of ELF was close to 1 between two atoms, this implied that there were localized electrons. And thus, there was a chemical bond between them.

2.2. Material and reagents

2.2.1. High-sulfur residue

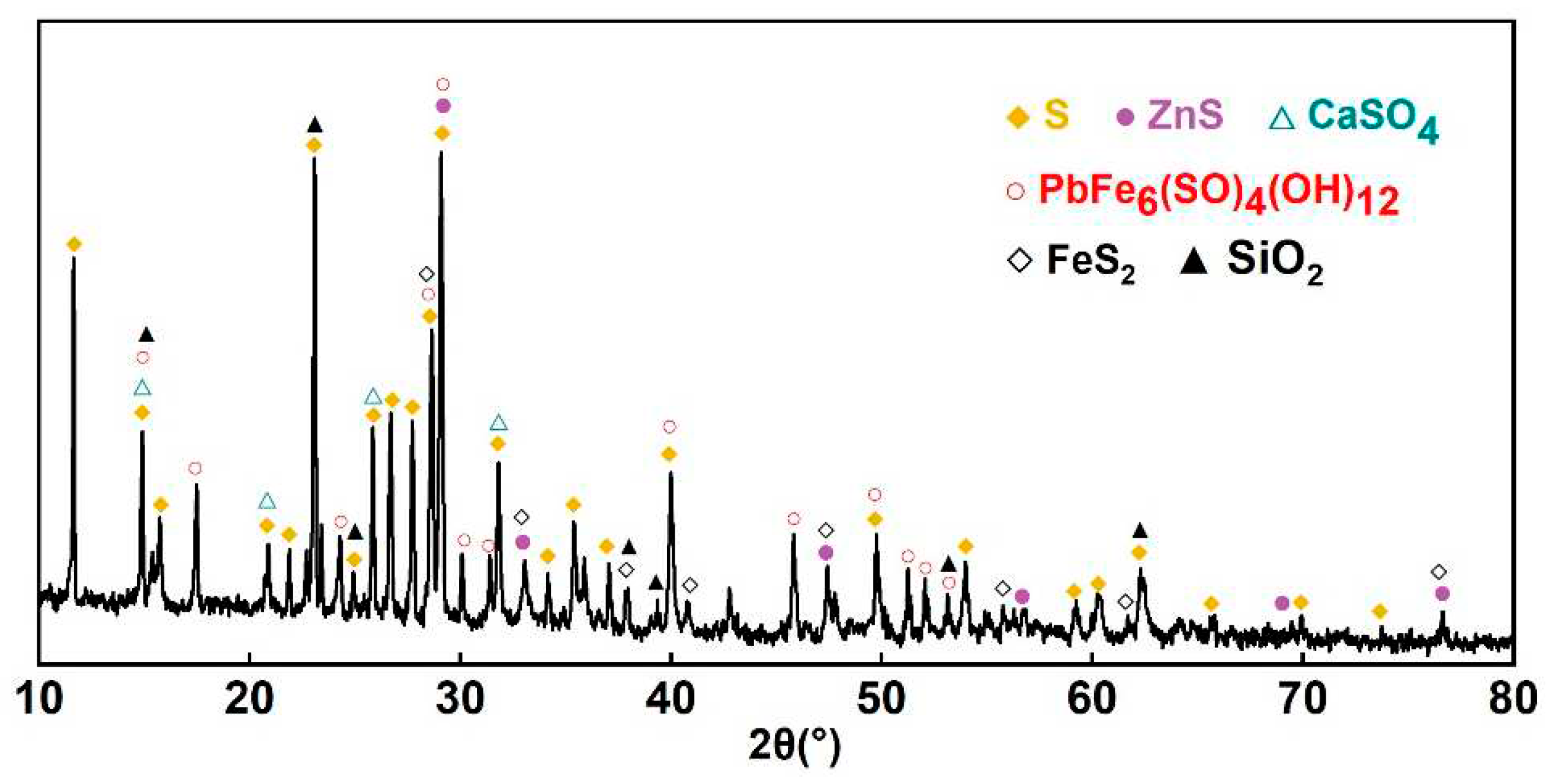

The composition of the high-sulfur residue was analyzed by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy analyzer (XRF), and its result was recorded in

Table 1. The phase of the high-sulfur residue was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD), and its result was shown in

Figure 3. The result indicated that the high-sulfur residue contained valuable elements such as S, Fe, Zn, Cu, Pb, Ag, gangue elements such as Ca, Si, Mg, Al, and poisonous element such as As, Cr, Se, Hg. The main phases in the high-sulfur residue were sulfur (almost 32.98%), sphalerite and pyrite.

2.2.2. Pyrite

The composition of the pyrite was analyzed by XRF, and its result was recorded in

Table 2. The phase of the pyrite was analyzed by XRD, and its result was shown in

Figure 4. The result indicated that the pyrite used in the experiment contained Fe, O, S, Si, etc., and the main phases were Fe

1-xS and SiO

2.

2.2.3. Reagents

The details of other reagents were shown in

Table 3.

2.3. Mineral flotation evaluation

2.3.1. Pure mineral flotation

The flotation tests were carried out in a 1.5LXFD pure-cell flotation machine, and 150 g of raw materials were weighed each time to prepare a 10% pulp solution. The concentration of DDTC was 0, 100, 200, 300, 400 and 500 g/t. The flotation temperature was 25 °C. The air volume flow rate was 300 L/h. The slurry pH was 8, and the flotation time was 10 min. The corresponding flotation agents were added to flotation machine according to the experimental requirements. Pure mineral tests used the weighing method to calculate the flotation recovery rate.

2.3.2. Adsorption behavior of DDTC on pure minerals

10 g of minerals was taken in a beaker, and then the pulp concentration was adjusted to be 10% material liquid. DDTC was added in beaker, with the concentration of DDTC being 300 g/t and pH=8. The slurry was stirred at 25 °C for 30 minutes and filtered. The filtered residue was washed for three times and dried for subsequent characterization. Nicolet 6700 Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR, Thrmo Fisher Scientific, USA) was used to analyze the surface structure before and after the interaction of DDTC with pure minerals.

2.3.3. High-sulfur residue flotation

The test conditions were pulp concentration 15%, flotation time 15 min, pulp temperature 25 °C, air volume flow rate 300 L/h, pH=8, and DDTC concentrations 100, 200, 300, 400 or 500 g/t. After the flotation process, the sample was filtered. The residue was washed and dried for characterizations.

2.3.4. Analysis and characterization

The sulfur was extracted by carbon tetrachloride method. 0.100-0.150 g of dry material was added to carbon tetrachloride for 20 min of sonication, and then the filtered residue sample was put into a platinum tray, and then steamed dry for weight quantification. The sulfur content in the high-sulfur residue was determined by carbon tetrachloride microwave method. To ensure the test accuracy, a mean value, obtained by three tests, was collected as the final result.

X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (Axios, PANalytical) was used to analyze the composition of the high-sulfur residue and to perform semi-quantitative analysis of various element distribution in the concentrate and tailings.

A SEM-EDS (MIRA4 LMH from TESCAN) was used to characterize the morphology in the concentrate and tailings after the high-sulfur residue flotation.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Co-adsorption model of DDTC and H2O

3.1.1. Adsorption behavior of DDTC

Firstly, we explored the adsorption structure and energy and ELF cross section of DDTC on the main minerals in the high-sulfur residue (

Figure 5). When adsorption of DDTC appeared on sulfur, the distance between their respective inner sulfur atoms was between 3.47Å-4.75Å with the adsorption energy of -6.65 kJ/mol (

Figure 5a). This meant a physical adsorption with a weak bond of DDTC onto the sulfur surface.

For the DDTC adsorption on pyrite, the sulfur atoms S1 and S2 in the polar group of DDTC prompted a shift of the iron atoms Fe1 and Fe2 on the pyrite from an original coordination unsaturated structure to a saturated six-coordination structure (

Figure 5b). This decreased the surface energy on the pyrite. The adsorption energy of DDTC on the pyrite was calculated at -195.64 kJ/mol, which meant a strong adsorption on the pyrite.

Figure 5e showed that the ELF value between the sulfur atom and the iron atom was close to 1. This indicated the existence of localization electrons between them, which formed a chemisorption.

The DDTC adsorption on sphalerite was similar to on the pyrite (

Figure 5c). The adsorption energy of DDTC on the sphalerite was calculated at -42.57 kJ/mol.

Figure 5f also showed chemisorption characteristics of DDTC on the sphalerite.

For DDTC adsorption on the lead sulfate, S1 and S2 on DDTC were adsorbed at lead atoms with an adsorption energy of -81.05 kJ/mol (

Figure 5d). This indicated a strong adsorption of DDTC on the lead sulfate. Meanwhile,

Figure 5g indicated that DDTC was chemisorbed on the surface of lead sulfate.

3.1.2. Adsorption behavior of H2O

Next, we investigated the adsorption structure and energy and ELF cross section of H

2O on the main mineral phase of the high-sulfur residue (

Figure 6). For adsorption of H

2O on the sulfur, the distances of the oxygen atom O and hydrogen atoms H1 and H2 with the sulfur atom S were relatively far (

Figure 6a). This caused a physical adsorption with a low adsorption energy of -8.49 kJ/mol.

For H

2O adsorption on the sphalerite, oxygen atoms adsorbed at zinc atoms, while hydrogen atoms adsorbed at sulfur atoms (

Figure 6b). The adsorption energy was calculated at -65.05 kJ/mol, which was close to the -65.5 kJ/mol calculated by Sit

25 using Quantum-ESPRESSO under PBE pseudopotential.

Figure 6e showed a high ELF value between oxygen atoms and zinc atoms, indicating a chemisorption of H

2O on the sphalerite. On the other hand, the ELF value between the hydrogen atoms and the sulfur atoms was nearly 0, which indicated that they were electrostatic interacted.

For H

2O adsorption on the pyrite, the oxygen atoms adsorbed at the iron atoms, while the hydrogen atoms adsorbed at the sulfur atoms (

Figure 6c). The adsorption energy was calculated at -62.71 kJ/mol, which was close to the adsorption energy on the sphalerite. This indicated a close adsorption ability of H

2O on the sphalerite and pyrite. This adsorption energy was also close to the -62 kJ/mol obtained by Pollet

26 using ab initio molecular dynamics simulations. There was a high ELF value between oxygen atoms and iron atoms (

Figure 6f), indicating that the adsorption of H

2O on the surface of pyrite was chemisorption. At the same time, the hydrogen atoms in H

2O and the sulfur atoms on pyrite were mutually electrostatic interacted.

For H

2O adsorption on the lead sulfate, oxygen atoms adsorbed at lead atoms, while hydrogen atoms absorbed at oxygen atoms (

Figure 6d). The adsorption energy was as high as -112.12 kJ/mol, which suggested a strong adsorption on the lead sulfate. This was confirmed by

Figure 6g result that the H

2O was chemisorbed on the lead sulfate.

3.1.3. Co-adsorption model of DDTC and H2O

After understanding the adsorption behavior of DDTC and H2O on the sulfur, pyrite, sphalerite and lead sulfate, we further constructed their co-adsorption model, to gain more insights into the interfacial adsorption mechanism. On the sulfur, both the H2O and DDTC had weak adsorption ability, indicating that the sulfur was hydrophobic and could not be well trapped by the DDTC; On the sphalerite and lead sulfate surfaces, the H2O preferentially adsorbed at metal atoms than the DDTC; However, on the pyrite, the DDTC preferred adsorbing than the H2O. Overall, the co-adsorption models of DDTC and H2O on the sulfur, sphalerite, pyrite and lead sulfate were established, which depended on their mutual adsorption ability gap.

The H

2O had different degrees of influence on the adsorption of DDTC on different carriers (

Figure 7). For instance, on the sulfur, the H

2O influenced little on the adsorption structure and energy of DDTC (decreasing from -6.65 to -6.13 kJ/mol). On the sphalerite, the adsorption energy of DDTC was significantly weakened from -42.57 kJ/mol to -8.08 kJ/mol and its adsorption mode transformed from chemisorption to physical adsorption (

Figure 7b). This was due to the adsorption of H

2O around the zinc atoms of sphalerite. On the pyrite, the adsorption energy of DDTC changed slightly from -195.64 to -191.46 kJ/mol with consistent chemisorption (

Figure 7c). This indicated little impact of H

2O. On the surface of lead sulfate, H

2O were preferentially adsorbed. DDTC were adsorbed on the surface of lead sulfate by electrostatic interaction with H

2O, which was a kind of indirect adsorption (

Figure 7d). The adsorption energy of DDTC significantly weakened from -81.05 kJ/mol to -18.53 kJ/mol.

Based on the above, the DDTC adsorption on the sulfur, sphalerite and lead sulfate was weak with physical bonding, while its adsorption on the pyrite was strong with chemical bonding.

3.2. Model Validation

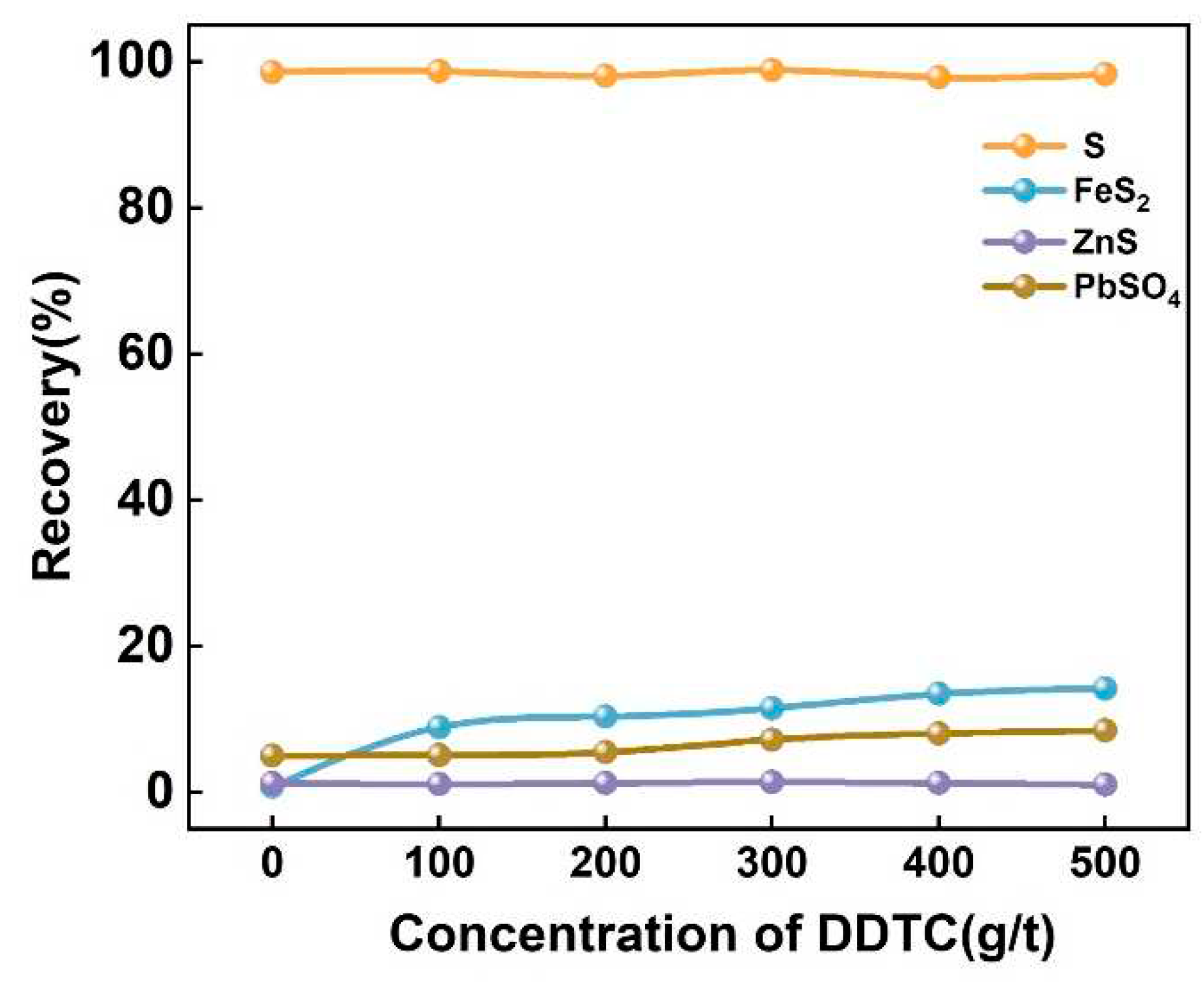

The pure minerals flotation was performed to validate the co-adsorption model (

Figure 8). At a DDTC concentration of 0 g/t, sulfur had an almost 100% recovery, indicating an excellent flotation performance, while sphalerite, pyrite, and lead sulfate had low recoveries, indicating that these minerals had well hydrophilic properties. With increasing DDTC concentration from 0 to 500 g/L, the recovery of sulfur, sphalerite and lead sulfate changed little, while the recovery of pyrite increased significantly. This indicated that the DDTC had weak ability to trap sulfur, sphalerite, and lead sulfate, but had desired ability to trap pyrite. This result was consistent with the result of co-adsorption model: the interaction of DDTC on the sulfur, sphalerite and lead sulfate was weak adsorption, while the interaction of DDTC on the pyrite was strong adsorption.

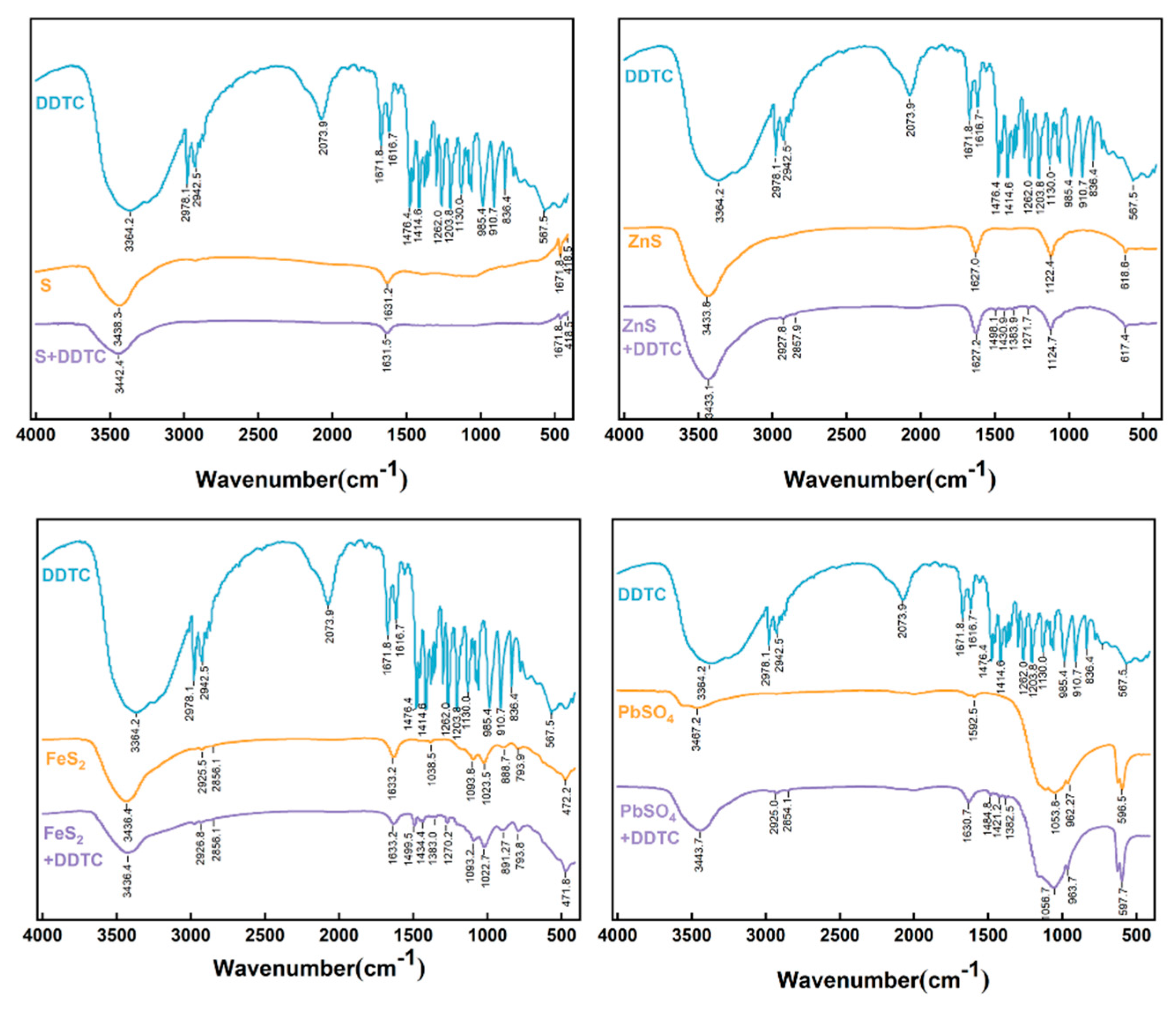

The FT-IR results of DDTC adsorbed on the main minerals further validated the co-adsorption model (

Figure 9). The peaks around 3000 cm

-1 in DDTC were C-H vibrational peaks, and the peaks at 1262.0 cm

-1, 1414.6 cm

-1, and 1476.4 cm

-1 were associated with C-N vibrations. The FT-IR spectra of DDTC were nearly unchanged before and after its adsorption on the sulfur. This indicated almost no occurrence of DDTC adsorption on the sulfur; the weak peaks in the FTIR spectra of sphalerite and lead sulfate after DDTC treatment indicated that the DDTC was physically adsorbed on them. The FT-IR spectra of pyrite showed absorption peaks of C-N vibrations and a new peak at 1499.5 cm

-1 after the DDTC treatment, which indicated its chemisorption on the pyrite. Overall, the FT-IR result agreed well with the co-adsorption model.

3.3. Practical bench-scale operation of high-sulfur residue flotation

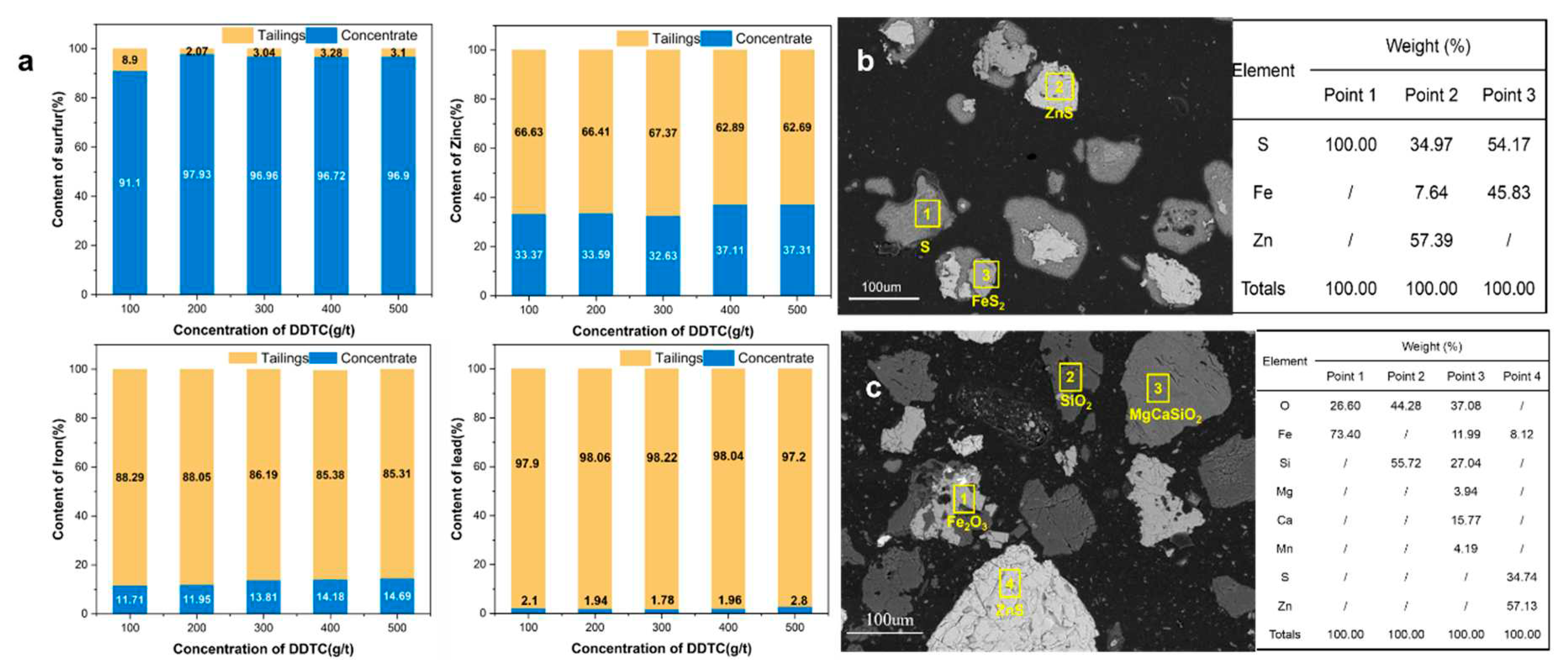

The flotation on high-sulfur residue was explored using different concentrations of DDTC to examine its practical operation. The distribution of elements sulfur, iron, zinc and lead into the concentrate and tailings after flotation was shown in

Figure 10. The element sulfur was mainly distributed into the concentrate, while the elements of iron, zinc, and lead were mainly distributed into the tailings (

Figure 10a). With increasing DDTC concentration from 100 to 500g/t, the contents of sulfur, iron and zinc in the concentrate increased slightly, but lead content almost remained unchanged. This result was different from that obtained from the pure mineral flotation. To explain the difference, the mineral fugacity pattern in the high-sulfur residue flotation was further analyzed.

Figure 10b showed the mineral fugacity pattern in the flotation concentrate, which indicated that the concentrate was mainly composed of sulfur and sulfide. Sulfur, sphalerite and pyrite were embedded with each other and were difficult to be separated.

Figure 10c showed the mineral fugacity pattern in the flotation tailings. The tailings were composed of silica, silicate and oxide, and some sulfide. Some iron oxides were closely embedded with quartz. The addition of DDTC increased the hydrophobicity of pyrite and facilitated its floatation. Part of the sulfur and ZnS, which embedded and wrapped the pyrite, were also floated together. This increased the contents of sulfur and zinc in the concentrate. Overall, our model predictions and practical mineral phase analysis synergistically revealed the elements assignment and the flotation performance.

4. Conclusions

This work successfully revealed the interfacial adsorption mechanism of DDTC on the four mineral phases in the high-sulfur residue flotation, using DFT calculation, interfacial characterization and on-line test. The adsorption behavior results of DDTC and H2O obtained by DFT calculation helped us construct the co-adsorption model of H2O and DDTC on the sulfur, pyrite, sphalerite and lead sulfate. On the sulfur, both the H2O and DDTC had weak adsorption ability, indicating that the sulfur was hydrophobic and could not be well trapped by the DDTC; On the sphalerite and lead sulfate surfaces, the H2O preferentially adsorbed at metal atoms than the DDTC; However, on the pyrite, the DDTC preferred adsorbing than the H2O.

The pure mineral flotation operation and FT-IR results validated the co-adsorption model. The pure mineral flotation result indicated the order of DDTC collection ability: pyrite > sphalerite > sphalerite > sulfur. The FT-IR results demonstrated that the DDTC was chemisorbed on the pyrite, while physically adsorbed on the sulfur, lead sulfate and sphalerite. Practical bench-scale operation result indicated that the contents of pyrite, sulfur and ZnS in the concentrate synergistically increased with increasing DDTC concentration. This was different from that obtained from the pure mineral flotation. This is because the addition of DDTC increased the hydrophobicity and floatability of pyrite. Parts of the sulfur and ZnS, which embedded and wrapped the pyrite, were also floated together. Our model predictions and practical mineral phase analysis synergistically revealed the elements assignment and the flotation performance in the practical operation. To authors’ knowledge, the co-adsorption model was first established, which would provide theoretical foundation for the practical operation of high-sulfur residue flotation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (No.2018YFC1902005) and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (No.2021RC2002). This work was carried out in part using hardware and software provided by the High Performance Computing Centers of Central South University.

References

- Liu, G.Q.; Zhang, B.S.; Dong, Z.L.; Zhang, F.; Wan, F.; Jiang, T.; Xu, B. Flotation Performance, Structure-Activity Relationship and Adsorption Mechanism of O-Isopropyl-N-Ethyl Thionocarbamate Collector for Elemental Sulfur in a High-Sulfur Residue. Metals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Niu, L.; Jing, T.; Zhang, T.-a. Separation and purification of elemental sulfur from sphalerite concentrate direct leaching residue by liquid paraffin. Hydrometallurgy 2019, 186, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liu, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, C. Mineralogical and morphological factors affecting the separation of copper and arsenic in flash copper smelting slag flotation beneficiation process. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 401, 123293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorjani, E.; Ghahreman, A. Challenges with elemental sulfur removal during the leaching of copper and zinc sulfides, and from the residues; a review. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 171, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfyard, J.E.; Hawboldt, K. Separation of elemental sulfur from hydrometallurgical residue: A review. Hydrometallurgy 2011, 109, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-y.; Cai, X.-l.; Zhang, Z.-b.; Zhang, L.-b.; Wang, S.-x.; Peng, J.-h. Separation and enrichment of elemental sulfur and mercury from hydrometallurgical zinc residue using sodium sulfide. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 2015, 25, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, J.; Wu, S.; Yao, X.; Li, L. Separation of elemental sulfur from zinc concentrate direct leaching residue by vacuum distillation. Separation and Purification Technology 2014, 138, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yang, X.; Zhong, H. Molecular design of flotation collectors: A recent progress. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2017, 246, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.A.; Garrot, T.G.; Pereira, A.M.; Correia, J.C.G. Historical perspective and bibliometric analysis of molecular modeling applied in mineral flotation systems. Minerals Engineering 2021, 170, 107062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngobeni, W.A.; Hangone, G. The effect of using sodium di-methyl-dithiocarbamate as a co-collector with xanthates in the froth flotation of pentlandite containing ore from Nkomati mine in South Africa. Minerals Engineering 2013, 54, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wu, M.; Liu, R.; Sun, W. A review on the electrochemistry of galena flotation. Minerals Engineering 2020, 150, 106272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Ruan, R.; Xia, L.; Li, L.; Sun, H.; Jia, Y.; Tan, Q. Correlation of Surface Adsorption and Oxidation with a Floatability Difference of Galena and Pyrite in High-Alkaline Lime Systems. Langmuir 2018, 34, 2716–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, Y.H.; Xu, J.; Chen, T.J. FTIR spectroscopic study of electrochemical flotation of jamesonite-diethyldithiocarbamate system. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 2006, 16, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.Y.; Zhang, J.J.; Liu, Z.R.; Chen, J.H. Selective enhancement of jamesonite flotation using Aerophine 3418A/ DDTC mixture. Minerals Engineering 2023, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.X.; Wu, B.Z.; Deng, J.S.; Sun, X.H.; Hu, M.Z.; Cai, J.Z.; Zheng, C. The effect of collectors on froth stability of frother: Atomic-scale study by experiments and molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2022, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.M.; Gao, J.D.; Khoso, S.A.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.L.; Ge, P.; Tian, M.J.; Sun, W. A reagent scheme for galena/sphalerite flotation separation: Insights from first-principles calculations. Minerals Engineering 2021, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.P.; Jia, Y.; Wang, S.; Ma, X.; Cao, Z.F.; Zhong, H. Novel Sodium O-Benzythioethyl Xanthate Surfactant: Synthesis, DFT Calculation and Adsorption Mechanism on Chalcopyrite Surface. Langmuir 2019, 35, 15106–15113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, J.; Spicher, S.; Bursch, M.; Grimme, S. Quickstart guide to model structures and interactions of artificial molecular muscles with efficient computational methods. Chemical Communications 2021, 58, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracht, P.; Bohle, F.; Grimme, S. Automated exploration of the low-energy chemical space with fast quantum chemical methods. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2020, 22, 7169–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F.W. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhonto, P.P.; Zhang, X.R.; Lu, L.; Xiong, W.; Zhu, Y.G.; Han, L.; Ngoepe, P.E. Adsorption mechanisms and effects of thiocarbamate collectors in the separation of chalcopyrite from pyrite minerals: DFT and experimental studies. Minerals Engineering 2022, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahraei, A.A.; Larachi, F. How Do Surface Defects Change Local Wettability of the Hydrophilic ZnS Surface? Insights into Sphalerite Flotation from Density Functional Theory Calculations. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2021, 125, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F.W. Meaning and Functional Form of the Electron Localization Function. Acta Physico-Chimica Sinica 2011, 27, 2786–2792. [Google Scholar]

- Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. Journal of Applied Crystallography 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, P.H.L.; Cohen, M.H.; Selloni, A. Interaction of Oxygen and Water with the (100) Surface of Pyrite: Mechanism of Sulfur Oxidation. Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2012, 3, 2409–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollet, R.; Boehme, C.; Marx, D. Ab initio simulations of desorption and reactivity of glycine at a water-pyrite interface at “iron-sulfur world” prebiotic conditions. Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres 2006, 36, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).