Submitted:

01 April 2023

Posted:

07 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Measuring foot and ankle volume by water displacement or water volumetry remains the reference method [20,21,22]. Some authors use inverse water volumetry [23], which consists in placing a dry foot in a volumeter that has been filled up to a predetermined level. Foot volume is determined either by assessing the volume of water that overflows from the foot volumeter, or by the volume of water that needs to be added after retracting the foot from the volumeter to return to initial water levels (“inverse” method). The advantages of water volumetry are practicability and reproducibility [22]. However, in daily clinical practice, managing water volumes, maintaining water hygiene, and time taken may represent significant issues. Moreover, immersing a limb presenting with any kind of skin lesion in water is not advised.

- In daily clinical practice, perimetric (non-volumetric) measurements constitute the most frequently adopted method, although reproducibility and inter-rater reliability are low [24]. To improve reproducibility, several studies have shown the interest of figure-of-eight methods [25], or the added value of professional experience in raters [26]. Using tape measure methods, some studies have attempted to calculate the volume of a limb based on mathematical methods, without, however, paying attention to distal volumes (fingers or toes) [26], and with 8 to 12% error margins when compared to the reference method [27]. For foot/ankle measurements, some surveys have proposed mathematical formulas to determine volume from perimetric measurements performed on particular cutaneous points of reference [28].

- Several 3D scan measurement methods have been described in previous surveys. Most of them were used for knee joint measurements. Of note, knee joint 3D morphology is less problematic to assess than that of the foot and toes [29,30]. Indeed, the foot as well as the hand, because of the difficulties to define precisely the volumes of the fingers and toes, are more difficult to assess [31]. These techniques are associated with high reproducibility. However, they have often been assessed with reference to tape measure methods [32], much more rarely to the reference method (water volumetry) [27]. Tape measures are non-weight-bearing measurements. Measuring foot and ankle volume, without the application of weight, and only on limb segments, excluding the foot and toes, is potentially biased [33].

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1.

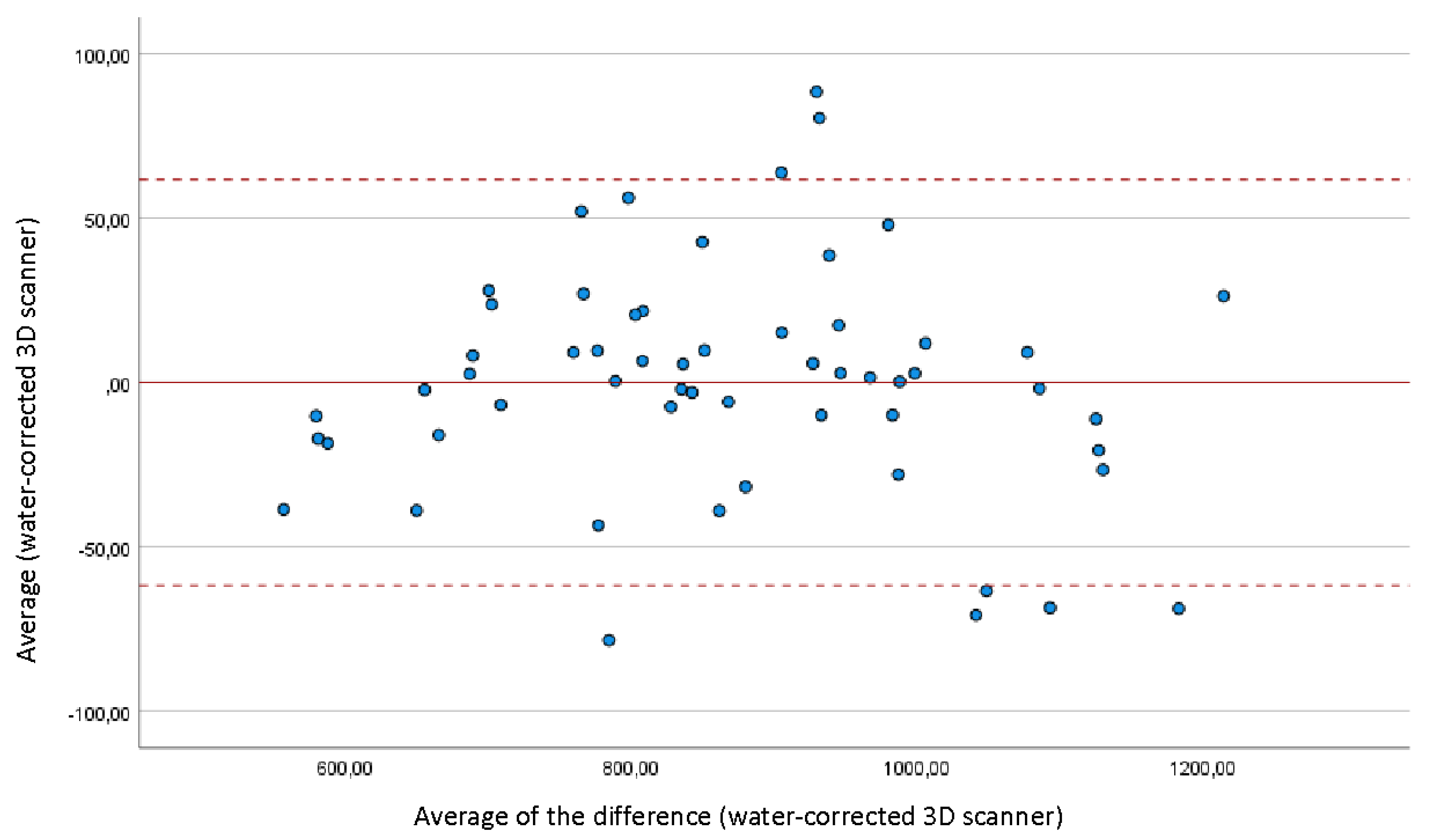

- Mean foot volume when measured by 3D scanner was 869.7+/-165.1cm3, versus 867.9+/-155.4cm3 when using water-displacement volumetry (p <10-5). Concordance of gross measurements, measured by Lin’s CCC was 0.93, indicative of an excellent correlation between the two techniques. No deviation from normalcy was shown for the difference in measurement between water volume and scanner volume (p=0.2), which allowed the application of the Bland and Altman method (Table 2).

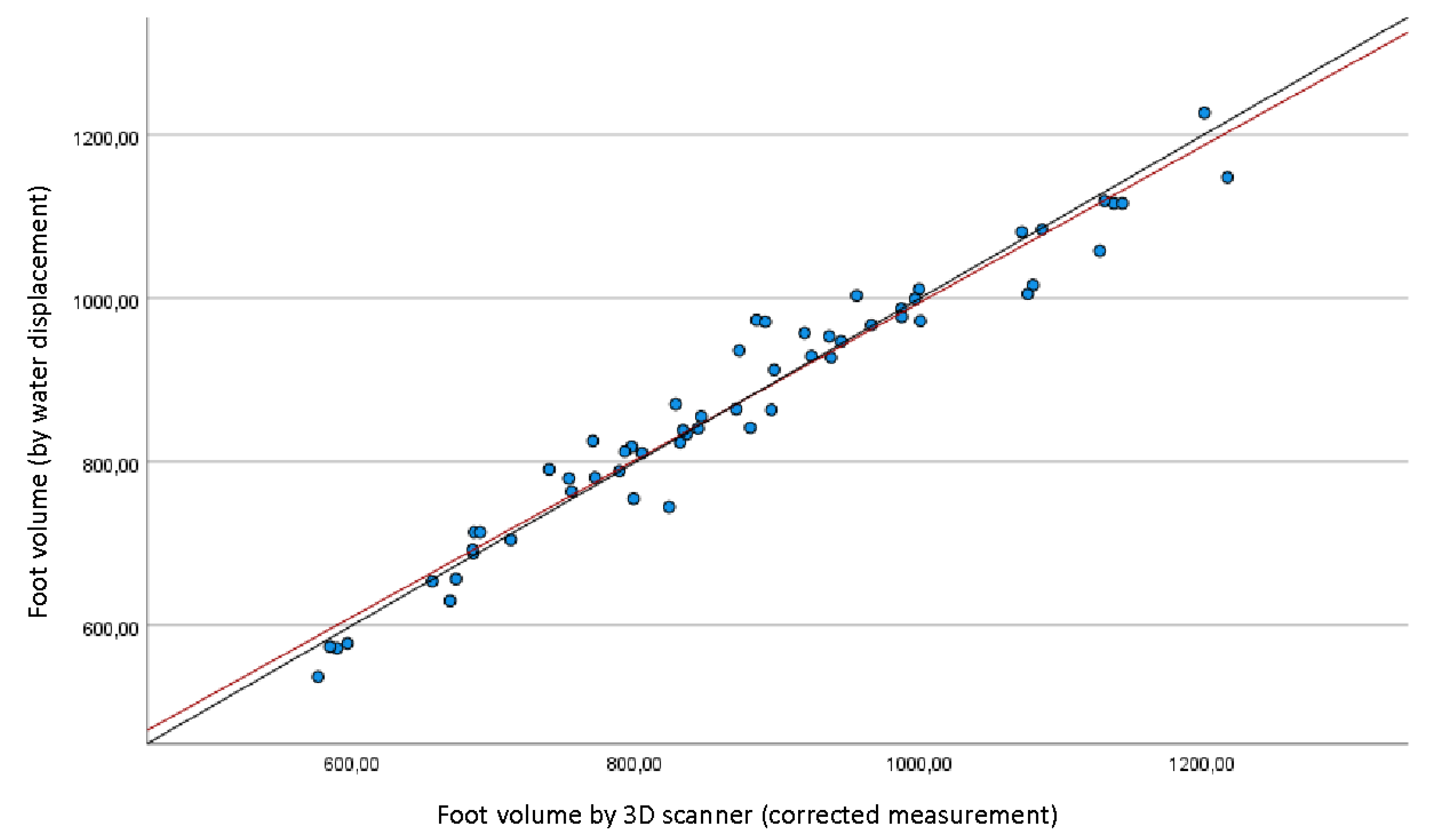

- Measurement discrepancy was 47.8 cm3, showing underestimation when using 3D scanner versus water volumetry. After correcting results yielded by the 3D scanner method for this value (“corrected 3D scanner measurement”), an excellent concordance was demonstrated between the two techniques (LIN’s CCC= 0.98, residual bias = -0.027 cm3 +/- 35.10 cm3), as shown in Table 3.

- Mean examination time was 4.2 +/-1,7 min when using the 3D optical scanner versus 11.1 +/-2,9 min when using the water volumeter. This was a statistically significant difference (p<10-4), as shown in Table 4.

3.2.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stolldorf DP, Dietrich MS, Ridner SH. Symptom Frequency, Intensity, and Distress in Patients with Lower Limb Lymphedema. Lymphat Res Biol. 2016;14: 78–87. [CrossRef]

- Ridner, SH. The psycho-social impact of lymphedema. Lymphat Res Biol. 2009;7: 109–112. [CrossRef]

- Brijker F, Heijdra YF, Van Den Elshout FJ, Bosch FH, Folgering HT. Volumetric measurements of peripheral oedema in clinical conditions. Clin Physiol. 2000;20(1):56-61. [CrossRef]

- Moholkar K, Fenelon G. Diurnal variations in volume of the foot and ankle. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2001;40(5):302-304. [CrossRef]

- Nouraei H, Nouraei H, Rabkin SW. Comparison of Unsupervised Machine Learning Approaches for Cluster Analysis to Define Subgroups of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction with Different Outcomes. Bioengineering. 2022; 9(4):175. [CrossRef]

- Mastick J, Smoot BJ, Paul SM, et al. Assessment of Arm Volume Using a Tape Measure Versus a 3D Optical Scanner in Survivors with Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema. Lymphat Res Biol. 2022;20(1):39-47. [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidis, C.; Lali, F.; Greco, K.V.; García-Gareta, E. Chronic Leg Ulcers: Are Tissue Engineering and Biomaterials Science the Solution? Bioengineering 2021, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacEwan, M.; Jeng, L.; Kovács, T.; Sallade, E. Clinical Application of Bioresorbable, Synthetic, Electrospun Matrix in Wound Healing. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrault, D.P.; Sharma, A.; Kim, J.F.; Gurtner, G.C.; Wan, D.C. Surgical Applications of Materials Engineered with Antimicrobial Properties. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva R, Veloso A, Alves N, Fernandes C, Morouço P. A Review of Additive Manufacturing Studies for Producing Customized Ankle-Foot Orthoses. Bioengineering (Basel). 2022;9(6):249. [CrossRef]

- Yu H-B, Li J, Zhang R, Hao W-Y, Lin J-Z, Tai W-H. Effects of Jump-Rope-Specific Footwear Selection on Lower Extremity Biomechanics. Bioengineering. 2022; 9(4):135. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhao, L.; Kong, Q.; Yu, G.; Yu, H.; Li, J.; Tai, W.-H. The Bionic High-Cushioning Midsole of Shoes Inspired by Functional Characteristics of Ostrich Foot. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, R.; Veloso, A.; Alves, N.; Fernandes, C.; Morouço, P. Amerinatanzi, A. ; Zamanian, H.; Shayesteh Moghaddam, N.; Jahadakbar, A.; Elahinia, M. Application of the Superelastic NiTi Spring in Ankle Foot Orthosis (AFO) to Create Normal Ankle Joint Behavior. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Wang, C.-S.; Lin, K.-W.; Chien, M.-J.; Wei, S.-H.; Chen, C.-S. Biomechanical Analysis of the FlatFoot with Different 3D-Printed Insoles on the Lower Extremities. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalevée M, Barbachan Mansur NS, Lee HY, Ehret A, Tazegul T, d e Carvalho KAM, Bluman E, de Cesar Netto C. A comparison between the Bluman et al. and the progressive collapsing foot deformity classifications for flatfeet assessment. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2023 Mar;143(3):1331-1339.

- Lalevée M, Barbachan Mansur NS, Rojas EO, Lee HY, Ahrenholz SJ, Dibbern KN, Lintz F, de Cesar Netto C. Prevalence and pattern of lateral impingements in the progressive collapsing foot deformity. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2023 Jan;143(1):161-168.

- Lalevée M, Dibbern K, Barbachan Mansur NS, et al. Impact of First Metatarsal Hyperpronation on First Ray Alignment: A Study in Cadavers. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2022;480(10):2029-2040. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.-T.; Liu, L.-W.; Chen, C.-J.; Chen, Z.-R. The Soft Prefabricated Orthopedic Insole Decreases Plantar Pressure during Uphill Walking with Heavy Load Carriage. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Cen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Bíró, I.; Ji, Y.; Gu, Y. Development and Validation of a Subject-Specific Coupled Model for Foot and Sports Shoe Complex: A Pilot Computational Study. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henschke N, Boland RA, Adams RD. Responsiveness of two methods for measuring foot and ankle volume. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27: 826–832. [CrossRef]

- Brijker F, Heijdra YF, Van Den Elshout FJ, Bosch FH, Folgering HT. Volumetric measurements of peripheral oedema in clinical conditions. Clin Physiol Oxf Engl. 2000;20: 56–61. [CrossRef]

- Brodovicz KG, McNaughton K, Uemura N, Meininger G, Girman CJ, Yale SH. Reliability and feasibility of methods to quantitatively assess peripheral edema. Clin Med Res. 2009;7: 21–31. [CrossRef]

- Damstra RJ, Glazenburg EJ, Hop WCJ. Validation of the inverse water volumetry method: A new gold standard for arm volume measurements. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99: 267–273. [CrossRef]

- Deltombe T, Jamart J, Recloux S, Legrand C, Vandenbroeck N, Theys S, et al. Reliability and limits of agreement of circumferential, water displacement, and optoelectronic volumetry in the measurement of upper limb lymphedema. Lymphology. 2007;40: 26–34.

- Esterson, PS. Measurement of ankle joint swelling using a figure of 8*. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1979;1: 51–52. [CrossRef]

- Sharkey AR, King SW, Kuo RY, Bickerton SB, Ramsden AJ, Furniss D. Measuring Limb Volume: Accuracy and Reliability of Tape Measurement Versus Perometer Measurement. Lymphat Res Biol. 2018;16: 182–186. [CrossRef]

- Tierney S, Aslam M, Rennie K, Grace P. Infrared optoelectronic volumetry, the ideal way to measure limb volume. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg Off J Eur Soc Vasc Surg. 1996;12: 412–417. [CrossRef]

- Mayrovitz HN, Sims N, Litwin B, Pfister S. Foot volume estimates based on a geometric algorithm in comparison to water displacement. Lymphology. 2005;38: 20–27.

- Pichonnaz C, Bassin J-P, Lécureux E, Currat D, Jolles BM. Bioimpedance spectroscopy for swelling evaluation following total knee arthroplasty: a validation study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16: 100. [CrossRef]

- Man IOW, Markland KL, Morrissey MC. The validity and reliability of the Perometer in evaluating human knee volume. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2004;24: 352–358. [CrossRef]

- Esposito, D.; Savino, S.; Andreozzi, E.; Cosenza, C.; Niola, V.; Bifulco, P. The “Federica” Hand. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanton AW, Northfield JW, Holroyd B, Mortimer PS, Levick JR. Validation of an optoelectronic limb volumeter (Perometer). Lymphology. 1997;30: 77–97.

- Gao, L.; Lu, Z.; Liang, M.; Baker, J.S.; Gu, Y. Influence of Different Load Conditions on Lower Extremity Biomechanics during the Lunge Squat in Novice Men. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, C.J.; Gupta, K.; Wang, J.; Wong, A.K. Lymphatic Tissue Bioengineering for the Treatment of Postsurgical Lymphedema. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devoogdt N, Cavaggion C, Van der Gucht E, Dams L, De Groef A, Meeus M, et al. Reliability, Validity, and Feasibility of Water Displacement Method, Figure-of-Eight Method, and Circumference Measurements in Determination of Ankle and Foot Edema. Lymphat Res Biol. 2019;17: 531–536. [CrossRef]

- Istook, C. 3D scanning systems with application to the apparel industry. J Fash Market Manage. 2000: 120–132.

- Zhao J, Xiong S, Bu Y, Goonetilleke R. Computerized girth determination for custom footwear manufacture. Comput Ind Eng. 2008: 359–373.

- Cheng F-T, Perng D-B. A systematic approach for developing a foot size information system for shoe last design. Int J Ind Ergon. 2000;25: 171–185. [CrossRef]

- Rogati G, Leardini A, Ortolani M, Caravaggi P. Validation of a novel Kinect-based device for 3D scanning of the foot plantar surface in weight-bearing. J Foot Ankle Res. 2019;12: 46. [CrossRef]

- Labs KH, Tschoepl M, Gamba G, Aschwanden M, Jaeger KA. The reliability of leg circumference assessment: a comparison of spring tape measurements and optoelectronic volumetry. Vasc Med Lond Engl. 2000;5: 69–74. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann B, Konopka K, Fischer D-C, Kundt G, Martin H, Mittlmeier T. 3D optical scanning as an objective and reliable tool for volumetry of the foot and ankle region. Foot Ankle Surg Off J Eur Soc Foot Ankle Surg. 2022;28: 200–204. [CrossRef]

- Telfer S, Woodburn J. The use of 3D surface scanning for the measurement and assessment of the human foot. J Foot Ankle Res. 2010;3: 19. [CrossRef]

- Laštovička O, Cuberek R, Janura M, Klein T. Evaluation of the Usability of the Tiger Full-Foot Three-Dimensional Scanner for the Measurements of Basic Foot Dimensions in Clinical Practice. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2022;112: 20–019. [CrossRef]

- Jurca A, Žabkar J, Džeroski S. Analysis of 1.2 million foot scans from North America, Europe and Asia. Sci Rep. 2019;9: 19155. [CrossRef]

- Razeghi M, Batt ME. Foot type classification: a critical review of current methods. Gait Posture. 2002;15: 282–291. [CrossRef]

- De Vrieze T, Gebruers N, Tjalma WA, Nevelsteen I, Thomis S, De Groef A, et al. What is the best method to determine excessive arm volume in patients with breast cancer-related lymphoedema in clinical practice? Reliability, time efficiency and clinical feasibility of five different methods. Clin Rehabil. 2019;33: 1221–1232. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Shang Y, Sun H. Improved Calculation Method for Siphon Drainage with Extended Horizontal Sections. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(19):9660. [CrossRef]

- D Abduraimova and M Ismoilova 2020 IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 614 012122. [CrossRef]

- Sebbagh, P.; Hirt-Burri, N.; Scaletta, C.; Abdel-Sayed, P.; Raffoul, W.; Gremeaux, V.; Laurent, A.; Applegate, L.A.; Gremion, G. Process Optimization and Efficacy Assessment of Standardized PRP for Tendinopathies in Sports Medicine: Retrospective Study of Clinical Files and GMP Manufacturing Records in a Swiss University Hospital. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biscarini, A. Dynamics of Two-Link Musculoskeletal Chains during Fast Movements: Endpoint Force, Axial, and Shear Joint Reaction Forces. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.; Zhang, T.; Yu, R.; Ganderton, C.; Adams, R.; Han, J. Effect of Different Landing Heights and Loads on Ankle Inversion Proprioception during Landing in Individuals with and without Chronic Ankle Instability. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Population | n= 29 |

| Gender (Male/female) | 5/24 |

| Age (years) average +/- standard deviation Minimum age (years) Maximum age (years) |

35.6 +/- 9.5 9 55 |

| Shoe size Européenne size Average +/- standard deviation Minimum Maximum |

38.2 +/- 3.2 30 45 |

| Volume (Cm3) | 3D scanner | Water displacement | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average +/- Standard Deviation | 869.7 +/- 165,1 | 867.89 +/- 155.4 | <10-5 |

| Minimum | 575.9 | 537.3 | |

| Maximum | 1217.3 | 1148.5 | |

| Measurement time (min) | 4.2 +/- 1.7 | 11.1 +/- 2.9 | <10-4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).