1. Introduction

Chronic diseases have become a major health problem in Europe. Around 75% of healthcare expenditure in Europe is spent on the management and treatment of chronic diseases. It is striking that almost two thirds of health expenditure comes from elderly people with multiple chronic diseases [

1,

2].

The projected global population outlook estimates that the population of older people (defined as those aged 65 and over) will increase significantly, from 101 million at the beginning of 2018 to 149 million in 2050 [

3]. During this period, the number of people aged 75-84 in the EU is projected to increase by 60.5%, while the number of people aged 65-74 is expected to increase by 17.6%. While it is expected that by then there will be 9.6% fewer people under 55 living in the EU [

4].

Among the most prominent chronic age-related diseases, stand out Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [

5]. AD is a neurodegenerative pathology that produces cognitive and behavioral changes and is reflected as dementia [

6]. AD are responsible for the largest burden of disease: Alzheimer’s and related disorders affect more than 7 million people in Europe, and this figure is expected to double every 20 years as the population ages [

7,

8]. Currently, caring for people with dementia across Europe costs approximately €130 billion a year [

9].

PD is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disease. Globally, the burden of PD has doubled as a result of the increase in the number of older people. The prevalence of PD is estimated to be 6.2 million people worldwide, although the European Parkinson’s Disease Association (EPDA) suggests that the figure should be higher, at around 10 million people, due to under-diagnosis [

10]. Some studies suggest that this figure could double by 2040 to 12 million [

11]. The estimated annual European cost of Parkinson’s disease is 13.9billion, representing 11.600 per patient [

12].

People with CVD have one or more risk factors, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia. Early detection of disease aggravation and prompt treatment is essential [

13]. CVD represented the 31% of all global deaths in 2016, and it is deemed as the leading cause of premature death (37% of all deaths under the age of 70) and disability in Europe and worldwide [

14].

Complications of chronic diseases can be influenced by several factors, some of which are modifiable and preventable if strategies aimed at improving health habits are promoted among the population [

15]. Lifestyle factors can influence the onset and intensity of chronic diseases [

16,

17,

18]. People who lead a healthy lifestyle, such as eating a balanced diet, exercising regularly, having good sleep habits, avoiding toxic intake, have many health benefits, especially in avoiding complications of chronic diseases [

19,

20]. Providing patients with chronic diseases with a tool to help them manage their self-care may have important individual, clinical and public health implications in view of rapidly increasing trends in the prevalence of multimorbidity.

It is therefore crucial to find new and innovative solutions to improve their Quality of Life (QoL), increase autonomy and promote self-care with the ultimate goal of reducing the burden on European healthcare systems. The TeNDER project [

21] is positioned to address this issue. The project aims to create an integrated care ecosystem for people with chronic diseases, which adapts to their needs through a multi-sensorial system, while preserving privacy and ensuring data protection. The TeNDER project was conducted in four different European countries and involved over 1500 users, including patients, health professionals, social workers, caregivers, and other staff. The project used affect-based micro tools to match clinical and clerical patient information and provide tailored integrated care services to promote wellbeing and health recovery. In addition, interactive communication and social services will strengthen elderly support, extending their autonomy and care supply chain.

One of the key components of the TeNDER project is the Health Recommender Systems (HRS), which played a critical role in personalizing the care experience for patients with chronic diseases. The HRS analyzed patient data and generate personalized recommendations that match the person’s needs. These recommendations were integrated into the mobile app, providing users with real-time updates and information. This helped to improve the overall QoL for patients with chronic diseases, while ensuring that they receive the care and support they need.

In this article, we provide a comprehensive overview of the HRS that has been developed for the TeNDER project. We will discuss the process used to make the data useful for defining personalization, generating recommendations, and sending the information to the mobile app. We will also provide an evaluation of the HRS, highlighting its performance and potential for improvement. By doing so, we hope to contribute to the development of innovative solutions for chronic diseases and to improve the QoL for those affected by these conditions.

This paper is structured as follows: the Introduction in

Section 1 provides an overview of the topic, the research question and the state of the art of related works; the Materials and Methods in

Section 2 describes the study design and the architecture; the Results in

Section 3 presents the findings of the study, and the Conclusions in

Section 4 summarizes the main findings and their implications for practice and future research.

1.1. Literature Review

The background of RS in general topics can provide an overview of the field and inform about the current research state and future directions. In [

22], it is presented a comprehensive study of the various applications of RS for general purposes and their algorithmic analysis. It frames a taxonomy of the components required for developing an effective Recommender System and evaluates the datasets, simulation platforms, and performance metrics used in different contributions. Going further, [

23], provides a study of more than 1000 research papers on RS published between 2011 and the first quarter of 2017. It spots the research trend in the field and identifies future directions for research.

Finally, [

24], presents an overview of the field of RS and describes the present generation of recommendation methods. The authors describe various limitations of recommendation methods and their advantages. They explain that RS are a subset of information filtering systems and provide suggestions to users according to their needs, widely used by popular e-commerce sites to recommend news, music, research articles, books, and product items.

Focusing on health topic, HRSs have the potential to support individuals in making informed decisions about their health by providing personalized recommendations based on observed data. These systems have been developed and studied in a variety of contexts, including wearable devices, electronic health records, and other data sources. These systems offer a rich source of data for HRSs.

They have gained increasing attention as a means of supporting individuals in making informed decisions about their health and well-being [

25,

26,

27]. Some systems use machine learning algorithms to analyze data collected from various sources, such as wearable devices and electronic health records, and provide personalized recommendations to users based on their individual characteristics and needs. Sensorial ecosystems, which consist of a network of interconnected devices that continuously monitor and collect data about an individual’s health, offer a rich source of data for HRSs [

28,

29,

30].

A review of the existing literature on HRSs reveals a number of key challenges and limitations [

31,

32]. One of the main issues is the quality and reliability of the data used to generate recommendations. Inaccurate or incomplete data can lead to inappropriate or irrelevant recommendations, which may negatively impact user acceptance and adherence. Another challenge is the need for personalization, as different individuals have different health needs and preferences. Developing algorithms that can effectively tailor recommendations to individual characteristics and needs is a key challenge in the field.

Despite these challenges, previous research has demonstrated the potential benefits of using these systems in terms of improving health outcomes. For example, some works as [

33] have reviewed the current landscape of Recommender System research and identified trends and future directions in this field.

In [

34] examined the potential of HRSs to support and enhance computer-tailored digital health interventions, identifying their effects on efficiency, effectiveness, trustworthiness, and enjoyment of digital health programs. This paper [

35] discusses the use of artificial intelligence in the development of RS to improve prediction accuracy. It mentions the specific techniques and approaches used, such as fuzzy techniques, transfer learning, and neural networks.

Sensorial ecosystems typically generate large volumes of sensitive personal data, which must be carefully protected to ensure compliance with privacy regulations and to prevent unauthorized access or misuse. Another challenge is to ensure compatibility and integration among these systems. This work [

36] have conducted a thorough analysis of compatibility, security and privacy issues in the context of IoT-based health care including security requirements, threat models, and attack taxonomies from the health care perspective.

Finally, in the context of sensorial ecosystems, there is a study by [

37], which discusses the use of classification methods for proactive monitoring of patients and the recommendation of personalized wearable devices. In this other study [

38], they aim to fill this research gap by evaluating the effectiveness and impact of a wearable fitness tracker as part of a greater healthcare ecosystem for driving user behaviour from the perspective of value-co-creation.

In summary, the existing literature on HRSs suggests that these systems have the potential to support individuals in managing their health and improving their overall well-being. However, further research is needed to address the challenges and limitations of these systems in real-world settings, applied to patients with chronic diseases. Specially, this work applies to find evidences on the positive effects by HRS, in contrast to the work by [

39], where they did not found enough evidences for the positive effects of HRSs in terms of cost-effectiveness and patient health outcomes.

1.2. Research question and objectives

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the effectiveness and usability of a HRS for improving the QoL of chronic patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals. To achieve this objective, the study is designed to address the following specific research objectives:

To study the effectiveness of the HRS in increasing adherence to self-care.

To study the usability of the tool from the perspective of chronic patients, carers and healthcare professionals.

To study satisfaction with the tool from the perspective of chronic patients, carers and healthcare professionals.

By pursuing these research objectives, we aim to provide valuable insights into the potential benefits and challenges of implementing a HRS-based technological system in the management and treatment of chronic diseases. The findings of this study could inform the development of future interventions and strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

This section presents the reseach methodology applied, including the population sample and protocols design. Additionally, the developed HRS is explained in the context of the TeNDER ecosystem. It includes essential information regarding the technical and clinical aspects of the study.

2.1. TeNDER sensorial ecosystem

The large-scale TeNDER project has been piloted in 4 European countries with a sample of 687 patients with chronic diseases. It involved piloting a sensory ecosystem designed to provide a more complete and accurate picture of patient health and well-being by capturing data from a variety of sources. The data collected is processed and analysed using advanced techniques to provide healthcare experts and patients with actionable information to improve their health status.

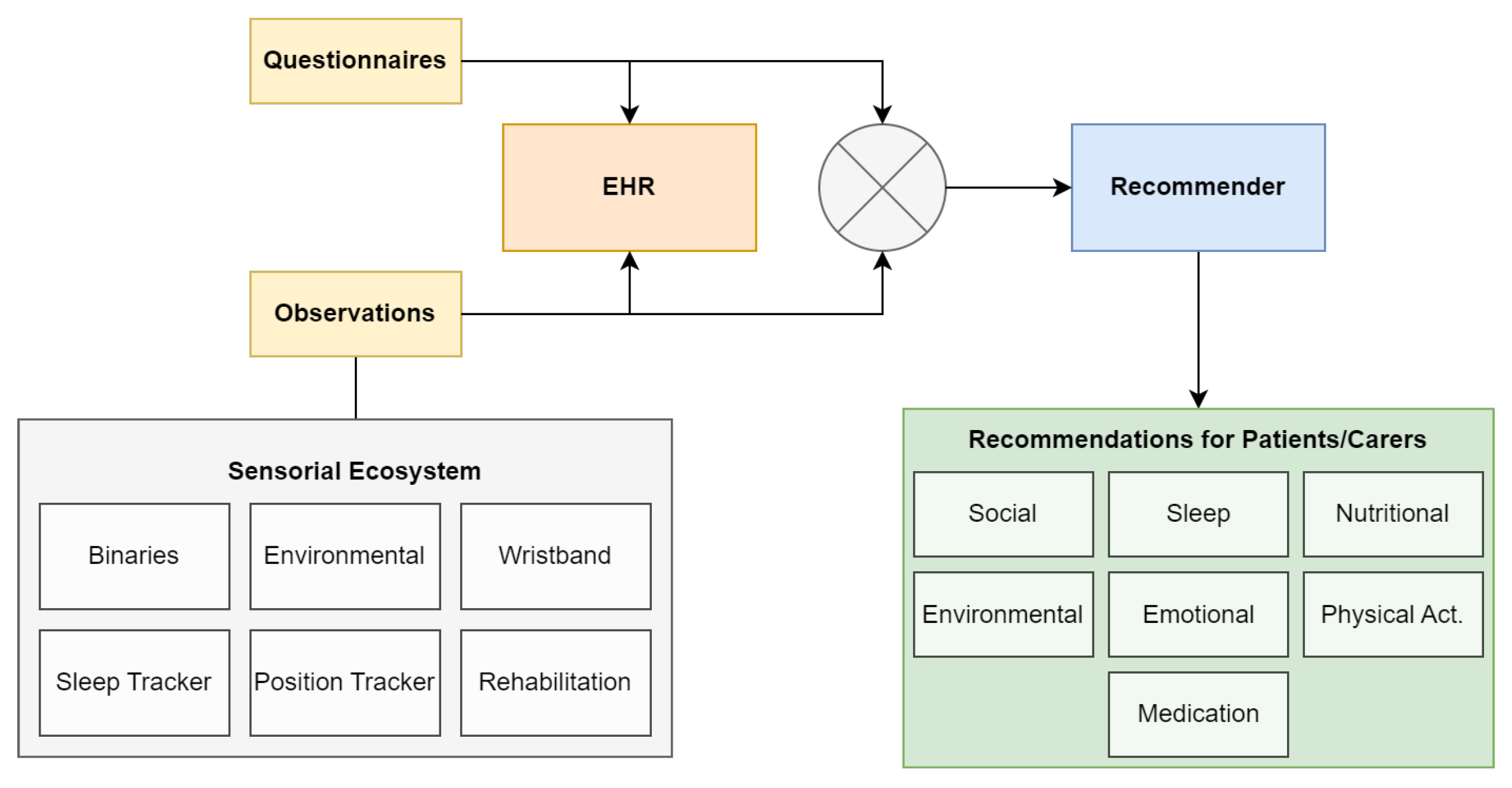

The TeNDER tool consists of an integrated system consisting of a set of devices designed to capture data from various sources related to patient health and well-being. The devices include a sleep sensor, a wristband for fall detection and step tracking, a location sensor, as well as other sensors such as binary and environmental sensors. The architecture of the TeNDER project consists of three main levels: the Low Level Subsystem (LLS), the High Level Subsystem (HLS) and the TeNDER services. The LLS level is responsible for the acquisition of data from the different sensors and consists of the Multisensor Capture module, which is in charge of the deployment of the sensors and their connectivity. The HLS layer processes the information extracted by the LLS layer and provides data aggregation and pre-processing. The TeNDER services layer provides services aimed at improving the quality of life of patients and providing better guidance to healthcare experts on the patient’s health status. At this level is placed the HRS for extracting data and providing notifications to patients, where

Figure 1 depicts the data workflow of different modules focused on feeding data to the HRS.

2.2. Description of the study design and sample

In order to ensure a more personalized experience and accurate data collection, a subsample of patients was extracted from the total population to participate in the HRS pilot. This pilot took place over a period of four weeks, where patients received daily notifications in the mobile app. The total number of participants in the pilot was 37, including 17 patients, 10 caregivers, and 10 healthcare professionals. This allowed for a more hands-on approach to survey administration and ensured that all patients were able to provide their feedback in a consistent and reliable manner. By selecting a subsample, it was also possible to gain a more detailed understanding of the impact of the TeNDER system on a smaller group of patients.

Table 1 summarizes all the data related to the pilot, including the number of patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals involved in the study. The study population was composed of patients with PD, AD or CVD.

The scope of the study were health consortium partners centres: SERMAS (Primary Care centres of the Madrid Health Service, Madrid, Spain), APM (Parkinson’s Association of Madrid, Madrid, Spain), UNITOV (Hospital of the University of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy), SKBA (Neurological Hospital, Schoen Clinic, Prien, Germany), Spomincica (Department of Neurology, University Medical Centre, Ljubljana, Slovenia).

This study made a specific selection criteria for patients, caregivers, and health professionals to be included in the pilot. Patients had to be over 60 years and able to understand the local language. They cannot be unwilling to use the technologies or have a life expectancy less than 6 months. Caregivers must have knowledge of technology and provide support to the patient. Health professionals must be socio-health professionals and have at least one year of professional experience. In

Table 2 are refered further details for selection criteria. All of the participants in the study had to accept and understand their participation and sign the informed consent form.

However, it is important to note that the data collected in this study may be subject to certain biases or confounding factors. For example, self-report measures may be subject to recall bias, and the data collected by the sensorial ecosystem devices may be influenced by factors such as device accuracy and user adherence. These limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the results of the research.

2.3. Data collection and evaluation

Data collection included self-reporting measures. Self-report included the data that was obtained through patient interviews and questionnaires. This information from patients includes: demographic information (gender, age, and main disease), usability and satisfaction (using a validated SUS questionnaire [

40]), and health management attitudes (using an ad hoc Likert-type scale from 1 to 5 that asks questions on self-care, information, autonomy, safety and quality of life. It is scored from "1 - Completely disagree" to "5 - Completely agree").

Research teams contacted the participants via telephone or in person to follow up with them, and interview about the weekly QoL proxy surveys regarding the system. In addition, at the end of the pilot, a post-survey was conducted, which included the QoL questionnaire, SUS questionnaire and a final questionnaire on the degree of satisfaction achieved with the use of RS. The questions included in each of the questionnaires and their objectives are detailed below.

-

QP: QoL Proxy. The measure of effectiveness for the TeNDER system was the QoL Proxy surveys, which were used to assess the impact of the system on participants’ well-being. The QoL proxy questions included in the survey were carefully designed to capture important aspects of daily life, such as physical activity, self-care, social engagement, and emotional well-being. This measure was collected weekly to assess any changes in QoL that may have resulted from using the system and the HRS. The surveys were the following:

- QP1: The TeNDER system has helped me to have information about my health. (1-5)

- QP2: The TeNDER system has helped to improve my autonomy. (1-5)

- QP3: The TeNDER system is a support in my daily life. (1-5)

- QP4: The TeNDER system helps me to improve my self-care (food, physical activity, sleep and rest...). (1-5)

- QP5: The TeNDER system helps me to feel safer and more secure. (1-5)

- QP6: I believe that using the TeNDER system regularly could increase my QoL. (1-5)

Additionally, at the end of the four weeks, a final QoL assessment was performed in the context of the use of the RS, which included the following questions:

-

Q: Quality of Life. QoL assessment performed in the context of the use of the HRS

- Q1: How would you rate your QoL today, in the context of using the TeNDER system? (0-10)

- Q2: Since you have been using the TeNDER system, you believe that your QoL of life has improved? (Improved/Maintained/Worsened)

- Q3: According to your experience of using the TeNDER System, how does its use influence your QoL? (Open)

- Q4: Would you recommend the use of the TeNDER system to a friend or family member? (Yes/No)

- Q4.2: If NO, ask why? (Open)

-

SUS: System Usability Scale. The SUS surveys [

40] were designed to evaluate the usability of the HRS and the overall experience of the patients with it. The surveys included ten questions that were answered on a Likert scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being the most negative and 5 being the most positive response. The SUS questionnaire is evaluated at the end of the four-week pilot period along with the other post-pilot interview questionnaires.

- SUS1: I think that I would like to use the recommender frequently. (1-5)

- SUS2: I found the recommender unnecessarily complex. (1-5)

- SUS3: I thought the recommender was easy to use. (1-5)

- SUS4: I think that I would need the support of a technical person to be able to use this recommender. (1-5)

- SUS5: I found the various functions in the recommender were well integrated. (1-5)

- SUS6: I thought there was too much inconsistency in the recommender. (1-5)

- SUS7: I would imagine that most people would learn to use the recommender very quickly. (1-5)

- SUS8: I found the recommender very cumbersome to use. (1-5)

- SUS9: I felt very confident using the recommender. (1-5)

- SUS10: I needed to learn a lot of things before I could get going with the recommender. (1-5)

-

R: Recommender Satisfaction Feedback. The objective of this questionnaire is to obtain an assessment from the participants on the degree of satisfaction achieved with the use of RS, as well as to obtain key information that will allow us to identify weaknesses in the design and implement improvements in subsequent developments. To this end, two types of questions were prepared, some based on a likert scale 1-5 that allow easy assessment of the degree of satisfaction together with other open questions where participants could freely express their feelings, opinions and comments. The questionnaire consisted of the following questions.

- R1: After your experience using the Recommender, how would you rate your satisfaction with it? (1-5)

- R2: Do you find this service helpful in your daily life? (Yes/No).

- R2.2: Why? (Open).

- R3: What benefits have you found using the recommender? (Open)

- R4: What would you improve about the recommender? (Open)

- R5: What didn’t you like about the recommender? (Open)

- R6: Would you recommend this service to others? (Yes/No)

- R6.1: If NO, ask why. (Open)

2.4. Health Recommender System

The HRS analyzed the data collected from the sensory ecosystem and personalized patient questionnaires (sample list in

Table A1) to identify trigger events that result in patient-specific recommendations aimed at improving specific aspects of daily life. The system used this information to generate recommendations based on the lower-level sensory data. More detailed interconnection between modules is represented in

Figure 1.

The recommendations generated by the system were designed to address various aspects of daily life, including social interactions, sleep, nutrition, environment, emotions, physical activity, and medication adherence (find some examples in

Table A2). These recommendations were triggered based on static observations from patient-worn devices. The connection between devices and the area of recommendation is the following:

Social. Fall detection + social questionnaires.

Sleep. Sleep tracker + sleep questionnaires.

Nutritional. Localization sensor + nutrition questionnaires.

Environmental. Environmental sensor (temperature and humidity).

Emotional. Not specific trigger.

Physical Activity. Wristband data (steps) + phyisical activity questionnaires.

Other. Include medication reminders.

The HRS played a crucial role in supporting patient health by providing tailored recommendations based on a patient’s specific needs and evolution. To do this, it relied on the Electronic Health Record (EHR) [

41] microservice to access the unique claim key for a specific individual and their associated health records (observations). This interaction was facilitated through the use of a REST HTTP protocol, which allowed for seamless communication between the recommendation system and the EHR. EHRs were intended to improve the efficiency and accuracy of healthcare by providing healthcare providers and researchers with immediate access to a patient’s medical information [

42].

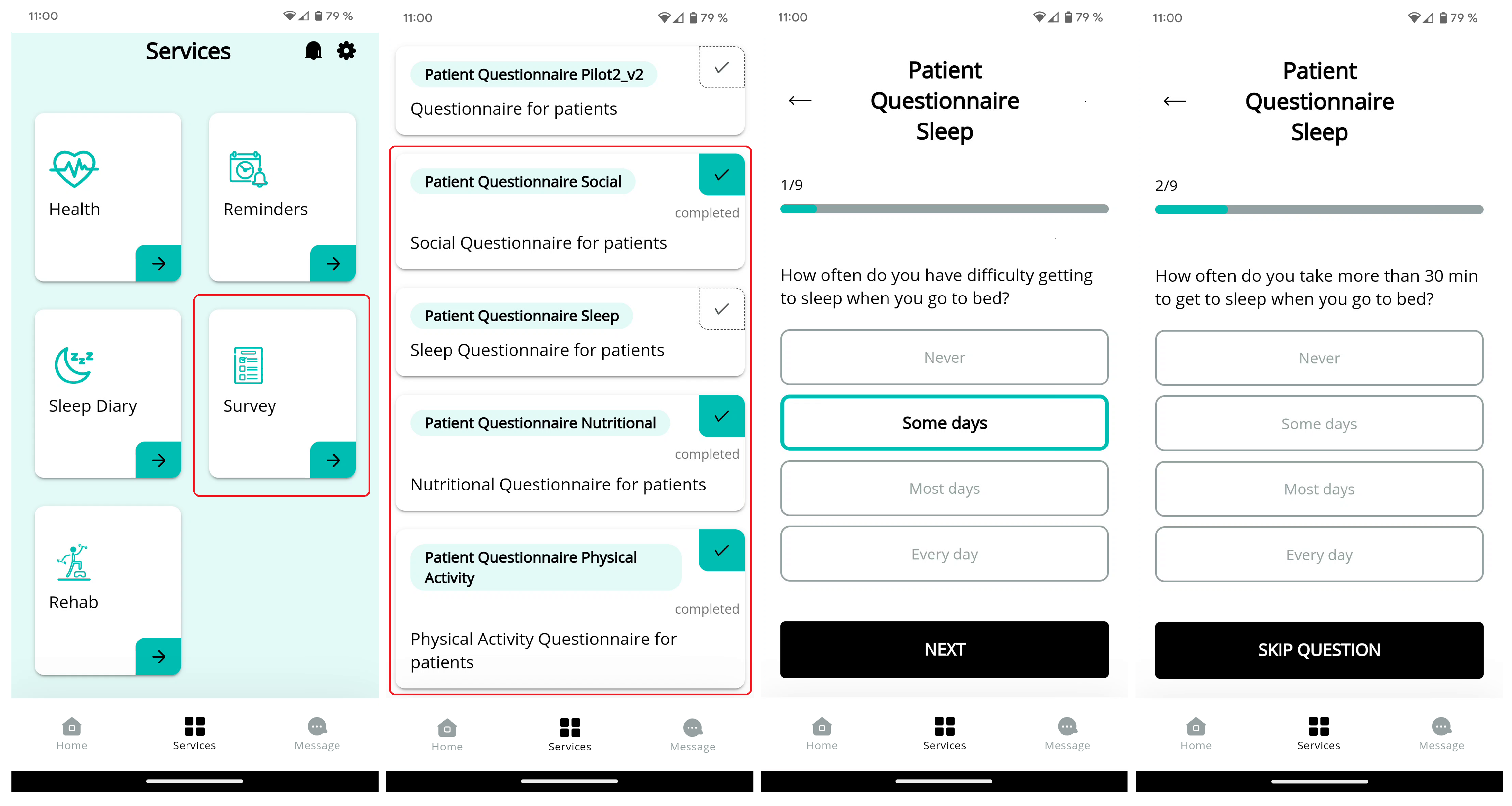

2.4.1. Mobile questionnaires

The main purpose of including the questionnaires in the HRS was to complement the information collected by the TeNDER system through the different devices and sensors. The questionnaires helped us to get a clearer picture of specific aspects of the patients participating in the pilot.

In order to develop the questionnaires, a thorough analysis of the data that the TeNDER system was able to collect was carried out beforehand and possible gaps were analysed in order to send more personalised and appropriate recommendations.

Questionnaires were an important component of the project, providing valuable insights into the daily lives of our participants. These questionnaires were sent by the socio-health professionals to the patients, who then fill them out using our mobile app (workflow example in

Figure 2). The questionnaires cover four key areas of focus: social, sleep, nutritional, and physical activity. These questionnaires helped to better understand the experiences and needs of our participants.

The completion of these questionnaires was vital to the success of the recommendation system as it helpep to personalize the recommendations for each individual participant. The data collected from these questionnaires was used to define the messages to meet the specific needs and preferences of each person, resulting in a more meaningful and effective experience. A sample of the prepared questionnaires is present in

Appendix A.

2.4.2. Recommendation messages

The HRS used daily analysis of a week’s worth of patient data to identify patterns and changes over time, enabling it to provide targeted recommendations based on a patient’s evolution. For instance, if a patient had irregular bedtimes during the week, the system may suggest maintaining a more consistent schedule. Additionally, if the patient reported sleeping difficulties through questionnaires (workflow example in

Figure 2), the system could offer recommendations to address this specific issue. The use of a week’s worth of data with the combination of the results on the questionnaires allowed for a more comprehensive assessment of the patient’s needs, leading to the generation of more targeted recommendations. Appendix B includes additional messages samples of the different areas of the HRS.

To develop the recommendation messages, a careful co-design process was carried out with patients, caregivers and professionals to identify areas of interest and potential triggers. The messages were also reviewed for ease of understanding using language that was fully adapted to end-users.

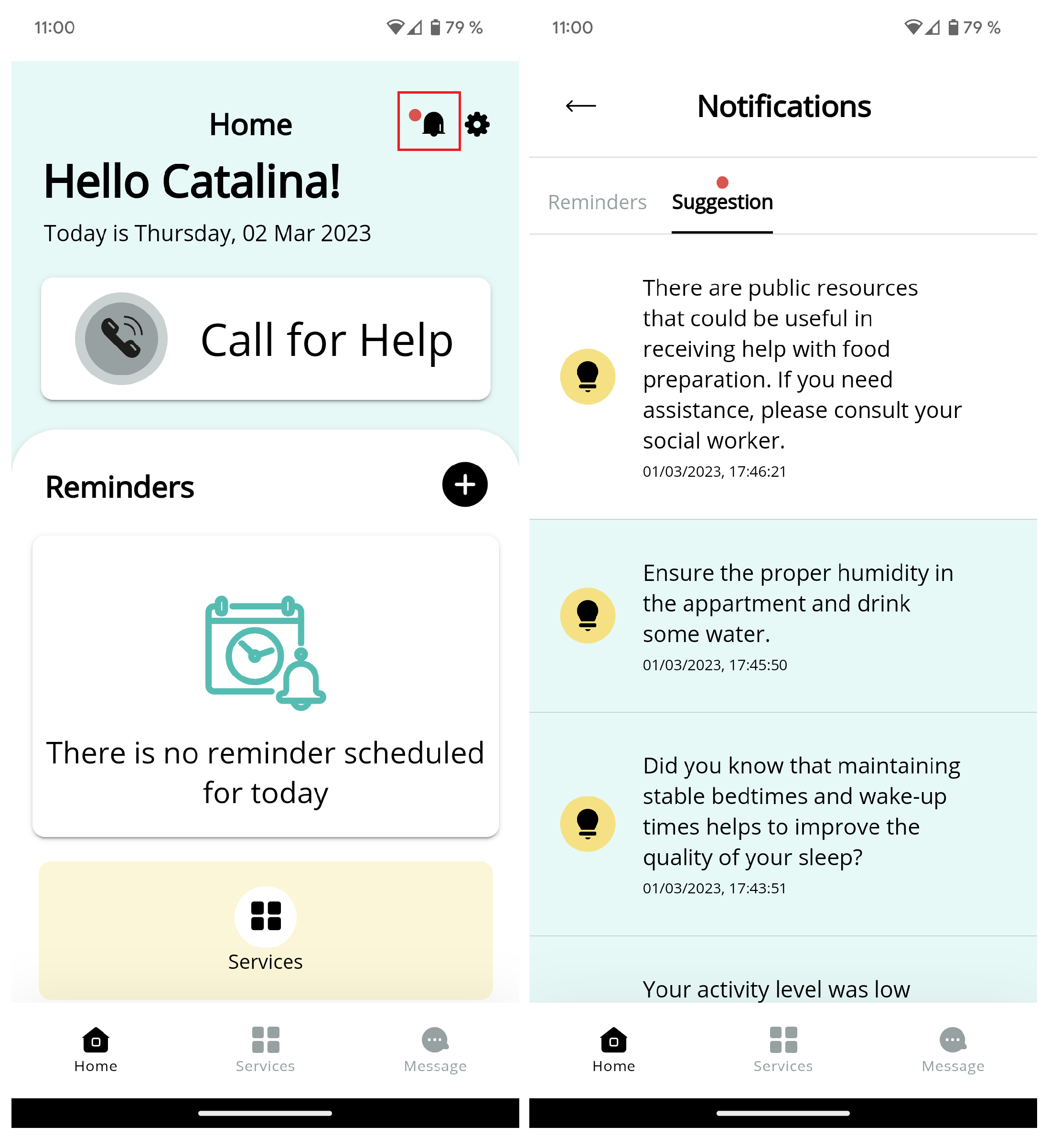

The RabbitMQ [

43] configuration microservice was responsible for handling notifications and events for the recommendation system. It was integrated with the RabbitMQ broker server, which createc a queue and sent notifications and events to the appropriate UI client using a unique notification identifier. This design allowed the HRS to easily access the RabbitMQ configuration to generate notifications or events. A notification example received in the mobile app is observed in

Figure 3.

3. Results

In this section, we present the results of our study on the effectiveness and usability of the proposed HRS aimed at improving the QoL of on users with chronic diseases. The study focused on a specific population of users who were recruited from different geographic region. The patients were monitored by the help of caregivers and healthcare professionals. The study was conducted over a period of four weeks, during which participants were asked to use the given devices and mobile app, where they received the notifications from the HRS.

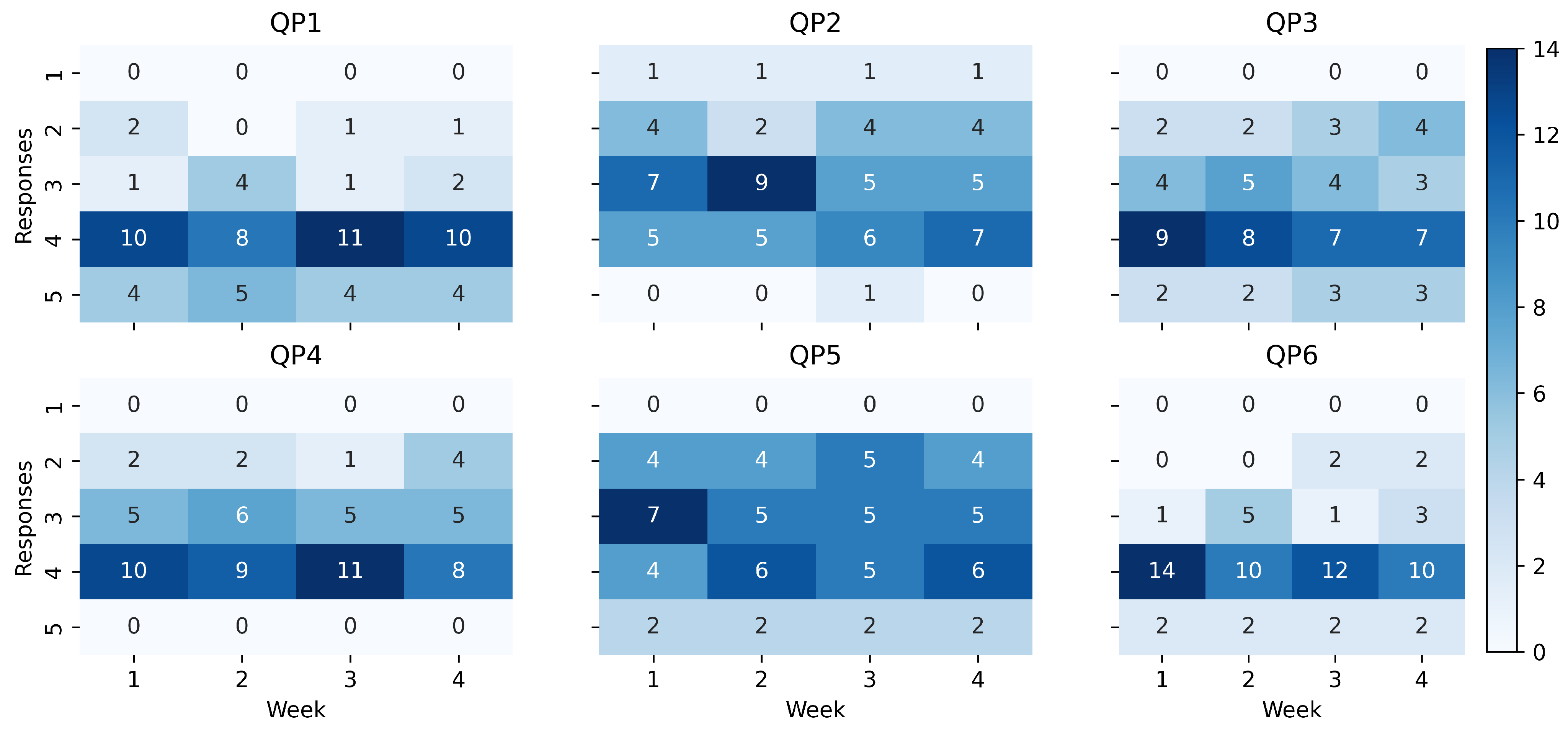

The results of QoL proxy about the study are presented in

Figure 4 using heatmaps. Each heatmap represents the weekly counts of responses for a specific question. The heatmap presentation provides a visual representation of the distribution of responses over time, allowing for a quick overview of the data. Any changes in the distribution of responses can be easily identified, highlighting potential areas of response.

Results showed that the patients had positive responses towards the TeNDER system. The majority of the responses for QP1 (easy access to health information), QP3 (daily support), QP4 (improving self-care), and QP6 (QoL increasing) fell within the range of 4 (agree) to 5 (completely agree). However, there were two questions, namely QP2 (improving autonomy), and QP5 (safer and security), where the responses were more varied. These questions received lower scores than the other questions, indicating that participants may not have experienced the same level of improvement in autonomy and feelings of safety and security as they did in other areas.

At the end of the four weeks, post-interviews were conducted to gather feedback, as well as surveys to assess user satisfaction with the HRS.

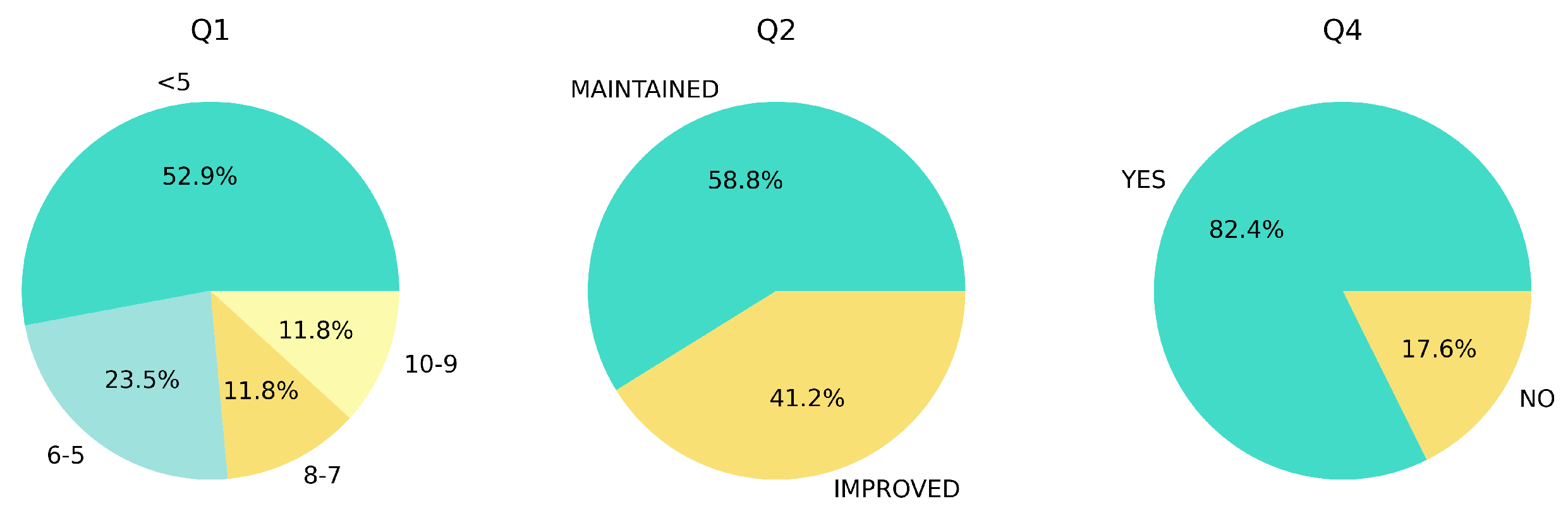

Figure 5 depicts the results of the QoL post-survey. In terms of evaluation of QoL for the patients, over 50% of the patients rated their QoL below 5 points, while the remaining patients were distributed across the higher scale. There was no reported decline in QoL for the patients, with mixed responses indicating either a maintained or improved QoL. Furthermore, for recommending the HRS to other friends or family members, most patients expressed a positive willingness to recommend the system to a friend or family member.

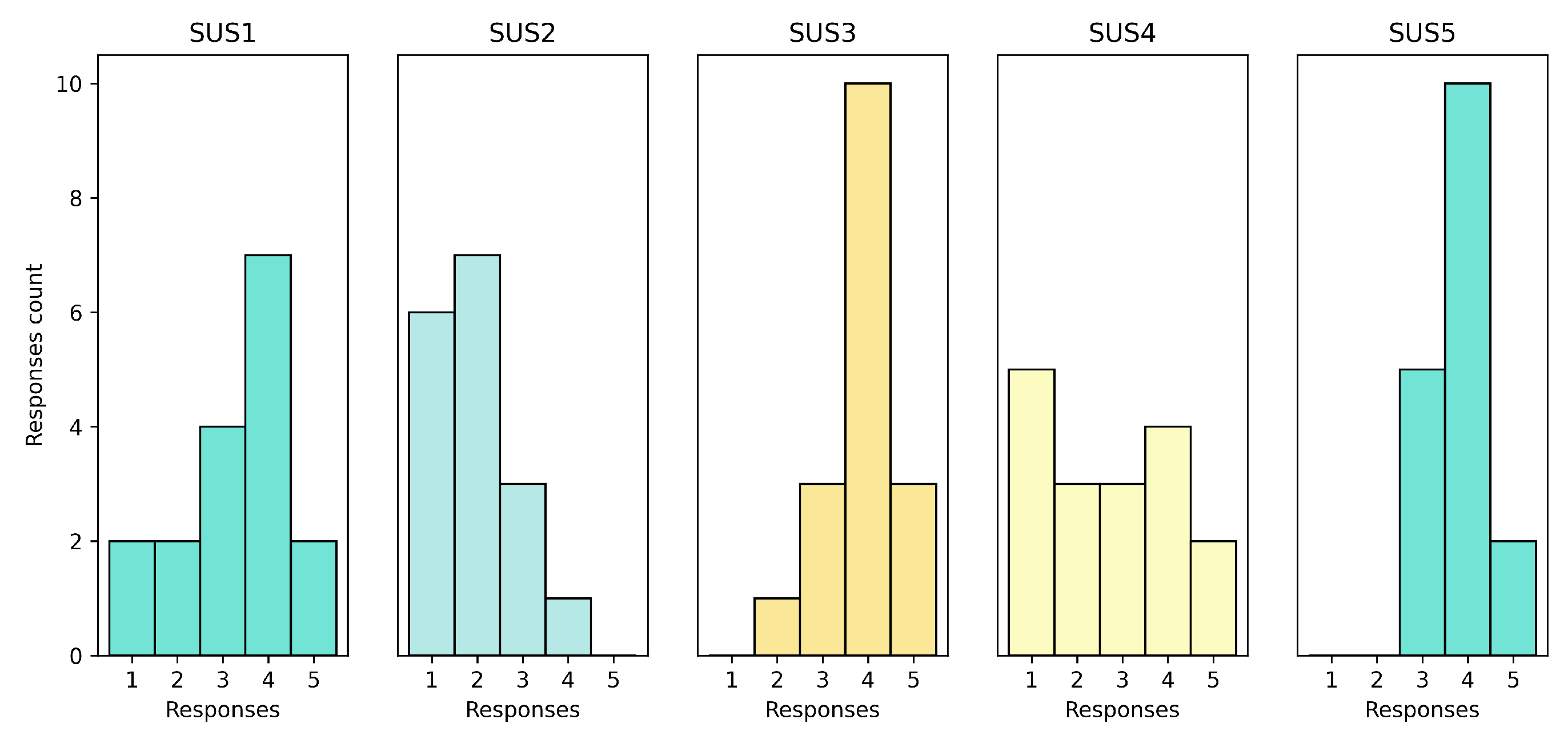

The SUS surveys conducted after the pilot showed that the HRS was appropiate in terms of usability. First set of surveys are presented in

Figure 6. System was well-received by the patients, with SUS1 indicating a stable trend and positive responses. The system was not considered complex by the patients, as shown by the mostly low values (1 and 2) in SUS2. SUS3 and SUS5 showed that the system was intuitive and well-integrated, as most responses were positive and high. The results for SUS4 (need of technical support) were mixed, indicating that some patients required technical support while others did not.

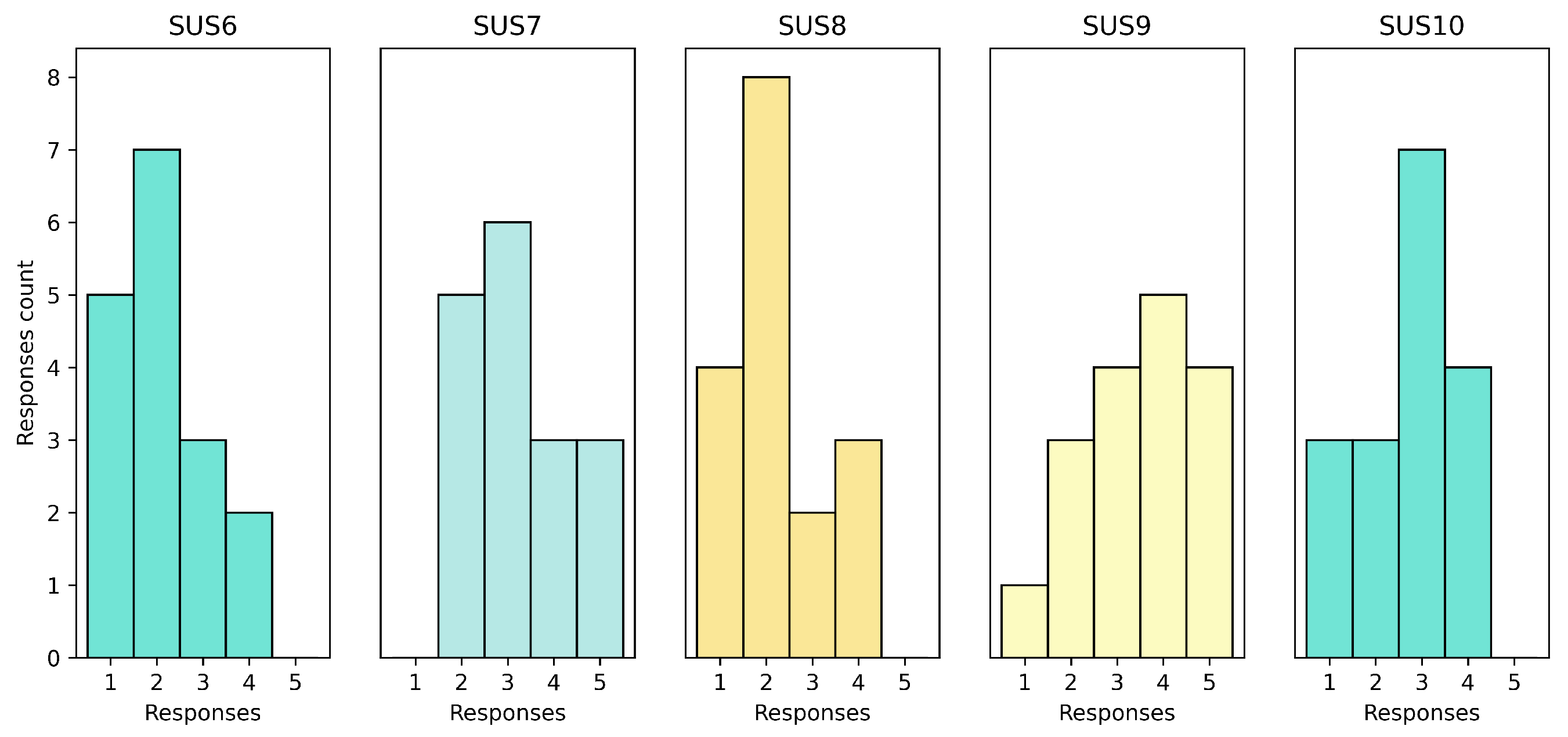

The results of the second set are exposed in

Figure 7. Based on SUS6, they did not show any noticeable inconsistency in the system. SUS7 (learn to use quickly) had mixed results, which implied that some patients had difficulty learning to use the system quickly. SUS8 (too Cumbersome) had more responses on the lower range (1 and 2), indicating that some patients found somewhat complicated to use. SUS9 (confident using the tool) had mixed results, suggesting that some patients felt confident while others did not. Lastly, SUS10 (learn a lot before using the tool) showed results in the middle of the table, suggesting that the patients did not need to learn a lot before using the tool.

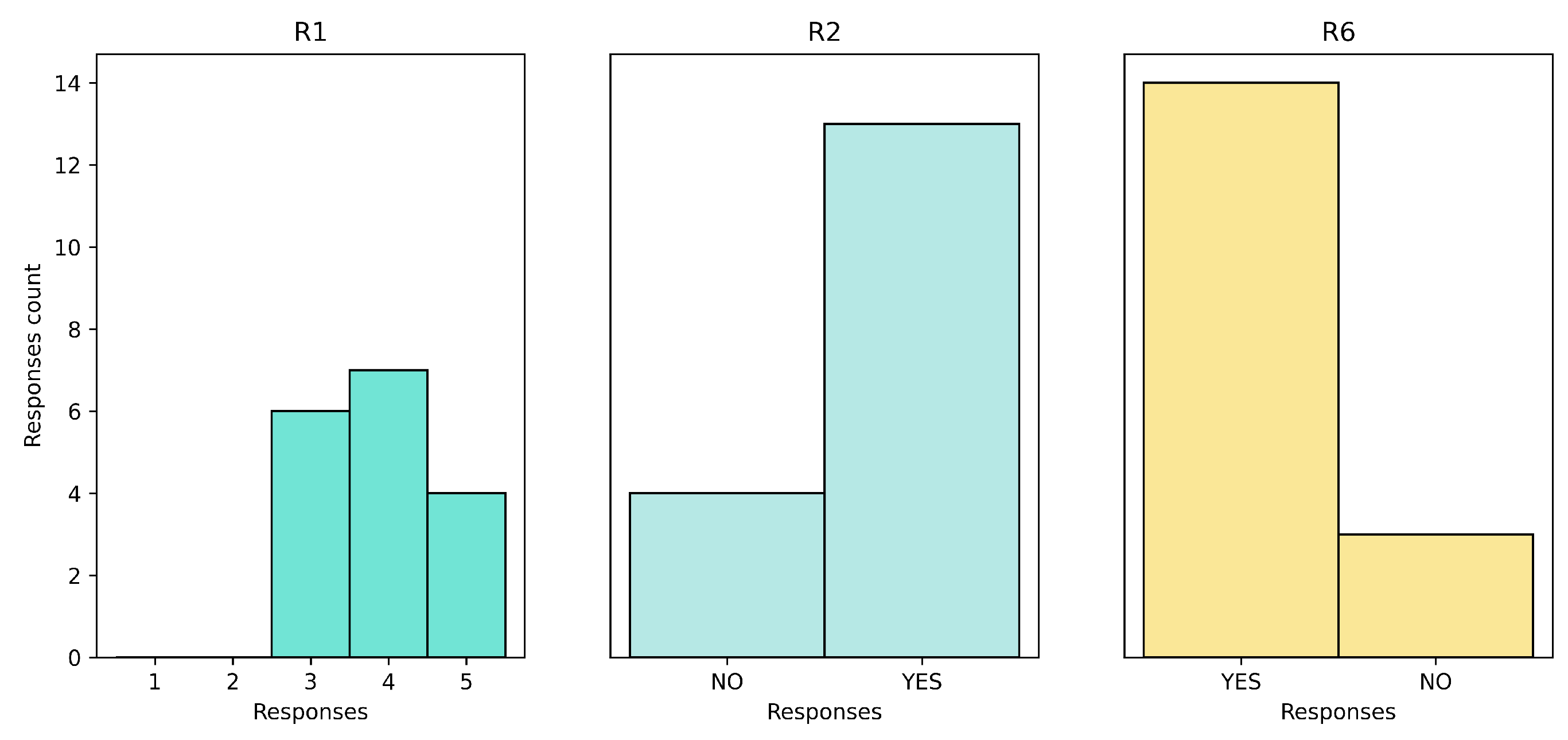

The results of the Recommender Satisfaction and Feedback surveys were generally positive as reported in

Figure 8. The satisfaction rate was mixed on the positive side, with no negative responses. Around 70% of the patients found the service helpful in their daily lives and stated that they would recommend the service to others. In terms of feedback, the responses were open-ended and provided valuable insights for improving the HRS on future work.

4. Conclusions

The conclusions section summarizes the main findings and contributions of the study, and provides recommendations for future work. In this section, we will discuss the implications of the results and how they relate to the research objectives. We will also highlight the limitations of the study and suggest directions for future research to improve the effectiveness on HRS for chronic patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals.

4.1. Discussion of the main findings and their importance

The study findings offer valuable insights into the effectiveness and influence of a HRS on patients with chronic diseases. While the weekly administration of the TeNDER system surveys yielded positive results, there was no evidence of improvement over the course of the pilot.

The majority of patients rated the HRS as user-friendly and easy to use, with positive responses mostly observed for high values. Patients also reported that the system’s functionalities were integrated and consistent, and did not require further technical support.

They were generally satisfied, with a majority finding the service helpful in their daily life and willing to recommend it to others. However, there is still some feedback to be considered, especially regarding the personalization of recommendations and the possibility of including deeper and complex ones.

Finally, the Quality of Life survey showed that the Health Recommender System had a positive impact on the patients’ QoL, with no patient reporting that their QoL had worsened due to the system. The majority of patients reported either maintained or improved QoL.

4.2. Implications of the study for future research

The results of this study have important implications for the design and implementation of HRSs. The findings suggest that these systems have the potential to support individuals in managing their health and improving their overall well-being, and provide a strong case for the use of these systems in a clinical setting. But from this point, there are also several areas where the study leaves open questions or raises new questions for future research.

For example, further research is needed to fully understand the potential benefits and limitations of these systems. This may involve exploring the use of different types of recommendations, identifying specific areas of the system that can be improved to enhance the user experience.

However, future research should focus on expanding the sample size and including different pilots and control group to ensure the validity of these findings. This permits the potential for incorporating patient feedback into the system, progressing iteratively with their opinions.

It is also important to note that this study had several limitations, including the specific context and population studied, which may impact the generalizability of the findings. Future research should aim to address these limitations and explore the benefits and limitations of HRSs in a wider range of contexts and populations.

Even so, the findings of this study have important implications for future research on HRSs in sensorial ecosystems, and provide a strong case for further investigation. For example, looking at long-term effects of the system on patients’ quality of life and explore potential factors that may influence these effects.

In addition, the study may be subject to certain biases or confounding factors, such as the age-selection bias of the study participants or the potential for measurement error in the data collected. These limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the results of the study.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has received funding from the European Commission under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 program - grant agreement number 875325 (TeNDER project, affecTive basEd iNtegrateD carE for betteR Quality of Life). The paper solely reflects the views of the authors. The Commission is not responsible for the contents of this paper, or any use made thereof.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study respects the basic ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, justice and nonmaleficence, and its development followed the norms of Good Clinical Practice and the principles enunciated in the latest Declaration of Helsinki (Seoul 2013). It has obtained a favorable report from the Research Ethics Board of the University Hospital 12 de Octubre and the approval of the Central Research Commission of the Community of Madrid.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. No camera recording or any other identification was made. They were included with an anonymous identifier in the data collection logbook.

Data Availability Statement

All data were processed based on the provisions of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council, of April 27, 2016, and the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights (LOPDGDD, its acronym in Spanish) 3/2018, of December 5. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Participating technical partners and primary care health centers (PCHC) and family physicians (Grupo TeNDER Atención Primaria).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| QoL |

Quality of Life |

| HRS |

Health Recommender System |

| RS |

Recommender System |

| AD |

Alzheimer Disease |

| PD |

Parkinson Disease |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular Disease |

| HLS |

High-Level Subsystem |

| LLS |

Low-Level Subsystem |

| EHR |

Electronic Health Record |

Appendix A. Questionnaires

Table A1.

Sample list of patient questionnaires.

Table A1.

Sample list of patient questionnaires.

| Area |

Message |

| Social |

How often do you feel that you lack companionship: Never (0), Hardly ever(1), some of the time(2), or often(3)? How often do you feel isolated from others? (Never, hardly ever, some of the time, or often |

| Sleep |

|

| Nutritional |

I have had an illness or condition that has caused me to change the type and/or amount of food I eat. Yes (1), No (0) I eat little fruit, vegetables or dairy products.Yes (1), No (0) |

| Physical Activity |

|

Appendix B. Recommendations for patients

Table A2.

Sample list of patient recommender messages.

Table A2.

Sample list of patient recommender messages.

| Area |

Description |

Message |

| Social |

The patient feel alone |

Web link to a social service explaining isolation and give possiblites to groups with other people. |

| |

The patient need help with house-work |

There are public resources that could be useful to receive help with household chores. If you need it, consult your social worker. |

| Sleep |

Irregular sleep time for a few days |

Your sleep score was low for the last days. We recommend to go to sleep more regular. |

| |

General recommendation |

It is good to expose yourself to natural light during the day, and avoid staying indoors for long periods of time. |

| Nutritional |

Loss of weight unintentionally |

You should contact with your health professional to explain the weight loss. |

| |

General recommendation |

Meat should be prepared by removing all visible fat and choosing the leanest parts. |

| Environmental |

Room temperature too high/low for a few days |

The room temperature is detected not to be comfortable for the last days. Please check the heating system or ventilate the apartment if necessary. |

| |

Binary sensors have detected that he forgets to close the main gate at night. |

Remember to check the status of the door before going to bed. |

| Emotional |

The patient is found to be sad or apathetic most of the day. |

Did you know that staying active increases serotonin levels and is one of the most effective ways to fight apathy? |

| Physical Activity |

Low activity time for several days |

Your activity level was low durring the last days. We recommend you to take a walk for a half an hour. |

| |

General recommendation |

Did you know that daily walking can help improve your mood and your quality of sleep? |

| Others |

General recommendation |

To improve the results of your pharmacological treatment, keep fixed schedules for taking your medication. |

| |

General recommendation |

Remember to report any adverse effects of the medication to your referring doctor. |

References

- Allvin, T. Barriers to Integrated Care and How to Overcome Them. https://www.efpia.eu/news-events/the-efpia-view/blog-articles/241116-barriers-to-integrated-care-and-how-to-overcome-them/ [Accessed: 2023-02-14].

- Leadley, R.M.; Armstrong, N.; Lee, Y.C.; Allen, A.; Kleijnen, J. Chronic Diseases in the European Union: The Prevalence and Health Cost Implications of Chronic Pain. Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy 2012, 26, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Ageing 2020: Highlights: Living Arrangements of Older Persons; UN, 2021.

- Corselli-Nordblad, L.; Strandell, H. Ageing Europe: looking at the lives of older people in the EU: 2020 edition; Publications Office, 2020.

- Jaul, E.; Barron, J. Age-Related Diseases and Clinical and Public Health Implications for the 85 Years Old and Over Population. Frontiers in Public Health 2017, 5, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondi, M.W.; Edmonds, E.C.; Salmon, D.P. Alzheimer’s Disease: Past, Present, and Future. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS 2017, 23, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Elbaz, A.; Nichols, E.; Abbasi, N.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Adsuar, J.C.; Ansha, M.G.; Brayne, C.; Choi, J.Y.J.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Neurology 2018, 17, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheltens, P.; Strooper, B.D.; Kivipelto, M.; Holstege, H.; Chételat, G.; Teunissen, C.E.; Cummings, J.; van der Flier, W.M. Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet 2021, 397, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimler, R.; Maresova, P.; Kuhnova, J.; Kuca, K. Predictions of Alzheimer’s disease treatment and care costs in European countries. PloS one 2019, 14, e0210958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V.L.; Nichols, E.; Alam, T.; Bannick, M.S.; Beghi, E.; Blake, N.; Culpepper, W.J.; Dorsey, E.R.; Elbaz, A.; Ellenbogen, R.G.; others. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Neurology 2019, 18, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Sherer, T.; Okun, M.S.; Bloem, B.R. The Emerging Evidence of the Parkinson Pandemic. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease 2018, 8, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñas, E; Gálvez, M.M.M.P.O.M. El Libro Blanco del Párkinson en España. Aproximación, análisis y propuesta de futuro.; 2015.

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) fact sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) [Accessed: 2022-03-30].

- European Health Network. European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2017 - EHN - BHF.

- Rijken, M.; van Kerkhof, M.; Dekker, J.; Schellevis, F.G. Comorbidity of chronic diseases. Quality of Life Research 2005, 14, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.T.; Le, N.H.; Khanal, V.; Moorin, R. Multimorbidity and its social determinants among older people in southern provinces, Vietnam. International Journal for Equity in Health 2015, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violan, C.; Foguet-Boreu, Q.; Flores-Mateo, G.; Salisbury, C.; Blom, J.; Freitag, M.; Glynn, L.; Muth, C.; Valderas, J.M.; Vari, C.; others. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies. PloS one 2014, 9, e102149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaba, O.; Chola, L. The social determinants of multimorbidity in South Africa. International journal for equity in health 2013, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudasama, Y.V.; Khunti, K.; Gillies, C.L.; Dhalwani, N.N.; Yates, T.; Davies, M.J.; Seidu, S.; Rowlands, A.V.; Henson, J.; Stensel, D.J.; et al. Physical activity, multimorbidity, and life expectancy: a UK Biobank longitudinal study. BMC medicine 2019, 17, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Durstine, J.L. Physical activity, exercise, and chronic diseases: A brief review. Sports Medicine and Health Science 2019, 1, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solachidis, V.; Moreno, J.R.; Hernández-Penaloza, G.; Vretos, N.; Álvarez, F.; Daras, P. TeNDER: towards efficient Health Systems

through e-Health platforms employing multimodal monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM Conference on Connected

Health: Applications, Systems and Engineering Technologies (CHASE), 2021, pp. 185–192. [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Dutta, M. A systematic review and research perspective on recommender systems. Journal of Big Data 2022, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Dutta Pramanik, P.; Dey, A.; Choudhury, P. Recommender Systems: An Overview, Research Trends, and Future Directions. International Journal of Business and Systems Research 2021, 15, 14–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Salunke, A.; Dongare, S.; Antala, K. Recommender systems: An overview of different approaches to recommendations. 2017 International Conference on Innovations in Information, Embedded and Communication Systems (ICIIECS), 2017, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Hors-Fraile, S.; Rivera-Romero, O.; Schneider, F.; Fernandez-Luque, L.; Luna-Perejon, F.; Civit-Balcells, A.; de Vries, H. Analyzing recommender systems for health promotion using a multidisciplinary taxonomy: A scoping review. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2018, 114, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Croon, R.; Van Houdt, L.; Htun, N.N.; Štiglic, G.; Vanden Abeele, V.; Verbert, K. Health Recommender Systems: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 2021, 23, e18035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, H.; Hors-Fraile, S.; Karumur, R.P.; Calero Valdez, A.; Said, A.; Torkamaan, H.; Ulmer, T.; Trattner, C. Towards Health

(Aware) Recommender Systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Digital Health;

Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; DH ’17, p. 157–161 [CrossRef]

- Asthana, S.; Megahed, A.; Strong, R. A recommendation system for proactive health monitoring using IoT and wearable

technologies. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on AI & Mobile Services (AIMS). IEEE, 2017, pp. 14–21. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.N.; Srivastava, S.K.; Gururajan, R. Integrating wearable devices and recommendation system: towards a next generation healthcare service delivery. Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application (JITTA) 2018, 19, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Rani, S. A novel approach for smart-healthcare recommender system. In Proceedings of the Advanced Machine

Learning Technologies and Applications: Proceedings of AMLTA 2020. Springer, 2021, pp. 503–512. [CrossRef]

- Etemadi, M.; Abkenar, S.B.; Ahmadzadeh, A.; Kashani, M.H.; Asghari, P.; Akbari, M.; Mahdipour, E. A systematic review of

healthcare recommender systems: Open issues, challenges, and techniques. Expert Systems with Applications 2022, p. 118823. [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, E.; Özkan, S. A systematic literature review on Health Recommender Systems. In Proceedings of the 2013 E-Health and

Bioengineering Conference (EHB), 2013, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Park, D.H.; Kim, H.K.; Choi, I.Y.; Kim, J.K. A literature review and classification of recommender systems research. Expert Systems with Applications 2012, 39, 10059–10072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.L.; Durusu, D.; Sui, X.; de Vries, H. How recommender systems could support and enhance computer-tailored digital health programs: a scoping review. Digital health 2019, 5, 2055207618824727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lu, J.; Jin, Y. Artificial intelligence in recommender systems. Complex and Intelligent Systems 2021, 7, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.M.R.; Kwak, D.; Kabir, M.H.; Hossain, M.; Kwak, K.S. The Internet of Things for Health Care: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Access 2015, 3, 678–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asthana, S.; Megahed, A.; Strong, R. A Recommendation System for Proactive Health Monitoring Using IoT and Wearable Technologies. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on AI Mobile Services (AIMS), 2017, pp. 14–21. [CrossRef]

- Continued use of wearable fitness technology: A value co-creation perspective. International Journal of Information Management 2021, 57, 102292. [CrossRef]

- Hors-Fraile, S.; Rivera, O.; Schneider, F.; Fernandez-Luque, L.; Luna-Perejon, F.; Civit, A.; de Vries, H. Analyzing recommender systems for health promotion using a multidisciplinary taxonomy: A scoping review. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2017, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A quick and dirty usability scale. Usability Eval. Ind. 1995, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour, T.; Frantsvog, D.; Graeber, T.; et al. Electronic health records (EHR). American Journal of Health Sciences (AJHS) 2012, 3, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Rubinstein, S.M.; Nead, K.T.; Wojcieszynski, A.P.; Gabriel, P.E.; Warner, J.L. The evolving use of electronic health

records (EHR) for research. In Proceedings of the Seminars in radiation oncology. Elsevier, 2019, Vol. 29, pp. 354–361. [CrossRef]

- RabbitMQ. What is RabbitMQ? https://www.rabbitmq.com/ [Accessed: 2022-12-20].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).