1. Introduction

Historical city textures are cultural treasures in accommodating lifestyles, cultures, social and economic structures of various civilizations through their histories. Public open spaces, which create such textures and positively contribute to socialization, are today alive with the effect of landscape elements as the city furniture providing functionality and authenticity to these spaces.

City furniture are comprised of urban equipment, environmental equipment, landscape elements, design and decoration elements, and they are open to the use of all people regardless of their age, gender, or financial status. In addition to being designed and located in the way of serving for relaxation, passing time, and information purposes etc., these elements also contribute to the sustainable development of such public spaces, and enhance the urban comfort and life quality by creating various activity centers in the city.

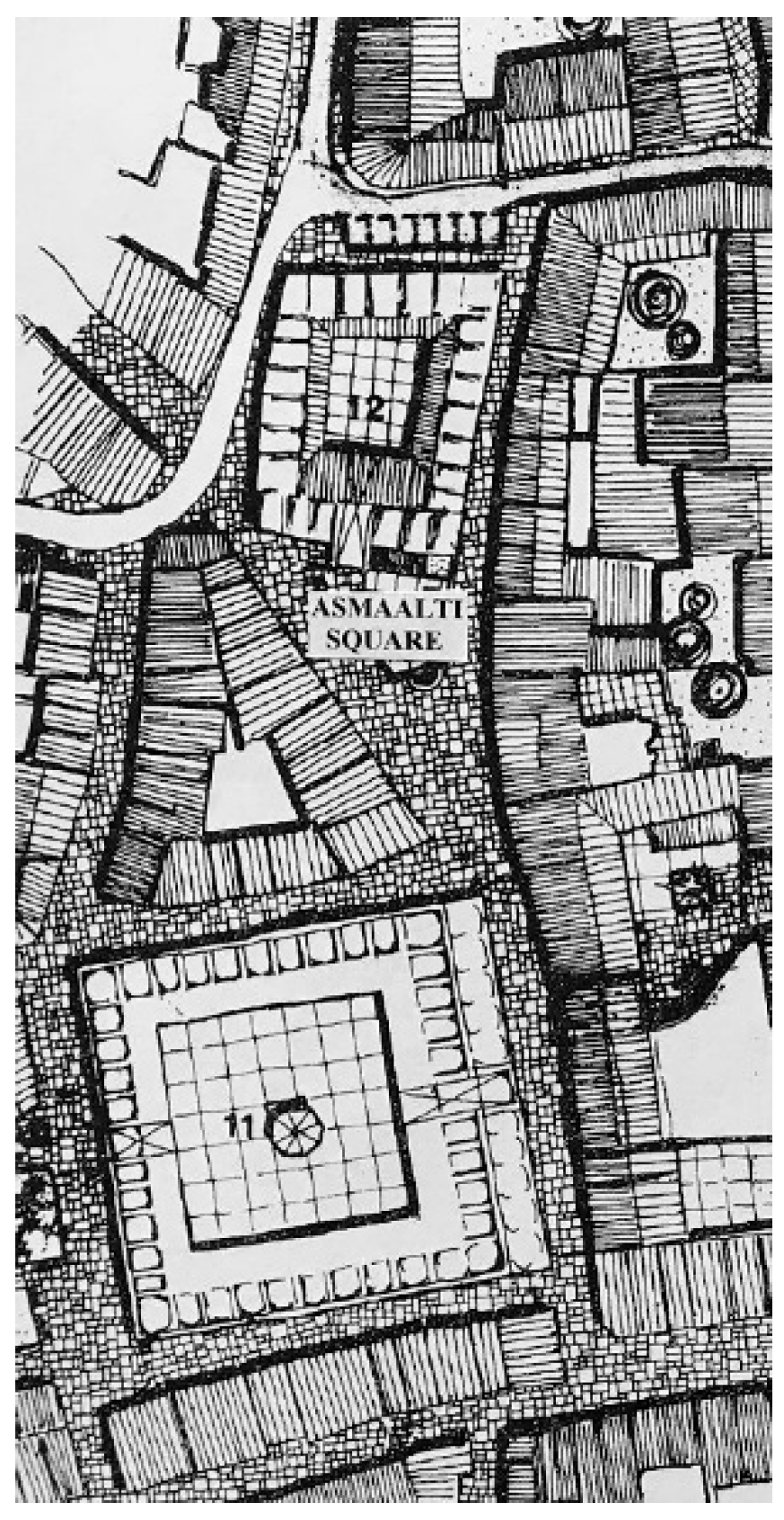

Since the beginning of its urban formation, the historical city texture of Nicosia has lived up to today with its open-air museum quality with the influence of many different civilizations. While giving life to the walled city of Nicosia, public open spaces have mainly become the centers through all historical periods for gathering, meeting, shopping, and entertainment. Even though the historical texture has undergone extensive deterioration and demolishing, the historical texture is still interesting with its cultural identity and surviving architectural structures.

The historical urban texture of Nicosia, the capital of the island of Cyprus, has been crucial since its formation with the effect of public open spaces together with its highly substantial architectural works. Although there are some studies related to the public spaces within the historical urban texture of Nicosia, there are no comprehensive studies regarding the functionality of recent arrangements in the public spaces of the historical texture and various recently designed urban furniture, and their conformity with the historical texture. Therefore, this study is of importance in that respect.

The aim of this study is to analyze the public open spaces of the historical urban texture of Nicosia, which is an important cultural heritage area, together with urban texture as a complementing element of landscape planning. Therefore, this study also aims to examine the conformity of urban furniture with the texture through two important squares in the walled city of Nicosia with the view of making assessments, and presenting proposals on urban furniture in historical urban textures.

The scope of the study is comprised of historical urban texture, public open spaces, concept of urban furniture, and use of urban furniture in two important squares of the historical urban texture of Nicosia. The study then concludes with proposals, the assessment of conformity of urban furniture with the historical texture respectively.

1.1. Research Questions

The compatibility and functionality of the urban furniture in the squares within the historical city wall of Nicosia with the historical texture will be examined.

1.2. Limitations

The conceptual limitations of the study are the historical city, public open spaces, squares and urban furniture. The boundaries of the field research are Asmaaltı and Selimiye Squares, which are in the historical urban fabric of Nicosia, Cyprus. The renovation works conducted in the related research areas are insufficient and incompatible with the texture, hence a limitation is provided accordingly.

2. Theoretical Framework: Urban Furniture in Historical Urban Texture and Landscape

2.1. Historical Urban Texture and Landscape

Historical urban textures are spaces of living history from the past and stretching into the future. These textures are cultural heritage areas beginning with their formations and developing and shaping with the influence of different civilizations. Historical urban textures are valuable assets that establish a bridge between the present and past in addition to their social, cultural, and economic structures in their formation processes, with their architectural works and public open spaces (Ahunbay, 2004).

The recommendation decisions issued by UNESCO and adopted in 2011 define the concept of historical urban landscape as urban spaces covering a broader urban context and geographical setting beyond the historical center and buildings that are expressed by the cultural, natural values and features of historical spaces (UNESCO, 2011).

Historical urban landscape includes all natural, environmental and urban characteristics of specific area like topography, physical nature, hydrology, infrastructure, historical monuments and open spaces as well as social, cultural assets and economic properties. The improvement of historical urban landscape spaces increases the social, cultural and functional use while facilitating the improvement in the quality of life (Perihan and Aşur, 2020).

Historical urban texture and landscape are significant cultural heritage elements that form and evolve as a result of positive or negative human activities. Incorporating the physical indicator of civilizations, such spaces are an example of precise, balanced examples of mastership with landscape planning, architectural buildings and coherent transportation links. They also attract admiration with socio-economic nature, life philosophy, assets, forms and general outlook.

Since historical urban textures and landscapes are planned as per human sizes, they are didactic and attract attention. They also have features and atmospheres that positively improve the social and cultural relationships among people where they create common values together as they feel the importance of living.

Historical urban textures and landscapes are almost like outdoor museums exhibiting the life throughout history in a world with constantly changing modes of living and production. People feel happy and learn about the creativity, mastership of others from the past when they try to comprehend, understand and review such spaces, and spend their time there. Although their real residents are extinct, they are important for us and future generations that we could find their traces, visit monumental trees, wander around meandering streets and discover places.

On the way of becoming a cultural mosaic, the structures from various periods, public open spaces, lifestyles of people and their cultures affect historical cities. Cultural accumulation from the past, which is formed when people widely use public open spaces for meeting, gathering, and recreational purposes, and their functionality show that these spaces add importance and richness to the historical texture, and reflect the characteristics of the traditional textures of the historical city (Kuban, 2000).

They are spaces for various functions like trade, political and social activities that were embodied with the permanent settlement of people in historic process. Squares are public spaces used as centers for gathering, socialization and recreation while contributing the socialization of people (Turkan, 2008). As the prominent elements, symbols of cities, the squares are the combination of firm ground and green spaces with various urban furniture as sitting units, sculptures, water elements, and cafeterias. Scale, location, visual – aesthetic structure, intended activities, diversity of plant components and urban furniture are vital in enhancing the spatial quality of squares (Öztürk, 2009).

It is important that squares, which are important socialization spots, have functionality as public spaces so that people can socialize, spend good time and feel safe. Hence, squares should have closure with the feeling of enclaved, and sound boundaries while allowing people easily walk around. These four main physical features are grouped as spatial enclosure, continuation of boundaries, pedestrian circulation and ratio/scale. Therefore, the most prominent feature of squares is the enclosure and confinement both of which are the most important elements of public spaces. People feel safer in confined spaces with certain boundaries and use such spaces more than the others. In order to define a public open space as a square, such spaces should have obvious and explicit boundaries with architectural structures and landscape components. Historical squares are more enclosed in nature due to organic evolution upon the influence of past civilizations and interwoven meandering axis (Yıldız, 2002). The square boundaries are established with architectural structures, sculptures, fountains, monuments, plants, water elements and other furniture components. The availability of boundaries affects the control of privacy, security, pedestrian and vehicle traffic. The bordering buildings and other elements in the square must be consistent, simple and sustainable in terms of size, form, color and design. Otherwise, it would be confusing for its users and the borders may start losing their absolute lines (Gültekin, 1996). Squares are the stops for mobility in public open spaces like street and avenue. As people socialize, get together and spend time in such spaces, they should act comfortable, safe and relaxed. The circulation axis at squares and connecting avenue and streets should be constant, accessible, free from vehicle traffic inviting its users that would make such places much livable. The physical features of pedestrian mobility axis should provide equal access for all individuals and be compatible with urban texture that would contribute the urban identity as well (Eren et.al, 2011). The size of squares, surrounding architectural buildings, landscape elements and their proportions to one another impact the formation of such spaces. The users would perceive squares and feel safe and secure where the ratio and scale of such spaces are consistent with human scale, which is created through the planned and appropriate use of landscape elements (sculpture, fountain, monuments, plants etc.) (Önder and Aklanoğlu, 2002).

Urban open green spaces consist of the areas outside and surrounding the buildings (Mygind, et al., 2016). Open areas are defined as openings or spaces outside of architectural structures that serve for rest or agricultural use while the green area is the urban parts arranged with plant and structural landscape elements of open spaces (Özbilen, 1991).

Urban open and green spaces contribute to the increase of land value and job opportunities in the regions where they are located. They constitute a center of attraction for the people of the city for recreation, sports, art, education and socialization activities. They provide protection of wildlife and biodiversity and regulation of urban climate. They allow to create an organic order in cities and establish a balance in accordance with the human scale (Jin and Wang, 2020; Thompson, 2002).

Squares are public spaces with a central character located among architectural structures or green elements in the cities. Additionally, squares are public open spaces where commercial, political and social activities are held. They consist of a combination of hard ground and green areas and contain many urban furniture and cafeterias such as seating units, sculptures, water elements (Öztürk, 2009; Stocco, et al., 2015).

Modern culture era that we try to put meaning and maintain historical urban textures has some effects on our lives. The positive impact of this era on historical texture and landscape is that it is possible to access all kinds of data with regard to the formation and evolution of textures as cultural heritage through the history.

Since Industrial Revolution started in the second half of XVIII. Century, a number of factors like developing technology, industrialization, pursuit for change resulting from social needs have changed the urban identities as well as historical textures and landscapes as the vital elements of such spaces. Moreover, the changes in world circumstances and lifestyles led to consumption-oriented perspective, and the value of old diminished as some people wonder the new and want to live in luxury. All of such conditions, unplanned and uncontrolled developments cause major problems as well as irremediable destruction in historical areas. Politics, economy, population and planning might be listed as the factors that cause deterioration in historical texture and landscape.

Laws that are drafted to reach any objective and ensure plan and controls on all elements affecting living spaces and human life, and policies as the methodology for implementation are crucial for the protection of historical texture and landscapes. Just like in every aspect of life, the notion of economy is important in the actions towards preserving and restoration of historic cities. Insufficient and inappropriate use of economic funds contribute the damage on historic city and landscapes. Moreover, population, which is defined as all residents of an area, has direct impact on the development, preservation and destruction of historic environments. The formation of historical urban textures was based on specific plan and its associated principles. These textures and their structural elements evolved based on environmental conditions, vital needs and existing necessities.

Conservation may refer to the activities towards handing our natural and cultural heritage down to future generations in the best way possible. The concept of conservation is defined under the charter of ICOMOS as the complete activities for the preservation of historical texture and their renewal and promotion in accordance with the appropriate principles (ICOMOS, 2013).

The first step in the conservation and restoration of historic cities is the organization of architectural buildings and their courtyards. The second step is related with all green spaces covering streets, avenues and squares that have direct link with such structures and spaces. All elements of texture should be considered as a whole in the performance of conservation activities due to their specific features of each element as they come together, social relations network, traditional living culture, use of space, nature-human relation and types of production (Çelik, 2004).

The concerns about the conservation of cultural heritage elements occurred and evolved for different purposes varying by the conditions, requirements and perspective of its time. The sense of conservation is at times shaped by economic, social and political conditions as well as religious, national and aesthetic emotions. Hence it is possible to say that conservation is different in every era. The first steps towards contemporary conservation are originated to the end of 19th century and numerous comprehensive works were performed in Italy (Kan, 2009).

Today, there are international efforts for conservation and restoration of historical urban textures with adopted laws and regulations.

2.2. Urban Furniture and Its Use in Historical Textures

Urban furniture are accessory elements serving for the use of people and meeting their needs in public open spaces, which are important features of cities. In other words, urban furniture are features complementing public open spaces, giving them an identity, and adding positive effects aesthetically and psychologically (Peters et al., 2010).

Urban furniture, reflecting the life cultures of people living in cities and giving shape to spaces, are divided into four main classes (Akyol, 2006).

One of the four main classes is urban furniture according to their aims which are divided under two headings as functional and visual. Functional urban furniture aim to meet the needs of people in public open green spaces, and are elements commonly used by the society. In cities, functional urban furniture serve the aims of protection, recreation, sanity, shopping, communication, sheltering, directing-informing, limitation, and decoration. Visual urban furniture on the other hand, possess values such as, semantic, monumental, symbolic, and aesthetic, and give visual values to cities. Second class is the urban furniture according to the location they are placed as these are decorative elements in public open green spaces providing meaning and function. These spaces, in which urban furniture take place, are divided into four main groups as parks, resting and entertainment areas, sports-children’s games areas, and organized pedestrian areas. Another class is the urban furniture based on their technical equipment. These are divided into two as connected to the infrastructure and independent of the infrastructure. Road and space illuminators, traffic lights, square clocks, bus stops, kiosks, and water elements are urban furniture connected to the infrastructure whereas paving and border elements, information signs, advertising and announcement panels, shading elements, park and picnic area elements, litter boxes, and statues are urban furniture independent of the infrastructure. The final class is the urban furniture according to their mobility. Most of the urban furniture in public open green spaces are used as immobile elements, although they depend on their fields of function and use. However, some urban furniture can be used as mobile or semi-mobile. Litter boxes are one of the examples for mobile urban furniture. Urban furniture are elements with different functions and characteristics, and each requires a different design process. Life culture, traditions, environment, history, perception, psychological direction can be listed as the factors affecting the design process. Yet, the perceptibility of the urban furniture by the user is the most important point. Moreover, time and method, essential for the formation process of each element, can show differences (Bingöl, 2017). The design process includes three different stages respectively. The first stage is the emergence of demand. Public open green spaces in cities where people spend their lives, meet many different needs of individuals, and open green spaces are made up of urban furniture. The increasing amount of construction and demands arising to improve the quality of life and space of people living in ever condensing cities, make urban furniture more essential (Yaylalı, 1998). The second stage is the determination of needs. The demand for the necessity of urban furniture also paves the way to crystallize and plan the needs (Çoban and Demir, 2014). The last stage is data collection, which is the time of research where methods like surveys, experiments, and observations are used towards establishing the expectations of the users of space. As a result of the research, it is determined which urban furniture is needed in that specific space, and application is triggered to bring out functional conclusions (Güner, 2015).

Urban furniture are classified as paving elements, sitting units, illumination elements, sign and information panels, limitations, water elements, shaded elements, artistic elements, and other decorative elements, and they are explained based on their design criteria (Karaca et.al. 2020).

First category of urban furniture is paving elements that are stone, timber, concrete, asphalt, and botanic (grass) elements. In the paving design, the elements suitable to the environmental conditions and the characteristics of the area should be used. Second category is sitting elements with benches, chairs, and sitting groups. They should be designed in proper size and shape for the users, and should be functional. Next category is illumination elements. These are road and space illuminators. In the design of illumination units, it is important to ensure their harmony with the texture of the space in material, shape, and color, and they should be efficient and durable. Another category is direction and information panels. Directors and position finders are made up of data communication panels. They should be designed in a way to be visible, comprehensible, simple, durable, and sustainable. There is also a restrictive category with deterring, limiting for safety, surrounding elements, and pedestrian and traffic barriers. Their construction materials should be coherent with the environment, and should create positive effects aesthetically, functionally, and psychologically. Water elements is another urban furniture category. These are ornamental pools, fountains, water canals, and water tunnels. They should be designed based on their location and should have positive psychological and aesthetic effects. Next category is the top cover elements. Bus stops, shades, and pergolas fall into this category. Their design should ensure that they serve aims like providing shade and protection from rain. Another category is artistic elements. These are made of objects or statues that are symbols of the space and complement the landscape composition of the area in which they are placed. They should reflect the identity of the space and should be designed to be compatible in material, shape, and size. Last category is other accessory elements. This category comprises game elements, litter boxes, flower beds, square clocks, bicycle parking stations, and botanical elements. The design of these elements, which are complementary components of public open spaces in cities, should made of materials that are compatible with the environment, and they possess functional qualities in size and shape (Bolkaner, et. al., 2019).

Urban furniture is one of the most important components in providing functionality to areas aiming to regain usage of public open spaces which form the historical urban textures. Urban furniture that are planned, compatible, well designed reflecting the identity of the city, increase the availability of these spaces, and affect the protection of their historical values. There are several principles to be followed towards this aim (Yıldırım, 2004).

Firstly, unity should be established among visual balance, rhythm, repetition, proportional relations, color, texture, line, and form among design elements, surrounding historical buildings and other components. It should be noted that urban furniture should be compatible and related with the unique nature of historical environment in shape, order, character, and functionality. With the aim of ensuring unity in style among all design elements, traditional design elements should be selected instead of modern ones. The different, eye-catching, mobile elements should be preferred to add richness to the texture without disrupting the characteristics of the historical texture. It is important to use comprehensible, non-complicated elements to bring out the components in the historical textures. Elements that will bring out the historical and cultural value of the historical environment should be selected throughout the design process. A balance should be achieved between the characteristics of the texture with urban furniture in form, measurement, and color. The elements to be selected should be suitable to human measurements and reflect the characteristics and cultural aspect of the historical texture with traces of them. Applications that will cause damage to the historical environment should be avoided in placing urban furniture. It should be remembered that protection of historical cities and ensuring sustainability are the main goals in placing urban furniture.

2.3. Public Open Spaces in Historical City Texture of Nicosia

The island of Cyprus has one of the oldest recorded histories in the world. Cyprus has a strategically important location in the Mediterranean. The island has remained under the control of many monarchs and kingdoms due to its geographical location and its commercial importance. Therefore, Cyprus has a great cultural mosaic. The empires with the administration of the island also had an important influence on the physical development of the city of Nicosia. The city of Nicosia has a history dating back to 7000-3000 BC (Mallinson, 2011).

The city of Nicosia is in the middle of Cyprus island, which is the third biggest island of Mediterranean located on its east (Atasoy, 2011). Nicosia has always been a hub due to its rich geographical resources and sheltered location. The city was founded around 2250 years ago. The first settlement established on where the current Nicosia is located is known to be Ledra/Lidra/Ledrae set up 150 m. above sea level. Although there are not any certain references about this era, the research findings indicated that Nicosia is settled on the area where the ancient city of Ledra was located (Gürkan 1996). The archeological excavations held to obtain data on the history of Nicosia revealed ruins at the south-southwestern part of Nicosia from early Chalcolithic Age (3900-2500BC), Bronze Age (2500–1050BC), Geometric (1050–750BC), Archaic (750-480BC), Classic (480-310BC), Hellenistic (310-30BC) and Roman (30BC- AD330). The ruins indicated that there are much older settlements than Ledra where Nicosia is located (Bağışkan, 2019). The historical settlement of Nicosia was formed during Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Period. At the end of AC XI. Century, the urban plans were initiated as Nicosia became the administrative and military center of Cyprus, and Orthodox churches were building during this period (Atun, 2006). Cyprus was recovered from the Byzantine Empire in 1191 by the British King Richard the Lionheart with the support of Guy de Lusignan and sold to the Templar Knights in 1192 for 100 thousand Gold Byzantine coins. With the new rulers of island, the knight chose Nicosia as the capital, built Catholic buildings under the influence of papacy and provided new structural, administrative and commercial reorganization. Templar Knights could not handle the rebellions resulting from new organization and returned the island to the King Richard by the end of 1192 (Bağışkan, 2019).

In the same period Lusignan bought Cyprus for 60 thousand Gold Byzantine coins from King Richard that launched the more than three-hundred-year rule of Lusignan Administration on the island (1192 – 1489) (Bağışkan, 2019). Nicosia was selected as their capital and they built the 9-mile-long city walls surrounding the city with 6 towers and 6 gates (Gürkan, 2006). Lusignans built churches, cathedrals, palaces, mansions and houses as well as green spaces with large orchards inside the walls. Thus, they contributed the commercial, cultural and social development of Nicosia, which left many traces for its visitors and travelers that was mentioned in numerous memoirs. The memoirs noted that Nicosia was a green city with large vegetable gardens and orchards (Köksaldı, 2020) and that a part of Kanlıdere/Pedieos river passed from the central Nicosia, which positively nurtured the green spaces of the city (Severis and Şevketoğlu, 2003).

Nicosia historical urban texture with its rich landscape showed significant formation and development during the Lusignan administration.

Venetians ruled the island between 1489 -1570 and they kept Nicosia as the capital. However, the development of city decelerated, and existing status was affected due to the intention of Venetians making Cyprus their transit business warehouse, and negative incidents like natural disasters and drought. Another factor that affected the urban development and progress of Nicosia was the defense approach of Venetians against Ottoman Empire that they destructed many buildings to downsize the city. During the destruction of 1567, many trees were cut down; monasteries, churches, palaces and houses were demolished; the route of Kanlıdere/Pedieos was changed out to the walls and a circular shaped 3-mile long new wall was built with eleven bastions (Flatro (Zeytinli-Kandil Söndüren), Loredano (Cevizli-Derviş-Söğütlü), Barbaro (Musalla), Quirini (Cephane), Mula (Zahra), Rokkas (Kaytaz Ağa) , Tripoli (Değirmen-Mezarlık), D' Avila (Kara İsmail), Kostanza (Bayraktar), Podokataro (Sazlı) and Graffa (Altun), and three gates (Paphos Gate (Porta di S. Domenico), Kyrenia Gate (Porta del Proveditore) and Famagusta Gate (Porta Giuliana)) (Figure 4.2), (Bağışkan, 2019). The first census data of Nicosia are not certain and eligible, yet they were generated from the census held in every four years. The city population was around 15-20 thousand between, 30 thousand in 1596-1597. The 1571 census data identified that 56 thousand people seek for shelter in the city (Erdoğdu, 2010; Cobham, 2013).

The Venetian Period slowed down the historical urban texture development, caused destruction and demolition where city landscape was majorly affected particularly to the change in Kanlıdere/Pedieos River route.

In 1570 with the rule of Ottoman Empire, Nicosia stayed as capital (1570-1878) that Ottomans built inns, hammams, mosques, fountains and houses, and supported the commercial and social development of city (Figure 4.3), (Gürkan, 1982). The whole city changed with new buildings that had Turkish architectural style, and courtyards, house-street, street-square connections were shaped with curved axis, narrow streets and plant elements. Travelers mentioned such change with bazaars, fruit trees flooded from courtyards and many fountains. On the other hand, some visitors indicated in their memoirs that destruction and disorder dominated the city (Köksaldı, 2020).

The Nicosia population from Ottoman Period was estimated as 2000 families in 1806 and 12 thousand in 1841 (Cobham, 2013; Erdoğru, 2010). The census held just before the island was taken over by the British administration in 1878 declared the city population as 10,874 (Erdoğru, 2010).

Nicosia, which was the capital of Ottoman Empire for around 308 years, showed major development in trade and social life with an improvement in urban development and landscape.

Nicosia stayed as the capital of British after they leased the island in 1878 from the Ottomans (1878-1960) with further development, transformation as the era of welfare and improvement. New architectural buildings were constructed; streets and squares were re-shaped and city expanded outside the walls with population increase (Gürkan, 2006). The first detailed and planned census was performed in this period, and the transport axis of city changed with the introduction of motor vehicles for the first time (Turkan, 2008). This change was considered as a major transformation for its residents. The visiting researchers noted in their memoirs that Nicosia was back then an organized city with its public open spaces and other architectural buildings (Köksaldı, 2020). Nicosia was a green city with rich green spaces and urban landscape at the courtyards of religious, administrative and households (Figure 4.4). Between the years of 1881 and 1960, censuses were held in every decade. Based on the first and last census in 1881 and 1960, the population was 11.513 and 45.940 respectively (Keshishian,1990).

The British Administration ended in 1960 majorly contributed to the commercial, social and cultural development of Nicosia. Moreover, the architectural buildings from this people influenced the formation of current historical texture. The landscape was considered more important than before for public open spaces so efforts were placed for its improvement.

The walled city/city center, in which the historical texture of Nicosia takes place, is still maintained as an open-air museum possessing a highly rich cultural heritage with its indoor and outdoor spaces and architectural works from various civilizations in the history of Cyprus (Lusignan, Venetian, Ottoman, British, Republic of Cyprus periods) (Gürkan, 2006).

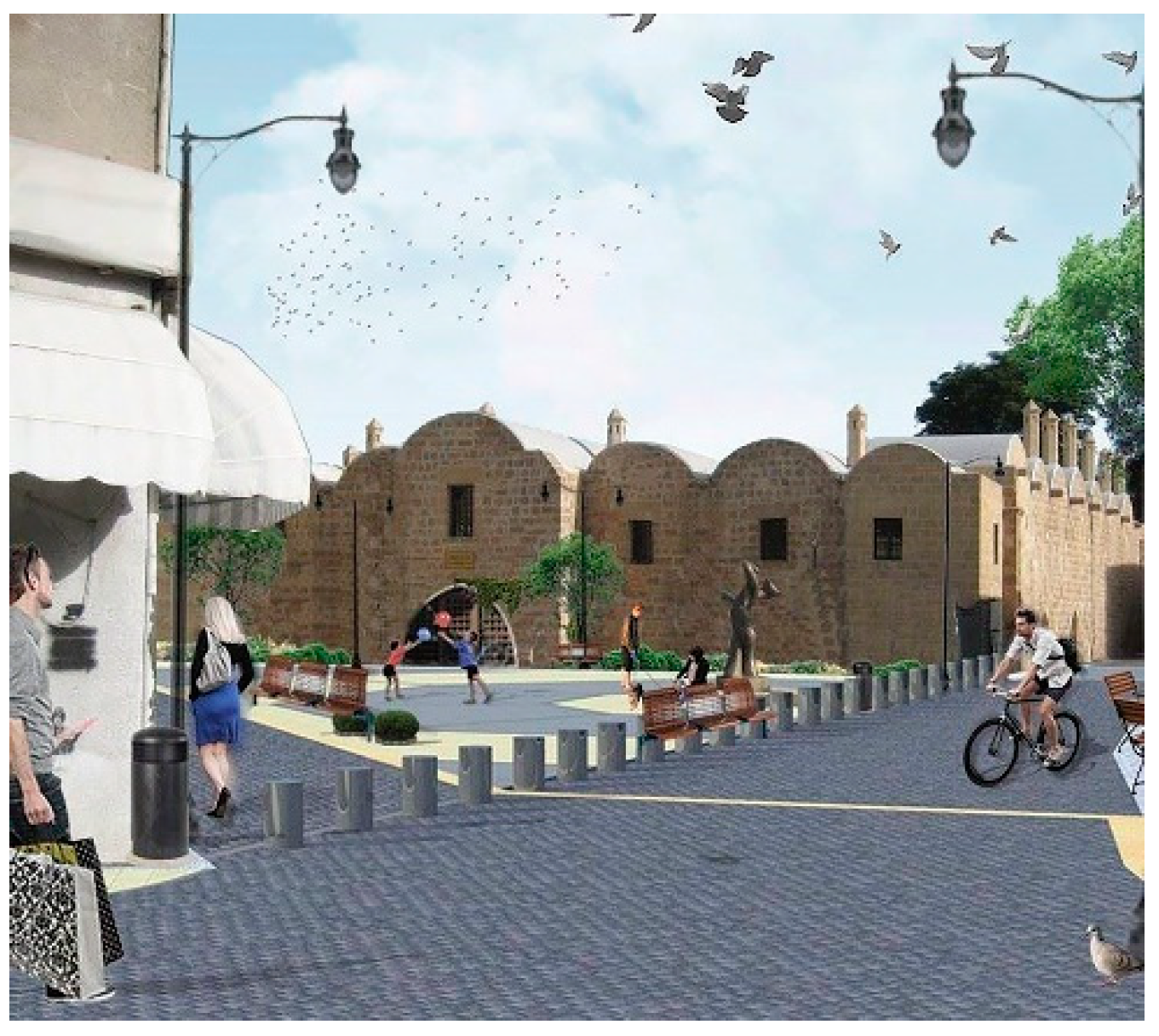

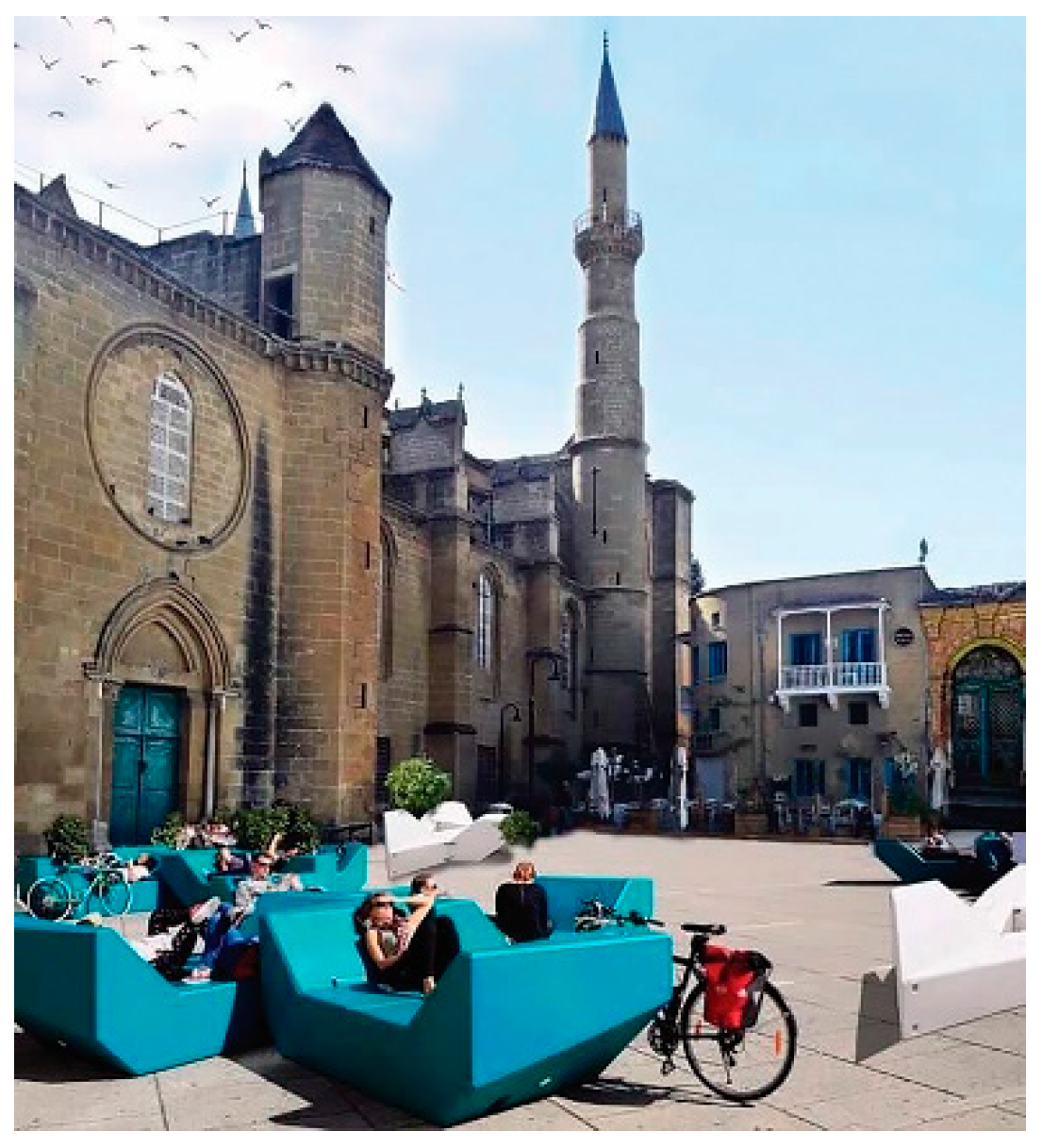

Public open spaces within the historical urban texture of Nicosia have always been intensely used as the centers of attraction for various aims. With the historical buildings in these public open spaces, the traditional culture of the city contributes to the use of both local people and visitors. It is observed that new urban furniture are added to these places as part of renovation and organization works in order to enhance the usability of public open spaces. Two important squares of walled city Nicosia can be examined for the compatibility of these urban furniture with the historical texture.

4. Findings & Discussion

4.1. Findings

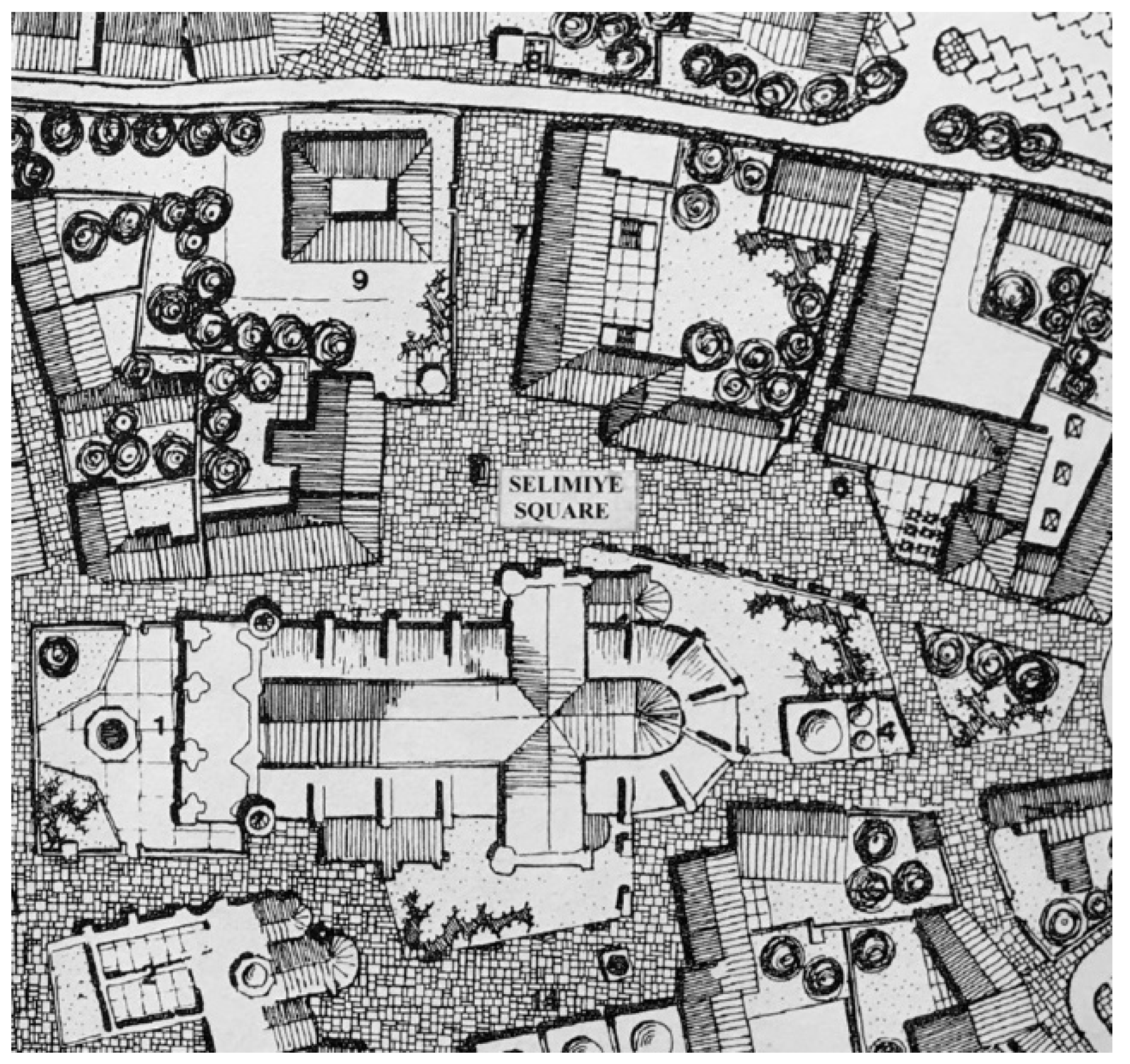

Data from the observations and examinations of the place in order to establish the use and compatibility of urban furniture in the historical Selimiye Square and Asmaaltı Square with the texture are explained below. (See

Table 4.1 and

Table 4.2).

Table 4.1.

Asmaaltı Square Urban Furniture Evaluation Form.

Table 4.1.

Asmaaltı Square Urban Furniture Evaluation Form.

Table 4.2.

Selimiye Square Urban Furniture Evaluation Form.

Table 4.2.

Selimiye Square Urban Furniture Evaluation Form.

Findings of the existing urban furniture at the Asmaaltı and Selimiye Square

Flooring Materials:

20x40cm. rectangular, yellow and grey cobblestones laid diagonally are used as flooring material in the center of Asmaaltı Square and surrounded by 10x20cm. Rectangular cobblestones, laid straight. Additionally, the front of shops in the west, and the front and surroundings of Kumarcılar Inn in the north are covered with 10cm. wide graveled concrete.

On the other hand, at Selimiye, rectangular shaped concrete cobblestones of 10x50cm are used as flooring, and laid alternately. Moreover, some parts of the north-west and south-east of the square are covered with a 100cm wide band of concrete with gravel of various sizes.

Seating Units:

The seating units used in Asmaaltı Square are made of concrete and wooden materials. The semi-circle banks of 60x150cm size with backs are made with horizontally lined wood, and the sides and side parts of the backs made of concrete. There are three seating units in the east of the square and two in the west, placed side by side with the possibility for seating a maximum of three people.

The two different types of seating units in Selimiye Square are made of concrete and wooden materials. Six sitting units for six people are placed towards the south-east and south-west sides of the square in groups of three. These sitting units are hexagonally shaped, with concrete backs and stands. 150cm long sitting parts are made of wooden materials 18x30cm in size, and arranged side by side. The second type of benches sit two people each and that four of them are placed around the monument in the north-east of the square. These are 30x150cm in size, rectangular formed, concrete stands without backing, and the sitting parts are made of wooden decks laid side by side.

Lighting Elements:

The pole type lighting elements used in Asmaaltı Square are made of steel material. Some of these elements have a single armature, while others have three. The lighting poles are about 500cm. in height, and they are placed as one in the west of the square, and three in the east, 800cm. apart from each other. Additionally, electric cables with led lamps attached on them are attached to lighting poles crosswise.

The lighting elements in Selimiye Square have single armature and about 500cm high, made of steel material and dyed black. Three of these lighting elements are placed in a triangular form in the south-east of the square, six of them are located side by side in the north-west, and two are placed in the north of the square. In addition to these, there are movable led projectors in aluminum cases placed on the ground with 300cm intervals around the Selimiye Mosque. Other lighting elements in the square are five led lamps placed on the south side of Küçük Mehmet Buildings (Yunus Emre Institute at present) which is the north of the square. These lamps are used to illuminate the outer façade of the building, but they also contribute to illuminating the square as well.

Boundary Elements:

Safety of Asmaaltı Square is ensured by a vertical mobile hydraulic mushroom barrier system, made with modern technology to specify the borders and control the vehicle entrance hours to the square. The shell of the 50cm. high boundary elements are made of stainless steel and the top cover is aluminum material. These cylindrical shaped elements are lined at the meeting points of the square with the adjoining streets at intervals of 160cm.

The 30cm. high boundary elements in Selimiye Square are made of black steel in a cylindrical form with flat tops. They are placed side by side, 60cm. apart from each other on the conjunction points of streets, which surround the square.

Bins:

Two different types of bins are used in Asmaaltı Square. The baskets of both types are made of metal sheets and black oven-dried pipes, with the inner bucket made of galvanized metal. The first type litter bucket has forged cast iron legs, and the other type, fixed onto concrete, has plastic covers. A total of five bins of 110cm. in height, are placed in the east and west diagonally.

Some of the bins used in Selimiye Square are made of white painted concrete, including their cylindrical formed carrier systems. The inner buckets are 60cm. in height and made of galvanized sheets. Four of these bins of approximately 90cm height are placed towards the south-east of the square, side by side, and one is placed towards the north-east. The other type of litter bins is 120cm. in height, rectangular in shape, made of green colored plastic material with metal handles, and have wheels as well. There are two of these bins in the south-east of the square.

Flower Bedss:

The flower beds used in Asmaaltı Square are circular shaped concrete pots, and square shaped white plastic pots. There are three concrete pots, 60cm. in height, lined in the east of the square, and four plastic pots, 40cm. in height, in the north, placed side by side.

Some of the flower beds used in Selimiye Square are flower cases rectangular in shape, have legs, and are made of wooden materials approximately 40x120cm. in size. Other flower beds are gray and brown plastic pots, square or circular in form, about 30 and 50cm. in height. These flower beds are randomly placed by the cafes and restaurants that are in the square.

There is an approximately 30 square meter landscape area to the east of the Fighters Monument, surrounded by a wall made of cut stone material and covered with an 80cm high concrete coping. This landscape area has a shape created by superposing the north-east and south-west corners of two entangled rectangular shaped forms directed to the east and west. There are 2 Cupressus trees, 1 Melia Azedarach tree, 1 Ficus Benjamina, 1 Nerium oleander in this landscape area. There is a Date tree (Phoenix) in another landscape area to the east of the monument, which is about 6 square meters, rectangular in shape, covered with cut stone material, 90cm in height and covered with concrete coping.

Top cover elements:

The top cover elements in Asmaaltı Square are four umbrellas 4x4m. in size, made of polyester fabric of yellow, red, and blue colors, on aluminum structures about 300cm. in height. These umbrellas standing on top of aluminum stands reinforced with concrete parquet, are placed at the center of the square in a triangular form.

The two top cover elements in Selimiye Square belong to the restaurant in the east side of the square. These elements are made of beige colored acrylic textile canvas. They each have two approximately 300cm. high vertical steel carriers with wheels. There are horizontal carriers between them that have a system of movable elements mounted in both ways to enable opening and shutting.

Bookshelves:

Two book boxes are placed at Asmaaltı Square. They are rectangular in shape, with wooden sides and inner shelves and glass covers, and have iron stands. The stands have two different heights, 90cm. and 70cm. The book boxes are 45cm. in width, 50cm. in height, and 30cm. in depth, and are placed side by side in the west of the square.

Bike parking station:

The bicycle parking station in the north-west of Selimiye Square, with fifteen bike capacity, is placed by the Nicosia Turkish Municipality with Velespeed (Bicycle Sharing System). The floor of the station has galvanized sheets and bicycle parking slots are made of hard plastic material.

Signs and Boards:

The information board at the south-east of Selimiye Square showing that the square is closed for vehicle traffic, but open to pedestrians and cyclists, is made by placing a circular galvanized sheet on a metal pole about 300cm. in height. The information panel with the map of the Nicosia sightseeing train is at the north-east of the square. This panel is made of hard plastic material 80x110cm in size. The bearings are metal poles 220cm in height. Additionally, there is an information board at the north-west of the square, providing information about the Nicosia Turkish Municipality with a charging point for wheelchairs. This urban furniture is made of metal with its exterior painted with durable polyester based electrostatic powder paint, and its shade is of galvanized sheet.

Artistic Objects:

The statue placed in the center of Asmaaltı Square as an artistic object is 200cm. in height and reflects botanic and human figures. Its internal material is plaster, while the outside is polyester. During an interview with Ceylan Dimililer, the artist who designed the statue, she stated that she was inspired by the grapevine which was there in the past, and from the folk dance “Sarhoş Zeybeği” (Drunk’s dance), an aspect of Cypriot culture.

Fighters Monument is in the east of Selimiye Square on an uneven geometry, approximately 50 square meters. It is surrounded by cut stone material, about 90cm in height and is accessed by 4 rises from the level of the square. The monument is made of a crescent shaped piece of wall on its west side, made of natural stone material, 200cm. in height. The eastern part of the monument is a castle shaped structure in a cylindrical form, made of natural stone material that 150cm in height. A brass Fighters emblem is placed on the west façade of the monument, together with an information panel engraved on natural stone. There are flag poles about 800cm in height on the north and south of monument. There is also one Ficus Elastica, and one Melia Azedarach trees. Fighters Monument was built in 1967 giving the square the function of military ceremonial place (Turkan and Özburak, 2018).

5. Discussion

A number of field studies were conducted at Asmaaltı and Selimiye squares in the walled city of Nicosia with the aim of identifying the compatibility of urban furniture in public open spaces within historical city textures. The assessments were performed based on the findings about material, style, and functionality of the urban furniture (sitting elements, litter bins, lighting elements, boundary elements, artistic objects, bike parking stations, flower beds, bookshelves, signs and information panels) in these places. (See

Table 4.1 and

Table 4.2).

Concrete flooring materials and ground paving at both squares, as a contemporary construction material, are incompatible with the characteristics of historical texture. Additionally, the dents in parts of Selimiye Square obstruct the pedestrian traffic and cause visual pollution.

Seating units are made of a combination of concrete and wooden materials at both squares. Although wooden details are in harmony with the texture, extensive use of concrete material creates a contradiction with the historical character of the texture. The banks, which are nonfunctional because of their sizes and shapes, are damaged and worn out due to the physical environmental effects, and lack of maintenance.

The materials of lighting elements at both squares are compatible with the historical texture, however, their forms cause a contradiction, and they are inadequate in lighting. The projectors at Selimiye Square show a harmony with the texture, and they especially contribute to lighten the Selimiye Mosque. However, most of these elements, and pole type lighting elements are either broken or dismantled, hence, nonfunctional.

The materials and forms of the boundary elements at Asmaaltı Square are made with contemporary technology that contradicts with the historical texture. Although the boundary elements in Selimiye Square are compatible with the texture in both material and form, they create visual pollution due to the lack of maintenance.

The bins at Asmaaltı Square do not create a unison because of their different forms. Also, their functionality is insufficient because of their numbers and lack of maintenance.

The flower beds placed at both squares create an incompatibility because they are mostly made of contemporary materials, and they are made in different shapes, sizes, and colors. The fact that flower pots are mostly selected for vegetation, makes it insufficient to meet the need for creating green spaces, and they do not have functionality.

The top cover elements, that belong to restaurants at both squares, contradict with the texture since they are not compatible with the characteristics of the texture and they are placed randomly.

The bookshelves at Asmaaltı Square are compatible with the texture with their material. However, their shapes negatively affect their functionality. Moreover, the lack of maintenance caused an extensive damage on the bookshelves.

The bike parking station, made of contemporary materials, is incompatible with the texture of Selimiye Square. The station, which is not any different from those placed outside the walled city, shows that the historical city texture was not considered enough in that regard.

The information panels at Selimiye Square are not in harmony with the texture because of their materials and are functionally insufficient. The information sign about the sightseeing train is made with materials compatible with the texture and is functional. The sign where municipality information is provided as well as serving as a wheelchair charging station, is incompatible with the texture due to its contemporary material. Moreover, it fails to function properly due to the lack of maintenance.

Artistic objects like the statue in Asmaaltı Square creates unity with the texture with its theme about the city’s cultural history. However, the statue was greatly damaged because of vandalism, and the renovation works disrupted its form. Moreover, the lack of landscape at the statue does not provide any means for the people to understand the artwork making it ineffective.

The stone, a traditional materials, is used for the construction of monument at Selimiye Square which is overall compatible with the texture. However, the lack of essential organization, maintenance and cleaning around the monument and in the landscape areas to the east and south result in visual and environmental pollution, and damage the historical importance of the monument, which is a symbol of the square.