1. Introduction

This case study describes the COVID-19 mitigation measures undertaken by an independent school system, Avenues: The World School, and how their school population’s experience with COVID-19 differed from the New York City metropolitan area. While it is impossible to determine with certainty that the school’s package of measures alone led to a more favorable case rate, given the scarcity of data about COVID-19 mitigation measures undertaken by schools, this case study should prove helpful in comparing different school systems, as well as in providing future insights for pandemic planning initiatives surrounding schools.

The Avenues school system has multiple campuses, but this paper specifically focuses on the interventions undertaken by the New York City campus from March 2020 to January 2023. The New York City campus is a 10-year-old independent school, with 16 grades encompassing students aged 2 to 18, with 1,704 students. Avenues kept records of all intervention measures taken throughout the 2020-21, 2021-22, and the ongoing 2022-23 academic years, with multiple forms of measurement taken to gain real-time information on how the intervention measures were working; as such, the school provides multiple examples of how to respond to infectious disease threats. We examine IAQ measures, testing and tracing mechanisms, masking, ventilation procedures, and other measures. Our findings can help develop IAQ guidelines for public spaces, as well as long-term strategies for reopening access to education during future epidemics and pandemics.

This work adds to the emerging picture of how COVID-19 affected the health and education of children. The COVID-19 pandemic led to disruptions in access to education and public school-based services in the United States and around the world [

1,

2,

3,

4] . Many areas of the United States instituted lockdowns and school closures as cases began to rise, but school closures, virtual learning, re-openings, and COVID-19 mitigation measures differed from one district to another for both public and private schools, even within the same state. New York’s state government closed its public schools in mid-March 2020 following the rapid rise in COVID-19 cases in the initial stages of the pandemic, and by May 1 moved to full closure for the remainder of the academic year. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio also ordered the city’s schools to close in mid-March 2020 and decided to keep them closed through the academic year in mid-April 2020, prior to state closure orders. New York City, while technically operating under the New York state government, controlled much of its own pandemic policy for education [

5,

6,

7].

Schools in the United States, and by extension in New York state, used highly variable mitigation measures and were subject to national and state guidance and restrictions on reopening, including measures required for schools to successfully reopen. Universal masking was often implemented, often with specific mask grade requirements (N95, KN95, surgical grade) to improve efficacy [

8]. Testing programs at schools varied wildly, from requiring a negative antigen test to return to school, to school-mandated polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and antigen testing multiple days a week for the entire school population. Indoor air measures often included deploying indoor air purifiers, upgrading HVAC filters to higher MERV grades, installing UV germicidal irradiation, improving window and door ventilation, and implementing social distancing measures. Since the onset of COVID-19, we have learned that HEPA filters, natural ventilation, and more sophisticated indoor ventilation systems are effective mechanisms for decreasing airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 [

9,

10]. While these interventions are most effective when combined with mask-wearing, proper indoor air quality (IAQ) maintenance alone, when accurately measured and consistently implemented, can act as a sufficient intervention to decrease SARS-CoV-2 transmission [

8,

9,

11,

12,

13]. Vaccination became required after a certain period for many schools, first for teachers and adult staff, and then for children once COVID-19 vaccines were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for children. Most of these broader measures have been demonstrated to reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Multiple papers have suggested that without robust mitigation measures, COVID-19 prevalence in local communities could accelerate through the reopening of schools. Because COVID-19 poses relatively fewer risks to the health of children compared to adults, it was first believed that schools would not significantly contribute to community transmission. However, research has since indicated that school closures are associated with a reduction in R-nought values and that the prevalence of infection among different age groups increases after school reopenings, particularly after short-term school holidays [

14,

15]. A recent systematic review found that measures fell into 4 major categories: “measures reducing the opportunity for contacts, measures making contacts safer, surveillance and response measures, and multicomponent measures”[

15]. The combination of broad measures implemented in school settings proves more effective; however, specific studies disentangling various combinations of measures and quantifying the efficacy of individual interventions were not found.

One modeling study conducted in Indiana, United States, found through an agent-based model that schools with multiple mitigation measures often maintained lower levels of transmission, close to that of a scenario with fully remote learning; the model accurately represented the effect that school reopenings had on Indiana SARS-CoV-2 transmission, with the worst impacts being on local communities and adult staff [

16]. A case study of community-based school reopening in Seoul, Korea, described the implementation of multiple layered safety measures, including masking, frequent disinfection, desk spacing, thermal imaging, improved ventilation measures, and active case monitoring[

17]. A similar case study conducted in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, examined a pool testing strategy for PCR testing, finding that pool testing, in combination with measures such as masking, increased hygiene, and contact mitigation, could be an effective reopening strategy, due to the very low prevalence rate found in widespread testing of 1,500 individuals[

18]. Additionally, a study examining the association between ventilation and SARS-CoV-2 transmission in Marche, Italy, found that with mechanical ventilation, the relative risk of infection decreased by at least 74%, which validated the need for high IAQ to reduce the risk of airborne disease transmission[

19].

2. Avenues Reopening Strategies for Student, Faculty, and Staff Safety

2.1. 2020–2021 School Year

Students were placed into self-contained classrooms with a no-mixing, pod-based strategy of roughly 18 students per pod; students would not mix with students or teachers outside their designated pod to minimize intermingling, limit onward transmission, and enable better contact tracing. The People and Culture Department, Avenues’ department responsible for staff hiring and management, changed faculty and staff job responsibilities so there would be no mixing of students across pods, which meant that faculty teaching classes that catered to multiple levels (e.g., math, science) instead taught virtually, with students from multiple sections attending the same class virtually without mixing physically.

Universal masking requirements, arrival checks intended to prevent symptomatic individuals from entering the building, and COVID-19 testing measures were implemented for all students, faculty, and staff. Point-of-care testing on campus was administered by health office or operations team members trained in administering rapid tests. Weekly PCR tests were swabbed at home and brought to school for testing in pools.

All students, faculty, and staff also needed to clear a daily COVID-19 screening through an app developed by the school known as QT, which would permit them to enter the building. This app was originally designed as a geo-fence feature to would notify the school when a parent was within a certain radius of the school for student pick-up, reducing unnecessary congestion and student density at previously high-traffic times, but was eventually modified to act as an entrance app through COVID-19 symptom screening. Answers that indicated a possibility of COVID-19 infection generated a red square, while cleared students received a green square with a QR code; without the green QR code, entry to the school was not possible. Along with the daily COVID-19 screening, temperature checks with thermal scanners were conducted, and movement routes within the building were monitored to moderate student traffic.

Avenues attempted to secure point-of-care testing in the early phase of the pandemic; however in the earliest days, many companies and testing kits had not yet reached the market or successfully received Emergency Use Authorization from the FDA. To quickly secure reliable and high-quality testing, Avenues applied for a Limited-Service Laboratory License with the New York State Department of Health to administer tests on school grounds. The school implemented a hybrid approach to testing, with weekly pooled PCR test screening for each member of the on-campus population from October 2020 onwards. Over 45,000 COVID-19 tests were administered throughout the 2020-21 school year at Avenues NYC, using both rapid and PCR testing. The rapid tests included the Abbott ID Now (molecular), Cue Health (molecular nucleic acid amplification), Abbott Binax Now (antigen), and BD Veritor (antigen). The pooled PCR tests used anterior nasal swabs collected at home and brought to campus and collected in pools. Pools were sent to JCMA’s CLIA-certified laboratory partners for analysis.

2.1.1. Test-to-Stay

Using the above testing infrastructure, Avenues NYC implemented a test-to-stay system, wherein students who were exposed to COVID-19 would be allowed to take a rapid antigen test daily, and if tests remained negative, they could continue attending school. Inconclusive or positive tests would result in the student staying at home, with return to school conditional on symptom resolution and negative test results. Families could choose to keep students home, but the school was not offering remote education unless an entire class was in quarantine. Because of the test-to-stay policies, Avenues NYC calculated that more than 3,800 instructional days were saved amongst all its exposed students, as students were able to remain in school on those days rather than losing them to quarantine. This calculation does not take into account the instructional days that were lost due to isolation or infection.

2.1.2. Contact Tracing

The school developed and piloted a process to identify every individual's location, as well as their proximity to others, through the usage of Bluetooth cards issued to each student and faculty/staff member. Bluetooth signals from each card pinged Wi-Fi access points throughout the facility, which allowed for the determination of who was in a classroom and for how long. The accuracy of this method did not suffice for contact tracing using the 6-foot rule established by the CDC as the minimum distance considered to be not “close contact”[

22], but it was helpful to manage population density in classrooms and common spaces.

2.1.3. Indoor Air Quality

Avenues NYC considered IAQ a high-priority improvement and modification strategy to prevent transmission of cases, and the school continually updated its air quality improvement measures throughout the year to lower the potential for airborne transmission.

Prior to the school's reopening in September 2020, several upgrades and modifications were made to the indoor air ventilation system at Avenues NYC. In May 2020, Avenues measured the air changes per hour (ACH) to meet the standard of 5-6 ACH recommended by Harvard Healthy Buildings for excellent air; much of the building already met this standard, using Airthings ViewPlus sensors installed in multiple locations; 100 sensors were installed. FEND nasal misters by Sensory Cloud[

20] were piloted and eventually incorporated as an additional layer of protection in the upper age divisions.

Avenues hired Underwriter Laboratories, Healthy Buildings Division in July 2020 to conduct an indoor environmental quality assessment and audit to test air, water, and surface quality and evaluate cleaning procedures throughout the building. The school made all recommended changes and received a certificate establishing that its facilities met the safety requirements for reopening. The main outside air handlers had two levels of filtration for outside air: an initial MERV7 or MERV8 pre-filter followed by a MERV14 or MERV15 filter. Indoor return air filters were all upgraded to MERV8 or higher. These were the maximum levels of filters that the internal systems could handle without undue pressure drops or harm to the system. They also installed bi-polar ionization, though that has been demonstrated in large-scale tests to not be beneficial[

23]. At the end of the school year, in June 2021, indoor air-quality sensors were purchased and piloted.

Vaccination COVID-19 vaccines became widely available to individuals over the age of 16 in the United States in the spring of 2021. After vaccines became available to educational workers through the state of New York in January 2021, Avenues implemented a vaccine mandate for all adults and students aged 12-18 to be fully vaccinated by the start of the 2021-2022 academic year.

2.2. 2021-2022 School Year

Many of the same protocols implemented in the 2020-21 school year were continued into the next year, with some modifications added due to changing SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and knowledge about vaccination and transmission mitigation methods. For example, modifications included the elimination of temperature-taking at the door, re-mixing vaccinated students in grades 7-12 with specialty classes, resuming in-person education, stopping weekly testing for faculty, and resuming athletics programs for Upper Division students. In grades 7-12, data were not collected by pods but rather by grade since vaccination had become widely available for students over the age of 12.

Some new protocols shifted focus towards improving indoor environmental quality by installing portable HEPA filters and upper room germicidal irradiation in crucial spaces, such as the gymnasium, cafeteria, health and physical movement areas, theaters, music rooms, and health office. A FAR UV rollout for all classrooms was finished by December of 2022. Additionally, Avenues joined the International Well Building Institute and is planning to pursue WELL building certification and has also received certification from RESET at the High-Performance Level in its HQ office.

2.2.1. Outcomes

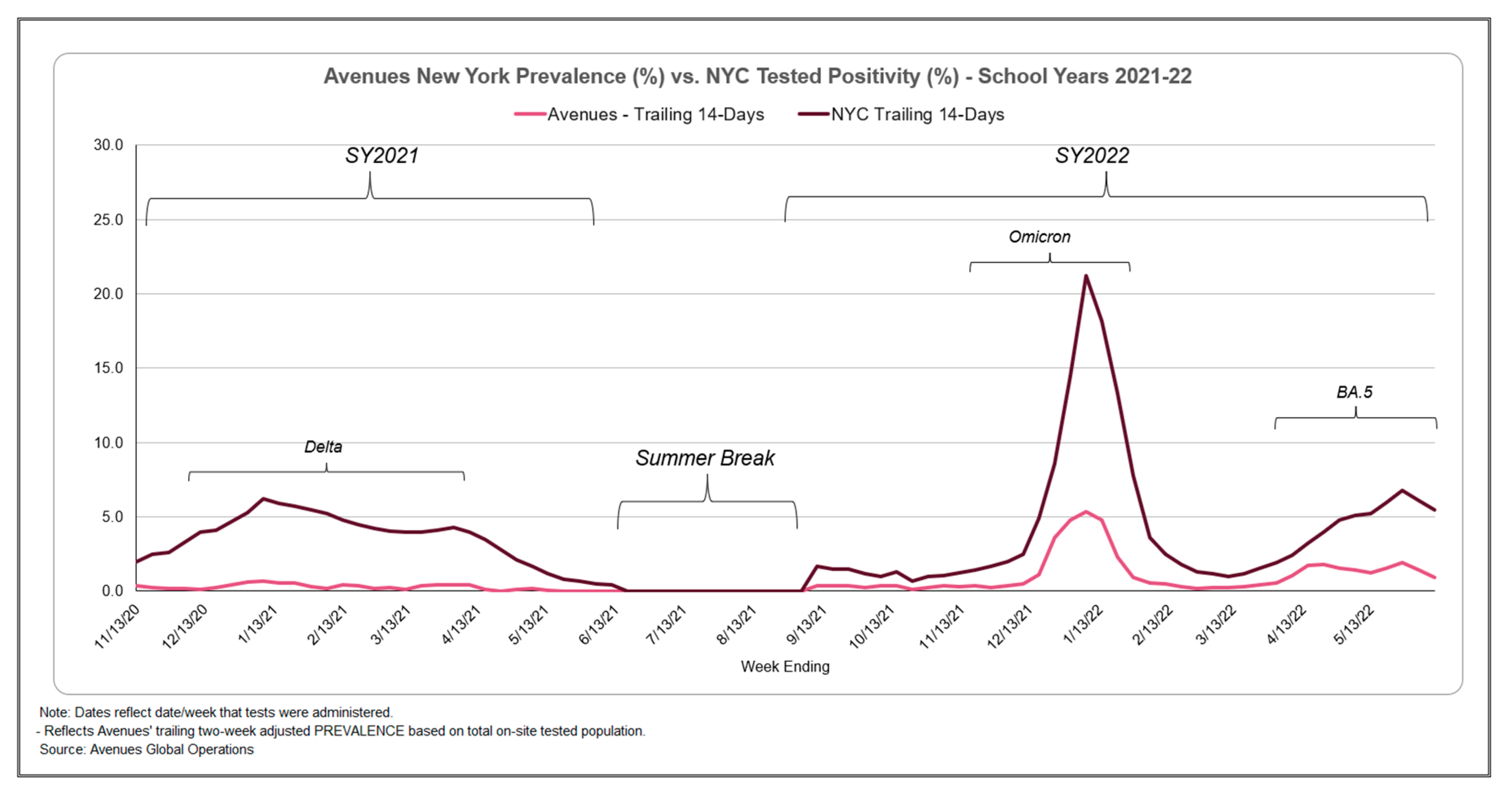

We observed a difference in prevalence of COVID-19 cases between Avenues NYC and New York City over the school years of 2020-21 and 2021-22. When reporting began, Avenues had a significantly lower peak in prevalence over the spring of 2021 while still following the pattern of increased prevalence rate. No cases were reported at Avenues from mid-June to early September due to summer vacation closure. However, when the academic year of 2021-2022 began, similar patterns repeated from the end of the previous academic year. Between December 2021 to February 2022, New York City reported a test positivity rate of 21%, almost 4 times higher than Avenues’ reported prevalence rate of ~5%.

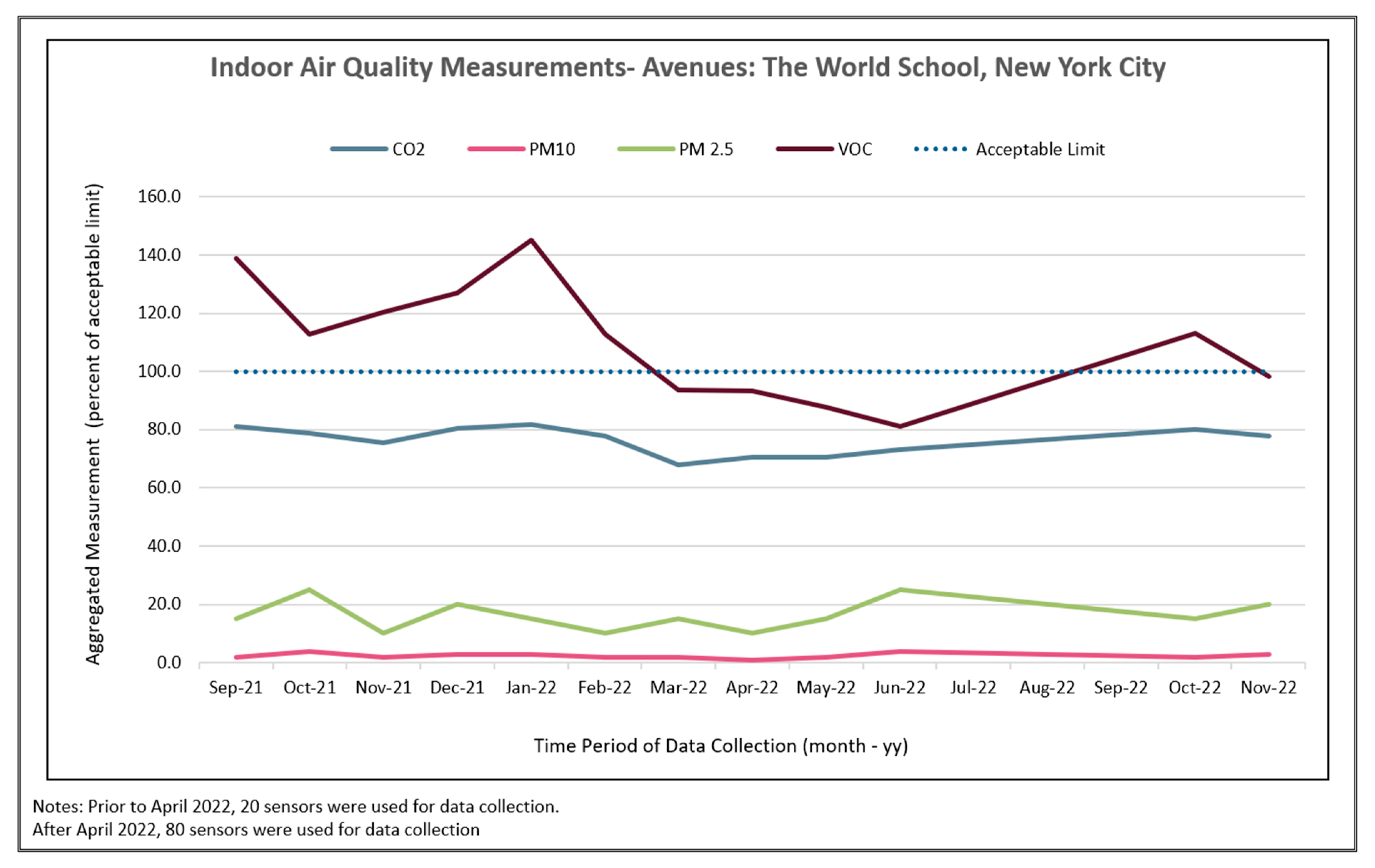

2.2.2. Indoor Air Quality Readings

Figure III represents more than a year of ambient IAQ data, with measurements aggregated over the times of day that students and staff were present at Avenues NYC, thereby showing information during peak usage times. PM10 and PM2.5 levels are often present at less than or equal to 20% of the upper safe limit, indicating very consistently safe levels of PM10 and PM2.5 over the year. Low PM10 and PM2.5 levels are a mark of filter efficacy since the air filtration systems are responsible for reducing the presence of these particles in the air. CO2 levels are also present at roughly 80% of the lower safe limit, indicating that ventilation measures may be working well over a prolonged period. Volatile organic compound levels, or VOC levels, often straddle the lower safe limit, with instructions provided to investigate VOC levels above the lower safe limit. Avenues NYC is actively engaged in tracking and identifying which VOCs are present in these rooms to determine how best to reduce those VOC levels[

25]. Current results indicate that the most common classroom total VOCs (ethanol, isopropanol, and acetone) were primarily associated with personal care products, such as perfume/cologne, hand sanitizer, and nail care products.

Figure 2.

infection and transmission, used by Avenues in communications documents.

Figure 2.

infection and transmission, used by Avenues in communications documents.

Figure 14.

day trailing prevalence across schools compared to New York City's 14-day trailing tested positivity rate[

24] through the school years of 2020–21 and 2021–22.

Figure 14.

day trailing prevalence across schools compared to New York City's 14-day trailing tested positivity rate[

24] through the school years of 2020–21 and 2021–22.

Figure 2021.

to November 2022, collected by Airthings ViewPlus sensors. Measurements are aggregated from multiple locations, with measurements collected during school operational hours. Measurements are calculated as percent values of acceptable upper limits[

25] with upper limit represented as 100%. Measures include carbon dioxide, PM10, PM2.5, and volatile organic chemical measurements.

Figure 2021.

to November 2022, collected by Airthings ViewPlus sensors. Measurements are aggregated from multiple locations, with measurements collected during school operational hours. Measurements are calculated as percent values of acceptable upper limits[

25] with upper limit represented as 100%. Measures include carbon dioxide, PM10, PM2.5, and volatile organic chemical measurements.

| Focus Area |

Summary of Strategies Implemented |

Years Implemented |

| Testing |

Weekly full population pooled PCR testing with JCM Analytics testing, sourced Point of Contact (POC) molecular and antigen tests for symptomatic individuals or missed weekly testing |

2020-2021 |

| Weekly pooled PCR testing for unvaccinated students only, limited on-site testing to screen symptomatic students/staff |

2021-2022 |

| Vaccines |

Required vaccination by July 1, 2021, for staff and faculty |

2020-2021 |

| |

Required all adults and students aged 16+ to be vaccinated by start of school year; required all students 12+ to be vaccinated by November 1, 2021 |

2021-2022 |

| |

Required vaccines for all adults and students aged 5+ by October 15, 2022, and honored valid medical exemptions |

2022-2023 |

| Symptom Tracking |

Daily attestation that symptoms were checked and not present, and that individuals did not have close contact with positive case via QT app and temperature checks at entry |

2020-2021 |

| Relaxed full symptom tracking to emphasize loss of taste and smell, fever, or new onset cough. Stopped taking temperatures at entry |

2021-2022 |

| Masking and Social Distancing |

Mandatory masking and social distancing required. Avenues procured multi-layered masks for students and staff |

2020-2021 |

| Mandatory masking for majority of the year, eventually moved to mask recommended for younger-aged groups per city requirements |

2021-2022 |

| Podding |

All students podded into groups of roughly 18 students and no-mixing policy enacted |

2020-2021 |

| Podding continued for children aged 12 and below (up to Grade 6) in Lower Division; Upper Division began mixing in September 2021 |

2021-2022 |

| Quarantine and Return to School |

New onset of symptoms required person to quarantine, resolve symptoms without medication, and test negative for COVID through molecular NAAT test

Quarantine duration was 10 days

Negative molecular NAAT test (proof required) after holiday break at Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Spring Break |

2020-2021 |

Implemented Test & Stay in Lower Division, where only positive students required to isolate, and remaining close contacts were tested for 5 consecutive days on campus. Students could attend if they tested negative

Quarantines were reduced to 5 days, but a negative rapid antigen test on Day 5 and Day 6 with 24 hours between, as well as completely resolved symptoms, were required

Negative test (honor system) required to start school year, and on return from holiday break at Christmas

Students were given tests to take home during case increase periods, and self-administered those tests under parental supervision |

2021-2022 |

If new COVID-19 symptoms arise, the individual should stay home and take rapid antigen test. If negative, and if student is feeling fine, take a second test, and return if negative

Positive COVID-19 case must isolate for 5 days and may return on Day 6 if both Day 5 and Day 6 tests are negative. If still positive, continue to test and only return when negative or after 10 days, whichever happens first |

2022-2023 |

| Close Contacts |

Close contact is defined as anyone within 6 feet for 10 or more minutes cumulatively during the previous 24 hours, with all household members additionally considered close contacts. All students in the same self-contained classroom as a positive case considered a close contact |

2020-2021 |

All podded classmates still considered close contacts, but Test and Stay strategy results in close contacts not needing to quarantine

Unvaccinated close contacts with a household exposure still required to quarantine for 5 days |

2021-2022 |

No requirement for vaccinated close contacts to quarantine

For Grades Small World-5, unvaccinated students who are close contacts must test Days 1 and 4, with recommendation for vaccinated students to test as well

If household member is positive, asked that asymptomatic individuals test on Days 1, 3, and 5 and only come to school if negative |

2022-2023 |

| Contact Tracing and Communication |

Deployed Bluetooth lanyard trackers to support contact tracing; proved less accurate and more administratively burdensome, so switched to relying more heavily on student schedules in Lower Division. Close contacts were identified in the Upper Division based on class schedules and interviews with the infected individual

Communicated with all classroom parents and faculty |

2020-2021 |

Conducted individual contact tracing for all cases; notified pod and other identified close contacts for grades SW-5. Conducted individual contact tracing in Upper Division and notified colleagues and close contacts

Reported cases in weekly bulletin |

2021-2022 |

Only communicate in self-contained classrooms

No longer communicating colleague or Upper Division cases due to vaccination coverage levels, and contact tracing no longer practical with class mixing reinstated |

2022-2023 |

| Air Quality Interventions |

Upgraded filters, assessed air changes per hour (ACH), and implemented needlepoint bipolar ionization at the head-end and in distributed ductwork |

2020-2021 |

Added HEPA filters to all classrooms, piloted FEND nasal misters[20] in Upper Division

Began piloting IAQ monitors and selected Airthings as sensor brand

Achieved RESET certification for IAQ in HQ admin offices

Implemented ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI) in cafeteria, movement areas, gym areas, choral classrooms, and Black Box Theater (FAR UV[21]) |

2021-2022 |

Distributed 400 FEND nasal misters to all faculty and staff and provided coupon code for replenishment.

Installed FAR UV in all classrooms, completed implementation in December 2022 |

2022-2023 |

2.2.3. Parent/Guardian Response

The educational and government responses to COVID-19, particularly concerning closures, reopening, and safety measures, have become a source of political contention, with many school boards under fire for both adhering to and disregarding COVID-19 mitigation measures[

26]. Avenues regularly sent parents surveys asking for feedback on school standard operating procedures, with many parents expressing their views about COVID-19 safety procedures with candor. Between 2021 and 2022, 3 individual surveys were sent out, with most parents supporting school safety protocols.

Parents praised the pragmaticism and sensibility of COVID-19 policies and the school’s frequent communication with parents, mainly when policies or implementation methods changed. Most responses from parents related to COVID-19 policies were positive, with scores of 4/5 or 5/5 in a rating process. Positive parent comments (designated by a score of 4 or 5) included praise for flexible schooling options, protocols to keep the campus open, and the school “proactively finding ways to make school more ‘normal.’” One parent noted that “Avenues is always the first school to adopt pragmatic and sensible COVID policies…I always cite this to friends as something we are so happy about.” Many parents noted the positive impact these measures had on their children, including a lack of excessive worry among their children about the pandemic. Transparent communication and the fluidity of protocol adaptations were noted many times as program strengths, as the COVID-19 pandemic evolved.

While many parents provided positive feedback, some parents had more neutral or negative feedback, designated by scores of 1-3 on the parent surveys. Negative comments from parents included their wish for Avenues to remove masking mandates for young children, due to lower rates of severe COVID-19 among young children and the belief that “mandates may be harming our children by impeding language and emotional development.” Additionally, some parents felt that communications about testing policies were unclear, with limited follow-up after questions. Some neutral comments specifically included the desire to end mask mandates, which is representative of parents who did not fully trust the existing COVID-19 mitigation measures. Interestingly, some parents believed that Avenues did not go far enough, with one parent stating they were “really disappointed that Avenues is not running a vaccine drive for the 5–11-year-old age group.” Other parents specified their comfort with fully approved vaccines, followed with a request that students not be required to get vaccines that only have emergency use authorization. Parents across the United States received COVID-19 policies in similarly variable ways, with such policies being a polarizing topic addressed in many school districts[

26].

3. Conclusions

During the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, as well as during future epidemics and pandemics, schools need support to engage in and use policies that will allow them to remain open as much as possible[

27]. The learning loss endured by students during COVID-related school closures and virtual, asynchronous education has caused significant backsliding among children in the United States [

1,

4], and the positive impact of in-person education has become clear[

28,

29]. In-depth guidelines developed now, using various school case studies documenting COVID-19 mitigation measures, can provide valuable evidence for designing policies for schools to prepare and remain open during future crises, including future disease outbreaks.

In this study, we have discussed the several types of COVID-19 mitigation measures accessible and usable by a single private school, Avenues NYC, as well as whether implementation of these measures show association with decreased COVID-19 prevalence when compared to COVID-19 test positivity in New York City as a whole. While individual measures cannot be disaggregated and examined for efficacy, the combination of measures implemented at Avenues NYC during the pandemic can be associated with reduced case COVID-19 prevalence at this school but cannot be causally linked. Additionally, ongoing research indicates that improvement of IAQ could benefit students not only during an active pandemic but also reduce illness incidences year-round [

12] due to the association of indoor air pollutants with poorer respiratory health outcomes in children[

30,

31,

32,

33]. Moreover, the school demonstrated success in the essential step of ensuring that open lines of communication were maintained with the school community, particularly parents, ensuring long-term buy-in on and compliance with the school’s policies.

Recommendations that might reduce future respiratory disease case rates in schools include implementing more robust case surveillance systems and deploying technological innovations around contact tracing within buildings to limit case spread during an active outbreak. Case surveillance systems can include routine testing for students, either through antigen or PCR tests and particularly after holiday breaks to track potential surges of cases, and the usage of novel Bluetooth systems to measure exposure to other individuals while maintaining necessary levels of privacy. Additionally, long-term investment in improving indoor air quality may help prevent outbreaks of COVID-19 and other highly transmissible seasonal illnesses among students, faculty, and staff. This includes modifying local ventilation using windows and doors and installing high-quality HVAC systems and filters.

Insufficient funding could pose challenges to implementing public health recommendations to mitigate disease transmission in schools. Public schools rely on property and general taxes collected by government and distributed to fund their activities, which, in addition to education, often include social safety net responsibilities such as feeding students, particularly those from lower-income backgrounds, and providing after-school safe childcare. Public schools often receive limited funds to implement such programs [

34,

35]. As a private school, Avenues NYC is not bound to additional obligations beyond education in a way that public schools often are. Avenues NYC collects tuition from most of its students, with a minority of students attending on scholarship disbursements. As such, the school uses the tuition it collects to fund the entirety of its activities and does not have to stretch its funding in the same way that many public schools do, as tuition rates take these additional costs into account when setting the price. Governments, as well as private school administrations, should consider disease transmission mitigation costs when creating future budgets.

This article reflects the state of knowledge and the state of the pandemic in January 2023. Future developments, such as newer or more transmissible variants of SARS-CoV-2 and re-evaluations of indoor air quality improvement, may necessitate further research into mitigation measures to reduce transmission of disease.