3.0. RESULTS

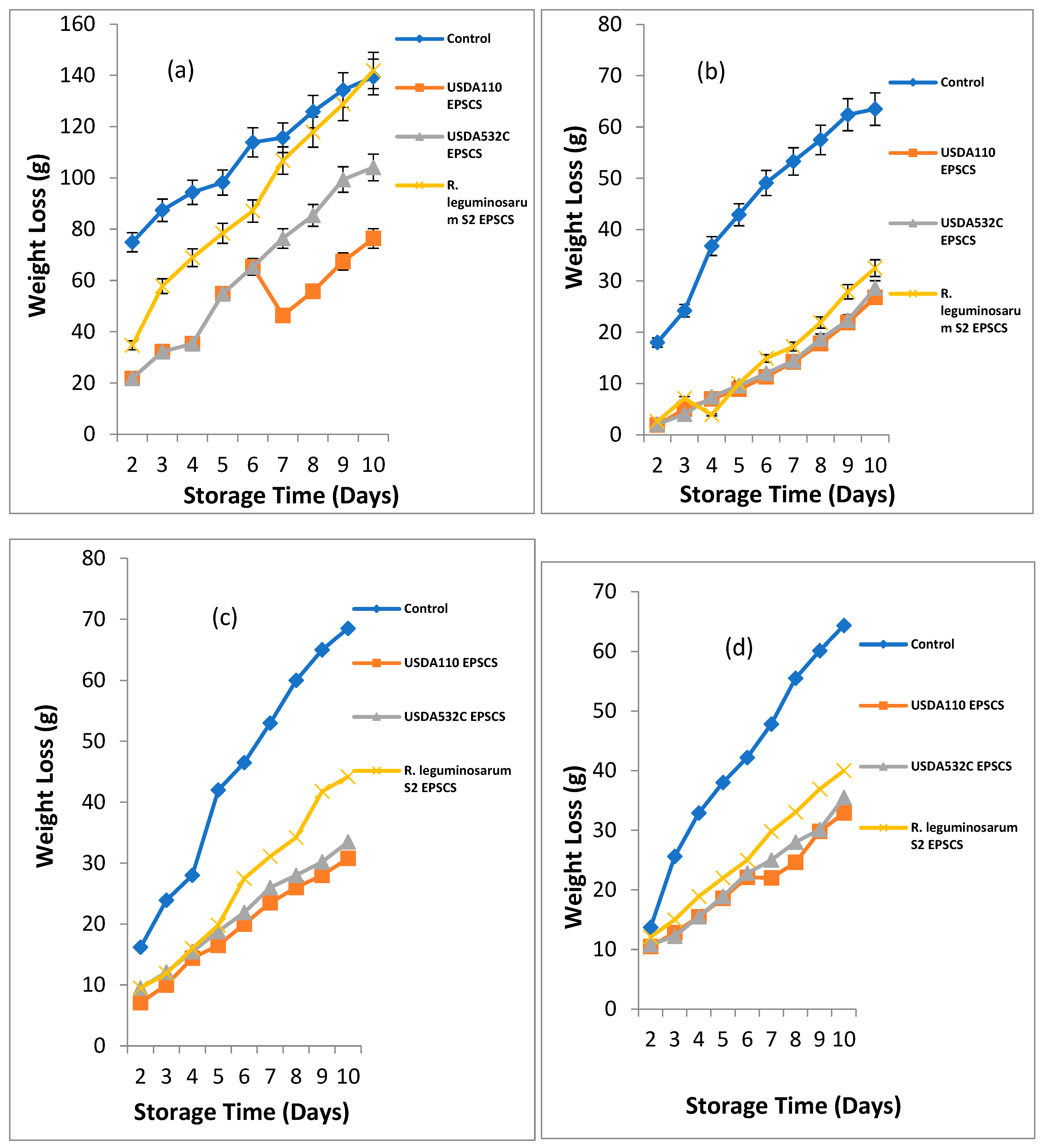

The effect of EPS coating on weight loss of Musa paradisiaca (Plantain)

Musa sp. (Apple Banana),

Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) and

Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) is shown in

Figure 1a - d. The weight loss of

Musa paradisiaca (plantain) coated with EPSA, EPSB and EPSC is shown in

Figure 1a. The initial weight of coated and uncoated

Musa paradisiaca (plantain) at the first day were 314 and 314.5g. At day 2 – 10 of storage the weight loss of EPSACMP, EPSBCMP and EPSCCMP ranged from 21.8 – 76.4g, 21.8 – 104.1g and 34.7 – 141.9g. For uncoated sample the weight loss ranged from 74.9 – 139.4g at day 2 – 10 of storage. There was a major difference (P ≥ 0.05) in the weight loss of coated and uncoated

Musa paradisiaca during storage (

Figure 1a). For

Musa sp. (Apple Banana), the initial weight loss of coated and uncoated

Musa sp. ranged from 72 – 72.7g. For

Musa sp. (Apple Banana), at day 2 -10 of storage, the weight loss of EPSACMS, EPSBCMS, EPSCCMS and UCMS ranged from 18 -63g, 1.9 – 26.8g, 2.1 – 28.6g 2.6 – 32.5 and 18 – 63.5g respectively. Significant difference was noticed in weight loss of coated and uncoated

Musa sp. The maximum loss in weight was recorded in UCMS while the least was recorded in EPSACMS samples as shown in

Figure 1b.

For

Musa acuminata (Lady Finger), the initial weight of

Musa acuminata ranged from 96 – 97g. At day 2 – 10 of storage, the weight loss of EPSACMS, EPSBCMS, EPSCCMS and UCMS ranged from 7.1 – 30.8g, 9.5 – 33.5g, 9.5 – 44.2g and 16.2 - 68.5g respectively. A significant difference (P ≥ 0.05) was noticed in the weight loss of coated and uncoated

Musa sp. The highest weight loss was recorded in UCMS while the least was recorded in EPSACMS samples as shown in

Figure 1c. For

Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana), the initial weight ranged from 95 – 98g. At day 2 – 10 of storage, the weight loss of EPSACMS, EPSBCMS, EPSCCMS and UCMS ranged from 10.5 – 32.9g, 10.8 – 35.5g, 12.1 – 40g and 13.7 – 64.3g shown in

Figure 1d. UCMS had the highest weight loss (32.9 g) while the least weight loss (10.5 g) was observed in EPSACMS sample. However, there was a gradual weight loss in all the samples but the EPS coated samples had the lowest weight loss and as such edible coating was effective in delaying weight loss.

Figure 1.

a-d. Effect of Rhizobia EPS coating on weight loss of (a) Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) (b) Musa sp (Apple Banana) (c) Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) (d) Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage.

Figure 1.

a-d. Effect of Rhizobia EPS coating on weight loss of (a) Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) (b) Musa sp (Apple Banana) (c) Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) (d) Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage.

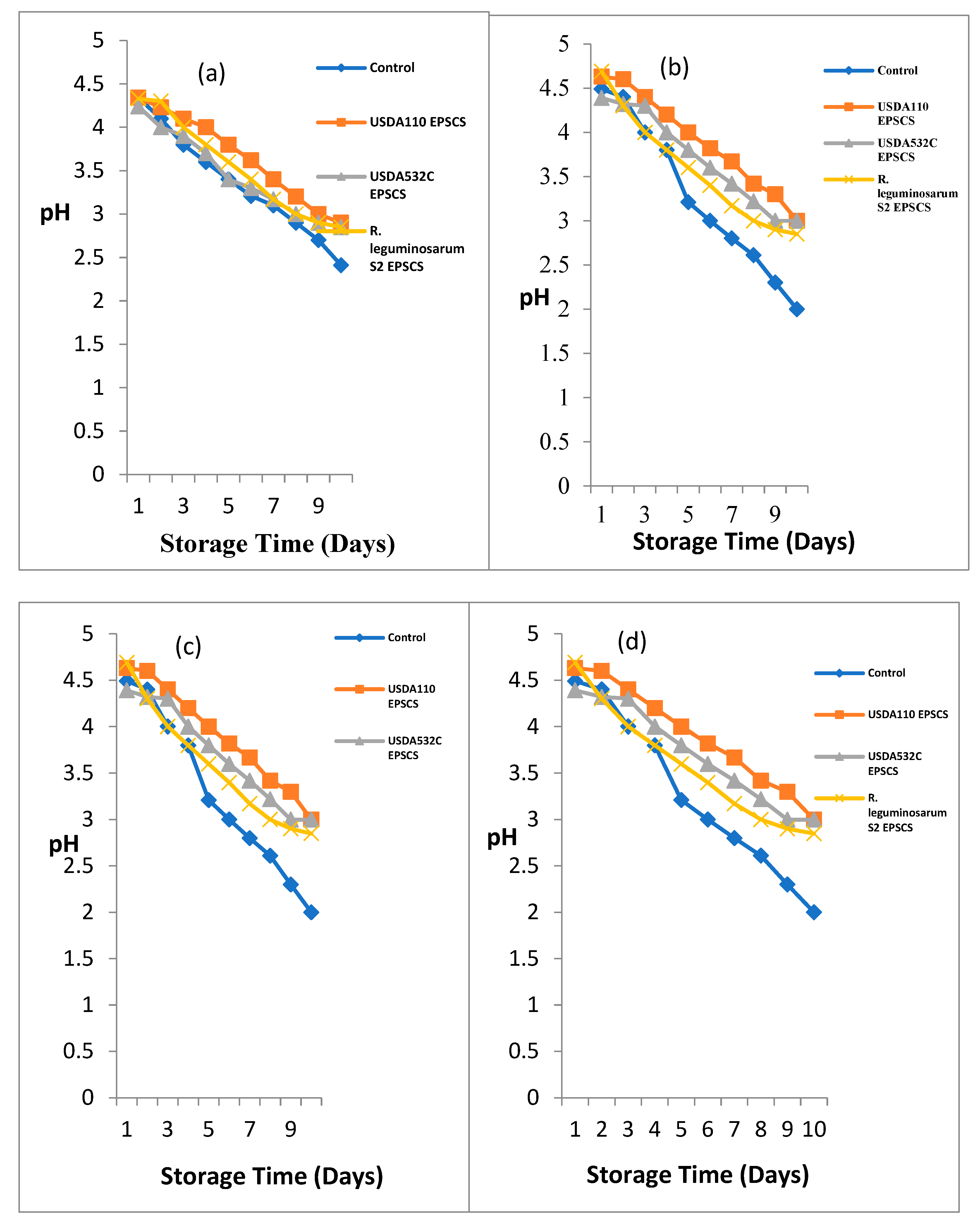

Figure 2a – d shows the outcome of EPS covering on pH of

Musa paradisiaca (Plantain),

Musa sp. (Apple Banana),

Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) and

Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana).

Effect of Rhizobia EPS coating on pH of

Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) during storage is illustrated in

Figure 2a. A major difference (P≤0.05) on the outcome of Rhizobia EPS on the post-harvest value of

Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) during storage was noticed. At day 1, the pH ranged from 4.24 – 4.34 the maximum pH was recorded UNCMP and EPSACMP while the least pH was seen in EPSBCMP. At day 2 of storage, the pH ranged from 4.0 – 4.3. The maximum pH was noticed in EPSCCMP while the smallest pH was obtained from EPSBCMP. At day 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10, the pH ranged from 3.8 – 4.1, 3.6 – 4, 3.4 – 3.8, 3.21 – 3.62, 3.1 – 3.62, 3.1 – 3.4, 2.9 – 3.2, 2.7 – 3 and 2.41 – 2.9 respectively. The highest pH was obtained from EPS coated samples while the least pH was obtained in the UNCMP samples.

For

Musa sp. (Apple Banana), the pH during storage is illustrated in

Figure 2b. A major difference (P≤0.05) on the effect of Rhizobial EPS on the pH of Musa sp. (Apple Banana) during storage. At day 1, the pH ranged from 4.39 – 4.69 the highest pH was recorded in EPSCCMS while the least was recorded in EPSBCMS. At day 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 the pH ranged from 4.2 – 4.6, 4 – 4.4, 3.8 – 4.2, 3.21 – 4, 3 – 3.82, 2.8 – 3.67, 2.61 – 3.42, 2.3 – 3.3and 2 – 3. The highest pH was obtained from EPSACMS while the least was obtained in the UNCMS samples. For

Musa acuminata (Lady Finger), the initial pH of

Musa acuminata ranged from 4.08 – 4.58. At day 2, the pH ranged from 4.0 – 4.3 for coated and uncoated samples. EPSCCMA had the highest pH while the least pH was recorded in UNCM and EPSACMA. The pH ranged from 3.7 – 4.13, 3.5 – 4.02, 3.2 – 4, 3.12 – 3.8, 2.9 – 3.6, 2.6 – 3.4, 2.2 – 3.2 and 2.0 – 3.0 at day 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 of storage. EPSACMA had the highest pH while the UNCMA had the least pH as shown in

Figure 2c.

For

Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana), the pH during storage is shown in

Figure 2d. The pH ranged from 4.24 – 4.54 on the 1st day. The highest pH was recorded in uncoated banana sample while the least pH was recorded in EPSBCMB. At day 2, the pH ranged from 4.0 – 4.35. EPSACMB had the highest pH follow in order by EPSBCMB while the least was recorded in UNCMB sample. The pH ranged from 3.8 – 4.3 at day 3 of storage. The highest pH was recorded EPSACMB while the least was obtained in UNCMB. The pH ranged from 3.6 – 4 at day 4 of storage. The highest pH was obtained in EPSACMB followed in order by EPSBCMB while the least was obtained in UNCMB. At day 5 of storage, pH ranged from 3.4 – 3.8. The highest pH was obtained in EPSACMB and EPSBCMB followed in order by EPSCCMB while the least pH was obtained from the UNCMB. At day 6 of storage, pH ranged from 3.21 – 3.62. The highest pH was obtained in EPSACMB while the least pH was obtained from UNCMB. The pH ranged from 3 – 3.54 and 2.9 – 3.31 at day 7 and 8. The highest pH was obtained in EPSBCMB while the least pH was obtained in UNCMB. At day 9 and10 of storage, pH ranged from 2.7 – 3.1 and 2.4 – 3.0. The highest pH was obtained in EPSACMB while the least pH was obtained from the UNCMB.

Comparatively, the highest pH was observed in EPS coated samples while the least pH was recorded in the uncoated samples.

Figure 2.

a-d. Biopreservative Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on pH of (a) Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) (b) Musa sp (Apple Banana) (c) Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) (d) Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage.

Figure 2.

a-d. Biopreservative Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on pH of (a) Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) (b) Musa sp (Apple Banana) (c) Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) (d) Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage.

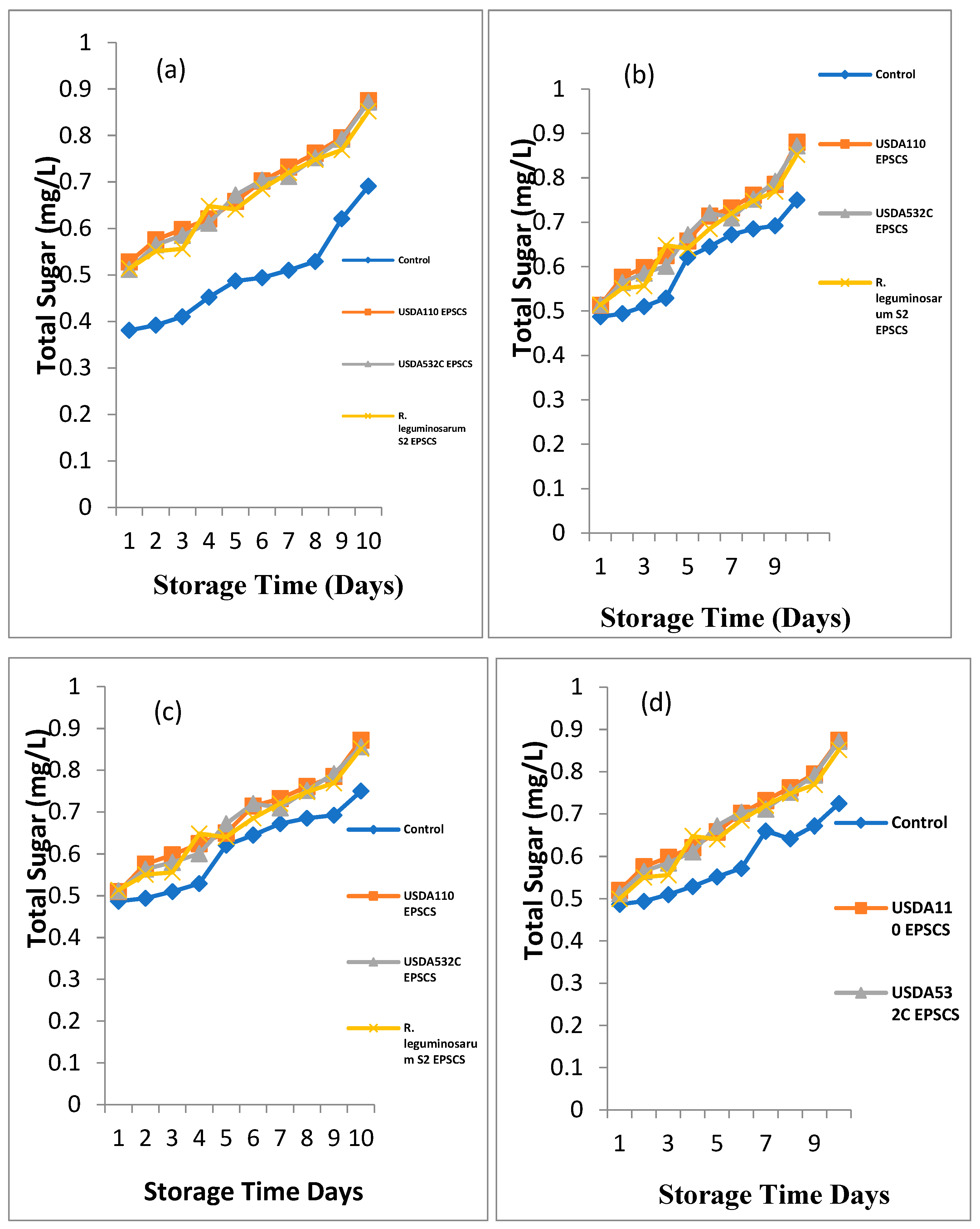

Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on total sugar of

Musa paradisiaca (Plantain),

Musa sp. (Apple Banana),

Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) and

Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage is shown in

Figure 3a - d. For

Musa paradisiaca (Plantain), a major difference (P≤0.05) on the outcome of Rhizobial EPS coating on the total sugar of

M. paradisiaca (Plantain) during storage as shown in

Figure 3a. The total sugar was from 0.381 – 0.528mg/L, 0.392 – 0.576 mg/L and 0.41 – 0.598 mg/L at days 1, 2 and 3 respectively. The highest total sugar was recorded in EPSACMP while the UNCMP had the least total sugar. At day 4 of storage, total sugar was from 0.529 – 0.648 mg/L. The highest total sugar was recorded in EPSCCMP while the UNCMP had the least total sugar. The total sugar ranged from 0.621 – 0.672 mg/L and 0.645 – 0.721 mg/L at day 5 and 6 of storage. EPSBCMP had the highest total sugar while least total sugar was obtained from UNCMP. At day 7 and 8, the total sugar ranged from 0.672 – 0.732 mg/Land 0.685 – 0.761 mg/L. The highest total sugar was recorded in EPSACM while the least was obtained from UNCMP. At day 9 of storage, the total sugar was from 0.692 – 0.792 mg/L. The maximum total sugar was recorded in EPSBCMP while the least was observed in UNCMP. The total sugar ranged from 0.75 – 0.88 mg/Lat the 10th day of storage. The maximum total sugar was recorded in EPSACMP followed in order by EPSBCMP while the least was recorded in UNCMP.

Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on total sugar of

Musa sp. (Apple Banana) during storage at room temperature is illustrated in

Figure 3b. A major difference (P≤0.05) on the outcome of Rhizobial EPS on total sugar of

Musa sp. (Apple Banana) during storage was noticed. The total sugar of EPSCMS was from 0.487– 0.514 mg/L at the 1st day. The maximum total sugar was recorded in EPSACMS and EPSCCMS while the UNCMS had the least total sugar. At day 2 and 3 of storage, total sugar was from 0.494 – 0.576 mg/L and 0.51 – 0.598 mg/L. The highest on total sugar was recorded EPSACMS follow in order by EPSBCMS while the UNCMS had the least. The total sugar of EPSCMS ranged from 0.529 – 0.648 mg/L at day 4 of storage. The highest total sugar was recorded in EPSCCMS followed in order by EPSACMS while the UNCMS had the least total sugar. At day 5 and 6 of storage, the total sugar was from 0.621 – 0.658 mg/L, 0.645 – 0.721mg/L. The highest total sugar was recorded in EPSBCMS while the UNCMS had the least total sugar. At day 7 and 8 of storage, the total sugar ranged from 0.672 – 0.732 mg/L and 0.672 – 0.761mg/L. The highest total sugar was EPSACMS while the UNCMS had the least total sugar. The total sugar ranged from 0.692 – 0.792 mg/L at day 9 of storage. The highest total sugar was recorded in EPSBCMS while the UNCMS had the least total sugar. At day 10 of storage, the total sugar ranged from 0.75 – 0.88 mg/L. The highest total sugar was seen in EPSACMS while UNCMS had the least total sugar.

Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on total sugar of

Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) during storage at room temperature is depicted in

Figure 3c. A major difference (P≤0.05) on the effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on the total sugar of

Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) during storage was noticed. The total sugar ranged from 0.487 – 0.514 mg/L at day 1 of storage. The highest total sugar was recorded in EPSCCMA while the UNCMA had the least total sugar. At day 2 and day 3 of storage, the total sugar was from 0.494 – 576 mg/L and 0.51 – 0.598 mg/L. The maximum total sugar was recorded in EPSACMA while the UNCMA had the least. The total sugar was from 0.529 – 0.648 mg/L at the day 4 of storage. The utmost total sugar was recorded in EPSCCMA while the UNCMA had the least total sugar. At day 5 of storage, the total sugar ranged from 0.621 – 0.672 mg/L. The highest total sugar was obtained from EPSBCMA while the UNCMA had the least. The total sugar was from 0.645 – 0.714 mg/L, 0.672 – 0.732 mg/L and 0.685 – 0.761 mg/Lat the day 6, 7 and 8 of storage. The maximum total sugar was recorded in EPSACMA while the UNCMA had the least total sugar. At day 9 of storage, the total sugar was from 0.692 – 0.792 mg/L. The highest total sugar was recorded in EPSBCMA while UNCMA had the least. At day 10 of storage, the total sugar was from 0.75 – 0.872 mg/L. The highest total sugar was recorded in EPSACMA as UNCMA had the least.

Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on total sugar of

Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage is depicted in

Figure 3d. Significant difference (P≤0.05) on the outcome of Rhizobial EPS coating on the total sugar of

Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage at room temperature was noticed. The total sugar was from 0.487 – 0.512 mg/L at day 1 of storage. The highest total sugar was recorded in EPSACMB while the UNCMB had the least total sugar. At day 2 and day 3 of storage, the total sugar ranged from 0.494 – 576 mg/L and 0.51 – 0.598 mg/L. The highest total sugar was recorded in EPSACMB while the UNCMB had the least. The total sugar ranged from 0.529 – 0.648 mg/L at day 4 of storage. The utmost total sugar was recorded in EPSCCMB while the UNC had the least total sugar. The total sugar ranged from 0.552 – 0.67 mg/L, 0.572 – 0.704 mg/L, 0.66 – 0.718 mg/L, 0.642 – 0.742 mg/L, 0.672 – 0.789 mg/L and 0.725 – 0.879 mg/L at day 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 of storage. The highest total sugar was recorded in EPSBCMB while UNCMB had the least total sugar.

Figure 3.

a-d. Biopreservative Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on Total Sugar of (a) Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) (b) Musa sp (Apple Banana) (c) Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) (d) Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage.

Figure 3.

a-d. Biopreservative Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on Total Sugar of (a) Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) (b) Musa sp (Apple Banana) (c) Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) (d) Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage.

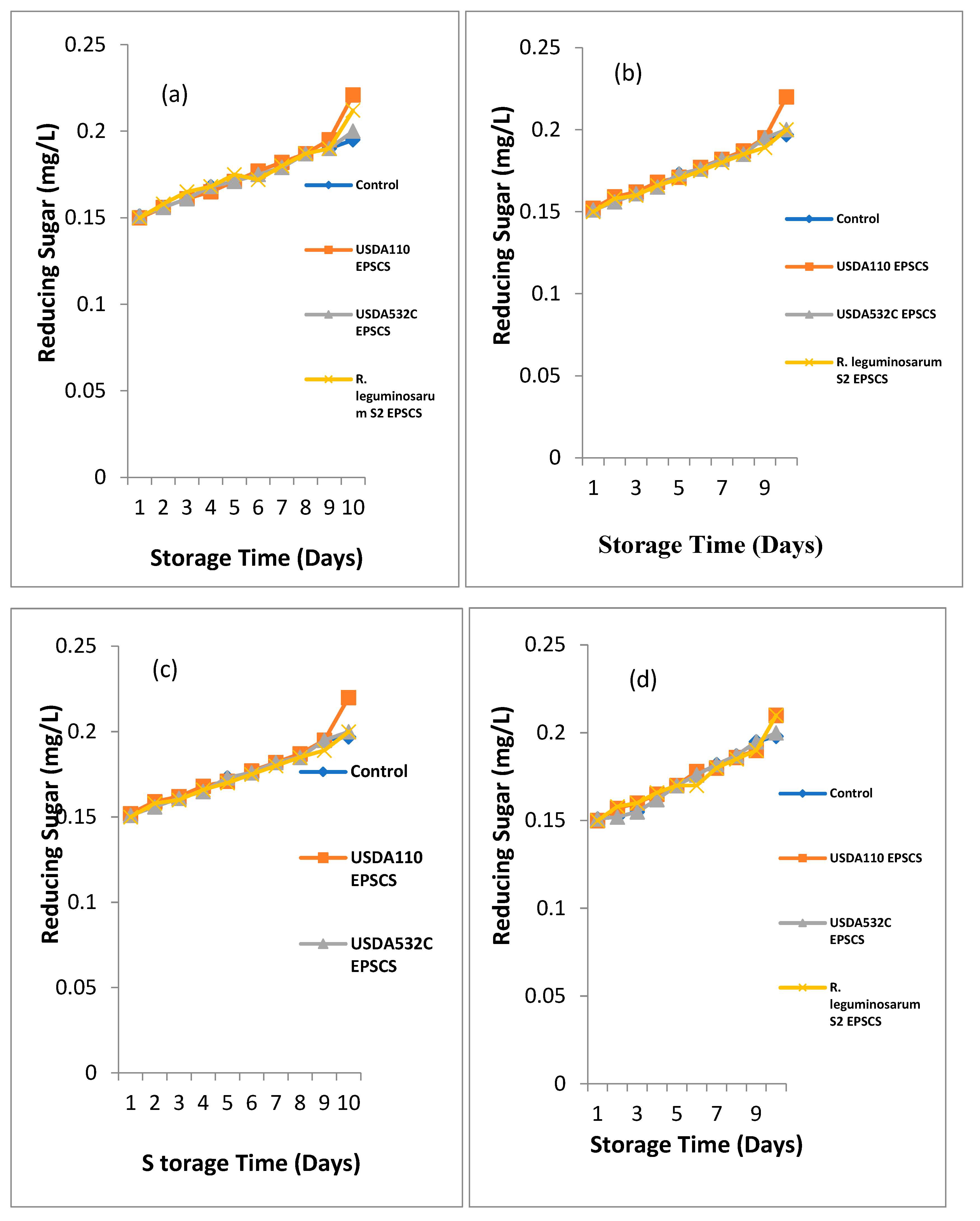

Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on reducing sugar of

Musa paradisiaca (Plantain),

Musa sp. (Apple Banana), Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) and

Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage at room temperature is illustrated in

Figure 4a - d.

Effect of Rhizobia EPS coating on reducing sugar of

Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) during storage at room temperature is shown in

Figure 4a. Major difference (P≤0.05) was seen on the effect of Rhizobia EPS coating on the reducing sugar of

Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) during storage. The reducing sugar was from 0.15 – 0.151 mg/L at the 1st day of storage. EPSBCMP had the highest while EPSACMP, EPSCCMP and UNCMP had the least reducing sugar. At day 2 of storage, the reducing sugar was from 0.156 – 0.159 mg/L and 0.16 – 0.162 mg/L. The highest reducing sugar recorded in EPSACMP while UNCMP had the least. At day 3 of storage, the reducing sugar ranged from 0.16 – 0.162 mg/L. The highest reducing sugar was recorded in EPSACMP while the least reducing sugar was recorded in UNCMP and EPSCCMP. At day 4 of storage, the reducing sugar was from 0.166 – 0.168 mg/L. The highest reducing sugar was observed in EPSACMP which was not significantly different from EPSBCMP and UNCMP while the least reducing sugar was obtained from EPSCCMP. At day 5 of storage, the reducing sugar ranged from 0.17 – 0.171 mg/L. EPSACMP and EPSBCMP had the highest reducing sugar while EPSCCMP and the UNCMP had the least was reducing sugar. At day 6 of storage, the reducing sugar ranged from 0.178 – 0.182 mg/L. EPSACMP had the highest reducing sugar while the UNCMP had the least reducing sugar. The reducing sugar ranged from 0.178 – 0.182 mg/L and 0.19 – 0.187 mg/L at 7 and 8 days of storage. EPSACMP and EPSBCMP had the highest reducing sugar while UNCMP had the least reducing sugar. The reducing sugar ranged from 0.19 – 0.2 mg/L at the day 9 of storage. EPSBCMP and EPSCCMP had the highest reducing sugar while UNCMP was observed with the least reducing sugar. At day 10 of storage, the reducing sugar ranged from 0.195 – 0.22 mg/L. EPSACMP and EPSCCMP had the highest reducing sugar while UNCMP had the least reducing sugar.

Effect of Rhizobial EPS covering on reducing sugar of

Musasp (Apple Banana) during storage is depicted in

Figure 4b. A major difference (P≤0.05) was seen on the effect of Rhizobial EPS covering on the reducing sugar of

Musasp (Apple Banana) during storage at 28

oC. At day 1 of storage, the reducing sugar ranged from 0.15 – 0.151 mg/L. UNCMS and EPSBCMS had the highest while EPSACMS and EPSCCMS had the least reducing sugar. At day 2 and 3 of storage, the reducing sugar ranged from 0.156 – 0.158 mg/L and 0.161 – 0.165 mg/L. The maximum reducing sugar was recorded in EPSCCM while UNCMS, EPSACMS and EPSCCMS had the least. At day 4 of storage, the reducing sugar ranged from 0.165 – 0.168 mg/L. The highest reducing sugar was observed in the UNCMS, EPSBCMS and EPSCCMS while the least was obtained from samples coated with EPSACMS. At day 5 of storage, the reducing sugar ranged from 0.171 – 0.75 mg/L. The maximum reducing sugar was recorded in EPSCCMS while the least reducing sugar was recorded in UNCMS which was not significantly different (P ≥ 0.05) from EPSACMS and EPSBCMS. At day 6 of storage, the reducing sugar ranged from 0.173 – 0.77 mg/L. The highest reducing sugar was recorded in EPSCCMS while the least reducing sugar was recorded in UNCMS. At day 7, 8, 9 and 10 of storage, the reducing sugar ranged from 0.1735– 0.182 mg/L, 0.179 – 0.18 mg/L, 0.182 – 0.19 mg/Land 0.189 – 0.212 mg/L. The highest reducing sugar was recorded in EPSCCMS while the least reducing sugar was recorded in UNCMS.

Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on reducing sugar of Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) during storage is depicted in Figure 4.21c. A major difference (P≤0.05) was noticed on the outcome of Rhizobial EPS coating on the reducing sugar of Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) during storage at room temperature. At day 1 of storage, the reducing sugar ranged from 0.15 – 0.152 mg/L. The highest reducing sugar was recorded in EPSACMA while the UNCMA, EPSBCMA and EPSCCMA had the least. At day 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7of storage, the reducing sugar ranged from 0.156– 0.159 mg/L, 0.161 – 0.164 mg/L, 0.163 – 0.168 mg/L, 0.168 – 0.172 and 0.17 – 0.177, 0.175 – 0.183. The highest reducing sugar was recorded in EPSCCMA while the least reducing sugar was recorded in UNCMA. The reducing sugar ranged from 0.18 – 0.185 mg/L at day 8 of storage. The highest reducing sugar was recorded in EPSACMA which was not significantly higher than EPSBCMA and EPSCCMA while the least reducing sugar was recorded in the UNCMA. At day 9 and 10 of storage, the reducing sugar was from 0.187 – 0.193 mg/L and 0.189 – 0.21 mg/L. The highest reducing sugar was recorded in EPSCCMA while the least reducing sugar was recorded in UNCMA.

Effect of Rhizobial EPS covering on reducing sugar of

Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage is depicted in

Figure 4d. A major difference (P≤0.05) was noticed on the effect of Rhizobia EPS covering on the reducing sugar of

Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage at room temperature. The reducing sugar ranged from 0.15 – 0.151 mg/L at the 1st day of storage. EPSBCMB had the highest while EPSACMB had the least reducing sugar. At day 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 of storage, the reducing sugar ranged from 0.152 – 0.158 mg/L, 0.155 – 0.162 mg/L, 0.162 – 0.166 mg/L, 0.17 – 0.173 mg/L, 0.174 – 0.178 mg/L, 0.178 – 0.184 mg/L, 0.18 – 0.187 mg/L, 0.183 – 0.196 mg/L and 0.186 – 0.21 mg/L. EPSCCMB had the highest reducing sugar while the least was recorded in UNCMB.

Figure 4.

a-d. Biopreservative Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on Reducing Sugar of (a) Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) (b) Musa sp (Apple Banana) (c) Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) (d) Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage.

Figure 4.

a-d. Biopreservative Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on Reducing Sugar of (a) Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) (b) Musa sp (Apple Banana) (c) Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) (d) Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage.

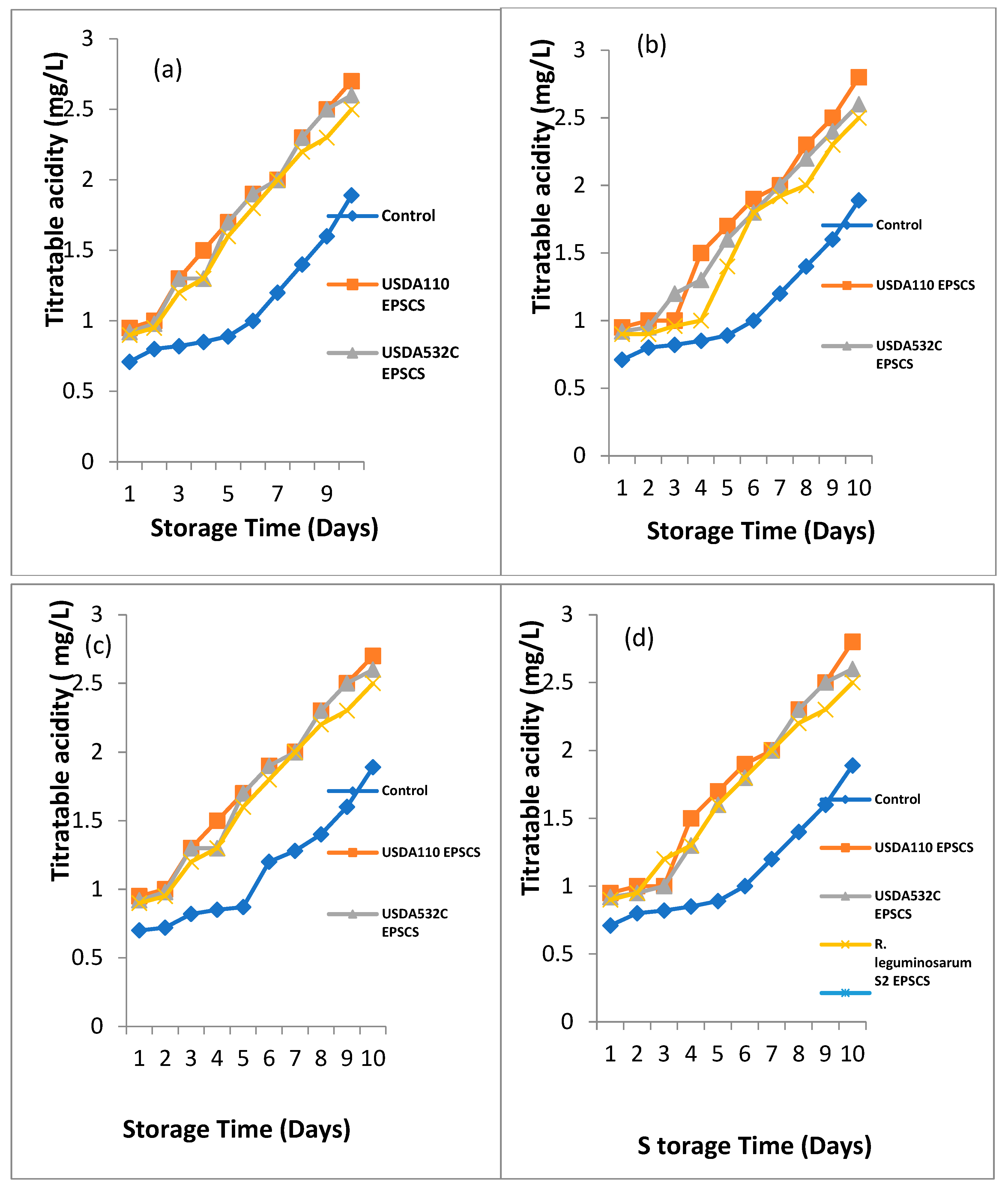

Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on titratable acidity of

Musa paradisiaca (Plantain),

Musa sp. (Apple Banana),

Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) and

Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage at room temperature is shown in

Figure 5a - d.

Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on titratable acidity of

Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) during storage is illustrated in

Figure 5a. A major difference (P≤0.05) on outcome of Rhizobial EPS covering on the titratable acidity of

Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) during storage. At day 1and 2 of storage, the titratable acidity ranged from 0.71 – 0.95 mg/L and 0.8 – 1 mg/L. The highest titratable acidity was observed in EPSACMP follow in order by EPSBCMP while UNCCMP had the least titratable acidity. At day 3 of storage, the titratable acidity ranged from 0.82 – 1.3 mg/L. EPSACMP and EPSBCMP had the highest titratable acidity while UNCMP had the least.

Titratable acidity ranged from 0.82 – 1.3 mg/L at day 4 of storage. The highest Titratable acidity was recorded in EPSACMP followed in order by EPSBCMP and EPSCCMP while UNCMP had the least titratable acidity. Titratable acidity ranged from 0.89 – 1.7 mg/L, 1 -1.9 mg/L, 1.2 – 2 mg/L, 1.4 – 2.3 mg/L and 1.6 – 2.5 mg/L at day 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 of storage. The highest titratable acidity was recorded in EPSACMP and EPSBCMP followed in order by EPSCCMP while the UNCMP had the least titratable acidity. At day 10 of storage, titratable acidity ranged from1.89 – 2.7 mg/L. The highest Titratable acidity was observed in EPSACMP followed in order by EPSBCMP while UNCMP had the least titratable acidity.

Effect of Rhizobial EPS covering on titratable acidity of

Musasp (Apple Banana) during storage is depicted in

Figure 5b. A major difference (P≤0.05) was noticed on the effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on the Titratable acidity during storage. At day 1, 2 and 3 of storage, the titratable acidity ranged from 0.71 – 0.92 mg/L and 0.79 – 1 mg/L and 0.81 – 1 mg/L. The highest Titratable acidity was observed in EPSACMS followed in order by EPSBCMS while the least Titratable acidity was recorded in the UNCMS. At day 4 and 5 of storage, the titratable acidity ranged from0.85 -1.5 mg/L and 0.89 – 1.5 mg/L. EPSACMS had the highest titratable acidity while the least was obtained from the UNCMS samples. At day 6 and 7 of storage, the titratable acidity ranged from 1 -1.9 mg/L and 1.2 – 2 mg/L. EPSACMS had the highest titratable acidity followed in order by EPSBCMS while the least was obtained from UNCMS. The titratable acidity ranged from 1.4 – 2.3 mg/L, 1.6 – 2.5 mg/L and 1.89 – 2.8 mg/L at day 8, 9 and 10. EPSACMS and EPSBCMS had the highest Titratable acidity while the UNCMS sample had the least.

Effect of Rhizobial EPS covering on titratable acidity of

Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage is depicted in

Figure 5d. A major difference (P≤0.05) was seen on the effect of Rhizobia EPS covering on the Titratable acidity of

Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage. At day 1, 2 and 3 of storage, the titratable acidity ranged from 0.71 – 0.95 mg/L, 0.8 – 1 mg/L and 0.82 – 1 mg/L. The highest Titratable acidity was observed in EPSACMB while the least Titratable acidity was recorded in UNCMB. At day 4, 5 and 6 of storage, the titratable acidity ranged from 0.85 -1.5 mg/L and 0.89 – 1.6 mg/L. The highest Titratable acidity was observed in EPSACMB follow in order by EPSCCMB while the least Titratable acidity was recorded in UNCMB. The Titratable acidity ranged from 1.2 – 2 mg/L at day 7 of storage. The highest Titratable acidity was observed in EPSACMB, EPSBCMB and EPSCCMB. At day 8 and 9 of storage, the titratable acidity ranged from 1.4 – 2.3 mg/L, 1.6 – 2.5 mg/L. The highest Titratable acidity was observed in EPSACMB and EPSBCMB while UNCMB sample had the least. At day 10 of storage, the titratable acidity ranged from 1.89 – 2.8 mg/L. The highest Titratable acidity was observed in EPSACMB follow in order by EPSBCMB while the least Titratable acidity was recorded in UNCMB.

Figure 5.

a-d. Biopreservative Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on Titratable acidity of (a) Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) (b) Musa sp (Apple Banana) (c) Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) (d) Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage.

Figure 5.

a-d. Biopreservative Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on Titratable acidity of (a) Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) (b) Musa sp (Apple Banana) (c) Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) (d) Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage.

4.0. DISCUSSION

Characterisation of EPS using FT-IR: FT-IR spectroscope is a valuable procedure that works on the standard that group of bonds vibrates at characteristic frequencies. It can be employed to identify functional groups and characterizing covalent bonding. Characterisation of EPS from Rhizobia using FT-IR showed the existence of functional groups such as hydroxyl, alkane, alkene, alkyl and amine group as well as stretches of C=O of alcohol group in the EPS. The presence of this band shows that the substance is a polysaccharide [

13]. Lack of peaks in the range of 260- 290cm-

1obviously shows the lack of any protein and nucleic acids. The EPS contain large number of H-O stretching frequency with a broad absorption peak of 3539, 3395, 3538.66, 3537.11, 3537.09, 3389.58, 3416.92 and 3633.33cm

-1. The bands of some stretching vibration of carboxyl group (C=O) were seen and were due to associated water which indicates the presence of some organic substances such as the stretching of sugar (mannose or galactose) [

14]. The relatively weak absorption peaks at 888.59, 883.82, 838.22, 839.61, 872.44, 887.08, 888.59 and 892.49 cm

-1 might be ascribed to C=C (alkene). Furthermore, the bands within 776.22 – 601.91 cm

-1 regions were assigned to the vibration of the C-H and C-I halo bands.

Characterisation of EPS using TGA: Thermal stability is a vital feature to consider for industrial use of EPS, particularly in food industry, because most food manufacturing and processing takes place at elevated temperatures [

15]. According to Sri

et al. [

16] when EPS is subjected to diverse temperatures, the major measures that take place with the initial boost in temperature are gelatinization and swelling. Additional increase in temperature causes drying out and pyrolysis of the exopolysaccharide. The TGA of the EPS shows two stages of weight loss which occurred around 286.46 and 487.94, 262.32 and 498.9, 227 and 547.4, 244.45 and 394.24 and 268.68 and 494.75

oC. The large weight loss may be attributed to the breakdown of carbon. This primary weight loss may be related with the loss of moisture. Many reports recommended that initial loss of moisture is due to the carboxyl groups which are present in high level and are bound to water molecules [

17]. Thus, the initial weight loss by EPS produced by the Rhizobial strains is due to the existence of elevated content of carboxyl groups. The difference between the degradation temperature values of various EPSs is ascribed to their varied structural composition.

Characterisation of EPS using GC-MS: GC-MS has been used to categorize the constituent volatile matter, long chain, branched chain hydrocarbons, alcohols, acids and esters [

18]. The GC-MS chromatogram of all the EPS tested revealed the presence of some active compounds (pentadecanoic acid, octadecanoic acid, oleic acid and heptacosanoic acid).

Determination of monosaccharides constituent of Rhizobial EPS via HPLC: D-ribose had the highest concentration in the EPS produced from USDA 110 (EPSA) while rhamnose was observed to be the highest in USDA 532C (EPSB) and

Rhizobium leguminosarumS2 EPS (EPSC) Mannose and arabinose had the least sugar concentration in USDA 110 and USDA 532C respectively. The sugar concentration varied when all the Rhizobial EPS were compared. Sugars such as rhamnose, arabinose, mannose, glucose and galactose were present in all the EPS samples with different concentration. D-ribose, xylose and Inositol was present in USDA 110 EPS. This work is in disparity with the results of Castellane

et al. [

10] who found that EPS obtained from

Mesorhizobium huakuii,

M. loti,

M. plurifarium,

Rhizobium giardinibv.

Giardini, R. mongolense and

Sinorhizobium (Ensifer) kostiense were primarily composed of glucose and galactose. Castellane

et al [

10] accounted that the EPSs from

R. tropicis showed a related composition to rhizobia isolates, with glucose being the main sugar component accompanied by galactose and then glucuronic acid, rhamnose, and mannose, which were found in trace amounts. Numerous studies have reported that the EPS monosaccharide constituent may depend on the carbon source used for growth [

19,

20]. The complexities in their monosaccharide and non-carbohydrate compounds are responsible for their biotechnology properties which enable their potential use as gelling agents, emulsifiers [

21,

22], stabilizers, texture-enhancing agents and flocculation agents.

Effect of Rhizobial EPS coating on weight loss, pH, total sugar, reducing sugar and titratable acidity of

Musa paradisiaca (Plantain),

Musa sp (Apple Banana),

Musa acuminata (Lady Finger) and

Musa balbisiana (Cooking Banana) during storage was studied. Post-harvest spoilage is a main cost in food production and when polysaccharides based edible coverings are applied on fresh and minimally processed fruits and vegetables, by formation of a modified atmosphere condition help to trim down their respiratory rate. It’s enhanced mechanical handling property and additives carrying capacity [

23]. In all the fruits preserved, the maximum weight loss was noticed in uncoated fruits (control) while the least weight loss was obtained in EPS coated fruits. The lowest pH was noticed in uncoated fruits while the highest pH was observed in covered fruit samples. The maximum titratable acidity was noticed in EPS coated fruits samples while the least titratable acidity was obtained in the non EPS coated fruit samples. The total sugar content steadily increased at day 10 of storage for both the covered and the uncovered fruit samples. The total sugar was noticed in EPS covered fruits samples while the least total sugar was obtained in the uncovered fruit samples. The outcome of EPS coating steadily increase the reducing sugar content among the fruits of the coated and the uncoated fruit samples. The rise in the reducing sugar with the advancement of ripening as well as storage time was due to derogation of starches. The utmost reducing sugar was observed in EPS coated fruits samples while the lowest reducing sugar was obtained in the uncoated fruit samples. In general, EPS coated fruits samples were observed to have longer shelf life than the uncoated samples.