Introduction

Pattanam (10° 09.434' N Latitude and 76° 12.587' E Longitude) an ancient port city located on the southwestern coast of the Indian subcontinent in the Ernakulam District of Kerala, India. The town is a multi-cultural port site present at the delta of the Periyar River north of Ernakulam /Kochi and adjacent to the Arabian Sea [

1]. Early maritime exchange existed in ancient states of India as circuitous routes or mid-ocean routes or both. These routes functioned as "mobile bazaars" for the supply of essential items. The most important ports of ancient times on the southwest coast included Tindis, Muziris, Nelcynda and Becare [

2]. Multiple ethnoreligious communities migrated and settled due to the presence of these coastal belts [

3,

4,

5].

The chronology of the Pattanam site (

Figure 1A) depicts a settlement history of three millennia. The chronology spans through the initial settlement beginning with the Iron Age habitation with a commercial peak between the 1st century BCE and the 3

rd century CE. Dating results from Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) Carbon14 (C14) on the charcoal samples confirm the Iron Age native settlement in Pattanam around 1000 BCE [

6]. Other archaeological evidence shows the presence of maritime features such as port features like the wharf and urban planned architectural features. Twelve seasons of excavations at the Pattanam site have revealed a wide category of findings; some in staggering proportions. Major finds include ceramic numbering over 4.5 million, lapidary objects ranging from ballasts to precious stone jewellery, objects made of iron, copper, lead and gold- including coins and jewellery, and faunal and botanical remains [

7]. The high density of archaeological remains at the Pattanam excavation site depicts a 2000-year-old polychromatic and polyphonic urban culture with maritime connectivity to three continents - Asia, Africa, and Europe. Fine pottery from Indian and foreign origins such as Mediterranean (Roman) pottery, Turquoise Glazed Pottery, Amphora, and Indian Rouletted Ware (

Figure 1B–D) [

7,

8]. Indian fine pottery signifies the crucial role of the Indian Ocean trade network in earlier times. Pattanam excavation site unearthed the largest ever assemblage of Indian rouletted wares, the first-ever reporting of roulette ware from the southwestern coast of India. The shreds excavated from Pattanam archaeological sites are from as early as 1000 BCE to 500 CE.

Excavation of the Pattanam archaeological site has been carried out by the Kerala Council for Historical Research (KCHR), Thiruvananthapuram from 2007 to 2015 and since 2018 by the PAMA Institute for the Advancement of Transdisciplinary Archaeological Sciences. The excavation revealed the presence of an early historic (300BCE – 500CE), multi-cultural port site, which is now widely considered an integral part of the ancient port of Muziris. Thirteen skeletal samples were obtained from various seasons of Pattanam excavations. Seven bone samples were collected in 2007, one fragment in 2009, one fragment in 2010, one tooth sample in 2011 and finally, two bone fragments with one tooth sample in 2013. The skeletal remains were excavated in a highly fragile state due to the tropical, moist, and acidic soil conditions of the Pattanam site. The early historic period of the site dates to the 3rd c BCE to 4th c CE based on chronometric, morphometric and stratigraphic analyses [

9]. The AMS radiocarbon dating points towards the 1st century BCE- 1st century CE period. The paleoanthropological studies conducted on the bone by biological anthropologists pointed out the presence of flash over the bones, which further indicate the practice of secondary burial where the dead is cremated first, and the osseous remains are buried again later ceremonially.

The samples were later administered for computational analyses. The study aimed to establish the ancestry of the samples based on the affiliated haplogroup of the samples in the context of South Asian ancestry. This is one of the first genetic studies conducted on the samples excavated from the Pattanam archaeological site. The study is based on genotyping of the mitochondrial DNA using a mass array Sequenome platform and the analysis is based on haplogroup determination.

Materials and methods

Methodology

DNA extraction from skeletal remains

Very stringent standards were applied for the authentication of ancient DNA. An attempt was made to extract DNA from all thirteen samples; however, the DNA could be extracted successfully from 12 samples only. All the samples were treated independently in a dedicated ancient DNA laboratory at the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Hyderabad, India. Three independent DNA extractions were performed per sample for the authenticity of the entire procedure. Extreme care was taken to avoid any form of contamination the DNA was extracted with relative extraction controls.

Approximately 500mg of each bone sample was initially polished with sandpaper and then powdered with drills. The bone powder was dissolved in 4.0 ml extraction buffer (0.5 M EDTA pH 8.0, 0.5% SDS, and 500 µg/ml proteinase K) and incubated in a shaking incubator at 55°C overnight, followed by incubation at 37°C for 12 hours. Further, QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) was used to trap the DNA fragments that are larger than 100 bp and smaller than 10 kb and exclude nucleotides, proteins, and salts. The columns are ideally suited for ancient DNA since the templates in the case of ancient DNA are highly degraded and the target regions are generally quite small (100 to 250 bp). The extraction solution was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 minutes and 4.0 ml aliquots of the supernatant were transferred to a 50 ml tube and mixed with 5 volumes of QIAquick PB buffer. From this, 750 µl was loaded directly onto QIAquick columns and centrifuged at 12,800 g for 1 minute. The flow-through was discarded and the process was repeated until all the extracts had been passed through the column. The DNA was washed with 750 µl of QIAquick PE buffer and centrifuged for 1 minute. The flow-through was discarded and the DNA was then eluted from the column by loading 40µl of elution buffer followed by centrifugation for 1 minute.

Quality Control for ancient DNA extraction and amplification

The ancient human bones used in this study were highly fragile and old, and efforts were made to treat them with extreme care. One of the major concerns was to avoid any contamination by exogenous DNA. All steps (Bone cleaning, cutting of bone samples, drilling, DNA extraction and PCR preparation) were carried out in two separate laminar air flows. Laboratory instruments and devices used for DNA extraction were cleaned using commercial bleach and 70% alcohol followed by UV irradiation for at least 45 minutes. DNA extraction and PCR set-up were carried out in two different dedicated chambers. Disposable full-body suits and gloves were used during the entire processing of samples. Aerosol barrier tips and ultrapure DEPC-treated water were used for all the experiments carried out in the ancient DNA lab.

Haplogroup determination

After the successful amplification of the mitochondrial DNA, the observed genotype results of Pattanam excavated samples were compared with the Cambridge reference sequences. Further, the genotype results of the Pattanam samples were compared with the worldwide data and established the ancestry of the samples based on the affiliated haplogroup of the samples (

Table 1).

Radioactive AMS dating of ancient samples

AMS radiocarbon dating of Pattanam samples were done at BETA ANALYTIC INC., Miami, Florida, USA. Raw material used for this purpose was the cremated bone carbonate and pre-treatment was bone carbonate extraction. Calibration was done with 2013 database (INTLCAL13) from conventional radiocarbon dates and results reported are 2 sigma calibrated (

Supplementary Table S1).

Results

We have successfully generated good-quality genotype data of a total of 12 Pattanam ancient bone remains. After a careful comparison of mutations observed in Pattanam samples and Phylotree, we determined the mitochondrial haplogroups of all 12 samples. We found both South Asian and West Eurasian-specific mtDNA haplogroups among all Pattanam samples. Haplogroups of Samples PT3, PT6 and PT8 were M2a1a3, M6 and M3a1 respectively, which are South Asian mitochondrial haplogroups. In addition to this haplogroups of samples PT10 and PT13 are South Asian specific U1 and R5 respectively (Table:1).

Many samples were belonging to west Eurasian mitochondrial haplogroups whose prevalence in South Asian populations is very less. Among these West Eurasian haplogroups, HV and subgroup HV4b were observed in samples PT1 and PT4 respectively. Haplogroup T and its subclade T1a9 were found in samples PT9 and PT2 respectively. While JT was present in sample PT3. The haplogroup of sample PT11 was uncharacterised because of the lack of resolution of genotyped mutation in this sample (Table:1).

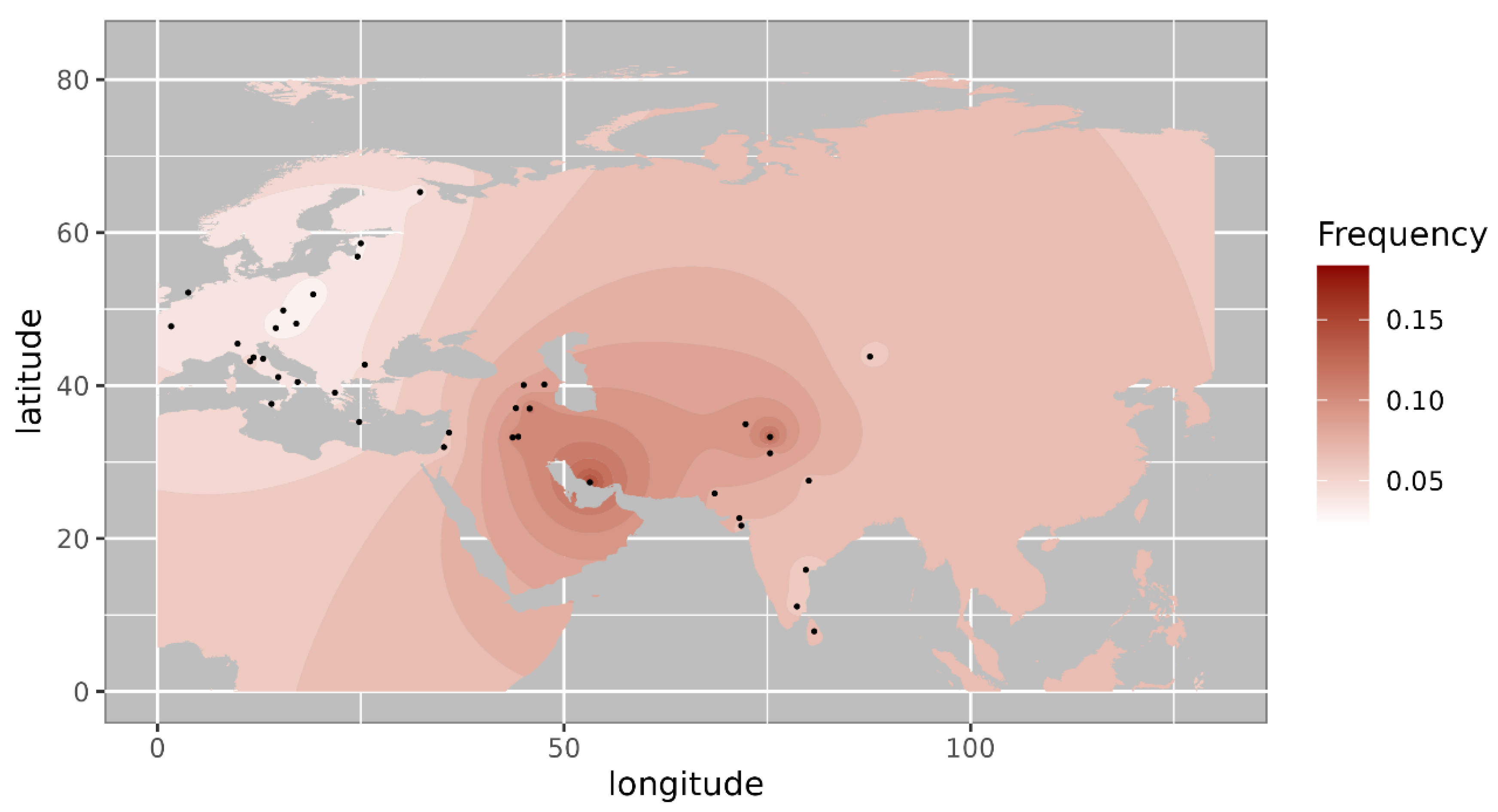

Further we made a comparison of the haplogroup prevalence of ancient Pattanam samples with the available frequency in worldwide populations. We are showing the frequency distribution of some of the major West Eurasian haplogroups viz, HV, T1a and JT on the map. Frequency of haplogroup HV is with its highest prevalence in the Caucasus and Middle East and southern Europe (

Figure 2) [

10]. Its frequency is highest in Iraq (0.12) in the Middle East, followed by Armenia (0.07) and Azerbaijan (0.06) in the Caucasus [

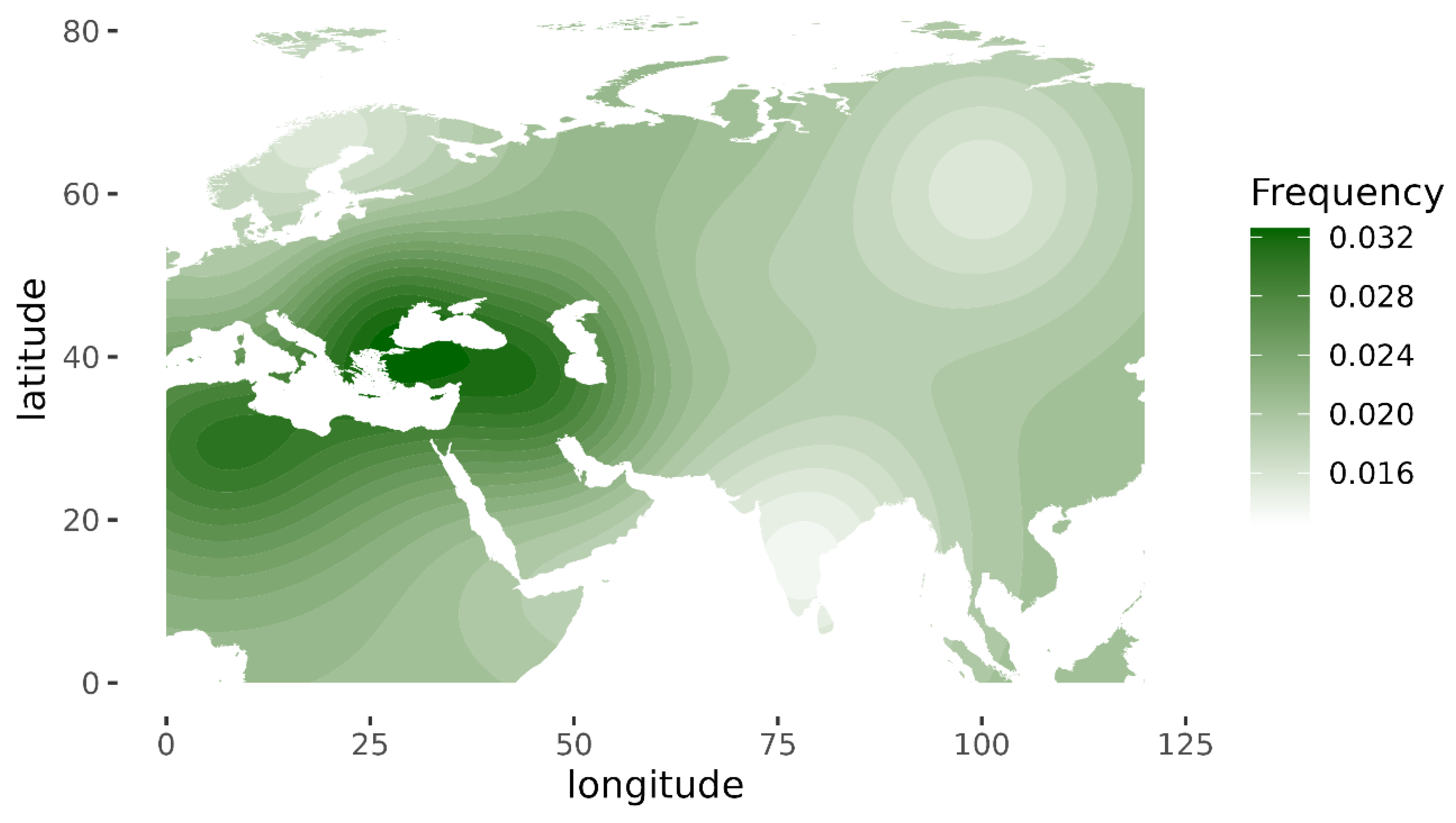

10]. Haplogroup T1a has the highest frequency in Balkan countries, Caucasus, and the Middle East and with lesser frequency in most of Europe (

Figure 4) [

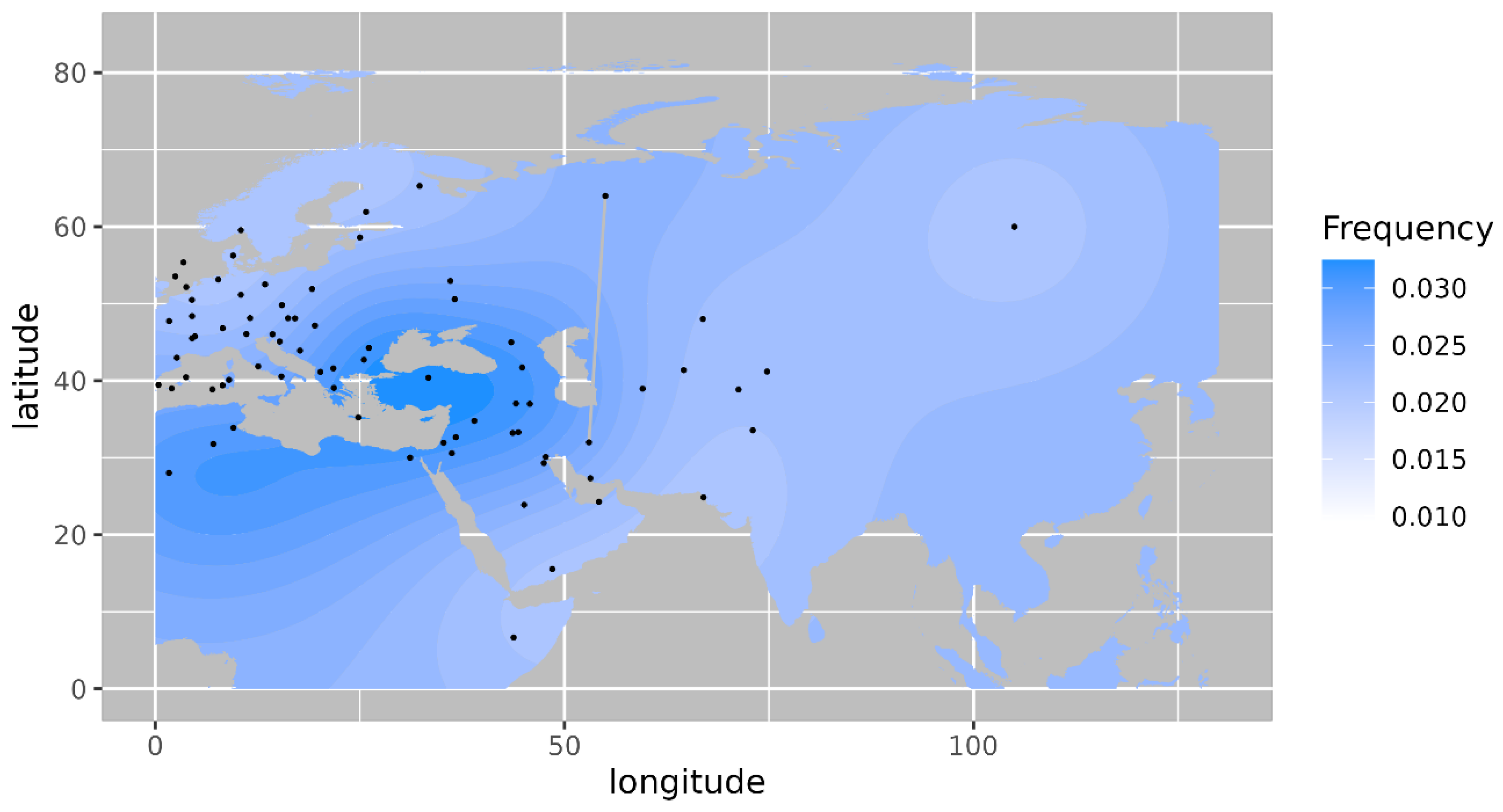

11]. Its highest frequency is in Romania (0.08), Tunisia (0.07) and Iran (0.06). Haplogroup JT has the highest occurrence in Near East (0.45), the Alps (0.33) and Georgia (0.25) and is also prevalent in most of Europe (

Figure 3) [

10].

Among South Asian haplogroups found in Pattanam samples, M2a1 is present in most of the Indo-European and Dravidian tribes with coalescent ages of 7 – 9 KYA [

12]. Haplogroup M3a1 is also mainly Indian-specific. It was found majorly among Indo-European and Dravidian tribes of North, Central and South India [

13]. It was also observed in the Kashmir region of North India [

14]. Haplogroups M6 and R5 have widespread occurrences in India [

13].

Discussion

South Asia is one of the most diverse regions of the world and the centre of attraction for merchants and commercial trades. Ports played an important role in ancient times for trade such as for spices, textiles, and raw materials. Multiple groups migrated to Indian coastal regions for trade and settlement. Several genomic studies published earlier support the migration of many groups in and from India. Footprints of all these earlier migrations are present in the form of excavated ancient remains of the people of those ancient times and deciphering their genetic history using the blooming ancient DNA field is an exciting field of interest. Harsh geographical and climatic conditions make the recovery of ancient DNA a challenging task in India but not an impossible one [

5,

15,

16].

Pattanam is an important town since ancient times due to trade and cultural exchange. Archaeological remains support the cultural exchange on the southwestern coast of India such as fine pottery and urban architectural constructions [

1]. Many migratory communities such as Romans, Portuguese, Jews, Islamic and Christians migrated to coastal parts of India in multiple waves. An in-depth analysis of skeletal remains excavated from the Pattanam archaeological site supports the claim and in the current study, the first attempt at genotyping of mtDNA markers helped understand the demographic distribution of the Pattanam location [

6,

9]. The results show a mixture of ethnicity from West Eurasian ancestry to South Asian ancestry. The frequency distribution of haplogroups reflects a high Occurrence of West Eurasian (T, JT and HV) and South Asian-specific mitochondrial haplogroups (M2a, M3a, R5 and M6). The presence of haplogroups HV, T1a9, JT, HV4b, T, U1, and U5 strongly supports the presence of West Eurasian and European ancestry, whereas M2a1a3, M6, M3a1 and R5 haplogroups support the South Asian ancestry. The presence of such a diverse set of haplogroups reflects the mixture of multiple cultural and religious groups who must have migrated, settled, and eventually died on the Southwestern coast of India.

Conclusively, it can be stated that our findings are consistent with the archaeological findings that support the presence of multicultural groups in the town of Pattanam. Our current study is the first attempt to genetically structure the demographic classification of the Pattanam archaeological site and to infer their mitochondrial phylogeny.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Lomous Kumar; Validation, P J Cherian; Formal analysis, Bhavna Ahlawat and Lomous Kumar; Resources, P J Cherian; Data curation, Lomous Kumar; Writing – original draft, Bhavna Ahlawat and Lomous Kumar; Writing – review & editing, Jagmahender S Sehrawat and P J Cherian; Visualization, Niraj Rai and Kumarasamy Thangaraj; Supervision, Niraj Rai and Kumarasamy Thangaraj; Project administration, Niraj Rai and Kumarasamy Thangaraj; Funding acquisition, Niraj Rai and Kumarasamy Thangaraj.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by NAME OF FUNDER, grant number XXX” and “The APC was funded by XXX”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new sequence data was generated. Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

NR thank the Director, Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences for scientific support and Department of Science and Technology for CRG grant (CRG/2021/006762) from SERB. K.T was supported by the JC Bose Fellowship (JCB/2019/000027), SERB, DST and CSIR, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Cherian, P.J. Pattanam archaeological site: The wharf context and the maritime exchanges. in Asia-Pacific Regional Conference on Underwater Cultural Heritage Proceedings. 2011.

- Shajan, K., et al., Locating the ancient port of Muziris: fresh findings from Pattanam. 2004, 17, 312-320. [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, G., et al., "Like sugar in milk": reconstructing the genetic history of the Parsi population. Genome Biol, 2017, 18, 110. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L., et al., Genetic affinities and adaptation of the South West coast populations of India. 2022, 2022.03. 14.484270. [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, V.M., et al., The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia. Science 2019, 365, eaat7487. [CrossRef]

- Cherian, P.J., et al., Chronology of Pattanam: a multi-cultural port site on the Malabar coast. Current Science. 2009, 97, 236–240.

- P J Cherian, J.M., Venu Vasudevan, Arundhati Chowdhury, Siddhartha Chatterjee, Sudha Gopalakrishnan, Unearthing Pattanam: Histories, Cultures, Crossings, in National Museum- Catalogue for the 2014 exhibition. 2014, Sahapedia: New Delhi.

- Tomber, R., The Roman Pottery from Pattanam, in Imperial Rome, Indian Ocean Regions and Muziris. 2016, Routledge. p. 381-394.

- Cherian, P.J. Pattanam excavations and explorations 2007 & 2008: an overview. in Space, Time, Place. Third International Conference on Remote Sensing in Archaeology 17th-21st August. 2009.

- Simoni, L., et al., Geographic patterns of mtDNA diversity in Europe. Am J Hum Genet 2000, 66, 262-78. [CrossRef]

- Pala, M., et al., Mitochondrial DNA signals of late glacial recolonization of Europe from near eastern refugia. Am J Hum Genet 2012, 90, 915-24. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., et al., The earliest settlers' antiquity and evolutionary history of Indian populations: evidence from M2 mtDNA lineage. BMC Evol Biol 2008. 8, 230. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, A., et al., Updating phylogeny of mitochondrial DNA macrohaplogroup m in India: dispersal of modern human in South Asian corridor. PLoS One 2009, 4, e7447. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I., et al., Ancient human migrations to and through Jammu Kashmir-India were not of males exclusively. 2018, 8, 851. [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, V.M., et al., The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia. 2018, 292581.

- Metspalu, M., M. Mondal, and G. Chaubey, The genetic makings of South Asia. Curr Opin Genet Dev, 2018. 53, 128-133. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).