Introduction

Public health in Brazil suffers from the lack of allocation of resources, being considered one of the biggest concerns in the lives of Brazilians. However, experts claim that this problem is not only based on funding, but also on the lack of qualified management of the health system [

1]. According to data from the Federal Court of Auditors (TCU), 64% of hospitals are always overcrowded and only 6% of them are not. In the analysis of the TCU, the allocation of patients in the corridors of hospital emergencies represents a problem in 47% of the evaluated hospitals, and in 33% this fact is always present and in 14% it is frequently reported [

1]. The TCU also pointed out other situations found in overcrowded Brazilian emergency rooms: patients lying on benches, insufficient space between beds, patients on stretchers at reception, patient identification posted on walls or stretchers, numbered beds in corridors, bodies curled up on the floor of the red room, patients waiting a long time for ICU vacancies, red room with low bed turnover and problems referring patients to other units [

1].

Faced with this situation, it is necessary to understand that the modern hospital institution is a complex organization, which must be able to offer quality and safe services to an increasingly informed and demanding public. In addition, it must take care of its own sustainability in the face of a competitive market, often suffocated by laws and demands from professional associations, in addition to having to be at the forefront of technological advances. For this to happen, a delicate balance is needed that is conducive to the development of hospital actions, a fact that depends on the management model geared towards new trends, but taking into account the appropriate relationship between cost and efficiency, in addition to always keeping a focus on quality care and patient safety. In order to transform the hospital into a competitive company, it is necessary that the hospital administration, in addition to becoming professional, adopt an adequate production model [

2].

Due to the need for a more effective management of always limited resources, some tools, commonly adopted in manufacturing, were adapted to the health system, among them highlighting what is known as "lean production (LP)" and is recognized by the term Lean Healthcare [

3]. This tool is a management method that allows, through simple steps that must be constantly observed, to identify what generates value for the patient and the points where waste occurs in a production chain. These waste points can thus be identified and eliminated or minimized. The previously wasted resources are then redirected to procedural steps that add value to the service offered [

4]. The first publications on the Lean Healthcare method occurred in 2002 [

5] and, since then, it has been implemented in several clinics and hospitals in several countries. Success stories are described in the literature with significant gains in numerous management parameters, such as the reduction of serious hospital complications, elimination of waste of various natures, reduction of waiting time for care, increase in the quality of the service provided and standardization of documentation and medical records, which can make hospital activities more efficient and safe [

4].

The present study aimed to analyze the effectiveness of the implementation of the Lean Healthcare system in the Emergency Room of the Hospital de Clínicas of the Federal University of Uberlândia (HC-UFU) from the comparison of hospital indicators obtained in the three phases corresponding to the period of one year before of implantation (T1), one year during implantation (T2) and one year after implantation (T3).

Material and Methods

Research Location and History of the Emergency Room of the Hospital de Clínicas of the Federal University of Uberlândia (HC-UFU)

HC-UFU is a Public University Hospital that works exclusively through the Unified Health System (SUS). HC-UFU accounts for the largest share of public health care in Minas Gerais, being third in the ranking of the largest university hospitals in the teaching network of the Ministry of Education (MEC). With an active physical area of more than 51.6 thousand m², it is a reference in medium and high complexity for 86 municipalities in the macro and micro regions of the Northern Triangle, serving a population of approximately 2,906,791 inhabitants (Source: SES/MG - Directorate of Integrated Agreed Programming). Built as a teaching unit for the professional cycle of the Medicine course at the former Uberlândia School of Medicine and Surgery, it was inaugurated on August 26, 1970 and began its activities in October of the same year, with only 27 beds [

6].

With the enactment of the 1988 Constitution, the HC-UFU became an important link in the SUS network, mainly for urgent and emergency and high-complexity care, being the only regional public hospital with an entrance door open 24 hours a day for all levels of health care [

6].

The constant search for high quality and reference assistance has led to the development of actions in order to offer comprehensive and humanized care, adapting the capacity to meet the demands of the SUS. Thus, there is a constant search for resources to ensure efficiency and effectiveness in the service, provide improvements in teaching, research and assistance, guaranteeing the quality of services provided to the population and integrating actions in a participatory manner.

Due to its importance and representativeness throughout the region, due to the particularities of being a teaching and care hospital, and due to the history of chronic problems related to overcrowding, lack of on-duty doctors, stretchers in the corridors, interventions by the Public Ministry, and dissatisfaction, both by health professionals and the population, HC-UFU was chosen for the implementation of Lean in Emergencies.

The HC-UFU Emergency Room currently has 92 beds, 18 of which are registered for Internal Medicine, 20 for General Surgery, 13 for Orthopedics, 12 for Gynecology and Obstetrics and 11 for Pediatrics. In addition, it has an eight-bed trauma room that serves as a gateway for more critically ill patients, and an emergency room with 10 beds; this structure plays a supporting role for patients who need intensive care [

6].

The construction of the HCU-UFU Emergency Room took place in 1980, and at the time, the population of Uberlândia was 240,967 thousand inhabitants; Since then, only renovations have taken place, without expanding the physical space. This situation is opposed by the fact that today the city has a population that exceeds 700 thousand inhabitants, according to the estimate made by the IBGE in 2022. Even so, this Emergency Room is still responsible for tertiary urgent and emergency care for the entire macro-region of Triângulo Mineiro and Alto Paranaíba, that is, it is a reference in hospital and outpatient care in medium and high complexity for the 86 municipalities of the state of Minas Gerais [

6].

On April 30, 2018, an operational excellence program based on the

Lean methodology was launched at HCU-UFU. The initiative of the Ministry of Health, through Proadi -SUS, created the Support Project for Strategic Actions. Through it, Hospital Sírio-Libanês, in São Paulo, developed this program that had already been implemented in emergency rooms of six other teaching hospitals in the SUS network [

6].

It is important to point out that due to the rotation of directors and technical teams that happened during the period of Lean implementation at HC-UFU, many original records of the technical team that implemented the system were lost and, therefore, part of the current research was carried out with based on general information obtained from the HC-UFU Statistics Sector and, in part, on the historical recovery made by the author of the present study and who effectively participated in the process of implementing Lean in Emergencies in the referred hospital.

The Search for Hospital Indicators

The present research was carried out based on the collection of local data referring to the experience of implementing Lean Healthcare, comparing hospital records before (T1), during (T2) and after (T3) the implementation of the project.

The search for this information was carried out in the Statistics Sector of the HC-UFU, using the experimental method with exploratory analysis of data related to the Emergency Room of the HC-UFU, having carried out a time series study with secondary data from the attendances occurred at the HC-UFU Emergency Room.

Data were analyzed using R software, version 4.2.1, used for data analysis and manipulation, along with Excel. With the aim of describing the study population, a descriptive analysis of all variables related to care was carried out. Thus, the cases were expressed in absolute and relative frequencies and, subsequently, descriptive statistics were used with measures of central tendency and dispersion of each variable in each analyzed period. Subsequently, the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare the parametric variables found in the three stages of the research, using the Tukey test as a post-hoc measure.

For trend analyses, rates were calculated, standardized by sex and using, as the standard population, population data from the municipality of Uberlândia found in the 2010 census and available on the DATASUS website. Then, trend analyzes were performed for all variables separated by gender.

Trend analyzes of the time series were performed by linear regression using the Prais-Winsten method with robust variance. With the calculation of the coefficient β and Standard Error (EP) obtained in the regression analysis, the Annual Percentage Variation (VPA) and respective Confidence Interval of 95% (CI 95%) were calculated. With this, it can be verified whether the trends were stationary (p >0.05), declining (p <0.05 and negative regression coefficient) or ascending (p <0.05 and positive regression coefficient), in each region of Minas Gerais, and stratified by gender and age group. For these analyses, the natural logarithmic transformation of the rates was carried out, which is capable of reducing the heterogeneity of the variance of the regression analysis residues. All data were considered significant with p-value <0.05.

The scores specific to Lean in Emergencies (NEDOCS and LOS) were only recorded during the period in which the implementation team was able to record them and were used only to demonstrate trends over time. Because the evaluation files corresponding to pre and post Lean were not found, substitute indicators that were closest to them were adopted for comparison between the study periods.

Another source of data refers to the practical experience of the author who, at the time of Lean implementation at HC-UFU, actively participated in the entire process of training, implementation, tutoring and monitoring of activities and all activities with the tutors of the Syrian-Lebanese Hospital. The author, who was also part of the Lean implementation team in Emergencies at the Hospital de Clínicas, actively participated in the negotiations with the Municipal Health Department of Uberlândia, the Public Prosecutor's Office, the Rectory of UFU and Hospital Sírio Libanês.

Throughout the study, there were also debates with other actors who participated in the implementation of Lean in Emergencies at Hospital de Clínicas. The discussions were guided in a technical way, analyzing the scenarios with impartiality and with a broader view, considering political and cultural factors, particularities of a university hospital and, mainly, the vision of the health system.

How the Implementation Process of Lean in Emergencies at HC-UFU Took Place

The steps for implementing “

Lean in Emergencies” at HC-UFU followed the following schedule: in April 2018, the project was joined; on May 25th and 26th, the initial diagnosis took place; from the 4th to the 6th of June there was the formation of the working group in São Paulo; on June 19, there was a meeting with managers and leaders to present the project and agreements; on the 20th and 21st of June, the first visit by the consultants of Hospital Sírio Libanês took place for the presentation of the diagnosis and construction of the map of values; On June 25th, the implementation of the 5S movement began, which originated in Japan in the late 1960s, as part of the country's post-World War II reconstruction process. It is a philosophy aimed at mobilizing all employees of an organization, through the implementation of changes in the work environment, including the elimination of waste. The method is called 5S because, in Japanese, words start with the letter S and represent each step of this method, Seiri: Organization, use and disposal; Seiton: Arrangement and ordering; Seisou: Cleanliness and hygiene; Seiketsu: Standardization; and Shitsuke which means discipline [

7]; on July 3, there was a meeting with the HC-UFU medical team to raise awareness and reach agreements; On July 20, the implementation of the 5W2H tool began, which is an action plan used to find a solution for a specific contingency of an organization, with the aim of identifying actions by establishing methods, deadlines and related resources . The methodology used represents the initials of the words in English: What (what will be done, steps), Why (why the task should be performed, justification), When (when each task will be performed, time), Where (where each step will be performed, location), How (how it will be performed, method) How much (how much each process will cost, cost) and How measure (how it will be measured or evaluated, monitoring) [

8].

On September 28, 2018, the fortnightly meetings with the consultancy ended, which became monthly, with a duration schedule with monitoring by the tutors of Hospital Sírio Libanês, for six months.

Description of the Lean System Implemented

Lean

Healthcare is based on a five-step process that, after adapting Lean principles [

9], was presented as: a) defining the customer's value to meet their needs, such as, for example, diagnostic exams and indicated therapy; b) mapping the value, which includes defining the activities from start to finish of the process steps; c) review the value stream to identify waste and solve them, that is, to adapt and be efficient in health care; d) pulling, defined by the ability to signal the pace of activities to the following stages, with a view to avoiding stocks and; e) the pursuit of perfection, a step that should drive the continuous improvement of

Lean Healthcar with timely and quality care [

5,

10].

Lean thinking consists of a systematic approach that allows the identification and elimination of waste in production processes, with the main focus on adding quality and delivering to the customer only what he considers as value. In other words,

Lean is the maximization of value for the customer through an efficient and wasteless process. In healthcare, this means providing services that respect and respond to patients' preferences and needs. Another principle is the elimination of activities that do not generate value along with other waste (such as long waits for care, steps taken twice, conflicting advice regarding treatment). This waste does not allow the patient to go through the care and treatment process without interruptions, detours, returns or waits. Thus, with the elimination of these activities, the efficiency of actions and the quality of care are increased simultaneously [

11].

However, longitudinal studies for monitoring the results of the implementation of

Lean in the long term and its consequences for institutions, teams and patients are still scarce. Systematic reviews point to the need to improve the quality of evidence, in addition to the use of clear terminology for

Lean Healthcare, converting the language of manufacturing into a language focused on health care [

11,

12,

13].

Results

For the study, and in accordance with the data found, April 30, 2018 was considered as the start date of the project. In the view of Mintzberg [

14], the application of the

Lean healthcare philosophy has been disseminated in several countries, since the early 2000s, through research and compilations of different cases, topics and approaches in health facilities. Its use in Brazil is considered recent [

15]. In this context, the

Lean philosophy attracts many researchers who base their use and exploration on their original concepts of lean manufacturing and transport them directly to the field of health [

16]. These studies, however, show that the concentration of

Lean applications is directed to its tools in specific areas or processes and not directly to the organization's culture [

17,

18].

As main indicators, the

Lean in Emergencies Project uses the

National Emergency Department Overcrowding Score (NEDOCS), English term for Overcrowding Scale of the National Emergency Department, to measure the number of patients in the Emergency Room and the risk arising from this overcrowding for its users, and also the Length

indicator of Stay (LOS) which measures the length of stay of the patient in the Emergency Room. These indicators are used to verify progress and identify possible irregularities in the process so that they can be corrected [

19], remembering that these indicators were only monitored at the beginning of the project:

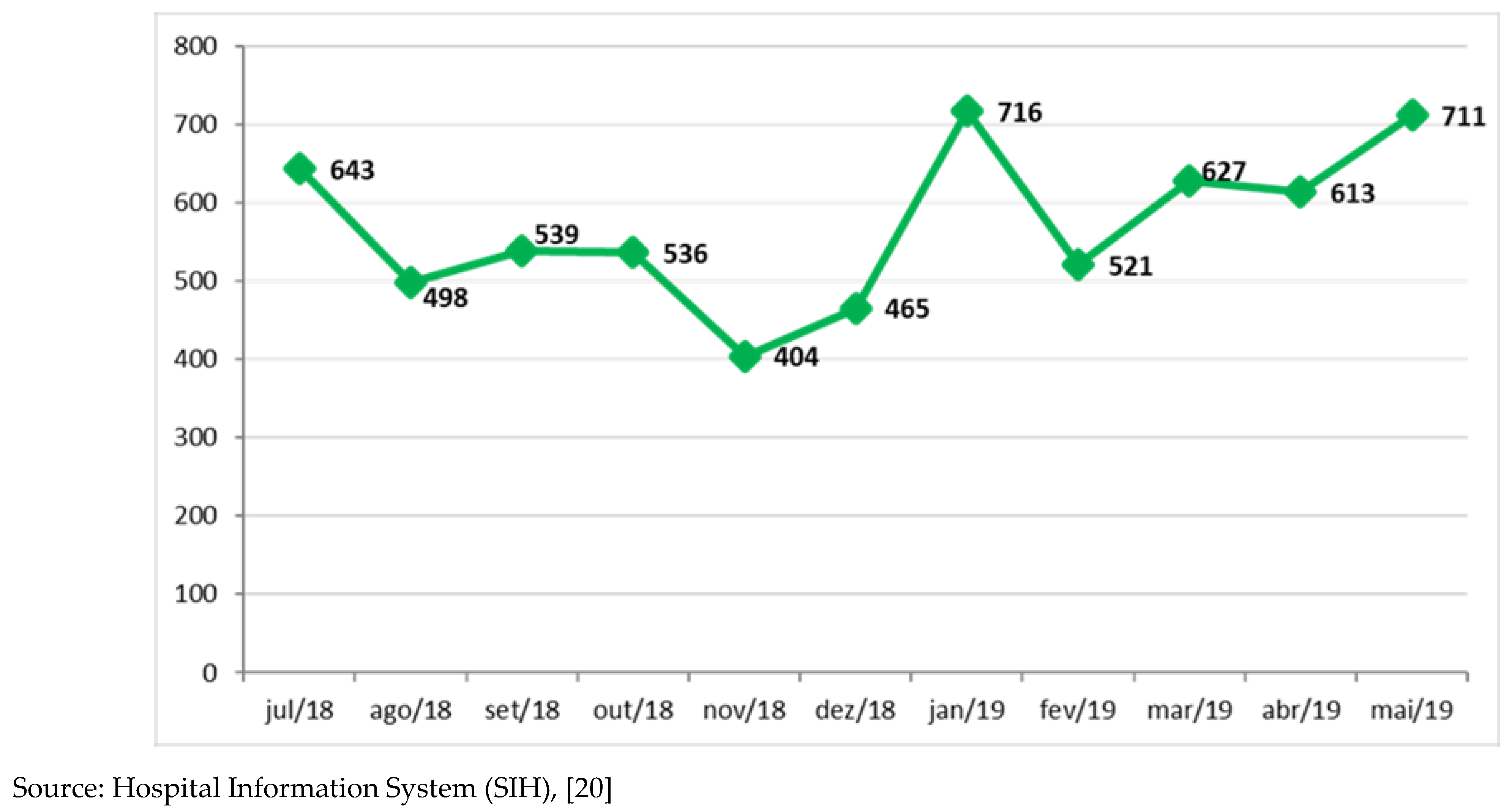

The NEDOCS score calculates the saturation/overcrowding in the emergency department, being the main indicator of the project; it lists several criteria to define Hospital overcrowding at a given time. It is desirable that the initiatives developed in the project result in the reduction of this indicator. An evolutionary history of the NEDOCS measurement, from July 2018 to May 2019, is shown in the graph below.

Graph 1. -Evolutionary history of the NEDOCS measurement.

Graph 1. -Evolutionary history of the NEDOCS measurement.

According to the NEDOCS score, data should be collected twice a day, and the data to be collected are the following: number of patients in the emergency department; care points in the emergency department, not counting extra beds; number of patients admitted and awaiting hospitalization in the hospital (with indication for hospitalization), that is, those who would not have indication to remain in the Emergency Room; number of effective hospital beds available to the emergency service, without considering deactivated beds, surgical block, or beds occupied for more than 90 days; number of patients on the respirator; longer hospital stay in hours, from entry into the emergency department to transfer to the destination unit; and waiting time for arrival at the bed, that is, the time between bed availability information and actual admission. As it was not possible to obtain the necessary data related to NEDOCS, in the three periods studied (T1, T2 and T3), we adapted indicators from the statistics sector that managed to approach a reality close to what was expected according to NEDOCS and LOS.

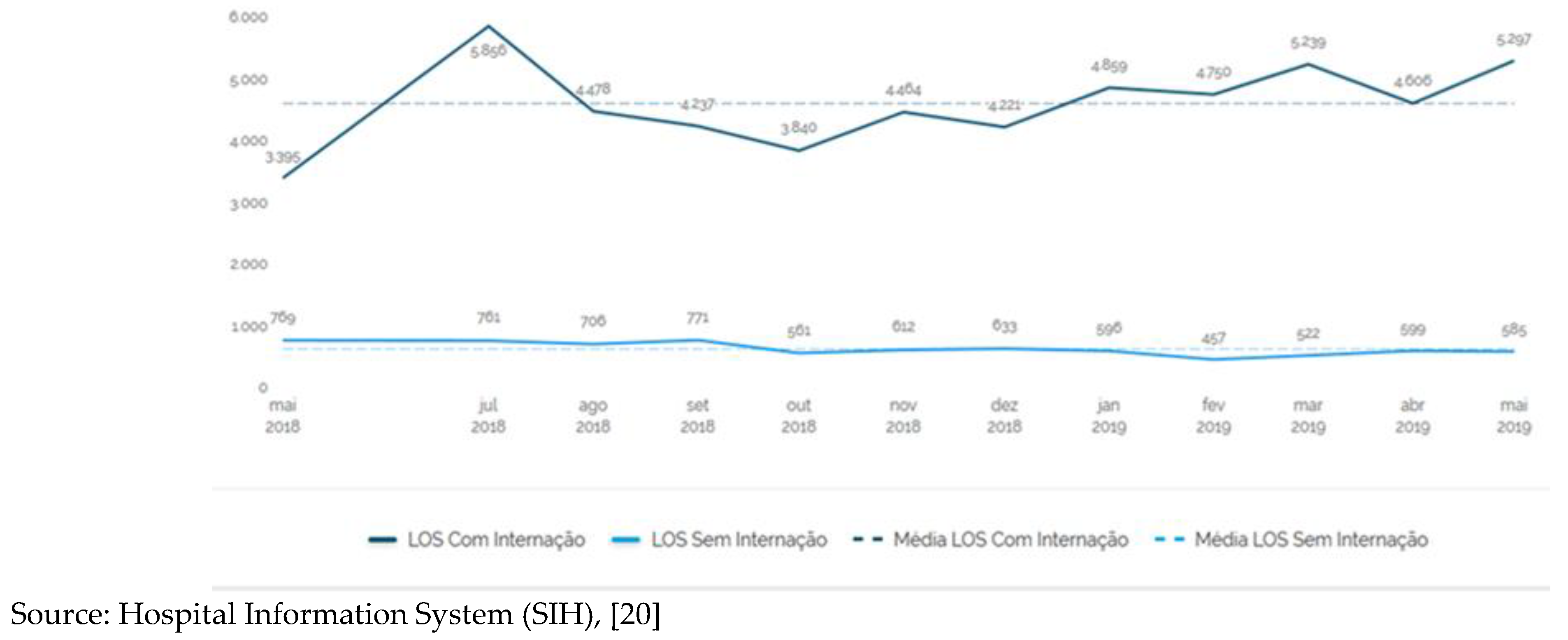

The Length of Stay (LOS) measures the length of stay of the patient in the Emergency Room. Data were stored from May 2018 to May 2019, and, in this period, the length of stay of patients remained high.

During the period in which it was possible to collect data related to the two indicators (NEDOCS and LOS), the teams' motivation was on the rise, with an increasing tension being observed between the municipal management and the hospital's management, with the involvement of the sphere judiciary, the rectory and representatives of all municipalities in the region. The tension culminated in the dismissal of the first director of HC-UFU on February 12, 2019, therefore during the implementation cycle of Lean in Emergencies.

Graph 2. -Length of Stay: length of stay of the patient in the Emergency Room.

Graph 2. -Length of Stay: length of stay of the patient in the Emergency Room.

It is verified in this period that, despite the oscillations, the length of stay of the patient in the Emergency Room remained high.

Indicators such as NEDOCS and LOS, which would be the main references for analyzing the implementation of the Lean project in emergencies and its results, were lost in the course of implementation. For the elaboration of the comparative analysis, and given the scarcity of available data, we selected some indicators that were closer to what we intended to research. The following indicators were defined: bed turnover rate or renewal rate; average discharge/day; average patient/day; average length of stay; discharge rate and unemployment rate in periods T1 (twelve months before implantation), T2 (twelve months during implantation) and T3 (twelve months after implantation).

For the study, and in accordance with the data found, April 30, 2018 was considered as the start date of the project. Information from the statistics sector, considering the daily census, was collected with the authorization of the HC- UFU.

Table 1.

–Relative and absolute frequency of consultations performed at PS/HC-UFU in Pre, Intra and Post-intervention.

Table 1.

–Relative and absolute frequency of consultations performed at PS/HC-UFU in Pre, Intra and Post-intervention.

| |

T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

|

| |

f |

% |

f |

% |

F |

% |

Total |

| Male hospitalization |

5463 |

31.9 |

5435 |

31.8 |

6206 |

36.3 |

17104 |

| Female hospitalization |

7412 |

32.0 |

7703 |

33.2 |

8058 |

34.8 |

23173 |

| High Male |

3085 |

33.8 |

2617 |

28.7 |

3419 |

37.5 |

9121 |

| Female High |

2732 |

34.1 |

2593 |

32.3 |

2692 |

33.6 |

8017 |

| male transfer |

2248 |

29.8 |

2676 |

35.4 |

2625 |

34.8 |

7549 |

| female transfer |

4607 |

31.0 |

5005 |

33.7 |

5226 |

35.2 |

14838 |

| Male death <24 h |

37 |

31.1 |

34 |

28.6 |

48 |

40.3 |

119 |

| Female death <24h |

27 |

40.3 |

13 |

19.4 |

27 |

40.3 |

67 |

| Male death >24 h |

88 |

25.5 |

104 |

30.1 |

153 |

44.3 |

345 |

| Female death >24h |

66 |

23.8 |

95 |

34.3 |

116 |

41.9 |

277 |

It is observed that, with the exception of the variable female deaths in less than 24 hours of hospitalization, all other variables showed percentage increases before and after the intervention.

In the stages analyzed, it is observed that there was a higher prevalence of female hospitalizations when compared to males (617.7; 641.92; 671.50 versus 455.3; 452.92; 517.17), respectively.

In the analysis of deaths that occurred in less than 24 hours and with more than 24 hours of hospitalization, there was a higher prevalence in males when compared to females, showing, in the three stages analyzed, (3.1, 2.83 and 4, 00 versus 2.00, 1.08 and 2.25) for less than 24 hours of hospitalization, respectively, and (7.00, 8.67 and 12.75 versus 6.00, 7.92 and 9.67) , respectively.

Table 2.

–Comparison between the averages of the various indicators found in the three stages before, during and after the intervention with the implementation of Lean Healthcare carried out at the PS/HC-UFU. Uberlandia, MG, Brazil. N (40,277).

Table 2.

–Comparison between the averages of the various indicators found in the three stages before, during and after the intervention with the implementation of Lean Healthcare carried out at the PS/HC-UFU. Uberlandia, MG, Brazil. N (40,277).

| Phases |

Average |

DP |

|

|

| CI95% |

CI95% |

p-value |

| |

1 |

455.25 |

31.73 |

435.09 |

475.41 |

<0.001* |

| Male hospitalization |

two |

452.92 |

35.93 |

430.09 |

475.75 |

0.988 |

| |

3 |

517.17 |

44.76 |

488.73 |

545.60 |

<0.001* |

| |

1 |

617.67 |

38.63 |

593.12 |

642.21 |

0.013* |

| Female hospitalization |

two |

641.92 |

35.51 |

619.36 |

664.48 |

0.211 |

| |

3 |

671.50 |

50.46 |

639.44 |

703.56 |

0.013* |

| |

1 |

257.08 |

17.22 |

246.14 |

268.03 |

<0.001* |

| High Male |

two |

218.08 |

26.70 |

201.12 |

235.05 |

<0.001* |

| |

3 |

284.92 |

23.26 |

270.14 |

299.70 |

<0.001* |

| |

1 |

227.67 |

22.26 |

213.53 |

241.81 |

0.481 |

| Female High |

two |

216.08 |

20.30 |

203.18 |

228.98 |

NC |

| |

3 |

224.33 |

28.37 |

206.31 |

242.36 |

NC |

| |

1 |

187.33 |

19.25 |

175.10 |

199.56 |

0.022* |

| male transfer |

two |

223.00 |

42.49 |

196.01 |

249.99 |

0.941 |

| |

3 |

218.75 |

27.27 |

201.42 |

236.08 |

0.049* |

| |

1 |

383.92 |

23.92 |

368.72 |

399.12 |

<0.001* |

| female transfer |

two |

417.08 |

19.10 |

404.94 |

429.22 |

0.152 |

| |

3 |

435.50 |

27.11 |

418.27 |

452.73 |

0.042* |

| |

1 |

3.08 |

1.83 |

1.92 |

4.25 |

0.279 |

| Male death < 24 h |

two |

2.83 |

1.75 |

1.72 |

3.94 |

NC |

| |

3 |

4.00 |

1.95 |

2.76 |

5.24 |

NC |

| |

1 |

2.25 |

1.29 |

1.43 |

3.07 |

0.013* |

| Female death < 24h |

two |

1.08 |

0.29 |

0.90 |

1.27 |

0.006* |

| |

3 |

2.25 |

0.97 |

1.64 |

2.86 |

0.963 |

| |

1 |

7.33 |

2.23 |

5.92 |

8.75 |

0.001* |

| Male death >24 h |

two |

8.67 |

2.74 |

6.92 |

10.41 |

0.587 |

| |

3 |

12.75 |

4.47 |

9.91 |

15.59 |

0.001* |

| |

1 |

5.50 |

1.68 |

4.43 |

6.57 |

0.023* |

| Female death > 24h |

two |

7.92 |

4.21 |

5.24 |

10.59 |

0.449 |

| |

3 |

9.67 |

4.05 |

7.09 |

12.24 |

0.017* |

As for the variables: male hospitalization, female hospitalization, male transfer, female transfer, male death after 24 hours and female death after 24 hours, all showed significant differences between the first and third stages, demonstrating an increase in the average number of hospitalizations. There was no significant difference between stage 2 and the others.

Male discharge and female death before 24 hours did not show an increase in means for the three stages.

The variables female transfer, female death less than 24 hours showed a significant difference between the first and second stages.

Table 3.

–Trend in rates of consultations performed at PS/HC/UFU. Uberlândia, MG, Brazil, 2017-2020. N = (40,277).

Table 3.

–Trend in rates of consultations performed at PS/HC/UFU. Uberlândia, MG, Brazil, 2017-2020. N = (40,277).

| |

β |

CI 95% |

CI 95% |

p-value |

APC |

CI 95% |

Interpretation |

| Male hospitalization |

0.0251 |

0.0109 |

0.0394 |

0.0010 |

2.5461 |

(1.14/3.97) |

Ascendant |

| Female hospitalization |

0.0136 |

-0.0001 |

0.0273 |

0.0511 |

1.3699 |

(0.04 / 2.72) |

stationary |

| High Male |

0.0283 |

-0.0081 |

0.0646 |

0.1234 |

2.8679 |

(-0.68/6.54) |

stationary |

| Female High |

-0.0015 |

-0.0254 |

0.0224 |

0.8990 |

-0.1505 |

(-2.43/2.18) |

stationary |

| male transfer |

0.0107 |

-0.0286 |

0.0499 |

0.5849 |

1.0723 |

(-2.69/4.98) |

stationary |

| female transfer |

0.0171 |

0.0040 |

0.0303 |

0.0121 |

1.7296 |

(0.4 / 3.03) |

Ascendant |

| Male death < 24 h |

0.0553 |

-0.0634 |

0.1739 |

0.3507 |

5.6822 |

(-5.7/18.51) |

stationary |

| Female death < 24h |

0.0435 |

-0.0521 |

0.1390 |

0.3622 |

4.4412 |

(-4.76/14.53) |

stationary |

| Male death >24 h |

0.1056 |

0.0585 |

0.1528 |

0.0001 |

11.1427 |

(6.20/16.32) |

Ascendant |

| Female death > 24h |

0.0904 |

0.0052 |

0.1755 |

0.0382 |

9.4557 |

(0.82/18.83) |

Ascendant |

Trend analysis throughout the period shows that hospitalizations related to males had a percentage growth trend of 2.54%, while for females the growth was 1.37% (p<0.058 and positive coefficient).

The variables male discharge, female discharge, male transfer, male and female death within 24 hours were stationary, although they showed fluctuation over the years (p >0.05).

Male and female mortality with more than 24 hours of hospitalization draws attention to an upward trend, with high percentages of 11.14% and 9.45% respectively (p <0.05 and positive coefficient).

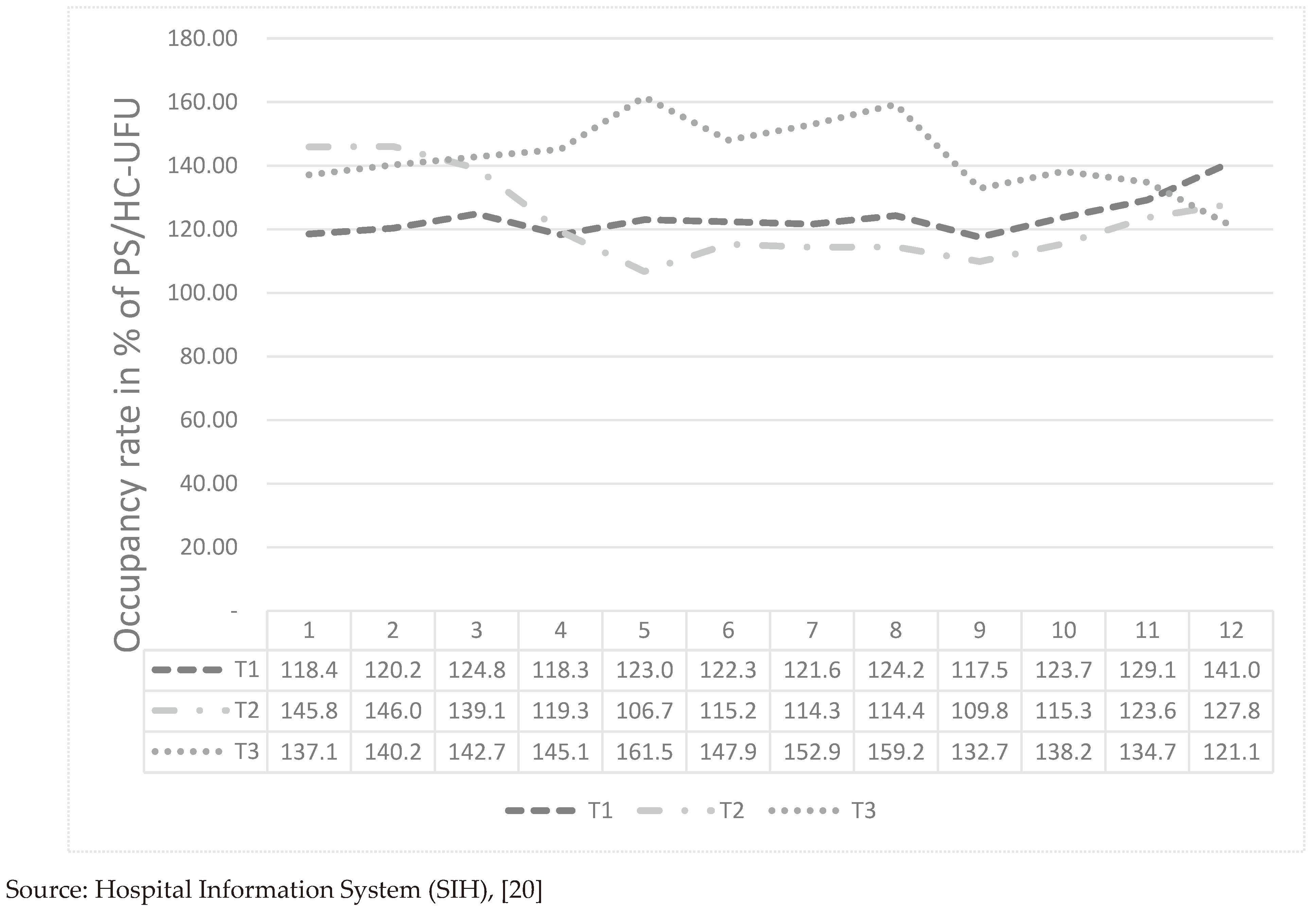

Graph 3. -Analysis of general occupancy rate of the PS/HC-UFU. Uberlandia, MG.

Graph 3. -Analysis of general occupancy rate of the PS/HC-UFU. Uberlandia, MG.

The graph above shows the general occupation analysis of the PS/HC-UFU, in the period of 36 months, between April 2017 and March 2020, being one year for stage T1 (April 2017 to March 2018), one year for stage T2 (April 2018 to March 2019) and one year for the T3 stage (April 2019 to March 202).

It can be seen, in this graph, that stage T1 started with an occupancy rate of 118.4% and ended with 141.0%, in March/2018. Stage T2 had an occupancy rate of 145.8% in April/2018, dropping to 106.7% in August/2020, and ending in March/2019 with an occupancy rate of 127.8%. Finally, stage T3 had an occupancy rate of 137.1% in April/2019 and was more pronounced in August/2019, totaling 161.5% occupancy rate.

Discussion

The present case study, of a descriptive and exploratory nature, evaluated the results obtained with the implementation of a management system that has been implemented in several health services, the Lean Healthcare. Theoretically, this system is a health management method that allows identifying points where waste occurs in a production chain. Once identified, they become subject to correction and can be changed or cancelled. By doing so, resources can be redirected to other fronts of action aimed at improving the quality of services as a whole.

A modern and multifaceted hospital, which intends to be competitive, must organize its services by improving care, creating favorable conditions for its internal public and, mainly, the external public, understanding its users here, and optimizing its finite resources. Among the services that need to be properly organized, Emergency Room stands out due to its complexity and range of actions. Urgent and emergency care must be planned, programmed and operationalized to meet the principles of the SUS and improve the resolution and satisfaction of the care team and the user of the health system. However, due to structural deficiencies of the health system, the Emergency Room services end up constituting the gateway to hospitals and represent, for the user, the possibility of access to a more resolvable and complex care [21].

The application of

Lean in Emergencies at HC-UFU it had no impact on the indicators used in the study when comparing the pre (T1), contemporaneous (T2) and subsequent (T3) periods to its implementation. According to the study by Soliman and Saurin [

18], cultural and practical barriers must be overcome for a correct and effective dissemination of the application of the

Lean philosophy in the health sector. Kim et al. [22] and D' andreamatteo et al. [

12] stated that the readiness of response, on the part of technical health professionals, to cultural change, is a positive and decisive factor in the implementation of

Lean healthcare in health units. However, contemporaneously with the implementation, there was a monthly follow-up with the indicators and there was no change in their components. In fact, several factors may have influenced this result. One of them concerns the complexity of the Emergency Room sector. It is known that urgent and emergency assistance is quite complex, considering the various factors involved, such as the open-door policy that brings with it unpredictability, the need for differentiated assistance in cases of violence and accidents that are more common in large urban centers, the diffusion of pre-hospital emergency care services, the process of transferring the management of the public health system to municipalities, the multiple interests of managers and service providers, the lack of experience of many managers and expectations of full assistance on the part of the population. In addition to these challenging circumstances, there are structural weaknesses in the health system.

Analyzing the behavior of the intrinsic scores of Lean in Emergencies (NEDOCS and LOS) registered only during the period of system operation, it turns out that they also showed no tendency to improve. This demonstrates that an eventual blinding of results, due to the use of substitutive criteria for the creation of quality scores, apparently did not occur in the present study.

Regardless of the difficulty in addressing this issue, the main justification for investing in emergency services should continue to be social and health responsibility, that is, achieving a reduction in morbidity and mortality [23]. Therefore, the development and application of better management tools should be a goal in any Emergency Room administration.

Another factor to be considered when analyzing the failure to obtain the desired results with the application of Lean in emergencies involves the techniques employed in its implementation, the motivational climate found in the Emergency Room and aspects of a political-administrative nature that were in course at that time. During the period of implantation and implementation of the system, the two indicators (NEDOCS and LOS) were monitored and the teams found themselves with high motivation, although an increasing tension could be observed between the municipal management and the hospital management, with involvement of the judiciary sphere, the rectory and representatives of the region's municipalities. The tension culminated in the dismissal of the first director of HC-UFU on February 12, 2019, therefore, during the implementation cycle of Lean in Emergencies. Still as an aggravating factor, during the period of the study there was already a movement that would result in the transfer of the management of the HC-UFU from the original management support foundation of the hospital, the Fundação de Assistência, Estudos e Pesquisa de Uberlândia (FAEPU), to the Brazilian Company de Serviços Hospitalares (EBSERH), which is a public company governed by private law, linked to the Ministry of Education, whose purpose is to provide medical and hospital assistance services. This situation certainly produced uneasiness and uncertainty among the hospital's workers [23], mainly due to the fact that, among the objectives of the EBSERH, was the replacement of FAEPU workers for EBSERH candidates.

The present research also looked for references that could allow the comparison of the indicators of other processes of implantation of the Lean methodology and of its results, carried through in other units of Emergency Room than the one of the HC- UFU. For this, an extensive systematic review (SR) of the literature was carried out, but, unfortunately, the methodology used in the review resulted in little information being found.

In an isolated article, Soliman and Saurin [

18] carried out an analysis of the

Lean implementation processes

Healthcare in five Brazilian hospitals, and the complexity of system implementation is frequently mentioned in the publication and attributed to the unpredictability, variability of treatments and necessary tests.

Costa et al. [

5] analyzed five

Lean implementation processes carried out in two Brazilian hospitals, however, they did not demonstrate the detailed sequence of steps for the implementation of lean practices (LP), nor did they extract experiences that could be translated into guidelines with the potential to help other operations of lean. health in the implementation of PE. In addition, Radnor, Holweg and Waring [

16] state that most studies on

Lean healthcare are not comparative, being developed, in most cases, through isolated case studies. In our SR, we did not find structured research that used criteria and indicators of

Lean in the Emergency Room similar to those that were analyzed throughout the present work, a fact that makes it impossible to compare with other experiences that have already been carried out.

It was also used in the methodology of the current research, the own experience of the author who actively participated in the implementation process of the new management methodology. This experience is contained in many observations issued throughout the text and contribute to a better understanding of the work.

Only a few points of these observations will be highlighted here. As previously described, the NEDOCS and LOS indicators were lost during the implementation of Lean in Emergencies at HC-UFU, largely as a result of the changes that occurred in the institution's top management and the local problems that arose during the process.

Another aspect that can be highlighted was the moment in history when the decision to participate in the project was taken, which, as happens in practically all cases, came from the top institutional leadership. It was not, therefore, a process that matured for a long time and whose need had been understood and incorporated by the internal and external communities of the unit. This aspect added uncertainties, insecurities and lack of commitment to planning, communication, and the changes that would be adopted.

These facts suggest that the complexity of implementing management changes, whatever they may be, becomes smaller when the high institutional hierarchy understands, supports and encourages, from the knowledge awareness process to the implementation in hospital units; it is palpable that the involvement of senior institutional and extra-institutional leadership and the commitment of employees in all processes ensure that changes are not lost [

18,24].

It can be assumed that the failure to implement Lean in the HC-UFU Emergency Room may, in large part, have been due to changes in hospital management, to the movements that occurred in response to the change of workers from FAEPU to EBSERH and the constant conflicts between the hospital management, health managers, representatives of the judiciary and other actors involved in the process.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the analyzed results did not demonstrate a permanent evolution of improvement in working conditions or in the quality of care provided by the unit, facts that are mainly reflected in the behavior of the occupancy rate of the Emergency Room and in the other indicators studied.

Conclusions

It is known that structural change in an institution, such as the one intended with the implementation of Lean Healthcare in the Emergency Room of HC-UFU, requires previous cultural and philosophical changes, which necessarily implies a lot of commitment from the hospital management and other actors, such as municipal and regional managers, the public ministry, the press, representative bodies of society and the professional training academy, requiring efficient communication that is fundamental for the success of the enterprise, which in fact did not occur.

Lean in Emergencies project is people-dependent and one of the biggest challenges is to engage them in the project and promote the necessary cultural changes. Therefore, the implementation requires political and social stability of the hospital unit, without turbulence and without unexpected change of managers who may not agree with the ongoing changes. The intended change in management naturally implies a different view of the same object, and the political and technical spaces need balance to move forward and achieve the objectives of the proposal.

Considering the cultural aspect of the institution, the training of doctors and other health professionals introduces parameters that are different from those present in hospitals that do not train these professionals; they certainly. are on the scene in the behavior of the analyzed indicators and need to be respected and considered in the final assessment of management results.

There is no doubt about the need to improve management flows and processes to speed up discharge and provide quality care to patients who arrive at the Emergency Room with different health conditions, and one of the points to be highlighted is that we need to improve the internal flow, prioritizing the best service, with greater agility and directing the patient to the most suitable place so as not to remain in the emergency room for longer than expected.

The operation of the Emergency Room with open doors needs to be reassessed and, if modified, it must be previously replaced by other health units previously planned and put into operation so as not to cause harm to the health of users.

The communication of the implementation process of Lean in Emergencies was one of its weak points, both internally and externally, a fact that may have generated and aggravated resistance to the proposal and brought misunderstanding about what its final purpose would be.

The study allows us to conclude that the general objective of the project, which was to reduce overcrowding in the HC-UFU urgencies and emergencies, did not materialize. This evidence generated low expectations of the author of the project at the institution when he found that the numbers collected during the work were not convincing and could not demonstrate the success of its implementation in the Emergency Room of HC-UFU.

Given the situation found by the study, a new critical look at the data presented was awakened and thus, the absence of favorable results at that time, can help to improve the process.

Nothing better than recognizing the deficiencies and using them as positive experiences for the continuous improvement of the work, even more so considering that Lean in Emergencies continues to occur in other public hospital units and this work may facilitate reducing the margin of error s during implementation.

References

- Brasil. Tribunal de Contas da União. Relatório Sistêmico de Fiscalização: saúde. Brasília, DF: Tribunal de Contas da União, 2014. 250 p.

- Silva, T.O. et al. Gestão hospitalar e gerenciamento em enfermagem à luz da filosofia Lean Healthcare. Cogitare Enfermagem, 2019, 24, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Régis, T.K.O.; Gohr, C.F.; Santos, L. C. Lean healthcare implementation: experiences and lessons learned from Brazilian hospitals. Rev. Adm. Empres., 2018, 58, 1. [CrossRef]

- Inacio, B.C.; Aragao, J.F.; Bergiante, N.C. Implementação da Metodologia Lean Healthcare no Brasil: um Estudo Bibliométrico. In: Encontro Nacional de Engenharia de Produção, 36., 2016, João Pessoa. Anais XXXVI Encontro... João Pessoa: ABEPRO, 2016, 1-16. Disponível em: http://www.abepro.org.br/biblioteca/TN_WIC_226_316_30373.pdf. Acesso em: 19/10/2021.

- Costa, L.B.M.; Godinho Filho, M.; Rentes, A.F.; Bertani, T.M.; Mardegan, R. Lean healthcare in developing countries: evidence from Brazilian hospitals. Int J Health Plann Mgmt., 2015, 32, 1. [CrossRef]

- Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Uberlândia. Apresentação do Hospital de Clínicas de Uberlândia. 2022. Disponível em <http://www.hc.ufu.br/pagina/institucional>. Acesso em: [15 set 2022].

- Marshall Junior, I. et al. Gestão da Qualidade. 9. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Fgv, 2008. 204 p. (Gestão Empresarial).

- Alves, V.L.S. Gestão da Qualidade: Ferramentas utilizadas no contexto contemporâneo da saúde. 2. ed. São Paulo: Editora Martinari, 2012.

- Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T. Beyond Toyota: how to root out waste and pursue perfection. Harvard Bus Rev., 1996, 74, 5, 140-58.

- Hussain, M.; Malik, M.; Al Neyadi, H.S. AHP framework to assist lean deployment in Abu Dhabi public healthcare delivery system. Bus Process Manag J., 2016, v. 22, n. 3, p. 546-65, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, A.L.P.; Erdmann, A.L.; Silva, E.L.; Santos, J.L.G. Lean thinking in health and nursing: an integrative literature review. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem., 2016, 24. Disponível em:. [CrossRef]

- D’Andreamatteo, A.; Ianni, L.; Lega, F.; Sargiacomo, M. Lean in healthcare: a comprehensive review. Health Policy, 2015, 119, 9, 1197-209. [CrossRef]

- Amaratunga, T.; Dobranowski, J. Systematic review of the application of Lean and Six Sigma quality improvement methodologies in radiology. J Am Coll Radiol., 2016, 13, 9, 1088-95.e7. [CrossRef]

- Lawal, A.K. et al. Lean management in health care: definition, concepts, methodology and effects reported (systematic review protocol). Syst Rev., 2014, 3, 103. [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H. Managing the myths of health care, World Hosp. Health Serv. Journal International Hospital Federation, 2012, 48, 3, 4-7. PMID: 23342753.

- Houchens, N.; Kim, S.C. The Application of Lean in the Healthcare Sector: Theory and Practical Examples. Lean Thinking for Healthcare, Springer New York, 2014, 43-53.

- Radnor, Z.J.; Holweg, M.; Waring, J. Lean in Healthcare: The unfilled promise? Social Science & Medicine, 2012, 74, 364-371. [CrossRef]

- Haenke, R.; Stichler, J.F. Applying Lean Six Sigma for innovative change to the post-anesthesia care unit. J Nurs Adm., 2015, 45, 4, 185-7. [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M.; Saurin, T.A. Uma análise das barreiras e dificuldades em lean healthcare. Revista Produção Online, 2017, 17, 2, 620-640. [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Projeto Lean nas Emergências: Redução das Superlotações Hospitalares. Governo Federal. 2020. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/saude-de-a-a-z/l/projeto-lean-nas-emergencias. Acesso em: 24/10/2021.

- Sistema de Informações Hospitalares. Relatório do LEAN HCU. Setor de Estatísticas. Hospital de Clínicas de Uberlândia. Universidade Federal de Uberlândia. 2022.

- Coelho, I.B. Os Hospitais no Brasil. São Paulo: Hucitec, 2016.

- Kim, C. S.; et al. Lean health care: what can hospitals learn from a world-class automaker? Journal of Hospital Medicine, 2006, 1, 3, 191-199. [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, G.; Oliveira, S.P.; Seta, M. H. Avaliação dos serviços hospitalares de emergência do programa QualiSUS. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 2009, 14, 5, 881-1890. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.F.; Battaglia, F. Aplicando Lean na Saúde. Lean Institute Brasil. 2014. Disponível em: https://www.lean.org.br/artigos/262/aplicando-lean-na-saude.aspx. Acesso em: [19 out 2019].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).