Submitted:

09 March 2023

Posted:

10 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Job Demands/Resources and the Allostatic Load Model

1.2. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

Psychological Measures

2.2. Biological Measures

2.2.1. Hair Collection

2.2.2. Sample Preparation

2.2.3. Hair Hormone (Cortisol and DHEA(S)) Analysis

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- Leger, K.A.; Lee, S.; Chandler, K.D.; Almeida, D.M. Effects of a Workplace Intervention on Daily Stressor Reactivity. J Occup Health Psychol 2022, 27, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messenger, J.; Llave, O.V.; Gschwind, L.; Boehmer, S.; Vermeylen, G.; Wilkens, M. Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work; International Labour Organization and the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound) & International Labour Organization (ILO): Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Qian, J.; Parker, S.K. Achieving Effective Remote Working during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Work Design Perspective. Appl Psychol 2021, 70, 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, T.D.; Golden, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. How Effective Is Telecommuting? Assessing the Status of Our Scientific Findings. Psychol Sci Public Interest 2015, 16, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajendran, R.S.; Harrison, D.A. The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown about Telecommuting: Meta-Analysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences. J Appl Psychol 2007, 92, 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Working from Home: From Invisibility to Decent Work; International Labour Organization (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Marino, L.; Capone, V. Smart Working and Well-Being before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ 2021, 11, 1516–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albano, R.; Parisi, T.; Tirabeni, L. Gli Smart Workers Tra Solitudine e Collaborazione. Cambio 2019, 9, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carlo, A.; Girardi, D.; Dal Corso, L.; Arcucci, E.; Falco, A. Out of Sight, out of Mind? A Longitudinal Investigation of Smart Working and Burnout in the Context of the Job Demands–Resources Model during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappalà, S.; Toscano, F.; Topa, G. The Implementation of a Remote Work Program in an Italian Municipality before COVID-19: Suggestions to HR Officers for the Post-COVID-19 Era. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ 2021, 11, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todisco, L.; Tomo, A.; Canonico, P.; Mangia, G. The Bright and Dark Side of Smart Working in the Public Sector: Employees’ Experiences before and during COVID-19. Manag Decis 2023, 61, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, T.; Guidetti, G.; Mazzei, E.; Zappalà, S.; Toscano, F. Work from Home during the COVID-19 Outbreak. J Occup Environ Med 2021, 63, e426–e432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telework in the EU before and after the COVID-19: Where We Were, Where We Head To; Joint Research Centre of the European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Corso, M. Il Ruolo e Le Prospettive Dello Smart Working Nella PA Oltre La Pandemia.; January 25 2021.

- Osservatorio Smart Working Gli Smart Worker Italiani Scendono a 3,6 Milioni, Previsioni Di Crescita Nel 2023; 2022.

- OECD Implications of Remote Working Adoption on Place Based Policies: A Focus on G7 Countries; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, 2021.

- Baumann, O.; Sander, E. (Libby) J. Psychological Impacts of Remote Working under Social Distancing Restrictions. In Handbook of Research on Remote Work and Worker Well-Being in the Post-COVID-19 Era; Wheatley, D., Hardill, I., Buglass, S., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-1-79986-754-8. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Job Demands-Resources Model of Burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganster, D.C.; Rosen, C.C. Work Stress and Employee Health: A Multidisciplinary Review. J Manage 2013, 39, 1085–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu Rev Psychol 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juster, R.-P.; McEwen, B.S.; Lupien, S.J. Allostatic Load Biomarkers of Chronic Stress and Impact on Health and Cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010, 35, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeman, T.; Epel, E.; Gruenewald, T.; Karlamangla, A.; McEwen, B.S. Socio-Economic Differentials in Peripheral Biology: Cumulative Allostatic Load. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010, 1186, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidi, J.; Lucente, M.; Sonino, N.; Fava, G.A. Allostatic Load and Its Impact on Health: A Systematic Review. Psychother Psychosom 2021, 90, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriquez, E.J.; Kim, E.N.; Sumner, A.E.; Nápoles, A.M.; Pérez-Stable, E.J. Allostatic Load: Importance, Markers, and Score Determination in Minority and Disparity Populations. J Urban Health 2019, 96, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maninger, N.; Wolkowitz, O.M.; Reus, V.I.; Epel, E.S.; Mellon, S.H. Neurobiological and Neuropsychiatric Effects of Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA Sulfate (DHEAS). Front Neuroendocrinol 2009, 30, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theorell, T.; Engström, G.; Hallinder, H.; Lennartsson, A.-K.; Kowalski, J.; Emami, A. The Use of Saliva Steroids (Cortisol and DHEA-s) as Biomarkers of Changing Stress Levels in People with Dementia and Their Caregivers: A Pilot Study. Science Progress 2021, 104, 00368504211019856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Li, X.; Zilioli, S.; Chen, Z.; Deng, H.; Pan, J.; Guo, W. Hair Measurements of Cortisol, DHEA, and DHEA to Cortisol Ratio as Biomarkers of Chronic Stress among People Living with HIV in China: Known-Group Validation. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0169827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunde, L.-K.; Fløvik, L.; Christensen, J.O.; Johannessen, H.A.; Finne, L.B.; Jørgensen, I.L.; Mohr, B.; Vleeshouwers, J. The Relationship between Telework from Home and Employee Health: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Macêdo, T.A.M.; Cabral, E.L. dos S.; Silva Castro, W.R.; de Souza Junior, C.C.; da Costa Junior, J.F.; Pedrosa, F.M.; da Silva, A.B.; de Medeiros, V.R.F.; de Souza, R.P.; Cabral, M.A.L.; et al. Ergonomics and Telework: A Systematic Review. Work 2020, 66, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakman, J.; Kinsman, N.; Stuckey, R.; Graham, M.; Weale, V. A Rapid Review of Mental and Physical Health Effects of Working at Home: How Do We Optimise Health? BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buomprisco, G.; Ricci, S.; Perri, R.; Sio, S.D. Health and Telework: New Challenges after COVID-19 Pandemic. EUR J ENV PUBLIC HLT 2021, 5, em0073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckel, J.L.O.; Fisher, G.G. Telework and Worker Health and Well-Being: A Review and Recommendations for Research and Practice. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, U.; Lindfors, P. Psychophysiological Reactions to Telework in Female and Male White-Collar Workers. J Occup Health Psychol 2002, 7, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, A.; Girardi, D.; Marcuzzo, G.; De Carlo, A.; Bartolucci, G.B. Work Stress and Negative Affectivity: A Multi-Method Study. Occup Med (Lond) 2013, 63, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, A.E.; Mazzola, J.J.; Bauer, J.; Krueger, J.R.; Spector, P.E. Can Work Make You Sick? A Meta-Analysis of the Relationships between Job Stressors and Physical Symptoms. Work Stress 2011, 25, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A Critical Review of the Job Demands-Resources Model: Implications for Improving Work and Health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach; Bauer, G.F., Hämmig, O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 43–68. ISBN 978-94-007-5640-3. [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedl, A. The Demands-Buffering Role of Perceived and Received Social Support for Perceived Stress and Cortisol Levels. Eur J Health Psychol 2022, 29, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Protective and Damaging Effects of Stress Mediators. N Engl J Med 1998, 338, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B. Towards a Multilevel Approach of Employee Well-Being. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 2015, 24, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Aw, S.S.Y.; Pluut, H. Intraindividual Models of Employee Well-Being: What Have We Learned and Where Do We Go from Here? Eur J Work Organ Psychol 2015, 24, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, A.; Dal Corso, L.; Girardi, D.; De Carlo, A.; Comar, M. The Moderating Role of Job Resources in the Relationship between Job Demands and Interleukin-6 in an Italian Healthcare Organization. Res Nurs Health 2018, 41, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, R.; McHugh, M.; McCrory, M. HSE Management Standards and Stress-Related Work Outcomes. Occup Med (Lond) 2009, 59, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfering, A.; Grebner, S.; Ganster, D.C.; Berset, M.; Kottwitz, M.U.; Semmer, N.K. Cortisol on Sunday as Indicator of Recovery from Work: Prediction by Observer Ratings of Job Demands and Control. Work Stress 2018, 32, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, S.A.E.; Sonnentag, S. Recovery as an Explanatory Mechanism in the Relation between Acute Stress Reactions and Chronic Health Impairment. Scand J Work Environ Health 2006, 32, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowling, N.A.; Alarcon, G.M.; Bragg, C.B.; Hartman, M.J. A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Potential Correlates and Consequences of Workload. Work & Stress 2015, 29, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.R.; LePine, J.A.; Rich, B.L. Linking Job Demands and Resources to Employee Engagement and Burnout: A Theoretical Extension and Meta-Analytic Test. J Appl Psychol 2010, 95, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, G.M. A Meta-Analysis of Burnout with Job Demands, Resources, and Attitudes. J Vocat Behav 2011, 79, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A. Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude, and Mental Strain: Implications for Job Redesign. Adm Sci Q 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.V.; Hall, E.M. Job Strain, Work Place Social Support, and Cardiovascular Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study of a Random Sample of the Swedish Working Population. Am J Public Health 1988, 78, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse Health Effects of High-Effort/Low-Reward Conditions. J Occup Health Psychol 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J.A.; Webster, S.; Laar, D.V.; Easton, S. Psychometric Analysis of the UK Health and Safety Executive’s Management Standards Work-Related Stress Indicator Tool. Work Stress 2008, 22, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Motivation through the Design of Work: Test of a Theory. Organ Behav Hum Perform 1976, 16, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. A Conceptual Framework for the Study of Work and Mental Health. Work Stress 1994, 8, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.L.; Schaubroeck, J.; Lam, S.S.K. Theories of Job Stress and the Role of Traditional Values: A Longitudinal Study in China. J Appl Psychol 2008, 93, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N.A.; Kirkendall, C. Workload: A Review of Causes, Consequences, and Potential Interventions. In Contemporary occupational health psychology: Global perspectives on research and practice; Houdmont, J., Leka, S., Sinclair, R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2012; Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- De Carlo, A.; Girardi, D.; Falco, A.; Dal Corso, L.; Di Sipio, A. When Does Work Interfere with Teachers’ Private Life? An Application of the Job Demands-Resources Model. Front Psychol 2019, 10, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilies, R.; Aw, S.S.Y.; Lim, V.K.G. A Naturalistic Multilevel Framework for Studying Transient and Chronic Effects of Psychosocial Work Stressors on Employee Health and Well-Being. Appl Psychol 2016, 65, 223–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Humphrey, S.E. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and Validating a Comprehensive Measure for Assessing Job Design and the Nature of Work. J Appl Psychol. 2006, 91, 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J Manage Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väänänen, A.; Toppinen-Tanner, S.; Kalimo, R.; Mutanen, P.; Vahtera, J.; Peiró, J.M. Job Characteristics, Physical and Psychological Symptoms, and Social Support as Antecedents of Sickness Absence among Men and Women in the Private Industrial Sector. Soc Sci Med 2003, 57, 807–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, M.; Garst, H.; Fay, D. Making Things Happen: Reciprocal Relationships between Work Characteristics and Personal Initiative in a Four-Wave Longitudinal Structural Equation Model. J Appl Psychol 2007, 92, 1084–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabiu, A.; Pangil, F.; Othman, S.Z. Does Training, Job Autonomy and Career Planning Predict Employees’ Adaptive Performance? Glob Bus Rev 2020, 21, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saragih, S. The Effects of Job Autonomy on Work Outcomes: Self Efficacy as an Intervening Variable. Int Res J Bus Stud 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, K.; Cieslak, R.; Smoktunowicz, E.; Rogala, A.; Benight, C.C.; Luszczynska, A. Associations between Job Burnout and Self-Efficacy: A Meta-Analysis. Anxiety Stress Coping 2016, 29, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilo, R.A.; Hassmén, P. Burnout and Turnover Intentions in Australian Coaches as Related to Organisational Support and Perceived Control. Int J Sports Sci Coach 2016, 11, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, G.; Eschleman, K.J.; Bowling, N.A. Relationships between Personality Variables and Burnout: A Meta-Analysis. Work Stress 2009, 23, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.M.; Bakker, A.B.; Pignata, S.; Winefield, A.H.; Gillespie, N.; Stough, C. A Longitudinal Test of the Job Demands-Resources Model among Australian University Academics. Appl Psychol 2011, 60, 112–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Ishikawa, H.; Liu, L.; Ohwa, M.; Sawada, Y.; Lim, H.Y.; Kim, H.Y.; Choi, Y.; Cheung, C. The Effects of Job Autonomy and Job Satisfaction on Burnout among Careworkers in Long-Term Care Settings: Policy and Practice Implications for Japan and South Korea. Educ Gerontol 2018, 44, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Teoh, K.R.; Islam, S.; Hassard, J. Psychosocial Work Characteristics, Burnout, Psychological Morbidity Symptoms and Early Retirement Intentions: A Cross-Sectional Study of NHS Consultants in the UK. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e018720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charalampous, M.; Grant, C.A.; Tramontano, C.; Michailidis, E. Systematically Reviewing Remote E-Workers’ Well-Being at Work: A Multidimensional Approach. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 2019, 28, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd-Banigan, M.; Bell, J.F.; Basu, A.; Booth-LaForce, C.; Harris, J.R. Workplace Stress and Working from Home Influence Depressive Symptoms among Employed Women with Young Children. Int J Behav Med 2016, 23, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden, T.D.; Gajendran, R.S. Unpacking the Role of a Telecommuter’s Job in Their Performance: Examining Job Complexity, Problem Solving, Interdependence, and Social Support. J Bus Psychol 2019, 34, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The Influence of Culture, Community, and the Nested-Self in the Stress Process: Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory. Appl Psychol 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, M.; Hobfoll, S.E.; Chen, S.; Davidson, O.B.; Laski, S. Organizational Stress through the Lens of Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory. In Exploring interpersonal dynamics; Perrewé, P.L., Ganster, D.C., Eds.; Research in occupational stress and well-being; Elsevier Science/JAI Press: US, 2005; pp. 167–220. ISBN 978-0-7623-1153-8. [Google Scholar]

- Boell, S.K.; Cecez-Kecmanovic, D.; Campbell, J. Telework Paradoxes and Practices: The Importance of the Nature of Work. New Technol Work Employ 2016, 31, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, T.A.; Teo, S.T.T.; McLeod, L.; Tan, F.; Bosua, R.; Gloet, M. The Role of Organisational Support in Teleworker Wellbeing: A Socio-Technical Systems Approach. Appl Ergon 2016, 52, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilbrecht, M.; Shaw, S.M.; Johnson, L.C.; Andrey, J. Remixing Work, Family and Leisure: Teleworkers’ Experiences of Everyday Life. New Technol Work Employ 2013, 28, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğdu, A.İ.; Watson, F. Millennials’ Changing Mobility Preferences: A Telecommuting Case in Istanbul. J Consum Behav n/a. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S. Does Telecommuting Promote Sustainable Travel and Physical Activity? J Transp Health 2018, 9, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tustin, D.H. Telecommuting Academics within an Open Distance Education Environment of South Africa: More Content, Productive, and Healthy? irrodl 2014, 15, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoda, M. Telework amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic: Effects on Work Style Reform in Japan. Corp Gov 2021, 21, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Peláez, A.; Erro-Garcés, A.; Pinilla García, F.J.; Kiriakou, D. Working in the 21st Century. The Coronavirus Crisis: A Driver of Digitalisation, Teleworking, and Innovation, with Unintended Social Consequences. Information 2021, 12, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Duck, J.; Jimmieson, N. E-Mail in the Workplace: The Role of Stress Appraisals and Normative Response Pressure in the Relationship between e-Mail Stressors and Employee Strain. Int J Stress Manag 2014, 21, 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waizenegger, L.; McKenna, B.; Cai, W.; Bendz, T. An Affordance Perspective of Team Collaboration and Enforced Working from Home during COVID-19. Eur J Inf Syst 2020, 29, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, J.A. From Classroom to Zoom Room: Exploring Instructor Modifications of Visual Nonverbal Behaviors in Synchronous Online Classrooms. Commun Teach 2022, 36, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesher Shoshan, H.; Wehrt, W. Understanding “Zoom Fatigue”: A Mixed-Method Approach. Appl Psychol 2022, 71, 827–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M.; Ingusci, E.; Signore, F.; Manuti, A.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Russo, V.; Zito, M.; Cortese, C.G. Wellbeing Costs of Technology Use during Covid-19 Remote Working: An Investigation Using the Italian Translation of the Technostress Creators Scale. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortbach, K.; Köffer, S.; Müller, C.P.F.; Niehaves, B. How IT Consumerization Affects the Stress Level at Work: A Public Sector Case Study. In Proceedings of the PACIS 2013 Proceedings; June 18 2013. 231.

- Tarafdar, M.; Cooper, C.L.; Stich, J.-F. The Technostress Trifecta - Techno Eustress, Techno Distress and Design: Theoretical Directions and an Agenda for Research. Inf Syst J 2019, 29, 6–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, G.; Esposito, A.; Sciarra, I.; Chiappetta, M. Definition, Symptoms and Risk of Techno-Stress: A Systematic Review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2019, 92, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braukmann, J.; Schmitt, A.; Ďuranová, L.; Ohly, S. Identifying ICT-Related Affective Events across Life Domains and Examining Their Unique Relationships with Employee Recovery. J Bus Psychol 2018, 33, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Kee, K.; Mao, C. Multitasking and Work-Life Balance: Explicating Multitasking When Working from Home. J Broadcast Electron Media 2021, 65, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.T.; Anwar, I.; Khan, N.A. Voluntary Part-Time and Mandatory Full-Time Telecommuting: A Comparative Longitudinal Analysis of the Impact of Managerial, Work and Individual Characteristics on Job Performance. Int J Manpow 2021, 43, 1316–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.K. Technological Appropriations as Workarounds: Integrating Electronic Health Records and Adaptive Structuration Theory Research. Inf Technol People 2018, 31, 368–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardeshmukh, S.R.; Sharma, D.; Golden, T.D. Impact of Telework on Exhaustion and Job Engagement: A Job Demands and Job Resources Model. New Technol Work Employ 2012, 27, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.T.; Anwar, I.; Khan, N.A.; Saleem, I. Work during COVID-19: Assessing the Influence of Job Demands and Resources on Practical and Psychological Outcomes for Employees. Asia-Pac J Bus Adm 2021, 13, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carlo, N.A.; Falco, A.; Capozza, D. Test di valutazione del rischio stress lavoro-correlato nella prospettiva del benessere organizzativo, Qu-Bo [Test for the assessment of work-related stress risk in the organizational well-being perspective, Qu-Bo]; FrancoAngeli: Milano, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Staufenbiel, S.M.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Spijker, A.T.; Elzinga, B.M.; Rossum, E.F.C. van Hair Cortisol, Stress Exposure, and Mental Health in Humans: A Systematic Review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 1220–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitham, J.C.; Bryant, J.L.; Miller, L.J. Beyond Glucocorticoids: Integrating Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) into Animal Welfare Research. Animals (Basel) 2020, 10, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimonis, E.R.; Fleming, G.E.; Wilbur, R.R.; Groer, M.W.; Granger, D.A. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and Its Ratio to Cortisol Moderate Associations between Maltreatment and Psychopathology in Male Juvenile Offenders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 101, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulter, N.; Kimonis, E.R.; Denson, T.F.; Begg, D.P. Female Primary and Secondary Psychopathic Variants Show Distinct Endocrine and Psychophysiological Profiles. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 104, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.C.; Carroll, D.; Gale, C.R.; Lord, J.M.; Arlt, W.; Batty, G.D. Cortisol, DHEA Sulphate, Their Ratio, and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality in the Vietnam Experience Study. Eur J Endocrinol 2010, 163, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, D.B.; Thayer, J.F.; Vedhara, K. Stress and Health: A Review of Psychobiological Processes. Annu Rev Psychol 2021, 72, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herr, R.M.; Almer, C.; Loerbroks, A.; Barrech, A.; Elfantel, I.; Siegrist, J.; Gündel, H.; Angerer, P.; Li, J. Associations of Work Stress with Hair Cortisol Concentrations – Initial Findings from a Prospective Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 89, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibar, C.; Fortuna, F.; Gonzalez, D.; Jamardo, J.; Jacobsen, D.; Pugliese, L.; Giraudo, L.; Ceres, V.; Mendoza, C.; Repetto, E.M.; et al. Evaluation of Stress, Burnout and Hair Cortisol Levels in Health Workers at a University Hospital during COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 128, 105213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stalder, T.; Kirschbaum, C. Analysis of Cortisol in Hair – State of the Art and Future Directions. Brain Behav Immun 2012, 26, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abell, J.G.; Stalder, T.; Ferrie, J.E.; Shipley, M.J.; Kirschbaum, C.; Kivimäki, M.; Kumari, M. Assessing Cortisol from Hair Samples in a Large Observational Cohort: The Whitehall II Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 73, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport, M.D.; Tiefenbacher, S.; Lutz, C.K.; Novak, M.A.; Meyer, J.S. Analysis of Endogenous Cortisol Concentrations in the Hair of Rhesus Macaques. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2006, 147, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comin, A.; Renaville, B.; Marchini, E.; Maiero, S.; Cairoli, F.; Prandi, A. Technical Note: Direct Enzyme Immunoassay of Progesterone in Bovine Milk Whey. J Dairy Sci 2005, 88, 4239–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, Evaluation, and Interpretation of Structural Equation Models. J Acad Mark Sc 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, US, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- de Lange, A.H.; Taris, T.W.; Kompier, M.A.J.; Houtman, I.L.D.; Bongers, P.M. “The Very Best of the Millennium”: Longitudinal Research and the Demand-Control-(Support) Model. J Occup Health Psychol 2003, 8, 282–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollberger, S.; Ehlert, U. How to Use and Interpret Hormone Ratios. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 63, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettenborn, L.; Tietze, A.; Kirschbaum, C.; Stalder, T. The Assessment of Cortisol in Human Hair: Associations with Sociodemographic Variables and Potential Confounders. Stress 2012, 15, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binz, T.M.; Rietschel, L.; Streit, F.; Hofmann, M.; Gehrke, J.; Herdener, M.; Quednow, B.B.; Martin, N.G.; Rietschel, M.; Kraemer, T.; et al. Endogenous Cortisol in Keratinized Matrices: Systematic Determination of Baseline Cortisol Levels in Hair and the Influence of Sex, Age and Hair Color. Forensic Sci Int 2018, 284, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalder, T.; Steudte-Schmiedgen, S.; Alexander, N.; Klucken, T.; Vater, A.; Wichmann, S.; Kirschbaum, C.; Miller, R. Stress-Related and Basic Determinants of Hair Cortisol in Humans: A Meta-Analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 77, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feller, S.; Vigl, M.; Bergmann, M.M.; Boeing, H.; Kirschbaum, C.; Stalder, T. Predictors of Hair Cortisol Concentrations in Older Adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 39, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2022.

- Finney, S.J.; DiStefano, C. Nonnormal and Categorical Data in Structural Equation Modeling. In Structural equation modeling: A second course, 2nd ed; Quantitative methods in education and the behavioral sciences: Issues, research, and teaching; IAP Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, US, 2013; pp. 439–492. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. Psychol Bull 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, R. Let Me Go to the Office! An Investigation into the Side Effects of Working from Home on Work-Life Balance. Int J Public Sector Manage 2020, 33, 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninaus, K.; Diehl, S.; Terlutter, R.; Chan, K.; Huang, A. Benefits and Stressors – Perceived Effects of ICT Use on Employee Health and Work Stress: An Exploratory Study from Austria and Hong Kong. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2015, 10, 28838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, R.; Flamini, G.; Gnan, L.; Pellegrini, M.M. Looking for Meanings at Work: Unraveling the Implications of Smart Working on Organizational Meaningfulness. Int J Org Anal. [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Wang, W.; Yu, S. Analysis of the Cognitive Load of Employees Working from Home and the Construction of the Telecommuting Experience Balance Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialho, J. Benefits and Challenges of Remote Work. In Digital Technologies and Transformation in Business, Industry and Organizations; Pereira, R., Bianchi, I., Rocha, Á., Eds.; Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-3-031-07626-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, N.S.; Axtell, C.; Raghuram, S.; Nurmi, N. Unpacking Virtual Work’s Dual Effects on Employee Well-Being: An Integrative Review and Future Research Agenda. J Manage 2022, 01492063221131535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazekami, S. Mechanisms to Improve Labor Productivity by Performing Telework. Telecomm Policy 2020, 44, 101868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, R.P.; Anderson, A.J.; Kaplan, S.A. A Within-Person Examination of the Effects of Telework. J Bus Psychol 2015, 30, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandola, T.; Booker, C.L.; Kumari, M.; Benzeval, M. Are Flexible Work Arrangements Associated with Lower Levels of Chronic Stress-Related Biomarkers? A Study of 6025 Employees in the UK Household Longitudinal Study. Sociology 2019, 53, 779–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, N.B.; Donzella, B.; Troy, M.F.; Barnes, A.J. Mother and Child Hair Cortisol during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Associations among Physiological Stress, Pandemic-Related Behaviors, and Child Emotional-Behavioral Health. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2022, 137, 105656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomas, T. Positive Work: A Multidimensional Overview and Analysis of Work-Related Drivers of Wellbeing. Int J Appl Posit Psychol 2019, 3, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, A.; Girardi, D.; Sarto, F.; Marcuzzo, G.; Vianello, L.; Magosso, D.; Dal Corso, L.; Bartolucci, G.B.; De Carlo, N.A. Una Nuova Scala Di Misura Degli Effetti Psico-Fisici Dello Stress Lavoro-Correlato in Una Prospettiva d’integrazione Di Metodi [A New Scale for Measuring the Psycho-Physical Effects of Work-Related Stress in a Perspective of Methods Integration]. Med Lav 2012, 103, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pariante, C.M.; Lightman, S.L. The HPA Axis in Major Depression: Classical Theories and New Developments. Trends Neurosci 2008, 31, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraut, B.; Touchette, É.; Gamble, H.; Royant-Parola, S.; Safar, M.E.; Varsat, B.; Léger, D. Short Sleep Duration and Increased Risk of Hypertension: A Primary Care Medicine Investigation. J Hypertens 2012, 30, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Cropley, M.; Griffith, J.; Kirschbaum, C. Job Strain and Anger Expression Predict Early Morning Elevations in Salivary Cortisol. Psychosom Med 2000, 62, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meij, L.; Gubbels, N.; Schaveling, J.; Almela, M.; van Vugt, M. Hair Cortisol and Work Stress: Importance of Workload and Stress Model (JDCS or ERI). Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 89, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.-S.; Lee, Y.-J.; Ahn, R.-S. Day-to-Day Differences in Cortisol Levels and Molar Cortisol-to-DHEA Ratios among Working Individuals. Yonsei Med J 2010, 51, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledford, A.K.; Dixon, D.; Luning, C.R.; Martin, B.J.; Miles, P.C.; Beckner, M.; Bennett, D.; Conley, J.; Nindl, B.C. Psychological and Physiological Predictors of Resilience in Navy SEAL Training. Behavioral Medicine 2020, 46, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, A.; Mase, J.; Howteerakul, N.; Rajatanun, T.; Suwannapong, N.; Yatsuya, H.; Ono, Y. The Effort-Reward Imbalance Work-Stress Model and Daytime Salivary Cortisol and Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) among Japanese Women. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutheil, F.; de Saint Vincent, S.; Pereira, B.; Schmidt, J.; Moustafa, F.; Charkhabi, M.; Bouillon-Minois, J.-B.; Clinchamps, M. DHEA as a Biomarker of Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.D.; Hickman, R.; Laudenslager, M.L. Hair Cortisol Analysis: A Promising Biomarker of HPA Activation in Older Adults. Gerontologist 2015, 55, S140–S145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaafsma, F.G.; Hulsegge, G.; de Jong, M.A.; Overvliet, J.; van Rossum, E.F.C.; Nieuwenhuijsen, K. The Potential of Using Hair Cortisol to Measure Chronic Stress in Occupational Healthcare; a Scoping Review. J Occup Health 2021, 63, e12189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penz, M.; Stalder, T.; Miller, R.; Ludwig, V.M.; Kanthak, M.K.; Kirschbaum, C. Hair Cortisol as a Biological Marker for Burnout Symptomatology. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 87, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penz, M.; Siegrist, J.; Wekenborg, M.K.; Rothe, N.; Walther, A.; Kirschbaum, C. Effort-Reward Imbalance at Work Is Associated with Hair Cortisol Concentrations: Prospective Evidence from the Dresden Burnout Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 109, 104399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendsche, J.; Ihle, A.; Wegge, J.; Penz, M.S.; Kirschbaum, C.; Kliegel, M. Prospective Associations between Burnout Symptomatology and Hair Cortisol. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2020, 93, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veldhoven, M.; Van den Broeck, A.; Daniels, K.; Bakker, A.B.; Tavares, S.M.; Ogbonnaya, C. Challenging the Universality of Job Resources: Why, When, and for Whom Are They Beneficial? Appl Psychol 2020, 69, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Turunen, J. The Relative Importance of Various Job Resources for Work Engagement: A Concurrent and Follow-up Dominance Analysis. BRQ Business Research Quarterly 2021, 23409444211012420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, G.; Taskin, L. Out of Sight, out of Mind in a New World of Work? Autonomy, Control, and Spatiotemporal Scaling in Telework. Organization Studies 2015, 36, 1507–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.D.; Veiga, J.F.; Dino, R.N. The Impact of Professional Isolation on Teleworker Job Performance and Turnover Intentions: Does Time Spent Teleworking, Interacting Face-to-Face, or Having Access to Communication-Enhancing Technology Matter? J Appl Psychol 2008, 93, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Väänänen, A.; Toivanen, M. The Challenge of Tied Autonomy for Traditional Work Stress Models. Work Stress 2018, 32, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, J.; Wanckel, C. Job Satisfaction and the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector: The Mediating Role of Job Autonomy. Rev Public Pers Adm 2023, 0734371X221148403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavković, M.; Sretenović, S.; Bugarčić, M. Remote Working for Sustainability of Organization during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediator-Moderator Role of Social Support. Sustainability 2022, 14, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, J.J.; Pierro, A.; Barbieri, B.; De Carlo, N.A.; Falco, A.; Kruglanski, A.W. One Size Doesn’t Fit All: The Influence of Supervisors’ Power Tactics and Subordinates’ Need for Cognitive Closure on Burnout and Stress. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 2016, 25, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, C.; Rimpiläinen, S.; Bosnic, I.; Thomas, J.; Savage, J. Emerging Trends in Digital Health and Care : A Refresh Post-COVID; Digital Health & Care Institute: Glasgow, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sano, Y.; Obata, A.; Atsumori, H.; Tanaka, T.; Ito, N.; Minusa, S.; Toyomura, T. QoL Improvement and Preventive Measures Utilizing Digital Biomarkers. Hitachi Review 2022, 71, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, F.; Baykal, E.; Abid, G. E-Leadership and Teleworking in Times of COVID-19 and beyond: What We Know and Where Do We Go. Front Psychol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, D.; van Duin, D.; Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Smartphone Use and Work–Home Interference: The Moderating Role of Social Norms and Employee Work Engagement. J Occup Organ Psychol 2015, 88, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, A.; Bohle, P.; Iskra-Golec, I.; Jansen, N.; Jay, S.; Rotenberg, L. Working Time Society Consensus Statements: Evidence-Based Effects of Shift Work and Non-Standard Working Hours on Workers, Family and Community. Ind Health 2019, 57, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortuna, F.; Rossi, L.; Elmo, G.C.; Arcese, G. Italians and Smart Working: A Technical Study on the Effects of Smart Working on the Society. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2023, 187, 122220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wingerden, J.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Fostering Employee Well-Being via a Job Crafting Intervention. J Vocat Behav 2017, 100, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and Validation of the Job Crafting Scale. J Vocat Behav 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, C.; Griffin, M.A. Optimal Time Lags in Panel Studies. Psychol Methods 2015, 20, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeijen, M.E.L.; Brenninkmeijer, V.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Mastenbroek, N.J.J.M. Exploring the Role of Personal Demands in the Health-Impairment Process of the Job Demands-Resources Model: A Study among Master Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girardi, D.; Falco, A.; Piccirelli, A.; Dal Corso, L.; Bortolato, S.; De Carlo, A. Perfectionism and Presenteeism among Managers of a Service Organization: The Mediating Role of Workaholism. TPM Test Psychom Methodol Appl Psychol. 2015, 22, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, D.; Falco, A.; De Carlo, A.; Dal Corso, L.; Benevene, P. Perfectionism and Workaholism in Managers: The Moderating Role of Workload. TPM Test Psychom Methodol Appl Psychol. 2018, 25, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moehring, K.; Weiland, A.; Reifenscheid, M.; Naumann, E.; Wenz, A.; Rettig, T.; Krieger, U.; Fikel, M.; Cornesse, C.; Blom, A.G. Inequality in Employment Trajectories and Their Socio-Economic Consequences during the Early Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany 2021.

| Predictors (Time 1) | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Intercept | −0.360 *** | 0.043 | −0.362 *** | 0.042 |

| Gender 1 | −0.133 † | 0.072 | −0.140 † | 0.072 |

| Age | 0.008 ** | 0.002 | 0.007 ** | 0.002 |

| Workload | 0.032 | 0.029 | −0.011 | 0.032 |

| Job autonomy | 0.009 | 0.021 | 0.008 | 0.023 |

| Smart working 2 | −0.177 ** | 0.067 | −0.202 ** | 0.066 |

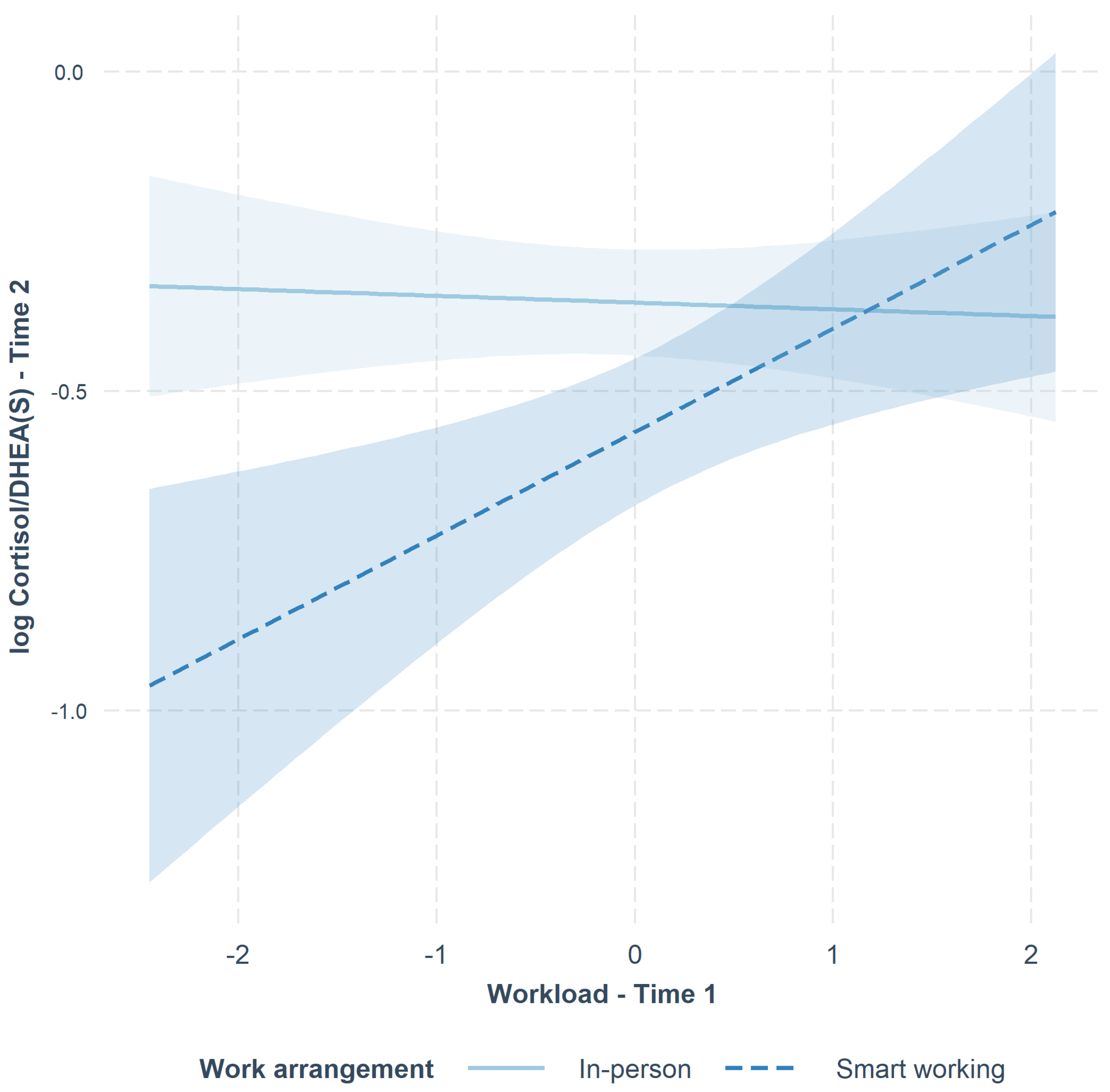

| Workload x smart working | 0.173 ** | 0.065 | ||

| Job autonomy x smart working | 0.031 | 0.048 | ||

| Simple slope workload (in-person) | −0.011 | 0.032 | ||

| Simple slope workload (smart working) | 0.162 ** | 0.056 | ||

| Total R2 | 0.186 *** | 0.238 *** | ||

| Change in R2 | 0.052 * | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).