Introduction

Independent and safe movement is essential for functional, social and activities of daily living. Mobility refers to changing body position or location or by transferring from one place to another and depends on an individual's body function, structures, gait, and balance capacities (World Health Organization, 2001). Gait is a complex activity that consists of motor and cognitive activities and relies on constant interaction between the central, peripheral and musculoskeletal systems (Oppewal & Hilgenkamp, 2019). Gait pattern is the result of the enhancing force, stability, shock absorption, and energy-saving. Therefore, any disturbance in the gait pattern can cause instability, pain and increased energy consumption (Oppewal et al., 2018).

Intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) is defined by significant limitations in both intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior, which is a collection of conceptual, social, and practical skills. These limitations appear before the age of 22 (Schalock, Luckasson, & Tassé, 2021). The classification for subdividing people with IDD into smaller groups should take into account (a) the intensity of support needs; (b) the extent of limitations in conceptual, social, and practical adaptive skills, and (c) the extent of limitations in intellectual functioning (Schalock et al., 2021).

Postural control is one of the motor abilities that affect motor control in which persons with IDD have significant challenges. This is because the central nervous system, which regulates motor and cognitive abilities, often shows some degree of delay in individuals with IDD (Reguera-García et al., 2021). In addition, individuals with IDD may have several functional disorders of balance (Bahiraei et al., 2018; Bahiraei, 2019), motor (Cleaver et al., 2009; Galli, Rigoldi, Mainardi, et al., 2008; Giagazoglou et al., 2013), and cognitive ability (Galli, Rigoldi, Mainardi, et al., 2008; Kachouri et al., 2020). Delays in motor and cognitive development affect the gait patterns of individuals with IDD because their efficiency and performance depend on the coordination between these systems (Lopes Pedralli & Schelle, 2013). Other factors that may affect gait patterns in these people are weakness in the muscles and joints of the lower extremities, obesity and use of multiple medications (Maas et al., 2020; Oppewal et al., 2018).

The functional limitations of individuals with IDD may be partial or total (Lin et al., 2013). As a result, the gait pattern may be observed with impaired sensory integrity and motor development. Shorter stride length, larger stride width, increased double support time, reduced lower limb joint mobility, joint kinetics, and biomechanical changes lead to adopting a "caution in stepping" strategy due to fear of falling (Almuhtaseb et al., 2014; Cioni et al., 2001; Oppewal et al., 2018; Oppewal & Hilgenkamp, 2019). Enkelaar et al. (2012) reported that limitations in the mobility of individuals with IDD are primarily due to the high prevalence of gait and balance difficulties (Enkelaar et al., 2012). Thus, people with IDD may have frequent falls that lead to injury (Pal et al., 2014). The main components of the gait impairment in these individuals are deficits in balance and postural control (Enkelaar et al., 2012). Therefore, optimization of gait is often a rehabilitation goal for individuals with IDD. Because a relationship between constraints on balance control and gait limitations in IDD has been determined, increased efficiency of postural control may be necessary to facilitate their functional performance.

It was observed that balance, gait, and strength training can increase joint loading and ultimately increase gait and stride length in people with Down syndrome (Elshemy, 2013). Gait speed depends on stride length and cadence. People with IDD tend to walk slower, as they must compensate for sensory impairments. In this way, the individual adopts simpler and slower functional movement strategies, thus compensating for cerebellar changes (Smith et al., 2010; Smith & Ulrich, 2008).

The complexity of controlling balance results in many different types of balance, gait, and falling problems that need systematic clinical assessment for effective intervention. Many clinical tests are designed to test a single “balance system”, but balance control is complex and involves many different underlying systems.

To address this problem, the Balance Evaluation Systems Test (BESTest) was developed as a balance evaluation test (Horak et al., 2009). This test can be used to identify and classify a broad range of postural control difficulties, and today, BESTest is considered one of the most comprehensive, feasible, simple, and cost-effective clinical balance assessments that can be performed. This test was designed in 2009 (Horak et al., 2009) and has been validated in several countries. Also, this test was validated in Iran (Bahiraei, 2019). The test assesses problems associated with balance function based on six factors: (1) biomechanical constraints; (2) stability limits/verticality; (3) anticipatory postural adjustments; (4) postural responses; (5) sensory orientation; and (6) gait stability. Each system is composed of neurophysiological components that regulate specific elements of postural control.

To direct specific types of treatments, therapists must be able to recognize the disordered system underlying the balance control in their clients (Horak et al., 2009). According to these items, in the design of exercise interventions, the postural control system should be examined purposefully according to the disrupted systems. Therefore, it is critical to have accurate information about these equilibrium systems (Sibley et al., 2015). Disturbance of one or a combination of two or more systems may lead to postural instability and an increased incidence of falls. Therefore, it is important to implement exercise programs based on the BESTest, to influence the different components and subsystems in charge of controlling the balance.

Different studies recommend that evaluation and training protocols for individuals with IDD should be based on the above-mentioned postural control factors (Bahiraei, 2019; Enkelaar et al., 2012; Horak et al., 2009). To improve the different gait parameters of people with IDD are of vital importance to implement specific education and exercise programs for this particular population. As indicated by Lee et al. (2014), (2016) it is possible to improve balance and gait parameters by implementing a balance exercise program. On the other hand, Ahmadi et al. (2020) indicated that lower extremity isokinetic peak torque, static balance, ankle and knee range of motion (ROM) and step length improved after participating in a functional strength training program for people with Down syndrome (Ahmadi et al., 2020).

To the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of studies examining the effect of exercise on gait patterns in young adults with IDD. Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the impact of postural exercises based on the BESTest program, including the six main sources that affect postural control on the gait kinematics of young adults with IDD. We hypothesized that the exercise program based on BESTest would lead to improvements in gait parameters in individuals with IDD.

Mthods

Study Design

The present study is a two-armed randomized controlled trial. The outcome variables were assessed at baseline, post-intervention (8 weeks), and one month after the end of the intervention. The training protocol was performed at the center where all the participants attended daily. The training group (TG) completed an 8-week program of selected postural exercises with three sessions a week (24 sessions in total). Each session lasted approximately 1 hour. All the items of the BESTest system were performed in each session, and all the systems were introduced in the training protocol. The characteristics of the intervention are listed in

Table 1. The participants of the control group (CG) continued their regular activities at the center.

Participants

Based on previous studies (Huri et al., 2015; Souza et al., 2021) and using an effect size of

d = 0.41, α < 0.05, power (1- β) = 0.80; we determined that at least 34 participants should be included in this study. Thirty-four males with mild IDD participated in the present study and were randomly divided into TG (n = 19) and CG (n = 19). After randomization, 4 participants included in the CG decided not to continue in the study (CG: n = 15).

Table 1 depicts the general characteristics of the participants.

All participants were recruited from one specific center for individuals with IDD (convenience sample). The intelligence quotient (IQ) of each participant was obtained by an expert using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale – IV. To verify that all participants had a mild IDD, a registered psychologist conducted psychological tests, which included the different domains of adaptive behavior, and an educational test (Blomqvist et al., 2012).

Inclusion criteria were: being diagnosed with mild IDD (IQ = 50-70 mean, and deficits in adaptive behaviors); young adults with IDD; being able to follow an exercise program and safety rules adopted in the study; willing to participate in regular training sessions; parent(s)/legal tutors and participants willing to provide written consent. Participants were excluded if they were participating in rehabilitation and/or occupational therapy activities that may interfere with the training program; participating in other exercise programs; vestibular and visual disorders that may influence the assessments; use of medications that may affect motor and/or cognitive functions; inability to provide written informed assent; or parents/legal tutors not willing to provide written informed consent; or suffered from neurological disorders; or musculoskeletal conditions that prevented them from walking without assistance.

This study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013) and was registered prospectively (trial registration number: IRCT20180203038603N1).

Procedures

Initially, all subjects were invited to two sessions over two days. The purpose of the first session was to familiarize the participants with the laboratory environment, introduce the tests, complete the informed consent forms by parents and measure anthropometric information such as height and weight, as well as the joint width of the knee and ankle of all subjects. Then in the second session, the subjects performed a gait test and kinematic data of a gait were collected using a three-dimensional motion capture system (Vicon, Los Angeles, CA, USA). The gait kinematics of the subjects were assessed by two trained raters. The raters were blinded as to which group the subjects belonged. The tests were performed at baseline, at the end of the program, and one month after the end of the program.

Postural Exercise Training

In this study, two special physical education specialists delivered the postural exercise training alternately. The training intervention was applied for 8 weeks at a frequency of 3 sessions per week for 1 hour. In this protocol, it was tried to design each training unit completely individually. As part of our training program, the overload principle was used. This principle was performed by increasing the intensity of the exercises or the number of repetitions and reducing the rest time between workouts.

The program was designed according to the basic 6 BESTest subsystems, including biomechanical constraints; stability limits/verticality; anticipatory postural adjustments; postural responses; sensory orientation; and gait stability. Each activity described in

Table 2 represents a variety of activities following the basic principles of the BESTest approach. Each intervention session consisted of 3 parts: the warm-up phase, the main part, and the cool-down phase. These exercises were designed for individuals with IDD according to their safety and applicability. All workout sessions were conducted in the afternoon (

Table 2).

Measurements

Kinematic gait parameters. All the subjects completed the gait analysis in the laboratory of XXXX University in XXXX. For this purpose, each participant performed a gait test in a 10-meter walk corridor in the laboratory, and the kinematic parameters during the test were recorded using a three-dimensional motion analysis system (Cortex v7.0, Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) and six Raptor-H cameras (Raptor-H, Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Rosa, CA, USA).

Before testing, the motion analysis system was calibrated following the manufacturer’s instructions (T-shaped and triangular tools with light-reflecting markers) for a space of 1.5 × 3 × 2 meters. This space was located in the middle of a 10-meter walk corridor in the laboratory. After preparing the testing essentials, a single researcher applied sixteen 25-mm-retro-reflective markers manually on both lower limbs using the plugin gait marker to set the model for kinematic measurements during gait tests (Lee et al., 2014; Rigoldi et al., 2012). Then, to define the Plug-In-Gait biomechanical model, each participant stood upright in the calibrated space and placed his upper limb in a 90-degree abduction position so that all markers were visible for about 2 seconds. Then, participants walked barefoot at their self-selected pace along the laboratory path. Thus, gait kinematic parameters were recorded from three planes (sagittal, frontal, and horizontal) and extracted gait kinematic parameters such as gait length (cm), step length (cm), gait speed (m/sec), gait pace (step/min), setting time (percentage of the gait cycle), swing time (percentage of the gait cycle), and dual support time (percentage of the gait cycle).

All data were extracted using Cortex software (Cortex v7.0, Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) and entered into an Excel spreadsheet. The test was repeated three times with a pause of one minute between each repetition. The average of three trials was used for the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were obtained for age, height, weight, BMI, and gait parameters. Continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations, and categorical variables were presented as percentages. Data were analyzed for normality (Shapiro-Wilk) and the presence of outliers (Box-plots).

Subsequently, a linear mixed-effect model was performed to analyze the effect of group (CG and TG) and time (pre, post, and follow-up) on gait parameters. Significant between-group differences at each level were examined using independent-sample t-tests, whereas within-group effects were examined using paired-sample t-tests. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d when possible. Effect sizes were classified as small (d ≤ 0.49), medium (d ≥ 0.50; d ≤ 0.79), and large (d ≥ 0.80) (Rosenthal, 1996). The significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05. Statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS, v 21.0, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Table 1 depicts the descriptive characteristics of the participants. Both groups had similar age, height, weight, BMI and IQ (all

p < 0.050).

Gait Parameters

At baseline, there were no between-group differences in the parameters of gait kinematics (all p > 0.050).

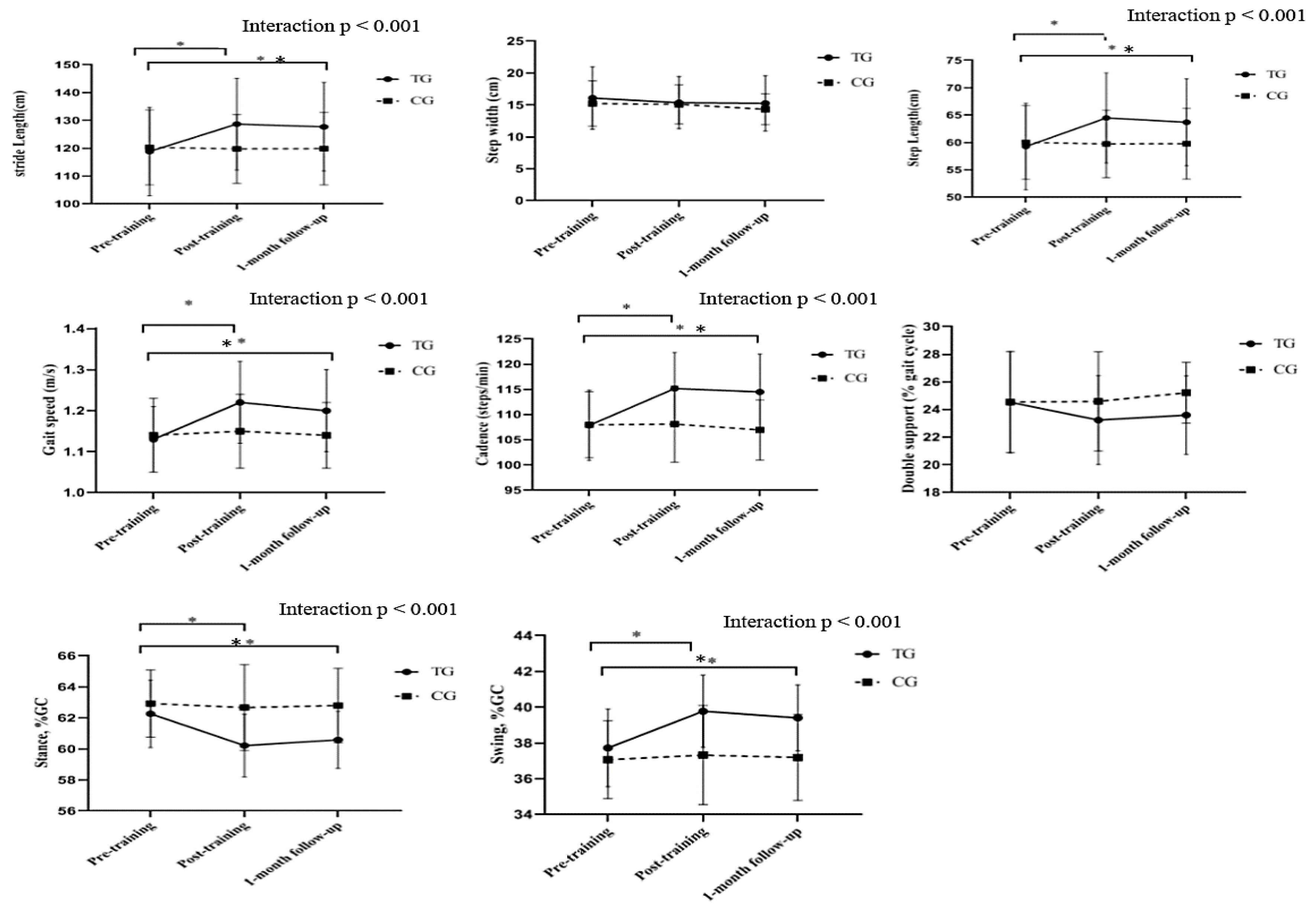

There were significant group × time interactions for step and stride length (F [2, 32] = 39.41; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.55), cadence (F [2, 32] = 28.83; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.47), gait speed (F [2, 32] = 13.11, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.30) and stance and swing (F [2, 32] = 7.66; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.19). Nevertheless, there was no significant group × time interaction for step width and double support (p > 0.050).

The post-hoc analysis revealed that the TG significantly improved step length at pre–post training (t = -4.85; p < 0.001; d = 0.61), and pre−follow-up (t = -4.41; P < 0.001; d = 0.56).

The TG significantly improved the stride length at pre–post training (t = -4.85; p < 0.001; d = 0.61), and pre−follow-up (t = -4.41; p < 0.001; d = 0.56). However, no significant differences were observed in step length and stride length at post training vs follow-up period (t = 0.94; p = 0.35).

The TG significantly improved the cadence at pre–post training (t = -5.2.; p < 0.001; d = 1.03), pre−follow-up (t = -3.85; p < 0.001; d = 0.91). However, no significant changes were observed between the post training vs follow-up values (t = 1.43; p = 0.43; d = 0.08).

The TG also improved the gait speed at pre–post training (t = -5.52; p < 0.001; d = 0.99), and pre-follow-up (t = -3.41; p < 0.002; d = 0.77), but there were no significant changes at post training vs follow-up period (t = 1.69; p = 0.10).

The TG group significantly increased the stance at pre–post training (t = 4.14; p < 0.001; d = 0.98), pre−follow-up (t = 3.45; p < 0.002; d = 0.83), but no significant changes were observed at post training vs follow-up period (t = -1.3; p = 0.20).

The TG group significantly increased the swing at pre–post training (

t = -4.14;

p < 0.001;

d = 0.98), pre−follow-up (

t = -3.45; p < 0.002;

d = 0.83), however no significant changes were observed between the post training vs follow-up values (

t = 1.3;

p = 0.20). It is noteworthy that the CG was not significantly different in any parameter evaluated between the pre- and post or follow up tests (

Table 3) (

Figure 1).

Discussion

This study was conducted to analyze the effects of the BESTest exercise program on kinematic gait parameters in individuals with IDD. The results showed that 8 weeks of selected exercises led to a significant improvement in gait kinematics parameters, such as step length, stride length, cadence, and speed of gait, stance, and swing. Few studies have examined the effects of exercise programs on gait kinematics parameters in subjects with IDD. Lee et al. (2014) examined the effects of an 8-week balance program on the gait kinematics of people with IDD. The results showed that balance training programs lead to significant improvements in participants' performance in spatiotemporal gait parameters (Lee et al., 2014).

Lee et al. (2016), in another study on the effects of 8 weeks of a balance training program on balance, gait, and muscle strength of adolescents with IDD, with an average age of 14-19 years, reported that balance training did not significantly improve the 10-meter gait test, which is not consistent with the present study. Possible reasons include the type of exercise program, the age range of the subjects, and the method of measuring the gait variable or a different exercise protocol (Lee et al., 2016).

Rodenbusch et al. (2013) examined the effect of treadmill inclination exercises on individuals aged 5–11 years with Down syndrome. The results showed that in individuals with Down syndrome, changes in spatiotemporal gait parameters and angular variables are created in the stance phase and plantar flexion reduction before swing (Rodenbusch et al., 2013). Another study by Vinagre et al. (2016) examined the effect of 10 weeks of Bobath physiotherapy training in individuals with Down syndrome with a mean age of 28 years. They found speed, cadence, step length, stride length, and step width improvements. They also found improvements in stepping angle correction and symmetry (Vinagre et al., 2016). Another study showed that treadmill training could improve gait patterns and increase step and stride length in infants with Down syndrome (Ulrich et al., 2001).

Carmeli et al. (2002) examined the effect of 6 months of treadmill training on IDD, and after training, gait and balance also improved significantly (Carmeli et al., 2002). Kubilay et al. (2011) performed 8 weeks of balance training with a Swiss ball in adolescents with IDD. The results showed a significant improvement in all parameters in the training group (Hartman et al., 2010; Kubilay et al., 2011). Hou TS (2008) examined the effects of 8 weeks of low-intensity jogging and walking exercises in adolescents with IDD and found significant improvements in gait speed (TS, 2008).

Previous studies have reported that age, gait ability, and dynamic balance decrease more in people with IDD than in neurotypical people (Giagazoglou et al., 2013; Kubilay et al., 2011; Nam et al., 2016). These studies showed reductions in all gait spatiotemporal parameters and a reduced hip range of motion, affecting step length. In addition, it was observed that the increase in the double support time and step width leads to greater instability in individuals with IDD (Lee et al., 2016).

The TG in our study was likely to have improved flexibility and muscle strength and reduced the fear of falling by increasing self-confidence. Improving these parameters may lead to improve gait kinematic parameters in individuals with IDD (Shashidhara, 2018).

For example, the exercise of crossing obstacles leads to an improvement in the stride length and range of motion of the joints. Also, walking on the mattress facilitates and integrates the visual and atrial inputs for balance and gait (Berg et al., 1991). In addition, balance, gait, and strength training can also increase joint loading and ultimately increase gait and stride length in people with motor disabilities (Elshemy, 2013).

Individuals with IDD present an increase in asymmetric movements, especially in their torso and head, which reduces push-off motions and reduces gait speed (Lipfert et al., 2014). Gait functions are one of the most essential requirements for independent activities of daily living, so gait speed is an essential indicator of disability in gait (Almuhtaseb et al., 2014). On the other hand, reducing the gait speed provides more time for an appropriate response and more balance (Rosen, 1997). In another study by Lee et al. (2014), the balance training program improved gait speed in the experimental group by 31% (Lee et al., 2014).

Angulo-Barroso et al. (2008) showed that speed gait increased after treadmill training in individuals with IDD (Angulo-Barroso et al., 2008). Because Verghese et al. (2009) reported that a reduction in speed of 10 cm/s was equivalent to a loss of 10% mobility in daily life, compared with those in the experimental group, they showed a 30% improvement in gait speed and increased independence in daily life (Verghese et al., 2009). Additionally, to increase the gait speed through cadence, you have to increase the number of steps per minute, which requires more dynamic balance. Therefore, in the training group, better dynamic balance and better cadence led to increased gait speed (Behm et al., 2002; Nam et al., 2016). Therefore, it can be said that the increase in gait speed is due to the increase in cadence, step and stride length (Ardestani et al., 2016).

According to different studies, other causes of increased gait speed following a training program are reduction of double support and increased ankle joint mobility, which is usually reduced in people with IDD (Galli, Rigoldi, Brunner, et al., 2008). In other words, increasing the double support phase leads to a decrease in speed and instability in the gait, so performing balance training and reducing the time of double support indicates an increase in gait stability.

On the other hand, the increased swing phase has a significant effect on the individual's capacity to maintain a correct posture and facilitate walking (Lee et al., 2014). In the present study, a significant increase in swing time was observed, which led to an increase in cycle time. As mentioned before, increased swing time significantly affects the individual's capacity to maintain an integrated posture and facilitate gait (Rodenbusch et al., 2013). In general, improving one's adaptation to everyday obstacles reinforces the idea that selected exercises are a valuable program for people with IDD.

In justifying the durability of the observed training effects, we can refer to the results of Llorens-Martin et al. (2010), who showed that 7 weeks of voluntary physical training has a significant effect on increasing the process of neuron production in the hippocampus. This effect might cause improvements in the learning process in our participants because the hippocampus is responsible for motor memory in humans and the volume of this part of the brain is directly related to learning and motor memory (Long et al., 2018). Increasing the number of cells in this part of the brain indicates the improvement of neural processes that perform motor skills (Llorens-Martin et al., 2010). According to this theory, differences in motor performance between neurologically impaired individuals and the general population are due to the motor control system functioning sub-optimally. The exercise program implemented in our study was probably able to increase the intensity of stimuli that activate motor neurons, producing greater force and thus providing movement patterns comparable to those observed in individuals without disabilities (Ahmadi et al., 2020; Novak & Morgan, 2019).

In the present study, the possible effects of movement on the functioning of the neuromuscular system might be attributed to the fact that motor training leads to changes in the transcription process of several known genes associated with neuronal activity, synaptic structure, and the production of neurotransmitters (Long et al., 2018). Exercise may produce adaptations in the hippocampus, which plays an essential role in learning and memory. In this regard, research has shown that physical activity can affect neuroprotective processes, brain flexibility and positively affect cognition and behavior (Tong et al., 2001).

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, our results for people with mild IDD may not be generalized to people with moderate and severe IDD. Furthermore, as we use a convenience sample, our findings should be treated with caution. Second, in our study we were unable to analyze the balance and risks of falls or injuries of the participants. Third, the duration of the program was only 8 weeks and the follow-up was carried out only one month after the end of the study. Therefore, we believe that it is necessary to carry out future studies of longer duration and to perform follow-ups at 6 or 12 months after the end of the programs to determine if the changes are maintained over time. Finally, we did not assess the physical activity levels nor the sedentary levels of the participants. These variables could have some effects on the gait-related parameters of the participants. Nevertheless, as all of them were from the same center, their levels of physical activity or sedentarism may be similar.

Implications and Suggestions for Future Research

As suggested by JudgeRoy et al. (1996), improvements in gait patterns can be due to the increase in the strength of the muscles of the lower extremities (JudgeRoy et al., 1996). Therefore, future studies should not only evaluate gait kinematic parameters but also muscular strength parameters. In addition, future research could also implement strength training and balance training at the same time.

Further research is needed to analyze gait and kinematics parameters in persons with moderate, severe and profound IDD, as well as exercise programs to improve these parameters. Finally, a more prolonged study with a longer follow-up would be necessary to understand better the effect of the BESTest-based postural exercise program on balance and the risks of falls or injuries in people with IDD.

There are basic and specific principles that rehabilitation specialists can use to recommend and implement exercises for young adults with IDD to maintain and enhance their balance and gait kinematics. The exercise program implemented in our study can be easily adopted in clinical practice and in centers for people with IDD. The implementation of the BESTest program will help improve the gait performance of people with IDD and could help reduce the risk of falls and injuries in this population.

Conclusions

The individuals with IDD who participated in an eight-week BESTest-based postural exercise program improved various gait-related parameters and decreased gait pattern abnormalities. The improvements obtained in our study may help prevent long-term complications, reduce the risk of falls, increase physical performance, and facilitate participation in activities of daily living. In order to improve gait patterns, personal independence and enhance the quality of life of individuals with IDD, we believe that educators, parents, physiotherapists, healthcare providers, and centers for people with IDD could adopt the exercise program applied in the present study.

Submission deceleration

The manuscript has been read and approved by co-authors, has not been previously published, and will not be submitted to any other journal during the decision process. If accepted for publication be the Disability and Health Journal and it will not be published in any other journal.

Acknowledgment

We thank Guilan Intellectual Disabilities Association, especially the parents and individuals with ID who participated in this study, for their commitment to all scheduled evaluations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by authors.

Funding source

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not for profit sectors.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects’ parents/guardians and a verbal accent was provided by the subjects involved in the study.

References

- Ahmadi, N., Peyk, F., Hovanloo, F., & Hemati Garekani, S. (2020). Effect of functional strength training on gait kinematics, muscle strength and static balance of young adults with Down syndrome. International Journal of Motor Control and Learning 2, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Almuhtaseb, S., Oppewal, A., & Hilgenkamp, T. I. (2014). Gait characteristics in individuals with intellectual disabilities: A literature review. Research in developmental disabilities 35, 2858–2883. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angulo-Barroso, R. M., Wu, J., & Ulrich, D. A. (2008). Long-term effect of different treadmill interventions on gait development in new walkers with Down syndrome. Gait & posture 27, 231–238. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardestani, M. M., Ferrigno, C., Moazen, M., & Wimmer, M. A. (2016). From normal to fast walking: impact of cadence and stride length on lower extremity joint moments. Gait & posture 46, 118–125. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahiraei, S., Daneshmandi, H., Norasteh, A. A., & Sokhangoei, Y. (2018). The Study of Biomechanical Gait Cycle and Balance Characteristics in Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Physical Treatments - Specific Physical Therapy 8, 63–76. [CrossRef]

- Bahiraei, S., Daneshmandi, H., Norasteh, A.A., Yahya, S. (2019). Balance stability in intellectual disability: Introductory evidence for the balance evaluation systems test (BESTest). Life Span and Disability 22, 7–28.

- Behm, D. G., Anderson, K., & Curnew, R. S. (2002). Muscle force and activation under stable and unstable conditions. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 16, 416–422.

- Berg, K. O., Wood-Dauphinee, S. L., Williams, J. I., & Maki, B. (1991). Measuring balance in the elderly: validation of an instrument. Canadian journal of public health 39, 7–11.

- Blomqvist, S., Wester, A., Sundelin, G., & Rehn, B. (2012). Test–retest reliability, smallest real difference and concurrent validity of six different balance tests on young people with mild to moderate intellectual disability. Physiotherapy 98, 313–319. [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, E., Kessel, S., Coleman, R., & Ayalon, M. (2002). Effects of a treadmill walking program on muscle strength and balance in elderly people with Down syndrome. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 57, M106–M110. [CrossRef]

- Cioni, M., Cocilovo, A., Rossi, F., Paci, D., & Valle, M. S. (2001). Analysis of ankle kinetics during walking in individuals with Down syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation 106, 470–478. [CrossRef]

- Cleaver, S., Hunter, D., & Ouellette-Kuntz, H. (2009). Physical mobility limitations in adults with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 53, 93–105. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshemy, S. A. (2013). Comparative study: Parameters of gait in Down syndrome versus matched obese and healthy children. Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics 14, 285–291. [CrossRef]

- Enkelaar, L., Smulders, E., van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk, H., Geurts, A. C., & Weerdesteyn, V. (2012). A review of balance and gait capacities in relation to falls in persons with intellectual disability. Research in developmental disabilities 33, 291–306. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, M., Rigoldi, C., Brunner, R., Virji-Babul, N., & Giorgio, A. (2008). Joint stiffness and gait pattern evaluation in children with Down syndrome. Gait & posture 28, 502–506. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, M., Rigoldi, C., Mainardi, L., Tenore, N., Onorati, P., & Albertini, G. (2008). Postural control in patients with Down syndrome. Disability and rehabilitation 30, 1274–1278. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giagazoglou, P., Kokaridas, D., Sidiropoulou, M., Patsiaouras, A., Karra, C., & Neofotistou, K. (2013). Effects of a trampoline exercise intervention on motor performance and balance ability of children with intellectual disabilities. Research in developmental disabilities 34, 2701–2707. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, E., Houwen, S., Scherder, E., & Visscher, C. (2010). On the relationship between motor performance and executive functioning in children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 54, 468–477. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horak, F. B., Wrisley, D. M., & Frank, J. (2009). The balance evaluation systems test (BESTest) to differentiate balance deficits. Physical therapy 89(5), 484–498. [CrossRef]

- Huri, M., Huri, E., Kayihan, H., & Altuntas, O. (2015). Effects of occupational therapy on quality of life of patients with metastatic prostate cancer: a randomized controlled study. Saudi medical journal 36, 954. [CrossRef]

- JudgeRoy, J. O., Davis III, B., & Õunpuu, S. (1996). Step length reductions in advanced age: the role of ankle and hip kinetics. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 51, M303–M312. [CrossRef]

- Kachouri, H., Laatar, R., Borji, R., Rebai, H., & Sahli, S. (2020). Using a dual-task paradigm to investigate motor and cognitive performance in children with intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 33, 172–179. [CrossRef]

- Kubilay, N. S., Yildirim, Y., Kara, B., & Harutoglu-Akdur, H. (2011). Effect of balance training and posture exercises on functional level in mental retardation. Fizyoterapi Rehabilitasyon 22(2), 55–64.

- Lee, K., Lee, M., & Song, C. (2016). Balance training improves postural balance, gait, and functional strength in adolescents with intellectual disabilities: Single-blinded, randomized clinical trial. Disability and health journal 9, 416–422. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. J., Lee, M. M., Shin, D. C., Shin, S. H., & Song, C. H. (2014). The effects of a balance exercise program for enhancement of gait function on temporal and spatial gait parameters in young people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of physical therapy science 26(4), 513–516. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-P., Hsia, Y.-C., Hsu, S.-W., Loh, C.-H., Wu, C.-L., & Lin, J.-D. (2013). Caregivers’ reported functional limitations in activities of daily living among middle-aged adults with intellectual disabilities. Research in developmental disabilities 34, 4559–4564. [CrossRef]

- Lipfert, S. W., Günther, M., Renjewski, D., & Seyfarth, A. (2014). Impulsive ankle push-off powers leg swing in human walking. Journal of experimental biology 217, 1218–1228. [CrossRef]

- Llorens-Martin, M., Rueda, N., Tejeda, G. S., Flórez, J., Trejo, J. L., & Martínez-Cué, C. (2010). Effects of voluntary physical exercise on adult hippocampal neurogenesis and behavior of Ts65Dn mice, a model of Down syndrome. Neuroscience 171(4), 1228–1240. [CrossRef]

- Long, J., Feng, Y., Liao, H., Zhou, Q., & Urbin, M. (2018). Motor sequence learning is associated with hippocampal subfield volume in humans with medial temporal lobe epilepsy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 12, 367. [CrossRef]

- Lopes Pedralli, M., & Schelle, G. H. (2013). Gait evaluation in individuals with Down syndrome. Brazilian Journal of Biomotricity 7(1), 21–27.

- Maas, S., Festen, D., Hilgenkamp, T. I., & Oppewal, A. (2020). The association between medication use and gait in adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 64, 793–803. [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.-C., Cha, H.-G., & Kim, M.-K. (2016). The effects of exercising on an unstable surface on the gait and balance ability of normal adults. Journal of physical therapy science 28(7), 2102–2104. [CrossRef]

- Novak, I., & Morgan, C. (2019). High-risk follow-up: early intervention and rehabilitation. Handbook of clinical neurology 162, 483–510. [CrossRef]

- Oppewal, A., Festen, D. A., & Hilgenkamp, T. I. (2018). Gait characteristics of adults with intellectual disability. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities 123(3), 283–299. [CrossRef]

- Oppewal, A., & Hilgenkamp, T. I. (2019). The dual task effect on gait in adults with intellectual disabilities: is it predictive for falls? Disability and rehabilitation 41, 26–32. [CrossRef]

- Pal, J. Pal, J., Hale, L., Mirfin-Veitch, B., & Claydon, L. (2014). Injuries and falls among adults with intellectual disability: A prospective New Zealand cohort study. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 39(1), 35–44. [CrossRef]

- Reguera-García, M. M., Leirós-Rodríguez, R., Fernández-Baro, E., & Álvarez-Barrio, L. (2021). Reliability and Validity of the Six Spot Step Test in People with Intellectual Disability. Brain Sciences 11, 201. [CrossRef]

- Rigoldi, C., Galli, M., & Albertini, G. (2011). Gait development during lifespan in subjects with Down syndrome. Research in developmental disabilities 32(1), 158–163. [CrossRef]

- Rigoldi, C., Galli, M., Cimolin, V., Camerota, F., Celletti, C., Tenore, N., & Albertini, G. (2012). Gait strategy in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome hypermobility type and Down syndrome. Research in developmental disabilities 33, 1437–1442. [CrossRef]

- Rodenbusch, T. L., Ribeiro, T. S., Simão, C. R., Britto, H. M., Tudella, E., & Lindquist, A. R. (2013). Effects of treadmill inclination on the gait of children with Down syndrome. Research in developmental disabilities 34(7), 2185–2190. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, S. (1997). Kinesiology and sensorimotor function. Foundations of orientation and mobility 170–199.

- Rosenthal, J. A. (1996). Qualitative descriptors of strength of association and effect size. Journal of social service Research, 21, 37–59. [CrossRef]

- Schalock, R. L., Luckasson, R., & Tassé, M. J. Intellectual Disability: Definition, Classification, and Systems of Supports. AAIDD, 12th ed.; American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: Washington, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shashidhara, M. (2018). The effect of eight-week yoga exercise on balance and gait in girls with intellectual disability. International Journal of Yoga and Allied Sciences 7, 31–35.

- Sibley, K. M., Beauchamp, M. K., Van Ooteghem, K., Straus, S. E., & Jaglal, S. B. (2015). Using the systems framework for postural control to analyze the components of balance evaluated in standardized balance measures: a scoping review. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 96, 122–132.e129. [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. A., Ashton-Miller, J. A., & Ulrich, B. D. (2010). Gait adaptations in response to perturbations in adults with Down syndrome. Gait & posture 32, 149–154. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B. A., & Ulrich, B. D. (2008). Early onset of stabilizing strategies for gait and obstacles: older adults with Down syndrome. Gait & posture 28, 448–455. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, A. P. S. d., Silva, L. C. d., & Fayh, A. P. T. (2021). Nutritional Intervention Contributes to the Improvement of Symptoms Related to Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients 13, 589. [CrossRef]

- Tong, L., Shen, H., Perreau, V. M., Balazs, R., & Cotman, C. W. (2001). Effects of exercise on gene-expression profile in the rat hippocampus. Neurobiology of disease 8, 1046–1056. [CrossRef]

- TS, H. (2008). The effects of run/walk exercise on physical fitness and sport skills on individuals with mental retardation. NCYU Phys Educ Health Recreat J 7, 44–58.

- Ulrich, D. A., Ulrich, B. D., Angulo-Kinzler, R. M., & Yun, J. (2001). Treadmill training of infants with Down syndrome: evidence-based developmental outcomes. Pediatrics 108, e84. [CrossRef]

- Verghese, J., Holtzer, R., Lipton, R. B., & Wang, C. (2009). Quantitative gait markers and incident fall risk in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 64, 896–901. [CrossRef]

- Vinagre, I. N., Cámara, M. B., & Gadella, J. B. (2016). Gait analysis and Bobath physiotherapy in adults with Down syndrome. International Medical Review on Down Syndrome 20(1), 8–14. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF, Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- World Medical Association. (2013). World medical association declaration of Helsinki. JAMA 310(20), 2191–2194. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).