Submitted:

03 March 2023

Posted:

06 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Clinical data and Characterization of extracellular vesicle

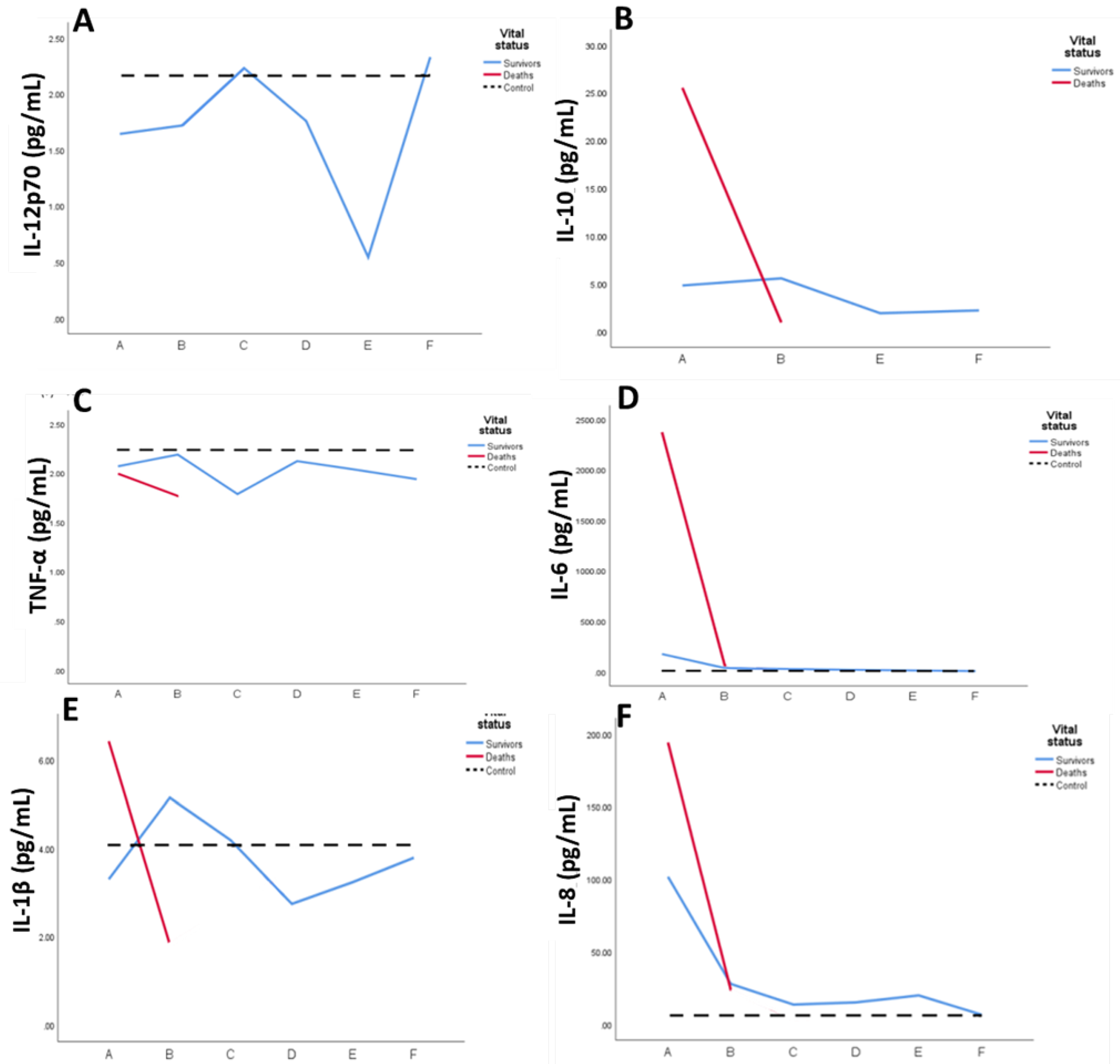

2.2. Systemic Inflammatory mediators

2.3. Functional-enrichment analysis for Gene Ontology terms

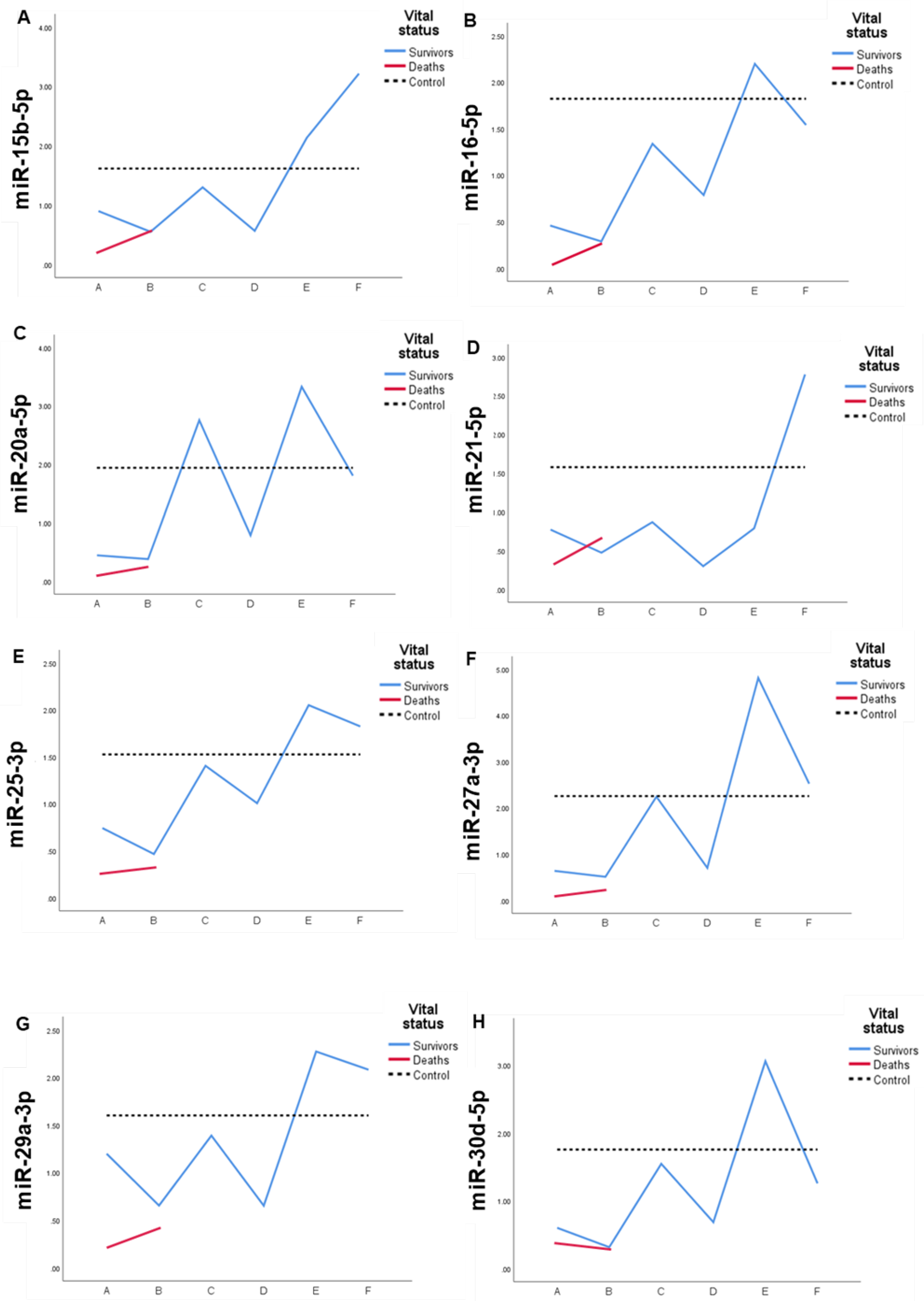

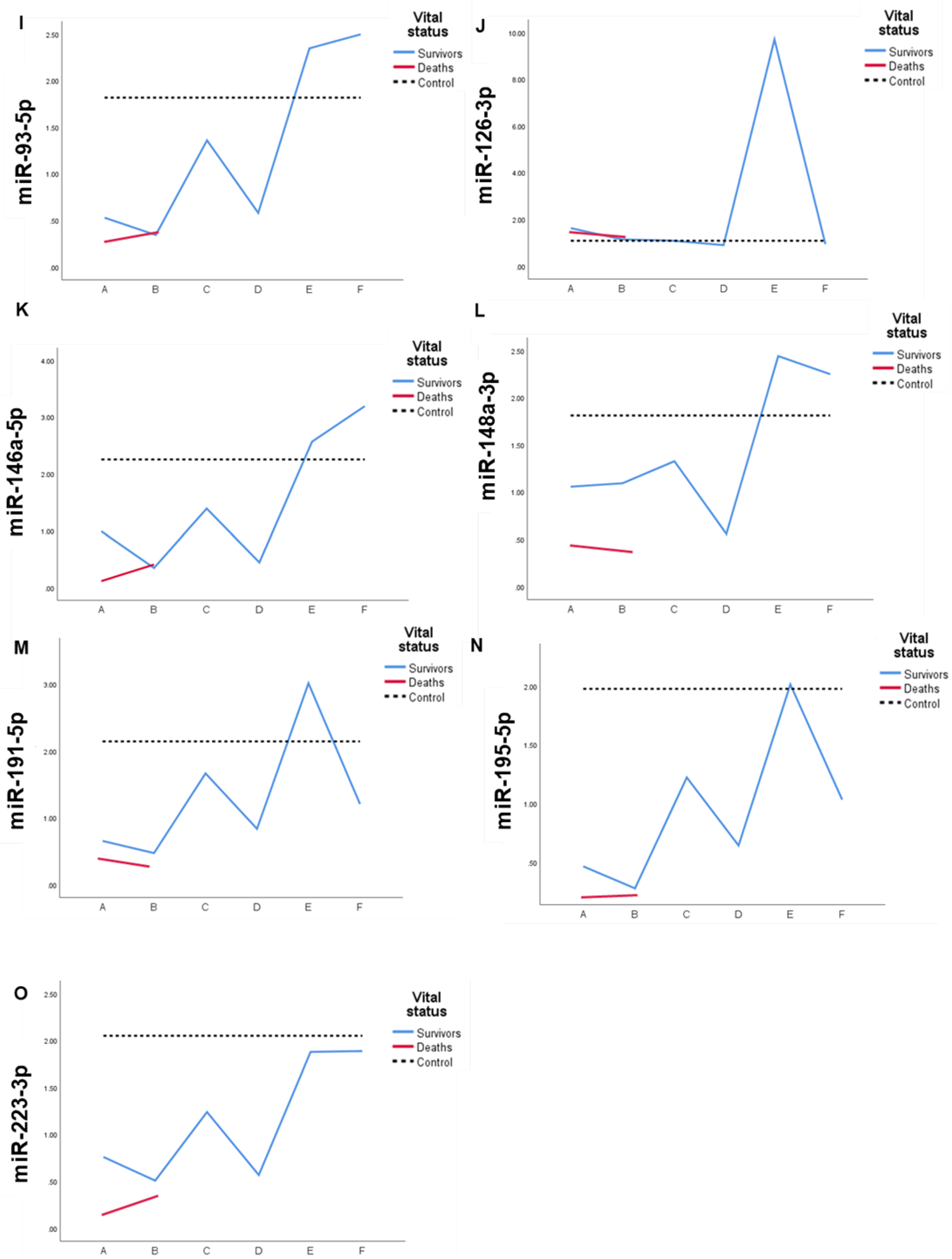

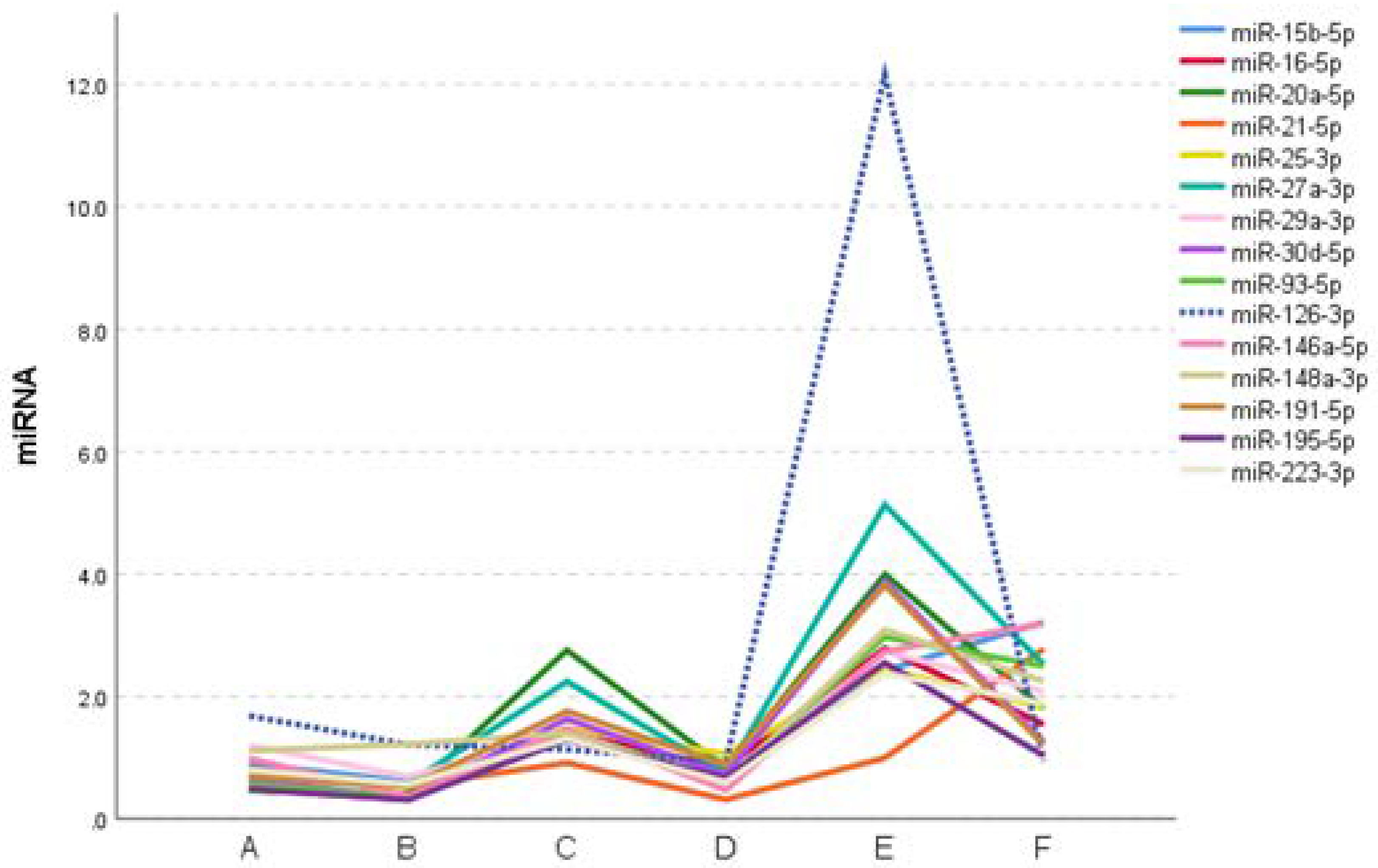

2.4. Expression profile of DEmiRs in septic patients

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Patient selection

3.2. Blood collection and plasma separation

3.3. Evaluation of inflammatory cytokines and serum C-reactive proteins levels

3.4. Plasmatic extracellular vesicle isolation

3.5. Proteomic analysis by mass spectrometry and data processing

3.6. Plasmatic extracellular vesicles miRNA determination

3.7. Statistics

4. Conclusions

5. Declarations

5.1. Ethics approval and consent to participate

5.2. Limitations of the study

5.3. Data availability statements

5.4. Competing interests

5.5. Authors' contributions

5.6. Funding

5.7. Acknowledgements

Supplementary Materials

References

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C. S.; Seymour, C. W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G. R.; Chiche, J.-D.; Coopersmith, C. M., The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). Jama 2016, 315, (8), 801-810.

- Organization, W. H., Global report on the epidemiology and burden of sepsis: current evidence, identifying gaps and future directions. 2020.

- Rudd, K. E.; Johnson, S. C.; Agesa, K. M.; Shackelford, K. A.; Tsoi, D.; Kievlan, D. R.; Colombara, D. V.; Ikuta, K. S.; Kissoon, N.; Finfer, S., Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet 2020, 395, (10219), 200-211.

- Cecconi, M.; Evans, L.; Levy, M.; Rhodes, A., Sepsis and septic shock. The Lancet 2018, 392, (10141), 75-87.

- Iwashyna, T. J.; Cooke, C. R.; Wunsch, H.; Kahn, J. M., Population burden of long-term survivorship after severe sepsis in older Americans. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2012, 60, (6), 1070-1077.

- Quartin, A. A.; Schein, R. M.; Kett, D. H.; Peduzzi, P. N., Magnitude and duration of the effect of sepsis on survival. Jama 1997, 277, (13), 1058-1063.

- Wang, H. E.; Szychowski, J. M.; Griffin, R.; Safford, M. M.; Shapiro, N. I.; Howard, G., Long-term mortality after community-acquired sepsis: a longitudinal population-based cohort study. BMJ open 2014, 4, (1).

- Mostel, Z.; Perl, A.; Marck, M.; Mehdi, S. F.; Lowell, B.; Bathija, S.; Santosh, R.; Pavlov, V. A.; Chavan, S. S.; Roth, J., Post-sepsis syndrome–an evolving entity that afflicts survivors of sepsis. Molecular Medicine 2020, 26, (1), 1-14.

- Batista Lorigados, C.; Garcia Soriano, F.; Szabo, C., Pathomechanisms of myocardial dysfunction in sepsis. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-Immune, Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders) 2010, 10, (3), 274-284.

- van der Slikke, E. C.; An, A. Y.; Hancock, R. E.; Bouma, H. R., Exploring the pathophysiology of post-sepsis syndrome to identify therapeutic opportunities. EBioMedicine 2020, 61, 103044.

- Angus, D. C.; Linde-Zwirble, W. T.; Lidicker, J.; Clermont, G.; Carcillo, J.; Pinsky, M. R., Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Read Online: Critical Care Medicine| Society of Critical Care Medicine 2001, 29, (7), 1303-1310.

- Prescott, H. C.; Langa, K. M.; Liu, V.; Escobar, G. J.; Iwashyna, T. J., Increased 1-year healthcare use in survivors of severe sepsis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2014, 190, (1), 62-69.

- Delano, M. J.; Ward, P. A., The immune system's role in sepsis progression, resolution, and long-term outcome. Immunological reviews 2016, 274, (1), 330-353.

- Gritte, R. B.; Souza-Siqueira, T.; Curi, R.; Machado, M. C. C.; Soriano, F. G., Why Septic Patients Remain Sick After Hospital Discharge? Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 11, 3873.

- Reithmair, M.; Buschmann, D.; Märte, M.; Kirchner, B.; Hagl, D.; Kaufmann, I.; Pfob, M.; Chouker, A.; Steinlein, O. K.; Pfaffl, M. W., Cellular and extracellular mi RNA s are blood-compartment-specific diagnostic targets in sepsis. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2017, 21, (10), 2403-2411.

- Raeven, P.; Zipperle, J.; Drechsler, S., Extracellular vesicles as markers and mediators in sepsis. Theranostics 2018, 8, (12), 3348.

- Chaput, N.; Théry, C. In Exosomes: immune properties and potential clinical implementations, Seminars in immunopathology, 2011; Springer: 2011; pp 419-440.

- D’Souza-Schorey, C.; Schorey, J. S., Regulation and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle biogenesis and secretion. Essays in biochemistry 2018, 62, (2), 125-133.

- Yáñez-Mó, M.; Siljander, P. R.-M.; Andreu, Z.; Bedina Zavec, A.; Borràs, F. E.; Buzas, E. I.; Buzas, K.; Casal, E.; Cappello, F.; Carvalho, J., Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. Journal of extracellular vesicles 2015, 4, (1), 27066.

- Doyle, L. M.; Wang, M. Z., Overview of extracellular vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells 2019, 8, (7), 727.

- Escola, J.-M.; Kleijmeer, M. J.; Stoorvogel, W.; Griffith, J. M.; Yoshie, O.; Geuze, H. J., Selective enrichment of tetraspan proteins on the internal vesicles of multivesicular endosomes and on exosomes secreted by human B-lymphocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1998, 273, (32), 20121-20127.

- de Gassart, A.; Géminard, C.; Février, B.; Raposo, G.; Vidal, M., Lipid raft-associated protein sorting in exosomes. Blood 2003, 102, (13), 4336-4344.

- Mathivanan, S.; Ji, H.; Simpson, R. J., Exosomes: extracellular organelles important in intercellular communication. Journal of proteomics 2010, 73, (10), 1907-1920.

- Heijnen, H. F.; Schiel, A. E.; Fijnheer, R.; Geuze, H. J.; Sixma, J. J., Activated Platelets Release Two Types of Membrane Vesicles: Microvesicles by Surface Shedding and Exosomes Derived From Exocytosis of Multivesicular Bodies and-Granules. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 1999, 94, (11), 3791-3799.

- Lin, S.-L.; Miller, J. D.; Ying, S.-Y., Intronic microrna (mirna). Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology 2006, 2006.

- Guo, H.; Ingolia, N. T.; Weissman, J. S.; Bartel, D. P., Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature 2010, 466, (7308), 835-840.

- Goodwin, A. J.; Guo, C.; Cook, J. A.; Wolf, B.; Halushka, P. V.; Fan, H., Plasma levels of microRNA are altered with the development of shock in human sepsis: an observational study. Critical care 2015, 19, (1), 1-10.

- Sitar, M. E.; Ipek, B. O.; Karadeniz, A., Procalcitonin in the diagnosis of sepsis and correlations with upcoming novel diagnostic markers. Int J Med Biochem 2019, 2, (3), 132-40.

- Samraj, R. S.; Zingarelli, B.; Wong, H. R., Role of biomarkers in sepsis care. Shock (Augusta, Ga.) 2013, 40, (5), 358.

- Kang, H. E.; Park, D. W., Lactate as a biomarker for sepsis prognosis? Infection & chemotherapy 2016, 48, (3), 252.

- Weidhase, L.; Wellhöfer, D.; Schulze, G.; Kaiser, T.; Drogies, T.; Wurst, U.; Petros, S., Is Interleukin-6 a better predictor of successful antibiotic therapy than procalcitonin and C-reactive protein? A single center study in critically ill adults. BMC infectious diseases 2019, 19, (1), 1-7.

- Charalampos, P.; Vincent, J.-L., Sepsis biomarkers: a review. Critical care 2010, 14, R15.

- Essandoh, K.; Fan, G.-C., Role of extracellular and intracellular microRNAs in sepsis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2014, 1842, (11), 2155-2162.

- Szilágyi, B.; Fejes, Z.; Pócsi, M.; Kappelmayer, J.; Nagy Jr, B., Role of sepsis modulated circulating microRNAs. Ejifcc 2019, 30, (2), 128.

- Wang, J.-f.; Yu, M.-l.; Yu, G.; Bian, J.-j.; Deng, X.-m.; Wan, X.-j.; Zhu, K.-m., Serum miR-146a and miR-223 as potential new biomarkers for sepsis. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2010, 394, (1), 184-188.

- Roderburg, C.; Luedde, M.; Vargas Cardenas, D.; Vucur, M.; Scholten, D.; Frey, N.; Koch, A.; Trautwein, C.; Tacke, F.; Luedde, T., Circulating microRNA-150 serum levels predict survival in patients with critical illness and sepsis. PloS one 2013, 8, (1), e54612.

- Wang, H.; Meng, K.; jun Chen, W.; Feng, D.; Jia, Y.; Xie, L., Serum miR-574-5p: a prognostic predictor of sepsis patients. Shock 2012, 37, (3), 263-267.

- Willms, E.; Cabañas, C.; Mäger, I.; Wood, M. J.; Vader, P., Extracellular vesicle heterogeneity: subpopulations, isolation techniques, and diverse functions in cancer progression. Frontiers in immunology 2018, 9, 738.

- Karttunen, J.; Heiskanen, M.; Navarro-Ferrandis, V.; Das Gupta, S.; Lipponen, A.; Puhakka, N.; Rilla, K.; Koistinen, A.; Pitkänen, A., Precipitation-based extracellular vesicle isolation from rat plasma co-precipitate vesicle-free microRNAs. Journal of extracellular vesicles 2019, 8, (1), 1555410.

- Fonseka, P.; Pathan, M.; Chitti, S. V.; Kang, T.; Mathivanan, S., FunRich enables enrichment analysis of OMICs datasets. Journal of Molecular Biology 2021, 433, (11), 166747.

- Sticht, C.; De La Torre, C.; Parveen, A.; Gretz, N., miRWalk: An online resource for prediction of microRNA binding sites. PloS one 2018, 13, (10), e0206239.

- Lehner, G.; Brandtner, A.; Joannidis, M., Microvesicles in sepsis: implications for the activated coagulation system. In Annual Update in Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine 2017, Springer: 2017; pp 29-39.

- Murao, A.; Brenner, M.; Aziz, M.; Wang, P., Exosomes in Sepsis. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11, 2140.

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V. S., The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, (6478).

- Lashin, H. M.; Nadkarni, S.; Oggero, S.; Jones, H. R.; Knight, J. C.; Hinds, C. J.; Perretti, M., Microvesicle subsets in sepsis due to community acquired pneumonia compared to faecal peritonitis. Shock 2018, 49, (4), 393-401.

- Gabarin, R. S.; Li, M.; Zimmel, P. A.; Marshall, J. C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H., Intracellular and extracellular lipopolysaccharide signaling in sepsis: avenues for novel therapeutic strategies. Journal of Innate Immunity 2021, 13, (6), 321-330.

- Deng, M.; Tang, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Liu, J.; Tang, C.; Liu, Z., The endotoxin delivery protein HMGB1 mediates caspase-11-dependent lethality in sepsis. Immunity 2018, 49, (4), 740-753. e7.

- R.B. Gritte; T. Souza-Siqueira; E.B. Silva; L.C.S. Oliveira; R.C. Borges; H.H.O. Alves; L.N. Masi; G.M. Murata; R. Gorjão; A.C. Levada-Pires; A.C. Nogueira; T.C. Pithon-Curi; R. Bentes; F.G. Soriano; R. Curi; Machado, M. C. C., Evidence for Monocyte Reprogramming in a Long-Term Postsepsis Study. Critical Care Explorations 2022, 4, (8).

- Hu, Q.; Gong, W.; Gu, J.; Geng, G.; Li, T.; Tian, R.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Shao, L.; Liu, T., Plasma microRNA profiles as a potential biomarker in differentiating adult-onset Still's Disease from sepsis. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 9, 3099.

- Li, T.; Morgan, M. J.; Choksi, S.; Zhang, Y.; Kim, Y.-S.; Liu, Z.-g., MicroRNAs modulate the noncanonical transcription factor NF-κB pathway by regulating expression of the kinase IKKα during macrophage differentiation. Nature immunology 2010, 11, (9), 799-805.

- Ruan, L.; Qian, X., MiR-16-5p inhibits breast cancer by reducing AKT3 to restrain NF-κB pathway. Bioscience reports 2019, 39, (8).

- Huang, Y.; Yang, N., MicroRNA-20a-5p inhibits epithelial to mesenchymal transition and invasion of endometrial cancer cells by targeting STAT3. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology 2018, 11, (12), 5715.

- Zhao, C.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wang, G.; Yao, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhan, F.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, J.; Chen, J., miR-15b-5p resensitizes colon cancer cells to 5-fluorouracil by promoting apoptosis via the NF-κB/XIAP axis. Scientific reports 2017, 7, (1), 1-12.

- Gao, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Ha, T.; Ma, H.; Liu, L.; Kalbfleisch, J. H.; Gao, X.; Kao, R. L.; Williams, D. L., Attenuation of cardiac dysfunction in polymicrobial sepsis by microRNA-146a is mediated via targeting of IRAK1 and TRAF6 expression. The Journal of Immunology 2015, 195, (2), 672-682.

- Taganov, K. D.; Boldin, M. P.; Chang, K.-J.; Baltimore, D., NF-κB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, (33), 12481-12486.

- Zhang, Y.-G.; Song, Y.; Guo, X.-L.; Miao, R.-Y.; Fu, Y.-Q.; Miao, C.-F.; Zhang, C., Exosomes derived from oxLDL-stimulated macrophages induce neutrophil extracellular traps to drive atherosclerosis. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, (20), 2672-2682.

- Al-Banna, N.; Lehmann, C., Oxidized LDL and LOX-1 in experimental sepsis. Mediators of inflammation 2013, 2013.

- Kuhn, A. R.; Schlauch, K.; Lao, R.; Halayko, A. J.; Gerthoffer, W. T.; Singer, C. A., MicroRNA expression in human airway smooth muscle cells: role of miR-25 in regulation of airway smooth muscle phenotype. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 2010, 42, (4), 506-513.

- Varga, Z. V.; Kupai, K.; Szűcs, G.; Gáspár, R.; Pálóczi, J.; Faragó, N.; Zvara, Á.; Puskás, L. G.; Rázga, Z.; Tiszlavicz, L., MicroRNA-25-dependent up-regulation of NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) mediates hypercholesterolemia-induced oxidative/nitrative stress and subsequent dysfunction in the heart. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology 2013, 62, 111-121.

- Lv, Y.-n.; Ou-Yang, A.-J.; Fu, L.-s., MicroRNA-27a negatively modulates the inflammatory response in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated microglia by targeting TLR4 and IRAK4. Cellular and molecular neurobiology 2017, 37, (2), 195-210.

- Beneyto, L. A. P.; Luis, O. R.; Sánchez, C. S.; Simón, O. C.; Rentero, D. B.; Bayarri, V. M., Valor pronóstico de la interleucina 6 en la mortalidad de pacientes con sepsis. Medicina Clínica 2016, 147, (7), 281-286.

- Harbarth, S.; Holeckova, K.; Froidevaux, C.; Pittet, D.; Ricou, B.; Grau, G. E.; Vadas, L.; Pugin, J.; Network, G. S., Diagnostic value of procalcitonin, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8 in critically ill patients admitted with suspected sepsis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2001, 164, (3), 396-402.

- Song, J.; Park, D. W.; Moon, S.; Cho, H.-J.; Park, J. H.; Seok, H.; Choi, W. S., Diagnostic and prognostic value of interleukin-6, pentraxin 3, and procalcitonin levels among sepsis and septic shock patients: a prospective controlled study according to the Sepsis-3 definitions. BMC infectious diseases 2019, 19, (1), 1-11.

- Ethuin, F.; Delarche, C.; Gougerot-Pocidalo, M.-A.; Eurin, B.; Jacob, L.; Chollet-Martin, S., Regulation of interleukin 12 p40 and p70 production by blood and alveolar phagocytes during severe sepsis. Laboratory investigation 2003, 83, (9), 1353-1360.

- Iwashyna, T. J.; Ely, E. W.; Smith, D. M.; Langa, K. M., Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. Jama 2010, 304, (16), 1787-1794.

- Thierry, C.; Amigorena, S.; Raposo, G.; Clayton, A., Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol 2006, 3, 1-29.

- Mitchell, A. J.; Gray, W. D.; Hayek, S. S.; Ko, Y.-A.; Thomas, S.; Rooney, K.; Awad, M.; Roback, J. D.; Quyyumi, A.; Searles, C. D., Platelets confound the measurement of extracellular miRNA in archived plasma. Scientific reports 2016, 6, (1), 1-11.

- ThÚry, C.; Witwer, K.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.; Anderson, J.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G., Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, (1), 1535750.

- Pundir, S.; Martin, M. J.; O'Donovan, C.; Consortium, U., UniProt tools. Current protocols in bioinformatics 2016, 53, (1), 1.29. 1-1.29. 15.

- Cox, J.; Mann, M., MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized ppb-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nature biotechnology 2008, 26, (12), 1367-1372.

- Tyanova, S.; Temu, T.; Sinitcyn, P.; Carlson, A.; Hein, M. Y.; Geiger, T.; Mann, M.; Cox, J., The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote) omics data. Nature methods 2016, 13, (9), 731-740.

- Thomas, P. D.; Ebert, D.; Muruganujan, A.; Mushayahama, T.; Albou, L. P.; Mi, H., PANTHER: Making genome-scale phylogenetics accessible to all. Protein Science 2022, 31, (1), 8-22.

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B. M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A., Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science (New York, NY) 2015, 347, (6220), 1260419-1260419.

- Mestdagh, P.; Van Vlierberghe, P.; De Weer, A.; Muth, D.; Westermann, F.; Speleman, F.; Vandesompele, J., A novel and universal method for microRNA RT-qPCR data normalization. Genome biology 2009, 10, (6), 1-10.

- Livak, K. J.; Schmittgen, T. D., Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. methods 2001, 25, (4), 402-408.

| number of patients (%) | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 13 (36.1) |

| Male | 23 (63.9) |

| Average (SD) | 60.2 (13.2) |

| Median (min-max) | 60.5 (34-87) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Arterial hypertension | 21 (58.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14 (38.9) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2 (5.6) |

| Heart disease | 9 (25.0) |

| Acute renal insufficiency | 9 (25.0) |

| Cirrhosis | 1 (2.8) |

| Congestive heart failure | 1 (2.8) |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 2 (5.6) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 1 (2.8) |

| Dementia | 1 (2.8) |

| Chronic osteomyelitis | 1 (2.8) |

| Liver disease | 1 (2.8) |

| Sepsis focus | |

| Abdominal | 9 (25.0) |

| Leptospirosis | 1 (2.8) |

| Osteomyelitis | 1 (2.8) |

| Pancreatitis | 1 (2.8) |

| Soft parts | 1 (2.8) |

| Lungs | 12 (33.3) |

| Kidney | 6 (16.7) |

| Skin | 1 (2.8) |

| Another | 4 (11.1) |

| Vital status | |

| Survivors | 19 (52.8) |

| Deaths | 17 (47.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).