1. Introduction

The microorganisms in human body exist as mutualistic and symbiotic relationships; known as microbiota. These microbes trillions in number together with bacteria, protozoa, viruses, and fungi are present on and in our bodies (Anwar et al., 2021). These microorganisms are found on the skin, in the mouth, reproductive organs, and gut. The supposed role of microbes has been linked to the analysis, medication, and administration of numerous ailments (Abbasi et al., 2021). It has been reported that microbes associated by prevention and progression of numerous CNS diseases such as multiple sclerosis (Atabati et al., 2021). They are also associated with detection and care of cardiac problems such as hypertension (Oniszczuk et al., 2021). Many microorganisms living in the gut, assisting to digest the indigestible foods (Mukhtar et al., 2019). The gut microflora offers numerous advantages to the hosts, through a variety of physiological roles like firming up gut integrity or shaping the epithelium of intestine (Natividad et al., 2013), protecting against pathogens (Bäumler et al., 2016), harvesting energy (Den Besten et al., 2013), and regulating host immunity (Gensollen et al., 2016). However, altered microbial composition, known as dysbiosis disrupt these mechanisms (Schroeder et al., 2016).

Numerous groups of bacteria have a crucial role in the breakdown of bile salts and suppress the pathogenicity of pathogenic microbes in gut, convert pro forms of drugs into active state and lessen the harms of xenobiotic compounds by chemical alterations (Bäumler et al., 2016). Moreover, the gut microorganisms play a vital role in the production of neurotransmitters, vitamins and metabolites, the essential constituent of human health, regulate host immune system, cytokine generation, growth of lymphoid organs in the gut, growth and development of gut-associated immune system (Anwar et al., 2019). It has been reported that intestinal microbiome also plays significant part in the improvement of whole body ‘s immune status. These specific combinations of bacteria, viruses and fungi are not only essential for the distinctive care of health, but also in dispensation of exogenous compounds (medicine) intended to rectify homeostatic inequities (Anwar et al., 2015). Numerous factors involving the use of antibiotics, prebiotics and probiotics, along with geographical distribution, and environmental factors, such as air pollution, or disrupting chemicals, and hygienic conditions act as modulators, influencing the gastrointestinal microbiome functionality, makeup and diversity (Anwar et al., 2021).

According to studies, moderate amounts of species have been found and isolated from humans, divided into twelve phyla, with Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria accounting for 93.5 percent of the total. Out of the 12, three identified phyla have only one species separated from humans, like intestinal species, Akkermansia muciniphila. In human being, 386 of the known species are anaerobic and henceforth will in general be found in mucosal areas like the GI tract and the oral cavity (Hugon et al., 2015).

Dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiome is by far the most major cause of infection. Furthermore, bacterial infection and its treatment have a significant impact on the human intestinal microbiome, that determines the manifestation of infection in host body. Invading pathogens invade the intestinal mucosa, triggering a severe inflammatory reaction and the subsequent translocation of gastrointestinal microorganisms (Brenchley et al., 2012). Number of studies have reported the close link between microbial dysregulation and infection, as well as the fact that disease is linked not just to the microbes but also to viruses (Cohen et al., 2016).

Clostridium difficile overpopulation is commonly linked to antibiotic-related diarrhoea, which is one of the most common side effects of antibiotic therapy, and now it has become a public health concern (Gu et al., 2016). Clostridium difficile is spore-forming, gram-positive, anaerobic, bacillus an important element, of the human gut microflora. The decrease in the resistance contrary to toxin-producing Clostridium difficile is due to altered intestinal mucosal homeostasis and stimulation of CDI development. Studies found that either CDI is existent or not, faecal microbial diversity is reduced and intestinal bacterial diversity pompously changes in patients with antibiotics administration (Gu et al., 2016). Another research investigated that whether CDI exist or not, antibiotic medication has been associated with reduction of butyrate-forming bacteria, an upsurge of endotoxin-producing pathogens and lactate producing phylotypes in individuals (Chen et al. 2011). Helicobacter pylori bacterium are known to causes digestive problems. It has lately been related to the development of periodontitis. He looked at the link between H. pylori infection and inflammation, periodontal parameters, and periodontal pathogens. According to their findings, the frequencies of Prevotella, Treponema denticola, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Aggregatibacter actinomycete and Fusobacterium nucleatum, are much higher in H. pylori-infected patients than non-infected ones. The findings suggest that H. pylori patients had significantly increased probing depths or attachments failure, as the H. pylori may encourage the evolution of various periodontal infections and aggravate the progression of chronic periodontitis (Hu et al., 2016).

Current studies have revealed that the gut microorganisms have impact on circadian oscillations and also affect the circadian clock (Leone et al., 2015). Dysbiosis induces by of the Interruption circadian clock, which is related to the host metabolic diseases (Thaiss et al., 2014). Obesity, which is accompanied with altered metabolic pathways and gut microbiome dysbiosis, reduces intestinal epithelial barrier functioning and seems to have a significant impact on physiological functions (Tremaroli et al., 2012), like immune homeostasis and gut (De Vos et al., 2013).

The microbiota of a human stomach is shaped by a numerous factor. These are (1) The way of delivery; (2) diet during infancy and adulthood; and (3) use of antibiotics and the gut commensal community (Jandhyala et al., 2015).

Our study determined the variations in selected ora-faecal bacterial species in rural and urban regions of district Faisalabad. Also determined the variations in oro-foecal bacterial species across rural and urban individual suggested potential impact of demographic and geographic distinction on microbiome dysbiosis.

2. Materials and methods

2.2. Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by ethical Committee on Human Research (CHR) of Koç University Institutional Review Board (IRB) (2022. 216. IRB3.122) and all methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The informed consent was obtained from all subjects and their legal guardians.

2.3. Population

Ten thousand healthy male of aged 25–35 years were recruited from the two different rural and urban localities of the district Faisalabad.

2.4. Inclusion criteria

Individuals recruited have regular excrement habits. Devoid history of gastrointestinal disease such as gastritis, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, inflammatory bowel disease and peptic ulcer. No diarrhea for the previous month. The informed consent was obtained from all subjects and their legal guardians.

2.5. Study area

The city of Faisalabad one of the major cities in Punjab province of Pakistan was identified as the urban location of the study and nearby areas was identified for rural location. Sample were collected from healthy subjects (N=10,000) who lived in urban area of Faisalabad Wapda city (n=5000) located in the Faisalabad. For rural area samples were collected from subjects lived in Naimatabad (n=5000).

2.6. Dietary assessment

A self-administered evaluative food routine questionnaire was used to assess dietary patterns. All recruited individual had routine meals comprised of protein-based diets (beef, pork, poultry, eggs, fish, and cow milk) and carbohydrate-based foods (rice and rice noodle, breakfast cereal, bread, sweet potato), as well as dietary fibres (fruit and vegetables). Pakistanis eat 3 times per day the breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

2.7. Oral swab sample collection and processing

Before collecting oral rinses, people were instructed to fast for nine hours. Oral swab sample was collected in a sterile cup by healthy participants. Oral swab specimens were kept cool until they arrived at the Lab, where they have been freeze and stored at -80˚c in 50 mL collection tube. The oral rinsed samples were subsequently transported to laboratory on dry ice and stored at -80˚c until processing. We extracted DNA and amplified it in the V4 region of the 16S rRNA using primers.

2.8. Fecal sample collection

Each subject received a stool sampling kit, which included a sample box and sterilized tissue papers, as well as a question paper regarding their eating habits and a consent paper. The questionnaires were filled in volunteers according to need of research. Participants were recruited randomly through direct approach. Participants had not taken any antibiotic for at least six months prior to sampling. The consent documents were signed by and obtained from the all participants prior to fecal sample collection. Volunteers were briefed on how to use and collect the sample with minimal contamination following the detailed instructions included in the sampling kit. After samples collection, sample were collected from participants within two hours and transported on dry ice in the cooler box in the laboratory. Samples were stored immediately at −80 ℃ in the laboratory till the analysis occurs. A total of 10,000 samples were collected according to the grouping described in

Table 1.

2.9. DNA extraction and quantification

The fecal samples were kept at -80°C till genomic DNA extraction. About 30 mg of samples were used for DNA extraction. In brief, each fecal sample was diluted to 1:10 (weight/ volume) in distilled water and homogenized boiling for 2 min. The sample was then transferred into a 1.5-mL screw-capped tube. One milliliter of sample obtained was centrifuged at 14,000×g for 10 min at 4 ℃, after centrifugation, pallet was taken and dissolved in DNAzol 300 microliters. The solution was homogenized by using vortex machine. 300 microliter chloroform added to this solution incubated on ice for 30 minutes until three layers are formed. When three layers are formed upper layer containing bacterial DNA was collected and transferred it in Eppendorf of 1.5 mililiter, equal amount of isopropanole was added and freeze it overnight. Next day 70 percent ethanol was added then centrifuged at room temperature for 40 minutes at 14,000×g for washing. This washing step was repeated for three times. Every washing sample was shifted into new Eppendorf. Afterwards the lid of Eppendorf was kept open for ethanol evaporation. A 30 µl nuclease free water was added. The quality and quantity of DNA were analyzed by using Thermo Scientific™ Nano Drop 2000.

2.11. PCR and agarose gel electrophoresis

The variable segment of the microbial 16S rRNA markers were amplified by using forward and reverse primers fallowing the sample thawed on ice. The following conditions were used for primary 16S rRNA gene PCR amplification: 95 °C for 3 minutes preceded by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds each, 60 °C for 30 seconds, and 72 °C for 30 seconds, and a final extension step of 72 °C for 5 minutes. Agarose gel electrophoresis was used to determine success of amplification. Variable regions of the 16S rRNA genes were amplified in 50μl reaction volume using 0.1 ng of template DNA with different bacterial primers given in

Table 2.10 using the PCR thermocycler BioRad T100. The PCR amplification products were purified on 2% agarose gels. And the positive number of samples for various bacteria were counted and compared in each groups to calculate the microbial diversity in different population. Final concentration in gel / running buffer was as 40 mM Tris, 20 mM acetic acid, 1 mM EDTA and 3.6 Gel preparation.

Table 2.

List of forward and reverse primers for amplification of 16S rRNA collected from Macrogen, South Korea.

Table 2.

List of forward and reverse primers for amplification of 16S rRNA collected from Macrogen, South Korea.

| Primer Name |

Sequence |

| Total Bifido-F |

TCGCGTC[Y]GGTGTGAAAG |

| Total Bifido-R |

CCACATCCAGCRTCCAC |

|

Blautia spp-F |

TTGATGTGAAAGGCTGGGGCTTAC |

|

Blautia spp-R |

GGCTTAGCCACCCGACACCTA |

|

Compylobacter coli- F |

TGACGGTAGAACTTTCAAATCC |

|

Compylobacter coli- R |

GCAAGTGCTTCACCTTCGATA |

|

E Coli-F |

GTTAATACCTTTGCTCATTGA |

|

E Coli-R |

ACCAGGGTATCTAATCCTGTT |

|

Faecalibacterium-F |

GAAGGCGGCCTACTGGGCAC |

|

Faecalibacterium-R |

GTGCAGGCGAGTTGCAGCCT |

|

Firmicutes-run-F |

GGCAGCAGTRGGGAATCTTC |

|

Firmicutes-run-R |

ACAC[Y]TAG[Y]ACTCATCGTTT |

|

Fusobacterium-F |

KGGGCTCAACMCMGTATTGCGT |

|

Fusobacterium-R |

TCGCGTTAGCTTGGGCGCTG |

|

Gamma-Protebacteria-F |

TGCCGCGTGTGTGAA |

|

Gamma-Protebacteria-R |

ACTCCCCAGGCGGTCDACTTA |

| Total Lactobacillus-F |

AGCAGTAGGGAATCTTCCA |

| Total Lactobacillus-R |

CACCGCTACACATGGAG |

|

Ruminococcaceae-F |

ACTGAGAGGTTGAACGGCCA |

|

Ruminococcaceae-R |

CCTTTACACCCAGTAAWTCCGGA |

Separation, purification, and identification 0.5- to 25-kb DNA fragments with agarose gel electrophoresis was carried out in three main phases: (1) a gel was prepared with an agarose concentration appropriate for the size of DNA fragments to be kept separate; (2) DNA samples were loaded into sample wells and the gel is run at a voltage and for a period of time which will achieve optimal separation; and (3) Ethidium bromide is incorporated into the gel and electrophoresis was performed. An electrical field was used to drive negatively charged DNA throughout an agarose gel matrix forward towards a positive terminal in electrophoresis. Relatively short DNA fragments go faster through the gel than longer ones. By running a DNA fragment on a gel matrix alongside a DNA ladder, we were able to establish its approximate length.

2.12. Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare the abundance of 16S rRNA Graph Pad Prism Software, version 5 software. P value *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

3. Results

In total, 10,000 volunteers were recruited from two different geographic and demographic areas. In current study 10 bacterial species were identified using PCR in different geographic and demographic regions specifically rural and urban areas of district Faisalabad, Pakistan. A total of 10 bacterias were aimed to detect in fecal and 5 in oral sample. The list of bacterias detected in study are showed in

Table 3.

Table 3. The results showed positive expression of following bacterial species i.e: Total Bifido, ,E.coli, Blautia spp, Faecali bacteria, Firmicutes ,Total Lactobacillus and Rminococcaceae in both rural and urban regions in Gut and oral cavity of individuals. While another set of bacterial species i.e: Compylobacter coli Fusobacterium and Gamma protebacteria were not found in PCR results, finding beneficial for host as these bacterial species are considered as pathogenic.

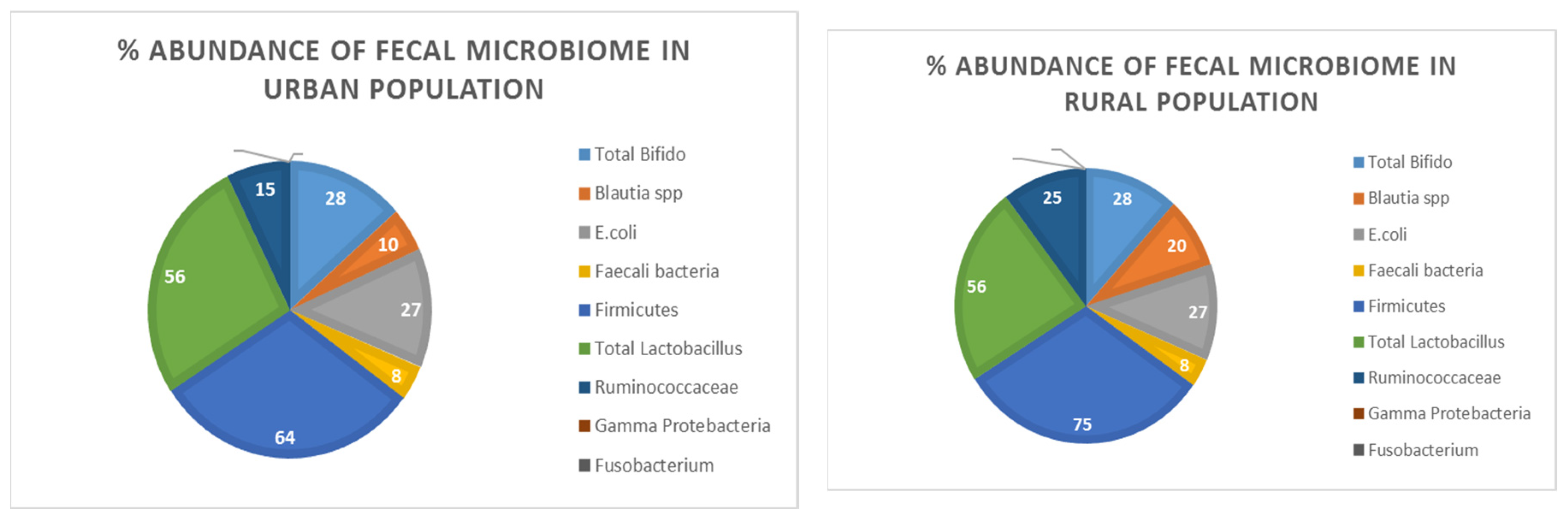

3.1. Fecal microbial profile

3.1.1. Total Bifido

Figure 1 and (Supplementary file1) illustrated % abundance and corresponding bands of Total

Bifido in the fecal samples of both rural and urban populations respectively. Results demonstrated the environmental and life style variation of people living in rural and urban areas of district Faisalabad have no effect on % abundance of Total

Bifido in the gut in these two populations.

3.1.2. Blautia spp

The presence of

Blautia spp in both rural and urban populations have been shown in

Figure 1 and (Supplementary file1) clearly depicted the variable abundance of bacteria in two demographically distinct areas. It implies the influence of environmental changes on the bacterial population of gut microbiota. the % abundance have been increased in rural populations.

3.1.3. E. coli

E. coli bacterial species found in fecal sample of human population of both rural and urban regions demonstrated no influence of life style variation in % abundance of

E. coli bacterial population in gut flora. As % abundance and representative bands are depicted in

Figure 1 and (Supplementary file1).

3.1.4. Faecali

PCR results depicted changes in the environment and people's lifestyles in rural and urban parts of Faisalabad district have no influence on the prevalence of

Faecali bacteria in the gut. However relative quantity of this bacterial specie may be decrease or increase, but found in both rural and urban areas of District Faisalabad. As % abundance and representative bands are depicted in

Figure 1 and (Supplementary file1).

3.1.5. Firmicutes

It has been found that

Firmicutes bacteria are present in both rural and urban areas of human population of District Faisalabad. The results have been depicted in

Figure 1 and (Supplementary file1) illustrated the people living in rural areas of district Faisalabad revealed elevated % abundance of

Firmicutes load in fecal samples of rural individuals.

3.1.6. Total Lactobacillus

Total

Lactobacillus bacterial specie is a part of normal gut microbiota.

Figure 1 and (Supplementary file1) indicated variations in the environmental and people's lifestyles in rural and urban areas of Faisalabad district have no influence on the % abundance of Total

Lactobacillus in gut.

3.1.7. Ruminococcaceae

The bacterial species of

Ruminococcaceae has been showed variable abundance in both rural and urban populations. Geographical and socioeconomical difference alter the gut microbial diversity. PCR results demonstrated the % abundance of

Ruminococcaceae in rural populations was elevated. As % abundance and representative bands are depicted in

Figure 1 and (Supplementary file1).

3.1.8. Gamma Protebacteria

Gamma Protebacteria in fecal sample of both rural and urban populations was devoid. As this bacterium is pathogenic and absent in both rural and urban areas of district Faisalabad it showed change in lifestyle and environment did not cause any

Gamma Protebacteria associated disease. As depicted in

Figure 1 and (Supplementary file1).

3.1.9. Fusobacterium

Fusobacterium is the pathogenic bacterial specie found in human gut microbiota in disease condition. This bacterium was included in the current study to observe change in lifestyle may influence

Fusobacterium load of gut. Results showed absence of

Fusobacterium in both rural and urban areas of District Faisalabad. As % abundance and representative bands are depicted in

Figure 1 and (Supplementary file1).

3.1.10. Compylobacter coli

The absence of

Compylobactor coli in both rural and urban population has been observed in

Figure 1 and (Supplementary file1). This bacterial specie is pathogenic and typically not found in both rural and urban regions of the district Faisalabad, it indicated lifestyle and environment variation did not contribute illness caused by this bacterium.

Figure 1.

% abundance of fecal bacterial profile in samples collected in 5000 individuals at urban and rural areas of Faisalabad. The Abundance analysis of microbiome in urban and rural individuals 16s rRNA quantification by PCR revealed a significant elevated abundance of Blautia spp, Firmicutes Ruminococcaceae, in rural population however non-significant difference in abundance of Total Bifido , E.coli , Faecali bacteria , Total Lactobacillus were found in both urban and rural population. The Compylobacter coli Fusobacterium and Gamma protebacteria bacteria were not detect in any population of study. The abundance of 16S rRNA genes comparison was carried out by Mann–Whitney U-test in Graph Pad Prism Software, version 5 software. P value *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Figure 1.

% abundance of fecal bacterial profile in samples collected in 5000 individuals at urban and rural areas of Faisalabad. The Abundance analysis of microbiome in urban and rural individuals 16s rRNA quantification by PCR revealed a significant elevated abundance of Blautia spp, Firmicutes Ruminococcaceae, in rural population however non-significant difference in abundance of Total Bifido , E.coli , Faecali bacteria , Total Lactobacillus were found in both urban and rural population. The Compylobacter coli Fusobacterium and Gamma protebacteria bacteria were not detect in any population of study. The abundance of 16S rRNA genes comparison was carried out by Mann–Whitney U-test in Graph Pad Prism Software, version 5 software. P value *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

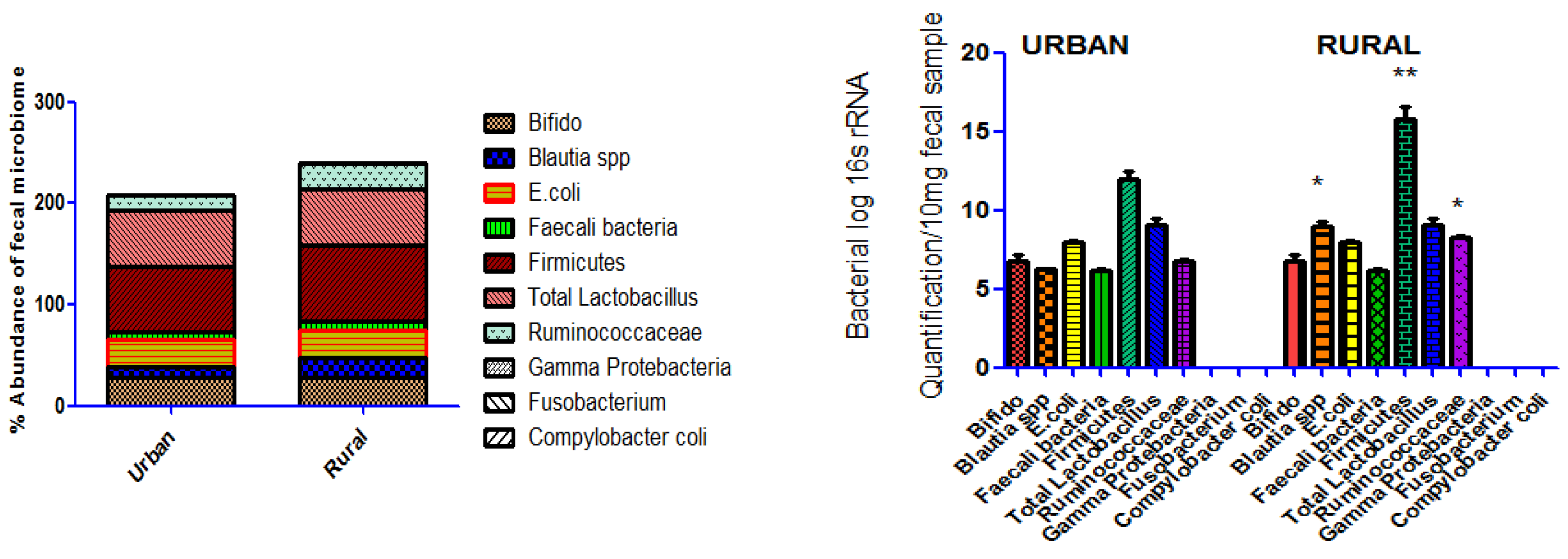

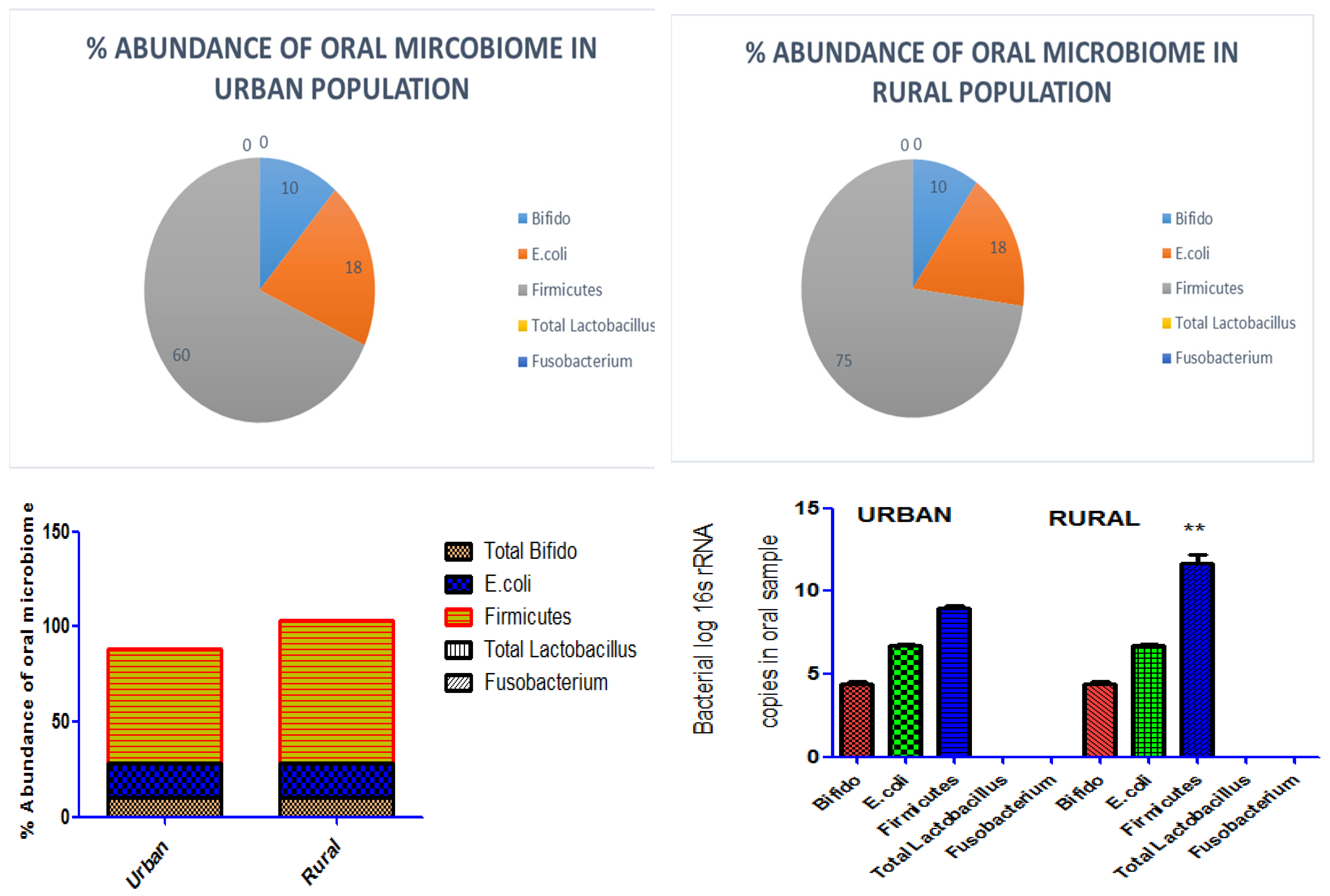

3.2. Oral microbial profile

3.2.1. Total Bifido

Total

Bifido normally present in oral sample of human populations.

Figure 3 and (Supplementary file1) depicted the % abundance and corresponding band of Total

Bifido in both rural and urban regions. It indicated the variation in environment and life style of people in rural and urban areas of district Faisalabad have no influence on Total

Bifido in the oral microflora.

3.2.2. E. coli

E. coli bacterial specie is normally present in the microbiome of human population.

Figure 3 and (Supplementary file1) depicted the % abundance and corresponding band indicated that variations in the environment and people’s lifestyles in rural and urban areas of Faisalabad district have no influence on the prevalence of

E. coli in the oral microbiota.

3.2.3. Firmicutes

PCR results demonstrated the variable microbial load of

Firmicutes bacteria in rural and urban populations. It depicted the role distinct life style on abundance of

Firmicutes bacterial population in oral microbime. The % abundance of

Firmicutes elevated in rural population. As

Figure 3 and (Supplementary file1) depicted the % abundance and corresponding bands.

3.2.4. Total Lactobacillus

The results revealed the absence of Total

Lactobacillus bacteria in both rural and urban areas population. As this bacterial specie is pathogenic, and normally not found in both rural and urban regions of the district of Faisalabad. It indicated lifestyle and environmental changes did not affect illness caused by this bacterium. As presented in

Figure 3 and (Supplementary file1) the % abundance and corresponding band.

3.2.5. Fusobacterium

The analysis showed the absence of

Fusobacterium in both rural and urban populations. Results presented in

Figure 3 and (Supplementary file1) the % abundance and corresponding band. Clearly implies null influence of environmental changes in the bacterial population of oral microbes.

Figure 3.

% abundance of oral bacterial profile in samples collected in 5000 individuals at urban and rural areas of Faisalabad. The Abundance analysis of microbiome in urban and rural individuals 16s rRNA quantification by PCR revealed a significant (P value **p<0.01) elevated abundance of Firmicutes in rural population however non-significant difference in abundance of total Bifido and E. coli was found. Total Lactobacillus and Fusobacterium were not detected in oral sample of both urban and rural population. The abundance of 16S rRNA genes comparison was carried out by Mann–Whitney U-test in Graph Pad Prism, version 5 Software.

Figure 3.

% abundance of oral bacterial profile in samples collected in 5000 individuals at urban and rural areas of Faisalabad. The Abundance analysis of microbiome in urban and rural individuals 16s rRNA quantification by PCR revealed a significant (P value **p<0.01) elevated abundance of Firmicutes in rural population however non-significant difference in abundance of total Bifido and E. coli was found. Total Lactobacillus and Fusobacterium were not detected in oral sample of both urban and rural population. The abundance of 16S rRNA genes comparison was carried out by Mann–Whitney U-test in Graph Pad Prism, version 5 Software.

Discussion

The gut microbiome, a massive habitat of microorganisms lived in the human body, located in the gut. In human intestinal tract, there are an estimated 100 trillion microorganisms, the most of which are bacteria, but also include fungus, viruses and protozoa. Initially, it was considered ten times higher microscopic cells in our bodies than human cells (Zhang et al., 2015), However, a recent discovery has led us to believe that human and microbes coexist in our bodies in a 1:1 ratio, implying that microbes and human cells are roughly equal in number (Sender et al., 2016). We all living in various geographic locations, such as the East or the West; as a result of such geographical variances, our lifestyles vary, which leads to differences in dietary habits, such as some eating more vegetables and relying solely on a fresh, leafy, and fibrous diet, while others rely solely on a protein diet, because they are more flesh lovers, or as modernization increases, we are now more prone towards junk food (Yatsunenko et al., 2012). So, these variations also affect our gut microbiome in a way that increases the number of one species while reducing the other one just by fluctuations in dietary habits (Wu et al., 2011). In the present study, the dynamics of some oral and fecal microbiota in different populations residing in various regions of district Faisalabad were evaluated in order to interpret the dysbiosis index on the basis of socioeconomic status of different areas. The effect of demographic and geographical variation on % abundance of Total Bifido, Blautia spp, E. coli, Faecali bacteria, Firmicutes, Total lactobacillus, Ruminococcaceae, Gamma Protebacteria, Fusobacterium, Compylobacter coli in fecal sample and Total bifido, E. coli, Faecali bacteria, Firmicutes, and Fusobacterium were assessed in oral samples. Results of our study showed positive expression of Total Bifido, E. coli, Faecali bacteria and total Lactobacillus, however Blautia spp, Firmicutes, Ruminococcaceae % abundance in the gut of rural and urban areas human population was varied as it was increased in rural populations. The pathogenic Gamma Protebacteria, Fusobacterium, Campylobacter coli were not detected in both demographic and geographic areas. Out of five oral detected microbial profile total Bifido and E. coli showed positive expression in rural and urban human participants. Firmicutes was detected in variable % abundance and showed to increased abundance in rural populations oral cavity. Total Lactobacillus and Fusobacterium were absent in oral sample. Total Bifido and Firmicutes were detected in both oral and fecal microbiota samples of rural and urban population of Faisalabad. These are beneficial microbes that are present in the normal flora of human gut and oral cavity. The significance of these bacteria in the gut is also confirmed by other studies that stated members of the genus Bifidobacterium have been identified as almost ubiquitous inhabitants of the human host performing an important role in the gut at birth (Biavati et al., 2006). Other studies showed the effect of geographical changes in Total Bifido and Firmicutes for instance, American, Japanese, Korean and Chinese communities showed high abundances of Firmicutes (Nam et al., 2011). At the genus levels, Japanese showed high abundances of Bifidobacterium (Nishijima et al., 2016). In line with these finding our studies also described the variable abundance of Firmicutes in the stool or oral cavity of rural and urban participants. The results of our study demonstrated the Blautia spp, Firmicutes, Ruminococcaceae abundance in the gut and Firmicutes in oral cavity of rural and urban areas human population was varied. The variation in abundance of these bacterial population depicts that the variation of living standard imparts a potential effect on gut and oral cavity bacterial profile and mediate dysbiosis associated disorders. Although, many previous researches have stated Blautia spp presence in fecal samples but the extent may vary in different population. A previous study conducted by Eren et al. (2015) represented that the Salvador sewage contained 79 of the 81 Blautia oligotypes detected in Brazilian human fecal samples whereas the combined Milwaukee sewage contained only 61 (75.0%). The occurrence of the most common Blautia oligotypes in each of the human fecal samples supports the idea that sewage samples reflect microbial populations in humans (Eren et al., 2015). Another study suggested the distinct provincial microbial structures may respond differently to diet, lifestyle and other host factors. For example, some genera varied significantly across provinces/megacities including Blautia, and Faecalibacterium. The regional variations in these genera suggested that subpopulations from different geographic locations may have variable levels of susceptibility to certain diseases (Zhang et al., 2015). Lactobacillus bacteria has been detected in current study in the fecal samples of both rural and urban areas of District Faisalabad and has not been detected in oral samples as it was mostly present in disease condition like dental caries in oral cavity and normally in gut microbiome. The findings of the present study are supported by previous studies as it has been reported that two genera, Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, both are common inhabitants of the human intestine (Marco et al., 2006). But in oral cavity the presence of Lactobacilli is correlated with dental caries (Beighton et al., 1991). In previous study it was shown that the subjects colonized with enteric pathogens belonging to the family Campylobacteraceae and 2 subjects were detected with Helicobacter. Campylobacter is the leading global cause of foodborne disease associated with the consumption of contaminated chicken, and with the consumption of contaminated water in the developing countries (Johnsonet al., 2017). In another study it has been stated that Fusobacterium sequences were enriched in carcinomas, confirmed by quantitative PCR and 16S rRNA sequence analysis of 95 carcinoma/normal DNA pairs. 52 Fusobacteria were also visualized within colorectal tumors using Fluorescence in situ hybridization (Kostic et al., 2012). Compylobactor coli and Fusobacterium were not detected in current study in both urban and rural population of Faisalabad as these are pathogenic bacteria for oral and gut health and their presence is associated with disease conditions. The variable abundance of Ruminococcus spp has been detected in the gut microbial sample of both urban and rural populations of Faisalabad. It is one of the commensal bacteria present in human gut microbiota. These findings also supported by literature i.e. it has been stated that Ruminococcus is one of the important member of microbial systems. For example, in humans, Ruminococcus spp. is found as abundant members of a ―core gut microbiome‖ (Qin et al., 2010). In another study it has been demonstrated that Ruminococcus is dominated in intestinal microbiome of healthy persons from the Netherlands (Bonder et al., 2016). Gamma protebacteria is one of the pathogenic bacteria present in gut microbiome and was not detected in present study, both in rural and urban population of Faisalabad region. Previous studies show that these bacteria are only present in the conditions involving GI inflammation and are not essentially present in gut flora (Scales et al., 2016).

We included the detection of these bacteria in current study to evaluate whether the abundance of these bacteria are affected by the geographical and demographic changes. Our study evaluated the qualitative effect of geographic and socioeconomic variation on alteration of gut and oral cavity microbiome however, genomics, proteomics and metabolic approaches are required to be elucidated.

Conclusion

We concluded that geographical and demographic variation alter the gut and oral cavity microbiota and might contribute development of dysbiosis associated systemic disorders. Our finding demonstrated the demographic and geographical variation had potential effect on dysbiosis of Blautia spp, Firmicutes, Ruminococcaceae in gut and Firmicutes in oral cavity might cause dysbiosis associated gut and other systemic disorders.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

I hereby declare that the work presented in the article is my own effort, and that the article is my own composition. No part of this article has been previously published in any journal.

Funding

Funding source was not available.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by ethical Committee on Human Research (CHR) of Koç University Institutional Review Board (IRB) (2022. 216. IRB3.122) and all methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The informed consent was obtained from all subjects and their legal guardians.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable

Data availability statement

The data used during the current study is presented in this article.

Acknowledgments

Thanks for the help and cooperation of District Faisalabad population for providing consent of study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships and declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Anwar, H., Iftikhar, A., Muzaffar, H., Almatroudi, A., Allemailem, K. S., Navaid, S., Khurshid, M. (2021). Biodiversity of Gut Microbiota: Impact of Various Host and Environmental Factors. BioMed Research International, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, H., Irfan, S., Hussain, G., Faisal, M. N., Muzaffar, H., Mustafa, I., . . . Ullah, M. I. (2019). Gut microbiome: A new organ system in body Parasitology and Microbiology Research (pp. 1-20): Intech Open.

- Abbasi, A., Ghasempour, Z., Sabahi, S., Kafil, H. S., Hasannezhad, P., Rahbar Saadat, Y., & Shahbazi, N. (2021). The biological activities of postbiotics in gastrointestinal disorders. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Atabati, H., Yazdanpanah, E., Mortazavi, H., Bajestani, S. G., Raoofi, A., Esmaeili, S.-A.,Sathyapalan, T. (2021). Immunoregulatory effects of tolerogenic probiotics in multiple sclerosis. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 1286, 87-105. [CrossRef]

- Bäumler, A. J., & Sperandio, V. (2016). Interactions between the microbiota and pathogenic bacteria in the gut. Nature, 535(7610), 85-93. [CrossRef]

- Beighton, D., Hellyer, P. H., Lynch, E. J. R., & Heath, M. R. (1991). Salivary levels of mutans streptococci, lactobacilli, yeasts, and root caries prevalence in non- institutionalized elderly dental patients. Community dentistry and oral epidemiology, 19(5), 302-307. [CrossRef]

- Biavati, B., & Mattarelli, P. (2006). pp. 322–382. The Family Bifidobacteriaceae: Springer Verlag.

- Boursier, J., Mueller, O., Barret, M., Machado, M., Fizanne, L., Araujo-Perez, F., David, Brenchley, J. M., & Douek, D. C. (2012). Microbial translocation across the GI tract. Annual review of immunology, 30, 149-173. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2016). Vaginal microbiome affects HIV risk: American Association for the Advancement of Science. [CrossRef]

- Den Besten, G., Van Eunen, K., Groen, A. K., Venema, K., Reijngoud, D.-J., & Bakker, B. M. (2013). The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. Journal of lipid research, 54(9), 2325-2340. [CrossRef]

- De Vos, W. M., & Nieuwdorp, M. (2013). A gut prediction. Nature, 498(7452), 48-49. [CrossRef]

- Eren, A. M., Sogin, M. L., Morrison, H. G., Vineis, J. H., Fisher, J. C., Newton, R. J., & Huttenhower, C. (2015). Identifying personal microbiomes using metagenomic codes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(22), E2930-E2938. [CrossRef]

- Gensollen, T., Iyer, S. S., Kasper, D. L., & Blumberg, R. S. (2016). How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science, 352(6285), 539-544. [CrossRef]

- Gu, S., Chen, Y., Zhang, X., Lu, H., Lv, T., Shen, P.,Li, L. (2016). Identification of key taxa that favor intestinal colonization of Clostridium difficile in an adult Chinese population. Microbes and infection, 18(1), 30-38. [CrossRef]

- Hugon, P., Dufour, J.-C., Colson, P., Fournier, P.-E., Sallah, K., & Raoult, D. (2015). A comprehensive repertoire of prokaryotic species identified in human beings. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 15(10), 1211-1219. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z., Zhang, Y., Li, Z., Yu, Y., Kang, W., Han, Y., . . . Sun, Y. (2016). Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection on chronic periodontitis by the change of microecology and inflammation. Oncotarget, 7(41), 66700. [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, S. M., Talukdar, R., Subramanyam, C., Vuyyuru, H., Sasikala, M., & Reddy, D.N. (2015). Role of the normal gut microbiota. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG, 21(29), 8787.66. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. J., Shank, J. M., & Johnson, J. G. (2017). Current and potential treatments for reducing Campylobacter colonization in animal hosts and disease in humans. Frontiers in microbiology, 8, 487. [CrossRef]

- Kostic, A. D., Gevers, D., Pedamallu, C. S., Michaud, M., Duke, F., Earl, A. M., & Meyerson, M. (2012). Genomic analysis identifies association of Fusobacterium with colorectal carcinoma. Genome research, 22(2), 292-298. [CrossRef]

- Leone, V., Gibbons, S. M., Martinez, K., Hutchison, A. L., Huang, E. Y., Cham, C. M., . . .Hubert, N. (2015). Effects of diurnal variation of gut microbes and high-fat feeding on host circadian clock function and metabolism. Cell host & microbe, 17(5), 681-689. [CrossRef]

- L. A. (2016). The severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with gut dysbiosis and shift in the metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Hepatology, 63(3),764-775. [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, I., Anwar, H., Hussain, G., Rasul, A., Naqvi, S. A. R., Faisal, M. N., Mirza, O.A. (2019). Detection of Paracetamol as substrate of the gut microbiome.

- M. Anokhin, A. P. (2012). Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature, 486(7402), 222-227.80. [CrossRef]

- Marco, M. L., Pavan, S., & Kleerebezem, M. (2006). Towards understanding molecular modes of probiotic action. Current opinion in biotechnology, 17(2), 204-210. [CrossRef]

- Natividad, J. M., & Verdu, E. F. (2013). Modulation of intestinal barrier by intestinal microbiota: pathological and therapeutic implications. Pharmacological research, 69(1), 42-51. [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y. D., Jung, M. J., Roh, S. W., Kim, M. S., & Bae, J. W. (2011). Comparative analysis of Korean human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PloS one, 6(7), e22109. [CrossRef]

- Nishijima, S., Suda, W., Oshima, K., Kim, S. W., Hirose, Y., Morita, H., & Hattori, M. (2016). [CrossRef]

- Oniszczuk, A., Oniszczuk, T., Gancarz, M., & Szymańska, J. (2021). Role of gut microbiota, probiotics and prebiotics in the cardiovascular diseases. Molecules, 26(4), 1172. [CrossRef]

- Qin, J., Li, R., Raes, J., Arumugam, M., Burgdorf, K. S., Manichanh, C., ... and Wang, J. (2010). A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomics sequencing. nature, 464(7285), 59-65. [CrossRef]

- Scales, B. S., Dickson, R. P., & Huffnagle, G. B. (2016). A tale of two sites: how inflammation can reshape the microbiomes of the gut and lungs. Journal of leukocyte biology, 100(5), 943-950. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, B. O., & Bäckhed, F. (2016). Signals from the gut microbiota to distant organs in physiology and disease. Nature medicine, 22(10), 1079-1089. [CrossRef]

- Sender, R., Fuchs, S., & Milo, R. (2016). Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS biology, 14(8), e1002533. [CrossRef]

- Thaiss, C. A., Zeevi, D., Levy, M., Zilberman-Schapira, G., Suez, J., Tengeler, A. C., Zmora, N. (2014). Transkingdom control of microbiota diurnal oscillations promotes metabolic homeostasis. Cell, 159(3), 514-529. [CrossRef]

- The gut microbiome of healthy Japanese and its microbial and functional uniqueness. DNA research, 23(2), 125-133. [CrossRef]

- Tremaroli, V., & Bäckhed, F. (2012). Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature, 489(7415), 242-249. [CrossRef]

- Yatsunenko, T., Rey, F. E., Manary, M. J., Trehan, I., Dominguez-Bello, M. G., Contreras,Wu, G. D., Chen, J., Hoffmann, C., Bittinger, K., Chen, Y. Y., Keilbaugh, S. A., ... & Lewis, J. D. (2011). Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science, 334(6052), 105-108. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Guo, Z., Xue, Z., Sun, Z., Zhang, M., Wang, L., . . . Cao, H. (2015). A phylofunctional core of gut microbiota in healthy young Chinese cohorts across lifestyles, geography and ethnicities. The ISME journal, 9(9), 1979-1990. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).