Submitted:

17 February 2023

Posted:

20 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Previous Research

1.1.1. The seasonal Effect on Patient Admissions

1.1.2. Models Used to Estimate the Patient's Length of Stay

2. Materials and Methods

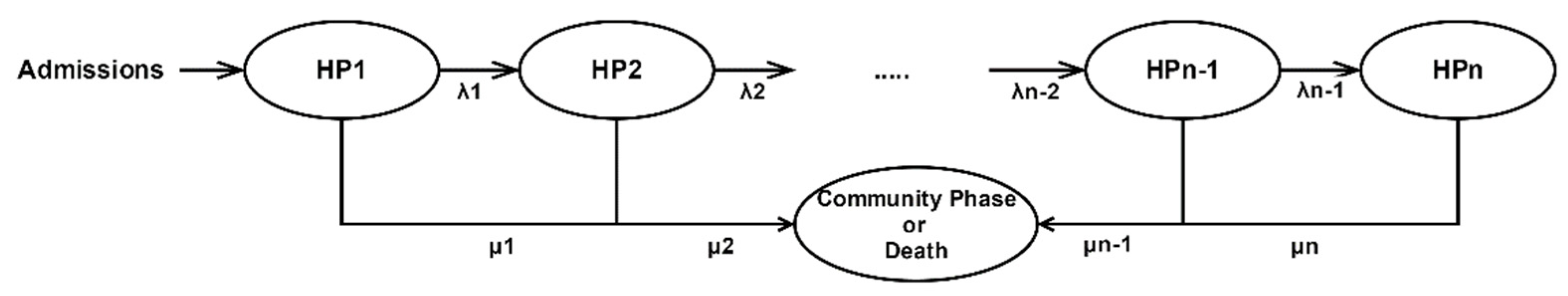

2.1. Coxian Phase-Type Distribution

2.2. Phase-Type Survival Tree

3. Implementation

3.1. The Dataset and Some Data Analysis

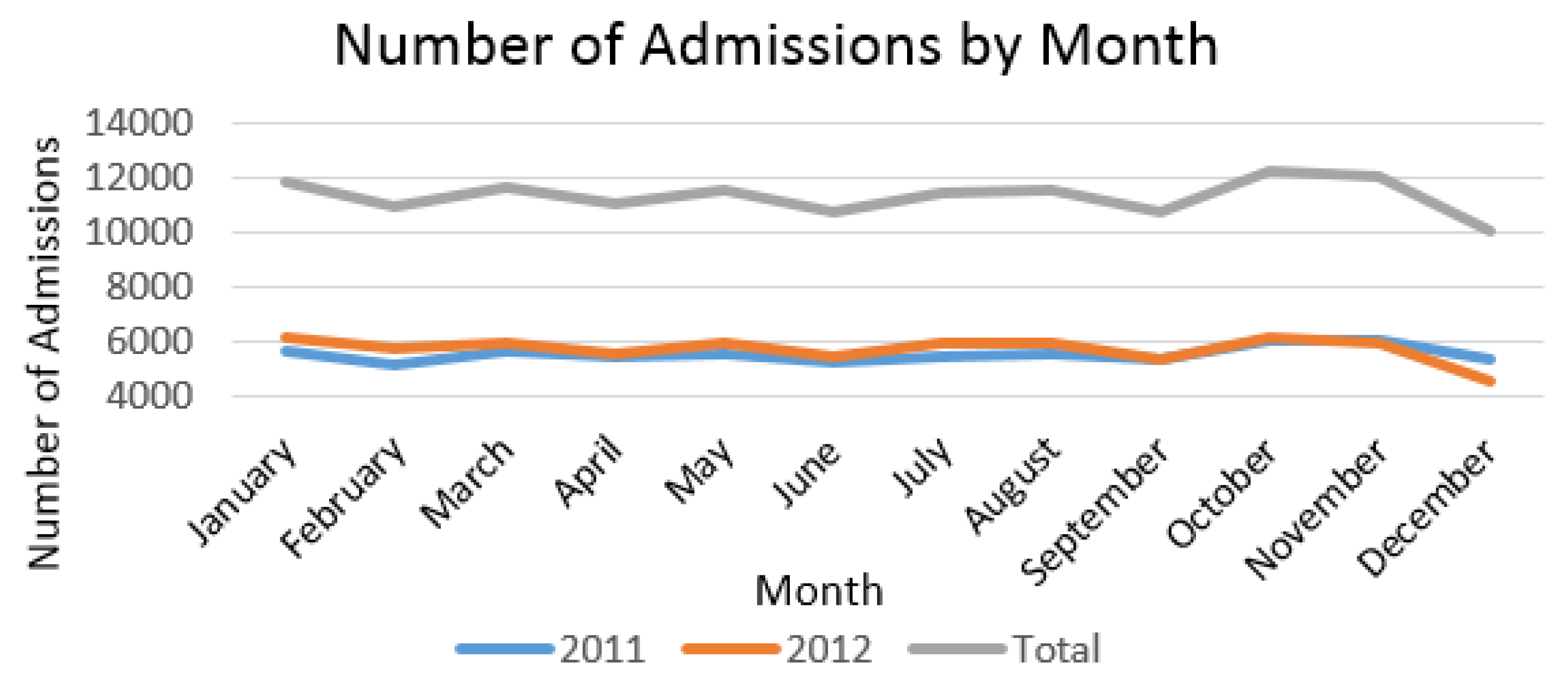

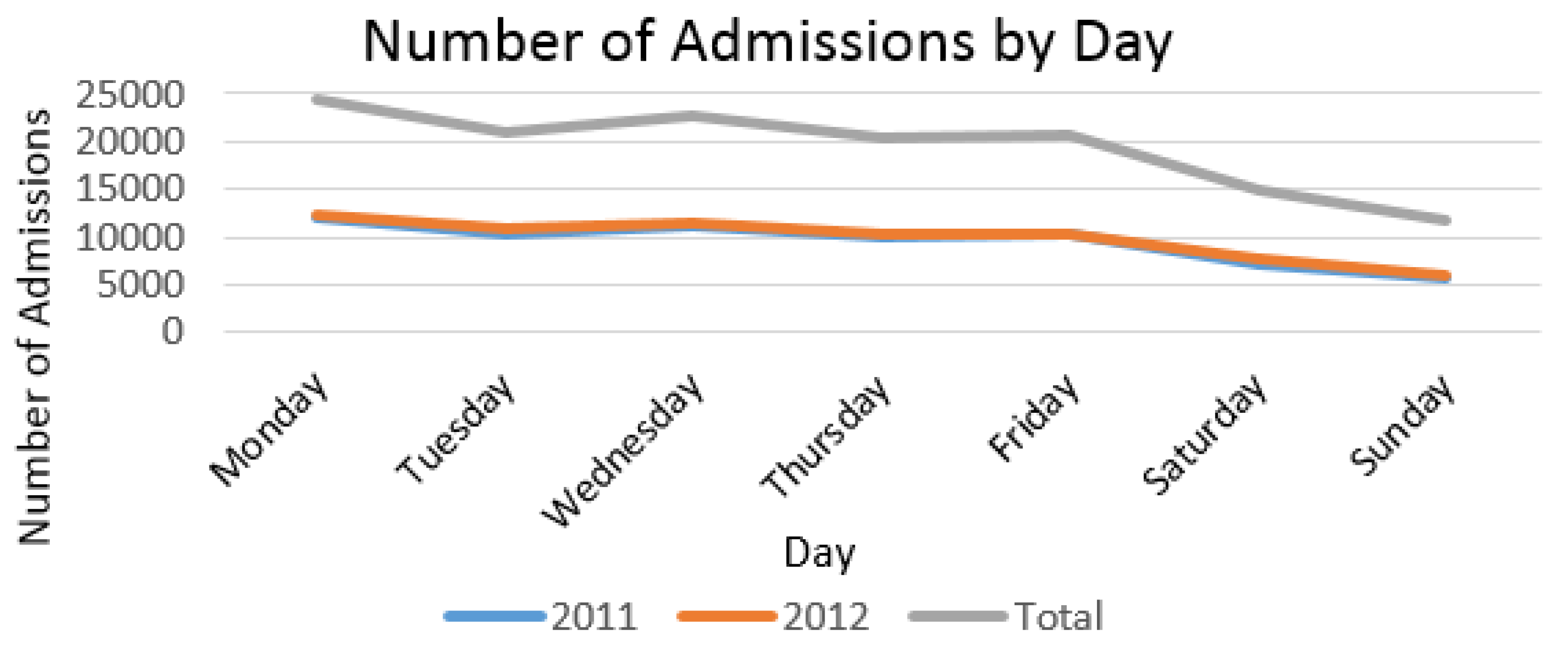

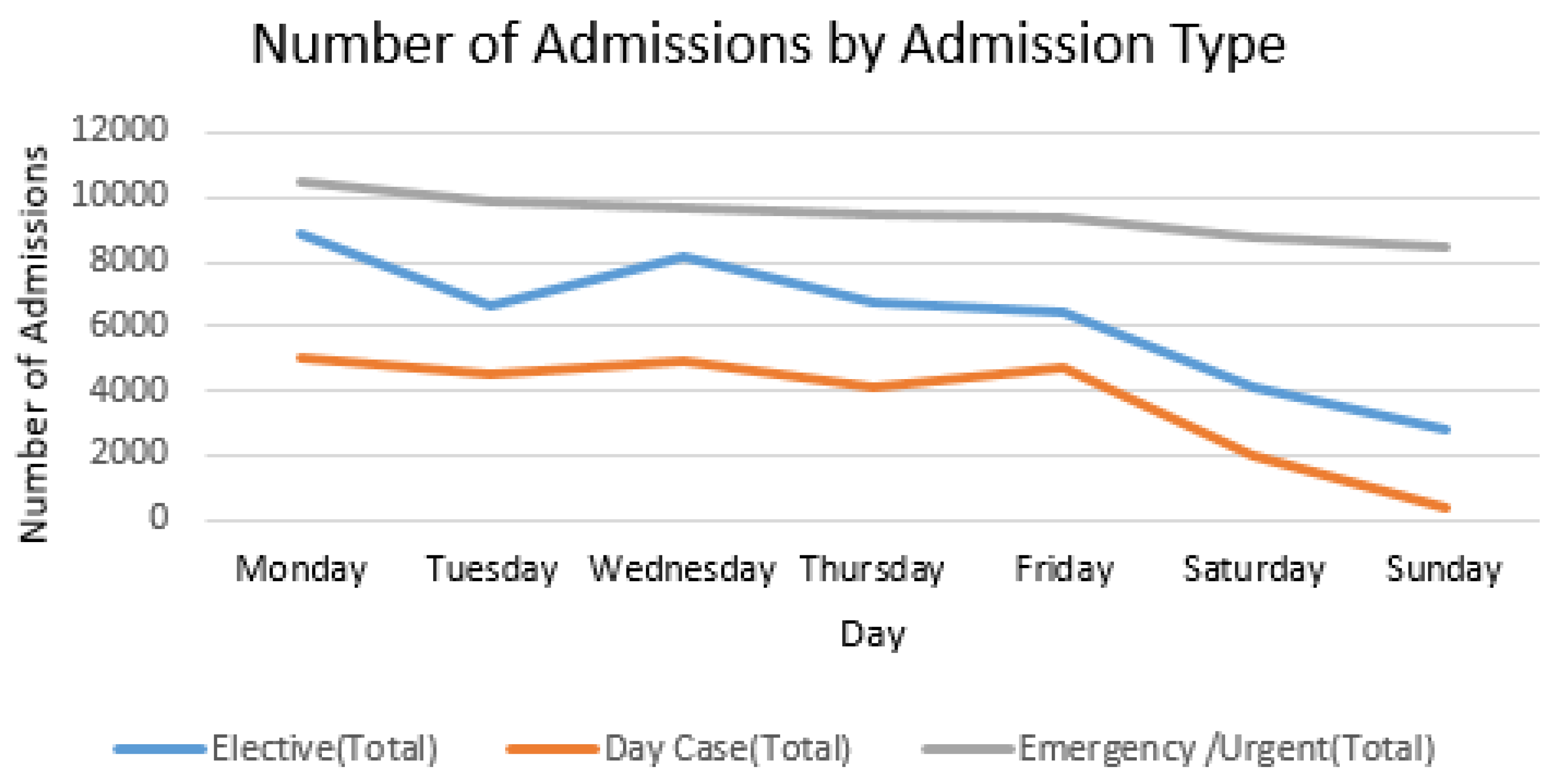

3.1.1. Admissions Data

3.1.2. Covariants

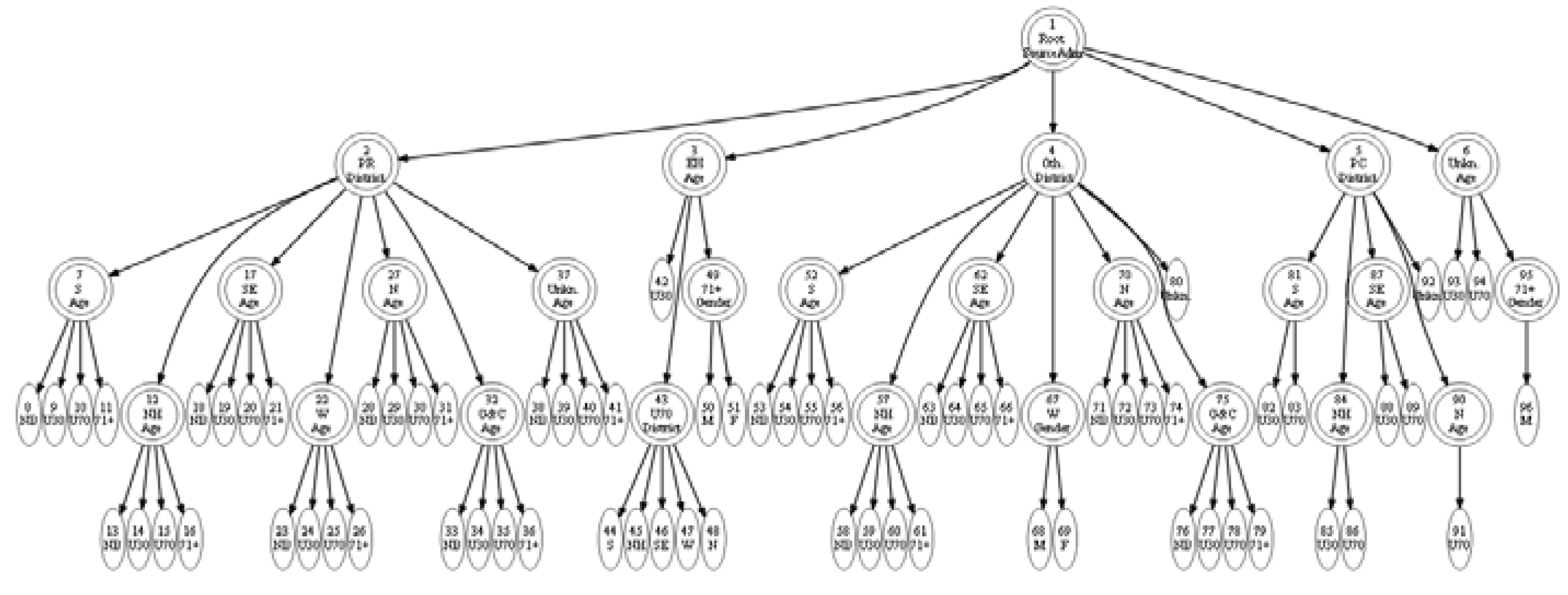

3.2. Phase-Type Survival Trees

3.2.1. Length of Stay Analysis

3.2.2. Admissions Analysis:

4. Result & Evaluation

4.1. Predictions:

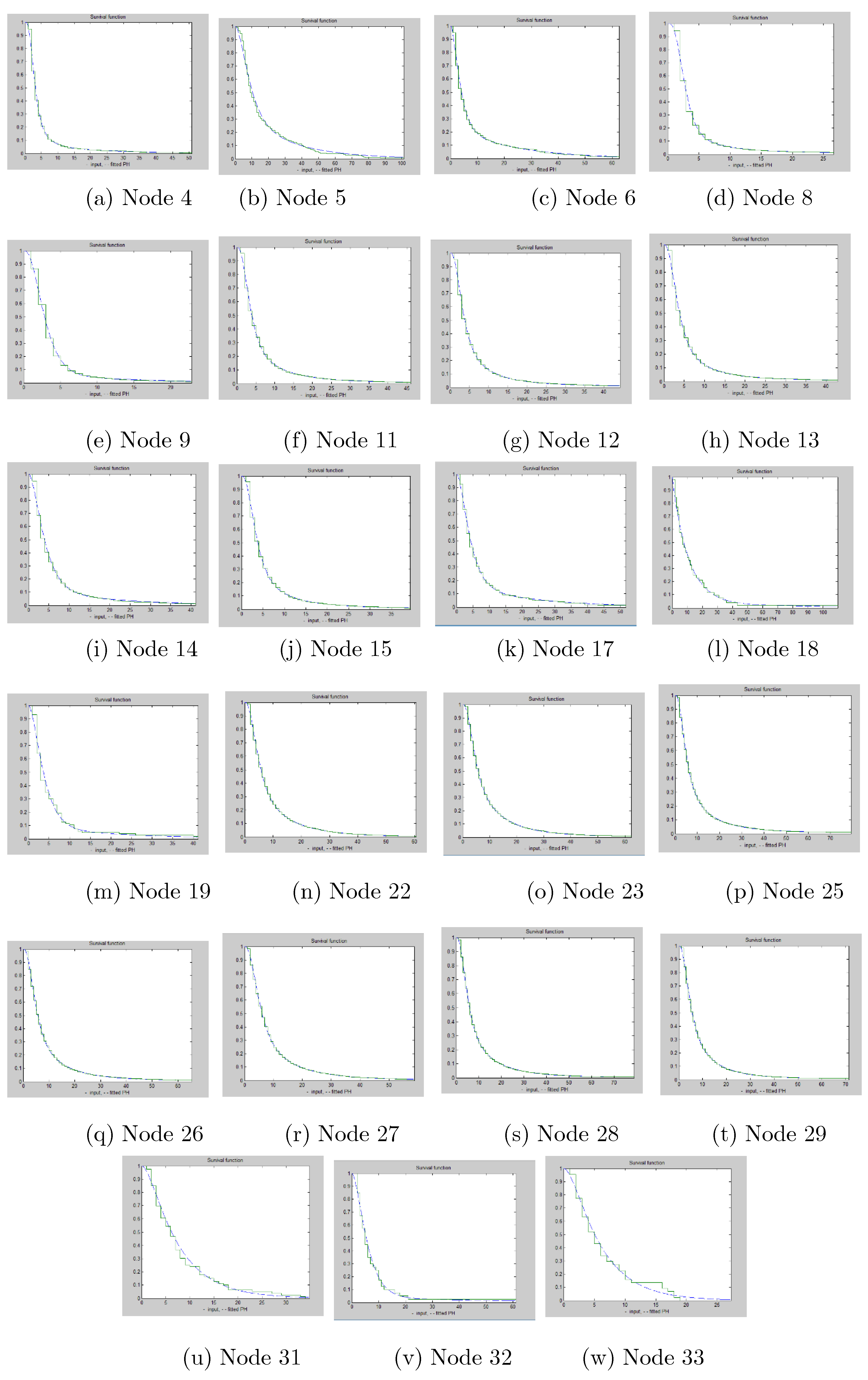

4.1.1. Personal Characteristics Model

4.2. Admissions Analysis

4.2.1. Personal Characteristics Model

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. Telek A. Horvath. Approximating heavy tailed behaviour with phase-type distributions. 2000.

- S. Asmussen, O. Nerman, and M. Olsson. Fitting phase-type distributions via the em algorithm. Scandinavian J. of Stat., 23(4):419–441, 1996.

- M. W. Cooke, S. Wilson, J. Halsall, and A. Roalfe. Total time in english accident and emergency departments is related to bed occupancy. Emergency Medicine J., 21(5):575–576, 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Fackrell. Modelling healthcare systems with phase-type distributions. Health Care Manage. Sci., 12(1):11–26, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Faddy. On inferring the number of phases in a coxian phase-type distribution. Commun. in Stat. Part C: Stochastic Models, 14(1-2):407–417, 1998. [CrossRef]

- V. L. Fullerton and K. J. Crawford. The winter bed crisis - quantifying seasonal effects on hospital bed usage. QJM: monthly J. of the Assoc. of Physicians, 92(4):199– 206, 1999.

- M. J. Faddy and S. I. McClean. Analysing data on lengths of stay of hospital patients using phase-type distributions. Appl. Stochastic Models Bus. Ind., 15(4):311– 317, 1999.

- L. Garg, S. I. McClean, M. Barton, B. J. Meenan, and K. Fullerton. Intelligent patient management and resource planning for complex, heterogeneous, and stochastic healthcare systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. A., Syst. Humans, 42(6):1332–1345, 2012. [CrossRef]

- F. Gorunescu, S. I. McClean, and P. H. Millard. A queuing model for bed-occupancy management and planning of hospitals. The J. of the Operational Research Soc., 53(1):19–24, 2002.

- L. Garg, S. McClean, B. Meenan, and P. Millard. A phase type survival tree model for clustering patients' length of stay. In Edmundas K. Zavadskas Leonidas Sakalauskas, Christos Skiadas, editor, Proceedings of the XIII Interna tional Conference on Applied Stochastic Models and Data Analysis (ASMDA 2009), pages 497–502. Vilnius Gediminas Technical University Press, 2009.

- L. Garg, S. McClean, B. Meenan, and P. Millard. A non-homogeneous discrete time markov model for admission scheduling and resource planning in a cost or capacity constrained healthcare system. Health Care Manag Sci, 13(2):155–169, 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. Garg, S. McClean, B. Meenan, and P. Millard. Phase-type survival trees and mixed distribution survival trees for clustering patients' hospital length of stay. Informatica, 22(1):57–72, 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. V. Green. How many hospital beds? Inquiry, 39(4):400–412, 2002.

- K. Hampel. Modelling phase-type distributions. University of Adelaide, South Australia, 1997.

- G. D. Hutcheson and N. Sofroniou. The Multivariate Social Scientist. SAGE, 1999.

- M. A. Johnson. Selecting parameters of phase distributions: combining non-linear programming heuristics and erlang distributions. ORSA J. on Comput., 5(1):69–83, 1993.

- R. Jones. Myths of ideal hospital size. Medical J. of Australia, 193(5):298–300, 2010. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Keegan. Hospital bed occupancy: more than queuing for a bed. Medical J. of Australia, 193(5):291–293, 2010.

- P. J. Kuzdrall, N. K. Kwak, and H. Schmitz. Simulating space requirements and scheduling policies in a hospital surgical suite. Simulation, 36(5):163–171, 1891. [CrossRef]

- S. I. McClean, L. Garg, B. Meenan, and P. H. Millard. Optimal control of patient admissions to satisfy resource restrictions. 21st IEEE Int. Symp. on Comput. Based Medical Syst., pages 512–517, 2008.

- S. I. McClean and A. H. Marshall. Using coxian phase-type distributions to identify patient characteristics for duration of stay in hospital. Healthcare Manage. Sci., 7(4):285–289, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Nerman, S. Asmussen, and M. Olsson. Papers and programs for downloading, empht.

- M. Olsson. Estimation of phase-type distributions from censored data. Scand. J. of Stat., 23(4):443–460, 1996.

- D. Worthington. Hospital waiting list management models. The J. of the Operational Research Soc., 42(10):833–843, 1991.

- T. J. Wu and A. Sepulveda. The weighted average information criterion for order selection in time series and regression models. Stat. and Probability Letters, 39(1):1– 10, 1998. [CrossRef]

- TOMASELLI, G., GARG, L., GUPTA, V., XUEREB, P.A., BUTTIGIEG, S.C. and VASSALLO, P., 2020. Communicating Corporate Social Responsibility in Healthcare Through Digital and Traditional Tools: A Two-Country Analysis. Novel Theories and Applications of Global Information Resource Management. IGI Global, pp. 184-208.

- GAFA, M., GARG, L., MASALA, G. and MCCLEAN, S.I., 2017. Applications of phase type survival trees in HIV disease progression modelling, 2017 17th International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications (ICCSA) 2017, IEEE, pp. 1-8.

- GARG, L., MULVANEY, A., GUPTA, V. and CALLEJA, N., 2015. Real-Time Hospital Bed Occupancy and Requirements Forecasting, 22nd EurOMA International Annual Conference (EurOMA 2015), June 26th- July 1st., At Neuchatel, Switzerland 2015.

- Garg, L., McClean, S.I., Barton, M., Meenan, B.J., Fullerton, K., Buttigieg, S.C., Micallef, A. (2022). Phase-Type Survival Trees to Model a Delayed Discharge and its Effect in a Stroke Care Unit. Algorithms, 15(11), 414. [CrossRef]

- Garg, L., McClean, S.I., Barton, M., Meenan, B.J., Fullerton, K., Kontonatsios, G., Trovati, M., Konkontzelos, I., Xu, X., Farid, M., 2021 Evaluating Different Selection Criteria for Phase Type Survival Tree Construction. Big Data Research. 15;25:100250. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, G.H., Davis, L.E. and Leifer, R.P., 1966. Prediction of hospital length of stay. Health services research, 1(3), p.287.

- Gustafson, D.H., 1968. Length of stay: prediction and explanation. Health Services Research, 3(1), p.12.

- Abd-Elrazek, M.A., Eltahawi, A.A., Abd Elaziz, M.H. & Abd-Elwhab, M.N. 2021, "Predicting length of stay in hospitals intensive care unit using general admission features", Ain Shams Engineering Journal, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 3691-3702. [CrossRef]

- Achilonu, O.J., Fabian, J., Bebington, B., Singh, E., Nimako, G., Eijkemans, R.M.J.C. & Musenge, E. 2021, "Use of Machine Learning and Statistical Algorithms to Predict Hospital Length of Stay Following Colorectal Cancer Resection: A South African Pilot Study", Frontiers in Oncology, vol. 11. [CrossRef]

- Alsinglawi, B., Alshari, O., Alorjani, M., Mubin, O., Alnajjar, F., Novoa, M. & Darwish, O. 2022, "An explainable machine learning framework for lung cancer hospital length of stay prediction", Scientific Reports, vol. 12, no. 1. [CrossRef]

- An, J., Jung, M., Ryu, S., Choi, Y. & Kim, J. 2023, "Analysis of length of stay for patients admitted to Korean hospitals based on the Korean National Health Insurance Service Database", Informatics in Medicine Unlocked, vol. 37. [CrossRef]

- Andiani, M.S., Gustina, M., Camilla, D.R., Yulianti, F., Putri, E., Cahyani, S.D. & Rahayu, S. 2022, "Factors Influencing the Patients' Length of Stay in a Tertiary Hospital Emergency Department", HIV Nursing, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 2179-2185.

- Aßfalg, V., Hassiotis, S., Radonjic, M., Göcmez, S., Friess, H., Frank, E. & Königstorfer, J. 2022, "Implementation of discharge management in the surgical department of a university hospital: exploratory analysis of costs, length of stay, and patient satisfaction", Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 348-356.

- Bann, M., Rosenthal, M.A. & Meo, N. 2022, "Optimizing hospital capacity requires a comprehensive approach to length of stay: Opportunities for integration of “medically ready for discharge” designation", Journal of Hospital Medicine, vol. 17, no. 12, pp. 1021-1024. [CrossRef]

- Bastakoti, M., Muhailan, M., Nassar, A., Sallam, T., Desale, S., Fouda, R., Ammar, H. & Cole, C. 2022, "Discrepancy between emergency department admission diagnosis and hospital discharge diagnosis and its impact on length of stay, up-Triage to the intensive care unit, and mortality", Diagnosis, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 107-114.

- Bayer-Oglesby, L., Zumbrunn, A. & Bachmann, N. 2022, "Social inequalities, length of hospital stay for chronic conditions and the mediating role of comorbidity and discharge destination: A multilevel analysis of hospital administrative data linked to the population census in Switzerland", PLoS ONE, vol. 17, no. 8 August. [CrossRef]

- Chrusciel, J., Girardon, F., Roquette, L., Laplanche, D., Duclos, A. & Sanchez, S. 2021, "The prediction of hospital length of stay using unstructured data", BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, vol. 21, no. 1.

- Colella, Y., De Lauri, C., Ponsiglione, A.M., Giglio, C., Lombardi, A., Borrelli, A., Amato, F. & Romano, M. 2021, "A comparison of different machine learning algorithms for predicting the length of hospital stay for pediatric patients", ACM International Conference Proceeding Series.

- Davis, M.P., Van Enkevort, E.A., Elder, A., Young, A., Correa Ordonez, I.D., Wojtowicz, M.J., Ellison, H., Fernandez, C. & Mehta, Z. 2022, "The Influence of Palliative Care in Hospital Length of Stay and the Timing of Consultation", American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, vol. 39, no. 12, pp. 1403-1409. [CrossRef]

- Del Giorno, R., Quarenghi, M., Stefanelli, K., Rigamonti, A., Stanglini, C., De Vecchi, V. & Gabutti, L. 2021, "Phase angle is associated with length of hospital stay, readmissions, mortality, and falls in patients hospitalized in internal-medicine wards: A retrospective cohort study", Nutrition, vol. 85.

- Dogu, E., Albayrak, Y.E. & Tuncay, E. 2021, "Length of hospital stay prediction with an integrated approach of statistical-based fuzzy cognitive maps and artificial neural networks", Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 483-496. [CrossRef]

- Dykes, P.C., Lowenthal, G., Lipsitz, S., Salvucci, S.M., Yoon, C., Bates, D.W. & An, P.G. 2022, "Reducing ICU Utilization, Length of Stay, and Cost by Optimizing the Clinical Use of Continuous Monitoring System Technology in the Hospital", American Journal of Medicine, vol. 135, no. 3, pp. 337-341.e1.

- Eskandari, M., Alizadeh Bahmani, A.H., Mardani-Fard, H.A., Karimzadeh, I., Omidifar, N. & Peymani, P. 2022, "Evaluation of factors that influenced the length of hospital stay using data mining techniques", BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, vol. 22, no. 1. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C., Pan, Y., Zhao, L., Niu, Z., Guo, Q. & Zhao, B. 2022, "A Machine Learning-Based Approach to Predict Prognosis and Length of Hospital Stay in Adults and Children With Traumatic Brain Injury: Retrospective Cohort Study", Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 24, no. 12. [CrossRef]

- Fekadu, G., Lamessa, A., Mussa, I., Beyene Bayissa, B. & Dessie, Y. 2022, "Length of stay and its associated factors among adult patients who visit Emergency Department of University Hospital, Eastern Ethiopia", SAGE Open Medicine, vol. 10. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, G.A. & Vatcheva, K.P. 2022, "A comparison of statistical methods for modeling count data with an application to hospital length of stay", BMC Medical Research Methodology, vol. 22, no. 1. [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, A., Picone, I., Latessa, I. & Cuocolo, A. 2021, "Modelling the length of hospital stay in medicine and surgical departments", ACM International Conference Proceeding Series.

- Ghosh, A.K., Unruh, M.A., Ibrahim, S. & Shapiro, M.F. 2022, "Association Between Patient Diversity in Hospitals and Racial/Ethnic Differences in Patient Length of Stay", Journal of General Internal Medicine, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 723-729. [CrossRef]

- Hajj, A.E., Labban, M., Ploussard, G., Zarka, J., Abou Heidar, N., Mailhac, A. & Tamim, H. 2022, "Patient characteristics predicting prolonged length of hospital stay following robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy", Therapeutic Advances in Urology, vol. 14. [CrossRef]

- Han, T.S., Murray, P., Robin, J., Wilkinson, P., Fluck, D. & Fry, C.H. 2022, "Evaluation of the association of length of stay in hospital and outcomes", International Journal for Quality in Health Care, vol. 34, no. 2. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.H., Horrocks, D., Leung, C., Richardson, M.B., Sheehy, A.M. & Locke, C.F.S. 2021, "The increasing impact of length of stay “outliers” on length of stay at an urban academic hospital", BMC Health Services Research, vol. 21, no. 1.

- Jain, R., Singh, M., Rao, A.R. & Garg, R. 2022, "Machine Learning Models To Predict Length Of Stay In Hospitals", Proceedings - 2022 IEEE 10th International Conference on Healthcare Informatics, ICHI 2022, pp. 545.

- Keene, S.E. & Cameron-Comasco, L. 2022, "Implementation of a geriatric emergency medicine assessment team decreases hospital length of stay", American Journal of Emergency Medicine, vol. 55, pp. 45-50. [CrossRef]

- Kolcun, J.P.G., Covello, B., Gernsback, J.E., Cajigas, I. & Jagid, J.R. 2022, "Machine learning to predict passenger mortality and hospital length of stay following motor vehicle collision", Neurosurgical Focus, vol. 52, no. 4. [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, M., Kamata, K. & Tokuda, Y. 2022, "Impact of the hospitalist system on inpatient mortality and length of hospital stay in a teaching hospital in Japan: a retrospective observational study", BMJ open, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. e054246. [CrossRef]

- Lauque, D., Khalemsky, A., Boudi, Z., Östlundh, L., Xu, C., Alsabri, M., Onyeji, C., Cellini, J., Intas, G., Soni, K.D., Junhasavasdikul, D., Cabello, J.J.T., Rathlev, N.K., Liu, S.W., Camargo, C.A., Slagman, A., Christ, M., Singer, A.J., Houze-Cerfon, C.-., Aburawi, E.H., Tazarourte, K., Kurland, L., Levy, P.D., Paxton, J.H., Tsilimingras, D., Kumar, V.A., Schwartz, D.G., Lang, E., Bates, D.W., Savioli, G., Grossman, S.A. & Bellou, A. 2023, "Length-of-Stay in the Emergency Department and In-Hospital Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis", Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 12, no. 1. [CrossRef]

- Lequertier, V., Wang, T., Fondrevelle, J., Augusto, V. & Duclos, A. 2021, "Hospital Length of Stay Prediction Methods: A Systematic Review", Medical care, vol. 59, no. 10, pp. 929-938.

- Li, H.-., Chen, C.C.-., Yeh, T.Y.-., Liao, S.-., Hsu, A.-., Wei, Y.-., Shun, S.-., Ku, S.-. & Inouye, S.K. 2022, "Predicting hospital mortality and length of stay: A prospective cohort study comparing the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist versus Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit", Australian Critical Care. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Liu, H., Wang, X. & Tu, W. 2022, "Semi-parametric time-to-event modelling of lengths of hospital stays", Journal of the Royal Statistical Society.Series C: Applied Statistics, vol. 71, no. 5, pp. 1623-1647. [CrossRef]

- Likka, M.H. & Kurihara, Y. 2022, "Analysis of the Effects of Electronic Medical Records and a Payment Scheme on the Length of Hospital Stay", Healthcare Informatics Research, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 35-45. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. & Qin, S. 2022, An Interpretable Machine Learning Approach for Predicting Hospital Length of Stay and Readmission.

- Mashao, K., Heyns, T. & White, Z. 2021, "Areas of delay related to prolonged length of stay in an emergency department of an academic hospital in South Africa", African Journal of Emergency Medicine, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 237-241. [CrossRef]

- MEKHALDI, R.N., CAULIER, P., CHAABANE, S., CHRAIBI, A. & PIECHOWIAK, S. 2021, "A comparative study of machine learning models for predicting length of stay in hospitals", Journal of Information Science and Engineering, vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 1025-1038.

- Negasi, K.B., Tefera Gonete, A., Getachew, M., Assimamaw, N.T. & Terefe, B. 2022, "Length of stay in the emergency department and its associated factors among pediatric patients attending Wolaita Sodo University Teaching and Referral Hospital, Southern, Ethiopia", BMC Emergency Medicine, vol. 22, no. 1. [CrossRef]

- Profeta, M., Cesarelli, G., Giglio, C., Ferrucci, G., Borrelli, A. & Amato, F. 2021, "Influence of demographic and organizational factors on the length of hospital stay in a general medicine department: Factors influencing length of stay in general medicine", ACM International Conference Proceeding Series.

- Quirós-González, V., Bueno, I., Goñi-Echeverría, C., García-Barrio, N., del Oro, M., Ortega-Torres, C., Martín-Jurado, C., Pavón-Muñoz, A.L., Hernández, M., Ruiz-Burgos, S., Ruiz-Morandy, M., Pedrera, M., Serrano, P. & Bernal, J.L. 2022, "What about the weekend effect? Impact of the day of admission on in-hospital mortality, length of stay and cost of hospitalization", Journal of Healthcare Quality Research, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 366-373.

- Rahman, M.M., Kundu, D., Suha, S.A., Siddiqi, U.R. & Dey, S.K. 2022, "Hospital patients’ length of stay prediction: A federated learning approach", Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 7874-7884. [CrossRef]

- Renwick, K.A., Sanmartin, C., Dasgupta, K., Berrang-Ford, L. & Ross, N. 2022, "The Influence of Psychosocial Factors on Hospital Length of Stay Among Aging Canadians", Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, vol. 8. [CrossRef]

- Rothman, R.D., Peter, D.J. & Harte, B.J. 2021, "Improving Healthcare Value: Managing Length of Stay and Improving the Hospital Medicine Value Proposition", Journal of hospital medicine, vol. 16, no. 10, pp. 620-622. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R., Singh, B.K., Rautaray, S. & Pandey, M. 2022, Length of Stay Prediction of Patients Suffering from Different Kind of Disease to Manage Resource and Manpower of Hospitals.

- Shevchenko, E.V., Danilov, G.V., Usachev, D.Y., Lukshin, V.A., Kotik, K.V. & Ishankulov, T.A. 2022, "Artificial intelligence guided predicting the length of hospital-stay in a neurosurgical hospital based on the text data of electronic medical records", Zhurnal Voprosy Nejrokhirurgii Imeni N.N.Burdenko, vol. 86, no. 6, pp. 43-51. [CrossRef]

- Shin, J., San Gabriel, M.C.P., Ho-Periola, A., Ramer, S., Kwon, Y. & Bang, H. 2022, "The Impact of Legal Procedures on Hospital Length of Stay: Balancing Legal and Clinical Concerns", Journal of Korean Academy of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 181-191. [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S., Whitaker, B., Mouat-Hunter, A. & McCrory, B. 2022, "Predicting Length of Stay using machine learning for total joint replacements performed at a rural community hospital", PLoS ONE, vol. 17, no. 11 November. [CrossRef]

- Suha, S.A. & Sanam, T.F. 2022, "A Machine Learning Approach for Predicting Patient's Length of Hospital Stay with Random Forest Regression", 2022 IEEE Region 10 Symposium, TENSYMP 2022.

- Wang, T., Zhang, H., Duclos, A., Payet, C. & Li, D. 2022, "Prediction of hospital length of stay to achieve flexible healthcare in the field of Internet of Vehicles", Transactions on Emerging Telecommunications Technologies, vol. 33, no. 5. [CrossRef]

- Wondmagegn, B.Y., Xiang, J., Dear, K., Williams, S., Hansen, A., Pisaniello, D., Nitschke, M., Nairn, J., Scalley, B., Xiao, A., Jian, L., Tong, M., Bambrick, H., Karnon, J. & Bi, P. 2021, "Increasing impacts of temperature on hospital admissions, length of stay, and related healthcare costs in the context of climate change in Adelaide, South Australia", Science of the Total Environment, vol. 773. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z., Zhao, C., Scales, C.D., Henao, R. & Goldstein, B.A. 2022, "Predicting in-hospital length of stay: a two-stage modeling approach to account for highly skewed data", BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, vol. 22, no. 1. [CrossRef]

- Yokokawa, D., Shikino, K., Kishi, Y., Ban, T., Miyahara, S., Ohira, Y., Yanagita, Y., Yamauchi, Y., Hayashi, Y., Ishizuka, K., Hirose, Y., Tsukamoto, T., Noda, K., Uehara, T. & Ikusaka, M. 2022, "Does scoring patient complexity using COMPRI predict the length of hospital stay? A multicentre case-control study in Japan", BMJ open, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. e051891. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J., Tisdale, R.L., Heidenreich, P.A. & Sandhu, A.T. 2022, "Disparities in Hospital Length of Stay Across Race and Ethnicity Among Patients With Heart Failure", Circulation: Heart Failure, vol. 15, no. 11, pp. E009362. [CrossRef]

- Zolbanin, H.M., Davazdahemami, B., Delen, D. & Zadeh, A.H. 2022, "Data analytics for the sustainable use of resources in hospitals: Predicting the length of stay for patients with chronic diseases", Information and Management, vol. 59, no. 5. [CrossRef]

| Admission Type |

Grp No |

No of Admissions |

Total LOS (Days) |

Average LOS (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elective/Planned procedure | 1 | 43 589 | 108 714 | 2.49 |

| Day Case | 2 | 25 748 | 2 856 | 0.11 |

| Emergency | 3 | 66 167 | 389 277 | 5.88 |

| Sun. | Mon. | Tue. | Wed. | Thur. | Fri. | Sat. | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan. | 1135 | 2423 | 1897 | 1837 | 1630 | 1650 | 1250 | 11822 |

| Feb. | 989 | 1942 | 1663 | 2013 | 1585 | 1518 | 1202 | 10912 |

| Mar. | 917 | 1855 | 1799 | 2010 | 1941 | 1851 | 1258 | 11631 |

| Apr. | 999 | 2179 | 1634 | 1783 | 1580 | 1555 | 1305 | 11035 |

| May | 999 | 2064 | 1941 | 1994 | 1780 | 1621 | 1128 | 11527 |

| Jun. | 867 | 1835 | 1528 | 1888 | 1629 | 1731 | 1252 | 10730 |

| Jul. | 1113 | 2174 | 1873 | 1745 | 1528 | 1793 | 1222 | 11448 |

| Aug. | 849 | 2042 | 1779 | 2097 | 1802 | 1815 | 1112 | 11496 |

| Sept. | 934 | 1874 | 1623 | 1668 | 1756 | 1666 | 1189 | 10710 |

| Oct. | 973 | 2402 | 1947 | 2026 | 1683 | 1783 | 1394 | 12208 |

| Nov. | 946 | 1942 | 1971 | 2091 | 1891 | 1865 | 1278 | 11984 |

| Dec. | 894 | 1671 | 1404 | 1572 | 1469 | 1729 | 1262 | 10001 |

| Total | 11615 | 24403 | 21059 | 22724 | 20274 | 20577 | 14852 | 135504 |

| Group | Group Number | Number of Admissions | Total LOS (Days) | Average LOS (Days) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male (M) | 1 | 64347 | 237774 | 3.7 | |

| Female (F) | 2 | 71154 | 263066 | 3.7 | ||

| Unclassified (U) | 3 | 3 | 7 | 2.33 | ||

| Age | New Born (NB) | 1 | 2001 | 13602 | 6.8 | |

| Under 30 (U30) | 2 | 26675 | 61710 | 2.31 | ||

| Under 70 (U70) | 3 | 70972 | 213759 | 3.01 | ||

| Over70 (70+) | 4 | 35856 | 2117733 | 5.91 | ||

| District | South (S) | 1 | 30141 | 116659 | 3.87 | |

| Northern Harbour (NH) | 2 | 43544 | 163957 | 3.77 | ||

| South Eastern (SE) | 3 | 20140 | 70867 | 3.52 | ||

| Western (W) | 4 | 20231 | 68680 | 3.39 | ||

| North (N) | 5 | 18320 | 71210 | 3.89 | ||

| Gozo & Comino (G&C) | 2 | 2877 | 8402 | 2.92 | ||

| Unknown (Unkn.) | 7 | 251 | 1072 | 4.27 | ||

| Source Adm | Private Residence (PR) | 1 | 131486 | 467002 | 3.55 | |

| Elderly Home (EH) | 2 | 2153 | 17741 | 8.24 | ||

| Other (Oth.) | 3 | 1719 | 15565 | 9.05 | ||

| Police Custody (PC) | 7 | 121 | 432 | 3.57 | ||

| Unknown (Unkn.) | 8 | 25 | 107 | 4.28 |

| Group No (LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase (x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1 | 1 | 5 |

361646.8 00352 |

6.8833 36 |

66166 | ||

| (Gender) | Male (1) | 4 | 177934.678 409 |

6.8636 62 |

32534 | ||

| Female (2) | 5 | 183735.661 181 |

6.9023 68 |

33632 | |||

| Total |

361670.339 590 |

-23.539238 | 66166 | ||||

| (Age) | New Born(1) | 3 | 10012.7788 53 |

8.4770 89 |

1723 | ||

| Under 30 (2) | 3 | 61903.7200 90 |

3.9866 51 |

14448 | |||

| Under 70 (3) | 5 | 151714.199 007 |

6.2546 08 |

28783 | |||

| Over 70 (4) | 3 | 131504.220 027 |

9.5800 05 |

21212 | |||

| Total |

355134.917 977 |

6511.8823 75 |

66166 | ||||

| (District) | South(1) | 5 | 85076.4757 44 |

7.0394 28 |

15425 | ||

| Northern Harbour (2) | 8 | 117008.277 057 |

6.9202 93 |

21655 | |||

| North(3) | 8 | 51220.9755 15 |

6.6327 38 |

9560 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 6 | 47328.3647 78 |

7.1001 95 |

8673 | |||

| Western (5) | 6 | 53183.5224 45 |

6.5479 29 |

10067 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 4 | 3414.70992 5 |

8.6470 70 |

561 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 3 | 1158.46334 9 |

5.5200 11 |

225 | |||

| Total |

358390.788 813 |

3256.0115 39 |

66166 | ||||

| (SourceAd) | Home/Private Residence (1) | 6 | 342853.702 690 |

6.8778 48 |

62768 | ||

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 6 | 10848.8042 71 |

7.4701 27 |

1925 | |||

| Other (3) | 6 | 7224.35563 7 |

6.3847 84 |

1354 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 4 | 527.989474 | 5.9793 81 |

97 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 2 | 123.147744 | 5.8636 39 |

22 | |||

| Total |

361577.999 816 |

68.800536 | 66166 | ||||

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE | |||||||

| NEWBORN | 10012.778853 | ||||||

| (NewBorn, Gender) | New Born(1) | Male (1) | 7 | 5671.189081 | 8.468910 | 981 | |

| Female (2) | 3 | 4328.550269 | 8.487877 | 742 | |||

| Total | 9999.739350 | 13.039503 | 1723 | ||||

| (NewBorn, District) | New Born (1) | South(1) | 4 | 1989.266679 | 6.852457 | 366 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 6 | 2930.781916 | 9.024242 | 495 | |||

| North(3) | 3 | 1766.753425 | 9.600010 | 290 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 6 | 1379.362716 | 8.834041 | 235 | |||

| Western (5) | 3 | 1826.139737 | 8.422087 | 308 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 1 | 130.293698 | 6.681803 | 22 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 1 | 36.823822 | 4.285702 | 7 | |||

| Total | 10059.421993 | -46.643140 | 1723 | ||||

| (NewBorn, SourceAd) | New Born (1) | Home/Private Residence (1) | 6 | 5820.815591 | 5.087955 | 1262.000000 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | |||

| Other (3) | 4 | 3476.917454 | 17.789126 | 460.000000 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | |||||||

| Unknown (5) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | |||

| Total | 9297.733045 | - | 1722.000000 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 30 | 61903.720090 | ||||||

| (Under30,Gender) | Under 30 (2) | Male (1) | 8 | 24762.357659 | 4.157465 | 6014 | |

| Female (2) | 4 | 34819.058665 | 3.864831 | 8434 | |||

| Total | 59581.416324 | 2322.303766 | 14448 | ||||

| (Under30,District) | Under 30 (2) | South(1) | 4 | 12229.294247 | 3.908124 | 3015 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 7 | 19064.333156 | 3.920145 | 4646 | |||

| North(3) | 8 | 10468.167480 | 4.010334 | 2516 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 8 | 7760.544477 | 4.123213 | 1818 | |||

| Western (5) | 6 | 9248.253348 | 3.992421 | 2243 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 5 | 670.160344 | 5.035972 | 139 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 2 | 367.065126 | 5.098594 | 71 | |||

| Total | 59807.818178 | 2095.901912 | 14448 | ||||

| (Under30 SourceAd) | Under30 (2) | Home/Private Residence (1) | 5 | 59322.168631 | 3.993065 | 14280 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 1 | 17.814737 | 2.249994 | 4 | |||

| Other (3) | 5 | 454.471483 | 3.509091 | 110 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 2 | 203.869298 | 3.404259 | 47 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 1 | 33.103980 | 3.285708 | 7 | |||

| Total | 60031.428129 | 1872.291961 | 14448 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 70 | 151714.199007 | ||||||

| (Under70,Gender) | Under70 (3) | Male(1) | 8 | 83826.550005 | 6.427080 | 15908 | |

| Female(1) | 5 | 66625.781453 | 6.041493 | 12875 | |||

| Total | 150452.331458 | 1261.867549 | 28783 | ||||

| (Under70, District) | Under70(3) | South(1) | 8 | 36179.722530 | 6.491151 | 6839 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 7 | 47896.621672 | 6.245476 | 9231 | |||

| North(3) | 5 | 21792.241004 | 6.115920 | 4227 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 4 | 19000.962563 | 6.234211 | 3642 | |||

| Western (5) | 5 | 22724.694230 | 5.925784 | 4460 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 3 | 1694.239739 | 8.551612 | 281 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 3 | 541.203201 | 5.747590 | 103 | |||

| Total | 149829.684939 | 1884.514068 | 28783 | ||||

| (Under70, SourceAd) | Under70 (3) | Home/Private Residence (1) | 5 | 147334.046566 | 6.187096 | 28057 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 4 | 1106.978811 | 12.406056 | 165 | |||

| Other (3) | 3 | 2941.858154 | 8.160019 | 500 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 2 | 233.070968 | 4.448993 | 49 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 1 | 74.800853 | 7.499985 | 12 | |||

| Total | 151690.755352 | 23.443655 | 28783 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over 70 | 131504.220027 | ||||||

| (Over70, Gender) | Over 70 (4) | Male(1) | 8 | 58227.021014 | 9.111098 | 9631 | |

| Female(1) | 5 | 72557.524021 | 9.969958 | 11581 | |||

| Total | 130784.545035 | 21212 | |||||

| (Over70,District) | Over70 (4) | South(1) | 4 | 32111.561935 | 9.485891 | 5205 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 6 | 44822.046650 | 9.634491 | 7283 | |||

| North(3) | 5 | 15668.195104 | 9.491888 | 2527 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 6 | 18437.143066 | 9.868703 | 2978 | |||

| Western (5) | 5 | 18559.234106 | 9.336389 | 3056 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 1 | 841.396961 | 12.411740 | 119 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 2 | 252.519962 | 6.477275 | 44 | |||

| Total | 130692.097784 | 21212 | |||||

| Over70, SourceAd) | Over70(4) | Home/Private Residence (1) | 5 | 118526.930185 | 9.570515 | 19169 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 5 | 10955.926971 | 9.904898 | 1756 | |||

| Other (3) | 4 | 1686.065782 | 8.176068 | 284 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 1 | 26.631132 | 12.999959 | 3 | |||

| Total | 131195.554070 | 21212 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (NewBorn, Gender) | 9999.739350 | ||||||

| Male | 5671.189081 | ||||||

| (Male, District) | Male (1) | South(1) | 4 | 1254.339181 | 7.906975 | 215 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 5 | 1581.650098 | 7.764708 | 272 | |||

| North(3) | 3 | 1045.542060 | 10.64672 | 167 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 4 | 754.318483 | 9.776922 | 130 | |||

| Western (5) | 4 | 945.469803 | 6.289771 | 176 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 1 | 135.295601 | 18.235257 | 17 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 1 | 27.446517 | 7.499974 | 4 | |||

| Total | 5744.061743 | -72.872662 | 981 | ||||

| (Male, Source Adm) | Male (1) | Home/Private Residence (1) | 8 | 3245.521267 | 5.026874 | 707 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Other (3) | 3 | 2062.865571 | 17.35037 | 274 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Total | 5308.386838 | 362.802243 | 981 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (NewBorn, Gender) | 9999.739350 | ||||||

| Female | 4328.550269 | ||||||

| (Female, District) | Female (2) | South(1) | 4 | 855.680118 | 7.993377 | 151 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 3 | 1260.685410 | 7.25561 | 223 | |||

| North(3) | 3 | 784.207481 | 10.731718 | 123 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 3 | 635.191831 | 8.095251 | 105 | |||

| Western (5) | 3 | 805.786816 | 9.4091 | 132 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 1 | 35.389634 | 9.599978 | 5 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 1 | 20.039458 | 4.333319 | 3 | |||

| Total | 4396.980748 | -68.430479 | 742 | ||||

| (Female, Source Adm) | Female (2) | Home/Private Residence (1) | 6 | 2597.152945 | 5.165765 | 555 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Other (3) | 3 | 1445.680286 | 18.435491 | 186 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 1 | ||||||

| Total | 4042.833231 | - | 742 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Under30,Gender) | 59581.416324 | ||||||

| Male | 24762.357659 | ||||||

| (Male, District) | Male (1) | South(1) | 4 | 5015.288548 | 3.938272 | 1215 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 7 | 7842.125327 | 3.886901 | 1901 | |||

| North(3) | 4 | 4443.013215 | 4.152089 | 1052 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 4 | 3191.036908 | 4.158877 | 749 | |||

| Western (5) | 5 | 4106.294365 | 3.878392 | 995 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 4 | 301.828482 | 5.65574 | 61 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 7 | 219.464227 | 5.219529 | 41 | |||

| Total | 25119.051072 | -356.693413 | 6014 | ||||

| (Male, Source Adm) | Male (1) | Home/Private Residence (1) | 5 | 24609.783767 | 4.008127 | 5905 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 8 | 25.784190 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Other (3) | 3 | 298.838775 | 3.514286 | 70 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 2 | 136.570976 | 3.343766 | 32 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 1 | 23.068196 | 2.800001 | 5 | |||

| Total | 25094.045904 | -331.688245 | 6014 | ||||

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Under30,Gender) | 59581.416324 | ||||||

| Female | 34819.058665 | ||||||

| (Female, District) | Female (2) | South(1) | 4 | 7249.484970 | 3.887779 | 1800 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 7 | 11294.974230 | 3.94317 | 2745 | |||

| North(3) | 8 | 6076.287810 | 3.90847 | 1464 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 4 | 4624.380902 | 4.098221 | 1069 | |||

| Western (5) | 5 | 5172.844942 | 4.083332 | 1248 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 4 | 391.544707 | 5.01282 | 78 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 2 | 157.062802 | 4.933335 | 30 | |||

| Total | 34966.580363 | -147.521698 | 8434 | ||||

| (Female, Source Adm) | Female (2) | Home/Private Residence (1) | 7 | 34765.233298 | 3.982446 | 8375 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 8 | 24.488864 | 2.5 | 2 | |||

| Other (3) | 2 | 174.300341 | 3.500003 | 40 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 1 | 70.391080 | 3.53332 | 15 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 8 | 29.186046 | 4.500001 | 2 | |||

| Total | 35063.599629 | -244.540964 | 8434 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under70, South | 36179.722530 | ||||||

| (South,Gender) | South(1) | Male(1) | 7 | 21259.453641 | 6.658919 | 3958 | |

| Female (2) | 4 | 15123.963246 | 6.260690 | 2881 | |||

| Total | 36383.416887 | 6839 | |||||

| (South, SourceAd) | South(1) | Home/Private Residence (1) | 7 | 35068.570609 | 6.426725 | 6653 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 2 | 436.714463 | 11.140626 | 64 | |||

| Other (3) | 3 | 511.342182 | 8.730343 | 89 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 2 | 146.623489 | 4.225823 | 31 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 8 | 28.374166 | 7.499998 | 2 | |||

| Total | 36191.624909 | 6839 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under70, Northern Harbor | 47896.621672 | ||||||

| (Northern Harbour, Gender) | Northern Harbour (2) | Male(1) | 7 | 25791.494476 | 6.431719 | 4899 | |

| Female(2) | 4 | 22470.801040 | 6.034865 | 4332 | |||

| Total | 48262.295516 | 9231 | |||||

| (Northern Harbour, Source Ad) | Northern Harbout | Home/Private Residence (1) | 7 | 46877.911687 | 6.191394 | 9065 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 3 | 248.362703 | 13.861127 | 36 | |||

| Other (3) | 3 | 737.934459 | 7.959033 | 122 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 3 | 29.896774 | 8.400001 | 3 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 1 | 34.054318 | 8.399973 | 5 | |||

| Total | 47928.159941 | 9231 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under70, North | 21792.241004 | ||||||

| (North, Gender) | North | Male | 5 | 12264.120596 | 6.121713 | 2358 | |

| Female | 7 | 9613.629943 | 6.108613 | 1869 | |||

| Total | 21877.750539 | 4227 | |||||

| (North, Source Ad) | North | Home/Private Residence (1) | 7 | 21353.617068 | 6.051817 | 4149 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 2 | 111.206699 | 22.214268 | 14 | |||

| Other (3) | 2 | 304.696250 | 7.313725 | 51 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 1 | 59.829022 | 4.999993 | 11 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 8 | 23.024782 | 2.000000 | 2 | |||

| Total | 21852.373821 | 4227 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 70, South Eastern | 19000.962563 | ||||||

| (South Eastern, Gender) | South Eastern | Male | 7 | 10563.552355 | 6.486868 | 1980 | |

| Female | 8 | 8504.979825 | 5.933213 | 1662 | |||

| Total | 19068.532180 | 3642 | |||||

| (South Eastern, Source Ad) | South Eastern | Home/Private Residence (1) | 6 | 18234.008928 | 6.209596 | 3502 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 1 | 116.581524 | 8.722206 | 18 | |||

| Other (3) | 4 | 672.250660 | 6.570248 | 121 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 5 | 2.153548 | 7.000001 | 1 | |||

| Total | 19024.994660 | 3642 | |||||

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under70, Western | 22724.694230 | ||||||

| (Western, Gender) | Western | Male | 5 | 12873.941204 | 6.140891 | 2470 | |

| Female | 7 | 9915.033235 | 5.658793 | 1990 | |||

| Total | 22788.974439 | 4460 | |||||

| (Western, Source Ad) | Western | Home/Private Residence (1) | 7 | 22142.923818 | 5.865305 | 4358 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 3 | 223.497916 | 11.121216 | 33 | |||

| Other (3) | 3 | 372.982708 | 7.333353 | 63 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 1 | 22.902645 | 4.249986 | 4 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 8 | 32.464970 | 10.999995 | 2 | |||

| Total | 22794.772057 | 4460 | |||||

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under70, Gozo&Comino | 1694.239739 | ||||||

| (Gozo&Comino, Gender) | G&C | Male | 3 | 1070.155036 | 8.477530 | 178 | |

| Female | 3 | 635.879929 | 8.679620 | 103 | |||

| Total | 1706.034965 | 281 | |||||

| (Gozo&Comino, Source Ad) | G&C | Home/Private Residence (1) | 3 | 1314.692761 | 7.445427 | 229 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Other (3) | 2 | 376.458138 | 13.423041 | 52 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Total | 1691.150899 | 281 | |||||

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under70, Unknown | 541.203201 | ||||||

| (Unknown, Gender) | Unknown | Male | 3 | 364.431958 | 6.476937 | 65 | |

| Female | 3 | 187.188527 | 4.500013 | 38 | |||

| Total | 551.620485 | 103 | |||||

| (Unknown, Source Ad) | Unknown | Home/Private Residence (1) | 3 | 533.427248 | 5.821799 | 101 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Other (3) | 8 | 26.046172 | 2.000000 | 2 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Total | 559.473420 | 103 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over70,District | 130692.097784 | ||||||

| Over70, South | 32111.561935 | ||||||

| (South,Gender) | South(1) | Male(1) | 7 | 14714.295158 | 9.105985 | 2406 | |

| Female (2) | 7 | 17247.234115 | 9.423006 | 2799 | |||

| Total | 31961.529273 | 5205 | |||||

| (South, SourceAd) | South(1) | Home/Private Residence (1) | 4 | 29580.700863 | 9.305313 | 4792 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 4 | 2225.745864 | 9.251395 | 358 | |||

| Other (3) | 2 | 320.023091 | 6.927273 | 55 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Total | 32126.469818 | 5205 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over70, Northern Harbor | 44822.046650 | ||||||

| (Northern Harbour, Gender) | Northern Harbour (2) | Male(1) | 7 | 20773.565966 | 9.957635 | 3352 | |

| Female(2) | 8 | 23927.621456 | 9.284152 | 3931 | |||

| Total | 44701.187422 | 7283 | |||||

| (Northern Harbour, Source Ad) | Northern Harbout | Home/Private Residence (1) | 4 | 41422.992605 | 9.604185 | 6710 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 4 | 3049.111549 | 9.784550 | 492 | |||

| Other (3) | 4 | 466.389961 | 7.604933 | 81 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Total | 44938.494115 | 7283 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over70, North | 15668.195104 | ||||||

| (North, Gender) | North | Male | 7 | 6901.967381 | 9.851752 | 1113 | |

| Female | 8 | 9050.657193 | 10.528292 | 1414 | |||

| Total | 15952.624574 | 2527 | |||||

| (North, Source Ad) | North | Home/Private Residence (1) | 4 | 14779.181823 | 10.256322 | 2337 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 3 | 1031.121664 | 10.030494 | 164 | |||

| Other (3) | 1 | 169.959218 | 9.153838 | 26 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Total | 15980.262705 | 2527 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 70, South Eastern | 18437.143066 | ||||||

| (South Eastern, Gender) | South Eastern | Male | 6 | 7767.242350 | 9.843978 | 1237 | |

| Female | 8 | 10778.677902 | 9.696152 | 1741 | |||

| Total | 18545.920252 | 2978 | |||||

| (South Eastern, Source Ad) | South Eastern | Home/Private Residence (1) | 6 | 15927.026988 | 9.650990 | 2573 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 3 | 2211.483030 | 10.540473 | 346 | |||

| Other (3) | 2 | 372.784988 | 9.578948 | 57 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 8 | 34.289246 | 16.500001 | 2 | |||

| Total | 18545.584252 | 2978 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over70, Western | 18559.234106 | ||||||

| (Western, Gender) | Western | Male | 7 | 8720.229605 | 9.524345 | 1417 | |

| Female | 4 | 10089.835560 | 9.329470 | 1639 | |||

| Total | 18810.065165 | 3056 | |||||

| (Western, Source Ad) | Western | Home/Private Residence (1) | 6 | 16036.719389 | 9.299390 | 2632 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 5 | 2537.928683 | 10.045568 | 395 | |||

| Other (3) | 1 | 198.190740 | 12.035684 | 28 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 1 | ||||||

| Total | 18772.838812 | 3056 |

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over70, Gozo&Comino | 841.396961 | ||||||

| (Gozo&Comino, Gender) | G&C | Male | 2 | 484.147245 | 8.088608 | 79 | |

| Female | 3 | 243.881774 | 8.025018 | 40 | |||

| Total | 728.029019 | 119 | |||||

| (Gozo&Comino, Source Ad) | G&C | Home/Private Residence (1) | 2 | 531.656682 | 9.120484 | 83 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 1 | ||||||

| Other (3) | 2 | 183.888567 | 5.600017 | 35 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Total | 715.545249 | 119 | |||||

| Group No(LEFT) | Group No (Right) | Phase(x) | Min WIC | Gain in WIC | Mean LoS | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over70, Unknown | 252.519962 | ||||||

| (Unknown, Gender) | Unknown | Male | 3 | 173.278569 | 11.222235 | 27 | |

| Female | 1 | 94.360517 | 5.470570 | 17 | |||

| Total | 267.639086 | 44 | |||||

| (Unknown, Source Ad) | Unknown | Home/Private Residence (1) | 3 | 253.940100 | 9.238111 | 42 | |

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Other (3) | 8 | 28.818760 | 4.000000 | 2 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0 | |||

| Total | 282.758860 | 44 |

| (1, Number Of Admissions) | 1 | 8 | 7847.1116 | 186.6491 | 721 | 7847.1116 | ||

| (Gender, Nr of Adm) | Male(1) | 8 | 6797.0617 | 88.6602 | 721 | 3398.5308 | ||

| Female(2) | 8 | 6960.8298 | 97.9847 | 721 | 3480.4149 | |||

| Total | 13757.8914 | 6878.9457 | 968.1658 | |||||

| (Age, Nr of Adm) | New Born (1) | 3 | 2430.8080 | 2.9745 | 667 | 607.7020 | ||

| Under 30(2) | 8 | 5529.8060 | 36.6685 | 721 | 1382.4515 | |||

| Under 70 (3) | 8 | 7111.5218 | 97.7795 | 721 | 1777.8805 | |||

| Over 71 (4) | 8 | 5922.6184 | 49.4494 | 721 | 1480.6546 | |||

| Total | 20994.7541 | 5248.6885 | 2598.4230 | |||||

| (District, Nr of Adm) | South(1) | 8 | 5775.6090 | 41.5312 | 721 | 825.0870 | ||

| Northern Harbour (2) | 8 | 6256.1519 | 59.9944 | 721 | 893.7360 | |||

| North(3) | 8 | 5316.1594 | 27.8488 | 721 | 759.4513 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 8 | 5181.7809 | 25.2441 | 721 | 740.2544 | |||

| Western (5) | 8 | 5280.4273 | 27.7240 | 721 | 754.3468 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 3 | 3044.6887 | 4.2870 | 669 | 434.9555 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 6 | 341.3544 | 1.5000 | 158 | 48.7649 | |||

| Total | 31196.1717 | 4456.5960 | 3390.5156 | |||||

| (SourceAd, Nr of Adm) | Home/Private Residence (1) | 8 | 7818.1469 | 181.1082 | 721 | 1563.6294 | ||

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 3 | 2590.5717 | 3.1640 | 677 | 518.1143 | |||

| Other (3) | 4 | 2210.5691 | 2.6661 | 641 | 442.1138 | |||

| Police Custody (4) | 6 | 145.7583 | 1.2143 | 98 | 29.1517 | |||

| Unknown (5) | 3 | 42.2021 | 1.1905 | 21 | 8.4404 | |||

| Total | 12807.2481 | 2561.4496 | 5285.6619 | |||||

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (SourceAd, Nr of Adm) | 12807.248112 | 0 | 2561.449622 | |||||

| Home/Private Residence (1) | 7818.146859 | 721 | 1563.629372 | |||||

| (Home, Gender) | Home | Male | 8 | 3825.276337 | 14.298197 | 721 | 382.5276337 | |

| Female | 8 | 3840.042543 | 14.511790 | 721 | 384.0042543 | |||

| Total | 7665.318880 | 766.531888 | 797.097484 | |||||

| (Home,Age) | Home | New Born | 5 | 1515.578455 | 1.945993 | 574 | 75.77892275 | |

| Under30 | 8 | 3125.114139 | 8.377254 | 721 | 156.255707 | |||

| Under70 | 8 | 3275.132289 | 9.932039 | 721 | 163.7566145 | |||

| Over 70 | 8 | 3164.530383 | 8.952843 | 721 | 158.2265192 | |||

| Total | 11080.355266 | 554.0177633 | 1009.611609 | |||||

| (Home, Locality) | Home | South(1) | 8 | 2623.259152 | 6.278779 | 721 | 74.95026149 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 8 | 2634.257255 | 6.278779 | 721 | 75.264493 | |||

| North(3) | 8 | 2546.221529 | 5.332871 | 721 | 72.74918654 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 8 | 2517.560067 | 5.040910 | 721 | 71.93028763 | |||

| Western (5) | 8 | 2537.265545 | 5.391123 | 721 | 72.49330129 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 8 | 420.759504 | 1.256021 | 332 | 12.02170011 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 6 | 236.872569 | 1.345865 | 133 | 6.767787686 | |||

| Total | 13516.195621 | 386.1770177 | 1177.452354 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home for the Elderly (2) | 2590.5717 | 721 | 518.1143 | |||||

| (Home for the elderly, Gender) | Home for the elderly | Male | 7 | 680.2011 | 1.4521 | 376 | 68.0201 | |

| Female | 4 | 1509.5300 | 1.8920 | 602 | 150.9530 | |||

| Total | 2189.7310 | 218.9731 | 299.1412 | |||||

| (Home for the elderly,Age) | Home for the elderly | New Born | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |

| Under30 | 1 | 11.3273 | 1.0000 | 4 | 0.5664 | |||

| Under70 | 8 | 121.5060 | 1.1103 | 145 | 6.0753 | |||

| Over 70 | 4 | 2004.0645 | 2.3493 | 647 | 100.2032 | |||

| Total | 2136.8978 | 106.8449 | 411.2695 | |||||

| (Home for the elderly, Locality) | Home for the elderly | South(1) | 8 | 307.0443 | 1.1804 | 316 | 8.7727 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 8 | 400.0539 | 1.2276 | 369 | 11.4301 | |||

| North(3) | 8 | 107.1798 | 1.0909 | 154 | 3.0623 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 8 | 226.8566 | 1.1502 | 273 | 6.4816 | |||

| Western (5) | 8 | 254.9713 | 1.1498 | 327 | 7.2849 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 1 | bad wic | ||||||

| Unknown (7) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other (3) | 2210.5691 | 442.1138 | ||||||

| (Other, Gender) | Other | Male | 7 | 989.2221 | 1.6151 | 465 | 98.9222 | |

| Female | 8 | 653.6929 | 1.4282 | 376 | 65.3693 | |||

| Total | 1642.9149 | 164.2915 | 277.8223 | |||||

| (Other,Age) | Other | New Born | 8 | 457.0267 | 1.3175 | 315 | 22.8513 | |

| Under30 | 8 | 81.0688 | 1.0792 | 101 | 4.0534 | |||

| Under70 | 8 | 540.1501 | 1.3188 | 367 | 27.0075 | |||

| Over 70 | 8 | 306.4893 | 1.2727 | 220 | 15.3245 | |||

| Total | 1384.7350 | 69.2367 | 372.8771 | |||||

| (Other, Locality) | Other | South(1) | 8 | 163.8176 | 1.1216 | 222 | 4.6805 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 8 | 365.7543 | 1.2694 | 271 | 10.4501 | |||

| North(3) | 8 | 126.2427 | 1.1154 | 156 | 3.6069 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 8 | 172.8283 | 1.1315 | 213 | 4.9380 | |||

| Western (5) | 8 | 107.5059 | 1.0933 | 150 | 3.0716 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 8 | 90.2080 | 1.0900 | 100 | 2.5774 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 1 | 16.3980 | 1.1667 | 6 | 0.4685 | |||

| Total | 1042.7548 | 29.7930 | 412.3208 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Police Custody (4) | 145.7583 | 0 | 29.1517 | |||||

| (Police Custody, Gender) | Police Custody | Male | 6 | 73.9991 | 1.1148 | 61 | 7.3999 | |

| Female | 3 | 35.2291 | 1.0455 | 22 | 3.5229 | |||

| Total | 109.2281 | 10.9228 | 18.2289 | |||||

| (Police Custody,Age) | Police Custody | New Born | 1 | bad wic | ||||

| Under30 | 5 | 48.9482 | 1.0476 | 42 | 2.4474 | |||

| Under70 | 6 | 45.1786 | 1.0222 | 45 | 2.2589 | |||

| Over 70 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Total | 94.1268 | |||||||

| (Police Custody, Locality) | Police Custody | South(1) | 5 | 52.8416 | 1.0714 | 42 | 1.5098 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 1 | 16.3980 | 1.1667 | 6 | 0.4685 | |||

| North(3) | 5 | 45.3066 | 1.0645 | 31 | 1.2945 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Western (5) | 1 | 11.3273 | 1.0000 | 4 | 0.3236 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 6 | 24.1800 | 1.0000 | 2 | 0.6909 | |||

| Total | 150.0535 | 4.2872 | 24.8644 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unknown (5) | 42.2021 | 0 | 8.4404 | |||||

| (Unknown, Gender) | Unknown | Male | 2 | 33.3447 | 1.2000 | 15 | 3.3345 | |

| Female | 1 | 12.9675 | 1.3333 | 3 | 1.2968 | |||

| Total | 46.3123 | 4.6312 | 3.8092 | |||||

| (Unknown,Age) | Unknown | New Born | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |

| Under30 | 1 | 16.4498 | 1.0000 | 7 | 0.8225 | |||

| Under70 | 1 | 26.3356 | 1.0909 | 11 | 1.3168 | |||

| Over 70 | 1 | 11.2414 | 1.0000 | 3 | 0.5621 | |||

| Total | 54.0269 | 2.7013 | 5.7391 | |||||

| (Unknown, Locality) | Unknown | South(1) | 1 | 11.3273 | 1.0000 | 4 | 0.3236 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 1 | 14.5482 | 1.0000 | 6 | 0.4157 | |||

| North(3) | 1 | 11.2414 | 1.0000 | 3 | 0.3212 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 1 | 11.3280 | 1.0000 | 4 | 0.3237 | |||

| Western (5) | 1 | 11.3280 | 1.0000 | 4 | 0.3237 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 1 | bad wic | ||||||

| Total | 59.7728 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South | 2623.2592 | 74.9503 | ||||||

| (South,Gender) | South | Male | 8 | 1728.9181 | 2.9404 | 721 | 24.6988 | |

| Female | 8 | 1680.8043 | 2.9875 | 721 | 24.0115 | |||

| Total | 3409.7224 | 48.7103 | 26.2399 | |||||

| (South,Age) | South | New Born | 8 | 149.4513 | 1.1057 | 227 | 1.0675 | |

| Under30 | 8 | 1098.8306 | 1.7511 | 699 | 7.8488 | |||

| Under70 | 8 | 963.7893 | 1.9653 | 721 | 6.8842 | |||

| Over70 | 8 | 1010.9900 | 1.9194 | 720 | 7.2214 | |||

| Total | 3223.0612 | 23.0219 | 2600.2373 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Harbour (2) | 2634.2573 | 75.2645 | ||||||

| (Northern Harbour,Gender) | Northern Harbour | Male | 8 | 1711.0654 | 3.1248 | 721 | 24.4438 | |

| Female | 8 | 1688.6759 | 3.1526 | 721 | 24.1239 | |||

| Total | 3399.7413 | 48.5677 | 26.6968 | |||||

| (Northern Harbour,Age) | Northern Harbour | New Born | 8 | 196.5910 | 1.1268 | 276 | 1.4042 | |

| Under30 | 8 | 1042.4523 | 1.8872 | 718 | 7.4461 | |||

| Under70 | 8 | 931.3925 | 1.9931 | 721 | 6.6528 | |||

| Over70 | 8 | 952.7085 | 1.9750 | 721 | 6.8051 | |||

| Total | 3123.1444 | 22.3082 | 52.9563 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Eastern | 2517.5601 | 71.9303 | ||||||

| (South Eastern,Gender) | South Eastern | Male | 8 | 1764.2662 | 2.4603 | 717 | 25.2038 | |

| Female | 8 | 1753.4744 | 2.6184 | 718 | 25.0496 | |||

| Total | 3517.7405 | 25.7832 | 46.1471 | |||||

| (South Eastern,Age) | South Eastern | New Born | 8 | 102.7033 | 1.0878 | 148 | 0.7336 | |

| Under30 | 8 | 1020.2853 | 1.5160 | 657 | 7.2878 | |||

| Under70 | 8 | 1089.5342 | 1.8187 | 717 | 7.7824 | |||

| Over70 | 8 | 1109.7852 | 1.6997 | 696 | 7.9270 | |||

| Total | 3322.3080 | 23.7308 | 48.1995 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western | 2537.2655 | 72.4933 | ||||||

| (Western,Gender) | Western | Male | 8 | 1754.0134 | 2.7060 | 721 | 25.0573 | |

| Female | 8 | 1756.8674 | 2.6964 | 718 | 25.0981 | |||

| Total | 3510.8808 | 50.1554 | 22.3379 | |||||

| (Western,Age) | Western | New Born | 8 | 92.8663 | 1.0628 | 191 | 0.6633 | |

| Under30 | 8 | 1099.7387 | 1.6385 | 686 | 7.8553 | |||

| Under70 | 8 | 1039.6177 | 1.8889 | 720 | 7.4258 | |||

| Over70 | 8 | 1116.6005 | 1.7094 | 702 | 7.9757 | |||

| Total | 3348.8233 | 23.9202 | 48.5731 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | 2546.2215 | 72.7492 | ||||||

| (North,Gender) | North | Male | 8 | 1751.3926 | 2.6147 | 719 | 25.0199 | |

| Female | 8 | 1718.5607 | 2.7254 | 721 | 24.5509 | |||

| Total | 3469.9533 | 49.5708 | 23.1784 | |||||

| (North,Age) | North | New Born | 8 | 101.3088 | 1.0798 | 163 | 0.7236 | |

| Under30 | 8 | 1091.1134 | 1.7032 | 684 | 7.7937 | |||

| Under70 | 8 | 1034.7502 | 1.8898 | 717 | 7.3911 | |||

| Over70 | 8 | 1095.0329 | 1.6798 | 684 | 7.8217 | |||

| Total | 3322.2052 | 23.7300 | 49.0191 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G&C | 420.7595 | 12.0217 | ||||||

| (G&C,Gender) | G&C | Male | 8 | 135.3123 | 1.0935 | 214 | 1.9330 | |

| Female | 8 | 115.9542 | 1.0958 | 167 | 1.6565 | |||

| Total | 251.2665 | 3.5895 | 8.4322 | |||||

| (G&C,Age) | G&C | New Born | 2 | 20.2517 | 1.0000 | 9 | 0.1447 | |

| Under30 | 8 | 80.2189 | 1.0714 | 112 | 0.5730 | |||

| Under70 | 8 | 128.8773 | 1.1016 | 187 | 0.9206 | |||

| Over70 | 8 | 50.0143 | 1.0250 | 80 | 0.3572 | |||

| Total | 279.3622 | 1.9954 | 10.0263 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unkown | 236.8726 | 6.7678 | ||||||

| (Unkown,Gender) | Unkown | Male | 6 | 122.7512 | 1.8889 | 90 | 1.7536 | |

| Female | 6 | 78.5390 | 1.1250 | 64 | 1.1220 | |||

| Total | 201.2902 | 2.8756 | 3.8922 | |||||

| (Unkown,Age) | Unkown | New Born | 1 | 14.5482 | 1.0000 | 6 | 0.1039 | |

| Under30 | 7 | 41.4024 | 1.0370 | 54 | 0.2957 | |||

| Under70 | 7 | 72.0095 | 1.0789 | 76 | 0.5144 | |||

| Over70 | 4 | 45.3867 | 1.0606 | 33 | 0.3242 | |||

| Total | . | 173.3468 | 1.2382 | 5.5296 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under30 | 11.3273 | 0.5664 | ||||||

| (Under30, Gender) | Under30 | Male | 8 | 20.2522 | 1.0000 | 2 | 0.5063 | |

| Female | 8 | 20.2522 | 1.0000 | 2 | 0.5063 | |||

| Total | 40.5044 | 1.0126 | -0.4462 | |||||

| (Under 30, District) | Under30 | South(1) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 8 | 20.2522 | 1.0000 | 2 | 0.1447 | |||

| North(3) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 1 | 0.0000 | bad wic | |||||

| Western (5) | 1 | 0.0000 | bad wic | |||||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Total | 20.2522 | 0.1447 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under70 | 121.5060 | 6.0753 | ||||||

| (Under70, Gender) | Under70 | Male | 7 | 67.1647 | 1.0676 | 74 | 1.6791 | |

| Female | 8 | 50.0143 | 1.0250 | 80 | 1.2504 | |||

| Total | 117.1790 | 2.9295 | 3.1458 | |||||

| (Under70, District) | Under70 | South(1) | 8 | 45.9057 | 1.0161 | 62 | 0.3279 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 5 | 37.8572 | 1.0000 | 34 | 0.2704 | |||

| North(3) | 2 | 25.3496 | 1.0000 | 14 | 0.1811 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 3 | 29.0342 | 1.0000 | 18 | 0.2074 | |||

| Western (5) | 5 | 37.2807 | 1.0000 | 32 | 0.2663 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | ||||

| Unknown (7) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | ||||

| Total | 175.4274 | 1.2531 | 4.8222 | |||||

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over70 | 20.2522 | 100.2032 | ||||||

| (Over70, Gender) | Over70 | Male | 8 | 549.3527 | 1.3798 | 337 | 13.7338 | |

| Female | 5 | 1384.2249 | 1.7881 | 590 | 34.6056 | |||

| Total | 1933.5776 | 48.3394 | 51.8638 | |||||

| (Over70, District) | Over70 | South(1) | 8 | 177.9781 | 1.1111 | 279 | 1.2713 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 8 | 322.7247 | 1.1880 | 351 | 2.3052 | |||

| North(3) | 8 | 76.7523 | 1.0548 | 146 | 0.5482 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 8 | 193.0263 | 1.1303 | 261 | 1.3788 | |||

| Western (5) | 8 | 198.8374 | 1.1173 | 307 | 1.4203 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 1 | 0.0000 | bad wic | |||||

| Unknown (7) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Total | 969.3187 | 6.9237 | ||||||

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South | 163.8176 | 4.6805 | ||||||

| (South,Gender) | South | Male | 8 | 75.5479 | 1.0513 | 156 | 1.0793 | |

| Female | 8 | 55.6362 | 1.0366 | 82 | 0.7948 | |||

| Total | 131.1840 | 1.8741 | 2.8064 | |||||

| (South,Age) | South | New Born | 7 | 62.1005 | 1.0571 | 70 | 0.4436 | |

| Under30 | 5 | 37.8572 | 1.0000 | 34 | 0.2704 | |||

| Under70 | 8 | 43.3844 | 1.0116 | 86 | 0.3099 | |||

| Over70 | 8 | 47.0520 | 1.0189 | 53 | 0.3361 | |||

| Total | 190.3941 | 1.3600 | 162.4576 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NorthernHarbour | 365.7543 | 10.4501 | ||||||

| (Northern Harbour,Gender) | Northern Harbour | Male | 8 | 147.9584 | 1.1317 | 167 | 2.1137 | |

| Female | 8 | 108.1670 | 1.0993 | 141 | 1.5452 | |||

| Total | 256.1254 | 3.6589 | 6.7912 | |||||

| (Northern Harbour,Age) | Northern Harbour | New Born | 8 | 68.8909 | 1.0508 | 118 | 0.4921 | |

| Under30 | 3 | 32.9587 | 1.0000 | 32 | 0.2354 | |||

| Under70 | 8 | 69.6084 | 1.0541 | 111 | 0.4972 | |||

| Over70 | 8 | 56.1060 | 1.0390 | 77 | 0.4008 | |||

| Total | 227.5640 | 1.6255 | 8.8247 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Eastern | 172.8283 | 4.9380 | ||||||

| (South Eastern,Gender) | South Eastern | Male | 8 | 63.7468 | 1.0439 | 114 | 0.9107 | |

| Female | 8 | 63.4185 | 1.0427 | 117 | 0.9060 | |||

| Total | 127.1653 | 1.3032 | 3.6348 | |||||

| (South Eastern,Age) | South Eastern | New Born | 6 | 55.6113 | 1.0577 | 52 | 0.3972 | |

| Under30 | 2 | 26.5643 | 1.0000 | 15 | 0.1897 | |||

| Under70 | 8 | 58.3950 | 1.0360 | 111 | 0.4171 | |||

| Over70 | 7 | 51.4024 | 1.0370 | 54 | 0.3672 | |||

| Total | 191.9731 | 1.3712 | 3.5667 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western | 107.5059 | 3.0716 | ||||||

| (Western,Gender) | Western | Male | 8 | 59.5696 | 1.0400 | 100 | 0.8510 | |

| Female | 7 | 46.1980 | 1.0169 | 59 | 0.6600 | |||

| Total | 105.7676 | 1.5110 | 1.5606 | |||||

| (Western,Age) | Western | New Born | 8 | 51.2051 | 1.0294 | 68 | 0.3658 | |

| Under30 | 1 | 11.3273 | 1.0000 | 4 | 0.0809 | |||

| Under70 | 5 | 48.4395 | 1.0333 | 60 | 0.3460 | |||

| Over70 | 4 | 38.6121 | 1.0370 | 27 | 0.2758 | |||

| Total | 149.5840 | 1.0685 | 2.0031 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | 126.2427 | 3.6069 | ||||||

| (North,Gender) | North | Male | 8 | 42.6306 | 1.0108 | 93 | 0.6090 | |

| Female | 8 | 56.1060 | 1.0390 | 77 | 0.8015 | |||

| Total | 98.7366 | 1.4105 | 2.1964 | |||||

| (North,Age) | North | New Born | 8 | 76.4305 | 1.0946 | 74 | 0.5459 | |

| Under30 | 3 | 29.0342 | 1.0000 | 18 | 0.2074 | |||

| Under70 | 6 | 45.8395 | 1.0204 | 49 | 0.3274 | |||

| Over70 | 4 | 33.9331 | 1.0000 | 25 | 0.2424 | |||

| Total | 185.2373 | 1.3231 | 2.2838 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G&C | 90.2080 | 2.5774 | ||||||

| (G&C,Gender) | G&C | Male | 8 | 62.1211 | 1.0556 | 72 | 0.8874 | |

| Female | 4 | 41.3277 | 1.0313 | 32 | 0.5904 | |||

| Total | 103.4488 | 1.4778 | 1.0995 | |||||

| (G&C,Age) | G&C | New Born | 2 | 21.9630 | 1.0000 | 11 | 0.1569 | |

| Under30 | 2 | 21.9630 | 1.0000 | 11 | 0.1569 | |||

| Under70 | 7 | 40.5254 | 1.0000 | 52 | 0.2895 | |||

| Over70 | 5 | 38.1635 | 1.0000 | 35 | 0.2726 | |||

| Total | 122.6148 | 0.8758 | 1.7016 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unkown | 16.3980 | 0.4685 | ||||||

| (Unkown,Gender) | Unkown | Male | 1 | 13.1124 | 1.2500 | 4 | 0.1873 | |

| Female | 8 | 20.2522 | 1.0000 | 2 | 0.2893 | |||

| Total | 33.3646 | 0.4766 | -0.0081 | |||||

| (Unkown,Age) | Unkown | New Born | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |

| Under30 | 1 | 11.3273 | 1.0000 | 4 | 0.0809 | |||

| Under70 | 1 | 0.0000 | bad wic | |||||

| Over70 | 8 | 20.2522 | 1.0000 | 2 | 0.1447 | |||

| Total | . | 31.5795 | 0.2256 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South | 52.8416 | 1.5098 | ||||||

| (South,Gender) | South | Male | 5 | 51.3721 | 1.0789 | 38 | 0.7339 | |

| Female | 1 | 11.3273 | 1.0000 | 4 | 0.1618 | |||

| Total | 62.6994 | 0.8957 | 0.6141 | |||||

| (South,Age) | South | New Born | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |

| Under30 | 3 | 27.7219 | 1.0000 | 23 | 0.1980 | |||

| Under70 | 4 | 35.9632 | 1.0000 | 10 | 0.2569 | |||

| Over70 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Total | 63.6851 | 0.4549 | 52.3868 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NorthernHarbour | 16.3980 | 0.4685 | ||||||

| (Northern Harbour,Gender) | Northern Harbour | Male | 1 | 12.7720 | 1.0000 | 5 | 0.1825 | |

| Female | 8 | 20.2522 | 1.0000 | 2 | 0.2893 | |||

| Total | 33.0242 | 0.4718 | -0.0033 | |||||

| (Northern Harbour,Age) | Northern Harbour | New Born | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |

| Under30 | 1 | 11.3273 | 1.0000 | 4 | 0.0809 | |||

| Under70 | 1 | 11.2414 | 1.0000 | 3 | 0.0803 | |||

| Over70 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Total | 22.5687 | 0.1612 | 0.3073 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western | 11.3273 | 0.3236 | ||||||

| (Western,Gender) | Western | Male | 1 | 11.2414 | 1.0000 | 3 | 0.1606 | |

| Female | 1 | 0.0000 | BAD WIC | |||||

| Total | 11.2414 | 0.1606 | ||||||

| (Western,Age) | Western | New Born | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |

| Under30 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Under70 | 1 | 11.3273 | 1.0000 | 4 | 0.0809 | |||

| Over70 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Total | 11.3273 | 0.0809 | 0.2427 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | 45.3066 | 1.2945 | ||||||

| (North,Gender) | North | Male | 3 | 29.0342 | 1.0000 | 18 | 0.4148 | |

| Female | 2 | 26.5643 | 1.0000 | 15 | 0.3795 | |||

| Total | 55.5985 | 0.7943 | 0.5002 | |||||

| (North,Age) | North | New Born | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |

| Under30 | 3 | 32.9587 | 1.0000 | 23 | 0.2354 | |||

| Under70 | 2 | 21.0108 | 1.0000 | 10 | 0.1501 | |||

| Over70 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Total | 53.9695 | 0.3855 | 0.9090 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unkown | 24.1800 | 0.6909 | ||||||

| (Unkown,Gender) | Unkown | Male | 1 | 0.0000 | BAD WIC | |||

| Female | 1 | 0.0000 | BAD WIC | |||||

| Total | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||||

| (Unkown,Age) | Unkown | New Born | 1 | 0.0000 | BAD WIC | |||

| Under30 | 1 | 0.0000 | BAD WIC | |||||

| Under70 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Over70 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Total | . | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under30 | 16.4498 | 0.8225 | ||||||

| (Under30, Gender) | Under30 | Male | 1 | 12.7720 | 1.0000 | 5 | 0.3193 | |

| Female | 8 | 20.2522 | 1.0000 | 2 | 0.5063 | |||

| Total | 33.0242 | 0.8256 | -0.0031 | |||||

| (Under 30, District) | Under30 | South(1) | 8 | 20.2522 | 1.0000 | 2 | 0.1447 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 1 | 0.0000 | BAD WIC | |||||

| North(3) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 1 | 0.0000 | BAD WIC | |||||

| Western (5) | 1 | 0.0000 | BAD WIC | |||||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 1 | 0.0000 | BAD WIC | |||||

| Total | 20.2522 | 0.1447 | ||||||

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under70 | 26.3356 | 1.3168 | ||||||

| (Under70, Gender) | Under70 | Male | 2 | 21.0108 | 1.0000 | 10 | 0.5253 | |

| Female | 1 | 0.0000 | bad wic | |||||

| Total | 21.0108 | 0.5253 | ||||||

| (Under70, District) | Under70 | South(1) | 8 | 20.2522 | 1.0000 | 2 | 0.1447 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 1 | 12.7720 | 1.0000 | 5 | 0.0912 | |||

| North(3) | 8 | 20.2522 | 1.0000 | 2 | 0.1447 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 1 | 0.0000 | BAD WIC | |||||

| Western (5) | 8 | 20.2522 | 1.0000 | 2 | 0.1447 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Total | 73.5286 | 0.5252 |

| Group Number (Left) | Group Number (Right) | Phase | WIC | Mean | Number of Records | Average WIC | WIC Gain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over70 | 11.2414 | 0.5621 | ||||||

| (Over70, Gender) | Over70 | Male | 8 | 20.2522 | 1.0000 | 2 | 0.5063 | |

| Female | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Total | 20.2522 | 0.5063 | 0.0558 | |||||

| (Over70, District) | Over70 | South(1) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |

| Northern Harbour (2) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| North(3) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| South Eastern (4) | 8 | 20.2522 | 1.0000 | 2 | 0.1447 | |||

| Western (5) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Gozo & Comino (6) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Unknown (7) | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |||

| Total | 20.2522 | 0.1447 | 0.4174 |

| Group | No. of Patients |

Actual Mean LOS |

Predicted Mean LOS |

Forecast Error |

Squared Error |

Absolute Error |

Percentage Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NewBorn, Male,Private Residence | 395 | 5.73 | 5.03 | -0.70 | 0.49 | 0.70 | 12.22 |

| NewBorn, Male,Other | 112 | 18.98 | 17.35 | -1.63 | 2.66 | 1.63 | 8.59 |

| NewBorn, Female | 368 | 7.96 | 8.49 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.53 | 6.66 |

| Under30,Male | 3361 | 4.46 | 4.16 | -0.30 | 0.09 | 0.30 | 6.73 |

| Under30, Female | 4430 | 4.00 | 3.86 | -0.14 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 3.50 |

| Under70, South | 3403 | 6.35 | 6.49 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 2.20 |

| Under 70, Northern Harbour | 4830 | 6.22 | 6.25 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.48 |

| Under70, South Eastern | 2171 | 5.99 | 6.20 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 3.51 |

| Under70, Western | 1973 | 5.90 | 6.23 | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 5.59 |

| Under70, North | 2294 | 6.38 | 5.93 | -0.45 | 0.20 | 0.45 | 7.05 |

| Under70,Gozo&Comino, Private Residence |

133 | 8.67 | 7.45 | -1.22 | 1.49 | 1.22 | 14.07 |

| Under70, Gozo&Comino. Other | 19 | 13.37 | 13.42 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.37 |

| Under70,Unknown | 173 | 4.73 | 5.75 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 21.56 |

| Over71,South,Male | 11145 | 9.02 | 9.11 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 1.00 |

| Over71,South,Female | 15101 | 11.18 | 9.42 | -1.76 | 3.10 | 1.76 | 15.74 |

| Over71, Northern Harbour,Male | 14123 | 11.43 | 9.96 | -1.47 | 2.16 | 1.47 | 12.86 |

| Over71, Northern Harbour, Female | 20974 | 10.61 | 9.28 | -1.33 | 1.77 | 1.33 | 12.54 |

| Over71, South Eastern | 12593 | 9.80 | 9.49 | -0.31 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 3.16 |

| Over71, Western | 14788 | 10.07 | 9.87 | -0.20 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 1.99 |

| Over71, North | 14416 | 9.50 | 9.34 | -0.16 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 1.68 |

| Over71, Gozo&Comino, Male | 352 | 12.14 | 8.09 | -4.05 | 16.40 | 4.05 | 33.36 |

| Over71, Gozo&Comino, Female | 259 | 17.27 | 8.03 | -9.24 | 85.38 | 9.24 | 53.50 |

| Over71,Unknown | 500 | 5.62 | 6.48 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.86 | 15.30 |

| Group | No. of Records |

Actual Mean Adm. |

Predicted Mean Adm. |

Forecast Error |

Squared Error |

Absolute Error |

Percentage Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private Residence, Northern Harbour Under 30 |

686 | 3.42 | 1.89 | -1.53 | 2.3409 | 1.53 | 44.74 |

| Private Residence, Gozo& Comino, Over71 |

34 | 1 | 1.03 | 0.03 | 0.0009 | 0.03 | 3.00 |

| Elderly Home, Under 70, North | 13 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Elderly Home, Over 71, Males |

269 | 1.08 | 1.38 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.30 | 27.78 |

| Other, South, New Borns | 43 | 1.02 | 1.06 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 3.92 |

| Other, Western, Females | 99 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Police Custody, South Eastern Under 30 |

38 | 1.11 | 1.00 | -1.27 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 9.91 |

| Police Custody, North, Under 70 | 1 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Unknown, Under 70 | 0 | - | 1.09 | - | - | - | - |

| Unknown, Over 71, Male | 0 | - | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| MSE | RMSE | MAD | BIAS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOS | Personal Characteristics | 1.15 | 1.07 | 0.74 | -0.69 |

| Admissions | Personal Characteristics | 1.38 | 1.17 | 0.96 | -0.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).