Submitted:

16 February 2023

Posted:

17 February 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Results

1. Data analyses dispute all 3 supporting evidences of Theory of H. pylori

2. Alternative interpretations for the 3 observations explainable by H. pylori

3. Applying historical definition of ‘etiological factor’ or ‘causality’ to H. pylori

4. Existing data presented a controversial view on the role of H. pylori

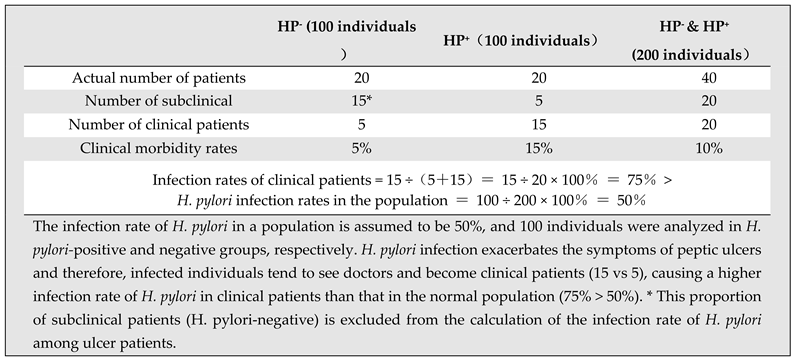

5. Epidemiological studies dispute the causal role of H. pylori in peptic ulcers

6. Characteristics of peptic ulcers dispute the causal role of H. pylori in this disease

7. Historical observations/phenomenon dispute the role of H. pylori in peptic ulcers

Discussion

Conclusion

Supplemental Materials

Ethics Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflict of Interest

References

- A. Damon, A.P. Polednak, Constitution, genetics, and body form in peptic ulcer: A review, J. Chronic Dis. 20 (1967) 787–802. [CrossRef]

- S. Fatović-Ferenčić, M. Banić, No acid, no ulcer: Dragutin (Carl) Schwarz (1868-1917), the man ahead of his time, Dig. Dis. 29 (2011) 507–10. [CrossRef]

- G. von Bergmann, Ulcus duodeni und vegetatives nerve system, Berl Klin Wchnscher. 50 (1913) 2374.

- H.M. Wolowitz, Oral involvement in peptic ulcer, J. Consult. Psychol. 31 (1967) 418–419. [CrossRef]

- H. Selye, The physiology and pathology of exposure to stress, Acta, Oxford, England, 1950.

- S.X.M. Dong, C.C.Y. Chang, K.J. Rowe, A collection of the etiological theories, characteristics, and observations/phenomena of peptic ulcers in existing data, Data Br. 19 (2018) 1058–1067. [CrossRef]

- H. Kuang, Peptic Ulcer Diseases, People’s Medical Publishing House, Beijing, 1990.

- M. Susser, Z. Stein, Civilization and Peptic Ulcer, Lancet. 279 (1962) 116–119. [CrossRef]

- A. Sonnenberg, I.H. Wasserman, S.J. Jacobsen, Monthly variation of hospital admission and mortality of peptic ulcer disease: A reappraisal of ulcer periodicity, Gastroenterology. 103 (1992) 1192–1198. [CrossRef]

- C. Ciacci, G. Mazzacca, The history of Helicobacter pylori: A reflection on the relationship between the medical community and industry, Dig. Liver Dis. 38 (2006) 778–780. [CrossRef]

- B.J. Marshall, Peptic Ulcer: An Infectious Disease?, Hosp. Pract. 22 (1987) 87–96. [CrossRef]

- M. Hobsley, F.I. Tovey, K.D. Bardhan, J. Holton, Head to Head: Does Helicobacter pylori really cause duodenal ulcers? No, BMJ. 339 (2009) b2788. [CrossRef]

- W.L. Peterson, Review article: Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease, N Engl J Med. 324 (1991) 1043–1048. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Veldhuyzen van Zanten, P.M. Sherman, Helicobacter pylori infection as a cause of gastritis, duodenal ulcer, gastric cancer and nonulcer dyspepsia: a systematic overview, CMAJ. 150 (1994) 177–85. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8287340.

- J.H. Walsh, W.L. Peterson, The Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection in the Management of Peptic Ulcer Disease, N. Engl. J. Med. 333 (1995) 984–991. [CrossRef]

- D.Y. Graham, Helicobacter pylori: its epidemiology and its role in duodenal ulcer disease, J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6 (1991) 105–13. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1912414.

- H. Li, I. KALIES, B. MELLGÅRD, H.F. Helander, A Rat Model of Chronic Helicobacter pylori Infection: Studies of Epithelial Cell Turnover and Gastric Ulcer Healing, Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 33 (1998) 370–378. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Konturek, W. Bielanski, M. Plonka, T. Pawlik, J. Pepera, P.C. Konturek, J. Czarnecki, A. Penar, W. Jedrychowski, Helicobacter pylori, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and smoking in risk pattern of gastroduodenal ulcers, Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 38 (2003) 923–930. [CrossRef]

- B.J. Marshall, C.S. Goodwin, J.R. Warren, R. Murray, E.D. Blincow, S.J. Blackbourn, M. Phillips, T.E. Waters, C.R. Sanderson, Prospective double-blind trial of duodenal ulcer relapse after eradication of Campylobacter pylori., Lancet (London, England). 2 (1988) 1437–42. [CrossRef]

- E.J. Rauws, G.N.J. Tytgat, Helicobacter pylori in duodenal and gastric ulcer disease, Baillière’s Clin. Gastroenterol. 9 (1995) 529–547. [CrossRef]

- V.P.Y. Tan, B.C.Y. Wong, Helicobacter pylori and gastritis: Untangling a complex relationship 27 years on, J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 26 (2011) 42–45. [CrossRef]

- C. Musumba, D.M. Pritchard, M. Pirmohamed, Review article: cellular and molecular mechanisms of NSAID-induced peptic ulcers, Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 30 (2009) 517–531. [CrossRef]

- J.P. Gisbert, X. Calvet, Review article: Helicobacter pylori-negative duodenal ulcer disease, Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 30 (2009) 791–815. [CrossRef]

- J. Carton, R. Daly, P. Ramani, Clinical Pathology, Oxford University Press, 2007.

- C. Holcombe, Helicobacter pylori: the African enigma., Gut. 33 (1992) 429–431. [CrossRef]

- S.X.M. Dong, C.C.Y. Chang, Philosophical Principles of Life Science, Wunan Culture Enterprise, Taipei, 2012.

- S.X.M. Dong, The hyperplasia and hypertrophy of gastrin and parietal cells induced by chronic stress explain the pathogenesis of duodenal ulcer, J. Ment. Heal. Clin. Psychol. 6 (2022) 1–12.

- S.X.M. Dong, A Novel Pathological Model Explains the Pathogenesis of Gastric Ulcer, J. Ment. Heal. Clin. Psychol. 6 (2022).

- S.X.M. Dong, Painting a complete picture of peptic ulcers, J. Clin. Transl. Res. 8 (2022).

- S.X.M. Dong, Novel data analysese explain the birth-cohort phenomenon of peptic ulcers, J. Clin. Transl. Res. 8 (2022).

- S.X.M. Dong, Novel data analyses explain the seasonal variations of peptic ulcers, J. Clin. Transl. Res. 8 (2022).

- V. Taskin, I. Gurer, E. Ozyilkan, M. Sare, F. Hilmioglu, Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on peptic ulcer disease complicated with outlet obstruction, Helicobacter. 5 (2000) 38–40. [CrossRef]

- J.W. Freston, Role of proton pump inhibitors in non-H. pylori-related ulcers, Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 15 (2001) 2–5. [CrossRef]

- J.G. Penston, Helicobacter pylori eradication–understandable caution but no excuse for inertia, Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 8 (1994) 369–389. [CrossRef]

- T.J. Borody, P. Cole, S. Noonan, A. Morgan, J. Lenne, L. Hyland, S. Brandl, E.G. Borody, L.L. George, Recurrence of duodenal ulcer and Campylobacter pylori infection after eradication., Med. J. Aust. 151 (1989) 431–435. [CrossRef]

- A. V Cutler, T.T. Schubert, Long-term Helicobacter pylori recurrence after successful eradication with triple therapy., Am. J. Gastroenterol. 88 (1993) 1359–1361.

- T. Okimoto, K. Murakami, R. Sato, H. Miyajima, M. Nasu, J. Kagawa, M. Kodama, T. Fujioka, Is the recurrence of Helicobacter pylori infection after eradication therapy resultant from recrudescence or reinfection, in Japan., Helicobacter. 8 (2003) 186–91. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12752730.

- P. Katz, Once an ulcer, always an ulcer?, Am. J. Gastroenterol. 89 (1994) 808–809. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8172163.

- J.P. Miller, E.B. Faragher, Relapse of duodenal ulcer: does it matter which drug is used in initial treatment?, BMJ. 293 (1986) 1117–1118. [CrossRef]

- E.M. Bateson, Duodenal Ulcer-Does it Exist in Australian Aborigines?, Aust. N. Z. J. Med. 6 (1976) 545–547. [CrossRef]

- F.G. Hesse, Incidence of cholecystitis and other diseases among Pima Indians of Southern Arizona, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 170 (1959) 1789–90. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13672772.

- M.L. Sievers, J.R. Marquis, Duodenal Ulcer among Southwestern American Indians, Gastroenterology. 42 (1962) 566–569. [CrossRef]

- M. Moshkowitz, F.M. Konikoff, N. Arber, Y. Peled, M. Santo, Y. Bujanover, T. Gilat, Seasonal variation in the frequency of Helicobacter pylori infection: a possible cause of the seasonal occurrence of peptic ulcer disease, Am. J. Gastroenterol. 89 (1994) 731–3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8172147.

- V. Savarino, G.S. Mela, P. Zentilin, G. Lapertosa, P. Cutela, M.R. Mele, C. Mansi, E. Dallorto, A. Vassallo, G. Celle, Are Duodenal Ulcer Seasonal Fluctuations Paralleled by Seasonal Changes in 24-Hour Gastric Acidity and Helicobacter Pylori Infection?, J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 22 (1996) 178–181. [CrossRef]

- C. Raschka, W. Schorr, H.J. Koch, Is There Seasonal Periodicity in the Prevalence of Helicobacter Pylori?, Chronobiol. Int. 16 (1999) 811–819. [CrossRef]

- A.B. Hill, The Environment and Disease: Association or Causation?, Proc. R. Soc. Med. 58 (1965) 295–300. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0079742108605629.

- R. van Reekum, D.L. Streiner, D.K. Conn, Applying Bradford Hill’s Criteria for Causation to Neuropsychiatry, J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 13 (2001) 318–325. [CrossRef]

- K.M. Fedak, A. Bernal, Z.A. Capshaw, S. Gross, Applying the Bradford Hill criteria in the 21st century: how data integration has changed causal inference in molecular epidemiology, Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 12 (2015) 14. [CrossRef]

- H.R. Wulff, Rational Diagnosis and Treatment, J. Med. Philos. 11 (1986) 123–134. [CrossRef]

- L.N. Ross, The doctrine of specific etiology, Biol. Philos. 33 (2018) 37. [CrossRef]

- M. Susser, What is a Cause and How Do We Know One? A Grammar for Pragmatic Epidemiology, Am. J. Epidemiol. 133 (1991) 635–648. [CrossRef]

- M.P. Jones, The role of psychosocial factors in peptic ulcer disease: Beyond Helicobacter pylori and NSAIDs, J. Psychosom. Res. 60 (2006) 407–412. [CrossRef]

- S. Kato, Y. Nishino, K. Ozawa, M. Konno, S.I. Maisawa, S. Toyoda, H. Tajiri, S. Ida, T. Fujisawa, K. Iinuma, The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Japanese children with gastritis or peptic ulcer disease, J. Gastroenterol. 39 (2004) 734–738. [CrossRef]

- K. Iijima, T. Kanno, T. Koike, T. Shimosegawa, Helicobacter pylori-negative, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug: Negative idiopathic ulcers in Asia, World J. Gastroenterol. 20 (2014) 706. [CrossRef]

- M. Witthöft, Etiology/Pathogenesis, in: M.D. Gellman, J.R. Turner (Eds.), Encycl. Behav. Med., Springer, New York, NY, 2013. [CrossRef]

- C.O. Record, P.C. Rubin, Controversies in Management: Helicobacter pylori is not the causative agent, BMJ. 309 (1994) 1571–1572. [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia, Barry Marshall, Wikipedia, Free Encycl. (2020). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barry_Marshall.

- G.B. Porro, M. Lazzaroni, Campylobacter pylori and ulcer recurrence, Lancet. 331 (1988) 593. [CrossRef]

- E.A.J.J. Rauws, G.N.J.J. Tytgat, Helicobacter pylori in duodenal and gastric ulcer disease, Baillieres. Clin. Gastroenterol. 9 (1995) 529–547. [CrossRef]

- K. Alam, T.T. Schubert, S.D. Bologna, C.K. Ma, Increased Density of Helicobacter pylori on Antral Biopsy is Associated with Severity of Acute and Chronic Inflammation and Likelihood of Duodenal Ulceration, Am. J. Gastroenterol. 87 (1992) 424–428.

- F.I. Tovey, M. Hobsley, Review: is Helicobacter pylori the primary cause of duodenal ulceration?, J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14 (1999) 1053–1056. [CrossRef]

- A.C. Ford, N.J. Talley, M. Hobsley, F.I. Tovey, K.D. Bardhan, J. Holton, A.C. Ford, N.J. Talley, Head to Head: Does Helicobacter pylori really cause duodenal ulcers? Yes, BMJ. 339 (2009) b2784. [CrossRef]

- Y. Elitsur, Z. Lawrence, Non-Helicobacter pylori related duodenal ulcer disease in children, Helicobacter. 6 (2001) 239–243. [CrossRef]

- R. Linda, D.F. Ransohoff, Is helicobacter pylori a cause of duodenal ulcer? A methodologic critique of current evidence, Am. J. Med. 91 (1991) 566–572. [CrossRef]

- V. Kate, N. Ananthakrishnan, F.I. Tovey, Is Helicobacter pylori Infection the Primary Cause of Duodenal Ulceration or a Secondary Factor? A Review of the Evidence, Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2013 (2013) 1–8. [CrossRef]

- M.S. Zelickson, C.M. Bronder, B.L. Johnson, J.A. Camunas, D.E. Smith, D. Rawlinson, S. Von, H.H. Stone, S.M. Taylor, Helicobacter pylori is not the predominant etiology for peptic ulcers requiring operation, Am. Surg. 77 (2011) 1054–60. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21944523.

- R. Scholl, Peptic ulcer disease and helicobacter pylori: How we know what we know [Article in German], Ther. Umschau. 72 (2015) 475–480. [CrossRef]

- f. Taylor, Essential Epidemiology: Principles and Applications., Int. J. Epidemiol. 32 (2003) 671–671. [CrossRef]

- U. Blumenthal, J. Fleisher, S. Esrey, A. Peasey, Epidemiology – a tool for the assessment of risk, in: L.F. and J. Bartram (Ed.), Water Qual. Guidel. Stand. Heal., IWA Publishing, London, UK., 2001: pp. 135–160. http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/76470/.

- J. Jin, S. Zhou, Q. Xu, J. An, Identification of risk factors in epidemiologic study based on ROC curve and network, Sci. Rep. 7 (2017) 46655. [CrossRef]

- M. Susser, Z. Stein, Civilization and peptic ulcer*, Int. J. Epidemiol. 31 (2002) 13–17. [CrossRef]

- B. Marshall, Commentary: Helicobacter as the ‘environmental factor’ in Susser and Stein’s cohort theory of peptic ulcer disease, Int. J. Epidemiol. 31 (2002) 21–22. [CrossRef]

- A. Sonnenberg, Causes underlying the birth-cohort phenomenon of peptic ulcer: analysis of mortality data 1911–2000, England and Wales, Int. J. Epidemiol. 35 (2006) 1090–1097. [CrossRef]

- D.Y. Graham, Y. Yamaoka, H. pylori and cagA: Relationships with gastric cancer, duodenal ulcer, and reflux esophagitis and its complications, Helicobacter. 3 (1998) 145–151. [CrossRef]

- A.E. Henriksson, A.C. Edman, I. Nilsson, D. Bergqvist, T. Wadstrom, Helicobacter pylori and the relation to other risk factors in patients with acute bleeding peptic ulcer, Scand.J Gastroenterol. 33 (1998) 1030–1033. [CrossRef]

- S. Hurlimann, S. Dür, P. Schwab, L. Varga, L. Mazzucchelli, R. Brand, F. Halter, Effects of Helicobacter pylori on gastritis, pentagastrin-stimulated gastric acid secretion, and meal-stimulated plasma gastrin release in the absence of peptic ulcer disease, Am. J. Gastroenterol. 93 (1998) 1277–1285. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yamaoka, T. Kodama, M. Kita, J. Imanishi, K. Kashima, D.Y. Graham, Relation between clinical presentation, Helicobacter pylori density, interleukin 1beta and 8 production, and cagA status, Gut. 45 (1999) 804–811. [CrossRef]

- J.F.L. Weel, R.W.M. van der Hulst, Y. Gerrits, P. Roorda, M. Feller, J. Dankert, G.N.J. Tytgat, A. van der Ende, The Interrelationship between Cytotoxin-Associated Gene A, Vacuolating Cytotoxin, and Helicobacter pylori-Related Diseases, J. Infect. Dis. 173 (1996) 1171–1175. [CrossRef]

- G. Oderda, D. Vaira, J. Holton, C. Ainley, F. Altare, M. Boero, A. Smith, N. Ansaldi, Helicobacter pylori in children with peptic ulcer and their families, Dig. Dis. Sci. 36 (1991) 572–576. [CrossRef]

- G. Watkinson, The Incidence of Chronic Peptic Ulcer Found at Necropsy: A Study of 20,000 Examinations Performed in Leeds in 1930-49 and in England and Scotland in 1956, Gut. 1 (1960) 14–30. [CrossRef]

- I.S. Levij, A.A.D.E.L.A. Fuente, A post-mortem study of gastric and duodenal peptic lesions: Part II Correlations with other pathological conditions, Gut. 4 (1963) 354–359. [CrossRef]

- C.G. Lindström, Gastric and Duodenal Peptic Ulcer Disease in a Well-Defined Population: A Prospective Necropsy Study in Malmö, Sweden, Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 13 (1978) 139–143. [CrossRef]

- C.F. van der Merwe, W. te Winkel, Ten-year observation of peptic ulceration at Ga-Rankuwa Hospital, Pretoria--1979-1988., S. Afr. Med. J. 78 (1990) 196–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2200148.

- M.G. Moshal, J.M. Spitaels, J. V Robbs, I.N. MacLeod, C.J. Good, Eight-year experience with 3392 endoscopically proven duodenal ulcers in Durban, 1972-79. Rise and fall of duodenal ulcers and a theory of changing dietary and social factors, Gut. 22 (1981) 327–331. [CrossRef]

- H. Shi, H. Xiong, W. Qian, R. Lin, Helicobacter pylori infection progresses proximally associated with pyloric metaplasia in age-dependent tendency: a cross-sectional study, BMC Gastroenterol. 18 (2018) 158. [CrossRef]

- A.J.P.M. Smout, L.M.A. Akkarmans, Motility of the gastroinal tract, Science Press, Beijing, page 18-22, 1996.

- C. Quan, N.J. Talley, Management of peptic ulcer disease not related to Helicobacter pylori or NSAIDs, Am. J. Gastroenterol. 97 (2002) 2950–2961. [CrossRef]

- L. Laine, R.J. Hopkins, L.S. Girardi, Has the impact of Helicobacter pylori therapy on ulcer recurrence in the United States been overstated? A meta-analysis of rigorously designed trials, Am. J. Gastroenterol. 93 (1998) 1409–1415. [CrossRef]

- D. Vaira, M. Menegatti, M. Miglioli, What Is the Role of Helicobacter pylori in Complicated Ulcer Disease?, Gastroenterology. 113 (1997) S78--S84. [CrossRef]

- J.P. Gisbert, J.M. Pajares, Review: Helicobacter pylori and bleeding peptic ulcer: what is the prevalence of the infection in patients with this complication?, Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 38 (2003) 2–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12608457.

- J. Gisbert, Helicobacter pylori and perforated peptic ulcer. Prevalence of the infection and role of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Dig. Liver Dis. 36 (2004) 116–120. [CrossRef]

- S. Szabo, Duodenal ulcer disease animal model: cysteamine-induced acute and chronic duodenal ulcer in the Rat, Am. J. Pathol. 93 (1978) 273–276.

- M. Feldman, P. Walker, J.L. Green, K. Weingarden, Life events stress and psychosocial factors in men with peptic ulcer disease: a multidimensional case-controlled study, Gastroenterology. 91 (1986) 1370–9. [CrossRef]

- T. Furuta, S. Baba, M. Takashima, H. Futami, H. Arai, M. Kajimura, H. Hanai, E. Kaneko, H. T. Furuta, S. Baba, M. Takashima, Effect of Helicobacter pylori Infection on Gastric Juice pH, Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 33 (1998) 357–363. [CrossRef]

- M.N. Peters, C.T. Richardson, Stressful Life Events, Acid Hypersecretion, and Ulcer Disease, Gastroenterology. 84 (1983) 114–119. [CrossRef]

- G.D. Smith, E. Susser, Zena Stein, Mervyn Susser and epidemiology: observation, causation and action, Int. J. Epidemiol. 31 (2002) 34–37. [CrossRef]

- G.B. Glavin, R. Murison, J.B. Overmier, W.P. Pare, H.K. Bakke, R.G. Henke, D.E. Hernandez, The neurobiology of stress ulcers, Brain Res. Rev. 16 (1991) 301–343. [CrossRef]

- D.E. Hernandez, Neurobiology of brain-gut interactions. Implications for ulcer disease, Dig. Dis. Sci. 34 (1989) 1809–1816. [CrossRef]

- D.E. Hernandez, The Role of Brain Peptides in the Pathogenesis of Experimental Stress Gastric Ulcers, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 597 (1990) 28–35. [CrossRef]

- D. Sutoo, K. Akiyama, A. Matsui, Gastric ulcer formation in cold-stressed mice related to a central calcium-dependent-dopamine synthesizing system, Neurosci. Lett. 249 (1998) 9–12. [CrossRef]

- M. Joëls, H. Karst, D. Alfarez, V.M. Heine, Y. Qin, E. Van Riel, M. Verkuyl, P.J. Lucassen, H.J. Krugers, Effects of chronic stress on structure and cell function in rat hippocampus and hypothalamus, Stress. 7 (2004) 221–231. [CrossRef]

- P.G. Henke, Attenuation of shock-induced ulcers after lesions in the medial amygdala, Physiol. Behav. 27 (1981) 143–146. [CrossRef]

- T. Tanaka, M. Yoshida, H. Yokoo, M. Tomita, M. Tanaka, Expression of aggression attenuates both stress-induced gastric ulcer formation and increases in noradrenaline release in the rat amygdala assessed by intracerebral microdialysis, Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 59 (1998) 27–31. [CrossRef]

- P.G. Henke, The centromedial amygdala and gastric pathology in rats, Physiol. Behav. 25 (1980) 107–112. [CrossRef]

- P.G. Henke, The amygdala and forced immobilization of rats, Behav. Brain Res. 16 (1985) 19–24. [CrossRef]

- C. Tennant, K. Goulston, P. Langeluddecke, Psychological correlates of gastric and duodenal ulcer disease, Psychol. Med. 16 (1986) 365–371. [CrossRef]

- S. Levenstein, C. Prantera, M.L. Scribano, V. Varvo, E. Berto, S. Spinella, Psychologic predictors of duodenal ulcer healing, J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 22 (1996) 84–89. [CrossRef]

- G. Magni, A. Salmi, A. Paterlini, A. Merlo, Psychological distress in duodenal ulcer and acute gastroduodenitis, Dig. Dis. Sci. 27 (1982) 1081–1084. [CrossRef]

- C.H. Cho, K.H. Lai, C.W. Ogle, Y.T. Tsai, S.D. Lee, K.J. Lo, The role of histamine and serotonin in gastric acid secretion: A comparative study in gastric and duodenal ulcer patients, J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1 (1986) 437–442. [CrossRef]

- J.Q. Huang, R.H. Hunt, pH, Healing rate and symptom relief in acid-related diseases, Yale J. Biol. Med. 69 (1996) 159–174. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9112748.

- P. Miner, Review article: relief of symptoms in gastric acid-related diseases--correlation with acid suppression in rabeprazole treatment, Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 20 Suppl 6 (2004) 20–29. [CrossRef]

- J.W. Konturek, W. Domschke, Helicobacter pylori and gastric acid secretion, Z. Gastroenterol. 37 (1999) 187–94. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10190251.

- J.W. Rademaker, R.H. Hunt, Helicobacter pylori and Gastric Acid Secretion: The Ulcer Link?, Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 26 (1991) 71–77. [CrossRef]

- A.J. Blair, M. Feldman, C. Barnett, J.H. Walsh, C.T. Richardson, Detailed comparison of basal and food-stimulated gastric acid secretion rates and serum gastrin concentrations in duodenal ulcer patients and normal subjects., J. Clin. Invest. 79 (1987) 582–587. [CrossRef]

- R.S. Boles, Modern Medical and Surgical Treatment of Peptic Ulcer: An Appraisal, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 136 (1948) 528–535. [CrossRef]

- P. Malfertheiner, F.K.L. Chan, K.E.L. McColl, Peptic ulcer disease, Lancet. 374 (2009) 1449–1461. [CrossRef]

- J. Parsonnet, Helicobacter pylori: the size of the problem, Gut. 43 (1998) S6–S9. [CrossRef]

- P.W.Y. Chiu, Bleeding peptic ulcers: the current management, Dig. Endosc. 22 Suppl 1 (2010) S19-21. [CrossRef]

- A. Schmassmann, Mechanisms of Ulcer Healing and Effects of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs, Am. J. Med. 104 (1998) 43S-51S. [CrossRef]

- N.D. Yeomans, The ulcer sleuths: The search for the cause of peptic ulcers, J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 26 (2011) 35–41. [CrossRef]

- C.J. Hawkey, I. Wilson, J. Naesdal, G. Långström, A.J. Swannell, N.D. Yeomans, Influence of sex and Helicobacter pylori on development and healing of gastroduodenal lesions in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug users, Gut. 51 (2002) 344–350. [CrossRef]

- P. Malfertheiner, F. Megraud, C. O’Morain, F. Bazzoli, E. El-Omar, D. Graham, R. Hunt, T. Rokkas, N. Vakil, E.J. Kuipers, Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report, Gut. 56 (2007) 772–781. [CrossRef]

- A. Sonnenberg, H. Müller, F. Pace, Birth-cohort analysis of peptic ulcer mortality in Europe, J. Chronic Dis. 38 (1985) 309–317. [CrossRef]

- M. Susser, Peptic Ulcer: Rise and Fall. Christie DA, Tansey EM (eds). Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine. Vol.14, 2002. London: The Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine, 2002, £10.00 ISBN: 0-85484-084-2., Int. J. Epidemiol. 32 (2003) 674–675. [CrossRef]

- Editors Biography.com, Barry J. Marshall Biography.com, (2014). https://www.biography.com/people/barry-j-marshall-40435 (accessed December 10, 2017).

- R. Zetterström, The Nobel Prize in 2005 for the discovery of Helicobacter pylori: Implications for child health, Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 95 (2006) 3–5. [CrossRef]

- H.J. Windle, D. Kelleher, J.E. Crabtree, Childhood Helicobacter pylori Infection and Growth Impairment in Developing Countries: A Vicious Cycle?, Pediatrics. 119 (2007) e754–e759. [CrossRef]

- G.L.H. Wong, V.W.S. Wong, Y. Chan, J.Y.L. Ching, K. Au, A.J. Hui, L.H. Lai, D.K.L. Chow, D.K.F. Siu, Y.N. Lui, J.C.Y. Wu, K.F. To, L.C.T. Hung, H.L.Y. Chan, J.J.Y. Sung, F.K.L. Chan, High Incidence of Mortality and Recurrent Bleeding in Patients With Helicobacter pylori-Negative Idiopathic Bleeding Ulcers, Gastroenterology. 137 (2009) 525–531. [CrossRef]

- R.J. Whitaker, Aristotle is not dead: Student understanding of trajectory motion, Am. J. Phys. 51 (1983) 352–357. [CrossRef]

- F. Wesemael, A comment on Adams’ measurement of the gravitational redshift of Sirius B, Q. J. R. Astron. Soc. 26 (1985) 273–278. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1985QJRAS..26..273W.

- I. Newton, A.E. Shapiro, The Principia: Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, Phys. Today. (2000). 2000. [CrossRef]

- D. Kilakos, Jimena Canales, The Physicist and the Philosopher: Einstein, Bergson and the Debate that Changed our Understanding of Time, Almagest. 8 (2017) 129–132. [CrossRef]

- D.A. Howard, Albert Einstein as a Philosopher of Science, Phys. Today. 58 (2005) 34–40. [CrossRef]

- M. Tavakol, Z. Aa, Medical Research Paradigms: Positivistic Inquiry Paradigm versus Naturalistic Inquiry Paradigm, J. Med. Educ. 5 (2004) 75–80. [CrossRef]

- M. Mulkay, G.N. Gilbert, Putting philosophy to work: Karl Popper’s Influence on Scientific Practice, Philos. Soc. Sci. 11 (1981) 389–407. [CrossRef]

- N. Sesardic, Philosophy and Science (in Yugoslavian), Filoz. Istraz. 15 (1985) 797–802.

- W. Carr, Philosophy, Methodology and Action Research, J. Philos. Educ. 40 (2006) 421–435. [CrossRef]

|

| Etiological Theory | Theory of H. Pylori [11] | Theory of Nodes [27,28,29,30,31] |

| 15 characteristics [6] | None of the 15 can be explained | All the 15 are explained |

| Etiology | Peptic ulcers are an infectious disease caused by the infection of H. pylori [11]. | Peptic ulcers are a psychosomatic disease triggered by psychological stress [27]. |

| Morphology of gastric ulcers [115] | Remains unknown | Explained, the only phenomenon needs to be verified [28]. |

| Predilection sites of gastric ulcers [116] | Remains unknown | Explained [28]. |

| Relapse and Multiplicity [87,117] | Remains unknown | Explained [28]. |

| Bleeding and Perforation [118] | Remains unknown | Explained [28]. |

| Epidemiology | 3 observations/phenomena were used as supporting evidence [15]; it might be able explain the other 3 observations. All the others remain unexplained. | All explained [27,28,29,30,31]. All 3 supporting evidences in Theory of H. pylori were identified as illusions, and the other 3 H. pylori explainable observations were mis-interpreted in Theory of H. pylori. |

|

81 observations/ Phenomenon [6] |

75 of 81 cannot be explained; 45 are unrelated to H pylori. | All 81 are explained; leaves no observations/phenomena unknown |

| 36 observations/phenomena associated with H. pylori |

30 of 36 cannot be explained. | All 36 are explained [27,28,29,30,31]. |

| 45 observations/phenomenon unassociated with H. pylori | None can be explained because many patients are H. pylori-negative [33,52,53]. | All 45 are explained [27,28,29,30,31]. |

| 4 Controversies | None of the 4 is addressed | All 4 are addressed clearly |

| Roles of H. pylori | Controversial [12,56,61,62,65] | Addressed: H. pylori is not an etiological factor but plays a secondary role in only the late phase of ulceration [27,28,29]. |

| Roles of gastric acid | Unknown [12,111] | Addressed [27,28]. |

| Roles of NSAIDs | Unknown [23,54,75,119,120,121,122] | Addressed [27,28]. |

| Idiopathic peptic ulcers | Unknown [18,23,54] | Addressed [27,28]. |

| 3 Major Mysteries | None of the 3 is resolved | All 3 are resolved clearly. |

| Birth-cohort Phenomena [71,123] | Remains a mystery [71,72] | Resolved [30]. |

| Seasonal Variations [9] | Remains a mystery | Resolved [31]. |

| African Enigma [25] | Remains a mystery | Resolved in this article: identified as an illusion due to incorrect etiology. |

| Similarities and differences between gastric & duodenal ulcers [1,124] | Remains unknown. | Fully illustrated [28]. |

| Therapy/effect | Antiacid and antibiotics treatments are the primary therapy; relapse frequently | Psychological treatments are the primary therapy; no relapse [29]. |

| Conclusions |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).