Submitted:

12 February 2023

Posted:

16 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational Details

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Cooperativity of H-Bonds in Reactant under External Electric Field

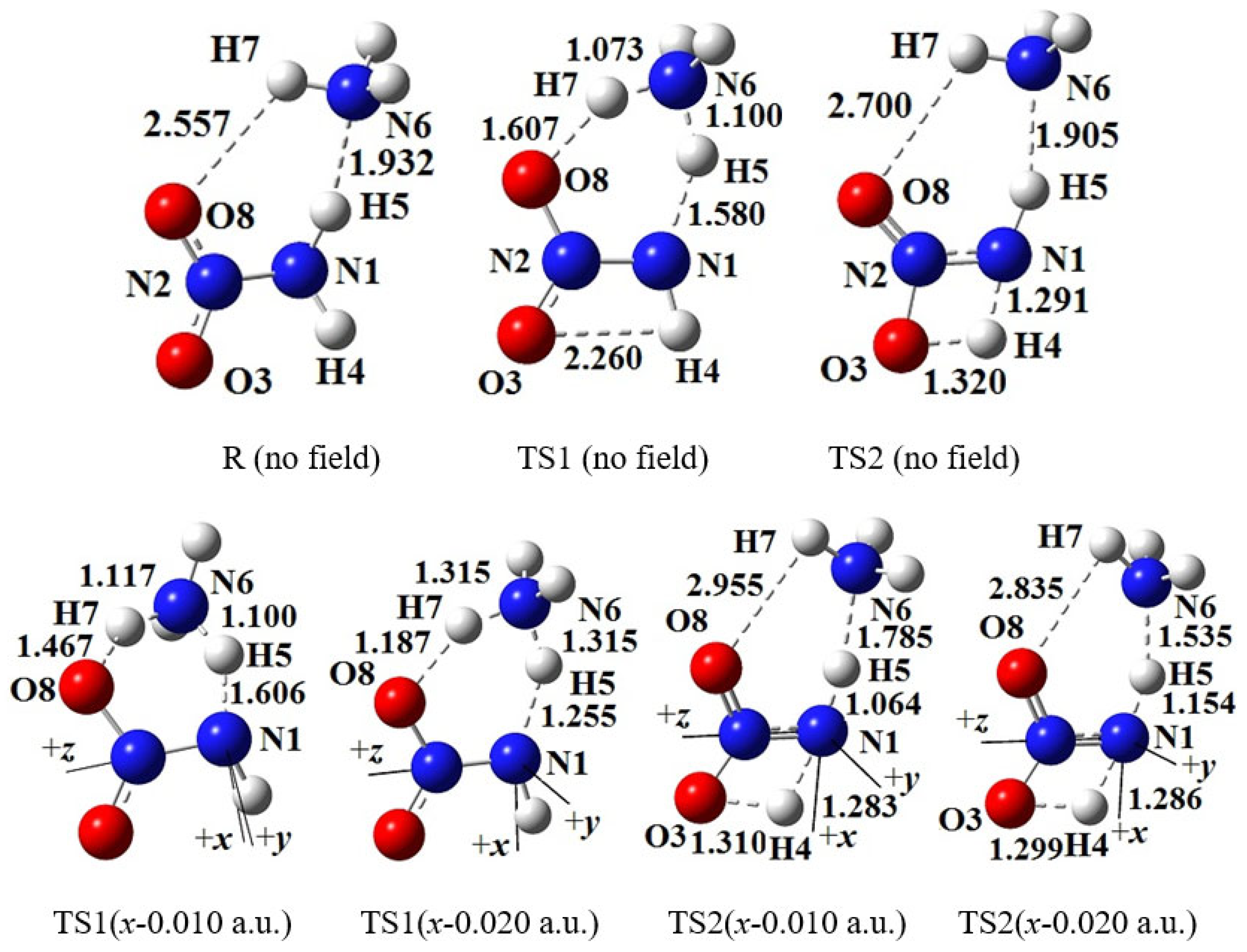

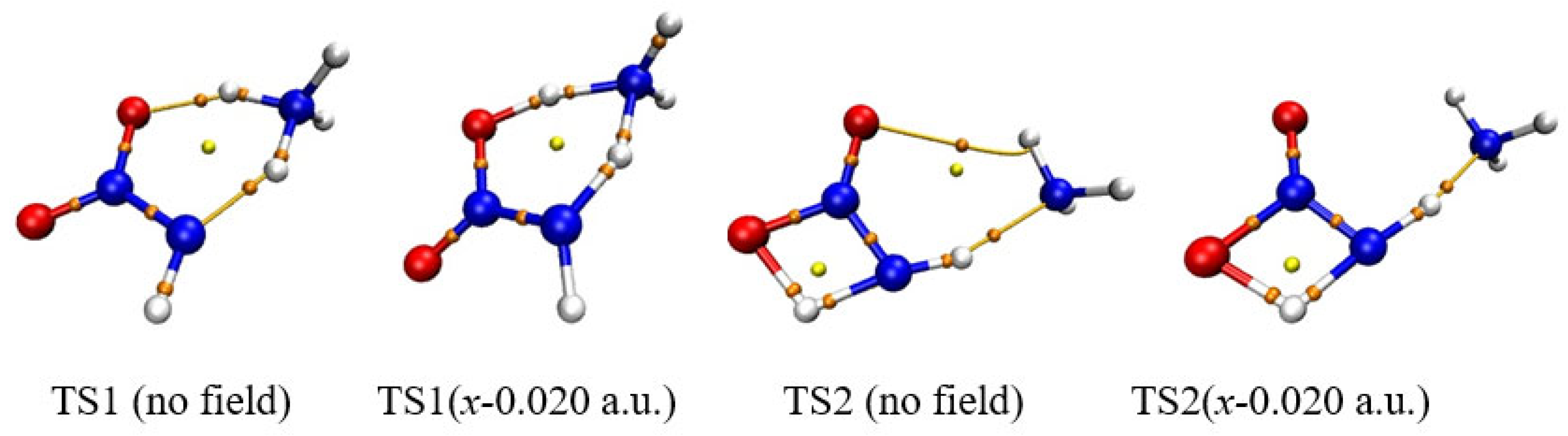

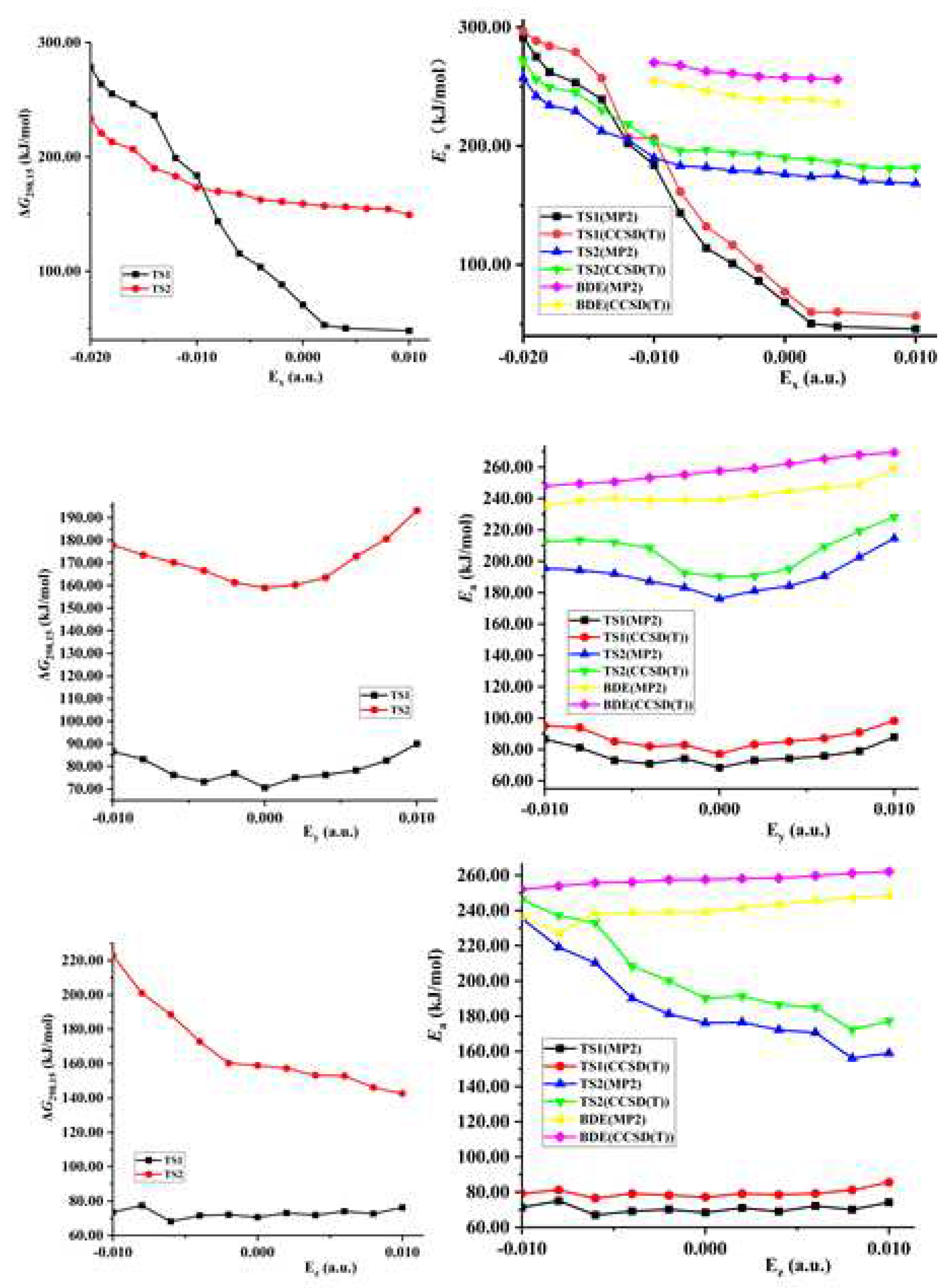

3.2. Concerted Effect of Intermolecular Hydrogen Exchange in External Electric Field

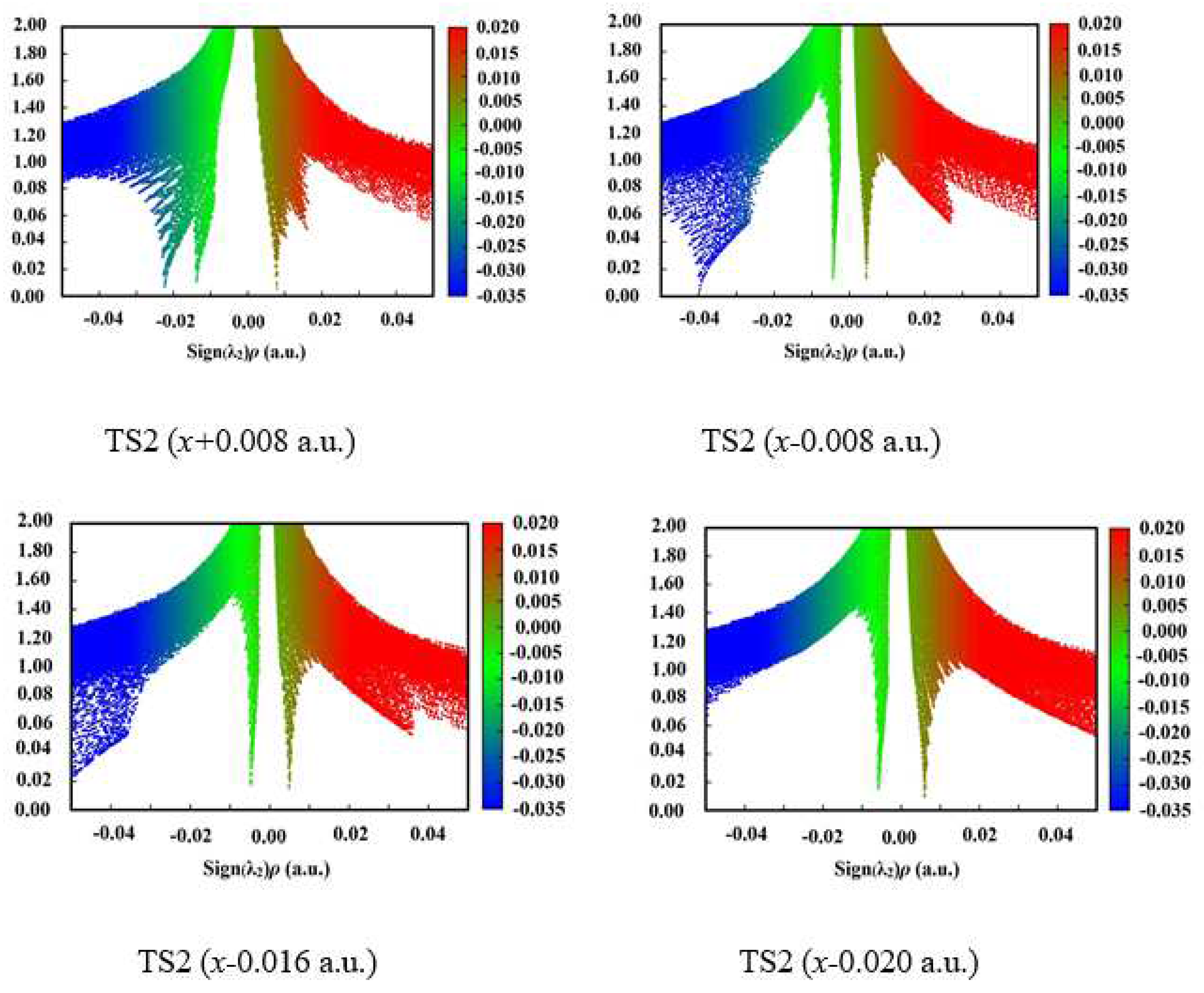

3.4. Prediction of Explosive Sensitivity under External Electric Field

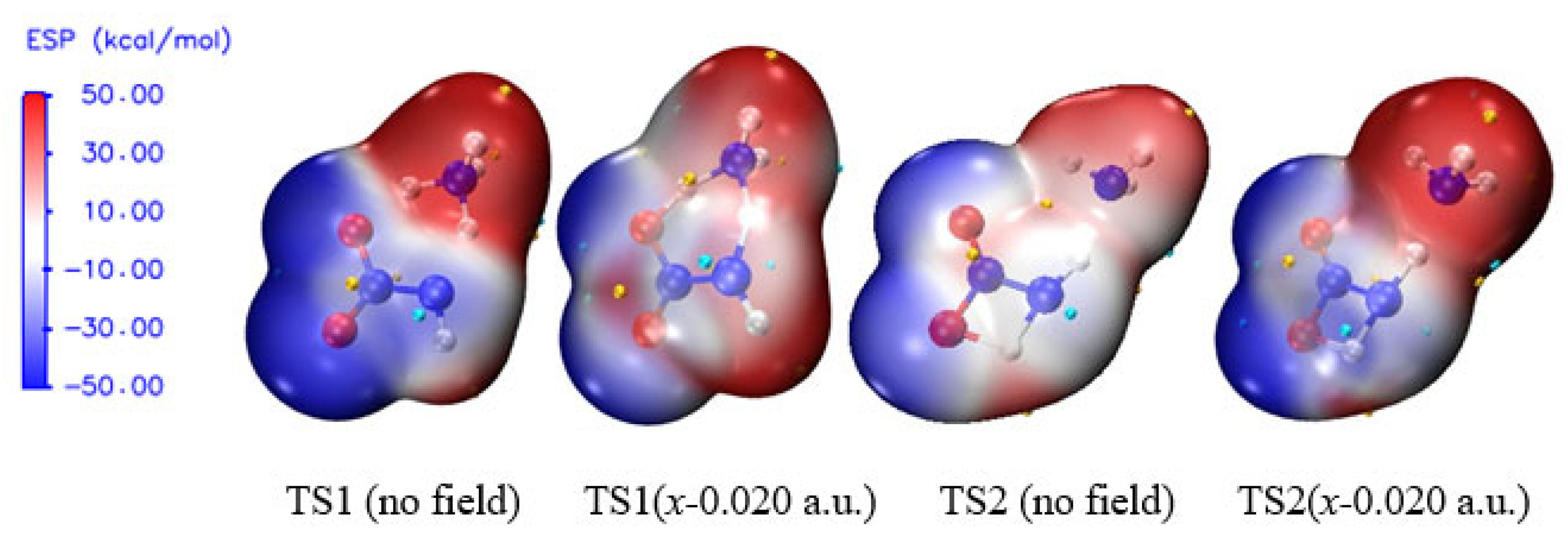

3.5. Surface Electrostatic Potentials of TS1 under the Field Along −x-Orientation

4. Conclusions

Ethical Statement

Availability of data and material

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Abdulazeem, M.S.; Alhasan, A.M.; Abdulrahmann, S. Initiation of solid explosives by laser. Int. J. Therm. Sci., 2011, 50, 2117–2121.

- Zhao, L.; Yi, T.; Zhu, H.; Fu, Q.; Sun, X.; Yang, S.; Zheng, W.; Jiang, S. Electromagnetic pulse effect during the bridge wire electric explosion. Chin. J. Energ. Mater., 2019, 27, 481–486.

- Borisenok, V.A.; Mikhailov, A.S.; Bragunets, V.A. Investigation of the polarization of explosives during impact and the influence of an external electric field on the impact sensitivity of superfine PETN. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B+, 2011, 5, 628–639.

- Rodzevich, A.P.; Gazenaur, E.G.; Kuzmina, L.V.; Krasheninin, V.I.; Gazenaur, N.V. The effect of electric field in the explosive sensitivity of silver azide. J. Phys. Conf. Ser., 2017, 830, 012131.

- Wang, W.J.; Sun, X.J.; Zhang, L.; Lei, F.; Guo, F.; Yang, S.; Fu, Q.B. Sub-microsecond interferometry diagnostic and 3D dynamic simulation of the bridgewire electrical explosion. Chin. J. Energ. Mater., 2019, 27, 473–480.

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S.; Concha, M.C.; Lane, P. Effects of electric fields upon energetic molecules: nitromethane and dimethylnitramine. Cent. Eur. J. Energ. Mat., 2007, 4, 3–21.

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S.; Lane, P. Computational determination of effects of electric fields upon “trigger linkages” of prototypical energetic molecules. Int. J. Quant. Chem., 2009, 109, 534–539.

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S. Computed effects of electric fields upon the C–NO2 and N–NO2 bonds of nitromethane and dimethylnitramine. Int. J. Quant. Chem., 2009, 109, 3–7.

- Zhou, Z.J.; Li, X.P.; Liu, Z.B.; Li, Z.R.; Huang, X.R.; Sun, C.C. Electric field-driven acid-base chemistry: proton transfer from acid (HCl) to Base (NH3/H2O). J. Phys. Chem. A, 2011, 115, 1418–1422.

- Venelin, E.; Valentin, M.; Nadezhda, M.; Marin, R.; Silvia, A.; Milena, S. A model system with intramolecular hydrogen bonding: Effect of external electric field on the tautomeric conversion and electronic structures. Comput. Theor. Chem., 2013, 1006, 113–122.

- Cerón-Carrasco, J.P.; Jacquemin, D. Electric field induced DNA damage: an open door for selective mutations. Chem. Commun., 2013, 49, 7578–7580.

- Shaik, S., de Visser, S.P.; Kumar, D. External electric field will control the selectivity of enzymatic-like bond activations. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2004, 126, 11746–11749.

- Shaik, S.; Mandal, D.; Ramanan, R. Oriented electric fields as future smart reagents in chemistry. Nat. Chem., 2016, 8, 1091−1098.

- Shaik, S.; Danovich, D.; Joy, J.; Wang, Z.; Stuyver, T. Electric-field mediated chemistry: Uncovering and exploiting the potential of (oriented) electric fields to exert chemical catalysis and reaction control. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2020, 142, 12551−12562.

- Welborn, V.V.; Head-Gordon, T. Computational design of synthetic enzymes. Chem. Rev., 2019, 119, 6613−6630.

- Wang, C.; Danovich, D.; Chen, H.; Shaik, S. Oriented external electric fields: Tweezers and catalysts for reactivity in halogen-bond complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2019, 141, 7122−7136.

- Laconsay, C.J.; Tsui, K.Y.; Tantillo, D.J. Tipping the balance: Theoretical interrogation of divergent extended heterolytic fragmentations. Chem. Sci., 2020, 11, 2231−2242.

- Zang, Y.; Zou, Q.; Fu, T.; Ng, F.; Fowler, B.; Yang, J.; Li, H.; Steigerwald, M.L.; Nuckolls, C.; Venkataraman, L. Directing isomerization reactions of cumulenes with electric fields. Nat. Commun., 2019, 10, 4482.

- Dubey, K.D.; Stuyver, T.; Kalita, S.; Shaik, S. Solvent-organization and rate-regulation of a menshutkin reaction by oriented-external electric fields are revealed by combined MD and QM/MM calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2020, 142, 9955−9965.

- Joy, J.; Stuyver, T.; Shaik, S. Oriented external electric fields and ionic additives elicit catalysis and mechanistic crossover in oxidative addition reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2020, 142, 3836−3850.

- Starr, R.L.; Fu, T.; Doud, E.A.; Stone, I.; Roy, X.; Venkataraman, L. Gold-carbon contacts from addition of aryl Iodides. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2020, 142, 7128−7133.

- Stuyver, T.; Huang, J.; Mallick, D.; Danovich, D.; Shaik, S. TITAN: A code for modeling and generating electric fields features and applications to enzymatic reactivity. J. Comput. Chem., 2020, 41, 74−82.

- Stuyver, T.; Danovich, D.; De Proft, F.; Shaik, S. Electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions: Mechanistic landscape, electrostatic and electric-field control of reaction rates, and mechanistic crossovers. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2019, 141, 9719−9730.

- Yu, L.-J.; Coote, M.L. Electrostatic switching between SN1 and SN2 pathways. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2019, 123, 582−589.

- Blyth, M.T.; Noble, B.B.; Russell, I.C.; Coote, M.L. Oriented internal electrostatic fields cooperatively promote ground- and excited-state reactivity: A case study in photochemical CO2 capture. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2020, 142, 606–613.

- Shaik, S.; Ramanan, R.; Danovich, D.; Mandal, D. Structure and reactivity/selectivity control by oriented-external electric fields. Chem. Soc. Rev., 2018, 47, 5125−5145.

- Stuyver, T.; Danovich, D.; Joy, J.; Shaik, S. External electric field effects on chemical structure and reactivity. WIRes. Comput. Mol. Sci., 2020, 10, e1438.

- Alemani, M.; Peters, M.V.; Hecht, S.; Rieder, K.H.; Moresco, F.; Grill, L. Electric field-induced isomerization of azobenzene by STM. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2006, 128, 14446–14447.

- Meir, R.; Chen, H.; Lai, W.; Shaik, S. Oriented electric fields accelerate diels−alder reactions and control the endo/exo selectivity. Chem. Phys. Chem., 2010, 11, 301−310.

- Ren, F.-d.; Shi, W.-j.; Cao, D.-l.; Li, Y.-x.; Zhang, D.-h.; Wang, X.-f.; Shi, Z.-y. External electric field reduces the explosive sensitivity: a theoretical investigation into the hydrogen transference kinetics of the NH2NO2∙∙∙H2O complex. J. Mol. Model., 2020, 26, 351.

- Cabalo, J.; Sausa, R. Theoretical and experimental study of the C–H stretching overtones of 2,4,6,8,10,12-hexanitro-2,4,6,8,10,12 hexaazaisowurtzitane (CL-20). J. Phys. Chem. A, 2013, 117, 9039–9046.

- Macharla, A.K.; Parimi, A.; Anuj, A.V. Decomposition mechanism of hexanitrohexaazaisowurtzitane (CL-20) by coupled computational and experimental study. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2019, 123, 4014−4020.

- Demske, D. The experimental aspects of coupling electrical energy into a dense detonation wave: Part 1. NSWC TR, 1982, pp79–143.

- Wang, Y.; Ren, F.; Cao, D. A dynamic and electrostatic potential prediction of the prototropic tautomerism between imidazole 3-oxide and 1-hydroxyimidazole in external electric field. J. Mol. Model., 2019, 25, 330.

- Ren, F.; Cao, D.; Shi, W.; You, M. A dynamic prediction of stability for nitromethane in external electric field. RSC Adv., 2017, 74, 47063–47072.

- Ren, F.; Cao, D.; Shi, W. A dynamics prediction of nitromethane → methyl nitrite isomerization in external electric field. J. Mol. Model., 2016, 22, 96.

- Shu, Y.J.; Dubikhin, V.V.; Nazin, G.M.; Manelis, G.B. Effect of solvents on thermal decomposition of RDX. Chin. J. Energ. Mater., 2000, 8, 108–110.

- Wang, H.B.; Shi, W.J.; Ren, F.D.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.L. A B3LYP and MP2(full) theoretical investigation into explosive sensitivity upon the formation of the intermolecular hydrogen-bonding interaction between the nitro group of RNO2(R = –CH3, –NH2, –OCH3) and HF, HCl or HBr. Comput. Theor. Chem., 2012, 994, 73–80.

- Li, B.H.; Shi, W.J.; Ren, F.D.; Wang, Y. A B3LYP and MP2(full) theoretical investigation into the strength of the C–NO2 bond upon the formation of the intermolecular hydrogen-bonding interaction between HF and the nitro group of nitrotriazole or its methyl derivatives. J. Mol. Model., 2013, 19, 511–519.

- Qiu, W.; Ren, F.D.; Shi, W.J.; Wang, Y.H. A theoretical study on the strength of the C–NO2 bond and ring strain upon the formation of the intermolecular H-bonding interaction between HF and nitro group in nitrocyclopropane, nitrocyclobutane, nitrocyclopentane or nitrocyclohexane. J. Mol. Model., 2015, 21, 114–122.

- Zhou, S.Q.; Zhao, F.Q.; Ju, X.H.; Cheng, X.C.; Yi, J.H. A density functional theory study of adsorption and decomposition of nitroamine molecules on the Al(111) surface. J Phys Chem C 114:9390–9397. J. Phys. Chem. C, 2010, 114, 9390–9397.

- Ju, G.Z.; Ju, Q. The theoretically thermodynamic and kinetic studies on the scission and rearrangement of NH2NO2. Chem. J. Chin. Univ., 1991, 12, 1669–1671.

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Caricato, M.; Li, X.; Hratchian, H.P.; Izmaylov, A.F.; Bloino, J.; Zheng, G.; Sonnenberg, J.L.; Hada, M.; Ehara, M.; Toyota, K.; Fukuda, R.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishida, M.; Nakajima, T.; Honda, Y.; Kitao, O.; Nakai, H.; Vreven, T.; Montgomery Jr, J.A.; Peralta, J.E.; Ogliaro, F.; Bearpark, M.; Heyd, J.J.; Brothers, E.; Kudin, K.N.; Staroverov, V.N.; Kobayashi, R.; Normand, J.; Raghavachari, K.; Rendell A.;, Burant, J.C.; Iyengar, S.S.; Tomasi, J.; Cossi, M.; Rega, N.; Millam, J.M.; Klene, M.; Knox, J.E.; Cross, J.B.; Bakken, V.; Adamo, C.; Jaramillo, J.; Gomperts, R.; Stratmann, R.E.; Yazyev, O.; Austin, A.J.; Cammi, R.; Pomelli, C.; Ochterski, J.W.; Martin, R.L.; Morokuma, K.; Zakrzewski, V.G.; Voth, G.A.; Salvador, P.; Dannenberg, J.J.; Dapprich, S.; Daniels, A.D.; Farkas, O.; Foresman, J.B.; Ortiz, J.V.; Cioslowski, J.; Fox, D.J. Gaussian 09, Revision B.01, Gaussian, Inc.; USA: Wallingford CT, 2010.

- Wigner, E.P. Über das überschreiten von potential schwellen bei chemischen reaktionen. Z. Phys. Chem. B, 1932, 19, 203–216.

- Cramer, C.J. Essentials of computational chemistry: Theories and models, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2002, New York.

- Arabi, A.A.; Matta, C.F. Effects of external electric fields on double proton transfer kinetics in the formic acid dimer. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2011, 13, 13738–13748.

- Eyring, H.; Eyring, E.M. Modern chemical kinetics, Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1963, New York.

- Biegler-König, F.W.; Bader, R.F.W.; Tang, T.H. Calculation of the average properties of atoms in molecules. II., J. Comput. Chem., 1982, 3, 317–328.

- Johnson, E.R.; Keinan, S.; Mori-Sánchez, P.; Contreras-García, J.; Cohen, A.J.; Yang, W. Revealing Noncovalent Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2010, 132, 6498–6506.

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S. Some molecular/crystalline factors that affect the sensitivities of energetic materials: molecular surface electrostatic potentials, lattice free space and maximum heat of detonation per unit volume. J. Mol. Model., 2015, 21, 25−35.

- Lu, T. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer, Version 3.3.5. 2014, Beijing.

- Ren, F.; Cao, D.; Shi, W.; You, M.; Li, M. A theoretical prediction of the possible trigger linkage of CH3NO2 and NH2NO2 in an external electric field. J. Mol. Model., 2015, 21, 145.

- Zeman, S.; Atalar, T.; Friedl, Z.; Ju, X.H. Accounts of the new aspects of nitromethane initiation reactivity. Cent. Eur. J. Energ. Mat., 2009, 6, 119–133.

- Mahadevi, A.S.; Sastry, G.N. Cooperativity in noncovalent interactions. Chem. Rev., 2016, 116, 2775−2825.

- Glasstone, S.; Laidler, K.J.; Eyring, H. The theory of rate processes, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1941, New York, 1st edn.

- Tasker, D. The properties of condensed explosives for electromagnetic energy coupling. NSWC TR, 1985, pp85–360.

- Piehler, T.; Hummer, C.; Benjamin, R.; Summers, E.; Mc Nesby, K.; Boyle, V. Preliminary study of coupling electrical energy to detonation reaction zone of primasheet-1000 explosive, 27th international symposium on ballistics, freiburg, Germany, 2013, pp 22–26.

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S. The fundamental nature and role of the electrostatic potential in atoms and molecules. Theor. Chem. Acc., 2002, 108, 134–142.

- Rice, B.M.; Hare, J.J. A quantum mechanical investigation of the relation between impact sensitivity and the charge distribution in energetic molecules. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2002, 106, 1770–1783.

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S. Impact sensitivity and crystal lattice compressibility/free space. J. Mol. Model., 2014, 20, 2223–2230.

- Murray, J.S.; Concha, M.C.; Politzer, P. Links between surface electrostatic potentials of energetic molecules, impact sensitivities and C–NO2/N–NO2 bond dissociation energies. Mol. Phys., 2009, 107, 89–97.

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S. in: Brinck T (ed) Green Energetic Materials, Wiley, Chichester, UK, ch. 2014, 3:45–62.

| Field | Imv | ΔG298.15 | k298.15 K | κ298.15 K | k298.15 K,C | ∆G688 K | k688 K | κ688 K | k688 K,C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No field | 368.4 | 70.58 | 2.86×100 | 1.132 | 3.24×100 | 88.62 | 2.68×106 | 1.025 | 2.74×106 |

| z-0.010 | 915.8 | 73.52 | 8.73×10-1 | 1.815 | 1.59×100 | 92.55 | 1.35×106 | 1.153 | 1.55×106 |

| z-0.008 | 872.7 | 77.39 | 1.83×10-1 | 1.740 | 3.19×10-1 | 93.10 | 1.22×106 | 1.139 | 1.39×106 |

| z-0.006 | 492.0 | 68.13 | 7.68×100 | 1.235 | 9.49×100 | 85.62 | 4.53×106 | 1.044 | 4.73×106 |

| z-0.004 | 379.3 | 71.55 | 1.93×100 | 1.140 | 2.20×100 | 84.18 | 5.82×106 | 1.026 | 5.97×106 |

| z-0.002 | 378.1 | 72.08 | 1.56×100 | 1.139 | 1.78×100 | 86.03 | 4.21×106 | 1.026 | 4.32×106 |

| z+0.002 | 355.6 | 73.02 | 1.07×100 | 1.123 | 1.20×100 | 88.92 | 2.54×106 | 1.023 | 2.60×106 |

| z+0.004 | 320.8 | 71.83 | 1.73×100 | 1.100 | 1.90×100 | 90.41 | 1.96×106 | 1.019 | 2.00×106 |

| z+0.006 | 337.0 | 74.03 | 7.11×10-1 | 1.110 | 7.90×10-1 | 92.50 | 1.36×106 | 1.021 | 1.39×106 |

| z+0.008 | 293.5 | 72.59 | 1.27×100 | 1.084 | 1.38×100 | 87.37 | 3.33×106 | 1.016 | 3.39×106 |

| z+0.010 | 271.9 | 76.27 | 2.88×10-1 | 1.072 | 3.09×10-1 | 95.52 | 8.02×105 | 1.013 | 8.13×105 |

| y-0.010 | 350.6 | 86.55 | 4.56×10-3 | 1.119 | 5.10×10-3 | 110.38 | 5.97×104 | 1.022 | 6.10×104 |

| y-0.008 | 327.9 | 83.18 | 1.77×10-2 | 1.104 | 1.96×10-2 | 106.26 | 1.23×105 | 1.020 | 1.25×105 |

| y-0.006 | 342.8 | 76.18 | 2.99×10-1 | 1.114 | 3.33×10-1 | 95.01 | 8.76×105 | 1.021 | 8.95×105 |

| y-0.004 | 360.7 | 73.18 | 1.00×100 | 1.126 | 1.13×100 | 89.17 | 2.43×106 | 1.024 | 2.49×106 |

| y-0.002 | 367.6 | 76.92 | 2.22×10-1 | 1.131 | 2.51×10-1 | 92.35 | 1.40×106 | 1.025 | 1.43×106 |

| y+0.002 | 335.1 | 75.00 | 4.81×10-1 | 1.109 | 5.33×10-1 | 93.25 | 1.19×106 | 1.020 | 1.22×106 |

| y+0.004 | 320.7 | 76.24 | 2.92×10-1 | 1.100 | 3.21×10-1 | 95.18 | 8.51×105 | 1.019 | 8.67×105 |

| y+0.006 | 303.5 | 78.24 | 1.30×10-1 | 1.090 | 1.42×10-1 | 91.00 | 1.77×106 | 1.017 | 1.80×106 |

| y+0.008 | 349.2 | 82.66 | 2.19×10-2 | 1.118 | 2.45×10-2 | 106.36 | 1.20×105 | 1.022 | 1.23×105 |

| y+0.010 | 341.8 | 90.03 | 1.12×10-3 | 1.114 | 1.25×10-3 | 108.27 | 8.63×104 | 1.021 | 8.81×104 |

| x+0.010 | 262.0 | 48.04 | 2.54×104 | 1.067 | 2.71×104 | 62.18 | 2.72×108 | 1.013 | 2.76×108 |

| x+0.004 | 260.0 | 50.17 | 1.08×104 | 1.066 | 1.15×104 | 60.54 | 3.63×108 | 1.012 | 3.67×108 |

| x+0.002 | 310.4 | 52.99 | 3.45×103 | 1.094 | 3.77×103 | 62.15 | 2.74×108 | 1.018 | 2.79×108 |

| x-0.002 | 445.0 | 88.37 | 2.19×10-3 | 1.192 | 2.61×10-3 | 112.26 | 4.30×104 | 1.036 | 4.45×104 |

| x-0.004 | 547.3 | 103.71 | 4.49×10-6 | 1.291 | 5.80×10-6 | 128.71 | 2.42×103 | 1.055 | 2.55×103 |

| x-0.006 | 689.6 | 115.53 | 3.82×10-8 | 1.462 | 5.58×10-8 | 138.53 | 4.35×102 | 1.087 | 4.73×102 |

| x-0.008 | 868.6 | 143.57 | 4.67×10-13 | 1.733 | 8.09×10-13 | 180.02 | 3.08×10-1 | 1.138 | 3.50×10-1 |

| x-0.010 | 649.2 | 183.67 | 4.41×10-20 | 1.410 | 6.21×10-20 | 227.18 | 8.08×10-5 | 1.077 | 8.71×10-5 |

| x-0.012 | 420.2 | 199.01 | 9.05×10-23 | 1.172 | 1.06×10-22 | 248.26 | 2.03×10-6 | 1.032 | 2.09×10-6 |

| x-0.014 | 1124.3 | 236.28 | 2.68×10-29 | 2.228 | 5.96×10-29 | 288.33 | 1.84×10-9 | 1.231 | 2.26×10-9 |

| x-0.016 | 1157.9 | 246.19 | 2.91×10-31 | 2.303 | 1.13×10-30 | 336.05 | 4.38×10-13 | 1.245 | 5.45×10-13 |

| x-0.018 | 1528.7 | 255.11 | 1.34×10-32 | 3.271 | 4.40×10-32 | 340.29 | 2.09×10-13 | 1.426 | 2.98×10-13 |

| x-0.019 | 1633.0 | 263.62 | 4.34×10-34 | 3.591 | 1.56×10-33 | 365.03 | 2.76×10-15 | 1.487 | 4.11×10-15 |

| x-0.020 | 1638.5 | 278.33 | 1.15×10-36 | 3.609 | 4.15×10-36 | 368.81 | 1.43×10-15 | 1.490 | 2.13×10-15 |

| Field | Imv | ΔG298.15 | k298.15 K | κ298.15 K | k298.15 K,C | ∆G688 K | k688 K | κ688 K | k688 K,C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No field | 1955.0 | 158.93 | 9.51×10-16 | 4.714 | 4.48×10-15 | 179.59 | 3.32×10-1 | 1.697 | 5.63×10-1 |

| z-0.010 | 1984.7 | 222.84 | 6.05×10-27 | 4.828 | 2.92×10-26 | 252.80 | 9.17×10-7 | 1.719 | 1.58×10-6 |

| z-0.008 | 1977.6 | 201.03 | 4.01×10-23 | 4.800 | 1.92×10-22 | 221.13 | 2.33×10-4 | 1.714 | 3.99×10-4 |

| z-0.006 | 1970.0 | 188.51 | 6.26×10-21 | 4.771 | 2.98×10-20 | 210.02 | 1.63×10-3 | 1.708 | 2.78×10-3 |

| z-0.004 | 1960.6 | 172.80 | 3.54×10-18 | 4.735 | 1.67×10-17 | 198.26 | 1.27×10-2 | 1.701 | 2.16×10-2 |

| z-0.002 | 1958.1 | 160.25 | 5.59×10-16 | 4.726 | 2.64×10-15 | 182.08 | 2.15×10-1 | 1.700 | 3.65×10-1 |

| z+0.002 | 1949.4 | 157.28 | 1.85×10-15 | 4.693 | 8.69×10-15 | 176.73 | 5.47×10-1 | 1.693 | 9.27×10-1 |

| z+0.004 | 1947.6 | 153.19 | 9.64×10-15 | 4.686 | 4.52×10-14 | 174.10 | 8.66×10-1 | 1.692 | 1.47×100 |

| z+0.006 | 1939.8 | 152.83 | 1.11×10-14 | 4.656 | 5.19×10-14 | 170.70 | 1.57×100 | 1.687 | 2.65×100 |

| z+0.008 | 1934.2 | 146.05 | 1.72×10-13 | 4.635 | 7.96×10-13 | 169.04 | 2.10×100 | 1.683 | 3.53×100 |

| z+0.010 | 1927.1 | 142.64 | 6.79×10-13 | 4.609 | 3.13×10-12 | 163.18 | 5.84×100 | 1.678 | 9.80×100 |

| y-0.010 | 1972.0 | 177.92 | 4.48×10-19 | 4.779 | 2.14×10-18 | 202.05 | 6.54×10-3 | 1.710 | 1.12×10-2 |

| y-0.008 | 1970.3 | 173.51 | 2.66×10-18 | 4.772 | 1.27×10-17 | 195.07 | 2.22×10-2 | 1.708 | 3.79×10-2 |

| y-0.006 | 1962.9 | 170.22 | 1.00×10-17 | 4.744 | 4.75×10-17 | 194.35 | 2.51×10-2 | 1.703 | 4.28×10-2 |

| y-0.004 | 1958.3 | 166.57 | 4.36×10-17 | 4.726 | 2.06×10-16 | 186.22 | 1.04×10-1 | 1.700 | 1.77×10-1 |

| y-0.002 | 1957.2 | 161.39 | 3.53×10-16 | 4.722 | 1.67×10-15 | 183.37 | 1.71×10-1 | 1.699 | 2.91×10-1 |

| y+0.002 | 1958.9 | 160.26 | 5.56×10-16 | 4.729 | 2.63×10-15 | 180.09 | 3.04×10-1 | 1.700 | 5.17×10-1 |

| y+0.004 | 1959.8 | 163.55 | 1.48×10-16 | 4.732 | 6.98×10-16 | 186.81 | 9.39×10-2 | 1.701 | 1.60×10-1 |

| y+0.006 | 1960.2 | 172.89 | 3.41×10-18 | 4.734 | 1.61×10-17 | 196.37 | 1.77×10-2 | 1.701 | 3.01×10-2 |

| y+0.008 | 1969.4 | 180.62 | 1.51×10-19 | 4.769 | 7.19×10-19 | 205.10 | 3.84×10-3 | 1.708 | 6.55×10-3 |

| y+0.010 | 1974.0 | 193.18 | 9.51×10-22 | 4.786 | 4.55×10-21 | 223.29 | 1.59×10-4 | 1.711 | 2.73×10-4 |

| x+0.010 | 1985.2 | 149.23 | 4.76×10-14 | 4.829 | 2.3×10-13 | 165.63 | 3.81×100 | 1.719 | 6.55×100 |

| x+0.008 | 1979.4 | 154.44 | 5.82×10-15 | 4.807 | 2.8×10-14 | 173.52 | 9.59×10-1 | 1.715 | 1.65×100 |

| x+0.006 | 1973.6 | 154.92 | 4.8×10-15 | 4.785 | 2.29×10-14 | 176.06 | 6.15×10-1 | 1.711 | 1.06×100 |

| x+0.004 | 1968.1 | 156.39 | 2.65×10-15 | 4.764 | 1.26×10-14 | 177.72 | 4.60×10-1 | 1.707 | 7.85×10-1 |

| x+0.002 | 1961.5 | 157.08 | 2.01×10-15 | 4.739 | 9.51×10-15 | 178.50 | 4.01×10-1 | 1.702 | 6.83×10-1 |

| x-0.002 | 1947.4 | 160.77 | 4.53×10-16 | 4.685 | 2.12×10-15 | 180.67 | 2.75×10-1 | 1.692 | 4.65×10-1 |

| x-0.004 | 1939.5 | 162.53 | 2.23×10-16 | 4.655 | 1.04×10-15 | 184.66 | 1.37×10-1 | 1.686 | 2.31×10-1 |

| x-0.006 | 1927.1 | 167.62 | 2.86×10-17 | 4.609 | 1.32×10-16 | 188.41 | 7.10×10-2 | 1.678 | 1.19×10-1 |

| x-0.008 | 1917.0 | 169.78 | 1.20×10-17 | 4.571 | 5.46×10-17 | 193.85 | 2.74×10-2 | 1.671 | 4.58×10-2 |

| x-0.010 | 1906.4 | 173.2 | 3.01×10-18 | 4.531 | 1.36×10-17 | 196.72 | 1.66×10-2 | 1.663 | 2.76×10-2 |

| x-0.012 | 1895.5 | 183.20 | 5.33×10-20 | 4.491 | 2.39×10-19 | 210.02 | 1.63×10-3 | 1.656 | 2.69×10-3 |

| x-0.014 | 1884.1 | 190.13 | 3.25×10-21 | 4.449 | 1.45×10-20 | 216.85 | 4.92×10-4 | 1.648 | 8.11×10-4 |

| x-0.016 | 1871.8 | 206.82 | 3.88×10-24 | 4.404 | 1.71×10-23 | 239.71 | 9.05×10-6 | 1.639 | 1.48×10-5 |

| x-0.018 | 1858.7 | 212.95 | 3.27×10-25 | 4.357 | 1.42×10-24 | 241.63 | 6.46×10-6 | 1.630 | 1.05×10-5 |

| x-0.019 | 1851.0 | 220.76 | 2.48×10-28 | 4.329 | 1.07×10-27 | 246.46 | 2.78×10-6 | 1.625 | 4.52×10-6 |

| x-0.020 | 1843.8 | 233.57 | 7.98×10-29 | 4.303 | 3.44×10-28 | 248.93 | 1.80×10-6 | 1.620 | 2.92×10-6 |

,

,  , kcal/mol) and their variances ( and (kcal/mol)2) as well as polar surface area (PSA, %) for TS1 and transition state NH2NO2∙∙∙H2O→NHN(O)OH∙∙∙H2O (TS) in the different field strengths (a.u.) along −x-orientation at the MP2/6-311++G(2d,p) level.

, kcal/mol) and their variances ( and (kcal/mol)2) as well as polar surface area (PSA, %) for TS1 and transition state NH2NO2∙∙∙H2O→NHN(O)OH∙∙∙H2O (TS) in the different field strengths (a.u.) along −x-orientation at the MP2/6-311++G(2d,p) level.

,

,  , kcal/mol) and their variances ( and (kcal/mol)2) as well as polar surface area (PSA, %) for TS1 and transition state NH2NO2∙∙∙H2O→NHN(O)OH∙∙∙H2O (TS) in the different field strengths (a.u.) along −x-orientation at the MP2/6-311++G(2d,p) level.

, kcal/mol) and their variances ( and (kcal/mol)2) as well as polar surface area (PSA, %) for TS1 and transition state NH2NO2∙∙∙H2O→NHN(O)OH∙∙∙H2O (TS) in the different field strengths (a.u.) along −x-orientation at the MP2/6-311++G(2d,p) level.| Field | VS-,O8(TS1) |

(TS1) (TS1) |

(TS1) (TS1) |

(TS1) | (TS1) | PSA | VS-,O6(TS)a |

(TS) (TS) |

(TS)a (TS)a

|

(TS)a | (TS)a | PSA(TS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Field | -55.8 | 34.8 | -28.2 | 381.9 | 264.3 | 82.7 | -23.2 | 22.0 | -16.1 | 235.9 | 93.5 | 73.2 |

| x-0.002 | -54.4 | 33.1 | -27.5 | 346.8 | 254.8 | 81.7 | -22.4 | 21.5 | -17.3 | 231.8 | 89.5 | 72.1 |

| x-0.004 | -53.0 | 31.5 | -26.6 | 310.2 | 246.0 | 80.6 | -20.3 | 20.8 | -16.5 | 220.3 | 78.3 | 70.8 |

| x-0.006 | -51.7 | 29.8 | -25.8 | 278.7 | 223.5 | 78.3 | -21.6 | 19.6 | -16.6 | 218.1 | 65.7 | 70.3 |

| x-0.008 | -50.7 | 32.5 | -27.2 | 251.6 | 190.7 | 83.9 | -20.3 | 21.3 | -15.1 | 206.2 | 58.3 | 69.5 |

| x-0.010 | -49.6 | 34.4 | -28.2 | 279.9 | 146.2 | 90.6 | -19.7 | 19.7 | -12.2 | 223.4 | 51.4 | 68.8 |

| x-0.012 | -47.8 | 35.2 | -26.7 | 288.3 | 122.8 | 90.8 | -30.2 | 22.5 | -13.6 | 218.7 | 72.1 | 68.1 |

| x-0.013 | -29.8 | 19.3 | -12.8 | 201.3 | 63.6 | 67.3 | ||||||

| x-0.014 | -44.9 | 32.6 | -24.3 | 250.2 | 109.7 | 88.4 | -29.5 | 20.2 | -15.1 | 212.9 | 55.0 | 67.2 |

| x-0.015 | -28.2 | 21.3 | -12.7 | 197.9 | 49.8 | 65.2 | ||||||

| x-0.016 | -41.2 | 28.7 | -21.6 | 211.8 | 111.3 | 84.1 | ||||||

| x-0.018 | -37.6 | 22.0 | -19.9 | 167.6 | 102.5 | 76.5 | ||||||

| x-0.019 | -35.0 | 19.3 | -18.2 | 139.2 | 91.3 | 70.8 | ||||||

| x-0.020 | -33.1 | 16.7 | -15.6 | 116.9 | 90.1 | 68.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).