Submitted:

11 February 2023

Posted:

13 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Animal models of chronic kidney disease

2.1.1. Features of mild chronic kidney disease

| Groups Name |

Group 1 WKY2 |

Group 2 SO2 |

Group 3 SO6 |

Group 4 Nx2 |

Group 5 Nx6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Wistar Kyoto rats | Spontaneously hypertensive rats | |||

| Model | normotensive control | control | mild CKD models | ||

| Surgery | sham-operated | sham-operated | sham-operated | 3/4 nephrectomy | 3/4 nephrectomy |

| Duration of the experiment, mo | 2 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 |

| Rats number, n | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 135 (130-142)2-4# | 170 (160-182) 3,4*5# | 195 (183-200) | 195 (180-205) | 208 (195-223) |

| Serum creatinine, mmol/L | 74.0 (69.0;79.5)3-5# | 73.0 (67.5;77.0)3-5‡ | 83.2 (80.5;85.5)4,5# | 92.5 (91.0;97.0)5# |

106.5 (101.5;110.0) |

| Urea, mmol/L | 4.89 (3.81;6.93)3-5# | 5.36 (4.19;6.41)4,5† | 5.37 (4.36;7.09) 4,5# | 7.10 (6.95;7.58) 5# | 10.7 (9.63;12.4) |

| Creatinine clearance, ml/min/100g | 0.20 (0.15;0.26) | 0.27 (0.20;0.35) 4,5‡ | 0.23 (0.14;0.30) | 0.19 (0.16;0.23) | 0.19 (0.16;0.25) |

| Urinary albumin/ creatinine, mg/mg | 0.026 (0.017;0.035)3-5# | 0.043 (0.031;0.065)3-5‡ | 0.288 (0.237;0.336) | 0.327 (0.153-0.370) | 0.543 (0.345;1.114) |

| Renal interstitial fibrosis, % | 2.5 (1.6;3.1)3-5# | 1.9 (0.1;3.3)3-5# | 5.8 (3.5;7.2)5# | 6.9 (3.9;7.7)5# | 14.5 (13.2;17.2) |

| Serum Klotho, pg/ml | 2698 (2413;2831) |

2916 (2520;5374)3-5* |

2043 (1676;2663) |

2304 (2074;2524) | 2259 (1428;2696) |

| Serum inorganic phosphate, mmol/L | 1.47 (1.22-1.60)3-5# | 1.89 (1.79;1.95)5* | 1.90 (1.80;1.98)5‡ | 1.60 (1.50;1.84)5* | 2.21 (2.15;2.28) |

| Urinary phosphate/ creatinine, mg/mg | 5.6 (4.5;6.5)5* | 8.9 (6.9;10.1) | 8.6 (7.9;9.8) | 10.1 (7.6;12.7) | 9.3 (8.9;11.2) |

| Bone phosphorus, g/kg | 58.6 (33.4;62.7) | 63.5 (58.1;64.5) | 62.8 (61.8;64.1) | 62.8 (55.2;65.6) | 59.7 (58.9;63.6) |

| Kidney phosphorus, mg/kg | 818.6 (770.5;877.4) |

872.0 (606.7;1241.5) | 822.9 (637.7;1024.4) | 699.9 (668.1;825.9) | 734.2 (671.1;862.1) |

| Intact parathyroid hormone, pg/ml | 55.1(12.7;112.9) | 76.6 (18.4;111.0) | 45.5 (12.6;67.1) | 45.9 (21.2;76.6) | 33.5 (9.6;84.9) |

| Intact fibroblast growth factor 23, pg/ml | 351.9 (290.1;836.7) | 361.7 (330.8;1530.3) | 468.0 (326.9;694.9) | 676.0 (330.9;793.7) | 630.7 (330.8;953.1) |

2.1.2. Phosphate and its regulators

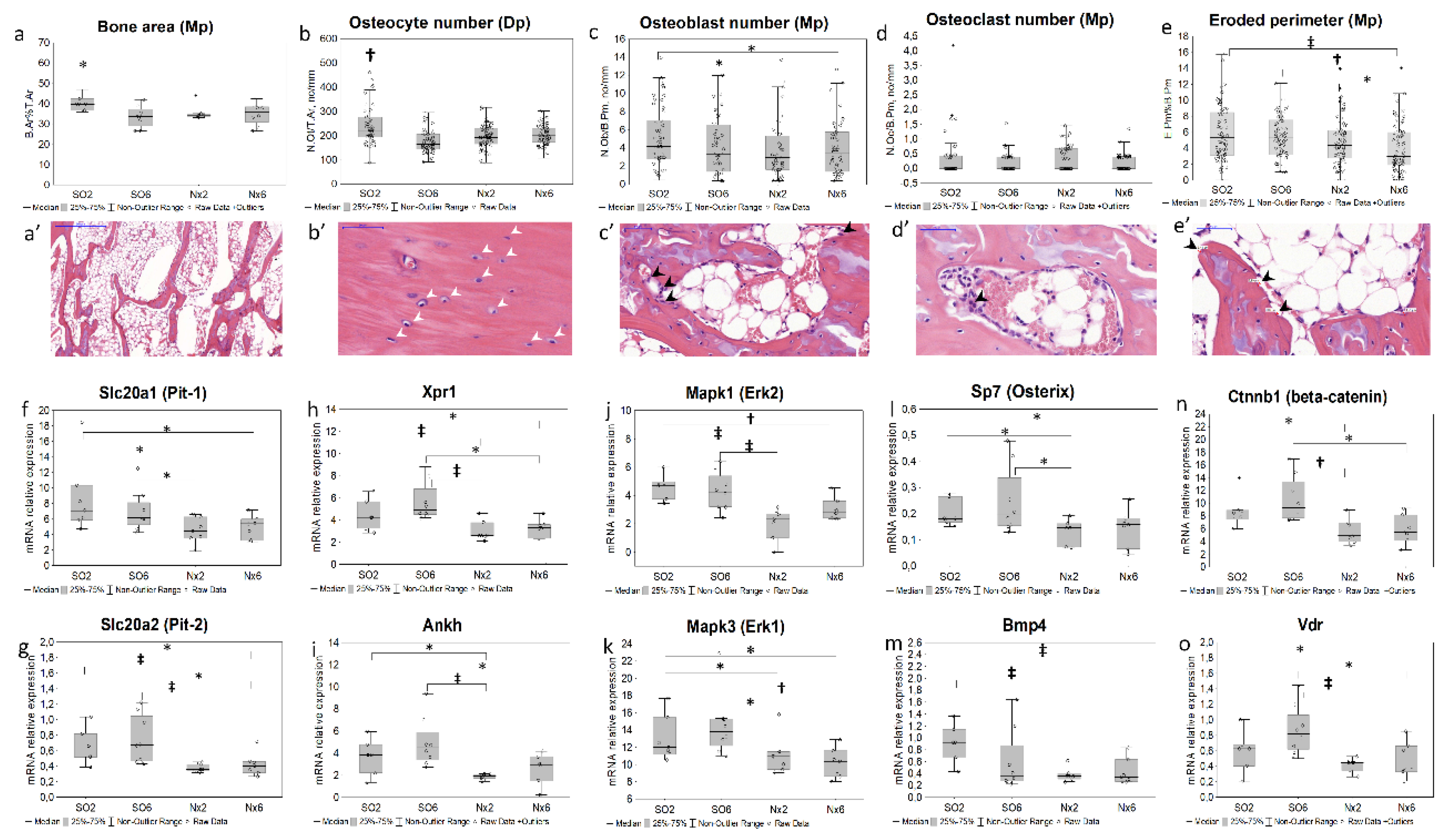

2.1.3. Static bone histomorphometry

2.2. Bone gene expression in mild chronic kidney disease models

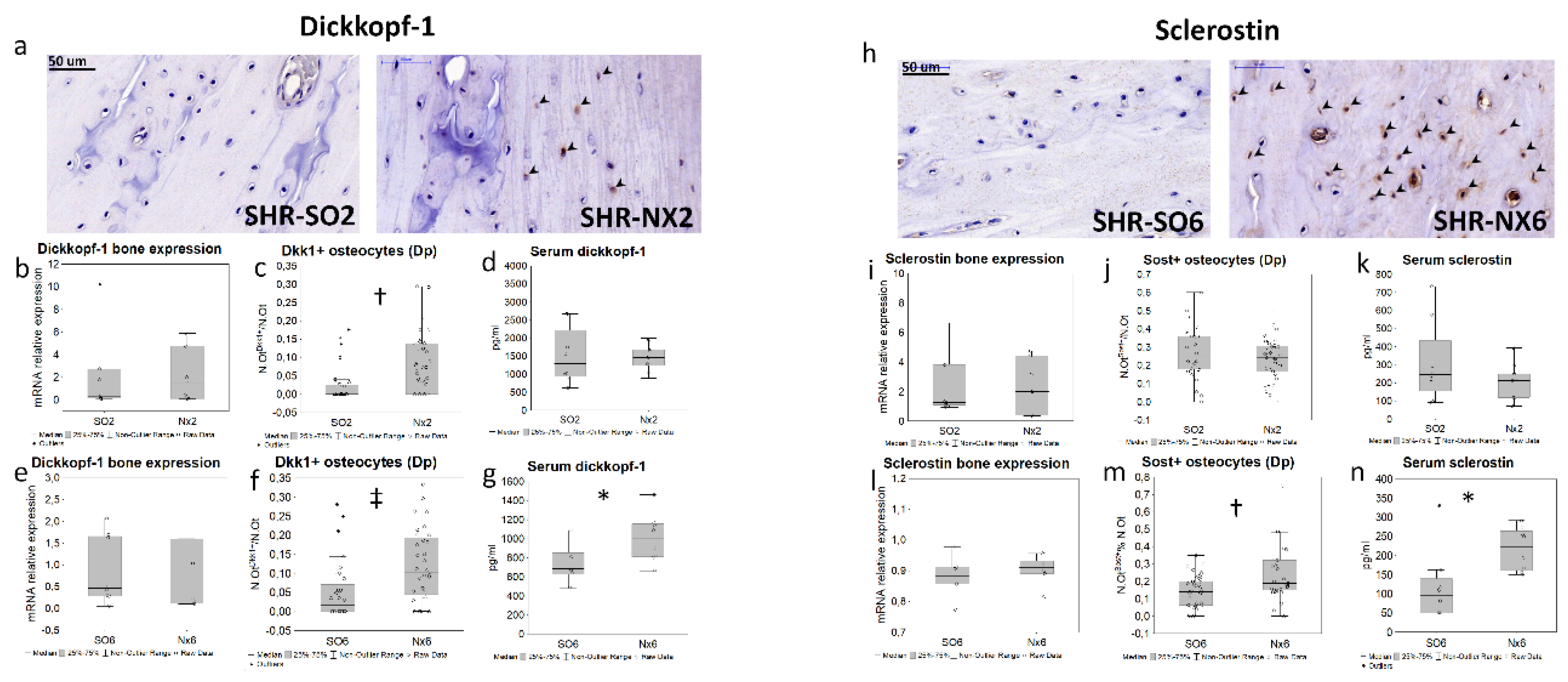

2.3. Bone immunohistochemistry in mild chronic kidney disease models

3. Discussion

Research Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

Animals

Laboratory measurements

Inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Quantitative morphometry

Statistical analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hruska, K.A.; Mathew, S.; Lund, R. Hyperphosphatemia of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2008, 74, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drüeke, T.B.; Massy, Z.A. Changing bone patterns with progression of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2016, 89, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.W.; Xu, C.; Fan, Y. Can serum levels of alkaline phosphatase and phosphate predict cardiovascular diseases and total mortality in individuals with preserved renal function? A systemic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bricker, N.S.; Morrin, P.A.; Kime, S.W. Jr. The pathologic physiology of chronic Bright's disease. An exposition of the "intact nephron hypothesis". Am J Med 1960, 28, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isakova, T.; Wolf, M.S. FGF23 or PTH: which comes first in CKD? Kidney Int 2010, 78, 947–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, Y.; Graciolli, F.G.; O'Brien, S. Repression of osteocyte Wnt/β-catenin signaling is an early event in the progression of renal osteodystrophy. J Bone Miner Res 2012, 27, 1757–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbs, J.R.; He, N.; Idiculla, A. Longitudinal evaluation of FGF23 changes and mineral metabolism abnormalities in a mouse model of chronic kidney disease. J Bone Miner Res 2012, 27, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, J.C.; Ferrari, G.O.; Neves, K.R. Effects of dietary phosphate on adynamic bone disease in rats with chronic kidney disease--role of sclerostin? PLoS One 2013, 8, e79721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-López, N.; Martínez-Arias, L.; Fernández-Villabrille, S. Role of the RANK/RANKL/OPG and Wnt/β-Catenin Systems in CKD Bone and Cardiovascular Disorders. Calcif Tissue Int 2021, 108, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moe, S.M.; Radcliffe, J.S.; White, K.E. The pathophysiology of early-stage chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD) and response to phosphate binders in the rat. J Bone Miner Res 2011, 26, 2672–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, S.; Lund, R.J.; Strebeck, F. Reversal of the adynamic bone disorder and decreased vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease by sevelamer carbonate therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007, 18, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki-Ishizuka, Y.; Yamato, H.; Nii-Kono, T. Downregulation of parathyroid hormone receptor gene expression and osteoblastic dysfunction associated with skeletal resistance to parathyroid hormone in a rat model of renal failure with low turnover bone. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005, 20, 1904–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Ginsberg, C.; Seifert, M. CKD-induced wingless/integration1 inhibitors and phosphorus cause the CKD-mineral and bone disorder. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014, 25, 1760–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnusson, P.; Sharp, C.A.; Magnusson, M. Effect of chronic renal failure on bone turnover and bone alkaline phosphatase isoforms. Kidney Int 2001, 60, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickolas, T.L.; Stein, E.M.; Dworakowski, E. Rapid cortical bone loss in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Bone Miner Res 2013, 28, 1811–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasnim, N.; Dutta, P.; Nayeem, J. Osteoporosis, an Inevitable Circumstance of Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2021, 13, e18488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malluche, H.H.; Ritz, E.; Lange, H.P. Bone histology in incipient and advanced renal failure. Kidney Int 1976, 9, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, G.; Mazzaferro, S.; Ballanti, P. Renal bone disease in 76 patients with varying degrees of predialysis chronic renal failure: a cross-sectional study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996, 11, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, F.C.; Barreto, D.V.; Canziani, M.E. Association between indoxyl sulfate and bone histomorphometry in pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients. J Bras Nefrol 2014, 36, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciolli, F.G.; Neves, K.R.; Barreto, F. The complexity of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder across stages of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2017, 91, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misof, B.M.; Blouin, S.; Roschger, P. Bone matrix mineralization and osteocyte lacunae characteristics in patients with chronic kidney disease - mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD). J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2019, 19, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fleischer, H.; Vorberg, E.; Thurow, K. et al. Determination of Calcium and Phosphor in Bones Using Microwave Digestion and ICP-MS. 5th IMEKO TC19 SYMPOSIUM, ISBN, 978-92-990073-6-5.

- Erben, R.G.; Glösmann, M. (2019). Histomorphometry in Rodents. In, pp. Idris, A. (eds) Bone Research Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology, vol 1914. Humana Press, New York, NY.

- Dempster, D.W.; Compston, J.E.; Drezner, M.K. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res 2013, 28, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.W.; Huang, T.H.; Chang, Y.H. Exercise Alleviates Osteoporosis in Rats with Mild Chronic Kidney Disease by Decreasing Sclerostin Production. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, H.S.; Behets, G.; Viaene, L. Static histomorphometry allows for a diagnosis of bone turnover in renal osteodystrophy in the absence of tetracycline labels. Bone 2021, 152, 116066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzger, C.E.; Swallow, E.A.; Stacy, A.J.; Allen, M.R. Strain-specific alterations in the skeletal response to adenine-induced chronic kidney disease are associated with differences in parathyroid hormone levels. Bone 2021, 148, 115963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshikawa, S.; Shimizu, K.; Watahiki, A. Phosphorylation-dependent osterix degradation negatively regulates osteoblast differentiation. FASEB J 2020, 34, 14930–14945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iezaki, T.; Onishi, Y. , Ozaki, K. et al. The Transcriptional Modulator Interferon-Related Developmental Regulator 1 in Osteoblasts Suppresses Bone Formation and Promotes Bone Resorption. J Bone Miner Res 2016, 31, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, K.; Sakikawa, C.; Katsumata, M. Platelet-derived growth factor BB secreted from osteoclasts acts as an osteoblastogenesis inhibitory factor. J Bone Miner Res. 2002, 17, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.W.; Park, J.; Habib, M.M.; Beck, G.R. Jr. Nano-Hydroxyapatite Stimulation of Gene Expression Requires Fgf Receptor, Phosphate Transporter, and Erk1/2 Signaling. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2017, 9, 39185–39196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bon, N.; Couasnay, G.; Bourgine, A. Phosphate (Pi)-regulated heterodimerization of the high-affinity sodium-dependent Pi transporters PiT1/Slc20a1 and PiT2/Slc20a2 underlies extracellular Pi sensing independently of Pi uptake. J Biol Chem 2018, 293, 2102–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dussold, C.; Gerber, C.; White, S. DMP1 prevents osteocyte alterations, FGF23 elevation and left ventricular hypertrophy in mice with chronic kidney disease. Bone Res 2019, 7, p12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camalier, C.E.; Yi, M.; Yu, L.R. An integrated understanding of the physiological response to elevated extracellular phosphate. J Cell Physiol 2013, 228, 1536–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Luo, F.; Wang, Q. Inducible Activation of FGFR2 in Adult Mice Promotes Bone Formation After Bone Marrow Ablation. J Bone Miner Res 2017, 32, 2194–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, S.; Wallingford, M.C.; Borgeia, S. Loss of PiT-2 results in abnormal bone development and decreased bone mineral density and length in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 495, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albano, G.; Moor, M.; Dolder, S. Sodium-dependent phosphate transporters in osteoclast differentiation and function. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0125104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannini, D.; Touhami, J.; Charnet, P.; Sitbon, M.; Battini, J.L. Inorganic phosphate export by the retrovirus receptor XPR1 in metazoans. Cell Rep 2013, 3, 1866–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szeri, F.; Niaziorimi, F.; Donnelly, S. The Mineralization Regulator ANKH Mediates Cellular Efflux of ATP, Not Pyrophosphate. J Bone Miner Res 2022, 37, 1024–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, L.; Beck-Cormier, S. Extracellular phosphate sensing in mammals: what do we know? J Mol Endocrinol 2020, 65, R53–R63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).