Submitted:

07 February 2023

Posted:

09 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Administration of Neither LTG nor LCM at Anticonvulsant Doses Delays Kindling Acquistion

2.2. Administration of either LTG or LCM at Anticonvulsant doses During Kindling Reduces Subsequent Kindled Seizure Cross-Sensitivity

2.3. Administration of either LTG or LCM at Anticonvulsant doses During Kindling Leads to Significant Drug-Resistance Across a Range of ASMs with Diverse Mechanims

| ASM | Acute Low and High Doses Tested (mg/kg, i.p.) | VEH-Kindled Mice (N protected/F tested) | LTG-Kindled Mice (N protected/F tested) | LCM-Kindled Mice (N protected/F tested) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Dose | High Dose | Low Dose | High Dose | Low Dose | High Dose | ||

| LTG | 17; 50 | 2/8 | 7/8 | 2/8 | 2/8 | 1/8 | 1/8 |

| LCM | 9; 26.5 | 3/8 | 4/8 | 0/8 | 3/8 | 2/8 | 3/8 |

| LEV | 60; 180 | 7/8 | 7/8 | 6/8 | 7/8 | 6/8 | 5/8 |

| GBP | 75; 300 | 2/8 | 6/8 | 3/8 | 5/8 | 3/8 | 5/8 |

| PER | 1; 4 | 6/8 | 8/8 | 3/8 | 7/8 | 1/8 | 6/8 |

| VPA | 75; 300 | 4/8 | 7/8 | 3/8 | 5/8 | 2/8 | 5/8 |

| PB | 15; 45 | 7/8 | 7/8 | 3/8 | 4/8 | 2/8 | 4/8 |

| CBZ | 10; 40 | 5/8 | 7/8 | 1/8 | 3/8 | 1/8 | 2/8 |

| TPM | 8; 20 | 1/8 | 0/8 | 1/8 | 0/8 | 1/7 | 2/8 |

2.4. LTG Administration during Corneal Kindling Blunts Chronic Seizure-Induced Increases in Reactive Gliosis in Area CA1 of Dorsal Hippocampus

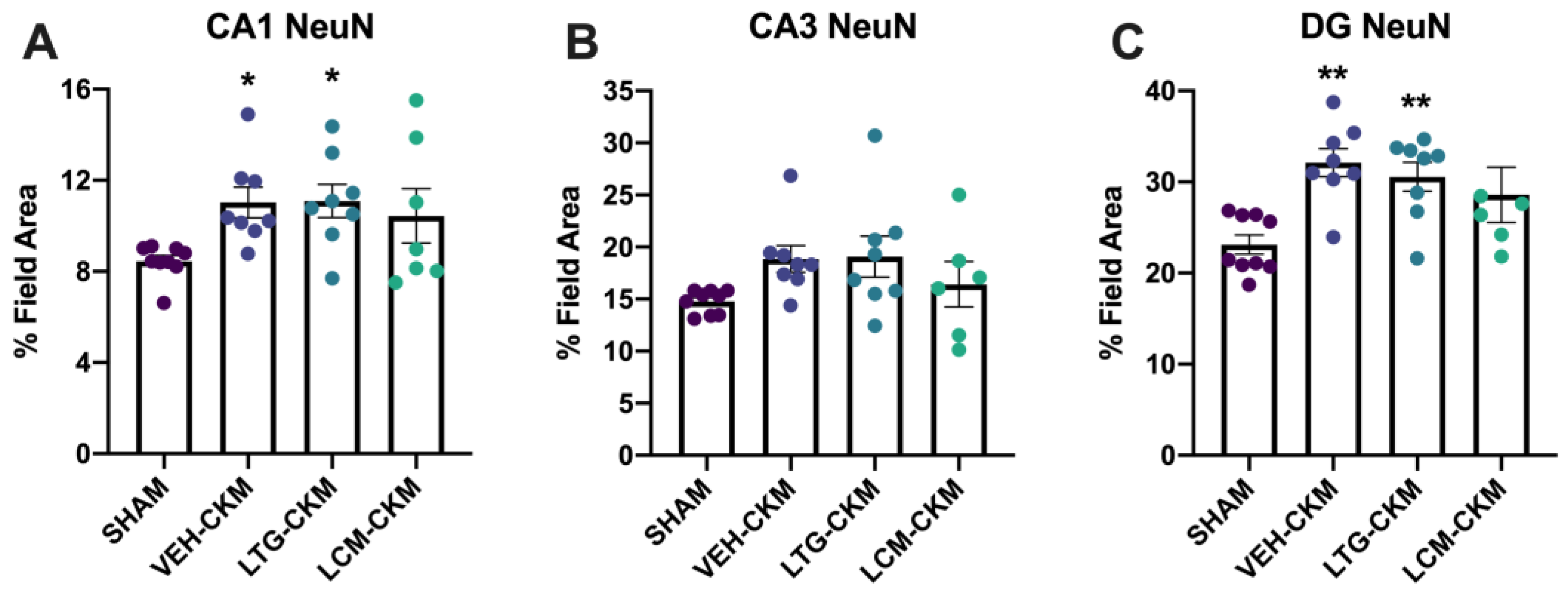

2.5. LCM Administration during Corneal Kindling Blunts Chronic Seizure-Induced Increases in Neuronal Density in Dorsal Hippocampus

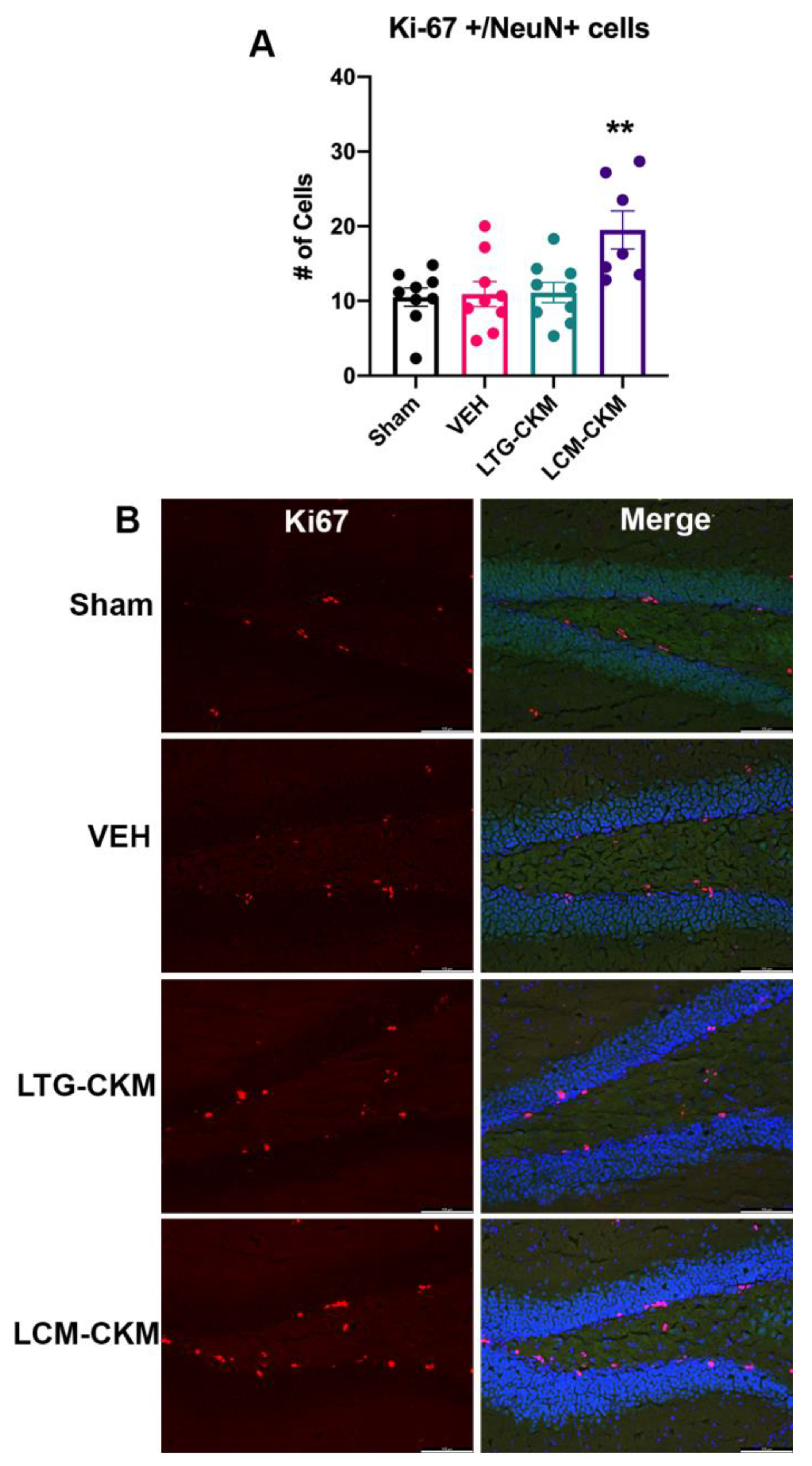

2.6. LCM Administration during Corneal Kindling is Associated with Increased Neurogenesis in Dentate Gyrus

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, F.; Hartz, A.M.S.; Bauer, B. Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: Multiple Hypotheses, Few Answers. Front Neurol 2017, 8, 301. [CrossRef]

- Matagne, A.; Klitgaard, H. Validation of corneally kindled mice: a sensitive screening model for partial epilepsy in man. Epilepsy research 1998, 31, 59-71. [CrossRef]

- Klitgaard, H.; Matagne, A.; Gobert, J.; Wulfert, E. Evidence for a unique profile of levetiracetam in rodent models of seizures and epilepsy. Eur J Pharmacol 1998, 353, 191-206.

- Barker-Haliski, M.L.; Johnson, K.; Billingsley, P.; Huff, J.; Handy, L.J.; Khaleel, R.; Lu, Z.; Mau, M.J.; Pruess, T.H.; Rueda, C.; et al. Validation of a Preclinical Drug Screening Platform for Pharmacoresistant Epilepsy. Neurochemical research 2017, 42, 1904-1918. [CrossRef]

- Kehne, J.H.; Klein, B.D.; Raeissi, S.; Sharma, S. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Epilepsy Therapy Screening Program (ETSP). Neurochemical research 2017. [CrossRef]

- Barker-Haliski, M.L.; Vanegas, F.; Mau, M.J.; Underwood, T.K.; White, H.S. Acute cognitive impact of antiseizure drugs in naive rodents and corneal-kindled mice. Epilepsia 2016, 57, 1386-1397. [CrossRef]

- Remigio, G.J.; Loewen, J.L.; Heuston, S.; Helgeson, C.; White, H.S.; Wilcox, K.S.; West, P.J. Corneal kindled C57BL/6 mice exhibit saturated dentate gyrus long-term potentiation and associated memory deficits in the absence of overt neuron loss. Neurobiology of disease 2017, 105, 221-234. [CrossRef]

- Koneval, Z.; Knox, K.M.; White, H.S.; Barker-Haliski, M. Lamotrigine-resistant corneal-kindled mice: A model of pharmacoresistant partial epilepsy for moderate-throughput drug discovery. Epilepsia 2018, 59, 1245-1256. [CrossRef]

- Loewen, J.L.; Barker-Haliski, M.L.; Dahle, E.J.; White, H.S.; Wilcox, K.S. Neuronal Injury, Gliosis, and Glial Proliferation in Two Models of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology 2016, 75, 366-378. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K.; White, H.S. Carbamazepine, but not valproate, displays pharmacoresistance in lamotrigine-resistant amygdala kindled rats. Epilepsy research 2013, 104, 26-34. [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, C.S.; Huff, J.; Thomson, K.E.; Johnson, K.; Edwards, S.F.; Wilcox, K.S. Evaluation of antiseizure drug efficacy and tolerability in the rat lamotrigine-resistant amygdala kindling model. Epilepsia Open 2019, 4, 452-463. [CrossRef]

- Sutula, T.P.; Kotloski, R.J. Kindling: A Model and Phenomenon of Epilepsy. In Models of Seizure and Epilepsy, 2nd ed.; Pitkanen, A., Buckmaster, P.S., Galanopoulou, A.S., Moshe, S.L., Eds.; Academic Press: 2017; pp. 813-825.

- Sutula, T.P. Secondary epileptogenesis, kindling, and intractable epilepsy: a reappraisal from the perspective of neural plasticity. Int Rev Neurobiol 2001, 45, 355-386.

- Pawluski, J.L.; Kuchenbuch, M.; Hadjadj, S.; Dieuset, G.; Costet, N.; Vercueil, L.; Biraben, A.; Martin, B. Long-term negative impact of an inappropriate first antiepileptic medication on the efficacy of a second antiepileptic medication in mice. Epilepsia 2018, 59, e109-e113. [CrossRef]

- Jandova, K.; Pasler, D.; Antonio, L.L.; Raue, C.; Ji, S.; Njunting, M.; Kann, O.; Kovacs, R.; Meencke, H.J.; Cavalheiro, E.A.; et al. Carbamazepine-resistance in the epileptic dentate gyrus of human hippocampal slices. Brain : a journal of neurology 2006, 129, 3290-3306. [CrossRef]

- Kilkenny, C.; Browne, W.; Cuthill, I.C.; Emerson, M.; Altman, D.G.; Group, N.C.R.R.G.W. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. J Gene Med 2010, 12, 561-563. [CrossRef]

- Sills, G.J.; Rogawski, M.A. Mechanisms of action of currently used antiseizure drugs. Neuropharmacology 2020, 168, 107966. [CrossRef]

- Brandt, C.; Heile, A.; Potschka, H.; Stoehr, T.; Loscher, W. Effects of the novel antiepileptic drug lacosamide on the development of amygdala kindling in rats. Epilepsia 2006, 47, 1803-1809. [CrossRef]

- Stohr, T.; Kupferberg, H.J.; Stables, J.P.; Choi, D.; Harris, R.H.; Kohn, H.; Walton, N.; White, H.S. Lacosamide, a novel anti-convulsant drug, shows efficacy with a wide safety margin in rodent models for epilepsy. Epilepsy research 2007, 74, 147-154. [CrossRef]

- Koneval, Z.; Knox, K.; Memon, A.; Zierath, D.K.; White, H.S.; Barker-Haliski, M. Antiseizure drug efficacy and tolerability in established and novel drug discovery seizure models in outbred versus inbred mice. Epilepsia 2020, In press.

- Florek-Luszczki, M.; Zagaja, M.; Luszczki, J.J. Influence of WIN 55,212-2 on the anticonvulsant and acute neurotoxic potential of clobazam and lacosamide in the maximal electroshock-induced seizure model and chimney test in mice. Epilepsy research 2014, 108, 1728-1733. [CrossRef]

- Rowley, N.M.; White, H.S. Comparative anticonvulsant efficacy in the corneal kindled mouse model of partial epilepsy: Correlation with other seizure and epilepsy models. Epilepsy research 2010, 92, 163-169.

- Knox, K.M.; Beckman, M.; Smith, C.L.; Jayadev, S.; Barker-Haliski, M. Chronic seizures induce sex-specific cognitive deficits with loss of presenilin 2 function. Experimental neurology 2023, 114321. [CrossRef]

- Kee, N.; Sivalingam, S.; Boonstra, R.; Wojtowicz, J.M. The utility of Ki-67 and BrdU as proliferative markers of adult neurogenesis. J Neurosci Methods 2002, 115, 97-105. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Brodie, M.J.; Liew, D.; Kwan, P. Treatment Outcomes in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Epilepsy Treated With Established and New Antiepileptic Drugs: A 30-Year Longitudinal Cohort Study. JAMA Neurol 2018, 75, 279-286. [CrossRef]

- Kwan, P.; Brodie, M.J. Epilepsy after the first drug fails: substitution or add-on? Seizure 2000, 9, 464-468. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Goel, R.K. Pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and neurochemical investigations of lamotrigine-pentylenetetrazole kindled mice to ascertain it as a reliable model for clinical drug-resistant epilepsy. Animal Model Exp Med 2020, 3, 245-255. [CrossRef]

- Remy, S.; Beck, H. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of pharmacoresistance in epilepsy. Brain : a journal of neurology 2006, 129, 18-35. [CrossRef]

- Brandt, C.; Bethmann, K.; Gastens, A.M.; Loscher, W. The multidrug transporter hypothesis of drug resistance in epilepsy: Proof-of-principle in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiology of disease 2006, 24, 202-211. [CrossRef]

- Rogawski, M.A.; Johnson, M.R. Intrinsic severity as a determinant of antiepileptic drug refractoriness. Epilepsy currents / American Epilepsy Society 2008, 8, 127-130. [CrossRef]

- Thomson, K.E.; Modi, A.; Glauser, T.A.; White, H.S. The Impact of Nonadherence to Antiseizure Drugs on Seizure Outcomes in an Animal Model of Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2017, In Press.

- Kuo, C.C. A common anticonvulsant binding site for phenytoin, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine in neuronal Na+ channels. Molecular pharmacology 1998, 54, 712-721.

- Hebeisen, S.; Pires, N.; Loureiro, A.I.; Bonifacio, M.J.; Palma, N.; Whyment, A.; Spanswick, D.; Soares-da-Silva, P. Eslicarbazepine and the enhancement of slow inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels: a comparison with carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine and lacosamide. Neuropharmacology 2015, 89, 122-135. [CrossRef]

- Curia, G.; Biagini, G.; Perucca, E.; Avoli, M. Lacosamide: a new approach to target voltage-gated sodium currents in epileptic disorders. CNS drugs 2009, 23, 555-568. [CrossRef]

- Beyreuther, B.K.; Freitag, J.; Heers, C.; Krebsfanger, N.; Scharfenecker, U.; Stohr, T. Lacosamide: a review of preclinical properties. CNS Drug Rev 2007, 13, 21-42. [CrossRef]

- Remy, S.; Urban, B.W.; Elger, C.E.; Beck, H. Anticonvulsant pharmacology of voltage-gated Na+ channels in hippocampal neurons of control and chronically epileptic rats. Eur J Neurosci 2003, 17, 2648-2658.

- Catterall, W.A.; Kalume, F.; Oakley, J.C. NaV1.1 channels and epilepsy. J Physiol 2010, 588, 1849-1859. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Kao, T.; Horvath, Z.; Lemos, J.; Sul, J.Y.; Cranstoun, S.D.; Bennett, V.; Scherer, S.S.; Cooper, E.C. A common ankyrin-G-based mechanism retains KCNQ and NaV channels at electrically active domains of the axon. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2006, 26, 2599-2613. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Miyazaki, H.; Hoshi, N.; Smith, B.J.; Nukina, N.; Goldin, A.L.; Chandy, K.G. Modulation of voltage-gated K+ channels by the sodium channel beta1 subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 18577-18582. [CrossRef]

- Pisano, T.; Numis, A.L.; Heavin, S.B.; Weckhuysen, S.; Angriman, M.; Suls, A.; Podesta, B.; Thibert, R.L.; Shapiro, K.A.; Guerrini, R.; et al. Early and effective treatment of KCNQ2 encephalopathy. Epilepsia 2015, 56, 685-691. [CrossRef]

- Luna-Tortos, C.; Fedrowitz, M.; Loscher, W. Several major antiepileptic drugs are substrates for human P-glycoprotein. Neuropharmacology 2008, 55, 1364-1375. [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Zhang, Y.P.; Hou, Z.; Huang, C.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, C.Q.; Yin, Q. Novel Insights into NeuN: from Neuronal Marker to Splicing Regulator. Mol Neurobiol 2016, 53, 1637-1647. [CrossRef]

- Parent, J.M.; Lowenstein, D.H. Seizure-induced neurogenesis: are more new neurons good for an adult brain? Progress in brain research 2002, 135, 121-131. [CrossRef]

- Faught, E.; Helmers, S.; Thurman, D.; Kim, H.; Kalilani, L. Patient characteristics and treatment patterns in patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy: A US database analysis. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B 2018, 85, 37-44. [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, J.M.; Ridsdale, L.; Richardson, M.P.; Ashworth, M.; Gulliford, M.C. Trends in antiepileptic drug utilisation in UK primary care 1993-2008: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Seizure 2012, 21, 466-470. [CrossRef]

- Meeker, S.; Beckman, M.; Knox, K.M.; Treuting, P.M.; Barker-Haliski, M. Repeated Intraperitoneal Administration of Low-Concentration Methylcellulose Leads to Systemic Histologic Lesions Without Loss of Preclinical Phenotype. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 2019. [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.; Zeigler, M.; Mizuno, S.; Morrison, R.S.; Totah, R.A.; Barker-Haliski, M. Reductions in Hydrogen Sulfide and Changes in Mitochondrial Quality Control Proteins Are Evident in the Early Phases of the Corneally Kindled Mouse Model of Epilepsy. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Barker-Haliski, M.L.; Oldenburger, K.; Keefe, K.A. Disruption of subcellular Arc/Arg 3.1 mRNA expression in striatal efferent neurons following partial monoamine loss induced by methamphetamine. Journal of neurochemistry 2012, 123, 845-855. [CrossRef]

- Knox, K.M.; Zierath, D.K.; White, H.S.; Barker-Haliski, M. Continuous seizure emergency evoked in mice with pharmacological, electrographic, and pathological features distinct from status epilepticus. Epilepsia 2021. [CrossRef]

| Dose (mg/kg, i.p.) | Protected (N/F) | Motor Impairment (T/F) |

| 2.5 | 1/8 | 0/8 |

| 3 | 1/16 | 0/16 |

| 4 | 5/15 | 0/15 |

| 5 | 8/8 | 0/8 |

| 10 | 8/8 | 0/8 |

| 15 | 8/8 | 0/8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).