Submitted:

06 February 2023

Posted:

06 February 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

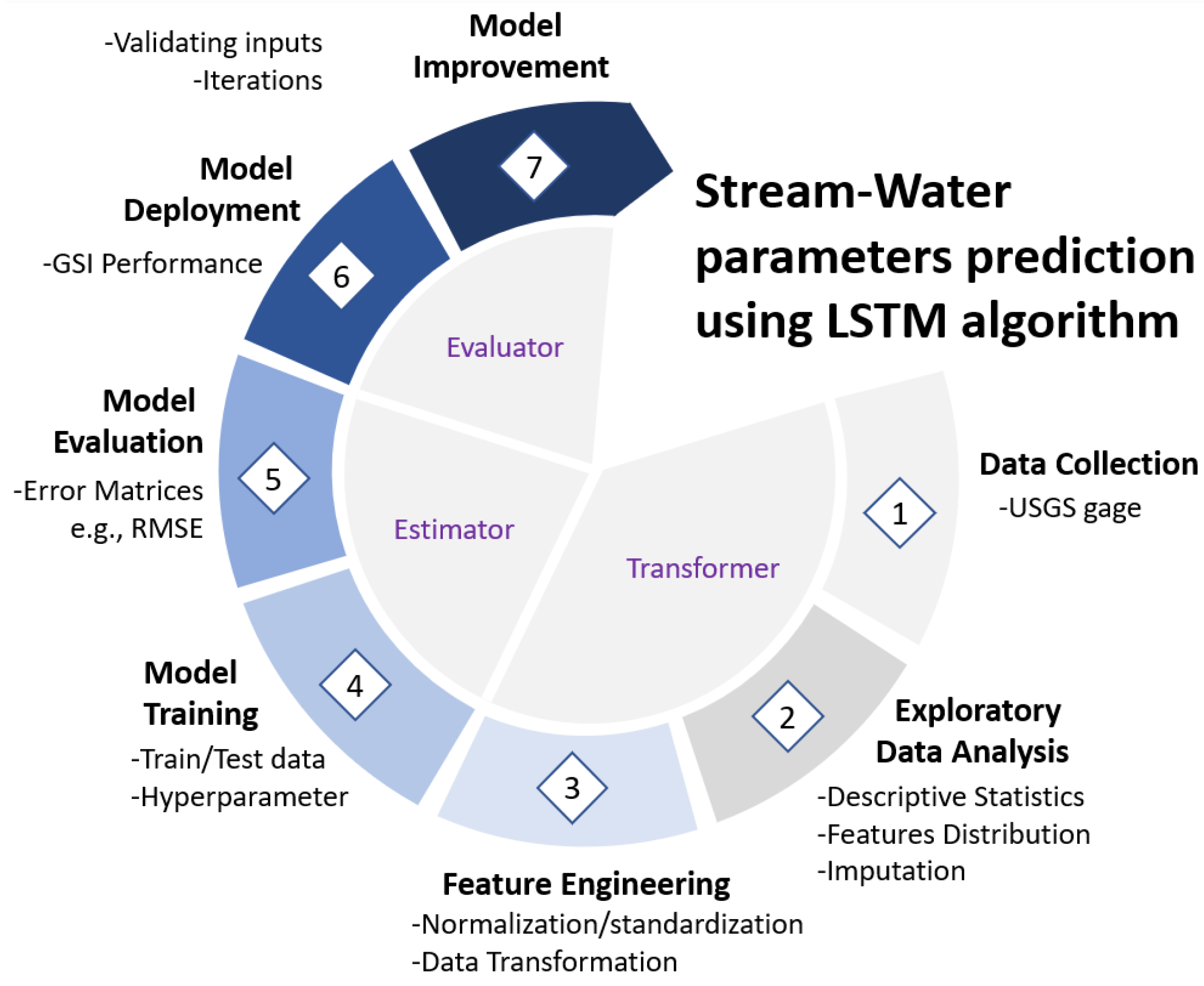

2. Data and Methods

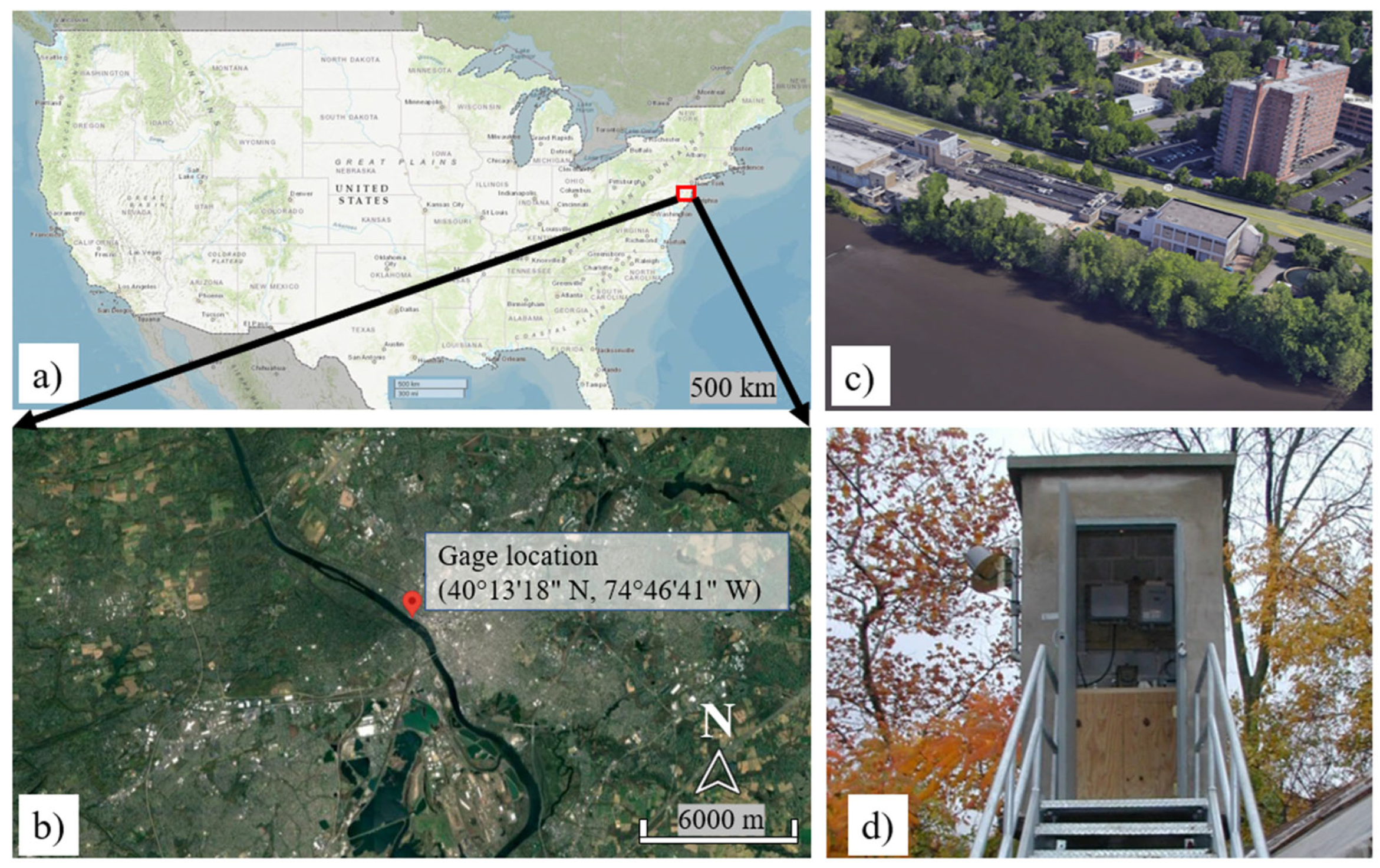

2.1. Study Location and Workflow

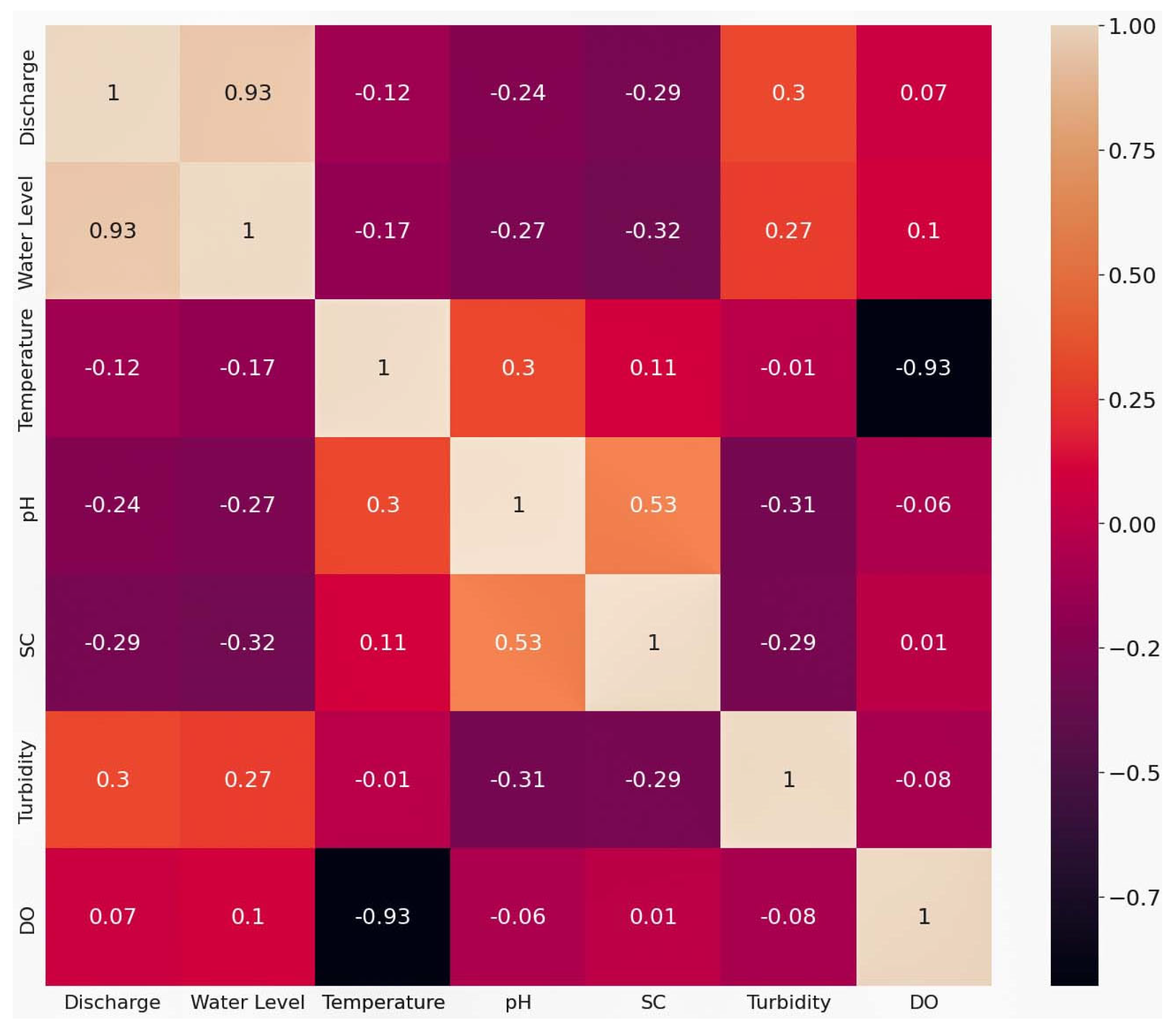

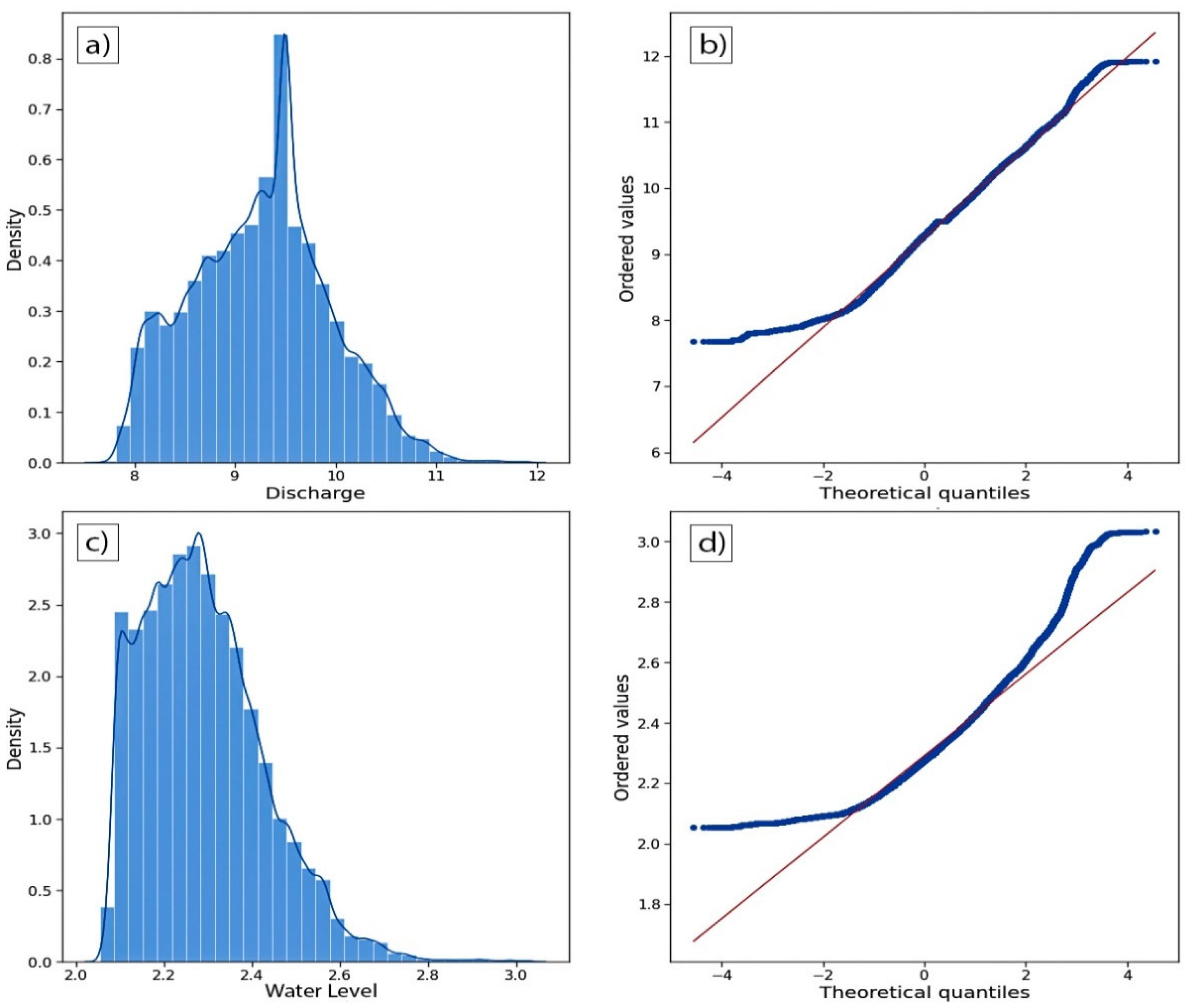

2.2. Multivariate Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

2.3. Feature Engineering (FE)

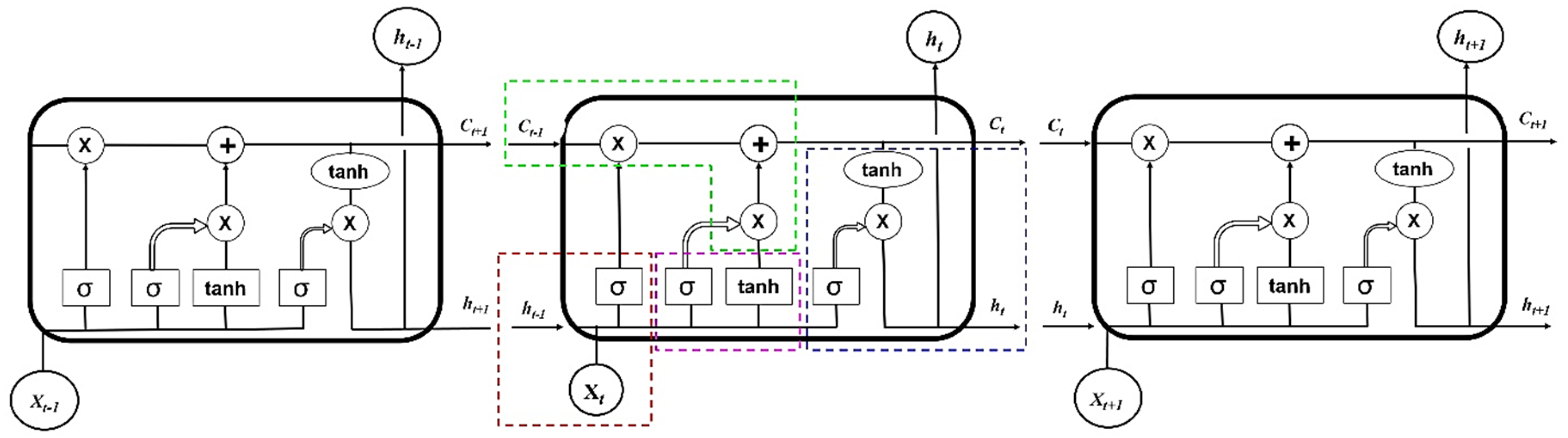

2.4. Long Short-term Memory (LSTM) Recurrent Neural

2.5. Model Evaluation and improvement

3. Results and Discussion

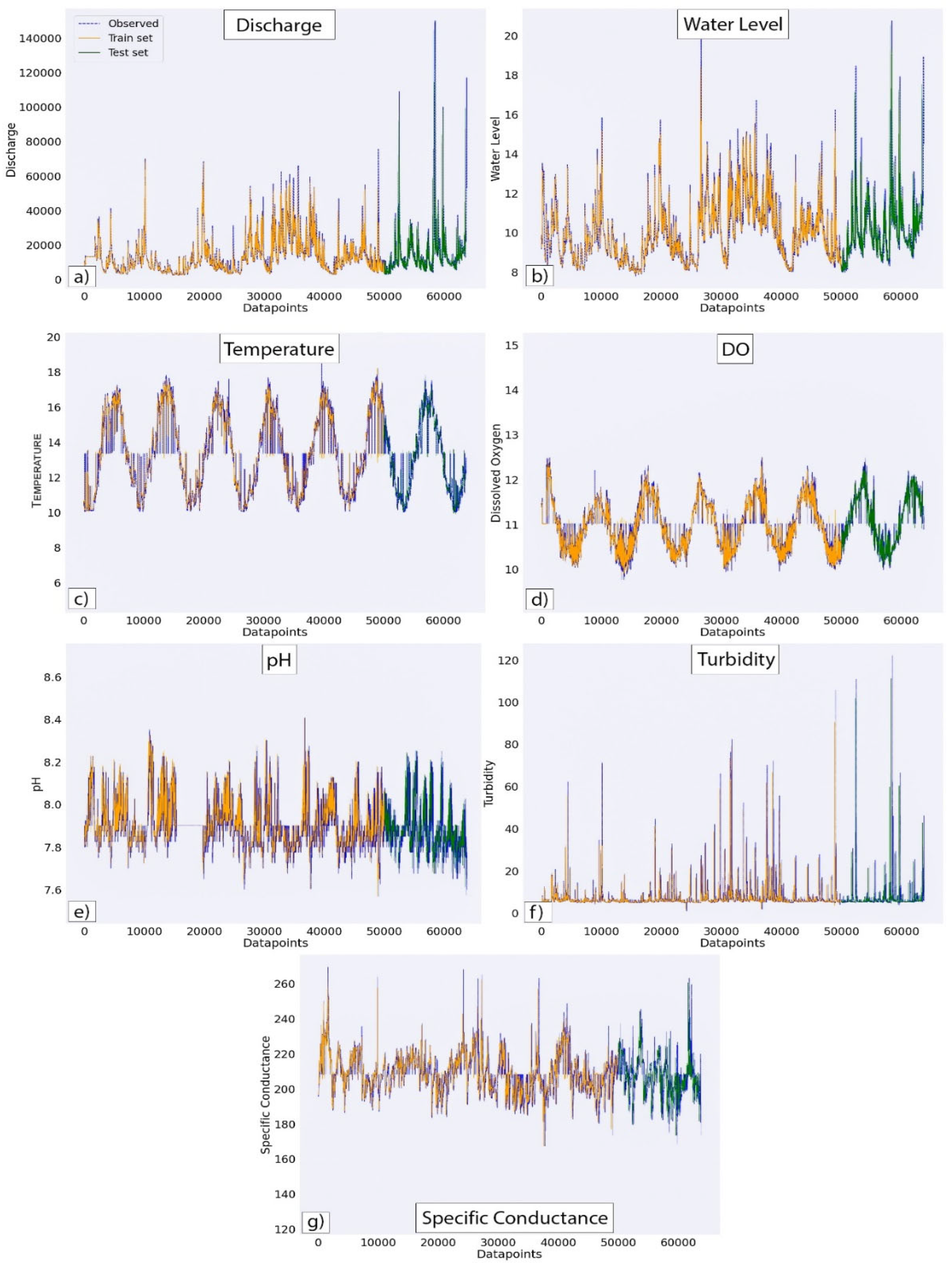

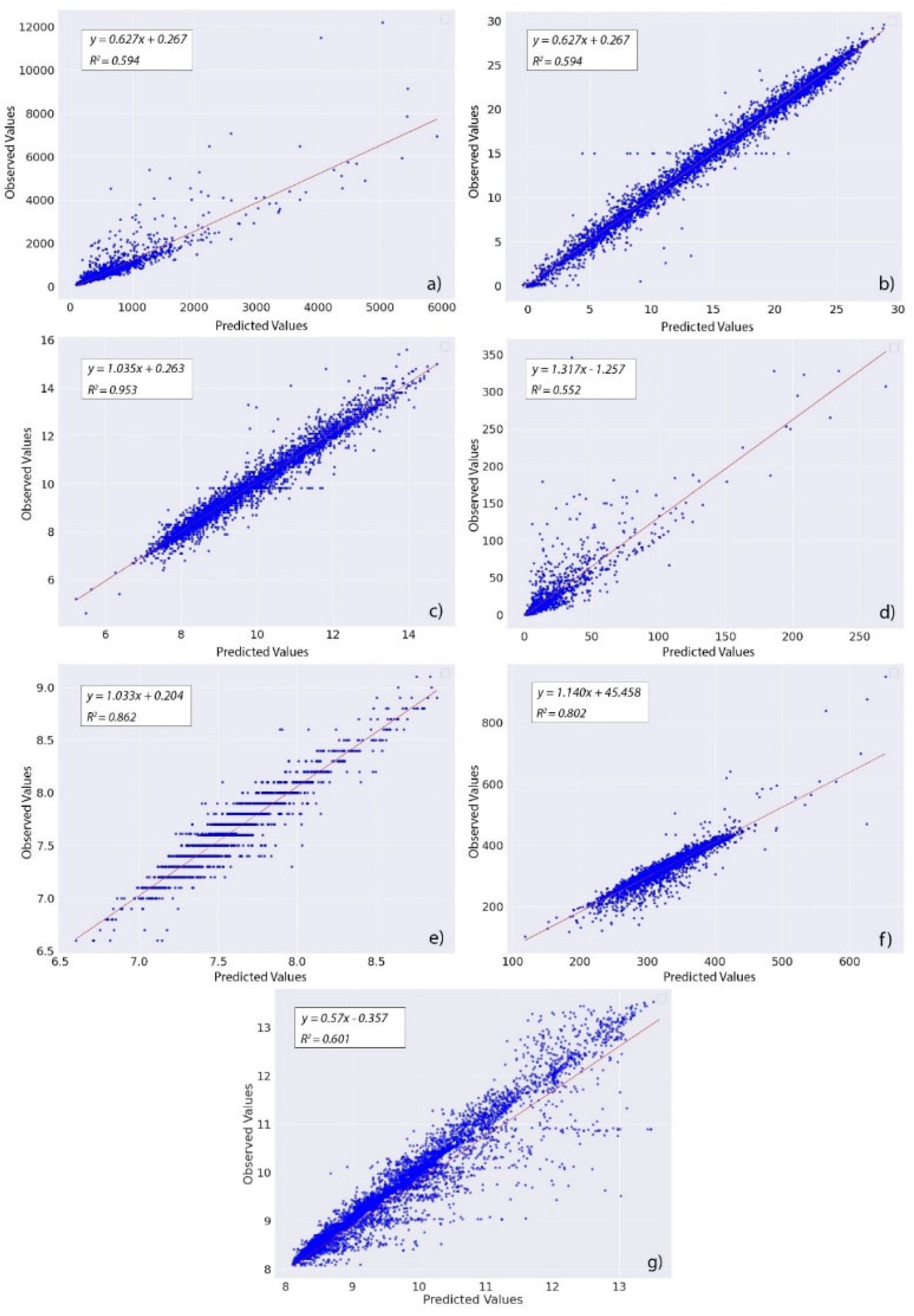

3.1. Predicted and Observed SW variables

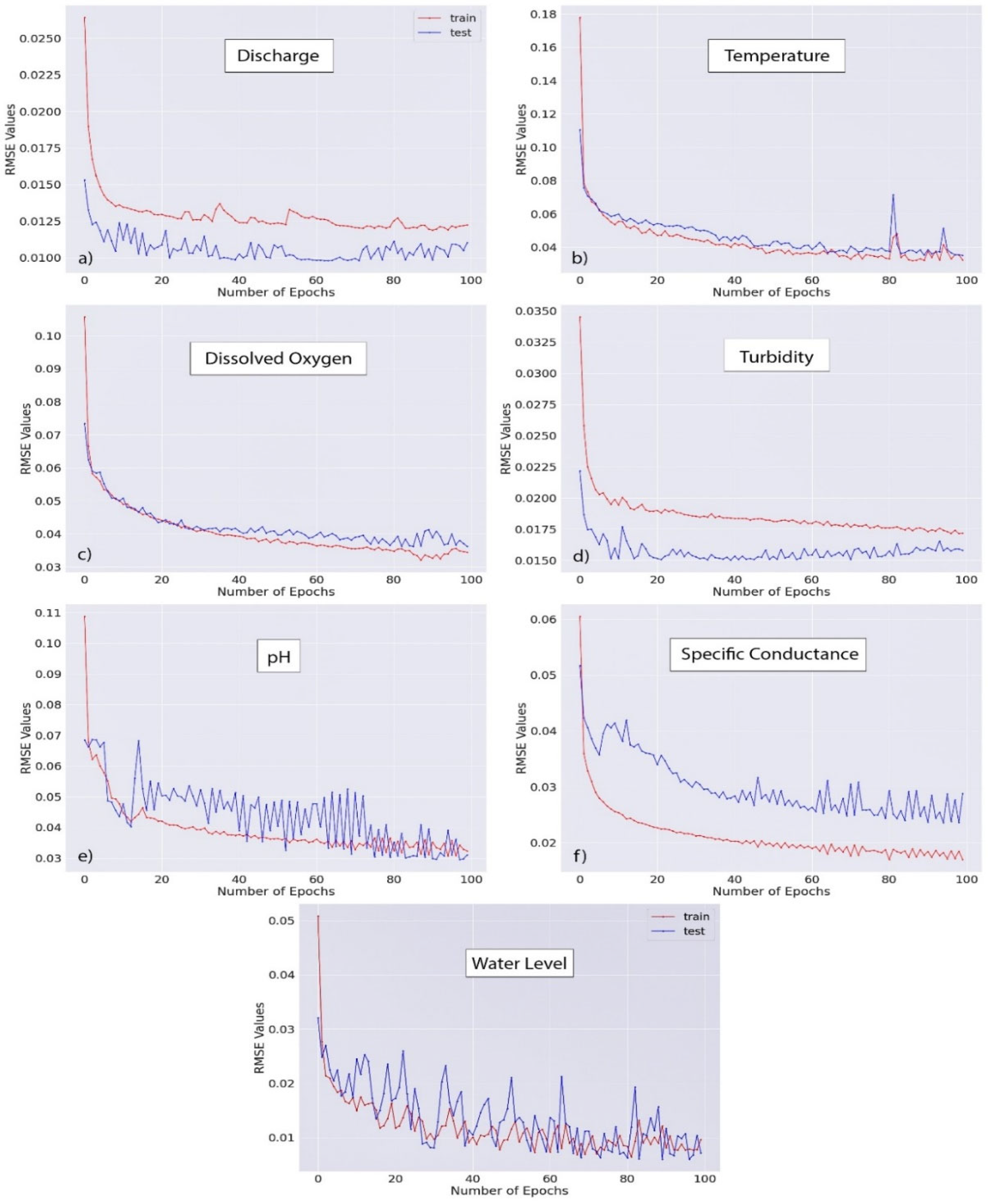

3.1. Model Evaluation Matrices and Improvement

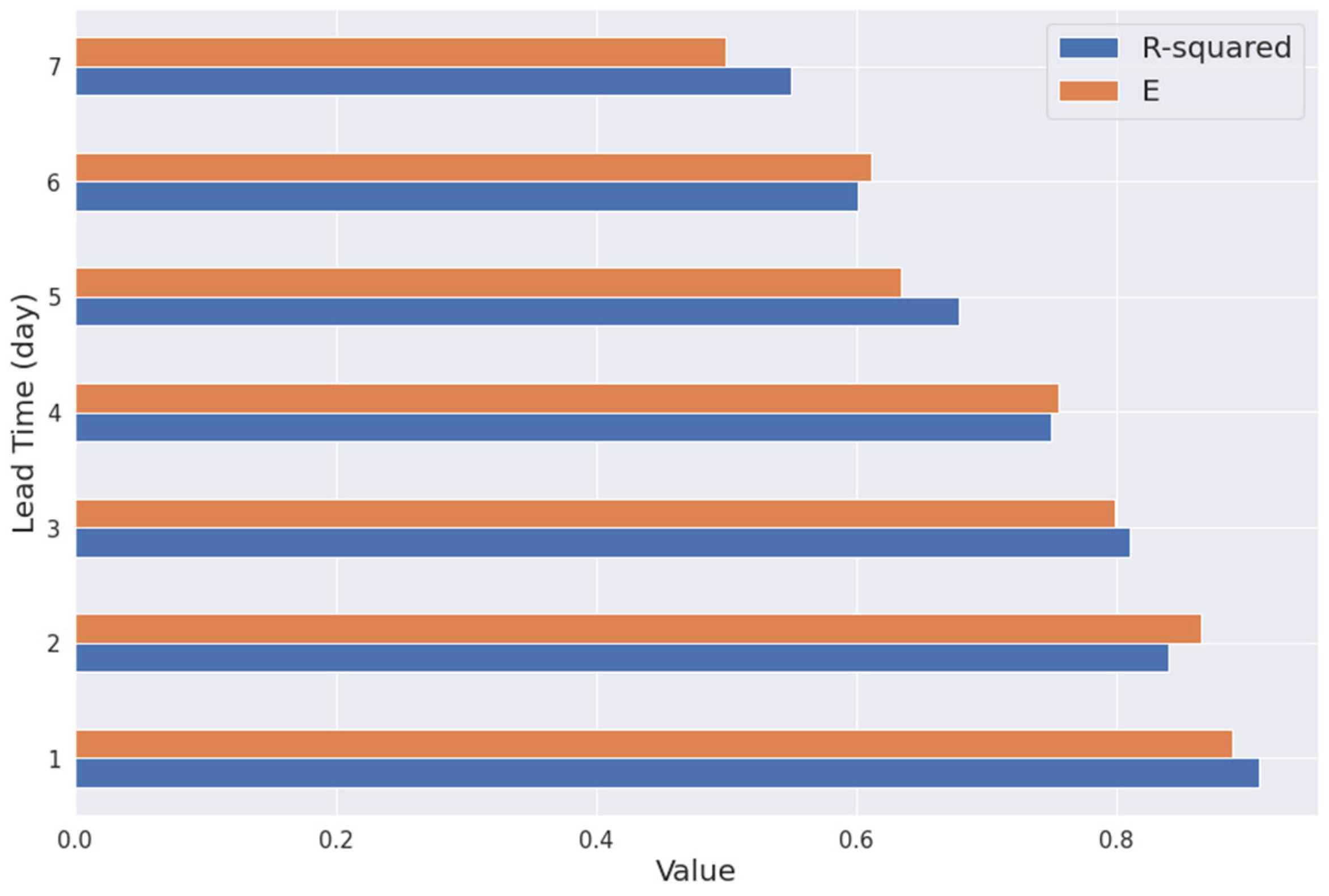

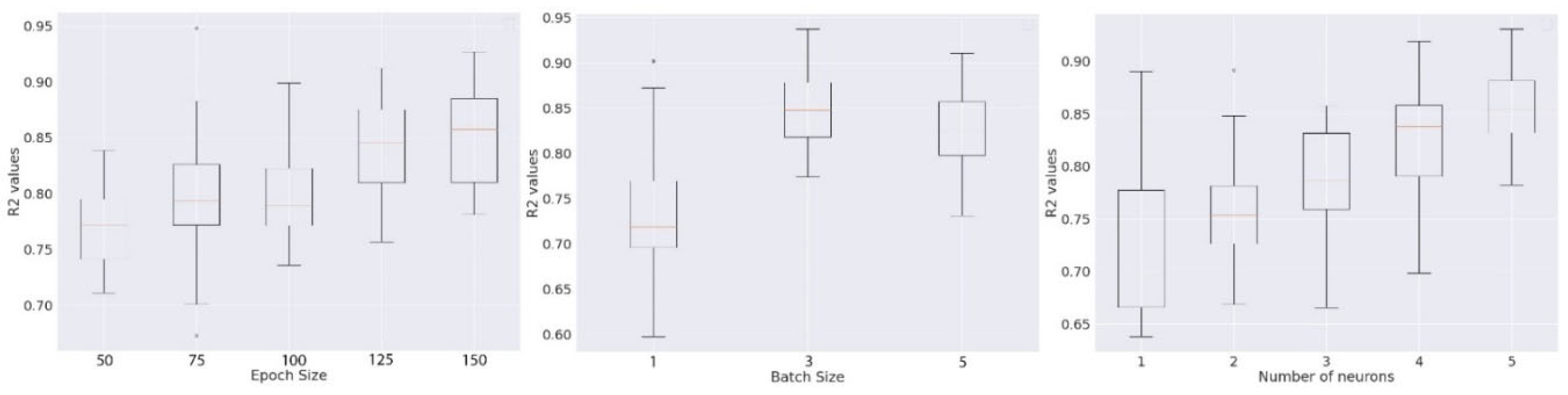

3.3. Hyperparameters Optimization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Uddin, Md.G.; Nash, S.; Olbert, A.I. A Review of Water Quality Index Models and Their Use for Assessing Surface Water Quality. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 122, 107218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Parajuli, P.B.; Ouyang, Y.; Dash, P.; Siegert, C. Assessing Land Use Change Impact on Stream Discharge and Stream Water Quality in an Agricultural Watershed. CATENA 2021, 198, 105055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeonov, V.; Stratis, J.A.; Samara, C.; Zachariadis, G.; Voutsa, D.; Anthemidis, A.; Sofoniou, M.; Kouimtzis, Th. Assessment of the Surface Water Quality in Northern Greece. Water Res. 2003, 37, 4119–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Kim, J.-H.; Li, M.-H. Predicting Stream Water Quality under Different Urban Development Pattern Scenarios with an Interpretable Machine Learning Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 761, 144057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.I.; Alaloul, W.S.; Alqahtani, A.; Aldrees, A.; Musarat, M.A.; Javed, M.F. Predictive Modeling Approach for Surface Water Quality: Development and Comparison of Machine Learning Models. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Xie, Y.; Wang, X.; Fang, Q. Exploring the Spatial-Seasonal Dynamics of Water Quality, Submerged Aquatic Plants and Their Influencing Factors in Different Areas of a Lake. Water 2017, 9, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Xie, Y.; Wang, X.; Fang, Q. Exploring the Spatial-Seasonal Dynamics of Water Quality, Submerged Aquatic Plants and Their Influencing Factors in Different Areas of a Lake. Water 2017, 9, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A.; Bhat, S.U.; Jehangir, A. Local Determinants Influencing Stream Water Quality. Appl. Water Sci. 2019, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A.; Bhat, S.U.; Jehangir, A. Local Determinants Influencing Stream Water Quality. Appl. Water Sci. 2019, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehedi, M.A.A.; Reichert, N.; Molkenthin, F. SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS OF HYPORHEIC EXCHANGE TO SMALL SCALE CHANGES IN GRAVEL-SAND FLUMEBED USING A COUPLED GROUNDWATER-SURFACE WATER MODEL. 2020, 10.13140/RG.2.2.19658.39366. [CrossRef]

- Full Article: How Much Is an Urban Stream Worth? Using Land Senses and Economic Assessment of an Urban Stream Restoration. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13504509.2021.1929546 (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Society, N.G. Stream. Available online: http://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/stream/ (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Onabule, O.A.; Mitchell, S.B.; Couceiro, F.; Williams, J.B. The Impact of Creek Formation and Land Drainage Runoff on Sediment Cycling in Estuarine Systems. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2022, 264, 107698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi S, Scholz M. Importance of water level management for peatland outflow water quality in the face of climate change and drought. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022 Oct;29(50):75455-75470. Epub 2022 Jun 2. PMID: 35653024; PMCID: PMC9553818. [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, J.-É.; Raimbault, P.; Garcia, N.; Lansard, B.; Babin, M.; Gagnon, J. Impact of River Discharge, Upwelling and Vertical Mixing on the Nutrient Loading and Productivity of the Canadian Beaufort Shelf. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 4853–4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Pan, S.; Chen, S. Impact of River Discharge on Hydrodynamics and Sedimentary Processes at Yellow River Delta. Mar. Geol. 2020, 425, 106210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehedi, M.A.A.; Yazdan, M.M.S. Automated Particle Tracing & Sensitivity Analysis for Residence Time in a Saturated Subsurface Media. Liquids 2022, 2, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHITEHEAD, P.G.; WILBY, R.L.; BATTARBEE, R.W.; KERNAN, M.; WADE, A.J. A Review of the Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Surface Water Quality. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2009, 54, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnahit, A.O.; Mishra, A.K.; Khan, A.A. Stream Water Quality Prediction Using Boosted Regression Tree and Random Forest Models. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagecic_monitoring_NJWEAmay2018.Pdf.

- Benyahya, L.; Caissie, D.; St-Hilaire, A.; Ouarda, T.B.M.J.; Bobée, B. A Review of Statistical Water Temperature Models. Can. Water Resour. J. Rev. Can. Ressour. Hydr. 2007, 32, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, C.A.; Golden, H.E.; Archfield, S.A. Monthly River Temperature Trends across the US Confound Annual Changes. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 104006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducharne, A. Importance of Stream Temperature to Climate Change Impact on Water Quality. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2008, 12, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, M.T.H.; Ludwig, F.; Zwolsman, J.J.G.; Weedon, G.P.; Kabat, P. Global River Temperatures and Sensitivity to Atmospheric Warming and Changes in River Flow. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (2) (PDF) A Review of Dissolved Oxygen Requirements for Key Sensitive Species in the Delaware Estuary Final Report. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329070843_A_Review_of_Dissolved_Oxygen_Requirements_for_Key_Sensitive_Species_in_the_Delaware_Estuary_Final_Report (accessed on 22 May 2022).

- Ehrenfeld, J.G.; Schneider, J.P. Chamaecyparis Thyoides Wetlands and Suburbanization: Effects on Hydrology, Water Quality and Plant Community Composition. J. Appl. Ecol. 1991, 28, 467–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, C.L.; Zampella, R.A. Specific Conductance and PH as Indicators of Watershed Disturbance in Streams of the New Jersey Pinelands, USA. Environ. Manage. 2000, 26, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Using-Multiple-Regression-to-Quantify-the-Effect-of-Land-Use-on-Surface-Water-Quality-and-Aquatic-Communities-in-the-New-Jersey-Pinelands.Pdf.

- Money, E.S.; Carter, G.P.; Serre, M.L. Modern Space/Time Geostatistics Using River Distances: Data Integration of Turbidity and E. Coli Measurements to Assess Fecal Contamination Along the Raritan River in New Jersey. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 3736–3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tousi, E.G.; Duan, J.G.; Gundy, P.M.; Bright, K.R.; Gerba, C.P. Evaluation of E. Coli in Sediment for Assessing Irrigation Water Quality Using Machine Learning. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 799, 149286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Yazdan, M.M.S. Evaluating Preventive Measures for Flooding from Groundwater: A Case Study. J 2023, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saksena, S.; Merwade, V.; Singhofen, P.J. Flood Inundation Modeling and Mapping by Integrating Surface and Subsurface Hydrology with River Hydrodynamics. J. Hydrol. 2019, 575, 1155–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Hodges, B.R. Applying Microprocessor Analysis Methods to River Network Modelling. Environ. Model. Softw. 2014, 52, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woznicki, S.A.; Baynes, J.; Panlasigui, S.; Mehaffey, M.; Neale, A. Development of a Spatially Complete Floodplain Map of the Conterminous United States Using Random Forest. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 942–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horritt, M.S.; Bates, P.D. Effects of Spatial Resolution on a Raster Based Model of Flood Flow. J. Hydrol. 2001, 253, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introduction to Fluid Mechanics, Fourth Edition; 2009; ISBN 978-1-4200-8525-9.

- Li, Y.; Babcock, R.W. Modeling Hydrologic Performance of a Green Roof System with HYDRUS-2D. J. Environ. Eng. 2015, 141, 04015036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, R.; Aalami, M.T.; Adamowski, J. Short-Term Water Quality Variable Prediction Using a Hybrid CNN–LSTM Deep Learning Model. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2020, 34, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Khosravi, M.; Vaferi, B.; Nait Amar, M.; Ghriga, M.A.; Mohammed, A.H. Application of Machine Learning Methods for Estimating and Comparing the Sulfur Dioxide Absorption Capacity of a Variety of Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinshaw, T.A.; Surbeck, C.Q.; Yasarer, H.; Najjar, Y. Artificial Neural Network for Prediction of Total Nitrogen and Phosphorus in US Lakes. J. Environ. Eng. 2019, 145, 04019032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, M.; Arif, S.B.; Ghaseminejad, A.; Tohidi, H.; Shabanian, H. Performance Evaluation of Machine Learning Regressors for Estimating Real Estate House Prices. Preprints. 2022, 2022090341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Babovic, V. Uncovering Flooding Mechanisms Across the Contiguous United States Through Interpretive Deep Learning on Representative Catchments. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR030185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdan, M.M.S.; Khosravia, M.; Saki, S.; Mehedi, M.A.A. Forecasting Energy Consumption Time Series Using Recurrent Neural Network in Tensorflow. Preprints. 2022, 2022090404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ye, M.; Yang, J. Developing a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Based Model for Predicting Water Table Depth in Agricultural Areas. J. Hydrol. 2018, 561, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannas, B.; Fanni, A.; See, L.; Sias, G. Data Preprocessing for River Flow Forecasting Using Neural Networks: Wavelet Transforms and Data Partitioning. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts ABC 2006, 31, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, C.; Voyant, C.; Muselli, M.; Nivet, M.-L. Forecasting of Preprocessed Daily Solar Radiation Time Series Using Neural Networks. Sol. Energy 2010, 84, 2146–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, M.; Tabasi, S.; Hossam Eldien, H.; Motahari, M.R.; Alizadeh, S.M. Evaluation and Prediction of the Rock Static and Dynamic Parameters. J. Appl. Geophys. 2022, 199, 104581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahzadeh, M.; Khosravi, M.; Hajipour Khire Masjidi, B.; Samimi Behbahan, A.; Bagherzadeh, A.; Shahkar, A.; Tat Shahdost, F. Estimating the Density of Deep Eutectic Solvents Applying Supervised Machine Learning Techniques. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ye, M.; Yang, J. Developing a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Based Model for Predicting Water Table Depth in Agricultural Areas. J. Hydrol. 2018, 561, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Russo, T.A.; Elliott, J.; Foster, I. Machine Learning Algorithms for Modeling Groundwater Level Changes in Agricultural Regions of the U.S. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 3878–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, R.; Aalami, M.T.; Adamowski, J. Short-Term Water Quality Variable Prediction Using a Hybrid CNN–LSTM Deep Learning Model. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2020, 34, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predicting Residential Energy Consumption Using CNN-LSTM Neural Networks - ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360544219311223 (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ye, M.; Yang, J. Developing a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Based Model for Predicting Water Table Depth in Agricultural Areas. J. Hydrol. 2018, 561, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutskever, I.; Vinyals, O.; Le, Q.V. Sequence to Sequence Learning with Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc., 2014; Vol. 27.

- Sundermeyer, M.; Schlüter, R.; Ney, H. LSTM Neural Networks for Language Modeling. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2012; ISCA, September 9 2012; pp. 194–197.

- Mikolov, T. Recurrent Neural Network Based Language Model. 24.

- Akatu, W.; Khosravi, M.; Mehedi, M.A.A.; Mantey, J.; Tohidi, H.; Shabanian, H. Demystifying the Relationship Between River Discharge and Suspended Sediment Using Exploratory Analysis and Deep Neural Network Algorithms. Preprints. 2022, 2022110437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, M.; Mehedi, M.A.A.; Baghalian, S.; Burns, M.; Welker, A.L.; Golub, M. Using Machine Learning to Improve Performance of a Low-Cost Real-Time Stormwater Control Measure. Preprints. 2022, 2022110519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGS Current Conditions for USGS 01463500 Delaware River at Trenton NJ. Available online: https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/uv?01463500 (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Beretta, L.; Santaniello, A. Nearest Neighbor Imputation Algorithms: A Critical Evaluation. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2016, 16, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feature Engineering and Deep Learning-Based Intrusion Detection Framework for Securing Edge IoT | SpringerLink. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11227-021-04250-0 (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Zheng, A.; Casari, A. Feature Engineering for Machine Learning: Principles and Techniques for Data Scientists; O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2018; ISBN 978-1-4919-5319-8.

- Talbot, C.; Thrane, E. Flexible and Accurate Evaluation of Gravitational-Wave Malmquist Bias with Machine Learning. Astrophys. J. 2022, 927, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Khosravi, M.; Fathollahi, R.; Khandakar, A.; Vaferi, B. Determination of the Heat Capacity of Cellulosic Biosamples Employing Diverse Machine Learning Approaches. Energy Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1925–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebala, G.; Ravi, A.; Churiwala, S. Machine Learning Definition and Basics. In An Introduction to Machine Learning; Rebala, G., Ravi, A., Churiwala, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-3-030-15729-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Al Mehedi, M.A.; Yazdan, M.M.S.; Kumar, R. Development of Machine Learning Flood Model Using Artificial Neural Network (ANN) at Var River. Liquids 2022, 2, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Simard, P.; Frasconi, P. Learning Long-Term Dependencies with Gradient Descent Is Difficult. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1994, 5, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilinc, H.C.; Haznedar, B. A Hybrid Model for Streamflow Forecasting in the Basin of Euphrates. Water 2022, 14, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Liu, Y.; Xue, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Jiang, L.; Cheng, Z. Time-Series Well Performance Prediction Based on Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Neural Network Model. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 186, 106682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younger, A.S.; Hochreiter, S.; Conwell, P.R. Meta-Learning with Backpropagation. In Proceedings of the IJCNN’01. International Joint Conference on Neural Networks. Proceedings (Cat. No.01CH37222); July 2001; Vol. 3, pp. 2001–2006 vol.3.

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudemeyer, R.C.; Morris, E.R. Understanding LSTM -- a Tutorial into Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Neural Networks. ArXiv190909586 Cs 2019.

- Tsang, G.; Deng, J.; Xie, X. Recurrent Neural Networks for Financial Time-Series Modelling. In Proceedings of the 2018 24th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR); August 2018; pp. 892–897.

- Maulik, R.; Egele, R.; Lusch, B.; Balaprakash, P. Recurrent Neural Network Architecture Search for Geophysical Emulation. ArXiv200410928 Phys. 2020.

- Keras: The Python Deep Learning API. Available online: https://keras.io/ (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Mehedi, M.A.A.; Khosravi, M.; Yazdan, M.M.S.; Shabanian, H. Exploring Temporal Dynamics of River Discharge Using Univariate Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Recurrent Neural Network at East Branch of Delaware River. Hydrology 2022, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.V.; Kling, H. On Typical Range, Sensitivity, and Normalization of Mean Squared Error and Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency Type Metrics. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.J.; Robeson, S.M.; Matsuura, K. A Refined Index of Model Performance. Int. J. Climatol. 2012, 32, 2088–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SW Parameters | Unit | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Discharge | ft3/s | Quantity of stream flow |

| Water Level | ft | Stream water height/level at the gage location |

| Temperature | ℃ | Sensor-recorded temperature in ℃ at the gage |

| Dissolved Oxygen (DO) | mg/L | The amount oxygen dissolved in the SW. |

| Turbidity | FNU | Measure of turbidity in Formazin Nephelometric Unit (FNU) |

| pH | - | the acidity or alkalinity of a solution on a logarithmic scale |

| Specific Conductance (SC) | μS/cm | Measure of the collective concentration of dissolved ions in solution |

| Count | Mean | Std | Min | 25% | 50% | 75% | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge (ft3/s) | 255066 | 13265.43 | 10657.91 | 2150 | 6240 | 10800 | 16100 | 150000 |

| Water Level (ft) | 255066 | 9.98 | 1.47 | 7.8 | 8.89 | 9.73 | 10.73 | 20.76 |

| Temperature (℃) | 255066 | 13.35 | 4.43 | 0 | 12.02 | 13.58 | 15.01 | 31.30 |

| pH | 255066 | 7.90 | 0.208 | 6.6 | 7.00 | 8.23 | 9.16 | 9.71 |

| SC (μS/cm) | 255066 | 208.19 | 22.23 | 49 | 201.11 | 208.64 | 221.09 | 453 |

| Turbidity (FNU) | 255066 | 6.44 | 6.54 | 0.2 | 5.61 | 6.44 | 7.29 | 469 |

| DO (mg/L) | 255066 | 11.02 | 1.11 | 6 | 11.02 | 11.07 | 12.67 | 16.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).