2.1. Natural Language Processing for Requirements Engineering (NLP4RE)

Requirements are almost always written in NL [

18] to make them accessible to different stakeholders. According to various surveys, NL was deemed to be the best way to express requirements [

19], and 95% of 151 software companies surveyed revealed that they were using some form of NL to capture requirements [

20]. Given the ease of using NL for requirements elicitation, researchers have been striving to come up with NLP tools for requirements processing dating back to the 1970s. Tools such as the Structured Analysis Design Technique (SADT), and the System Design Methodology (SDM) developed at MIT, are systems that were created to aid in requirement writing and management [

19]. Despite the interest in applying NLP techniques and models to the requirements engineering domain, the slow development of natural language technologies thwarted progress until recently [

11]. The availability of NL libraries/toolkits (Stanford CoreNLP [

21], NLTK [

22], spaCy [

23], etc.), and off-the-shelf transformer-based [

24] pre-trained language models (LMs) (BERT [

17], BART [

25], etc.) have propelled NLP4RE into an active area of research.

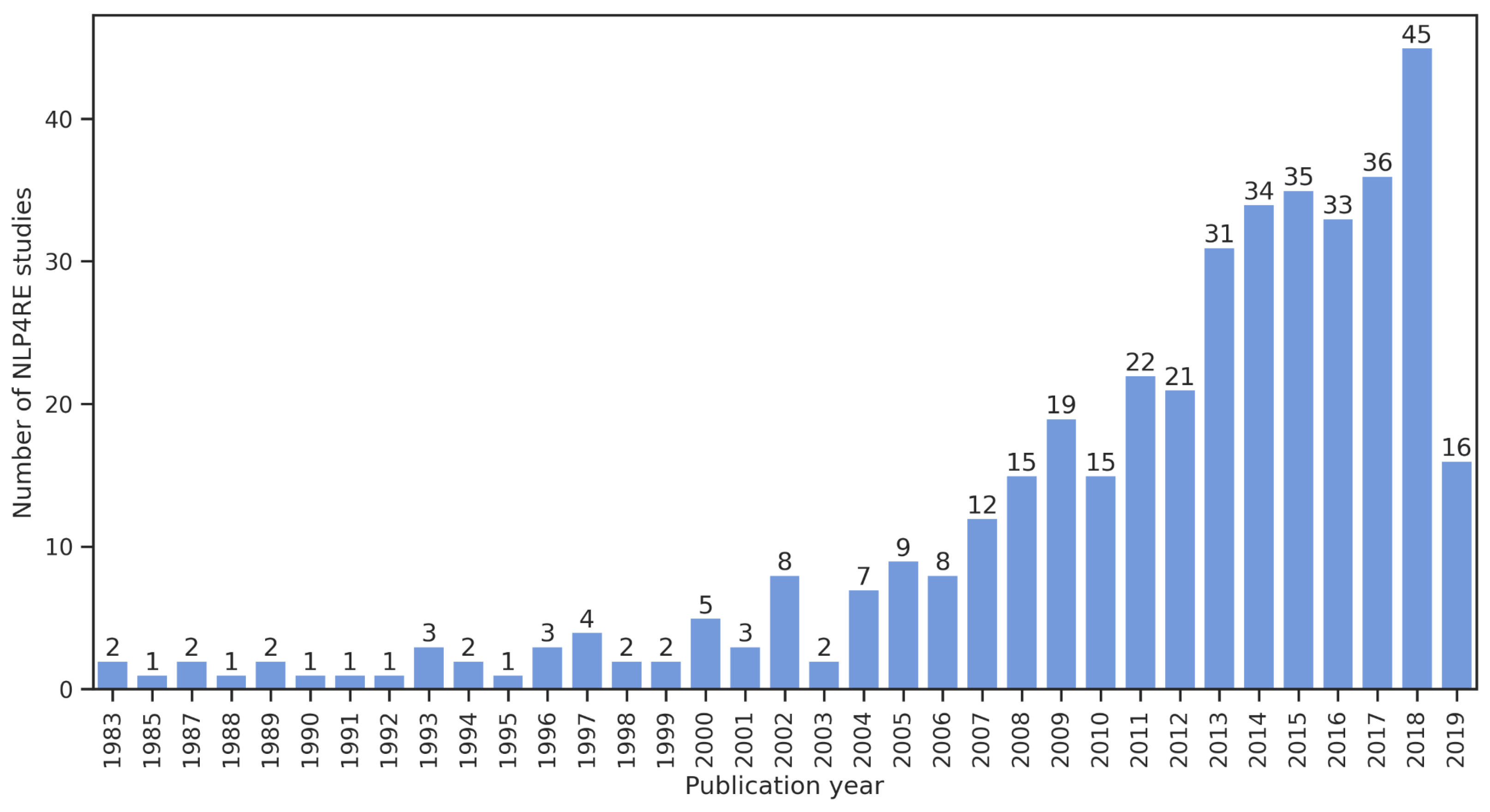

A recent survey performed by Zhao et al. reviewed 404 NLP4RE studies conducted between 1983 and April 2019 and reported on the developments in this domain [

26].

Figure 1 shows a clear increase in the number of published studies in NLP4RE over the years. This underlines the fact that NLP plays a crucial role in requirements engineering and will only get more important with time, given the availability of off-the-shelf language models.

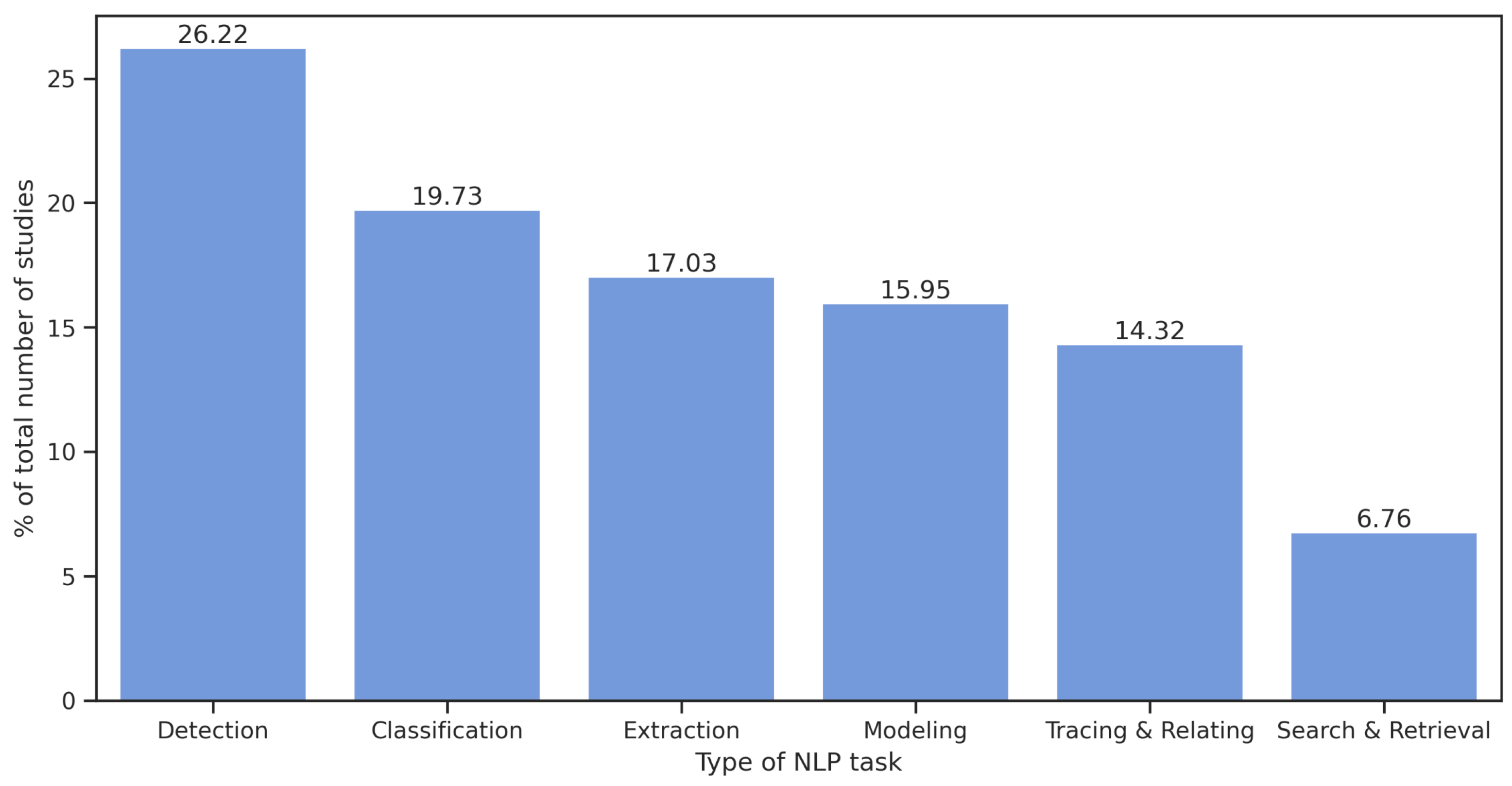

Among the 404 NLP4RE studies reported in [

26], 370 NLP4RE studies were analyzed and classified based on the main NLP4RE task being performed. 26.22% of these studies focused on detecting linguistic errors in requirements (use of ambiguous phrases, conformance to boilerplates, etc.), 19.73% focused on requirements classification, and 17.03% on text extraction tasks focused on the identification of key domain concepts (

Figure 2).

As mentioned, the classification of requirements is a critical step toward their conversion into a semi-machine-readable/standardized format. The following section discusses how NLP has evolved and can be leveraged to enable classification.

2.2. Natural Language Processing (NLP) & Language Models (LMs)

NLP is promising when it comes to classifying requirements, which is a potential step toward the development of pipelines that can convert free-form NL requirements into standardized requirements in a semi-automated manner. Language models (LMs), in particular, can be leveraged for classifying text (or requirements, in the context of this research) [

17,

25,

27]. Language modeling was classically defined as the task of predicting which word comes next [

28]. Initially, this was limited to statistical language models [

29], which use prior word sequences to compute the conditional probability for each of a vocabulary future word. The high-dimensional discrete language representations limit these models to N-grams [

30], where only the prior N words are considered for predicting the next word or short sequences of following words, typically using high-dimensional one-hot encodings for the words.

Neural LMs came into existence in 2000s [

31] and leveraged neural networks to simultaneously learn lower-dimensional word embeddings and learn to estimate conditional probabilities of next words simultaneously using gradient-based supervised learning. This opened the door to ever-more-complex and effective language models to perform an expanding array of NLP tasks, starting with distinct word embeddings [

32] to recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [

33] and LSTM encoder-decoders [

34] to attention mechanisms [

35]. These models did not stray too far from the N-gram statistical language modeling paradigm, with advances that allowed text generation beyond a single next word with for example beam search in [

34] and sequence-to-sequence learning in [

36]. These ideas were applied to distinct NLP tasks.

In 2017, the Transformer [

24] architecture was introduced that improved computational parallelization capabilities over recurrent models, and therefore enabled the successful optimization of larger models. Transformers consist of stacks of encoders (encoder block) and stacks of decoders (decoder block), where the encoder block receives the input from the user and outputs a matrix representation of the input text. The decoder takes the input representation produced by the encoder stack and generates outputs iteratively [

24].

All of these works required training on a single labeled dataset for a specific task. In 2018-20, several new models emerged and set new state-of-the-art marks in nearly all NLP tasks. These transformer-based models include the Bidirectional Encoder Representational Transformer (BERT) language model [

17] (auto-encoding model), the Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) family [

37,

38] of auto-regressive language models, and T5 character-level language model [

39]. These sophisticated language models break the single dataset-single task modeling paradigm of most mainstream models in the past. They employ self-supervised pre-training on massive

unlabeled text corpora. For example, BERT is trained on Book Corpus (800M words) and English Wikipedia (2500M words) [

17]. Similarly, GPT-3 is trained on 500B words gathered from datasets of books and the internet [

38].

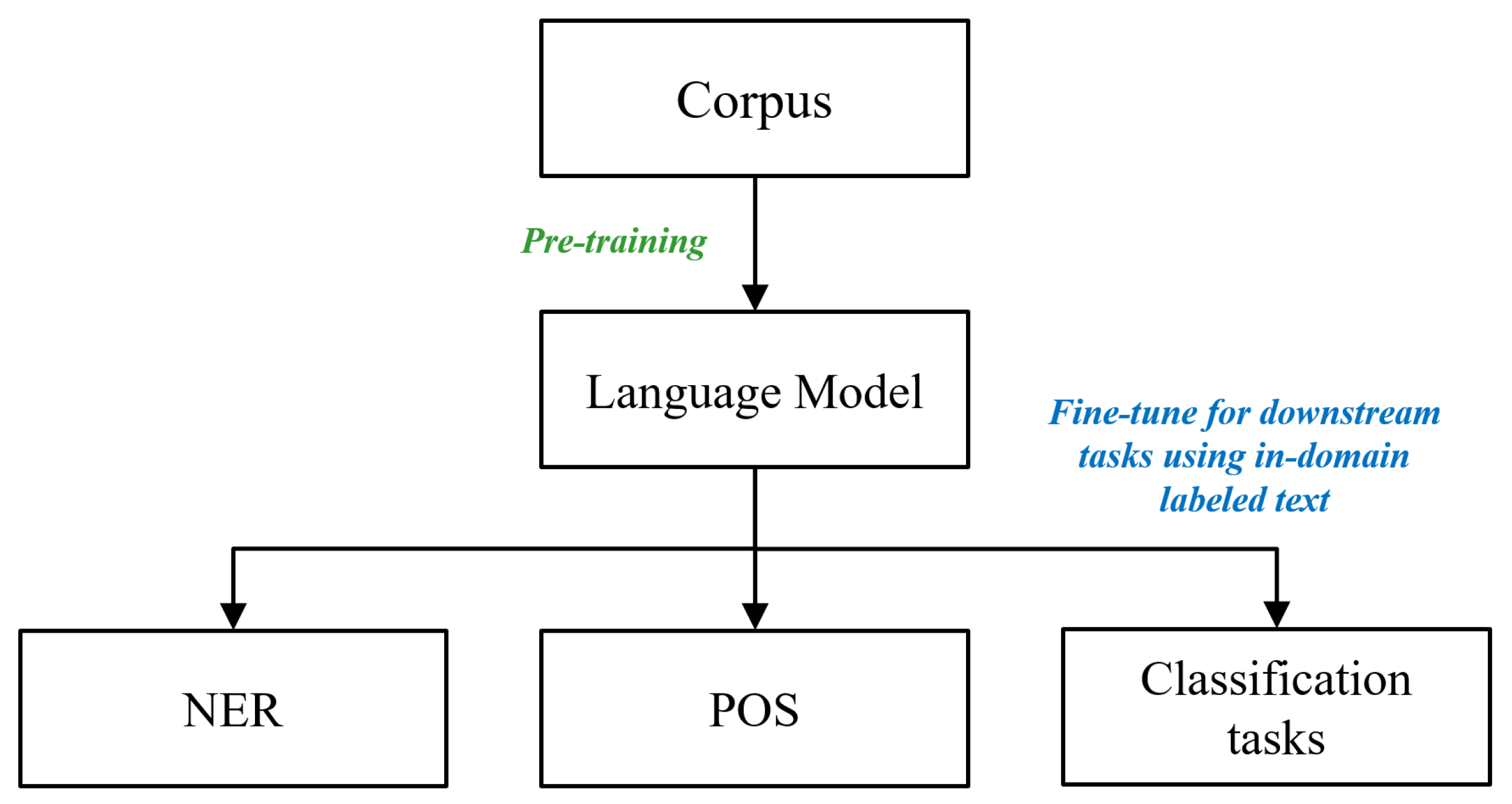

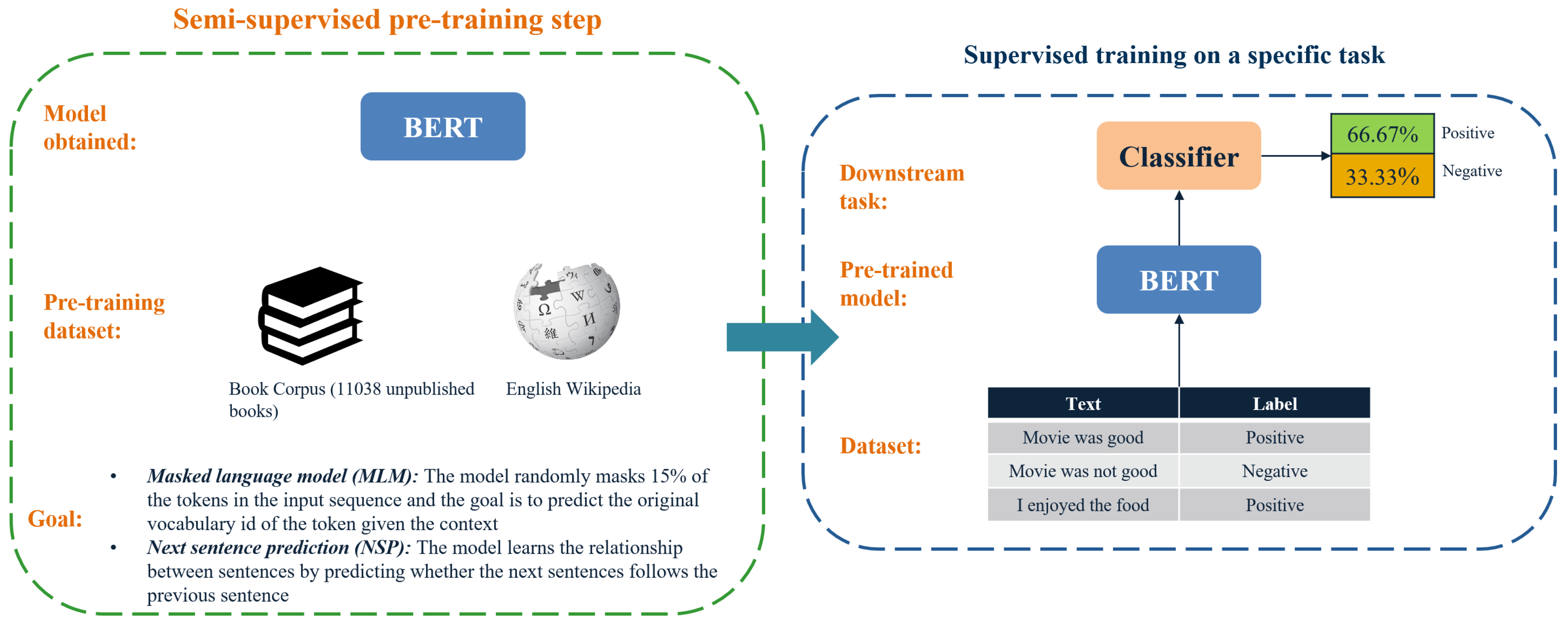

These techniques set up automated supervised learning tasks, such as masked language modeling (MLM), next-sentence prediction (NSP), and generative pre-training. No labeling is required as the labels are automatically extracted from the text and hidden from the model, and the model is trained to predict them. This enables the models to develop a deep understanding of language, independent of the NLP task. These pre-trained models are then fine-tuned on much smaller labeled datasets, leading to advances in the state of the art (SOTA) for nearly all downstream NLP tasks (

Figure 3), such as Named-entity recognition (NER), text classification, language translation, question answering, etc. [

17,

40,

41].

Training these models from scratch can be prohibitive given the computational power required: to put things into perspective, it took 355 GPU-years and

$4.6 million to train GPT-3 [

43]. Similarly, the pre-training cost for BERT

BASE model with 110 million parameters varied between

$2.5k-

$50k, while it cost between

$10k-

$200k to pre-train BERT

LARGE with 340 million parameters [

44]. Pre-training the BART LM took between 12 days with 256 GPUs [

25]. These general-purpose LMs can then be fine-tuned for specific downstream NLP tasks at a small fraction of the computational cost and time–even in a matter of minutes or hours on a single-GPU computer [

17,

45,

46,

47,

48].

Pre-trained LMs are readily available on the Hugging Face platform [

49] and can be accessed via the

transformers library. These models can then be fine-tuned on downstream tasks with a labeled dataset specific to the downstream task of interest. For example, for text classification, a dataset containing the text and the corresponding labels should be used for fine-tuning the model. The final model with text classification capability will eventually have different model parameters as compared to the parameters it was initialized with [

17].

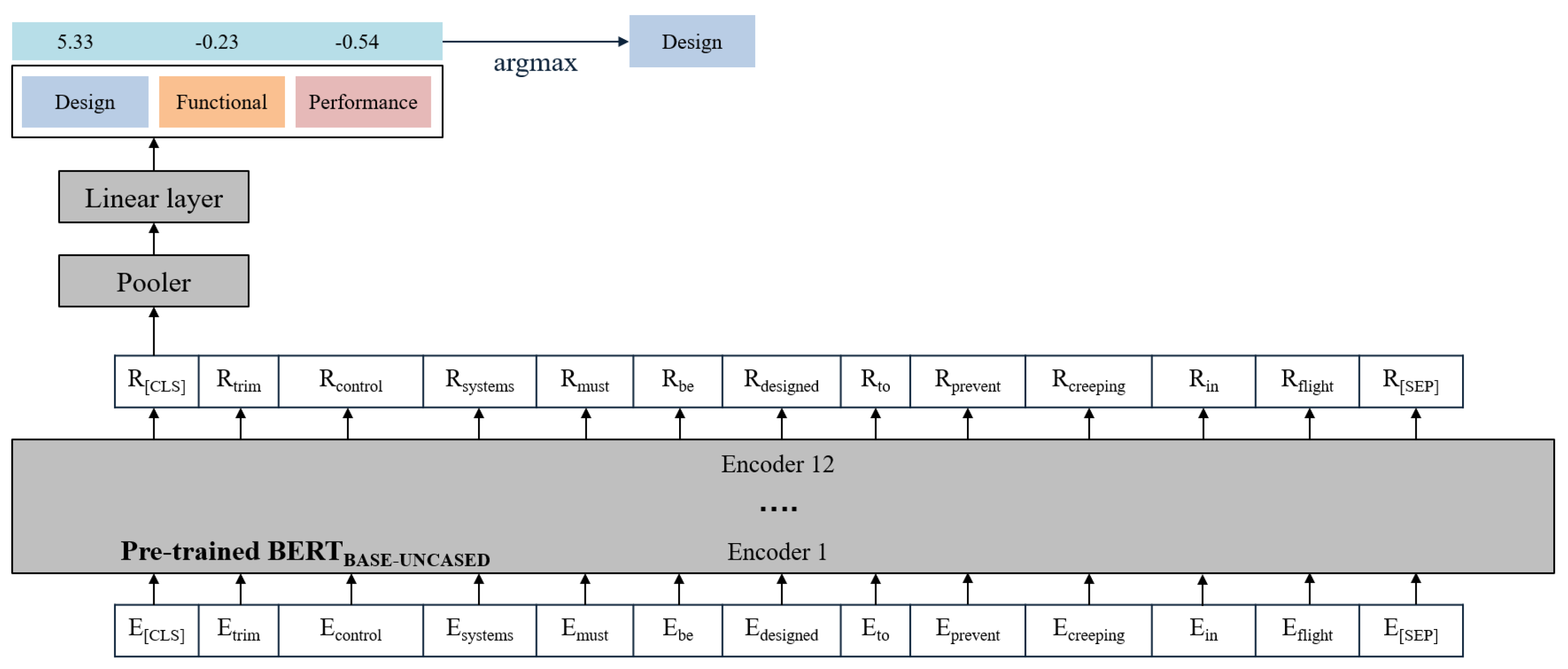

Figure 4 illustrates the pre-training and fine-tuning steps for BERT for a text classification task.

The following section provides details about some of the LMs used for text classification purposes.

2.2.1. Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT)

As mentioned previously, BERT is a pre-trained LM that is capable of learning deep

bidirectional representations from an unlabeled text by jointly incorporating both the left and right context of a sentence in all layers [

17]. Being a transformer-based LM, BERT is capable of learning the complex structure and the non-sequential content in language by using

attention mechanisms, fully-connected neural network layers, and positional encoding [

24,

50]. Despite being trained on a large corpus, the vocabulary of BERT is just 30,000 words since it uses WordPiece Tokenizer which breaks words into sub-words, and eventually into letters (if required) to accommodate for out-of-vocabulary words. This makes the practical vocabulary BERT can understand much larger. For example, “ing” is a single word piece, so it can be added to nearly all verbs in the base vocabulary to extend the vocabulary tremendously. BERT comes in two variants when it comes to model architecture [

17]:

BERTBASE: contains 12 encoder blocks with a hidden size of 768, and 12 self-attention heads (total of 110 M parameters)

BERTLARGE: contains 24 encoder blocks with a hidden size of 1024, and 16 self-attention heads (total of 340M parameters)

BERT is pre-trained on two self-supervised language tasks, namely, Masked Language Modeling (MLM) and Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) (

Figure 4), which help it develop a general-purpose understanding of natural language. However, it can be fine-tuned to perform various downstream tasks such as text classification, NER, Part-of-Speech (POS) tagging, etc. A task-specific output layer is what separates a pre-trained BERT from a BERT fine-tuned to perform a specific task.

In a recent study, Hey et al. fine-tuned the BERT language model on the PROMISE NFR dataset [

51] to obtain NoRBERT (Non-functional and functional Requirements classification using BERT) - a model capable of classifying requirements [

52]. NoRBERT is capable of performing four tasks, namely, (1) binary classification of requirements into two classes (functional and non-functional); (2) binary and multi-class classification of four non-functional requirement classes (Usability, Security, Operational, and Performance); (3) multi-class classification of ten non-functional requirement types; and (4) binary classification of the functional and quality aspect of requirements.

The PROMISE NFR dataset [

51] contains 625 requirements in total (255 functional and 370 non-functional, which are further broken down into different “sub-types”). It is, to the authors’ knowledge, the only requirements dataset of its kind that is publicly available. However, using this dataset was deemed implausible for this work because it predominantly focuses on software engineering systems and requirements.

Table 1 shows some examples from the PROMISE NFR dataset.

Another avenue for text classification is zero-shot text classification, which is discussed in detail in the next section.

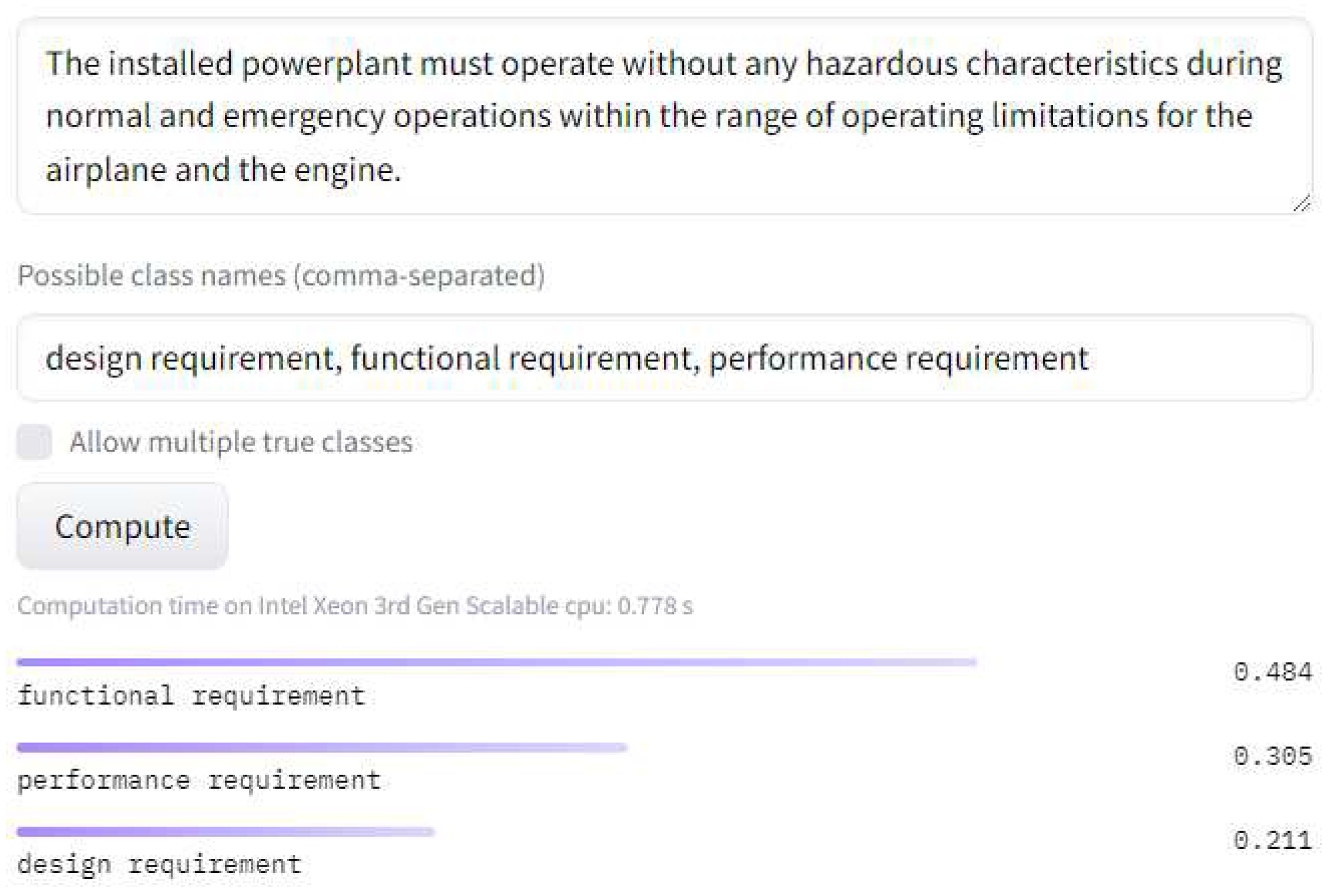

2.2.2. Zero-shot Text Classification

Models doing a task that they are not explicitly trained for is called zero-shot learning (ZSL) [

53]. There are two general ways for ZSL, namely,

entailment-based and

embedding-based methods. Yin et al. proposed a method for zero-shot text classification using pre-trained Natural Language Inference (NLI) models [

54]. The

bart-large-mnli model was obtained by training

bart-large [

25] on the MultiNLI (MNLI) dataset, which is a crowd-sourced dataset containing 433,000 sentence pairs annotated with textual entailment information [0: entailment; 1: neutral; 2: contradiction] [

55]. For example, to classify the sentence “

The United States is in North America” into one of the possible classes, namely,

politics,

geography, or

film, we could construct a hypothesis such as -

This text is about geography. The probabilities for the entailment and contraction of the hypothesis will then be converted to probabilities associated with each of the labels provided.

Alhosan et al. [

56] performed a preliminary study for the classification of requirements using ZSL in which they classified non-functional requirements into two categories, namely usability, and security. An embedding-based method was used where the probability of the relatedness (cosine similarity) between the text embedding layer and the tag (or label) embedding layer was calculated to classify the requirement into either of the two categories. This work uses a subset of the PROMISE NFR dataset as well [

51].

The zero-shot learning method for classifiers has been introduced in this section to serve as a basis for LM performance in the classification task. The initial hypothesis behind this work is that the tuned aeroBERT-Classifier will outperform the bart-large-mnli model.