Submitted:

31 January 2023

Posted:

03 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

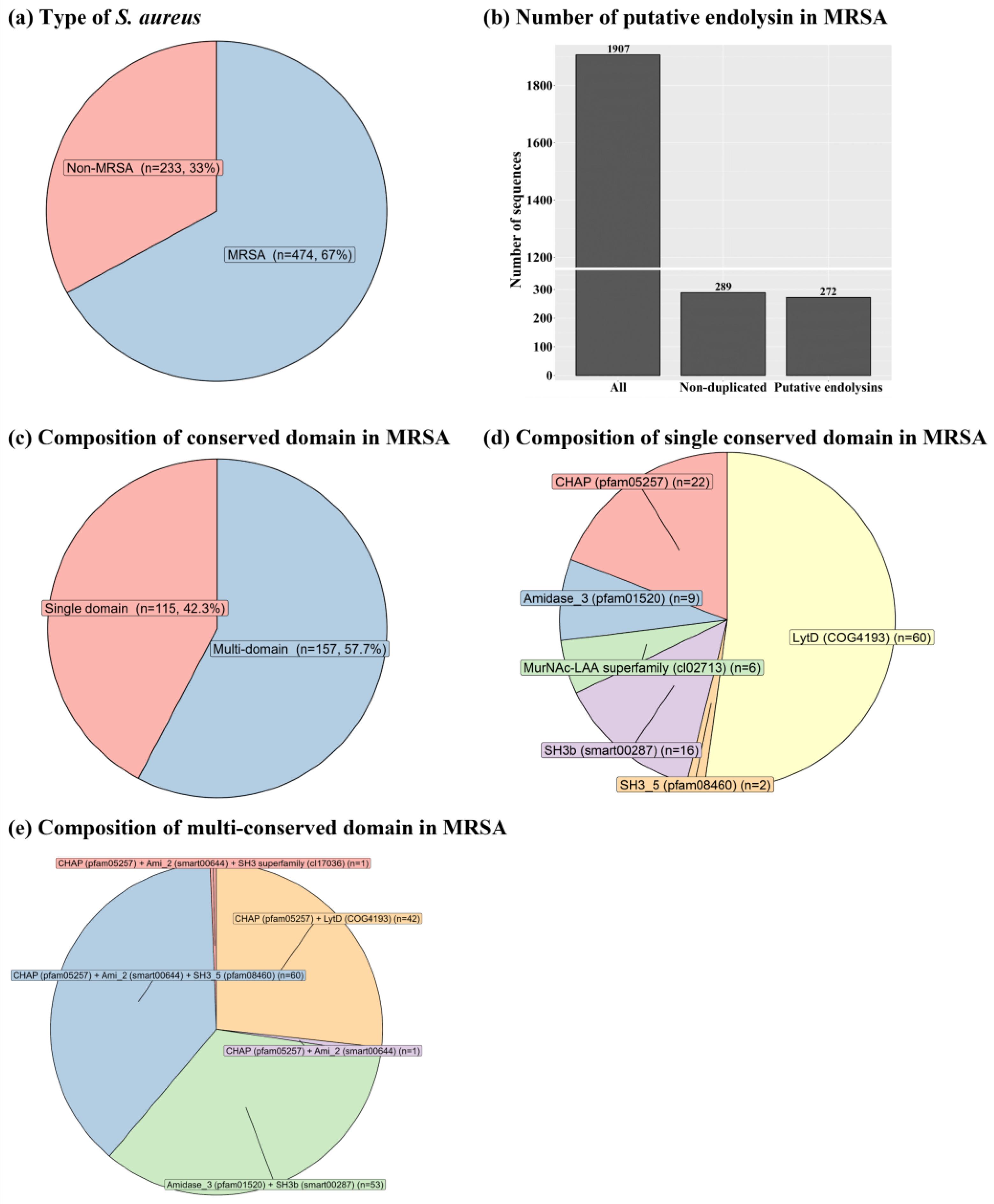

2.1. Identification of putative endolysins from MRSA

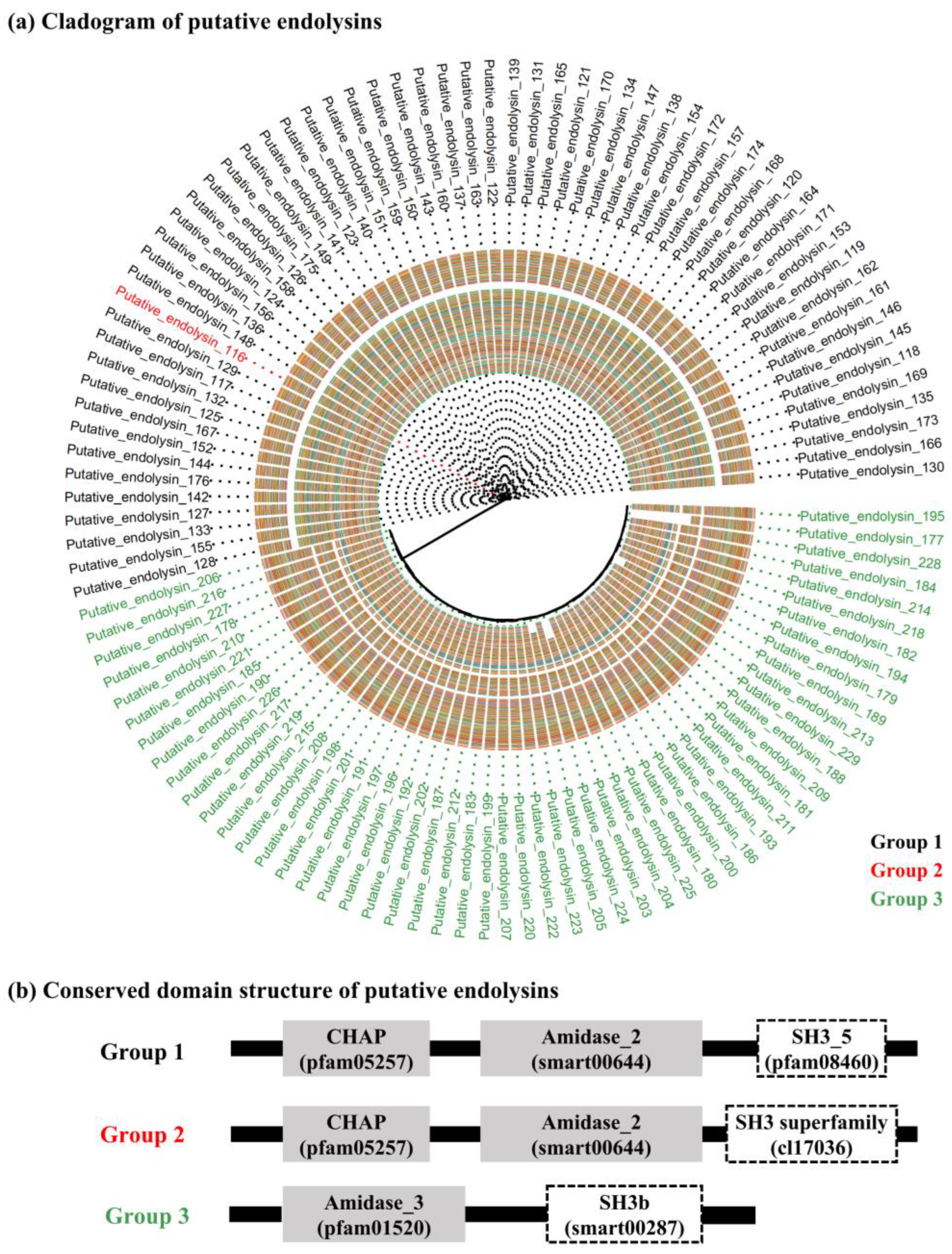

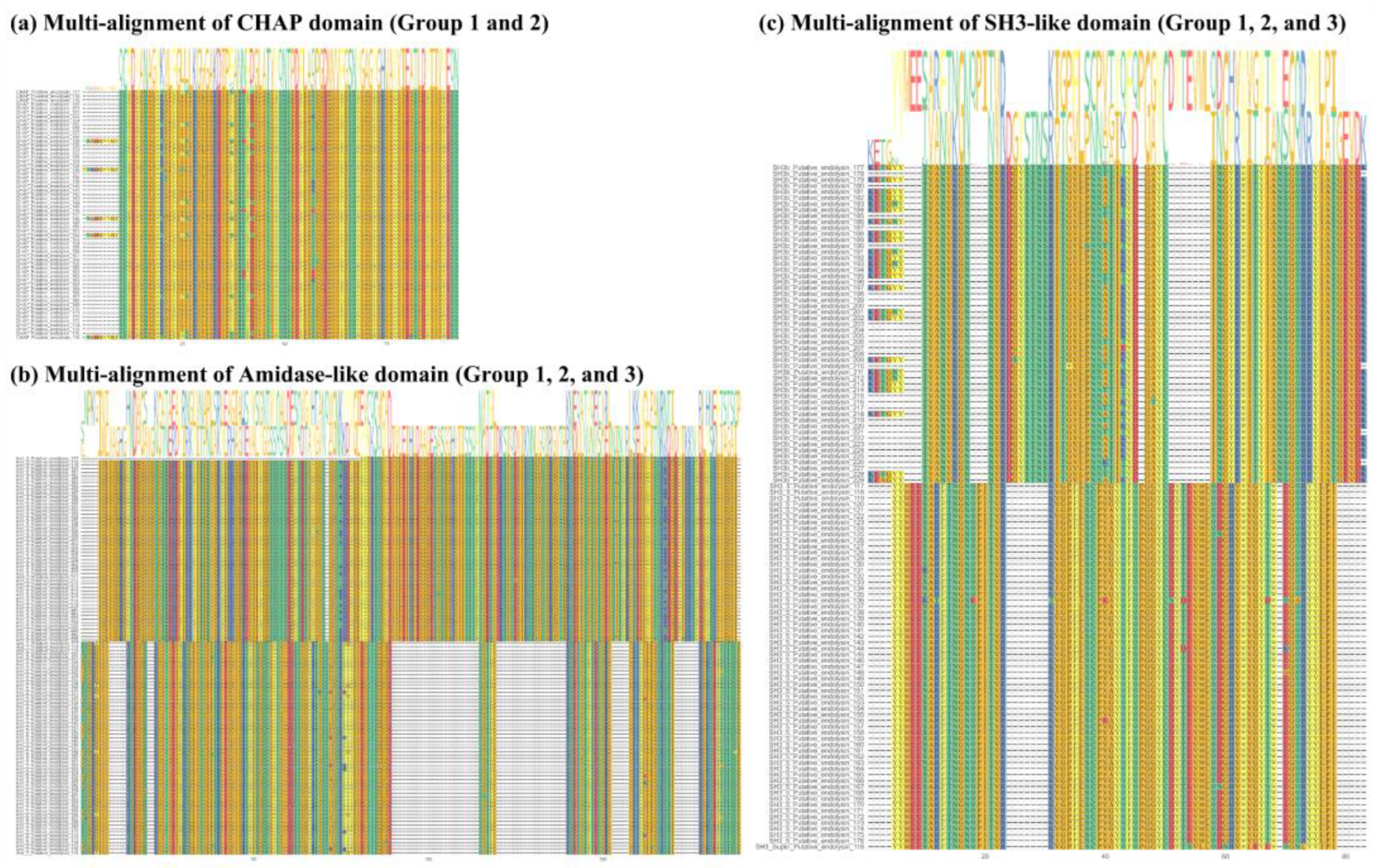

2.2. Sequence comparison of putative endolysins targeting MRSA

2.3. Comparison of predicted recombinant protein solubility

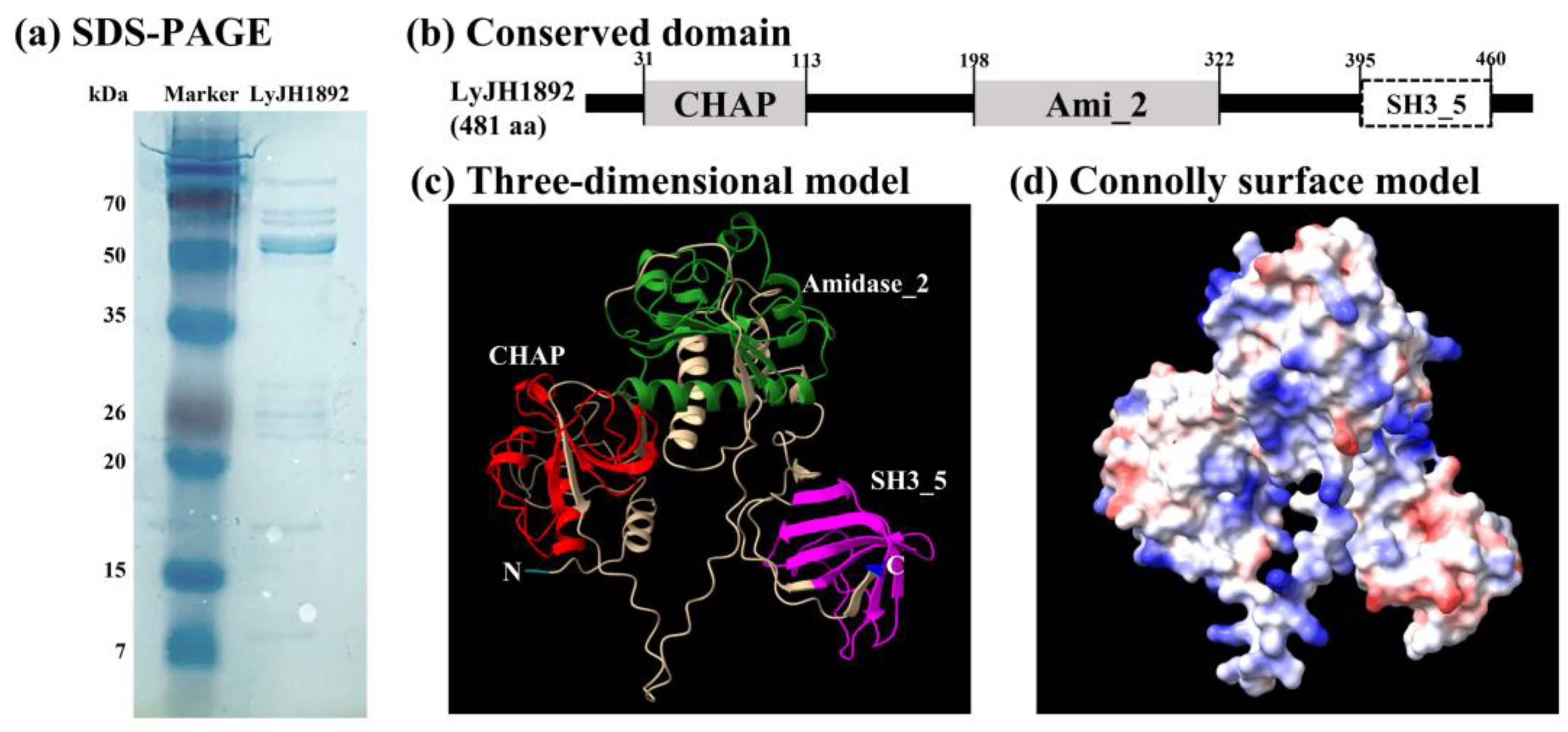

2.4. Overexpression and structural analysis of selected endolysins

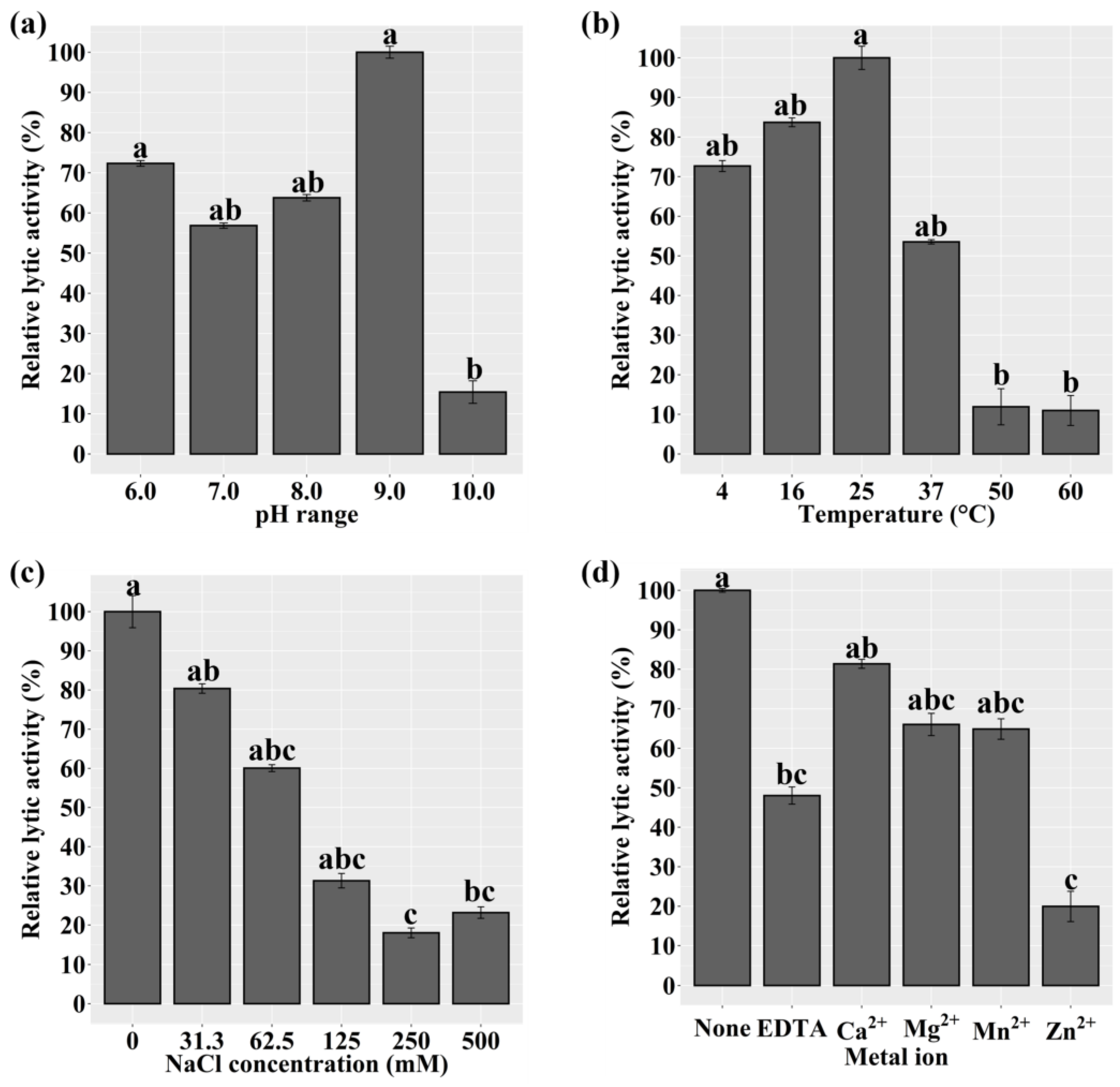

2.5. Characterization of Recombinant LyJH1892

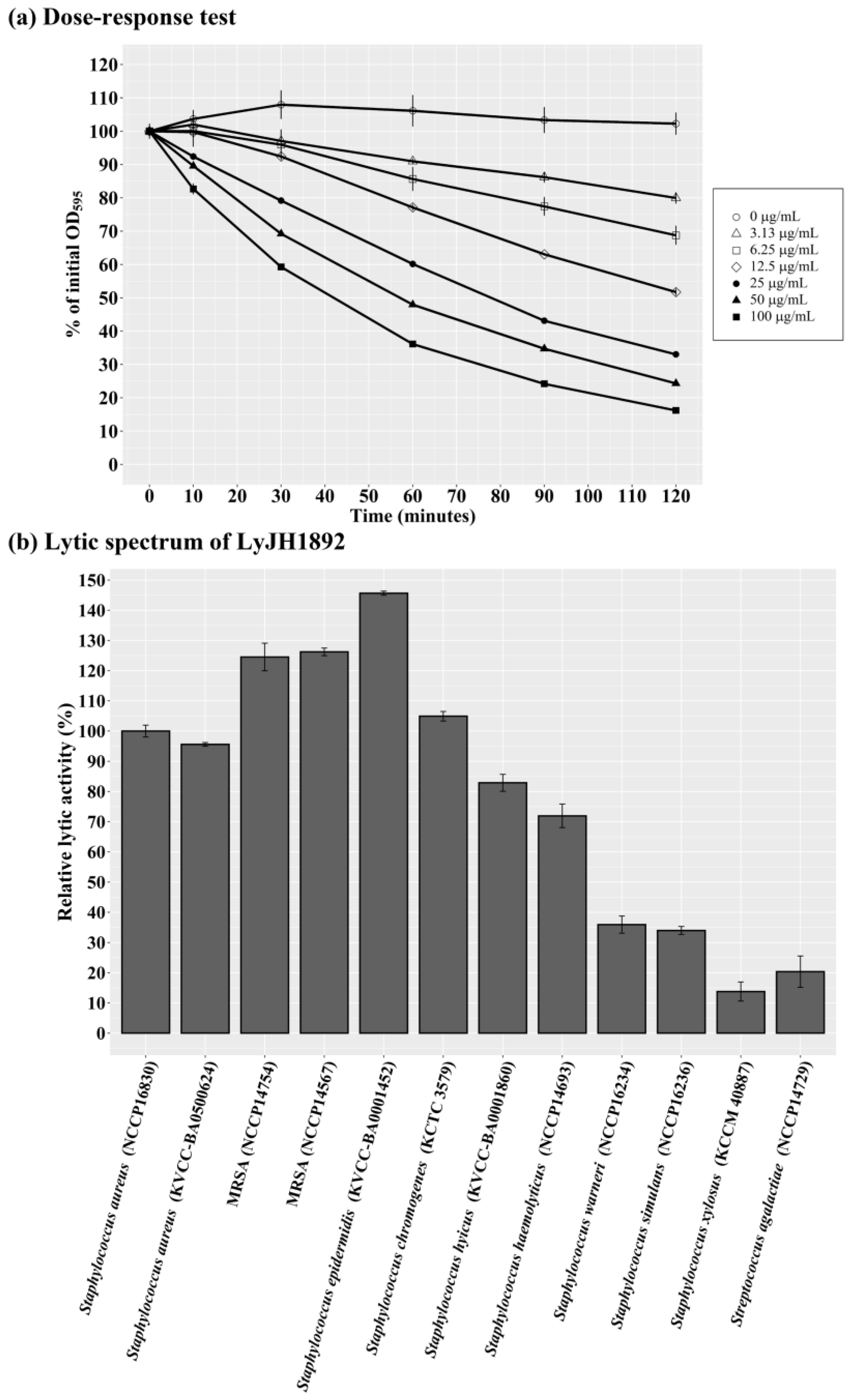

2.6. Optimal lytic activity and lytic spectrum of LyJH1892

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial strains and growth conditions

4.2. Collection of putative endolysins against MRSA

4.3. Conserved domain analysis, sequence alignment, and solubility prediction of putative endolysins

4.4. Identification, cloning, and overexpression of endolysin LyJH1892

4.5. Structure prediction of LyJH1892

4.6. Characterization and lytic spectrum of LyJH1892

4.7. Statistical analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haddad Kashani, H.; Schmelcher, M.; Sabzalipoor, H.; Seyed Hosseini, E.; Moniri, R. Recombinant endolysins as potential therapeutics against antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: current status of research and novel delivery strategies. Clinical microbiology reviews 2018, 31, e00071-00017. [CrossRef]

- Kluytmans, J.; Van Belkum, A.; Verbrugh, H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clinical microbiology reviews 1997, 10, 505-520. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, D.; Fernández, L.; Rodríguez, A.; García, P. Are phage lytic proteins the secret weapon to kill Staphylococcus aureus? MBio 2018, 9, e01923-01917. [CrossRef]

- Wertheim, H.F.L.; Melles, D.C.; Vos, M.C.; van Leeuwen, W.; van Belkum, A.; Verbrugh, H.A.; Nouwen, J.L. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2005, 5, 751-762, . [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.J. Antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Current status and future prospects. FEMS microbiology reviews 2017, 41, 430-449. [CrossRef]

- Sakoulas, G.; Moellering, R.C., Jr. Increasing Antibiotic Resistance among Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Strains. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2008, 46, S360-S367, . [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.N.; Han, S.G. Bovine mastitis: Risk factors, therapeutic strategies, and alternative treatments—A review. Asian-Australasian journal of animal sciences 2020, 33, 1699. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, F.; Manzi, M.; Joaquim, S.; Richini-Pereira, V.; Langoni, H. Outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)-associated mastitis in a closed dairy herd. Journal of Dairy Science 2017, 100, 726-730. [CrossRef]

- Juhász-Kaszanyitzky, É.; Jánosi, S.; Somogyi, P.; Dán, Á.; vanderGraaf van Bloois, L.; Van Duijkeren, E.; Wagenaar, J.A. MRSA transmission between cows and humans. Emerging infectious diseases 2007, 13, 630. [CrossRef]

- Schmelcher, M.; Donovan, D.M.; Loessner, M.J. Bacteriophage endolysins as novel antimicrobials. Future microbiology 2012, 7, 1147-1171. [CrossRef]

- Donovan, D.M. Bacteriophage and peptidoglycan degrading enzymes with antimicrobial applications. Recent patents on biotechnology 2007, 1, 113-122. [CrossRef]

- Love, M.J.; Bhandari, D.; Dobson, R.C.; Billington, C. Potential for bacteriophage endolysins to supplement or replace antibiotics in food production and clinical care. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 17. [CrossRef]

- Cisani, G.; Varaldo, P.E.; Grazi, G.; Soro, O. High-level potentiation of lysostaphin anti-staphylococcal activity by lysozyme. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 1982, 21, 531-535. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.K. Lysostaphin: an antistaphylococcal agent. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2008, 80, 555-561. [CrossRef]

- Sugai, M.; Fujiwara, T.; Akiyama, T.; Ohara, M.; Komatsuzawa, H.; Inoue, S.; Suginaka, H. Purification and molecular characterization of glycylglycine endopeptidase produced by Staphylococcus capitis EPK1. Journal of bacteriology 1997, 179, 1193-1202. [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.C.; Foster-Frey, J.; Donovan, D.M. The phage K lytic enzyme LysK and lysostaphin act synergistically to kill MRSA. FEMS microbiology letters 2008, 287, 185-191. [CrossRef]

- Sundarrajan, S.; Raghupatil, J.; Vipra, A.; Narasimhaswamy, N.; Saravanan, S.; Appaiah, C.; Poonacha, N.; Desai, S.; Nair, S.; Bhatt, R.N. Bacteriophage-derived CHAP domain protein, P128, kills Staphylococcus cells by cleaving interpeptide cross-bridge of peptidoglycan. Microbiology 2014, 160, 2157-2169. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Ryu, S. Characterization of a novel cell wall binding domain-containing Staphylococcus aureus endolysin LysSA97. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2017, 101, 147-158. [CrossRef]

- Altermann, E.; Schofield, L.R.; Ronimus, R.S.; Beattie, A.K.; Reilly, K. Inhibition of rumen methanogens by a novel archaeal lytic enzyme displayed on tailored bionanoparticles. Frontiers in microbiology 2018, 2378. [CrossRef]

- Swift, S.M.; Waters, J.J.; Rowley, D.T.; Oakley, B.B.; Donovan, D.M. Characterization of two glycosyl hydrolases, putative prophage endolysins, that target Clostridium perfringens. FEMS microbiology letters 2018, 365, fny179. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, H.G.; Kwon, I.; Seo, J. Characterization of endolysin LyJH307 with antimicrobial activity against Streptococcus bovis. Animals 2020, 10, 963. [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, W.; Blanot, D.; De Pedro, M.A. Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2008, 32, 149-167, . [CrossRef]

- Sauvage, E.; Kerff, F.; Terrak, M.; Ayala, J.A.; Charlier, P. The penicillin-binding proteins: structure and role in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. FEMS microbiology reviews 2008, 32, 234-258. [CrossRef]

- Fishovitz, J.; Hermoso, J.A.; Chang, M.; Mobashery, S. Penicillin-binding protein 2a of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. IUBMB Life 2014, 66, 572-577, . [CrossRef]

- Blázquez, B.; Llarrull, L.I.; Luque-Ortega, J.R.; Alfonso, C.; Boggess, B.; Mobashery, S. Regulation of the expression of the β-lactam antibiotic-resistance determinants in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Biochemistry 2014, 53, 1548-1550. [CrossRef]

- Ryffel, C.; Kayser, F.H.; Berger-Bächi, B. Correlation between regulation of mecA transcription and expression of methicillin resistance in staphylococci. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 1992, 36, 25-31. [CrossRef]

- Francois, P.; Bento, M.; Renzi, G.; Harbarth, S.; Pittet, D.; Schrenzel, J. Evaluation of three molecular assays for rapid identification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of clinical microbiology 2007, 45, 2011-2013. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Tong, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, D.; Wang, L.; Fan, H. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in healthy Chinese population: a system review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0223599. [CrossRef]

- de Kraker, M.E.A.; Jarlier, V.; Monen, J.C.M.; Heuer, O.E.; van de Sande, N.; Grundmann, H. The changing epidemiology of bacteraemias in Europe: trends from the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2013, 19, 860-868, . [CrossRef]

- Garoy, E.Y.; Gebreab, Y.B.; Achila, O.O.; Tekeste, D.G.; Kesete, R.; Ghirmay, R.; Kiflay, R.; Tesfu, T. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): prevalence and antimicrobial sensitivity pattern among patients—a multicenter study in Asmara, Eritrea. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology 2019. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Blanco, M.; Mejía, C.; Isturiz, R.; Alvarez, C.; Bavestrello, L.; Gotuzzo, E.; Labarca, J.; Luna, C.M.; Rodríguez-Noriega, E.; Salles, M.J. Epidemiology of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Latin America. International journal of antimicrobial agents 2009, 34, 304-308. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.N.; Ocampo, A.M.; Vanegas, J.M.; Rodriguez, E.A.; Mediavilla, J.R.; Chen, L.; Muskus, C.E.; A. Vélez, L.; Rojas, C.; Restrepo, A.V. CC8 MRSA strains harboring SCC mec type IVc are predominant in Colombian hospitals. PLoS One 2012, 7, e38576. [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Karageorgopoulos, D.E.; Leptidis, J.; Korbila, I.P. MRSA in Africa: filling the global map of antimicrobial resistance. PloS one 2013, 8, e68024. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, A.; Rawlings, N.D. The CHAP domain: a large family of amidases including GSP amidase and peptidoglycan hydrolases. Trends in biochemical sciences 2003, 28, 234-237. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H.; Melo, L.D.; Santos, S.B.; Nóbrega, F.L.; Ferreira, E.C.; Cerca, N.; Azeredo, J.; Kluskens, L.D. Molecular aspects and comparative genomics of bacteriophage endolysins. Journal of virology 2013, 87, 4558-4570. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, B.J.; Eck, M.J. SH3 domains: minding your p's and q's. Current Biology 1995, 5, 364-367. [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.C.; Foster-Frey, J.; Stodola, A.J.; Anacker, D.; Donovan, D.M. Differentially conserved staphylococcal SH3b_5 cell wall binding domains confer increased staphylolytic and streptolytic activity to a streptococcal prophage endolysin domain. Gene 2009, 443, 32-41. [CrossRef]

- Ponting, C.P.; Aravind, L.; Schultz, J.; Bork, P.; Koonin, E.V. Eukaryotic Signalling Domain Homologues in Archaea and Bacteria. Ancient Ancestry and Horizontal Gene Transfer. Journal of Molecular Biology 1999, 289, 729-745, . [CrossRef]

- Baba, T.; Schneewind, O. Target cell specificity of a bacteriocin molecule: a C-terminal signal directs lysostaphin to the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. The EMBO journal 1996, 15, 4789-4797. [CrossRef]

- Low, L.Y.; Yang, C.; Perego, M.; Osterman, A.; Liddington, R.C. Structure and lytic activity of a Bacillus anthracis prophage endolysin. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, 35433-35439. [CrossRef]

- Loessner, M.J.; Kramer, K.; Ebel, F.; Scherer, S. C-terminal domains of Listeria monocytogenes bacteriophage murein hydrolases determine specific recognition and high-affinity binding to bacterial cell wall carbohydrates. Molecular microbiology 2002, 44, 335-349. [CrossRef]

- Fischetti, V.A. Bacteriophage lysins as effective antibacterials. Current opinion in microbiology 2008, 11, 393-400. [CrossRef]

- Díez-Martínez, R.; de Paz, H.; Bustamante, N.; García, E.; Menéndez, M.; García, P. Improving the lethal effect of Cpl-7, a pneumococcal phage lysozyme with broad bactericidal activity, by inverting the net charge of its cell wall-binding module. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2013, 57, 5355-5365. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Fang, J. Discrimination of soluble and aggregation-prone proteins based on sequence information. Molecular BioSystems 2013, 9, 806-811. [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, A.; Sindhu, R.; Binod, P.; Sukumaran, R.K.; Pandey, A. Strategies for design of improved biocatalysts for industrial applications. Bioresource technology 2017, 245, 1304-1313. [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.-C.; Liang, P.-H.; Shih, Y.-P.; Yang, U.-C.; Lin, W.-c.; Hsu, C.-N. Learning to predict expression efficacy of vectors in recombinant protein production. BMC bioinformatics 2010, 11, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Musil, M.; Konegger, H.; Hon, J.; Bednar, D.; Damborsky, J. Computational design of stable and soluble biocatalysts. Acs Catalysis 2018, 9, 1033-1054. [CrossRef]

- Hebditch, M.; Carballo-Amador, M.A.; Charonis, S.; Curtis, R.; Warwicker, J. Protein–Sol: a web tool for predicting protein solubility from sequence. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3098-3100. [CrossRef]

- Hon, J.; Marusiak, M.; Martinek, T.; Kunka, A.; Zendulka, J.; Bednar, D.; Damborsky, J. SoluProt: prediction of soluble protein expression in Escherichia coli. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 23-28. [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, D.; Orlando, G.; Fariselli, P.; Moreau, Y. Insight into the protein solubility driving forces with neural attention. PLoS computational biology 2020, 16, e1007722. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Huang, J.; Fan, Y.; Yao, Z.; Ye, X.; Chen, S. Phenotypic and molecular characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in slaughterhouse pig-related workers and control workers in Guangdong Province, China. Epidemiology & Infection 2017, 145, 1843-1851. [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Liu, W.; Fan, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Yao, Z.; Chen, S. Frequency-risk and duration-risk relations between occupational livestock contact and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage among workers in Guangdong, China. American Journal of Infection Control 2015, 43, 676-681. [CrossRef]

- Vanderhaeghen, W.; Piepers, S.; Leroy, F.; Van Coillie, E.; Haesebrouck, F.; De Vliegher, S. Invited review: effect, persistence, and virulence of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species associated with ruminant udder health. Journal of Dairy Science 2014, 97, 5275-5293. [CrossRef]

- Thorberg, B.-M.; Danielsson-Tham, M.-L.; Emanuelson, U.; Waller, K.P. Bovine subclinical mastitis caused by different types of coagulase-negative staphylococci. Journal of dairy science 2009, 92, 4962-4970. [CrossRef]

- Supré, K.; Haesebrouck, F.; Zadoks, R.; Vaneechoutte, M.; Piepers, S.; De Vliegher, S. Some coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species affect udder health more than others. Journal of dairy science 2011, 94, 2329-2340. [CrossRef]

- De Visscher, A.; Piepers, S.; Haesebrouck, F.; De Vliegher, S. Intramammary infection with coagulase-negative staphylococci at parturition: Species-specific prevalence, risk factors, and effect on udder health. Journal of Dairy Science 2016, 99, 6457-6469. [CrossRef]

- Schleifer, K.H.; Kandler, O. Peptidoglycan types of bacterial cell walls and their taxonomic implications. Bacteriological reviews 1972, 36, 407-477. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Z.; Fujiwara, T.; Komatsuzawa, H.; Sugai, M.; Sakon, J. Cell wall-targeting domain of glycylglycine endopeptidase distinguishes among peptidoglycan cross-bridges. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006, 281, 549-558. [CrossRef]

- Gründling, A.; Schneewind, O. Cross-linked peptidoglycan mediates lysostaphin binding to the cell wall envelope of Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of bacteriology 2006, 188, 2463-2472. [CrossRef]

- Donovan, D.M.; Lardeo, M.; Foster-Frey, J. Lysis of staphylococcal mastitis pathogens by bacteriophage phi11 endolysin. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2006, 265, 133-139, . [CrossRef]

- Donovan, D.M.; Dong, S.; Garrett, W.; Rousseau, G.M.; Moineau, S.; Pritchard, D.G. Peptidoglycan Hydrolase Fusions Maintain Their Parental Specificities. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2006, 72, 2988-2996, . [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, B.; Chang, Y.-S.; Gage, D.; Tomasz, A. Peptidoglycan composition of a highly methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain. The role of penicillin binding protein 2A. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1992, 267, 11248-11254. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.K.; Bartels, D.; Best, A.A.; DeJongh, M.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Formsma, K.; Gerdes, S.; Glass, E.M.; Kubal, M. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 2008, 9, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Lu, S.; Chitsaz, F.; Geer, L.Y.; Geer, R.C.; He, J.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I. CDD: NCBI's conserved domain database. Nucleic acids research 2015, 43, D222-D226. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis; springer: 2016.

- Team, R.C. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2013.

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular biology and evolution 2013, 30, 772-780. [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PloS one 2010, 5, e9490. [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Smith, D.K.; Zhu, H.; Guan, Y.; Lam, T.T.Y. ggtree: an R package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2017, 8, 28-36. [CrossRef]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold-Making protein folding accessible to all. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Couch, G.S.; Croll, T.I.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Science 2021, 30, 70-82. [CrossRef]

- Mónico, A.; Martínez-Senra, E.; Zorrilla, S.; Pérez-Sala, D. Drawbacks of dialysis procedures for removal of EDTA. PloS one 2017, 12, e0169843. [CrossRef]

- Ogle, D.; Ogle, M.D. Package ‘FSA’. CRAN Repos 2017, 1-206.

| Group2 | Name | Amino acids | Soluprot | Protein-Sol | SKADE | Sum7 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility3 | Z-score4 | Scaled-sol5 | Z-score4 | Solubility6 | Z-score4 | |||||||||

| Group 3 | Putative endolysin 177 | 249 | 0.569 | -0.269 | 0.680 | 5.559 | 0.186 | -1.638 | 3.652 | |||||

| Group 1 | Putative endolysin 117 | 481 | 0.735 | 1.114 | 0.354 | -0.276 | 0.327 | 0.903 | 1.741 | |||||

| Group 1 | Putative endolysin 129 | 481 | 0.776 | 1.465 | 0.343 | -0.473 | 0.311 | 0.610 | 1.601 | |||||

| Group 1 | Putative endolysin 121 | 481 | 0.749 | 1.239 | 0.332 | -0.670 | 0.330 | 0.951 | 1.520 | |||||

| Group 1 | Putative endolysin 159 | 481 | 0.718 | 0.973 | 0.332 | -0.670 | 0.343 | 1.182 | 1.485 | |||||

| Group 1 | Putative endolysin 132 | 481 | 0.750 | 1.241 | 0.343 | -0.473 | 0.312 | 0.631 | 1.398 | |||||

| Group 1 | Putative endolysin 147 | 481 | 0.727 | 1.052 | 0.332 | -0.670 | 0.332 | 0.981 | 1.364 | |||||

| Group 1 | Putative endolysin 143 | 481 | 0.741 | 1.167 | 0.322 | -0.849 | 0.334 | 1.015 | 1.333 | |||||

| Group 1 | Putative endolysin 174 | 481 | 0.722 | 1.006 | 0.332 | -0.670 | 0.332 | 0.986 | 1.322 | |||||

| Group 1 | Putative endolysin 150 | 481 | 0.732 | 1.092 | 0.322 | -0.849 | 0.336 | 1.063 | 1.306 | |||||

| Bacterial strains | Purpose | Growth condition1 |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus (NCCP 16830) | Indicator strain | BHI broth |

| Escherichia coli DH5α | Cloning host | LB broth |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | Expression host | LB broth |

| S. aureus (KVCC-BA0500624) | Lytic spectrum | BHI broth |

| MRSA (NCCP 14567) | Lytic spectrum | BHI broth |

| MRSA (NCCP 14754) | Lytic spectrum | BHI broth |

| Staphylococcus hyicus (KVCC-BA0001860) | Lytic spectrum | BHI broth |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (KVCC-BA0001452) | Lytic spectrum | BHI broth |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus (NCCP 14693) | Lytic spectrum | BHI broth |

| Staphylococcus simulans (NCCP 16236) | Lytic spectrum | BHI broth |

| Staphylococcus warneri (NCCP 16234) | Lytic spectrum | BHI broth |

| Staphylococcus chromogenes (KCTC 3579) | Lytic spectrum | BHI broth |

| Staphylococcus xylosus (KCCM 40887) | Lytic spectrum | BHI broth |

| Streptococcus agalactiae (NCCP 14729) | Lytic spectrum | BHI broth |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).