Submitted:

31 January 2023

Posted:

02 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

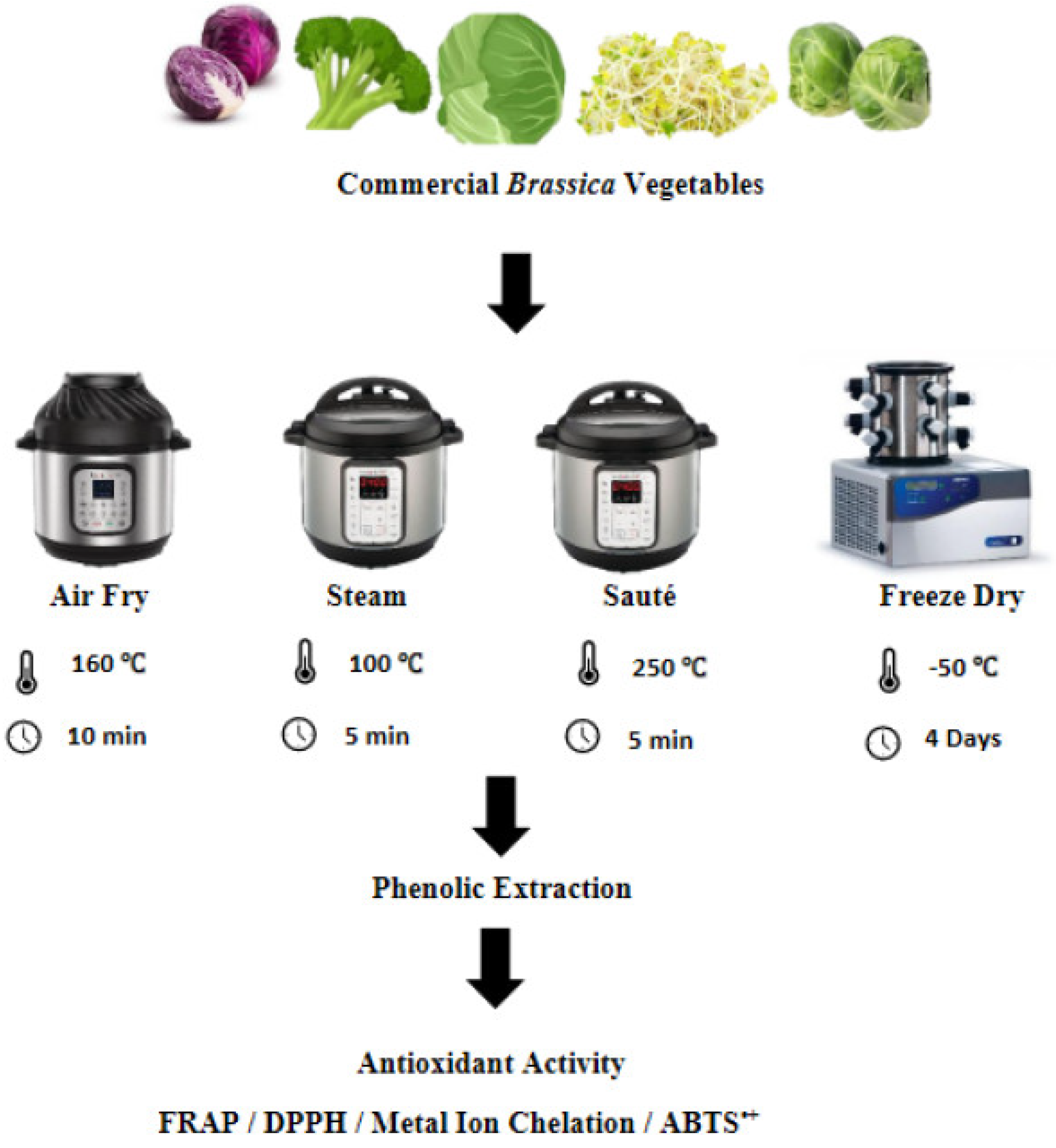

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Chemicals

2.3. Application of Different Processing Techniques to Optimize the Phenolic Content

2.3.1. Freeze Drying Treatment

2.3.2. Pressurized Steam Treatment

2.3.3. Air Frying Treatment

2.3.4. Stir-Frying/Sautéing of the Vegetables

2.4. Sample Preparation

2.4.1. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Phenolic Compounds

2.4.2. Phenolic Extraction for Antioxidant Assays

2.5. Antioxidant Activity of the Vegetables

2.5.1. Assessment of Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.5.2. Assessment of Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

2.5.3. DPPH Free Radical–Scavenging Assay

2.5.4. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power Assay (FRAP Assay)

2.5.5. Ferrous-Ion-Chelating Activity Assay Antioxidant Capacity

2.5.6. Total Antioxidant Capacity Assay (TAC)

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

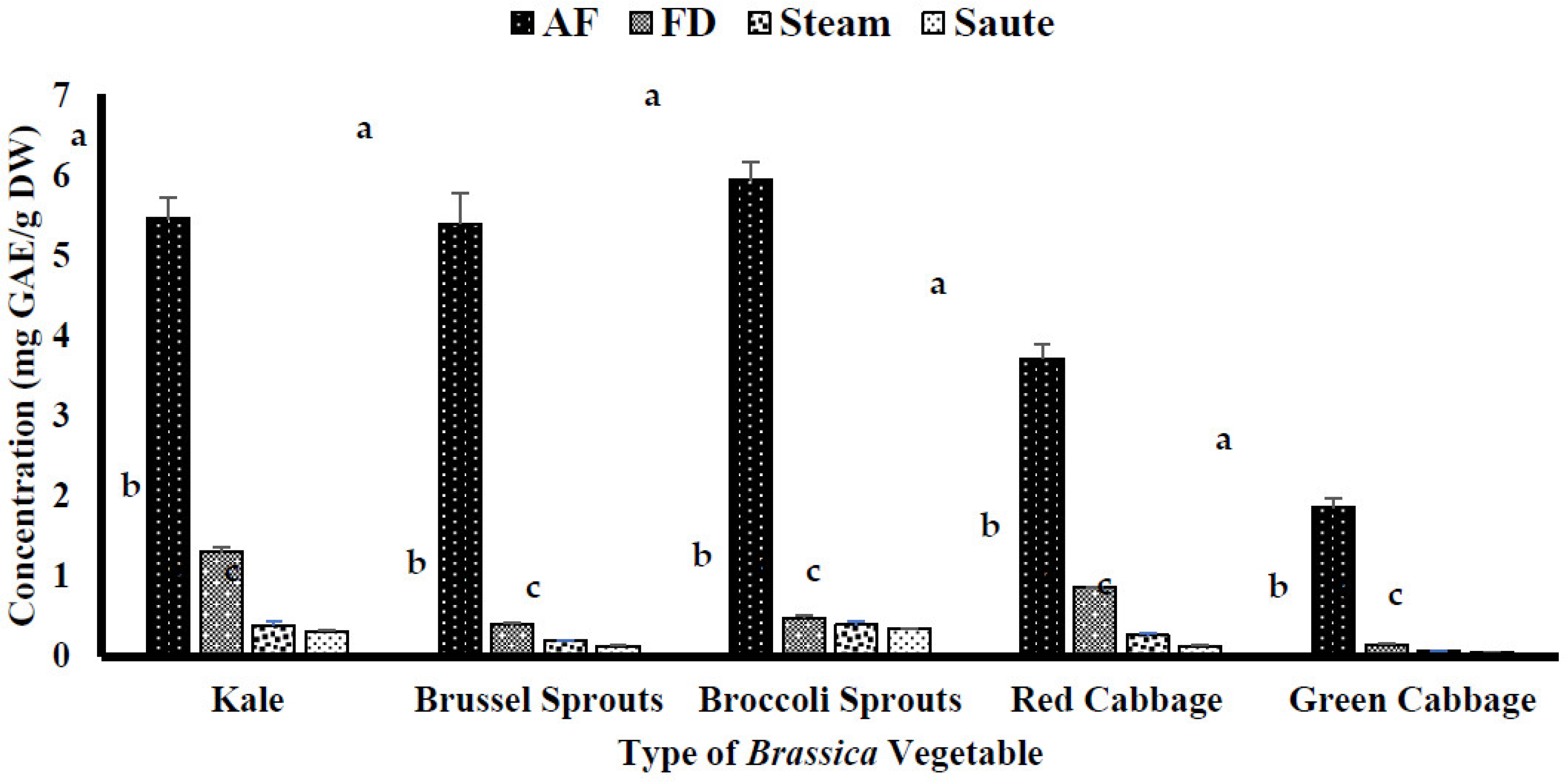

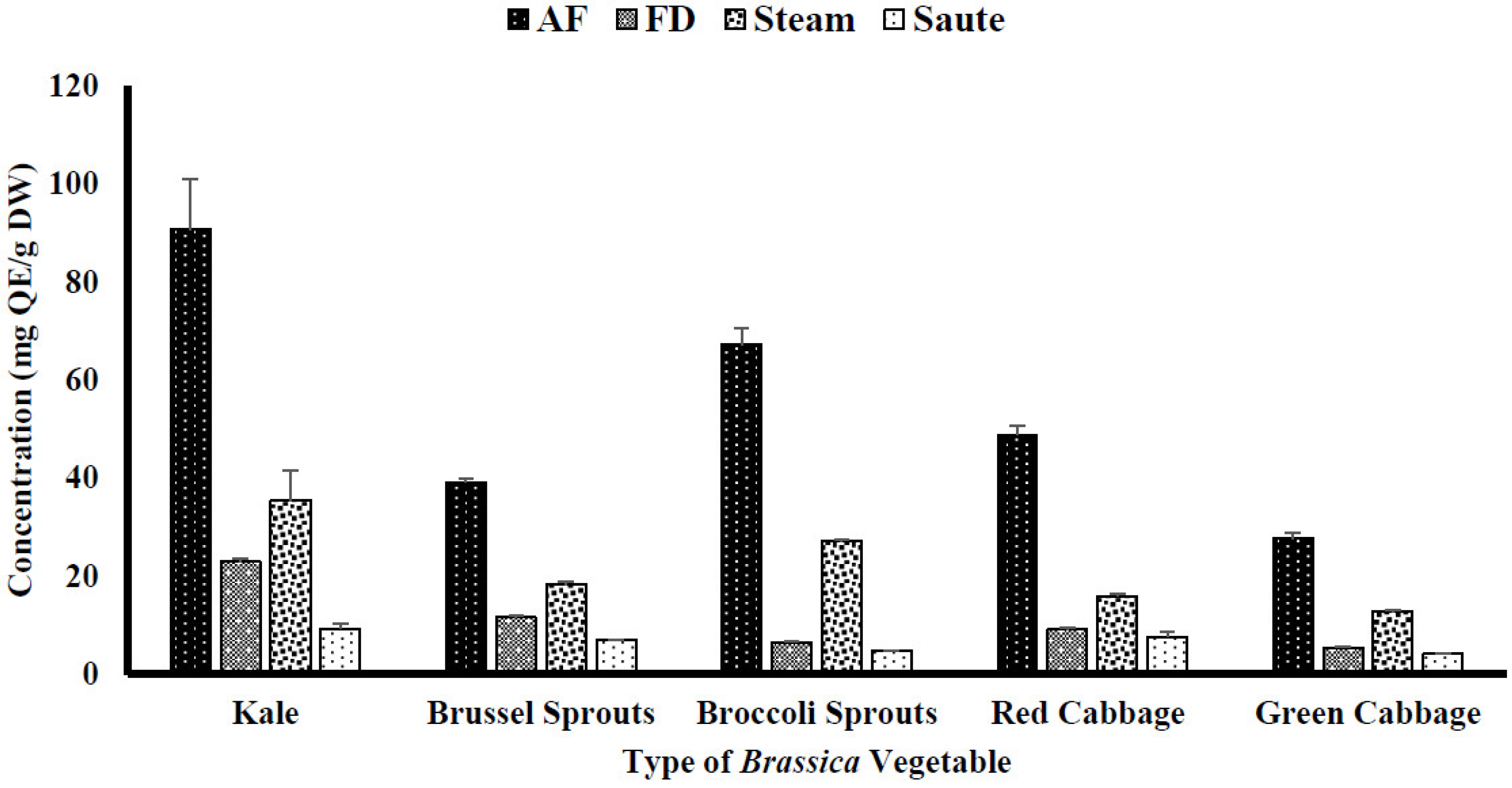

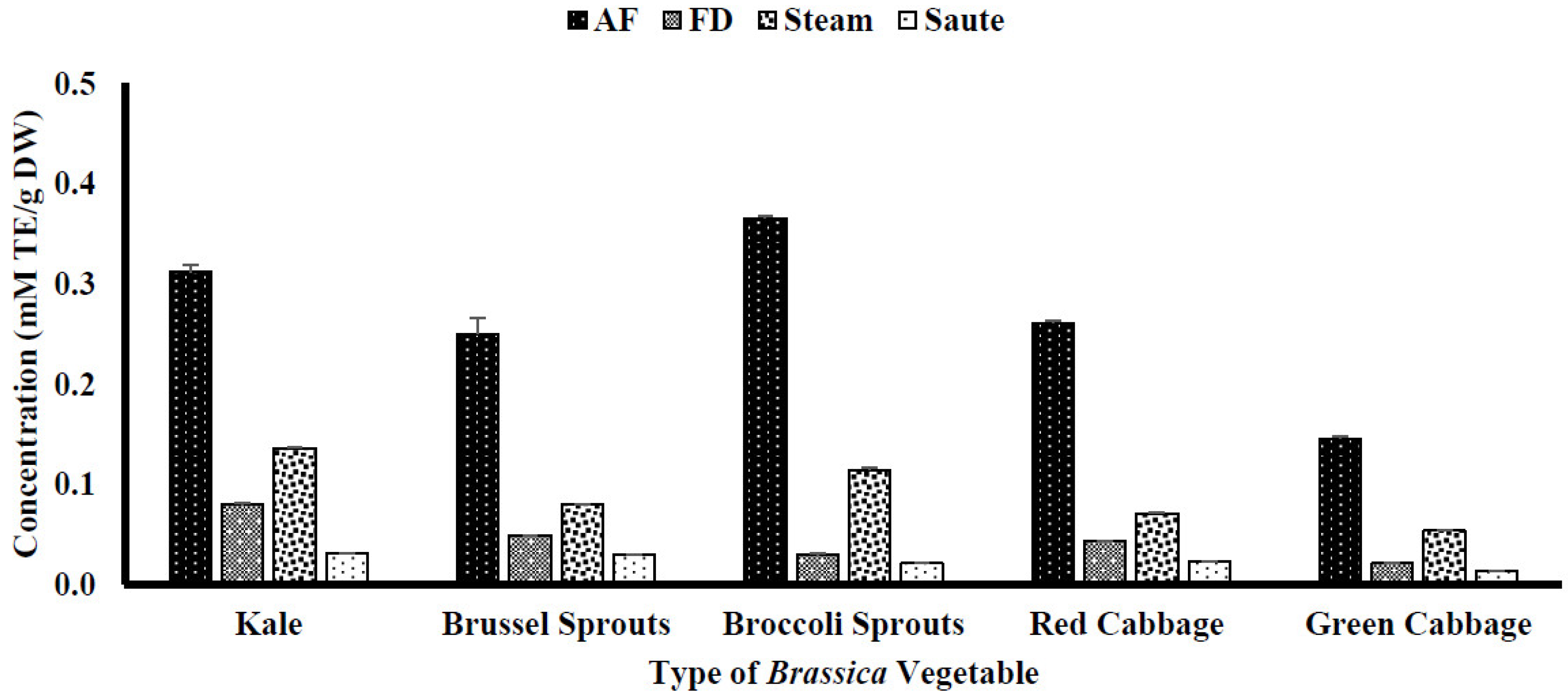

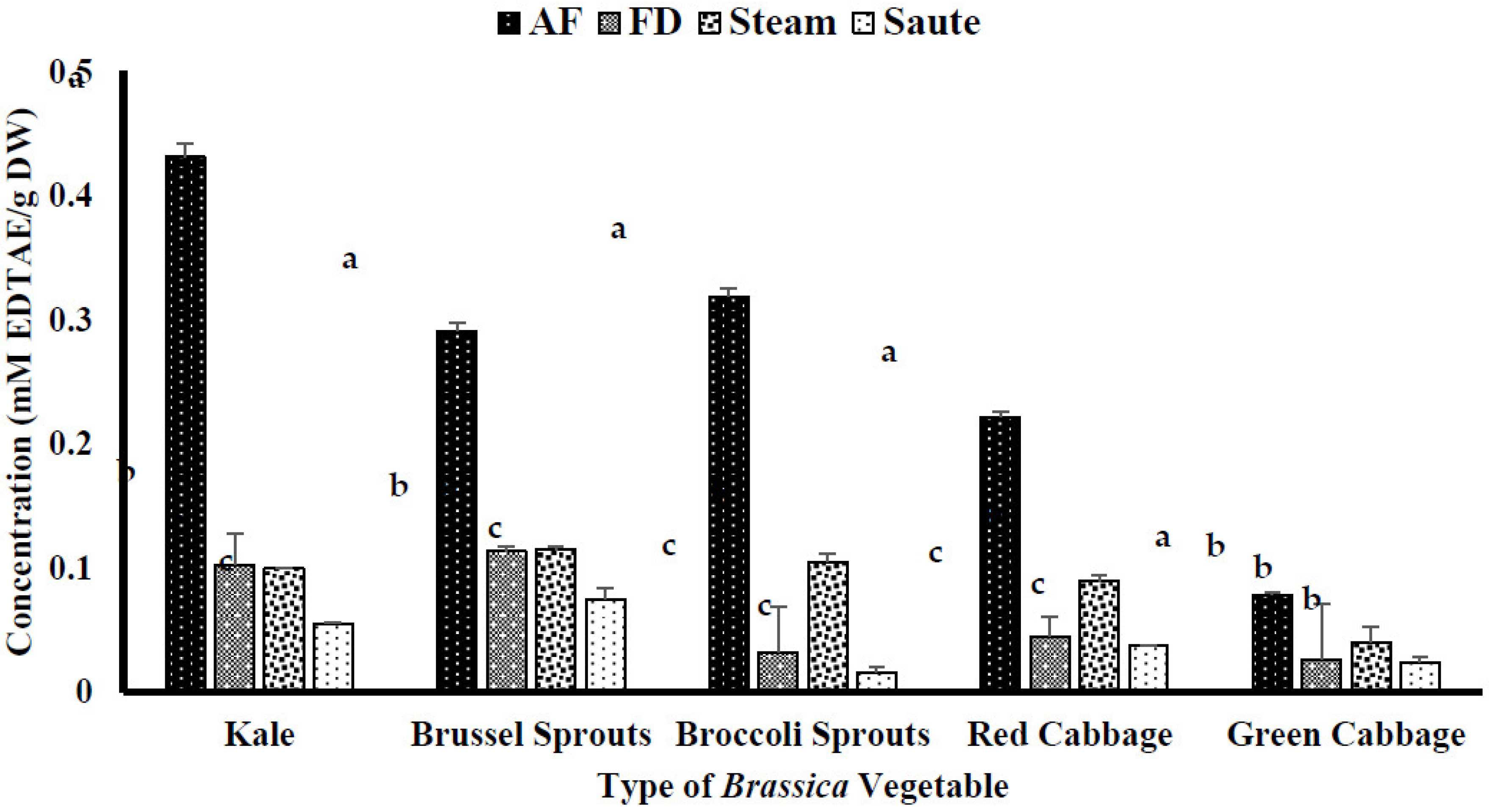

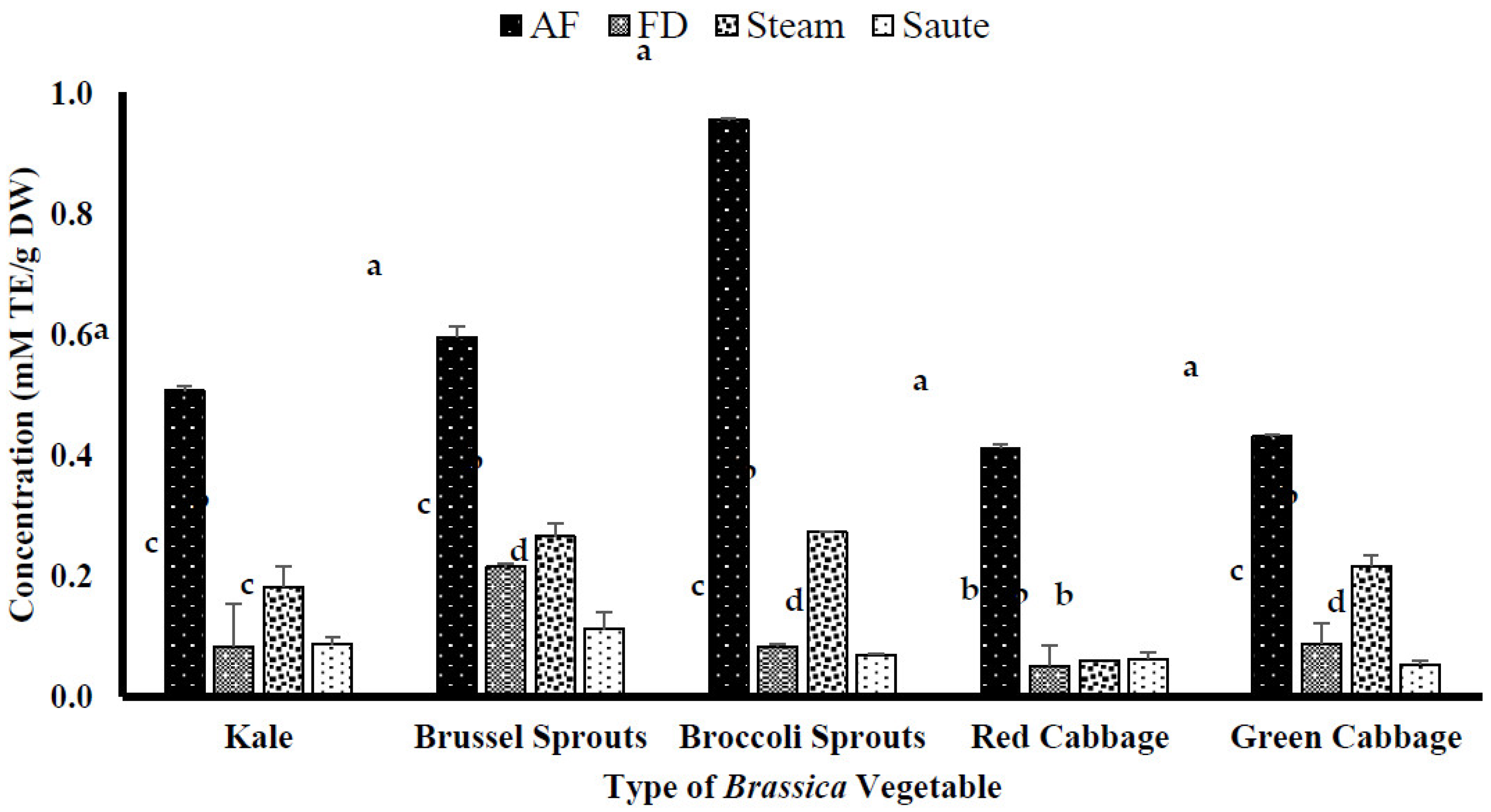

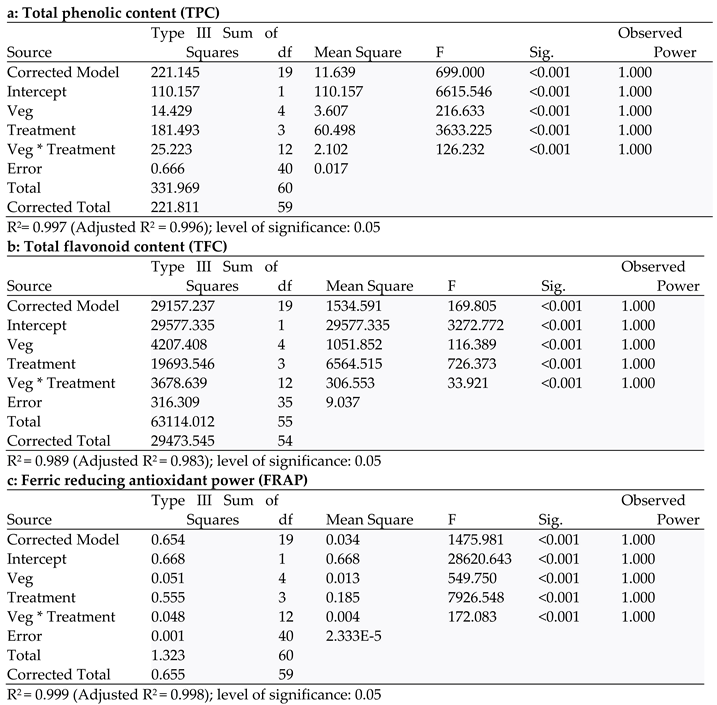

4.1. Impact of Thermal Processing on Total Phenolic (TPC) and Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

4.2. Impact of Thermal Processing on Antioxidant Activity

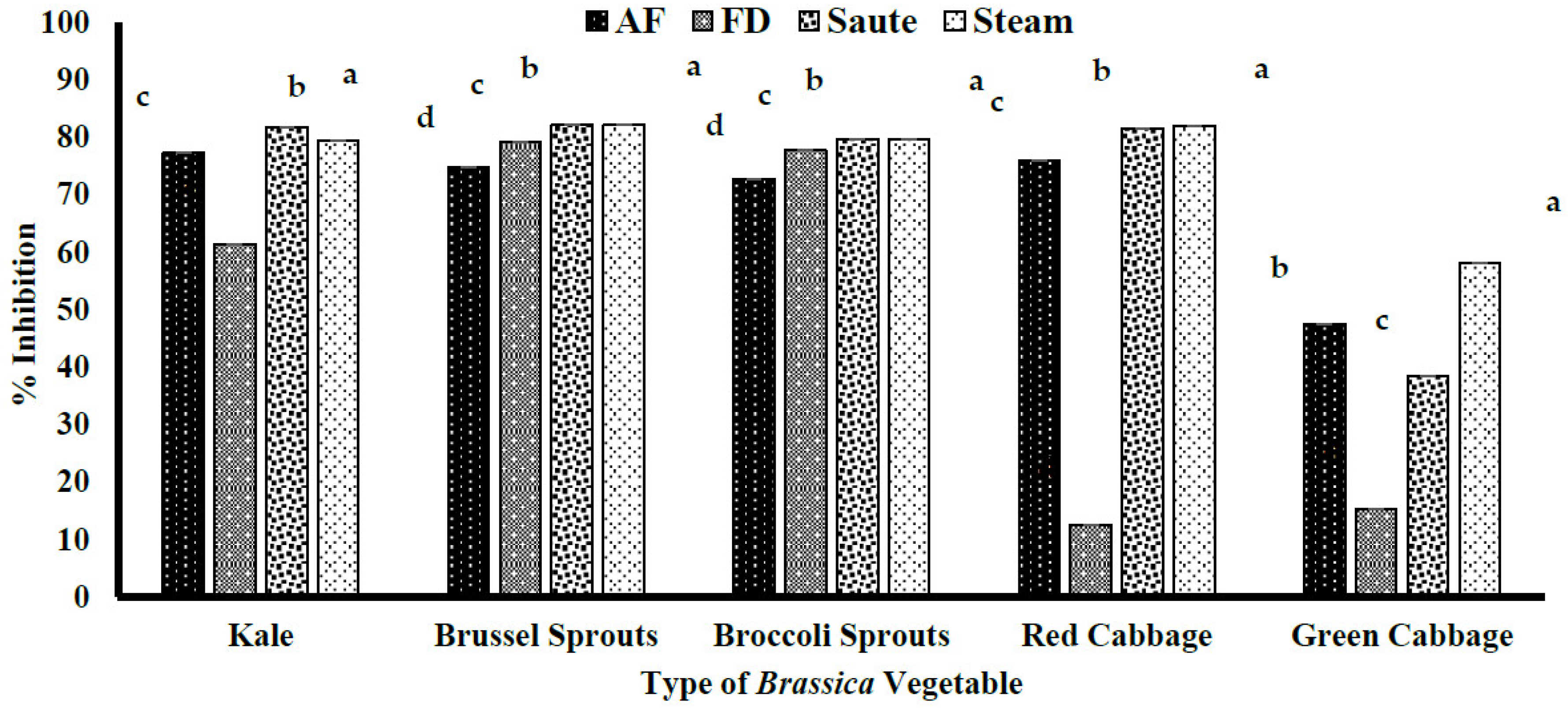

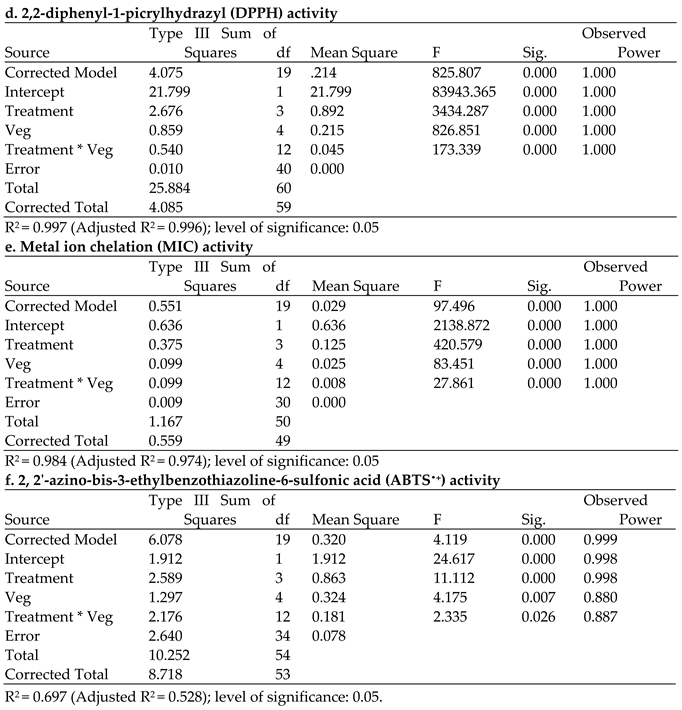

4.2.1. DPPH Free Radical–Scavenging Activity of the Brassica Vegetables

4.2.2. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) of the Brassica Vegetables

4.2.3. Metal Ion-Chelating Activity (MIC)

4.2.4. Total Antioxidant Capacity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nagata, N.; Xu, L.; Kohno, S.; Ushida, Y.; Aoki, Y.; Umeda, R.; Fuke, N.; Zhuge, F.; Ni, Y.; Nagashimada, M.; et al. Glucoraphanin Ameliorates Obesity and Insulin Resistance Through Adipose Tissue Browning and Reduction of Metabolic Endotoxemia in Mice. Diabetes 2017, 66, 1222–1236. [CrossRef]

- Tanongkankit, Y.; Chiewchan, N.; Devahastin, S. Effect of Processing on Antioxidants and Their Activity in Dietary Fiber Powder from Cabbage Outer Leaves. 2010, 28, 1063–1071. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Nagata, N.; Ota, T. Glucoraphanin: A Broccoli Sprout Extract That Ameliorates Obesity-Induced Inflammation and Insulin Resistance. Adipocyte 2018, 7, 218. [CrossRef]

- Sikora Elżbieta; Bodziarczyk Izabela Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Kale (Brassica Oleracea L. Var. Acephala) Raw and Cooked—PubMed Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22744944/ (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Fiol, M.; Weckmüller, A.; Neugart, S.; Schreiner, M.; Rohn, S.; Krumbein, A.; Kroh, L.W. Thermal-Induced Changes of Kale’s Antioxidant Activity Analyzed by HPLC–UV/Vis-Online-TEAC Detection. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 857–865. [CrossRef]

- OCN Opaskwayak Health Authority 2016 Adult Health Survey; 2017.

- Fadairo, O.; Nandasiri, R.; Alashi, A.M.; Eskin, N.A.M.; Thiyam-Höllander, U. Air Frying Pretreatment and the Recovery of Lipophilic Sinapates from the Oil Fraction of Mustard Samples. J. Food Sci. 2021, 1750-3841.15861. [CrossRef]

- Fadairo, O.S.; Nandasiri, R.; Nguyen, T.; Eskin, N.A.M.; Aluko, R.E.; Scanlon, M.G. Improved Extraction Efficiency and Antioxidant Activity of Defatted Canola Meal Extract Phenolic Compounds Obtained from Air-Fried Seeds. 2022.

- Lafarga, T.; Bobo, G.; Viñas, I.; Collazo, C.; Aguiló-Aguayo, I. Effects of Thermal and Non-Thermal Processing of Cruciferous Vegetables on Glucosinolates and Its Derived Forms. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 1973–1981.

- O. Mwebi, N.; M.O. Ogendi, B. Effect of Boiling, Steaming, Stir-Frying and Microwave Cooking on the Antioxidant Potential of Peppers of Varying Pungency. http://www.editorialmanager.com/cogentagri 2020, 6. [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.K.; Juneja, L.R.; Isobe, S.; Tsushida, T. Steam Processed Broccoli (Brassica Oleracea) Has Higher Antioxidant Activity in Chemical and Cellular Assay Systems. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 263–269. [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Oliviero, T.; van der Sman, R.G.M.; Verkerk, R.; Dekker, M.; van Boxtel, A.J.B. Impact of Different Drying Trajectories on Degradation of Nutritional Compounds in Broccoli (Brassica Oleracea Var. Italica). LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 59, 189–195. [CrossRef]

- Lohachoompol, V.; Srzednicki, G.; Craske, J. The Change of Total Anthocyanins in Blueberries and Their Antioxidant Effect After Drying and Freezing. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2004, 2004, 248–252. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, J.; Yu, D.; Chen, S.; Ye, X.; Zhang, Z. Analysis of Processing Effects on Glucosinolate Profiles in Red Cabbage by LC-MS/MS in Multiple Reaction Monitoring Mode. Molecules 2021, 26. [CrossRef]

- Korus, A.; Słupski, J.; Gebczyński, P.; Banaś, A. Effect of Preliminary Processing and Method of Preservation on the Content of Glucosinolates in Kale (Brassica Oleracea L. Var. Acephala) Leaves. LWT 2014, 59, 1003–1008. [CrossRef]

- Nandasiri, R.; Imran, A.; Thiyam-Holländer, U.; Eskin, N.A.M. Rapidoxy® 100: A Solvent-Free Pre-Treatment for Production of Canolol. Front. Nutr. 2021, 0, 399. [CrossRef]

- Nugrahedi, P.Y.; Oliviero, T.; Heising, J.K.; Dekker, M.; Verkerk, R. Stir-Frying of Chinese Cabbage and Pakchoi Retains Health-Promoting Glucosinolates. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2017, 72, 439–444. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shi, J.; Wan, J.; Pham, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, J.; Yu, L.; Luo, Y.; Wang, T.T.Y.; Chen, P. Profiling of Polyphenols and Glucosinolates in Kale and Broccoli Microgreens Grown under Chamber and Windowsill Conditions by Ultrahigh-Performance Liquid Chromatography High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 101–113. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zago, E.; Nandasiri, R.; Khattab, R.; Eskin, N.A.M.; Eck, P.; Thiyam-Holländer, U. Effect of Solvent, Preheating Temperature, and Time on the Ultrasonic Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Cold-Pressed Hempseed Cake. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2018, 95. [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16.

- Thiyam, U.; Stöckmann, H.; Zum Felde, T.; Schwarz, K. Antioxidative Effect of the Main Sinapic Acid Derivatives from Rapeseed and Mustard Oil By-Products. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2006, 108, 239–248. [CrossRef]

- Zhishen, J.; Mengcheng, T.; Jianming, W. The Determination of Flavonoid Contents in Mulberry and Their Scavenging Effects on Superoxide Radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [CrossRef]

- Nandasiri, R.; Eskin, N.A.M.; Thiyam-Höllander, U. Antioxidative Polyphenols of Canola Meal Extracted by High Pressure: Impact of Temperature and Solvents. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 3117–3128. [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [CrossRef]

- Dinis, T.C.; Maderia, V.M.; Almeida, L.M. Action of Phenolic Derivatives (Acetaminophen, Salicylate, and 5-Aminosalicylate) as Inhibitors of Membrane Lipid Peroxidation and as Peroxyl Radical Scavengers. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994, 315, 161–169.

- Pallant, J.” SPSS Survival Manual : A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS Version 18; 4th Editio.; Open University Press, McGraw-Hill Education: Maidenhead, Berkshire, England, 2011; ISBN 13: 978-0-33-524239-9 (pb).

- Chandrasekara, A.; Shahidi, F. Content of Insoluble Bound Phenolics in Millets and Their Contribution to Antioxidant Capacity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 6706–6714. [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, F.A.; Hayirlioglu-Ayaz, S.; Alpay-Karaoglu, S.; Grúz, J.; Valentová, K.; Ulrichová, J.; Strnad, M. Phenolic Acid Contents of Kale (Brassica Oleraceae L. Var. Acephala DC.) Extracts and Their Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 19–25. [CrossRef]

- APDS What Is Rapid Air Technology? Available online: http://apds.nl/development-en/what-is-rapid-air-technology/ (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Nandasiri, R.; Zago, E.; Thiyam-Holländer, U.; Eskin, N.A.M. Attenuation of Sinapic Acid and Sinapine-Derived Flavor-Active Compounds Using a Factorial-Based Pressurized High-Temperature Processing. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2021, 98, 779–794. [CrossRef]

- Nandasiri, R.; Eskin, N.A.M.; Komatsu, E.; Perreault, H.; Thiyam-Holländer, U. Valorization of Canola By-Products: Concomitance of Flavor-Active Bitter Phenolics Using Pressurized Heat Treatments. LWT 2021, 138, 110397. [CrossRef]

- Paciulli, M.; Dall’Asta, C.; Rinaldi, M.; Pellegrini, N.; Pugliese, A.; Chiavaro, E. Application and Optimisation of Air–Steam Cooking on Selected Vegetables: Impact on Physical and Antioxidant Properties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 2267–2276. [CrossRef]

- Lafarga, T.; Bobo, G.; Viñas, I.; Zudaire, L.; Simó, J.; Aguiló-Aguayo, I. Steaming and Sous-Vide: Effects on Antioxidant Activity, Vitamin C, and Total Phenolic Content of Brassica Vegetables. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2018, 13, 134–139. [CrossRef]

- Cieślik, E.; Leszczyńska, T.; Filipiak-Florkiewicz, A.; Sikora, E.; Pisulewski, P.M. Effects of Some Technological Processes on Glucosinolate Contents in Cruciferous Vegetables. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 976–981. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.; Eck, P.; Chen, S.; Corpe, C.P.; Lee, J.-H.; Kruhlak, M.; Levine, M. Inhibition of the Intestinal Glucose Transporter GLUT2 by Flavonoids. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 366–377. [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C.A.; Miller, N.J.; Paganga, G. Structure-Antioxidant Activity Relationships of Flavonoids and Phenolic Acids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 20, 933–956. [CrossRef]

- Um, M.; Han, T.H.; Lee, J.W. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction and Antioxidant Activity of Phenolic and Flavonoid Compounds and Ascorbic Acid from Rugosa Rose (Rosa Rugosa Thunb.) Fruit. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 27, 375–382. [CrossRef]

- Irakli, M.; Chatzopoulou, P.; Ekateriniadou, L. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Phenolic Compounds: Oleuropein, Phenolic Acids, Phenolic Alcohols and Flavonoids from Olive Leaves and Evaluation of Its Antioxidant Activities. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 124, 382–388. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Z.; Harnly, J.M. Identification of the Phenolic Components of Collard Greens, Kale, and Chinese Broccoli. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 7401–7408.

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food Sources and Bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 727–747.

- Ferreira, O.; Pinho, P. Solubility of Flavonoids in Pure Solvents. 2023, 21, 41. [CrossRef]

- Lemańska, K.; Szymusiak, H.; Tyrakowska, B.; Zieliński, R.; Soffers, A.E.; Rietjens, I.M. The Influence of PH on Antioxidant Properties and the Mechanism of Antioxidant Action of Hydroxyflavones. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001, 31, 869–881. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, Z. Concurrent Extraction and Transformation of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds from Rapeseed Meal Using Pressurized Solvent Extraction System. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 94, 152–159. [CrossRef]

- Zago, E.; Nandasiri, R.; Thiyam-Holländer, U.; Michael Eskin, N.A. Influence of Thermal Treatments on the Antioxidant Activity of Hemp Cake Polar Extracts. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 3256–3265.

- Tavasi, V.; Bettens, R.P.A.; Leong, L.P. Temperature and Solvent Effects on Radical Scavenging Ability of Phenols. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 3068–3077. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Ji, H.F. How Vitamin E Scavenges DPPH Radicals in Polar Protic Media. New J. Chem. 2006, 30, 503–504. [CrossRef]

- Friaa, O.; Brault, D. Kinetics of the Reaction between the Antioxidant Trolox® and the Free Radical DPPH˙ in Semi-Aqueous Solution. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006, 4, 2417–2423. [CrossRef]

- Turkmen, N.; Sari, F.; Velioglu, Y.S. The Effect of Cooking Methods on Total Phenolics and Antioxidant Activity of Selected Green Vegetables. Food Chem. 2005, 93, 713–718. [CrossRef]

- López-Berenguer, C.; Carvajal, M.; Moreno, D.A.; García-Viguera, C. Effects of Microwave Cooking Conditions on Bioactive Compounds Present in Broccoli Inflorescences. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 10001–10007.

- Ajila, C.M.; Brar, S.K.; Verma, M.; Tyagi, R.D.; Godbout, S.; Valéro, J.R. Extraction and Analysis of Polyphenols: Recent Trends. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2011, 31, 227–249. [CrossRef]

- Francisco, M.; Velasco, P.; Moreno, D.A.; García-Viguera, C.; Cartea, M.E. Cooking Methods of Brassica Rapa Affect the Preservation of Glucosinolates, Phenolics and Vitamin C. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1455–1463. [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Sharma, A.; Rai, P.K.; Kumar, D. Effect of Microwave Pre-Treatment on Quality Parameters in Indian Mustard. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 4956–4965.

- Gaspar, A.; Garrido, E.M.; Rio Esteves, M.; Quezada, E.; Milhazes, N.; Garrido, J.; Borges, F. New Insights into the Antioxidant Activity of Hydroxycinnamic Acids: Synthesis and Physicochemical Characterization of Novel Halogenated Derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 44, 2092–2099. [CrossRef]

- Teh, S. S.; Birch, E.J. Effect of Ultrasonic Treatment on the Polyphenol Content and Antioxidant Capacity of Extract from Defatted Hemp, Flax and Canola Seed Cakes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014, 21, 346–353. [CrossRef]

- Mladěnka, P.; MacÁková, K.; Filipský, T.; Zatloukalová, L.; Jahodář, L.; Bovicelli, P.; Silvestri, I.P.; Hrdina, R.; Saso, L. In Vitro Analysis of Iron Chelating Activity of Flavonoids. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2011, 105, 693–701. [CrossRef]

- Dudonné, S.; Vitrac, X.; Coutiére, P.; Woillez, M.; Mérillon, J.M. Comparative Study of Antioxidant Properties and Total Phenolic Content of 30 Plant Extracts of Industrial Interest Using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD, and ORAC Assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 1768–1774. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Saura-Calixto, F. Effect of Solvent and Certain Food Constituents on Different Antioxidant Capacity Assays. Food Res. Int. 2006, 39, 791–800. [CrossRef]

| TPC | FRAP | TFC | DPPH | MIC | ABTS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPC | 1 | |||||

| FRAP | .936** | 1 | ||||

| TFC | .863** | .940** | 1 | |||

| DPPH | .234 | .348** | .375** | 1 | ||

| MIC | .911** | .921** | .939** | .359* | 1 | |

| ABTS | .541** | .530** | .464** | .013 | .453** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).