Submitted:

30 January 2023

Posted:

01 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Background and Brief Literature Review on Similar Studies

2.2. Market Segments According to the Characteristics of Improved Forages

| Characteristics | Mulato II | Cayman | Camello | Cobra | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main features | Good response to drought, acid soils, and high temperatures Combines the best features of other hybrids |

Tolerant to humidity and waterlogging | Drought tolerance, quick establishment, good for acid soils | High yield, vertical growth that facilitates cutting | |

| Resistance to pests and diseases | spittlebug | spittlebug | spittlebug | spittlebug | |

| Required soil fertility level |

medium, high | humidity | medium | high (for higher yields) |

|

| Palatability | very good | very good | very good | very good | |

| CP (%) | 14-22 | 10-17 | 14-16 | 14-16 | |

| IVDMD (%) | 55-66 | 58-70 | 62 | 69 | |

| Yield (t/ha/cut) | 25 | <24 | 27-30 | 35-40 | |

| Main use | grazing | grazing | grazing | cut-and-carry | |

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Method for the Estimation of Potential Markets and Market Values

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Haan, C. A World Bank Study. Prospects for livestock- based livelihoods in Africa’s drylands; Washington, DC, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Felis, A. El papel multidimensional de la ganadería en África. Revista de Economía Información Comercial Española (ICE) 2020, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González C, Schiek B, Mwendia S, et al. Improved forages and milk production in East Africa. A case study in the series: Economic foresight for understanding the role of investments in agricultura for the global food system. CIAT.

- Ohmstedt U, Notenbaert A, Peters M, et al. Scaling of feeds and forages technologies in East Africa, Abstract. Tropentag, 18-20 September 2019. Available online: www.tropicalforages.info (accessed on 04 October 2022).

- World Food Programme de las Naciones Unidas. Regional food security and nutrition update Eastern Africa region 2022; Second quarter; October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Creemers J, Maina D, Opinya F, et al. Forage value chain analysis for the counties of Taita Taveta, Kajiado and Narok. Integrated & Climate Smart Innovations for Agro-Pastoralist Economies and Landscapes Kenya’s ASAL (ICSIAPL), SNV and KARLO 2021, 1–43.

- FAO. Plant Breeding Impacts and Current Challenges.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Paul BK, Groot JC, Maass BL, et al. Improved feeding and forages at a crossroads: Farming systems approaches for sustainable livestock development in East Africa. Outlook Agric 2020, 49, 13–20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT. Fitomejoramiento de forrajes: Contribuyendo la sostenibilidad de los pequeños productores en los trópicos; Cali, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- CGIAR Initiative Proposal: Market Intelligence and Product Profiling. Available online: https://www.cgiar.org/initiative/05-market-intelligence-for-more-equitable-and-impactful-genetic-innovation/ (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- EiB Excellence in Breeding Platform 2021, Annual report to the CGIAR.

- McHugh K, Morgan V, Ragot M, et al. Evaluation of CGIAR Excellence in Breeding Platform: Inception report. CAS Secretariat Evaluation Function.

- Fuglie KO, Adiyoga W, Asmunati R, et al. Farm demand for quality potato seed in Indonesia. Agricultural Economics 2006, 35, 257–266. [CrossRef]

- Marechera, G.; Ndwiga, J. Estimation of the potential adoption of Aflasafe among smallholder maize farmers in lower eastern Kenya. African Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 2015, 10, 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Dontsop Nguezet PM, Diagne A, Okoruwa OV, et al. Estimating the Actual and Potential Adoption Rates and Determinants of NERICA Rice Varieties in Nigeria. J Crop Improv 2013, 27, 561–585. [CrossRef]

- Mahoussi FE, Adegbola PY, Zannou A, et al. Adoption assessment of improved maize seed by farmers in Benin Republic. Journal of Agricultural and Crop Research 2017, 5, 32–41.

- Simtowe F, Marenya P, Amondo E, et al. Heterogeneous seed access and information exposure: implications for the adoption of drought-tolerant maize varieties in Uganda. Agricultural and Food Economics 2019, 7, 1–23.

- Ouédraogo M, Houessionon P, Zougmoré RB, et al. Uptake of Climate-Smart Agricultural Technologies and Practices: Actual and Potential Adoption Rates in the Climate-Smart Village Site of Mali. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1–19.

- Espinosa-García JA, Uresti-Gil J, Vélez-Izquierdo A, et al. Productividad y rentabilidad potencial del cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) en el trópico mexicano. Rev Mex De Cienc Agric 2015, 6, 1051–1063.

- Ramírez Gómez GA, Gutiérrez Castorena EV, Ortíz Solorio CA, et al. Predicción y diversificación de cultivos para Nuevo León, México. Rev Mex De Cienc Agric 2020, 11, 1017–1030.

- Donnet L, López D, Arista J, et al. El potencial de mercado de semillas mejoradas de maíz en México. Socioeconomía Documento de trabajo CIMMYT, Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo 2012, 8, 1–30.

- Enciso K, Triana N, Díaz M, et al. On (Dis)Connections and Transformations: The Role of the Agricultural Innovation System in the Adoption of Improved Forages in Colombia. Front Sustain Food Syst Epub ahead of print 11 January 2022. 5. [CrossRef]

- Ndah HT, Schuler J, Nkwain VN, et al. Determinants for Smallholder Farmers’ Adoption of Improved Forages in Dairy Production Systems: The Case of Tanga Region, Tanzania. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1–13.

- Ndah HT, Schuler J, Nkwain VN, et al. Factors Affecting the Adoption of Forage Technologies in Smallholder Dairy Production Systems in Lushoto, Tanzania. CIAT Working Paper 2017, 1–38.

- Gebremedhin, B.; Ahmed, M.M.; Ehui, S.K. Determinants of adoption of improved forage technologies in crop–livestock mixed systems: evidence from the highlands of Ethiopia. Tropical Grasslands 2003, 37, 262–273. [Google Scholar]

- Ayele S, Duncan A, Larbi A, et al. Enhancing innovation in livestock value chains through networks: Lessons from fodder innovation case studies in developing countries. Sci Public Policy 2012, 39, 333–346. [CrossRef]

- Njarui DM, Gatheru M, Gichangi EM, et al. Determinants of forage adoption and production niches among smallholder farmers in Kenya. Afr J Range Forage Sci 2017, 34, 157–166.

- oth GG, Nair PKR, Duffy CP, et al. Constraints to the adoption of fodder tree technology in Malawi. Sustainability Science for Meeting Africa’s Challenges 2017, 12, 641–656.

- Wambugu, C.; Place, F.; Franzel, S. Research, development and scaling-up the adoption of fodder shrub innovations in East Africa. Int J Agric Sustain 2011, 9, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, B.K.; Jacobs, S.W.L. Megathyrsus, a new generic name for Panicum subgenus Megathyrsus. Austrobaileya 2003, 6, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soreng RJ, Davidse G, Peterson PM, et al. In Internet Catalogue of World Grass Genera: On-line updates, corrections, and synonymy; Missouri Botanical Garden: St Louis.

- Enciso K, Díaz M, Triana N, et al. Limitantes y oportunidades del proceso de adopción y difusión de tecnologías forrajeras en Colombia. Alliance of Bioversity and CIAT 2020, 1–56.

- Enciso K, Triana N, Díaz M, et al. On (Dis)Connections and transformations: the role of the agricultural innovation system in the adoption of improved forages in Colombia. Front Sustain Food Syst Epub ahead of print 11 January 2022. 5. [CrossRef]

- Pizarro EA, Hare MD, Mutimura M, et al. Brachiaria hybrids: potential, forage use and seed yield. Tropical Grasslands - Forrajes Tropicales 2013, 1, 31–35. [CrossRef]

- Papalotla. Pastos Híbridos. Available online: http://grupopapalotla.com/pastos-hibridos.html (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Wrigley C, Corke H, Walker CE. Encyclopedia of grain science, 1st ed.; Elsevier Ltd, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cook B, Pengelly B, Schultze-Kraft R, et al. Tropical Forages: An interactive selection tool. International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), Cali, Colombia and International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Nairobi, Kenya.

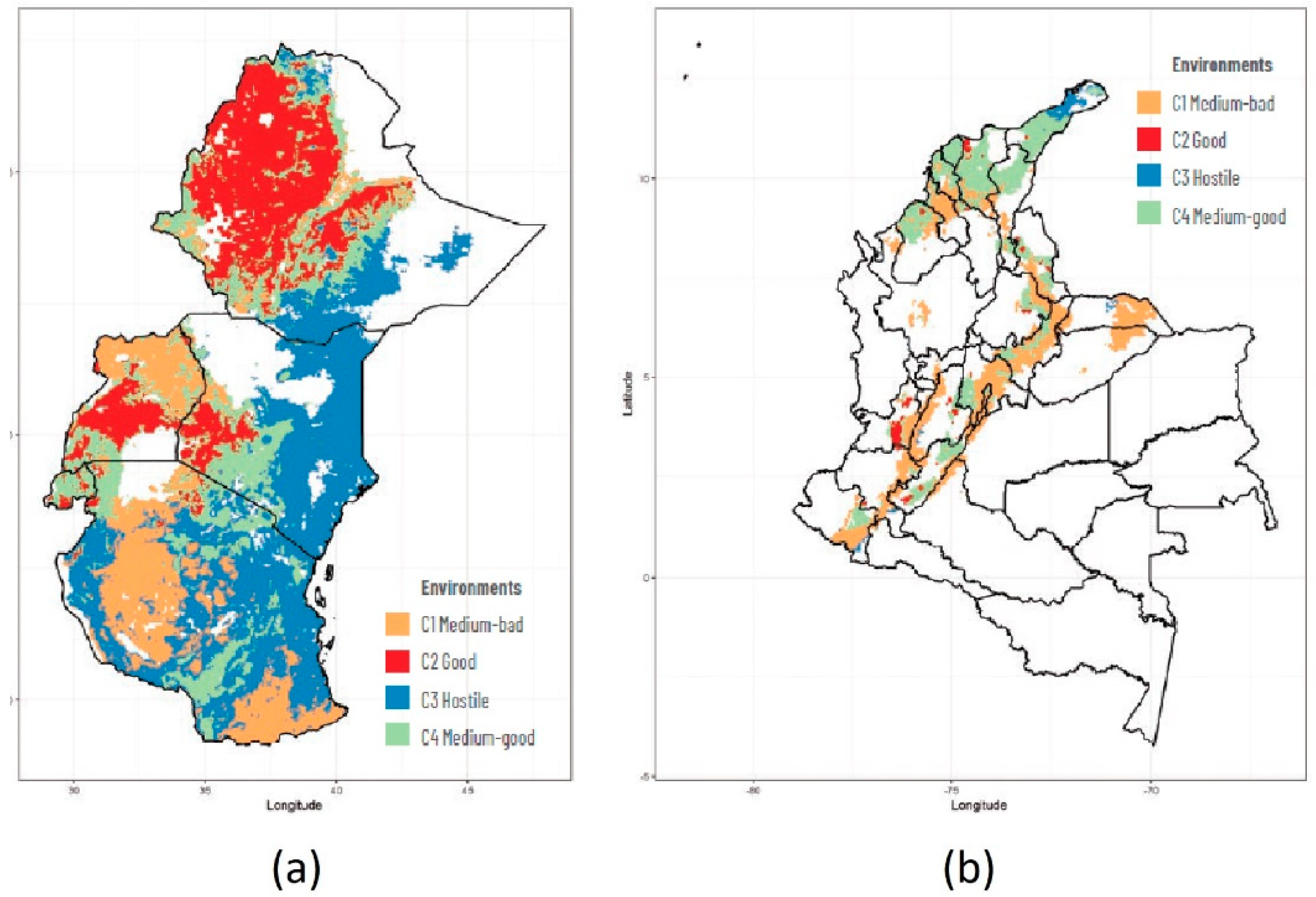

- 38. Oliphant H, Mora B, Ramírez-Villegas J, et al. Determining ideal sites for a pilot experiment in Colombia to trial new forages in East Africa. In International Forage & Turf Breeding Conference.

- African Group of Negotiators Experts Support AGNES. Desertification and climate change in Africa. Policy Brief.

- Rosegrant MW, Koo J, Cenacchi N; et al. Food security in a world of natural resource scarcity. The role of agricultural technologies, 1st ed.; Princeton Editorial Associates Inc.: Scottsdale, Arizona, 2014; Epub ahead of print 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Investigación Agropecuaria, I.N.I.A. Algunos conceptos sobre calidad de forrajes. Ficha Técnica. INIA Uruguay 2018, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, R.S.; Wawrzkiewicz, M.; Jaurena, G. Intercomparación de resultados de digestibilidad in vitro obtenidos por diferentes técnicas. Revista Argentina de Producción Animal (Suplemento 1) 2014, 34, 379. [Google Scholar]

- Navas, A. Importancia de los sistemas silvopastoriles en la reducción del estrés calórico en sistemas de producción ganadera tropical. Rev Med Vet (Bogota) 2010, 1, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heady, H.F. Palatability of herbage and animal preference. Journal of Range Management 1964, 17, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez E, Latorre M, Bonilla X, et al. Diversity of Rhizoctonia spp. Causing Foliar Blight on Brachiaria in Colombia and Evaluation of Brachiaria Genotypes for Foliar Blight Resistance. Plant Dis 2013, 97, 772–779. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwendia S, Nzogela B, Odhiambo R, et al. Important biotic challenges for forage development in East Africa. International Center for Tropical Agriculture CIAT, Nairobi, Kenya 2019, 1–10.

- Díaz I, Gutiérrez G. El agroecosistema del Secano Interior. In: Díaz I (ed); Producción vitivinícola en el secano de Chile central; Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias, 2020; Boletín INIA N°418,: Chile; 128 p.

- Pasturas Tropicales. Pasto Cayman. Available online: https://pasturastropicales.com/pasto-cayman-en-colombia/ (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Peters M, Franco LH, Schmidt A, et al. Especies forrajeras multipropósito. Opciones para productores del trópico americano. In Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT); Bundesministerium für Wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (BMZ); Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) Publicación CIAT; 2010; pp. 1–212.

- TropicalSeeds. Cayman. 14 September. Available online: https://www.tropseeds.com/cayman/#:~:text=CAYMAN%C2%AE%20Brachiaria%20Hybrid%20CV%20grass.&text=It%20is%20a%20noble%20and,improve%20milk%20and%20meat%20production.P (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Nuñez, J. Potencial de la inhibición biológica de la nitrificación (IBN) en forrajes tropicales; Universidad Nacional de Colombia Palmira, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Saenzfety. Panicum Maximum Massai incrustada. Available online: https://saenzfety.com/producto/panicum-maximum-massai-incrustada/ (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Leguminutre. Hibrido Mavuno. Available online: http://leguminutre.com/mavuno.htm (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Agrizon. Semilla de Pastos Brachiaria Híbrida Mavuno 5 kg. Available online: https://www.e-agrizon.com/producto/brachiaria-hibrida-mavuno-5-kg/ (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. In FAOSTAT statistical database.

- Ramankutty N, Evan AT, Monfreda C, et al. Farming the planet: 1. Geographic distribution of global agricultural lands in the year 2000. Global Biogeochem Cycles 2008, 22, 1–19.

- Hengl T, Mendes J, MacMillan RA, et al. SoilGrids1km — Global soil information based on automated mapping. PLoS One 2014, 9, 1–17.

- Ruane, A.C.; Goldberg, R.; Chryssanthacopoulos, J. Climate forcing datasets for agricultural modeling: merged products for gap-filling and historical climate series estimation. Agric For Meteorol 2015, 200, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk C, Peterson P, Landsfeld M, et al. The climate hazards infrared precipitation with stations—a new environmental record for monitoring extremes. Sci Data 2015, 2.

- DANE. METODOLOGÍA GENERAL ÍNDICE DE PRECIOS AL CONSUMIDOR – IPC. In Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística. Dirección de Metodología y Producción Estadística / DIMPE.

- Gallo, I.; Enciso, K.; Burkart, S. The Latin American Forage Seed Market: Recent Developments and Future Opportunities. (Reporte inédito). In International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT).

- Mordor Intelliegence. Mercado de semillas de forraje: crecimiento, tendencias, impacto de Covid-19 y pronósticos (2022 - 2027). Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/es/industry-reports/forage-seed-market.

- Editora Gazeta. Anuário Brasileiro de Sementes 2019; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fuglie, K.; Peters, M.; Burkart, S. The Extent and Economic Significance of Cultivated Forage Crops in Developing Countries. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.E. El Proceso de Liberación de Nuevos Cultivares de Forrajeras: Experiencias y Perspectivas. In: Ferguson JE (Ed). Semilla de Especies Forrajeras Tropicales Conceptos, casos y enfoque de la investigación y la producción. Cali: Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT), 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Marra, M.; Pannell, D.J.; Abadi Ghadim, A. The economics of risk, uncertainty and learning in the adoption of new agricultural technologies: where are we on the learning curve? Agric. Syst. 2003, 75, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Winsen F, de Mey Y, Lauwers L, et al. Determinants of risk behaviour: effects of perceived risks and risk attitude on farmer's adoption of risk management strategies. J. Risk Res. 2014, 19, 56–78.

- Trujillo-Barrera, A.; Pennings, J.M.E.; Hofenk, D. Understanding producers' motives for adopting sustainable practices: the role of expected rewards, risk perception and risk tolerance. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2016, 43, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIAT Tropical Grasses and Legumes: Optimizing Genetic Diversity for Multipurpose Use (Project IP5). Annual Report 2004; Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical: Cali, 2004.

- Wünscher T, Schultze-Kraft R, Peters M, et al. Early adoption of the tropical forage legume Arachis Pintoi in Huetar norte, Costa Rica. Exp. Agric. 2004, 40, 257–268. [CrossRef]

- Lascano, C.E.; Peters, M.; Holmann, F. Arachis pintoi in the humid tropics of Colombia: a forage legume success story. Trop. Grasslands 2005, 39, 220. [Google Scholar]

- Kaimowitz, D.; Angelsen, A. Will livestock intensification help save Latin America's tropical forests? J. Sustain. Forestry 2008, 27, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapar, M.A.; Ehui, S.K. Factors affecting adoption of dual-purpose forages in the Philippine uplands. Agric. Syst. 2004, 81, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turinawe, A.; Mugisha, J.; Kabirizibi, J. Socio-economic evaluation of improved forage technologies in smallholder dairy cattle farming systems in Uganda. J. Agric. Sci. Arch. 2012, 4, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labarta R, Martinez JM, Yaccelga A, et al. Assessing the Adoption and Economic & Environmental Impacts of Brachiaria Grass Forage Cultivars in Latin America Focusing in the Experience of Colombia SPIA Technical Report; Standing Panel for Impact Assessment (SPIA): Rome, Italy, 2017.

- Charry A, Narjes M, Enciso K, et al. Sustainable intensification of beef production in Colombia—chances for product differentiation and price premiums. Agric. Food Econ. 2019, 7, 22. [CrossRef]

- ravo A, Enciso K, Hurtado JJ, et al. Estrategia sectorial de la cadena de ganadería doble propósito en Guaviare, con enfoque agroambiental y cero deforestación. Publicación CIAT No. 453; Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT): Cali, Colombia, 2018.

- Charry A, Jäger M, Enciso K, et al. Cadenas de valor con enfoque ambiental y cero deforestación en la Amazonía colombiana – Oportunidades y retos para el mejoramiento sostenible de la competitividad regional. CIAT Políticas en Síntesis No. 41; Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT): Cali, Colombia, 2018; 10p.

- Enciso K, Bravo A, Charry A, et al. Estrategia sectorial de la cadena de ganadería doble propósito en Caquetá, con enfoque agroambiental y cero deforestación. Publicación CIAT No. 454; Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT): Cali, Colombia, 2018.

- Enciso K, Triana N, Díaz M, et al. On (Dis)Connections and Transformations: The Role of the Agricultural Innovation System in the Adoption of Improved Forages in Colombia. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 5.

- Dill MD, Emvalomatis G, Saatkamp H, et al. Factors Affecting Adoption of Economic Management Practices in Beef Cattle Production in Rio Grande Do Sul State, Brazil. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 42, 21–28. [CrossRef]

- Spielman D, Davis KE, Negash M, et al. Rural innovation systems and networks: Findings from a study of Ethiopian smallholders. Agric. Hum. Values 2011, 28, 195–212. [CrossRef]

- Kebebe, E. Bridging technology adoption gaps in livestock sector in Ethiopia: an innovation system perspective. Technol. Soc. 2018, 57, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulu, M.; Notenbaert, A. Adoption of Improved Forages in Western Kenya: Key Underlying Factors. 46 slides. 2020.

- Jones AK, Jones DL, Edwards-Jones G, et al. Informing decision making in agricultural greenhouse gas mitigation policy: a Best-Worst Scaling survey of expert and farmer opinion in the sheep industry. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 29, 46–56. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, C.G.; Dorward, P.; Rehman, T. Factors influencing adoption of improved grassland management by small-scale dairy farmers in central Mexico and the implications for future research on smallholder adoption in developing countries. Livestock Sci. 2013, 152, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi Borges, J.A.; Oude Lansink, A.G.J.M. Identifying psychological factors that determine cattle farmers' intention to use improved natural grassland. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosius FHW, Hofstede GJ, Bokkers EAM, et al. The social influence of investment decisions: a game about the Dutch pork sector. Livestock Sci. 2019, 220, 111–122. [CrossRef]

- Hidano, A.; Gates, M.C.; Enticott, G. Farmers' decision making on livestock trading practices: cowshed culture and behavioral triggers amongst New Zealand Dairy Farmers. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 7, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White D, Holmann F, Fujisaki S; et al. Will intensifying pasture management in Latin America protect forests - Or is it the other way around? In Agricultural Technologies and Tropical Deforestation; Angelsen A, Kaimowitz D (eds), Ed.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, 2001; pp. 91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Cadavid JV, Rincón A, et al. Land speculation and intensification at the Frontier: a seeming paradox in the Colombian Savanna. Agric. Syst. 1997, 54, 501–520. [CrossRef]

- Moreno Lerma, L.; Díaz Baca, M.F.; Burkart, S. Public Policies for the Development of a Sustainable Cattle Sector in Colombia, Argentina, and Costa Rica: A Comparative Analysis (2010–2020). Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Birner, R.; Resnick, D. The political economy of policies for smallholder agriculture. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1442–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schut M, van Asten P, Okafor C, et al. Sustainable intensification of agricultural systems in the Central African Highlands: the need for institutional innovation. Agric. Syst. 2016, 145, 165–176. [CrossRef]

- ISPC Tropical Forages and the Diffusion of Brachiaria Cultivars in Latin America; CGIAR Independent Science and Partnership Council: Rome, 2018.

| Characteristics | Mombasa | Tanzania | Massai | Mavuno* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main features | High regrowth rate and good stem-leaf-ratio Medium tolerance to cold and burning Good drought tolerance |

Medium drought tolerance | Burn and shade tolerance Reduced yield by 50% in dry season |

Good tolerance to drought, burning, and shade Medium tolerance to humidity |

||

| Resistance to pests and diseases | spittlebug | spittlebug medium tolerance to coal in the inflorescences |

spittlebug sensitive to panicle rot caused by T. ayresii (<80% of inflorescences) |

spittlebug | ||

| Required soil fertility level |

medium to high acid soils |

medium to high acid soils |

low to medium acid soils |

medium acid soils |

||

| Palatability | very good | good | good | very good | ||

| CP (%) | 10-14 | 10-12 | 7-11 | 18-21 | ||

| IVDMD (%) | 60-65 | 62 | 55-60 | 60 | ||

| Yield (t/ha/cut) | 25 | 18-20 | 21 | 17-20 | ||

| Main use | grazing cut-and-carry |

grazing cut-and-carry |

grazing cut-and-carry |

grazing cut-and-carry |

||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).