1. Introduction

Camera fingerprint is based in the unavoidable imperfections present on electronic imaging sensors due to their manufacturing. These imperfections derive on a multiplicative noise that can be modeled in this equation [

1,

2,

3]:

where Im

in is the “true” image presented to the camera (the incident light intensity), I

ones is a matrix of ones, Noise

cam is the “sensor noise”, “.” is matrix point by point product and Noise

add is additive noise from other sources.

This kind of noise is due to small differences in light sensitivity between different pixels. As stated before, this phenomenon is present in all sensors. Noise pattern (Noisecam) is not altered during sensor life and it is different between different chips, even between those manufactured in the same series. Thus Noisecam can be used as a sensor fingerprint.

SCI (Source Camera Identification) methods are based on somehow estimating Noisecam and comparing results from different images.

An attacking method would be any processing over Imout that “to some extent” accomplishes the following two purposes:

Similarly to the importance of cryptanalysis to cybersecurity world, study on camera fingerprint attacks is important to image forensics because it is the only way to demonstrate robustness of proposed extraction and comparison methods.

PRNU stands for Photo-Response Non-Uniformity and it is used to refer to sensor noise as modeled by equation 1. PRNU estimation has become the “de-facto” standard for camera fingerprint. In [

4], an extensive list of methods is compared and PRNU is acknowledged as the most used method and the one most present on literature.

There exists literacy about “counter-forensic” measures. For example, in [

5], M. Goljan et al study methods for defending against attacks on PRNU. In this publication, authors center themselves on detecting forging attacks (plating a false PRNU on an image), not erasing or randomly altering the PRNU. In [

6], L.J. García-Villalba describes an anti-forensic method. Method is based on Wavelet Transform exactly like one of the several methods that are tested here. Authors of [

6] do not perform a thorough test of a significant pool of methods like it is done in this paper. In [

7], there exists an open-source project (PRNU Decompare) about a software capable of deleting or even “forging” a PRNU pattern. Nevertheless, we found no associated paper or report, neither detailed data about systematic tests.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PRNU or “Camera Fingerprint”

As stated before, PRNU will be the feature extracted from images to accomplish SCI (Source Camera Identification), id EST: it will be treated as the “fingerprint” of a camera sensor.

PRNU estimation is always based on some kind of image denoising filter to estimate Imin in equation 1. Having a set of images (known to be captured by the same camera), a PRNU pattern can be estimated and then compared to any image from an unknown camera. Comparison must yield a high positive value if patterns are similar, meaning that it is probable that source camera is the same. Nowadays, despite of recent advances in this field, it is very difficult to come to a legally irrefutable result.

The denoising process used to compute PRNU can be of very different types, for example:

Simply a 3x3 median filter like in [

8].

The well-known Wiener filter [

9].

Modifications of Wiener filter, for example in [

10] (implementation chosen as basis [

10,

11]), they use an implementation on the WVT (Wavelet Transform [

12]). This means using the Wiener formula (

) in the WVT transform, where white noise (constant in the WVT) is assumed.

With any of the previous denoising techniques, a residual

W is computed as:

Assuming that

W is equal to the product: Noise

camIm

in (neglecting the additive noise, Noise

add) and assuming also that that Im

in=denoise(Im); the pattern (or fingerprint) is computed as the weighted average (having N images available for PRNU computation):

Last but not least, it is important to use a good comparison method to detect similarities between the different extracted patterns. Following [

10,

11], the best election is PCE (Peak to Correlation Energy,). PCE has demonstrated good performance in PRNU comparison [

13].

PCE is obtained from the complete cross correlation between two signals (having into account all possible delays). Maximum of correlation energy (squared value) is divided by the mean energy of the whole correlation EXCLUDING peak value and also peak surroundings.

2.2. Attacking Methods

Let’s first, establish a classification on methods and then, we will comment the different methods that have been included in the next section. Method categories could be summarized as follows:

Noise addition (or modification): randomizing least significant components (bits) does not add or reduce noise but it merely modifies it. Nevertheless, it is the first idea that comes up, fingerprints are based on noise and modifying noise might work.

Geometric distortion: geometric distortions like pixel position scrambling and/or rotating and de-rotating image (with a slight angle error) have had success against other “noise like” patterns like watermarks.

Noise reduction: if image noise is reduced, the fingerprint will also be erased (at least to some extent).

Combined methods: methods constructed cascading two or more of the previous ones (may be from the same category or not).

2.2.1. Noise Addition (or modification)

Two flavors of this idea have been implemented. First, modifying the

n least significant bits in the image (pixel) domain; second, adding noise on the “Discrete Cosine Transform” (DCT) coefficients. In the second case, Watson matrix from JPEG standard [

14] is used to determine the allowed noise quantity. Noise is a uniform random variable with different interval on each DCT position.

2.2.2. Geometric Distortions

Three different methods from this idea have been implemented:

Scrambling pixels: moving them to a nearby, random position (a maximum radius, r, is defined to maintain the process controlled). Gaussian distribution is used to scramble pixels.

Rotating and de-rotating: image is rotated a significant angle (say α=15º). Pixel “bicubic” interpolation is forced. Then image is “de-rotated” (rotated again an angle of –α+β, where β is a small error, say 0.50º). Bicubic interpolation is forced again. This operation produces some artifacts on image corners that can be avoided by simple techniques that will become part of processing

Scaling and de-scaling: image is up-scaled by a significant factor (say

sf=3). “Lanczos3” interpolation [

15] is forced. Then the first line and the first column are erased. Image is downscaled to its original size, forcing a “non-uniform sampling” and using “Lanczos2” interpolation.

2.2.3. Noise Reduction

Two methods for this have been implemented. First, it is the standard Wiener filter. Second, it is a Wiener implementation in the wavelet transform domain inspired in the PRNU extraction method [

10].

2.2.4. Combined Methods

As it is easily deduced, combined methods are those constructed cascading two or more of the previously described methods. The following combinations have been implemented (they were inspired by our first tests on individual methods trying to combine the strengths of each):

Combination of simple noise addition and geometric techniques. No Wiener or other noise reduction (n=3, r=2, α=10º, β=0.5º, sf=3).

Wiener filtering first, rotation and de-rotation (

α=10º,

β=0.5º), followed by a “deblurring” method for improving image quality, concretely: Lucy-Richardson deconvolution filter [

16].

2.3. Design of Tests

First tests were performed using images from “Dresden Image Database”, [

17]. In this case, not many images are provided for each device (camera/sensor). It is a total of 36 images from 6 different cameras (all photos being JPEG files generated by each device with NO processing). Results are not very significant with this small sample but this was useful to get insight into the issue.

Secondly, VISION dataset [

18] was used. In this case, 6 different devices are again selected, but number of images is much greater with a total of 2057 images from all cameras and 281 images in the less represented one.

As there are different image resolutions, images were preprocessed simply cropping a centered sub-image of fixed square size: 2048x2048 for the Dresden Images and 1024x1024 for the VISION dataset. Images from the VISION dataset are entirely taken by smartphones. Results in the next section will always be from this dataset as it is the most representative one and also because focusing on smartphones is important as they are nowadays the most used image capturing devices.

A detail of some importance is that images may have been taken with a 90º rotated sensor (vertical format: height greater than width), in this case preprocessing includes rotating them back -90º so that images are always in horizontal format. Besides of testing PRNU algorithms robustness, these tests also detect which kind of cameras are better (or worse) for fingerprint detection. “Dresden Image Database” is made of images from commercial “compact” cameras (not smartphones) and despite the smaller database size, we can infer a result comparing both datasets: source camera identification is more effective (less error rate) in the case of smartphones. An explanation is possible: in general, commercial cameras use sensors of higher quality that have smaller amounts of PRNU noise.

Attacking algorithms were implemented in MATLAB [

19]. Tools were designed to perform tests that work on the condition that images from each camera are saved in a separate directory. Therefore, adding a new camera to the test is very easy.

For each camera the first

nt images (

nt=20 for VISION database,

nt=3 for Dresden database) are used to create a PRNU pattern using tools in [

11]. After that:

A confusion matrix for all cameras is computed (understood as the truth table resulting from trying to identify the source camera for all images that are NOT used in computing the PRNU). This allows us measuring the “camera identification error rate” before any attack is applied.

Each of the attacks defined in

section 2.2 is applied re-computing the confusion matrix and error rate.

SNR (Signal to Noise Ratio) after the attack (considering original and attacked, or noisy, images) is also computed as a means for considering image quality degradation. In the next section, average SNR for each method or “attack” is presented, “visual” quality of processed images is also checked via human volunteers.

With this experiment, table of

section 3 is created, which is used to draw conclusions on PRNU performance and to assess best attacking methods.

3. Results

First tests were done using the “Dresden Image Database” [

15], selecting images from six cameras: Canon Ixus 70 (2 cameras of this model), Casio Ex150 (also two instances) and Kodak M1063 (two instances). Secondly a more thorough test was done with VISION dataset [

18], selecting again six devices (smartphones): “Samsung Galaxy Mini”, “Apple iPhone 4s”, “Apple iPhone 5c”, “Apple iPhone 6”, “Huawei P9” and “LG D290” but, now, with a much greater number of images.

With no attack, error rate was 25% for the Dresden dataset and 9% for VISION dataset, confirming the fact that SCI is easier for smartphones.

Error rates and other data are, from now on, always from the VISION dataset. Being this one the most significative.

All the attacks make these rates go higher. Note that with six cameras, a “random identification” algorithm should yield a 16.67% correct identification rate (83.33% error rate). This means that an attack able to produce an error rate greater than this value is a “fully successful” attack.

Error rate is measured twice for each method. First, the training (computation of PRNU) is done with original (non-attacked) images. Secondly, training is performed with attacked images. Notice that forensic people can have access to the suspicious camera or not. Sometimes [

3], PRNU is used for clustering: trying to find out if some images come from the same camera (with no access to it). In our tests, error rate is always computed with images different from training ones.

Tests results are summarized in

Table 1 (next page) where each method is assigned a “Key Letter” (in alphabetical order, first method is called

A). See that there are two columns about image quality. This is important because an attack is not “useful” if it is very “noticeable” (if image quality is severely damaged). Final image quality is assessed in two ways: subjective and objective (SNR computation). See that for some attacks (for example rotating or scrambling), subjective quality can be high but SNR gets low because pixels are moved and SNR is computed comparing pixels at the same position. Subjective quality has been checked with opinions of seven human volunteers. Here it is stated the most repeated opinion plus some remarkable comments (if any).

See that, generally speaking, attack success (error rate) is higher when training is done with “non-attacked” images. Perhaps, this is because when PRNU is computed after “being altered by an attack”, it will contain these alterations and it will be more difficult to be obfuscated. For example, with the rotating method (method D), the error rate goes down from 78% to 10% when training with attacked (obfuscated) images. Probably, detected noise pattern is rotated by the attack and PRNU robustness is much higher if it can train with “rotated” noise. It is remarkable to acknowledge that PRNU is more resilient that it could seem from a first point of view (PRNU is noise and any decision based on noise seems prone to frequent errors). See that no method is able to reach the “full success” ratio of 83.33%. It is true that some of the methods are able to come very close when training is done with original images. Rates marked in bold are considered “successful attacks” as they reduce very significantly the reliability of SCI.

In

Table 1, there is a column with mean execution time for each attack. See that MATLAB implementation is not efficient. Besides a fast attack implementation is not the main purpose of this work but the possibility and effectiveness of attacks. Tests were run in an Intel I5-4590S CPU (3.00 GHz), 16.00 Gb RAM.

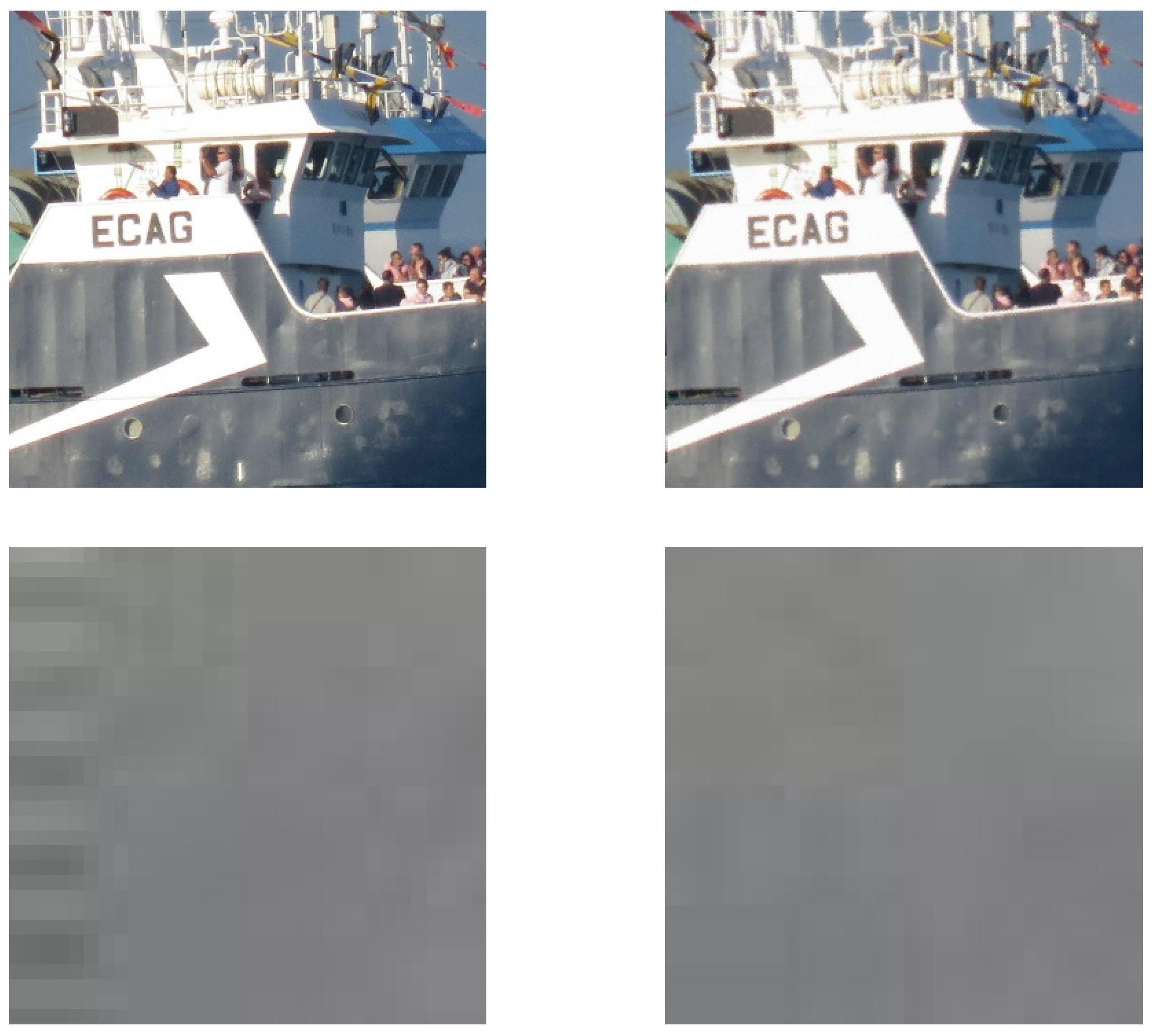

In

Figure 1, a graphic example is shown. The original image (top-left) is from a Canon Powershot camera (not from any of the datasets). This image is processed (attacked) with method

I: Wiener filtering cascaded with rotation and a de-blurring filter (one of the more successful ones). Then, PRNU patterns from both images are computed. Notice than in ordinary tests, more than one image is used to get the PRNU pattern and, then, this pattern is correlated to those extracted from input images for trying to guess the source camera. In this figure, the change between extracted patterns is the more important issue. This kind of patterns is not very visual to be shown because they are merely amplified noise. They consist on real valued matrixes of the same size of original image with values from -16 to 16. In this case, a truncated version of matrix absolute value is represented. Interpretation is simply that brighter points are pixels where it is possible to extract a significant value for PRNU. See that for the original image, algorithm fails to compute pattern only in some white (perhaps over-exposed) pixels. For the processed image, computing PRNU pattern becomes much more difficult.

4. Discussion

4.1. Genral Conclusions and Future Lines

Robustness of the nowadays most used method for camera fingerprint identification (PRNU) is thoroughly tested and conclusion is that it has strong resilience against simple attacks like those based on geometric operations and/or based on altering noise. More elaborated methods based on noise theory like Wiener filtering have also been tested creating better (but still not definite) attacks. Best attacks in our study are created combining pairs of better single methods tested previously.

As a general conclusion, PRNU initial effectiveness and resilience is greater in cameras (Dresden Database) than in Smartphones (VISION dataset). Greater image sensor quality means worse effectiveness of SCI (Source Camera Identification).

Among the results of this work, the following are remarkable: the development of a systematic procedure to test SCI methods, a very thorough testing of PRNU with more than 2000 test images and besides the finding of some very effective attacks on PRNU based SCI.

4.2. Selecting a Method

Seeing the two last columns of

Table 1, it can be concluded that methods that include rotation are the better for obfuscating PRNU.

It is also concluded that obfuscation is much more for effective on forensic systems that have been trained with “non-fooled” images. Training with obfuscated images gets always smaller errors. For this reason, image clustering based on PRNU similarities can still be possible in the presence of simple fooling methods, nevertheless attribution of “fooled” images to a known camera (with physical access to it) is more difficult.

After test results, if we were prompted to select one, that one would be method H: combination of simple noise addition and geometric techniques. This is because it produces the biggest error with acceptable quality.

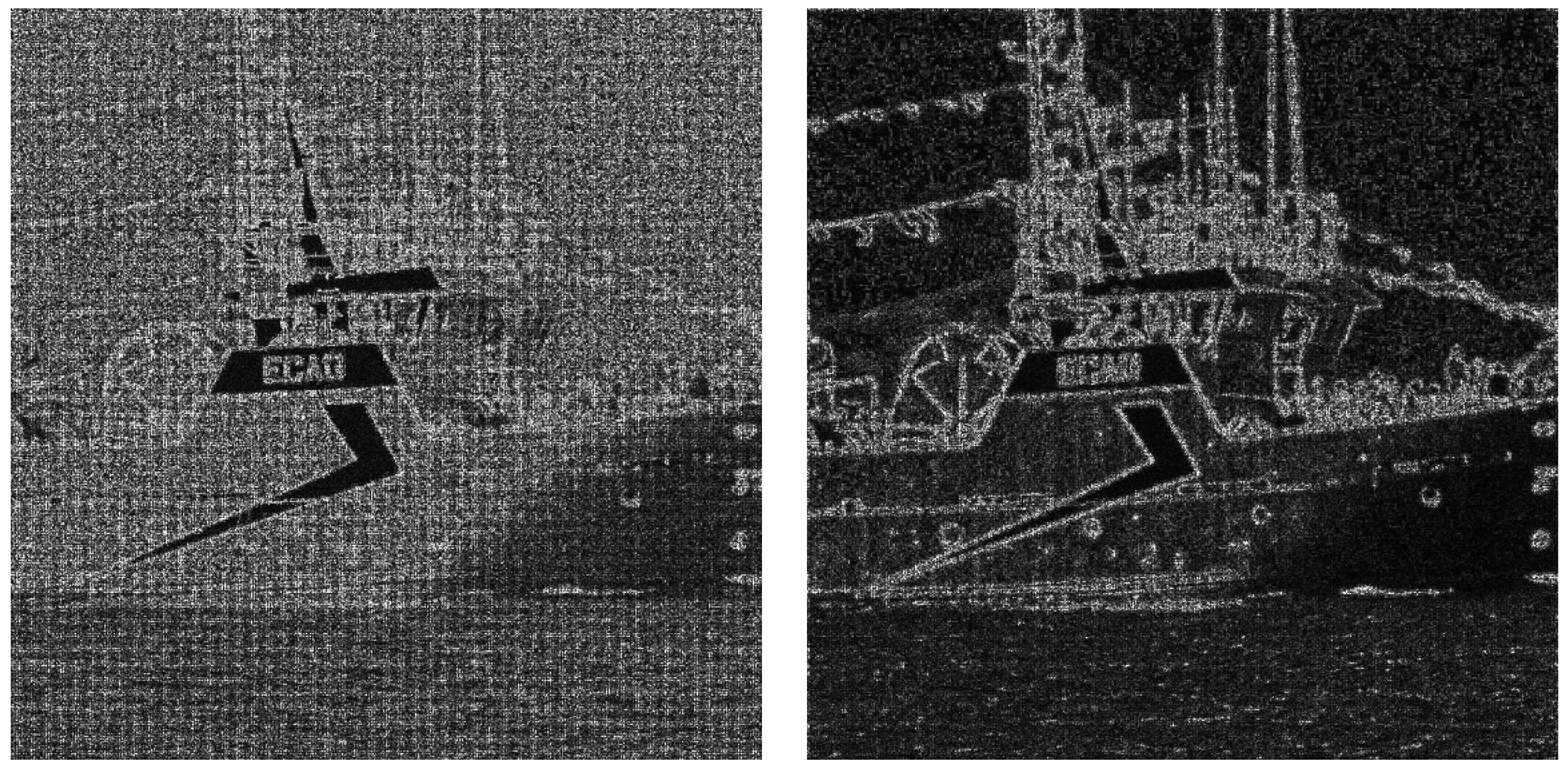

To illustrate a bit, an example of application of method

H is presented in

Figure 2. Here ROI is 1024x1024. Above, original (left) and obfuscated image (right) are presented. Regarding image quality, the only drawback in this method is the presence of some “artifacts” on image corners. See bottom-left corner of the attacked image magnified on the bottom-left image of

Figure 1. This is due to the (0.5º) error in de-rotation. There are some pixels that “are not defined” and that have been computed “extrapolating” with a linear “interpolation” filter yielding this result.

For this reason, a new (and simple) processing has been designed to avoid this problem. The method is simply:

The same corner from this new method is shown magnified in

Figure 2, bottom-right. Results for this new method don not differ largely from the original ones. Data in

Table 1 have already been obtained with the new artifact correction process applied on all methods that include rotation (

D,

H and

I).

Figure 2.

Above: image of

Figure 1 processed with method

H, below: corner details with different correction methods.

Figure 2.

Above: image of

Figure 1 processed with method

H, below: corner details with different correction methods.

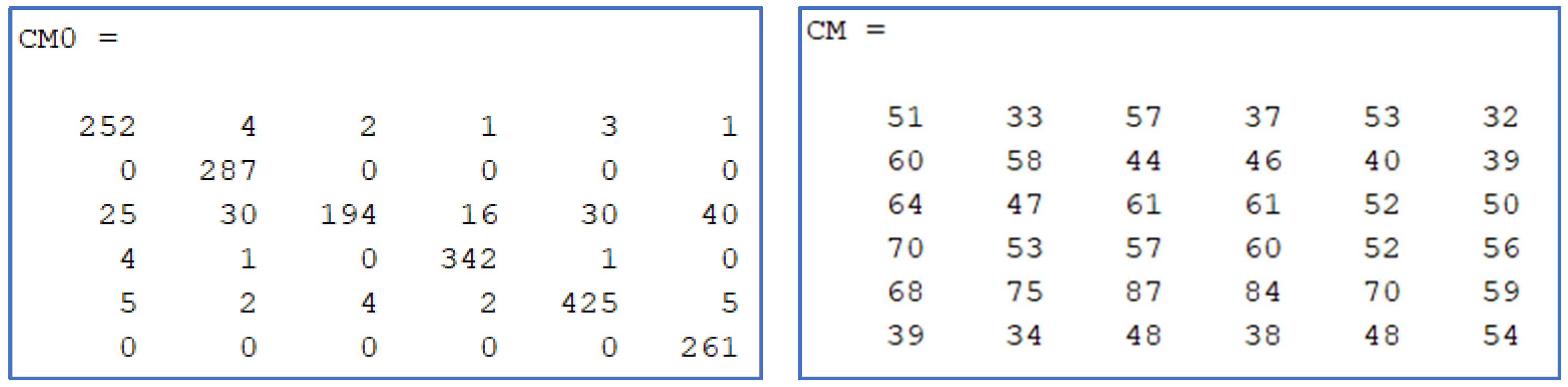

Figure 3.

Confusion matrix samples. Above: no attack. Below: preferred combined method (method H).

Figure 3.

Confusion matrix samples. Above: no attack. Below: preferred combined method (method H).

4.3. Future Lines

Future lines of research would be developing new methods and studying more deeply their interactions with fingerprint computation. This would also allow developing more robust fingerprint methods.

Author Contributions

Initial concept and software development: Fernando Martín-Rodríguez, New tests design, debugging, improvements: Fernando Isasi-de-Vicente and Mónica Fernández-Barciela. Writing and revising: Fernando Martín-Rodríguez, Fernando Isasi-de-Vicente and Mónica Fernández-Barciela.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All results come from using public image datbases: Dresden Image Database and Vision dataset.

Acknowledgments

authors wish to thank all personnel in AtlantTIC research center for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- M. Chen et al, “Determining image origin and integrity using sensor noise”, IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security (TIFS), 2008, vo. 3, no. 1, pp. 74-90. [CrossRef]

- A. Pedrouzo-Ulloa et al, “Camera attribution forensic analyzer in the encrypted domain”, in IEEE International Workshop on Information Forensics and Security (WIFS), IEEE (2018). [CrossRef]

- P.M. Pérez-Miguélez and F. Pérez-González, Study and implementation of PRNU-based image clustering algorithms, Master Thesis (University of Vigo, Spain), Vigo (2019).

- J. Bernacki, “A survey on digital camera identification methods”, Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation, 2020, vol. 34. [CrossRef]

- M. Goljan, J. Fridrich and M. Chen, “Defending Against Fingerprint-Copy Attack in Sensor-Based Camera Identification”, IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, 2011, vol. 6, no. 1, pp 227-236. [CrossRef]

- L.J. García-Villalba, A.L. Sandoval-Orozco, J. Rosales-Corripio, J. Hernández-Castro, “A PRNU-based counter-forensic method to manipulate smartphone image source identification techniques”, Future Generation Computer Systems, 2017, Vol 76, pp 418-427. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://sourceforge.net/projects/prnudecompare/ (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- G. J. Bloy, “Blind camera fingerprinting and image clustering”, IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (PAMI), 2008, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 532-534. [CrossRef]

- H. Ogawa and E. Oja, “Projection filter, Wiener filter, and Karhunen-Loève subspaces in digital image restoration”, Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications, 1986, vol. 114, no. 1, pp. 37-51. [CrossRef]

- M. Goljan, J. Fridrich and T. Filler, “Large Scale Test of Sensor Fingerprint Camera Identification”, Procceedings of SPIE, Electronic Imaging, Media Forensics and Security XI, 2009, vol. 7254, no. 0I, pp. 01-12. [CrossRef]

- Camera Fingerprint Homepage (from professor Goljan). Available online: http://dde.binghamton.edu/download/camera_fingerprint/ (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- C.K. Chui, An Introduction to Wavelets, Academic Press, San Diego (1992).

- B.V.K.V. Kumar and L.G. Hassebrook, “Performance measures for correlation filters”, Applied Optics, 1990, vol. 29, no. 20, pp. 2997-3006. [CrossRef]

- A.B. Watson, “DCT quantization matrices visually optimized for individual images”, Proceedings of SPIE, 1993, vol. 1913, no. 14, pp. 1-15. [CrossRef]

- P. Getreuer, “Linear Methods for Image Interpolation”, Image Processing On Line, 2011, vol. 1, pp. 238-259. [CrossRef]

- W.H. Richardson, “Bayesian-Based Iterative Method of Image Restoration”, Journal of the Optical Society of America, 1972, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 55-59. [CrossRef]

- T. Gloe, Rainer Böhme, “The ‘Dresden Image Database’ for Benchmarking Digital Image Forensics”, Proceedings of the 2010 ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, ACM (2010). [CrossRef]

- D. Shullani et al, “VISION: a video and image dataset for source identification”, Eurasip Journal on Information Security, 2017, Vol 15. [CrossRef]

- MATLAB. Available online: https://es.mathworks.com/products/matlab.html (accessed on 25 January 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).