Abbreviations: ALL- Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, DNA- Deoxyribonucleic acid, EcA – Escherichia coli asparaginase, ErA- Erwinia chrysanthemi asparaginase, PEG- polyethylene glycol, Asn-asparagine, MHCII- Major histocompatibility complex II, ASNase- asparaginase.

1. Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most frequent neoplasm in childhood, constituting 80% of all acute leukemias in the pediatric age group. This is a hematologic neoplasm, the lymphoblastic precursors of which proliferate rapidly and replace other hematopoietic cells. Hence, 25% and 19% of all tumors in children under 15 and 19 years of age, respectively, are ALL [1].

Among the drugs used for chemotherapeutic treatment of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is L-asparaginase (EC number 3.5.1.1), an enzyme that has successfully contributed to increased survival rates for this disease [2,3]. L -asparaginase is the first therapeutic enzyme with antineoplastic properties that has been extensively studied by researchers and scientists worldwide. The antitumor properties of L -asparaginase are due to its hydrolytic capacity. This enzyme belongs to the group of amidase enzymes and can decompose the amino acid L-asparagine into aspartate and ammonia and also presents glutaminase activity [4]. Asparagine is a non-essential amino acid necessary for protein synthesis and normal cell growth [5]. Although healthy cells can synthesize asparagine from aspartic acid through the enzyme asparagine synthetase, neoplastic cells depend on an exogenous supply of asparagine for their existence and reproduction, since they do not possess the intracellular capacity to synthesize enough asparagine [5,6]. Based on this, the use of L-asparaginase in chemotherapies was implemented and it has been demonstrated that in tumor cells the hydrolysis of asparagine by L-asparaginase drains all circulating asparagine, resulting in the depletion of serum asparagine, leading to starvation of the asparagine [5]. This leads to starvation of cancer cells and ultimately to DNA breaks, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [7,8]. As a result of these observations, L-asparaginase-containing therapies have been developed for the treatment of hematologic malignancies, including acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Native ASNase derived from Escherichia coli [9], a recombinant preparation of ASNase from E. coli [10] and two PEGylated forms of ASNase from native E. coli [11,12] are available. Additionally, the ASNase enzyme isolated from Erwinia chrysanthemi [13] and a recombinant version of it are also available [14].

The clinically used L-asparaginases are a notable example of a well-established therapeutic protein with the ability to elicit an immune response in patients, which is due, in part, to their bacterial origin and large size [15]. Problems associated with immunodeficiency and acute liver dysfunction are the main side effects of ASNase in leukemia therapy [16]. When L-asparaginase is administered to patients, both normal and leukemic lymphoblasts can cleave it via the lysosomal proteases cathepsin B and asparagine endopeptidase, enhancing antigenic antigen processing [17] and promoting an immune response [18,19,20]. This immune response is the main cause of discontinuation of L-asparaginase treatment and is known as hypersensitivity [21]. Adverse reactions caused by hypersensitivity include anaphylaxis, edema, serum sickness, bronchospasm, urticaria and exanthema, pruritus and swelling of the extremities, and erythema [18]. Currently, between 30% and 75% of patients exhibit some form of hypersensitivity, and up to 70% of patients develop antidrug antibodies [22]. Additionally, the production of anti L-asparaginase antibodies is known to alter the pharmacokinetics and clearance of the drug, which may be the cause of reported cases of reduced drug potency [23,24,25,26]. This induces a condition called subclinical hypersensitivity or silent inactivation, in which the efficacy of the drug is reduced or eliminated, and the patient is asymptomatic, resulting in poor therapeutic outcomes [5,27]. In general, this is a major disadvantage of the use of bacterial enzymes as therapeutic agents.

Several solutions have been explored to minimize the immunogenicity of bacterial asparaginase. These strategies include PEGylation, protein engineering, new asparaginase sources, N-glycosylation, among others [28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

Previous work involving the production of chimeric proteins has also been developed in association with ASNase. In 1995, Newsted et al. demonstrated that the resistance of L-asparaginase to proteolytic degradation by trypsin can be increased by developing a chimera comprising a fusion of the ASNase gene with that of a single-strand antibody derived from a pre-selected monoclonal antibody capable of providing protection against trypsin [35]. Engineered chimeric L-asparaginase retained 75% of its original activity after exposure to trypsin, while the native L-asparaginase control was completely inactivated [35]. In 2006, Qi Gaofu et al. developed a chimeric variant comprising asparaginase, tetanus toxin helper T-cell epitope and B-cell epitope of human cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) [36]. The chimeric enzyme was expressed as a soluble protein in Escherichia coli and once purified exhibited approximately 83% of native asparaginase activity [36]. With the bioinformatics boom, computational tools use for resolve problems associate to proteins immunogenicity has win a great relevant. It has been shown that de-immunogenization for therapeutic proteins by modifying T cell or B cell epitopes using bioinformatic tools and site-directed mutagenesis is a successful strategy for obtaining safer biopharmaceutical products [16,37,38]. Based on these ideas and on the high immunogenicity of E. coli asparaginase in 2021, Belén et al. developed in silico a chimera of L-asparaginase by replacing epitope peptides in the E. coli enzyme variant with peptides from human serum albumin, and even demonstrated proof of concept that the engineered variant is recombinantly expressed in E. coli (paper accepted for publication).

Native type variants of known human L-asparaginases are not suitable replacements for clinically used bacterial enzymes, as they have a very high KM value for Asn. Given the physiological blood concentration of Asn (~50 μM), the enzyme must have an Asn KM in the low micromolar range to be clinically relevant [39,40,41]. However, this does not limit the use of its fragments in epitope substitution in enzyme variants of other species to limit the development of an immune response in therapeutic treatments.

On this basis, this research proposal developed from E. coli L-asparaginase a humanized chimeric enzyme in silico. The in-silico detection of potentially antigenic and allergenic epitopes in bacterial ASNase and the substitution of these epitopes by peptide fragments of human ASNase with similar secondary structures was carried out, without affecting the active center, thereby avoiding the development of an immune response and obtaining a chemically and functionally stable in silico chimeric protein.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Determination of epitope density

Epitope density is defined as an alternative measure that makes it possible to estimate the degree of response of the immune system. It consists of a comparative analysis between the number of epitopes of two different proteins to predict which one is more immunogenic. For example, if you have two proteins X and Y, if protein X has many more epitopes than protein Y, then you can estimate that protein X will be more immunogenic than protein Y [52,53,54]

The calculation of the density of epitopes presented by MHC I and II has been of great use in the study of pathogens as well, since it has made it possible to determine how, by means of mutations and epitope regulations presented in these histocompatibility complexes, bacteria and viruses evade recognition by the immune system [55,56,57].

This method has also been widely used in the study of the degree of immunogenicity of many proteins for therapeutic purposes. Hence, in this study, the same concept of optical density was applied to evaluate the degree of immunogenicity of the E. coli L-asparaginase enzyme by calculating the relative frequency of the predicted immunogenic peptides. The aim was to demonstrate the high immunogenicity of the E. coli enzyme. The results showed the existence of 532 immunogenic peptides with a total relative frequency of 0.24, for a number of epitopes amounting to 2205 according to the peptide fragmentation that was designed (9 to 15 aa), indicating that about 1/4 of the total peptides into which the 3ECA protein was fragmented have the capacity to induce an immune response generating the adverse reaction to the treatment. This coincides with previous studies where the E. coli enzyme has been compared with ErA, finding that both present a high density of immunogenic epitopes homogeneously distributed in the structure[37]. This has been justified on the basis of the high sequence similarity of both bacterial enzymes [37,58].

On the other hand, after the coupling of the human and bacterial variants, 4O0H and 3ECA, it was found that the human variant presents 19.84% of sequence identity with 3 ECA, which is due to the evolutionary distance between bacteria and humans. However, both enzymes have the same functionality, which is indicative of the existence of a common ancestor for both. Also, since they present the same enzymatic function, there are structural residues that must be conserved and be common not only for these enzymes but for all those that belong to the same family in order to conserve the function of degrading asparagine[38,59,60]. It is known that human L-asparaginases are not suitable substitutes for clinically used bacterial enzymes, since they possess, unlike the E. coli-derived one, a KM value outside the micromolar range, which does not make them clinically relevant [40]. However, their human origin prevents the development of hypersensitivity by patients to the treatment [40,41].

The deimmunization of proteins for therapeutic use by substitution of potentially immunogenic epitopes of both T cells and B cells is a successful strategy in the development of safer biopharmaceuticals. In this case, E. coli L-asparaginase has high immunogenicity as demonstrated in ongoing research and preceding studies; therefore, obtaining fewer immunogenic mutated variants of the enzyme through different pathways constitutes a step forward in the use of this enzyme as a chemotherapeutic drug. Despite the low similarity between the human enzyme and that of bacterial origin, the human enzyme is an excellent candidate for peptide substitution in obtaining a less immunogenic humanized chimeric enzyme, since it makes the organism non-reactive to the selected fragments, thus lowering the threshold of the immune response to the use of a humanized chimera.

2.2. Mapping and structure determination of the chimeric enzyme

The in-silico design of the humanized chimeric enzyme included the substitution of peptides other than the native 3ECA protein. In the present study, two peptides were substituted from the native enzyme with a size of 15 amino acids each and affinity value for MHC II lower than 4 in a range from 0 to 10, indicating recognition and high affinity by MHC II toward these peptides from the native protein [37,42]. This is an important indicator to take into account when substituting fragments of the bacterial enzyme for fragments of human proteins, as it is a marker of how strongly the epitopes bind to MHC II and therefore indicates a favorable substitution to reduce immunogenicity [42].

There is a marked incidence of patients treated with L-asparaginase to suffer hypersensitivity reactions with a rate of 25% to 30% [61], for which reason the amount of immunogenic epitopes with allergenic capacity present in the structure of the 3ECA enzyme was considered in the development of the humanized chimeric enzyme. As a result, a high density of allergenic epitopes was obtained in the native protein, which is consistent with some studies that suggest that the bacterial enzyme from E. coli develops a greater hypersensitivity reaction than other enzymes of bacterial origin [29,37,62]. Several combinations of peptides were tested according to the allosomes studied and reported as more immunogenic. The most accepted combination corresponded to the VENLVNAVPQLKDIA peptide reported as immunogenic by the HLA-DRB1*08:01 allele and the DGPFNLYNAVVVTAAD peptide reported as immunogenic by the HLA-DRB1*01:01, HLA-DRB1*07:01, HLA-DRB1*15:01, HLA-DRB1*15:01 alleles. Previous studies indicate that the HLA-DRB1*07:01 allele is associated with a high risk of hypersensitivity in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with E. coli asparaginase [23,37,38]. It was also observed for the case of the HLA-DRB1*15:01 allele that this peptide was strong binding to MHC II. Taking this as background, it was decided that this conjugation of the two peptides would be the ideal one to substitute in the design of the chimeric enzyme, in order to decrease the allergenic load of the chimeric protein. The substitution of the DGPFNLYNAVVTAAD peptide for peptide analogs of the human protein caused a decrease of 14 immunogenic epitopes in the HLA-DRB1*07:01 allele in the chimeric enzyme compared to the native 3ECA, which increases the feasibility of using this enzyme in the treatment of patients with ALL by decreasing the probability of developing hypersensitivity with treatment associated with this specific allele.

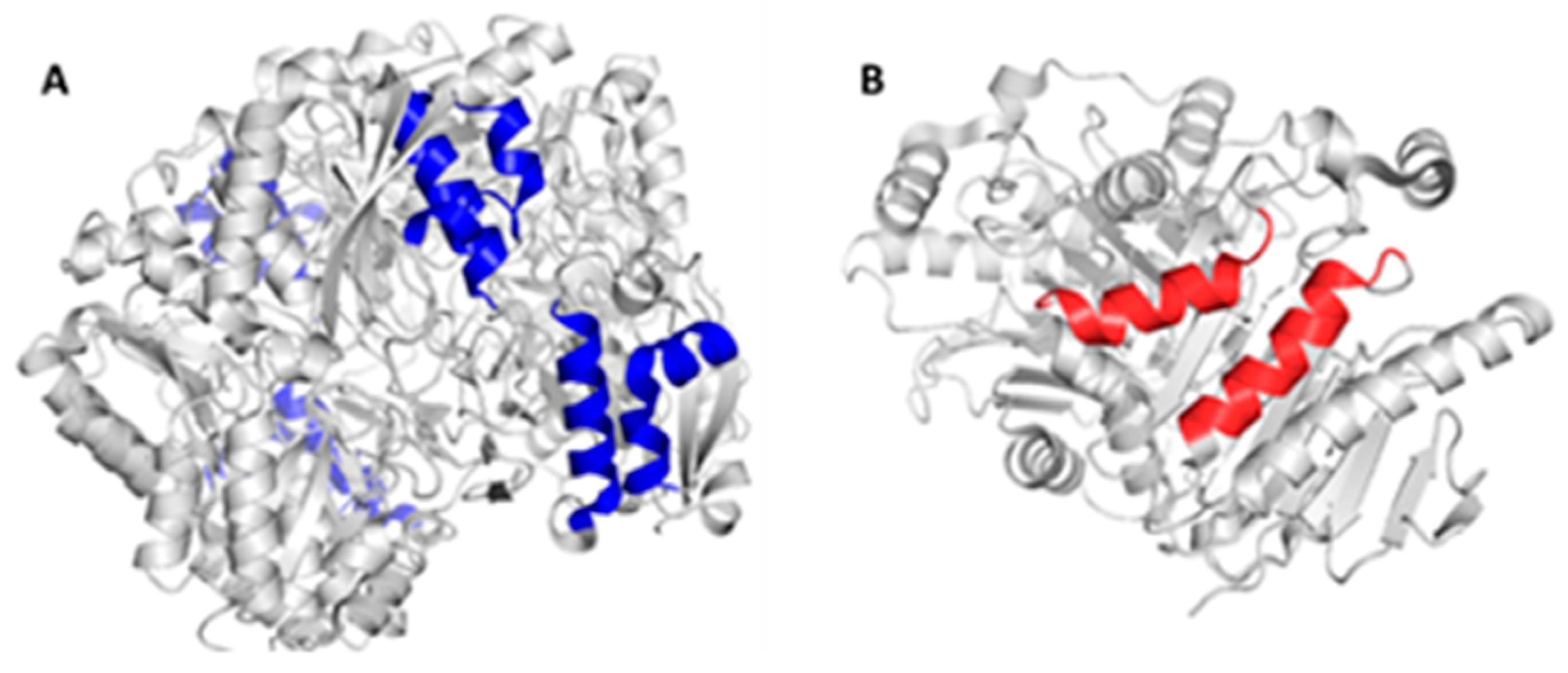

Considering the structural characteristics of the designed chimera protein as such, it was observed that the substituent polypeptide chains retain the same secondary structure in the form of an alpha helix, as the fragments of the native 3ECA mold protein.

Figure 1.

It is known that the secondary structure of proteins is the folding that the polypeptide chain adopts thanks to the formation of hydrogen bridges between the atoms that form the peptide bond. Hydrogen bridges are established between the -CO- and -NH- groups of the peptide bond (the former as an H acceptor and the latter as an H donor). In this way, the polypeptide chain is able to adopt conformations with lower free energy and is therefore more stable [63]. It is therefore essential that the peptide substituents of the chimeric enzyme retain this secondary structure, as the stability and functionality of the enzyme may be compromised.

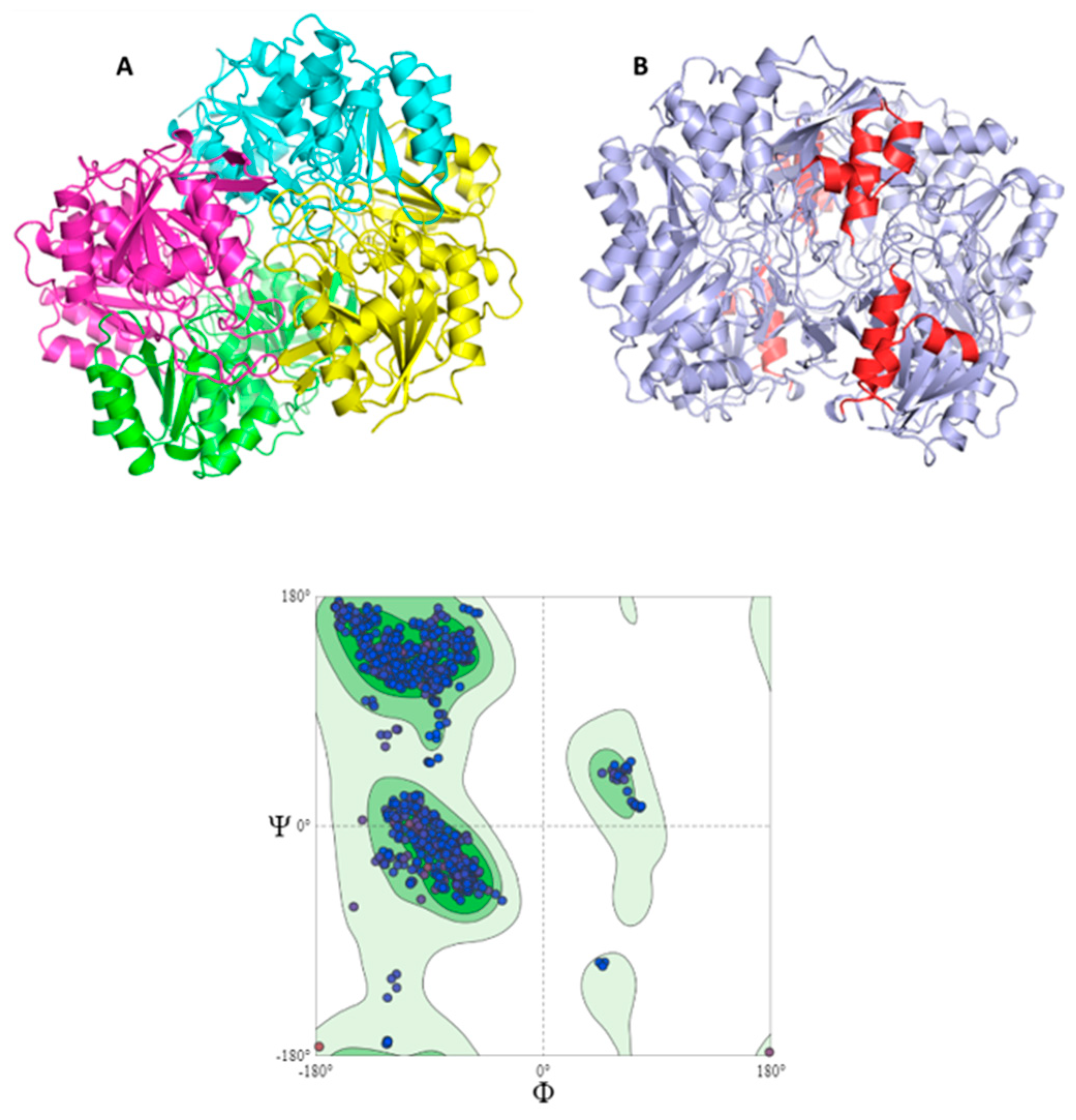

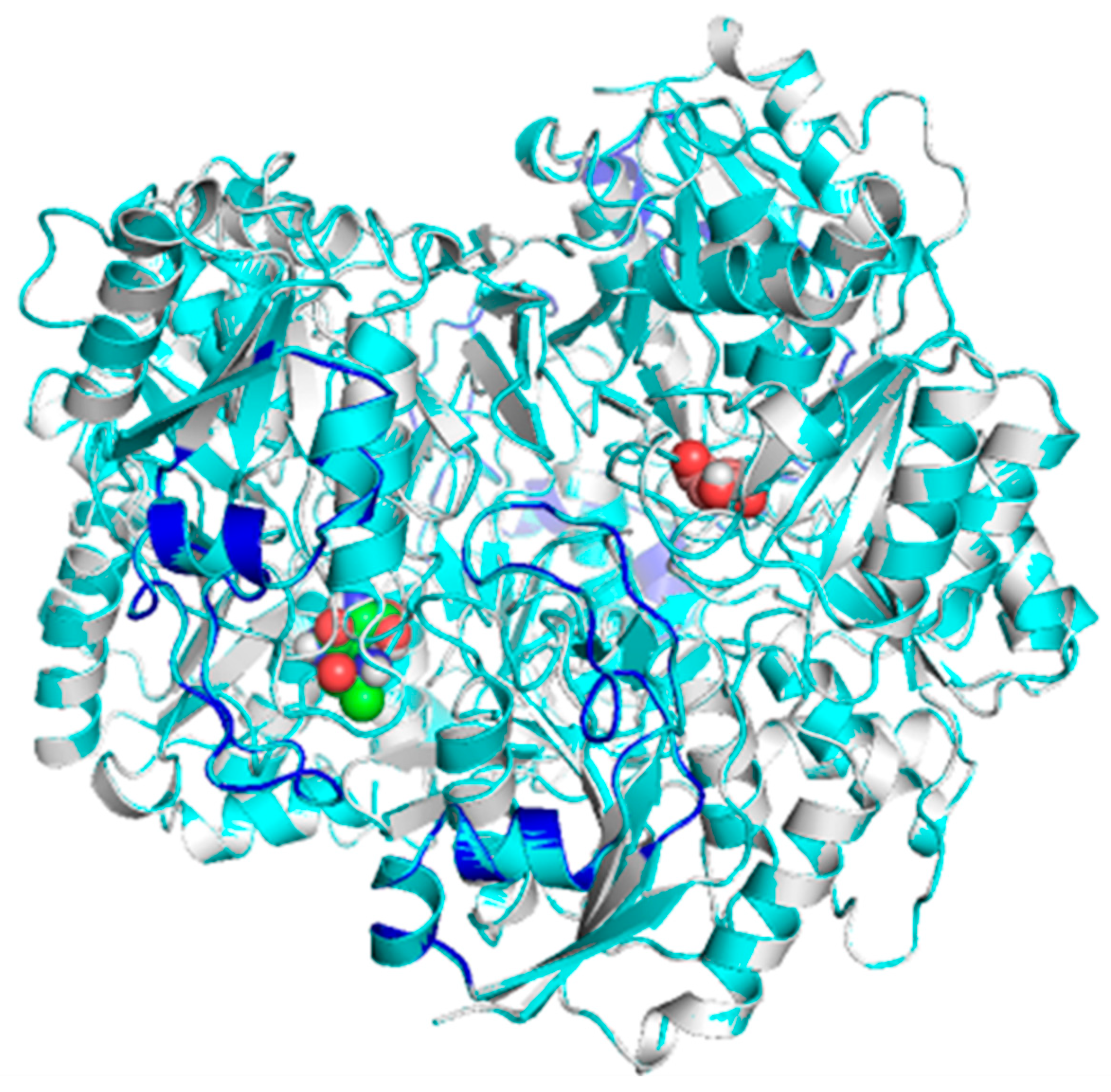

Morphologically, the chimeric protein obtained was characterized by 4 folded subunits that are distinguishable at a glance

Figure 2 (A and B). This coincides with what is reported in the literature for

E. coli L-asparaginase (3ECA), which is shown in its active conformation as a tetramer composed of 4 identical subunits A, B, C and D with an approximate symmetry of 222 [64,65]. The chimeric protein obtained by homology modeling was characterized as presenting stability and a correct arrangement of the three-dimensional structure. The results obtained in the Ramachandran plot were 96.06 % favorable zones

Figure 2 C. The result obtained for the present chimeric protein is indicative of the fact that most of the residues in the protein fall within the allowed areas of the diagram, especially in the regions corresponding to the β-sheets and α-helices. There are also some residues that fall in less common regions, encompassing even the area of the type II turns. Even so, there is a small fraction of residues that appear in forbidden areas of the diagram, which would indicate that the three-dimensional structure available to us is not perfect and presents some residues in positions where they are forced, so it would be unlikely that they were their real locations, but they do not limit or affect the stability of the protein.

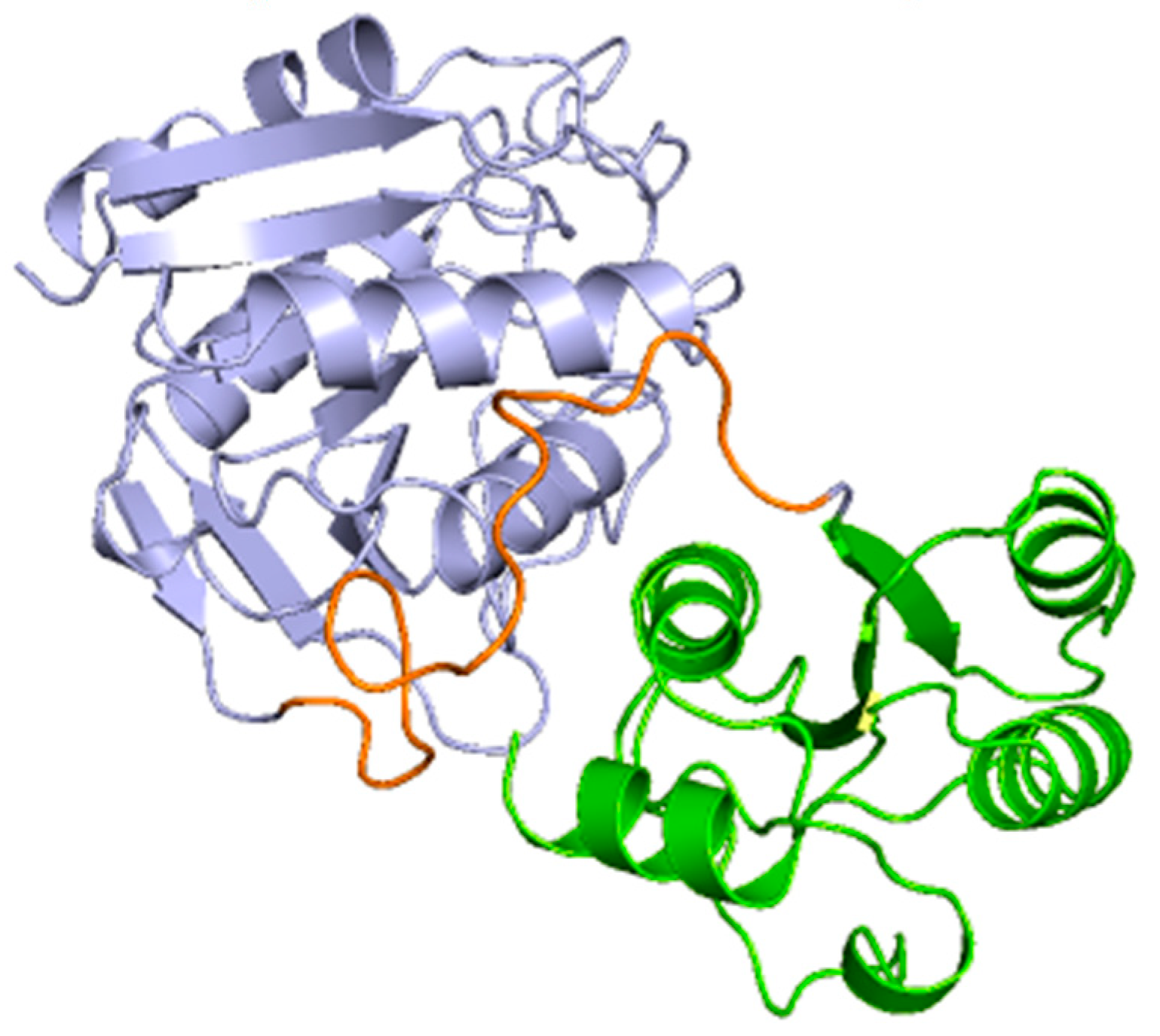

In the subunits of the obtained chimeric enzyme, it can be estimated that a single subunit is composed of two polypeptide clusters with a wide density of amino acids that fold independently, forming loops and turns, beta sheets and alpha helices. Also, it is observed that these dense populations of amino acids are connected by a loop extending from amino acids 190 to approximately 213. Although this analysis is not conclusive, it can give us an approximation of how the protein structure is maintained in the face of the imposed modifications.

Figure 3.

This analysis is consistent with the structure described for the basic subunit of the enzyme 3ECA, which distributes its amino acidic sequence into two α/ β domains that are connected by a linker sequence (191 aa- 212 aa) [64]. Additionally. for the C-terminal end of the protein subunit of the bacterial enzyme, the existence of 4 alpha helices and a beta sheet composed of 3 parallel strands has been shown [64]. These characteristics are common to the subunit of the modeled chimeric enzyme as shown in

Figure 3; therefore, it can be inferred that both proteins present the same folding and three-dimensional structure and that they only differ in the amino acid sequence.

This protein folding factor is primordial in the development of chimeras, since the basis of this process is mutation or amino acid substitution. The amino acid sequence constitutes the primary structure of a protein and governs protein folding. Introducing, substituting or mutating an amino acid can involve steric hindrance, the establishment of nonspecific bonds and the breaking of bonds that stabilize the protein. [63]. This can induce twisting of polypeptide chains, change of the secondary structure of the protein, chain breakage, exposure of residues from the internal environment to the external environment and vice versa, destabilization of the tertiary and quaternary structure of a protein, and even inactivation of the native structure and denaturation of the protein [63]. In addition, it is known that the activities of enzymes are determined by their three-dimensional structure, which in turn is determined by the amino acid sequence. Therefore, the conformational similarity between the humanized chimeric and native 3ECA proteins in active conformation of the present study constitutes a relevant factor, since it shows that there is a high probability that the chimeric protein, by conserving the folding of the native mold, also preserves the active center and the enzymatic activity intact.

2.3. Docking and enzymatic activity of the chimeric enzyme

It is possible that the change or modification induced in the original enzyme produces substrate displacement of the active site or keeps it in a closed conformation. In such a case, the chimeric enzyme would be inactive and lose its purpose. This is why it is of vital importance to verify the enzymatic activity of the chimeric mutant obtained once it has been modeled to ensure the efficiency of the mutations made.

In the chimeric protein of the present work, molecular docking was used as a technique to verify the presence of enzymatic activity and the conservation of the active site in comparison with the native enzyme.

The docking assay for the chimeric humanized enzyme that was developed showed 9 scoring functions that were increasing in value, indicating that the substrate, in this case asparagine, has 9 possible binding sites on the enzyme. Within these values the lowest were -5.8 and -5.6, being the positions corresponding to these data those in which the substrate has greater affinity for the enzyme and the enzyme-substrate complex is more stable. In this case, the value of -5.6 was chosen because these data coincide with the minimum value obtained by the same analysis for the native bacterial enzyme 3ECA. The value corresponding to -5.8 presupposes a hypothetical model where the affinity of the asparaginase-asparagine complex is maximum, but transient; it was subsequently found in the absence of a three-dimensional model that justifies this interaction.

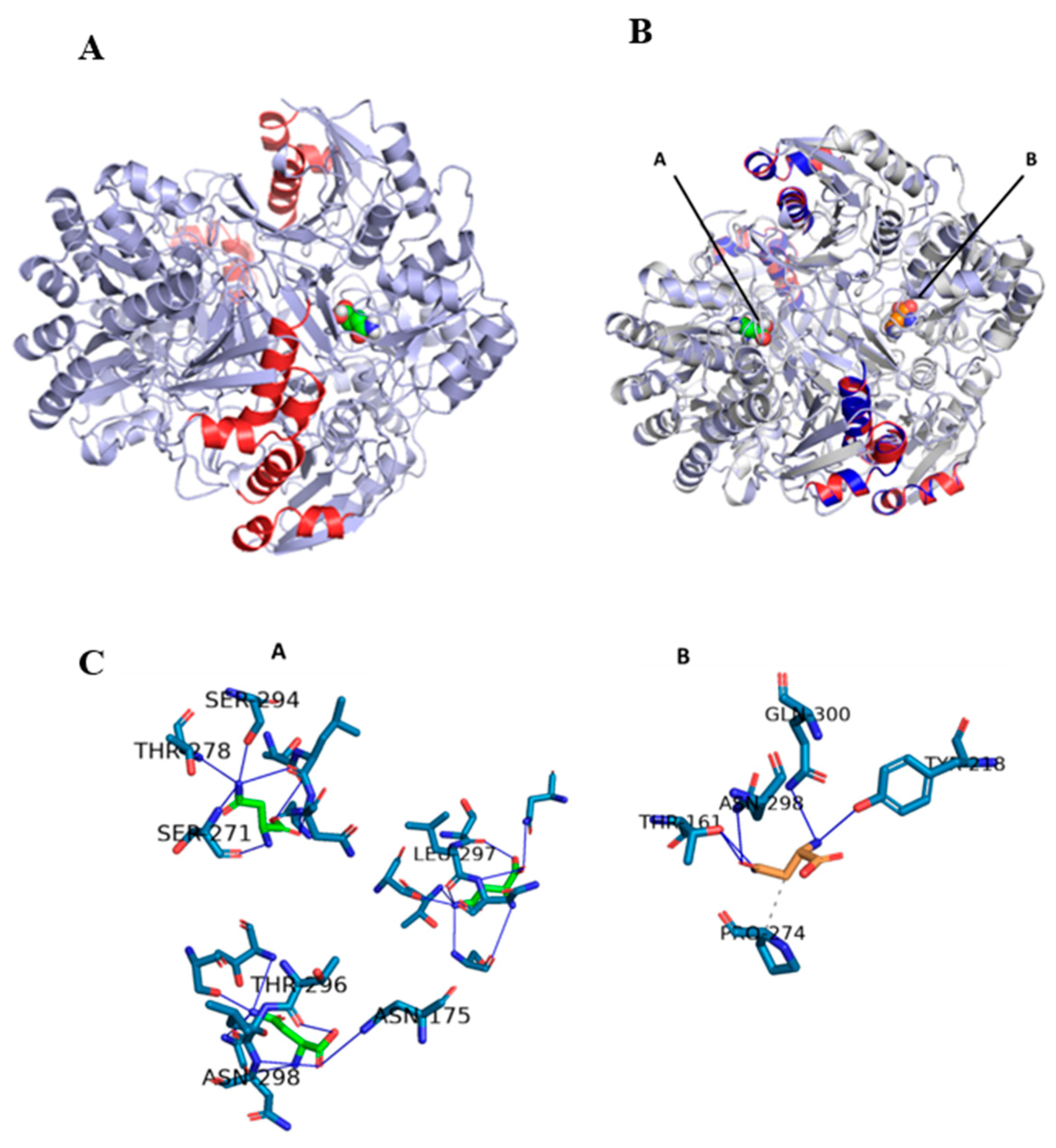

To contrast the adequate docking selection, the three-dimensional structure of the humanized chimeric protein coupled to the substrate was modeled and aligned with its counterpart (the native enzyme 3EAC-substrate complex)

Figure 4A and 4B. The result obtained showed a 100% coincidence of the structural conformation of both proteins, but instead the substrates were arranged in different dimers in an almost symmetrical way between them. Previous studies of the structure of the native 3ECA protein showed the existence of 4 active sites located between the subunits of the intimate dimers. The 4 active sites are distributed two in each dimer, making only the tetrameric enzyme functional. [64,65]. This increased the probability that the chimeric enzyme was functional, but in another active site different from the one modeled for the native 3ECA enzyme.

In order to demonstrate the presence of the substrate and an active center, of the 3 alternative ones, different from that of the chimeric protein, the residues that interact and form the active site of both enzymes were determined. The modeling of these residues showed that the developed chimera establishes 8 bonds with asparagine, all by hydrogen bonds, while the native bacterial mold protein only establishes 6 bonds, 5 by hydrogen bonds and 1 by hydrophobic interaction,

Figure 4C.

In terms of residues, it was observed that, in contrast to the native, the chimera enzyme retained the substrate bond with asparagine 298, instead the other remaining 7 bonds are approximately 5 residues away from their closest corresponding amino acid in the native structure. This is consistent with the fact that the active site is considered to be very versatile and dynamic [64,66]. Taking into account that the forces that maintain the structure of the active site are fundamentally weak interactions, in a set of molecules of the same enzyme there can be active sites that present different interconvertible conformational states, from those that greatly facilitate binding to the substrate to those that practically do not allow the entry of the substrate passing through all imaginable intermediate states [66]. Additionally, it is known that the enzyme has a loop towards the N-terminal end that blocks the active site regulating the entry and exit of substrate in a specific way [65]. Although a small fraction of this loop is modified in the chimeric enzyme as part of the enzyme construction process, it can be seen from an alignment of the chimeric and native sequences and a comparison of this with other homologous proteins, that the essential amino acids for the active site are conserved in the chimeric enzyme created. A superposition of the chimeric and template enzymes coupled to the substrate showed the conservation of the structure and position of this loop in the 4 monomers of both enzymes and their proximity to the substrate

Figure 5.

Taking all these docking data as background, it can be stated that the constructed chimeric enzyme retains its hydrolytic activity and is therefore a functional protein, despite the differential substrate arrangement.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Sequence data of L-asparaginases

For this study, the amino acid sequences as well as the native three-dimensional structure of the L-asparaginases from

Escherichia coli type II (EcA) and Homo sapiens were downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (

https://www.rcsb.org/) with the identification codes 3ECA and 4O0H, respectively. For subsequent analyses, the monomer of these enzymes was used.

3.2. T-cell epitope prediction and epitope density determination

For T-cell epitope prediction, the NetMHCII 4.0 server was used (

https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/service.php?NetMHCIIpan-4.0) [42], setting the default program parameters. Peptides predicted as "strong binding" (≤ 1%) and "weak binding" (≤ 5%) were selected as immunogenic epitopes. For the calculation of epitope density, the relative frequency was used: fi = ni ∕ N = ni ∕ ∑ ∑ jnj, where ni is the number of predicted immunogenic epitopes, and N is the total number of epitopes determined by the program (immunogenic and non-immunogenic). The epitope density of each protein was determined for the alleles HLA-DRB1*01:01, HLA-DRB1*03:01, HLA-DRB1*04:01, HLA-DRB1*07:01, HLADRB1*08:01, HLA-DRB1*11:01, HLA-DRB1*13:01, and HLADRB1*15:01, which are reference alleles with a broad global frequency [43,44]

3.3. Prediction of allergenic epitopes

Allergenicity prediction was performed using the AllerTOP v. 2.0 server (

http://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/AllerTOP/)[45]. Each of the T-cell epitopes predicted as immunogenic for the HLA-DRB1*04:01, HLA-DRB1*07:01 alleles, which fulfilled the conditions indicated above, was processed with this tool. The program evaluates the peptide sequence and returns the results as "probable allergen" or "probable non-allergen".

3.4. Epitope alignment and mapping

Once the results described above were obtained, the most exposed epitopes were selected and the epitopes of the bacterial enzyme were aligned in Clustal Omega Program (

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) with the human enzyme in search of possible substituents [46]. The PyMOL software (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.3.1 Schrödinger, LLC) was used to visualize the epitopes in the native structures of the enzymes. Once visualized, the three-dimensional structure of the epitopes was analyzed and the

E. coli L-asparaginase was humanized with the corresponding substituents.

3.5. Modeling of the three-dimensional structure of the chimeric enzyme

For the three-dimensional modeling of the protein, the SWISS Model software (

https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) was used to obtain the three-dimensional structure of the chimeric protein by homology [47]. Subsequently, the quality of the model was evaluated with the Rachamandram plot analysis, using the MolProbity tool [48] available on the SWISS-MODEL platform [47]

3.6. In silico determination of substrate affinity

To determine the substrate affinity in the chimeric enzyme, a Protein-Ligand Docking was performedwith the Autodock Vina program [49]which is integrated into PyRx software [50].To perform the molecular docking, an interaction region was established around the entire heterotetramer generated (Blind docking), setting the following parameters: center_x = 54.7089; center_y 20.7493 = ; center_z = 27.1783; size _x = 83.0180121136; size _y = 72.2542178059; size _z = 75.5301778221; and exhaustiveness = 8.0. After, by checking the interactions of the active center, was used the Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler program (

https://plip-tool.biotec.tu-dresden.de/plip-web/plip/index) [51].

3.7. Statistical analysis of epitope density

To compare the epitope density of both enzymes, a paired t-test (p < 0.05) was performed with the mean epitope densities using the statistical package GraphPad Prism version 5.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA).

4. Conclusion

The present work focused on the in-silico expression of a chimeric enzyme, generated from the substitution of the antigenic determinants present in the ASNase of E. coli 3ECA, by regions present in a human enzyme, which will make it possible to minimize the recognition by the immune system of the E. coli epitopes. The human 4O0H enzyme was used since this enzyme variant has not been used in previous studies. The results obtained demonstrated that it is possible to design a humanized chimeric enzyme with fragments of the human variant of the enzyme, using 3ECA as a template. It was found that the human enzyme is a good substitute because it presents less immunogenicity than the bacterial enzyme, although the difference is not significant. The humanized chimera obtained constitutes a step forward in the synthesis of this less immunogenic biopharmaceutical. Although the results obtained are promising, it still remains to express this variant in recombinant form and to perform stability and enzymatic activity assays in vitro, as well as to test the immunogenicity of the resulting enzyme in immunological assays in vitro and with animal models.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used Conceptualization, A.P. and L.H.; methodology, A.P.; software, J.B.; validation, A.P., L.H. and J.B.; formal analysis, A.P.; investigation, A.P., R.C and E.P; resources, J.F.; data curation, A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.; writing—review and editing, A.P., L.H, J.F and E.P; visualization, L.H. and J.F; supervision, L.H and J.F; project administration, J.F and A.Pd.; funding acquisition, J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Project – FAPESP-UFRO 2016/22065-5 “Production of extracelular L-asparaginase: from bioprospecting to the engineering of an antileukemic biopharmaceutical”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- J. T. de la Flor Brú Dra de la Calle Cabrera Directora Ejecutiva Dra MI Hidalgo Vicario, J. Pozo Román Vocales Regionales, J. Directiva de la SEPEAP, G. de Trabajo, and A. J. Bibliográficas López Ávila Asma Alergia J Pellegrini Belinchón Docencia MIR Dra O González Calderón Educación para la Salud Promoción del Desarrollo Psicoemocional PJ Ruiz Lázaro, “Consejo Editorial Subdirectores Ejecutivos Pediatría Integral,” 2016. [Online]. Available: www.sepeap.org.

- Pui, C.-H.; Yang, J.J.; Hunger, S.P.; Pieters, R.; Schrappe, M.; Biondi, A.; Vora, A.; Baruchel, A.; Silverman, L.B.; Schmiegelow, K.; et al. Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Progress Through Collaboration. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2938–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmiegelow, K.; Forestier, E.; Hellebostad, M.; Heyman, M.; Kristinsson, J.; Söderhäll, S.; Taskinen, M. Long-term results of NOPHO ALL-92 and ALL-2000 studies of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2010, 24, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batool, T.; Makky, E.A.; Jalal, M.; Yusoff, M.M. A Comprehensive Review on l-Asparaginase and Its Applications. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016, 178, 900–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, H. Use of ?-asparaginase in childhood ALL. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 1998, 28, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettinger, L.J.; Ettinger, A.G.; Avramis, V.I.; Gaynon, P.S. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia. BioDrugs 1997, 7, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Batra, S.; Zhang, J. Asparagine: A Metabolite to Be Targeted in Cancers. Metabolites 2021, 11, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.K.; Verma, S.; Pati, R.; Sengupta, M.; Khatua, B.; Jena, R.K.; Sethy, S.; Kar, S.K.; Mandal, C.; Roehm, K.H.; et al. Mutations in Subunit Interface and B-cell Epitopes Improve Antileukemic Activities of Escherichia coli Asparaginase-II. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 3555–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, R.; Hunger, S.P.; Boos, J.; Rizzari, C.; Silverman, L.; Baruchel, A.; Goekbuget, N.; Schrappe, M.; Pui, C. L-asparaginase treatment in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer 2011, 117, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Völler, S.; Pichlmeier, U.; Zens, A.; Hempel, G. Pharmacokinetics of recombinant asparaginase in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2018, 81, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, A.R. Pegaspargase (Oncaspar). J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 1995, 12, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloos, R.; van der Sluis, I.M.; Mastrobattista, E.; Hennink, W.; Pieters, R.; Verhoef, J. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia patients treated with PEGasparaginase develop antibodies to PEG and the succinate linker. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 189, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- V. I., & T. P. N. Avramis, “Asparaginase pharmacokinetics and implications of therapeutic drug monitoring. In Leukemia and Lymphoma.,” Int J Nanomedicine, 2006.

- Lin, T.; Dumas, T.; Kaullen, J.; Berry, N.S.; Choi, M.R.; Zomorodi, K.; Silverman, J.A. Population Pharmacokinetic Model Development and Simulation for Recombinant Erwinia Asparaginase Produced in Pseudomonas fluorescens (JZP-458). Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2021, 10, 1503–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, M.; Nadler, S.G. Immunogenicity to Biotherapeutics–The Role of Anti-drug Immune Complexes. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, M.H.G.; Fiúza, T.d.S.; Bath de Morais, S.; Souza, T.d.A.C.B.d.; Trevizani, R. Circumventing the side effects of L-asparaginase. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 139, 111616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, M.K.L.; Chan, G.C.-F. Drug-induced amino acid deprivation as strategy for cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- I Avramis, V.; Tiwari, P.N. Asparaginase (native ASNase or pegylated ASNase) in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int. J. Nanomed. 2006, 1, 241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Offman, M.N.; Krol, M.; Patel, N.; Krishnan, S.; Liu, J.; Saha, V.; Bates, P.A. LYMPHOID NEOPLASIA Rational engineering of L-asparaginase reveals importance of dual activity for cancer cell toxicity. Blood 2011, 117, 1614–1621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peterson, R.G.; Handschumacher, R.E.; Mitchell, M.S. Immunological responses to l-asparaginase. J. Clin. Investig. 1971, 50, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asselin, B.L.; Fisher, V. Impact of Clinical and Subclinical Hypersensitivity to Asparaginase in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2014, 18, E107–E112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, W.P.; Larsen, E.L.; Devidas, M.; Linda, S.B.; Blach, L.; Carroll, A.J.; Carroll, W.L.; Pullen, D.J.; Shuster, J.; Willman, C.L.; et al. Augmented therapy improves outcome for pediatric high risk acute lymphocytic leukemia: Results of Children's Oncology Group trial P9906. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2011, 57, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.A.; Smith, C.; Yang, W.; Daté, M.; Bashford, D.; Larsen, E.; Bowman, W.P.; Liu, C.; Ramsey, L.B.; Chang, T.; et al. HLA-DRB1*07:01 is associated with a higher risk of asparaginase allergies. Blood 2014, 124, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belviso, S.; Iuliano, R.; Amato, R.; Perrotti, N.; Menniti, M. The human asparaginase enzyme (ASPG) inhibits growth in leukemic cells. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leader, B.; Baca, Q.J.; Golan, D.E. Protein therapeutics: A summary and pharmacological classification. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalk, A.M.; Nguyen, H.-A.; Rigouin, C.; Lavie, A. Identification and Structural Analysis of an l-Asparaginase Enzyme from Guinea Pig with Putative Tumor Cell Killing Properties. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 33175–33186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrovsky, V.S.; Kazanov, M.D.; Dyakov, I.N.; Pokrovskaya, M.V.; Aleksandrova, S.S. Comparative immunogenicity and structural analysis of epitopes of different bacterial L-asparaginases. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marini, B.L.; Perissinotti, A.J.; Bixby, D.L.; Brown, J.; Burke, P.W. Catalyzing improvements in ALL therapy with asparaginase. Blood Rev. 2017, 31, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrooman, L.M.; Supko, J.G.; Neuberg, D.S.; Asselin, B.L.; Athale, U.H.; Clavell, L.; Kelly, K.M.; Laverdière, C.; Michon, B.; Schorin, M.; et al. Erwinia asparaginase after allergy to E. coli asparaginase in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2010, 54, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, D. Glycoengineered Pichia-based expression of monoclonal antibodies. In Glycosylation Engineering of Biopharmaceuticals; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Effer, B.; Lima, G.M.; Cabarca, S.; Pessoa, A.; Farías, J.G.; Monteiro, G. L-Asparaginase from E. chrysanthemi expressed in glycoswitch®: Effect of His-Tag fusion on the extracellular expression. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 49, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moola, Z.B.; Scawen, M.D.; Atkinson, T.; Nicholls, D.J. Erwinia chrysanthemi l-asparaginase: Epitope mapping and production of antigenically modified enzymes. Biochem. J. 1994, 302, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, X.; Le Jeune, C. Erythrocyte encapsulated l-asparaginase (GRASPA) in acute leukemia. Int. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 5, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.J.; Zalewska-Szewczyk, B. Hypersensitivity reactions to asparaginase therapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Immunology and clinical consequences. Futur. Oncol. 2022, 18, 1285–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsted, W.; Ramjeesingh, M.; Zywulko, M.; Rothstein, S.; Shami, E. Engineering resistance to trypsin inactivation into l-asparaginase through the production of a chimeric protein between the enzyme and a protective single-chain antibody. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 1995, 17, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaofu, Q.; Rongyue, C.; Dan, M.; Xiuyun, Z.; Xuejun, W.; Jie, W.; Jingjing, L. Asparaginase Display of Human Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein (CETP) B Cell Epitopes for Inducing High Titers of Anti-CETP Antibodies In Vivo. Protein Pept. Lett. 2006, 13, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belén, L.H.; Lissabet, J.B.; Rangel-Yagui, C.d.O.; Effer, B.; Monteiro, G.; Pessoa, A.; Avendaño, J.G.F. A structural in silico analysis of the immunogenicity of l-asparaginase from Escherichia coli and Erwinia carotovora. Biologicals 2019, 59, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belén, L.H.; Lissabet, J.F.B.; Rangel-Yagui, C.d.O.; Monteiro, G.; Pessoa, A.; Farías, J.G. Immunogenicity assessment of fungal l-asparaginases: An in silico approach. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belviso, S.; Iuliano, R.; Amato, R.; Perrotti, N.; Menniti, M. The human asparaginase enzyme (ASPG) inhibits growth in leukemic cells. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, A.; Gervais, D. What makes a good new therapeutic l-asparaginase? World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigouin, C.; Nguyen, H.A.; Schalk, A.M.; Lavie, A. Discovery of human-like L-asparaginases with potential clinical use by directed evolution. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreatta, M.; Karosiene, E.; Rasmussen, M.; Stryhn, A.; Buus, S.; Nielsen, M. Accurate pan-specific prediction of peptide-MHC class II binding affinity with improved binding core identification. Immunogenetics 2015, 67, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Galarza, F.F.; Christmas, S.; Middleton, D.; Jones, A.R. Allele frequency net: A database and online repository for immune gene frequencies in worldwide populations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D913–D919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesch, J.S.Z.; Lauer, G.M.; Day, C.L.; Kim, A.Y.; Ouchi, K.; Duncan, J.E.; Wurcel, A.G.; Timm, J.; Jones, A.M.; Mothe, B.; et al. Broad Repertoire of the CD4+ Th Cell Response in Spontaneously Controlled Hepatitis C Virus Infection Includes Dominant and Highly Promiscuous Epitopes. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 3603–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, I.; Bangov, I.; Flower, D.R.; Doytchinova, I. AllerTOP v.2—A server for in silico prediction of allergens. J. Mol. Model. 2014, 20, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sievers, F.; Higgins, D.G. Clustal Omega. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2014, 48, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; De Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.B.; Arendall, W.B.; Headd, J.J.; Keedy, D.A.; Immormino, R.M.; Kapral, G.J.; Murray, L.W.; Richardson, J.S.; Richardson, D.C. MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallakyan, S.; Olson, A.J. Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Salentin, S.; Schreiber, S.; Haupt, V.J.; Adasme, M.F.; Schroeder, M. PLIP: Fully automated protein–ligand interaction profiler. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W443–W447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissabet, J.F.B. A large-scale immunoinformatics analysis of the human papillomaviruses reveals a common E5 oncoprotein-pattern to evade the immune response. Gene Rep. 2018, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, M.; Howard, J.G.; Desaymard, C. Role of Antigen Structure in the Discrimination between Tolerance and Immunity by B Cells. Immunol. Rev. 1975, 23, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, Y. High epitope density in a single protein molecule significantly enhances antigenicity as well as immunogenicity: A novel strategy for modern vaccine development and a preliminary investigation about B cell discrimination of monomeric proteins. Eur. J. Immunol. 2005, 35, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey-Kellogg, C.; Gutiérrez, A.H.; Moise, L.; Terry, F.; Martin, W.D.; De Groot, A.S. CHOPPI: A web tool for the analysis of immunogenicity risk from host cell proteins in CHO-based protein production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2014, 111, 2170–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, A.S.; Moise, L.; Liu, R.; Gutierrez, A.H.; Tassone, R.; Bailey-Kellogg, C.; Martin, W. Immune camouflage: Relevance to vaccines and human immunology. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2014, 10, 3570–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; De Groot, A.S.; Gutierrez, A.H.; Martin, W.D.; Moise, L.; Bailey-Kellogg, C. Integrated assessment of predicted MHC binding and cross-conservation with self reveals patterns of viral camouflage. BMC Bioinform. 2014, 15, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narta, U.K.; Kanwar, S.S.; Azmi, W. Pharmacological and clinical evaluation of l-asparaginase in the treatment of leukemia. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2007, 61, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belén, L.H.; Lissabet, J.F.B.; Rangel-Yagui, C.d.O.; Monteiro, G.; Pessoa, A.; Farías, J.G. Immunogenicity assessment of fungal l-asparaginases: An in silico approach. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissabet, J.F.B.; Belén, L.H.; Lee-Estevez, M.; Risopatrón, J.; Valdebenito, I.; Figueroa, E.; Farías, J.G. The CatSper channel is present and plays a key role in sperm motility of the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2020, 241, 110634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, W.E.; Tsiatis, A.; Rivera, G.; Murphy, S.B.; Dahl, G.V.; Denison, M.; Crom, W.R.; Barker, L.F.; Mauer, A.M. Anaphylactoid reactions to escherichia coli and erwinia asparaginase in children with leukemia and lymphoma. Cancer 1982, 49, 1378–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körholz, D.; Urbanek, R.; Nürnberger, W.; Jobke, A.; Göbel, U.; Wahn, V. Formation of specific IgG antibodies in l-asparaginase treatment. Distribution of IgG subclasses. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 1987, 135, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Victoria, M.; Guillén, L. ESTRUCTURA Y PROPIEDADES DE LAS PROTEÍNAS Máster Ingeniería Biomédicadica.

- Swain, A.L.; Jaskólski, M.; Housset, D.; Rao, J.K.; Wlodawer, A. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli L-asparaginase, an enzyme used in cancer therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 1474–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, T.S.; Scapin, S.M.; de Andrade, W.; Fasciotti, M.; de Magalhães, M.T.; Almeida, M.S.; Lima, L.M.T. Biophysical characterization of two commercially available preparations of the drug containing Escherichia coli L-Asparaginase 2. Biophys. Chem. 2021, 271, 106554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, N.; Holliday, G.L.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Jacobsen, J.O.B.; Pearson, W.R.; Thornton, J.M. The Catalytic Site Atlas 2.0: Cataloging catalytic sites and residues identified in enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D485–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).