Introduction

Malaria is a public health problem in Sub-Saharan Africa, spread mainly by the members of the

Anopheles funestus group and

the Anopheles gambiae species complex [

1]

. An. funestus group comprises five subgroups of which three of these subgroups contain at least thirteen (13) species; identified in various ecological niches across Africa [

2].

Anopheles funestus sensu stricto (s.s.) (hereafter

An. funestus) belongs to the

Funestus subgroup which has seven members, namely:

An. funestus, An. aruni, An. vaneedeni, An. funestus-like, An. confuses, An. longipalpis type C and

An. parensis [

2,

3]. Of this group,

An. funestus is a major vector responsible for high malaria transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. Three of the members of the

An. funestus group;

An. funestus, An. rivulorum and An. leesoni were found sympatrically in various ecological zones in Kenya, [

4] Sudan [

5] and Nigeria [

6,

7] suggesting that they have effective reproductive isolation mechanisms.

While most of the species of the

Anopheles funestus group can be found only in certain geographical areas in Africa,

An. funestus has a wide range of geographical distribution covering several various climatic types and is the most devastating efficient human malaria vector exhibiting consistent notorious anthropophilic (prefer human habitation), anthropophagic (biting humans), endophilic (indoor resting) and endophagic (indoor biting) behaviours [

8,

9]. Its capacity to transmit human malaria far outpaced

Anopheles gambiae and

Anopheles arabiensis in some endemic areas in Africa [

8,

10].

An. funestus can adapt and colonize different ecological niches owing to its high resistance and changing breeding environments. A previous study in Kenya revealed that

An. funestus breeds in various habitats and co-breeds with

An. gambiae sensu.lato,

Culex spp and other vectors in the same habitats [

11]. The vector survival rate, behaviour, ecology, vectorial capacity, and host-pathogen interactions are all affected by external environmental stress. This external stress such as temperature change, land-use changes, host migration, and insecticide use, plays a crucial role in mosquito population selection [

12]. Based on microsatellite markers, Ogola et al [

13] noted three genetically different clusters (FUN1, FUN2 and FUN3) of

An. funestus in Kenya. The largest cluster (FUN1) is from samples from Rift Valley Regions and western regions and the other clusters (FUN2 and FUN3) are from the coastal region.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequences are genetic drift-sensitive and have high copy numbers, availability of conserved primer binding sequences, and ease of amplification hence they are widely employed in interpreting molecular taxonomy, phylogenetic relationships, population structure, and genetic diversity in malaria vectors [

14]. Indeed, mtDNA markers have been utilized to study the genetic variances and evolutionary relationships of many mosquito species, as well as to correctly quantify gene flow and changes between populations [

15,

16]. Cytochrome oxidase subunits II gene (mtDNA-COII) is the mitochondrial marker that has unique properties of maternal inheritance are devoid of recombination, intraspecific polymorphism, highly variable compared to nuclear DNA and small effective population size, therefore they are good markers for studying genetic diversity, gene flow and population structure [

17]. Mitochondrial genetic diversity and molecular phylogeny are becoming increasingly important in mosquito research [

18].

The population structure and genetic diversity of An. funestus might influence its adaptation and efficiency of malaria transmission in western Kenya. Delineating the fine-scale population structure of vectors might be useful to investigate the genetic basis of speciation and local adaptation processes. Moreover, understanding gene flow among An. funestus populations could help to assess their movement in natural populations and therefore, how the populations are segregated. These could be of great importance in vector control strategies. This study was designed to investigate the genetic structure and diversity and gene flow of a major vector, An. funestus in a malaria-endemic region of western Kenya using mitochondrial marker mtDNA-COII.

Materials and Methods

Mosquito Sampling

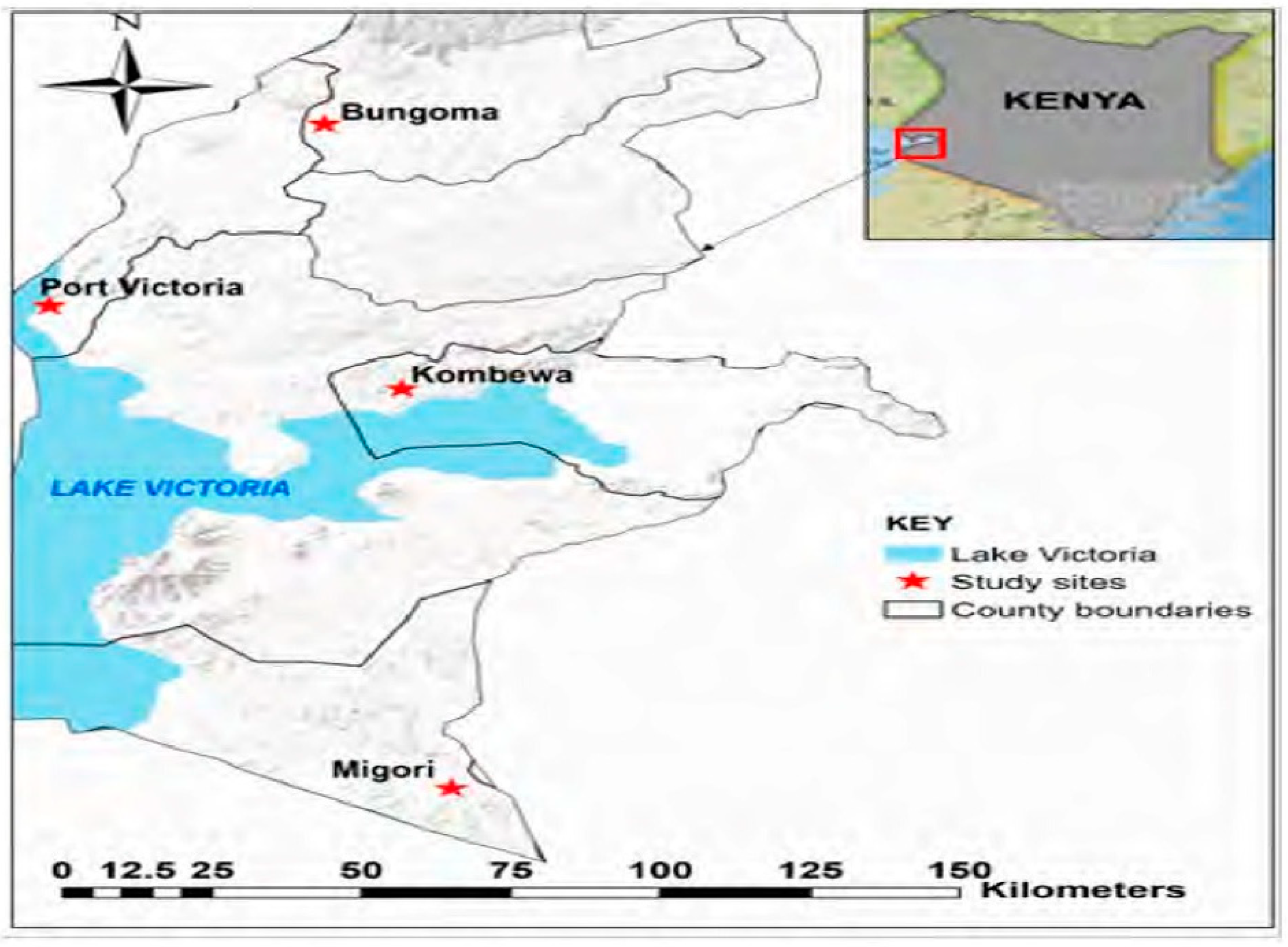

Anopheles funestus mosquitoes were collected from four malaria transmission areas (Port Victoria, Migori, Bungoma and Kombewa,) in four counties in western Kenya.

Figure 1 shows the locations in the various counties where samples were collected. Adult mosquitoes were sampled inside indoor living rooms using pyrethrum spray catches and mechanical aspirators. All mosquitoes were morphologically identified as

An. funestus sensu lato following morphological keys [

19]. Each sample was stored in a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube containing cotton wool and silica gel and was stored at -4

oC for subsequent molecular identification to confirm the species.

DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification and Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from the whole mosquito using the Chelex

®-100 method [

20]. Funestus-specific PCR was conducted to confirm species using the species-specific primers (ITS2A/FUN) in the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS2) on the ribosomal DNA as described by [

21]. The mtDNA-COII gene was amplified using forward (5'-TCT AAT ATG GCA GAT TAG TGC A-3') and reverse (5'-ACT TGC TTT CAG TCA TCT AAT G-3') primers. A 23µl PCR mixture containing 3 µl genomic DNA, 0.5 µl each of forward and reverse primers, 11.5 µl master mix with PerfeCTa

® ToughMix

® (5x) and 7.5 of PCR water. The PCR conditions include initial denaturation at 95

0C for 3 minutes, denaturation of 95

0C for 15 seconds, annealing at 41

0C for 30 seconds, extension at 72

0C for 1 minute and 30 seconds for 35 cycles and final extension at 72

0C for 7 minutes. The amplicons' quality was assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis in 1.5% w/v agarose gel stained with 2 µl smart glow and visualized using the SmartDoc imaging system (Accuris

Tm instruments). All the amplicons were bidirectionally sequenced with the same primers used for the PCR using 3730 BigDye

® Terminator v3.1 Sequencing Standard kit on ABI PRISM

® 3700 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Data Analysis

De novo assembly of paired raw reads was performed using Geneious prime software version 2022.0.1 [

22] and CLC Genomics Workbench [

23]. Low-quality reads with low base calling accuracy below 99% (Phred 20) were excluded from the analysis. ClustalW algorithm, a platform in BioEdit version 7.2.5 [

24], was used in generating multiple sequence alignment. DnaSP Version 6.12.03 [

25] was used to compute genetic diversity indices [haplotype diversity (Hd), number of haplotypes (h), nucleotide diversity (π), number of segregating sites (S) and mean number of pairwise difference (k)] and Neutrality tests (Tajima’s

D, Fu and Li’s D, Fu and Li’s F, and Fu's Fs statistics). The analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was performed in Arlequin version 3.5.2 [

26] to partition genetic variations among groups (Port Victoria, Migori, Bungoma and Kombewa,) and within groups. Population Analysis with Reticulate Trees (Popart) version 1.7 [

27] was used to infer haplotype networks.

The best-fitting nucleotide substitution model was estimated with the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) implemented in MEGA version 11.0.13 [

28]. The Bayesian phylogenetic analysis was performed by MrBayes v3.2.7 [

29] using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods. The MCMC was run for 2,000,000 generations with sampling tree topologies every 1,000 generations, after excluding the initial 25% as ‘burn-in’. To root the tree,

Anopheles gambiae, Aedes albopictus, and

Culex pipiens pallens were the “outgroup” (accession # MG930872, MG930866, KX383916, and KT851543). The previously reported mtDNA-COII sequences of

An. funestus from Kenya and other African countries were also included in the phylogenetic tree. The 50% majority rule consensus tree was constructed with Bayesian posterior probabilities of the nodal supports. The output tree was visualized and edited with an online tool Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v5 [

30].

Results

Genetic Diversity of An. funestus in Western Kenya

A total of 126 (Port Victoria-38, Migori-38, Bungoma-22, and Kombewa-28) amplicon sequences of mtDNA-COII were used for population genetic analysis. A total of 64 haplotypes were identified, suggesting that there is high haplotype diversity in the populations (Hd= 0.97 to 0.98) but low nucleotide diversity (Π=0.004) based on mtDNA-COII sequences (

Table 1). Moreover, the statistical test of neutrality revealed significant (p<0.05) negative Tajima’s

D and Fs values indicating a deviation from a standard neutral model and population expansion with an excess of low-frequency alleles due to evolutionary forces (

Table 1). There was no significant difference in observed mutations across the four populations (X2=181.744, df 189,

P=0.635).

Population Structure and Gene Flow

AMOVA results showed that there was no genetic differentiation across all four populations (Fst = -0.01). Specifically, our result revealed that there was no genetic differentiation between Port Victoria and Migori (Fst= -0.010), Bungoma and Kombewa (Fst= -0.016), Port Victoria and Bungoma (Fst = -0.020), Migori and Bungoma (Fst= -0.008), Port Victoria and Kombewa (Fst = -0.009), Migori and Kombewa (Fst= -0.003) (

Table 2). The lack of population structure was supported by a high level of gene flow across the four populations (Gamma St, Nm=15.40). The highest gene flow was between Port Victoria and Bungoma (Gamma St. Nm= 35.22). This was followed by Port Victoria and Migori (Gamma St, Nm= 30.25). The lowest gene flow was between Migori and Kombewa (Gamma St. Nm=17.99) (

Table 2).

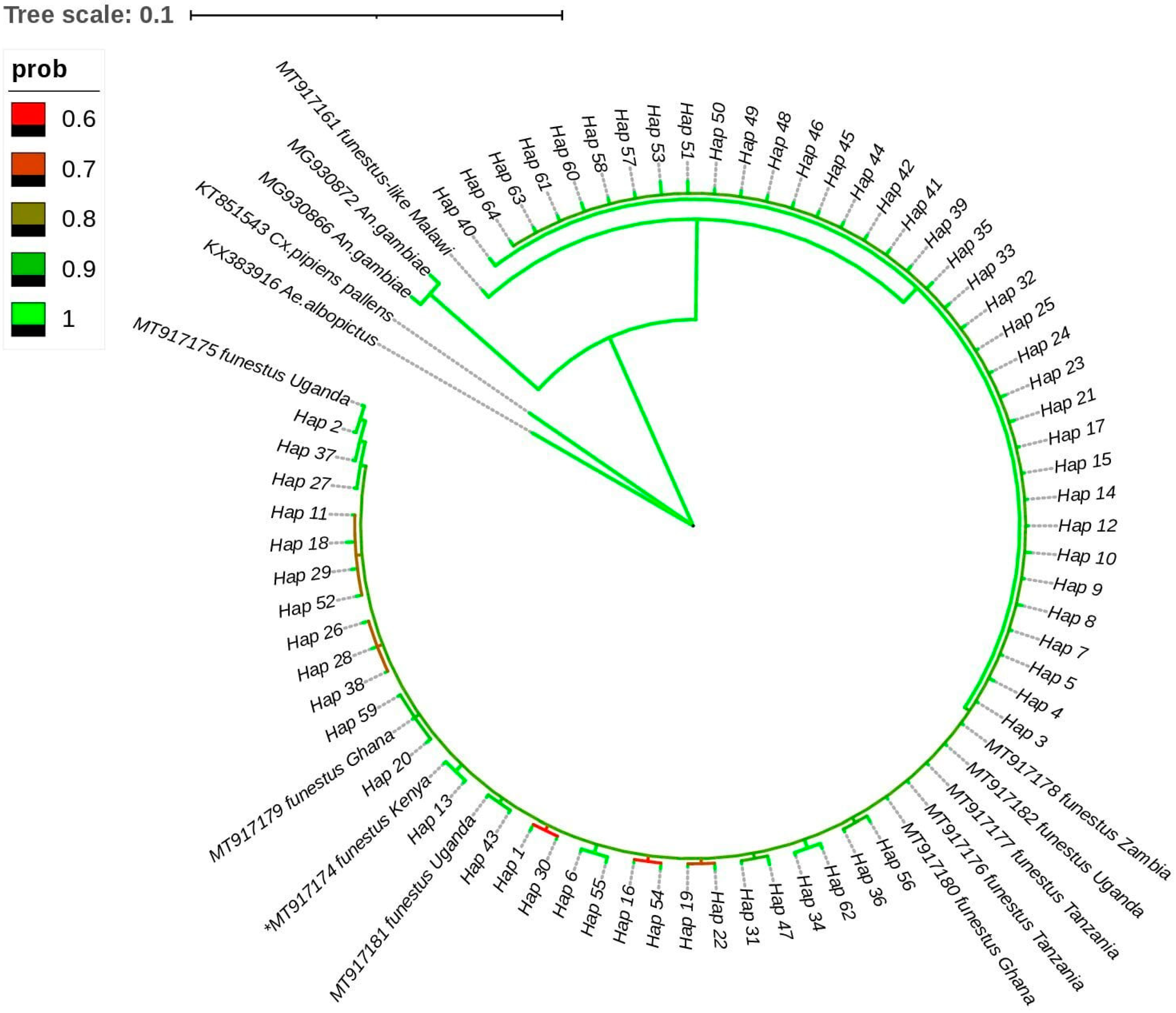

Phylogenetic Relationships and Network Analyses

The best-fit model for nucleotide substitution was identified by MEGA 11 as a Tamura 3-parameter with gamma-distributed rate heterogeneity (T92 + G) according to the Bayesian information criterion for mtDNA-COII haplotypes. The phylogenetic tree was inferred by Bayesian analyses with the standard deviation of split frequency values (<0.01). The phylogenetic estimates from the MCMC analyses strongly supported the monophyletic group (posterior probability = 1) (

Figure 2). There is no clear clustering of haplotypes observed and all the 64 identified haplotypes in western Kenya shared a common ancestor with

An. funestus-like (accession # MT917161) from Malawi, with the closest haplotype (Hap 40) coming from the Migori and Port Victoria study sites, which border Tanzania and Uganda, respectively.

Anopheles funestus samples from Port Victoria and Bungoma (Hap 2) shared a recent common descendant with

An. funestus (accession # MT917175) from Uganda.

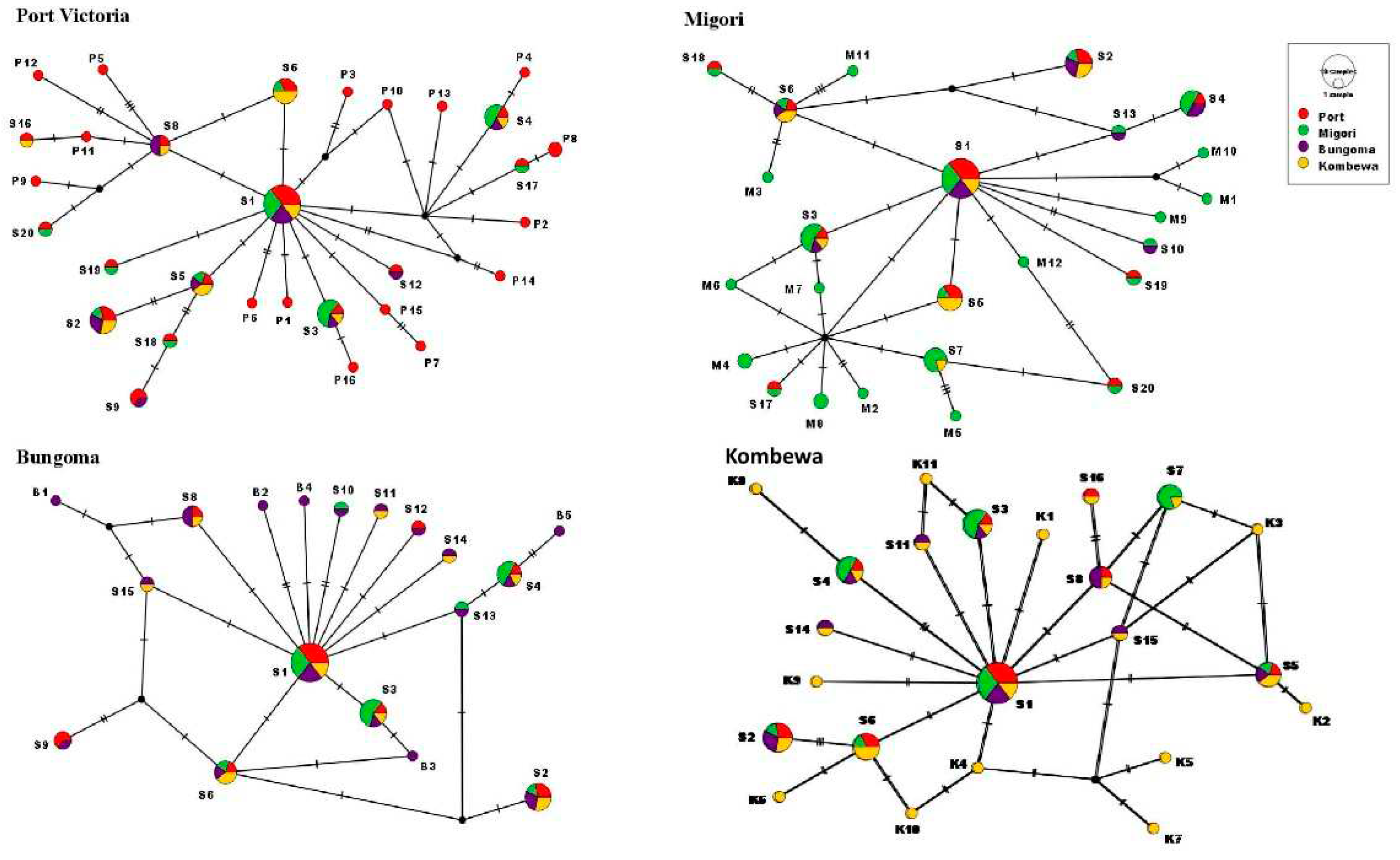

Haplotype networks were constructed using the Median-Joining method in PopART software. Out of the 64 distinct haplotypes identified in western Kenya, 30 (46.9%) were found from the Port Victoria study site (

Table 1). Twenty (31.3%) of the 64 haplotypes were shared across the study sites. The median-joining haplotype network of the mtDNA-COII gene revealed the genealogy of each of the observed haplotypes with haplotypes S1-S20 being shared across the study sites (

Figure 3). In the four study sites, the most common haplotype was S1 (14/64, 21.9%), followed by S3 (7/64, 10.9%), S2 (7/64, 10.9%), S4 (6/64, 9.4%), S6 (6/64, 9.4%), and S8 (4/64, 6.3%). The distribution of the S1 haplotype among the 64 observed haplotypes was as follows: 8%, 6%, 5%, and 3% in Port Victoria, Migori, Bungoma, and Kombewa, respectively. The haplotype (S1) could be an ancestral haplotype (recent common ancestor) among

An. funestus in western Kenya. Port Victoria and Bungoma populations had the most shared mutations (52.9%) followed by Migori and Port Victoria as well as with Kombewa each at 50%. Port Victoria and Kombewa populations had the least shared number of mutated sites (42%). Nucleotide sequences of the 64 identified haplotypes were submitted to Gene Bank and assigned accession numbers ON931353-ON931416.

Discussion

This study revealed the population genetic structure of

An. funestus population across four counties in western Kenya using a mitochondrial marker, mtDNA-COII. In the context of malaria control strategies including genetic alteration of vector species, information on genetic diversity and population structure of vectors is critical [

31]. In recent years, changes in the ecology of vector populations have been documented [

11]. High tolerance to a variety of ecological niches, insecticide resistance, and vast geographic distribution make

An. funestus a highly adaptable dominant vector species [

32].

This study revealed the signature of the population expansion, with weak population structure and high levels of gene flow among the population of

An. funestus from areas with varied

P. falciparum transmission intensities in western Kenya. Generally,

An. funestus exhibited low nucleotide diversity with Port Victoria exhibiting a high level of genetic diversity as compared to other regions. In western Kenya, the high genetic diversity of

An. funestus population compared to coastal regions based on microsatellite markers was reported a decade ago [

33]. The observed high number of haplotypes in Kombewa, Migori, and Port Victoria among this primary vector is consistent with high levels of

Plasmodial transmission in these study sites as compared to the rest of other malaria vectors [

34,

35]. Port Victoria which is also proximal to Lake Victoria had a significantly highest number of haplotypes circulating in the area. Port Victoria is the main Lake Victoria transport corridor between Kenya, the Islands, and Uganda. It was earlier reported that small wooden boats played a significant role in the transportation of mosquitoes between the mainland and the Islands [

36]. This might have resulted in high gene flow hence low nucleotide and high haplotype diversity in that site. Port Victoria has also been documented to have a high malaria prevalence with vector control interventions ongoing [

37]. The high gene flow observed in the populations could be due to migration and a lack of geographical barriers [

15]. Mountain ranges, rivers, forests, and other physical barriers, in combination with climatic or biological obstacles like flight range and breeding grounds, may obstruct gene flow between

Anopheles populations. However, none of these factors served as a barrier to gene flow in the

An. funestus population in western Kenya. The Rift Valley is known to serve as a barrier to gene flow [

4] nonetheless our findings showed that there are no physical barriers to hamper gene flow among mosquito populations in western Kenya. Different breeding sites, mosquito migration, environmental changes, and human activities act to shape the genetic diversity of

An. funestus populations [

38].

Given the low Fst values and high Gamma St Nm values, there is a strong indication of a high level of inbreeding across the population. As a result, most of the haplotypes in this study are shared among the western Kenya region contributing to a weak or lack of population structure. However, with the excess frequency of rare alleles, a genetic signature for population expansion can persist for a long period, masking any genuine ecological population or genetic structure that may exist [

39]. The observed no genetic differentiation, negative selection, and population expansion suggest that there was a free exchange of genes among

An. funestus populations in western Kenya. The presence of a negative signature of selection on this gene is an indicator of purifying selection acting on the gene to preserve the genetic structure by eliminating deleterious mutations [

40].

With evidence of purifying selection and population expansion, it is possible evolutionary forces shaping

An. funestus population in western Kenya could be the usage of LLINs, IRS and insecticide use for agricultural activities, especially those affecting larval breeding sites [

41,

42]. The high number of haplotypes per study site, new species and the population expansion observed in this study suggest the high adaptability of

An. funestus to various ecological requirements hence sustaining its vectorial capacity and malaria transmission.

Molecular identification confirmed that

An. funestus is the main vector of the

An. funestus group in western Kenya which is consistent with previous findings [

11,

43]. The other members of the

An. funestus group identified include

Anopheles funestus-like, Anopheles longipalpis and

Anopheles parensis in Kenya.

Anopheles funestus-like was first discovered in Malawi, Southern Africa in 2009 [

44].

Anopheles funestus-like and

An. funestus are members of the

Funestus subgroup which exist sympatrically [

44,

45]. Experiments have shown that they are separate species and no evidence of hybridization was observed between them [

44]. The role of

Anopheles funestus-like in malaria transmission is unknown. Most of the sibling species of

An. funestus group's role in malaria transmission is not fully understood although speculations are rife that they may be playing a role as secondary vectors. The recent identification of new species suggests that mosquitoes are invading new ecological niches and may be involved in malaria transmission. It is critical to correctly identify sibling species to design successful vector management measures. Failure to detect sibling species, for example, can make it difficult to tell the difference between a vector and a non-vector. When two or more sibling species are not distinguished, assessing the impact of control measures can be extremely imprecise. The discovery of sibling species gives vector and vector-borne control a whole new level. With the unravelling of new species and the presence of selection pressure, continuous entomological surveillance is needed to ascertain the distribution and role of new species in the malaria ecosystem and their response to various vector control tools.

Conclusions

This study had shown that the An. funestus population in western Kenya is under selection pressure leading to demographic expansion and the spread of variants through inbreeding among varied transmission sites in western Kenya. Population expansion suggests there is high adaptability of this species to various ecological requirements hence sustaining its vectorial capacity and malaria transmission.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.D. and Y.A.A.; methodology, I.D. and S.A.O; software, I.D., K.O.O. and D.Z.; validation, I.D. and D.Z.; formal analysis, I.D., K.O.O. and D.Z.; investigation, I.D., M.G.M., K.O.O. and E.O.M.; resources, G.Y.; data curation, I.D. and D.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, I.D.; writing—review and editing, I.D., K.O.O., W.O.O., S.A.O., D.Z. and L.E.A.; visualization, I.D.; supervision, A.K.G., Y.A.A., L.E.A. and G.Y.; project administration, I.D. and A.K.G.; funding acquisition, G.Y. and Y.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (R01 A1123074, U19 AI129326, R01 AI050243, and D43 TW001505). There was no additional external funding received for this study. The funders, however, did not play any role in designing, data collection and manuscript writing.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal consent was sought from heads of households before mosquitoes were collected inside the living rooms.

Data Availability Statement

This study’s datasets are available in online repositories. The accession numbers for the haplotype sequence data submitted to the gene bank are ON931353-ON931416.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Sinka, M.E.; Bangs, M.J.; Manguin, S.; Coetzee, M.; Mbogo, C.M.; Hemingway, J.; Patil, A.P.; Temperley, W.H.; Gething, P.W.; Kabaria, C.W. The Dominant Anopheles Vectors of Human Malaria in Africa, Europe and the Middle East: Occurrence Data, Distribution Maps and Bionomic Précis. Parasit. Vectors 2010, 3, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbach, R.E. Mosquito Taxonomic Inventory. 2013. Available online: http://Mosquito-Taxonomic-Inventory.Info/ (Accessed on June 2020).

- Garros, C.; Harbach, R.E.; Manguin, S. Morphological Assessment and Molecular Phylogenetics of the Funestus and Minimus Groups of Anopheles (Cellia). J. Med. Entomol. 2005, 42, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamau, L.; Munyekenye, G.O.; Koekemoer, L.L.; Hunt, R.H.; Coetzee, M. A Survey of the Anopheles Funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) Group of Mosquitoes from 10 Sites in Kenya with Special Emphasis on Population Genetic Structure Based on Chromosomal Inversion Karyotypes. J. Med. Entomol. 2003, 40, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhawi, A.M.; Aboud, M.A.; Raba’a, F.M.E.; Osman, O.F.; Elnaiem, D.E.A. Identification of Anopheles Species of the Funestus Group and Their Role in Malaria Transmission in Sudan. J. Appl. Ind. Sci. 2015, 3, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Awolola, T.S.; Oyewole, I.O.; Koekemoer, L.L.; Coetzee, M. Identification of Three Members of the Anopheles Funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) Group and Their Role in Malaria Transmission in Two Ecological Zones in Nigeria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005, 99, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temu, E.A.; Minjas, J.N.; Tuno, N.; Kawada, H.; Takagi, M. Identification of Four Members of the Anopheles Funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) Group and Their Role in Plasmodium Falciparum Transmission in Bagamoyo Coastal Tanzania. Acta Trop. 2007, 102, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaindoa, E.W.; Matowo, N.S.; Ngowo, H.S.; Mkandawile, G.; Mmbando, A.; Finda, M.; Okumu, F.O. Interventions That Effectively Target Anopheles Funestus Mosquitoes Could Significantly Improve Control of Persistent Malaria Transmission in South-Eastern Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sougoufara, S.; Diédhiou, S.M.; Doucouré, S.; Diagne, N.; Sembène, P.M.; Harry, M.; Trape, J.-F.; Sokhna, C.; Ndiath, M.O. Biting by Anopheles Funestus in Broad Daylight after Use of Long-Lasting Insecticidal Nets: A New Challenge to Malaria Elimination. Malar. J. 2014, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, M.; Fontenille, D. Advances in the Study of Anopheles Funestus, a Major Vector of Malaria in Africa. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 34, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrah, I.; Afrane, Y.A.; Amoah, L.E.; Ochwedo, K.O.; Mukabana, W.R.; Zhong, D.; Zhou, G.; Lee, M.-C.; Onyango, S.A.; Magomere, E.O.; et al. Larval Ecology and Bionomics of Anopheles Funestus in Highland and Lowland Sites in Western Kenya. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouache, K.; Fontaine, A.; Vega-Rua, A.; Mousson, L.; Thiberge, J.-M.; Lourenco-De-Oliveira, R.; Caro, V.; Lambrechts, L.; Failloux, A.-B. Three-Way Interactions between Mosquito Population, Viral Strain and Temperature Underlying Chikungunya Virus Transmission Potential. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 281, 20141078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogola, E.O.; Odero, J.O.; Mwangangi, J.M.; Masiga, D.K.; Tchouassi, D.P. Population Genetics of Anopheles Funestus, the African Malaria Vector, Kenya. Parasit. Vectors 2019, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, D.E. Genetic Markers for Study of the Anopheline Vectors of Human Malaria. Int. J. Parasitol. 2002, 32, 1607–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunmee, K.; Thaenkham, U.; Saralamba, N.; Ponlawat, A.; Zhong, D.; Cui, L.; Sattabongkot, J.; Sriwichai, P. Population Genetic Structure of the Malaria Vector Anopheles Minimus in Thailand Based on Mitochondrial DNA Markers. Parasit. Vectors 2021, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeraratne, T.C.; Surendran, S.N.; Walton, C.; Karunaratne, S.H.P. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Malaria Vector Mosquitoes Anopheles Subpictus, Anopheles Peditaeniatus, and Anopheles Vagus in Five Districts of Sri Lanka. Malar. J. 2018, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Zhong, D.; Lo, E.; Fang, Q.; Bonizzoni, M.; Wang, X.; Lee, M.-C.; Zhou, G.; Zhu, G.; Qin, Q. Landscape Genetic Structure and Evolutionary Genetics of Insecticide Resistance Gene Mutations in Anopheles Sinensis. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, R.; Luo, C.; Deng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, D. Molecular Phylogeny of Anopheles Nivipes Based on MtDNA-COII and Mosquito Diversity in Cambodia-Laos Border. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, M. Key to the Females of Afrotropical Anopheles Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Malar. J. 2020, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musapa, M.; Kumwenda, T.; Mkulama, M.; Chishimba, S.; Norris, D.E.; Thuma, P.E.; Mharakurwa, S. A Simple Chelex Protocol for DNA Extraction from Anopheles Spp. JoVE J. Vis. Exp. 2013, e3281. [Google Scholar]

- Koekemoer, L.L.; Kamau, L.; Hunt, R.H.; Coetzee, M. A Cocktail Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay to Identify Members of the Anopheles Funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) Group. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002, 66, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; et al. Geneious Basic: An Integrated and Extendable Desktop Software Platform for the Organization and Analysis of Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matvienko, M. CLC Genomics Workbench. In Plant Anim. Genome Sr Field Appl. Sci. CLC Bio Aarhus DE; 2015.

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A User-Friendly Biological Sequence Alignment Editor and Analysis Program for Windows 95/98/NT. In Proceedings of the Nucleic Acids Symposium Series; c1979–c2000; Information Retrieval Ltd.: London, 1999; Volume 41, pp. 95–98.

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis of Large Data Sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Excoffier, L.; Lischer, H.E. Arlequin Suite Ver 3.5: A New Series of Programs to Perform Population Genetics Analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010, 10, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D. POPART: Full-Feature Software for Haplotype Network Construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Van Der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference and Model Choice across a Large Model Space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (ITOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, F.H.; James, A.A. Genetic Modification of Mosquitoes. Sci. Med. 1996, 3, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dia, I.; Guelbeogo, M.W.; Ayala, D. Advances and Perspectives in the Study of the Malaria Mosquito Anopheles Funestus. Anopheles Mosquitoes—New Insights Malar. Vectors 2013, 10, 55389. [Google Scholar]

- Braginets, O.P.; Minakawa, N.; Mbogo, C.M.; Yan, G. Population Genetic Structure of the African Malaria Mosquito Anopheles Funestus in Kenya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003, 69, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Afrane, Y.A.; Vardo-Zalik, A.M.; Atieli, H.; Zhong, D.; Wamae, P.; Himeidan, Y.E.; Minakawa, N.; Githeko, A.K.; Yan, G. Changing Patterns of Malaria Epidemiology between 2002 and 2010 in Western Kenya: The Fall and Rise of Malaria. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ototo, E.N.; Mbugi, J.P.; Wanjala, C.L.; Zhou, G.; Githeko, A.K.; Yan, G. Surveillance of Malaria Vector Population Density and Biting Behaviour in Western Kenya. Malar. J. 2015, 14, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Minakawa, N.; Beier, J.; Yan, G. Population Genetic Structure of Anopheles Gambiae Mosquitoes on Lake Victoria Islands, West Kenya. Malar. J. 2004, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A.M.; Gething, P.W.; Alegana, V.A.; Patil, A.P.; Hay, S.I.; Muchiri, E.; Juma, E.; Snow, R.W. The Risks of Malaria Infection in Kenya in 2009. BMC Infect. Dis. 2009, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samb, B.; Dia, I.; Konate, L.; Ayala, D.; Fontenille, D.; Cohuet, A. Population Genetic Structure of the Malaria Vector Anopheles Funestus, in a Recently Re-Colonized Area of the Senegal River Basin and Human-Induced Environmental Changes. Parasit. Vectors 2012, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, A.R.; Harpending, H. Population Growth Makes Waves in the Distribution of Pairwise Genetic Differences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1992, 9, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meiklejohn, C.D.; Montooth, K.L.; Rand, D.M. Positive and Negative Selection on the Mitochondrial Genome. TRENDS Genet. 2007, 23, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasteur, N.; Raymond, M. Insecticide Resistance Genes in Mosquitoes: Their Mutations, Migration, and Selection in Field Populations. J. Hered. 1996, 87, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Obando, O.A.; Bona, A.C.D.; Duque, L.J.E.; Navarro-Silva, M.A. Insecticide Resistance and Genetic Variability in Natural Populations of Aedes (Stegomyia) Aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) from Colombia. Zool. Curitiba 2015, 32, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogola, E.O.; Fillinger, U.; Ondiba, I.M.; Villinger, J.; Masiga, D.K.; Torto, B.; Tchouassi, D.P. Insights into Malaria Transmission among Anopheles Funestus Mosquitoes, Kenya. Parasit. Vectors 2018, 11, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillings, B.L.; Brooke, B.D.; Koekemoer, L.L.; Chiphwanya, J.; Coetzee, M.; Hunt, R.H. A New Species Concealed by Anopheles Funestus Giles, a Major Malaria Vector in Africa. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009, 81, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, L.C.; Norris, D.E. Phylogeny of Anopheline (Diptera: Culicidae) Species in Southern Africa, Based on Nuclear and Mitochondrial Genes. J. Vector Ecol. J. Soc. Vector Ecol. 2015, 40, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).