1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is the largest operational risk event in recent history and has stress-tested large corporations and SMEs alike. However, this pandemic reached Syria in a very difficult time where Syrian SMEs have not yet recovered from the consequences of a long war with its companying economic and financial downturn. This pandemic has not only represented a major threat to Syrian SMEs but also created many opportunities and caused radical changes to the dynamics of the Syrian SME sector. Although SMEs’ failure has negative spillovers to all parts of the economy, the adverse consequences of such failure may exceed its economic sides to social and political unrest.

The spread of this pandemic in Syria was late compared to other countries in the region such as Lebanon, Jordan and Iran with the first laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 case was reported on 22 March 2020. The number of daily confirmed cases peaked in Nov 2021 to 520 cases according to John Hopkins University CSSE Covid-19 data with total confirmed cases of 57406 in Dec 2022 (Ministry of Health 2022). However, limited resources and testing capacities due to war and sanctions question the accurateness of such figures and suggest that many cases may go unreported (Al Ahdab 2021).

The pandemic has added further challenge to the multiple challenges which Syria are facing due to the manifold crisis and has caused further decline of economic and social indicators, particularly the total estimated GDP decrease of 9.15% during 2019 and 2020. Meanwhile, the inflation rate increases between June 2019 and June 2020 by around 85% and the average of workers in the micro, small and medium enterprise sector, which is considered a job generating sector and a driver of economic recovery, decreased (United Nations 2022).

Most firms and governments around the world assumed that this pandemic would be virulent and burn out within a few months. However, the death tool and the consequent lock downs and curfews to combat the transmission of the virus pose significant threats to the business sector and particularly to SMEs. Varying economic intervention measures were used by different countries to tackle the consequences of the quarantine but largely fell short to mitigate the pandemic damage.

Prior evidence on the impact of crises and pandemics on SMEs is documented in many articles. However, the special Syrian SMEs’ environment and the multiple adverse conditions of both the extended war and Covid-19 pandemic make the Syrian environment an interesting case study for research and investigation. Hence, this study bridges this gap and provides insight into intervention and adaptation in such special conditions. In addition, previous studies survey SMEs on the challenges and adaptation measures they take to cope with the pandemic. However, we also survey other stakeholders in the Syrian SME ecosystem such as microfinance institutions, banks, and public authorities to reach a full understanding of these issues.

The aim of this article is threefold. First, we are interested in determining the forms of adversity facing Syrian SMEs due to the pandemic. Second, we aim to understand what coping strategies SMEs employ to adapt to the new environment created by the pandemic. Third, we want to identify and evaluate the government intervention measures designed to support SMEs during the COVID-19 crisis. This is central to develop appropriate interventions to protect SMEs from the consequences of similar lockdowns and to alleviate the effects of future crises.

The remaining sections are organized as follow.

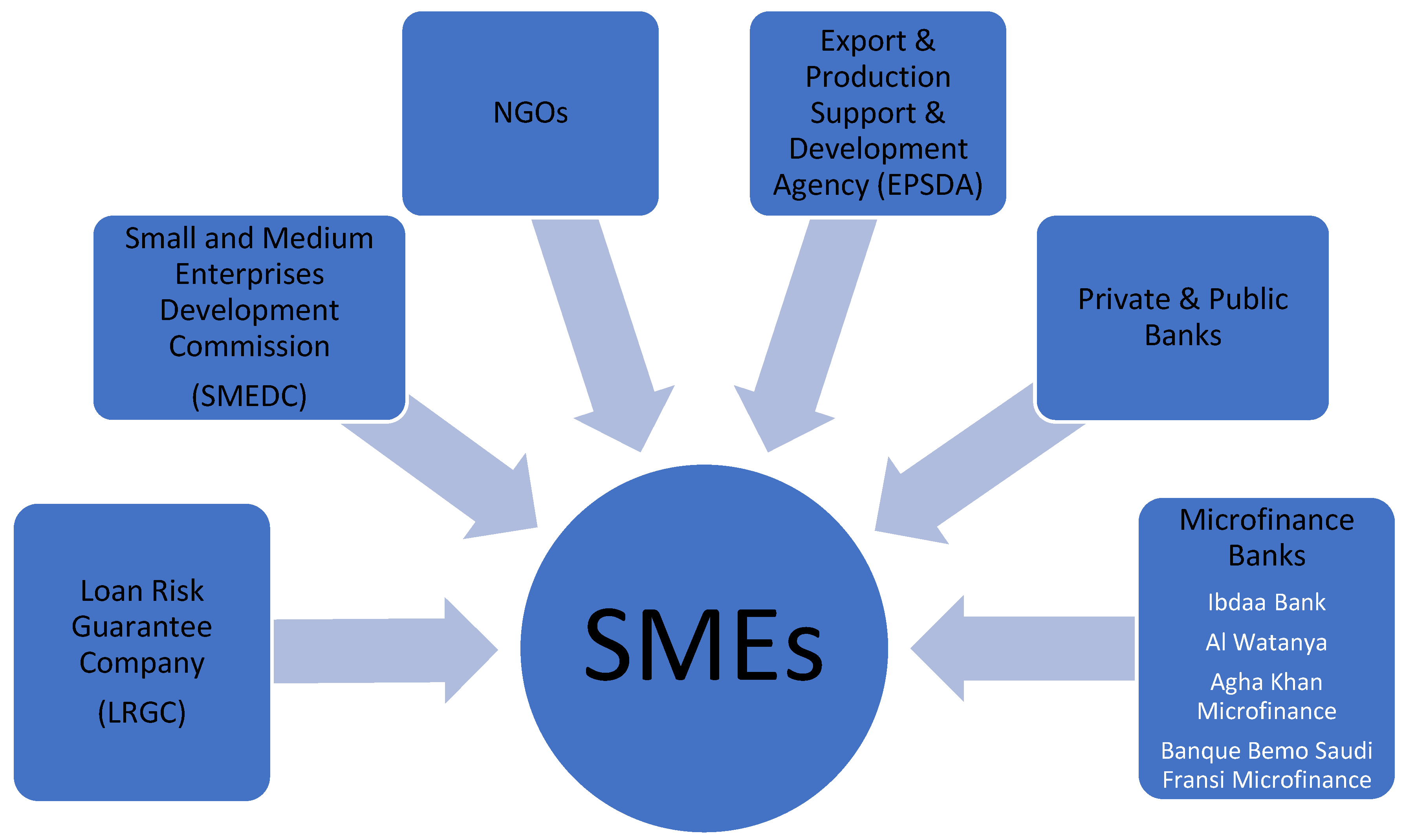

Section 2 will discuss the current situation of SMEs in Syria and illustrates the constituents of the Syrian SMEs ecosystem.

Section 3 reviews the literature on the challenges that face SMEs during crisis times, their coping strategies and government interventions to alleviate the crisis adversities.

Section 4 explains the research methodology.

Section 5 presents the results and section 6 concludes and advance recommendations.

2. The Situation of SMEs in Syria

SMEs represent the backbone of the Syrian Economy with over 99 percent of business classified as SMEs (SMEDC 2022). While SMEs drive innovation and competitiveness in many countries and represent 44 percent of the US economy (US Small Business Administration 2019), Syrian SMEs concentrate on agriculture and handicraft business and lack innovation capabilities. Such situation is similar to the status que of SMEs in many emerging countries where SMEs fail to progress into large companies and continue to marginally contribute towards exports.

In 2000, the unemployment has reached 10.5% (The Central Bank of Syria 2003) which concentrates among the youth as 80 percent of the unemployed were under 30-year old with no previous work experience (Harb 2006). This situation encouraged the government to establish the General Commission for the National Project of Fighting Unemployment to combat unemployment. This commission is linked with the Ministry of Planning. This commission was later dissolved and a new commission called the Commission of Employment and Project Development was established in 2016 that is linked to the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour. This commission was later dissolved in 2016 with the establishment of the Small and Medium Enterprises Development Commission (SMEDC) that is linked to the Ministry of Economics and Foreign Trade (Sirop 2018).

Alasadi and Abdelrahim (2008) examine the performance of Syrian SMEs before the war. They find that the primary source of capital for Syrian SMEs is personal savings and this overreliance on personal savings could be attributed to limited financial sources. Such overdependence on personal savings means that those SMEs have fewer financial obligations particularly in crisis times, but it also means that they have limited capacities and grow slowly.

The Syrian SMEs working in the software industry have long suffered from the Syria’s limited domestic market (Ibeh and Kasem 2010). However, their number increases during the war due to offshore services capitalizing on their relatively cheap labour, high revenues and no-governmental control on IT exports. Their contributions to Syria’s national exports are uncounted because they do not usually declare their sales.

A report prepared by IFC (2008) on evaluating the microfinance market in Syria indicates that there is a gap between credit supply and demand for micro and small businesses as only 15 percent of these businesses succeed in obtaining loans. In addition, a survey conducted on 50 Syrian SMEs indicated that obtaining funds is the main obstacle that face SMEs with 76.6 percent of SMEs struggled to obtain funds (Sirop 2018).

Osman (2020) examined the Syrian microfinance market in Syria pre and post-conflict. He pointed out that there were 4 main microfinance companies specialized in offering funds to SMEs. One of the most important companies was the European Investment Bank which was active in supporting microfinance institutions in addition to SMEs before the Syrian war when it halted all its operations. The three other institutions which remain active during the war period were Agha Khan Microfinance, the National Institution for Microfinance (Al Watanya), and Ibdaa Bank Syria for Microfinance.

The issue of presidential decree No.8 in 2021 permits the establishment of Microfinance banks to further support SMEs and empower them with extra funding. Agha Khan Microfinance and Al Watanya became banks and one additional bank, Banque Bemo Saudi Fransi Microfinance has established on the basis of these decree. However, despite the five-year exemptions of these banks from taxes and many other fees, their interest on loans offered to SMEs reach 18% with a maximum of 5 years. Although the Loan Risk Guarantee Company (LRGC) was established in 2016, it only started guarantee loans in 2022 due to bureaucracy and other complications. This left Syrian SMEs stranded and put further constraints on their funding. The share of the SME loans as proportion from total loans and facilities represents only 4% compared to 8% in Arab countries and 18% in middle-income countries. Bank loans cover 8% of the financial needs of Syrian SMEs sector until 2020 (SMEDC 2022).

Figure 1 depicts the ecosystem of SMEs in Syria.

3. Theoretical Background

A number of theories can be used to explain the survival and resilience of SMEs during the pandemic. The theory of business survival argues that small firms will survive as long as they have a positive net profit (Allchin 1950). However, this theory fails to accommodate the pandemic conditions when net profit turns negative and businesses are closed. Hence. Assefa and Yadavilli (2020) propose a new small firm survival theory that addresses the situations where profit becomes negative. According to this new theory, small businesses survive the pandemic as long as the ratio of cash reserves to fixed costs is greater than one.

The institutional theory provides a framework for firms’ access to finance. It argues that firms’ access to finance is governed by the rule, regulations, and institutions at which the firm subject to (Sherer et al. 2016; March and Olsen 1984; Dimaggio and Powell 1983). In particular, the coercive institutional isomorphism argues that external organisations exert formal and informal pressures on SMEs and limit their access to finance.

Regarding SMEs resilience, two theories are advanced to explain SME resilience during the pandemic: Contingency Theory (CT) and Resource-Based Theory (RBT). According to contingency theory, there is no best way to run a firm and take decisions. Instead, a firm should align its resources and strategies contingent on the internal and external situation (Lawrence and Lorsch 1999). However, resource-based theory argues that firms adapt to difficult situations through using resources and capabilities (Barney 2001; Ali et al. 2018).

To thoroughly cover the relevant literature of the article, we will design the literature review around three main topics. The first topic is related to the challenges that face SMEs during crisis times and particularly during the pandemic. However, the second and third topics are related to the adaptation strategies deployed by SMEs to counteract the pandemic adversities and the intervention measures advanced by the governments to alleviate the crisis consequences.

3.1. Challenges facing SMEs during crisis times

The literature on crisis management identifies disturbed structures, routines, and capabilities as three channels at which turbulences affect business (Williams et al. 2017). Basel II states that operational risk arises from processes, systems, people, and external factors (Girling 2022). However, many businesses fail to recognize threats such external shocks entail and thus are slow to adapt to new conditions (Munoz et al. 2019).

SMEs are characterized with lower resources and lack of established business models which make them vulnerable to internal and external shocks (Eggers 2020). The prior evidence from natural disasters, such as hurricane Katrina, shows that small businesses are financially vulnerable to interrupted cash flows and limited access to funds for recovery as well as critical infrastructure problems (Runyan 2006). Sultan and Sultan (2020) find that Covid-19 negatively affects the production and turnover of Palestinian women MSMEs.

Bourletidis and Triantafyllopoulos (2014) review the evidence on the situation of SMEs during crisis and argue that SMEs suffer disproportionally during crisis. Most SMEs suffer from a decrease in demand (Papaoikonomou et al. 2012) and tightened credit conditions (OECD 2009) during crisis time especially that they have limited financial resources and depend on bank loans (Mulhern 1996; Domac and Ferri 1999; Ozar et al. 2008). In addition, SMEs tend to be over-dependent on limited number of customers and suppliers (Nugent and Yhee 2002) and markets (Butler and Sullivan 2005; Narjoko and Hill 2007; OECD 2009) which make it harder for them to maintain their businesses during crisis.

3.2. Financing the SMEs

There is also a growing body of literature on how the pandemic affects the financial positions of SMEs. Fairlie and Fossen (2022) and Bloom et al. (2021) presented that businesses suffer significant declines in sales around the pandemic outbreak, with SMEs being disproportionately affected by the outbreak. Bartick et al. (2020) find that 43% of US small businesses were temporarily closed due to the pandemic with a huge decline in employment. Didier et al. (2021) stated that the economic downturn triggered by the pandemic and its consequences are drastically different from previous crises.

SMEs are generally perceived by banks as risky lenders and are reluctant to offer them loans particularly during crisis where their riskiness are considered even higher Piette and Zachary (2015). Lee et al. (2015) argue that credit conditions become tighter to innovative SMEs during crisis times compared to their non-innovative counterparts.

Gourinchas et al. (2021) argued that credit contraction poses a significant risk to SMEs, and it would disproportionately impact firms that could survive COVID-19 in 2020 without any fiscal support. On the other hand, focusing on the COVID-19 policy response in Germany, Dorr et al. (2022) revealed that government interventions helped to postpone SME insolvencies that is particularly pronounced among financially weak and small firms. Kaya (2022) illustrated that SME insolvency risk increased in the Euro area by around 28% during the pandemic.

3.3. SMEs Adaptation Strategies

The smallness and newness of SMEs represent an opportunity as they seem more flexible and adaptive to new conditions (Durst et al. 2021; Branicki et al. 2018; Bourletidis and Triantafyllopoulos 2014) as they are less exposed to sunk costs (Tan and See 1997) and can quickly exploit market niches (Hodorogel 2009) and less dependent on bank credit (Ter Wengel and Rodriguez, 2006). SMEs develop alternative marketing strategies and innovative tactics to crisis adversity conditions (Briozzo and Cardone-Riportella 2016; Gregory et al. 2002). Market segmentation is one of the tactics that SMEs use to adapt to crisis conditions (Shama, 1993).

Hong et al. (2012) argue that SMEs show resilient market response to crisis conditions despite their resource constraints and relatively weak market positions. Bourletidis and Triantafyllopoulos (2014) highlight five adaptation strategies that Greek SMEs use during crisis such as product reengineering process, enrich products to accommodate new habits, price fixing, stock procurement, and strengthen connections with stakeholders. D'Amato (2020) finds that SMEs significantly reduced their debt, especially their short-term loans, relative to pre-crisis period.

The emergence of new technologies brings together both opportunities and threats to SMEs (Roy et al. 2018). On the one hand, once new technologies and processes become more pervasive, they disturb older technologies and business models. If SMEs manage to quickly adapt to these changes and improve their processes, they will survive and prosper or otherwise witness a decline in their business and face the risk of closure and bankruptcy.

Digital transformation is a difficult decision any business may take but it becomes particularly challenging during a crisis (Khurana et al. 2022). One of the main emerging trends during the pandemic was that many SMEs went online to solve the problem of reduced demand and to create opportunities. Sultan and Sultan (2020) argue that Palestinian women MSMEs use social media to promote their products and compensate for the lost sales due to the pandemic. Engidaw (2022) argues that the internet provides a lifeline for many SMEs and helped them stay alive during the pandemic.

3.4. Government Intervention measures

Government around the world released massive stimulus packages to combat the adversity Covid-19 causes to economy in general and to SMEs in particular. Gourinchas et al. (2020) studied the government intervention measures and potential SME failures during the COVID-19 crisis in seventeen countries and showed that around 9% SME failures are prevented with government interventions.

The UK government, for example, has introduced the coronavirus business loan scheme to help SMEs access loans and funds up to five million pounds (Fatouh et al. 2021). In this program, the UK government guarantees 80% of the loan and pays interest and any fees for the first 12 months.

Kuckertz et al. (2022) analyze the policy measures called for or implemented in 40 countries to support SMEs and startup during Covid-19 crisis. They find that 63.41% of the countries have announced policy measures to specifically meet the needs of SMEs. They indicate that these measures range from low-interest loans, cut in interest rates, payment delays, tax relief, wage subsidies, training programs, and direct payments among others.

4. Materials and Methods

Our research methodology consisted of two stages. In the first stage, we identify stakeholders involved in the SMEs ecosystem in Syria. Then, we contacted each stakeholder to nominate a person to communicate and hold an interview with regarding our research topic. The vast majority of stakeholders nominate the director or the vice-director for the interview while others nominate the public relations directors. Interviewing high-ranking officials had the nature of an expert panel because they were themselves responsible for implementing the governmental interventions and they engage directly with SMEs.

Regarding SMEs, LRGC provided us with a database of SMEs that have contacted LRGC for funding, whether granted or not, and we arbitrarily contacted them for interviews in such a way to ensure diversity in terms of the type of activities (agriculture, food processing, etc.) they carry and the region they are working in. The 9 representative who replied come from various SMEs sectors: two from food preparation sector while the other seven belong to diversified sectors. Those SMEs also cover the whole country: two from each of Homs. Tartos, Lattakiah, Damascus countryside and one from Dier Alzour.

The second stage was the implementation of the interviews. The interviews were conducted in the form of face-to-face interviews or telephone conversation. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 stakeholders playing different roles in the Syrian SMEs ecosystem (i.e., SMEs managers, resource providers, and connectors, see Kuckertz et al. 2020; Brown and Mason 2017). Saunders et al. (2009) argue that this type of interviews is suitable when the planned study contains an exploratory element, which is the case of this study. Interviews are held in Arabic which were then translated into English and translated back into Arabic to double check their accuracy. Appendix A illustrates the number, role, sector, and province of each participant.

The aim of the interviews is to gain insights into the adversity SMEs face during the pandemic and how they cope with the pandemic adversities, and enable establish a correct analysis of policy measures. The following questions were asked;

What were the challenges that your SME face during the pandemic? Were their any opportunities that emerge from the pandemic?

How did you cope with adversities that caused by the pandemic? Have you developed any new strategies, products, and/or processes?

Did the government play any role to counteract the pandemic adversities? And how do you evaluate these intervention measures?

5. Results and Discussions

In order to uncover the challenges that are facing SMEs during Covid-19 and their adaptation methods as well as the governmental intervention to reduce the impact of the pandemic on SMEs, a detailed description of Syrian SMEs responses to these issues is listed below. The names of respondents in the quotations are face for privacy reasons.

5.1. Financing challenges

They represent a set of challenges that are related to securing funds from different sources to keep the SME alive and fund SMEs’ projects and activities. Sirop (2018) argues that Syrian public and private banks are reluctant to give loans to SMEs due to their high credit risk and because they are unable to provide the collateral large borrowers usually provide. For example, one of the requirements to offer SMEs loans is that the beneficiary should contribute 50% of the investment costs while banks offer the remaining in loans and this is difficult for SMEs. In the other hand, Microfinance banks offer small loans (5-20 millions) with interest rates of around 18% but such loans were not enough to start a micro business.

R11, who works for the Real Estate Bank, supports Sirop (2018) claim and said:

The Real Estate Bank does not give special treatment to SMEs. They have to apply for loans like other customers. However, they can benefit from interest reductions offered by the Export & Production Support & Development Agency (EPSDA) for up to 7 percent through the Commercial Bank of Syria […].

One of the main financial challenges that face SMEs is related to the relatively high cost of loans. R1, who runs an agricultural pharmacy, stated:

I obtained a 5 million loan which I had to return 9 million. This is very expensive for me. Also, I was mandated to pay for money transfer fees for each instalment because there are no banks close to where I live. This makes the loan’s cost even higher […].

R3, who runs a restaurant, obtained a loan from Al Watanya in 2017 and repaid it in 2020. He said:

[…] I needed another loan to overcome the pandemic adversity but I know I will not be able to pay it back because of the high interest rates.

R4, who used to run a number of schools’ cafeterias, received two loans to establish and expand his business. He explained:

After the pandemic, interest rates become very high. Also, school closures because of the pandemic hit my SME very hard. I lost my capital and I had to stop my business and return to my small-town herding sheep […].

R14, who works for Al Watanya, defended the high interest rates. She said:

Al Watanya, like other banks, has high operational costs that should be covered. However, Al Watanya is lenient on collateral. It is acceptable that the borrower provides us with a reference letter from the Mayor “Muokhtar” among other proofs to receive the loan”.

R6 added another challenge that is related to the small amount of loans. He argued that such small amounts are not enough to cover his SME needs:

[…] The current ceiling of loans is not suitable to my business. I run a mill and my financial needs amount to hundreds of millions. Particularly with the devaluation of the Syrian currency, a loan of 5 million Syrian pounds is far less that what my business needs.

However, R13, who works for one of the main microfinance institutions, Ibdaa, explained that the ceilings on loans provided by banks to SMEs are set by the Central bank of Syria and depend on banks’ capital. R13 said:

[…] The Central bank of Syria puts a ceiling of 5 million Syrian Pounds on Microfinance Institutions until they increase their capital. Al Watanya can provide larger loans because their capital is larger.

R2 also criticized the long time and collaterals that are needed to obtain the loans. R2, who runs a chicken farm, elaborated:

[…]I could not get a loan for my agricultural project because the land, which I work in, is still on my father’s name who recently passed away. I do not have other collaterals.

Another challenge is related to public and private banks reluctance to provide loans to SMEs. Othman, who works for LRGC, stated:

LRGC received hundreds of phone calls everyday from SMEs asking for loans. LRGC personnel transfer them to public and private banks whom LRGC signed agreements with. Unfortunately, some of these banks are perceiving them as risky customers and they are not really cooperating with them [..].

One additional challenge is related to the very expensive energy costs. R8, who runs a food preparation business, explained:

I need cooking gas and raw materials to prepare the food. However, their prices change continuously and become very expensive […].

5.2. SMEs Adaptation Strategies

The challenges that SMEs face during and after the pandemic force them to develop certain adaptation strategies to overcome the adversities. Globally, the supply chain disruptions and the lockdown cause shortages in many items and goods (Ali et al. 2021) and resulted in sharp increase in their prices. R3 illustrated:

[…] The goods and raw material costs rocketed during the pandemic. My capital enables me to purchase quarter the goods I used to purchase before the pandemic. Also, there was a short in supply of many goods due to supply chain disruption.

He explained one of the adaptation tactics he applied. He said:

I had to keep my aye on goods’ prices and order more goods than what I really need to avoid any stoppage that may occur due to shortages in goods availability […].

In fact, this strategy is consistent with the Greek SMEs adaptation strategies of stock procurement and strengthening connections with stakeholders mentioned by Bourletidis and Triantafyllopoulos (2014). It also agrees with both theories, CT and RBT, where SMEs collaborate with suppliers and realign resources to ensure continuous supply of goods at reasonable prices.

In the same vein, R15, works for one of Social Care Association that financially support SMEs, said:

[…] One of the SMEs in the sewing sector change its production line from clothes to face masks to respond to the sharp demand for face masks. Other SMEs shift to produce disinfectants and sterilizers to accommodate market needs.

R15 elaborated that SMEs working in the food-preparation (Mouneh) sector were hit the most by the pandemic because their consumers are restaurants which were forced to close during the pandemic amid lockdown measures. They moved online to counter this adversity. He said,

[…] Those SMEs started to market their products online, particularly using Instagram. Some of these SMEs applied for loans to buy high precision camera to take pictures of their food products and upload them on the net and expanded their customers to include households. This change in market segment continues after the pandemic and becomes part of their marketing strategy.

He believed that social distancing created opportunities for some SMEs working in the delivery business too. He explained:

A few SMEs applied for loans to buy electricity bikes to deliver goods and food. Such business flourish during the pandemic. One of the SMEs has developed an application that gives customers the option to order and deliver fast foods or just to deliver them […].

One of the adaptation strategies was to precisely calculate the costs and reprice products. R7 explained:

I run a textile company that produces clothes. My business was affected by inflation and reduction in demand. I had to consult experts to measure my costs correctly and reprice my products […].

He also turns to social media to sell his products which is consistent with Engidaw (2022). He said:

Digitalization benefited my business and helped it to survive and flourish because I started marketing clothes through social media […].

R8, who runs a food-preparation business also benefited from social media platforms. She explained:

Social media contributed significantly to my business success. I use social media to market my food products […].

However, R9, who works in the same sector, believes that social media marketing was not so fruitful to her business. She said:

[…] I participated in a number of exhibitions organized by SMEDC to present and sale SMEs’ products. They were more rewarding and resulted in more sales than social media platforms. The only problem with these exhibitions is that they are mainly organized during summer. I think they should be available all around the year to insure continuous sales of SMEs products.

R8, on the contrary, is unhappy with these exhibitions. She elaborated:

The transportation costs are very high to participate in these exhibitions. I prefer social media […].

5.3. Government Intervention measures

The Money and Lending Council issued the rule 25 in 26 March 2020 that allows banks to postpone all due payments on borrowers who have been affected by Covid-19. It also permitted banks to maintain the credit rating of those customers and give them an extra 90 days to pay their due payments without charging them fines or additional interests. A presidential decree was issued in 31 May 2020 that extended all official deadlines to pay taxes. However, The Central bank of Syria issued a rule in 15 June 2020 that required banks to stop giving any type of loans in order to reduce banks’ risks of banks and allowed the rescheduling of already granted loans for two years (Mouselli and Mohialdeen 2021).

One of the government interventions to support SMEs during Covid-19 outbreak was interest subsidy program where SMEs were granted loans with a simple interest of only 4% interest. This program was initiated in July 2021 and has identified certain businesses, including SMEs, as potential beneficiaries such as those working in producing the components of alternative energies, dairy products, textile industries, electricity and electronic industries among others.

R12, who works for SMEDC, clarified that the main beneficiaries of the interest subsidy program were large businesses. He said:

[…] Large businesses have more chance to be subsidized by the program. Only 40 to 50 SMEs benefited from this program. Large businesses have no problem providing collaterals and therefore they are treated preferably.

In order to resolve the funding problems that face the SMEs sector, the government has issued a legislation to establish LRGC to empower SMEs by providing guarantees to loans offered to SMEs for up to 75 percent of the loan value. However, this company remains dysfunctional until Sep 2022 when it started signing agreements with private and public banks to guarantee loans offered to SMEs by these banks. However, the reluctance of public and private banks to offer SMEs loans minimizes the expected benefits from LRGC.

R10, who works for the LRGC, explained:

[…] Since Sep 2022, LRGC has guaranteed 18 loans to SMEs with a total loan value of 3 billion Syrian pounds and a guaranteed value of 800 million. LRGC charges 1.5 percent of the guaranteed value and it is up to the bank to bear this charge or to transfer it to the borrower. LRGC refer SMEs to banks but they seem reluctant to give loans.

R5, who runs a repair shop, said:

The government role during the pandemic was mainly distributing face masks and disinfectants. No other direct intervention was noticed […].

6. Conclusions

Syria is one of the lowest income countries that have been struggling with the war consequences of high inflation and energy shortages as well as conflicting developmental priorities because of limited financial resources, weak institutional capacity and poor policies (Nabukalu et al. 2020). We find that the Syrian authorities performs reasonably well in terms of encouraging SMEs but strict loan conditions fail to create the suitable environment for these SMEs to scale and flourish and to succeed and sustain growth.

Our results indicate that Syrian SMEs were financially fragile and deeply affected by the pandemic. Moreover, we find that SMEs, which adapt digital solutions, were more resilient and were less likely to default than their noninnovative counterparts. Furthermore, innovative SMEs did not face issues finding customers during the pandemic. More importantly, SMEs continued to struggle securing funds from the banking sector and saw their access to funds actually decline during the pandemic. Put differently, banks declined credit to SMEs during this period because they were afraid from the impact of defaults on their balance sheets.

The main takeaway from our study is that the pandemic creates opportunities to innovative SMEs even in these turbulent times. Although the majority of SMEs experienced a decline in demand and sales, some SMEs experienced increased demand and sales, especially those related to health and hygiene products. We find that many Syrian SMEs which demonstrated flexibility in their business models were successful in turning crisis-induced diversity into opportunities.

We argue that certain policy measures should be implemented to mitigate SMEs' liquidity shortages and to promote innovation to avoid unnecessary insolvencies. First of all, the Central Bank of Syria should encourage public and private banks to give larger and cheaper loans to SMEs. Second, more emphasis should be directed towards long-term measures and consistent policies that focus on innovative responses, particularly those based on digital marketing, and train SMEs on issues related to crisis management and preparing business continuity plans. Third, there is an immense need to establish venture capital firms to provide seed capital especially to innovative SMEs that show expansion potential. Fifth, SMEDC should organize bazars and exhibitions around the year to help SMEs gain easy access to markets and cover or reimburse the transportation costs of SMEs. Finally, more efforts should be directed towards SMEs with great potential for growth and particularly in niche sectors such as knowledge-based sector. However, this is not an easy task given that Syrian market frictions depend heavily on the dynamics of conflict and how the conflict ended (Alnafrah and Mouselli 2020).

Future research may evaluate the effectiveness of different policy measures undertaken during the pandemic on SMEs and differentiate between sectors. Our study is based on interviews conducted with people who represent the Syrian ecosystem for SMEs. We recommend that future studies use different methodologies, such as questionnaires, to gain further insights into the challenges that face SMEs during the pandemic. It will also be important to follow up on the best practices and success stories of SMEs that cope with crisis to transfer this experience to other SMEs and make them better prepare for future comparable events. This may constitute an important venue for future research.

Appendix A. Summary of Participants Characteristics

| Name |

Role |

Business |

Size (No. of workers) |

Province |

| R1 |

SME |

Agricultural Pharmacy |

7 |

Homs |

| R2 |

SME |

Chicken farm |

15 |

Homs |

| R3 |

SME |

Supermarket |

8 |

Damascus Coutryside |

| R4 |

SME |

Schools’ Cafeteria |

6 |

Lattakiah |

| R5 |

SME |

Repair Shop |

6 |

Tartos |

| R6 |

SME |

Mill |

25 |

Deir Alzour |

| R7 |

SME |

Textile company |

20 |

Lattakiah |

| R8 |

SME |

Food preparation |

8 |

Damascus Countryside |

| R9 |

SME |

Food preparation |

10 |

Tartos |

| R10 |

Loan Guarantee Company |

LRGC |

|

Damascus |

| R11 |

Government Bank |

Real Estate Bank |

|

Damascus |

| R12 |

Governmental Agency |

SMEDC |

|

Damascus |

| R13 |

Microfinance Bank |

Ibdaa Bnak |

|

Damascus |

| R14 |

Microfinance Bank |

Al Watanya |

|

Damascus |

| R15 |

NGO |

Social Care Association |

|

Hama |

References

- Alasadi, R.; Abdelrahim, A. Analysis of small business performance in Syria. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues 2008. 1(1), pp.50-62. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Suleiman, N.; Khalid, N.; Tan, K.H.; Tseng, M.L.; Kumar, M. Supply chain resilience reactive strategies for food SMEs in coping to COVID-19 crisis. Trends in food science & technology 2021, 109, pp.94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Nagalingam, S.; Gurd, B. A resilience model for cold chain logistics of perishable products. International Journal of Logistics Management 2018, 29, pp.922–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ahdab, S. A cross-sectional survey of knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) towards COVID-19 pandemic among the Syrian residents. BMC Public Health 2021, 21: 296. [CrossRef]

- Allchin, A. A. Uncertainty evolution and economic theory: Journal of Political Economy 1950, 58, 211-221. [CrossRef]

- Alnafrah, I. and Mouselli, S. Constructing the reconstruction process: a smooth transition towards knowledge society and economy in post-conflict Syria. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 2020, 11(3), pp.931-948. [CrossRef]

- Assefa, M.; Yadavilli, J. Financial supporting mode for small businesses to coup with COVID-19 lockdown restrictions. Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research 2020, 7(10).

- Barney, J. B. Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. Journal of Management 2001, 27, pp.643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branicki, L.; Sullivan-Taylor, B.; and Livschitz, R. How entrepreneurial resilience generates resilient SMEs, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research 2018, Vol. 24 No. 7, pp. 1244-1263.

- Bartik, A. W.; Bertrand, M.; Cullen, Z. B.; Glaeser, E. L.; Luca, M.; Stanton, C. T. How are small businesses adjusting to COVID-19? Early Evidence from a Survey. NBER Working Paper 2020. No. w26989.

- Bloom, N.; Fletcher, R.; Yeh, E. The Impact of COVID-19 on US Firms. NBER Working Paper 2021. No.28314.

- Briozzo, A.; Cardone-Riportella, C. Spanish SMEs’ subsidized and guaranteed credit during economic crisis: A regional perspective. Regional Studies 2016, 50(3), pp.496–512. [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.; Sullivan, J. Crisis response tactics: US SMEs’ responses to the Asian financial crisis. Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship 2005, 17(2), pp.56-69.

- Brown, R.; Mason, C. , Looking inside the spiky bits: a critical review and conceptualisation of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small business economics 2017, 49(1), pp.11-30. [CrossRef]

- Bourletidis, K.; Triantafyllopoulos, Y. SMEs survival in time of crisis: strategies, tactics and commercial success stories. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2014, 148, pp.639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didier, T.; Huneeus, F.; Larrain, M.; Schmukler, S.L. Financing firms in hibernation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Financial Stability 2021, 53, p100837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimaggio, P. J.; Powell, W. W. The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review 1983, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domac¸, I.; Ferri, G. Did the East Asian crisis disproportionately hit small business in Korea?, Economic Notes 1999, 28(3), 403–429.

- D’Amato, A. Capital structure, debt maturity, and financial crisis: empirical evidence from SMEs. Small Business Economics 2020, 55(4), pp.919-941. [CrossRef]

- Dörr, J.O.; Licht, G.; Murmann, S. Small firms and the COVID-19 insolvency gap. Small Business Economics 2022, 58(2), pp.887-917. [CrossRef]

- Durst, S.; Palacios Acuache, M.M.G.; and Bruns, G. Peruvian small and medium-sized enterprises and COVID-19: Time for a new start!, Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 2021, Vol. 13 No. 4, pp. 648-672. [CrossRef]

- Engidaw, A.E. Small businesses and their challenges during COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries: in the case of Ethiopia. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2022, 11, pp.1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatouh, M.; Giansante, S.; Ongena, S. Economic support during the COVID crisis. Quantitative easing and lending support schemes in the UK. Economics Letters 2021, 209, p110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairlie, R.; Fossen, F.M. The early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on business sales. Small Business Economics 2022, 58(4), pp.1853-1864. [CrossRef]

- Girling. P,. Operational Risk Management A Complete Guide for Banking and Fintech, Wiley Finance Series, 2nd Edition, 2022, pp.312-314.

- Gourinchas, P.O.; Kalemli-Özcan, Ş.; Penciakova, V.; Sander, N. COVID-19 and Small-and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A 2021" Time Bomb"?. In AEA Papers and Proceedings, 2021, Vol. 111, pp. 282-286.

- Gourinchas, P.O.; Kalemli-Ozcan, S.; Penciakova, V.; Sander, N. COVID-19 and SME Failures. NBER Working Paper 2020, Working Paper No.27877. [CrossRef]

- Gregory, G.; Harvie, C.; Lee, H. Korean SMEs in the wake of the financial crisis: Strategies, constraints and performance in a global economy, 2002, mimeo, University of Wollongong.

- Hodorogel, R. The Economic Crisis and its Effects on SMEs. Theoretical and Applied Economics 2009, 05(534),pp.79-88.

- Ibeh, K.; Kasem, L. The network perspective and the internationalization of small and medium sized software firms from Syria. Industrial Marketing Management 2011, 40(3), pp.358-367. [CrossRef]

- Khurana, I.; Dutta, D. K.; Ghura, A., S. SMEs and digital transformation during a crisis: The emergence of resilience as a second-order dynamic capability in an entrepreneurial ecosystem, Journal of Business Research 2022, 150, pp.623-641. [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Brändle, L.; Gaudig, A.; Hinderer, S.; Reyes, C.A.M.; Prochotta, A.; Steinbrink, K.M.; Berger, E.S. Startups in times of crisis–A rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 2020, 13, pe00169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, O. Determinants and consequences of SME insolvency risk during the pandemic, Economic Modelling 2022, 115, pp.1-14. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P. R.; Lorsch, J. W. Organization and environment: Managing differentiation and integration. Boston: Harvard Business School Press 1999.

- March, J. G. and Olsen, J. P. The new institutionalism: Organizational factors in political life. The American Political Science Review 1984, 78(3), 734-749. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health 2022, Ministry of Health website accessed in 22 Dec 2022.

- Mouselli, S.; Mohialdeen, R. The Impact of Corona Pandemic on the Volatility of Damascus Securities Exchange Index, Journal of Hama University 2021, 4(17), pp.1-16.

- Muñoz, P.; Kimmitt, J.; Kibler, E.; Farny, S. Living on the slopes: entrepreneurial preparedness in a context under continuous threat. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 2019, 31(5-6), pp.413-434. [CrossRef]

- Mulhern, A. Venezuelan small businesses and the economic crisis: Reflections from Europe. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 1996, 2(2),pp.69–81. [CrossRef]

- Nugent, J.; Yhee, S. Small and medium enterprises in Korea: Achievements, constraints and policy issues. Small Business Economics 2002, 18, pp.85–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narjoko, D.; Hill, H. Winners and losers during a deep economic crisis: Firm-level evidence from Indonesian manufacturing. Asian Economic Journal 2007, 21(4),pp.343–368. [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The impact of the global crisis on SME and entrepreneurship financing and policy responses 2009 [online]. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/40/34/43183090.pdf.

- Osman, O.S. The role of microfinance post trauma: the case of Syria. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 2021, 11(3), pp.276-290. [CrossRef]

- Ozar, S.; Ozertan, G.; Irfanoglu, Z. Micro and small enterprise growth in Turkey: Under the shadow of financial crisis. The Developing Economies 2008, 46(4), pp.331–362. [CrossRef]

- Papaoikonomou, E.; Segarra, P.; Li, X. Entrepreneurship in the Context of Crisis: Identifying Barriers and Proposing Strategies. International Advances in Economic Research 2012, 18(1), pp.111-119. [CrossRef]

- Runyan, R.C. Small business in the face of crisis: identifying barriers to recovery from a natural disaster 1. Journal of Contingencies and crisis management 2006, 14(1), pp.12-26. [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.N.K. , Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students 2009, 5th ed., Harlow, Pearson.

- Shama, A. Marketing strategies during recession: a comparison of small and large firms. Journal of Small Business Management 1993, 31(3), pp.62–72.

- Sherer, S. A.; Meyerhoefer, C. D.; Peng, L. Applying institutional theory to the adoption of electronic health records in the U.S. Information & Management 2016, 53(5), 570-580. [CrossRef]

- Sirop, R. SMEs in Syria – Financing or Organizational problem, Damascus Center for Research and Studies (MADAD) 2018, Damascus, Syria.

- Sultan, S. and Sultan, W.I.M. Women MSMEs in times of crisis: challenges and opportunities, Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 2020, Vol. 27 No. 7, pp. 1069-1083. [CrossRef]

- Surya, S. Business Disruptions, Financial Fragility and Resilience Strategy: Exploration of Impact of The Covid-19 on Micro, Small and Medium Entreprises. Jurnal Akuntansi, Manajemen dan Ekonomi 2022, 23(3), pp. 46-55. [CrossRef]

- Ter Wengel, J.; Rodriguez, E. SME export performance in Indonesia after the crisis. Small Business Economics 2006, 26, pp.25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). Syria: An Evaluation of Microfinance Market. 2008 Washington D. C., USA.

- United Nations. The Syrian Arab Republic UN Strategic Framework 2022 – 2024, March.

- Williams, T.A.; Gruber, D.A.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Shepherd, D.A.; Zhao, E.Y. Organizational response to adversity: Fusing crisis management and resilience research streams. Academy of Management Annals 2017, 11(2), pp.733-769. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).