Submitted:

23 January 2023

Posted:

25 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

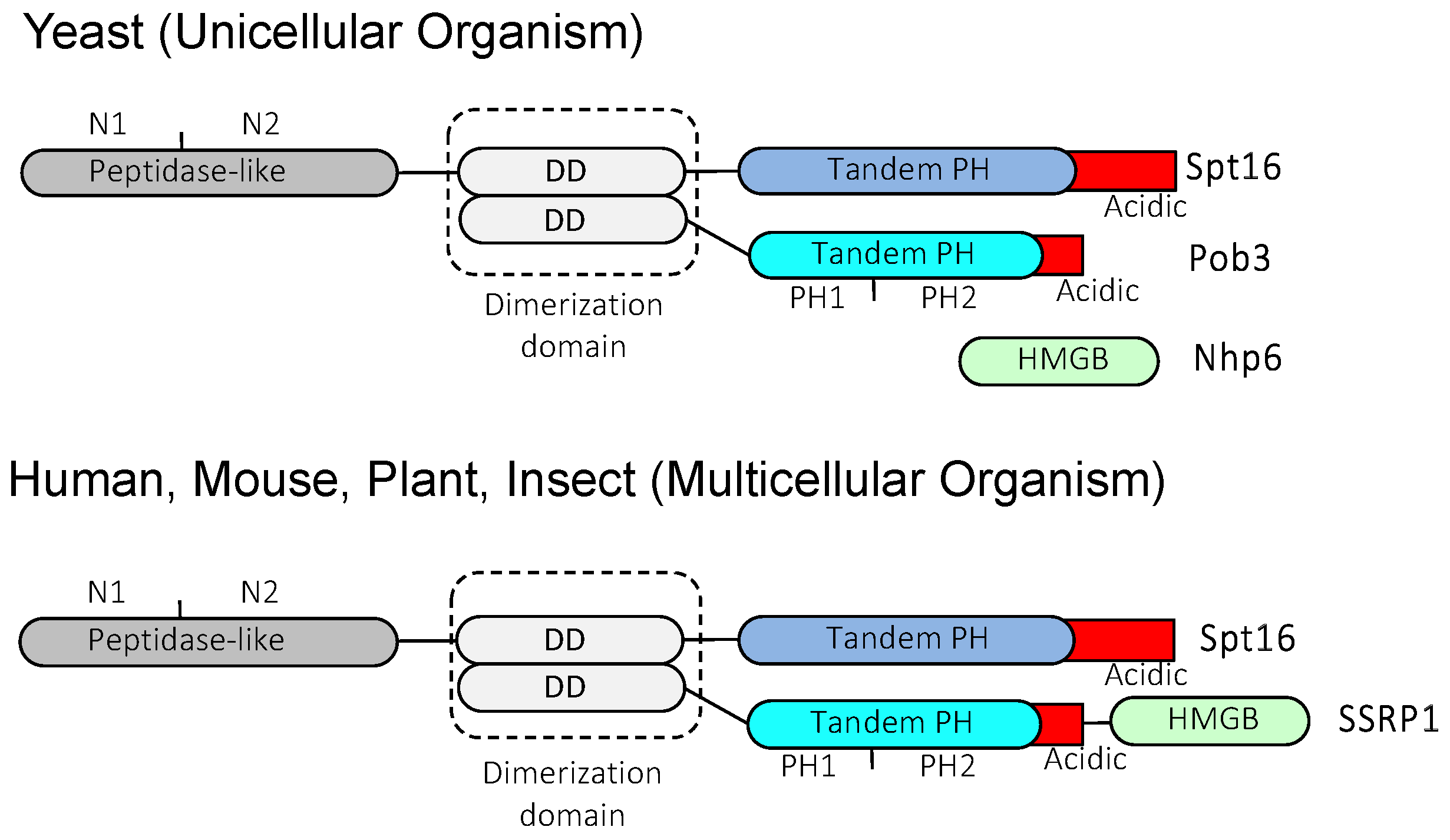

2. FACT plays a multifunctional role in transcriptional regulation

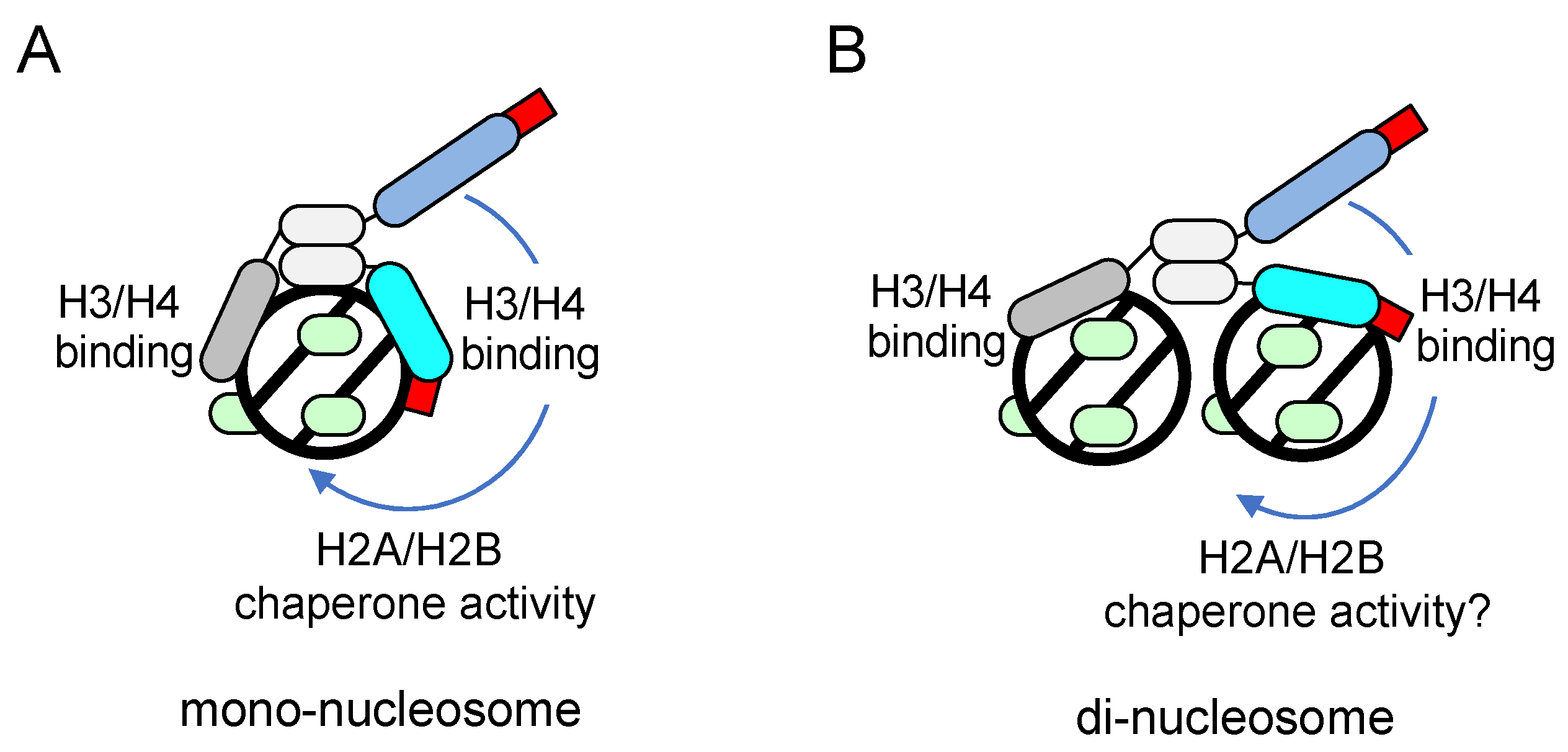

3. Working models of FACT for nucleosome dynamics

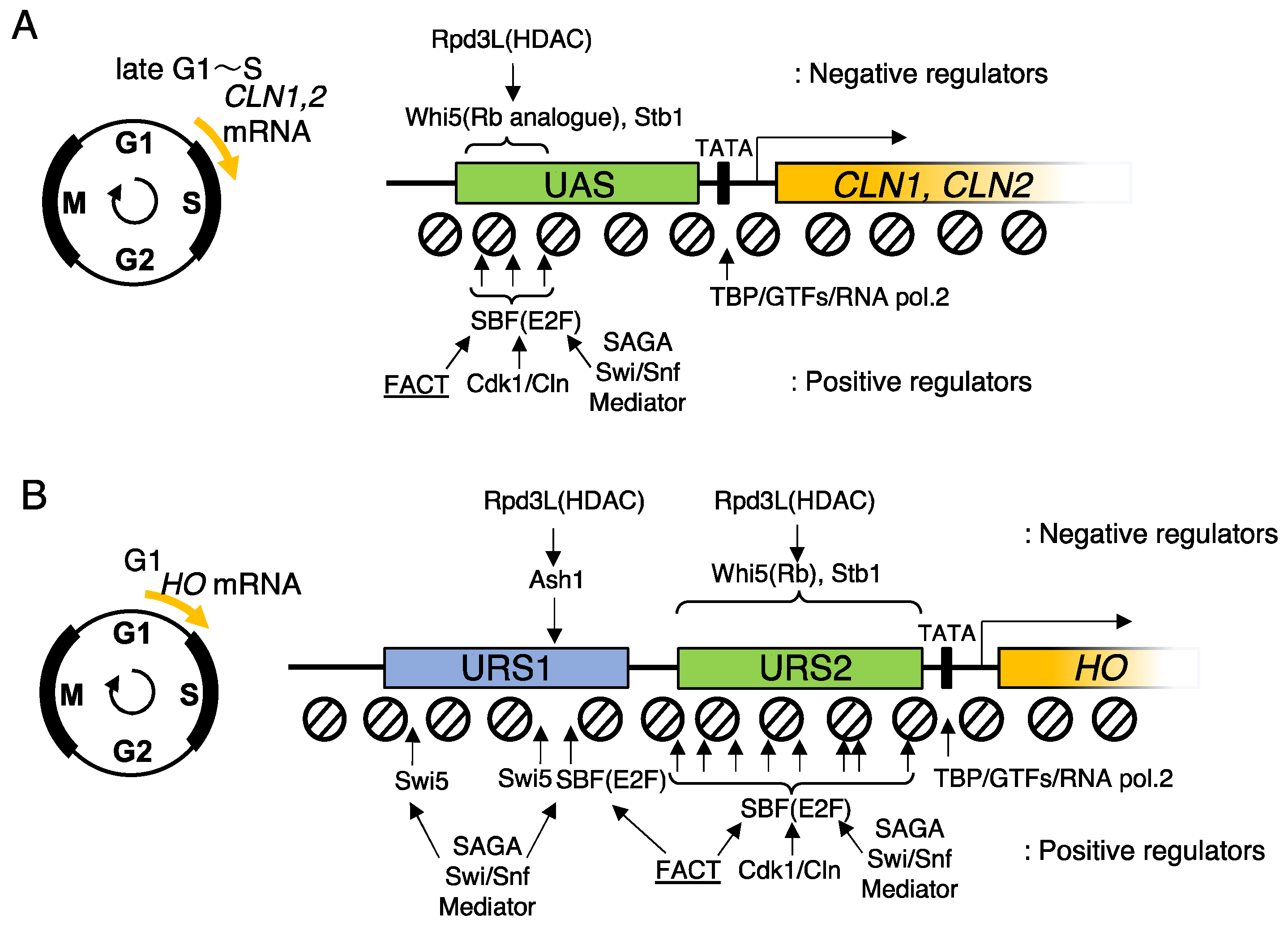

4. SBF recruits FACT for promoter chromatin activation in budding yeast

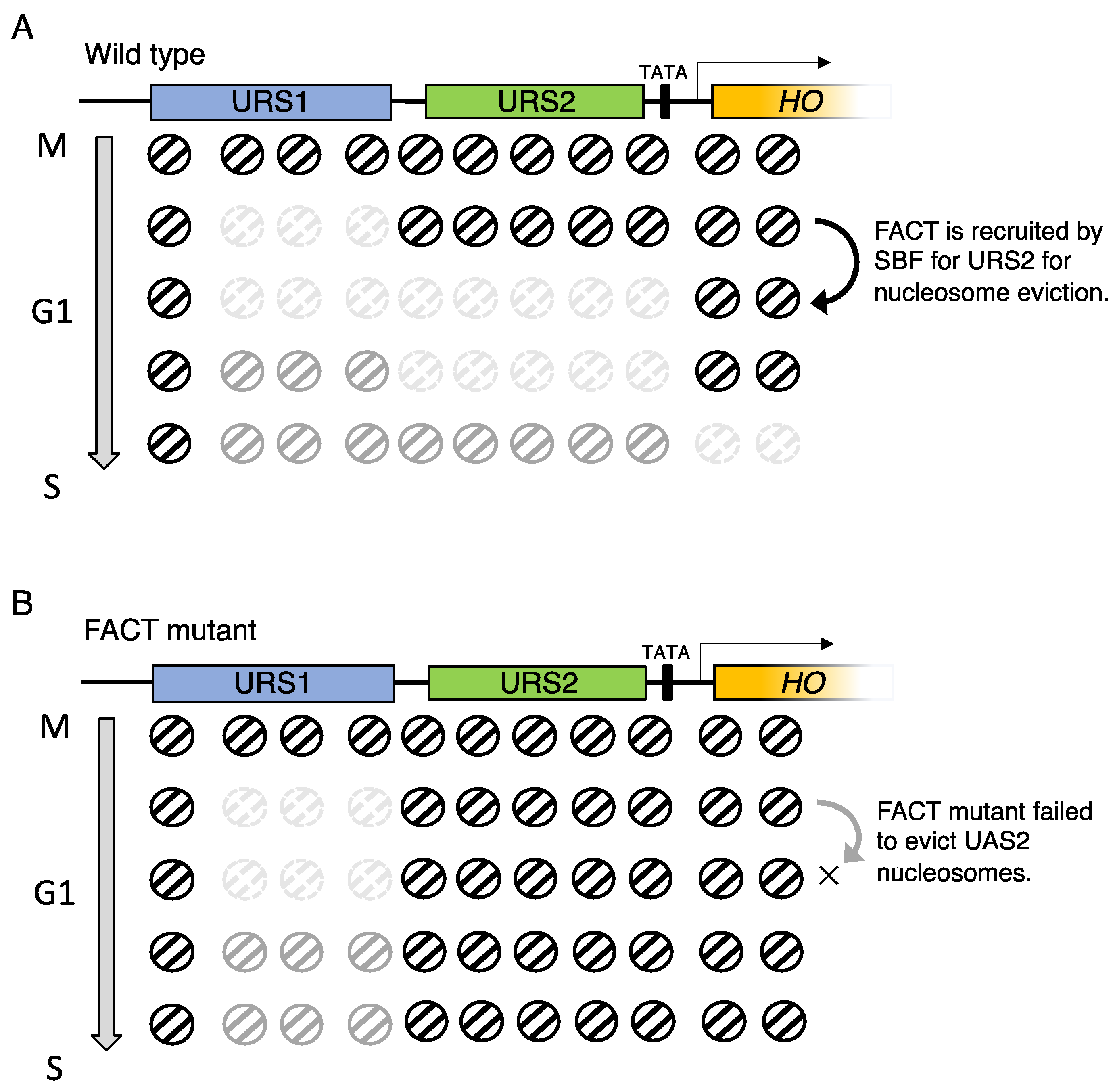

5. Wave of nucleosome eviction, and the site where FACT functions in HO promoter in budding yeast

6. FACT dependent heterochromatic silencing in fission yeast

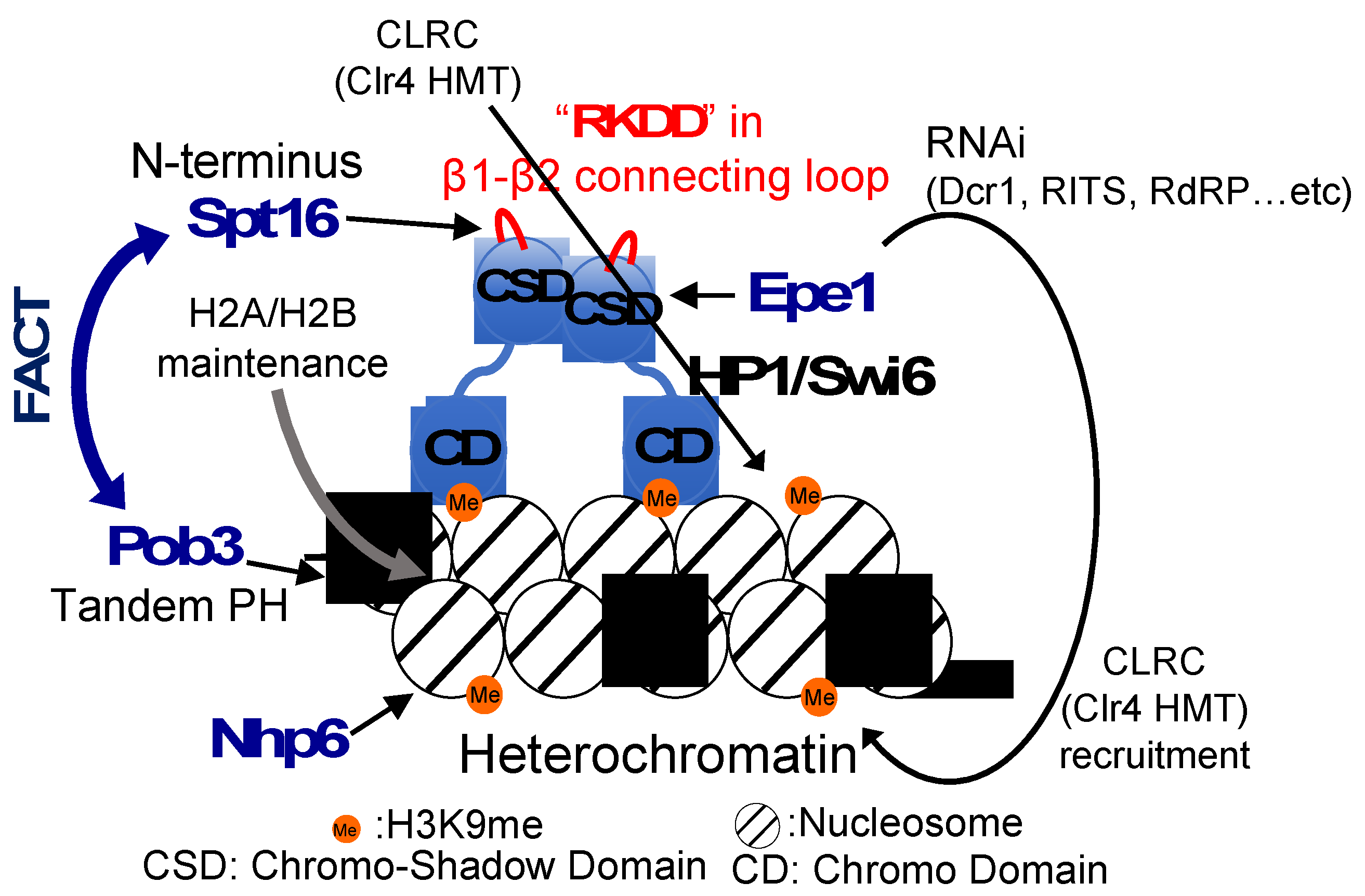

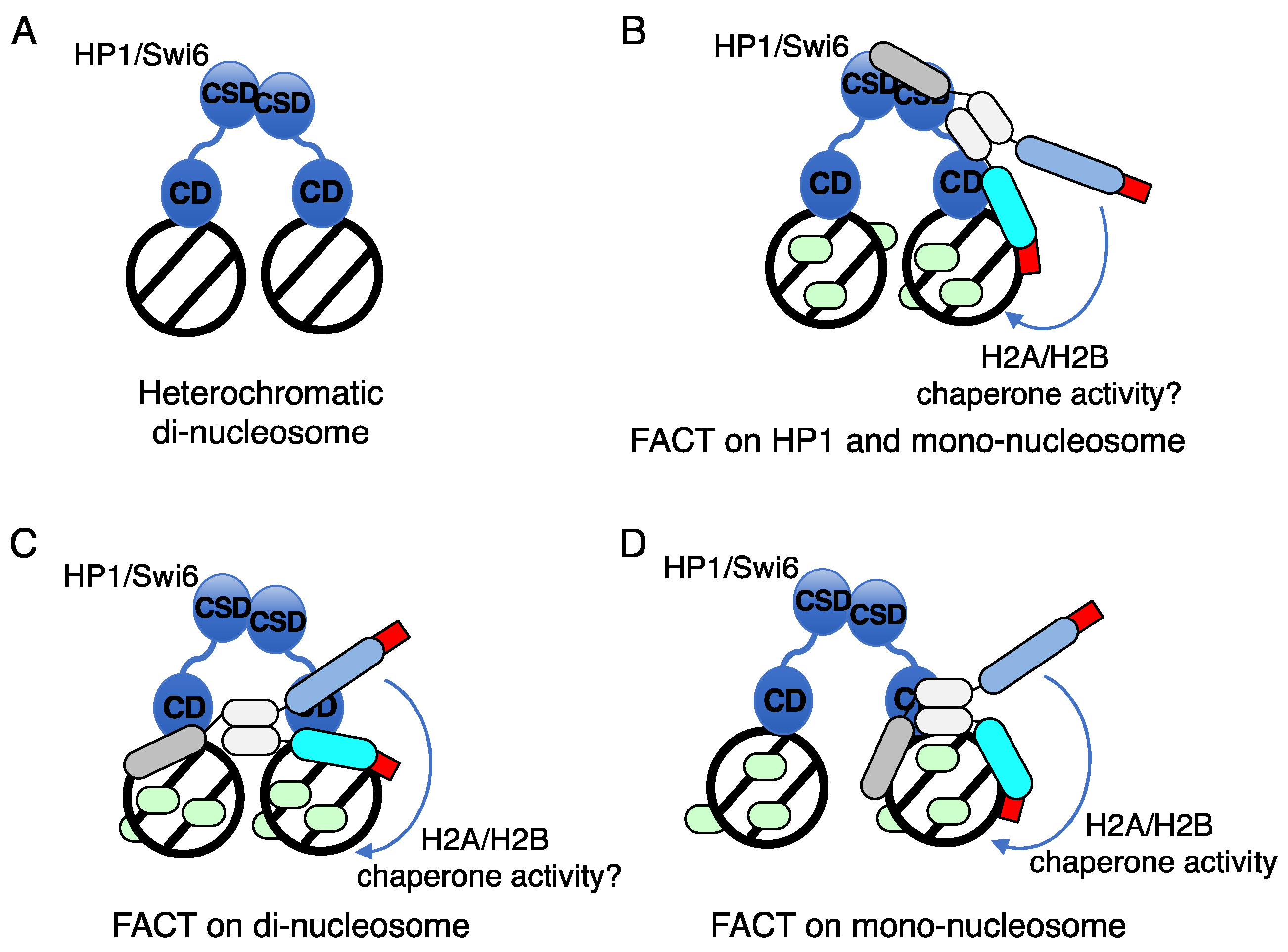

7. Mechanism of action of FACT on nucleosomes within heterochromatin for formation and maintenance of heterochromatin in fission yeast

8. Summary and Perspective

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zabidi, M.A.; Stark, A. Regulatory Enhancer-Core-Promoter Communication via Transcription Factors and Cofactors. Trends Genet 2016, 32, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, S.; Roeder, R.G. The metazoan Mediator co-activator complex as an integrative hub for transcriptional regulation. Nat Rev Genet 2010, 11, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.L.; Sen, R.; Roeder, R.G. Enhancer-promoter communication and transcriptional regulation of Igh. Trends Immunol 2011, 32, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Schilbach, S.; Ninov, M.; Urlaub, H.; Cramer, P. Structures of transcription preinitiation complex engaged with the +1 nucleosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schier, A.C.; Taatjes, D.J. Structure and mechanism of the RNA polymerase II transcription machinery. Genes Dev 2020, 34, 465–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, S. Structure and mechanism of the RNA polymerase II transcription machinery. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2004, 11, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svaren, J.; Horz, W. Transcription factors vs nucleosomes: regulation of the PHO5 promoter in yeast. Trends Biochem Sci 1997, 22, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeder, R.G. Role of general and gene-specific cofactors in the regulation of eukaryotic transcription. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 1998, 63, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.K.; Shibata, Y.; Rao, B.; Strahl, B.D.; Lieb, J.D. Evidence for nucleosome depletion at active regulatory regions genome-wide. Nat Genet 2004, 36, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Wong, Y.C.; Elgin, S.C. The chromatin structure of specific genes: II. Disruption of chromatin structure during gene activity. Cell 1979, 16, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Pugh, B.F. Nucleosome positioning and gene regulation: advances through genomics. Nat Rev Genet 2009, 10, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chereji, R.V.; Ocampo, J.; Clark, D.J. MNase-Sensitive Complexes in Yeast: Nucleosomes and Non-histone Barriers. Mol Cell 2017, 65, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Givens, R.M.; Lai, W.K.; Rizzo, J.M.; Bard, J.E.; Mieczkowski, P.A.; Leatherwood, J.; Huberman, J.A.; Buck, M.J. Chromatin architectures at fission yeast transcriptional promoters and replication origins. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, 7176–7189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantermann, A.B.; Straub, T.; Stralfors, A.; Yuan, G.C.; Ekwall, K.; Korber, P. Schizosaccharomyces pombe genome-wide nucleosome mapping reveals positioning mechanisms distinct from those of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2010, 17, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, O.; Thakur, J. Molecular Complexes at Euchromatin, Heterochromatin and Centromeric Chromatin. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, Z.; Simpson, B.; Miao, K.H.; Singh, G. Genetics, Histone Code. In StatPearls; Treasure Island (FL), 2022.

- Jenuwein, T.; Allis, C.D. Translating the histone code. Science 2001, 293, 1074–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, X. Heterochromatin structure: lessons from the budding yeast. IUBMB Life 2014, 66, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewal, S.I.; Jia, S. Heterochromatin revisited. Nat Rev Genet 2007, 8, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noma, K.; Allis, C.D.; Grewal, S.I. Transitions in distinct histone H3 methylation patterns at the heterochromatin domain boundaries. Science 2001, 293, 1150–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, J.; Rice, J.C.; Strahl, B.D.; Allis, C.D.; Grewal, S.I. Role of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in epigenetic control of heterochromatin assembly. Science 2001, 292, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.D.; Li, J.; Wong, J. Relationship between histone H3 lysine 9 methylation, transcription repression, and heterochromatin protein 1 recruitment. Mol Cell Biol 2005, 25, 2525–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutter DiPiazza, A.R.; Taneja, N.; Dhakshnamoorthy, J.; Wheeler, D.; Holla, S.; Grewal, S.I.S. Spreading and epigenetic inheritance of heterochromatin require a critical density of histone H3 lysine 9 tri-methylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, A.H.; Mermoud, J.E.; O'Carroll, D.; Pagani, M.; Schweizer, D.; Brockdorff, N.; Jenuwein, T. Histone H3 lysine 9 methylation is an epigenetic imprint of facultative heterochromatin. Nat Genet 2002, 30, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Huarte, M.; Zaratiegui, M.; Vaughn, M.W.; Shi, Y.; Martienssen, R.; Cande, W.Z. Lid2 is required for coordinating H3K4 and H3K9 methylation of heterochromatin and euchromatin. Cell 2008, 135, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeRoy, G.; Orphanides, G.; Lane, W.S.; Reinberg, D. Requirement of RSF and FACT for transcription of chromatin templates in vitro. Science 1998, 282, 1900–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orphanides, G.; LeRoy, G.; Chang, C.H.; Luse, D.S.; Reinberg, D. FACT, a factor that facilitates transcript elongation through nucleosomes. Cell 1998, 92, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orphanides, G.; Wu, W.H.; Lane, W.S.; Hampsey, M.; Reinberg, D. The chromatin-specific transcription elongation factor FACT comprises human SPT16 and SSRP1 proteins. Nature 1999, 400, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belotserkovskaya, R.; Reinberg, D. Facts about FACT and transcript elongation through chromatin. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2004, 14, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valieva, M.E.; Gerasimova, N.S.; Kudryashova, K.S.; Kozlova, A.L.; Kirpichnikov, M.P.; Hu, Q.; Botuyan, M.V.; Mer, G.; Feofanov, A.V.; Studitsky, V.M. Stabilization of Nucleosomes by Histone Tails and by FACT Revealed by spFRET Microscopy. Cancers (Basel) 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsunaka, Y.; Fujiwara, Y.; Oyama, T.; Hirose, S.; Morikawa, K. Integrated molecular mechanism directing nucleosome reorganization by human FACT. Genes Dev 2016, 30, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmeyer, J.; Formosa, T. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase alpha catalytic subunit interacts with Cdc68/Spt16 and with Pob3, a protein similar to an HMG1-like protein. Mol Cell Biol 1997, 17, 4178–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewster, N.K.; Johnston, G.C.; Singer, R.A. Characterization of the CP complex, an abundant dimer of Cdc68 and Pob3 proteins that regulates yeast transcriptional activation and chromatin repression. J Biol Chem 1998, 273, 21972–21979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittmeyer, J.; Joss, L.; Formosa, T. Spt16 and Pob3 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae form an essential, abundant heterodimer that is nuclear, chromatin-associated, and copurifies with DNA polymerase alpha. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 8961–8971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formosa, T.; Eriksson, P.; Wittmeyer, J.; Ginn, J.; Yu, Y.; Stillman, D.J. Spt16-Pob3 and the HMG protein Nhp6 combine to form the nucleosome-binding factor SPN. EMBO J 2001, 20, 3506–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowley, A.; Singer, R.A.; Johnston, G.C. CDC68, a yeast gene that affects regulation of cell proliferation and transcription, encodes a protein with a highly acidic carboxyl terminus. Mol Cell Biol 1991, 11, 5718–5726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewster, N.K.; Johnston, G.C.; Singer, R.A. A bipartite yeast SSRP1 analog comprised of Pob3 and Nhp6 proteins modulates transcription. Mol Cell Biol 2001, 21, 3491–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formosa, T. FACT and the reorganized nucleosome. Mol Biosyst 2008, 4, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costigan, C.; Kolodrubetz, D.; Snyder, M. NHP6A and NHP6B, which encode HMG1-like proteins, are candidates for downstream components of the yeast SLT2 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Mol Cell Biol 1994, 14, 2391–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.U.; Hayles, J.; Kim, D.; Wood, V.; Park, H.O.; Won, M.; Yoo, H.S.; Duhig, T.; Nam, M.; Palmer, G.; et al. Analysis of a genome-wide set of gene deletions in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat Biotechnol 2010, 28, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodrubetz, D.; Kruppa, M.; Burgum, A. Gene dosage affects the expression of the duplicated NHP6 genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 2001, 272, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zeng, S.X.; Landais, I.; Lu, H. Human SSRP1 has Spt16-dependent and -independent roles in gene transcription. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 6936–6945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zeng, F.; Liu, Y.; Shao, C.; Li, S.; Lv, H.; Shi, Y.; Niu, L.; Teng, M.; Li, X. Crystal Structure of Human SSRP1 Middle Domain Reveals a Role in DNA Binding. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 18688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruone, S.; Rhoades, A.R.; Formosa, T. Multiple Nhp6 molecules are required to recruit Spt16-Pob3 to form yFACT complexes and to reorganize nucleosomes. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 45288–45295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, L.L.; Connell, Z.; Xin, H.; Studitsky, V.M.; Feofanov, A.V.; Valieva, M.E.; Formosa, T. Functional roles of the DNA-binding HMGB domain in the histone chaperone FACT in nucleosome reorganization. J Biol Chem 2018, 293, 6121–6133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stillman, D.J. Nhp6: a small but powerful effector of chromatin structure in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010, 1799, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayanagi, K.; Saikusa, K.; Miyazaki, N.; Akashi, S.; Iwasaki, K.; Nishimura, Y.; Morikawa, K.; Tsunaka, Y. Structural visualization of key steps in nucleosome reorganization by human FACT. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 10183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Crickard, J.B.; Srikanth, A.; Reese, J.C. A highly conserved region within H2B is important for FACT to act on nucleosomes. Mol Cell Biol 2014, 34, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michl-Holzinger, P.; Obermeyer, S.; Markusch, H.; Pfab, A.; Ettner, A.; Bruckmann, A.; Babl, S.; Langst, G.; Schwartz, U.; Tvardovskiy, A.; et al. Phosphorylation of the FACT histone chaperone subunit SPT16 affects chromatin at RNA polymerase II transcriptional start sites in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, 5014–5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Keller, D.M.; Scott, J.D.; Lu, H. CK2 phosphorylates SSRP1 and inhibits its DNA-binding activity. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 11869–11875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hondele, M.; Stuwe, T.; Hassler, M.; Halbach, F.; Bowman, A.; Zhang, E.T.; Nijmeijer, B.; Kotthoff, C.; Rybin, V.; Amlacher, S.; et al. Structural basis of histone H2A-H2B recognition by the essential chaperone FACT. Nature 2013, 499, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuwe, T.; Hothorn, M.; Lejeune, E.; Rybin, V.; Bortfeld, M.; Scheffzek, K.; Ladurner, A.G. The FACT Spt16 "peptidase" domain is a histone H3-H4 binding module. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 8884–8889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, H.; Takahata, S.; Blanksma, M.; McCullough, L.; Stillman, D.J.; Formosa, T. yFACT induces global accessibility of nucleosomal DNA without H2A-H2B displacement. Mol Cell 2009, 35, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivkina, A.L.; Karlova, M.G.; Valieva, M.E.; McCullough, L.L.; Formosa, T.; Shaytan, A.K.; Feofanov, A.V.; Kirpichnikov, M.P.; Sokolova, O.S.; Studitsky, V.M. Electron microscopy analysis of ATP-independent nucleosome unfolding by FACT. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamai, A.; Puglisi, A.; Strubin, M. Histone chaperone spt16 promotes redeposition of the original h3-h4 histones evicted by elongating RNA polymerase. Mol Cell 2009, 35, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voth, W.P.; Takahata, S.; Nishikawa, J.L.; Metcalfe, B.M.; Naar, A.M.; Stillman, D.J. A role for FACT in repopulation of nucleosomes at inducible genes. PLoS One 2014, 9, e84092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidorova, J.M.; Mikesell, G.E.; Breeden, L.L. Cell cycle-regulated phosphorylation of Swi6 controls its nuclear localization. Mol Biol Cell 1995, 6, 1641–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moll, T.; Dirick, L.; Auer, H.; Bonkovsky, J.; Nasmyth, K. SWI6 is a regulatory subunit of two different cell cycle START-dependent transcription factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Sci Suppl 1992, 16, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoli, C.; Skotheim, J.M.; de Bruin, R.A. Control of cell cycle transcription during G1 and S phases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013, 14, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahata, S.; Yu, Y.; Stillman, D.J. The E2F functional analogue SBF recruits the Rpd3(L) HDAC, via Whi5 and Stb1, and the FACT chromatin reorganizer, to yeast G1 cyclin promoters. EMBO J 2009, 28, 3378–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahata, S.; Yu, Y.; Stillman, D.J. FACT and Asf1 regulate nucleosome dynamics and coactivator binding at the HO promoter. Mol Cell 2009, 34, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahata, S.; Yu, Y.; Stillman, D.J. Repressive chromatin affects factor binding at yeast HO (homothallic switching) promoter. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 34809–34819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanzo, M.; Nishikawa, J.L.; Tang, X.; Millman, J.S.; Schub, O.; Breitkreuz, K.; Dewar, D.; Rupes, I.; Andrews, B.; Tyers, M. CDK activity antagonizes Whi5, an inhibitor of G1/S transcription in yeast. Cell 2004, 117, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittenberg, C.; Reed, S.I. Cell cycle-dependent transcription in yeast: promoters, transcription factors, and transcriptomes. Oncogene 2005, 24, 2746–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirick, L.; Moll, T.; Auer, H.; Nasmyth, K. A central role for SWI6 in modulating cell cycle Start-specific transcription in yeast. Nature 1992, 357, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, M.M.; Brocca, S.; Sacco, E.; Spinelli, M.; Papaleo, E.; Lambrughi, M.; Alberghina, L.; Vanoni, M. A comparative study of Whi5 and retinoblastoma proteins: from sequence and structure analysis to intracellular networks. Front Physiol 2013, 4, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, M.V.; Smolka, M.B.; de Bruin, R.A.; Zhou, H.; Wittenberg, C.; Dowdy, S.F. Whi5 regulation by site specific CDK-phosphorylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS One 2009, 4, e4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruin, R.A.; McDonald, W.H.; Kalashnikova, T.I.; Yates, J., 3rd; Wittenberg, C. Cln3 activates G1-specific transcription via phosphorylation of the SBF bound repressor Whi5. Cell 2004, 117, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickoloff, J.A.; Chen, E.Y.; Heffron, F. A 24-base-pair DNA sequence from the MAT locus stimulates intergenic recombination in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1986, 83, 7831–7835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostriken, R.; Strathern, J.N.; Klar, A.J.; Hicks, J.B.; Heffron, F. A site-specific endonuclease essential for mating-type switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 1983, 35, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasmyth, K. Molecular analysis of a cell lineage. Nature 1983, 302, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klar, A.J.; Hicks, J.B.; Strathern, J.N. Directionality of yeast mating-type interconversion. Cell 1982, 28, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strathern, J.N.; Klar, A.J.; Hicks, J.B.; Abraham, J.A.; Ivy, J.M.; Nasmyth, K.A.; McGill, C. Homothallic switching of yeast mating type cassettes is initiated by a double-stranded cut in the MAT locus. Cell 1982, 31, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrozza, M.J.; Florens, L.; Swanson, S.K.; Shia, W.J.; Anderson, S.; Yates, J.; Washburn, M.P.; Workman, J.L. Stable incorporation of sequence specific repressors Ash1 and Ume6 into the Rpd3L complex. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005, 1731, 77–87; discussion 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardiu, M.E.; Gilmore, J.M.; Carrozza, M.J.; Li, B.; Workman, J.L.; Florens, L.; Washburn, M.P. Determining protein complex connectivity using a probabilistic deletion network derived from quantitative proteomics. PLoS One 2009, 4, e7310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohl, F.; Kruse, C.; Frank, A.; Ferring, D.; Jansen, R.P. She2p, a novel RNA-binding protein tethers ASH1 mRNA to the Myo4p myosin motor via She3p. EMBO J 2000, 19, 5514–5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darzacq, X.; Powrie, E.; Gu, W.; Singer, R.H.; Zenklusen, D. RNA asymmetric distribution and daughter/mother differentiation in yeast. Curr Opin Microbiol 2003, 6, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yarrington, R.M.; Stillman, D.J. FACT and Ash1 promote long-range and bidirectional nucleosome eviction at the HO promoter. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, 10877–10889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, H.J.; Sil, A.; Measday, V.; Yu, Y.; Moffat, J.; Maxon, M.E.; Herskowitz, I.; Andrews, B.; Stillman, D.J. The protein kinase Pho85 is required for asymmetric accumulation of the Ash1 protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol 2001, 42, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosma, M.P. Daughter-specific repression of Saccharomyces cerevisiae HO: Ash1 is the commander. EMBO Rep 2004, 5, 953–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosma, M.P.; Tanaka, T.; Nasmyth, K. Ordered recruitment of transcription and chromatin remodeling factors to a cell cycle- and developmentally regulated promoter. Cell 1999, 97, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosma, M.P.; Panizza, S.; Nasmyth, K. Cdk1 triggers association of RNA polymerase to cell cycle promoters only after recruitment of the mediator by SBF. Mol Cell 2001, 7, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stillman, D.J.; Bankier, A.T.; Seddon, A.; Groenhout, E.G.; Nasmyth, K.A. Characterization of a transcription factor involved in mother cell specific transcription of the yeast HO gene. EMBO J 1988, 7, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stillman, D.J. Dancing the cell cycle two-step: regulation of yeast G1-cell-cycle genes by chromatin structure. Trends Biochem Sci 2013, 38, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moll, T.; Tebb, G.; Surana, U.; Robitsch, H.; Nasmyth, K. The role of phosphorylation and the CDC28 protein kinase in cell cycle-regulated nuclear import of the S. cerevisiae transcription factor SWI5. Cell 1991, 66, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi, T.; Ikeda, A.; Koyama, N.; Fukada, J.; Nagao, R. A refined two-hybrid system reveals that SCF(Cdc4)-dependent degradation of Swi5 contributes to the regulatory mechanism of S-phase entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 14497–14502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohrmann, P.R.; Butler, G.; Tamai, K.; Dorland, S.; Greene, J.R.; Thiele, D.J.; Stillman, D.J. Parallel pathways of gene regulation: homologous regulators SWI5 and ACE2 differentially control transcription of HO and chitinase. Genes Dev 1992, 6, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allshire, R.C.; Madhani, H.D. Ten principles of heterochromatin formation and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018, 19, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martienssen, R.; Moazed, D. RNAi and heterochromatin assembly. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2015, 7, a019323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuguchi, T.; Barrowman, J.; Grewal, S.I. Chromosome domain architecture and dynamic organization of the fission yeast genome. FEBS Lett 2015, 589, 2975–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Yeom, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.S. The regional sequestration of heterochromatin structural proteins is critical to form and maintain silent chromatin. Epigenetics Chromatin 2022, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padeken, J.; Methot, S.P.; Gasser, S.M. Establishment of H3K9-methylated heterochromatin and its functions in tissue differentiation and maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglesias, N.; Currie, M.A.; Jih, G.; Paulo, J.A.; Siuti, N.; Kalocsay, M.; Gygi, S.P.; Moazed, D. Automethylation-induced conformational switch in Clr4 (Suv39h) maintains epigenetic stability. Nature 2018, 560, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldar, S.; Saini, A.; Nanda, J.S.; Saini, S.; Singh, J. Role of Swi6/HP1 self-association-mediated recruitment of Clr4/Suv39 in establishment and maintenance of heterochromatin in fission yeast. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 9308–9320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayne, E.H.; White, S.A.; Kagansky, A.; Bijos, D.A.; Sanchez-Pulido, L.; Hoe, K.L.; Kim, D.U.; Park, H.O.; Ponting, C.P.; Rappsilber, J.; et al. Stc1: a critical link between RNAi and chromatin modification required for heterochromatin integrity. Cell 2010, 140, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Pillai, S.S.; Taglini, F.; Li, F.; Ruan, K.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Shi, Y.; Bayne, E.H. Structural analysis of Stc1 provides insights into the coupling of RNAi and chromatin modification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013, 110, E1879–E1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoub, N.; Noma, K.; Isaac, S.; Kahan, T.; Grewal, S.I.; Cohen, A. A novel jmjC domain protein modulates heterochromatization in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol 2003, 23, 4356–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zofall, M.; Grewal, S.I. Swi6/HP1 recruits a JmjC domain protein to facilitate transcription of heterochromatic repeats. Mol Cell 2006, 22, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdel, A.; Moazed, D. RNAi-directed assembly of heterochromatin in fission yeast. FEBS Lett 2005, 579, 5872–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zofall, M.; Grewal, S.I. RNAi-mediated heterochromatin assembly in fission yeast. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2006, 71, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, H.; Goto, D.B.; Martienssen, R.A.; Urano, T.; Furukawa, K.; Murakami, Y. RNA polymerase II is required for RNAi-dependent heterochromatin assembly. Science 2005, 309, 467–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorida, M.; Hirauchi, T.; Ishizaki, H.; Kaito, W.; Shimada, A.; Mori, C.; Chikashige, Y.; Hiraoka, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Ohkawa, Y.; et al. Regulation of ectopic heterochromatin-mediated epigenetic diversification by the JmjC family protein Epe1. PLoS Genet 2019, 15, e1008129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zofall, M.; Sandhu, R.; Holla, S.; Wheeler, D.; Grewal, S.I.S. Histone deacetylation primes self-propagation of heterochromatin domains to promote epigenetic inheritance. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2022, 29, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eissenberg, J.C.; Elgin, S.C. HP1a: a structural chromosomal protein regulating transcription. Trends Genet 2014, 30, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canzio, D.; Liao, M.; Naber, N.; Pate, E.; Larson, A.; Wu, S.; Marina, D.B.; Garcia, J.F.; Madhani, H.D.; Cooke, R.; et al. A conformational switch in HP1 releases auto-inhibition to drive heterochromatin assembly. Nature 2013, 496, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowieson, N.P.; Partridge, J.F.; Allshire, R.C.; McLaughlin, P.J. Dimerisation of a chromo shadow domain and distinctions from the chromodomain as revealed by structural analysis. Curr Biol 2000, 10, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leopold, K.; Stirpe, A.; Schalch, T. Transcriptional gene silencing requires dedicated interaction between HP1 protein Chp2 and chromatin remodeler Mit1. Genes Dev 2019, 33, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motamedi, M.R.; Hong, E.J.; Li, X.; Gerber, S.; Denison, C.; Gygi, S.; Moazed, D. HP1 proteins form distinct complexes and mediate heterochromatic gene silencing by nonoverlapping mechanisms. Mol Cell 2008, 32, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, T.; Cui, B.; Dhakshnamoorthy, J.; Zhou, M.; Rubin, C.; Zofall, M.; Veenstra, T.D.; Grewal, S.I. Diverse roles of HP1 proteins in heterochromatin assembly and functions in fission yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 8998–9003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadaie, M.; Kawaguchi, R.; Ohtani, Y.; Arisaka, F.; Tanaka, K.; Shirahige, K.; Nakayama, J. Balance between distinct HP1 family proteins controls heterochromatin assembly in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol 2008, 28, 6973–6988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, A.; Dohke, K.; Sadaie, M.; Shinmyozu, K.; Nakayama, J.; Urano, T.; Murakami, Y. Phosphorylation of Swi6/HP1 regulates transcriptional gene silencing at heterochromatin. Genes Dev 2009, 23, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eissenberg, J.C.; Ge, Y.W.; Hartnett, T. Increased phosphorylation of HP1, a heterochromatin-associated protein of Drosophila, is correlated with heterochromatin assembly. J Biol Chem 1994, 269, 21315–21321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minc, E.; Allory, Y.; Worman, H.J.; Courvalin, J.C.; Buendia, B. Localization and phosphorylation of HP1 proteins during the cell cycle in mammalian cells. Chromosoma 1999, 108, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lejeune, E.; Bortfeld, M.; White, S.A.; Pidoux, A.L.; Ekwall, K.; Allshire, R.C.; Ladurner, A.G. The chromatin-remodeling factor FACT contributes to centromeric heterochromatin independently of RNAi. Curr Biol 2007, 17, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahata, S.; Chida, S.; Ohnuma, A.; Ando, M.; Asanuma, T.; Murakami, Y. Two secured FACT recruitment mechanisms are essential for heterochromatin maintenance. Cell Rep 2021, 36, 109540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasher, S.V.; Smith, B.O.; Fogh, R.H.; Nietlispach, D.; Thiru, A.; Nielsen, P.R.; Broadhurst, R.W.; Ball, L.J.; Murzina, N.V.; Laue, E.D. The structure of mouse HP1 suggests a unique mode of single peptide recognition by the shadow chromo domain dimer. EMBO J 2000, 19, 1587–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiru, A.; Nietlispach, D.; Mott, H.R.; Okuwaki, M.; Lyon, D.; Nielsen, P.R.; Hirshberg, M.; Verreault, A.; Murzina, N.V.; Laue, E.D. Structural basis of HP1/PXVXL motif peptide interactions and HP1 localisation to heterochromatin. EMBO J 2004, 23, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Qin, S.; Lei, M.; Tempel, W.; Zhang, Y.; Loppnau, P.; Li, Y.; Min, J. Peptide recognition by heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) chromoshadow domains revisited: Plasticity in the pseudosymmetric histone binding site of human HP1. J Biol Chem 2017, 292, 5655–5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Myers, M.P.; Xu, R.M. Crystal structure of the HP1-EMSY complex reveals an unusual mode of HP1 binding. Structure 2006, 14, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukii, K.; Takahata, S.; Murakami, Y. Histone variant H2A.Z plays multiple roles in the maintenance of heterochromatin integrity. Genes Cells 2022, 27, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murawska, M.; Greenstein, R.A.; Schauer, T.; Olsen, K.C.F.; Ng, H.; Ladurner, A.G.; Al-Sady, B.; Braun, S. The histone chaperone FACT facilitates heterochromatin spreading by regulating histone turnover and H3K9 methylation states. Cell Rep 2021, 37, 109944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murawska, M.; Braun, S. Chaperoning heterochromatin: new roles of FACT in chromatin silencing. Trends Genet 2022, 38, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holla, S.; Dhakshnamoorthy, J.; Folco, H.D.; Balachandran, V.; Xiao, H.; Sun, L.L.; Wheeler, D.; Zofall, M.; Grewal, S.I.S. Positioning Heterochromatin at the Nuclear Periphery Suppresses Histone Turnover to Promote Epigenetic Inheritance. Cell 2020, 180, 150–164 e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machida, S.; Takizawa, Y.; Ishimaru, M.; Sugita, Y.; Sekine, S.; Nakayama, J.I.; Wolf, M.; Kurumizaka, H. Structural Basis of Heterochromatin Formation by Human HP1. Mol Cell 2018, 69, 385–397 e388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).