Submitted:

24 January 2023

Posted:

25 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

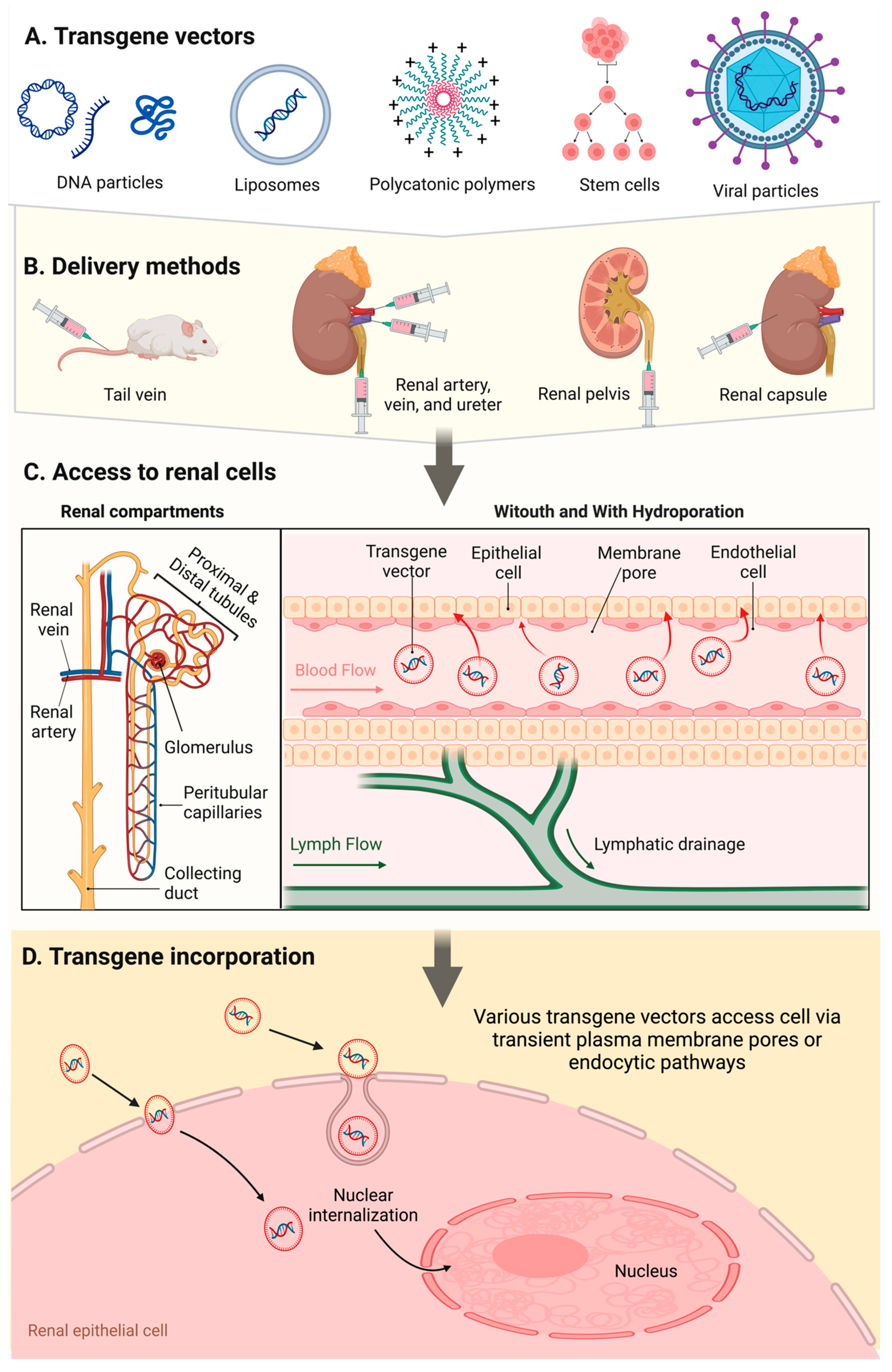

2. Efforts to devise effective genetic alterations in the kidney

2.1. Recombinant peptides and proteins

3.2. Cell and organoid transplantation

2.3. RNA interference therapy

3. Mechanisms for exogenous transgene expression in mammalian cells

4. Key aspects to facilitate advancements in renal genetic medicine

4.1. The development of efficient delivery techniques

- the ability to deliver vectors to the target cells/organ;

- the time the target cell/organs take to express the exogenous materials; and

- the number of cells/organs that express the required phenotype.

4.2. Exogenous transgene vectors

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Isert, S.; Müller, D.; Thumfart, J. Factors Associated With the Development of Chronic Kidney Disease in Children With Congenital Anomalies of the Kidney and Urinary Tract. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, C. , et al., Polycystic kidney disease. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2018. 4(1): p. 50.

- Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Naimi, M.S.; Rasheed, H.; Hussien, N.R.; Al-Gareeb, A. Nephrotoxicity: Role and significance of renal biomarkers in the early detection of acute renal injury. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2019, 10, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burek, M.; Burmester, S.; Salvador, E.; Möller-Ehrlich, K.; Schneider, R.; Roewer, N.; Nagai, M.; Förster, C.Y. Kidney Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury Induces Changes in the Drug Transporter Expression at the Blood–Brain Barrier in vivo and in vitro. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantic, I.; Cumic, J.; Dugalic, S.; Petroianu, G.A.; Corridon, P.R. Gray level co-occurrence matrix and wavelet analyses reveal discrete changes in proximal tubule cell nuclei after mild acute kidney injury. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.I.; Huang, W.; Lobanova, I.; Hanley, D.F.; Hsu, C.Y.; Malhotra, K.; Steiner, T.; Suarez, J.I.; Toyoda, K.; Yamamoto, H.; et al. Systolic Blood Pressure Reduction and Acute Kidney Injury in Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke 2020, 51, 3030–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowski, J. , et al., Cardiovascular Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease. Circulation, 2021. 143(11): p. 1157-1172.

- Jheong, J.-H.; Hong, S.-K.; Kim, T.-H. Acute Kidney Injury After Trauma: Risk Factors and Clinical Outcomes. J. ACUTE CARE Surg. 2020, 10, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, Y., C. Ridel, and M. Touzot, Anaemia and acute kidney injury: the tip of the iceberg? Clinical Kidney Journal, 2020. 14(2): p. 471-473.

- Malyszko, J.; Tesarova, P.; Capasso, G.; Capasso, A. The link between kidney disease and cancer: complications and treatment. Lancet 2020, 396, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forst, T.; Mathieu, C.; Giorgino, F.; Wheeler, D.C.; Papanas, N.; Schmieder, R.E.; Halabi, A.; Schnell, O.; Streckbein, M.; Tuttle, K.R. New strategies to improve clinical outcomes for diabetic kidney disease. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicic, R.; Nicholas, S.B. Diabetic Kidney Disease Back in Focus: Management Field Guide for Health Care Professionals in the 21st Century. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2022, 97, 1904–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adapa, S.; Chenna, A.; Balla, M.; Merugu, G.P.; Koduri, N.M.; Daggubati, S.R.; Gayam, V.; Naramala, S.; Konala, V.M. COVID-19 Pandemic Causing Acute Kidney Injury and Impact on Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease and Renal Transplantation. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2020, 12, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, D.; Kronbichler, A.; Rutter, M.; Bajpai, D.; Menez, S.; Weissenbacher, A.; Anand, S.; Lin, E.; Carlson, N.; Sozio, S.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the kidney community: lessons learned and future directions. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 724–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CKD increases risk of acute kidney injury during hospitalization. Nature Clinical Practice Nephrology, 2008. 4(8): p. 408-408.

- Hsu, R.K.; Hsu, C.-Y. The Role of Acute Kidney Injury in Chronic Kidney Disease. Semin. Nephrol. 2016, 36, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.S.; James, B.D.; Al-Chalabi, S.; Sykes, L.; A Kalra, P.; Green, D. Community- versus hospital-acquired acute kidney injury in hospitalised COVID-19 patients. BMC Nephrol. 2021, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minja, N.W. , et al., Acute Kidney Injury and Associated Factors in Intensive Care Units at a Tertiary Hospital in Northern Tanzania. Can J Kidney Health Dis, 2021. 8: p. 20543581211027971.

- Tanemoto, F.; Mimura, I. Therapies Targeting Epigenetic Alterations in Acute Kidney Injury-to-Chronic Kidney Disease Transition. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, J.C. and L.X. Zhang, Prevalence and Disease Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2019. 1165: p. 3-15.

- Goyal, A. , et al., Acute Kidney Injury (Nursing), in StatPearls. 2022: Treasure Island (FL).

- Palevsky, P.M. Endpoints for Clinical Trials of Acute Kidney Injury. Nephron 2018, 140, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muroya, Y.; He, X.; Fan, L.; Wang, S.; Xu, R.; Fan, F.; Roman, R.J. Enhanced renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in aging and diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2018, 315, F1843–F1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corridon, P.R.; Wang, X.; Shakeel, A.; Chan, V. Digital Technologies: Advancing Individualized Treatments through Gene and Cell Therapies, Pharmacogenetics, and Disease Detection and Diagnostics. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantic, I.V.; Shakeel, A.; Petroianu, G.A.; Corridon, P.R. Analysis of Vascular Architecture and Parenchymal Damage Generated by Reduced Blood Perfusion in Decellularized Porcine Kidneys Using a Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 797283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantic, I.; Paunovic, J.; Cumic, J.; Valjarevic, S.; Petroianu, G.A.; Corridon, P.R. Artificial neural networks in contemporary toxicology research. Chem. Interactions 2023, 369, 110269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, M.; Sekiya, S.; Sakiyama, R.; Shimizu, T.; Nitta, K. Hepatocyte Growth Factor–Secreting Mesothelial Cell Sheets Suppress Progressive Fibrosis in a Rat Model of CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaquer, M.; Franquesa, M.; Vidal, A.; Bolaños, N.; Torras, J.; Lloberas, N.; Herrero-Fresneda, I.; Grinyó, J.M.; Cruzado, J.M. Hepatocyte growth factor gene therapy enhances infiltration of macrophages and may induce kidney repair in db/db mice as a model of diabetes. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 2059–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirooka, Y.; Nozaki, Y. Interleukin-18 in Inflammatory Kidney Disease. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 639103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H. , et al., The Delivery of the Recombinant Protein Cocktail Identified by Stem Cell-Derived Secretome Analysis Accelerates Kidney Repair After Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2022. 10.

- Dai, C.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y. Single Injection of Naked Plasmid Encoding Hepatocyte Growth Factor Prevents Cell Death and Ameliorates Acute Renal Failure in Mice. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002, 13, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlovic, M.; Wever, K.E.; van der Made, T.K.; de Vries, R.B.; Hilbrands, L.B.; Masereeuw, R. Are cell-based therapies for kidney disease safe? A systematic review of preclinical evidence. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 197, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y. , et al., Endogenous hepatocyte growth factor ameliorates chronic renal injury by activating matrix degradation pathways. Kidney Int, 2000. 58(5): p. 2028-43.

- Zhou, D.; Tan, R.J.; Fu, H.; Liu, Y. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in kidney injury and repair: a double-edged sword. Mod. Pathol. 2015, 96, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Brown, P.; Bodles-Brakhop, A.M.; A Pope, M.; Draghia-Akli, R. Gene therapy by electroporation for the treatment of chronic renal failure in companion animals. BMC Biotechnol. 2009, 9, 4–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, A.C.; Bagno, L.L.; Salerno, A.; Florea, V.; Rodriguez, J.; Rosado, M.; Turner, D.; Dulce, R.A.; Takeuchi, L.M.; Kanashiro-Takeuchi, R.M.; et al. Growth hormone-releasing hormone agonists ameliorate chronic kidney disease-induced heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2019835118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.Y.; Peng, P.D.; Ehrhardt, A.; Storm, T.A.; Kay, M.A. Comparison of Adenoviral and Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors for Pancreatic Gene DeliveryIn Vivo. Hum. Gene Ther. 2004, 15, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, G.; Kölling, M.; Wegmann, U.A.; Dettling, A.; Seeger, H.; Schmitt, R.; Soerensen-Zender, I.; Haller, H.; Kistler, A.D.; Dueck, A.; et al. Renal AAV2-Mediated Overexpression of Long Non-Coding RNA H19 Attenuates Ischemic Acute Kidney Injury Through Sponging of microRNA-30a-5p. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 32, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X. , et al., The Long Noncoding RNA-H19 Mediates the Progression of Fibrosis from Acute Kidney Injury to Chronic Kidney Disease by Regulating the miR-196a/Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. Nephron, 2022. 146(2): p. 209-219.

- Qin, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Cao, P.; Qin, C.; Xue, J.; Jia, R. VEGF and Ang-1 promotes endothelial progenitor cells homing in the rat model of renal ischemia and reperfusion injury. . 2017, 10, 11896–11908. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, K.; Maeshima, Y.; Sato, Y.; Wada, J. Antiangiogenic Therapy for Diabetic Nephropathy. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Q.-R.; Chu, Y.-M.; Wei, L.; Tu, C.; Han, Y.-Y. Antiangiogenic therapy in diabetic nephropathy: A double-edged sword (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torras, J. , et al., Gene therapy for acute renal failure. Contrib Nephrol, 2008. 159: p. 96-108.

- AlQahtani, A.D.; O’connor, D.; Domling, A.; Goda, S.K. Strategies for the production of long-acting therapeutics and efficient drug delivery for cancer treatment. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 113, 108750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, J.D.; Barry, M.A. Improving Molecular Therapy in the Kidney. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2020, 24, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, C.J. Cryopreservation of Human Stem Cells for Clinical Application: A Review. Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 2011, 38, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeel, A. and P.R. Corridon, Mitigating challenges and expanding the future of vascular tissue engineering—are we there yet? Frontiers in Physiology, 2023. 13.

- Wang, X.; Chan, V.; Corridon, P.R. Decellularized blood vessel development: Current state-of-the-art and future directions. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 951644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chan, V.; Corridon, P.R. Acellular Tissue-Engineered Vascular Grafts from Polymers: Methods, Achievements, Characterization, and Challenges. Polymers 2022, 14, 4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geuens, T.; van Blitterswijk, C.A.; LaPointe, V.L.S. Overcoming kidney organoid challenges for regenerative medicine. npj Regen. Med. 2020, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshdel-Rad, N.; Ahmadi, A.; Moghadasali, R. Kidney organoids: current knowledge and future directions. Cell Tissue Res. 2022, 387, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Cardilla, A.; Ngeow, J.; Gong, X.; Xia, Y. Studying Kidney Diseases Using Organoid Models. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 845401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papazova, D.A.; Oosterhuis, N.R.; Gremmels, H.; van Koppen, A.; Joles, J.A.; Verhaar, M.C. Cell-based therapies for experimental chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis. Model. Mech. 2015, 8, dmm.017699–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, T. Mesenchymal stem cells: A new therapeutic tool for chronic kidney disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 910592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eirin, A. and L.O. Lerman, Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell–Derived Extracellular Vesicles for Chronic Kidney Disease: Are We There Yet? Hypertension, 2021. 78(2): p. 261-269.

- Wong, C.-Y. Current advances of stem cell-based therapy for kidney diseases. World J. Stem Cells 2021, 13, 914–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missoum, A. Recent Updates on Mesenchymal Stem Cell Based Therapy for Acute Renal Failure. Curr. Urol. 2020, 13, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, K.J.; Kluve-Beckerman, B.; Zhang, J.; Dominguez, J.H. Intravenous cell therapy for acute renal failure with serum amyloid A protein-reprogrammed cells. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2010, 299, F453–F464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatehullah, A.; Tan, S.H.; Barker, N. Organoids as an in vitro model of human development and disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, M. Generating kidney tissue from pluripotent stem cells. Cell Death Discov. 2016, 2, 16053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morizane, R.; Lam, A.Q.; Freedman, B.S.; Kishi, S.; Valerius, M.T.; Bonventre, J.V. Nephron organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells model kidney development and injury. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garreta, E.; Nauryzgaliyeva, Z.; Montserrat, N. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived kidney organoids toward clinical implementations. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 20, 100346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corridon, P.R. Intravital microscopy datasets examining key nephron segments of transplanted decellularized kidneys. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantic, I.V.; Shakeel, A.; Petroianu, G.A.; Corridon, P.R. Analysis of Vascular Architecture and Parenchymal Damage Generated by Reduced Blood Perfusion in Decellularized Porcine Kidneys Using a Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 797283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciampi, O.; Bonandrini, B.; Derosas, M.; Conti, S.; Rizzo, P.; Benedetti, V.; Figliuzzi, M.; Remuzzi, A.; Benigni, A.; Remuzzi, G.; et al. Engineering the vasculature of decellularized rat kidney scaffolds using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Haan, M.J.A. , et al., Have we hit a wall with whole kidney decellularization and recellularization: A review. Current Opinion in Biomedical Engineering, 2021. 20: p. 100335.

- Corridon, P.R.; Ko, I.K.; Yoo, J.J.; Atala, A. Bioartificial Kidneys. Curr. Stem Cell Rep. 2017, 3, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corridon, P.R. In vitro investigation of the impact of pulsatile blood flow on the vascular architecture of decellularized porcine kidneys. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerra, J.; Santos-Ruiz, L.; Andrades, J.A.; Marí-Beffa, M. The Stem Cell Niche Should be a Key Issue for Cell Therapy in Regenerative Medicine. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2010, 7, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haworth, R.; Sharpe, M. The issue of immunology in stem cell therapies: a pharmaceutical perspective. Regen. Med. 2015, 10, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalil, R.A.; Neng, L.C.; Kofidis, T. Challenges in deriving and utilizing stem cell-derived endothelial cells for regenerative medicine: a key issue in clinical therapeutic applications. . 2011, 6, 93–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lepperdinger, G. , et al., Controversial issue: is it safe to employ mesenchymal stem cells in cell-based therapies? Exp Gerontol, 2008. 43(11): p. 1018-23.

- Lin, S.-Z. Era of Stem Cell Therapy for Regenerative Medicine and Cancers: An Introduction for the Special Issue of Pan Pacific Symposium on Stem Cells and Cancer Research. Cell Transplant. 2015, 24, 311–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sell, S. Adult Stem Cell Plasticity: Introduction to the First Issue of Stem Cell Reviews. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2005, 1, 001–008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, N. , An old question becomes new again: stem cell issue causes debate over the exact moment life begins. N Y Times Web, 2001: p. A20.

- Brown, M. NO ETHICAL BYPASS OF MORAL STATUS IN STEM CELL RESEARCH. Bioethics 2011, 27, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.B.; Brandhorst, B.; Nagy, A.; Leader, A.; Dickens, B.; Isasi, R.M.; Evans, D.; Knoppers, B.M. The Use of Fresh Embryos in Stem Cell Research: Ethical and Policy Issues. Cell Stem Cell 2008, 2, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cote, D.J.; Bredenoord, A.L.; Smith, T.R.; Ammirati, M.; Brennum, J.; Mendez, I.; Ammar, A.S.; Balak, N.; Bolles, G.; Esene, I.N.; et al. Ethical clinical translation of stem cell interventions for neurologic disease. Neurology 2017, 88, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habets, M.G.; van Delden, J.J.; Bredenoord, A.L. The inherent ethical challenge of first-in-human pluripotent stem cell trials. Regen. Med. 2014, 9, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, B.; Parham, L. Ethical Issues in Stem Cell Research. Endocr. Rev. 2009, 30, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzar, N.; Manzar, B.; Hussain, N.; Hussain, M.F.A.; Raza, S. The Ethical Dilemma of Embryonic Stem Cell Research. Sci. Eng. Ethic- 2011, 19, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauron, A.; E Jaconi, M. Stem Cell Science: Current Ethical and Policy Issues. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 82, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuklenk, U. HOW NOT TO WIN AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT: EMBRYO STEM CELL RESEARCH REVISITED. Bioethics 2008, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suckiel, E. Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research: A Critical Survey of the Ethical Issues. Adv. Pediatr. 2008, 55, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-J.; Kim, S.-Y.; Jeong, H.-C.; Cheong, H.; Kim, D.; Park, S.-J.; Choi, J.-J.; Kim, H.; Chung, H.-M.; Moon, S.-H.; et al. Repair of Ischemic Injury by Pluripotent Stem Cell Based Cell Therapy without Teratoma through Selective Photosensitivity. Stem Cell Rep. 2015, 5, 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Weissman, I.L.; Drukker, M. The Safety of Embryonic Stem Cell Therapy Relies on Teratoma Removal. Oncotarget 2012, 3, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W. Teratoma formation: A tool for monitoring pluripotency in stem cell research. StemBook 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeles, A.D.L.; Ferrari, F.; Xi, R.; Fujiwara, Y.; Benvenisty, N.; Deng, H.; Hochedlinger, K.; Jaenisch, R.; Lee, S.; Leitch, H.G.; et al. Hallmarks of pluripotency. Nature 2015, 525, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, A.P.; D'Alessandro, B.; Fu, X. Optical Imaging Modalities for Biomedical Applications. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 3, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrzewski, W. , et al., Stem cells: past, present, and future. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 2019. 10(1): p. 68.

- Ghasroldasht, M.M.; Seok, J.; Park, H.-S.; Ali, F.B.L.; Al-Hendy, A. Stem Cell Therapy: From Idea to Clinical Practice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, Y.-H.H.; Lai, L.-W. Renal Gene Transfer: Nonviral Approaches. Mol. Biotechnol. 2003, 24, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.; Dasaradhi, P.V.N.; Mohmmed, A.; Malhotra, P.; Bhatnagar, R.K.; Mukherjee, S.K. RNA Interference: Biology, Mechanism, and Applications. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003, 67, 657–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mangala, L.S.; Rodriguez-Aguayo, C.; Kong, X.; Lopez-Berestein, G.; Sood, A.K. RNA interference-based therapy and its delivery systems. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017, 37, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Verfaillie, C.; Chmielewski, D.; Kren, S.; Eidman, K.; Connaire, J.; Heremans, Y.; Lund, T.; Blackstad, M.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Kidney-Derived Stem Cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 3028–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, G.L.; Blau, H.M. A brief history of RNAi: the silence of the genes. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondue, T.; Heuvel, L.v.D.; Levtchenko, E.; Brock, R. The potential of RNA-based therapy for kidney diseases. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2022, 38, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kameda, S.; Maruyama, H.; Higuchi, N.; Iino, N.; Nakamura, G.; Miyazaki, J.; Gejyo, F. Kidney-targeted naked DNA transfer by retrograde injection into the renal vein in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 314, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, J.K.W.; Chow, M.Y.T.; Zhang, Y.; Leung, S.W.S. siRNA Versus miRNA as Therapeutics for Gene Silencing. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2015, 4, e252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorling, C.A.; Dancik, Y.; Hupple, C.W.; Medley, G.; Liu, X.; Zvyagin, A.V.; Robertson, T.A.; Burczynski, F.J.; Roberts, M.S. Multiphoton microscopy and fluorescence lifetime imaging provide a novel method in studying drug distribution and metabolism in the rat liver in vivo. J. Biomed. Opt. 2011, 16, 086013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schena, F.P.; Serino, G.; Sallustio, F. MicroRNAs in kidney diseases: new promising biomarkers for diagnosis and monitoring. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 29, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saal, S.; Harvey, S.J. MicroRNAs and the kidney: coming of age. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2009, 18, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslan, C.; Kiaie, S.H.; Zolbanin, N.M.; Lotfinejad, P.; Ramezani, R.; Kashanchi, F.; Jafari, R. Exosomes for mRNA delivery: a novel biotherapeutic strategy with hurdles and hope. BMC Biotechnol. 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Huang, H.; Tang, S.; Chai, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, M.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; et al. Recent advances in exosome-mediated nucleic acid delivery for cancer therapy. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, I.K.; Wood, M.J.A.; Fuhrmann, G. Extracellular vesicles as a next-generation drug delivery platform. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Wu, W.; Feng, Y.; Li, Z.; Tang, T.; Liu, B. Therapeutic application of extracellular vesicles in kidney disease: promises and challenges. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 22, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Zhang, C.; Xiong, J. Emerging role of extracellular vesicles in kidney diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 985030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa, R.R.; Juncosa, E.M.; Masereeuw, R.; Lindoso, R.S. Extracellular Vesicles as a Therapeutic Tool for Kidney Disease: Current Advances and Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantaluppi, V. , et al., Microvesicles derived from endothelial progenitor cells protect the kidney from ischemia-reperfusion injury by microRNA-dependent reprogramming of resident renal cells. Kidney Int, 2012. 82(4): p. 412-27.

- Yang, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, T.; Yang, B. Fighting against kidney diseases with small interfering RNA: opportunities and challenges. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.P.; Tadagavadi, R.K.; Ramesh, G.; Reeves, W.B. Mechanisms of Cisplatin Nephrotoxicity. Toxins 2010, 2, 2490–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pabla, N.; Dong, Z. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: Mechanisms and renoprotective strategies. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 994–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peres, L.A.B.; Júnior, A.D.d.C. Acute nephrotoxicity of cisplatin: Molecular mechanisms. Braz. J. Nephrol. 2013, 35, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, B.; Grigorov, B.; Senserrich, J.; Clotet, B.; Darlix, J.-L.; Muriaux, D.; Este, J.A. A clathrin–dynamin-dependent endocytic pathway for the uptake of HIV-1 by direct T cell–T cell transmission. Antivir. Res. 2008, 80, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marina-García, N.; Franchi, L.; Kim, Y.-G.; Hu, Y.; Smith, D.E.; Boons, G.-J.; Núñez, G. Clathrin- and Dynamin-Dependent Endocytic Pathway Regulates Muramyl Dipeptide Internalization and NOD2 Activation. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 4321–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiejak, J.; Surmacz, L.; Wyroba, E. Dynamin- and clathrin-dependent endocytic pathway in unicellular eukaryoteParamecium. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004, 82, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, M.J.; Bardell, T.K.; Yates, M.L.; Placzek, E.A.; Barker, E.L. RNA Interference-Mediated Knockdown of Dynamin 2 Reduces Endocannabinoid Uptake into Neuronal dCAD Cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 74, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.M.; Rhodes, G.J.; Sandoval, R.M.; Corridon, P.R.; Molitoris, B.A. In vivo multiphoton imaging of mitochondrial structure and function during acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2013, 83, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahadevappa, R.; Nielsen, R.; Christensen, E.I.; Birn, H. Megalin in acute kidney injury: foe and friend. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2014, 306, F147–F154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, J.; Saito, M.; Adachi, Y.; Yumoto, R.; Takano, M. Inhibition of gentamicin binding to rat renal brush-border membrane by megalin ligands and basic peptides. J. Control. Release 2006, 112, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokman, G.; Qin, Y.; Rácz, Z.; Hamar, P.; Price, L.S. Application of siRNA in targeting protein expression in kidney disease. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010, 62, 1378–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Du, C.; Yan, L.; Wei, J.; Wu, H.; Shi, Y.; Duan, H. CTGF siRNA ameliorates tubular cell apoptosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis in obstructed mouse kidneys in a Sirt1-independent manner. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2015, ume 9, 4155–4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Kornbrust, D.J.; Foy, J.W.-D.; Solano, E.C.; Schneider, D.J.; Feinstein, E.; Molitoris, B.A.; Erlich, S. Toxicological and Pharmacokinetic Properties of Chemically Modified siRNAs Targeting p53 RNA Following Intravenous Administration. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2012, 22, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, R.; Isaka, Y.; Sandoval, R.M.; Ori, A.; Adamsky, S.; Feinstein, E.; Molitoris, B.A.; Takahara, S. Intravital Two-Photon Microscopy Assessment of Renal Protection Efficacy of siRNA for p53 in Experimental Rat Kidney Transplantation Models. Cell Transplant. 2010, 19, 1659–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molitoris, B.A.; Dagher, P.C.; Sandoval, R.M.; Campos, S.B.; Ashush, H.; Fridman, E.; Brafman, A.; Faerman, A.; Atkinson, S.J.; Thompson, J.D.; et al. siRNA Targeted to p53 Attenuates Ischemic and Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 1754–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouillet, P.; Robati, M.; Bath, M.; Strasser, A. Polycystic kidney disease prevented by transgenic RNA interference. Cell Death Differ. 2005, 12, 831–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corridon, P.; Rhodes, G.J.; Leonard, E.C.; Basile, D.; Ii, V.H.G.; Bacallao, R.L.; Atkinson, S.J. A method to facilitate and monitor expression of exogenous genes in the rat kidney using plasmid and viral vectors. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2013, 304, F1217–F1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvshani-Eshet, M., T. Haber, and M. Machluf, Insight concerning the mechanism of therapeutic ultrasound facilitating gene delivery: increasing cell membrane permeability or interfering with intracellular pathways? Hum Gene Ther, 2014. 25(2): p. 156-64.

- Felgner, J.; Kumar, R.; Sridhar, C.; Wheeler, C.; Tsai, Y.; Border, R.; Ramsey, P.; Martin, M.; Felgner, P. Enhanced gene delivery and mechanism studies with a novel series of cationic lipid formulations. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 2550–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandinetti, G., A. E. Smith, and T.M. Reineke, Membrane and Nuclear Permeabilization by Polymeric pDNA Vehicles: Efficient Method for Gene Delivery or Mechanism of Cytotoxicity? Molecular Pharmaceutics, 2012. 9(3): p. 523-538.

- Wickham, T. A Novel Approach and a Novel Mechanism for Stealthing Gene Delivery Vehicles. Mol. Ther. 2000, 2, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, L.; Park, F. Gene therapy research for kidney diseases. Physiol. Genom. 2019, 51, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, D.; Nguyen, Q.; Kayal, S.; Preiser, P.; Rawat, R.; Ramanujan, R. Insights into the mechanism of magnetic particle assisted gene delivery. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.S.; Kim, H.H.; Yang, J.M.; Shin, S. An insight into the gene delivery mechanism of the arginine peptide system: Role of the peptide/DNA complex size. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 2006, 1760, 1604–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnaggar, R.; Hanawa, H.; Liu, H.; Yoshida, T.; Hayashi, M.; Watanabe, R.; Abe, S.; Toba, K.; Yoshida, K.; Chang, H.; et al. The effect of hydrodynamics-based delivery of an IL-13-Ig fusion gene for experimental autoimmune myocarditis in rats and its possible mechanism. Eur. J. Immunol. 2005, 35, 1995–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H. , et al., Effect of hydrodynamics-based gene delivery of plasmid DNA encoding interleukin-1 receptor antagonist-Ig for treatment of rat autoimmune myocarditis: possible mechanism for lymphocytes and noncardiac cells. Circulation, 2005. 111(13): p. 1593-600.

- McKay, T.; Reynolds, P.; Jezzard, S.; Curiel, D.; Coutelle, C. Secretin-Mediated Gene Delivery, a Specific Targeting Mechanism with Potential for Treatment of Biliary and Pancreatic Disease in Cystic Fibrosis. Mol. Ther. 2002, 5, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simeoni, F. Insight into the mechanism of the peptide-based gene delivery system MPG: implications for delivery of siRNA into mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 2717–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corridon, P.R.; Karam, S.H.; Khraibi, A.A.; Khan, A.A.; Alhashmi, M.A. Intravital imaging of real-time endogenous actin dysregulation in proximal and distal tubules at the onset of severe ischemia-reperfusion injury. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipowicz, W. RNAi: The Nuts and Bolts of the RISC Machine. Cell 2005, 122, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, A.J.; MacRae, I.J. The RNA-induced Silencing Complex: A Versatile Gene-silencing Machine. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 17897–17901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Edwards, J.P.; Mosser, D.M. The Expression of Exogenous Genes in Macrophages: Obstacles and Opportunities; Humana Press: 2009; Volume 531, pp. 123–143. [CrossRef]

- Arrighi, N. , 3 - Stem Cells at the Core of Cell Therapy, in Stem Cells, N. Arrighi, Editor. 2018, Elsevier. p. 73-100.

- Crystal, R.G. Adenovirus: The First EffectiveIn VivoGene Delivery Vector. Hum. Gene Ther. 2014, 25, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredsson, F.P., A. S. Lewin, and R.J. Mandel, RNA knockdown as a potential therapeutic strategy in Parkinson's disease. Gene Therapy, 2006. 13(6): p. 517-524.

- Katz, M.G.; Fargnoli, A.S.; Williams, R.D.; Bridges, C.R. Gene Therapy Delivery Systems for Enhancing Viral and Nonviral Vectors for Cardiac Diseases: Current Concepts and Future Applications. Hum. Gene Ther. 2013, 24, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayerossadat, N.; Maedeh, T.; Ali, P. Viral and nonviral delivery systems for gene delivery. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2012, 1, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamimura, K.; Suda, T.; Zhang, G.; Liu, D. Advances in Gene Delivery Systems. Pharm. Med. 2011, 25, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Saini, M.; Bisht, D.; Rana, M.; Bachan, R.; Gogoi, S.M.; Buragohain, B.M.; Barman, N.N.; Gupta, P.K. Lentiviral-mediated delivery of classical swine fever virus Erns gene into porcine kidney-15 cells for production of recombinant ELISA diagnostic antigen. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 3865–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Ren, Y.; Wang, X.; Lazar, L.; Ma, S.; Weng, G.; Zhao, J. Application of Ultrasound-Targeted Microbubble Destruction–Mediated Exogenous Gene Transfer in Treating Various Renal Diseases. Hum. Gene Ther. 2019, 30, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, A.L.; Corridon, P.R.; Zhang, S.; Xu, W.; Witzmann, F.A.; Collett, J.A.; Rhodes, G.J.; Winfree, S.; Bready, D.; Pfeffenberger, Z.J.; et al. Exogenous Gene Transmission of Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 2 Mimics Ischemic Preconditioning Protection. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 1154–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A. , et al., Adenoviral delivery of the beta2-adrenoceptor gene in sepsis: a subcutaneous approach in rat for kidney protection. Clin Sci (Lond), 2005. 109(6): p. 503-11.

- Verkman, A.S.; Yang, B. Aquaporin gene delivery to kidney. Kidney Int. 2002, 61, S120–S124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, E.; Isaka, Y. Strategies of gene transfer to the kidney. Kidney Int. 1998, 53, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boletta, A.; Benigni, A.; Lutz, J.; Remuzzi, G.; Soria, M.R.; Monaco, L. Nonviral Gene Delivery to the Rat Kidney with Polyethylenimine. Hum. Gene Ther. 1997, 8, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapturczak, M.H.; Chen, S.; Agarwal, A. Adeno-associated virus vector-mediated gene delivery to the vasculature and kidney. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2005, 52, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Gordillo, D.; Trujillo-Provencio, C.; Knight, V.B.; Serrano, E.E. Optimization of gene delivery methods in Xenopus laevis kidney (A6) and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell lines for heterologous expression of Xenopus inner ear genes. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. - Anim. 2011, 47, 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, G.A.; Sandoval, R.M.; Molitoris, B.A.; Bamburg, J.R.; Ashworth, S.L. Micropuncture gene delivery and intravital two-photon visualization of protein expression in rat kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2005, 289, F638–F643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, H.; Li, K.; Sun, C.; Du, W.; Cui, J.; Zhao, X.; Chen, W. A Magnetic Nanoparticle-Based Multiple-Gene Delivery System for Transfection of Porcine Kidney Cells. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e102886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.; Pua, E.C.; Lu, X.; Zhong, P. Low-amplitude ultrasound enhances hydrodynamic-based gene delivery to rat kidney. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 386, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G. , et al., Adenovirus-mediated beta-galactosidase gene delivery to the liver leads to protein deposition in kidney glomeruli. Kidney Int, 1997. 52(4): p. 992-9.

- Friedmann, T. A New Serious Adverse Event in a Gene Therapy Study. Mol. Ther. 2007, 15, 1899–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, G.A.R. and R.M.A. Paiva, Gene therapy: advances, challenges and perspectives. Einstein (Sao Paulo), 2017. 15(3): p. 369-375.

- Tremblay, J.P.; Annoni, A.; Suzuki, M. Three Decades of Clinical Gene Therapy: From Experimental Technologies to Viable Treatments. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, R.; Subramanian, G.; Silayeva, L.; Newkirk, I.; Doctor, D.; Chawla, K.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Chandra, D.; Chilukuri, N.; Betapudi, V. Gene Therapy Leaves a Vicious Cycle. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, N.; Lai, A.C.-K.; Liao, K.; Corridon, P.R.; Graves, D.J.; Chan, V. Recent Advances in Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleaching for Decoupling Transport and Kinetics of Biomacromolecules in Cellular Physiology. Polymers 2022, 14, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaya, J.; Corridon, P.R.; Al-Omari, B.; Aoudi, A.; Shunnar, A.; Mohideen, M.I.H.; Qurashi, A.; Michel, B.Y.; Burger, A. Design, photophysical properties, and applications of fluorene-based fluorophores in two-photon fluorescence bioimaging: A review. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C: Photochem. Rev. 2022, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickson, L.J.; Eirin, A.; Lerman, L.O. Challenges and opportunities for stem cell therapy in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2016, 89, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, M.A.S.; Leonard, J.P.; Flasshove, M.; Bertino, J.; Gallardo, H.; Sadelain, M. Gene therapy - the challenge for the future. Ann. Oncol. 1996, 7, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshimura, M.; Kazuki, Y.; Uno, N. [Challenge toward gene-therapy using iPS cells for Duchenne muscular dystrophy]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 2012, 52, 1139–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, F.; Passarinha, L.; Queiroz, J. Biomedical application of plasmid DNA in gene therapy: A new challenge for chromatography. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2009, 26, 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokman, M.F.; Renkema, K.Y.; Giles, R.H.; Schaefer, F.; Knoers, N.V.; van Eerde, A.M. The expanding phenotypic spectra of kidney diseases: insights from genetic studies. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Chen, B.K.; Mosoian, A.; Hays, T.; Ross, M.J.; Klotman, P.E.; Klotman, M.E. Virological Synapses Allow HIV-1 Uptake and Gene Expression in Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 22, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gusella, G.L.; Fedorova, E.; Marras, D.; Klotman, P.E.; Klotman, M.E. In vivo gene transfer to kidney by lentiviral vector. Kidney Int. 2002, 61, S32–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deen, W.M. , What determines glomerular capillary permeability? J Clin Invest, 2004. 114(10): p. 1412-4.

- Deen, W.M.; Lazzara, M.J.; Myers, B.D.; Navar, L.G.; Richfield, O.; Kasztan, M.; Piwkowska, A.; Kreft, E.; Rogacka, D.; Audzeyenka, I.; et al. Structural determinants of glomerular permeability. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2001, 281, F579–F596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drumond, M.C.; Deen, W.M. Structural determinants of glomerular hydraulic permeability. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 1994, 266, F1–F12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, R.; Kami, D.; Kusaba, T.; Kirita, Y.; Kishida, T.; Mazda, O.; Adachi, T.; Gojo, S. Kidney-specific Sonoporation-mediated Gene Transfer. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Tan, K.; Hua, X.; Gong, J. Renal interstitial permeability changes induced by microbubble-enhanced diagnostic ultrasound. J. Drug Target. 2013, 21, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiser, J.; Gupta, V.; Kistler, A.D. Toward the development of podocyte-specific drugs. Kidney Int. 2010, 77, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appledorn, D.M., S. Seregin, and A. Amalfitano, Adenovirus vectors for renal-targeted gene delivery. Contrib Nephrol, 2008. 159: p. 47-62.

- Ye, X.; Jerebtsova, M.; Liu, X.-H.; Li, Z.; Ray, P.E. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to renal glomeruli in rodents. Kidney Int. 2002, 61, S16–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Liu, X.-H.; Li, Z.; Ray, P.E. Efficient Gene Transfer to Rat Renal Glomeruli with Recombinant Adenoviral Vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2001, 12, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, E. Gene therapy approach in renal disease in the 21st century. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2001, 16, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moullier, P.; Friedlander, G.; Calise, D.; Ronco, P.; Perricaudet, M.; Ferry, N. Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer to renal tubular cells in vivo. Kidney Int. 1994, 45, 1220–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti-Pierri, N.; E Stapleton, G.; Palmer, D.J.; Zuo, Y.; Mane, V.P.; Finegold, M.J.; Beaudet, A.L.; Leland, M.M.; E Mullins, C.; Ng, P. Pseudo-hydrodynamic Delivery of Helper-dependent Adenoviral Vectors into Non-human Primates for Liver-directed Gene Therapy. Mol. Ther. 2007, 15, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, S.; Sandoval, R.; Tanner, G.; Molitoris, B. Two-photon microscopy: Visualization of kidney dynamics. Kidney Int. 2007, 72, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, T.; Liu, D. Hydrodynamic Gene Delivery: Its Principles and Applications. Mol. Ther. 2007, 15, 2063–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collett, J.A.; Corridon, P.R.; Mehrotra, P.; Kolb, A.L.; Rhodes, G.J.; Miller, C.A.; Molitoris, B.A.; Pennington, J.G.; Sandoval, R.M.; Atkinson, S.J.; et al. Hydrodynamic Isotonic Fluid Delivery Ameliorates Moderate-to-Severe Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rat Kidneys. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 2081–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Gao, X.; Song, Y.K.; Vollmer, R.; Stolz, D.B.; Gasiorowski, J.Z.; A Dean, D.; Liu, D. Hydroporation as the mechanism of hydrodynamic delivery. Gene Ther. 2004, 11, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, N.; Kawaguchi, M.; Itaka, K.; Kawakami, S. Efficient Messenger RNA Delivery to the Kidney Using Renal Pelvis Injection in Mice. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corridon, P.; Rhodes, G.; Zhang, S.; Bready, D.; Xu, W.; Witzmann, F.; Atkinson, S.; Basile, D.; Bacallao, R. Hydrodynamic delivery of mitochondrial genes in vivo protects against moderate ischemia-reperfusion injury in the rat kidney (690.17). FASEB J. 2014, 28, 690.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, L.E.; Cheng, J.; Welch, R.C.; Williams, F.M.; Luo, W.; Gewin, L.S.; Wilson, M.H. Kidney-specific transposon-mediated gene transfer in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep44904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, E. Gene therapy for the treatment of renal disease: prospects for the future. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 1997, 6, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonamassa, B.; Hai, L.; Liu, D. Hydrodynamic Gene Delivery and Its Applications in Pharmaceutical Research. Pharm. Res. 2010, 28, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, C.J.; Ur, S.N.; Harrison, F.; Cherqui, S. rAAV9 combined with renal vein injection is optimal for kidney-targeted gene delivery: conclusion of a comparative study. Gene Ther. 2014, 21, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zincarelli, C.; Soltys, S.; Rengo, G.; E Rabinowitz, J. Analysis of AAV Serotypes 1–9 Mediated Gene Expression and Tropism in Mice After Systemic Injection. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Fan, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, L. Strategies on the nuclear-targeted delivery of genes. J. Drug Target. 2013, 21, 926–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, S.T. The DNA Exonucleases of Escherichia coli. EcoSal Plus 2011, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermić, D. , Functions of multiple exonucleases are essential for cell viability, DNA repair and homologous recombination in recD mutants of Escherichia coli. Genetics, 2006. 172(4): p. 2057-69.

- Villalba, M.; Ferrari, D.; Bozza, A.; Del Senno, L.; Di Virgilio, F. Ionic regulation of endonuclease activity in PC12 cells. Biochem. J. 1995, 311, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Schwartz, D.; Quinn, T.J.; Thorne, P.S.; Sayeed, S.; Yi, A.K.; Krieg, A.M. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA cause inflammation in the lower respiratory tract. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 100, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, K.S. , Antisense oligonucleotide therapies: the promise and the challenges from a toxicologic pathologist's perspective. Toxicol Pathol, 2015. 43(1): p. 78-89.

- Tenenbaum, L.; Lehtonen, E.; Monahan, P.E. Evaluation of Risks Related to the Use of Adeno-Associated Virus-Based Vectors. Curr. Gene Ther. 2003, 3, 545–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.E.; Ehrhardt, A.; Kay, M.A. Progress and problems with the use of viral vectors for gene therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003, 4, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggio, I.; Holkers, M.; Liu, J.; Janssen, J.M.; Chen, X.; Gonçalves, M.A.F.V. Adenoviral vector delivery of RNA-guided CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease complexes induces targeted mutagenesis in a diverse array of human cells. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uren, A.G.; Kool, J.; Berns, A.; van Lohuizen, M. Retroviral insertional mutagenesis: past, present and future. Oncogene 2005, 24, 7656–7672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhou, Z.-W.; Ju, Z.; Wang, Z.-Q. DNA Damage Response in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Ageing. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2016, 14, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Infusion Site |

Infusion Method |

Infusion Compound |

Auxiliary Gene Enhancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tail vein | Systemic injection (normal volume and pressure) |

Plasmid and viral vectors, cells | None reported |

| Renal artery, renal vein, renal pelvis, ureter | Low pressure injections Hydrodynamic injections |

DNA particles, liposomes, polycations, stem cells and viral vectors |

Electroporation, microbubble cavitation, ultrasound cavitation, ultrasound and microbubble coupled cavitation |

| Renal capsule | Micropuncture and blunt needle injections | Viral vectors | None reported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).