1. Introduction

Cleaning compulsion is universally acknowledged as a

symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD); it is mentioned in every description

of OCD, is a recurring subscale in every multidimensional inventory of OCD, and

emerges as a factor in every factor analysis of the scores on such inventories.

In discussions of this cluster of compulsions, the prevailing view is that irrational

worries about possible contamination with dangerous or disgusting things are the

sole motivational source of this compulsion. Discussions regarding the cleaning

involved revolve around frequent hand-washing, undertaken to undo the contamination,

supplemented by object-cleaning to preclude a renewed contamination of one’s skin

by touching the object (e.g., doorknobs and handrails).

However, in daily life, much cleaning is undertaken

as part of keeping one’s home tidy. This cleaning involves dusting, wiping, brushing,

sweeping, and vacuuming, and is exclusively directed to floors, furniture, tools,

cupboards, and ornaments. It serves partly to adhere to a conventional degree

of hygiene but mainly to remove remains from natural processes (e.g., dust settling

down) and previous activities (e.g., dirt; sticky, greasy, slithery, or powdery

substances). It is often complemented with other aspects of tidying, such

as discarding rubbish, and putting back tools, objects of action, and furniture

to where they belong. Spaces to which objects “belong” are usually arranged according

to some formal criterion, meaning that ordering is also part of tidying.

Achieving and restoring domestic cleanliness may be

as likely to assume excessive and compulsive proportions as cleaning associated

with contamination anxiety. It starts as a set of conventional domestic tasks; the

pathology arises when the person executing them, for some obscure reason, becomes

unable to get satisfied with it, even though it looks perfect from the outside.

1.1. An Ill-Acknowledged Obsessive-Compulsive Symptom Cluster

So far, however, this symptom cluster is ill-acknowledged

in the scientific OCD literature.

Compulsive domestic cleaning never became an

object of empirical investigation, nor an independent subscale in the presently

much used obsessive-compulsive inventories. And lacking the relevant items, it could

not emerge as a factor in factor-analytic studies employing such instruments either.

The sparse cleaning items that could be candidates for representing excessive domestic

cleaning have routinely been assigned to the contamination anxiety subscale of OCD

questionnaires.

Only Tallis (1996) [1]

‒ in a brief contribution ‒ warned that not all compulsive cleaning should be seen

as motivated by contamination anxiety. He considered the exceptions to be driven

by perfectionism. And Summerfeldt (2004, p. 1156) [2],

discussing the limitations of classifying obsessive-compulsive symptoms merely based

on behavioral similarities, remarked:

“Someone may clean to eradicate germs and prevent harm or to preserve the perfect pristine state of belongings and regain a sense of satisfaction or inner completeness, with little sense of threat (Tallis, 1996), although popular classification would collapse all such behaviors into the ‘cleaning’ category.”

These short notes, however, did not lead to an empirical

interest in domestic cleaning compulsion, even though heterogeneity of OCD is generally

acknowledged, these days.

The aim of this paper is to examine whether domestic

cleaning compulsion should be recognized by the scientific community as one of the

potential subcategories of OCD (or as an important facet of an acknowledged subcategory),

meriting clinical and empirical interest in its own right. This is done by summarizing

and presenting the modest clinical and empirical evidence for it so far, followed

by the discussion of a novel study by the present author in which data from two

OCD samples from the past are reanalyzed.

2. Clinical Evidence

2.1. The Leyton Obsessional Inventory

A notable exception to the omission noted above is John

Cooper (1970) [3]. He notes that, while he and

McNeil (1968) [4] were doing a study on mother-child

interaction in Brittany, local authority health visitors called their attention

to “a group of mothers who were considered … to be unusually house-proud or perfectionist

in their approach to housework and child-rearing”, which could harm the interactions

with their children ([3], p. 48). This house-proud

housekeeping style was suggestive of obsessive-compulsive problems, and that is

why Cooper [3] devised an inventory to assess obsessive-compulsive

symptoms and traits. Such a measure was still lacking at the time. Several items

referring to excessive domestic cleaning and other household chores were included

in this inventory.

The original version of Cooper’s early OCD inventory

consisted of 46 questions referring to obsessive-compulsive symptoms and

23 items referring to ditto traits (the distinction between both is not always

obvious and is mostly ignored). Subjects had to rate whether the symptom or trait

applied to them. If it did, then, they rated the degree in which they resisted their

tendencies (on a 5-point scale) as well as the degree in which the behavior interfered

with the remainder of their activities (4-point scale).

In 1973, Cooper and Kelleher [5] used a

much less time-consuming self-rating version, in which subjects had to judge

the degree of interference by each mentioned symptom and trait directly.

Cooper [3] devised

the LOI to assess OCD in general, not as an exclusive measure of excessive

domestic cleaning. However, his interest in house-proud housewives led to the inclusion

of 12 items related to maintaining the cleanliness and tidiness of one’s clothes,

rooms, furniture, floors, and other things in the house. The author also included

items about other peculiarities of house-proud housewives: 4 items referring to

ordering and arranging, 4 items pertaining to rigidly scheduling one’s activities,

and one item referring to both. These reflect the clinical impressions of Cooper

and McNeil [4] regarding this house-proudness,

and could be taken as a prediction of the items of a tidying compulsion symptom

cluster. That is the reason to reproduce these 21 items in Appendix 1. A look at

it may help to get a clearer picture of what this excessive and compulsive tidying

may encompass.

2.2. Anecdotal Evidence

From 1974 to 1981, the present author conducted an OCD

project at the Department of Clinical Psychology of the University of Nijmegen,

the Netherlands. In it, graduate students in clinical psychology were assigned to

treat obsessive-compulsive patients at the latter’s homes, instructed and supervised

by a colleague1. Under the present author’s supervision, they wrote their

doctoral thesis about what they learned about the patients’ OCD by interviewing

and treating them. They were invited to include tentative ideas about the etiological

and maintaining factors in their patient’s OCD.

In one of the earliest theses in the project, two students

reported their joint treatment of a man and a woman in their thirties (Van Boekel

en Meulendijk, 1976) [6].

The man’s tidiness compulsion had begun when he was at home on sick leave for months because two stress factors disabled him from continuing his professional duties : 1) the experience of a decline in status and authority in his administrative job in a factory after it fused with another, bigger company; 2) the pending birth of his first child, which ‒ in his eyes - would imply a decline in the contact with his wife.

The factory was close to his house and its dust penetrated the window chinks. This irritated him and made him cleaning the chinks. However, the relief was short-lasting and he had to clean them anew. This rapidly intensified and generalized to other parts of the house as well. In addition, he started to rearrange the living room’s furniture in a rigid way. These activities developed into a full-blown tidying compulsion, with which he increasingly tyrannized his wife and later also his child.

The woman led a somewhat lonely, one-sided, and conventional life as a lower-class housewife in a small village. Her tidying became excessive in the course of a year, after both of her two children were absent during a part of the day for being at school. The students guessed that she vainly tried to compensate for her increased loneliness and boredom by putting more diligence and perfection in her housekeeping tasks. The perfectionism assumed pathological proportions, at the expense of other household jobs, her leisure time and relaxation, and her contact with the children and spouse.

Note that the man’s tidying compulsion was of a defensive

and aggressive nature, aimed at a strict control of the home, whereas the excessive

tidying of the woman was a desperate attempt at doing her best in her housewife

role: over-assertion versus over-adjustment.

In another thesis (De Bruyn, 1980) [7], the case of a young woman (here, for convenience,

called Grace) was described.

Grace had led a sheltered life at home, dominated by her house-proud mother, until she moved to a city to study on the university. Unskilled in building a social life in a new environment, she experienced a lonely first year in a rented room. She sought solace in eating sweets and tidying. (The latter had been part of her upbringing through the instructions and example of her overly tidy mother).

In her second year, she moved to a student dormitory, in which her life became much more social. She got a nice relation with a fellow male student, and after another year, the two married. Everything went fine until her spouse found out that ‒ unlike he had hoped on before ‒ a bodily handicap of his could not be cured. He started to drink alcohol excessively and the marital relation became very problematic.

Under these conditions, the young woman intensified her so far somewhat exaggerated tidiness to a full-blown tidiness compulsion, as if perfection in housekeeping could solve the problems.

In 1981, Hoogduin et al. [8]

described the case of a woman, suffering from “housekeeping compulsion”, as the

authors called it. They considered it motivated by perfectionism.

In 2013, the German journalist, Weiora de Sirow [9], published a booklet about Putzzwang (i.e.,

domestic cleaning compulsion). The book dwells on its problematic nature, its impact

on the housemates, and what to do about it.

In 2020, the Polish philologist and art historian, Piotr

Oczko, published a historical study of the Dutch “obsession with domestic cleaning,

that is, the fanatic insistence on excessive tidiness in one’s household [10]. This “obsession” with dirt and dust, which detracted

from the perfect state of one's property, started in the seventeenth century, initially

among the wealthy bourgeois part of the population (who could afford maids to do

the work), but in the ages that followed, it became widespread among Dutch housewives

(who had to do it themselves).

2.3. A Case Vignette

A case vignette of tidying compulsion, published by

Penzel (198) [10] on the internet, may give the

reader a clearer picture of what proportions this variant of OCD may assume. With

the kind permission of that author, parts of it are reproduced below.

“Recently, a couple came to see me at my practice. They were both in their early 40s, professionals, nicely dressed. The husband began our session by saying: “Doctor, have you ever seen anyone scrub a ceiling, or polish a towel bar? I can’t live like this anymore.... He went on to relate how every day of the week his wife had a compulsive and meticulous cleaning routine that lasted about six hours, beginning on weekdays with her return from work and ending about midnight…. It was always done in the same order. He also complained that he and the children were … not allowed to eat in the kitchen because it would dirty the floor with crumbs. … The living room was off-limits because lint or dirt might get on the carpet or the furniture, or the couch cushions might get disarranged.

“A need for symmetry was also part of the problem. In the clothes closets, all the hangers had to be the same distance apart. All boxes, cans, and containers in the pantry and refrigerator had to be lined up in size order with the labels facing forward. … [His wife] had someone come in to clean her home every week, but she would follow the cleaning person and clean everything again herself.

“When the wife finally spoke, it was to explain: ‘I don’t know why I do it, exactly. It’s not that I’m afraid of germs or contamination. I just don’t feel right unless everything is perfectly clean and in order. It makes me angry and anxious if things get messed up, and I can’t concentrate on anything else until it’s fixed. I feel like my house is the one thing I have control over. …. It began very gradually in small ways… It seems to have a life of its own. I’d like to stop, but I’ve been doing this for so many years, that I just can’t imagine myself acting differently. I don’t know how I would stand the anxiety it would cause me.’”

Notice that ordering/arranging and sticking to schedules

are other parts of her excessive domestic activity. Her motivation seems a desire

to exert a strict control over the home-environment. The anxiety involved ‒ as she

admits herself ‒ is a fear of losing that control, not a fear of contamination.

3. Empirical Evidence from Studies with the LOI

The LOI was explicitly devised to study obsessive-compulsive

behavior in house-proud housewives. What evidence for the existence of excessive

and compulsive domestic cleaning and tidying did research with the LOI produce so

far?

3.1. Cooper’s Research

Cooper [3] administered

his LOI to a sample of obsessional patients (n=17), a sample of house-proud housewives

(n=25), and community samples (together, n=120). He found that the mean symptom

and trait scores, mean resistance and interference scores of the house-proud sample

lay in between the obsessional sample and the community samples (but closer to the

community sample). However, whether domestic activities by house-proud housewives

had assumed obsessive-compulsive proportion, and whether these were reflected in

a cohesive cluster of items, was not reported. If it had been their one and only

type of OCD, then this may explain their modest LOI-score.

Cooper and Kelleher [5]

used a self-rating version of the LOI and performed a principal component

analysis with orthogonal rotation on the scores of several community samples,

among which those of Cooper [3] (without the small

OCD sample), recombined in different, overlapping ways. The authors used items loading

≥.40 to identify components, but confined these components to seven items. In all

samples and their combinations, the label clean and tidy applied to one of

the components. However, the results for the samples diverged considerably from

each other, perhaps because of the abundance of low scores and/or because of the

arbitrary limit of seven items per component. In addition, the non-clinical nature

of the sample might have precluded tidying compulsion from emerging as a distinct

component.

Murray, Cooper, and Smith (1979) [12] administered the self-rating version of the

LOI to 73 obsessive-compulsive patients and compared the item scores of these with

those of a non-clinical sample (n=100). They followed the same procedures as in

the above-mentioned study. The found a component A, containing three items referring

to tidying, two to arranging, and one to scheduling, as well as a component C, containing

five items clearly referring to domestic cleaning, but also two items that could

betray contamination. This study is not yet conclusive, but it provides some evidence

for the existence of tidying compulsion.

3.2. Investigations with the LOI by other Authors

Wellen et al. (2007) [13]

administered a self-rating version of the LOI to a sample of 488 persons,

consisting of 396 non-clinical subjects and 92 (19%) obsessive-compulsive patients.

The interference scores were analyzed with an exploratory factor analysis

with orthogonal rotation. Four factors were identified based on the items that loaded

≥.50 on a factor:

- 1)

obsessive ruminations and compulsions (a rather divergent collection of 20 items);

- 2)

ordering, arranging, and cleaning (9 of the 16 potentially relevant items);

- 3)

organizing activities in time (5 items among which scheduling);

- 4)

contamination and cleaning (6 items).

The authors report that only Factors 1, 3, and 4 are

strongly associated with OCD, which seems to imply that Factor 2 is weakly associated

with OCD. Unfortunately, in the table with factor loadings, possible cross-loadings

of factor 2 to the other three factors had not been reproduced.

A limitation of this study was that 81% of the sample

that was used for factor analysis consisted of non-clinical subjects. This probably

caused the scores to be skewed in the direction of 1 and zero. This skewness may

have been the reason why the first factor was large and heterogeneous, and may also

have kept the relationship between the factor “ordering-arranging-cleaning” and

the first factor weak. A separate factor analysis of the 92 obsessive-compulsive

patients may still provide a clearer picture.

3.3. Evidence from a Dutch OCD Inventory with LOI Items

Kraaimaat and Van Dam-Baggen (1976) [14] did not use the LOI, but devised a 32-item inventory,

called the IDB, which contained 22 LOI items. The items had been rephrased as statements

to be rated on frequency of occurrence on a 5-point scale. From a

factor analysis

of the scores of 43 OCD patients, a factor emerged, which may well represent tidying

compulsion. This factor was called

Structuring of environment and behavior and

is shown in

Table 1. It explained 20.4% of

the variance and contained 10 items loading ≥.40. The other three factors were labeled:

repeating and checking of one’s doings (6 items), disagreeable and irrational thoughts

(6 items), and contamination (4 items).

To facilitate the interpretation of the Structuring

factor, the present author added “codes” to its items, for a quick recognition of

the symptomatic phenomena they represent.

4. Evidence from a Previous Study by the Present Author

4.1. Construction of an OCD Questionnaire

The present author devised an OCD-questionnaire in 1977

as part of his OCD research project, mentioned in Section 2.2. The project’s aim was to establish

OCD’s heterogeneity in symptom presentation and etiology. Because the interest

was in the clustering of a great diversity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms, the

number of items was unusually large: 108 statements about compulsive behaviors and

obsessive experiences. The statements had to be rated from 1) “(almost) not applicable”

to 5) “(almost) completely applicable”.

4.2. The Instrument

Five more or less independent symptom clusters were

anticipated:

- 1)

contamination anxiety + washing compulsion,

- 2)

fear of (unintentionally and unwittingly) harming other people,

- 3)

obsessions (defined as tabooed and suppressed thoughts, images, and impulses),

- 4)

tidying compulsion (domestic cleaning, ordering, arranging),

- 5)

precision compulsion: being overly uncertain, precise, perfectionist, even or mainly in subordinate activities; ritualizing such activities.

Items

were allocated to these five categories in advance, not with the pretense that this

already implied a well-thought-out prediction, but to increase the chance that the

items would evenly be distributed over the presumptive categories of the questionnaire.

4.3. Participants

Our research group collected the scores of 43 obsessive-compulsive

patients between 1977 and 1980, diagnosed and treated within the project, as well

as elsewhere. The sample consisted of 12 men and 31 women ((28-72%); the average

age of the men was 41.8 years, range 27-50, average age of the women was 42.1 years,

range 21-67); mean Raven score of the men was 50.7 (range 32-58), that of the women

was 45.2 (range 29-60). In 1980, the OCD questionnaire was administered to a community

sample of 52 subjects (paid for their participation), approximately matched on sex,

age, educational and professional level.

4.4. Method

Studying the scores of the patients led to the removal

of 11 from the 108 items for different reasons, among which strong skewness. The

remaining 97 items had mean item scores, ranging from 1.53 to 4.02 for the OCD-sample,

and from 1.02 to 2.31 for the community sample. The samples’ mean scores differed

significantly on 93 of the 97 items (p<.05).

Principal component analyses with oblique rotation

argued for a five components solution, which partly endorsed the a priori categories.

To turn the components into questionnaire subscales, the items had to load ≥.40;

if that was the case, then they were assigned to the cluster in which they had the

highest loading. This resulted in five non-overlapping item clusters in which each

item had a weight of 1, as is common practice in questionnaire subscales.

Subsequently, the correlations between each item and

each cluster’s sum score were calculated (corrected for “self-correlation” if the

item contributes to the sum score). Items correlating <.40 were dismissed. This

transformation results in a matrix of item-cluster correlations.

This matrix indicated that some items had better be

relocated to another cluster, or to the category “non-clustered”. If one modifies

the item-clusters accordingly, the correlations change somewhat and may still show

some non-optimal cluster assignments of the items. Thus, the relocations have to

be iterated in small steps until the item-cluster correlation table is consistent.

(However, minimal differences between correlations were not considered a reason

for further relocation). The final clusters, then, will have been optimized in the

direction of more homogeneity and independence. This procedure is known as item-analysis,

based on classical test-theory (Stouthard, 2006, pp. 349-356). [15] 2

Initially, the item analysis was applied to item-clusters

based on exploratory principal component analysis. However, it might as well start

from predicted item-clusters. Therefore, it was decided to start such item-analysis

from the a-priory categories, as if these were serious predictions. They weren’t,

yet the categories appeared to be a good starting point for being transformed into

homogeneous, final item clusters (resembling the ones derived from the principal

component analysis). The study was published in an internal report of the university

[16]. 3

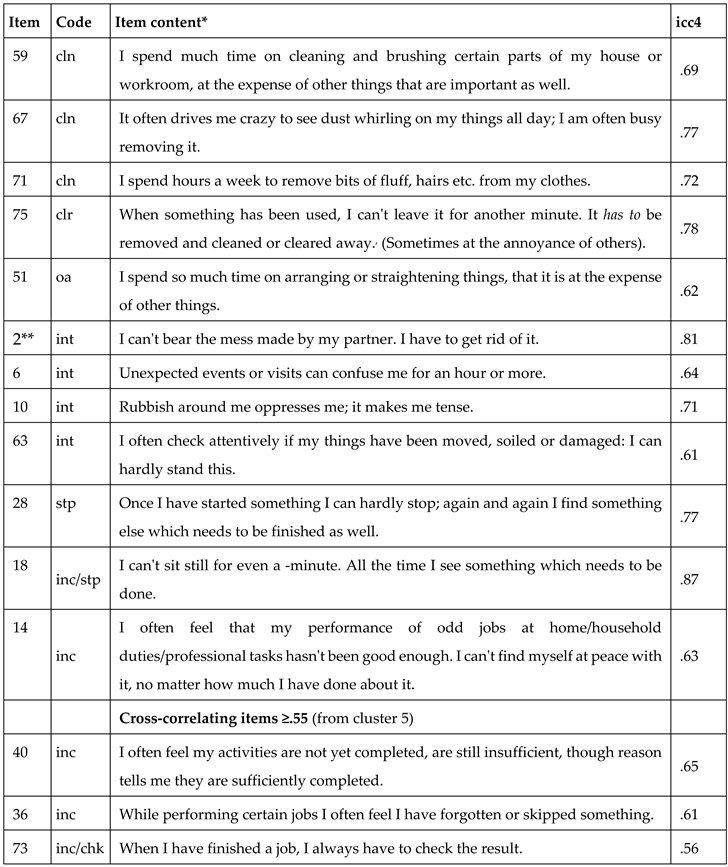

4.5. Results Regarding Tidying Compulsion

The result for the cluster

Tidying compulsion

can be viewed in

Table 2.

Just like had been done in

Table 1, the items in

Table 2 have received a code, which characterizes the symptom concerned. Note that four of the items betray intolerance of minor infringements (by others) on one’s “domain”, and impress as defensive or emotional. Three items refer to excessive cleaning, one to immediately clearing away things used, and one to excessive arranging things. Scheduling items were lacking in this inventory, so could not become part of the cluster.

Item 14 describes incompleteness feelings, just as the cross-correlating items 36 and 40. Items 18 and 28 pertain to the resulting difficulty in stopping. These latter two items seem also tot attest to restlessness and insatiability.

The difficulty in stopping drives the persons involved to ever more precision and perfectionism. However, the items concerned had been allocated to cluster 5, together with incompleteness feelings in general and their impact on behavior (i.e., checking, impaired behavior regulation, ritualizing everyday behavior).

Finally, in

Table 3, we’ll have a look at the other clusters and their correlations. Their labels and alphas are added.

The alphas are quite high, confirming the clusters’ relative homogeneity and reliability, at least in this small sample. The values of the GOF-measure are not shown, but only the one for contamination anxiety was near 1. The other ones varied from poor to moderate. Cl. 4 correlates only.17 with cl. 1, confirming the independence of both types of cleaning compulsion. In contrast, cluster 4’s correlation with cl. 5 is quite high (.63) because of their shared symptom-items (i.e., incompleteness feelings, difficulty in stopping, over-precision).

4.6. Discussion: Optimizing Predicted Clusters

The advantage of basing the optimized clusters on the predicted ones (instead of on exploratory derived ones) is that, then, the item relocations provide feedback to the theoretical ideas and clinical impressions, which have guided the item formulation and category assignments. Comparing the predicted cluster assignments with the final, optimized ones, designates the items as either hits, false positives, or false negatives. And this subdivision of items lends itself to the proposal of a measure, indicating the “goodness of fit” of the prediction: a formula in which the number of hits, proportional to the number of errors, leads to a value between 1 (perfect prediction) and zero (prediction does not exceed chance level). The values of this goodness-of-fit index for the 1981 categories have likewise been reported in [

16].

5. Revision of the OCD Questionnaire and the Cluster Optimization Procedure

A somewhat revised and enlarged version of the questionnaire was administered to patients from 2004 to 2007 for validation. In

Section 6, findings regarding tidying compulsion will be compared between the two samples. In the present section, only the revision of the questionnaire, a critical inspection of the second sample, and a revised cluster prediction will be discussed.

5.1. Revision of the OCD Questionnaire

Of the 97 not-rejected items from the first version, some were slightly rephrased and one was dismissed. Twelve items from the IDB [

14] (see

Section 3.3) were added, plus four items from a

Compulsive behavioral style questionnaire, devised by the present author as part of the 1977-1980 investigation (not published). Five items were novel ones. Thus, this revised inventory counted 117 items. They had to be rated on the 5-point scale of the 1977-version. Five item clusters were specified in advance, this time with the pretense of being a real prediction indeed

5.2. Participants in the Second Sample

Colleague therapists in psychiatric hospitals and therapy practices all over the country were asked whether they treated patients and clients, whom they knew, or suspected, to suffer from obsessive-compulsive problems, either as a primary or comorbid disorder. If so, would these subjects be willing to complete the questionnaire? In return for their help, the therapists received a test report based on their patient’s scores. In this way, the scores of 105 patients were collected during about three years.

Limitation: In an unknown number of cases, there was only a suspicion of OCD instead of an independent diagnosis. In addition, there was no control group this time. However, because of the good discriminatory qualities of 93 of the 97 items used in the previous questionnaire (of which 92 were retained in the new one), the latter were trusted to distinguish patients with subclinical obsessive-compulsive symptoms from patients with clinical OCD.

5.3. Method

The resulting scores were analyzed some years later with the cluster optimization procedure based on item analysis, briefly described in

Section 4.4, but by means of a computer-program, this time. It will be further explained in

Section 5.5.

The five start clusters were close but not identical to the final clusters of the 1981-study because theoretical ideas asked for a few deviations. Apart from that, the 21 added (non-overlapping) items had to be added to the predicted clusters.

5.4. Results

The results have not been published in a paper devoted to OCD, but they were used in a paper that demonstrated the utility of the cluster optimization procedure [

18]. Its tables give an impression of the degree in which the final clusters deviated from the predicted five clusters in this more recent sample. However, they will not be shown in the present paper.

Instead, in

Section 6, the results of a test of a revised cluster prediction will be shown for both the previous and recent sample. The remainder of the present section is devoted to an explanation and justification of the renewed procedure of

predicted cluster optimization, further to be denoted as PCO.

5.5. PCO and Its Justification

When a pre-specified factor-structure (predicted on the basis of substantive considerations, or of a previous factor analysis) is to be evaluated psychometrically, it is customary to apply confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). CFA translates a predicted factor structure into a simplified inter-item covariance matrix. Subsequently, this matrix is adapted to the empirical covariance matrix, but restrained by the parameters that have been predicted (i.e., at least the items that define each factor and the number of factors; and additionally, factor correlations if predicted to be substantial). This is done in a number of iterations. It results in an implied covariance matrix. This latter matrix is compared with the empirical matrix, and the difference between the two is expressed in a value of chi-square, as well as in values of a number of GOF-indices. To accept the predicted model, chi square should show that the difference is insignificant (mostly, p < .05), and/or the values of the GOF-indices should be either smaller than a certain value (e.g. SRMR < .08), or higher (e.g., CFI > .95).

This is an

indirect way to test the item allocation to factors, and it is problematic in several respects, as Savelei [

19] showed. A major drawback is the following: If the scores of the sample have a poor reliability, then the covariance values in the empirical matrix will also be generally low. The converse will be true if the scores are reliable. However, in the first case, the difference between the empirical and implied matrix will be smaller than in the second case, resulting in a better chi-value and better GOF-values (Browne et al., 2002) [

20].

In 2007, Ilse Stuive published a thesis about the limitations of CFA in testing the goodness of fit of the factor structure in multidimensional tests [

21]. She compared it with a method she claimed to be based on the multiple group method of factor-analysis, advocated by Holzinger (1944) [

22].

4 Her comparison showed that the procedure she used often outperformed CFA, both in detecting erroneous item assignments (see also Stuive et al., 2008, [

24]), and in optimizing the subtests (see also Stuive et al., 2009 [

25]).

5

Her criticisms encouraged the present author to review a number of studies by statisticians, who had detected drawbacks in CFA (Prudon, 2015) [

26], and this review confirmed that the item-cluster correlation matrix is a better basis for testing and optimizing predicted clusters ‒ reason to program a highly iterative version of PCO [

18].

PCO’s output enables the investigator to evaluate the predictions on the level of individual items, but also globally by calculating goodness-of-fit (see

Section 4.6). This GOF-index is based on the number of hits (

H), proportional to the number of false positives (

F) and false negatives (

M, from

missing). In one index, already proposed in the 1981 study [

16], the hits are assigned a weight of 1, whereas the false positives and negatives get a value of -1. Therefore, it is called

AP(it): Accuracy of Prediction in terms of items.

H is corrected for hits by chance; hence, it runs from 1 (perfect prediction) to zero (prediction on chance level).

6

However, in the case of a substantial correlation between two clusters (if predicted!), the relocation of an item from its predicted cluster to the correlating cluster should not receive this maximal penalty. Therefore, a second GOF-index was devised, in which the weight of hits and prediction errors is dependent on the correlation of the items with the cluster concerned. This second GOF-index “punishes” smaller errors much less than larger ones. It is called

AP(icc): Accuracy of Prediction in terms of item-cluster correlations. It, too, runs from 1 to zero, after correction for hits by chance. Its “arithmetic behavior” under various conditions is shown in [

18] (in that publication's Appendix,

Table A1).

6. Evidence from Comparing the PCO-Results of both Samples

6.1. Participants

Before starting any analysis, the scores of the 105 participants were critically inspected because of the non-optimal way in which the participant’s OCD (diagnosis vs. suspicion; primary vs, secondary OCD) had been determined. To dismiss the non-OCD participants, a computer program was devised for the occasion, counting the numbers of each rating point per subject. Those with none or very few scale points of 4 and 5 were dismissed.

This held for ten participants. Besides, one rated participant had 9 missing values and was also dismissed. Thus, 94 questionnaires were left to be submitted to the analyses. This revised sample counted 78 patients, whose sex and age had been communicated. Of them, 68% were women with a mean age of 33.3 years (SD 10.9); the men had a mean age of 38.0 years (SD 13.6).

6.2. Prediction

For the present investigation, six clusters had been predicted because cluster 5 (precision compulsion) could be split into two strongly correlating, yet theoretically distinguishable sub-clusters (cl. 5 and cl. 6). The predicted clusters 1, 2, 3, and 4 differed somewhat from the corresponding final clusters in the first study [

16], not only by the inclusion of novel items, but also because of a more articulated theory

Being overly precise in a number of chores, which do not need such degree of precision; being troubled by incompleteness feelings about these; the ensuing checking, repeating, and stopping difficulties.

Remaining stuck in such behavior style for an extended time may strongly undermine one’s intuitive, experience-based behavior regulation. This gives rise to:

a) Experience of an impaired behavior regulation: pathological doubts before starting trivial and routine activities, trouble in perceiving the functionality of such routine activities within the task as a whole; trouble in feeling its distinctness from the subsequent activity; alienation from one’s immediate action environment.

b) Attempts to obviate this impaired behavior regulation: i) seeking surrogate criteria for completion of the activity and its successive parts (“proxies”: Liberman and Dar, 2009; Dar et al., 2021) [

29] [

30]; ii) ritualizing the affected parts; iii) trying to overcome stagnation in such activities by counting one’s acts, commanding oneself, counting or naming the objects that will typically be met in each step.

7

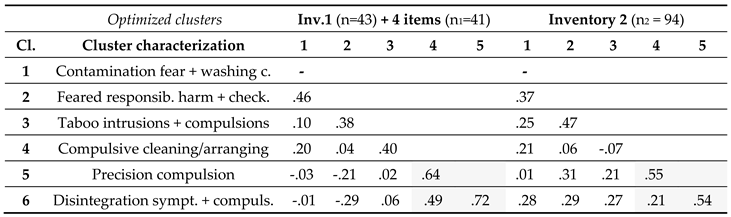

6.3. Testing the Six Clusters Prediction

These six clusters were tested and optimized on sample 1 (n=43), employing PCO. This led to some optimization, especially regarding the division between cluster 5 and 6. The results are not shown, except for the cluster correlations (in

Table 5, left side,

Section 6.5).

The cluster prediction for sample 2 (n=94) was tailored to the final, optimized one for sample 1, insofar as the items of both questionnaires overlapped. This overlap also included four items from the

Compulsive behavioral style questionnaire (see

Section 4.1), which had been rated by 41 of the 43 subjects of sample 1. Four items of the revised questionnaire were rejected in advance for different reasons. Six of its items were predicted to remain non-clustered because they applied to OCD in general. However, these items were allowed to enter the clusters; hence, they could appear to be false negatives in these clusters.

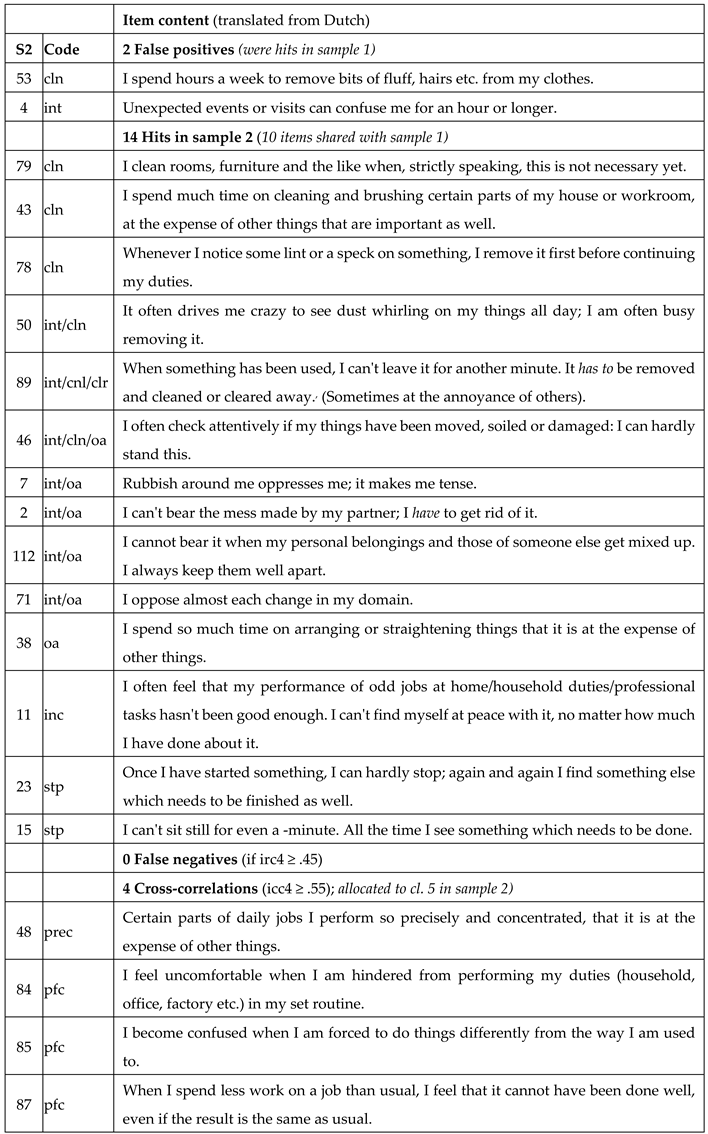

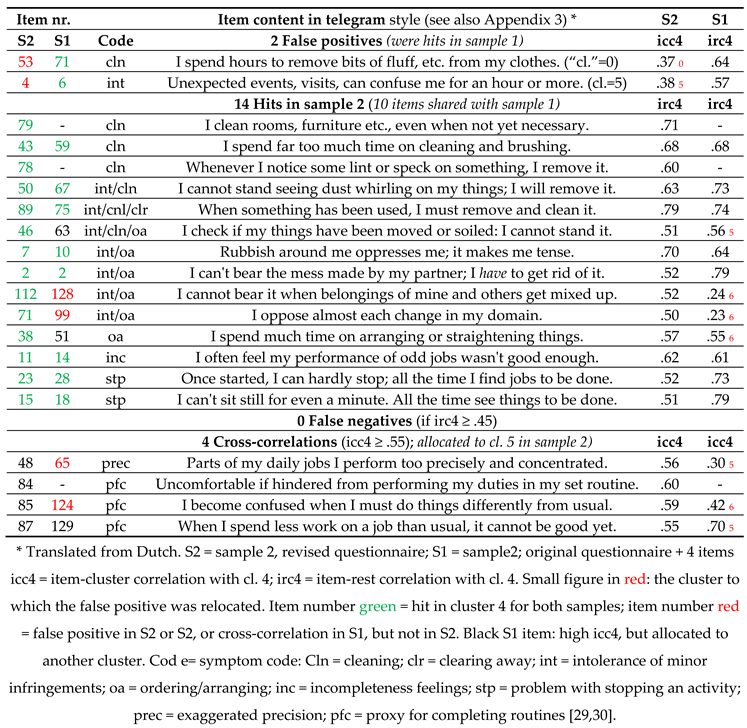

6.4. Results for sample 2

The quantitative results of the cluster optimization are reproduced in

Table 4.

The score distribution of twelve items appeared to be very skewed (SD < .95), yet they were retained to preserve their continuity with questionnaire 1, administered to sample 1. Cluster 2, particularly, would have suffered from their dismissal.

The AP(it)’s are poor for clusters 2 and 3, rather poor for cluster 5, rather good for cluster 1 and 6. However, the one for cluster 4 is good. The AP(icc)’s are mediocre for cluster 2, 3 and 5, rather good for cluster 1, good for cluster 6, and excellent for cluster 4.8

Cronbach’s alpha of the predicted clusters is poor for cluster 3, reasonable for cluster 5 and 6, but it is good for cluster 2 and 4, and excellent for cluster 1.

A serious deviation from the 1981-results (including those from the six cluster testing) was that three items, referring to checking of minor or unlikely risks, which had become part of cluster 5 in sample 1, had been relocated to cluster 2 in sample 2. In sample 1, they seemed to indicate incompleteness feelings about trivial routines, whereas in sample 2, they seemed attempts to deal with improbable or minor risks involved in the routines. This contributed much to their (rather) poor AP(it)s. However, the prediction of cluster 4, - central in the present paper - did quite well in sample 2, as it did in sample 1.

6.5. Results of Comparing the Results for both Samples

Table 5 shows the cluster correlations for the two samples. In sample 1, cluster 4, 5, and 6 have high inter-correlations, suggesting a common higher-order factor (impaired goal directedness), whereas, in sample 2, cluster 4 and 5, and 5 and 6, do have rather high correlations, but cluster 4 and 6 correlate only .21, suggesting a relative independence. In sample 1, cluster 4 correlated +.40 with cluster 3; in sample 2, however, they correlate -.07. Analyses with new, larger, and representative OCD-samples are needed for more definite, consistent results.

Table 5.

Correlations between the clusters in optimized form for the previous and the recent sample.

Table 5.

Correlations between the clusters in optimized form for the previous and the recent sample.

Table 6 shows which items remained or became part of cluster 4 at the end of the optimization procedure in both samples. Their comparison provides additional feedback:

Of the 16 predicted questionnaire-2 items of cluster 4, 14 ones are hits, printed in green in column S2. The other two are false positives (printed in red in column S2), but hits in sample1.

Of these 14 cl. 4-hits in questionnaire 2, 12 ones are shared with questionnaire 1, including the added item 128. Of these 12 shared items, eight are also hits in sample 1 (printed in column S1 in green).

Four hits in sample 2 are false positives in sample 1, two of them convincingly (printed in red in column S1), the two other ones arbitrarily (printed in black in column S1).

Two items of cluster 5 show high cross-correlations with cluster 4 in both sample 2 and 1 (printed in black in both columns S2 and S1); two items show high cross-correlations in sample 2 (printed in black in column S2), but not in sample 1 (printed in red in column S1).

6.6. Discussion

In sum, the results with both samples are not perfect, nor do they match perfectly, but enough to render some trust in the validity of the symptom cluster Tidying compulsion. The results endorse the inclusion of cleaning, clearing away, and ordering/arranging. (Scheduling items, however, had not been included in both questionnaires.)

Now, let us have a more qualitative look at the results by inspecting the codes of the hits and cross-correlations:

Seven of the fourteen hits in Sample 2 hint at intolerance of, or irritation about, any disruption of one’s perfectly clean and orderly domain (code=int). Of these hits, item 2, 46, 71, and 112 also attest of disharmony with the partner (or other housemates). The three remaining cleaning items, and the one remaining ordering/arranging item, merely speak of excess in the activities concerned, not of the coinciding or preceding emotions.

Sample 2 shares the “incompleteness feelings” item (hit 11), and the two “difficulty in stopping” items (hit 15 and 23) with sample 1 as hits (items 14, 18, and 28 respectively). These typical obsessive-compulsive peculiarities are the experiential side of a

continual negative feedback loop, driving the subjects to checking for completion, repeating, increased precision and concentration, and, eventually, turning to

proxies for completion [

29] [

30] (the items 84, 85, and 87 in the revised questionnaire).

7. Incidence of Tidying Compulsion

The last empirical question to be answered is: what is the relative incidence of tidying compulsion in the two samples? To answer this, three issues must be settled: 1) what kind of cluster score is suited for such a judgment; 2) how high must the cluster score be to count as indicating a grave obsessive-compulsive symptom cluster; 3) to compare both samples, on which clusters should the scores be based to become comparable: the predicted ones, the optimized (final) ones, or on perfectly corresponding ones (consisting of the shared hits only)?

7.1. Method

Issue 1: What kind of cluster score?

Sum scores on the clusters have not been used because clusters may have different sizes and subjects may have skipped one or more of the cluster’s items. Besides, for a gravity estimation of sum scores, they need to be compared with norm scores. These are not available for any OCD dimension in the presently used OCD-inventories.

That was a reason to use the mean item score per cluster per subject as cluster scores, that is, each subject’s sum score per cluster, divided by the number of rated items in that cluster. These have two advantages: 1) the resulting values have automatically been corrected for a subject’s missing values, if any; 2) such scores, in addition, allow for an intuitive impression of the gravity of suffering.

As to point 2: These scores roughly reflect the gravity of the corresponding scale point. For example, if a 5-point scale has been used, and the scores have been rounded off to one decimal place9 scale point, then all cluster scores for each subject would theoretically range from 1.0 to 5.0. This holds when all items have been optimally formulated and the sample is large and heterogeneous (or includes a number of non-clinical subjects as well). In clusters with a high number of items, this correspondence will be somewhat attenuated because not every item of the cluster will apply equally to the subject involved. However, when the range of scores in a sample starts far above 1.0 and/or stops far under the 5.0, then the sample and/or item selection had been suboptimal.

Issue 2: Which value of such cluster scores would represent the cutting point between subclinical and clinical scores?

A decision about the cutting point allows one to count the number of subjects in the sample scoring above it, implying that they suffer from a fairly to severely grave degree of tidying compulsion. Its proportion in the whole sample can be considered as its incidence in the sample. Such decision will always be arbitrary, so it must be kept pragmatic. In this case, it was chosen to be 70% of the maximum score of 5, that is, 3.5, even if the range will start somewhat above 1.0 and end below 5.0, what is likely In these small, clinical samples. (In larger samples, 70% of the maximum cluster score could be considered.)

Issue 3: Which clusters should be considered the ones to be the compared: the predicted ones, the final ones, or the shared hits of the final ones?

In this study, the optimized final clusters still differed much from the predicted ones. That is a reason prefer the final ones above the predicted ones, which may be suspected of an insufficient validity. However, the final clusters in both samples show several differences.

Using the shared hits did not seem an adequate solution either because sample 2 was investigated almost 30 years after sample 1. During that period, life circumstances, traditions, norms, economic conditions, gender differences and role division have considerably changed. Consequently, a part of the shared hits may have assumed a different meaning for the later generation.

On the other hand, the optimization process may have given the differences between two generations a chance to co-affect the final clusters. There will be non-overlapping items in the corresponding final clusters, but the resulting not-identical clusters may well be more representative of what they should measure, instead of less! That is, tidying compulsion in the years 1976-1979 differs from tidying in the years 2004-2007 somewhat in behavior details, but both still represent tidying compulsion! The same may hold for the other five clusters may hold

Therefore, to compare the cluster scores of both samples, the full final clusters were eventually preferred.

7.2. Results

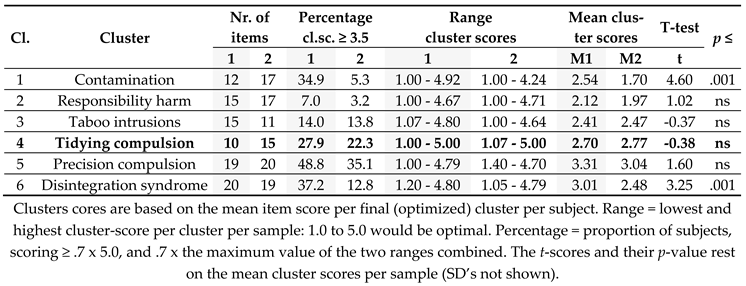

Clusters cores are based on the mean item score per final (optimized) cluster per subject. Range = lowest and highest cluster-score per cluster per sample: 1.0 to 5.0 would be optimal. Percentage = proportion of subjects, scoring ≥ .7 x 5.0, and .7 x the maximum value of the two ranges combined. The t-scores and their p-value rest on the mean cluster scores per sample (SD’s not shown).

Cluster 4 has the best range of cluster scores in both samples, and its proportion of scores ≥ 3.5 is substantial (around 25%). This incidence is higher than those of cluster 2 and 3 in sample 1, and higher than those of cluster 1, 2, 3 and 6 in sample 2. The mean cluster-4 scores of both samples are almost equal.

Incidentally: Note the extremely low incidence of cluster 2 in sample 2: 3.2% of the subjects have score ≥ 3.5, probably due to the way the subjects were recruited. This extreme skewness of the scores detracts from the validity of the final cluster 2 in sample 2. The clusters 2 and 5 are not comparable between sample 1 and 2 because, in sample 2, three checking items (very common in OCD) moved from cluster 5 to cluster 2. Cluster 1 has a low score too, in sample 2; however, that did not distract from its AP’s: these were much better than those of cluster 2 (see

Table 4).

8. General Discussion and Conclusion

8.1. The Discussed Studies and Their Limitations

Empirical evidence for the existence and composition of a tidying compulsion cluster can only be provided by studies using a valid OCD questionnaire or a semi-structured interview, containing items referring to the relevant symptoms. The only

internationally known questionnaire containing such items is the LOI [

3]. However, only a few studies used the LOI (discussed in

Section 2) and these, unfortunately, had not explicitly inquired into the existence of such a cluster. In addition, most of these studies had been based on samples which contained only or mainly non-clinical subjects.

However, in one study [

14], 22 LOI-item were included in a novel OCD questionnaire of 32 items. It was administered to 43 OCD patients. Factor analysis on the scores identified a cluster which included various tidying items. It discriminated well between the clinical and two non-clinical samples. (

Section 2.3). A limitation was the small sample size

Another Dutch study[

16] (

Section 3) ‒ by the present author ‒ with a then novel OCD-questionnaire of (eventually) 97 items had explicitly been undertaken to establish and map out OCD’s heterogeneity, among which tidying compulsion. This cluster was confirmed, and all of its items except one discriminated well between the OCD-sample and a non-clinical sample. However, again, the sample size was small (n=43).

For later studies (

Section 4), the present author had recruited 105 patients, to whom a revised version of the above-mentioned OCD questionnaire was administered. The scores were analyzed and validated by a novel procedure,

Predicted Cluster Optimization (PCO)

, explained and defended in

Section 5.5 and in [

18]. It confirmed the hypothesized existence and composition of tidying compulsion, and it agreed well with the one confirmed on the first sample, mentioned above. However, in a later study of the present author, there were reasons to doubt the OCD-diagnosis of

eleven of the patients.

In the present study (

Section 6 and 7), these

eleven subjects were expelled from the sample. In that study, cluster 5 was split into two connected sub-clusters for theoretical reasons. The resulting

six clusters were first optimized by applying PCO to sample 1. Subsequently, the prediction of the six cluster in sample 2 was tailored to the optimized one in sample 1. Its test with PCO on sample 2 (

Section 6) resulted in a picture, which was somewhat at odds with the prediction. Yet, the tidying compulsion cluster was confirmed again.

Section 7, finally, was devoted to the incidence of tidying compulsion in both samples. To estimate this incidence, it was unavoidable to make a series of arbitrary but defensible decisions to arrive at a cutting-point between clinical and subclinical cluster scores. In the case of tidying compulsion, the percentage of subjects scoring above this cutting point was slightly more than 25% in sample 1, and slightly beneath 25% in sample 2, despite these samples having been recruited almost 30 years apart. (In samples with a proportion of women near 50%, rather than 70%, a lower percentage may be found.)

8.2. Issues Concerning the Questionnaires

Researchers may question the huge number of items in both questionnaires. However, the questionnaires were meant to map out OCD’s heterogeneity, not to provide an instrument for a quick screening. In addition, even these days, let alone in 1981 and 2004, there is still much uncertainty about what should be the number of OCD symptom-clusters and their composition. For that reason, a heterogeneous and large collection of items was and still is essential. Once, OCD will be better understood, it is time to reduce the number of items.

Another issue is: certain items in both questionnaires may not be optimal, that is, they may be too similar, too long, too complex. Or they contain proverbs and sayings, unfamiliar to people for whom the language employed is a second one. Therefore, researchers, interested in using items from these questionnaires, should feel free to adjust such suboptimal items and to delete redundant ones.

8.3. Conclusion and Future Directions

In all, despite the several limitations mentioned above, the discussed studies argue for the existence of a tidying compulsion symptom cluster in the hypothesized composition. The evidence presented is too modest to convince everyone, but strong enough to warrant further research.

This research should be done with questionnaires or structured interviews, containing the relevant items. The cleaning items should be formulated in such a way, that it will be clear to the user that they refer to a domestic job, rather than to contamination concerns. (For examples of such items, see the Appendic. For the third version of the author’s OCD questionnaire, contact the author.10)

How to analyze the scores involved? A moderate to high correlation between some of the clusters is to be expected, as well as substantial cross-correlations between some of the items. This implies that the

common factor model is

not suitable. Accordingly, when executing

explorative studies, principal component analysis with oblique rotation, or explorative structural equation modeling (ESEM) [

31], should be the method of choice, not common factor analysis.

If the clusters (factors) have been predicted beforehand, then those applying CFA should likewise predict the factor correlations and the cross-correlations, they should be left free to estimate by the CFA program. As an alternative, I can recommend a try with PCO.11

Another question to be settled empirically is: What does the high correlation between tidying compulsion and precision compulsion prove? Here, it was depicted as evidence that tidying compulsion is a genuine OCD. However, critics may claim that it is merely a facet of precision compulsion. If they are right, then tidying compulsion items should have been included in other OCD-inventories, and these tidying items should have become part of those symptom dimensions in these OCD-inventories that resemble the cluster Precision compulsion as depicted in the present paper.

The following inventories and dimension were inspected: OCI:

Ordering [

32]; Padua Inventory Revised:

Precision [

33]; VOCI:

Just right [

34], SOAQ: S

ymmetry/Ordering/Arranging [

35]; Dimensional Y-BOC:

Dimension 3 [

36]; DOCS:

Category 4 [

37]. None of these subscales contain domestic cleaning compulsion items. Thus, this question cannot yet be settled. Incidentally, the OCD-inventory scales mentioned above do show much difference in composition.

8.4. Other Issues That Merit Further Investigation

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

For the scores of the two samples on the OCD-questionnaire, and the full text of the second, revised OCD-questionnaires, and a third, revised one, please e-mail the author. When intending using the latter in one’s research, feel free to adjust presumably suboptimal items.

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr. Fred Penzel for his permission to cite from the case vignette he included in his online article (see Section 2.1). [11].

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The items printed in gray had already a short formulation.

Code =symptom code (facet):

cln =cleaning;

clr =clearing away;

int =intolerance of minor infringements;

oa =ordering/arranging;

inc=incompleteness feelings;

stp =problem with stopping an activity;

prec = exaggerated precision;

pfc =proxy for completing routines.

Appendix 1: The LOI-items referring to excessive cleaning and/or tidying

A) The LOI-items referring to excessive cleaning and/or tidying

Both hygienic and domestic

8. Do you hate dirt and dirty things?

16. Do you tend to worry a bit about personal cleanliness or tidiness?

17. Are you fussy about keeping your hands clean? *

Clothes-related

18. Do you ever wash and iron clothes when they are not obviously dirty in order to keep them extra clean and fresh?

19. Do you take care that the clothes you are wearing are always clean and neat, whatever you are doing?

Domestic

22. Are you very strict about keeping the house always very clean and tidy?

23. Do you dislike having a room untidy or not quite clean for even a short time?

24. Do you sometimes get angry that children spoil your nice clean and tidy rooms?

27. If you notice any bits or specks on the floor or furniture do you have to remove them at once before you are due to clean round?

28. Do you ever clean or dust the rooms that haven't had time to get dirty, just to make sure that they are really clean?

29. Do you ever have to dust, sweep, or wash things over again several times just to make sure they are really clean?

50. (Trait item) Do you regard cleanliness as a virtue in itself?

B) The LOI-items referring to excessive orderliness in space and time

Ordering and arranging (personal)

20. Do you like to put your personal belongings in set places or patterns?

21. Do you take great care in hanging and folding your clothes at night?

Ordering and arranging (domestic)

25. Do you like furniture or ornaments to be in exactly the same place always?

26. Do your easy chairs have cushions which you like to keep exactly in position?

58. (Trait item) Do you try to avoid changes in your house or work or in the way you do things?**

Scheduling

30. Do you have to keep to strict timetables or routines for doing ordinary things?

32. Do you get a bit upset if you cannot do your (house)work at set times or in a certain order?

64. (Trait item) Are you very systematic and methodical in your daily life?

67. (Trait item) Do you like to have set times or orders for doing your household jobs or work, as the case may be? ***

| Appendix 1 |

The LOI-items referring to excessive cleaning and/or tidying |

| Derived from |

Cooper, J. (1970). The Leyton Obsessional Inventory. [ 3] |

Legend:

The above category labels and assignment of the items to them are not Cooper’s, but stem from the present author.

* This item could readily also reflect contamination anxiety.

** This item applies to both “Ordering and arranging (domestic)” and “Scheduling”

*** This item was reformulated to cover both the “female” and “male” variant in the same item.

Appendix 2: Full formulation of the items in Table 2

Table A1.

Characteristic of the tidying compulsion cluster in the 1981-study (n=43).

Table A1.

Characteristic of the tidying compulsion cluster in the 1981-study (n=43).

Appendix 3: Full formulation of the items in Table 6

Table A2.

Feedback about the items of cluster 4 for sample 2 (n= 94) and sample 1 (n=43); six cluster tests.

Table A2.

Feedback about the items of cluster 4 for sample 2 (n= 94) and sample 1 (n=43); six cluster tests.

Notes

| 1 |

Dr. Gijs Bleijenberg, behavior therapist and researcher at Medical psychology of the University of Nijmegen. |

| 2 |

Not to be confused with the one, based on item-response theory. |

| 3 |

The questionnaire was approved as a valid test by the COTAN (Committee for Test Affairs in the Netherlands) in 1982, and documented in Evers et al. (2000, p. 555). [ 17]. |

| 4 |

Erroneously (see [ 18]): her method, in essence, was item analysis in line with classical test theory (see Section 4.4). Holzinger’s method, in contrast, remained factor-analytic throughout, and so did the variant by Thurstone (1945) [ 23] [ 18]. (Their methods anticipated CFA.). |

| 5 |

The latter is based on the so-called modification indices per parameter. These indices show to what extent CFA’s GOF-indices would adopt a better value by modifying the prediction (in this case, the assignment of the items to the factors).. |

| 6 |

Theoretically, its value can become slightly negative. |

| 7 |

See Reed (1968) [ 27] for interview fragments, attesting to this pathology, and Von Gebsattel (1938) [ 28] for an in-depth phenomenological analysis of such an impaired behavior regulation. |

| 8 |

This evaluation of the AP’s is, of course, still crude and speculative. |

| 9 |

No more, no less: this will be enough for most questionnaires. Only to clusters with an unusually high number of items, one decimal may do insufficient justice. |

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

A version of the program, rewritten in R by a colleague, will soon be available. |

References

- Tallis, F. (1996). Compulsive washing in the absence of phobic and illness anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 361-362. [CrossRef]

- Summerfeldt, L.J. (2004). Understanding and treating incompleteness in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 60(11), 1155–1168 . [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J. (1970). The Leyton Obsessional Inventory. Psychological Medicine, 1, 48-64. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J., and McNeil, J. (1968). A study of house-proud housewives and their interaction with their children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines,9, 173-188. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J. and Kelleher, M. (1973). The Leyton Obsessional Inventory: a principal components analysis on normal subjects. Psychological Medicine, 3(2), 204-208. [CrossRef]

- Van Boekel, G. & Meulendijk, P. (1976). Precisiedwang - een laatste bestaansmogelijkheid. (Precision compulsion - a last-ditch way of being). Thesis: University of Nijmegen (The Netherlands).

- De Bruyn, J, (1980). Dwangneurose, een gevecht tegen onzekerheid. Docto¬ral thesis, University of Nijmegen. (Obsessive-compulsive neurosis, a struggle with uncertainty.).

- Hoogduin, C.A.L., Haan, E. de, Hoogduin, W.A., Hartman-Faber, S.H., & Markveldt, R. (1981). Over de behandeling van huishouddwang: toepassing van zelfcontrole-procedures in een relationele context. Kwartaalschrift voor Directieve Therapie & Hypnose. 1(3), 258-269. (About the treatment of running the home compulsion …).

- De Sirow, W. (2013). Putzzwang als Erscheinungsform der Zwangsstörung. Praktische Betrachtungen. München: Grin Verlag. https://www.grin.com/document/265320 (Cleaning compulsion as manifestation of OCD: Practical considerations).

- Oczko, P. (2020). Bezem & Kruis: De Hollandse schoonmaakcultuur of de geschiedenis van een obsessie. (Broom and Cross; The Culture of Cleanliness in Holland, or the History of an Obsession.) Leiden: Primavera Pers. Translation from the originally Polis version (Krakau, 2003), adapted for the Netherlands.

- Penzel, F. (1998). How clean is clean? OCD Newsletter, 12(4). Direct access via: http://www.wsps.info./index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=36%3Aocd-and-related-subjects-by-frederick-penzel-phd&Itemid=64&layout=default&limitstart=20.

- Murray, R.M., Cooper. J.E. & Smith. A. (1979). The Leyton Obsessional Inventory: an analysis of the responses of 73 obsessional patients. Psychological Medicine, 9, 305-311. [CrossRef]

- Wellen, D., Samuels, J., Bienvenu, O.J., Grados, M., Cullen,B., Riddle, M., Liang, K-Y., & Nestadt, G.. (2007). Utility of the Leyton Obsessional Inventory to distinguish OCD and OCPD. Depression and Anxiety 24:301–306. [CrossRef]

- Kraaimaat, F.W. & Van Dam-Baggen (1976). Ontwikkeling van een zelfbeoordelingslijst voor obsessief-compulsief gedrag). Nederlands Tijdschrift voor de Psychologie, 3, 1, 201-211. (Development of a self-rating inventory for obsessive-compulsive behavior).

- Stouthard, M.E.A. (2006). Analyse van tests. In: Brink, W.P. van den Brink and Mellenbergh, G.J. (2006). Testleer en testconstructie (pp. 341-376). Amsterdam: Boom. (Analysis of tests; in: Test theory and test designing).

- Prudon, P.C.H. (1981). The heterogeneity of obsessive-compulsive neurosis: a cluster-analytic study. Internal report 81KL01, Radboud University of Nijmegen. http://home.kpn.nl/p.prudon/Internalreport.pdf.

- Evers, A., Van Vliet-Mulder, J.C., & Groot, C.J. (2000). Documentatie van Tests en Testresearch in Nederland. Deel 1: Testbeschrijvingen. Assen: Van Gorcum.

- Prudon, P. (2016). Testing predicted clusters: A new approach to this powerful research tool, illustrated through a questionnaire on obsessive–compulsive disorder. Comprehensive Psychology 5: 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Browne, M. W., MacCallum, R. C., Kim, C-T., Andersen, B. L., & Glaser, R. (2002) When fit indices and residuals are incompatible. Psychological Methods, 7, 403-421.

- 20. Victoria Savalei (2012): The Relationship Between RMSEA and Model Misspecification in CFA Models. Educational and Psychological Measurement 72(6):910-932. [CrossRef]

- Stuive, I. (2007). A comparison of confirmatory factor analysis methods. Oblique multiple group method versus confirmatory common factor method. Dissertation, University of Groningen, The Netherlands. http://irs.ub.rug.nl/ppn/305281992.

- Holzinger, K. J. (1944). A simple method of factor analysis. Psychometrika 9(4): 257–262.

- 23. Google Scholar | Crossref.

- Thurstone, L.L. (1945). A multiple group method of factoring the correlation matrix. Psychometrika, 10 (2), 73-78.

- Stuive, I. Kiers, H.A.L., Timmermans, M,. Berge, J.M.F. ten (2008). The empirical verification of an assignment of items to subtests. the Oblique Multiple Group method versus the Confirmatory Common Factor method. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 68, 6, 923-939.

- Stuive, I. Kiers, H.A.L,. Timmermans, M. (2009). Comparison of methods for adjusting incorrect assignments of items to subtests. Oblique multiple group method versus confirmatory common factor method. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69 (6), 948-965.

- Prudon, P. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis as a tool in research using questionnaires: A critique. Comprehensive Psychology 4(1): 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Reed, G.F. (1968): Some formal qualities of obsessional thinking. Psychiatrica Clinica, 1, 382-392.

- Von Gebsattel, V.E. (1938). Die Welt des Zwangskranken. Monatschrift für Psychiatrie und Neurolo¬gie, 99, 10-74. Translated and abridged as:T he world of the compulsive. In R. May, E. Angel, & H.F. Ellenberg, eds. (1958). Existence: A new dimension in psychiatry and neurology. New York: Basic Books.

- 30. Liberman, N, & Dar, R. (2009). Normal and pathological consequences of encountering difficulties in monitoring progress toward goals. In: G.B. Moskowitz and H. Grant (Eds). The psychology of goals. New York: Guilford, p. 277-303. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-02739-000.

- Dar, R., Lazarov,A., & Liberman, N. (2021). Seeking proxies for internal states (SPIS): Towards a novel model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 103987, ISSN 0005-7967, . [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., Guo, J., Dicke, T., Parker, P. D., Craven, R. G. (2020). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM) & Set-ESEM: Optimal balance between goodness of fit and parsimony. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 55(1):102-119. Epub 2019 Jun 17. [CrossRef]

- Foa, E.B., Kozak, M.J., Salkovskis, P.M., Coles, M., & Amir, N. (1998). The validation of a new obsessive–compulsive disorder scale: The Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 10(3), 206-214. [CrossRef]

- Van Oppen, P. Hoekstra, R. J., Emmelkamp, P.M.G. (1995). The structure of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(1), 15-23. [CrossRef]

- Thordarson, D.S., Radomsky, A.S., Rachman, S., Shafran R, Sawchuk CN, Ralph Hakstian A. (2004). The Vancouver Obsessional Compulsive Inventory (VOCI). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 1289-1314. [CrossRef]

- Radomsky, A.S. & Rachman, S.J. (2004). Symmetry, ordering and arranging behaviour. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42(8), 893–913. [CrossRef]

- Rosario-Campos, M.C., EC Miguel. E.C., Quatrano, S......, Leckman, J.F. (2006). The Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DY-BOCS): An instrument for assessing obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions. Molecular Psychiatry, 0, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz, J.S., Deacon, B.J., Olatunji, B.O., Wheaton, M.G., Berman, N.C., Losardo, D., Timpano, K.R., McGrath, P.B., Riemann, B.C., Adams, T., Björgvinsson, T., Storch, E.A., Hale, .LR. (2010). Assessment of obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions: development and evaluation of the Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. Psychological Assessment, 22(1): 180-98. [CrossRef]

- Cervin, M., McNeel, M.M., Wilhelm, S., McGuire, J.F., Murphy, T.K., Small, B.J. , Geller, D.A. , & Storch, E.A. (2021). Cognitive Beliefs Across the Symptom Dimensions of Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Type of Symptom Matters, Behavior Therapy (2021), . [CrossRef]

- Iniesta-Sepulveda, M., Rosa-Alcazar, A.I., Rosa-Alcazar, A., Storch, E.A. (2014). Evidence-Based Assessment in Children and Adolescents with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Journal of Child and Family Studies ·. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Composition of the factor “Structuring of environment and behavior” in the IDB.

Table 1.

Composition of the factor “Structuring of environment and behavior” in the IDB.

| LOI |

IDB |

Code |

Items (translated from Dutch) |

Ld. |

| |

|

|

Structuring one’s environment (adhering to a clean, orderly domain) |

|

| 27 |

10 |

cln |

If I notice any bit or speck, I first remove that before I continue my activities. |

.59 |

| -- |

2 |

cln/oa |

The thought occurs to me that my house is not clean and tidy. |

.43 |

| 25 |

14 |

oa |

I dislike it when furniture, lamps and the like are out of their set place. |

.58 |

| -- |

25 |

int |

I fret about tiny damages to my properties (e.g., little holes, stains, scratches) |

.59 |

| |

|

|

Structuring one’s behavior (including scheduling activities) |

|

| 67 |

19 |

sch |

I perform the daily routines in an order determined by myself. |

.82 |

| 32 |

32 |

sch |

I feel uncomfortable when hindered from performing my duties in a fixed order. |

.75 |

| 32 |

9 |

sch |

I feel uncomfortable when prevented from performing my duties at set times |

.73 |

| -- |

12 |

sch |

I perform my daily jobs according to a fixed time schedule of my own making. |

.61 |

| 31 |

6 |

ritual |

I stick to a fixed order in dressing or undressing, washing or bathing, etc., |

.77 |

| -- |

1 |

prec |

I perform the daily routines in a conscientious and precise way. |

.40 |

| IDB=item numbers in the IDB. LOI=corresponding item numbers in the LOI. Ld.=factor loadings. Code=codes, characterizing the symptom: cln=cleaning; oa=ordering/arranging; int=intolerance for minor infringements; sch=scheduling; ritual=ritualization of daily routines; prec=exaggerated precision. |

Table 2.

Characteristic of the tidying compulsion cluster in the 1981-study [

16], in a logical order.

Table 2.

Characteristic of the tidying compulsion cluster in the 1981-study [

16], in a logical order.

| Item |

Code |

Item content in telegram style ** |

icc4 |

| 59 |

cln |

I spend much time on cleaning and brushing, at the expense of other things. |

.66 |

| 67 |

cln |

I cannot stand seeing dust whirling on my things; I will remove it. |

.73 |

| 71 |

cln |

I spend hours a week to remove bits of fluff, hairs etc. from my clothes. |

.67 |

| 75 |

clr |

When something has been used, I must remove it and clear it away. |

.75 |

| 51 |

oa |

I spend much time on arranging things, at the expense of other things. |

.58 |

| 2*** |

int |

I can't bear the mess made by my partner. I have to get rid of it. |

.66 |

| 6 |

int |

Unexpected events or visits can confuse me for an hour or more. |

.61 |

| 10 |

int |

Rubbish around me oppresses me; it makes me tense. |

.62 |

| 63 |

int |

I check if my things have been moved or soiled: I cannot stand it. |

.58 |

| 14 |

inc |

I feel my performance of chores and jobs hasn't been good enough. |

.59 |

| 18 |

stp |

I can't sit still for even a minute. All the time see things to be done. |

.82 |

| 28 |

stp |

Once started, I can hardly stop; again and again I find something else to do. |

.71 |

| |

|

Cross-correlating items ≥.55 (from cluster 5) |

|

| 40 |

inc |

I often feel my activities have not yet been completed, against my judgment. |

.69 |

| 36 |

inc |

While performing jobs, I often feel I have forgotten or skipped something. |

.66 |

| 73 |

chk |

When I have finished a job, I always have to check the result. |

.59 |

| * Recalculated for the full sample (n=43) with a contemporary program. ** Translated from Dutch. For the full formulation, see Appendix 2. *** Item 2 did not discriminate between the patient and the non-clinical sample, the other items did. Legend: Item=item number; icc4=item-cluster correlation with cl. 4. Code = item characterization: cln=cleaning; clr=clearing away; oa=ordering/arranging; int=intolerance of minor infringements on one’s tidy domain; inc=incompleteness feelings; stp=difficulty in stopping; chk=checking for incompleteness. |

Table 3.

Correlations between the clusters (n=.43).

Table 3.

Correlations between the clusters (n=.43).

| Cl. |

Label (abridged) |

Alpha |

Cl. 1 |

Cl. 2 |

Cl. 3 |

Cl. 4 |

| 1 |

Contamination anxiety |

.95 |

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

Fear of harming |

.92 |

.45 |

|

|

|

| 3 |

Obsessions |

.91 |

.14 |

.39 |

|

|

| 4 |

Tidying compulsion |

.92 |

.17 |

-.02 |

.37 |

|

| 5 |

Precision compulsion |

.95 |

.00 |

-.26 |

.03 |

.63 |

Table 4.

Optimization six cluster prediction for the DVL-2, recent sample (n2=94).

Table 4.

Optimization six cluster prediction for the DVL-2, recent sample (n2=94).

| Cl. |

Cluster characterization |

Cp |

H |

F |

M |

Cf |

AP |

Cohesion |

Alpha |

| rej. |

Ruled out items |

4 |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

(it) |

(icc) |

pred. |

final |

pred. |

final |

| 0 |

Non-clustered items |

6 |

5 |

1 |

9 |

14 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| v1 |

Contamination fear |

13 |

13 |

0 |

4 |

17 |

.86 |

.86 |

.47 |

.46 |

.92 |

.94 |

| 2 |

Feared responsibility harm |

17 |

12 |

5 |

5 |

17 |

.65 |

.77 |

.35 |

.34 |

.90 |

.90 |

| 3 |

Taboo intrusions |

17 |

10 |

7 |

1 |

11 |

.69 |

.81 |

.23 |

.32 |

.83 |

.84 |

| 4 |

Tidying compulsion |

16 |

14 |

2 |

1 |

15 |

.89 |

.94 |

.36 |

.38 |

.90 |

.90 |

| 5 |

Precision compulsion |

21 |

16 |

5 |

4 |

20 |

.73 |

.79 |

.26 |

.32 |

.88 |

.90 |

| 6 |

Disintegration syndrome |

23 |

18 |

5 |

1 |

19 |

.83 |

.89 |

.26 |

.32 |

.89 |

.90 |

| |

Sum |

107 |

83 |

24 |

16 |

99 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cp; size predicted cluster; H, F, M: number of hits, false positives, and false negatives, respectively; Cf=size final cluster. AP(it): Accuracy of prediction in terms of items; AP(icc): ditto in terms of item-cluster correlations). Cohesion: inter=item correlations per cluster. Pred. = predicted, final = final, statistically optimized cluster. Alpha.pred.: Alpha of the predicted cluster; Alpha final: Alpha of the final cluster. |

Table 6.

Feedback about the items of cluster 4 for sample 2 (n= 94) and sample 1 (n=43); six cluster tests.

Table 6.

Feedback about the items of cluster 4 for sample 2 (n= 94) and sample 1 (n=43); six cluster tests.

Table 7.

Incidence of the final clusters in both samples (n1 = 43; n2 = 94).

Table 7.

Incidence of the final clusters in both samples (n1 = 43; n2 = 94).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).