1. Introduction

With its 8300 km of coastline and about 16 million residents in coastal municipalities, Italy is significantly exposed and vulnerable to tsunami risk. Tsunami are little-known events but nonetheless they are likely to occur, as shown by a number of major events that have occurred in historical times, including the Reggio Calabria - Messina earthquake of December 28, 1908, which triggered a tsunami with waves up to 11 meters high [

1,

2]. More recently, other tsunami event occurred in Stromboli on December 30th, 2002, following a volcanic eruption. Advances in scientific knowledge about the sources capable of generating tsunamis, tsunami modeling with high-performance computational systems, and early warning systems have certainly improved the prediction and management capabilities of this type of event [

3]. In particular, historical and geophysical analyses have highlighted the different risk exposure of Italian coastal slopes and the particular probability distribution function of this type of phenomena: major events such as the Crete tsunami of 365 AD, which destroyed Alexandria, Egypt, or the one that struck Naples in 1348, described by Francis Petrarch [

4,

5,

6,

7] have a low probability of occurrence, while smaller but potentially locally destructive tsunamis, such as the five events that struck the Eastern Aegean between 2017 and 2021 [

8,

9] have a much higher probability of occurrence.

However, the advancement of scientific knowledge does not automatically turn into viable knowledge for vulnerable populations, which is instead recognized as an important predictor of preparedness and thus the effectiveness of risk mitigation measures [

9,

10,

11,

12]. In the areas most exposed to tsunami risk (particularly along the Pacific coasts and in some areas of the Indian Ocean) traditional forms of knowledge about this type of phenomena, generally based on the memory of past events, are integrated into local cultures and preserved through written documents, orally passed down stories, and accounts from direct witnesses, representing a powerful factor in communities’ adaptation to this type of event [

13,

14,

15]. The case best known to the scientific community concerns the island of Simeulue in Indonesia. Despite its proximity to Banda Aceh, one of the areas most affected by the impact of the 2004 Sumatra tsunami, and direct exposure to tsunami waves with run-up more than 30m, very few casualties have been reported. Subsequent research showed that traditional knowledge of tsunamis, conveyed through a folk song, had enabled the inhabitants to understand the danger and come to safety [

16].

In the Euro-Mediterranean area due to their long return times, tsunamis are a virtually unknown phenomenon, of which little historical and cultural evidence remains.

In this respect, authors have found only two exceptions: the case of the Lynden Fjord and the Åknes fjord area, both on the west coast of Norway and the Reggio Calabria - Messina area, being selected as a case study for the here presented paper.

Some Norwegian fjords are prone to rockslide tsunamis and there have been several events in the area in the relatively recent past, in 1905, 1934 and 1936, respectively, which claimed 174 lives [

17]. In these areas, the historical memory of past tsunamis together with scientific advice and operational Early Warning Systems has resulted in an enhanced tsunami risk perception [

18,

19].

The case study dealt with in this paper concerns the area affected by the Reggio Calabria Messina tsunami of 28th December 1908, in which systematic research on risk perception has never been carried out, which, hypothetically, may reveal evidence of great interest on the historical memory of disasters and risk communication.

The present work is a part of a larger research on tsunami risk perception on Italian coasts, partially funded by the Department of Civil Protection [

20,

21] being precisely focusing on socio-demographic and geographical factors that may potentially affect tsunami risk perception along with forms and sources of knowledge about the nature, magnitude and danger posed by such phenomena. The whole research relies on questionnaire survey (CATI) that considered a sample of 5,842 respondents, residing in 450 coastal municipalities located in 8 Italian regions. A sub-sample of 1999 interviewees in 193 municipalities of Sicily and Calabria were extracted from the national sample, providing an effective snapshot of the areas affected by the physical effects of the after mentioned Reggio Calabria and Messina earthquake and tsunami as well as of their surroundings, where tsunami has not left documented traces of its impacts.

Data revealed interesting differences, which not only return different representations of the phenomenon and its effects, but also different ways to approach available sources of knowledge. Although the “national” sample is overshadowed by a strong tendency to identify the tsunami as a catastrophic and unpredictable phenomenon, also highlighting a strong influence of media images of the great tsunamis of Sumatra in 2004, northern Japan in 2011, in the area hit by the Reggio Calabria and Messina tsunami, a more realistic reading of the phenomenon and its effects prevails, being appearing linked to a concrete and socially shared historical memory of the event. Some of the research data will be briefly presented in the report, discussing the implications on science and risk communication strategies, forecasting and prevention activities, and possible future developments of the research.

1.1. Tsunami hazard in the Mediterranean area and Italian Coast

Scientific studies on tsunamis, in recent decades, experienced rapid progress. The evolution of seismic and sea-level detection tools connected through broadband networks to high-performance computers make it possible to process large volumes of data in a very short time and to rapidly create models for estimating the impacts of a tsunami on coastlines [

23,

24,

25]. In addition, in recent years, the use of supercomputers for High Performance Computing (HPC), allowed the development of detailed models of tsunami hazard estimation at the local, basin, and global levels by simultaneously examining a very large number of variables [

26,

27,

28]. These computations allow researchers to go beyond hazard estimation by assessing in detail the impact that a tsunami may produce on the coast to define inundation zones and mitigate the effects on the most vulnerable structures and the population [

3,

16,

29].

The Mediterranean Sea has a high tsunami hazard and the Italian peninsula is located in the center of the basin. Both the position of a nation and the esti-mated hazard for it are affected by the variability of factors such as the exponential in-crease, in recent years, of human settlements along the Mediterranean coasts (exposure) and the strong uncertainty related to tsunami hazard assessment. These characteristics complicate the study of tsunami risk, as it that takes into account the combination of these variables. After World War II, the Mediterranean coasts have experienced extensive urbanization, and many industrial facilities, for organizational convenience, grew up on or very close to the coasts [

30]. Cities such as Alexandria, Athens, Izmir, Tripoli, Tunis, Algiers, Barcelona, Marseille, Naples, or Zadar, rise on the Mediterranean coasts and are exposed to tsunami risk. Throughout history, the Mediterranean coasts have been affected by many tsunamis - mostly generated by high-magnitude earthquakes at sea or near the coast - sometimes of large scale and with effects observed from wide distances. Among the first documented tsunamis in historical sources is the event that, in 365 A.D., affected the eastern Mediterranean Sea and which, recent studies [

5,

31], estimate to have originated near Crete Island. The tsunami’s strength caused widespread damage from Greece to Sicily to Dalmatia. Egyptian writers reported very accurate details of the observed effects along the coast of Alexandria, Egypt. Most of the tsunamis that have interested the Mediterranean Sea have been generated by strong earthquakes along the Greek arc, including the 1956 Amorgos tsunami, the Aegean Sea tsunami that has interested Greece and Turkey in 2017, and the 2018 Ionian Sea tsunami that mostly interested the Zakynthos Island. The most recent tsunami that affected the eastern Mediterranean Sea dates back to October 30, 2020. This event hit the coasts of Greece, especially the island of Samos and Turkey, particularly the province of Izmir where one person died due to the tsunami [

9,

32]

As for Italy, several factors make it highly exposed and vulnerable to tsunamis. These include:

- a)

the strong seismicity of the area on which the peninsula emerges and the seismicity of the areas close to it, related to the presence of the convergence margins of the plates (African and Arabian with the Eurasian one) and complicated by the presence of crustal blocks and micro-plates, such as the Adriatic one.

- b)

the presence of active volcanoes capable of triggering tsunamis (aerial and submarine factors)

- c)

over 8.000 km of coastline that make Italy a peninsula.

- d)

the presence of medium- and large-sized urban centres.

- e)

the presence of tourist facilities, due to the coastal beauty, saturate the landscape.

- f)

the presence of industrial hubs that rise on the coasts.

- g)

the estuaries of many rivers that facilitate the sea’s flow in the event of tsunamis and near which buildings have been located.

Italy, throughout history, has been hit by several major tsunamis. Among these are the tsunamis that affected the coasts of Puglia in 1627, the eastern coasts of Sicily in 1693, the coasts of Calabria and Sicily in 1783 and again the Calabrian coasts in 1905 [

33,

34,

35,

36].

1.2. The 1908 Reggio Calabria-Messina tsunami

On December 28, 1908 at 05:21 am, an earthquake of estimated magnitude greater than 7, struck southern Calabria and north-eastern Sicily.

For the Mediterranean area and for Italy it was one of the first events, in the instrumental age, that reached this magnitude and affected large coastal areas causing thousands of casualties and extensive damage.

The earthquake caused a tsunami that, in a few minutes, reached the coast. The highest values were recorded in Pellaro, near Reggio Calabria where the waves reached 13 meters in height. In Stromboli waves of about 10 meters were measured and in Messina the waves reached 3 meters in height causing the collapse of the port quay and widespread damage in the city. The tsunami was also recorded at the tide gauges of Naples and Civitavecchia respectively 300 and 500 km away. It is estimated that the tsunami caused about 2,000 victims or more which added to the approximately 80,000 victims caused by the collapses and effects of the earthquake [

1].

2. Addressing Tsunami Risk Perception

2.1. The elusiveness of tsunami risk

Among the various natural hazards, tsunami risk perception appears particularly difficult to study due to the inherent elusiveness of these phenomena. Tsunamis are generated by vertical displacement of large volumes of water caused by many different causes such as strong earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, landslides (cite) or rapid and intense changes in atmospheric pressure [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Tsunami waves, being pushed by gravity, gain kinetic energy, allowing them to travel across enormous distances without losing energy. There are regions and areas where strong earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and seismic or volcanic induced landslides can trigger tsunamis more frequently. In these contexts, local communities are quite likely to have learnt and assimilated in their culture life-saving behaviours that may limit loss of life and damage to coastal infrastructures.

Compared to other natural hazards, tsunamis appears instead to be particularly elusive and unfamiliar phenomena, due to the relative long return times of these events. By contrast smaller events are relatively more frequent but far from being recognized as real hazards [

3,

42,

43]. Furthermore, tsunamis may be triggered by physical events that may be neither felt nor perceived since they occur at a very far distance, making difficult recognize signals and to establish cause-effect relationships between signals and impacts (far-field tsunamis) [

10,

16,

44]. By contrast, tsunamis can be caused by sources very close to the coast (near-field tsunamis), which lacking adequate knowledge and preparation can make early warning and evacuation operations particularly difficult [

17,

45,

46].

Moreover, tsunamis impacts are extremely variable, due to the non-linear combination of physical phenomena related to the characteristics of the source, bathymetry and the coastal profile that can affect both the propagation of waves in the open sea and impacts near the coast [

47,

48]. As an example, an earthquake or a volcanic eruption can compromise the stability of a landslide by triggering a tsunami wave, as occurred in Scilla, 1783 [

33]. Worth also mentioning that tsunami are generally preceded by unusual and ambiguous premonitory signals (ground shaking, loud noise, sea level anomalies) thus making it particularly difficult them to be identified and recognized by people unfamiliar with this type of event, thereby hampering proper response (e.g., self- evacuation and other mitigation measures). Finally, despite dramatic advancements in scientific tsunami hazard and risk assessment, this growing body of knowledge is not deemed to automatically turn into effective risk communication practices [

16]. In particular, early warning procedures are affected by a large uncertainty mainly resulting from unknown details of sources and can be amplified by the urge to act rapidly to start evacuation procedures [

28].

In this respect, the elusive character of the tsunami is a consequence of all these factors, representing an objective obstacle to understanding. This perhaps represents the key point in tsunami risk communication, requiring a more articulate and in-depth study of the elements that can facilitate or hinder its effectiveness.

2.2. Definitions and factors affecting risk perception

The concept of risk perception is about the way people judge and evaluates risks, and it is basically referred to the process of collecting, selecting and interpreting signals about uncertain impacts of events, activities or technologies. Such signals may come from different types of sources, such as direct observation of an event (

firsthand experience) or more frequently, from information received or collected from other people in the community, from media system as well from scientific and institutional sources (

secondhand experience). According to one of the most cited definitions, ‘[s]tudies of risk perception examine the judgments people make when they are asked to characterize and evaluate hazardous activities and technologies’ [

49]. Risk perception is a subjective construct that may involve feelings, beliefs, attitudes and judgements about impacts associated with an event (50). This concept is strictly related with the assessment of certainty, severity, and immediacy of disaster impacts on individuals and communities, such as death, injuries, property destruction as well as disruption of work and normal routines (51). Risk perception is based on a combination of both individuals’ psychological and socio-cultural factors shaping people understanding and responses to risk issues and it is socially constructed through many sources of knowledge such as media, collective memories of past events, education and experiences, and the ways these sources are framed and interpreted through culture and society (52, 21, 16). Although there are no conclusive observations, risk perception is also influenced by socio-demographic variables such as gender, age, educational qualification, income, religion and political orientation, being investigated both as possible causes and as control variables [

53,

54,

55,

56].

Knowledge about risks, as well as messages about hazards and how they are assessed and managed circulate within broader social groups and contexts, construct shared meanings about the sources of risk, their dangerousness, and the actions deemed necessary to protect oneself, being able to affect individual courses of action as well as communities, culture, and political process [

57,

58,

59,

60]. The particular characteristics of tsunamis enhance the role of knowledge and its limits, since main sources of knowledge about this phenomena are certainly not related to first-hand experience and involve different sources of information such as broadcast media (e.g., Tv news, radio bulletins, movies newspapers and to some extent internet), narrowcast media (books, tv documentaries, civil protection campaigns, scientific communication), and personal networks, which may convey and re-produce information from direct witness as well as to revive tales of past events. Moreover, this information is often intertwined and implies the coexistence and overlapping of both vertical and horizontal communication flows, of differentiated sources (both official and unofficial), strategies, channels and communication models, being mediated through formal education, willingness to be involved and type of communication habits [

61,

62].

2.3. Socio-demographic variables

Our research aims to survey tsunami knowledge and study tsunami risk perception by analyzing the opinions provided by respondents residing in coastal areas affected by the 1908 event. Although tsunami risk perception is influenced by several factors individually, socially and cultural context-related, different studies show that the most influential socio-demographic characteristics are age, educational degree, gender, and residence proximity from the coast (distance from the sea). Other variables affecting tsunami risk perception are household size and property ownership (the higher the value exposed in terms of lives and property, the higher the tsunami risk perception) participation in tsunami awareness programs and specific drills [

62,

63,

64]. Data analysis provided the socio-demographic variables that effectively convey information about the focus of the analysis (see par. 4).

In addition, identifying the sample’s socio-demographic characteristics allows more effective and target-oriented tsunami risk mitigation and communication strategies and decision-making policies to be implemented [

62,

65,

66,

67].

2.3.1. Proximity, Age, Education

Variables such as gender, level of education, age, family composition and income are often analyzed in this type of research, although the results appear to be very much linked to the specific contexts in which they are carried out. Regarding gender, several studies show that it may significantly affect risk perception [

68,

69,

70,

71]. In some studies women are more likely to have a higher tsunami risk perception than men [

69,

70,

71,

72] while other research does not confirm such an influence on risk perception [

73,

74,

75,

76,

77].

Education was considered by many authors who studied risk perception related to natural hazards and, more specifically, the tsunami risk perception. In most studies, a strong relationship emerges between tsunami risk perception and educational degree. People with a higher educational qualification are more likely to have better knowledge about natural hazards in their area and basic knowledge about tsunamis. Such a knowledge, in some situations, may reduce the response time in case of emergencies and fosters appropriate and effective behaviors [

11,

21,

22,

64,

70,

71,

78,

79,

80,

81].

Age is also a variable that recurs frequently in research but its variability in studies on tsunami risk perception depends on contextual and cultural factors [

64]. In general, the relationship between age and tsunami risk perception is associated with individuals’ historical memory and experience gained through several catastrophic events experienced over a lifetime. In fact, several studies show that elders have a higher tsunami risk perception and are better informed than younger people. Conversely, young people have greater confidence in their ability to respond in the event of a tsunami due to their physical readiness [

62,

67,

70,

82]. However, the relationship between age and tsunami risk perception is not generally confirmed. A study conducted in Japan shows that although older people have a higher tsunami risk perception, this would not foster willingness to evacuate in the event of a tsunami.

Household composition is considered in several studies on tsunami risk perception [

62,

84,

77,

83]. Generally, this variable has a significant impact when there are young children, elderly people, or people with disabilities in the household. In these cases, tsunami risk perception is higher than in low-member households where there are no fragility factors. Households composed of many members who resided for several generations in the area and have strong territorial roots tend to have a lower tsunami risk perception since they have greater confidence in the mutual help offered by other family members [

84]. Household composition is a variable most frequently addressed in studies analyzing evacuation intentions in case of a tsunami. This specific aspect has been addressed in some studies [

85,

86] showing how individual solidarity may lead to delays in evacuation because family members expect to evacuate together.

The influence of spatial variables on risk perception [

79], however, seems to emerge more clearly: risk perception is often higher among people living near the coast [

67,

69,

75,

77,

82]

. In fact, those who live near the coast and are aware of hazards impending on their area of residence (hurricanes, floods, tsunamis) have a higher tsunami risk perception, and in general, proximity positively affects individual risk perception, without affecting the intention to remain [

64,

69]. Proximity to the coast also positively affects some key factors closely related to tsunami risk perception including: knowledge of the phenomenon, behaviors one would adopt in case of emergency, and evacuation in case of tsunami warning [

77]. Furthermore, research shows that tsunami risk perception is closely related to the temporal factors of residence in each area and to the memory of events that occurred in the past [

81]. Others noticed a lower tsunami risk perception among those living in cities or large urban centers than among those living in the countryside or small towns [

82]. In addition to distance from risk sources research also considered residence in potential flood-prone areas caused by both tsunami and weather events, concluding that the presence of risk sources close to residence positively affects risk perception, and as proximity from the risk source increases, risk perception decreases [

80].

2.4. Risk perception and knowledge sources

In a social science perspective, the role of knowledge is often called to account as a crucial factor to describe and explain risk perception, and theoretical and empirical research has indeed carefully considered the ways in which different people rely on different types of knowledge to ground their judgments on risk. One of the most influential approaches highlights the rise of risks in late modern society as an unintended effect of a deep crisis of scientific and technological knowledge, deemed to be less and less capable of predicting and controlling both natural and manmade hazards [

88,

89,

90,

91,

92]. Both laypeople and expert risks perception is to be seen as the outcome of mental and social processing of information and signals which is affected by individual characteristics and takes place within different social contexts, to give rise to culturally situated knowledge systems [

59,

93,

94].

Knowledge is recognized as a key issue in risk studies. Risk and knowledge are closely related: moving from Luhmann’s classic distinction between risk and danger, where risk is intended as the outcome of human decisions and danger to events due to environmental factors that cannot be directly controlled, risk and decision are intimately and inextricably linked to knowledge as a prerequisite of decisions, thus questioning its nature and legitimacy and the way knowledge is shared, accepted or contested. Furthermore, knowledge and scientific knowledge, has progressively converted hazards (unpredictable by definition) into risks that can be explained, measured, evaluated and - to some extent - predicted. Authoritative scholars, including Beck [

88], Giddens [

91], Lupton [

59], Jasanoff identified science as linchpins of modern societies, thus paying attention to the ways in which forms of knowledge are epistemologically, morally, and politically legitimized. Knowledge made possible turn unpleasant “acts of gods” into calculable, predictable and manageable events [

97].

2.4.1. Scientific and institutional knowledge

The advancement of scientific knowledge about risks, as well as the centrality of science in the processes of risk assessment, management and communication represent a specific feature of late modern societies [

88], embodying the belief that scientific rationality and technological development could provide a true understanding of nature and ensure control upon the natural world [

98]. This type of knowledge is at the core of political decisions on risk, being often considered as the only legitimate voice to inform policy making, as it is based on evidence from scientific research [

99]. Knowledge is made available to decision makers, stakeholders and general public through a number of specific and clearly identifiable channels: journals, books, scientific communication, schools, institutions (e.g., Civil Protection, Local Government). Nevertheless, scientific knowledge tends to suffer from the limitations of the language and channels being used as well as from the difficulty to “translate” complex concept into concrete and viable ideas for final users. This is noteworthy within tsunami science: despite the undeniable progress in the field science communication struggles to reach vulnerable communities, leaving several relevant issues to be addressed such as vulnerability, societal effects of tsunami, tsunami role in multi-hazard contexts and cascading risks [

26].

2.4.2. Media knowledge

In contemporary societies, media play an important role in mediating knowledge: in the risk society risks are becoming increasingly invisible, intangible and unpredictable [

88]. The increasing dependence by risk knowledge emphasizes role and responsibilities of media in producing, disseminating and utilizing information and definitions about risks. Media also provide an important stage where information from scientists, experts, policymakers, businesses, and interest groups is mediated, emphasizing the important their role of “meaning entrepreneurs” in framing and anchoring processes [

100,

101]. Media, both broadcast and digital, represent a relevant source of information on both hazards and disasters, while also fulfilling other important symbolic mediating functions, e.g., fostering social exchange, providing emotional support during events, evoking past experiences of similar situations, and constructing causal explanations of current events [

102]. The media, in particular, play a key role in defining what, how, and why a certain object poses a risk, but are also able to shape understanding of sources of risk [

104,

105] and influence how a certain risk is perceived [

106], thus becoming a major issue in public debate and policy decision-making on risks [

92]. However, it is noteworthy that media have often been accused of distorting, spectacularization, and trivializing scientific knowledge, thus contributing to public misinformation [

107,

108,

109]. These allegations find a partial justification as media lean on well-established routines and criteria to select and adapt some aspects of reality to their organizational purposes and constraint, the so-called media logic [

110,

111].

Within the tsunami risk management field, the role of the media is recognized both as a relevant source to get information in case of an event [

112], and as a resource to improve risk awareness [

16,

22,

113]. Media play an important yet contrasting role: on the one hand, they are recognized as indispensable actors in hazard mitigation programs due their capacity to spread information on tsunami and their outcomes [

114], on the other hand redundant media coverage may trigger feelings of anxiety and psychological unrest as well as a false sense of subjective invulnerability, possibly resulting into evacuation mishaps [

116]. In the Samos / Izmir event, occurred on Oct. 30th, 2020, despite most of the people were running away from the sea to evacuate, some were spotted staring at the sea to watch such an unfamiliar event Other research seems to suggest that visual framing of tsunamis as big waves and unavoidable destruction can result into a poor understanding of phenomena, of its anticipatory and a fatalistic attitude toward risk: media can enhance the idea that since tsunami is uncontrollable also its consequences would be uncontrollable [

11]. Finally, broadcast media have played a relevant role in the 2004 Sumatra and the 2011 Japan tsunamis and are expected to support relevant advancement in dissemination of information and educational activities on mitigation measures [

117].

2.4.3. Traditional Knowledge

Traditional knowledge is based on the cultural codification of the experience of past events and the construction of socially shared memories, being conveyed and reproduced through myths, ceremonies and rituals. These forms of knowledge and their importance in disaster mitigation processes are well known in the disaster literature, referred to by different definitions such as “local knowledge,” “traditional environmental knowledge,” “traditional ecological knowledge,” “indigenous technical knowledge,” “endogenous knowledge” (118, 119, 120, 15, 121, 122), and more rarely, “local wisdom” [

123]. This type of knowledge can be succinctly defined as “a body of knowledge existing within local populations or acquired by them over a period of time through the accumulation of experience, society-nature relations, community practices, and institutions, and through the transmission of these between generations [

124]. Moreover, scholars stressed the strategic importance of deepening, combining and integrating these forms of traditional knowledge with scientific knowledge [

125,

126,

127]. The imperative need of integrating different forms of knowledge and reevaluating traditional knowledge has found a perfect case study in the specific field of tsunami risk reduction. After the tsunami of December 26th, 2004, which originated from a large fault in the Indian Ocean near the coast of Sumatra, scholars’ attention focused on Simeulue, an island in Aceh district only a few tens of kilometers away from the event’s origin area, which despite being exposed to waves more than 30mt high, had a unattended low number of deaths. The surprising explanation for the responsiveness on the part of local people lies in the cultural memory of a tsunami that occurred in 1907 and the measures needed to escape the wave, reproduced through the generations by means of a nursery rhyme (the song of the Smong, i.e., tsunami) taught first in schools, later incorporated into Simeulue’s musical folklore [

17,

128,

129,

130].

Over the decades, cultural anthropology has often dwelt on these forms of knowledge about disasters, especially through the collection of oral histories concerning causal explanations of events and descriptions of their effects. These oral histories are forms of native knowledge “precipitated” after an event and, regarding tsunamis, they are most common in areas where this type of event is most likely to occur, (e.g., near subduction zones), particularly along the Pacific Ring of Fire. Indeed, there is a great deal of research on orally passed down stories, their symbolic meanings, and the possibility of integrating this kind of knowledge into Disaster Risk Management or DRR strategies.

To shortly summarize analogies and differences of the above paragraphs, see

Table 1.

3. Materials and Methods

The overall goal of risk perception research is to improve risk analysis and decision-making process, as well as to inform sound and consistent risk mitigation strategies. Especially, it is aimed at 1) improving methods for eliciting, collecting and classifying opinions on risks; 2) provide a basis for understanding and anticipating possible public reactions to hazards; 3) improve the communication of risk information among lay people, technical experts and decision-makers [

131].

This research has been promoted to improve seismologist, geophysics and risk managers ability to address lay people understanding of tsunami physics and its related risk, as well as possibly focusing on emerging critical issues. The questionnaire survey is intended to provide a robust base of quantitative data on the resident population in the different coastal areas, with a view to have reliable data on all Italian coastal municipalities and to make comparisons between different regions and areas characterized by a higher level of hazard and / or a history of tsunamis. The Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (hereinafter CATI) is deemed to be a reliable methodology to collect a large, standardized, retraceable and cost-effective amount of data [

132].

The scopes of this paper are expressed by three following research questions:

RQ1: Can the experience of a past tsunami in a given area still affect people’s risk perception, despite the event dates back over a century?

RQ2: What kind of socio-demographic and geographical variables may affect risk perception level?

RQ3: How can the different sources of knowledge used by people affect their perception of risk? And in which ways?

To obtain representative and reliable data, a stratified sample was built by using three stratification variables:

respondents’ age, gender and

coastal areas, as to ensure the best possible correspondence between subpopulations in the sample and within the reference universe. Such sampling strategy made it possible to collect 5842 interviews performed in 450 Italian coastal municipalities across 8 coastal regions. The results of Student’s T significance test on sample mean, confirmed the hypothesis that all the three considered sub-samples belong to the same population thus allowing the research to be based on a larger and therefore more robust sample in terms of statistical reliability. The whole set of municipalities (and in turn, single cases) has been split in two areas, including on one hand the ones where 1908 tsunami physical effects have been registered and documented (including municipalities for which there were no direct observations, but which fell within areas between municipalities where documented accounts of the effects of the phenomenon were available). On the other hand, we considered the municipalities befalling in areas where no effects have been reported and documented that we roughly assume to be not affected by the event and its effects. This subdivision was made on data from the Italian Tsunami Effects Database or ITED catalogue [

133,

134,

135], which reports observations of event-related phenomena based on direct measurements of geophysical data or data from historical sources.

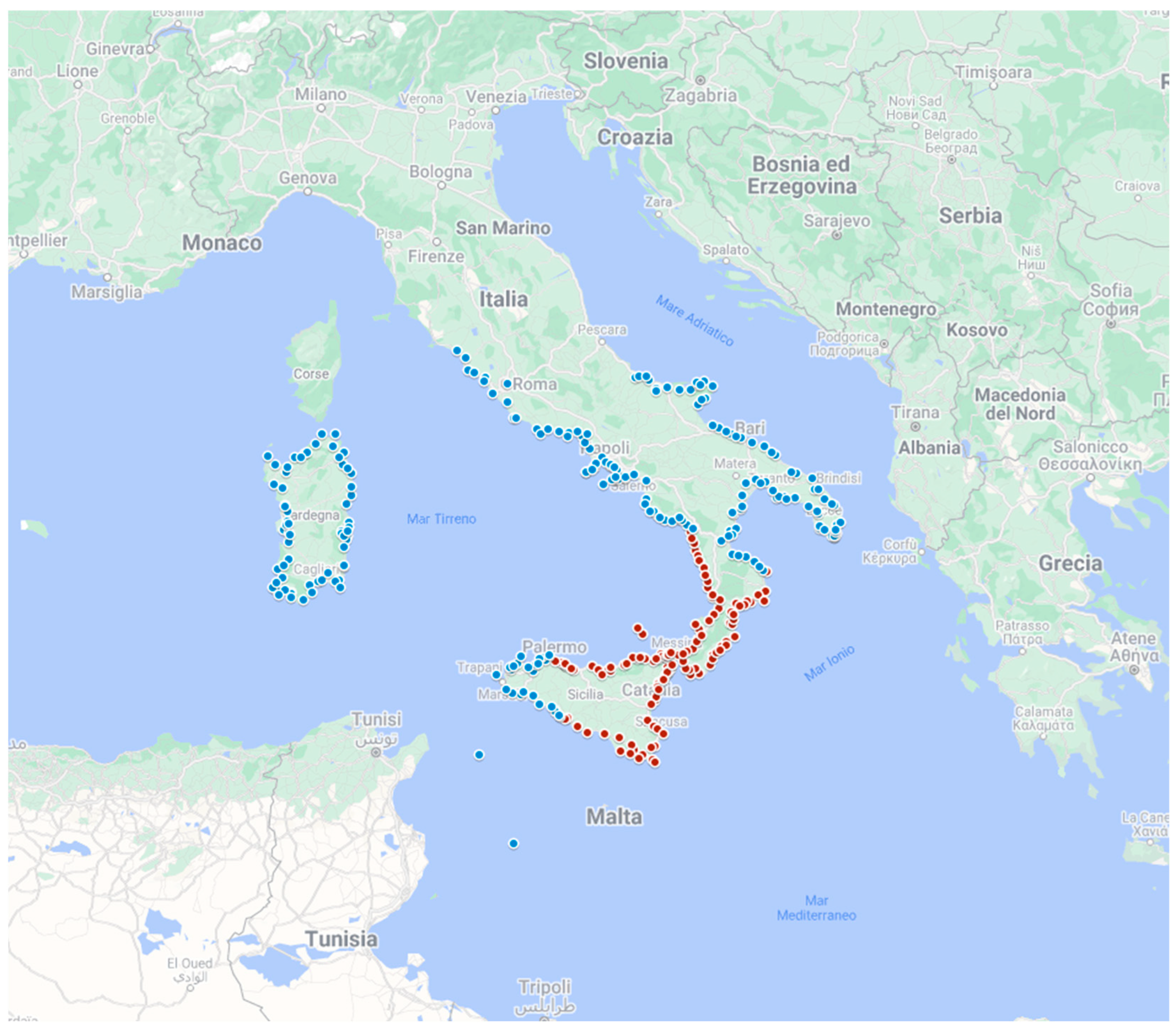

The sub-samples surveyed in coastal areas were respectively named as (a) 1908 area, including the coastal areas of Calabria and Sicily where tsunami effects were documented and reported in historical catalogs by coeval authors (N = 1624); and (b) non 1908 area, which includes the remaining coastal areas of Calabria, Sicily and also of Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, Lazio, Molise, Sardinia, (N = 4218) where no effects of the 1908 tsunami were reported or documented. Municipalities affected by the impacts of the 1908 area are plotted in red, while other included in the non 1908 area are plotted in blue (see

Figure 1).

4. Results

4.1. Socio-demographic variables

As a first step, we analyzed the distribution of socio-demographic variables in the two considered subsamples, to understand whether substantial differences exist and how they might affect the interpretation of the data.

Table 2.

Coastal areas subsample.

Table 2.

Coastal areas subsample.

| Coastal areas |

N |

% |

| Not exposed, no observed impacts (non 1908 area) |

4218 |

72,2 |

| Exposed, with observed impacts (1908 area) |

1624 |

27,8 |

| Total |

5842 |

100,0 |

The differences in the distribution of socio-demographic variables between the two sub-samples shows a general balance, with some minor differences: in the 1908 area there is a slight prevalence of women, people living within 1 km of the coastline and people who have lived in the same area since four or five generations.

In the non-1908 area, there are slightly more people living between 1 and 3 km from the coastline and those living in the same coastal area for only one generation (

Table 3). In the 1908 area, the most pronounced differences (>= 5%) concern the higher percentage of elders and people with high educational level: the percentage of people with a university degree or higher qualification is almost twice as high as in the other areas. Furthermore, there are more people residing in that coastal area since four generations. By contrast, in the non-1908 area we found higher percentages of people with mid-education level and people staying from two generation in that coastal area.

Table 3, for brevity’s sake, shows the distributions of the variables whose modes differ by at least 5%. None of the variables referring to household composition show substantial differences in the distribution between the two areas and have therefore been omitted. To provide a concise and easily understandable figure that allows for an effective comparison between different categories and areas, we developed a synthetic indicator. The tsunami risk perception index (hereinafter RPI) was constructed by focusing 11 specific questions from the questionnaire, concerning three major conceptual dimension of risk perception, namely

phenomena features,

probability of occurrence and

expected impacts of tsunamis. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [

136,

137] is a common multivariate approach based on the analysis on correlated variables, which has been employed in this study to reduce the underlying dimensions associated to tsunami risk perception across a number of indicators, to maximize the amount synthesized information, represented by the variance, as well as to identify a single synthetic variable (latent factor) to summarize and provide a robust and consistent measurement of relevant dimensions of risk perception, in order to make comparison between the considered areas and between different interviewees. (

1 See questions 13, 16, 18, 19, 22.1, 22.2, 22.3, 22.4, 23.2, 23.4 and 23.5 of the questionnaire (see supplement files))

PCA analysis is one of the most used and robust methodologies for mathematically transforming quantitative data into synthetic indices: due its capacity to summarize data dispersed across several variables, it has been used in several researches on risk perception [e.g., 138, 139, 140]. Before creating the RPI index (

Table 4). Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was used to check index reliability, and it confirmed the internal consistency and thus cohesion among the items contributing to the summary index. The Alpha value is a quite satisfying 0.66, since alpha values between 0.61 and 0.83 are generally considered optimal for validating the reliability of the variables [

141].

The 11 selected questions were arranged into a single index trough PCA as to provide a general indication of hazard perception by the interviewees and their ability to properly identify causes and physical effects. The most significant values are associated with the variables evoking damage, destruction and danger to people and their lives, while zero represents risk perception neutrality.

Table 5.

RPI in 1908 and non 1908 areas.

Table 5.

RPI in 1908 and non 1908 areas.

| |

Mean |

N |

Std. Dev |

| Non 1908 Area |

-0,06 |

4218 |

0,953 |

| 1908 Area |

0,15 |

1624 |

0,923 |

| Total |

0 |

5842 |

0,949 |

Table 6.

RPI in the surveyed region.

Table 6.

RPI in the surveyed region.

| |

Mean |

N |

Std. Dev |

| Calabria |

0,63 |

404 |

0,827 |

| Apulia |

0,49 |

617 |

0,874 |

| Molise |

0,41 |

100 |

0,985 |

| Basilicata |

0,21 |

140 |

0,933 |

| Sicily |

-0,04 |

1595 |

0,897 |

| Campania |

-0,13 |

1170 |

0,864 |

| Lazio |

-0,23 |

1034 |

0,986 |

| Sardinia |

-0,23 |

782 |

0,936 |

| Total |

0,00 |

5842 |

0,949 |

Even considering the two regions hit by 1908 tsunami, Sicily and Calabria (tab 5 and 6), the difference between affected and unaffected areas is clear and sharp. Despite these regions have different PRI values (namely -0,05 for Sicily and 0,63 for Calabria), values are considerably higher in the areas hit by the 1908 event (

Table 7).

The correlation analysis (

Table 8) shows that in the 1908 area RPI has a significant positive correlation with education level and age class. Indeed, RPI is negatively associated with distance from the coast: the closer the distance from the sea, the higher RPI mean values are observed (excluding people who were not able to recall the distance of their household off the sea).

With respect to non 1908 area, correlation coefficients between RPI and household distance from the sea are higher, while its value is slightly lower for RPI and educational qualification. In brief, socio-demographic variables are tied to risk perception, although proximity plays a relatively strong role, especially for those who live outside the 1908 area.

Table 9.

Correlation between age, qualification, household distance and RPI in non 1908 area.

Table 9.

Correlation between age, qualification, household distance and RPI in non 1908 area.

| |

Educational qualification |

Age (by classes) |

Household distance from the coast |

RPI |

| Educational qualification |

Pearson correlation (R) |

1 |

-0,114** |

-0,125** |

0,221** |

| Sig. (2-code) |

|

0,000 |

0,000 |

0,000 |

| N |

4168 |

4168 |

4168 |

4168 |

| Age (by classes) |

Pearson correlation (R) |

-0,114** |

1 |

-0,094** |

0,112** |

| Sig. (2-code) |

0,000 |

|

0,000 |

0,000 |

| N |

4168 |

4168 |

4168 |

4168 |

| Household distance from the coast 3 |

Pearson correlation (R) |

-0,125** |

-0,094** |

1 |

-0,230** |

| Sig. (2-code) |

0,000 |

0,000 |

|

0,000 |

| N |

4168 |

4168 |

4168 |

4168 |

| RPI |

Pearson correlation (R) |

0,221** |

0,112** |

-0,230** |

1 |

| Sig. (2-code) |

0,000 |

0,000 |

0,000 |

|

| N |

4168 |

4168 |

4168 |

4168 |

RPI appears is also affected by other socio-demographic variables such as education level: for those who have higher qualifications, its mean value is 0,57, while those with low education have -0,24. Having verified that the two socio-demographic variables that exert the greatest influence on risk perception are level of education and proximity, it is worthwhile to go into detail by analyzing the means in the two areas considered.

Table 10.

RPI and proximity in 1908 and non 1908 area.

Table 10.

RPI and proximity in 1908 and non 1908 area.

| |

1908 Area |

Non 1908 Area |

| How many km away from the coast do you live? |

Mean |

N |

Std. Dev |

Mean |

N |

Std. Dev |

| Within 1 km |

0,41 |

431 |

0,881 |

0,34 |

876 |

0,885 |

| From 1 to 3 km |

0,11 |

497 |

0,849 |

-0,04 |

1172 |

0,896 |

| Over 3 km |

0,02 |

676 |

0,962 |

-0,24 |

2120 |

0,963 |

| I don’t know |

-0,43 |

20 |

0,934 |

0,05 |

50 |

0,801 |

| Total |

0,15 |

1624 |

0,923 |

-0,06 |

4218 |

0,953 |

Data once again underscore - ceteris paribus - a difference in risk perception between the area exposed to the 1908 event and the area not exposed. It seems clear that proximity is a very important variable in the perception of tsunami risk: the closer the household is to the sea, the higher the average value of the indicator, indicating that risk is most perceived where conditions of objective vulnerability do exist. However, even for this indicator there is a clear and revealing difference between those who live in areas exposed to the 1908 event and those who do not. This not only affects those who live close to the sea (< 1 km) but also those who, at least in theory, should feel safer, living at greater distance.

As far as the educational level is concerned (Table 10), the effect on risk perception appears stronger in the areas affected by the 1908 tsunami, being associated with higher levels of risk perception in both areas while, low/no qualification have lower values with relevant differences for both those who have higher and mid qualifications and live in the 1908 area. This can only be attributed to people’s awareness of being exposed to the risk of a tsunami, which is visibly stronger in the areas affected by the 1908 event.

Table 11.

RPI and educational qualification in 1908 and non 1908 area.

Table 11.

RPI and educational qualification in 1908 and non 1908 area.

| |

1908 Area |

Non 1908 Area |

| Educational qualification |

Mean |

N |

Std. Dev |

Mean |

N |

Std. Dev |

| High |

0,57 |

308 |

0,826 |

0,43 |

485 |

0,865 |

| Mid |

0,26 |

714 |

0,871 |

-0,01 |

2106 |

0,958 |

| Low / no qualification |

-0,20 |

602 |

0,908 |

-0,27 |

1627 |

0,911 |

| Total |

0,15 |

1624 |

0,923 |

-0,06 |

4218 |

0,953 |

4.2. Source of knowledge, combinations and effects on risk perception

Alongside socio-demographic variables, it is important to consider in detail the role played by different sources of knowledge, and how they are currently used (and combined) by people (Table 11).

Table 11.

Sources used to gather information on tsunamis 4. (4 Multiple response question: % calculated on cases)

Table 11.

Sources used to gather information on tsunamis 4. (4 Multiple response question: % calculated on cases)

| |

1908 area |

Non 1908 area |

| |

N |

V% |

N |

V% |

| Tv News |

1328 |

84,3% |

3279 |

81,2% |

| Newspapers |

532 |

33,8% |

1385 |

34,3% |

| Books |

333 |

21,1% |

742 |

18,4% |

| Tv documentaries |

322 |

20,4% |

938 |

23,2% |

| Internet |

285 |

18,1% |

762 |

18,9% |

| Movies |

171 |

10,9% |

498 |

12,3% |

| Friends, neighbors, relatives |

159 |

10,1% |

162 |

4,0% |

| Radio |

147 |

9,3% |

295 |

7,3% |

| Civil protection |

47 |

3,0% |

59 |

1,5% |

| Universities and research institutions |

36 |

2,3% |

52 |

1,3% |

| Local Govt. |

31 |

2,0% |

25 |

0,6% |

| Total |

3391 |

215,2% |

8197 |

202,9% |

This kind of analysis is crucial not only to understand whether and how people collect information about this particular risk, but also to understand how these sources are brought together and, above all, the implications on risk perception. Tv news is by far the most relevant source of information for both residents in 1908 and non 1908 areas. This result is consistent with other sources, including the Italian National Statistical Institute: despite Covid-19 pandemics, television remains the most widely used media in Italy: in 2021, 90.1% of the population aged 6 and over said they watched it and 72.5 % did it daily [

142]: The second most used source are newspapers, followed by books, documentaries, Internet and movies. It is noteworthy that preferences are roughly distributed in the same way, with little differences within the two considered areas. Some noticeable differences are found for interpersonal and institutional sources. Despite friends, neighbors and relatives seem to play a minor role, they are listed by 10,1% of the 1908 area, against only 4,0% of the non 1908 area. In addition, people who specified sources in an open-ended question were likely to mention as source tales from grandparents or grand grandparents, who were very likely to refer to firsthand experience of the 1908 event, thus confirming our initial hypothesis.

On the other hand, scientific institutions, civil protection and universities, along with local authorities play a very limited role, since just one of these sources barely reaches 3% in the 1908 area (namely, Civil Protection), while research institutions and universities were mentioned by 2,3% and local authorities by 2%. Results are even more puzzling in non-1908 area, where these sources got a 1,5%, 1,3 and a 0,6%. The limited effectiveness of scientific and institutional sources is a very critical point to be carefully considered in future research as well as approaching future risk communication strategies (see also 21).

The way interviewees match together different sources of information provide further relevant insights. We considered combinations of different sources by grouping them according to homogeneous criteria with respect to the underlying communication model. The aforementioned sources were grouped as follows: media sources = broadcast media: Tv News, radio, newspapers, movies; scientific sources = specialized sources: narrowcast media, directly targeting messages at interested, segmented audiences: books, Tv documentaries, civil protection, scientific institutions, local government and finally interpersonal sources = word of mouth through personal networks: neighbors, friends and relatives. If we consider that people rely on different combinations of sources, some crystal - clear differences emerge in risk perception. In the 1908 area, the higher levels of risk perception have been found between those people who mix media, scientific and institutional sources, while those who were not able to specify their sources of information show the lowest level of risk perception (tab 10).

It must be pointed out two important issues: on the one hand, despite this combination of sources is found in a relatively low number of cases, it is associated with the higher levels of tsunami risk perception in both 1908 and non 1908 areas, respectively 0,62 and 0,55. Secondly, the values of this index are higher than those which have been found in association with any other socio-demographic and spatial variable.

Table 10.

RPI and sources combinations 5 to gather information on tsunamis. (5 Media only: combinations containing only television, newspapers, internet and movies; scientific sources: combinations consisting in Tv documentaries, scientific and institutional sources; interpersonal sources: relatives, friends or neighbors.)

Table 10.

RPI and sources combinations 5 to gather information on tsunamis. (5 Media only: combinations containing only television, newspapers, internet and movies; scientific sources: combinations consisting in Tv documentaries, scientific and institutional sources; interpersonal sources: relatives, friends or neighbors.)

| |

1908 area |

Non 1908 area |

| |

Mean |

N |

Std.dev |

Mean |

N |

Std.dev |

| Media, scientific, interpersonal sources |

0,62 |

50 |

0,69 |

0,55 |

52 |

0,795 |

| Scientific / institutional only |

0,43 |

88 |

0,798 |

0,1 |

250 |

0,746 |

| Other combinations (N < 50) |

0,39 |

48 |

0,853 |

0,21 |

44 |

0,976 |

| Media and scientific sources |

0,31 |

444 |

0,887 |

0,03 |

1166 |

0,99 |

| Media and interpersonal sources |

0,28 |

63 |

0,825 |

0,2 |

66 |

0,867 |

| Media only |

0,02 |

872 |

0,943 |

-0,13 |

2446 |

0,959 |

| Unspecified |

-0,34 |

59 |

0,844 |

-0,26 |

194 |

0,779 |

| Total |

0,15 |

1624 |

0,923 |

-0,06 |

4218 |

0,953 |

Furthermore, in the 1908 area other combinations of source including scientific sources result into higher values of risk perception, while in non-1908 area this effect appears to be much weaker. In the non-1908 area some combinations of sources are used by a very small yet non-relevant number of interviewees. Nevertheless, people who only rely on media sources as well as on unspecified sources have lower levels of risk perception. Data appear to be consistent with the theoretical premise by which is necessary to work on the integration of local and scientific culture to improve the awareness and preparedness of populations exposed to a particular risk.

As to provide further insights, worth considering socio-demographic characteristics of those who exclusively rely on TV News and of those who combined media, scientific and interpersonal source. On the one hand, the socio-demographic composition of those who use the media alone as a source of information appears substantially different from that of the general sample. In particular, the differences concern a slightly higher percentage of women (57.1 % vs. 55.1 %) but especially a strong over-representation of people with low educational qualifications (46.9 % vs. 38.1 %), which is accompanied by a slightly lower %age of people with medium educational qualifications (41.7 % vs. 44.5 %) and a more pronounced difference in the %age of people with high qualifications (17.1 % vs. 11 %), while the breakdown by age group appears very similar, with differences of less than 1 %.

Conversely, expecting a small number of cases eligible in this category, among those who combine scientific and interpersonal media sources, women are somewhat more numerous (58.1% vs 55.1%, while percentages of all age groups excluding the over-65s is slightly lower than in the sample, while the percentage of the over-65s is 25.5% vs 11.6%, and, most importantly, the percentage of people with high qualification is very overrepresented: 55.1% vs 11.0%.

5. Conclusions

Although Calabria has a very different level of tsunami risk perception with respect to Sicily, in both two regions risk perception is significantly higher in the areas that were hit by the 28th December 1908 event. Tsunami risk perception shows being affected by some socio-demographic variables, proven to be relevant to address tsunami risk perception. Education plays a relevant role, along with proximity and the long stay of the household in the same coastal area, being interpreted as measures of both awareness and familiarity with tsunami risk. Nonetheless, these factors alone could not provide a comprehensive explanation difference in tsunami risk perceptions in the 1908 area. Despite a time, span of more than a century, a somewhat local knowledge about the phenomena still remains, playing a certain role in addressing risk perception, emerging across all data and possible interpretations.

Moreover, analysis highlights a troublesome centrality of the media as a source of information. Tv news represents the most widely used channel: in fact, more than 4/5 of the sample uses it as a source about tsunamis, although this process implies substantial passivity on the part of the recipients, who do not actively engages in information seeking, but merely pays (limited) attention to news coverage of the events, while other channels require a more active participation on the part of the user, who actively and voluntarily seeks out the information required, for example through books and documentaries. People who use interpersonal sources, often explicitly linked to oral forms of storytelling about past tsunamis are significantly more numerous in the area affected by the 1908 event, also testifying the relevance of the oral memory, as open-ended questions often recall grandparents’ stories.

Sources of knowledge are differently handled: this does not depend on sample characteristics but on the sedimentation of the memory of the event: apparently the memory of the 1908 event also fostered further examination through media (TG, newspapers, radio) and scientific and institutional sources (universities and research Institutions, Civil Protection), which is however associated with a very limited penetration. In fact, the percentages of those who can integrate and combine different sources are higher in the area affected by the 1908 event, suggesting some social pressure to become more informed and knowledgeable about tsunami risk, moreover among those with higher educational qualifications.

Research data have important implications for the development of more effective risk communication strategies, first and foremost the need to overcome linear, hierarchical, and unidirectional view of risk communication by which messages are conveyed top down, by experts or authorities to lay people (e.g., decide-announce-defend or deficit models). As unequivocally shown by data, institutional and scientific communication are underperforming, confirming criticalities already noticed in previous research [

21,

22]. That is, there appears to be a clear need to simplify and make accessible scientific knowledge, along with the need of scientists and authority to learn how to strategically improve dialogue and interaction with the media. Second, there emerges the need for a novel approach to risk communication, can integrate different forms of knowledge (enhancing experiential knowledge), recovering where possible the orally transmitted legacy, and collecting documents and direct testimonies from people who had first-hand experience of the events.

The research presented here raises several issues that need to be adequately explored in the future. First, studies on risk perception in conjunction with PTHA maps would allow to identify critical issues and priority areas to build risk communication strategies, to be implemented within a stricter cooperation of geo-scientists and social scientists, as to identify areas where low risk comes along with high hazard, to prioritise drills and educational programs to improve community awareness and to implement more effective risk mitigation measures.

Furthermore, data on risk perception and knowledge should more effectively address tsunami risk communication and early warning systems operational design, duly considering expectations, needs and actual level of understanding and perception of risk by vulnerable populations. The need to overcome deterministic, hierarchical, and unidirectional views of risk communication suggests the adoption of a broader and more realistic definition of the communication process and more open and inclusive practices in approaching problems [

16]. It seems to us necessary to integrate and to reconcile the “vertical” dimension of risk communication (stakeholders, mayors, experts, local associations, etc.) and “horizontal” ones (between peers, neighbours, local associations, members of local communities) within risk management and communication processes, as to better support knowledge exchange and risk understanding.

This paper provides some descriptive data on the phenomenon, which limitations stem first and foremost from the structure of the questionnaire and from the way it is administered to respondents (CATI Interview). The need for robust and complete data on the one hand, and the competing need to collect valid and reliable data while limiting refusals or partial responses as much as possible, made it necessary to limit the duration of the telephone interview, and consequently the number of possible questions. Moreover, although the responses to some open-ended questions provided interesting insights CATI interview is not the most suitable tool to delve into its contents. In this regard, authors strongly recommend the adoption of qualitative and field-based approaches aimed at reconstructing narratives in a broader, more precise, and in-depth manner through the actors’ own thoughts, collected through in-depth interviews, life stories and ethnographic analysis of documents (diaries, written documents etc,).

Finally, the hereby presented research constitutes a first, concise approach to the use of multivariate analysis techniques in the Mediterranean context, namely, to build RPI index to measure for the specific scope of this paper. Authors and the whole research team agree on the need to further explore the use of this type of techniques, with the twofold purpose of exploring in detail the analytically relevant dimensions of tsunami risk perception and to allow for more effective syntheses, aggregations and comparisons of data within specific groups or spatial areas.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

This article was conceived and elaborated by both authors, in close collaboration. As for the attribution of the individual paragraphs, both AC and LC wrote together paragraphs 1, 3, 4.1 and 5. AC wrote paragraphs 2.1, 2.2, 2.4, 4.2 and LC wrote 1.1., 1.2., 1.3, 2.3.

Funding

This research has been supported by the National Department of Civil Protection (grant no. All. B2 2019/2021). Nevertheless, this paper does not necessarily represent DPC official opinions and policies.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated for the present study is not yet publicly available because the questionnaire has not yet been administered in all Italian coastal areas and the data are being further analyzed by the research team. However, data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Authors would thank the whole Tsunami Risk Perception Study Research Group of the INGV-Tsunami Alert Center (Alessandro Amato, Massimo Crescimbene, Federica La Longa, and Loredana Cerbara). Author would especially thank Loredana Cerbara (CNR-IRPPS) for her valuable support in PCA procedures.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflict of interest.” “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- Platania, G. , (1909). Il maremoto dello Stretto di Messina del 28 dicembre 1908, Bollettino della Società Sismologica Italiana, 13, 369-458 (in Italian).

- Baratta, M. , (1910). La catastrofe sismica calabro-messinese del 28 dicembre 1908. Relazione alla Società Geografica Italiana, Ed. Forni, vol.2, 458 pp., Roma (in Italian).

- Amato, A., Avallone, A., Basili, R., Bernardi, F., Brizuela, B., Graziani, L., Herrero, A., Lorenzino, M. C., Lorito, S., Mele, F. M., et al., (2021): From seismic monitoring to tsunami warning in the mediterranean sea, Seismol. Res. Lett., 92, 1796–1816. [CrossRef]

- Guidoboni, E. I maremoti antichi e medievali: una riflessione su sottovalutazioni e perdita di informazioni. Mem. Descr. Carta Geol. d’Italia XCVI, 239–250 (2014).

- Pararas-Carayannis, G. (2011). The earthquake and tsunami of July 21, 365 AD in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea-Review of Impact on the Ancient World-Assessment of recurrence and future impact. Science of Tsunami Hazards, 30(4).

- Stiros, S. C. (2001): The AD 365 Crete Earthquake and Possible Seismic Clustering during the Fourth to Sixth Centuries AD in the Eastern Mediterranean: A Review of Historical and Archaeological Data, J. Struct. Geol., 23, 545–562.

- Baratta, M. , (1936). I terremoti in Italia. Accademia Naz. dei Lincei, Pubblicazione della Commissione Italiana per lo studio delle grandi calamità, pp.181, Vol. 6, Firenze (in Italian).

- Dogan, G. G., Yalciner, A. C., Yuksel, Y., Ulutas¸, E., Polat, O., Güler, I., S¸ahin, C., Tarih, A., and Kânoglu, U. (2021). The 30˘ October 2020 Aegean Sea Tsunami: Post-Event Field Survey Along Turkish Coast, Pure Appl. Geophys., 178, 785–812. [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllou, I.; Gogou, M.; Mavroulis, S.; Lekkas, E.; Papadopoulos, G.A.; Thravalos, M. (2021) The Tsunami Caused by the 30 October 2020 Samos (Aegean Sea) Mw7.0 Earthquake: Hydrodynamic Features, Source Properties and Impact Assessment from Post-Event Field Survey and Video Records. J. Mar. Sci. Eng., 9, 68. [CrossRef]

- Bird, D., & Dominey-Howes, D. (2006). Tsunami risk mitigation and the issue of public awareness. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, The, 21(4), 29-35. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.412980582179910.

- Paton, D., Houghton, B., Gregg, C., Gill, D., Ritchie, L., McIvor, D., Larin, P., Meinhold, S., Horan, J., Johnston, D. (2008) Managing tsunami risk in coastal communities—identifying predictors of preparedness. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, The,23(1):4–9. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/agispt.20081620.

- Horan, J., Ritchie, L. A., Meinhold, S., Gill, D. A., Houghton, B. F., Gregg, C. E., Matheson, T. & Johnston, D. (2010). Evaluating disaster education: The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s TsunamiReady™ community program and risk awareness education efforts in New Hanover County, North Carolina. New Directions for Evaluation, 2010(126), 79-93. [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, J. V., Bronfman, N. C., Cisternas, P. C., & Repetto, P. B. (2020). Understanding the culture of natural disaster preparedness: exploring the effect of experience and sociodemographic predictors. Natural Hazards, 103(2), 1881-1904.

- Becker, J. , Johnston, D., Lazrus, H., Crawford, G. and Nelson, D. (2008), “Use of traditional knowledge in emergency management for tsunami hazard: A case study from Washington State, USA”, Disaster Prevention and Management, Vol. 17 No. 4, pp. 488-502. [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J. (2012). Knowledge and disaster risk reduction. In The Routledge handbook of hazards and disaster risk reduction (pp. 97-108). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Rafliana, I., Jalayer, F., Cerase, A., Cugliari, L., Baiguera, M., Salmanidou, D., Necmioglu, Ö., Aguirre Ayerbe, I., Lorito, S., ˘Fraser, S. et al. (2022): Tsunami risk communication and management: Contemporary gaps and challenges, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 70, 1–30. [CrossRef]

- McAdoo, B. G., Dengler, L., Prasetya, G., & Titov, V. (2006). Smong: How an oral history saved thousands on Indonesia’s Simeulue Island during the December 2004 and March 2005 tsunamis. Earthquake Spectra, 22(3_suppl), 661-669.

- Harbitz, C. B., Glimsdal, S., Løvholt, F., Kveldsvik, V., Pedersen, G. K., & Jensen, A. (2014). Rockslide tsunamis in complex fjords: From an unstable rock slope at Åkerneset to tsunami risk in western Norway. Coastal engineering, 88, 101-122.

- Rød, S. K., Botan, C., & Holen, A. (2011). Communicating risk to parents and those living in areas with a disaster history. Public Relations Review, 37(4), 354-359.

- Geografica Italiana, Ed. Forni, vol.2, 458 pp., Roma (in Italian).

- Goeldner-Gianella, L., Grancher, D., Robertsen, Ø., Anselme, B., Brunstein, D., & Lavigne, F. (2017). Perception of the risk of tsunami in a context of high-level risk assessment and management: the case of the fjord Lyngen in Norway. Geoenvironmental Disasters, 4(1), 1-15.

- Cerase, A., Crescimbene, M., La Longa, F., and Amato, A. (2019): Tsunami risk perception in southern Italy: first evidence from a sample survey, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 19, 2887–2904. [CrossRef]

- Cugliari, L., Crescimbene, M., La Longa, F., Cerase, A., Amato, A., & Cerbara, L. (2022). Tsunami risk perception in central and southern Italy. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 22(12), 4119-4138. [CrossRef]

- Lomax, A., & Michelini, A. (2013). Tsunami early warning within five minutes. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 170(9), 1385-1395. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N., Aoi, S., Hirata, K., Suzuki, W., Kunugi, T., & Nakamura, H. (2016). Multi-index method using offshore ocean-bottom pressure data for real-time tsunami forecast. Earth, Planets and Space, 68(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Basili, R., Brizuela, B., Herrero, A., Iqbal, S., Lorito, S., Maesano, F. E., Murphy, S., Perfetti, P., Romano, F., Scala, A. (2021). The Making of the NEAM Tsunami Hazard Model 2018 (NEAMTHM18), Front. Earth Sci., 8, 616594. [CrossRef]

- Løvholt, F., Fraser, S., Salgado-Galvez, M., Lorito, S., Selva, J., Romano, F., et al. (2019). Global trends in advancing tsunami science for improved hazard and risk understanding. Contributing Paper to GAR19, June.

- Gibbons, S.J. , Lorito, S., Macias, J., Løvholt, F., Selva, J., Volpe, M., Sánchez-Linares, C., Babeyko, A., Brizuela, B., Cirella, A. et al., (2020). Probabilistic tsunami hazard analysis: high performance computing for massive scale inundation simulations. Front Earth Sci 8(December):1–20. [CrossRef]

- Selva, J., Lorito, S., Volpe, M., Romano, F., Tonini, R., Perfetti, P., Bernardi, F., Taroni, M., Scala, A., Babeyko, A., et al. (2021) Probabilistic tsunami forecasting for early warning. Nat. Commun. 12, 5677. [CrossRef]

- Behrens, J.; Løvholt, F.; Jalayer, F.; Lorito, S.; Salgado-Gálvez, M.A.; Sørensen, M.; Abadie, S.; Aguirre-Ayerbe, I.; Aniel-Quiroga, I.; Babeyko, A.; et al. Probabilistic Tsunami Hazard and Risk Analysis: A Review of Research Gaps. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 628772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat (2013). General and regional statistics. Author: Isabelle Collet, Andries Engelbert. Catalogue number: KS-SF-13-030-EN-N. ISSN: 2314-9647.

- Kelly, G. (2004). Ammianus and the great tsunami. The Journal of Roman Studies, 94, 141-167. [CrossRef]

- Kalligeris, N., Skanavis, V., Melis, N. S., Okal, E. A., Dimitroulia, A., Charalampakis, M., Lynett, P. J., and Synolakis, C. E. (2022): The Mw=6.6 earthquake and tsunami of south Crete on 2020 May 2, Geophys. J. Int., 230, 480–506. [CrossRef]

- Zaniboni, F. , Pagnoni G., Gallotti G., Ausilia Paparo M., Armigliato A., Tinti S. (2019). Assessment of the 1783 Scilla landslide-tsunami’s effects on the Calabrian and Sicilian coasts through numerical modeling. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 19, pp.1585-1600. [CrossRef]

- Vivenzio G., (1788). Historia dei tremuoti avvenuti nella provincia di Calabria ulteriore e nella città di Messina nell’anno 1783 e di quanto nelle Calabrie fu fatto per il suo risorgimento fino al 1787, preceduta da una Teoria, ed Istoria Generale de’ Tremuoti, con un Atlante di 21 Tavole. Stamperia Regale, vol.2, Napoli (in Italian).

- Platania G., (1907). I fenomeni in mare durante il terremoto di Calabria del 1905. Bollettino della Società Sismologica Italiana, 12, 43-81 (in Italian).

- Mercalli, G. , (1906). Alcuni risultati ottenuti dallo studio del terremoto calabrese dell’ 8 settembre 1905. Nota letta all’ Accademia Pontoniana nella tornata del 26 novembre 1906. Atti Accademia Pontoniana di Napoli, 36, 1-9 (in Italian).

- Pasarić, M., Brizuela, B., Graziani, L., Maramai, A., & Orlić, M. (2012). Historical tsunamis in the Adriatic Sea. Natural Hazards, 61(2), 281-316.

- Rabinovich, A. B. (2020). Twenty-seven years of progress in the science of meteorological tsunamis following the 1992 Daytona Beach event. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 177(3), 1193-1230.

- Lorito, S., Selva, J., Basili, R., Romano, F., Tiberti, M. M., & Piatanesi, A. (2015). Probabilistic hazard for seismically induced tsunamis: accuracy and feasibility of inundation maps. Geophysical Journal International, 200(1), 574-588.

- Amato, A. (2020). Some reflections on tsunami early warning systems and their impact, with a look at the NEAMTWS. Bollettino di Geofisica Teorica ed Applicata.

- Atwater, B. F., Musumi-Rokkaku, S., Satake, K., Tsuji, Y., & Yamaguchi, D. K. (2011). The orphan tsunami of 1700: Japanese clues to a parent earthquake in North America. University of Washington Press.

- Lindell, M. K., & Prater, C. S. (2010). Tsunami preparedness on the Oregon and Washington coast: Recommendations for research. Natural Hazards Review, 11(2), 69-81.

- Heidarzadeh, M., Necmioglu, O., Ishibe, T., & Yalciner, A. C. (2017). Bodrum–Kos (Turkey–Greece) Mw 6.6 earthquake and tsunami of 20 July 2017: a test for the Mediterranean tsunami warning system. Geoscience Letters, 4(1), 1-11.

- Röbke, B. R., & Vött, A. (2017). The tsunami phenomenon. Progress in Oceanography, 159, 296-322.

- Weiss, R., Wünnemann, K., & Bahlburg, H. (2006). Numerical modelling of generation, propagation and run-up of tsunamis caused by oceanic impacts: model strategy and technical solutions. Geophysical Journal International, 167(1), 77-88.

- Slovic, P. (1987). Perception of risk. Science, 236(4799), 280-285.

- Crawford, M. H., Saunders, W. S., Doyle, E. E. E., Leonard, G. S., & Johnston, D. M. (2019). The low-likelihood challenge: risk perception and the use of risk modelling for destructive tsunami policy development in New Zealand local government. Australasian journal of disaster and trauma studies, 23(1), 3-20.

- Lindell, M. K., & Perry, R. W. (2004). Communicating environmental risk in multiethnic communities. Sage publications. Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- Doyle, E. E., McClure, J., Paton, D., & Johnston, D. M. (2014). Uncertainty and decision making: Volcanic crisis scenarios. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 10, 75-101.

- Wildavsky, A., & Dake, K. (1990). Theories of risk perception: Who fears what and why?. Daedalus, 41-60.

- Renn, O., & Rohrmann, B. (2000). Cross-cultural risk perception: State and challenges. In Cross-Cultural Risk Perception (pp. 211-233). Springer, Boston, MA.

- Sjöberg, L. (2002). Are received risk perception models alive and well?. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 22(4), 665-669.

- Siegrist, M., & Árvai, J. (2020). Risk perception: Reflections on 40 years of research. Risk Analysis, 40(S1), 2191-2206.

- Pidgeon, N. F. (1999). Social amplification of risk: models, mechanisms and tools for policy. Risk, Decision and Policy, 4(2), 145-159.

- Pidgeon, N. (2012). Public understanding of, and attitudes to, climate change: UK and international perspectives and policy. Climate Policy, 12(sup01), S85-S106.

- Lupton, D. (2003). Risk. Routledge, London.

- Zinn, J. O. (2006). Recent developments in sociology of risk and uncertainty. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 275-286.

- Weichselgartner, J., & Pigeon, P. (2015). The role of knowledge in disaster risk reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 6(2), 107-116.

- Buylova, A., Chen, C., Cramer, L. A., Wang, H., & Cox, D. T. (2020). Household risk perceptions and evacuation intentions in earthquake and tsunami in a Cascadia Subduction Zone. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 44, 101442.

- Mondino, E., Scolobig, A., Borga, M., & Di Baldassarre, G. (2020). The role of experience and different sources of knowledge in shaping flood risk awareness. Water, 12(8), 2130.

- Dhellemmes, A., Leonard, G. S., Johnston, D. M., Vinnell, L. J., Becker, J. S., Fraser, S. A., & Paton, D. (2021). Tsunami awareness and preparedness in Aotearoa New Zealand: The evolution of community understanding. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 65, 102576.

- Armaş, I. (2006). Earthquake risk perception in Bucharest, Romania. Risk Analysis, 26(5), 1223-1234. [CrossRef]

- McIvor, D., Paton, D., & Johnston, D. (2009). Modelling Community Preparation for Natural Hazards: Understanding Hazard Cognitions. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 3(2), 39-46. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M., & Lykins, A. D. (2022). Cultural worldviews and the perception of natural hazard risk in Australia. Environmental Hazards, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M. K., & Hwang, S. N. (2008). Households’ perceived personal risk and responses in a multihazard environment. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 28(2), 539-556. [CrossRef]

- Bronfman, N. C., Cisternas, P. C., López-Vázquez, E., & Cifuentes, L. A. (2016). Trust and risk perception of natural hazards: implications for risk preparedness in Chile. Natural hazards, 81(1), 307-327.