1. Introduction

Endophytic fungi spend part or the whole life cycle in plants, and form systemic and asymptomatic associations throughout the aerial parts of the host plant [

1]. Epichloid grass endophytes (Ascomycota, Hypocreales, Clavicipitaceae) are novel microbial resources characterized by strict host specificity, and until now, were recorded on at least 9tribes of cold-season grasses, including some economic grasses distributed all over the world [

2,

3]. Previously, cold-season grass endophytic fungi were divided into sexual and asexual grass endophytes. The former belongs entirely to the genus

Epichloë, while the latter imperfect fungi belong to the very heterogeneous

Acremonium [

4]. In 1996, grass endophytic fungi in the genus

Acremonium were transferred to the newly established genus

Neotyphodium [

5], and subsequently the genus

Neotyphodium was merged into the genus

Epichloë in 2014, which is also endophytic fungus of the cold-season grass [

6]. Nowadays, cold-season grasses endophytic fungi are all in the genus

Epichloë, so they are also called “Epichloid endophytes”.

As a symbiosis with cold-season grasses, Epichloid endophytes improve the resistance of host plants to biotic and abiotic stresses [

1,

7]. They are usually found only in plants, and most can be dispersed vertically through seeds. A small number of members can also form stromata under the flag leaves during the plant’s flower stage, allowing natural hybridization and horizontal transmission [

6]. Most of the original

Neotyphodium members such as

E. coenophialum,

E. festucae var.

lolii,

E. aoteroae cannot form stromata on the plant surface and can only be vertically dispersed through seeds [

1];

E. poae do not form ascomycetes and ascospores and can only be transmitted horizontally by conidia [

3], while

E. stromatolonga can form stromata without identifying sexual stage, and the horizontal transmissibility of conidia forming on the surface of stromata has not been confirmed [

8]. On the other hand, the largely heterogeneous species

E. typhina on orchard grass, timothy and some other plants has not been observed or isolated from seeds of their host plants [

6].

Researches of endophytic fungi in China mainly focuses on cold-season grasses, especially

Achnatherum spp.,

Leymus spp., and

Elymus spp., which have attracted much attention in the northern grassland region [

9,

10,

11]. In 2006, we reported the endophytic fungus

Epichloë yangzii forming stromata on

Roegneria spp. plants in China [

12]. Due to its characteristics in phylogenetic analysis and its ability to show weak hybridization ability in artificial hybridization experiments with

E. brimicola from several European

Bromus spp. [

13], Leuchtmann et al. suggested to combining the two groups with the name

Epichloë brimicola [

6]. But the taxonomy of this fungal endophyte still remains a controversy.

Leymus chinensis is tolerant against drought, cold, alkali and trample on by livestock, as well as has a high grass yield, good palatability, rich protein content, and wide adaptability. Thus, it’s not only an important grass forage in China, but also a widely used substance in artificial grassland construction and ecological construction [

14,

15]. The endophyte in

L. chinensis was firstly detected by Nan Zhibiao from the seeds in Qinghai in 1996 [

16]. In 2013, the plant ecology research team of Nankai University reported the asymptomatic endophytic fungi obtained from

L. chinensis grown in eastern Inner Mongolia. They concluded that those fungal isolates were close to the

E. yangzii we found from

Roegneria spp. through mycological and molecular systematic properties. They identified these strains as Choke disease endophyte

Epichloë bromicola, according to Leuchtmann et al. [

11]. However, they did not find or make any symptom on host plants neither in natural grassland, nor under artificially controlled conditions [

6]. Therefore, we believe that the identification of the symptomatic endophytic fungus obtained from

Leymus chinensis in eastern Mongolia is still a new task.

During field investigations in Liaoning, Hebei, Inner Mongolia and Shanxi from 2010 to 2011, we collected stromata on Leymus plants in Inner Mongolia. Fungal strains were isolated. Their morphological and phylogenetic properties were analyzed, their taxonomic position was discussed and revealed different insights from previous study.

4. Discussion

Leymus spp. are important forage grasses in northern China, and also widely distributed in northeast, northwest and north China as ground-cover plants. Particularly, they are also important plants compatible with wheat (

Triticum aestivum L.) in artificial hybridization tests. Therefore, we focused on the survey of seed transmitted fungal endophyte within these plants. Stomata bearing plants of Tongliao district and Horqin Shadi were collected and isolated 9 and 16 strains, respectively. These strains had similar morphological and phylogenetic characteristics, with slightly faster growth rates than common members of

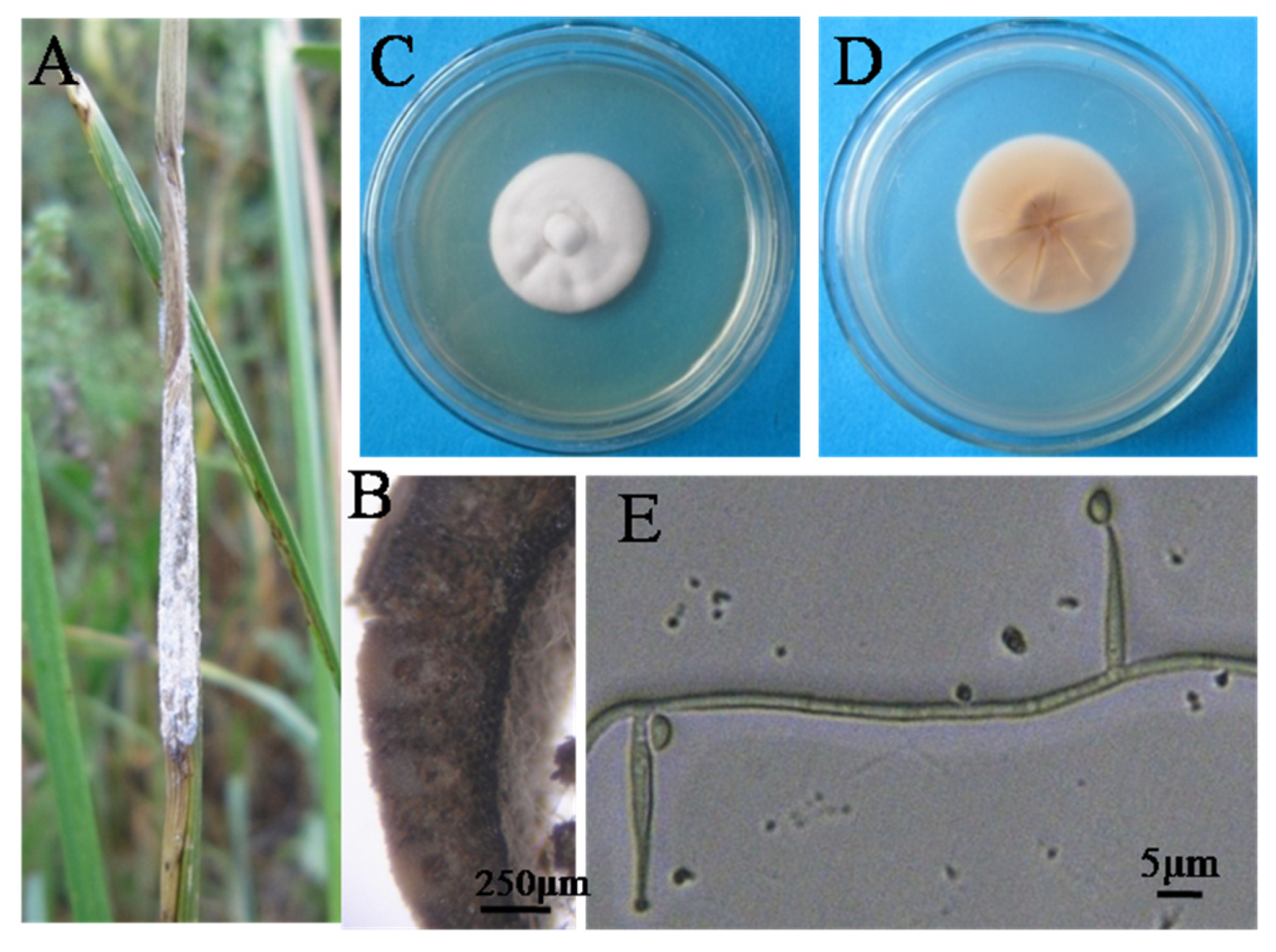

Epichloë spp.. The characteristics of conidia and phialides were typical of epichloid endophytes (

Figure 1,

Table 2). Combined with phylogenetic analysis, these isolated strains are typical epichloid endophytic fungi. This is the first report that typical symptomatic epichloid endophytes have been isolated from wild

L. chinensis (

Figure 1A) grown in natural grasslands and sandy lands.

L. chinensis (Triticeae) is rarely recorded to be infected by endophytes [

16,

24]. In 1996, Nan

et al. firstly found 12%

L. chinensis seeds from Qinhai were infected, confirming the distribution of endophytic fungi in grass

L. chinensis grown in Northwest China[

16]. In 2006, Gao

et al. investigated the endophyte resources of grasses in Inner Mongolia, and also found endophyte in

L. chinensis [

24]. However, mycological properties were not tested in the early stage. In 2013, Gao

et al. carefully investigated

L. chinensis in a large area from central to northeastern Inner Mongolia, and reported three morphotypes of endophytes from asymptomatic

L. chinensis plants. But none of them was reported to be a new taxon [

11]. On September 2011, we surveyed endophyte resource in Inner Mongolia, and collected a total of 2252 grasses. Most species were lower than 10% in infection level while 99% of

A. sibiricum were infected, which was coincidence with previous study [

16,

24].

Tongliao district and Horqin Shadi are located between 43° and 44° N in southeastern Inner Mongolia, and belong to the arid and semi-arid region of the middle temperate zone.

L. chinensis usually begin flower and fruit on June, the followers wither away on August, in Tongliao, southeast area of Inner Mongolia. On the sampling date of September, the leaf sheath only surrounded with white and collapsed stromata, the stromata were at the final stage (

Figure 1A). Observing the cross section of the stromata, perithecia with no aperture was observed under microscope (

Figure 1B), and no ascus was observed. Therefore, we speculate that it is possible that the ascus has been ejected from the perithecium and the perithecium collapses, or that the ascus is not developed due to unfertile stromata. We obtained endophytic fungi

E. stromatolonga Ji

et al. that can form stromata but no mature stromata from

Calamagrostis epigeios grown from Nanjing and Huangshan in eastern China [

8], and whether this is the another case or not, this stromata needs to be further investigated.

In this study, 25 endophytic fungi strains were isolated from Tongliao district and Horqin Shadi in Inner Mongolia. Colony morphology, growth rate, size and shape of phialides and conidia, were typical of epicholid endophytes, but these strains exhibited difference from previous reported species (

Table 2) [

2]. The strains from Tongliao district and Horqin Shadi shared nearly similar identity in

tefA and

tubB fragment. Their sequences diversity between strains was far less than that of their previous relatives [

11,

16,

24]. The two sampling sites of this study are actually distributed in the Horqin region. Nankai research group surveyed a wide range of sampling sites, which can better reflect the fact that

L. chinensis and its endophytic fungi in the central and eastern regions of Inner Mongolia. The endophytic fungal strains of

L. chinensis exhibit richer genetic diversity, together with the long-term distribution and long-term evolution of

L. chinensis in eastern Inner Mongolia. [

16,

24]。

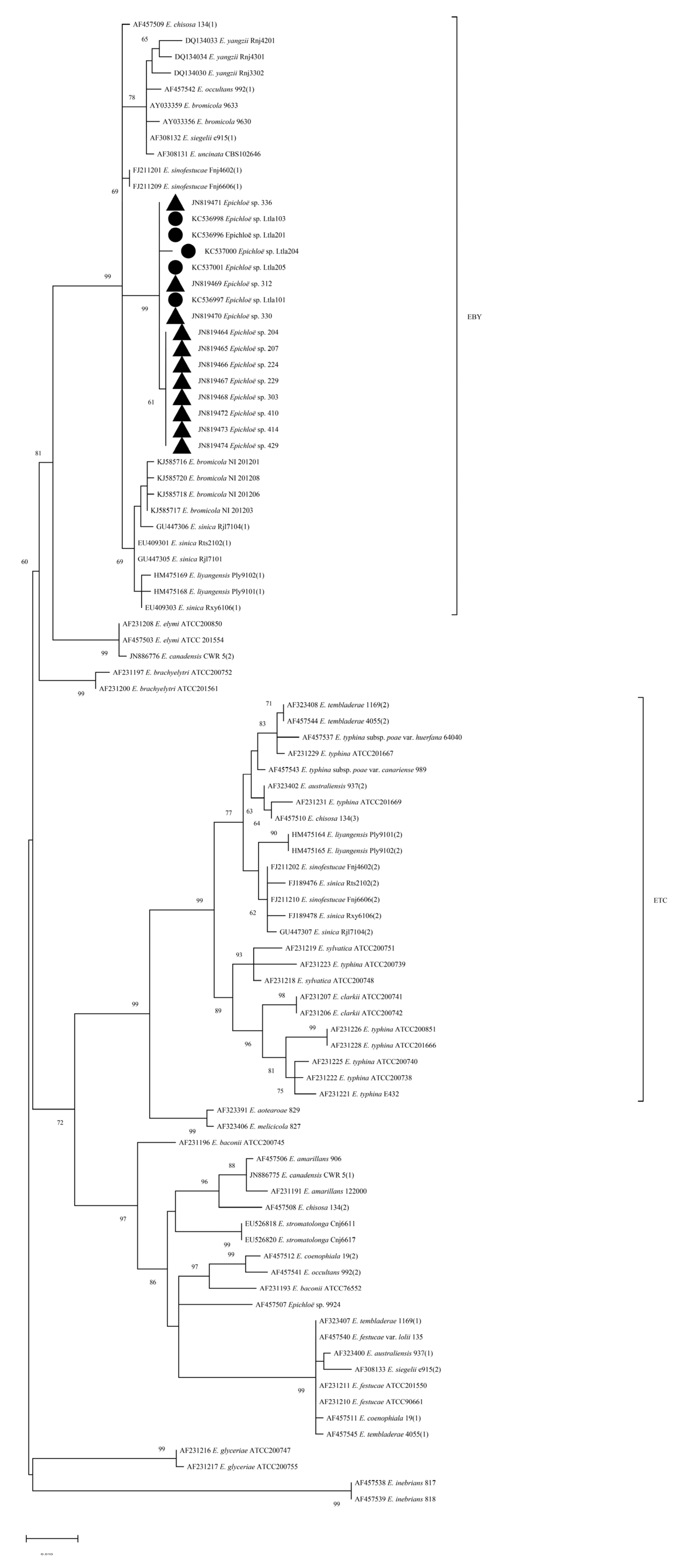

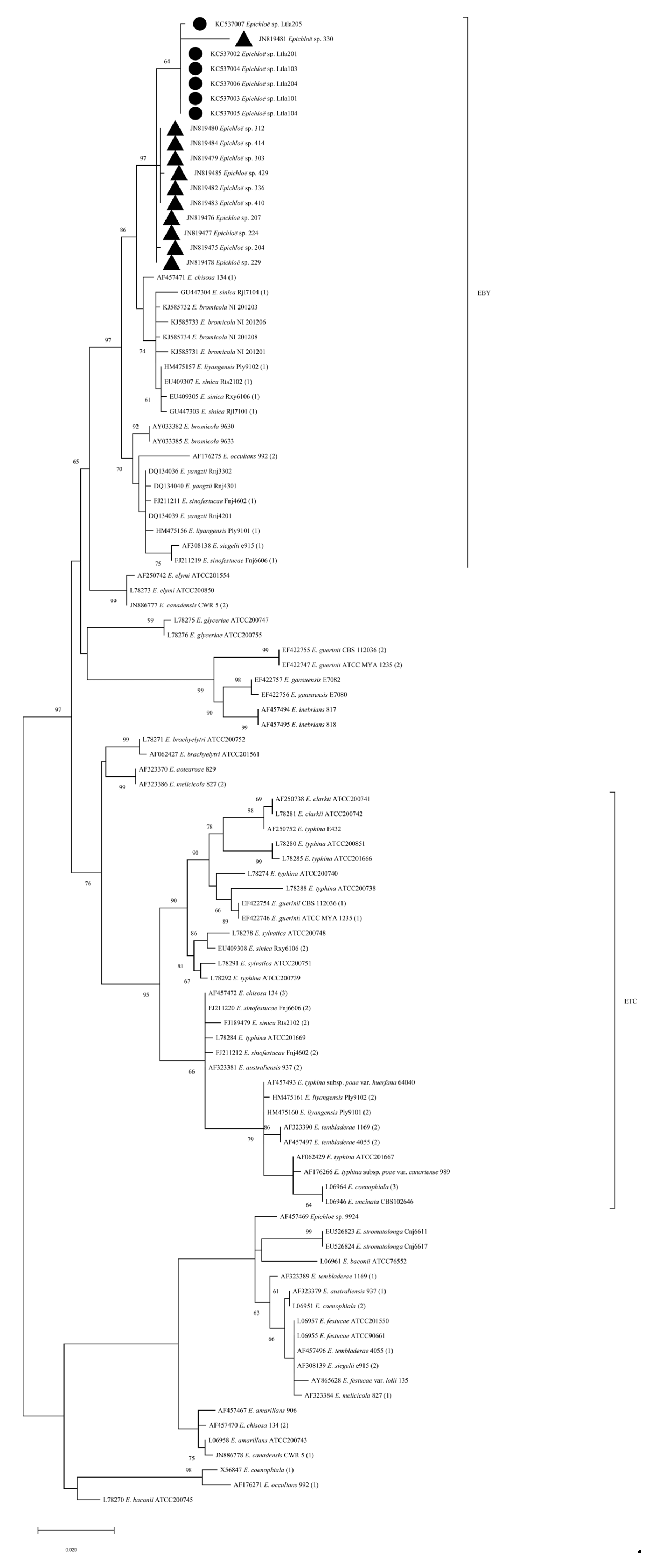

In the phylogenetic analysis based on

tefA and

tubB fragments, each species formed small independent branches with high bootstrap values, consistent with previous reports [

11]. All the strains of Inner Mongolia

L. chinensis formed an independent branche on the EBY clade, with bootstrap values of 99% and 97% for

tefA and

tubB respectively, showing significant differences from other strains (

Figure 2). Due to the absence of stromata morphology and live plants, we could not conduct artificial hybridization experiments to determine the strains of

L. chinensis. The relationships between these strains and strains of

Roegneria spp. and

F. parvigluma which were most closely related in systematics were not settled down. Therefore, the taxonomic status of the

L. chinensis strain was not conclusively determined in this study. Strains of

E. sinica (syn.

N. sinicum),

E. sinofestucae (syn.

N. sinofestucae) species are interspecific hybrids [

16], but not for

L. chinensis strains. Combing morphological and phylogenetical properties,

L. chinensis strains could be a new taxon apart from

E. bromicola (syn.

E. yangzii) and

E. sinica (syn.

N. sinicum).

Nankai group investigated fugal diversity in middle and north Inner Mongolia steppe. In 2013, 96 fungal isolates of 3 morphotype (MT) were obtained from of

L. chinensis. They believed that MT1 was similar to our

E. yangzii strains obtained from

Roegneria spp., and proposed them as

Epichloë bromicola [

11]. This is based on the academic view of Leuchtmann’s team in Europe, which is different from ours.

At the 9th (2010) and 10th (2012) the International Symposium on Fungal Endophytes of Grasses, Leuchtmann and we discussed the taxonomic relationship between

E. bromicola and

E. yangzii, but failed to gain a consistent insight. Leuchtmann et al. adhered to the most basic European tradition of “being able to hybridize is the same species, and vice versa”, and used this as the only criteria to classify fungi [

13]. We believe that reproductive isolation is indeed important and agree that the individuals with reproductive isolation are different species, but we believe that the individuals that can be artificially crossed are not necessarily the same species. Allopatric isolation is another “natural isolation” in addition to reproductive isolation, which can cause the separated population to form their own evolutionary process. Moreover, artificial hybridization is not natural hybridization, and strains that can be artificially hybridized in the laboratory may not meet in nature. Especially for plant endophytes, variations in host species and stromata formation times can also constitute allopatric isolation. It is conceivable that successful hybridization can be mated when mating with artificial cultures, but in nature they cannot be crossed due to the time and place of stromata formation. In other words, two strains with a certain hybridization compatibility may not have the opportunity to hybridize under natural conditions. In fact, the affinity between

E. bromicola isolated from

Bromus erectus in Europe, and

E. yangzii isolated from

Roegneria spp. in the Far East of Asia, is not strong. Hybridization between the two strains, even under artificial conditions, was not frequent, and only a small number of perithecia, even unfertilized were formed in our repeated inoculating experiments (Wang Zhiwei and Li Wei, 2005, unpublished data). There are 77 species of

Bromus plants in China, but distribution of

Bromus erectus is rare [

25]. Also,

Bromus spp. (tribe Bromeae) have a slightly distant plant taxonomic relationship with

Roegneria spp. (tribe Triticeae) in the family Poaceae. Although

Roegneria spp. are widely distributed in humid areas, the flowering stage varies with region, and it may overlap with

Bromus erectus in time. However, the Far East and Europe are separated by thousands of mountains and rivers, and the two places are separated by plateaus, Gobi, especially arid areas with altitudes of more than 4,000 m such as the Himalayas, Kunlun Mountains and Tianshan Mountains. It is really hard that

Bromus erectus and

Roegneria spp. endophytic fungi isolated from the Far East of Asia are able to communicate.

Roegneria is a large genus with a lot of members distributed in the eastern end of Eurasia (north of South Ridge in China, the Korean Peninsula, the Japanese Islands, etc.), while there are few at the western end of Eurasia. The European taxonomic system merges the

Roegneria genus into the genus

Agropyron. This physical barrier also has a certain impact on the distribution of

Roegneria spp. Thus, geographical barriers also play an important role in the distribution and formation of species. Therefore, in terms of fungal and plant classification, the ability to hybridize between strains and plants is not the only criterion for species judgment. Other isolations, such as temporal isolation and geographical isolation, are also the driving forces that in fact promote the evolution of species.

On the contrary, with the continuous discovery of various strains and classification, there are more and more taxonomic groups, and hybridization between strains is becoming more and more unrealistic. This will undoubtedly hinder the development of fungal endophyte research. Conversely, if strains from various plants are grouped together as a result of artificial hybridization, as advocated by Prof. Leuchtmann, the generalized

E. bromicola [

6] species will contain more and more members, and its heterogeneity will increase, which will eventually lag the discovery on this species. The classification of organisms is originally artificial classification, which is relatively based on subjective factors, so there is more factors for discussion. The reason why people want to talk about the classification of various organisms is to promote the better development of research in this field. One species with high heterogeneity among the endophytic is

Epichloë typhina (syn.

N. typhinum). This is a relatively classic species that was recorded and studied earlier, but compared with other endophytic fungi, the biological characteristics of the strains within this species are very different, and the molecular systematics characteristics are also relatively complex.

E. typhina, which is known as ETC (

Epichloë typhina-complex, or

Epichloë typhina-clade) in phylogenetic analysis, is lagged behind in research. In fact, there are very few researchers concerning about

E. typhina. Whether this is related to the excessive heterogeneity of

E. typhina is worth speculating. Therefore, in order to promote the research of grass endophytes, we still advocate that factors such as spatiotemporal isolation and host isolation should also be included in the classification. Moreover, in addition to spatiotemporal isolation and host species, there are many differences between

E. bromicola,

E. yangzii and

E. sinica (unpublished data). Therefore, we tend to not classify these

L. chinensis strains as

E. bromicola.

Epichloë spp. have a smaller distribution than the previous asexual

Neotyphodium spp. [

2]. In addition to the genotype of fungi, whether or not to form stromata on host plants is also affected by environmental conditions [

1]. Therefore, the formation of stromata of

Epichloë on host plants may not occur every year. Most grasses endophytic fungi are host-specific, and one plant corresponds to one endophytic fungus [

2]. Endophytic fungi can form stromata on

L. chinensis, indicating that in the long-term evolutionary process,

L. chinensis and endophytic fungi formed new associations.

Typical

Epichloë species could develop stromata around plant sheath/culm and is considered to be the sexual stage of the pre-

Neotyphodium spp.. Until now, five stromata bearing species have been reported in China,

E. yangzii in

Roegneria spp.[

12],

E. stromatolonga in

Calamagrostis epigeios[

8],

E. sibirica in

Achnatherum sibiricum [

26],

E. sylvatica in

Brachypodium sylvaticum [

27],

E. liyangensis in

Poa pratensis ssp.

pratensis [

22].

E. yangzii was considered to be hybrid ancentor of

E. sincia [

23]. In addition to the middle and lower basin of the Yangtze River, our research group also collected

Roegneria spp. plants from Shandong, Liaoning and other regions. However, the distribution range of

Calamagrostis epigeios and

Poa pratensis ssp.

pratensis that can form stromata is relatively limit [

8,

22]. In our 20 years’ investigation of grasses endophytes resources of in more than 10 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions in East China and North China, only a small number of stromata bearing

L. chinensis in Tongliao District and Horqin Shadi were collected.

L. chinensis is widely distributed in northeast, northwest and north of China, and the investigation of endophytes requires further research. In this study, 44 stromata bearing

L. chinensis samples of Tongliao District and Horqin Shadi in Inner Mongolia were collected. It was the first report of stromata on wild

L. chinensis plants, and it was also the sixth grass with stromata reported in China.

Until now, no records about toxic symptoms caused by

L. chinensis had been documented, indicating neither ergot nor indole-diterpenoids alkaloids were estimated within this association.

L. chinensis has the advantages of drought tolerance, cold resistance, alkali resistance, and resistance to trampling by cattle and horses [

14,

15], and the plants that bearing stromata tend to have strong vegetative growth, stems, leaves and root systems. For a long time,

L. chinensis has been a dominant grass species in northern China, and it plays a pivotal role in the vegetation in arid and semi-arid areas. It is worth considering whether the discovery of

L. chinensis with stromata in Tongliao district and the Horqin Shadi is related to the windy and dry environment and its surroundings. Therefore, whether the endophytic fungus of

L. chinensis is a new type of microbial resource is expected to be further studied.