1.0 Introduction

Placemaking is defined as a creative yet intentional process of designing, developing, managing, planning, and programming shared-use spaces by bringing together people to improve a community’s cultural, ecological, economic, and social situation (Ball, 2014). Peoples’ experiences of emotional and physical wellbeing are influenced by built environments that provide a sense of belonging (Stokols, 1990; Rogan& Horwitz, 2005). Historic sites are examples of built environments that provide this sense of belonging by promoting communication and shaping social life (Lynch, 1984; Gehl, 1987). Experts argue that historic sites must not be treated solely as historical objects or lifeless antiquities but should instead be used as a means of generating activity (Historic England, 2019). These historic sites constitute the core of many projects engaged with the aim of regenerating urban spaces by significantly improving the economy and generally resulting in the development of the broader region by strengthening peoples’ experiences (Porfyriou & Sepe, 2016). Historic sites play a vital role in placemaking wherein certain values extend across cultural, ecological, economic, and social realms in transforming spaces into places (The Institute of Historic Building Conservation, 2020).

Lighting constitutes an essential part of day-to-day activities and social interaction in urban spaces, by serving to attract, direct and enchant people within the urban context (Davoudian, 2019; Brandi and Geissmar, 2007). While urban spaces can provide a place for social interaction amongst people regardless of the time of day, there is a general reduction in the level of social engagement and contributions made by people during the night-time (Edwards & Torcellini, 2002). The concept of night-time lighting for urban spaces is therefore considered an essential factor in engaging people such that they can make full use of these spaces at night: lighting plays a vital role in improving the quality of urban spaces as it has the ability to facilitate different perceptions within public spaces at night-time (Carmona, 2021). Lighting historical sites during night-time therefore becomes fundamentally important given their potential in cultivating a sense of place amongst people with meaningful cultural and social activities.10 Lighting should comprise not only energy-related statistics and quantitative lighting performances, but also consider peoples’ experiences and perception of the urban space (Narboni, 2004).

There are a number of lighting design guidelines and codes that include measurable indices to indicate the quality of the urban night-time environments (Uchida & Taguchi, 2005; Ekrias et al., 2008; Johansson et al., 2014; Boyce, 2013). However, very little evidence has been found on the impact of lighting on human psychology and the basic mechanics of social engagement in historic sites. Therefore, this paper asks the following questions: Can lighting be a key facilitator in the placemaking processes for historic sites? If yes, what are the key lighting characteristics and lighting design considerations that can help facilitate the placemaking processes for historic sites? The paper specifically investigates the impact of lighting on peoples’ experiences and perception of historic sites that have been designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Although lighting includes several quantitative characteristics, the paper limits its scope to the qualitative characteristics and design considerations required for placemaking, by focusing on the impact of lighting on the cultural, ecological, economic, and social situations of World Heritage Sites.

2.0 Methods

Two UNESCO-designated World Heritage Sites namely Saint-Avit-Sénieur in Dordogne, France and Naghshe-Jahan-Square in Isfahan, Iran are selected as case studies. Research methods inspired by ethnography, which include interviews, observations, and questionnaires are used for gathering data about peoples’ day-to-day engagements, experiences, opinions, and usual activities in relation to lighting within these case studies. Ethnography enables the development of theoretical guidelines based on data gathered through participant interviews and observations within settings (Fine, 2003). Given the large populations of people required for undertaking ethnographic research in a comprehensive manner, representative portions of these populations were sampled using both probability and nonprobability methods (Proctor, 2005; Hejazi, 2006; Naderifar & Ghaljaie, 2017).

2.1 Case Studies

2.1.1 Case Study One: Saint-Avit-Sénieur Lighting Features:

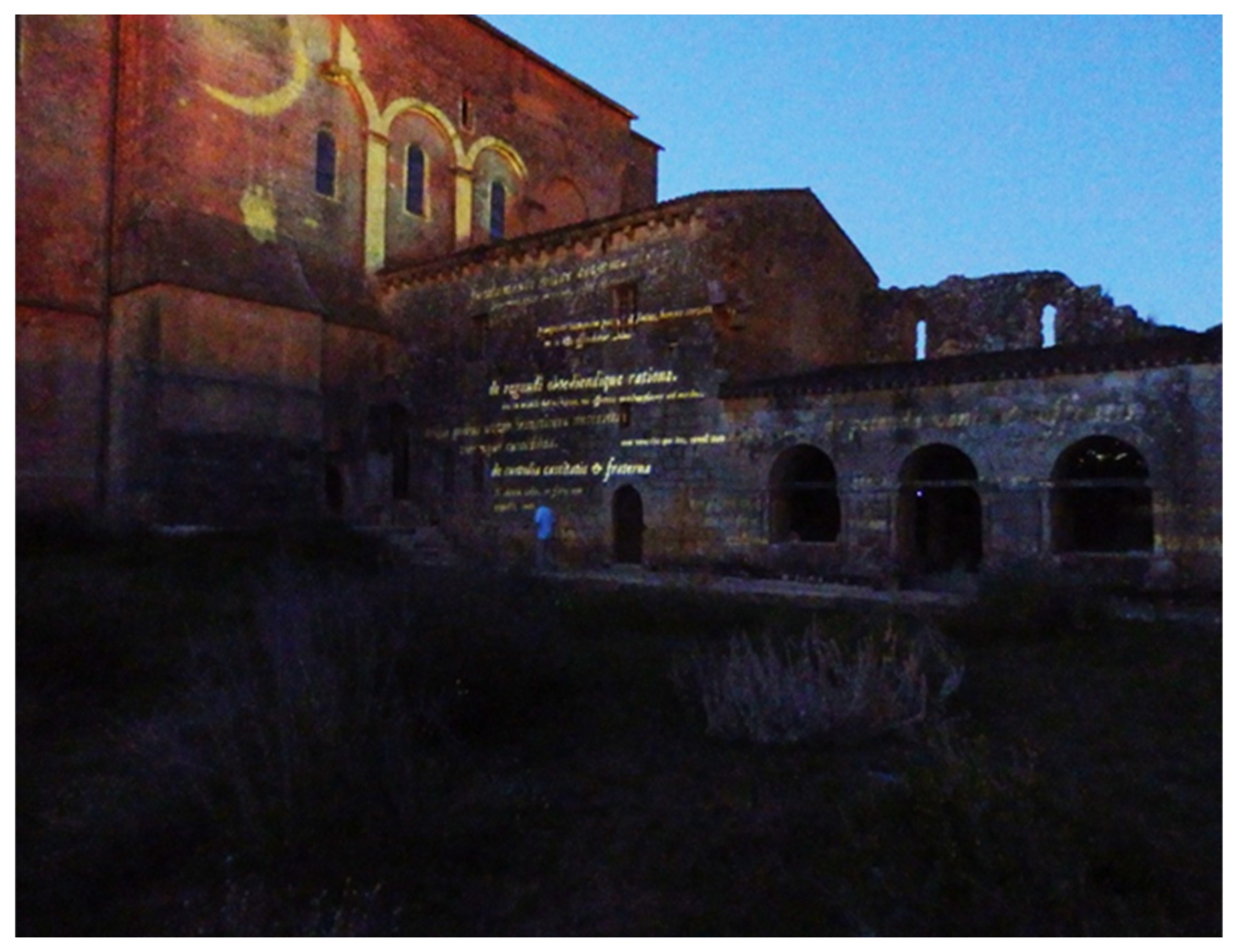

The award-winning lighting installation at Saint-Avit-Sénieur in France designed by lighting designer Lionel Bessières of Quartiers Lumières is selected as the first case study that exemplifies best practice in lighting design: best example relative to alternatives usually having been designed to fulfil certain purposeful ends (Given, 2008). The site being designated as a World Heritage Site enabled easier access to information from the local government regarding visitor demographics to the site before and after the lighting installation. Additionally, the permanent nature of the lighting installation enabled better site access to gain deeper insights into the status of the installed lighting system. Saint-Avit-Sénieur is a commune located in the department of the Dordogne in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of southwestern France. The most prominent attribute of the village is the large church dating back to the 11th or 12th century. An abbey dedicated to the hermit Avitus was constructed adjacent to this church.

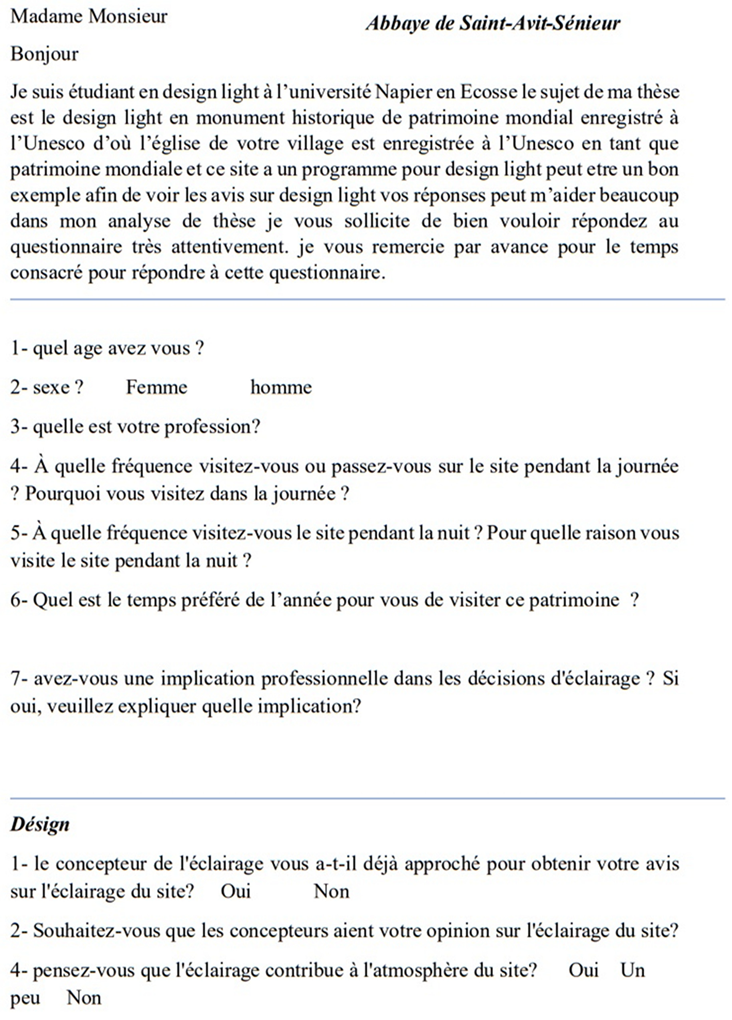

The lighting scheme was inspired by a poem written by Paul, which embraced the architectural components of the village, its historical features, and its heritage-related and seductive qualities based on the spiritual nature of poetry. Murmurs of light are created by the distinctions between light and dark, past and present, reality and poetry, and culture and nature. Illumination of the western side of the abbey is achieved using 250W LED projects, which are intended for extended use in outdoor environments and are capable of producing appropriate chromatic lighting and projecting “gobos” for tracking particular objects. The video projectors display a fresco of animated images, which portray the myth of Saint-Avit-Sénieur and the history of the place as shown in

Figure 1.

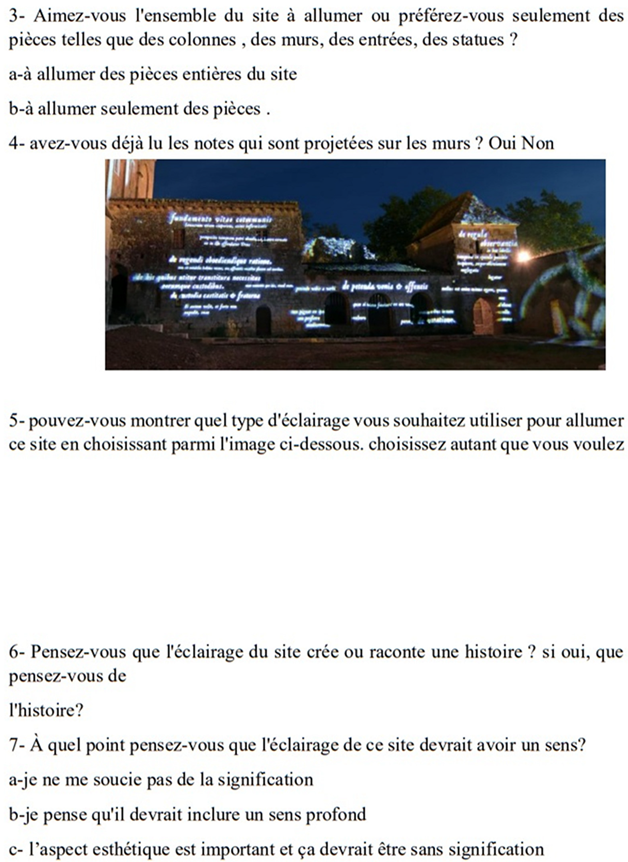

IP65-rated Gobo LED 80 D projecters and LED cutting projectors capable of projecting an intense and precise depiction of graphic designs coupled with Digital Multiplex (DMX) controls are used to project calligraphy and palimpsests onto the wall of the abbey as shown in

Figure 2. Soundtracks comprising extracts from the rules of the chapter in Latin are played using speakers in the water well. The well’s surface is covered by a metal lock with laser cutouts that tell the story of the legend. The colour temperature of this section of the abbey is against the west side of the church and this colour contrast is not generated such that it reflects the history or the buildings on the site. So, while this part is lit with blue lights as shown in

Figure 1, the main colour of the west side of the church is red as shown in

Figure 2. Another design specification within this section is such that the calligraphy and poems projected using the light of the rulebook are unclear and difficult to read. It therefore seems that the poems were not intended to be read, but instead serve as accompaniments with soundtracks of the same poems, thereby giving rise to an atmosphere for the visitors. A 5-minute video montage displays dreams on the wall of the cloister and the transept of the abbey, where these light whispers are accompanied by sound creations.

The equipment used in this project is designed to be reversible in consideration of the value of the site. The equipment used on this site is of high quality considering the permanent use of the lighting scheme. This study’s data collection was undertaken almost four years after the installation. Despite the length of this period between installation and data collection, all the equpiment were completely functional demonstrating their well-suitedness to the site.

2.1.2 Case Study Two: Naghshe-Jahan-Square lighting Features:

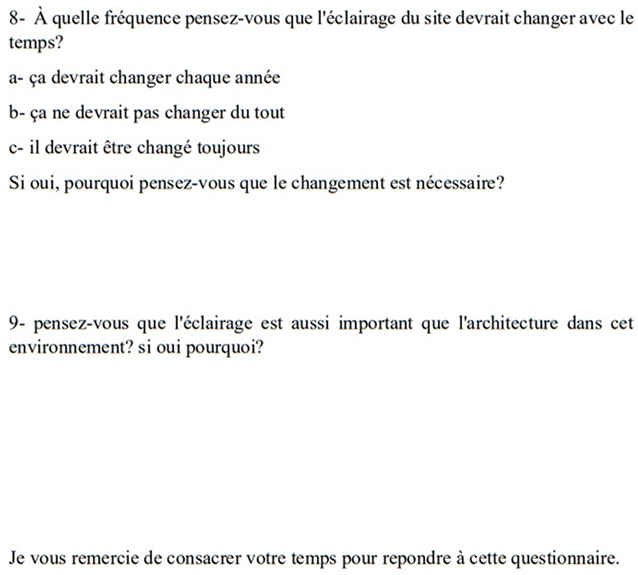

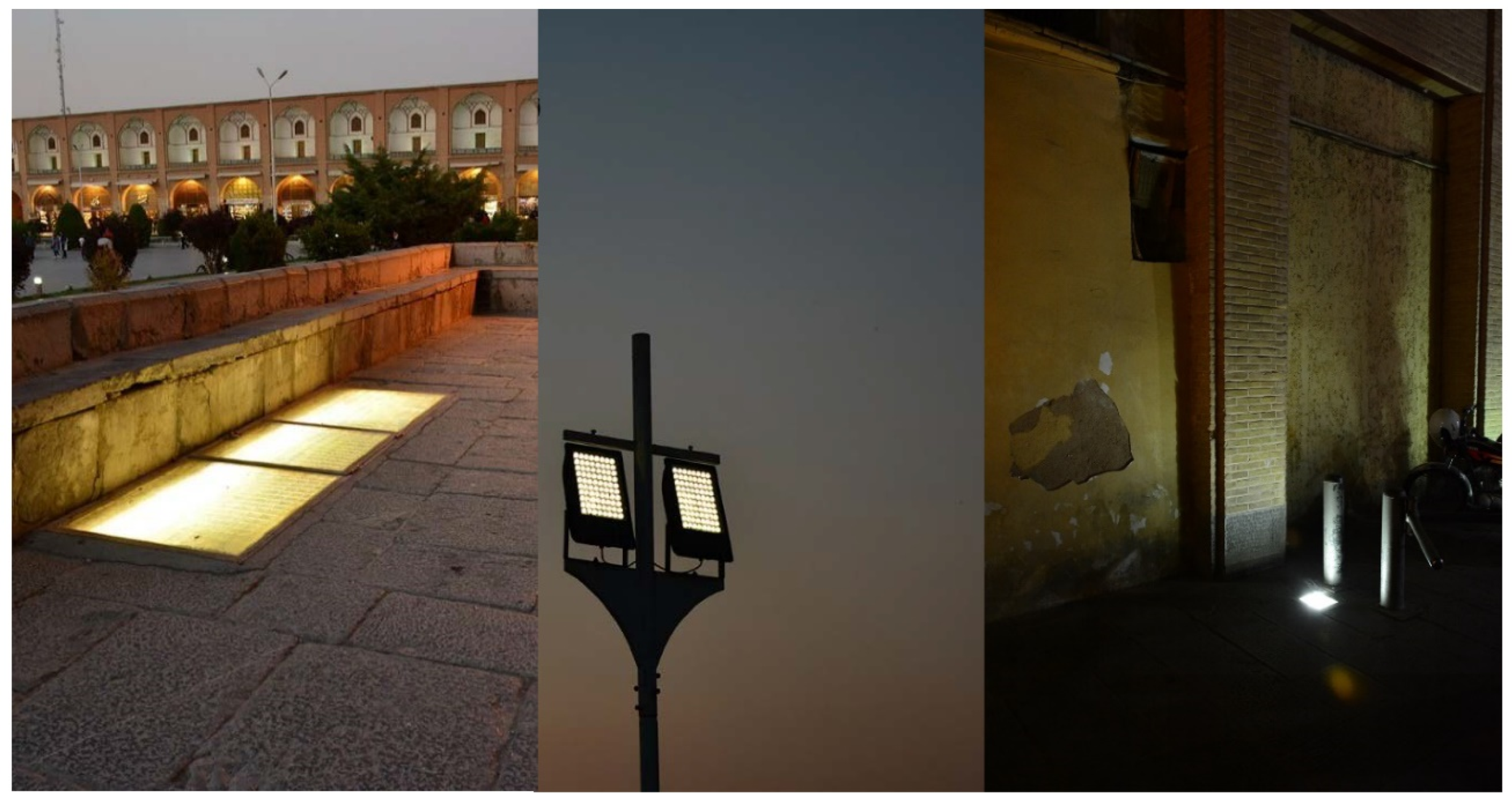

Naghshe-Jahan-Square in Isfahan, Iran is selected as the second case study given its designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site that includes existing lighting schemes for the surrounding bazaar, buildings and landscape (Zeini Aslani et al., 2022). Naghshe-Jahan (literally translates to ‘Image of the World’) is an open urban square located in the centre of the city. It is one of the largest urban squares in the world and is highly representative of both Islamic and Iranian architectural design. The site is illuminated from the light emanating from public lighting installations such as lighting from the shops and historic structures surrounding the square as shown in

Figure 3. Nearly 60 pole-mounted luminaires with high-pressure sodium lamps serve as the main source of lighting for the square as shown in

Figure 4. The quantity of light provided by luminaires is less than 5 lux, which seems insufficient even in relation to the basic functions of safety and accessibility. Many areas are left dark without any specific functionality or purpose. For instance, in the grassy landscape in the centre of square, one area is lit while the neighbouring area is left dark. The lack of light in such areas leads to reduced visibility, giving rise to safety issues and reduced accessibility in some areas. Many of the luminaires are conspicuous from the site, which is not in sync with the historical architecture of the site. Additionally, the high altitude and the inappropirate beam angles of the light sources results in issues such as glare and light pollution. Overall, the centre of the site is darker than the historic building’s surroundings. Observers standing in the centre of the square are pretty much in darkness, as the rest of the square is brighter.

The main lighting of the site is from the light spilling from the shop windows, rendering the rest of the historic site close almost invisible at night as shown in

Figure 3. Shops are located all around the site, and every shop is lit with various qualities and quantities of indoor and outdoor light. There are no set regulations or guidelines regarding the lighting of the shops in terms of quality or quantity, as each shop has its own lighting scheme with the aim of attracting customers. As a result, the lighting in these shops differ in terms of brightness, colour temperature and light colour, with little harmony. The historic buildings and even the landscape of the site appear much darker than the shop windows. shop windows

The floor above the shops featuring several arch-shaped terraces are floodlit with cool light, which stands in contrast with the warm lighting installations used in most of the shop windows as shown in

Figure 3. Although this contrast helps in making the square visible at night, some of the light sources are malfunctioning, meaning that some of the terraces are plunged in darkness at night or less visible than others. The high-gloss and reflective floor of the site reflects the lighting of the shop windows thereby exposing observers to increased light levels. This high level of contrast and glare makes it difficult to perceive the site landscape, which the primary area for picnics and socialising.

Bollards of different heights serve as the key source of illumination for the landscaped areas as shown in

Figure 4. However, glare seems to be the main issue with these bollards as it was observed that many visitors picnicking on site covered the luminaires with bags or clothes to reduce the glare. As some these bollards are as high as a seated person, it resulted in the source of light being exactly at the level of vision. Furthermore, it was observed that people sat closer to the low-height bollards in order make use of the light emitted while still covering the source of light as already noted to reduce the glare, probably due to due to the low level of illumination in the landscaped areas, which was measured at an average of 1 lux.

The Naghshe-Jahan-Square has architectural features that are decorative and colourful, which include the blue ceramic tiles of the entrance of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque and the dome ornamented using both glazed and unglazed cream-coloured tiles. The Royal Mosque is mainly decorated with seven-colour mosaic tiles and calligraphic inscriptions, which are mainly blue in colour along with stone carving in parts. Other parts of the square are also decorated with cream coloured tiles and other decorative features, such as paintings.

While each of the historic buildings within the site have been illuminated, the lighting seems very haphazard and ill-planned. For example, some parts of domes are illuminated using LED light sources, while other parts are illuminated using metal halide light sources. The main technique for illuminating all these buildings is floodlighting, using high-powered light sources. It was observed that the architectural features and other specific characteristics of the historic site were not given much consideration, resulting in evident problems such as glare and the colour rendering of these features as shown in

Figure 6. For example, the Persian Blue tiles at the entrance of the Royal Mosque which should ideally be highlighted with lighting at night, have a rather flattened and pale look from the existing floodlights. Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque is subject to the same problem as the dome seems to disappear towards the very top during the night because the floodlighting only illuminates parts of the dome. Dirt depreciation, glare and light pollution are some of the other problems associated with the floodlights on site as shown in

Figure 5.

2.2 Observations

Observation is considered as one of the main methods to gain an understanding of peoples’ behaviours within different settings (Bechtel et al., 1987; Aktinson & Hammersley, 1998). Each of the two case studies made use of behavioural observation with a view to develop an understanding of people’s behaviours within the historical sites. One of the researchers participated as a marginal participant in this observation process by merging into the research field of both the case studies, thereby making it less likely for the people at these sites to notice that they were being observed (Nasar, 2007). This behavioural observation provided information and understanding about the existing lighting scheme and how this influences people’s connection and interaction amongst themselves and within the site. After the process of behavioural observation, a process of focused and selective observation was developed to support this observational data through interviews (Angrosino & Mays, 2000). The people visiting the site were made aware of their status as research participants and interviewed to collect additional data about their personal experiences and perceptions about the two sites.

2.3 Interviews

Interviews are qualitative data collection methods that involve extensive discussions where participants provide flexible, free and spontaneous answers about their personal perceptions and experiences about particular topics (Barbour & Schostak, 2005; Dörnyei & Skehan 2003). Semi-structured interviews have been conducted across four different stages of this research. The first stage, conducted before visiting the case studies, involved interviews with eight lighting designers to gain their opinions on the lighting of urban historical spaces and how lighting in these spaces can result in a sense of place amongst locals and visitors. The statements made by lighting designers in the first stage interviews were used as a basis for formulating the interview questions for the second and third stages, conducted during the visit of these two case studies, involving interviews with the locals and visitors. The fourth stage, conducted after visiting the two case studies, involved interviews with four heritage site experts in relation to historical sites and cultural heritages. None of the lighting designers or heritage site experts were required to visit any of the case studies, and the same researcher interviewed all the participants.

The first and fourth stages of interviews involving lighting designers and heritage experts respectively were inspired by the snowball sampling method where the first set of participants are recruited from known acquaintances (Burns, 1993). Lighting designers and heritage experts with relevant experience and portfolios were approached and invited to participate in the interview. During the course of the initial interviews, these participants were requested to refer other designers or experts in the field to initiate a gradual snowball-like process (Polit & Beck, 2006). This method is less time consuming while providing better opportunities for communication with the participants. The second and third stages of interviews involving locals and visitors of the two case study sites was inspired by a random sampling method so as to remove any bias while selecting a representative sample (Gravetter & Forzano, 2011). This random sampling method was convenient considering the need for generalizing the results of this research to a wider population.

Table 1 illustrates the participant demographics for the four-stage interviews. A written questionnaire in French language was used for interviewing participants of the first case study considering the fact that most participants’ native language was French. Given the interviewing researcher’s non-proficiency in French, the only method of interviewing participants was to write and present pre-designed questions in their native language. Therefore, a questionnaire with a series of questions was formulated in the native French language. All the four-stage interview questions are presented in Appendices A to D.

2.4 Data Collection and Analysis

All the qualitative data collected through behaviour observation and interviews is collated and categorised based on applicable and evident themes using thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is a broadly used method for analysing data in qualitative research and remains a relatively underappreciated method in comparison to ethnography, grounded theory and phenomenology, which can be used widely to respond to a range of research questions (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This method is designed to identify, analyse, organise, describe and report on themes, and establish patterns that are found within a data set. Themes are identified by transcribing the interviews with the lighting designers so as to establish best practices in lighting design for historical sites in the first stage. Subsequently, patterns about how the lighting schemes for such sites should be approached are established from the behaviour observation and interviews with visitors of Saint-Avit-Sénieur and Naghshe-Jahan-Square in second and third stages respectively. Finally, these patterns are validated by transcribing the interviews with the heritage experts in the fourth stage.

3.0 Results and Analysis

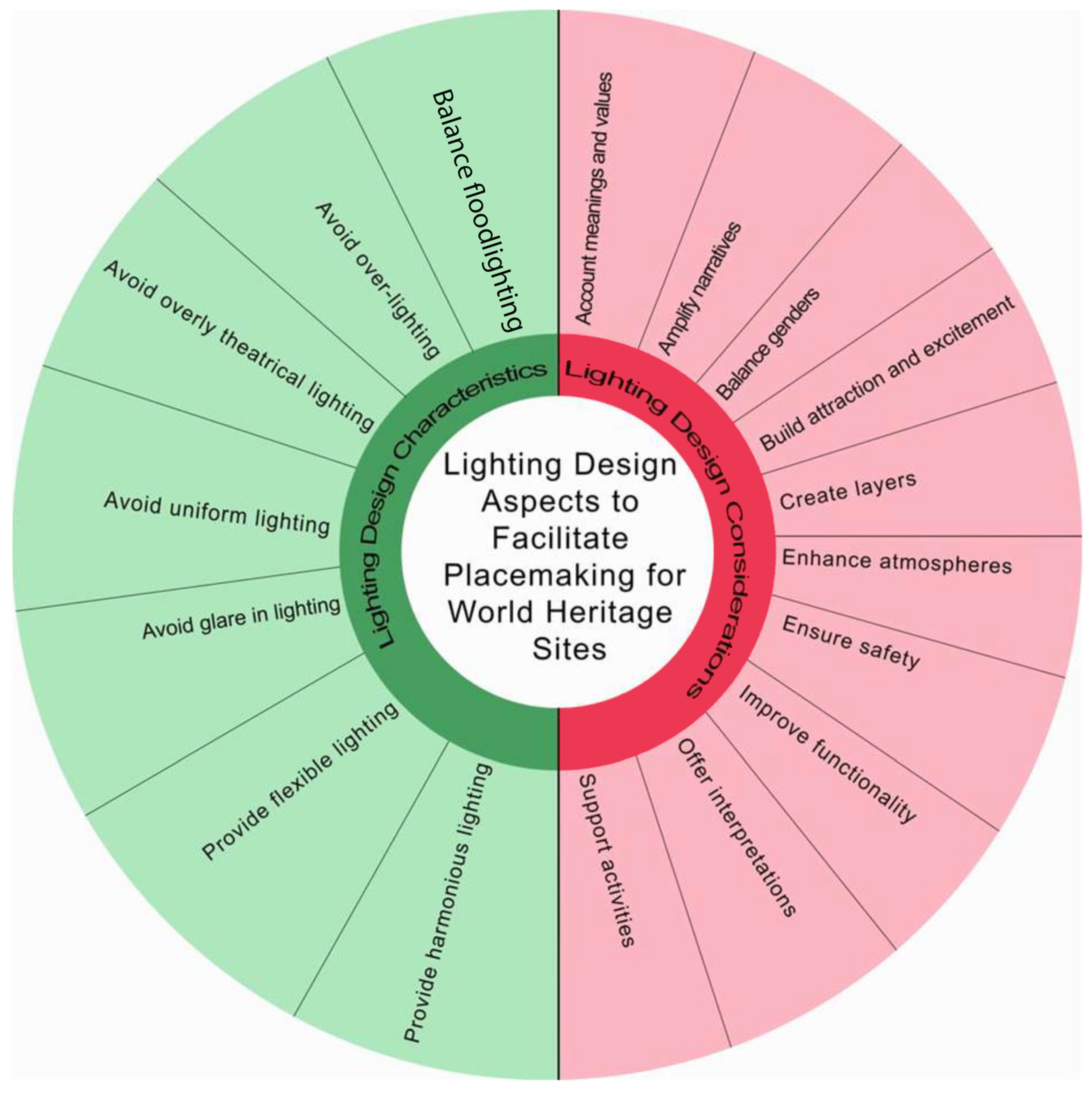

The data collected from the first stage of interviews with lighting designers enabled the identification of two broad sets, namely: lighting characteristics and lighting design considerations. The lighting designers mentioned several lighting characteristics and lighting design considerations that can be altered in relation to historic sites, which were used as the base characteristics and considerations. No regulations have been suggested as it is recommended that the application of these characteristics should be completely dependent on the historic sites’ architectural and cultural features as well as location. The data collected from the observations and, second and third stage of interviews with people visiting the two case study sites either supported these base characteristics and considerations or enabled the identification of additional characteristics and considerations that can be applied across all historic sites. Finally, the data collected from the fourth stage of interviews with heritage site experts is used to validate these characteristics and considerations for facilitating placemaking process in World Heritage Sites.

3.1 Lighting Characteristics

The lighting characteristics obtained from the thematic analysis include: avoiding over-lighting, overly theatrical lighting and homogeneous lighting; balancing floodlighting; preventing glare; providing flexible and harmonious lighting.

3.1.1 Avoid over-lighting

Over-lighting of elements either within the historic site or its surrounding areas can adversely affect the perception of the site. Over-lighting as described by the lighting designers is both in terms of using excessive brightness as well as excessive number of luminaires than what is generally required for visibility and accessibility. One lighting designer expressed concerns relating to over-lighting by stating that: “For me, with a lot of historic cities, sometimes the lighting is too much. Where that sort of element of surprise and delight [is] lost by the way in which the illumination [is] carried out.” Another lighting designer also expanded on these concerns by stating that: “We are sometimes confronted with projects where the expectation is to make things very strong and very bright to show that it's an affluent society.” It was observed that the shop entrances at Naghshe-Jahan-Square site were overly bright, which made the landscape appear dark and unsafe for many participants. Over-lighting can result in people perceiving neighbouring areas as unsafe due to the reduced illumination (Isenstadt et al., 2014).

3.1.2 Avoid overly theatrical lighting

Overly theatrical lighting can be misinterpreted at historic sites. Overly theatrical lighting as described by the lighting designers is the excessive use of coloured or dynamic light. In this regard, a lighting designer explained this type of lighting has the potential to “completely change the identity, character and expression of [the] building.” It can be interpreted as lighting that comprises an exaggerated or as another lighting designer defines, “excessive use of colour or dynamic lighting.” While yet another lighting designer mentioned this type of lighting “often destroys any sense or place.” Although such lighting may seem exciting and interesting to tourists, it can adversely affect the authentic sense of place in historic sites (Zeini Aslani, 2022). It is important to strike a balance because little colour variation can result in a dull space while too much variety across different colours and moving lights can also result in visual clutter (Hong, 2007). Too much sensory stimulation in a setting can result in sensory exhaustion (Nasar, 1990).

3.1.3 Avoid homogeneous lighting

Homogeneous light should be avoided at historic sites. Participants of the Naghshe-Jahan-Square site out of their own free will mentioned that homogeneous lighting is not appropriate, as it does not add anything positive to the historic site. While most participants expressed their views about homogeneity in a direct manner, a few participants expressed views in a more indirect manner. For example, one of the participants mentioned, “the homogeneity in lighting here makes me feel there is no design to it. It’s just lights to make [the site] visible” while another participant indirectly pointed to the lighting and mentioned, “I think it’s boring, there’s no excitement, no focus”. People generally tend to prefer heterogeneous lighting (Kobayashi et al., 2001). Although homogeneously projected lighting on building facades recreates the appearance of the building in daylight by enhancing the details of the architecture, (Zeini Aslani, 2022), homogeneous lighting in urban environments is not an ideal option because contrast and heterogeneity is preferable in terms of the ability to enhance experience and visibility (Clanton, 2014).

3.1.4 Balance floodlighting

In historic sites, it is important to emphasise certain points and highlight specific features for creating an atmosphere while focusing attention and interest by balancing floodlighting with other forms of lighting. One of the lighting designers described the use of floodlighting as a bad choice for historic buildings: “Bad lighting is usually old-fashioned floodlighting, using either very cold or very warm light sources. This might [illuminate] a building but [it] is likely to lose its character and materiality”. Floodlighting results in a portrayal where the character, identity, and materiality of historic sites are lost as shown in

Figure 6. Floodlighting was introduced by UNESCO to historic sites in the 1970s, when the aim of illuminating such sites were very different (Santen, 2006; Ünver, 2009; Pingel, 2010). Natural white floodlights are suggested for buildings even by UNESCO, for allowing as much of the site to be presented as possible by brightening the entire site and enhancing the architecture (Zakaria et al., 2018). However, the interviewed lighting designers are generally of the opinion that floodlighting is largely old-fashioned. Lighting in historic sites should be constructed so as to illustrate the unique and valuable characteristics of the identity of the site (Joels, 2006). Floodlighting alone is not suitable for historic sites as it merely brightens the entire space (Peters, 1992). Many of the floodlighting schemes have been or are in the process of been phased out because of their poor efficacy and non-compliance with European Directives due to the tendency of being replaced with LED systems (Historic England, 2019)

3.1.5 Prevent glare

Glare must be prevented at all costs. Participants from the Naghshe-Jahan-Square had several views about glare such as: “We try to find a light to sit close to, but then it’s causing so much glare that we have to cover it”; “The light sources are too bright, in this dark place, they literally blind your vision and don’t let you see further on.” There are two different types of glares, namely: discomfort glare and disability glare (Ludt,1997). Disability glare occurs when the visibility degree of objects is reduced as a result of an extreme bright light source in the field of view (Bullough et al., 2008). Disability glare seriously impacts visibility by negatively affecting peoples’ ability to see objects. Glare arising from the bollards is a major source of annoyance for the participants of Naghshe-Jahan-Square site as shown in

Figure 7.

3.1.6 Provide flexible lighting

Flexible features offered by modern lighting technologies provide the option of radically changing what is projected on a site project, which can be used as a lighting feature for historical sites on special occasions. Participants across both case studies are very appreciative of such flexible features offered by the lighting. Many participants interviewed in Saint-Avit-Sénieur mentioned that they appreciate the fact that, every now and then, the lighting of the site changes: “It makes you look forward to seeing something new in the next visit”; “It keeps you coming back.” Modern lighting technologies lend the desired flexibility over the design, resulting in better integration of light with the building and more dynamic lighting environments (Hong, 2007).

3.1.7 Provide harmonious lighting

Harmony in lighting should be with the meanings, narratives, and values presented in connection with the site. One of the heritage experts suggested the following: “All the design elements must have harmony together to build a great place. So, the architecture, the materials used, the colours, the light, they should all be relevant and in harmony. […] This doesn’t necessarily mean using the exact same colours for instance, but even if different colours are used, they should not destroy the harmony and visual aspects of the architecture.” However, this may limit the use of light colours in the historic site and prevent taking full advantage of the range of opportunities that light can offer to build new experiences during the night as shown in

Figure 8. Harmony has a positive influence on peoples’ behaviour in a space as it increases meaning and the understanding of the space, resulting in an increased sense of pleasure (Garaus, 2017). Lighting strategies should focus on building spaces that combine brightness, harmony, and wellbeing. Such lighting provides aesthetic improvement resulting in higher quality of life (Zeini Aslani, 2022). Colour of light should be in harmony with the material used in the architectural settings (Górczewska, 2011).

3.2 Lighting Design Considerations

The lighting design considerations obtained from the thematic analysis include: accounting meanings and values; amplifying narratives; balancing genders; building attraction and excitement; creating layers; enhancing atmospheres; ensuring safety; improving functionality; offering interpretations; and supporting activities.

3.2.1 Account meanings and values

Meanings and values of historical sites can be accounted and presented with the lighting. One heritage expert was of the opinion that the meanings within places should be considered in the process of placemaking: “People love their spaces. And they have real meaning to them. And I think […] the temporary events that take place should be [conducted] to try and reflect those.” While a lighting designers raised the specific claim that we should have “awareness of meanings before designing.” Even literature reveals that the design process should account the meanings and values of the specific site (Rapoport, 1990; Sime, 1986; Relph, 1976; Najafi & Shariff, 2011). However not much information has been found on how lighting should account these meanings and values in the design process. The interview responses from participants of Saint-Avit-Sénieur and Naghshe-Jahan-Square sites reveal that both sites hold rich cultural or religious meanings and values for the people. And accounting the meanings and values of Saint-Avit-Sénieur site has led to much success with its lighting installation. Therefore, lighting designers should consider the deep cultural and religious meanings and values of the historical site by studying the people and their behaviour with the site so as to account them in the design.

3.2.2 Amplify narratives

Narratives of historical sites can be crafted and presented in the form of stories through lighting. One lighting designer explains, “light has the ability to help tell stories.” While another lighting designer cites examples such as, “there may be a poem in your literature that talks about this place. I bet there is a story or a legend. If there is a legend that talks about this place, you could use that as a basis of your lighting time [and] amplify the narrative. […] Maybe there's some visions in this legend. Maybe there's […] a story that includes this place.” A heritage expert also commented that “lighting has significant potential for providing narrative and drama.” Lighting is an excellent storytelling tool; (Hansen & Triantafyllidis, 2015) and if used in the form of a compositional system like poetry, can influence what is been perceived (Dugar, 2018). Spaces that define humans’ historic preferences create a narrative theme; daily requirements create a descriptive theme; and future aspirations create a suggestive theme (Papakammenou, 2019). Amplifying the narrative of Saint-Avit-Sénieur site has led to much success with its lighting installation as shown in

Figure 9. Therefore, amplifying the narratives of historical sites should be a fundamental consideration in the lighting design process.

3.2.3 Balance genders

Gender requirements can vary especially in terms of lighting historical sites. Data obtained from both case studies reveals that illumination levels that allows women to feel safe is different from that for men. While all participants on both sites did agree that the users’ safety is an important feature for lighting, all the female participants in the Naghshe-Jahan-Square made the claim that the lighting does not consider their safety. One of the female participants mentioned, “They haven’t considered female visitors. It’s too dark. We don’t feel secure if we come alone”. Even many of the male participants in Naghshe-Jahan-Square agreed that the site may feel unsafe for female users. All participants of the Naghshe-Jahan-Square mentioned that there are too many spaces left in the dark, yielding a sense of a lack of safety for female visitors. On the contrary, all participants of the Saint-Avit-Sénieur mentioned that the lighting has considered the needs of all ages and both genders. Furthermore, no concerns regarding gendered issues were raised before the questions regarding this issue were brought up directly in Saint-Avit-Sénieur. Even literature reveals that young women’s mobility can be limited or restricted to certain areas during the night due to lighting (Zeini Aslani, 2022). Therefore, balancing gender requirements should be an important considering while lighting historical sites.

3.2.4 Build attraction and excitement

Attraction and excitement within historical sites can be built with lighting. Making the site attractive and exciting was emphasised by the participants interviewed across both the sites. Majority of the participants interviewed in Naghshe-Jahan-Square mentioned that the current lighting scheme does not add any attraction to the site, while also voicing that lighting should bring something new and exciting to the site at night. One participant commented, “The lighting here is really dull. It doesn’t make anything here more attractive than it is during the day, I mean, it could make the place more attractive, couldn’t it?” Majority of the participants interviewed in Saint-Avit-Sénieur, on the other hand, mentioned the uniqueness of the lighting makes the site attractive and worth visiting at night: “We love the site anyway, but I can’t hesitate [in stating] that one of the reasons we come here at night is how exciting it looks now with the lighting.” Physical features within historic sites influence whether the site can become attractive or not for visitors (Papakammenou, 2019). Therefore, it is an essential consideration for making sites enjoyable and vibrant through lighting design schemes (Historic England, 2019).

3.2.5 Create layers

Creating layers within a historic site can lead to highlighting interesting architectural features that attract more attention while other features can be left in the dark, thereby providing a fresh portrayal of the site as shown in

Figure 10. One lighting designer explains, “We will accentuate [a specific part of the building] if we light this up. It brings importance. It brings respect. If we light this up, it brings importance. If we don't light this up, we’ve decided it's not so important. So, you're going to create a

scenography.” Another lighting designer suggested the following: “Pick out historic features with the lighting, that [are] less prominent during the day, so you [are] creating a totally different scene.” Lighting of a site is achieved through the composition of multiple layers of light, resulting in a complex lighting scheme that concurrently develops a three-dimensional narrative, descriptive and suggestive theme (Papakammenou, 2019). Lighting in urban spaces needs to have contrast to make the space more interesting (Seitinger & Weiss, 2015). Lighting should create a visual hierarchy, which can be realised through creating contrasts amongst the brighter and shadowed areas with light, the creation of layers with light, as well as the link between the lit and the adjacent areas (Hong, 2007). Shadows also play an important role in the lighting of historic sites.

3.2.6 Enhance atmospheres

Atmosphere of a historical site can be enhanced with lighting. One heritage expert emphasised that lighting should “enhance the atmosphere of the built environment and change the nature of the place.” While another heritage expert contributed further to this idea: “By creating a good atmosphere with light at night, we can [transmit] information to visitors.” Lighting is capable of enhancing atmospheres (Cochrane, 2004). Atmospheres can influence people by harmonising their mood and simultaneously extending that mood (Böhme & Thibaud 2016). Being absorbed into joyful atmospheres facilitates an experience that is more cooperative, emotionally participative and socially integrated (Stevens, 2007). The lighting in Naghshe-Jahan-Square not only fails to enhance the atmosphere, but also dulls the original atmosphere of the historic site due to the inappropriate lighting poles and old-fashioned floodlighting. Therefore, lighting designers should have extensive knowledge about creating atmospheres that can transform the setting through light (Laganier & van Der Pol, 2012).

3.2.7 Ensure safety

Safety is always an important consideration while designing lighting schemes for historic sites. Participants from both case studies expressed the opinion that as well as providing actual safety, it is also important to make people experience a sense of safety in these sites. A participant in Naghshe-Jahan-Square stated the following: “I always only use the main streets to reach the square, although the historic ones on the southern side have lots more character. But you don’t know what you might see in the dark as you go through them!” Safety was the primary reason for lighting urban spaces and streets until the 1970s (Meier et al., 2014). An important feature of lighting is to provide a feeling of safety within spaces (Narboni, 2004; Najafi & Shariff, 2011; Seitinger & Weiss, 2015; Cochrane, 2004). Safety of a space is an important parameter for cultivating a sense of place (Seitinger & Weiss, 2015).

3.2.8 Improve functionality

Functionality of historical sites can be improved with lighting. One of the heritage experts commented: “We need to know exactly what is surrounding the site. Say, if the site is historic, is it surrounded with handicraft shops? restaurants? Greenery? These need to be studied so we know what we need to consider within the site as well.” Although, the Naghshe-Jahan-Square site is situated in a busy part of the city with many linking streets, only two main streets from either side were observed to have sufficient lighting for people to enter the square. The remaining streets with a more historic character were mainly observed to have insufficient lighting. The interviewed participants expressed their reluctance in using these remaining streets due to the insufficient lighting. A key attribute of successful places is the accessibility to their surroundings and any other important places nearby (Project for Public Spaces, 2018)

3.2.9 Offer interpretations

Interpretations are offered by the lighting of historical sites. One lighting designer mentioned, “As soon as you are lighting a space, you create a place because you are interpreting it.” Another lighting designer commented, “You can interpret the site in a new way, it's not daytime.” Another a lighting designer commented, “You're making statements about what is valued by people, what's valued by different people, and what is valued… you're interpreting at me.” Every lighting scheme conveys a message from its designer, client and site, and people interpret this message based on their culture, expectations, and the context (Meier et al., 2014). People perceive environments differently based on the architectural features as well as cultural backgrounds, and thus the manner in which the same lighting design of a site is interpreted may differ (Dugar, 2018). Accordingly, when specific features are lit and others are left dark, the lighting conveys that some parts are more important than others (Ünver, 2009). Therefore, lighting design should consider the architectural features of the historic site as well as the cultural backgrounds and expectations of the people visiting these sites.

3.2.10 Support activities

Activities within historic sites can be supported with lighting. One lighting designer voiced the belief that a bad lighting scheme fails to reflect the activities that will be engaged in on the site in question. A few other lighting designers also stated that special events within the city are activities that may inform the practice of lighting historic sites. The observations and interviews with participants in Naghshe-Jahan-Square site revealed night-time picnicking as a popular activity especially amongst families and younger generations as shown in

Figure 11. However, the lighting of this site is not designed to facilitate such activities as it was observed that many people covered the bollards to prevent glare or used portable lighting sources while seated in the unlit areas. Lighting must be designed for supporting peoples’ daily activities (Davoudian, 2019). When peoples’ activities are facilitated within a space, this provides them with a sense of place and reasons to re-visit that place (Project for Public Spaces, 2018).

4.0 Discussion

Placemaking process for historic sites can be facilitated with various lighting characteristics and lighting design considerations as shown in

Figure 12. Lighting can contribute to the composition of various elements within the built environment to convey a narrative. The narratives that lighting should present in the historic site should be derived from the history of the site. This story can influence how bringing or enhancing the meanings lying within the stories that relate to the historic site, thereby enriching the experience of visitors, perceives the site. Historic sites have specific meanings and values for people, and these must be considered in the design process. It should be noted that lighting design can convey an interpretation of the historic site. The architectural features of the site as well as the cultural background of the people influence the interpretations conveyed through the lighting. Thus, in addition to choosing a relevant and meaningful narrative presented by the lighting, the architectural and cultural features must be carefully studied to ensure that the projected narrative is in line with the desired meanings and values of the site. The lighting design should be crafted to create an atmosphere within the historic site. The overall mood can be harmonised to merge with the atmosphere created through the lighting design.

World Heritage Sites were chosen for this study is to make sure that both sites had already undergone certain evaluation criteria of historic sites necessary for this research. However, it should be noted that the placemaking aspects found as a result of this research can be applied to any other historic site. In fact, other historic sites do not necessarily have to follow the strict regulations of World Heritage Sites enabling more freedom for the lighting scheme. While both Saint-Avit-Sénieur in France and Naghshe-Jahan-Square in Iran are UNESCO designated World Heritage Sites, both have contrasting lighting schemes: Saint-Avit-Sénieur demonstrates best practice in lighting design; Naghshe-Jahan-Square on the other hand is judged as a less successful lighting scheme. Such contrast allows for a better understanding of the influence of lighting on historic sites. It is important to note that the two case studies were in two different contexts with obvious differences in terms of the people’s cultural backgrounds, the populations approaching the site, the usage and aim of visiting each site, and even the different architectural features of the site. These aspects might have influenced the responses of the participants. For instance, many participants in Naghshe-Jahan-Square were accustomed to using the site for night-time picnic, and accordingly wanted lighting to facilitate such a usage. On the other hand, Saint-Avit-Sénieur was used as a place to walk around, so the lighting requirements and expectations were different. Also, the two groups of participants had different cultural backgrounds and approaches about lighting. Light colour even had different meanings and values in the two different groups. These said, both groups with all their differences still pointed to very similar aspects in terms of the basic expectations from a successful lighting scheme they would expect in such setting.

5. Conclusions

The lighting characteristics and design considerations show that floodlighting and over-lighting cannot create a unique atmosphere for a historic site and will likely fail to provide any remarkable aesthetic or emotional response. Although half a century ago the general consensus was to light historic sites in a bold manner so as to enhance the architecture and draw as much attention as possible to these sites, the results of this study demonstrate that over-lighting the site and all its architectural features using floodlights must be avoided. Such an approach can also result in the historic building losing its character, identity and sense of materiality. Additionally, homogenous lighting tends to undervalue the specific features of a historic site. Instead, lighting must be used to create layers within the historic site. Lighting should enhance certain parts of the site using contrast between light and shadows so as to present the space in a more visually interesting manner, providing a place for people to explore and discover. A layered lighting approach can make the historic site more attractive and exciting for visitors. However, overly theatrical lighting is not recommended as excessive use of coloured or dynamic light can destroy the authenticity of the place by harming its sense of identity and character. Therefore, the attractiveness of a site should be built with lighting in a responsible manner by respecting the authenticity and values of the site. Flexibility of modern lighting features can also facilitate various outcomes without the need to change fixtures.

Lighting should be in harmony with the historic site as this yields an improved understanding and appreciation of the setting. However, harmony in lighting does not necessarily entail repeating the same colours that already feature within the architecture; rather, it involves developing a lighting scheme that is in harmony and in line with the meanings and values of the site, helping to convey the appropriate narratives. Lighting features should not result in glare. It is important to ensure that the installed lighting minimises the cause of any physical or visual discomfort for the visitors. Additionally, lighting should be designed to support peoples’ activities to ensure successful placemaking. It is also essential to consider functional aspects of the surrounding area and ensure that the site is accessible. Ensuring safety within the historic site is also a key consideration within the placemaking process. Additionally, feeling safe differs in a gender-informed way, with women visitors often voicing a preference for brighter spaces than men.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable guidance and contribution of Malcolm Innes, Kirstie Jamieson and Alison McCleery during the course of this research. The authors also gratefully acknowledge all the generous contribution of the heritage experts, lighting designers, and participants interviewed in the different sites. The authors also thank the anonymous reviewers who provided valuable feedback to improve the readability and overall academic quality of this paper.

Appendix A: Semi-Structured Interview for Lighting Designers

1a- Are you aware of how lighting schemes can be used in historic sites to enhance the environment?

1b- Does lighting have to represent the historic function of the site as it was used in the past?

2 - Should the experience at night replicate the daytime experience or should it offer something different?

3a- Do you think light can influence the identity of historic sites?

3b- Please explain how light can impact on the identity of historic sites?

3c- can you give me an example please?

4a- Do you think it is the role of the lighting scheme in historic sites to work as interpretation?

4b- Can lighting provide narrative and drama? In other words, can it tell a story or act as a theatre?

4c-can you give me an example?

5 -What do you think should be the priority in lighting for historic sites (Social, cultural or political)?

6- In the lighting of historic sites, which do you think is more important, lighting to create a space or lighting to create a place? Why?

7 -Which characters of light have the potential to change the identity of place?

8a- Do you think the lighting scheme for historic sites should be different from that for public spaces?

8b- If yes, what it the main approach to lighting schemes in historic spaces which makes this difference?

9 -Do you think light can influence the behaviour or mood of people? How?

10 -How important is the opinion of the local community and their culture in lighting design? Why?

11a- What do you think is the potential of lighting in historic sites?

11b- Can you think and some good examples?

12- Do you believe there is such a thing as bad lighting for historic sites? If yes, please explain.

13a-Do you think there is anything I should be asking?

13b-is there someone else I should interview?

Appendix B: Semi-structured Interview for Visitors of Case Study # 1 in Dordogne

Appendix C: Semi-structured Interview for Visitors of Case Study # 2 in Isfahan

THE PARTICIPANT

1 OCCUPATION___________________________

2 AGE________________

3 WHERE DO YOU LIVE IN THE CITY? (AREA)__________________________

4 HOW OFTEN DO YOU VISIT OR PASS THROUGH THE SITE DURING THE DAY? WHY DO YOU PASS THROUGH?

5 HOW OFTEN DO YOU VISIT OR PASS THROUGH THE SITE AT NIGHT?

WHY DO YOU PASS THROUGH?

6 WHAT TIME OF YEAR DO YOU MOST OFTEN PASS THROUGH OR VISIT THE SITE AND WHY______________________

7 DO YOU HAVE ANY PROFESSIONAL INVOLVEMENT IN LIGHTING DECISIONS?_____________

IF YES, PLEASE EXPLAIN WHAT CAPACITY______________________________________________

THE DESIGN

1 DID THE DESIGNERS OF THE LIGHTING EVER APPROACH YOU TO GAIN YOUR OPINION FOR THE LIGHTING OF THE SITE? (Y/N)

2 WOULD YOU LIKE THE DESIGNERS TO GAIN YOUR OPINION ABOUT THE LIGHTING OF THE SITE? (Y/N)

3 PLEASE SHOW WHICH PARTS OF THE LIGHTING ON THE SITE INTERESTS YOU MOST OF ALL BY NUMBERING THE BELOW PICTURES FROM ONE TO FIVE (1 MOST LIKED AND 5 LEAST LIKED)

4 HOW SUCCESSFUL DO YOU THINK THE LIGHTING SCHEME IS IN RELATION TO MATCHING THE SITE’S ENVIRONMENT?

5 DO YOU THINK THE LIGHTING CONTRIBUTES TO THE ATMOSPHERE OF THE SITE?

6 HOW DOES THE LIGHTING CHANGE THE SITE?

THE SITE

1 COULD YOU DESCRIBE THE ATMOSPHERE OF THE SITE DURING THE DAY?

2 COULD YOU DESCRIBE THE ATMOSPHERE OF THE SITE AT NIGHT?

3 HAS THE LIGHTING ON THE SITE ENCOURAGED YOU TO VISIT IT MORE AT NIGHTS?

4 DO YOU THINK THE LIGHTING ON THE SITE AFFECTS THE AUTHENTICITY OF THE SITE?

IF YES, PLEASE EXPAND ON HOW.

5 DO YOU THINK THE LIGHTING OF THE SITE IS DESIGNED FOR A SPECIFIC GENDER?

6 DO YOU THINK THE LIGHTING OF THE SITE IS DESIGNED TO BE APPRECIATED BY A SPECIFIC AGE?

7 Do you feel safe in the site? (y/n) HOW MUCH OF THIS FEELING OR NOT FEELING SAFE CAN BE ATTRIBUTED TO THE LIGHTING?

8 HAS THE LIGHTING ON THE SITE AT NIGHT GIVEN YOU A DIFFERENT EXPERIENCE AT THE SITE AT NIGHT COMPARED TO DAY? (Y/N)

9 HOW MUCH DO YOU THINK THE LIGHTING INSTALLATIONS ON THE SITE HAS ENCOURAGED TOURISTS TO VISIT THIS SITE?

VERY MUCH

SOMEWHAT

NEUTRAL

NOT MUCH

NOT AT ALL

10 WHAT ASPECTS OF LIFE DO YOU THINK A LIGHTING SCHEME SHOULD CONSIDER WHEN LIGHTING UP THIS SITE? CULTURE, POLITIC, RELIGIOUS, SOCIAL, HISTORY, TOURISM,

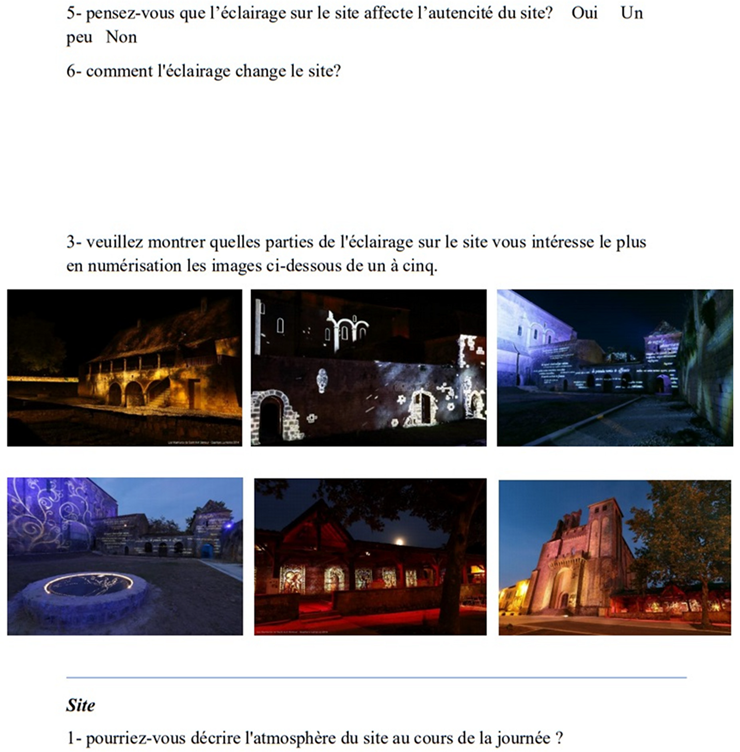

AESTHETICS

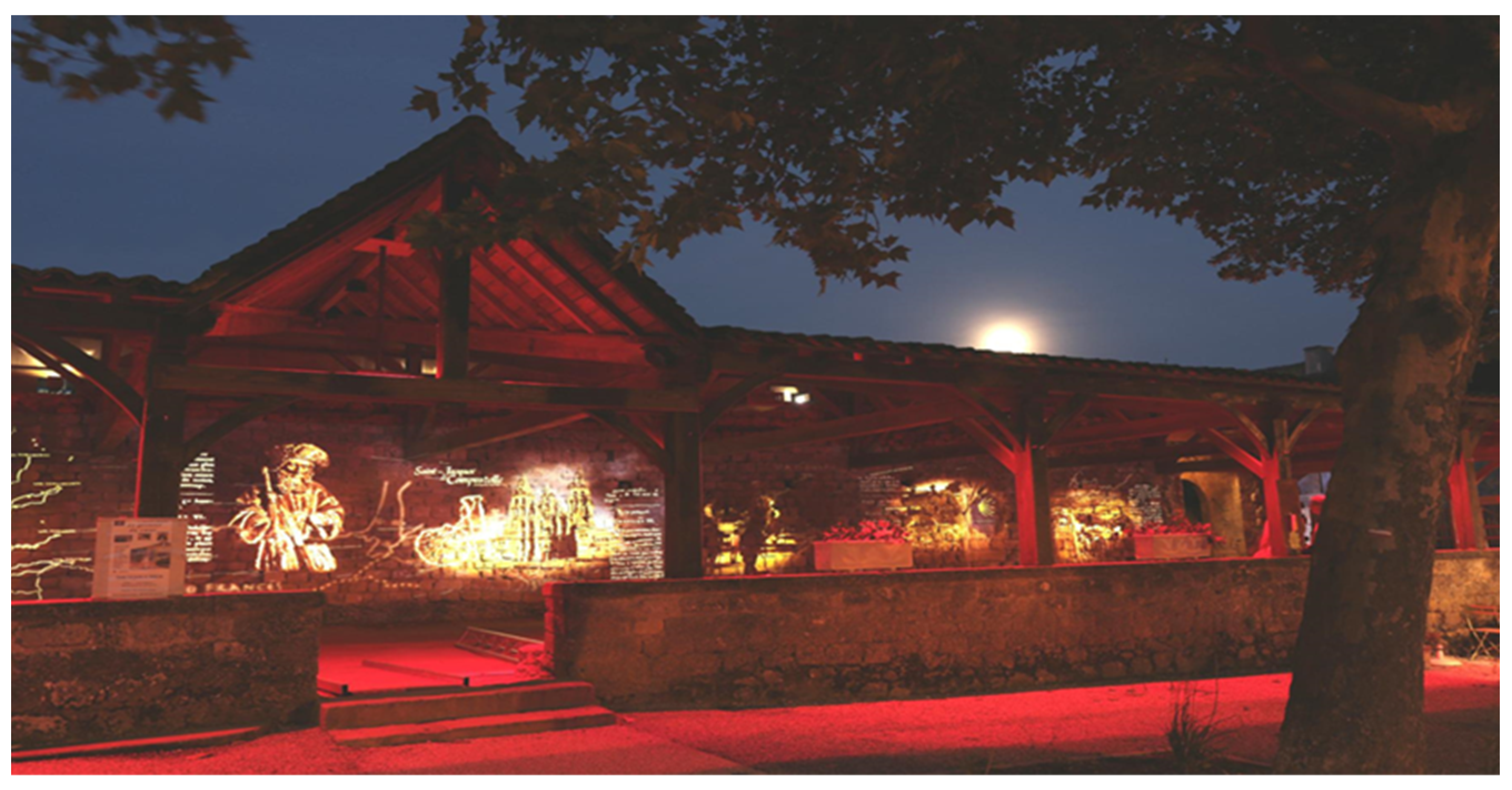

1 PLEASE SHOW WHICH OF THE BELOW LIGHTINGS YOU LIKE MORE (PLEASE CHOOSE ONE) (THIS QUESTION IS ABOUT COOL AND WARM LIGHT )

2 WHICH COLOURS DO YOU LIKE TO BE USED IN THE LIGHTING OF THIS SITE?

RED BLUE WHITE GREEN YELLOW…

3 DO YOU LIKE THE WHOLE SITE TO BE LIT UP OR WOULD YOU PREFER ONLY PARTS SUCH AS COLUMNS, WINDOWS, WALLS, ENTRANCE, CELLING,…. OF IT TO BE LIT?

WHOLE SITE

SITE’S PARTS (WHICH)

4 HAVE YOU EVER READ THE NOTES THAT ARE PROJECTED ON THE WALLS? YES/ NO

5 CAN YOU SHOW WHICH SORT OF LIGHTING YOU LIKE TO BE USED TO LIT UP THIS SITE BY CHOOSING FROM THE BELOW PICTURES (CHOOSE AS MANY AS YOU WANT)

(SHOULD INCLUDE FOLD LIGHTING, SPOT LIGHTING, 3D MAPPING,…)

6 DO YOU THINK THE LIGHTING OF THE SITE CREATES A STORY ?

IF YES, WHAT DO YOU THINK THE STORY IS?

7 HOW MUCH DO YOU THINK THE LIGHTING OF THIS SITE SHOULD HAVE A MEANING BEHIND IT?

I DON’T CARE ABOUT THE MEANINGS

I THINK IT SHOULD INCLUDE A DEEP MEANING

IT SHOULD BE MEANINGLESS

8 HOW OFTEN DO YOU THINK THE LIGHTING OF THE SITE SHOULD CHANGE OVER TIME?

IT SHOULD CHANGE EVERY YEAR

IT SHOULDN’T CHANGE AT ALL

IT SHOULD BE CHANGED ….

IF YES, WHY DO YOU THINK CHANGE IS NECESSARY?

9 26.. DO YOU THINK LIGHTING IS AS IMPORTANT AS THE ARCHITECTURE IN THIS ENVIRONMENT?

IF YES, WHY? |

Appendix D: Semi-Structured Interview for Heritage Experts

1a- Are you aware of how lighting schemes can be used in historic sites to enhance the environment?

1b- Does lighting have to represent the historic function of the site as it was used in the past?

2 - Should the experience at night replicate the daytime experience or should it offer something different?

3- Do you think light can influence the identity of historic sites?

4a- Do you think it is the role of the lighting scheme in historic sites to work as interpretation?

4b- Can lighting provide narrative and drama? In other words, can it tell a story or act as a theatre?

5 -What do you think should be the priority in lighting for historic sites (Social, cultural or political)?

6- What do you think is the potential of lighting in historic sites?

7- Do you think there is anything I should be asking?

8-is there someone else I should interview?

References

- Aktinson, P., & Hammersley, M. (1998). Ethnography and participant observation. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 248-261.

- Angrosino, M. V., & Mays de Pérez, K. A. (2000). Rethinking observation: From method to context. Handbook of qualitative research, 2, 673-702.

- Aslani, S. Z. (2022). Lighting design principles for placemaking in historic sites (Doctoral dissertation).

- Ball, R. (2014). Economic development: it’s about placemaking. European Business Review, 19.

- Barbour, R. S., & Schostak, J. (2005). Interviewing and focus groups (in Somekh, B. and Lewin, C.(eds.) Research methods in the social sciences. London & Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications, 41-49.

- Bechtel, R. B., Marans, R. W., & Michelson, W. E. (1987). Methods in environmental and behavioral research. Van Nostrand Reinhold Co.

- Böhme, G., & Thibaud, J. P. (2016). The aesthetics of atmospheres. Routledge.

- Boyce, P. (2013). Lighting quality for all.

- Brandi, U., & Geissmar-Brandi, C. (2007). Light for cities: Lighting design for urban spaces. A handbook. De Gruyter.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101. [CrossRef]

- Bullough, J. D., Brons, J. A., Qi, R., & Rea, M. S. (2008). Predicting discomfort glare from outdoor lighting installations. Lighting Research & Technology, 40(3), 225-242. [CrossRef]

- Burns, N. (1993). The practice of nursing research: Conduct, critique & utilization. WB Saunders Co.

- Carmona, M. (2021). Public places urban spaces: The dimensions of urban design. Routledge.

- Clanton, N. (2014). Opinion: Light pollution… is it important?. Lighting Research & Technology, 46(1), 4-4. [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, A. (2004). Cities of light: placemaking in the 24-hour city. Urban Design Quarterly, 89, 12-14.

- Davoudian, N. (Ed.). (2019). Urban lighting for people: Evidence-based lighting design for the built environment. Routledge.

- Dörnyei, Z., & Skehan, P. (2003). Individual differences in second language learning. The handbook of second language acquisition, 589-630. [CrossRef]

- Dugar, A. M. (2018). The role of poetics in architectural lighting design. Lighting Research & Technology, 50(2), 253-265. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, L., & Torcellini, P. (2002). Literature review of the effects of natural light on building occupants. [CrossRef]

- Ekrias, A., Eloholma, M., Halonen, L., Song, X. J., Zhang, X., & Wen, Y. (2008). Road lighting and headlights: Luminance measurements and automobile lighting simulations. Building and Environment, 43(4), 530-536. [CrossRef]

- Fine, G. A. (2003). Towards a peopled ethnography: Developing theory from group life. Ethnography, 4(1), 41-60. [CrossRef]

- Garaus, M. (2017). Atmospheric harmony in the retail environment: Its influence on store satisfaction and re-patronage intention. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 16(3), 265-278. [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. (1987). Life between buildings (Vol. 23).

- Given, L. M. (Ed.). (2008). The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Sage publications. [CrossRef]

- Górczewska, M. (2011). Some aspects of architectural lighting of historical buildings. Light in Engineering, Architecture and Environment, WIT Press, Southampton, UK, 107-118. [CrossRef]

- Gravetter, F. J., & Forzano, L. B. (2011). Research methods for the behavioral sciences, Stamford: Cengage Learning. Hare CE, McLeod J (1997). Developing a records management programme. London: Aslib. Herbert B (1998)." What Privacy Rights?". The New York Times. Op-Ed." In America". September, 27(1998), 27-28.

- Hansen, E. K., & Triantafyllidis, G. (2015, November). Storytelling Lighting Design (ST-LiD). In Interactive Storytelling: 8th International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling, ICIDS 2015, Copenhagen, Denmark, November 30-December 4, 2015, Proceedings (Vol. 9445, p. 404). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Hejazi, S. (2006). Sampling and its variants: introduction to research methodology in medical sciences. Tehran: Islamic Azad University.

- Historic England , (2019, September 11) . Resources to Support Place-Making and Regeneration, https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/planning/place-making-and-regeneration/.

- Hong, O. S. (2007). Design basis to quality urban lighting masterplan.

- Isenstadt, S., Petty, M. M., & Neumann, D. (Eds.). (2014). Cities of light: Two centuries of urban illumination. Routledge.

- Joels, D. (2006). Lighting design for urban spaces: Connecting light qualities and urban planning concepts (Doctoral dissertation, KTH).

- Johansson, M., Pedersen, E., Maleetipwan-Mattsson, P., Kuhn, L., & Laike, T. (2014). Perceived outdoor lighting quality (POLQ): A lighting assessment tool. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 39, 14-21. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S., Inui, M., & Nakamura, Y. (2001). Preferred illuminance non-uniformity of interior ambient lighting. Journal of Light & Visual Environment, 25(2), 2_64-2_75. [CrossRef]

- Laganier, V., & van Der Pol, J. (2012, September). Exploring lighting cultures-Beyond light and emotions. In Ambiances in action/Ambiances en acte (s)-International Congress on Ambiances, Montreal 2012 (pp. 721-724). International Ambiances Network.

- Ludt, R. I. C. H. A. R. D. (1997). Three Types of Glare: Low Vision O&M Assessrnent and Remediation..

- Lynch, K. (1984). Good city form. MIT press..

- Meier, J., Hasenöhrl, U., Krause, K., & Pottharst, M. (Eds.). (2014). Urban lighting, light pollution and society. Routledge..

- Meier, J., Hasenöhrl, U., Krause, K., & Pottharst, M. (Eds.). (2014). Urban lighting, light pollution and society. Routledge.

- Naderifar, M., Goli, H., & Ghaljaie, F. (2017). Snowball sampling: A purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides in development of medical education, 14(3). [CrossRef]

- Najafi, M., & Shariff, M. K. B. M. (2011). The concept of place and sense of place in architectural studies. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 5(8), 1054-1060.

- Narboni, R. (2004). Lighting the landscape. In Lighting the Landscape. Birkhäuser.

- Nasar, J. L. (1990). The evaluative image of the city. Journal of the American Planning Association, 56(1), 41-53.

- Nasar, J. L. (2007). Inquiry by Design: Environment/Behavior/Neuroscience in Architecture, Interiors, Landscape and Planning, John Zeisel, WW Norton & Co., New York (2006), 400pp., $34.95 (paperback), ISBN: 0-393-73184-7.

- Papakammenou V. Cross-cultural difference in the perception of facade lighting. (2019 September 11). http://www.cibse.org/ content/SLL/PapakammenouPaper.pdf.

- Peters, R. C. (1992). The language of light [Light in Place]. Places, 8(2).

- Pingel, F. (2010). UNESCO guidebook on textbook research and textbook revision. Unesco.

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2006). Using research in evidence-based nursing practice. Essentials of nursing research. Methods, appraisal and utilization. Philadelphia (USA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 12, 457-94.

- Porfyriou, H., & Sepe, M. (Eds.). (2016). Waterfronts revisited: European ports in a historic and global perspective. Routledge.

- Proctor, T. (2005). Essentials of marketing research. Pearson Education.

- Project for Public Spaces. “What Is Placemaking?”, (2018 September 15), https://www.pps.org/article/what-is-placemaking.

- Rapoport, A. (1990). The meaning of the built environment: A nonverbal communication approach. University of Arizona Press.

- Relph, E. (1976). Place and placelessness (Vol. 67). London: Pion.

- Rogan, R., O’Connor, M., & Horwitz, P. (2005). Nowhere to hide: Awareness and perceptions of environmental change, and their influence on relationships with place. Journal of environmental psychology, 25(2), 147-158. [CrossRef]

- Santen, C. V. (2006). Light zone city: Light planning in the urban context. De Gruyter.

- Seitinger, S., & Weiss, A. (2015). Light for public space. Eindhoven (NL): Philips Lighting.

- Sime, J. D. (1986). Creating places or designing spaces?. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 6(1), 49-63.. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Q. (2007). The ludic city: exploring the potential of public spaces. Routledge.

- Stokols, D. (1990). Instrumental and spiritual views of people-environment relations. American Psychologist, 45(5), 641. [CrossRef]

- The Institute of Historic Building Conservation, (2020, October 1) https://ihbc.org.uk,.

- Uchida, Y., & Taguchi, T. (2005). Lighting theory and luminous characteristics of white light-emitting diodes. Optical Engineering, 44(12), 124003-124003. [CrossRef]

- Ünver, A. (2009). People’s experience of urban lighting in public space (Master's thesis, Middle East Technical University).

- Zakaria, S. A., Mamat, M. J., Chern, L. S., Hong, C. M., Xuan, W. Z., & Shafie, S. N. A. (2018, September). Lighting heritage building practice in George town, Penang Island. In IOP conference series: materials science and engineering (Vol. 401, No. 1, p. 012005). IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Zeini Aslani, S., Mozaffar, R., Ekhlassi, A., Taghdir, S., & Mozaffar, H. (2022). Placemaking in Historic Sites with Lighting Scheme Case Study: Naghshe-Jahan Square, Isfahan, Iran. Iran University of Science & Technology, 32(2), 0-0.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).